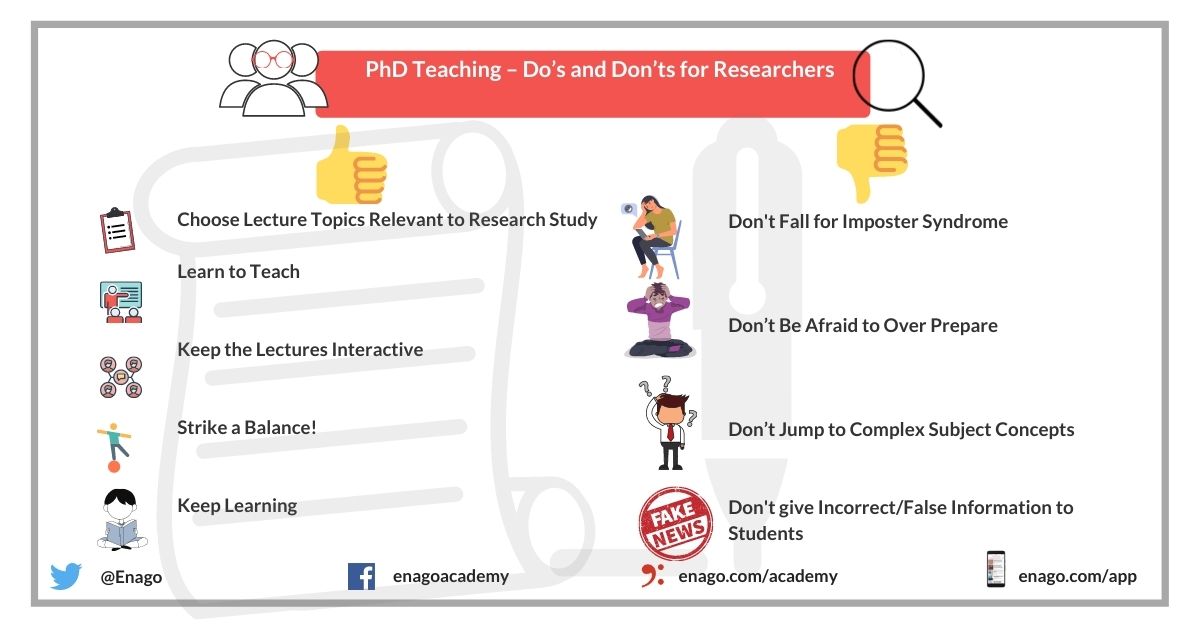

PhD Teaching – Do’s and Don’ts for Researchers

You might have come across a situation wherein you were asked to teach undergraduate students along with managing your research work! You had no understanding of how to go about teaching but your PI insisted on you taking up this responsibility. Teaching during PhD is an effective way of expanding your knowledge and getting an opportunity to share relevant objectives of your research with the undergraduates, piquing their interest in the subject field.

PhD teaching can be a challenging task for researchers, especially when they never had prior teaching experience. However, teaching during a doctoral program usually begins from the second year, so the researcher will have a year of doctoral experience before taking up the teaching responsibility. Some researchers opt for a voluntary teaching opportunity to gain PhD teaching experience. For research scholars working in STEM, teaching responsibilities include laboratory-based lectures, i.e. demonstrating scientific methods and techniques for undergraduate and Masters students, administrative work, conducting seminars, and assessments.

Table of Contents

PhD Teaching – What It Includes for Researchers

PhD teaching involves effective classroom teaching, academic advising, counselling students, participate in departmental work, develop a curriculum through assessment, attend professional conferences to explore current research, conduct and attend undergraduate and post graduate seminars and provide feedback, applied research and scholarly activity, etc. Additionally, teachers are also expected to adhere to academic policies and actively participate in collecting assessment data and work assignments.

Mostly academic teaching is a dreaded term for doctoral fellows because it appears as a time consuming additional activity. Researchers usually wish to avoid external responsibilities in an attempt to provide undivided attention to their research objectives. However, PhD teaching can be an added advantage for researchers.

PhD teaching benefits researchers by –

- Improving their presentation skills

- Refining their subject knowledge

- Giving researchers an opportunity to impart their research knowledge

- Increasing their ability to resolve queries raised by students.

Teaching Undergraduates is a Challenge for Researchers

Teaching needs a variety of skill sets ranging from creating a lesson plan, instructing students, working with administrators to counseling students. While researchers are busy building their academic reputation by publishing, obtaining funds, and demonstrating research impact , teaching-related activities (often neglected) are an effective way to demonstrate a researcher’s development.

Academic teaching activities instill skills like effective oral communication, leadership quality, self-reflection to adapt and refine techniques, and time management to balance teaching alongside PhD study. However, researchers are caught up in conducting their independent research work and self-management, which makes it difficult for them to hone these skills.

Ways to Improve PhD Teaching Skills

1. choose lecture topics relevant to research study.

A researcher should cater to the queries of the students, but taking up a subject matter that the researcher is an expert in, helps the research scholar prepare an effective lesson plan. Furthermore, it helps in effectively responding to the queries raised by students.

2. Learn to Teach

For scholars who have never conducted lectures, the first one can be daunting! However, attending workshops on how to teach can help researchers improve uncertainty and boost confidence to teach. There is always a first time to everything. Your key to a successful lecture delivery is being well prepared.

3. Keep the Lectures Interactive

Always allow students to speak up their thoughts about the topic of the lecture. This helps the you weave a story or a real life experience around the discussion, initiated by students. Moreover, it makes students feel they are equally involved in learning a new topic. Share your professional experiences with regards to your research work. This will help students get insights on how the practical field of their theoretical knowledge functions.

4. Observe Peers and Accept Feedback

The best way to learn PhD teaching techniques is to observe the supervisors, peers, and other departmental staff in their roles. This may help researchers follow different teaching techniques and new ways to engage students in the course work. Furthermore, the feedback received from supervisors or peers help researchers in getting a different perspective towards teaching and its techniques.

5. Strike a Balance!

When teaching alongside PhD, it is important to strike a balance between the two. Teaching activity is different from working on one’s research objectives. Research work is more independent and requires discussions only with the supervisor. While PhD teaching is completely based on communication skills and effective interaction. What matters the most is, how a researcher strikes a perfect balance between the two. Researchers can share their experiences from the research project and build their presentation skills from their teaching activity.

