- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Graphical Abstracts and Tidbit

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About American Journal of Hypertension

- Editorial Board

- Board of Directors

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- AJH Summer School

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Clinical management and treatment decisions, hypertension in black americans, pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in black americans.

- < Previous

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Suzanne Oparil, Case study, American Journal of Hypertension , Volume 11, Issue S8, November 1998, Pages 192S–194S, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-7061(98)00195-2

- Permissions Icon Permissions

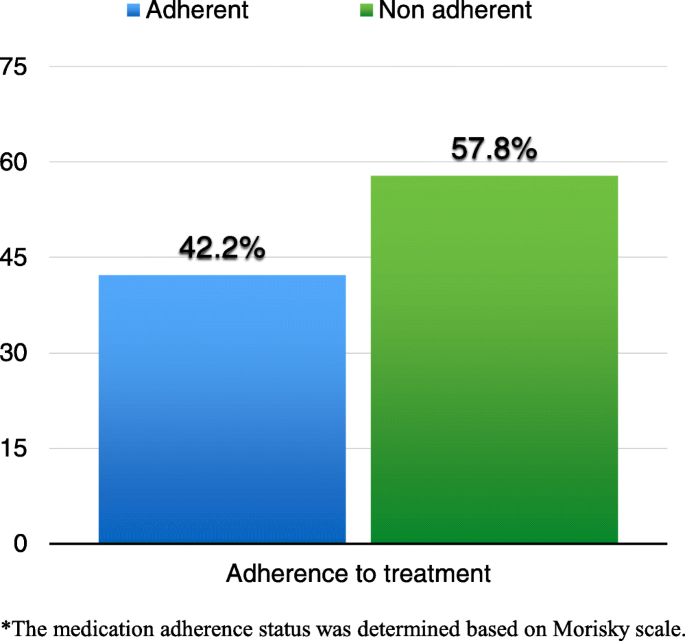

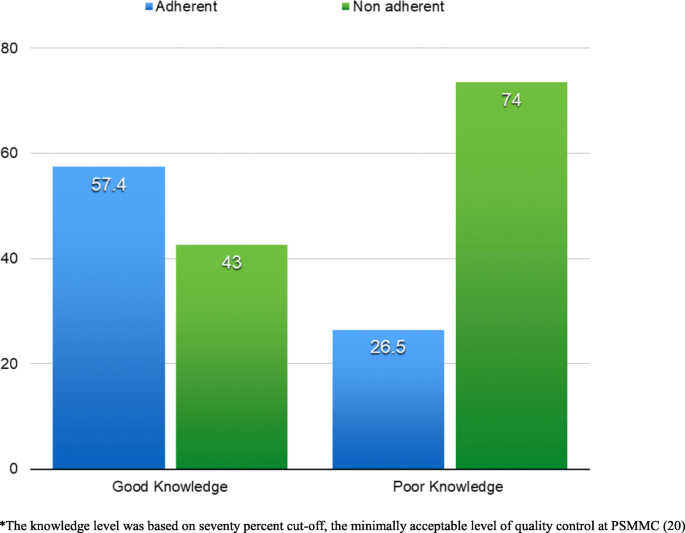

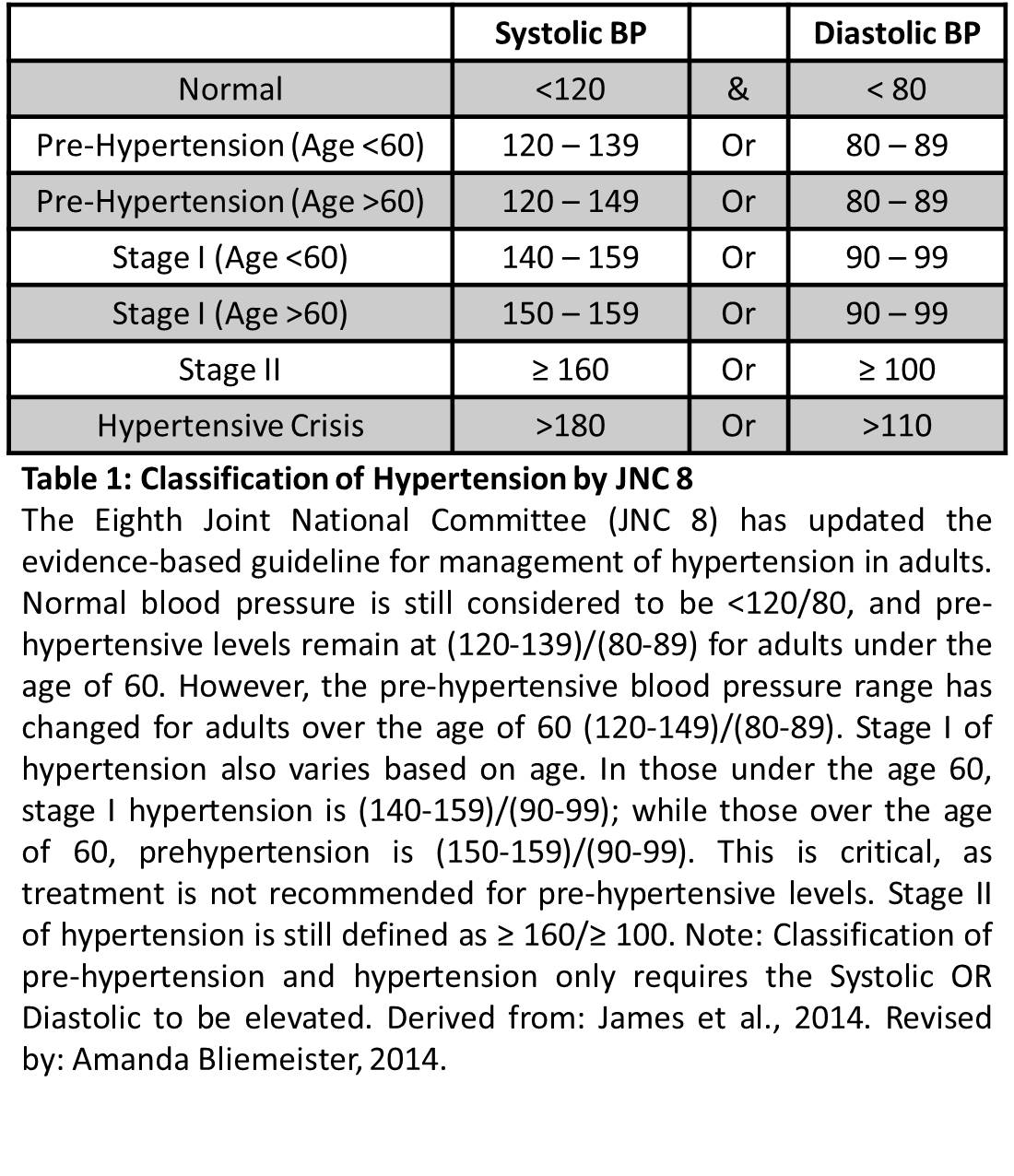

Ms. C is a 42-year-old black American woman with a 7-year history of hypertension first diagnosed during her last pregnancy. Her family history is positive for hypertension, with her mother dying at 56 years of age from hypertension-related cardiovascular disease (CVD). In addition, both her maternal and paternal grandparents had CVD.

At physician visit one, Ms. C presented with complaints of headache and general weakness. She reported that she has been taking many medications for her hypertension in the past, but stopped taking them because of the side effects. She could not recall the names of the medications. Currently she is taking 100 mg/day atenolol and 12.5 mg/day hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), which she admits to taking irregularly because “... they bother me, and I forget to renew my prescription.” Despite this antihypertensive regimen, her blood pressure remains elevated, ranging from 150 to 155/110 to 114 mm Hg. In addition, Ms. C admits that she has found it difficult to exercise, stop smoking, and change her eating habits. Findings from a complete history and physical assessment are unremarkable except for the presence of moderate obesity (5 ft 6 in., 150 lbs), minimal retinopathy, and a 25-year history of smoking approximately one pack of cigarettes per day. Initial laboratory data revealed serum sodium 138 mEq/L (135 to 147 mEq/L); potassium 3.4 mEq/L (3.5 to 5 mEq/L); blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 19 mg/dL (10 to 20 mg/dL); creatinine 0.9 mg/dL (0.35 to 0.93 mg/dL); calcium 9.8 mg/dL (8.8 to 10 mg/dL); total cholesterol 268 mg/dL (< 245 mg/dL); triglycerides 230 mg/dL (< 160 mg/dL); and fasting glucose 105 mg/dL (70 to 110 mg/dL). The patient refused a 24-h urine test.

Taking into account the past history of compliance irregularities and the need to take immediate action to lower this patient’s blood pressure, Ms. C’s pharmacologic regimen was changed to a trial of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor enalapril, 5 mg/day; her HCTZ was discontinued. In addition, recommendations for smoking cessation, weight reduction, and diet modification were reviewed as recommended by the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI). 1

After a 3-month trial of this treatment plan with escalation of the enalapril dose to 20 mg/day, the patient’s blood pressure remained uncontrolled. The patient’s medical status was reviewed, without notation of significant changes, and her antihypertensive therapy was modified. The ACE inhibitor was discontinued, and the patient was started on the angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB) losartan, 50 mg/day.

After 2 months of therapy with the ARB the patient experienced a modest, yet encouraging, reduction in blood pressure (140/100 mm Hg). Serum electrolyte laboratory values were within normal limits, and the physical assessment remained unchanged. The treatment plan was to continue the ARB and reevaluate the patient in 1 month. At that time, if blood pressure control remained marginal, low-dose HCTZ (12.5 mg/day) was to be added to the regimen.

Hypertension remains a significant health problem in the United States (US) despite recent advances in antihypertensive therapy. The role of hypertension as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is well established. 2–7 The age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension in non-Hispanic black Americans is approximately 40% higher than in non-Hispanic whites. 8 Black Americans have an earlier onset of hypertension and greater incidence of stage 3 hypertension than whites, thereby raising the risk for hypertension-related target organ damage. 1 , 8 For example, hypertensive black Americans have a 320% greater incidence of hypertension-related end-stage renal disease (ESRD), 80% higher stroke mortality rate, and 50% higher CVD mortality rate, compared with that of the general population. 1 , 9 In addition, aging is associated with increases in the prevalence and severity of hypertension. 8

Research findings suggest that risk factors for coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke, particularly the role of blood pressure, may be different for black American and white individuals. 10–12 Some studies indicate that effective treatment of hypertension in black Americans results in a decrease in the incidence of CVD to a level that is similar to that of nonblack American hypertensives. 13 , 14

Data also reveal differences between black American and white individuals in responsiveness to antihypertensive therapy. For instance, studies have shown that diuretics 15 , 16 and the calcium channel blocker diltiazem 16 , 17 are effective in lowering blood pressure in black American patients, whereas β-adrenergic receptor blockers and ACE inhibitors appear less effective. 15 , 16 In addition, recent studies indicate that ARB may also be effective in this patient population.

