- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Asthma & Allergies

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Breast Cancer

- Cardiovascular Health

- Environment & Sustainability

- Exercise & Fitness

- Headache & Migraine

- Health Equity

- HIV & AIDS

- Human Biology

- Men's Health

- Mental Health

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Parkinson's Disease

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Sexual Health

- Ulcerative Colitis

- Women's Health

- Nutrition & Fitness

- Vitamins & Supplements

- At-Home Testing

- Men’s Health

- Women’s Health

- Latest News

- Medical Myths

- Honest Nutrition

- Through My Eyes

- New Normal Health

- 2023 in medicine

- Why exercise is key to living a long and healthy life

- What do we know about the gut microbiome in IBD?

- My podcast changed me

- Can 'biological race' explain disparities in health?

- Why Parkinson's research is zooming in on the gut

- Health Hubs

- Find a Doctor

- BMI Calculators and Charts

- Blood Pressure Chart: Ranges and Guide

- Breast Cancer: Self-Examination Guide

- Sleep Calculator

- RA Myths vs Facts

- Type 2 Diabetes: Managing Blood Sugar

- Ankylosing Spondylitis Pain: Fact or Fiction

- Our Editorial Process

- Content Integrity

- Conscious Language

- Health Conditions

- Health Products

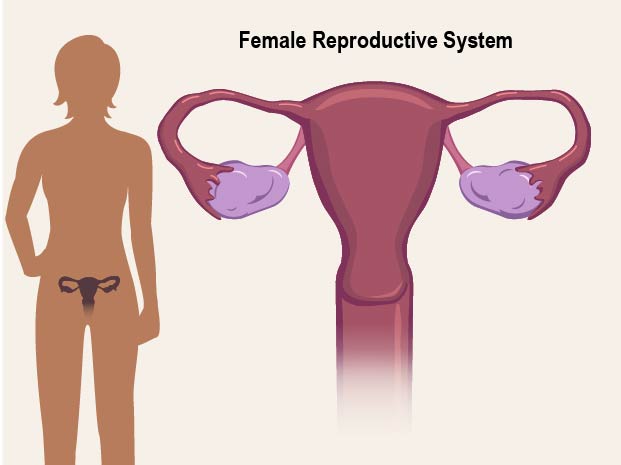

A guide to female anatomy

Female anatomy includes the external genitals, or the vulva, and the internal reproductive organs, which include the ovaries and the uterus.

One major difference between males and females is their reproductive organs. Anatomy specific to females generally relates to sexual function, reproduction, and hormone control.

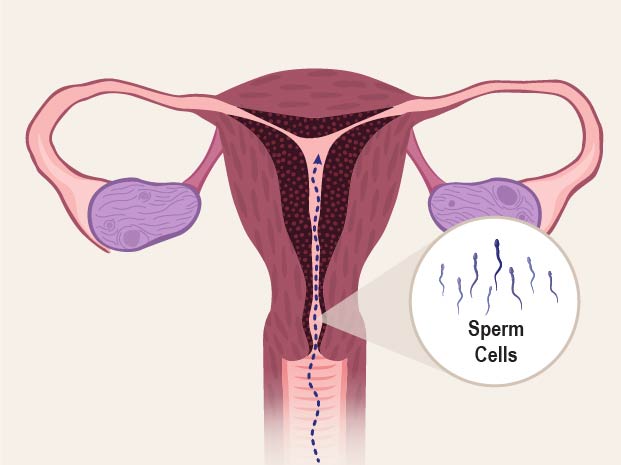

Males and females have physically different sexual anatomy, but all sex organs come from the same bundle of cells during fetal development. A baby’s biological sex is determined at the moment the father’s sperm meets the mother’s egg.

This article will look in detail at the structure and function of the female internal and external organs.

Below is a 3D model of female anatomy, which is fully interactive . Explore the model using your mouse pad or touchscreen to understand more about female anatomy .

External anatomy

The external female anatomy includes the pubis and the vulva. The following sections discuss these in more detail.

The mons pubis, or public mound, is the fleshy area on the pelvic bone where females typically grow pubic hair.

The vulva refers to the external parts of a female’s genitals. It consists of several parts, including the labia majora, the labia minora, and the glans clitoris.

The list below provides more detail on these parts:

- Labia majora. These are the fleshy outer lips on either side of the vaginal opening. The word “labia” is Latin for “lips.” These outer lips usually grow pubic hair.

- Labia minora. These are the inner lips. They sit inside the outer lips but can be varying sizes. In some females, for example, the inner lips extend beyond the outer lips.

- Clitoris. The glans clitoris sits at the top of the vulva, located where the inner lips meet. It is usually around the size of a pea, though size varies from person to person. Only the tip of the clitoris is visible, but it has two shafts that extend into the body by as much as 5 inches. The clitoris contains many nerve endings that are very sensitive, especially during sexual stimulation.

- Clitoral hood. The clitoral hood is the fold of skin that surrounds the head of the clitoris. It protects the clitoris from friction.

- Urethral opening. The opening to the urethra sits above the vaginal opening. The urethra connects to the bladder, and the opening is where urine exits the body.

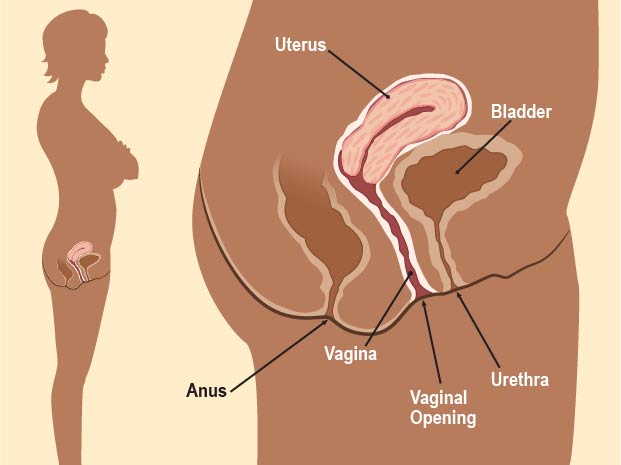

Internal anatomy

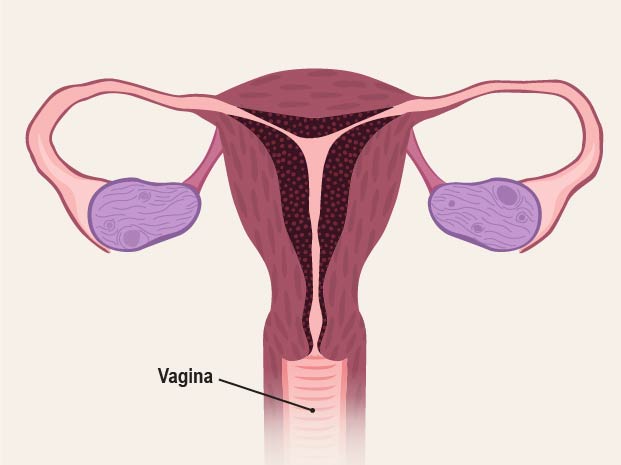

The internal female anatomy begins at the vagina, which is the canal that leads from the vulva to the uterus.

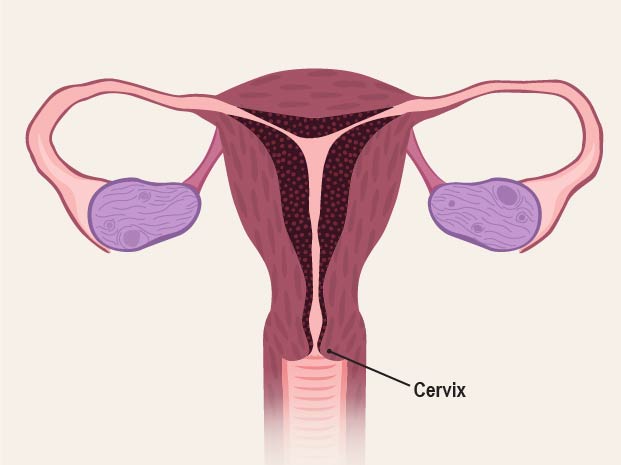

The cervix separates the vagina from the uterus, and the fallopian tubes connect the ovaries with the uterus.

The following sections discuss these organs in more detail.

As mentioned above, the vagina is the canal that connects the vulva with the uterus. The opening to the vagina is part of the vulva.

The vagina can vary in size, but the average length is about 2.5 to 3 inches . That said, it expands in length during arousal.

It also contains special structures called Bartholin’s glands. These are two “ pea-sized ” glands that sit on either side of the vaginal opening. These glands are responsible for secreting lubrication to keep the vaginal tissues from becoming too dry.

The cervix is the lower portion of the uterus. It is a cylinder-shaped area of tissue that separates the vagina from the rest of the uterus.

During birth, the cervix dilates to allow the baby to move through the vagina.