6. Keep Learning

Finally, after following and adapting teaching techniques and getting familiar with the balance between PhD research and academic teaching, you may face occasional disappointments and frustration, or even struggle to make impressive lesson plans. However, perseverance towards achieving your goals is the key to excel as an academic teacher.

Avoid these While Academic Teaching

Ignore the imposter syndrome.

Imposter syndrome is a feeling of hiding one’s secret incompetence and insecurity and thinking they don’t have sufficient knowledge the research requires. This is an extremely common issue in early career researchers . It is essential to believe that you have enough expertise to be teaching university students.

Don’t Be Afraid to Over Prepare

Initially, you may want to put in extra efforts in creating the lesson plan and doing an in-depth study. This is a plus for researchers who are stepping into PhD teaching for the first time. Being over prepared will help researchers answer the queries raised by students. However, one must ensure of not overwhelming the students with jargon information.

Don’t Jump to Complex Subject Concepts

Students may not understand the complex concepts taught in the lecture, unless basic concepts are explained. Researchers must take their new class by refurbing the students’ knowledge on basic concepts; this will also be beneficial for them and their PhD study.

Imparting Incorrect/False Information to Students

It is necessary to thoroughly prepare for the lecture. This will allow you to impart correct information. There are scenarios wherein a researcher is not able to answer the query raised by a student, and the researcher might give an irrelevant answer. However, it is better to be honest than giving students false information and misleading them.

Academic teaching can be a daunting process for the first time, but it really gives an impactful career growth for PhD graduates . What do you think about PhD teaching ? How did you strike a balance between research and teaching career? Let us know in the comment section below.

Useful Content

good article

thanks very much for this useful article, stay blessed.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

- AI in Academia

Disclosing the Use of Generative AI: Best practices for authors in manuscript preparation

The rapid proliferation of generative and other AI-based tools in research writing has ignited an…

Intersectionality in Academia: Dealing with diverse perspectives

Meritocracy and Diversity in Science: Increasing inclusivity in STEM education

Avoiding the AI Trap: Pitfalls of relying on ChatGPT for PhD applications

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

What is a PhD? Advice for PhD students

How long does it take to get a doctorate degree how do you get into grad school are you qualified to do a phd answers to these questions and more.

What is a PhD?

A PhD, which stands for “doctor of philosophy”, is the most advanced academic degree. It’s earned through extensive research on a specific topic, demonstrating expertise and contributing new knowledge to the field.

What does “PhD” mean?

The term “PhD” is often used as a synonym for any doctoral-level qualification. Doctorate degrees can often be split into two categories: MPhil and PhD.

An MPhil is similar to a PhD as it includes a research element (which is usually shorter and less in-depth than a PhD thesis, and often more akin to a dissertation undertaken at undergraduate or master’s level).

MPhil students focus more on interpreting existing knowledge and theory and critically evaluating other people’s work rather than producing their own research. The precise nature and definition of an MPhil can vary among institutions and countries.

A PhD, meanwhile, follows a more widely known and traditional route and requires students, often referred to as “candidates”, to produce their own work and research on a new area or topic to a high academic standard.

PhD requirements vary significantly among countries and institutions. The PhD, once completed, grants the successful candidate the title of “doctor of philosophy”, also called PhD or DPhil.

What is a professional doctorate?

A professional doctorate is a kind of degree that helps people become experts in their fields. Instead of focusing mainly on theory and research like a regular PhD, a professional doctorate is all about practical skills and knowledge.

This kind of doctorate is great for students who want to get better at their jobs in areas like teaching, healthcare, business, law or psychology. The courses and projects in these programmes are designed to tackle real problems you might face at work.

For example, you might have heard of the doctor of education (EdD), doctor of business administration (DBA), doctor of psychology (PsyD) or doctor of nursing practice (DNP). These programmes combine learning, hands-on projects and sometimes a thesis paper or essay to show you’re skilled at solving on-the-job challenges.

How long does it take to study a PhD?

The time required to complete a PhD can vary significantly based on several factors. Generally, a full-time PhD programme takes around three to six years to finish. However, it’s important to take into account individual circumstances and the nature of the research involved.

1. Full-time vs. part-time: If you’re studying full-time, dedicating most of your time to your studies, it usually takes about three to four years to complete a PhD. However, studying part-time while managing other commitments might extend the duration. Part-time PhDs can take around six to eight years, and sometimes even longer.

2. Nature of research: The complexity of your research proposal can influence the time required. Certain research questions may involve intricate experiments, extensive data collection or in-depth analysis, potentially leading to a longer completion timeline.

3. Field of study: The subject area you’re researching can also affect the necessary time. Some fields, such as sciences or engineering, might involve more hands-on work, while theoretical subjects might require more time for literature review and analysis.

4. Supervision and support: The guidance and availability of your academic supervisor can affect the pace of your research progress. Regular meetings and effective communication can help keep your studies on track.

5. Thesis writing: While the research phase is crucial, the stage of writing your thesis is equally significant. Organising and presenting your research findings in a clear and cohesive manner can take several months.

6. External commitments: Personal commitments, such as work, family or health-related factors, can influence your study time. Some students need to balance these alongside their PhD studies, potentially extending the duration.

7. External Funding: The availability of funding can also affect your study duration. Some funding might be linked to specific project timelines or research objectives.

So, although a PhD usually takes between three and six years of full-time study, with potential variations based on research complexity, enrolment as part-time or full-time, field of study and personal circumstances. It’s vital to have a realistic understanding of these factors when planning your PhD journey.

How long is a PhD in the UK?

In the UK, the length of a PhD programme typically ranges from three to four years of full-time study. As explained above, there are many factors to consider.

How long is a PhD in the US?

Similarly to the UK, in the United States, the duration of a PhD programme can vary widely depending on the field of study, research topic and individual circumstances. On average, a full-time PhD programme in the US typically takes between five and six years to complete.

Why does it take longer to study a PhD in the US?

PhD programmes generally take longer to complete in the US than in the UK due to various factors in the education systems and programme structures of each country:

1. Programme structure: UK PhD programmes often emphasise early, focused research from the first year, leading to shorter completion times. In contrast, US programmes commonly include more initial coursework in your first and second year and broader foundational training, which can extend the overall duration.

2. Course work requirements: Many US PhD programmes require a lot of course work, which can lengthen the time needed to finish. UK programmes tend to have fewer or no course work demands, allowing students to concentrate primarily on research skills.