Angiotensin-II receptor blockers are a relatively new class of agents that are approved for the treatment of hypertension. Currently, four ARB have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, and valsartan. Recently, a 528-patient, 26-week study compared the efficacy of eprosartan (200 to 300 mg/twice daily) versus enalapril (5 to 20 mg/daily) in patients with essential hypertension (baseline sitting diastolic blood pressure [DBP] 95 to 114 mm Hg). After 3 to 5 weeks of placebo, patients were randomized to receive either eprosartan or enalapril. After 12 weeks of therapy within the titration phase, patients were supplemented with HCTZ as needed. In a prospectively defined subset analysis, black American patients in the eprosartan group (n = 21) achieved comparable reductions in DBP (−13.3 mm Hg with eprosartan; −12.4 mm Hg with enalapril) and greater reductions in systolic blood pressure (SBP) (−23.1 with eprosartan; −13.2 with enalapril), compared with black American patients in the enalapril group (n = 19) ( Fig. 1 ). 18 Additional trials enrolling more patients are clearly necessary, but this early experience with an ARB in black American patients is encouraging.

Efficacy of the angiotensin II receptor blocker eprosartan in black American with mild to moderate hypertension (baseline sitting DBP 95 to 114 mm Hg) in a 26-week study. Eprosartan, 200 to 300 mg twice daily (n = 21, solid bar), enalapril 5 to 20 mg daily (n = 19, diagonal bar). †10 of 21 eprosartan patients and seven of 19 enalapril patients also received HCTZ. Adapted from data in Levine: Subgroup analysis of black hypertensive patients treated with eprosartan or enalapril: results of a 26-week study, in Programs and abstracts from the 1st International Symposium on Angiotensin-II Antagonism, September 28–October 1, 1997, London, UK.

00195-2/2/m_ajh.192S.f1.jpeg?Expires=1717633455&Signature=VDkVx8235MsdQ81LvKEYaNheAZ3Jv-LOAB25L1xrbZ6-STHDcu32hKPlJW5VtPDRDNPtACHzadY2jZ16L8lgnpzCfezVXcCa-mTZuitHsXy9oMFoRkLL5qS9BgBkfrinKvLfZV9Py8250Spe7lo7Z7bOIcW97~3TOu33DVA4DCDz4hIA1qsEcuB4PK8eqnmjBvIaPwOi3zmYVMtgHILtxEOvSxU6hRPOeOottzDa2fdKDECOI33Dt7DBh3lumaEOhIAIgwlzOmNzyTlT0GBXMnxI0WRgO3ABjLXGd7tUv~mX7-TIyjOgfVgyvJvIQU9eWvkMsAieWhUdNHXlLyUArw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Approximately 30% of all deaths in hypertensive black American men and 20% of all deaths in hypertensive black American women are attributable to high blood pressure. Black Americans develop high blood pressure at an earlier age, and hypertension is more severe in every decade of life, compared with whites. As a result, black Americans have a 1.3 times greater rate of nonfatal stroke, a 1.8 times greater rate of fatal stroke, a 1.5 times greater rate of heart disease deaths, and a 5 times greater rate of ESRD when compared with whites. 19 Therefore, there is a need for aggressive antihypertensive treatment in this group. Newer, better tolerated antihypertensive drugs, which have the advantages of fewer adverse effects combined with greater antihypertensive efficacy, may be of great benefit to this patient population.

1. Joint National Committee : The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure . Arch Intern Med 1997 ; 24 157 : 2413 – 2446 .

Google Scholar

2. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension: Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg . JAMA 1967 ; 202 : 116 – 122 .

3. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension: II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg . JAMA 1970 ; 213 : 1143 – 1152 .

4. Pooling Project Research Group : Relationship of blood pressure, serum cholesterol, smoking habit, relative weight and ECG abnormalities to the incidence of major coronary events: Final report of the pooling project . J Chronic Dis 1978 ; 31 : 201 – 306 .

5. Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program Cooperative Group : Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program: I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension . JAMA 1979 ; 242 : 2562 – 2577 .

6. Kannel WB , Dawber TR , McGee DL : Perspectives on systolic hypertension: The Framingham Study . Circulation 1980 ; 61 : 1179 – 1182 .

7. Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program Cooperative Group : The effect of treatment on mortality in “mild” hypertension: Results of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program . N Engl J Med 1982 ; 307 : 976 – 980 .

8. Burt VL , Whelton P , Roccella EJ et al. : Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population: Results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991 . Hypertension 1995 ; 25 : 305 – 313 .

9. Klag MJ , Whelton PK , Randall BL et al. : End-stage renal disease in African-American and white men: 16-year MRFIT findings . JAMA 1997 ; 277 : 1293 – 1298 .

10. Neaton JD , Kuller LH , Wentworth D et al. : Total and cardiovascular mortality in relation to cigarette smoking, serum cholesterol concentration, and diastolic blood pressure among black and white males followed up for five years . Am Heart J 1984 ; 3 : 759 – 769 .

11. Gillum RF , Grant CT : Coronary heart disease in black populations II: Risk factors . Heart J 1982 ; 104 : 852 – 864 .

12. M’Buyamba-Kabangu JR , Amery A , Lijnen P : Differences between black and white persons in blood pressure and related biological variables . J Hum Hypertens 1994 ; 8 : 163 – 170 .

13. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group : Five-year findings of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program: mortality by race-sex and blood pressure level: a further analysis . J Community Health 1984 ; 9 : 314 – 327 .

14. Ooi WL , Budner NS , Cohen H et al. : Impact of race on treatment response and cardiovascular disease among hypertensives . Hypertension 1989 ; 14 : 227 – 234 .

15. Weinberger MH : Racial differences in antihypertensive therapy: evidence and implications . Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1990 ; 4 ( suppl 2 ): 379 – 392 .

16. Materson BJ , Reda DJ , Cushman WC et al. : Single-drug therapy for hypertension in men: A comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo . N Engl J Med 1993 ; 328 : 914 – 921 .

17. Materson BJ , Reda DJ , Cushman WC for the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Department of Veterans Affairs single-drug therapy of hypertension study: Revised figures and new data . Am J Hypertens 1995 ; 8 : 189 – 192 .

18. Levine B : Subgroup analysis of black hypertensive patients treated with eprosartan or enalapril: results of a 26-week study , in Programs and abstracts from the first International Symposium on Angiotensin-II Antagonism , September 28 – October 1 , 1997 , London, UK .

19. American Heart Association: 1997 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update . American Heart Association , Dallas , 1997 .

- hypertension

- blood pressure

- african american

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1941-7225

- Copyright © 2024 American Journal of Hypertension, Ltd.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Newly diagnosed hypertension: case study

Affiliation.

- 1 Trainee Advanced Nurse Practitioner, East Belfast GP Federation, Northern Ireland.

- PMID: 37344134

- DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2023.32.12.556

The role of an advanced nurse practitioner encompasses the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of a range of conditions. This case study presents a patient with newly diagnosed hypertension. It demonstrates effective history taking, physical examination, differential diagnoses and the shared decision making which occurred between the patient and the professional. It is widely acknowledged that adherence to medications is poor in long-term conditions, such as hypertension, but using a concordant approach in practice can optimise patient outcomes. This case study outlines a concordant approach to consultations in clinical practice which can enhance adherence in long-term conditions.

Keywords: Adherence; Advanced nurse practitioner; Case study; Concordance; Hypertension.

- Diagnosis, Differential

- Hypertension* / diagnosis

- Hypertension* / drug therapy

- Nurse Practitioners*

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 05 July 2022

Update on Hypertension Research in 2021

- Masaki Mogi 1 ,

- Tatsuya Maruhashi 2 ,

- Yukihito Higashi 2 , 3 ,

- Takahiro Masuda 4 ,

- Daisuke Nagata 4 ,

- Michiaki Nagai 5 ,

- Kanako Bokuda 6 ,

- Atsuhiro Ichihara 6 ,

- Yoichi Nozato 7 ,

- Ayumi Toba 8 ,

- Keisuke Narita 9 ,

- Satoshi Hoshide 9 ,

- Atsushi Tanaka 10 ,

- Koichi Node 10 ,

- Yuichi Yoshida 11 ,

- Hirotaka Shibata 11 ,

- Kenichi Katsurada 9 , 12 ,

- Masanari Kuwabara 13 ,

- Takahide Kodama 13 ,

- Keisuke Shinohara 14 &

- Kazuomi Kario 9

Hypertension Research volume 45 , pages 1276–1297 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

9295 Accesses

13 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

In 2021, 217 excellent manuscripts were published in Hypertension Research. Editorial teams greatly appreciate the authors’ contribution to hypertension research progress. Here, our editorial members have summarized twelve topics from published work and discussed current topics in depth. We hope you enjoy our special feature, “Update on Hypertension Research in 2021”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Genome-wide association studies

Two-year effects of semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 5 trial

Genome-wide analysis in over 1 million individuals of European ancestry yields improved polygenic risk scores for blood pressure traits

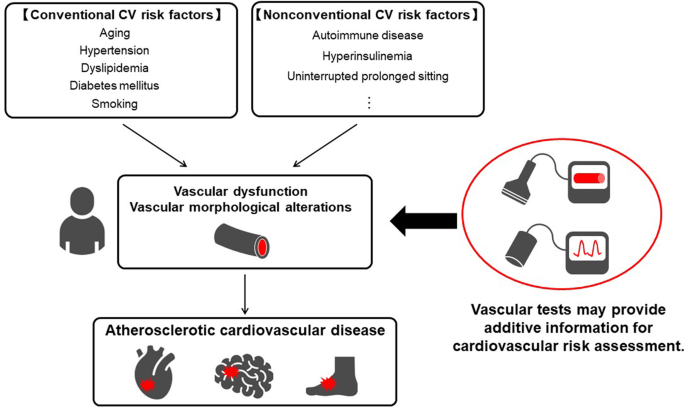

Usefulness of vascular function tests for cardiovascular risk assessment and a better understanding of the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis in hypertension (see supplementary information 1 ).

