Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

Published on 4 May 2022 by Bas Swaen and Tegan George. Revised on 18 March 2024.

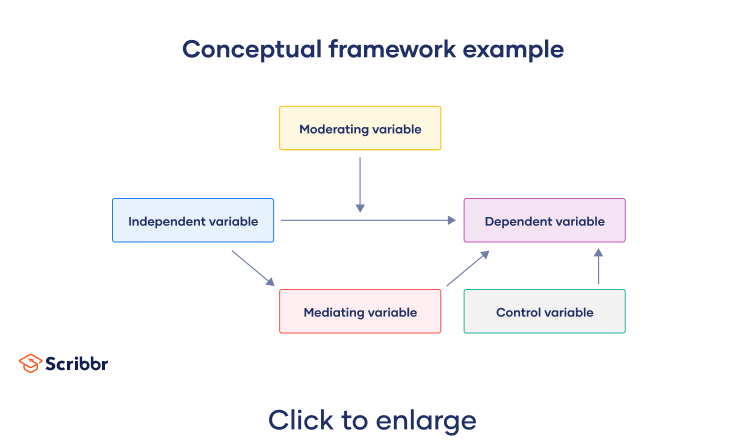

A conceptual framework illustrates the expected relationship between your variables. It defines the relevant objectives for your research process and maps out how they come together to draw coherent conclusions.

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide to help you construct your own conceptual framework.

Table of contents

Developing a conceptual framework in research, step 1: choose your research question, step 2: select your independent and dependent variables, step 3: visualise your cause-and-effect relationship, step 4: identify other influencing variables, frequently asked questions about conceptual models.

A conceptual framework is a representation of the relationship you expect to see between your variables, or the characteristics or properties that you want to study.

Conceptual frameworks can be written or visual and are generally developed based on a literature review of existing studies about your topic.

Your research question guides your work by determining exactly what you want to find out, giving your research process a clear focus.

However, before you start collecting your data, consider constructing a conceptual framework. This will help you map out which variables you will measure and how you expect them to relate to one another.

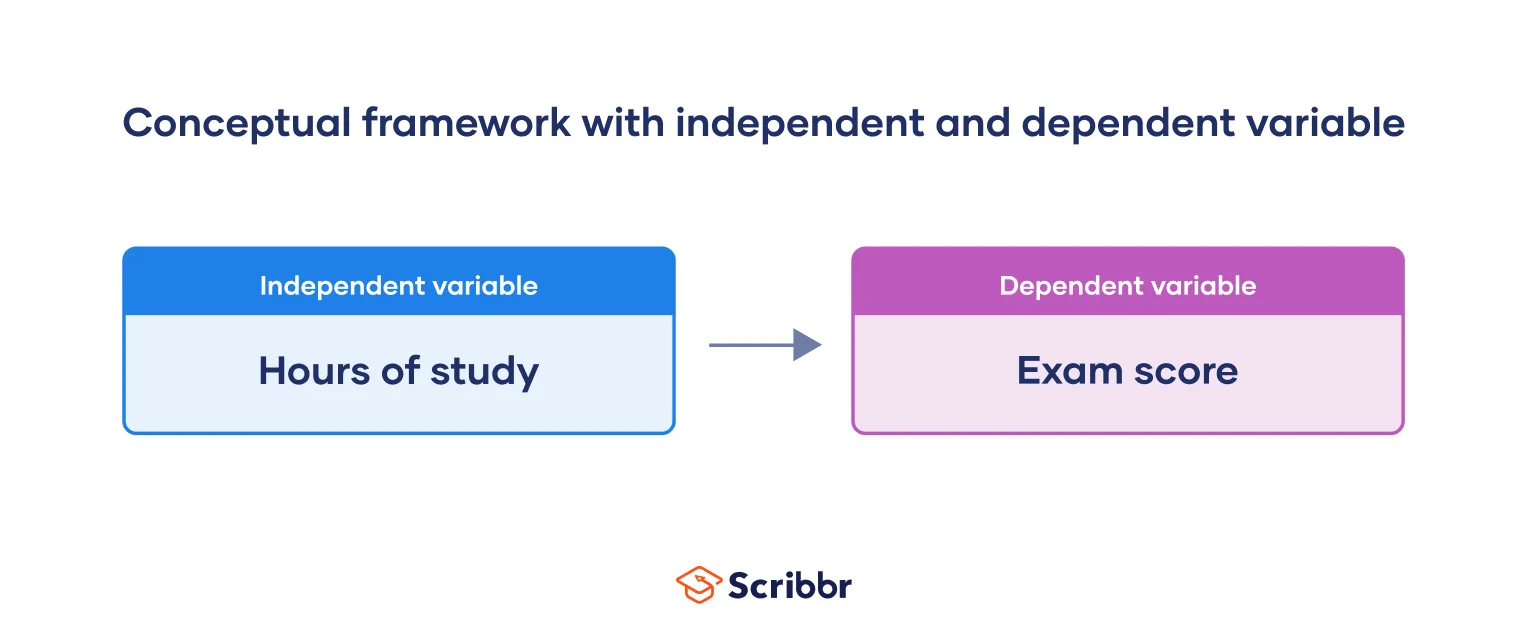

In order to move forward with your research question and test a cause-and-effect relationship, you must first identify at least two key variables: your independent and dependent variables .

- The expected cause, ‘hours of study’, is the independent variable (the predictor, or explanatory variable)

- The expected effect, ‘exam score’, is the dependent variable (the response, or outcome variable).

Note that causal relationships often involve several independent variables that affect the dependent variable. For the purpose of this example, we’ll work with just one independent variable (‘hours of study’).

Now that you’ve figured out your research question and variables, the first step in designing your conceptual framework is visualising your expected cause-and-effect relationship.

It’s crucial to identify other variables that can influence the relationship between your independent and dependent variables early in your research process.

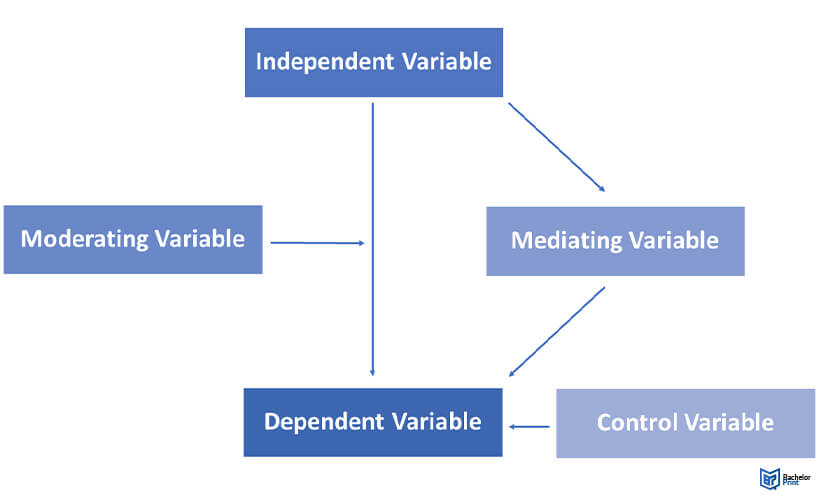

Some common variables to include are moderating, mediating, and control variables.

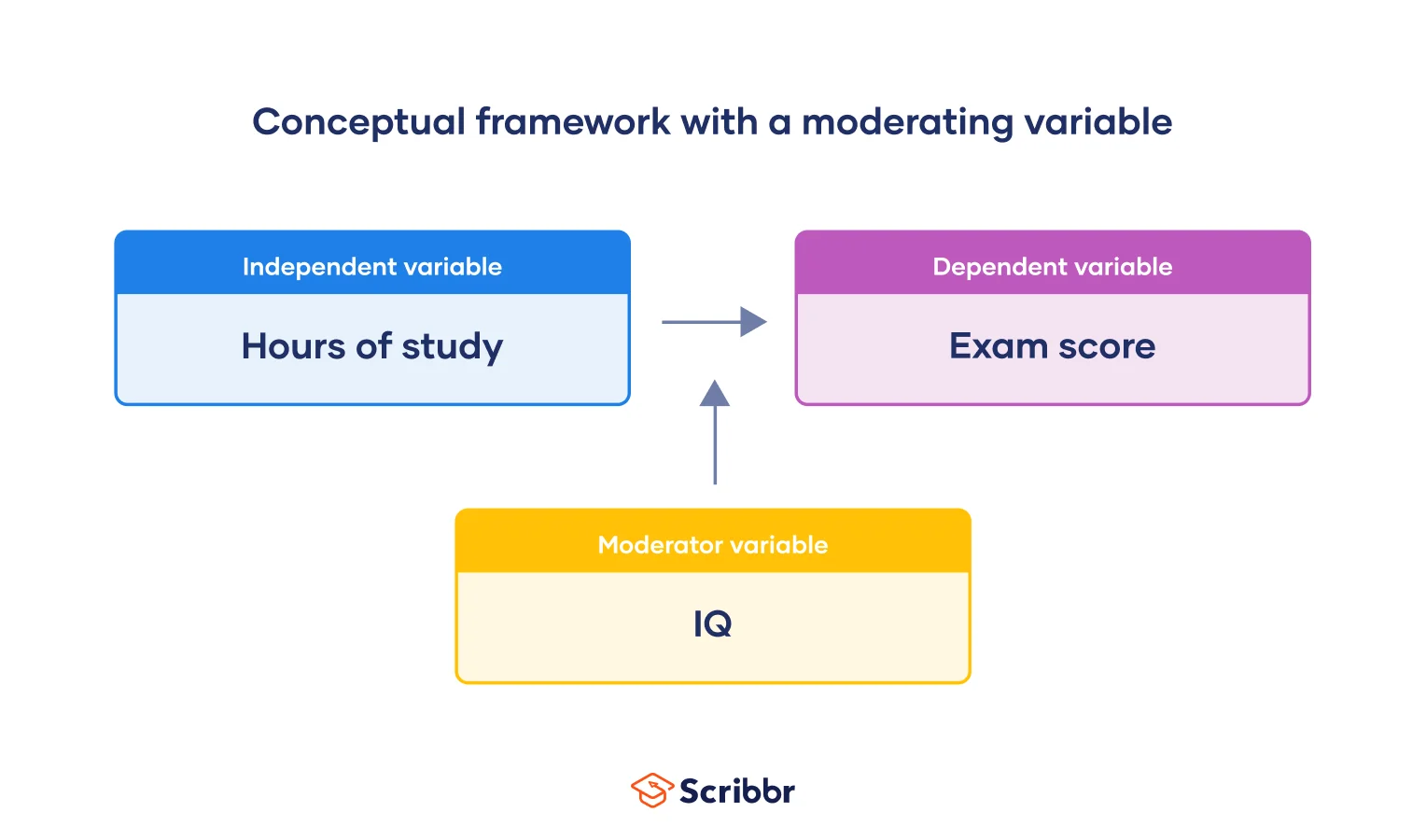

Moderating variables

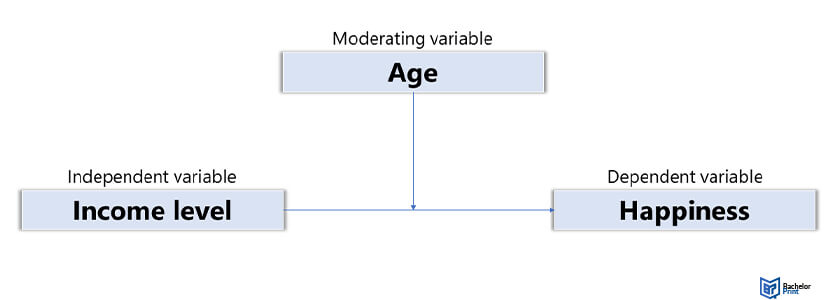

Moderating variable (or moderators) alter the effect that an independent variable has on a dependent variable. In other words, moderators change the ‘effect’ component of the cause-and-effect relationship.