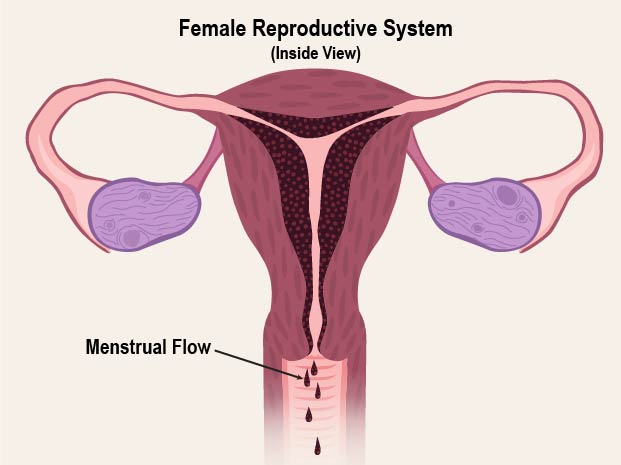

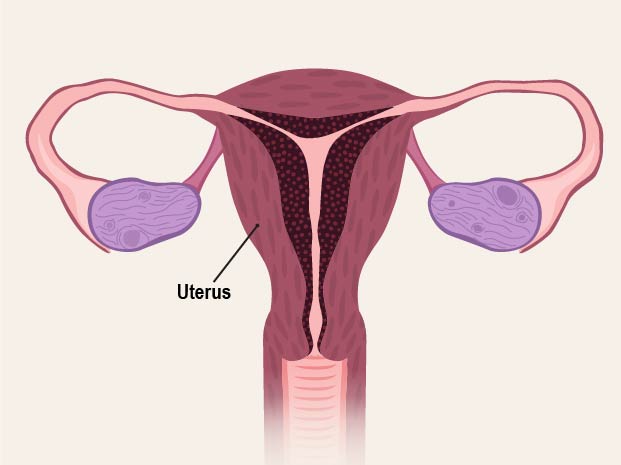

The uterus is located in the middle of the pelvic cavity. This muscular sac will house the fetus during pregnancy.

During a female’s monthly menstrual cycle, the lining of the uterus thickens with blood in preparation for the release of an egg from one of the ovaries. This is to prepare a nourishing environment for a fetus if pregnancy occurs.

If pregnancy does not occur, the uterine lining sheds. This is called the menstrual period. It occurs every around 28 days, though cycle length varies between females.

The upper portion of the uterus is connected to the ovaries by the fallopian tubes.

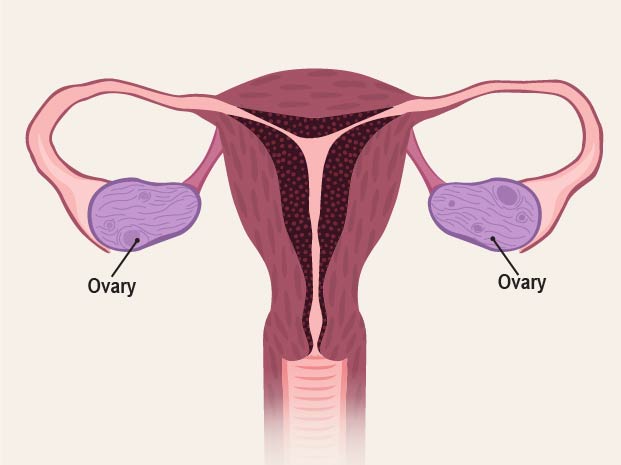

The ovaries are egg-shaped organs attached to fallopian tubes on the left and right sides of the body. Each ovary is roughly the size of an almond. Most females are born with two ovaries that produce eggs.

In addition to producing eggs, the ovaries also produce hormones. Namely, they release estrogen and progesterone .

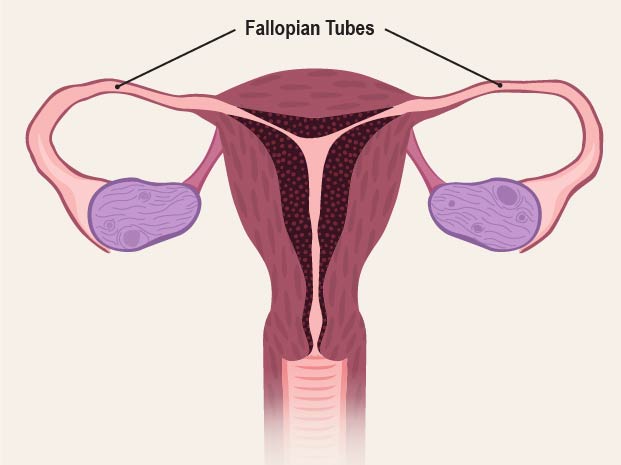

Fallopian tubes

The fallopian tubes connect the ovaries to the uterus. When the ovaries release an egg, the egg travels down the fallopian tube toward the uterus for potential fertilization.

If a fertilized egg implants in the fallopian tube, doctors call this an ectopic pregnancy . An ectopic pregnancy is a medical emergency because the fallopian tube can rupture.

The hymen is a membrane of tissue that covers the external vaginal opening. Not all females have a hymen, however.

The hymen can rupture as a result of pelvic injury, sports activity, pelvic examination, sexual intercourse, or childbirth. The absence of a hymen does not mean that a female has been sexually active.

Many people consider breasts “accessory organs” to the female reproductive system, as they are responsible for supplying milk to an infant after childbirth.

The major external components of the breasts include the:

- Nipple. The nipple is the rounded area where milk drains to feed a baby. They have many nerve endings that can make them an area of sexual stimulation. Nipples do not always protrude. Some females have flat or inverted nipples .

- Areola. The areola is the pigmented area that surrounds the nipple. It is circular and varies in size from person to person. It contains small glands, called Montgomery glands, that secrete lubrication to keep the nipple from drying out, especially when nursing.

- Breast tissue. The breast is the area of skin on the chest that is composed of fat, muscle, and ligament tissue, as well as an intricate network of blood vessels and glands. These areas are specialized for breastfeeding. Breast tissue size varies greatly from person to person, often due to a combination of individual genetics and body mass.

Internally, the breasts are primarily composed of fat. The amount of fat can determine breast size. However, breast size has no bearing on the amount of milk someone is able to produce.

The internal anatomy of the breasts include the:

- Alveoli. These are milk secreting cells grouped into clusters inside the breasts.

- Lactiferous ducts. These are special channels that open on the nipple’s surface. Breast milk exits through these ducts to nourish a baby.

- Lobules. These are collections of alveoli in the breast that secrete milk. The lobules drain into lactiferous ducts, then into lactiferous sinuses that promote milk flow from the nipple.

- Mammary glands. These are responsible for producing breast milk.

The female body contains many organs that work together to achieve a variety of functions.

The shape and size of many of these organs naturally vary from person to person. However, if a female is concerned that any part of their anatomy might not be “normal,” they can talk to their doctor.

Last medically reviewed on November 5, 2019

- Biology / Biochemistry

- Pregnancy / Obstetrics

- Sexual Health / STDs

- Women's Health / Gynecology

How we reviewed this article:

- Chapter 27: The reproductive system. Anatomy and physiology of the female reproductive system. (n.d.). https://opentextbc.ca/anatomyandphysiology/chapter/27-2-anatomy-and-physiology-of-the-female-reproductive-system/

- Lee, M. Y., et al. (2015). Clinical pathology of Bartholin’s glands: A review of the literature. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4483306/

- The female reproductive system. (n.d.). https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-ap/chapter/the-female-reproductive-system/

- Vulvar anatomy. (n.d.). https://www.nva.org/what-is-vulvodynia/vulvar-anatomy/

- Zucca-Matthes, G., et al. (2016). Anatomy of the nipple and breast ducts. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4716863/

Share this article

Latest news

- Wearable tech uses AI to detect cardiac arrhythmia 30 minutes before onset

- Artificial sweetener neotame may have potential to damage gut, lead to IBS

- AI tool may help detect cancer in a few minutes with a drop of blood

- Regularly eating avocado linked to lower diabetes risk in women

- Misplaced your keys? How to distinguish dementia from normal age-related memory loss

Related Coverage

Some women report experiencing intense sexual pleasure from the stimulation of an area in the vagina called the G-spot. Others may think they do not…

Summary description Female sex hormones, or sex steroids, play crucial roles in sexual development, sexual desire, and reproduction. They also…

Everyone has different nutritional needs. The requirements for vitamins and minerals will also vary according to the person's age, activity levels…

Ovarian cysts, endometriosis, or uterine fibroids can cause pelvic pain. Learn what else causes pelvic pain in females and when to see a doctor.

Researchers say Black women with poor cardiovascular health have a higher risk of cognitive decline in older age than white woman

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.10: The Psychology of Human Sexuality

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 10807

- https://nobaproject.com/ via The Noba Project

Northwest Vista College

Sexuality is one of the fundamental drives behind everyone’s feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. It defines the means of biological reproduction, describes psychological and sociological representations of self, and orients a person’s attraction to others. Further, it shapes the brain and body to be pleasure-seeking. Yet, as important as sexuality is to being human, it is often viewed as a taboo topic for personal or scientific inquiry.

Learning Objectives

- Explain how scientists study human sexuality.

- Share a definition of human sexuality.

- Distinguish between sex, gender, and sexual orientation.

- Review common and alternative sexual behaviors.

- Appraise how pleasure, sexual behaviors, and consent are intertwined.

Introduction

Sex makes the world go around: It makes babies bond, children giggle, adolescents flirt, and adults have babies. It is addressed in the holy books of the world’s great religions, and it infiltrates every part of society. It influences the way we dress, joke, and talk. In many ways, sex defines who we are. It is so important, the eminent neuropsychologist Karl Pribram (1958) described sex as one of four basic human drive states. Drive states motivate us to accomplish goals. They are linked to our survival. According to Pribram, feeding, fighting, fleeing, and sex are the four drives behind every thought, feeling, and behavior. Since these drives are so closely associated with our psychological and physical health, you might assume people would study, understand, and discuss them openly. Your assumption would be generally correct for three of the four drives (Malacane & Beckmeyer, 2016). Can you guess which drive is the least understood and openly discussed?

This module presents an opportunity for you to think openly and objectively about sex. Without shame or taboo, using science as a lens, we examine fundamental aspects of human sexuality—including gender, sexual orientation, fantasies, behaviors, paraphilias, and sexual consent.