Vascular function tests and vascular imaging tests are useful for assessing the severity of atherosclerosis. Since vascular dysfunction and vascular morphological alterations are closely associated with the maintenance and progression of atherosclerosis, vascular tests may provide additional information for cardiovascular risk assessment (Fig. 1 ) [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Measurement of the ankle-brachial index (ABI) has been performed not only for screening for peripheral artery disease but also for cardiovascular risk assessment in clinical practice [ 6 ]. However, the ABI method does not always provide reliable data because the ABI value is falsely elevated despite the presence of occlusive arterial lesions in the lower extremities of patients with noncompressible lower limb arteries, which can lead to incorrect cardiovascular risk assessment [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Tsai et al. [ 10 ] reported that a combination of an ABI value <0.9 and an interleg ABI difference ≥0.17 was more useful for predicting all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality than was an ABI value <0.9 alone. Therefore, attention should be given not only to the ABI value but also to the interleg ABI difference for more precise cardiovascular risk assessment. Sang et al. [ 11 ] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the usefulness of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV), an index of arterial stiffness, for risk assessment and showed that higher baPWV was significantly associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality in patients with a history of coronary artery disease or stroke.

Vascular function tests and vascular imaging tests for the assessment of cardiovascular risk. CV cardiovascular

Vascular tests are also useful to achieve a better understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of cardiac disorders. Harada et al. [ 12 ] reported that short stature defined as height <155.0 cm was associated with low flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD), an index of endothelial function, in Japanese men, supporting the association between short stature and high risk of cardiovascular events [ 13 ]. Cassano et al. [Supplementary Information 1 - 1 ] reported that low levels of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) at baseline were associated with impaired endothelial function assessed by the reactive hyperemia index (RHI) and impaired arterial stiffness assessed by carotid-femoral PWV (cfPWV) at baseline and that EPC levels at baseline were also associated with longitudinal changes in RHI and cfPWV three years after the initiation of antihypertensive drug treatment in patients with hypertension. Murai et al. [Supplementary Information 1 - 2 ]. reported that a higher area under the curve value of insulin during a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test, but not insulin sensitivity indices, was significantly associated with higher baPWV in young Japanese subjects aged <40 years. Miyaoka et al. [ 14 ] reported that baPWV and central systolic blood pressure were significantly associated with renal microvascular damage assessed by using renal biopsy specimens in patients with nondiabetic kidney disease. Vila et al. [Supplementary Information 1 - 3 ] reported that carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) was significantly greater in male patients with autoimmune disease than in age-matched male controls without autoimmune disease, supporting a role for immune-mediated inflammation in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Li et al. [Supplementary Information 1 - 4 ] showed in a cross-sectional study that increased carotid IMT was significantly associated with cognitive impairment assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination in Chinese patients with hypertension, especially patients who were ≥60 years of age and patients with low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (<40 mg/dL).

Vascular function is profoundly affected by habitual behavior. Fryer et al. [Supplementary Information 1 - 5 ] reported that central arterial stiffness and peripheral arterial stiffness assessed by cfPWV and PWV β were more deteriorated by uninterrupted prolonged sitting (180 min) combined with prior high-fat meal consumption (61 g fat, 1066 kcal) than by uninterrupted prolonged sitting combined with prior low-fat meal consumption (10 g fat, 601 kcal) in healthy nonsmoking male subjects, suggesting that high-fat meal consumption should be avoided before uninterrupted prolonged sitting to prevent the progression of arterial stiffening. Yamaji et al. [ 15 ] reported that endothelial function assessed by FMD and vascular smooth muscle function assessed by nitroglycerine-induced vasodilation of the brachial artery were more impaired in patients without daily stair climbing activity than in patients who habitually climbed stairs to the ≥3 rd floor among patients with hypertension. Funakoshi et al. [ 16 ] reported that eating within 2 h before bedtime ≥3 days/week was associated with the development of hypertension defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg or initiation of antihypertensive drug treatment during an average follow-up period of 4.5 years in the general Japanese population, suggesting that avoiding late dinners may be helpful for preventing the development of hypertension. These findings indicate the importance of lifestyle modifications for maintaining vascular function and preventing the development of hypertension and the progression of atherosclerosis.

(TM and YH)

Keywords : vascular function, endothelial function, arterial stiffness, carotid intimathickness, ankle-brachial index.

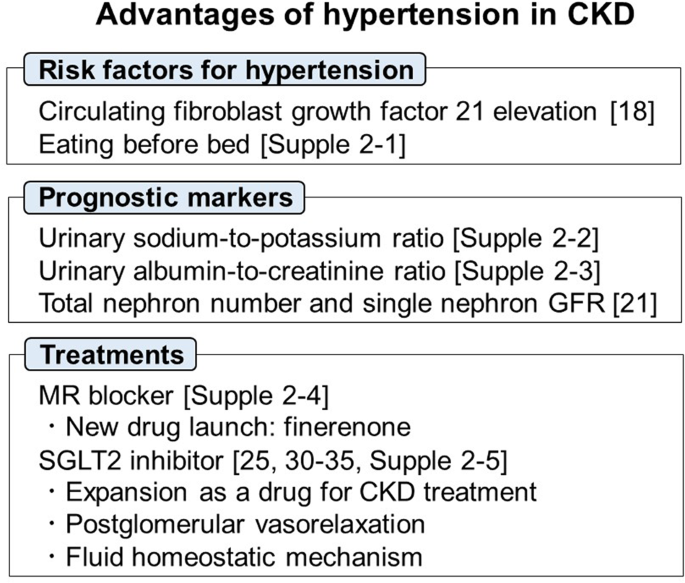

Advances in hypertension management for better renal outcomes (See Supplementary Information 2 )

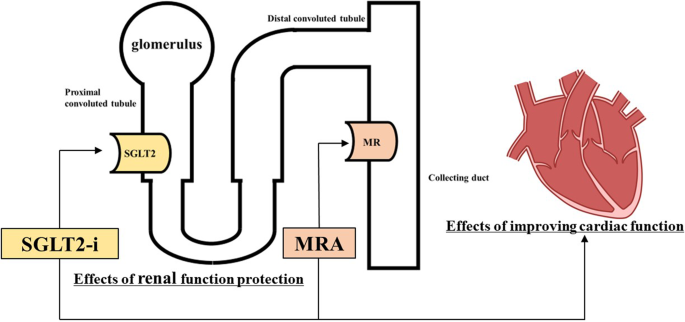

In chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients, hypertension is a risk factor for end-stage renal disease (ESRD), cardiovascular events and mortality. Thus, the prevention and appropriate management of hypertension in CKD patients are important strategies for preventing ESRD and cardiovascular disease (Fig. 2 ).

Advantages of hypertension in CKD. CKD chronic kidney disease, GFR glomerular filtration rate, MR mineralocorticoid receptor, SGLT2 sodium–glucose cotransporter 2

Risk factors for hypertension

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is an endocrine hormone that is mainly secreted by the liver. Circulating FGF21 levels are reported to be increased in CKD patients, while higher circulating FGF21 levels were reported to be associated with all-cause mortality in ESRD patients [ 17 , 18 ]. Additionally, Matsui et al. reported that higher circulating FGF21 levels partially mediate the association of elevated BP and/or aortic stiffness with renal dysfunction in middle-aged and older adults [ 19 ]. A study by Funakoshi et al. showed that eating before bed was correlated with the future risk of developing hypertension in the Iki Epidemiological Study of Atherosclerosis and Chronic Kidney Disease [Supplementary Information 2 - 1 ].

Prognostic markers

Several promising prognostic markers for renal and cardiovascular outcomes have been suggested. Matsukuma et al. reported that a higher urinary sodium-to-potassium ratio was independently associated with poor renal outcomes in patients with CKD [Supplementary Information 2 - 2 ]. Chinese hypertensive patients with higher albumin-to-creatinine ratios had a significantly increased risk of first ischemic stroke [Supplementary Information 2 - 3 ]. The number of nephrons in hypertensive patients was significantly lower than that in controls [ 20 ]. Tsuboi et al. suggested the usefulness of methods to estimate the total nephron count and single nephron GFR in living patients, which helped to tailor patient care depending on age or disease stage as well as to predict the response to therapy and the disease outcome [ 21 ].

Mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) blockers (e.g., esaxerenone) are used in the treatment of essential hypertension and hyperaldosteronism. Recently, a new MR antagonist, finerenone, has been introduced as a treatment for CKD patients with type 2 diabetes. However, hyperkalemia has been recognized as a potential side effect during treatment with MR blockers. A recent review article by Rakugi et al. suggested that being aware of at-risk patient groups, choosing appropriate dosages, and monitoring serum potassium during therapy are required to ensure the safe clinical use of these agents [Supplementary Information 2 - 4 ].

The clinical use of sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) has recently been expanded to nondiabetic patients with CKD and heart failure as well as diabetic patients [ 22 , 23 ]. Several novel findings regarding the renal protective properties of SGTL2is were reported in 2021. In a real-world registry study of Japanese type 2 diabetes patients with CKD, SGLT2is were associated with significantly better kidney outcomes in comparison to other glucose-lowering drugs, irrespective of the presence or absence of proteinuria [ 24 ]. Kitamura et al. reported that the addition of metformin to SGLT2is blunts the decrease in eGFR but that the coadministration of RAS inhibitors ameliorates this response [Supplementary Information 2 - 5 ]. Thomson and Vallon reported that (1) SGLT2i treatment reduces glomerular capillary pressure that is mediated through tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) and (2) the TGF response to SGLT2is involves preglomerular vasoconstriction and postglomerular vasorelaxation [ 25 ].

SGLT2is have an antihypertensive effect, which is greater in subjects with higher salt sensitivity and BMI [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]. Furthermore, the degree of BP change in patients undergoing SGLT2i therapy depends on the baseline BP; a larger reduction is observed in patients with higher baseline BP, and a smaller reduction or slight increase is observed in patients with lower baseline BP [ 29 ]. These BP regulation mechanisms may partially depend on body fluid homeostasis by SGLT2is. SGLT2is ameliorate fluid retention through osmotic diuresis and natriuresis but are associated with a low rate of hypovolemia [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ], which is evident by the compensatory upregulation of renin and vasopressin levels [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. These fluid homeostatic mechanisms exerted by SGLT2is may contribute to the stabilization of BP. Moreover, recent clinical studies have shown that SGLT2is reduce BP without changes in urinary sodium and fluid excretion or plasma volume [ 35 , 36 , 37 ], suggesting the role of other factors, such as the inhibition of the sympathetic nervous system, restoration of endothelial function, and reduction of arterial stiffness [ 38 , 39 ].