Let’s add the moderator ‘IQ’. Here, a student’s IQ level can change the effect that the variable ‘hours of study’ has on the exam score. The higher the IQ, the fewer hours of study are needed to do well on the exam.

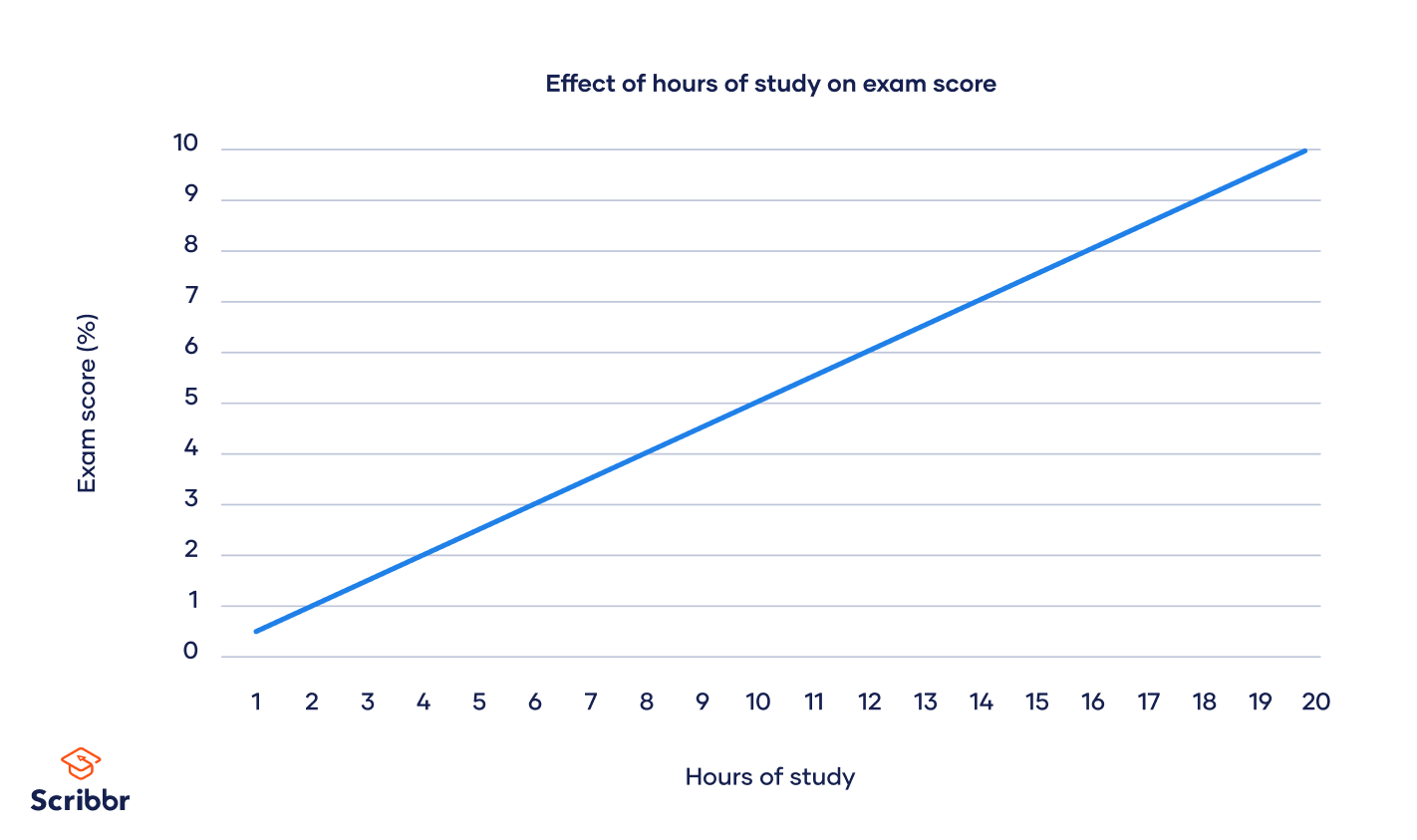

Let’s take a look at how this might work. The graph below shows how the number of hours spent studying affects exam score. As expected, the more hours you study, the better your results. Here, a student who studies for 20 hours will get a perfect score.

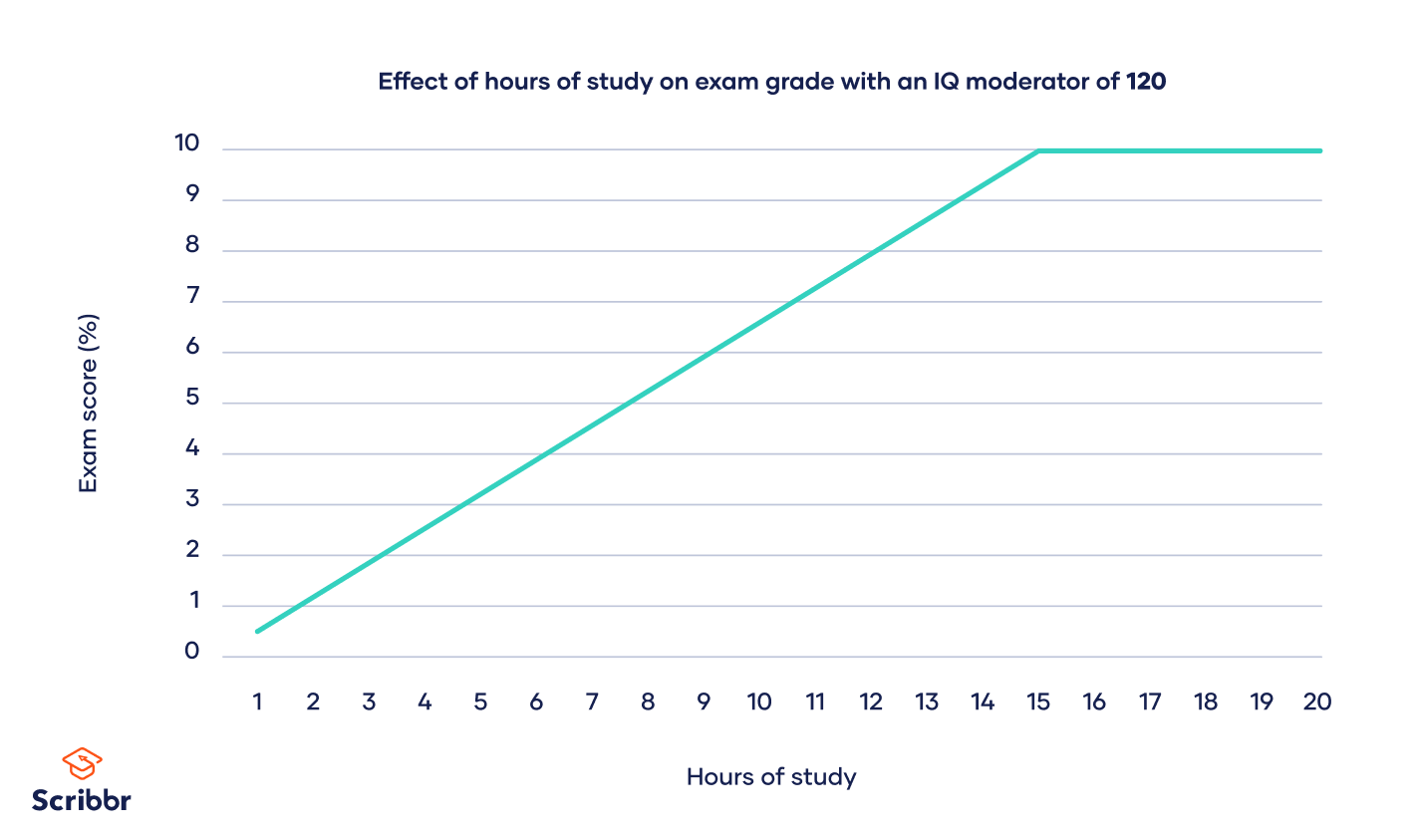

But the graph looks different when we add our ‘IQ’ moderator of 120. A student with this IQ will achieve a perfect score after just 15 hours of study.