3. Research funding: In the UK, PhD funding is often awarded with specific timeframes in mind, motivating completion of the research degree in the agreed duration. In the US, funding approaches can vary, requiring students to secure funding from multiple sources, potentially affecting their progress and completion time.

4. Teaching responsibilities: Some US PhD students take on teaching roles as part of their funding, dividing their time and potentially prolonging their studies.

5. Research approach: Differences in research methodologies and project scopes can affect the time needed for data collection, experimentation and analysis.

6. Academic culture: The US education system values a well-rounded education, including coursework and comprehensive exams. This can extend the time before full-time research begins. UK PhD programmes often prioritise independent research early on.

7. Part-time and work commitments: US PhD candidates might have more flexibility for part-time work or other commitments, which can affect research progress.

8. Dissertation requirements: US PhD programmes generally include a longer and more comprehensive dissertation, involving more chapters and a broader exploration of the research topic.

These variations in programme structures, funding models and academic cultures contribute to the differing completion times between the two countries.

What qualifications do you need for a PhD?

To be eligible for a PhD programme, certain educational qualifications are generally expected by universities. These qualifications serve as indicators of your readiness to engage in advanced research and contribute to the academic community.

First, an undergraduate or bachelor’s degree in a relevant field is typically the most common requirement. This degree provides you with a foundational understanding of the subject and introduces you to basic research methodologies. It serves as a starting point for your academic journey.

Do you need a master’s degree to get into a PhD programme?

In addition to an undergraduate degree, many PhD programmes also require candidates to hold postgraduate or master’s degrees, often in fields related to the intended PhD research. A master’s degree offers a deeper exploration of the subject matter and enhances your research skills. Possessing a master’s degree signifies a higher level of expertise and specialisation.

The combination of both undergraduate and postgraduate degrees demonstrates a solid academic background. This background is crucial before you engage in doctoral study because pursuing a PhD involves more than just knowledge; it requires advanced research abilities, critical thinking and the capacity to provide an original contribution and new insights into the chosen field of study.

While these qualifications are usually requested, there are exceptions. Some institutions offer direct-entry programmes that encompass bachelor’s, master’s and PhD degrees in a streamlined structure. This approach is often seen in scientific and engineering disciplines rather than humanities.

In exceptional cases, outstanding performance during undergraduate studies, coupled with a well-defined research proposal, might lead to direct entry into a PhD programme without requiring a master’s degree.

Admission requirements can vary between universities and programmes. Some institutions might have more flexible prerequisites, while others could have more stringent criteria. Make sure that you thoroughly research all admission requirements of the PhD programmes you’re interested in to ensure you provide the right information.

Are PhD entry requirements similar in other countries?

PhD entry requirements in Canada and Australia can be somewhat similar to those in the UK and the US, but there are also some differences. Just like in the UK and the US, having a bachelor’s degree followed by a master’s degree is a common way to qualify for a PhD in Canada and Australia. However, the exact rules can vary, such as how much research experience you need or the grades you should have.

In Canada and Australia, as in the UK and the US, international students usually need to show their English language skills through tests like IELTS or TOEFL. And, like in other places, you might need to give a research proposal to explain what you want to study for your PhD.

But remember, even though there are some similarities, each country has its own rules.

PhD diary: Preparing for a PhD Nine things to know before doing a PhD Women in STEM: undertaking PhD research in cancer Studying for a part-time PhD: the challenges and the benefits Is it possible to do a three-year PhD as an international student? Looking for PhD tips? Why not check Twitter PhD diary: Where do I begin? How to do a PhD on a budget

How much does it cost to study a PhD?

The cost of pursuing a PhD can vary significantly between international and home (domestic) students, and it depends on the country, university and programme you choose.

United Kingdom (UK)

Home students in the UK often pay lower tuition fees compared with international students. Home students might also have access to government funding or subsidised tuition rates.

International students typically pay higher tuition fees, which can vary widely depending on the university and programme. Fees can range from around £10,000 to £25,000 or more per year.

United States (US)

PhD programme costs in the US can be quite high, especially for international students. Public universities often have lower tuition rates for in-state residents compared with out-of-state residents and international students.

Private universities in the US generally have higher tuition fees, and international students might be charged higher rates than domestic students.

Canadian universities often charge higher tuition fees for international students compared with domestic students.

Some universities offer funding packages that include tuition waivers and stipends for both domestic and international doctoral students.

In Australia, domestic students (Australian citizens and permanent residents) usually pay lower tuition fees than international students.

International students in Australia might have higher tuition fees, and costs can vary based on the university and programme.

Apart from tuition fees, other aspects play a role in the overall financial consideration:

PhD studentship: Many universities offer PhD studentships that provide financial support to research students, covering both tuition fees and a stipend for living expenses.

Stipend and housing: Stipends are designed to cover living expenses. Stipend amounts can vary depending on the university and location. If you’re studying in London in the UK, stipends might be higher to account for the higher living costs in the city. Some universities also offer subsidised or affordable housing options for doctoral students.

Tuition and stipend packages: Some PhD programmes provide funding packages that include both tuition waivers and stipends. These packages are to help relieve the financial burden on students during their doctoral studies.

Research the financial support options provided by the universities you’re interested in to make an informed decision about the cost of your PhD journey.

What funding options are available for PhD candidates?

PhD candidates have various funding options available to support their studies and research journeys. Some of these options include:

PhD scholarships: Scholarships are a common form of financial aid for PhD candidates. They are awarded based on academic merit, research potential or other specific criteria. Scholarships can cover tuition fees and provide a stipend for living expenses.

Bursaries: Bursaries are another form of financial assistance offered to students, including PhD candidates, based on financial need. They can help cover tuition fees or provide additional financial support.

In the UK, specific funding options are available:

Regional consortium: Some regions have research consortiums that offer funding opportunities for doctoral candidates. These collaborations can provide financial support for research projects aligned with specific regional needs.

UK research institute: Research councils in the UK often offer stipends to PhD candidates. These stipends cover living expenses and support research work.

University-based studentship: Many UK universities offer studentships. You can read more about these above.

In the USA, there are also funding options available:

Research assistantships (RAs): Many universities offer research assistantships where PhD candidates work on research projects under the guidance of faculty members. In exchange, they receive stipends and often have their tuition waived.

Teaching assistantships (TA): Teaching assistantships involve assisting professors in teaching undergraduate courses. In return, PhD candidates receive stipends and sometimes tuition remission.