(TM and DN)

Keywords : fibroblast growth factor 21, nephron number, mineralocorticoid receptor blocker, SGLT2 inhibitor, fluid homeostasis.

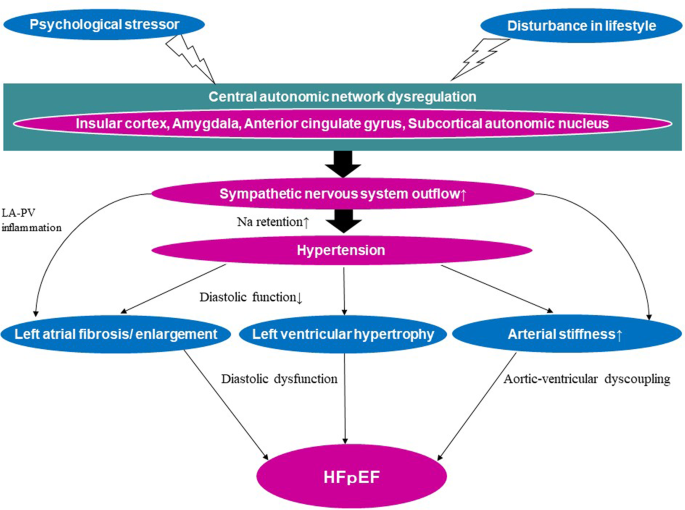

Hypertension and heart disease-focusing on the relationship with HFpEF (See Supplementary Information 3 )

With the increasing longevity of ‘Westernized’ populations, heart failure (HF) in the elderly has become a problem of growing scale and complexity worldwide [ 40 ].

Stages of HF are classified from A to D [ 41 ]. HF patients are also divided into patients with preserved ejection fraction (EF) (HFpEF), those with mildly reduced EF and those with reduced EF (HFrEF). Persistent hypertension and increased arterial stiffness in stage A HF result in left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (LVH), at which point it is classified as stage B HF. Although the etiology of HFpEF is diverse, patients with HFpEF have been reported to have a high prevalence of hypertension, which is closely associated with increased arterial stiffness, LVH and diastolic LV dysfunction [ 41 ].

In adult Sprague–Dawley rats, a novel flavoprotein, renalase, was increased in hypertrophic cardiac tissue, and recombinant renalase improved cardiac function and suppressed myocardial fibrosis in the HF model [ 42 ]. In stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats, carboxypeptidase X 2 (Cpxm2) was identified as a locus that affects LV mass. Analysis of endomyocardial biopsies from LVH patients showed significant upregulation of CPXM2 expression [ 43 ]. In this way, basic research applied to humans has shown in detail the pathophysiology of LVH.

Left atrial (LA) enlargement (LAe) is also associated with HFpEF [ 44 ]. In response to proinflammatory mediators, microvascular endothelial cells become inappropriately activated, resulting in microvascular endothelial dysfunction, perpetuating the inflammatory process and LA fibrosis [ 45 ]. Manifestations of these mechanisms have been related to LAe, which can be detected prior to the incidence of atrial fibrillation. Sympathetic overdrive from the central autonomic network, including the insular cortex, causes LA-pulmonary vein (PV) border fibrosis. LA-PV border fibrosis was suggested to originate from local inflammation triggered by preganglionic fibers ending in ganglionated plexi [ 45 , 46 ].

In the SPRINT study, intensive BP management was not associated with LA abnormalities defined based on ECG [ 47 ]. Although LA volume (LAV) according to body surface area was recommended to assess LA size [ 48 ], LAV indexed for height 2 was shown to be more sensitive for detecting subclinical hypertensive organ damage in females [ 49 ]. In the ARIC study, the minimum but not the maximum LAV index was significantly associated with the risk of incident HFpEF or death [ 50 ].

In the 2021 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the treatment of HFrEF, angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) are newly recommended for first-line treatment. In contrast, no guideline-directed treatment has been shown to convincingly reduce mortality and morbidity in HFpEF patients [ 44 ].

BP control is important to prevent adverse events in HFpEF patients with high BP. In a randomized study of hypertension patients, a significant reduction in systolic blood pressure (BP) (SBP) and diastolic BP was observed during daytime and nighttime in the ARNI group compared to the placebo group [ 51 ]. ARNI was also associated with reduced BP in patients with refractory hypertension with HFpEF [ 52 ]. In the PARAGON-HF trial, a decrease in pulse pressure, a marker of large arterial stiffness, during ARNI run-in was associated with a significant improvement in the prognosis of HFpEF [ 53 ]. On the other hand, the SACRA study showed that a significant reduction in BP occurred after adding SGLT2i to existing antihypertensive and antidiabetic agents in nonsevere obese diabetic elderly with uncontrolled nocturnal hypertension [ 54 ]. Recently, in the EMPEROR-Preserved Trial, SGLT2i improved the prognosis of patients with HFpEF [ 55 ]. From the above, it is suggested that reducing nighttime BP and improving diurnal BP patterns improves the prognosis of HFpEF [ 56 , 57 ].

Accumulated evidence from basic and clinical studies suggests that hypertension is a crucial risk factor for HFpEF (Fig. 3 ). These data may contribute to future studies aimed at elucidating the more detailed pathophysiology of HFpEF in hypertension research and the development of therapeutic agents and/or strategies that improve the prognosis of HFpEF in hypertension.

A scheme of the relationship between hypertension and HFpEF. The dysregulation of the central autonomic network is associated with enhanced sympathetic nervous system activity in hypertension linked to HFpEF via left atrial remodeling, left ventricular hypertrophy and increased arterial stiffness. HFpEF heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, LA left atrium, PV pulmonary vein

Keywords : heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, arterial stiffness, leftventricular hypertrophy, diastolic left ventricular dysfunction, left atrial remodeling.

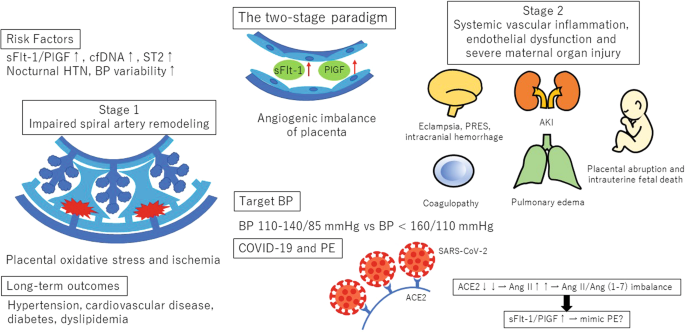

Up-to-date preeclampsia knowledge; what we should know for mother and child (See Supplementary Information 4 )

Diagnostic criterion.

In 2017, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association hypertension treatment guidelines identified hypertension as blood pressure (BP) ≥ 130/80 mmHg. The reference BP for hypertension during pregnancy as specified in international guidelines [e.g., the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy guidelines (ISSHP) [ 58 ] and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines (ACOG) [ 59 , 60 ]] is ≥140/90 mmHg. A large number of studies have examined the incidence of PE and fetal outcomes according to BP levels. The meta-analysis of these studies has shown that BP ≥ 120/80 mmHg, particularly ≥130/80 mmHg, in early pregnancy is also associated with increased maternal and perinatal risks and proposed new BP categories of <120/80 mmHg (normal), 120–129/<80 mmHg (high normal), and 130–139/80–89 mmHg (elevated) for pregnant women [ 61 ].

Prognostic tools

The predictive value of BP and other clinical characteristics for PE is relatively low [ 62 , 63 ]. Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1)/placental growth factor (PlGF) ratio testing resulted in reduced unnecessary hospitalization [ 64 , 65 ]. Circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and human suppression of tumorigenesis 2 (ST2) were increased in individual with gestational hypertension (GH) and PE and served as diagnostic biomarkers [Supplementary Information 4 - 1 ]. Nocturnal hypertension was a significant predictor of early-onset PE in high-risk pregnancies [ 66 ]. BP variability was higher in pregnant women with hypertensive disorders and was significantly associated with left ventricular mechanics [Supplementary Information 4 - 2 ]. Including these factors in multivariate models may improve the detection rates of PE and may identify women who could benefit from preventive interventions (Fig. 4 ).

Schematic presentation of the topics of preeclampsia 2021. HTN hypertension, PE preeclampsia, BP blood pressure, cfDNA cell-free DNA, ST2 human suppression of tumorigenesis 2, sFlt-1 soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1, PIGF placental growth factor, PRES posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, AKI acute kidney injury, ACE angiotensinogen converting enzyme, Ang angiotensin

The ISSHP recommends that BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg should be treated, with a goal BP of 110–140/85 mmHg, while the ACOG recommends antihypertensive medications when BP ≥ 160/110 mmHg, with goal BP below this threshold (Fig. 4 ). Systolic BP (sBP) < 130 mmHg within 14 weeks of gestation reduced the risk of developing early-onset superimposed PE in women with chronic hypertension [ 67 ]. The Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy (CHAP) project also showed that BP control to <140/90 was associated with a reduction in composite adverse outcomes, with no significant increase in small for gestational age infants [ 68 ].

Long-term outcomes

PE is linked to major chronic diseases such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease (Fig. 4 ). The American Heart Association lists hypertension during pregnancy as a major cardiovascular risk factor and recommends that affected women undergo cardiovascular risk screening within 3 months after giving birth [ 69 ]. Since many cardiovascular risk factors are modifiable and related to lifestyle, all women with prior PE should be followed up by physicians even after the resolution of PE.

COVID-19 and Pregnancy

Pregnancy could potentially affect the susceptibility to and severity of COVID-19. Severe cases of COVID-19 present with PE-like symptoms. PE mimicry by COVID-19 was confirmed following the alleviation of preeclamptic symptoms without delivery of the placenta [ 70 ]. In COVID-19, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE 2) function decreases, and subsequently, angiotensin II (Ang) activity increases [ 71 ]. Similar to PE, COVID-19 results in an increase in the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio due to pathologic Ang II/Ang (1-7) imbalance [ 72 ] (Fig. 4 ). Most experts believe that SARS-CoV-2 is likely to become endemic, and continued collection of data on the effects of COVID-19 during pregnancy is needed.