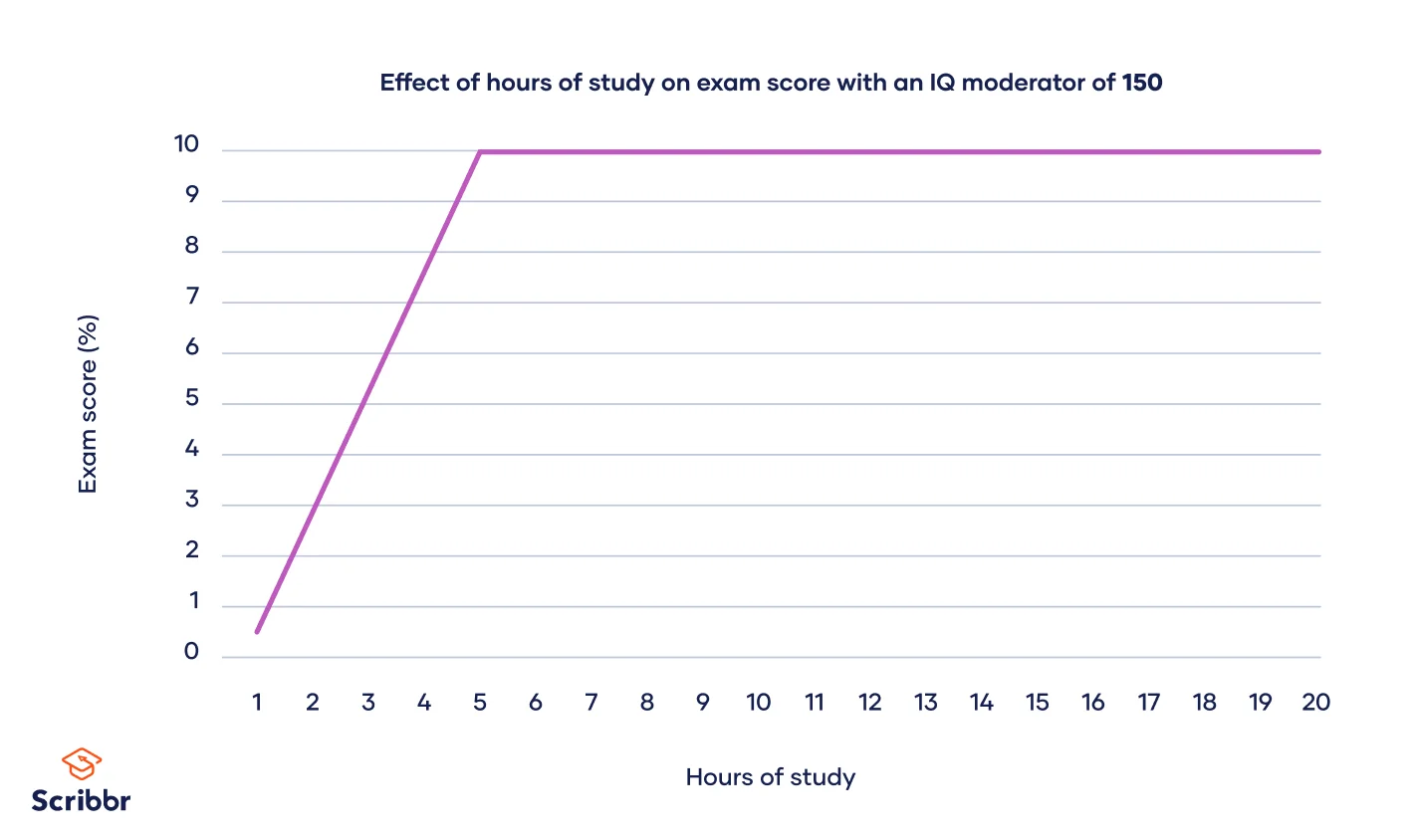

Below, the value of the ‘IQ’ moderator has been increased to 150. A student with this IQ will only need to invest five hours of study in order to get a perfect score.

Here, we see that a moderating variable does indeed change the cause-and-effect relationship between two variables.

Mediating variables

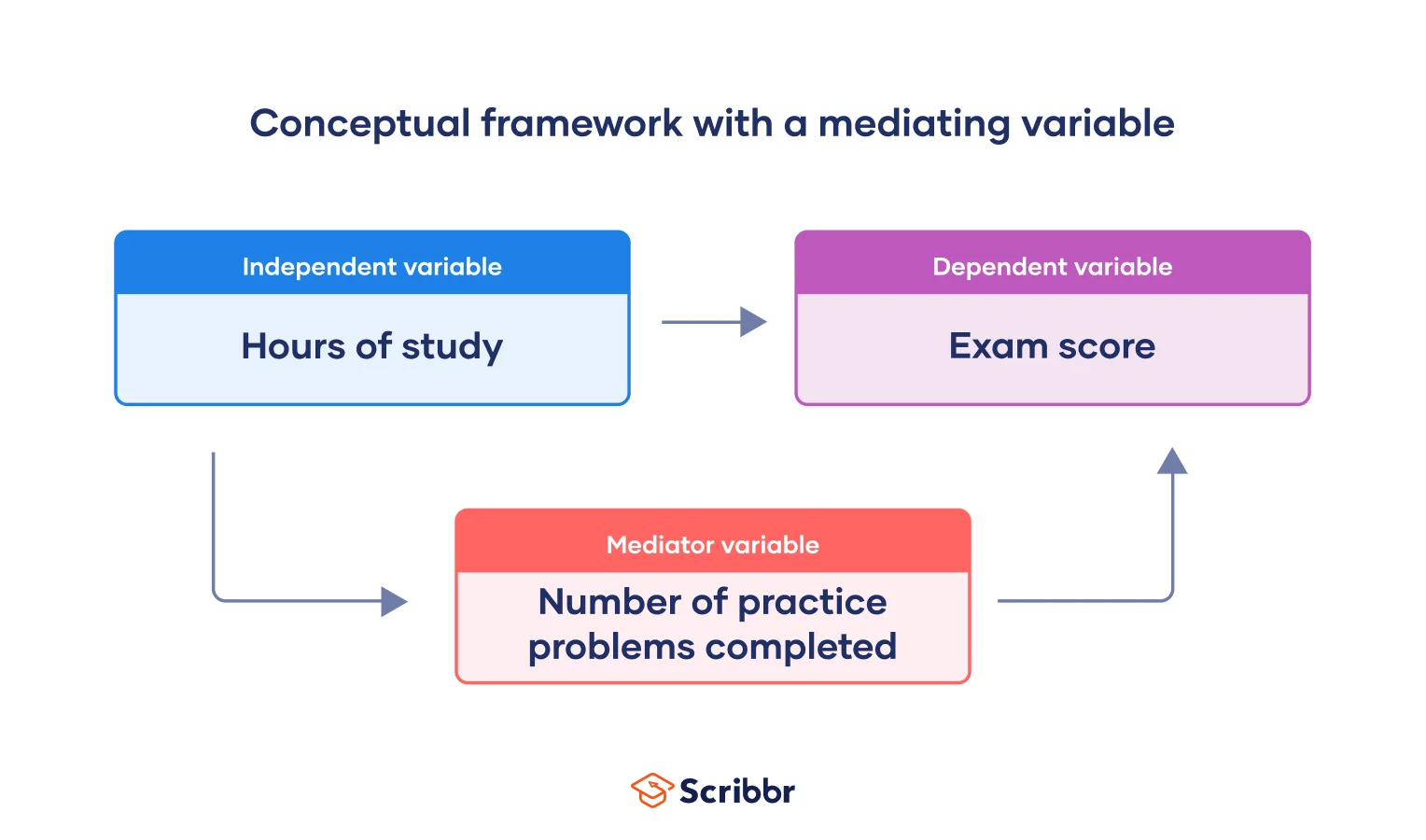

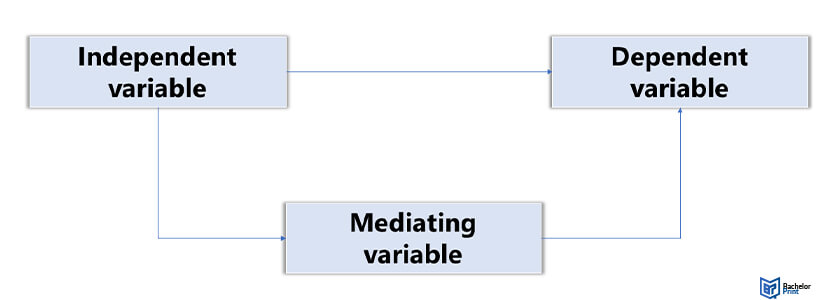

Now we’ll expand the framework by adding a mediating variable . Mediating variables link the independent and dependent variables, allowing the relationship between them to be better explained.

Here’s how the conceptual framework might look if a mediator variable were involved:

In this case, the mediator helps explain why studying more hours leads to a higher exam score. The more hours a student studies, the more practice problems they will complete; the more practice problems completed, the higher the student’s exam score will be.

Moderator vs mediator

It’s important not to confuse moderating and mediating variables. To remember the difference, you can think of them in relation to the independent variable:

- A moderating variable is not affected by the independent variable, even though it affects the dependent variable. For example, no matter how many hours you study (the independent variable), your IQ will not get higher.

- A mediating variable is affected by the independent variable. In turn, it also affects the dependent variable. Therefore, it links the two variables and helps explain the relationship between them.

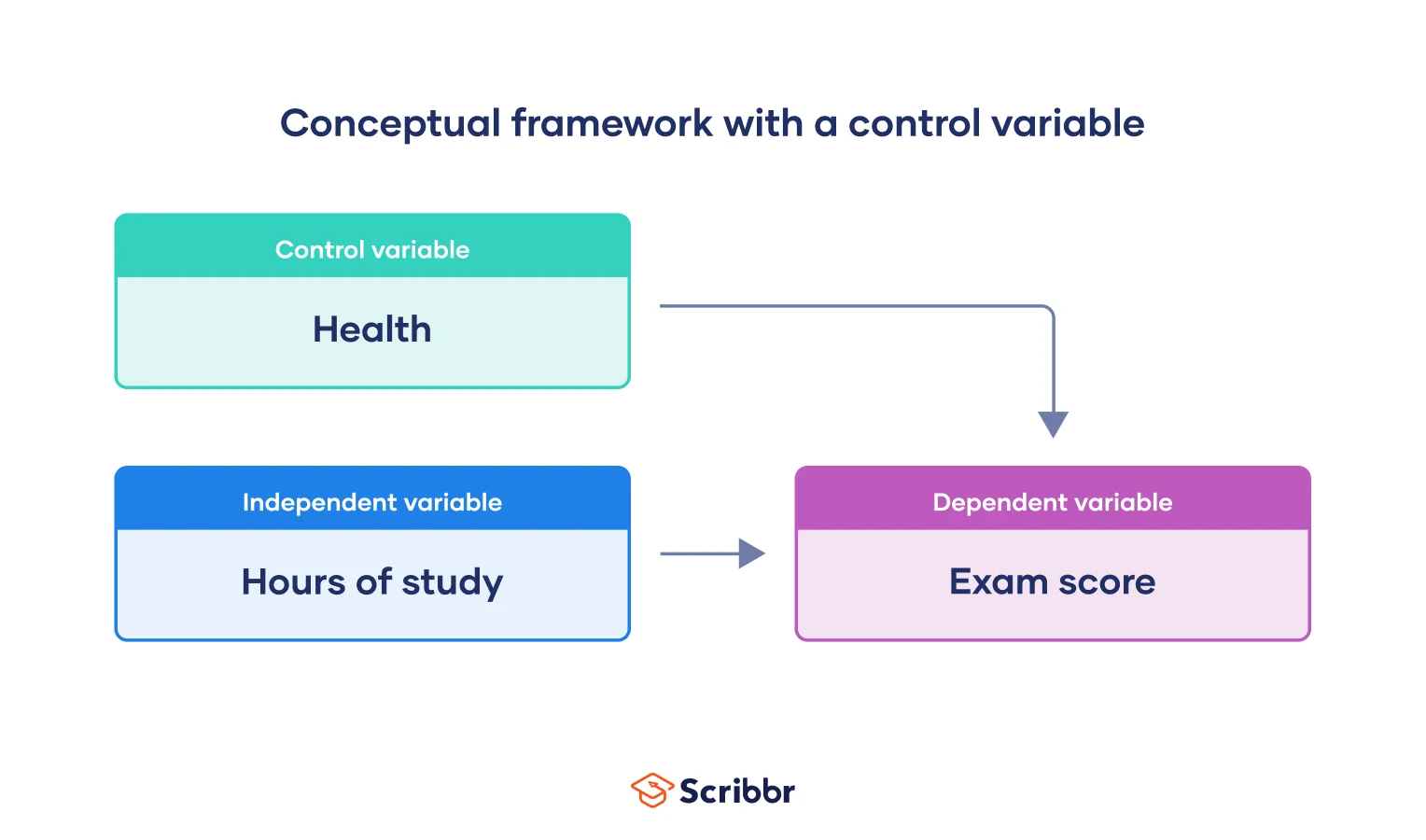

Control variables

Lastly, control variables must also be taken into account. These are variables that are held constant so that they don’t interfere with the results. Even though you aren’t interested in measuring them for your study, it’s crucial to be aware of as many of them as you can be.