The History of Scientific Investigations of Sex

The history of human sexuality is as long as human history itself—200,000+ years and counting (Antón & Swisher, 2004). For almost as long as we have been having sex, we have been creating art, writing, and talking about it. Some of the earliest recovered artifacts from ancient cultures are thought to be fertility totems. The Hindu Kama Sutra (400 BCE to 200 CE)—an ancient text discussing love, desire, and pleasure—includes a how-to manual for having sexual intercourse. Rules, advice, and stories about sex are also contained in the Muslim Qur’an , Jewish Torah, and Christian Bible .

By contrast, people have been scientifically investigating sex for only about 125 years. The first scientific investigations of sex employed the case study method of research. Using this method, the English physician Henry Havelock Ellis (1859-1939) examined diverse topics within sexuality, including arousal and masturbation. From 1897 to 1923, his findings were published in a seven-volume set of books titled Studies in the Psychology of Sex. Among his most noteworthy findings is that transgender people are distinct from homosexual people. Ellis’s studies led him to be an advocate of equal rights for women and comprehensive human sexuality education in public schools.

Using case studies, the Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) is credited with being the first scientist to link sex to healthy development and to recognize humans as being sexual throughout their lifespans, including childhood (Freud, 1905). Freud (1923) argued that people progress through five stages of psychosexual development : oral, anal, phallic, latent, and genital. According to Freud, each of these stages could be passed through in a healthy or unhealthy manner. In unhealthy manners, people might develop psychological problems, such as frigidity, impotence, or anal-retentiveness.

The American biologist Alfred Kinsey (1894-1956) is commonly referred to as the father of human sexuality research. Kinsey was a world-renowned expert on wasps but later changed his focus to the study of humans. This shift happened because he wanted to teach a course on marriage but found data on human sexual behavior lacking. He believed that sexual knowledge was the product of guesswork and had never really been studied systematically or in an unbiased way. He decided to collect information himself using the survey method , and set a goal of interviewing 100 thousand people about their sexual histories. Although he fell short of his goal, he still managed to collect 18 thousand interviews! Many “behind closed doors” behaviors investigated by contemporary scientists are based on Kinsey’s seminal work.

Today, a broad range of scientific research on sexuality continues. It’s a topic that spans various disciplines, including anthropology, biology, neurology, psychology, and sociology.

Sex, Gender, and Sexual Orientation: Three Different Parts of You

Applying for a credit card or filling out a job application requires your name, address, and birth-date. Additionally, applications usually ask for your sex or gender. It’s common for us to use the terms “sex” and “gender” interchangeably. However, in modern usage, these terms are distinct from one another.

Sex describes means of biological reproduction. Sex includes sexual organs, such as ovaries—defining what it is to be a female—or testes—defining what it is to be a male. Interestingly, biological sex is not as easily defined or determined as you might expect (see the section on variations in sex, below). By contrast, the term gender describes psychological ( gender identity ) and sociological ( gender role ) representations of biological sex. At an early age, we begin learning cultural norms for what is considered masculine and feminine. For example, children may associate long hair or dresses with femininity. Later in life, as adults, we often conform to these norms by behaving in gender-specific ways: as men, we build houses; as women, we bake cookies (Marshall, 1989; Money et al., 1955; Weinraub et al., 1984).

Because cultures change over time, so too do ideas about gender. For example, European and American cultures today associate pink with femininity and blue with masculinity. However, less than a century ago, these same cultures were swaddling baby boys in pink, because of its masculine associations with “blood and war,” and dressing little girls in blue, because of its feminine associations with the Virgin Mary (Kimmel, 1996).

Sex and gender are important aspects of a person’s identity. However, they do not tell us about a person’s sexual orientation (Rule & Ambady, 2008). Sexual orientation refers to a person’s sexual attraction to others. Within the context of sexual orientation, sexual attraction refers to a person’s capacity to arouse the sexual interest of another, or, conversely, the sexual interest one person feels toward another.

While some argue that sexual attraction is primarily driven by reproduction (e.g., Geary, 1998), empirical studies point to pleasure as the primary force behind our sex drive. For example, in a survey of college students who were asked, “Why do people have sex?” respondents gave more than 230 unique responses, most of which were related to pleasure rather than reproduction (Meston & Buss, 2007). Here’s a thought-experiment to further demonstrate how reproduction has relatively little to do with driving sexual attraction: Add the number of times you’ve had and hope to have sex during your lifetime. With this number in mind, consider how many times the goal was (or will be) for reproduction versus how many it was (or will be) for pleasure. Which number is greater?

Although a person’s intimate behavior may have sexual fluidity —changing due to circumstances (Diamond, 2009)—sexual orientations are relatively stable over one’s lifespan, and are genetically rooted (Frankowski, 2004). One method of measuring these genetic roots is the sexual orientation concordance rate (SOCR). An SOCR is the probability that a pair of individuals has the same sexual orientation. SOCRs are calculated and compared between people who share the same genetics ( monozygotic twins , 99%); some of the same genetics ( dizygotic twins , 50%); siblings (50%); and non-related people, randomly selected from the population. Researchers find SOCRs are highest for monozygotic twins; and SOCRs for dizygotic twins, siblings, and randomly-selected pairs do not significantly differ from one another (Bailey et al. 2016; Kendler et al., 2000). Because sexual orientation is a hotly debated issue, an appreciation of the genetic aspects of attraction can be an important piece of this dialogue.

On Being Normal: Variations in Sex, Gender, and Sexual Orientation

“ Only the human mind invents categories and tries to force facts into separated pigeon-holes. The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects. The sooner we learn this concerning human sexual behavior, the sooner we shall reach a sound understanding of the realities of sex. ” (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948, pp. 638–639)

We live in an era when sex, gender, and sexual orientation are controversial religious and political issues. Some nations have laws against homosexuality, while others have laws protecting same-sex marriages. At a time when there seems to be little agreement among religious and political groups, it makes sense to wonder, “What is normal?” and, “Who decides?”

The international scientific and medical communities (e.g., World Health Organization, World Medical Association, World Psychiatric Association, Association for Psychological Science) view variations of sex, gender, and sexual orientation as normal. Furthermore, variations of sex, gender, and sexual orientation occur naturally throughout the animal kingdom. More than 500 animal species have homosexual or bisexual orientations (Lehrer, 2006). More than 65,000 animal species are intersex —born with either an absence or some combination of male and female reproductive organs, sex hormones, or sex chromosomes (Jarne & Auld, 2006). In humans, intersex individuals make up about two percent—more than 150 million people—of the world’s population (Blackless et al., 2000). There are dozens of intersex conditions, such as Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome and Turner’s Syndrome (Lee et al., 2006). The term “syndrome” can be misleading; although intersex individuals may have physical limitations (e.g., about a third of Turner’s individuals have heart defects; Matura et al., 2007), they otherwise lead relatively normal intellectual, personal, and social lives. In any case, intersex individuals demonstrate the diverse variations of biological sex.

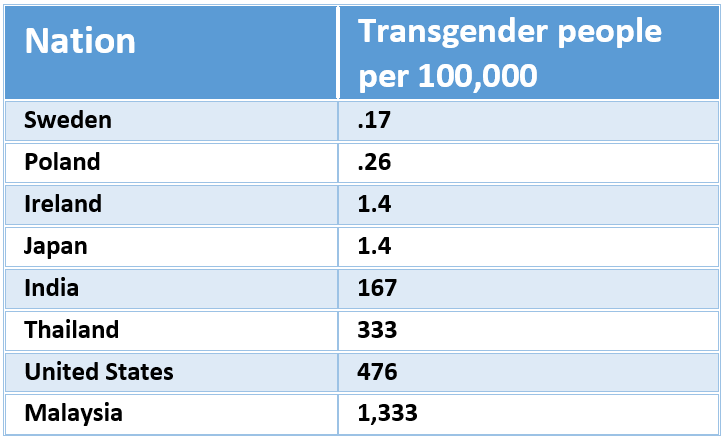

Just as biological sex varies more widely than is commonly thought, so too does gender. Cisgender individuals’ gender identities correspond with their birth sexes, whereas transgender individuals’ gender identities do not correspond with their birth sexes. Because gender is so deeply ingrained culturally, rates of transgender individuals vary widely around the world (see Table 1).

Although incidence rates of transgender individuals differ significantly between cultures, transgender females (TGFs) —whose birth sex was male—are by far the most frequent type of transgender individuals in any culture. Of the 18 countries studied by Meier and Labuski (2013), 16 of them had higher rates of TGFs than transgender males (TGMs) —whose birth sex was female— and the 18 country TGF to TGM ratio was 3 to 1. TGFs have diverse levels of androgyny —having both feminine and masculine characteristics. For example, five percent of the Samoan population are TGFs referred to as fa'afafine , who range in androgyny from mostly masculine to mostly feminine (Tan, 2016); in Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, TGFs are referred to as hijras, recognized by their governments as a third gender, and range in androgyny from only having a few masculine characteristics to being entirely feminine (Pasquesoone, 2014); and as many as six percent of biological males living in Oaxaca, Mexico are TGFs referred to as muxes , who range in androgyny from mostly masculine to mostly feminine (Stephen, 2002).

Sexual orientation is as diverse as gender identity. Instead of thinking of sexual orientation as being two categories—homosexual and heterosexual—Kinsey argued that it’s a continuum (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948). He measured orientation on a continuum, using a 7-point Likert scale called the Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale, in which 0 is exclusively heterosexual , 3 is bisexual , and 6 is exclusively homosexual . Later researchers using this method have found 18% to 39% of Europeans and Americans identifying as somewhere between heterosexual and homosexual (Lucas et al., 2017; YouGov.com, 2015). These percentages drop dramatically (0.5% to 1.9%) when researchers force individuals to respond using only two categories (Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016; Gates, 2011).