Further investigation is needed to decrease PE-related maternal and fetal deaths and to reduce maternal risks for chronic diseases in later life. The participation of physicians is necessary to offer appropriate medical care to women with prior PE, and continued publications of issues regarding PE in Hypertension Research are expected.

(KB and AI)

Keywords : preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1, placental growth factor.

Appropriate blood pressure assessment methods for the prevention of hypertension complications (See Supplementary Information 5 )

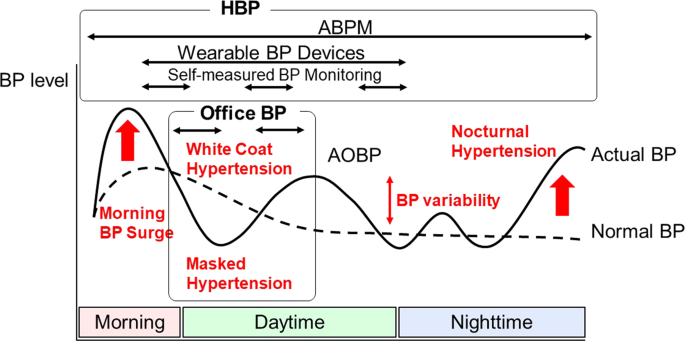

Blood pressure (BP) values can vary and fluctuate widely depending on the method and the environment of blood measurement. Via appropriate measurement and interpretation of BP values, hypertension can be correctly diagnosed, treated and guided [ 73 ]. To give an example, appropriate body posture is important for accurate BP measurement. Wan et al. [Supplementary Information 5 - 1 ] demonstrated that BP levels measured with the back in an unsupported position were 2.3/1.0 mmHg higher than those measured with the back in a supported position. Glenning et al. [Supplementary Information 5 - 2 ] demonstrated the feasibility of measuring diastolic blood pressure by the onset of the fourth Korotkoff phase (K4), when K5 is undetectable under exercise conditions in children and adolescents. In recent years, a variety of BP measurement devices and techniques have appeared, and accumulating evidence has shown the feasibility, reproducibility, and usefulness of these devices [ 74 , 75 ]. Kario et al. [ 76 ] demonstrated the relationship between BP by a newly released wrist-cuff oscillometric wearable BP device and left ventricular hypertrophy. They concluded the feasibility and usefulness of wearable BP devices to detect masked daytime hypertension. Automated office blood pressure (AOBP) measurement includes recording of several BP readings using a fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer with the patient resting alone in a quiet place, thereby potentially minimizing the white-coat effect. The most comprehensive meta-analysis [ 77 ] reported that AOBP is equivalent to home BP (HBP), but the diagnostic value and viability of AOBP are still controversial. Lee et al. [ 78 ] assessed the diagnostic accuracies of two AOBP machines and manual office blood pressure measurements (MOBP) in Chinese individuals and clarified the lower diagnostic significance of AOBP than that of MOBP. Recent studies strongly recommended the wide use of self-measured HBP [ 79 ] because HBP has better reproducibility than office BP (OBP), improves adherence to treatment, enables us to detect high-risk populations and has prognostic value for cardiovascular disease (CVD) events [ 80 , 81 , 82 ]. Both elevated morning and nocturnal BP values and disrupted circadian BP rhythm assessed by each BP measurement method or devices are associated with worsened cardiovascular outcomes (Fig. 5 ). Zhan et al. [ 83 ] demonstrated that HBP monitoring improved treatment adherence and BP control in stage 2 and 3 hypertension. Hoshide et al. [ 84 ] demonstrated the association of nighttime BP assessed by HBP and CVD events, independent of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels, in the Japanese clinical population. Narita et al. [Supplementary Information 5 - 3 ] demonstrated that the elevated difference between morning and evening systolic BP was associated with a higher incidence of CVD events in the J-HOP study. Narita et al. [Supplementary Information 5 - 4 ] also demonstrated that treatment-resistant hypertension diagnosed by HBP monitoring was associated with increased CVD risk independent of cardiovascular damage in the same Japanese cohort. Oliveira et al. [Supplementary Information 5 - 5 ] demonstrated that the SAGE score calculated by systolic BP, age, fasting blood glucose and estimated glomerular filtration rate was associated with pulse wave velocity measured by oscillometric devices and concluded that a SAGE score ≥8 could be used to identify a high risk of CVD events. ABPM is currently regarded as the reference method for hypertension diagnosis in children and pregnancy. Salazar et al. [Supplementary Information 5 - 6 ] demonstrated nocturnal hypertension assessed by ABPM as a significant predictor of early-onset preeclampsia/eclampsia in high-risk pregnant women in a cohort study in Argentina. ABPM also helped us to notice abnormal circadian patterns in BP, which are associated with increased circulating volume, largely determined by salt sensitivity and salt intake. Understanding these pathogenic mechanisms under conditions of nocturnal hypertension and heart failure suggests several new antihypertensive pharmacotherapies, including sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists [ 56 , 85 , 86 ]. Kario et al. [Supplementary Information 5 - 7 ] demonstrated the effect of esaxerenone, a highly selective mineralocorticoid receptor blocker, for improving nocturnal hypertension and NT-proBNP levels. Esaxerenon could be an effective treatment option, especially for nocturnal hypertensive patients with a riser pattern.

Methods of measuring variable blood pressure and evaluating factors associated with the prognosis of cardiovascular disease

Keywords : hypertension management, BP measurement devices, BP variability, home BP, cardiovascular disease

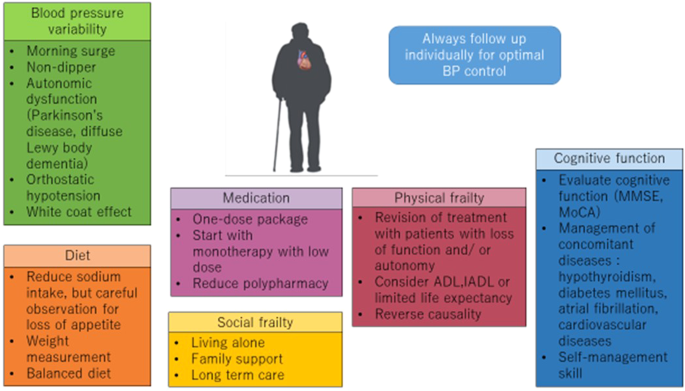

Considering frailty and exercise in the management of hypertension and hypertensive organ damage (See Supplementary Information 6 )

Frailty is defined as physiological decline and a state of vulnerability to stress and results in adverse health outcomes [ 87 ]. Frailty consists of multiple domains, such as physical, social, and psychological factors. Cognitive decline is one of the factors related to frailty, and blood pressure (BP) control significantly reduced dementia or cognitive decline in a meta-analysis [ 88 ]. However, in the elderly population above 80 years, the positive effect of antihypertensive therapy for preventing dementia was not proven [ 89 , 90 , 91 ].

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) among hypertensive patients was conducted by Quin et al. The prevalence of MCI was 30% in a sample of 47,179 hypertensive patients. Heterogeneity was seen due to ethnicity, study design (cross-sectional or cohort study), and cognition assessment tools [ 92 ]. Li. et al. investigated the association between carotid intima thickness (CIMT) and cognitive function in hypertensive patients [Supplementary Information 6 - 1 ]. CIMT was significantly and negatively associated with MMSE scores in people aged ≥60 years but not in those aged <60 years.

BP guidelines in various countries suggest that BP management should be carried out in the context of frailty or end of life, and careful observation, including personalized BP control among elderly individuals, is essential (Fig. 6 ). A total of 535 patients with hypertension (age 78 [ 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 ] years, 51% men, 37% with frailty) were prospectively followed for 41 months, and mortality associated with frailty and BP was evaluated by Inoue et al. [ 93 ]. Frailty was assessed by the Kihon checklist. Among 49 patients who died, mortality rates were lowest in those with systolic BP < 140 mmHg and nonfrailty and highest in those with systolic BP < 140 mmHg and frailty. The results indicate that frail patients have a higher risk of all-cause mortality than nonfrail patients, and BP should be managed considering frailty status, which is in line with previous reports [ 94 ]. Our latest study showed that in patients with preserved MMSE scores, higher BP was associated with cognitive impairment, and those with MMSE scores below 24 points had the opposite results [ 95 ]. Elderly individuals with hearing impairment have higher rates of hospitalization, mortality, falls, frailty, dementia, and depression. Miyata et al. performed a study using data from medical records from health checkups: higher SBP levels were associated with an increased risk of objective hearing impairment at 1 kHz [Supplementary Information 6 - 2 ].

Hypertension management in frail patients. ADL activities of daily living, IADL instrumental activities of daily living

In the era of technical advancement, people are spending less time being active, which leads to cardiovascular risks, including hypertension. However, guidelines emphasize the importance of nonpharmacological strategies such as lifestyle modification and exercise to prevent diseases [ 96 ].

Sardeli et al. compared types of exercise that are beneficial to health. The study compared the effects of aerobic training (AT), resistance training (RT), and combined training (CT) in hypertensive older adults aged >50 years. There were extensive health benefits associated with exercise training, and CT was the most effective intervention at improving a wide spectrum of health conditions, including cardiorespiratory fitness, muscle strength BMI, fat mass, glucose, TC and TGs [ 97 ]. J Almeida et al. showed that isometric handgrip exercise training reduced systolic BP in treated hypertensive patients [Supplementary Information 6 - 3 ]. Stair climbing and vascular function were assessed by Yamaji et al. There was a significant difference in nitroglycerine-induced vasodilatation between the group with no habits of climbing stairs and the other groups with two or more climbing habits [Supplementary Information 6 - 4 ].

The safety of resistance training was studied by Hansford et al who concluded that isometric resistance training (IRT) was safe and led to a potentially clinically meaningful reduction in BP [Supplementary Information 6 - 5 ].