Fellowships: Fellowships are competitive awards that provide financial support for PhD candidates. They can come from universities, government agencies, private foundations and other institutions. Fellowships can cover tuition, provide stipends and offer research or travel funds.

Graduate assistantships: Graduate assistantships include a range of roles, from research and teaching to administrative support. These positions often come with stipends and sometimes include tuition benefits.

External grants and fellowships: PhD candidates can apply for grants and fellowships from external organisations and foundations that support research careers in specific fields. Examples include the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Fulbright Programme.

Employer sponsorship: In some cases, employers might sponsor employees to pursue PhDs, especially if the research aligns with the company’s interests.

You can read about the current available scholarships for international students of all education levels on our website .

What does a PhD Involve?

How does a PhD work?

A PhD includes thorough academic research and significant contributions to your chosen field of study. The timeline for completing a PhD can significantly vary based on the country, college or university you attend and the specific subject you study.

The duration of a PhD programme can vary based on factors such as the institution’s requirements and the academic discipline you’re pursuing. For instance, the timeline for a PhD in a science-related field might differ from that of a humanities discipline.

UK PhD timeline example

Looking at a typical PhD degree in a London higher education institution, we can consider this example timeline.

In the initial year of your PhD, you’ll collaborate closely with your designated academic supervisor. This collaboration involves refining and solidifying your research proposal, which lays the foundation for your entire doctoral journey.

This is also the time to establish a comprehensive plan, complete with well-defined milestones and deadlines. A crucial aspect of this year is conducting an extensive literature review, immersing yourself in existing academic works to understand the landscape of your chosen research area. It’s important to make sure that your research idea is original and distinct from prior studies.

As you begin the second year, you’ll actively collect data and gather information related to your research topic. Simultaneously, you’ll initiate the process of crafting your thesis. This involves combining your research findings and analysis into sections of your thesis document.

This is also the phase where you might have opportunities to share your research insights at academic meetings, conferences or workshops. Depending on the programme, you might even engage in teaching activities. Some PhD candidates also begin contributing to academic journals or books, showcasing their findings to a broader audience.

The third year of a PhD programme often marks the final stage of your research efforts. This is when you dedicate substantial time to writing and finalising your complete thesis. Once your thesis is completed to the highest standard, you’ll submit it for thorough evaluation.

A significant milestone in the third year is the viva voce, an oral examination where you’ll defend your thesis before a panel of experts in your field. The viva voce is an opportunity to showcase your deep understanding of your research and defend your findings.

Why should you do a PhD?

For many people, acquiring a doctorate degree is the pinnacle of academic achievement, the culmination of years of commitment to higher education.

However, the act of pursuing a PhD can be a complex, frustrating, expensive and time-consuming exercise. But with the right preparation, some sound advice and a thorough understanding of the task at hand, your years as a doctoral student can be some of the most rewarding of your life.

People choose to work towards a doctorate for many reasons. If you are looking to pursue an academic position, such as university lecturer or researcher, then a PhD is usually required.

Many people obtain a PhD as part of a partnership with an employer, particularly in scientific fields such as engineering, where their research can prove useful for companies.

In some cases, however, PhDs are simply down to an individual’s love of a subject and their desire to learn more about their field.

What are some benefits of studying a PhD?

Pursuing a PhD can have many benefits that extend beyond academic achievement, encompassing personal growth, professional advancement and meaningful contributions to knowledge.

One of the most notable benefits of a PhD is the potential for tenure in academia. Attaining tenure provides a level of job security that allows you to delve into long-term research projects and make enduring contributions to your field. It signifies a stage where you can explore innovative ideas and pursue in-depth research, fostering your academic legacy.

While not obligatory, the opportunity to collaborate on research projects with your supervisor is another valuable aspect of a PhD pursuit. These collaborations might even come with financial compensation, offering real-world experience, skill development and practical applications of your research. Engaging in such collaborations can enrich your research portfolio and refine your research methodologies.

A pivotal aspect of a PhD journey is the chance to publish your original research findings. By disseminating your work in academic journals or presenting it at conferences, you contribute to the expansion of knowledge within your field. These publications establish your expertise and reputation among peers and researchers worldwide, leaving a lasting impact.

The pursuit of a PhD can provide a unique platform to build a diverse network of colleagues, mentors and collaborators. Engaging with fellow researchers, attending conferences and participating in academic events offer opportunities to make valuable connections. This network can lead to collaborations, expose you to a spectrum of perspectives and pave the way for future research endeavours.

What is a PhD thesis? And what is a PhD viva?

A PhD thesis will be produced with help from an academic supervisor, usually one with expertise in your particular field of study. This thesis is the backbone of a PhD, and is the candidate’s opportunity to communicate their original research to others in their field (and a wider audience). PhD students also have to explain their research project and defend their thesis in front of a panel of academics. This part of the process is often the most challenging, since writing a thesis is a major part of many undergraduate or master’s degrees, but having to defend it from criticism in real time is arguably more daunting. This questioning is known as a “viva”, and examiners will pay particular attention to a PhD’s weaknesses either in terms of methodology or findings. Candidates will be expected to have a strong understanding of their subject areas and be able to justify specific elements of their research quickly and succinctly.

In rare cases, students going for a PhD may instead be awarded an MPhil if the academic standard of their work is not considered fully up to par but still strong enough to be deserving of a qualification.

Can you do a PhD part time?

Many PhD and MPhil candidates choose to pursue their qualification part time, in order to allow time to work and earn while studying. This is especially true of older students, who might be returning to academia after working for a few years.

When applying, you should always speak to the admissions team at your university to ensure this is possible and then continue to work with your supervisor to balance all your commitments.

Can I do a PhD through distance learning?

This is something else that you will need to check with your university. Some institutions offer this option, depending on the nature of your research.

You will need to be clear how many times you will need to travel to your university to meet with your supervisor throughout your PhD.

Your PhD supervisor

Choosing the right PhD supervisor is essential if you want to get the most out of your PhD. Do your research into the faculty at the institution and ensure that you meet with your proposed supervisor (either virtually or in person) before fully committing.

You need to know that not only do they have the right expertise and understanding of your research but also that your personalities won’t clash throughout your PhD.

Remember, to complete your PhD, you will need a strong support network in place, and your supervisor is a key part of that network.