What Are You Doing? A Brief Guide to Sexual Behavior

Just as we may wonder what characterizes particular gender or sexual orientations as “normal,” we might have similar questions about sexual behaviors. What is considered sexually normal depends on culture. Some cultures are sexually-restrictive—such as one extreme example off the coast of Ireland, studied in the mid-20th century, known as the island of Inis Beag . The inhabitants of Inis Beag detested nudity and viewed sex as a necessary evil for the sole purpose of reproduction. They wore clothes when they bathed and even while having sex. Further, sex education was nonexistent, as was breast feeding (Messenger, 1989). By contrast, Mangaians , of the South Pacific island of A’ua’u, are an example of a highly sexually-permissive culture. Young Mangaian boys are encouraged to masturbate. By age 13, they’re instructed by older males on how to sexually perform and maximize orgasms for themselves and their partners. When the boys are a bit older, this formal instruction is replaced with hands-on coaching by older females. Young girls are also expected to explore their sexuality and develop a breadth of sexual knowledge before marriage (Marshall & Suggs, 1971). These cultures make clear that what are considered sexually normal behaviors depends on time and place.

Sexual behaviors are linked to, but distinct from, fantasies. Leitenberg and Henning (1995) define sexual fantasies as “any mental imagery that is sexually arousing.” One of the more common fantasies is the replacement fantasy —fantasizing about someone other than one’s current partner (Hicks & Leitenberg, 2001). In addition, more than 50% of people have forced-sex fantasies (Critelli & Bivona, 2008). However, this does not mean most of us want to be cheating on our partners or be involved in sexual assault. Sexual fantasies are not equal to sexual behaviors.

Sexual fantasies are often a context for the sexual behavior of masturbation —tactile (physical) stimulation of the body for sexual pleasure. Historically, masturbation has earned a bad reputation; it’s been described as “self-abuse,” and falsely associated with causing adverse side effects, such as hairy palms, acne, blindness, insanity, and even death (Kellogg, 1888). However, empirical evidence links masturbation to increased levels of sexual and marital satisfaction, and physical and psychological health (Hurlburt & Whitaker, 1991; Levin, 2007). There is even evidence that masturbation significantly decreases the risk of developing prostate cancer among males over the age of 50 (Dimitropoulou et al., 2009). Masturbation is common among males and females in the U.S. Robbins et al. (2011) found that 74% of males and 48% of females reported masturbating. However, frequency of masturbation is affected by culture. An Australian study found that only 58% of males and 42% of females reported masturbating (Smith, Rosenthal, & Reichler, 1996). Further, rates of reported masturbation by males and females in India are even lower, at 46% and 13%, respectively (Ramadugu et al., 2011).

Coital sex is the term for vaginal-penile intercourse, which occurs for about 3 to 13 minutes on average—though its duration and frequency decrease with age (Corty & Guardiani, 2008; Smith et al., 2012). Traditionally, people are known as “virgins” before they engage in coital sex, and have “lost” their virginity afterwards. Durex (2005) found the average age of first coital experiences across 41 different countries to be 17 years, with a low of 16 (Iceland), and a high of 20 (India). There is tremendous variation regarding frequency of coital sex. For example, the average number of times per year a person in Greece (138) or France (120) engages in coital sex is between 1.6 and 3 times greater than in India (75) or Japan (45; Durex, 2005).

Oral sex includes cunnilingus —oral stimulation of the female’s external sex organs, and fellatio —oral stimulation of the male’s external sex organs. The prevalence of oral sex widely differs between cultures—with Western cultures, such as the U.S., Canada, and Austria, reporting higher rates (greater than 75%); and Eastern and African cultures, such as Japan and Nigeria, reporting lower rates (less than 10%; Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016; Malacad & Hess, 2010; Wylie, 2009). Not only are there differences between cultures regarding how many people engage in oral sex, there are differences in its very definition. For example, most college students in the U.S. do not believe cunnilingus or fellatio are sexual behaviors—and more than a third of college students believe oral sex is a form of abstinence (Barnett et al., 2017; Horan, Phillips, & Hagan, 1998; Sanders & Reinisch, 1999).

Anal sex refers to penetration of the anus by an object. Anal sex is not exclusively a “homosexual behavior.” The anus has extensive sensory-nerve innervation and is often experienced as an erogenous zone, no matter where a person is on the Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale (Cordeau et al., 2014). When heterosexual people are asked about their sexual behaviors, more than a third (about 40%) of both males and females report having had anal sex at some time during their life (Chandra, Mosher, & Copen, 2011; Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016). Comparatively, when homosexual men are asked about their most recent sexual behaviors, more than a third (37%) report having had anal sex (Rosenberger et al., 2011). Like heterosexual people, homosexual people engage in a variety of sexual behaviors, the most frequent being masturbation, romantic kissing, and oral sex (Rosenberger et al., 2011). The prevalence of anal sex widely differs between cultures. For example, people in Greece and Italy report high rates of anal sex (greater than 50%), whereas people in China and India report low rates of anal sex (less than 15%; Durex, 2005).

In contrast to “more common” sexual behaviors, there is a vast array of alternative sexual behaviors. Some of these behaviors, such as voyeurism , exhibitionism , and pedophilia are classified in the DSM as paraphilic disorders —behaviors that victimize and cause harm to others or one’s self (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Sadism —inflicting pain upon another person to experience pleasure for one’s self—and masochism —receiving pain from another person to experience pleasure for one’s self—are also classified in the DSM as paraphilic disorders. However, if an individual consensually engages in these behaviors, the term “disorder” is replaced with the term “interest.” Janus and Janus (1993) found that 14% of males and 11% of females have engaged in some form of sadism and/or masochism.

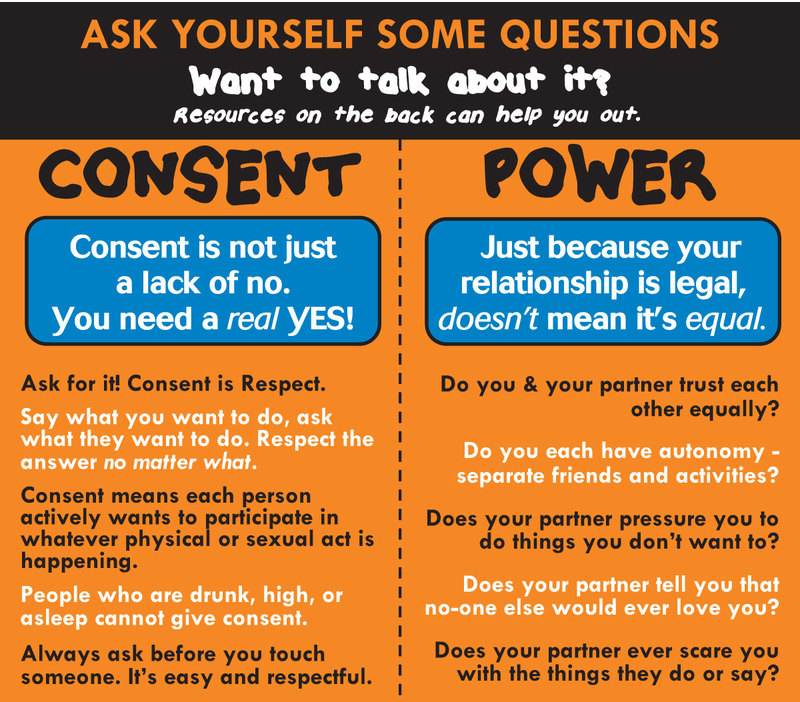

Sexual Consent

Clearly, people engage in a multitude of behaviors whose variety is limited only by our own imaginations. Further, our standards for what’s normal differs substantially from culture to culture. However, there is one aspect of sexual behavior that is universally acceptable—indeed, fundamental and necessary. At the heart of what qualifies as sexually “normal” is the concept of consent. Sexual consent refers to the voluntary, conscious, and empathic participation in a sexual act, which can be withdrawn at any time (Jozkowski & Peterson, 2013). Sexual consent is the baseline for what are considered normal —acceptable and healthy—behaviors; whereas, nonconsensual sex—i.e., forced, pressured or unconscious participation—is unacceptable and unhealthy. When engaging in sexual behaviors with a partner, a clear and explicit understanding of your boundaries, as well as your partner’s boundaries, is essential. We recommend safer-sex practices , such as condoms, honesty, and communication, whenever you engage in a sexual act. Discussing likes, dislikes, and limits prior to sexual exploration reduces the likelihood of miscommunication and misjudging nonverbal cues. In the heat of the moment, things are not always what they seem. For example, Kristen Jozkowski and her colleagues (2014) found that females tend to use verbal strategies of consent, whereas males tend to rely on nonverbal indications of consent. Awareness of this basic mismatch between heterosexual couples’ exchanges of consent may proactively reduce miscommunication and unwanted sexual advances.

The universal principles of pleasure, sexual behaviors, and consent are intertwined. Consent is the foundation on which sexual activity needs to be built. Understanding and practicing empathic consent requires sexual literacy and an ability to effectively communicate desires and limits, as well as to respect others’ parameters.

Considering the amount of attention people give to the topic of sex, it’s surprising how little most actually know about it. Historically, people’s beliefs about sexuality have emerged as having absolute moral, physical, and psychological boundaries. The truth is, sex is less concrete than most people assume. Gender and sexual orientation, for example, are not either/or categories. Instead, they are continuums. Similarly, sexual fantasies and behaviors vary greatly by individual and culture. Ultimately, open discussions about sexual identity and sexual practices will help people better understand themselves, others, and the world around them.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Robert Biswas-Diener, Trina Cowan, Kara Paige, and Liz Wright for editing drafts of this module.