Keywords : physical and social frailty, elderly, cognitive function, resistance training, cardiorespiratory function

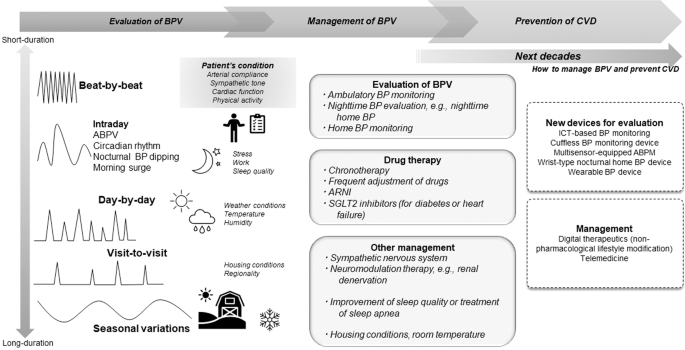

Blood pressure variability—therapeutic target for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (See Supplementary Information 7 )

In the past three decades, there have been many reports on the associations of various parameters of blood pressure (BP) variability with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events; these parameters include short-term BP variability (BPV), i.e., beat-by-beat BPV and ambulatory BPV, abnormality of nocturnal BP dipping pattern, and mid- to long-term BPV, i.e., day-by-day BPV, visit-to-visit BPV, and seasonal variations in BP [ 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 ]. In addition, BPV has been associated with the progression of endovascular organ damage related to heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and cognitive function [ 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 ] [Supplementary Information 7 - 1 ]. Several factors that are associated with abnormal BPV [ 112 ], as well as environmental factors such as cold or warm temperatures and seasonal changes in climate, increase fluctuations in BP. Individual intrinsic factors, such as sympathetic nervous tone, arterial stiffness, physical activity, and mental stress, also contribute to elevated BPV. According to evaluations of BPV abnormalities, out-of-office BP measurements, such as ambulatory and home BP monitoring, are needed. To evaluate nighttime BP levels, home BP monitoring devices equipped with a function for nighttime BP readings and new wrist-type nocturnal BP monitoring devices are available [ 76 ]. Although there are issues regarding measurement accuracy, cuffless BP monitoring devices, for example, those using pulse transit time, may be used to estimate nighttime BP levels [Supplementary Information 7 - 2 ]. Such cuffless BP devices can also evaluate beat-by-beat BPV. Moreover, by using the multisensor-equipped ambulatory BP monitoring device developed by our research group, it is possible to evaluate BPV associated with changes in temperature, physical activity, and/or atmospheric pressure [ 113 ].

Based on the mechanism(s) underlying a given patient’s BPV abnormality, several methods may be considered for the management of that abnormality (Fig. 7 ). For example, improving excessive sympathetic nervous system activation may be useful in the management of BPV abnormalities [ 114 ], and renal denervation has been reported to decrease ambulatory BPV [ 115 ]. Abnormal nocturnal BP dips may be treated by decreasing nighttime BP. In patients with sleep apnea, improving sleep quality and implementing continuous positive airway pressure are recognized to be useful for nighttime BP control [ 116 ]. Moreover, early adjustment of antihypertensive drugs has been reported to be useful in suppressing seasonal variations in BP, leading to a decreased risk of CVD events [ 99 ]. Furthermore, housing conditions and room temperature are closely related to BP levels, and adaptive control of room temperature would be useful to suppress winter increases in BP [ 117 , 118 ]. In clinical practice, we must not forget that BPV parameters are interrelated. For instance, frequent evaluation of BP levels and adjustment of antihypertensive drugs can suppress visit-to-visit BPV, which in turn leads to the suppression of seasonal variations in BP.

Current and future perspectives in the management of blood pressure variability. Short- and long-term BP variability is associated with CVD event risk independent of each BP level. Out-of-office BP measurements, such as ABPM and home BP monitoring, and other new BP devices are useful for evaluating the various types of BP variability. To suppress BP variability, several management methods, including new antihypertensive medications, chronotherapy, housing condition, and sympathetic nervous denervation, are considered. ABPM ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, ABPV ambulatory blood pressure variability, ARNI angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, BP blood pressure, BPV blood pressure variability, CVD cardiovascular disease, ICT information and communication technology, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor

Over the next decade, more data on how to manage and control BPV need to be accumulated. Additionally, future studies should be conducted to verify whether the different types of BVP management are useful in preventing CVD events.

(KN, SH and KK)

Keywords : blood pressure variability, out-of-office blood pressure monitoring, cardiovascular disease prevention, wearable blood pressure monitoring device, environmental factors.

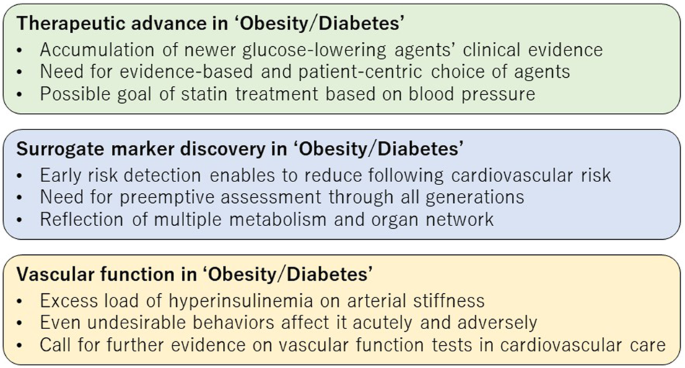

Optimal therapy and clinical management of obesity/diabetes (See Supplementary Information 8 )

Obesity/diabetes is a major comorbidity in patients with hypertension, and these conditions often share common pathological conditions, such as insulin resistance and the risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD). One of the biggest highlights of recent years in the area of obesity/diabetes has been the remarkable benefits of newer glucose-lowering agents seen in large-scale clinical trials on cardiorenal outcomes (Fig. 8 ), followed by the relevant clinical guideline updates and the expansion of the clinical application of those agents [ 119 ]. In particular, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists are now preferentially recommended in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and specific cardiorenal risk, independent of diabetes status or background use of metformin [ 120 ]. It is noteworthy, of course, that those agents reduced the risk of cardiorenal events, and their multifaceted effects beyond hypoglycemic effects are also attracting clinical attention. In a review series ‘New Horizons in the Treatment of Hypertension’ in Hypertension Research, Tanaka and Node [ 121 ] discussed the modest effects of those agents on blood pressure (BP)-reduction and the clinical perspectives. They also proposed a new-normal style care for diabetes and its complications using such evidence-based agents with multidisciplinary effects, partly aiming at reduced polypharmacy and avoidance of its possible harm. This action will improve the quality of hypertension care in patients with obesity/diabetes; however, a substantial population with treated hypertension still has inadequate blood pressure control, which is recognized as resistant hypertension (RH). Due to the difficulty in distinguishing true RH from pseudo-RH due to nonadherence, little is known about the clinical characteristics of true RH. Chiu et al. from Boston [Supplementary Information 8 - 1 ] reported a notable prevalence (26.6%) of true RH in patients with T2D registered in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) Blood Pressure trial and identified several independent predictors, such as higher baseline BP, higher number of baseline antihypertensives, macroalbuminuria, chronic kidney disease, and history of stroke. Moreover, patients with true RH exhibited poorer prognosis than those without, suggesting an emerging need for effective screening and intensified treatment for patients with true RH.

Schematic presentation of the topic ‘Obesity/Diabetes’ in 2021

The BP treatment goal in patients with diabetes and hypertension is less than 130/80 mmHg [ 122 ], and intensified BP control was associated with reduced stroke risk [ 123 , 124 , 125 ]. Intensive lipid-lowering therapy is also recommended for patients with T2D at risk of CVD [ 126 ]; however, an original EMPATHY study investigating the effect of intensive lipid-lowering therapy (target of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C] < 70 mg/dL) on cardiovascular outcomes failed to show the clinical benefits of intensive statin therapy in patients with T2D, diabetic retinopathy, elevated LDL-C levels, and no known CVD [ 127 ]. In a subanalysis of the EMPATHY study, Shinohara et al. [ 128 ] revealed for the first time that intensive statin therapy was associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular events compared with standard therapy (target of ≥100 to <120 mg/dL) in a subgroup with baseline BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg but not in another subgroup with baseline BP < 130/80 mmHg. Their findings suggest that baseline BP is also a possible determinant of the target LDL-C in that patient population, although the precise reasons for the difference in the clinical benefits of intensive statin therapy between subgroups according to baseline BP levels are still uncertain.

Obesity is a crucial global health concern across generations. Obesity and insulin resistance cause several cardiometabolic disorders, including hypertension, and increase the risk of subsequent CVD. Hence, further actions against obesity and cardiometabolic disorders are urgently needed for individuals of all generations [ 129 , 130 ]. In this context, Fernandes et al. from Brazil [Supplementary Information 8 - 2 ] revealed for the first time that Ang-(1-7) and des-Arg9BK metabolites were novel biological markers of adolescent obesity and relevant cardiovascular risk profiles, such as elevated BP, lipids, and inflammation. Thu et al. from Singapore [Supplementary Information 8 - 3 ] found a positive association between accumulated visceral adipose tissue and systolic BP in midlife-aged women, independent of burdens of inflammatory markers. Intriguingly, Haze et al. [ 131 ] clearly demonstrated that an increased ratio of visceral-to subcutaneous fat volume was an independent risk factor for renal dysfunction in Japanese patients with primary aldosteronism. These findings should highlight the clinical importance and the need for further research to explore surrogate markers of obesity in the care of hypertension and its related conditions (Fig. 8 ).

Finally, we briefly introduce some exciting progress in vascular function in the area of “Obesity/Diabetes” (Fig. 8 ). Murai et al. [ 132 ] elegantly showed that postload hyperinsulinemia was independently associated with increased arterial stiffness as assessed by brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (PWV) in young medical students at Jichi Medical University. Given the close pathological relationship between hyperinsulinemia and most CVDs, including heart failure [ 133 , 134 ], their findings suggest that hyperinsulinemia-induced vascular failure is one of the key drivers of that pathological link. Interestingly, Fryer et al. from the UK [Supplementary Information 8 - 4 ] also found that arterial stiffness as assessed by carotid-femoral PWV was exacerbated by the consumption of a high-fat meal relative to a low-fat meal prior to 180 min of uninterrupted sitting. Importantly, arterial stiffness testing could accurately reflect even such a combination of unfavorable behaviors, and thus vascular function assessment has the potential to reflect a wide spectrum of cardiovascular risk and provide a clinical opportunity for better risk stratification and optimal modification [ 135 ]. We look forward to accumulating and consolidating evidence of vascular function tests and further applying them to actual cardiovascular care [ 136 ].