A mediator variable explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderator variable affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

No. The value of a dependent variable depends on an independent variable, so a variable cannot be both independent and dependent at the same time. It must be either the cause or the effect, not both.

Yes, but including more than one of either type requires multiple research questions .

For example, if you are interested in the effect of a diet on health, you can use multiple measures of health: blood sugar, blood pressure, weight, pulse, and many more. Each of these is its own dependent variable with its own research question.

You could also choose to look at the effect of exercise levels as well as diet, or even the additional effect of the two combined. Each of these is a separate independent variable .

To ensure the internal validity of an experiment , you should only change one independent variable at a time.

A control variable is any variable that’s held constant in a research study. It’s not a variable of interest in the study, but it’s controlled because it could influence the outcomes.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Swaen, B. & George, T. (2024, March 18). What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/conceptual-frameworks/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

Mediator vs moderator variables | differences & examples, independent vs dependent variables | definition & examples, what are control variables | definition & examples.

Conceptual Models

Properties, Construction, Function(s) and Use

- First Online: 01 January 2010

Cite this chapter

- Jan Jonker 3 &

- Bartjan W. Pennink 4

8750 Accesses

1 Citations

This chapter examines the use of conceptual models in applied research. First, some general properties of these models are outlined against the background of various definitions. Any model is based on theoretical assumptions so it becomes relevant to understand what theory is and the role it plays in constructing a model in your research design. Armed with these generic insights we then look at the role and functions of a conceptual model in designing research as well as at how it can be used in the context of a closed and open research question. In the final paragraph suggestions are provided for the construction of a model within the context of your own research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

It is time to say something about the word ‘conceptual’. It means: ‘based on mental concepts’. These concepts of the mind represent in a way paradigms and are, thus, fundamentally theoretical. The notion, furthermore, contains a reference to ‘wholeness’ – when you make a concept of something it implies it is a kind of encompassing or complete.

Please note that in this chapter we will talk about theory and systems theory in the same breath. Although the line to distinguish between the two is rather thin here we mean by theory (in general) ‘… an idea or set of ideas that is intended to explain something’ … ‘which conceptualises some aspect or experience’ (see Glossary). Systems Theory is a ‘member’ of the family of theory focussing on systems. This is particularly important here because we consider not only organisations systems but conceptual models also.

Eclectic means: deriving ideas, style, or taste from a broad and diverse range of sources (source: any decent dictionary).

Please remember that although we know it is philosophically doubtful to speak of an empirical reality we still do it for practical reasons.

Characteristic of management literature in general is the abundance of a plethora of ‘conceptual’ models. We put the word conceptual between commas here because many of these models are based on the (practical) experience of the authors without any precise theoretical foundation. Wrapped in an attractive language and supported by some do’s and don’t this makes a first-class business case for consultants.

Bacharach, S. (1989). Organizational theories: some criteria for evaluation. Academy of Management Review, 14 , 496–515.

Google Scholar

Belbin, R. M. (1993). Team roles at work . Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Berkeley Thomas, A. (2004). Research skills for management studies . London: Routledge.

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic Interactionism: perspective and method . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Bryman, A. (2004). Social research methods . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Checkland, P. & Scholes, J. (1990). Soft systems methodology in action . Chichester: Wiley.

de Groot, A. D. (1969). Methodology: foundations of inferences and research in the behavioral science . The Hague: Mouton.

Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Handbook of qualitative research . London: Sage.

Emery, F. E. & Trist, E. L. (1965). The causal texture of organizational environments. Human relations, 18 , 21–32.

Article Google Scholar

Foley, K. J. (2005). Meta management . Melbourne: Standards Australia.

Giere, R. (1991). Understanding scientific reasoning . Orlanda: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Isaacs, W. (1999). Dialogue: the art of thinking together . New York: Random House.

Key, S. (1999). Toward a new theory of the firm: a critique of ‘stakeholder’ theory. Management Decision, 37 (4), 317–328.

Labovitz, S. & Hagedorn, R. (1971). Introduction to social research . New York: McGraw Hill.

Northcall, N. & Mccloy, D. (2004). Interactive qualitative analysis, a systems method for qualitative research . London: Sage.

Rüegg-Stürm, J. (2005). The New St. Gallen management model; basic categories of an approach to integrated management . Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ryan, B., Scapens, R. W., & Theobald, M. (1992). Research method and methodology in finance and accounting . London: Academic Press, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers.

Strauss, A. L. & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research; grounded theory procedures and techniques . London: Sage.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nijmegen School of Management (NSM), Radboud University Nijmegen (RU), 9108, 6500, HK, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Dr. Jan Jonker

Department of International Business and Management, Faculty of Economics and Business University of Groningen, Landleven 5, 9700, AV, Groningen, The Netherlands

Dr. Bartjan W. Pennink

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jan Jonker .

Interlude I Conceptualising Methodology

“I think, this time … we really have a problem, don’t you?”

“Hm, yes, I think I must agree but … can’t we hire a consultant again … a good one this time?”

“You mean one that solves the problem and doesn’t just send bills?”

“Something like that.”

“Don’t know if it is that kind of problem.”

“Meaning ….?”

“Well, this time I think the problem is us. What we do. How we talk? How do we decide? How do we treat each other behind our backs? That kind of things”

“Well, if you are certain, then we really have a problem.”

3.1.1 Conceptualising Methodology

This first interlude focuses on the problematic nature of conceptualising a (organisational) problem with the help of methodology. It touches on a number of underlying issues, thus demonstrating the limits of any research design. As a whole it provides a critique of the measurability of organisational reality. The interlude is above all meant as ‘food for thought’- not for solving problems. So, if the previous three chapters have left you dazzled by the kaleidoscopic nature of assumptions, paradigms and, yes, methodologies, do not read this interlude. But, if you are asked to provide a critical justification of your research design you definitely should (see also Chap. 8 ). We think this interlude is helpful in understanding and appreciating the content of the next two chapters on qualitative and quantitative methodology.

3.1.1.1 The Social Origins of Problems

The essence of applied research is and will be the researcher investigating a particular problem in an organisation or company that only occurs there and is, thus, of a unique contextualised significance. Essential to the kind of problems we address is that that they always occur in a social situation, in contrast to a laboratory experiment for instance. A social situation can be categorised in the following research ‘areas’:

The people involved (the actors or stakeholders); who form the focus of attention in this research?

The actions themselves; which kind of activities or events does this research focus on – decisions, operations, R&D?

The place where it all happens; does it revolve around activities that take place at the headquarters or in the business units? Does it concern the observation of all possible situations or the same situation, but at different locations?

The time when things happen; to what extent will attention (need to) be paid to time or moment? Is it relevant to observe something over the years or will the focus fall on the distinction between day and night?

The used ‘ objects’ (and) (or) knowledge ; does the problem revolve around the right use of certain rules, procedures, regulations at the proper moment and to what extent is this machine-related?

The nature of the produced goods or services ; to what extent might it be useful to make a distinction between tangible or intangible goods?

The meaning and intentions of people’s actions at a certain place and at a certain moment.

Anyone reading this will again realise that applied research focusing on problems is by definition embedded in the social side of the enterprise. It is people that experience a situation as problematic and subsequently name and frame it. Given this social nature a number of fundamental questions surface when it comes to analysing problems. Most of them have been touched upon in the previous chapters. Here we wish to address and elaborate some of them again thus providing ‘food for thought’.

3.1.1.2 Instrumentality

It might be that your attitude when addressing problems – especially when doing research projects for the first time – is to accept a problem on face value. Something like: “… this is the problem as it is and this is where my analysis will start’. We previously outlined the idea that problems are human constructs. It is true that a certain reality can be problematic but it can also be the case that a specific reality is problematised with other purposes in mind, purposes that have nothing to do with the problem itself. Think of the person who protects his position by holding on to a (still to be solved but never will be) problem. Or the fact that as long as a problem is spoken about the person who possesses the problem receives attention. If that is the nature of the problem you will have to focus your research on the person since he or she might be a key part of the problem. Analysing this in a rational goal-oriented manner could possibly make the problem get even worse. In the end, the bottom-line message is quite simple: not all problems are constructed with the implicit desire to solve them. Some problems are created with totally different purposes in mind. Please be aware that your research is not about solving all kinds of problems in the world. You do not solve problems at random. Just addressing them in a scholarly manner is sometimes enough.

3.1.1.3 Intervention

The sheer act of announcing a research project is already an intervention in a specific reality. Even if you have done all your homework, the moment you announce that you are starting a research project in an organisation that organisation will change – albeit modestly and imperceptibly. Without necessarily pronouncing it people will have certain ideas, motives and expectations about the upcoming research event. ‘What will he do?’, ‘Can I use this to some extent?’, ‘Will he see me and what will he then ask?’, ‘What kind of influence will this research have on my function?’ or ‘This is once more a demonstration of our incapable management – I will refuse any cooperation when it comes to it.’ You can never be ahead of all these questions. The act of intervening through your research raises a real dilemma. And as with all dilemmas you are forced to make (difficult) choices – choices that are open to more then just one interpretation – that you then need to justify.

3.1.1.4 Measurability

The first two chapters have demonstrated the problematic nature of ‘reality’. Still no criticism was formulated about the measurability of that reality. The term ‘measurability’ can be interpreted in various ways. On the one hand there is the notion of ‘ability’. It refers to the level of professionalism of the researcher and his ability to carry out a decent piece of research. Is he capable of carrying out what he is planning to do in justifiable manner? On the other hand, there is the assumption that – if approached appropriately – reality is indeed measurable. It does no harm to question this second assumption. Indeed it is not complicated to measure the ‘natural’ conditions in a workplace: temperature, noise or humidity are all very measurable properties. What about notions such as the ‘smell of the place’, ‘a hostile atmosphere’ or even ‘insufficient communication’? In order to make these notions measurable, it is necessary to make theoretical constructs (models) based on an interpretation. Even done properly in terms of reliability and validity the question still remains how measurable such phenomena remain.