Outside Resources

Discussion Questions

- Of the four basic human drive states Karl Pribram describes as being linked to our survival, why do you think the sex drive is the least likely to be openly and objectively addressed?

- How might you go about scientifically investigating attitudes and behaviors regarding masturbation across various cultures?

- Discuss the three different parts of you as described by this module.

- How would you define “natural” human sexual behavior with respect to sex, gender, and sexual orientation? How does nature (i.e., the animal kingdom) help us define what is considered natural?

- Why do humans feel compelled to categorize themselves and others based on their sex, gender, and sexual orientation? What would the world be like if these categories were removed?

- How has culture influenced your sexual attitudes and behaviors?

- The concept of sexual consent is seemingly simple; however, as this module presents, it is oftentimes skewed or ignored. Identify at least three factors that contribute to the complexities of consent, and how these factors might best be addressed to reduce unwanted sexual advances.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Antón, S. C., & Swisher III, C. C. (2004). Early dispersals of homo from Africa. Annual Review of Anthropology , 33, 271–296.

- Bailey, J. M., Vasey, P. L., Diamond, L. M., Breedlove, S. M., Vilain, E., & Epprecht, M. (2016). Sexual orientation, controversy, and science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest , 17, 45-101

- Barnett, M. D., Fleck, L. K., Marsden, A. D., & Martin, K. J. (2017). Sexual semantics: The meanings of sex, virginity, and abstinence for university students. Personality and Individual Differences , 106, 203–208.

- Blackless, M., Charuvastra, A., Derryck, A., Fausto-Sterling, A., Lauzanne, K., & Lee, E. (2000). How sexually dimorphic are we? Review and synthesis. American Journal of Human Biology , 12, 151-166.

- Chandra, A., Mosher, W. D., & Copen, C. (2011). Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: Data From the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Report , 36, 1-35.

- Conron, J., Scott, G., Stowell, G. S., & Landers, S. (2012). Transgender health in Massachusetts: Results from a household probability sample of adults. American Journal of Public Health , 102, 118–122.

- Copen, C., Chandra, A., & Febo-Vazquez, I. (2016). Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual orientation among adults aged 18–44 in the United States: Data from the 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports , 88, 1-13.

- Cordeau, D., Bélanger, M., Beaulieu-Prévost, D., & Courtois, F. (2014). The assessment of sensory detection thresholds on the perineum and breast compared with control body sites. Journal of Sexual Medicine , 11, 1741–1748.

- Corty, E. W., &, Guardiani, J. M. (2008). Canadian and American sex therapists perceptions of normal and abnormal ejaculatory latencies: How long should intercourse last? Journal of Sexual Medicine , 5, 1251-1256.

- Critelli, J. W., & Bivona, J. M. (2008). Women\'s erotic rape fantasies: An evaluation of theory and research. The Journal of Sex Research , 45, 57-70.

- De Gascun, C., Kelly, J., Salter, N., Lucey, J., & O’Shea, D. (2006). Gender identity disorder. Irish Medical Journal , 99, 146–148.

- Diamond, L. M. (2009). Sexual Fluidity: Understanding Women’s Love and Desire . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Dimitropoulou, P., Lophatananon, A., Easton, D., Pocock, R., Dearnaley, D. P., Guy, M., Edwards, S., O\\\'Brien, L., Hall, A., Wilkinson, R., Eeles, R., & Muir, K. R. (2009). Sexual activity and prostate cancer risk in men diagnosed at a younger age. British Journal of Urology International , 103, 178-85.

- Dulko, S., & Imielinskia, C. (2004). The epidemiology of transsexualism in Poland. Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 56, 637.

- Durex (2005). 2005 Global Sex Survey results. www.durexusa.com/about/global-research. Retrieved on March 22, 2017.

- Frankowski, B. L. (2004). Sexual orientation and adolescents. Pediatrics , 113, 1827–1832.

- Freud, S. (1923/1990). The Ego and the Id . New York: WW Norton & Co.

- Freud, S. (1905/2000). Three essays on the theory of sexuality . New York: Basic Books.

- Gates, G. (2011). How Many People are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender? Williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu.

- Geary, D. C. (1998). Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences . Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

- Hicks, T. V., & Leitenberg, H. (2001). Sexual fantasies about one’s partner versus someone else: Gender differences in incidence and frequency. Journal of Sex Research , 38, 43-51.

- Horan, P. F., Phillips, J., & Hagan, N. E. (1998). The meaning of abstinence for college students. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents & Children , 2, 51–66.

- Hurlburt, D., & Whitaker, K. (1991). The role of masturbation in marital and sexual satisfaction. A comparative study of female masturbators and nonmasturbators, Journal of Sex Education and Therapy , 17, 99-102.

- Janus, S. S., & Janus, C. L. (1993). The Janus Report on Sexual Behavior . Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons.

- Jarne, P., & Auld, J. R. (2006). Animals mix it up too: The distribution of self-fertilization among hermaphroditic animals. Evolution , 60, 1816–1824.

- Jozkowski, K., N., & Peterson, Z. D. (2013). College students and sexual consent: Unique insights. Journal of Sex Research , 50, 517-523.

- Jozkowski, K., N., Peterson, Z. D., Sanders, S. A., Dennis, B., & Reece, M. (2014). Gender differences in heterosexual college students\\\' conceptualizations and indicators of sexual consent: implications for contemporary sexual assault prevention education. Journal of Sex Research , 51, 904-916.

- Kellogg, J. H. (1888). Treatment for Self-Abuse and Its Effects. Plain Facts for Old and Young . Burlington, Iowa: F. Segner & Co.

- Kendler, K. S., Thornton, L. M., Gilman, S. E., & Kessler, R. C. (2000). Sexual orientation in a U.S. national sample of twin and nontwin sibling pairs. American Journal of Psychiatry , 157, 1843–1846.

- Kimmell, M. (1996). Manhood in America: A Cultural History , Oxford University Press.

- Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual Behavior in the Human Male . Philadelphia: Saunders.

- Landen, M., Walinder, J., & Lundstrom, B. (1996). Prevalence, incidence and sex ratio of transsexualism. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica , 93, 221–223.

- Lee, P. A., Houk, C. P., Ahmed, S. F., & Hughes, L. A. (2006). Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders, Pediatrics , 118, 148-162.

- Lehrer, J. (2006). The effeminate sheep and other problems with Darwinian sexual selection. Seed Magazine , June/July.

- Leitenberg, H., & Henning, K. (1995). Sexual fantasy. Psychological Bulletin , 117, 469-496.

- Levin, R. J. (2007). Sexual activity, health and well-being—The beneficial roles of coitus and masturbation. Sexual and Relationship Therapy , 22, 135-148.

- Lucas, D. R., Hanich, Z., Gurian, A., Lee, S., & Sanchez, A. (2017). Measuring Sex, Gender, and Orientation on a True Continuum . Presented at the annual meeting of the Southwestern Psychological Association in San Antonio, Texas.

- Malacad, B. L., & Hess, G. C. (2010). Oral sex: Behaviours and feelings of Canadian young women and implications for sex education. The European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care , 15, 177-185.

- Malacane, M., & Beckmeyer, J. J. (2016). A review of parent-based barriers to parent–adolescent communication about sex and sexuality: Implications for sex and family educators. American Journal of Sexuality Education , 11, 27-40.

- Marshall, D. S., & Suggs, R. C. (1971). Human Sexual Behavior: Variations in the Ethnographic Spectrum . New York: Basic Books.

- Marshall, H. H. (1989). The development of self-concept. Young Children , 44, 44-51.

- Matura, L. A., Ho, V. B., Rosing, D. R., Bondy, C. A. (2007). Aortic dilatation and dissection in Turner syndrome. Circulation , 116, 1663-70.

- Meier, S. C., & Labuski, C. M. (2013). The Demographics of the Transgender Population, in A.K. Baumle (ed.), International Handbook on the Demography of Sexuality, International Handbooks of Population, Volume 5. Netherlands: Springer.

- Messenger, J. C. (1989). Ines Beag Revisited: The Anthropologist as Observant Participator . Salem, Wisconsin: Sheffield.

- Meston, C. M., & Buss, D. M. (2007). Why humans have sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior , 36, 477-507.

- Money, J., Hampson, J. G., & Hampson, J. (1955). An examination of some basic sexual concepts: The evidence of human hermaphroditism. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital , 97, 301–319.

- Okabe, N., Sato, T., Matsumoto, Y., Ido, Y., Terada, S., & Kuroda, S. (2008). Clinical characteristics of patients with gender identity disorder at a Japanese gender identity disorder clinic. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health , 157, 315–318.

- Pasquesoone, V. (2014). 7 Countries Giving Transgender People Fundamental Rights the U.S. Still Won\\\'t . mic.com. Retrieved on February 17, 2017.

- Pribram, K. H. (1958). Comparative Neurology and the Evolution of Behavior . In Roe, A., & Simpson, G.G. (eds.) Behavior and Evolution. Yale University Press.

- Ramadugu, S., Ryali, V., Srivastava, K., Bhat, P. S., & Prakash, J. (2011). Understanding sexuality among Indian urban school adolescents. Industrial Psychiatry Journal , 20, 49–55.

- Robbins, C. L., Schick, V., Reece, M., Herbenick, D., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2011). Prevalence, frequency, and associations of masturbation with partnered sexual behaviors among US adolescents. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine , 165, 1087-1093.

- Rosenberger, J. G., Reece, M., Schick, V., Herbenick, D., Novak, D. S., Van Der Pol, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2011). Sexual behaviors and situational characteristics of most recent male‐partnered sexual event among gay and bisexually identified men in the United States. The Journal of Sexual Medicine , 8, 3040-3050.