(AT and KN)

Keywords : glucose-lowering agent, resistant hypertension, statin, surrogate marker, vascular function

A new era of progress in primary aldosteronism treatment: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, a new aldosterone assay, and a clinical practice guideline (See Supplementary Information 9 )

A hot topic in 2021 was advances in the treatment of mineralocorticoid receptor (MR)-associated hypertension [ 137 ], particularly primary aldosteronism (PA). The nonsteroidal MR antagonist (MRA) esaxerenone is now widely used in Japan. Kario et al. [ 138 ] reported that esaxerenone reduced nocturnal blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension, according to ambulatory blood pressure assessment and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide assays. Yoshida et al. [ 139 ] reported that MRAs such as esaxerenone improved quality of life in PA patients. Ito et al. [ 140 ] reported that add-on treatment using esaxerenone with maximal tolerable doses of a renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitor reduced the urinary albumin-creatinine ratio in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (ESAX-DN), suggesting a renoprotective effect against diabetic nephropathy. Several clinical studies of another nonsteroidal MRA, finerenone (FIDELIO-DKD [ 141 ], FIGARO-DKD [ 142 ], and FIDELITY [ 143 ]), have shown its renoprotective effect against diabetic nephropathy as well as cardiovascular events, particularly hospitalization for heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Although there are no reports of clinical studies on finerenone for PA, finerenone may be used in the future for type 2 diabetes patients with PA, as obesity, glucose intolerance, and sleep apnea are common complications in patients with PA [ 144 ]. Similarly, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) have been demonstrated to improve the prognosis of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in individuals with type 2 diabetes (EMPA-REG OUTCOME [ 145 ], DECLARE–TIMI 58 [ 146 ], DAPA-HF[ 147 ], and DAPA-CKD [ 22 ]). As steroidal MRAs such as spironolactone and eplerenone are effective in the treatment of mild to severe stages of heart failure (RALES, EPHESUS [ 148 ], and EPHESUS-HF [ 149 ]), combined treatment with MRA and SGLT2i, in addition to an RAS inhibitor, may be a novel effective treatment for cardiac and renal protection in type 2 diabetic patients (Fig. 9 ). Second, radiofrequency ablation of macroscopic adrenal tumors [ 150 , 151 , 152 ] has been reported as an alternative treatment for PA to lower blood pressure and plasma aldosterone levels. This treatment has been covered by health insurance providers in Japan since April 2022, but long-term outcomes need to be validated.

Potential drug therapy regimen. Combined administration of an MRA and an SGLT2i may afford cardiac and renal protection. MRA mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor

Another hot topic was the launch of serum aldosterone measurement using a chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (CLEIA), which utilizes a two-step sandwich method. Previously, low aldosterone levels may have been measured incorrectly [ 153 ]. The new CLEIA figures are closely correlated with liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry values; the new assay is more accurate than the previous radioimmunoassay, which overestimated serum aldosterone levels [ 154 , 155 , 156 ]. Thus, the Japan Endocrine Society issued a Primary Aldosteronism Clinical Guideline in 2021 [ 157 ]. The CLEIA method is also used to measure urinary aldosterone levels; Ozeki et al. [ 158 ] proposed a PA diagnostic cutoff of ≥3 μg/day for the oral salt loading test. The CLEIA method is currently available only in Japan.

Exosomes may serve as biomarkers of MR activity. Ochiai-Homma et al. [ 159 ] focused on pendrin, a Cl – /HCO3 – exchanger that is only expressed by renal intercalated cells. In a rat model, the pendrin level in the urinary exosome was reduced by therapeutic interventions favored for PA patients; the urinary level was correlated with the renal level. This model may help to elucidate the pathophysiology of PA-induced organ injury [ 160 ].

Finally, Haze et al. [Supplementary Information 9 - 1 ], Segawa et al. [Supplementary Information 9 - 2 ], Nishimoto et al. [Supplementary Information 9 - 3 ], Chen et al. [Supplementary Information 9 - 4 ], and Liu et al. [Supplementary Information 9 - 5 ] have conducted intriguing clinical studies regarding PA.

(YY and HS)

Keywords : mineralocorticoid receptor-associated hypertension, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, hypertension, primary aldosteronism, chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay

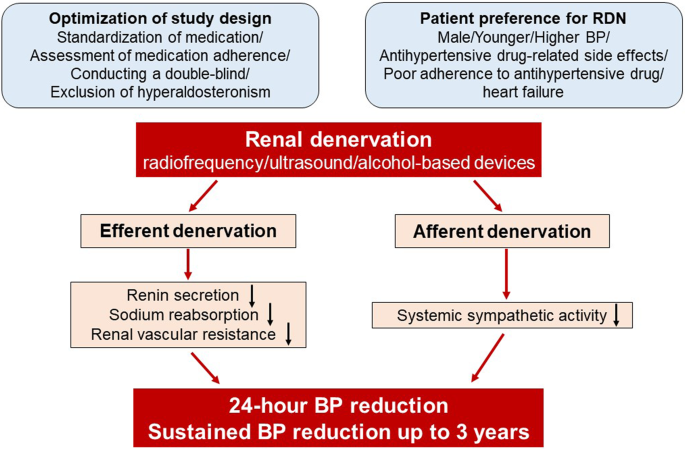

Advances in renal denervation for treating hypertension: current evidence and future perspectives (See Supplementary Information 10 )

It is well established that renal denervation (RDN) decreases blood pressure (BP) in various models of hypertension in animals and in humans [ 161 , 162 , 163 , 164 , 165 ]. Here, we reviewed studies related to RDN published in Hypertension Research in 2021 (Fig. 10 ). The antihypertensive effect of RDN is mediated by interrupting both the efferent outputs from the brain to the kidney and the afferent inputs from the kidney to the brain, suppressing systemic sympathetic outflow [ 165 , 166 ]. In basic research, there are two methods of RDN: total RDN (TRDN) performed by surgical cutting of renal nerves to ablate both efferent and afferent nerves and selective afferent RDN (ARDN) performed via capsaicin application to renal nerves to specifically ablate afferent nerves expressing capsaicin receptors [ 167 , 168 ]. Katsurada et al. [ 169 ] reviewed previous reports that address the different effects of TRDN and ARDN in different animal models of hypertension, suggesting potentially complicated and diversified origins of hypertension. The potential therapeutic effects of TRDN and ARDN have also been reported in animal models of heart failure [ 170 ].

Topics on renal denervation. BP blood pressure, RDN renal denervation

In clinical practice, radiofrequency, ultrasound, and alcohol-based RDN devices have been developed as second-generation catheter devices and evaluated in randomized control trials. Ogoyama et al. [ 171 ] reported a meta-analysis of nine randomized sham-controlled trials of RDN that showed that RDN significantly reduced a range of office, home and 24 h BP parameters in patients with resistant, uncontrolled, and drug-naïve hypertension. There were no significant differences in the magnitude of BP reduction between radiofrequency-based and ultrasound-based devices.

The Global SYMPLICITY Registry (GSR) is a prospective all-comer registry to evaluate the safety and efficacy of RDN in a real-world population [ 172 ]. The overall GSR has enrolled over 2700 patients, and more than 2300 of these have now been followed for 3 years [ 173 ]. GSR Korea is a Korean registry substudy of GSR ( N = 102) [ 174 ]. Kim et al. [Supplementary Information 10 - 1 ] reported the 3-year follow-up outcomes from the GSR Korea showing that RDN led to sustained reductions in office systolic BP at 12, 24 and 36 months (−26.7 ± 18.5, −30.1 ± 21.6, and −32.5 ± 18.8 mmHg, respectively) without safety concerns. Recently, the efficacy and safety of second-generation radiofrequency RDN up to 36 months have been reported [ 175 ].

The REQUIRE trial by Kario et al. [Supplementary Information 10 - 2 ] is the first trial of ultrasound RDN in Asian patients from Japan and South Korea with hypertension receiving antihypertensive therapy. The study findings were neutral for the primary endpoint, with similar reductions in 24 h systolic BP at 3 months in the RDN (−6.6 mmHg) and sham control groups (−6.5 mmHg). Although BP reduction after RDN was similar to other sham-controlled studies [ 161 , 162 , 164 , 176 ], the sham group in this study showed much greater reduction. Unlike RADIANCE-HTN TRIO that used an ultrasound catheter system to measure its primary endpoint, REQUIRE did not standardize medications or measure medication adherence, which may lead to increased variability in BP outcome; moreover, REQUIRE was not a double-blind study, which may result in a substantial bias. Another important factor is that 32.4% of patients showed hyperaldosteronism in the REQUIRE trial. Patients with primary aldosteronism have decreased sympathetic nerve activity and are likely to respond poorly to RDN [ 177 ]. The lessons from REQUIRE will enable us to design a follow-up trial to make a definitive evaluation of the effectiveness of RDN in Asian patients with hypertension.

Another topic is the patient preference for RDN. Kario et al. [Supplementary Information 10 - 3 ] conducted a nationwide web-based survey in Japan and reported that preference for RDN was expressed by 755 of 2392 Japanese patients (31.6%) and was higher in males, in younger patients, in those with higher BP, in patients who were less adherent to antihypertensive drug therapy, in those who had antihypertensive drug-related side effects, and in those with comorbid heart failure. This should be taken into account when making shared decisions about antihypertensive therapy.

Keywords : renal nerves, hypertension, renal denervation, patient preference, heart failure

Hot topics in uric acid research: the difficulties of managing hyperuricemia (See Supplementary Information 11 )

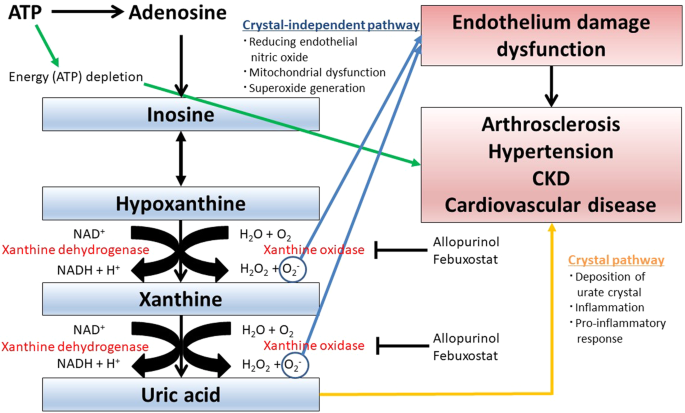

The mechanisms linking hyperuricemia, arteriosclerosis, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease are becoming clearer (Fig. 11 ) [ 178 , 179 , 180 , 181 ]. However, it remains unclear whether treatment of hyperuricemia improves these diseases. Some recent topics of uric acid research are introduced below.