3.1.1.5 Theory

We have proclaimed in the previous chapters that reality cannot be addressed without ‘a theory’ in mind. Theory shapes and directs our vision. In fact theory is the ‘instrument’ or carrier that allows us to see what we want to see and not always in the way we want to see it. Theory shapes and directs our vision. Implicitly, it means that we can articulate what is theoretical and what is worth being seen and, thus, emphasised. The relevant theory given a specific problem can be articulated in words. Just think for a moment about emotions, intuition or ‘gut feeling’. Or think also about a popular construct such as ‘emotional intelligence’. What we face here is a rational and often linear-causal approach to reality. Things can be identified, conceptualised in a logical construct and turned into measurable properties. Just imagine you would analyse the relationship with your partner in such a way and then present it to him or her. Do you think it would be a good idea? Not really.

3.1.1.6 Subjectivity

When designing research we make a selection (intuitively or consciously) out of an ongoing stream of events. The sheer fact of selecting certain events above others – the act of giving them additional attention – also called ‘bracketing’ (Weick 1979) puts an emphasis on them thus ‘enlarging’ them. Even if we respect the most stringent scholarliness bracketing remains something done by an actor based on his knowledge, experience and professionalism at the specific moment in time. Thus, it appears that by definition subjectivity in any research design is inescapable. If we accept this fundamental subjectivity of any research activity then justification becomes almost the only way to demonstrate the quality of a research design and subsequent process.

3.1.1.7 Ontology

We act in this world with limited knowledge. This largely accepted fact is also known as ‘bounded rationality’. Not only is it simply impossible to know everything about everything, we can’t even be sure we know what we know. What we know escapes our full understanding yet it is at the same time an unlimited source. This indirectly raises the issue of ontology: the overall conceptualisation of a field of knowledge not necessarily presented in a structured manner (see Glossary). In organisations we refer to this phenomenon as ‘knowledge management’. Ontology in general relates to the assumptions we hold about reality – whether it is external or a construct of our mind. Knowledge can be attributed in part to be in the possession of people and at the same time a result of interactions. Since people cannot really define what they know in a specific field or regarding a particular topic it is only in interactions that they demonstrate and create knowledge. This complex phenomenon describes the social construction of knowledge. We recognise again here the two fundamental – positivist and constructivist – traditions, both of which are present in any research.

3.1.1.8 Epistemology

Epistemology can be described as the philosophy of knowledge, especially with regard to its methods, validity, nature, sources, limits and scope. It concerns the investigation of what distinguishes justified belief from opinion. “Lucky guesses or ‘true’ beliefs resulting from wishful thinking are not knowledge.” (Craig 2005, p. 224). As such it is the ‘quality assurance’ of what we know. Still, specificity of what knowledge is remains a matter of controversy. “One view is that what distinguishes genuine knowledge from a lucky guess is justification; another is that the causation of the belief by facts verifies it.” (Bullock and Trombley 1999). Justification is a central element to any research design and its outcome. The nature of the facts – i.e. the nature of the data and how they have been acquired – forms the cornerstone in such a design. We stick to the view that the logic of the argument used to select certain means (methods and techniques) for producing data and knowledge has to be reliable.

3.1.1.9 Deontology

If we explore critically the definition of methodology it shows a certain degree of ‘mandatoriness’: as a rule, what seems to be required is shared conviction. Despite the earlier stipulated emptiness of methodology we face an intriguing issue here called deontology. Deontology concerns the study of the nature of duty and obligation of ‘what is necessary’. It is quite thought-provoking to consider the possible universe of methodologies for a moment as a collection of deontologies, each individual methodology specifying its own plan of action, the acts themselves and the consistent if not rational order in which actions have to be performed. The inevitable question is to what degree this deontological nature is free of normativity. Who decides on the appropriateness of the order of acts, their causality, their logic if not their appropriateness? We stumble upon a more philosophical discussion regarding the ontological nature of methodology. There is no need to elaborate any further here. Just be aware that any methodology is not ‘natural’ but driven by (historically) driven beliefs about acting. When finally defending your work this will be a key decisive factor – at least implicitly but almost certainly explicitly.

3.1.1.10 Finally: The Role of the Researcher

Given the reflections above it should be clear that conceptualising a problem is not only a craft it is also an art entailing the researcher to navigate between all kinds of theoretical, methodological, philosophical and other booby-traps and dilemmas. Any problem addressed in an organisation is a temporary valid construction of just a fraction of that specific reality. It is naïve and probably incorrect if the researcher is convinced he alone has the knowledge to clarify the nature and meaning of the problem at hand, be it at the start of the research or well underway. The researcher’s most valid contribution is to conduct careful research into the nature, size, impact and meaning of a particular problem by means of various methodological approaches. Any research therefore should be conducted departing from – if not focusing on – the situation and people that ‘create’ the situation. If we recognise and accept the nature of the question this in itself is already a compass. To proceed in either a quantitative or qualitative way or a combination of both is elaborated in the following two chapters and Interlude II.

Bonjour, L. (1985). The Structure of Empirical Knowledge , Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Blaikie, N. (1993). Approaches to social enquiry , Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bullock, A., Trombley, S. (1999). The New Dictionary of Modern Thought , London: HarperCollins.

Chisholm, R. (1989). Theory of Knowledge , Cambrige: Harvard University Press.

Craig, E. (eds.) (2005). The Shorter Encyclopedia of Philosophy , London: Routledge.

Griseri, P. (2002). Management Knowledge: a critical view , New York: Palgrave.

Johnson, P., Duberley, J. (2000). Understanding management research: an introduction to epistemology , London: Sage.n.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2010 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Jonker, J., Pennink, B.W. (2010). Conceptual Models. In: The Essence of Research Methodology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-71659-4_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-71659-4_3

Published : 31 January 2010

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-540-71658-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-540-71659-4

eBook Packages : Business and Economics Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Privacy Policy

Home » Conceptual Framework – Types, Methodology and Examples

Conceptual Framework – Types, Methodology and Examples

Table of Contents

Conceptual Framework

Definition:

A conceptual framework is a structured approach to organizing and understanding complex ideas, theories, or concepts. It provides a systematic and coherent way of thinking about a problem or topic, and helps to guide research or analysis in a particular field.

A conceptual framework typically includes a set of assumptions, concepts, and propositions that form a theoretical framework for understanding a particular phenomenon. It can be used to develop hypotheses, guide empirical research, or provide a framework for evaluating and interpreting data.

Conceptual Framework in Research

In research, a conceptual framework is a theoretical structure that provides a framework for understanding a particular phenomenon or problem. It is a key component of any research project and helps to guide the research process from start to finish.

A conceptual framework provides a clear understanding of the variables, relationships, and assumptions that underpin a research study. It outlines the key concepts that the study is investigating and how they are related to each other. It also defines the scope of the study and sets out the research questions or hypotheses.

Types of Conceptual Framework

Types of Conceptual Framework are as follows:

Theoretical Framework

A theoretical framework is an overarching set of concepts, ideas, and assumptions that help to explain and interpret a phenomenon. It provides a theoretical perspective on the phenomenon being studied and helps researchers to identify the relationships between different concepts. For example, a theoretical framework for a study on the impact of social media on mental health might draw on theories of communication, social influence, and psychological well-being.

Conceptual Model

A conceptual model is a visual or written representation of a complex system or phenomenon. It helps to identify the main components of the system and the relationships between them. For example, a conceptual model for a study on the factors that influence employee turnover might include factors such as job satisfaction, salary, work-life balance, and job security, and the relationships between them.

Empirical Framework

An empirical framework is based on empirical data and helps to explain a particular phenomenon. It involves collecting data, analyzing it, and developing a framework to explain the results. For example, an empirical framework for a study on the impact of a new health intervention might involve collecting data on the intervention’s effectiveness, cost, and acceptability to patients.

Descriptive Framework

A descriptive framework is used to describe a particular phenomenon. It helps to identify the main characteristics of the phenomenon and to develop a vocabulary to describe it. For example, a descriptive framework for a study on different types of musical genres might include descriptions of the instruments used, the rhythms and beats, the vocal styles, and the cultural contexts of each genre.

Analytical Framework

An analytical framework is used to analyze a particular phenomenon. It involves breaking down the phenomenon into its constituent parts and analyzing them separately. This type of framework is often used in social science research. For example, an analytical framework for a study on the impact of race on police brutality might involve analyzing the historical and cultural factors that contribute to racial bias, the organizational factors that influence police behavior, and the psychological factors that influence individual officers’ behavior.

Conceptual Framework for Policy Analysis

A conceptual framework for policy analysis is used to guide the development of policies or programs. It helps policymakers to identify the key issues and to develop strategies to address them. For example, a conceptual framework for a policy analysis on climate change might involve identifying the key stakeholders, assessing their interests and concerns, and developing policy options to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Logical Frameworks

Logical frameworks are used to plan and evaluate projects and programs. They provide a structured approach to identifying project goals, objectives, and outcomes, and help to ensure that all stakeholders are aligned and working towards the same objectives.

Conceptual Frameworks for Program Evaluation

These frameworks are used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions. They provide a structure for identifying program goals, objectives, and outcomes, and help to measure the impact of the program on its intended beneficiaries.

Conceptual Frameworks for Organizational Analysis

These frameworks are used to analyze and evaluate organizational structures, processes, and performance. They provide a structured approach to understanding the relationships between different departments, functions, and stakeholders within an organization.

Conceptual Frameworks for Strategic Planning

These frameworks are used to develop and implement strategic plans for organizations or businesses. They help to identify the key factors and stakeholders that will impact the success of the plan, and provide a structure for setting goals, developing strategies, and monitoring progress.

Components of Conceptual Framework

The components of a conceptual framework typically include:

- Research question or problem statement : This component defines the problem or question that the conceptual framework seeks to address. It sets the stage for the development of the framework and guides the selection of the relevant concepts and constructs.

- Concepts : These are the general ideas, principles, or categories that are used to describe and explain the phenomenon or problem under investigation. Concepts provide the building blocks of the framework and help to establish a common language for discussing the issue.

- Constructs : Constructs are the specific variables or concepts that are used to operationalize the general concepts. They are measurable or observable and serve as indicators of the underlying concept.

- Propositions or hypotheses : These are statements that describe the relationships between the concepts or constructs in the framework. They provide a basis for testing the validity of the framework and for generating new insights or theories.

- Assumptions : These are the underlying beliefs or values that shape the framework. They may be explicit or implicit and may influence the selection and interpretation of the concepts and constructs.