- Rule, N., & Ambady, N. (2008). Brief exposures: Male sexual orientation is accurately perceived at 50ms. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 44, 1100-1105.

- Sanders, S. A., &, Reinisch, J. M. (1999). Would you say you “had sex” if…? Journal of the American Medical Association , 281, 275–277.

- Smith, A. M., Patrick, K., Heywood, W., Pitts, M. K., Richters, J., Shelly, J.M., Simpson, J. K., & Ryall, R. (2012). Sexual practices and the duration of last heterosexual encounter: Findings from the Australian longitudinal study of health and relationships. Journal of Sex Research , 49, 487-494.

- Smith, A. M., Rosenthal, D. A., & Reichler, H. (1996). High schoolers masturbatory practices: Their relationship to sexual intercourse and personal characteristics. Psychological Reports , 79, 499-509.

- Stephen, L. (2002). Sexualities and genders in Zapotec Oaxaca. Latin American Perspectives , 29, 41-59.

- Tan, Y. (2016). Miss Fa\'afafine: Behind Samoa\'s \'third gender\' beauty pageant. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-37227803 . Retrieved on February 28, 2017.

- Weinraub, M., Clemens, L., Sockloff, A., Ethridge, T., Gracely, E., & Myers, B. (1984). The development of sex role stereotypes in the third year: Relationships to gender labeling, gender identity, sex-types toy preference, and family characteristics. Child Development , 55, 1493-1503.

- Winter, S. (2009). Transgender people in Asia and the Pacific: What does the research tell us? Presented to the Asia Pacific Transgender Network Development Conference, Bangkok, Thailand.

- Wylie, K. (2009). A global survey of sexual behaviours, Journal of Family and Reproductive Health , 3, 39-49.

- Youogov 1 in 2 young people say they are not 100% heterosexual Yougov.co.uk/news/2015/08/16/half-young-not-heterosexual. Retrieved on February 28, 2017.

Human Reproductive System

- Cell Biology

- Weather & Climate

- B.A., Biology, Emory University

- A.S., Nursing, Chattahoochee Technical College

The human reproductive system and the ability to reproduce make life possible. In sexual reproduction , two individuals produce offspring that have some of the genetic characteristics of both parents. The primary function of the human reproductive system is to produce sex cells . When a male and female sex cell unite, an offspring grows and develops.

The reproductive system is usually comprised of either male or female reproductive organs and structures. The growth and activity of these parts are regulated by hormones . The reproductive system is closely associated with other organ systems , particularly the endocrine system and urinary system.

Gamete Production

Gametes are produced by a two-part cell division process called meiosis . Through a sequence of steps, replicated DNA in a parent cell is distributed among four daughter cells . Meiosis produces gametes that are considered haploid because they have half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. Human sex cells contain one complete set of 23 chromosomes. When sex cells unite during fertilization , the two haploid sex cells become one diploid cell that contains all 46 chromosomes.

Spermatogenesis

The production of sperm cells is known as spermatogenesis . Stem cells develop into mature sperm cells by first dividing mitotically to produce identical copies of themselves and then meiotically to create unique daughter cells called spermatids. Spermatids then transform into mature spermatozoa through spermiogenesis. This process occurs continuously and takes place within the male testes. Hundreds of millions of sperm must be released in order for fertilization to take place.

Oogenesis (ovum development) occurs in the female ovaries. In meiosis I of oogenesis, daughter cells divide asymmetrically. This asymmetrical cytokinesis results in one large egg cell (oocyte) and smaller cells called polar bodies. The polar bodies degrade and are not fertilized. After meiosis I is complete, the egg cell is called a secondary oocyte. The haploid secondary oocyte will only complete the second meiotic stage if it encounters a sperm cell. Once fertilization is initiated, the secondary oocyte completes meiosis II and becomes an ovum. The ovum fuses with the sperm cell and fertilization completes while embryonic development begins. A fertilized ovum is called a zygote.

Reproductive System Disease

The reproductive system is susceptible to a number of diseases and disorders. These are of varying degrees of detriment to the body. This includes cancer that can develop in reproductive organs such as the uterus, ovaries, testicles, and prostate.

Disorders of the female reproductive system include endometriosis—a painful condition in which endometrial tissue develops outside of the uterus—ovarian cysts, uterine polyps, and uterine prolapse.

Disorders of the male reproductive system include testicular torsion—twisting of the testes—testicular under-activity resulting in low testosterone production called hypogonadism, enlarged prostate gland, swelling of the scrotum called hydrocele, and inflammation of the epididymis.

Reproductive Organs

Both male and female reproductive systems have internal and external structures. Reproductive organs are considered to be either primary or secondary organs based on their role. The primary reproductive organs of either system are called gonads (ovaries and testes) and these are responsible for gamete (sperm and egg cell) and hormone production. Other reproductive structures and organs are considered secondary reproductive structures and they aid in the growth and maturation of gametes and offspring.

Female Reproductive System

The female reproductive system is comprised of both internal and external reproductive organs that both enable fertilization and support embryonic development. Structures of the female reproductive system include:

- Labia majora: Larger lip-like external structures that cover and protect other reproductive structures.

- Labia minora: Smaller lip-like external structures found inside the labia majora. They provide protection to the clitoris, urethra, and vaginal openings.

- Clitoris: Sensitive sexual organ located in the uppermost section of the vaginal opening. The clitoris contains thousands of sensory nerve endings that respond to sexual stimulation and promote vaginal lubrication.

- Vagina: Fibrous, muscular canal leading from the cervix to the external portion of the genital canal. The penis enters the vagina during sexual intercourse.

- Cervix: Opening of the uterus. This strong, narrow structure expands to allow sperm to flow from the vagina into the uterus.

- Uterus: Internal organ that houses and nurtures female gametes after fertilization, commonly called the womb. A placenta, which encases a growing embryo, develops and attaches itself to the uterine wall during pregnancy. An umbilical cord stretches from the fetus to its placenta to provide nutrients from a mother to an unborn baby.

- Fallopian tubes: Uterine tubes that transport egg cells from the ovaries to the uterus. Fertile eggs are released from ovaries into fallopian tubes during ovulation and typically fertilized from there.

- Ovaries: Primary reproductive structures that produce female gametes (eggs) and sex hormones. There is one ovary on either side of the uterus.

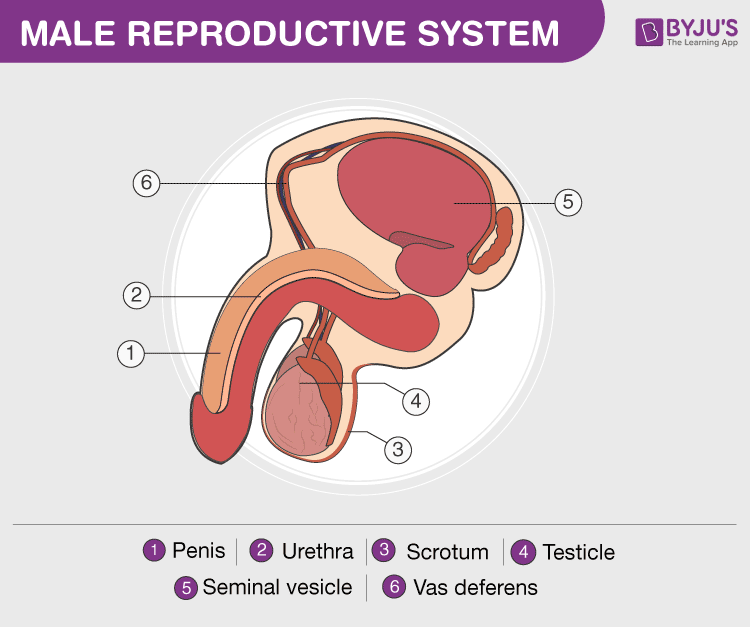

Male Reproductive System

The male reproductive system consists of sexual organs, accessory glands, and a series of duct systems that provide a pathway for sperm cells to exit the body and fertilize an egg. Male genitalia only equips an organism to initiate fertilization and does not support the development of a growing fetus. Male sex organs include:

- Penis: The main organ involved in sexual intercourse. This organ is composed of erectile tissue, connective tissue , and skin. The urethra stretches the length of the penis and allows either urine or sperm to pass through its external opening.

- Testes: Male primary reproductive structures that produce male gametes (sperm) and sex hormones. Testes are also called testicles.

- Scrotum: External pouch of skin that contains the testes. Because the scrotum is located outside of the abdomen, it can reach temperatures that are lower than that of internal body structures. Lower temperatures are necessary for proper sperm development.

- Epididymis: System of ducts that receive immature sperm from the testes. The epididymis functions to develop immature sperm and house mature sperm.

- Ductus Deferens or Vas Deferens: Fibrous, muscular tubes that are continuous with the epididymis and provide a pathway for sperm to travel from the epididymis to the urethra

- Urethra: Tube that extends from the urinary bladder through the penis. This canal allows for the excretion of reproductive fluids (semen) and urine from the body. Sphincters prevent urine from entering the urethra while semen is passing through.

- Seminal Vesicles: Glands that produce fluid to nurture and provide energy to sperm cells. Tubes leading from the seminal vesicles join the ductus deferens to form the ejaculatory duct.

- Ejaculatory Duct: Duct formed from the union of the ductus deferens and seminal vesicles. Each ejaculatory duct empties into the urethra.

- Prostate Gland: Gland that produces a milky, alkaline fluid that increases sperm motility. The contents of the prostate empty into the urethra.