Coping with PhD stress

If you do decide to embark on a doctorate, you may well encounter stress and anxiety. The work involved is often carried out alone, the hours can be long and many students can suffer from the pressure they feel is on their shoulders.

Ensuring that you check in regularly with your emotions and your workload is crucial to avoid burnout. If you have other commitments, such as a job or a family, then learning to balance these can feel overwhelming at times.

Give yourself regular breaks, speak to your supervisor and ensure that you know what university resources and support systems are available to you in case you need to access them.

Post-doctorate: what happens after you finish your PhD?

Many PhD graduates pursue a career in academia, while others will work in industry. Some might take time out, if they can afford to, to recover from the efforts of PhD study.

Whatever you choose to do, undertaking a PhD is a huge task that can open up a range of doors professionally. Just remember to take some time out to celebrate your achievement.

How does a PhD affect salary and earning potential?

How much does a professor with a PhD make a year?

Professors with PhDs can earn different amounts depending on where they work and their experience. In the UK, a professor might make around £50,000 to £100,000 or more each year. In the US, it's between about $60,000 and $200,000 or even higher. The exact salary depends on things like the place they work, if they have tenure, and what they teach.

How much does a PhD add to salary?

Having a PhD can make your salary higher than if you had a lower degree. But exactly how much more you earn can change. On average, people with PhDs earn more than those with bachelor’s or master’s degrees. The increase in salary is influenced by many things, such as the job you do, where you work and what field you’re in.

In fields such as research, healthcare, technology and finance, your knowledge and skills from your PhD can potentially help you secure a higher salary position.

In the end, having a PhD can boost your earning potential and open doors to well-paying jobs, including professorships and special roles in different areas. But the exact effect on your salary is influenced by many things, so ensure you weigh the cost against the benefit.

How to choose a PhD programme?

Choosing a PhD programme involves defining your research interest, researching supervisors and programme reputation, evaluating funding options, reviewing programme structure, considering available resources, assessing networking opportunities, factoring in location and career outcomes, visiting the campus if possible and trusting your instincts.

How can I find available PhD programmes?

You can find available PhD programmes by visiting university websites, using online directories such as “FindAPhD”, checking professional associations, networking with professors and students, following universities on social media, attending career fairs and conferences, contacting universities directly and exploring research institutes’ websites.

How to apply for a PhD programme?

To apply for a PhD programme:

Research and select universities aligned with your interests.

Contact potential supervisors, sharing your proposal, CV and references.

Prepare application materials: research proposal, CV, recommendation letters and a writing sample.

Ensure you meet academic and language-proficiency requirements.

Complete an online application through the university’s portal.

Pay any required application fees.

Write a statement of purpose explaining your motivations.

Provide official transcripts of your academic records.

Submit standardised test scores if needed.

Some programmes may require an interview.

The admissions committee reviews applications and decides.

Apply for scholarships or assistantships.

Upon acceptance, review and respond to the offer letter.

Plan travel, accommodation and logistics accordingly.

Remember to research and follow each university’s specific application guidelines and deadlines.

How to apply for a PhD as an international student?

Many stages of the PhD application process are the same for international students as domestic students. However, there are sometimes some additional steps:

International students should apply for a student visa.

Take language proficiency tests such as TOEFL or IELTS if required.

Provide certificates if needed to validate your previous degrees.

Show evidence of sufficient funds for tuition and living expenses.

Check if you need health insurance for your chosen destination.

Translate and authenticate academic transcripts if necessary.

Attend orientation sessions for cultural adaptation.

Apply for university housing or explore off-campus options.

Familiarise yourself with international student support services.

Ben Osborne, the postgraduate student recruitment manager at the University of Sussex explains in detail how to apply for a PhD in the UK .

Giulia Evolvi, a lecturer in media and communication at Erasmus University, Rotterdam explains how to apply for a PhD in the US .

Finally, Samiul Hossain explores the question Is it possible to do a three-year PhD as an international student?

Q. What is a PhD? A. A PhD is the highest level of academic degree awarded by universities, involving in-depth research and a substantial thesis.

Q. What does “PhD” mean? A. “PhD” stands for doctor of philosophy, recognising expertise in a field.

Q. What is a professional doctorate? A. A professional doctorate emphasises practical application in fields such as education or healthcare.

Q. How long does it take to study a PhD? A. It takes between three and six years to study a full-time PhD programme.

Q. How long is a PhD in the UK? A. It takes around three to four years to study a full-time UK PhD.

Q. How long is a PhD in the US? A. It takes approximately five to six years to complete a full-time US PhD.

Q. Why does it take longer to study a PhD in the US? A. US programmes often include more course work and broader training.

Q. What qualifications do you need for a PhD? A. You usually need an undergraduate degree as a minimum requirement, although a master’s might be preferred.

Q. Do you need a master’s degree to get into a PhD programme? A. Master’s degrees are preferred but not always required.

Q. Are PhD entry requirements similar in other countries? A. Entry requirements are similar in many countries, but there may be additional requirements. Make sure to check the university website for specific details.

Q. How much does it cost to study a PhD? A. The cost of PhD programmes vary by country and university.

Q. What funding options are available for PhD candidates? A. Scholarships, assistantships, fellowships, grants, stipends are all funding options for PhD candidates.

Q. What does a PhD involve? A. PhDs involve research, seminars, thesis, literature review, data analysis and a PhD viva.

Q. Why should you do a PhD? A. There are many reasons to study a PhD including personal growth, research skills, contributions to academia and professional development.

Q. What are some benefits of studying a PhD? A. Benefits of graduating with a PhD include achieving tenure, collaborations with colleagues, publication of your work, and networking opportunities.

Q. What is a PhD thesis? A. A PhD thesis is a comprehensive document that showcases the original research conducted by a PhD candidate.

Q. What is a PhD viva? A. A PhD viva, also known as a viva voce or oral examination, is the final evaluation of a PhD candidate’s research and thesis where the panel asks questions, engages in discussions and assesses the depth of the candidate’s understanding and expertise.

Q. Can you do a PhD part-time? A. Yes, part-time options are available for PhDs.

Q. Can I do a PhD through distance learning? A. Some universities offer online PhDs; you can find out more on their websites.

Q. How to choose a PhD programme? A. You can find PhD programmes through research, by contacting faculty, checking resources and considering location.

Q. How can I find available PhD programme? A. You can find available PhD programmes on university sites, through directories and by networking.