Mechanisms linking hyperuricemia and arteriosclerosis, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease. ATP adenosine triphosphate, CKD chronic kidney disease

First, urate-lowering treatment with allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase (XO) inhibitor, did not slow the decline in eGFR compared with placebo in either the PERL (Preventing Early Renal Loss in Diabetes) trial [ 182 ] or CKD-FIX (Controlled Trial of Slowing of Kidney Disease Progression from the Inhibition of Xanthine Oxidase) [ 183 ]. These results were similar to the results of FEATHER (Febuxostat Versus Placebo Randomized Controlled Trial Regarding Reduced Renal Function in Patients with Hyperuricemia Complicated by Chronic Kidney Disease Stage 3) from Japan [ 184 ]. Moreover, the PRIZE (Program of Vascular Evaluation Under Uric Acid Control by the Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitor Febuxostat: Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled) study showed that febuxostat did not delay the progression of carotid atherosclerosis in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia [ 185 ]. These results suggest the difficulties of managing hyperuricemia for preventing chronic kidney disease (CKD) and/or arteriosclerosis.

Second, FAST (the Febuxostat versus Allopurinol Streamlined Trial) showed that febuxostat was noninferior to allopurinol therapy with respect to the primary cardiovascular endpoint, all-cause or cardiovascular deaths [ 186 ]. The results of FAST were different from the results of the CARES (The Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat and Allopurinol in Patients with Gout and Cardiovascular Morbidities) trial [ 187 ], and the authors summarized that regulatory advice to avoid the use of febuxostat in patients with cardiovascular disease should be reconsidered and modified [ 186 ].

In Hypertension Research 2021, several important articles on uric acid research were published. Mori et al. reported that a high serum uric acid level is associated with an increase in systolic blood pressure in women but not in men in subjects who underwent annual health checkups [ 188 ]. Their group also reported that a low uric acid level is a significant risk factor for CKD over 10 years in only women, and an elevated UA level increases the risk of CKD in both sexes [Supplementary Information 11 - 1 ]. Moreover, Li et al. reported that elevated serum uric acid levels in subjects without stroke, coronary heart disease, and medication for hyperuricemia or gout aged 40–79 years were independent predictors of total stroke, especially ischemic stroke, in women but not in men in a 10-year cohort study [Supplementary Information 11 - 2 ]. These results suggested the possibility that both hyperuricemia and hypouricemia in women could be associated with a higher risk for hypertension, CKD, and stroke than those in men.

Azegami et al. reported a prediction model of high blood pressure in young adults aged 12–13 years followed up for an average of 8.6 years. The results showed that uric acid was an important predictor of high blood pressure [ 189 ].

Kawasoe et al. reported that high (4.1–5.0, 5.1–6.0, and >/=6.1 mg/dL) and low (</=2.0 mg/dL) serum uric acid levels were significantly associated with an increased prevalence of high blood pressure compared to 2.1–4.0 mg/dL serum uric acid in subjects who underwent health checkups [ 190 ]. The results were compatible with a previous report stratified by sex [ 191 ]. Serum uric acid levels and the risks for diseases are largely different between men and women, and it is desirable to conduct every analysis by sex when conducting uric acid research.

Furuhashi et al. reported that plasma xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) activity was associated with hypertension in 271 nondiabetic subjects in the Tanno–Sobetsu Study [ 192 ]. Kusunose et al. reported that additional febuxostat treatment in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia for 24 months might have potential prevention effects on impaired diastolic dysfunction in the subanalysis of the PRIZE study [ 193 ]. These reports suggested the potential direct antioxidant effects of the treatment as reflected in serum uric acid levels as well as its xanthine-oxidase-lowering properties in tissue [Supplementary Information 11 - 3 ]. Whether the preferential use of xanthine oxidoreductase XO inhibitors becomes a new therapeutic strategy for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia awaits further high-quality trials [Supplementary Information 11 - 4 ].

Finally, Nishizawa et al. reported a mini review article focusing on the relationship between hyperuricemia and CKD or cardiovascular diseases, and they summarized that high-quality and detailed clinical and basic science studies of hyperuricemia and purine metabolism are needed [Supplementary Information 11 - 5 ].

(MK and TK)

Keywords : uric acid, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, arteriosclerosis, xanthine oxidase

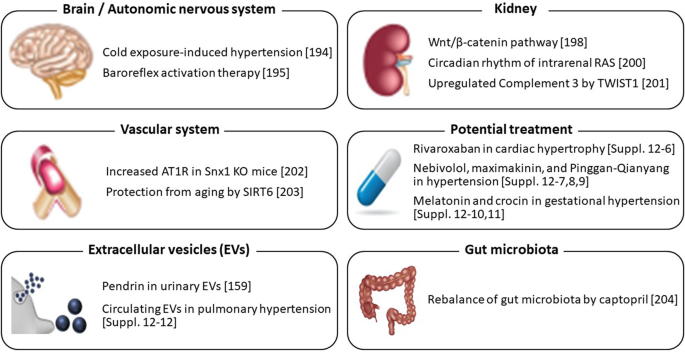

Basic research: elucidation of the “mosaic” pathogenesis of hypertension (See Supplementary Information 12 )

The pathogenesis of hypertension is multifactorial and highly complex, as described by the “mosaic theory” of hypertension. Basic research plays critical roles in elucidating the “mosaic” pathogenesis of hypertension and developing its treatment (Fig. 12 ).

Topics in basic research. Each ref. number indicates the reference paper cited in the text. AT1R angiotensin type 1 receptor, EV extracellular vesicles, KO knockout, RAS renin-angiotensin system, Snx1 soring nexin 1, SIRT6 sirtuin 6, TWIST1 twist-related protein 1

In the field of the brain and autonomic nervous system, Chen et al. demonstrated that mild cold exposure elicits autonomic dysregulation, such as increased sympathetic activity, decreased baroreflex sensitivity, and poor sleep quality, causing blood pressure (BP) elevation in normotensive rats [ 194 ]. This finding may have critical implications for cardiovascular event occurrence at low ambient temperatures. In addition, Domingos-Souza et al. showed that the ability of baroreflex activation to modulate hemodynamics and induce lasting vascular adaptation is critically dependent on the electrical parameters and duration of carotid sinus stimulation in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) [ 195 ], proposing a rationale for improving baroreflex activation therapy in humans. Although only normotensive and hypertensive rats were used in these two studies, without comparing the two strains, previous studies have shown that neuronal function and activity in the cardiovascular sympathoregulatory nuclei, including the nucleus tractus solitarius and rostral ventrolateral medulla, which are involved in baroreflex regulation, are different between normotensive and hypertensive rats [ 196 , 197 ]. Further studies comparing normotensive and various hypertensive animal models would be interesting.

In the kidney, Kasacka et al. showed that the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is increased in SHRs and two-kidney, one-clip (2K1C) hypertensive rats, while it is inhibited in deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt rats according to kidney immunohistochemistry [ 198 ]. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is also involved in BP regulation. In renal damage with an impaired glomerular filtration barrier, liver-derived angiotensinogen filtered through damaged glomeruli regulates intrarenal RAS activity [ 199 ]. Matsuyama et al. further showed that the glomerular filtration of liver-derived angiotensinogen depending on glomerular capillary pressure causes circadian rhythm of the intrarenal RAS with in vivo imaging using multiphoton microscopy [ 200 ]. Fukuda and his colleagues have shown that complement 3 (C3) is a primary factor that activates intrarenal RAS [Supplementary Information 12 - 1 , 2 ]. Otsuki and Fukuda et al. additionally demonstrated that TWIST1, a transcription factor that regulates mesodermal embryogenesis, transcriptionally upregulates C3 in glomerular mesangial cells from SHRs [ 201 ].

The RAS in the vascular system, as well as in other organ systems, plays a major role in BP regulation. Soring nexins (SNXs) are cellular sorting proteins that can regulate the expression and function of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [Supplementary Information 12 - 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Liu C et al. demonstrated that SNX1 knockout mice exhibit hypertension through vasoconstriction mediated by increased expression of AT1R, a GPCR mediating most of the effects of angiotensin II (Ang II), within the arteries [ 202 ]. Moreover, in vitro studies suggest that SNX1 sorts arterial AT1R for proteasomal degradation. These findings indicate that SNX1 impairment increases arterial AT1R expression, leading to vasoconstriction and hypertension. Liu X et al. found that sirtuin 6 (SIRT6) expression is downregulated in the aortae of aged rats and showed that SIRT6 knockdown enhances Ang II-induced vascular adventitial aging by activating the NF-κB pathway in vitro [ 203 ]. This study suggests that SIRT6 may be a biomarker of vascular aging and that activating SIRT6 can be a therapeutic strategy for delaying vascular aging.

Several reports indicate the potential treatment for hypertension and the associated organ damage. Narita et al. showed that rivaroxaban exerts a protective effect against cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting protease-activated receptor-2 signaling in renin-overexpressing hypertensive mice [Supplementary Information 12 - 6 ]. In addition, the efficacy of nebivolol (a third-generation β-blocker), maximakinin (a bradykinin agonist peptide extracted from the skin venom of toad), and Pinggan-Qianyang decoction (a traditional Chinese medicine) were also shown in hypertensive animal models [Supplementary Information 12 - 7 , 8 , 9 ]. In animal models of gestational hypertension, melatonin and crocin have each exhibited an antihypertensive effect [Supplementary Information 12 - 10 , 11 ].

Studies investigating extracellular vesicles (EVs) have increased. Ochiai-Homma et al. showed that pendrin in urinary EVs can be a useful biomarker for the diagnosis and treatment of primary aldosteronism, which was supported by studies using a rat model of aldosterone excess [ 159 ]. Another report indicated that pulmonary arterial hypertension induces the release of circulating EVs with oxidative content and alters redox and mitochondrial homeostasis in the brains of rats [Supplementary Information 12 - 12 ]. Studies on the role of gut microbiota in BP regulation have also been accumulating. Wu et al. demonstrated that captopril has the potential to rebalance the dysbiotic gut microbiota of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats, suggesting that the alteration of the gut flora by captopril may contribute to the hypotensive effect of this drug [ 204 ]. Moreover, important basic studies, including review papers, have been reported in Hypertension Research. See Supplementary Information.