- Boundaries : These are the limits or scope of the framework. They define the focus of the investigation and help to clarify what is included and excluded from the analysis.

- Context : This component refers to the broader social, cultural, and historical factors that shape the phenomenon or problem under investigation. It helps to situate the framework within a larger theoretical or empirical context and to identify the relevant variables and factors that may affect the phenomenon.

- Relationships and connections: These are the connections and interrelationships between the different components of the conceptual framework. They describe how the concepts and constructs are linked and how they contribute to the overall understanding of the phenomenon or problem.

- Variables : These are the factors that are being measured or observed in the study. They are often operationalized as constructs and are used to test the propositions or hypotheses.

- Methodology : This component describes the research methods and techniques that will be used to collect and analyze data. It includes the sampling strategy, data collection methods, data analysis techniques, and ethical considerations.

- Literature review : This component provides an overview of the existing research and theories related to the phenomenon or problem under investigation. It helps to identify the gaps in the literature and to situate the framework within the broader theoretical and empirical context.

- Outcomes and implications: These are the expected outcomes or implications of the study. They describe the potential contributions of the study to the theoretical and empirical knowledge in the field and the practical implications for policy and practice.

Conceptual Framework Methodology

Conceptual Framework Methodology is a research method that is commonly used in academic and scientific research to develop a theoretical framework for a study. It is a systematic approach that helps researchers to organize their thoughts and ideas, identify the variables that are relevant to their study, and establish the relationships between these variables.

Here are the steps involved in the conceptual framework methodology:

Identify the Research Problem

The first step is to identify the research problem or question that the study aims to answer. This involves identifying the gaps in the existing literature and determining what specific issue the study aims to address.

Conduct a Literature Review

The second step involves conducting a thorough literature review to identify the existing theories, models, and frameworks that are relevant to the research question. This will help the researcher to identify the key concepts and variables that need to be considered in the study.

Define key Concepts and Variables

The next step is to define the key concepts and variables that are relevant to the study. This involves clearly defining the terms used in the study, and identifying the factors that will be measured or observed in the study.

Develop a Theoretical Framework

Once the key concepts and variables have been identified, the researcher can develop a theoretical framework. This involves establishing the relationships between the key concepts and variables, and creating a visual representation of these relationships.

Test the Framework

The final step is to test the theoretical framework using empirical data. This involves collecting and analyzing data to determine whether the relationships between the key concepts and variables that were identified in the framework are accurate and valid.

Examples of Conceptual Framework

Some realtime Examples of Conceptual Framework are as follows:

- In economics , the concept of supply and demand is a well-known conceptual framework. It provides a structure for understanding how prices are set in a market, based on the interplay of the quantity of goods supplied by producers and the quantity of goods demanded by consumers.

- In psychology , the cognitive-behavioral framework is a widely used conceptual framework for understanding mental health and illness. It emphasizes the role of thoughts and behaviors in shaping emotions and the importance of cognitive restructuring and behavior change in treatment.

- In sociology , the social determinants of health framework provides a way of understanding how social and economic factors such as income, education, and race influence health outcomes. This framework is widely used in public health research and policy.

- In environmental science , the ecosystem services framework is a way of understanding the benefits that humans derive from natural ecosystems, such as clean air and water, pollination, and carbon storage. This framework is used to guide conservation and land-use decisions.

- In education, the constructivist framework is a way of understanding how learners construct knowledge through active engagement with their environment. This framework is used to guide instructional design and teaching strategies.

Applications of Conceptual Framework

Some of the applications of Conceptual Frameworks are as follows:

- Research : Conceptual frameworks are used in research to guide the design, implementation, and interpretation of studies. Researchers use conceptual frameworks to develop hypotheses, identify research questions, and select appropriate methods for collecting and analyzing data.

- Policy: Conceptual frameworks are used in policy-making to guide the development of policies and programs. Policymakers use conceptual frameworks to identify key factors that influence a particular problem or issue, and to develop strategies for addressing them.

- Education : Conceptual frameworks are used in education to guide the design and implementation of instructional strategies and curriculum. Educators use conceptual frameworks to identify learning objectives, select appropriate teaching methods, and assess student learning.

- Management : Conceptual frameworks are used in management to guide decision-making and strategy development. Managers use conceptual frameworks to understand the internal and external factors that influence their organizations, and to develop strategies for achieving their goals.

- Evaluation : Conceptual frameworks are used in evaluation to guide the development of evaluation plans and to interpret evaluation results. Evaluators use conceptual frameworks to identify key outcomes, indicators, and measures, and to develop a logic model for their evaluation.

Purpose of Conceptual Framework

The purpose of a conceptual framework is to provide a theoretical foundation for understanding and analyzing complex phenomena. Conceptual frameworks help to:

- Guide research : Conceptual frameworks provide a framework for researchers to develop hypotheses, identify research questions, and select appropriate methods for collecting and analyzing data. By providing a theoretical foundation for research, conceptual frameworks help to ensure that research is rigorous, systematic, and valid.

- Provide clarity: Conceptual frameworks help to provide clarity and structure to complex phenomena by identifying key concepts, relationships, and processes. By providing a clear and systematic understanding of a phenomenon, conceptual frameworks help to ensure that researchers, policymakers, and practitioners are all on the same page when it comes to understanding the issue at hand.

- Inform decision-making : Conceptual frameworks can be used to inform decision-making and strategy development by identifying key factors that influence a particular problem or issue. By understanding the complex interplay of factors that contribute to a particular issue, decision-makers can develop more effective strategies for addressing the problem.

- Facilitate communication : Conceptual frameworks provide a common language and conceptual framework for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to communicate and collaborate on complex issues. By providing a shared understanding of a phenomenon, conceptual frameworks help to ensure that everyone is working towards the same goal.

When to use Conceptual Framework

There are several situations when it is appropriate to use a conceptual framework:

- To guide the research : A conceptual framework can be used to guide the research process by providing a clear roadmap for the research project. It can help researchers identify key variables and relationships, and develop hypotheses or research questions.

- To clarify concepts : A conceptual framework can be used to clarify and define key concepts and terms used in a research project. It can help ensure that all researchers are using the same language and have a shared understanding of the concepts being studied.

- To provide a theoretical basis: A conceptual framework can provide a theoretical basis for a research project by linking it to existing theories or conceptual models. This can help researchers build on previous research and contribute to the development of a field.

- To identify gaps in knowledge : A conceptual framework can help identify gaps in existing knowledge by highlighting areas that require further research or investigation.

- To communicate findings : A conceptual framework can be used to communicate research findings by providing a clear and concise summary of the key variables, relationships, and assumptions that underpin the research project.

Characteristics of Conceptual Framework

key characteristics of a conceptual framework are:

- Clear definition of key concepts : A conceptual framework should clearly define the key concepts and terms being used in a research project. This ensures that all researchers have a shared understanding of the concepts being studied.

- Identification of key variables: A conceptual framework should identify the key variables that are being studied and how they are related to each other. This helps to organize the research project and provides a clear focus for the study.

- Logical structure: A conceptual framework should have a logical structure that connects the key concepts and variables being studied. This helps to ensure that the research project is coherent and consistent.

- Based on existing theory : A conceptual framework should be based on existing theory or conceptual models. This helps to ensure that the research project is grounded in existing knowledge and builds on previous research.

- Testable hypotheses or research questions: A conceptual framework should include testable hypotheses or research questions that can be answered through empirical research. This helps to ensure that the research project is rigorous and scientifically valid.

- Flexibility : A conceptual framework should be flexible enough to allow for modifications as new information is gathered during the research process. This helps to ensure that the research project is responsive to new findings and is able to adapt to changing circumstances.

Advantages of Conceptual Framework

Advantages of the Conceptual Framework are as follows:

- Clarity : A conceptual framework provides clarity to researchers by outlining the key concepts and variables that are relevant to the research project. This clarity helps researchers to focus on the most important aspects of the research problem and develop a clear plan for investigating it.

- Direction : A conceptual framework provides direction to researchers by helping them to develop hypotheses or research questions that are grounded in existing theory or conceptual models. This direction ensures that the research project is relevant and contributes to the development of the field.

- Efficiency : A conceptual framework can increase efficiency in the research process by providing a structure for organizing ideas and data. This structure can help researchers to avoid redundancies and inconsistencies in their work, saving time and effort.

- Rigor : A conceptual framework can help to ensure the rigor of a research project by providing a theoretical basis for the investigation. This rigor is essential for ensuring that the research project is scientifically valid and produces meaningful results.

- Communication : A conceptual framework can facilitate communication between researchers by providing a shared language and understanding of the key concepts and variables being studied. This communication is essential for collaboration and the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Generalization : A conceptual framework can help to generalize research findings beyond the specific study by providing a theoretical basis for the investigation. This generalization is essential for the development of knowledge in the field and for informing future research.

Limitations of Conceptual Framework

Limitations of Conceptual Framework are as follows:

- Limited applicability: Conceptual frameworks are often based on existing theory or conceptual models, which may not be applicable to all research problems or contexts. This can limit the usefulness of a conceptual framework in certain situations.

- Lack of empirical support : While a conceptual framework can provide a theoretical basis for a research project, it may not be supported by empirical evidence. This can limit the usefulness of a conceptual framework in guiding empirical research.

- Narrow focus: A conceptual framework can provide a clear focus for a research project, but it may also limit the scope of the investigation. This can make it difficult to address broader research questions or to consider alternative perspectives.

- Over-simplification: A conceptual framework can help to organize and structure research ideas, but it may also over-simplify complex phenomena. This can limit the depth of the investigation and the richness of the data collected.

- Inflexibility : A conceptual framework can provide a structure for organizing research ideas, but it may also be inflexible in the face of new data or unexpected findings. This can limit the ability of researchers to adapt their research project to new information or changing circumstances.

- Difficulty in development : Developing a conceptual framework can be a challenging and time-consuming process. It requires a thorough understanding of existing theory or conceptual models, and may require collaboration with other researchers.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Make a Conceptual Framework

- 6-minute read

- 2nd January 2022

What is a conceptual framework? And why is it important?

A conceptual framework illustrates the relationship between the variables of a research question. It’s an outline of what you’d expect to find in a research project.

Conceptual frameworks should be constructed before data collection and are vital because they map out the actions needed in the study. This should be the first step of an undergraduate or graduate research project.

What Is In a Conceptual Framework?

In a conceptual framework, you’ll find a visual representation of the key concepts and relationships that are central to a research study or project . This can be in form of a diagram, flow chart, or any other visual representation. Overall, a conceptual framework serves as a guide for understanding the problem being studied and the methods being used to investigate it.