Q. How to apply for a PhD programme A. To apply for a PhD programme, research suitable universities and programmes, get in touch with potential supervisors, gather required documents like transcripts and reference letters, complete the online application, pay any necessary fees and submit a statement of purpose and research proposal. If needed, meet language-proficiency criteria and attend interviews. After acceptance, explore funding choices, confirm your spot and get ready for the programme’s start.

Q. How to apply for a PhD as an international student A. To apply for a PhD as an international student, follow similar steps to domestic students, but you need to include securing a student visa and passing language requirements.

Q. What is a PhD dropout rate? A. The dropout rate from PhDs varies but is approximately 30-40 per cent.

Q. How does a PhD affect salary and earning potential? A. A PhD can boost earning potential, especially in research, technology, healthcare and academia. Impact varies by job, industry and location. Experience, skills and demand also influence salary.

Q. How to address a person with a PhD? A. When addressing someone with a PhD, it’s respectful to use “Dr”, followed by their last name, whether they have a PhD in an academic field or a professional doctorate. For instance, “Dr. Smith”.

Q. Is there a difference between a PhD and a doctorate? A. The terms “PhD” and “doctorate” are often used interchangeably, though a PhD is a specific type of doctorate focused on original research. A doctorate can refer more broadly to any doctoral-level degree, including professional doctorates with practical applications.

Q. What is the difference between a PhD and an MD? A. A PhD is a doctor of philosophy, awarded for academic research, while an MD is a doctor of medicine, focusing on medical practice. They lead to different career paths and involve distinct areas of study.

Q. What is the difference between a PhD and a professional doctorate? A. A PhD is an academic research-focused degree, while a professional doctorate emphasises applying research to practical fields such as education or business. PhDs often involve original research, while professional doctorates focus on real-world application.

Q. What is the difference between UK and US PhDs? A. The difference between UK and US PhDs lies mainly in structure and duration. UK PhDs often have shorter durations and a stronger emphasis on independent research from an early stage. US PhDs typically include more initial coursework and broader foundational training before full-time research begins.

Q. What is the difference between a PhD student and a candidate? A. A PhD student is actively studying and researching in a doctoral programme, while a PhD candidate has completed programme requirements except for the dissertation and is close to completion.

Q. What’s the difference between a PhD and an EdD? A. A PhD and an EdD (doctor of education) differ in focus. A PhD emphasises research and academic contributions, while an EdD focuses on applying research to practical educational issues.

Q. What’s the difference between a PhD and a DBA? A. A PhD and a DBA (doctor of business administration) differ in purpose. A PhD emphasises theoretical research and academia, while a DBA is practice-oriented, aimed at solving real business problems.

Q. What’s the difference between a PhD and a PsyD? A. A PhD and a PsyD (doctor of psychology) differ in emphasis. A PhD focuses on research and academia, while a PsyD emphasises clinical practice and applying psychological knowledge.

Q. What’s the difference between a PhD and an LLD? A. A PhD and an LLD (doctor of laws or Legum doctor) are distinct. A PhD is awarded in various disciplines, while an LLD is usually an honorary degree for significant contributions to law.

Q. What’s the difference between a PhD and an MD-PhD? A. A PhD and an MD-PhD differ. An MD-PhD is a dual degree combining medical training (MD) with research training (PhD).

Q. What is the Cambridge PhD? A. A Cambridge PhD involves original research guided by a supervisor, resulting in a thesis. It’s offered at the University of Cambridge .

Q. What is the Oxford DPhil? A. An Oxford DPhil is equivalent to a PhD and involves independent research leading to a thesis. The term “DPhil” is unique to the University of Oxford .

Q. What is the PhD programme acceptance rate? A. PhD acceptance rates vary by university, field and competition. Prestigious universities and competitive fields often have lower acceptance rates.

Q. What is a PhD supervisor? A. A PhD supervisor guides and supports a student’s research journey, providing expertise and feedback.

Q. What is a PhD panel? A. A PhD panel evaluates a candidate’s research, thesis and oral defence. It consists of experts in the field.

Q. What is a PhD stipend? A. A PhD stipend is a regular payment supporting living expenses during research, often tied to teaching or research assistant roles.

Q. What is a PhD progression assessment? A. A PhD progression assessment evaluates a student’s progress, often confirming their continuation in the programme.

Q. What is a PhD defence? A. A PhD defence, or viva, is the final oral examination where a candidate presents and defends their research findings and thesis before experts.

You may also like

.css-185owts{overflow:hidden;max-height:54px;text-indent:0px;} Pursuing a PhD in neuroscience

Luis Humberto Eudave Ramos

Why study a PhD in English literature?

John Francis Davies

8 habits to help you get through your PhD

Shabana Khan

Register free and enjoy extra benefits

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 14 October 2021

Do we achieve anything by teaching research integrity to starting PhD students?

- Shila Abdi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3054-6971 1 ,

- Steffen Fieuws 1 ,

- Benoit Nemery ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0571-4689 1 &

- Kris Dierickx 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 232 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

2262 Accesses

8 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

Education of young researchers has been proposed as a way to promote research integrity. However, the effectiveness of research integrity education on PhD students is unknown. In a longitudinal design, we surveyed over 1000 starting PhD students from various disciplines regarding knowledge, attitude and behaviour before, immediately after and 3 months after a compulsory 3-h course given by a panel of experts. Compared with a control group who did not follow the course, the course recipients showed significant (multivariate analysis) but modest improvements in knowledge and attitude scores immediately after the course, but not after 3 months; a prolonged impact was apparent regarding behaviour. Moreover, the course spurred 93% of PhD students to have conversations about research integrity and 79% declared applying the content of the course. Among other interventions, formal education in research integrity may contribute to foster a climate of research integrity in academia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Refining the impact of genetic evidence on clinical success

Impact of artificial intelligence on human loss in decision making, laziness and safety in education

Artificial intelligence and illusions of understanding in scientific research

Introduction.

In 2005, a notorious Nature article titled “Scientists behaving badly” revealed that scientists admitted to a wide range of activities that compromise the integrity of science (Martinson et al. 2005 ). This sobering discovery and other evidence have led various institutions to take a range of initiatives, such as developing codes of conduct for responsible research and organising educational activities to promote research integrity (Fanelli, 2009 ; Mejlgaard et al. 2020 ). However, systematic evaluations of the effectiveness of research integrity course are still scare (Committee on Responsible Science et al. 2017 ).