- Bulbourethral or Cowper's Glands: Small glands located at the base of the penis. In response to sexual stimulation, these glands secrete an alkaline fluid which helps to neutralize acidity from the vagina and urine in the urethra.

- Farabee, M.J. The Reproductive System . Estrella Mountain Community College, 2007.

- " Introduction to the Reproductive System ." SEER Training Modules , National Cancer Institute | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- An Introduction to Male and Female Gonads

- Sex Cells Anatomy and Production

- Gametophyte Generation of the Plant Life Cycle

- What Is Parthenogenesis?

- 4 Types of Reproduction

- Plant Life Cycle: Alternation of Generations

- Sexual Reproduction Advantages and Disadvantages

- Learn About All the Different Organ Systems in the Human Body

- Types of Fertilization in Sexual Reproduction:

- Endocrine System Glands and Hormones

- How Chromosomes Determine Sex

- All About Haploid Cells in Microbiology

- Somatic Cells vs. Gametes

- Parts of a Flowering Plant

- Genetics Basics

Module 11: The Reproductive System

Development of the male and female reproductive systems, learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how bipotential tissues are directed to develop into male or female sex organs

- Name the rudimentary duct systems in the embryo that are precursors to male or female internal sex organs

- Describe the hormonal changes that bring about puberty, and the secondary sex characteristics of men and women

The development of the reproductive systems begins soon after fertilization of the egg, with primordial gonads beginning to develop approximately one month after conception. Reproductive development continues in utero, but there is little change in the reproductive system between infancy and puberty.

Development of the Sexual Organs in the Embryo and Fetus

Females are considered the “fundamental” sex—that is, without much chemical prompting, all fertilized eggs would develop into females. To become a male, an individual must be exposed to the cascade of factors initiated by a single gene on the male Y chromosome. This is called the SRY ( S ex-determining R egion of the Y chromosome). Because females do not have a Y chromosome, they do not have the SRY gene. Without a functional SRY gene, an individual will be female.

In both male and female embryos, the same group of cells has the potential to develop into either the male or female gonads; this tissue is considered bipotential. The SRY gene actively recruits other genes that begin to develop the testes, and suppresses genes that are important in female development. As part of this SRY -prompted cascade, germ cells in the bipotential gonads differentiate into spermatogonia. Without SRY , different genes are expressed, oogonia form, and primordial follicles develop in the primitive ovary.

Soon after the formation of the testis, the Leydig cells begin to secrete testosterone. Testosterone can influence tissues that are bipotential to become male reproductive structures. For example, with exposure to testosterone, cells that could become either the glans penis or the glans clitoris form the glans penis. Without testosterone, these same cells differentiate into the clitoris.

Not all tissues in the reproductive tract are bipotential. The internal reproductive structures (for example the uterus, uterine tubes, and part of the vagina in females; and the epididymis, ductus deferens, and seminal vesicles in males) form from one of two rudimentary duct systems in the embryo. For proper reproductive function in the adult, one set of these ducts must develop properly, and the other must degrade. In males, secretions from sustentacular cells trigger a degradation of the female duct, called the Müllerian duct . At the same time, testosterone secretion stimulates growth of the male tract, the Wolffian duct . Without such sustentacular cell secretion, the Müllerian duct will develop; without testosterone, the Wolffian duct will degrade. Thus, the developing offspring will be female. For more information and a figure of differentiation of the gonads, seek additional content on fetal development.

Practice Questions

A baby’s gender is determined at conception, and the different genitalia of male and female fetuses develop from the same tissues in the embryo. View this animation to see a comparison of the development of structures of the female and male reproductive systems in a growing fetus. Where are the testes located for most of gestational time?

Further Sexual Development Occurs at Puberty

Puberty is the stage of development at which individuals become sexually mature. Though the outcomes of puberty for boys and girls are very different, the hormonal control of the process is very similar. In addition, though the timing of these events varies between individuals, the sequence of changes that occur is predictable for male and female adolescents. As shown in the image below, a concerted release of hormones from the hypothalamus (GnRH), the anterior pituitary (LH and FSH), and the gonads (either testosterone or estrogen) is responsible for the maturation of the reproductive systems and the development of secondary sex characteristics , which are physical changes that serve auxiliary roles in reproduction.

The first changes begin around the age of eight or nine when the production of LH becomes detectable. The release of LH occurs primarily at night during sleep and precedes the physical changes of puberty by several years. In pre-pubertal children, the sensitivity of the negative feedback system in the hypothalamus and pituitary is very high. This means that very low concentrations of androgens or estrogens will negatively feed back onto the hypothalamus and pituitary, keeping the production of GnRH, LH, and FSH low.

As an individual approaches puberty, two changes in sensitivity occur. The first is a decrease of sensitivity in the hypothalamus and pituitary to negative feedback, meaning that it takes increasingly larger concentrations of sex steroid hormones to stop the production of LH and FSH. The second change in sensitivity is an increase in sensitivity of the gonads to the FSH and LH signals, meaning the gonads of adults are more responsive to gonadotropins than are the gonads of children. As a result of these two changes, the levels of LH and FSH slowly increase and lead to the enlargement and maturation of the gonads, which in turn leads to secretion of higher levels of sex hormones and the initiation of spermatogenesis and folliculogenesis.

In addition to age, multiple factors can affect the age of onset of puberty, including genetics, environment, and psychological stress. One of the more important influences may be nutrition; historical data demonstrate the effect of better and more consistent nutrition on the age of menarche in girls in the United States, which decreased from an average age of approximately 17 years of age in 1860 to the current age of approximately 12.75 years in 1960, as it remains today. Some studies indicate a link between puberty onset and the amount of stored fat in an individual. This effect is more pronounced in girls, but has been documented in both sexes. Body fat, corresponding with secretion of the hormone leptin by adipose cells, appears to have a strong role in determining menarche. This may reflect to some extent the high metabolic costs of gestation and lactation. In girls who are lean and highly active, such as gymnasts, there is often a delay in the onset of puberty.

Figure 1. Click to view a larger image. During puberty, the release of LH and FSH from the anterior pituitary stimulates the gonads to produce sex hormones in both male and female adolescents.

Signs of Puberty

Different sex steroid hormone concentrations between the sexes also contribute to the development and function of secondary sexual characteristics. Examples of secondary sexual characteristics are listed in Table 1.

As a girl reaches puberty, typically the first change that is visible is the development of the breast tissue. This is followed by the growth of axillary and pubic hair. A growth spurt normally starts at approximately age 9 to 11, and may last two years or more. During this time, a girl’s height can increase 3 inches a year. The next step in puberty is menarche, the start of menstruation.

In boys, the growth of the testes is typically the first physical sign of the beginning of puberty, which is followed by growth and pigmentation of the scrotum and growth of the penis. The next step is the growth of hair, including armpit, pubic, chest, and facial hair. Testosterone stimulates the growth of the larynx and thickening and lengthening of the vocal folds, which causes the voice to drop in pitch. The first fertile ejaculations typically appear at approximately 15 years of age, but this age can vary widely across individual boys. Unlike the early growth spurt observed in females, the male growth spurt occurs toward the end of puberty, at approximately age 11 to 13, and a boy’s height can increase as much as 4 inches a year. In some males, pubertal development can continue through the early 20s.

Chapter Review

The reproductive systems of males and females begin to develop soon after conception. A gene on the male’s Y chromosome called SRY is critical in stimulating a cascade of events that simultaneously stimulate testis development and repress the development of female structures. Testosterone produced by Leydig cells in the embryonic testis stimulates the development of male sexual organs. If testosterone is not present, female sexual organs will develop.

Whereas the gonads and some other reproductive tissues are considered bipotential, the tissue that forms the internal reproductive structures stems from ducts that will develop into only male (Wolffian) or female (Müllerian) structures. To be able to reproduce as an adult, one of these systems must develop properly and the other must degrade.

Further development of the reproductive systems occurs at puberty. The initiation of the changes that occur in puberty is the result of a decrease in sensitivity to negative feedback in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, and an increase in sensitivity of the gonads to FSH and LH stimulation. These changes lead to increases in either estrogen or testosterone, in female and male adolescents, respectively. The increase in sex steroid hormones leads to maturation of the gonads and other reproductive organs. The initiation of spermatogenesis begins in boys, and girls begin ovulating and menstruating. Increases in sex steroid hormones also lead to the development of secondary sex characteristics such as breast development in girls and facial hair and larynx growth in boys.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Identify the changes in sensitivity that occur in the hypothalamus, pituitary, and gonads as a boy or girl approaches puberty. Explain how these changes lead to the increases of sex steroid hormone secretions that drive many pubertal changes.

- Explain how the internal female and male reproductive structures develop from two different duct systems.

- Explain what would occur during fetal development to an XY individual with a mutation causing a nonfunctional SRY gene.

- As an individual approaches puberty, two changes in sensitivity occur. The first is a decrease of sensitivity in the hypothalamus and pituitary to negative feedback, meaning that it takes increasingly larger concentrations of sex steroid hormones to stop the production of LH and FSH. The second change in sensitivity is an increase in the sensitivity of the gonads to the FSH and LH signals, meaning that the gonads of adults are more responsive to gonadotropins than are the gonads of children. As a result of these two changes, the levels of LH and FSH slowly increase and lead to the enlargement and maturation of the gonads, which in turn leads to secretion of higher levels of sex hormones and the initiation of spermatogenesis and folliculogenesis.

- The internal reproductive structures form from one of two rudimentary duct systems in the embryo. Testosterone secretion stimulates growth of the male tract, the Wolffian duct. Secretions of sustentacular cells trigger a degradation of the female tract, the Müllerian duct. Without these stimuli, the Müllerian duct will develop and the Wolffian duct will degrade, resulting in a female embryo.