Steps to Developing the Perfect Conceptual Framework

- Pick a question

- Conduct a literature review

- Identify your variables

- Create your conceptual framework

1. Pick a Question

You should already have some idea of the broad area of your research project. Try to narrow down your research field to a manageable topic in terms of time and resources. From there, you need to formulate your research question. A research question answers the researcher’s query: “What do I want to know about my topic?” Research questions should be focused, concise, arguable and, ideally, should address a topic of importance within your field of research.

An example of a simple research question is: “What is the relationship between sunny days and ice cream sales?”

2. Conduct a Literature Review

A literature review is an analysis of the scholarly publications on a chosen topic. To undertake a literature review, search for articles with the same theme as your research question. Choose updated and relevant articles to analyze and use peer-reviewed and well-respected journals whenever possible.

For the above example, the literature review would investigate publications that discuss how ice cream sales are affected by the weather. The literature review should reveal the variables involved and any current hypotheses about this relationship.

3. Identify Your Variables

There are two key variables in every experiment: independent and dependent variables.

Independent Variables

The independent variable (otherwise known as the predictor or explanatory variable) is the expected cause of the experiment: what the scientist changes or changes on its own. In our example, the independent variable would be “the number of sunny days.”

Dependent Variables

The dependent variable (otherwise known as the response or outcome variable) is the expected effect of the experiment: what is being studied or measured. In our example, the dependent variable would be “the quantity of ice cream sold.”

Next, there are control variables.

Control Variables

A control variable is a variable that may impact the dependent variable but whose effects are not going to be measured in the research project. In our example, a control variable could be “the socioeconomic status of participants.” Control variables should be kept constant to isolate the effects of the other variables in the experiment.

Finally, there are intervening and extraneous variables.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Intervening Variables

Intervening variables link the independent and dependent variables and clarify their connection. In our example, an intervening variable could be “temperature.”

Extraneous Variables

Extraneous variables are any variables that are not being investigated but could impact the outcomes of the study. Some instances of extraneous variables for our example would be “the average price of ice cream” or “the number of varieties of ice cream available.” If you control an extraneous variable, it becomes a control variable.

4. Create Your Conceptual Framework

Having picked your research question, undertaken a literature review, and identified the relevant variables, it’s now time to construct your conceptual framework. Conceptual frameworks are clear and often visual representations of the relationships between variables.

We’ll start with the basics: the independent and dependent variables.

Our hypothesis is that the quantity of ice cream sold directly depends on the number of sunny days; hence, there is a cause-and-effect relationship between the independent variable (the number of sunny days) and the dependent and independent variable (the quantity of ice cream sold).

Next, introduce a control variable. Remember, this is anything that might directly affect the dependent variable but is not being measured in the experiment:

Finally, introduce the intervening and extraneous variables.

The intervening variable (temperature) clarifies the relationship between the independent variable (the number of sunny days) and the dependent variable (the quantity of ice cream sold). Extraneous variables, such as the average price of ice cream, are variables that are not controlled and can potentially impact the dependent variable.

Are Conceptual Frameworks and Research Paradigms the Same?

In simple terms, the research paradigm is what informs your conceptual framework. In defining our research paradigm we ask the big questions—Is there an objective truth and how can we understand it? If we decide the answer is yes, we may be working with a positivist research paradigm and will choose to build a conceptual framework that displays the relationship between fixed variables. If not, we may be working with a constructivist research paradigm, and thus our conceptual framework will be more of a loose amalgamation of ideas, theories, and themes (a qualitative study). If this is confusing–don’t worry! We have an excellent blog post explaining research paradigms in more detail.

Where is the Conceptual Framework Located in a Thesis?

This will depend on your discipline, research type, and school’s guidelines, but most papers will include a section presenting the conceptual framework in the introduction, literature review, or opening chapter. It’s best to present your conceptual framework after presenting your research question, but before outlining your methodology.

Can a Conceptual Framework be Used in a Qualitative Study?

Yes. Despite being less clear-cut than a quantitative study, all studies should present some form of a conceptual framework. Let’s say you were doing a study on care home practices and happiness, and you came across a “happiness model” constructed by a relevant theorist in your literature review. Your conceptual framework could be an outline or a visual depiction of how you will use this model to collect and interpret qualitative data for your own study (such as interview responses). Check out this useful resource showing other examples of conceptual frameworks for qualitative studies .

Expert Proofreading for Researchers

Whether you’re a seasoned academic or not, you will want your research paper to be error-free and fluently written. That’s where proofreading comes in. Our editors are on hand 24 hours a day to ensure your writing is concise, clear, and precise. Submit a free sample of your writing today to try our services.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

The Plagiarism Checker Online For Your Academic Work

Start Plagiarism Check

Editing & Proofreading for Your Research Paper

Get it proofread now

Online Printing & Binding with Free Express Delivery

Configure binding now

- Academic essay overview

- The writing process

- Structuring academic essays

- Types of academic essays

- Academic writing overview

- Sentence structure

- Academic writing process

- Improving your academic writing

- Titles and headings

- APA style overview

- APA citation & referencing

- APA structure & sections

- Citation & referencing

- Structure and sections

- APA examples overview

- Commonly used citations

- Other examples

- British English vs. American English

- Chicago style overview

- Chicago citation & referencing

- Chicago structure & sections

- Chicago style examples

- Citing sources overview

- Citation format

- Citation examples

- College essay overview

- Application

- How to write a college essay

- Types of college essays

- Commonly confused words

- Definitions

- Dissertation overview

- Dissertation structure & sections

- Dissertation writing process

- Graduate school overview

- Application & admission

- Study abroad

- Master degree

- Harvard referencing overview

- Language rules overview

- Grammatical rules & structures

- Parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Methodology overview

- Analyzing data

- Experiments

- Observations

- Inductive vs. Deductive

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative

- Types of validity

- Types of reliability

- Sampling methods

- Theories & Concepts

- Types of research studies

- Types of variables

- MLA style overview

- MLA examples

- MLA citation & referencing

- MLA structure & sections

- Plagiarism overview

- Plagiarism checker

- Types of plagiarism

- Printing production overview

- Research bias overview

- Types of research bias

- Example sections

- Types of research papers

- Research process overview

- Problem statement

- Research proposal

- Research topic

- Statistics overview

- Levels of measurment

- Frequency distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Measures of variability

- Hypothesis testing

- Parameters & test statistics

- Types of distributions

- Correlation

- Effect size

- Hypothesis testing assumptions

- Types of ANOVAs

- Types of chi-square

- Statistical data

- Statistical models

- Spelling mistakes

- Tips overview

- Academic writing tips

- Dissertation tips

- Sources tips

- Working with sources overview

- Evaluating sources

- Finding sources

- Including sources

- Types of sources

Your Step to Success

Plagiarism Check within 10min

Printing & Binding with 3D Live Preview

Conceptual Framework – How to Develop it for Research

How do you like this article cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

In academic writing, a conceptual framework serves as a key component of the research methodology , providing a schematic representation of the concepts and their proposed relationships. This tool not only guides data collection and interpretation but also clarifies the research question and hypothesis. The conceptual framework aims to make research conclusions more meaningful and generalizable. It outlines the purpose and the importance of the research topic .

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Conceptual Framework – In a Nutshell

- 2 Definition: Conceptual framework

- 3 Conceptual framework: Independent vs. Dependent variables

- 4 Conceptual framework: Moderating variables

- 5 Conceptual framework: Mediating variables

- 6 Conceptual framework: Control variables

Conceptual Framework – In a Nutshell

- The conceptual framework is a model used to show the relationship between the independent vs. dependent variables in a research problem .

- Researchers consider several variables in a conceptual framework, including control variables, mediating variables, and monitoring variables.

- It is important to identify control variables in a conceptual framework to minimize their effect on the findings of a study.

Definition: Conceptual framework

A conceptual framework is a visual model that illustrates the anticipated relationship between the cause and effect variables. It highlights the research goals and creates a layout of their relationship to form meaningful conclusions. The conceptual framework is usually drawn from the literature review during the early stages of research to form appropriate research questions .

Conceptual framework: Independent vs. Dependent variables

Researchers define independent vs. dependent variables to test for cause and effect when developing a conceptual framework.

Example of dependent vs. independent variables

You want to investigate whether drivers with more experience are involved in fewer accidents.

- Hypothesis: The more experience a driver has, the fewer accidents they are likely to be involved in .

- Independent variable: The years of experience

- Dependent variable: The expected cause and the number of accidents

Unlike above, causal relationships in a conceptual framework usually have more than one independent variable .

Conceptual framework: Moderating variables

Moderating variables influence the strength of the relationship between two variables in a conceptual framework. They are used to determine the external validity of the research conclusions based on their ability to strengthen, negate or otherwise affect the association between the independent vs. dependent variables.

Moderating variables are helpful in a conceptual framework because they illustrate the relationship between different variables in a research topic .

Income levels can predict general happiness, although the relationship may be stronger for younger people than for older workers. Age is the moderating variable in this conceptual framework.

Moderators can be divided into categorical variables such as religion, blood group, or race and quantitative variables like height, age, and income.

In our study of drivers’ experience and accidents, we can introduce age as the moderating variable. In this case, a driver’s age can influence the effect of years of experience on the number of accidents. The researcher expects that ‘age’ moderates the effect of experience on road safety.

Conceptual framework: Mediating variables

A conceptual framework also takes mediating variables into account. They illustrate the impact of an independent variable on a dependent variable by showing how and why the effect occurs. A variable is considered a mediator if:

- It is caused by an independent variable.

- It affects the dependent variable.

- The statistical correlation between the dependent and the independent variable is more significant when it is considered than when it’s not.

Researchers use mediation analysis to test if a variable is a mediator using ANOVA and linear regression analysis. ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) tests the presence and strength of the statistical differences between the means calculated from several independent samples.

ANOVA: Determines the effects of age, gender, and disposable income on average consumer spending per month.

Linear regression: Predicts the value of a dependent variable based on the value of the independent variable.

The main aims of linear regression in a conceptual framework are to test the effectiveness of a group of predictor values in predicting a result and identifying the significant predictors of the outcome.

An individual’s body weight has a linear relationship with their weight. The researcher expects that as the height of the person increases, their weight increases. A set of observations can be plotted on a scatter plot to illustrate the strength of the correlation between the variables.

Conceptual framework: Control variables

Control variables are also considered in the conceptual framework. They define factors controlled by the researcher as it may affect the findings of a study even though it is of no interest to the researcher when designing a conceptual framework.

Control variables are used to improve the validity of a research study by reducing the effect of other variables outside the scope of the study. They help researchers to determine the relationship between the key variables under observation.

Control variables can be managed directly by keeping them constant, for instance choosing participants within the same age group. They can also be managed indirectly by using random samples to reduce their effect.

Example of control variables in the conceptual framework

In our study of driver’s experience and accident rates, the weather may affect the rate of accidents. However, our primary focus is not on the relationship between the weather and accident rates, although it may affect the findings of our study. Therefore, The ‘weather’ is added as a control variable in our conceptual framework.