Since 2014, attending a university-wide 3-h session of lectures on research integrity has been a mandatory milestone for starting PhD students at the KU Leuven, one of the leading research-intensive universities in Europe (“ Central lecture Research Integrity for starting PhD researchers ”). In brief, the 3-h course on research integrity is given, in English, by a panel of five lecturers who cover general ethics in research, data management, plagiarism, conflicts of interest and publication ethics. The same course is organised four times a year in lecture halls with 200–400 first-year PhD students from all disciplinary fields of the university.

To evaluate the impact of this course, hereafter called the intervention, we surveyed all PhD students attending the course over one academic year. In a longitudinal study design, we assessed individual knowledge, attitude, and behaviour in relation to the teaching content of the educational programme; we administered the same paper questionnaires to more than 1000 PhD students immediately before and immediately after the course, and we also invited participants to reply to a similar electronic questionnaire (plus other questions) 3 months later. The questionnaires (see supplementary material 1 and 2 ) were based on previous surveys of research integrity (Bouter et al. 2016 ; Godecharle et al. 2018 ; Martinson et al. 2005 ). To control for time effects, we followed the same procedures with a control group consisting of Master students from different disciplines; they were enroled in the survey through one of their normal courses and they received similar questionnaires and follow-up procedures as the PhD students. For the statistical analysis, we used multivariate linear models for longitudinal measurements with the null hypotheses being that no changes occurred in scores of knowledge, attitude or behaviour compared to baseline.

Response rate and participants’ characteristics

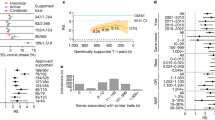

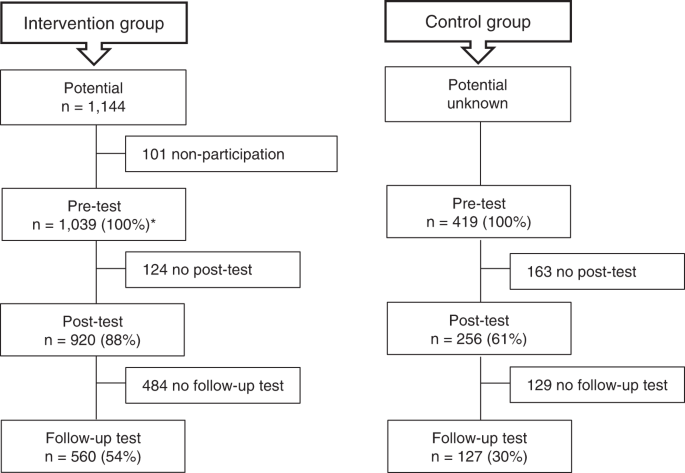

The total number of PhD students present during the courses were based on the number of participants scanning in with their KU Leuven badge upon entry and exit of the lecture hall. The total number of eligible Master students was not known, since their attendance was not registered. Of the 1044 PhD students who participated in the study by returning completed questionnaires, 5 participants returned only the post-test. As shown in the flowchart (Fig. 1 ), 1039 PhD students completed the pre-test, 920 completed the post-test and 560 filled out the follow-up test. Of the 419 control participants, 30% completed all three measurements.

Participants are PhD students in the intervention group and Master students in the control group. *The total number of participants in the intervention group is 1044. Five participants did not fill out the pre-test.

The baseline characteristics of the study populations are shown in Table 1 . The majority of PhD students were effectively in their first year of the PhD programme, most had not previously attended a course or workshop on research integrity, and the university’s broad disciplinary fields were well represented. Supplementary materials 3 , 4 and 5 show the estimates with 95% confidence intervals for item-level results for knowledge, attitude and behaviour.

Appraising the research integrity course

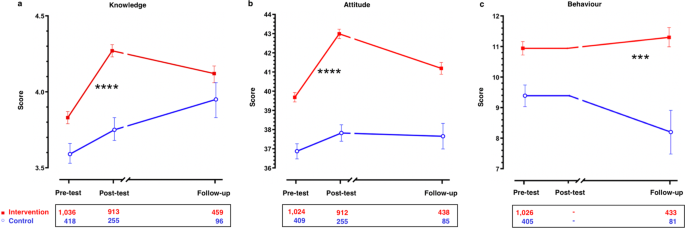

Significant increases in knowledge scores at the post-test compared to pre-test were observed in both the intervention and control groups, but the increase was significantly higher in the intervention group (pre-test intervention = 3.83, post-test intervention = 4.27) than in the control group (pre-test control = 3.59, post-test control = 3.75) (Fig. 2a ). At the follow-up, the knowledge scores were also higher than the initial scores in both the intervention and control groups, but the changes did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 2 ).

Pre-test indicates scores immediately prior to a 3-h course on research integrity (intervention) or another course (controls). Post-test indicates scores immediately after the course. Follow-up indicates scores after 3 months. a Sum of six knowledge items (minimum 0, maximum 6). b Sum of ten attitudes items (minimum 10, maximum 50). c Sum of five behaviour items (minimum 5, maximum 15), behaviour questions were not asked at post-test. Data are shown as means with 95% confidence intervals. *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 for the differences in change with respect to pre-test values between both groups, as determined by multivariate linear models for longitudinal measurements, using a direct likelihood approach. Numbers of respondents are indicated below the graphs and may differ from those shown in Fig. 1 because of missing data. For details, see Table 2 .

Significant increases were again observed for attitude scores in both groups, at the post-test and at the follow-up test, with only the post-test increase being significantly higher in the intervention group (pre-test intervention = 39.68, post-test intervention = 42.99) than in the control group (pre-test control = 36.87, post-test control = 37.82) (Fig. 2b ) (Table 2 ).

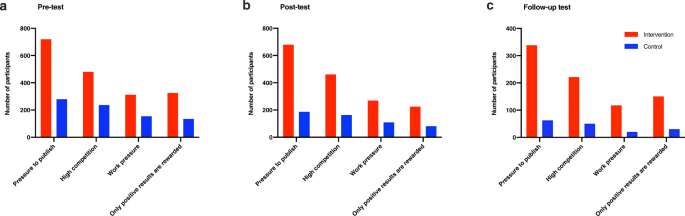

At the follow-up, participants from both groups put forward pressure to publish , high competition and only positive results are rewarded , as the three most important reasons for scientists to misbehave (Fig. 3 ).