- If the SRY gene were not functional, the XY individual would be genetically a male, but would develop female reproductive structures.

Müllerian duct: duct system present in the embryo that will eventually form the internal female reproductive structures

puberty: life stage during which a male or female adolescent becomes anatomically and physiologically capable of reproduction

secondary sex characteristics: physical characteristics that are influenced by sex steroid hormones and have supporting roles in reproductive function

Wolffian duct: duct system present in the embryo that will eventually form the internal male reproductive structures

- Anatomy & Physiology. Provided by : OpenStax CNX. Located at : http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected] . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Magnetic resonance...

Magnetic resonance imaging of male and female genitals during coitus and female sexual arousal

- Related content

- Peer review

- Willibrord Weijmar Schultz , associate professor of gynaecology ( w.c.m.weymar.schultz{at}oprit.rug.nl ) a ,

- Pek van Andel , physiologist b ,

- Ida Sabelis , anthropologist d ,

- Eduard Mooyaart , radiologist c

- a Department of Gynaecology, University Hospital Groningen, PO Box 30 001, 9700 RB Groningen, Netherlands

- b Laboratory for Cell Biology and Electron Microscopy, University Hospital Groningen

- c Department of Radiology, University Hospital Groningen

- d Department of Business Anthropology VU, De Boelen 1081C-NL, 1081 HV, Amsterdam

- Correspondence to: W Weijmar Schultz

Objective: To find out whether taking images of the male and female genitals during coitus is feasible and to find out whether former and current ideas about the anatomy during sexual intercourse and during female sexual arousal are based on assumptions or on facts.

Design: Observational study.

Setting: University hospital in the Netherlands.

Methods: Magnetic resonance imaging was used to study the female sexual response and the male and female genitals during coitus. Thirteen experiments were performed with eight couples and three single women.

Results: The images obtained showed that during intercourse in the “missionary position” the penis has the shape of a boomerang and 1/3 of its length consists of the root of the penis. During female sexual arousal without intercourse the uterus was raised and the anterior vaginal wall lengthened. The size of the uterus did not increase during sexual arousal.

Conclusion: Taking magnetic resonance images of the male and female genitals during coitus is feasible and contributes to understanding of anatomy.

Introduction

“I expose to men the origin of their first, and perhaps second, reason for existing.” 1 Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) wrote these words above his drawing “The Copulation” in about 1493 (fig 1 ). 2 The Renaissance sketch shows a transparent view of the anatomy of sexual intercourse as envisaged by the anatomists of his time. The semen was supposed to come down from the brain through a channel which can be seen in the spine of the man. In the woman the right lactiferous duct is depicted as originating in the right female breast and ending in the genital area. Even a genius like Leonardo da Vinci distorted men's and women's bodies—as seen now—to fit the ideology of his time and to the notions of his colleagues, who he paid tribute to.

“The Copulation” as imagined and drawn by Leonardo da Vinci. 2 With permission from the Royal Collection. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II is gratefully acknowledged.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The first careful study—since the sketch by Leonardo da Vinci—of the interaction of male and female human genitals during coitus was published by Dickinson in 1933 (fig 2 ). 3 A glass test tube as big as a penis in erection inserted into the vagina of female subjects who were sexually aroused by clitoral stimulation (occasionally with a vibrator) guided him in constructing his pictorial supposition.

Midsagittal image of the anatomy of sexual intercourse envisaged by R L Dickinson and drawn by R S Kendall 3

In the 1960s Masters and Johnson made their assessments with an artificial penis that could mechanically imitate natural coitus and by “direct observation”—the introduction of a speculum and bimanual palpation. 4 5 Their most remarkable observations regarding sexual arousal in the woman were the backwards and upwards movements of the anterior vaginal wall (vaginal tenting) and a 50-100% greater volume of the uterus. This increase disappeared 10-20 minutes after orgasm When sexual excitement without orgasm occurred, the volume returned to normal in 30-60 minutes. Masters and Johnson presumed that the greater volume of the uterus was due to engorgement with blood However, they qualified their presumption: “In view of the artificial nature of the equipment, legitimate issue may be raised with the integrity of observed reaction patterns.” 4

In 1992 Riley et al published an ultrasound study on copulation. 6 The images were of relatively poor quality as they used hand held, self scanning equipment, and none of the images was overview. We used magnetic resonance imaging to study the anatomy and physiology of human sexual intercourse. Our search started in 1991 when one of us (PvA) saw a black and white slide of a midsagittal magnetic resonance image of the mouth and throat of a professional singer who was singing “aaa.” He remembered Leonardo's drawing and wondered whether it would be possible to take such an image of human coitus We decided to try, as an ad hoc “instrument-oriented” study, despite the unscientific and other irrelevant reactions we expected and received: honi soit, qui mal y pense.

Magnetic resonance imaging had already been used as a diagnostic tool to study erectile impotence 7 ; it is particularly attractive for this kind of study because it produces images with exquisite anatomical detail that are clearer than those obtained with ultrasonography or radiography, and—as far as we know—it is safe. The aim of the study was initially to find out whether taking images of the male and female genitals during coitus is feasible, and later whether former and current ideas about the anatomy during sexual intercourse and during female sexual arousal are based on assumptions or on facts.

Subjects and methods

The participants (pairs of men and women) were recruited by personal invitation and through a local scientific television programme Respondents were invited to participate if they met the following criteria: older than 18 years, intact uterus and ovaries, and a small to average weight/height index. The experimental procedure was explained in a letter sent to respondents along with an informed consent form. Participants were assured confidentiality, privacy, anonymity, and the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any time. After written informed consent had been obtained, the participants were invited to come for a scan when the equipment was available on a Saturday.

The tube in which the couple would have intercourse stood in a room next to a control room where the searchers were sitting behind the scanning console and screen. An improvised curtain covered the window between the two rooms, so the intercom was the only means of communication Imaging was first done in a 1.5 Tesla Philips magnet system (Gyroscan S15) and later in a 1.5 Tesla magnet system from Siemens Vision. To increase the space in the tube, the table was removed: the internal diameter of the tube is then 50 cm. The participants were asked to lie with pelvises near the marked centre of the tube and not to move during imaging. After a preview, 10 mm thick sagittal images were taken with a half-Fourier acquisition single shot turbo SE T2 weighted pulse sequence (HASTE) The echo time was 64 ms, with a repetition time of 4.4 ms With this fast acquisition technique, 11 slices of relatively good quality were obtained within 14 seconds.

Magnetic resonance imaging during coitus (8 couples) and sexual arousal (11 women)

- View inline

The volunteers were shown the equipment in the two rooms, and personal and gynaecological histories were taken. The experimental procedure was explained, and all investigators left the imaging room. After a preliminary image for positioning the true pelvis of the woman was taken, the first image was taken with her lying on her back (image 1). Then the male was asked to climb into the tube and begin face to face coitus in the superior position (image 2). After this shot—successful or not—the man was asked to leave the tube and the woman was asked to stimulate her clitoris manually and to inform the researchers by intercom when she had reached the preorgasmic stage. Then she stopped the autostimulation for a third image (image 3). After that image was taken the woman restarted the stimulation to achieve an orgasm. Twenty minutes after the orgasm, the fourth image was taken (image 4). At the end of the experiment, the images were evaluated in the presence of the participants.

Thirteen experiments were performed with eight couples (three couples performed two experiments each) and three single women. The table shows age, weight/height index, parity, type of contraception, female orgasm (yes/no), and the depth of penetration (partial or complete) No women reported having a “g-spot” or producing female ejaculation during orgasm. On two Saturdays in 1991 (experiments 1 and 2) the first couple succeeded with complete penetration that lasted sufficiently long for the images to be taken. The Philips 1.5 Tesla magnet system at that time required a relatively long acquisition time (52 seconds) and had a relatively poor signal: noise ratio. This gave low quality images with many movement artefacts. In 1996 the Siemens Vision 1.5 Tesla magnet system became available and provided the opportunity to continue our search for sharp images. Six couples succeeded in partial, though not complete, penetration (experiments 3 and 7-11). In 1998 sildenafil (Viagra) became available in the Netherlands The two couples in experiments 9 and 11 were invited to repeat the procedure one hour after the man had taken one 25 mg tablet of sildenafil. They succeeded with complete penetration that lasted long enough (12 seconds) for sharp images to be taken (experiments 12 and 13).

Midsagittal image of the anatomy of sexual intercourse (experiment 12). P=penis, Ur=urethra, Pe=perineum, U=uterus, S=symphysis, B=bladder, I=intestine, L5=lumbar 5, Sc=scrotum

Midsagittal images of sexual response in a multiparous woman (experiment 9): (left) at rest; (centre) pre-orgasmic phase; (right) 20 minutes after orgasm

Figure 3 shows a midsagittal image of the anatomy of sexual intercourse with the woman lying on her back and the man on top of her. The root of the penis (1/3 of the length) and the erect pendulous body (2/3 of the length) are visible. The pendulous part of the erect penis moved upwards at an angle of about 120° to the root of the penis, and almost parallel to the woman's spine. In all the experiments this phenomenon occurred in this coital position and was not related to the depth of penetration. In complete penetration the penis filled up the anterior fornix (experiments 1, 2 and 13) or the posterior fornix (experiment 12; fig 3 ). During intromission the pubic bones of the men and the women did not approach each other closely: the female pubic bone stayed about 4 cm cranial to that of the male. The uterus was raised by 2.4 cm. The changed configuration of the bladder was caused by penile stretching of the anterior vaginal wall during intromission, plus the raising of the uterus and the increase in bladder size as it filled. The subjective level of sexual arousal of the participants, men and women, during the experiment was described afterwards as average.