If a researcher fails to control some variables, it may be difficult to prove that they did not affect the research outcome. Control variables are used in experimental research to guarantee that the observable results are exclusively caused by the experimental design.

Variables in a conceptual framework can be controlled by:

- Random assignment – Selecting random groups ensures there are no identifiable differences, which may skew your conclusions.

- Statistical controls – You can isolate the effects of the control variable by measuring and controlling it.

- Standardized procedures – Researchers should ensure the same methods are applied in all the groups in a study. Only the independent variables should be altered across groups to observe how they affect the dependent variable.

What is the conceptual framework in research?

It is an illustration of the relationship between variables in a study. It is used to form the hypothesis that guides the methods of research.

What are control variables?

Control variables are factors that are directly or indirectly controlled by the researchers. They are extraneous variables that may affect the observations in a study.

Where are conceptual frameworks used?

Conceptual frameworks are used in multiple social sciences and humanities. They help in formulating and investigating the research problem.

What is a moderating variable in a conceptual framework?

A moderating variable influences the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable. It is used to measure the impact of an additional variable on the dependent-independent variable relationship.

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience.

- External Media

Individual Privacy Preferences

Cookie Details Privacy Policy Imprint

Here you will find an overview of all cookies used. You can give your consent to whole categories or display further information and select certain cookies.

Accept all Save

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us to understand how our visitors use our website.

Content from video platforms and social media platforms is blocked by default. If External Media cookies are accepted, access to those contents no longer requires manual consent.

Privacy Policy Imprint

Development of Conceptual Models to Guide Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy: Synthesizing Traditional and Contemporary Paradigms

Collaborators.

- Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium : Elizabeth Mueller , Colleen M Fitzgerald , Cecilia T Hardacker , Jeni Hebert-Beirne , Missy Lavender , David A Shoham , Kathryn Burgio , Alayne Markland , Gerald McGwin , Beverly Williams , Emily S Lukacz , D Yvette LaCoursiere , Jesse N Nodora , Janis M Miller , Lawrence Chin-I An , Lisa Kane Low , Diane Kaschak Newman , Amanda Berry , C Neill Epperson , Kathryn H Schmitz , Ariana L Smith , Jean Wyman , Siobhan Sutcliffe , Colleen McNicholas , Aimee James , Jerry Lowder , Leslie Rickey , Deepa Camenga , Shayna D Cunningham , Toby Chai , Jessica B Lewis , Bernard Harlow , Kyle Rudser , John Connett , Haitao Chu , Cynthia Fok , Todd Rockwood , Melissa Constantine

Affiliations

- 1 University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

- 2 University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

- 3 University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA.

- 4 Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT, USA.

- 5 Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

- 6 University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

- 7 University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

- PMID: 31910039

- PMCID: PMC7869957

- DOI: 10.1177/1524839919890869

This applied paper is intended to serve as a "how to" guide for public health researchers, practitioners, and policy makers who are interested in building conceptual models to convey their ideas to diverse audiences. Conceptual models can provide a visual representation of specific research questions. They also can show key components of programs, practices, and policies designed to promote health. Conceptual models may provide improved guidance for prevention and intervention efforts if they are based on frameworks that integrate social ecological and biological influences on health and incorporate health equity and social justice principles. To enhance understanding and utilization of this guide, we provide examples of conceptual models developed by the P revention of L ower U rinary Tract S ymptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium. PLUS is a transdisciplinary U.S. scientific network established by the National Institutes of Health in 2015 to promote bladder health and prevent lower urinary tract symptoms, an emerging public health and prevention priority. The PLUS Research Consortium is developing conceptual models to guide its prevention research agenda. Research findings may in turn influence future public health practices and policies. This guide can assist others in framing diverse public health and prevention science issues in innovative, potentially transformative ways.

Keywords: bladder health; conceptual framework; conceptual model; lower urinary tract symptoms; social ecology; theory.

Publication types

- Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural

- Health Equity*

- Health Policy

- Health Promotion

- Health Services Research / trends*

- Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms / prevention & control*

- Public Health*

- Social Justice

- Urinary Bladder

Grants and funding

- U24 DK106786/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

- U01 DK106858/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

- U01 DK106786/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

- U01 DK106892/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

- U01 DK106853/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

- U01 DK106893/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

- U01 DK106827/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

- U01 DK106908/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

- U01 DK106898/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Conceptual Models

What are conceptual models.

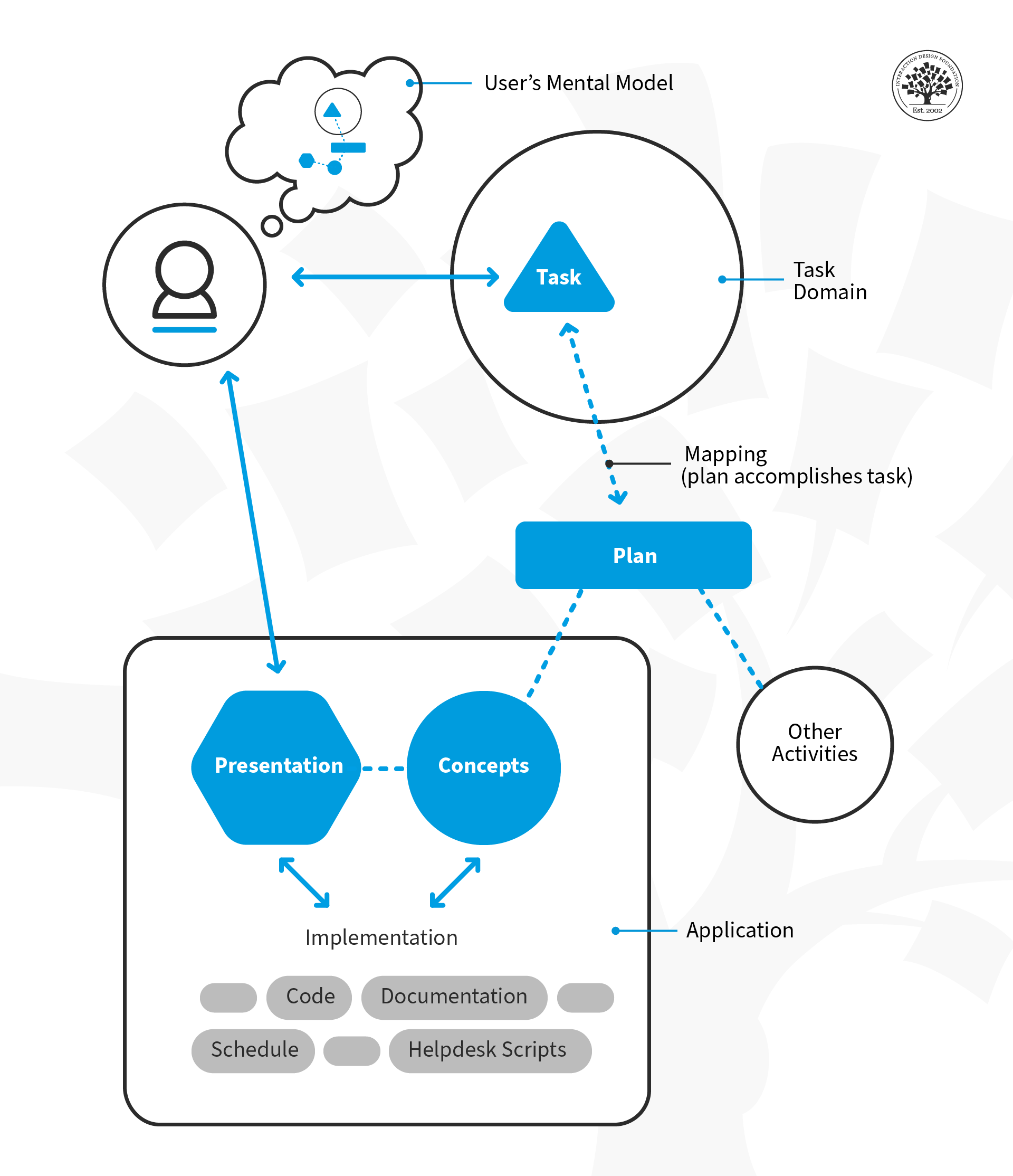

Conceptual models are abstract, psychological representations of how tasks should be carried out. People use conceptual models subconsciously and intuitively as a way of systematizing processes.

For example, a common mental model for creating appointments involves calendars and diaries. Knowing about the prevalence and power of conceptual models guides designers to tailor software that matches users’ conceptual models.

By creating interfaces and apps that echo conceptual models, designers build on existing knowledge and frameworks, making it easier for the users to learn how to use the new product.

Typically, conceptual models are identified at the beginning of the design process and are referenced to constantly for direction and inspiration throughout the design process.

Questions related to Conceptual Models

Conceptual models provide a framework for users to grasp system functionalities. In the MatchDog project, a conceptual model was developed for a matchmaking app for dog owners. It includes user profiles, dog profiles, a chat system, and event creation, simulating real-life dog meetups. This model ensures that the app mirrors real-world interactions, making it intuitive for users. For a comprehensive look into the product and benefits of the MatchDog project's conceptual model, explore the full article on Interaction Design Foundation.

Conceptual modeling in UX encompasses three main types: Mental Models , based on individual users' internal cognitive processes and perceptions; Represented Models , which designers create to display the functionality and content of systems; and System Images , stemming from the system's physical and digital representation, including interfaces and documentation. These models ensure that users and designers share understanding, facilitating seamless system interactions. Dive deeper into conceptual modeling for mobile applications with Interaction Design Foundation.

In UX design, a conceptual model provides a mental framework that users rely on to predict and understand a system's functionality. It bridges the gap between user expectations and the product's functions, ensuring an intuitive user experience. The shopping cart in ecommerce sites is perhaps the most common example of a conceptual model. Users have a set of expectations on its behavior from their experience in the real world. A well-defined conceptual model aligns with users' mental models, minimizing confusion and enhancing usability. Dive deeper into the intricacies of conceptual modeling for mobile applications on Interaction Design Foundation.

A conceptual model in UX design consists of several key elements:

Entities: the people, places, and things that are involved in the system or product. They are the main components that users interact with or manipulate. For example, in a word processor, the entities are the documents, fonts, images, etc.

Relationships: how the entities are connected or related to each other. They define the rules and logic of the system or product. For example, in a word processor, the relationships are how the documents can be saved, opened, edited, printed, etc.

Constraints: the limitations or restrictions that apply to the entities or relationships. They define the boundaries and conditions of the system or product. For example, in a word processor, the constraints are the file formats, storage space, printing options, etc.

These elements create a mental framework for users, guiding their expectations and interactions with a system. For a deeper insight into conceptual modeling for mobile applications , visit Interaction Design Foundation.