Pre-test indicates responses immediately prior to the course on research integrity ( a ). Post-test indicates responses immediately after the course ( b ). Follow-up indicates responses after 3 months ( c ). Data are shown as number of participants. Participants are PhD students in the intervention group and Master students in the control group.

Participants filled out the behaviour questions at the pre-test and follow-up test. The analysis of behaviour items on a four-point Likert scale, e.g. When I needed guidance on research integrity, I went to my supervisor, showed a significant but small improvement towards better behaviour in the intervention group (pre-test intervention = 10.94, follow-up intervention = 11.30), compared to a significant decrease in the control group (pre-test control = 9.39, follow-up control = 8.20) (Fig. 2c ). However, when we analysed behaviour through yes/no items, e.g. I made a data management plan , there was a significant increase in both groups, unlike when using the Likert scale, the changes did not differ (Table 2 ).

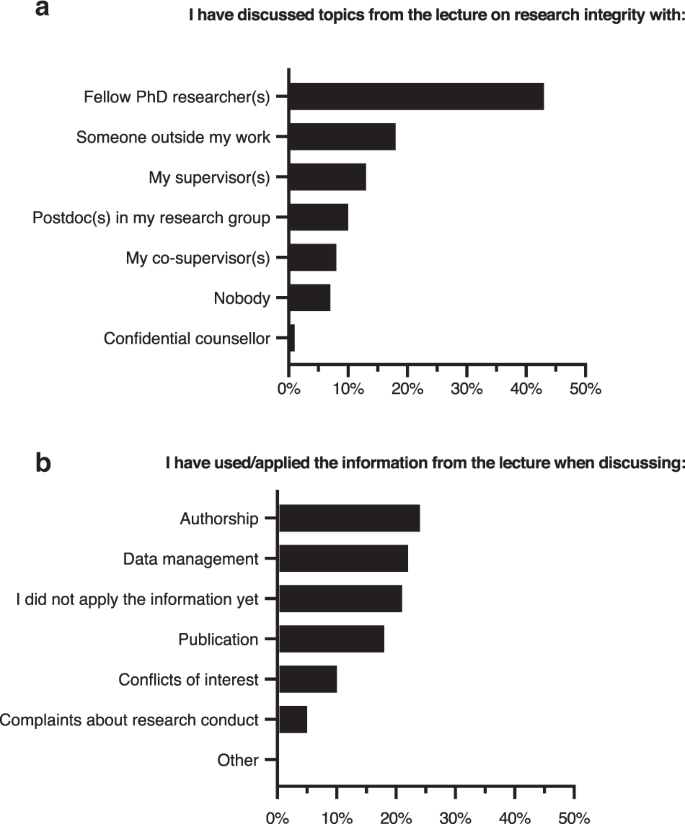

Raising awareness: conversations about research integrity

At the follow-up test, participants from the intervention group were additionally asked to indicate whether they had discussed topics from the lecture on research integrity with others. The majority of participants (93%) reported having had conversations about research integrity, mainly with fellow PhD students (43%), someone close to them outside their work environment (18%) or their supervisor(s) (13%) (Fig. 4a ). The majority of the participants (79%) also indicated that they had applied/used the information received during the course, mostly regarding authorship (24%), data management (22%) and publication (18%) (Fig. 4b ).

a Number and percentage of PhD students that indicated whether they had discussed topics from research integrity course with others. b Number and percentage of PhD students that indicated that they had applied/used the information received during the course. Participants were asked to check all that apply from a list of predefined options, including option “other”.

Ours is not the first attempt to appraise education on research integrity, but it is the first empirical study evaluating the immediate impact, as well as its retention over 3 months in a large sample of PhD students from biomedical sciences, natural sciences, as well as social sciences/humanities.

A positive outcome of our study was the significant though modest improvement of PhD students’ scores on knowledge and attitude, and the prolonged impact for some behavioural items. In addition, we achieved a potentially important—though hard to quantify—outcome, in that the great majority of the participants indicated that the lecture had led to discussing research integrity issues and even applying the content of the course in their daily research practice. Of note, the extent to which research integrity was reportedly discussed with the PhD supervisors proved rather low, as found by others (Langlais and Bent, 2014 ).

A unique and critically important methodologic feature of the present study is that we included a control group who did not receive the intervention. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 2 , post-test results improved slightly, even in the absence of the intervention, thus suggesting the occurrence of “test effects” (Marsden and Torgerson, 2012 ). Admittedly, the controls did not consist of a randomised group of PhD students who did not receive the intervention, because the research integrity lecture was mandatory.

Our study has several other strengths compared to previous research (Watts et al. 2017 ). The existing literature on the impact of research integrity instructions focused on students from a particular disciplinary field (Antes et al. 2010 ; Henslee et al. 2017 ), did not include longitudinal data (Antes et al. 2010 ), used a meta-analytic approach to evaluate instruction (Watts et al. 2017 ), or concerned only a limited number of students (Langlais and Bent, 2018 ). In contrast, we surveyed a large number of participants from all academic disciplines and our study population was also internationally highly diverse, since 43% of our PhD students had obtained their master’s degrees outside Belgium (at KU Leuven, the language used in research is largely English). The high number of participants and their diversity in terms of research fields and geographical origin are features favouring generalisability of our findings beyond the local context. In addition, the content of the KU Leuven research integrity course is in line with that of research integrity programmes offered at other institutions (Abdi et al. 2021 ; Pizzolato et al. 2020 ).

A recent meta-analysis on the impact of ethics instruction based on various evaluation criteria demonstrated “sizable” positive effects to course participants (Watts et al. 2017 ), although the effect sizes ranged from −0.01 (no effect) to 0.79 (large effect). However, in that meta-analysis, a broad range of different teaching and training methods were considered with regard to ethics instructions in the sciences, whereas the objective of the present study was to evaluate quantitatively the impact of a well-defined educational intervention, consisting of a single 3-h session of lectures on research integrity given in a large auditorium.

We did not observe a prolonged effect for knowledge and attitude. This may not be surprising since it is well-known that traditional lecture-based teaching contributes little to long-term knowledge retention. It has been demonstrated that students retain less information from traditional lecturing compared with active learning methods (Freeman et al. 2014 ; Ramsden, 2003 ; Ruiz-Primo et al. 2011 ). Another possible explanation for the absence of a persistent improvement in knowledge and attitude in our study is the greater drop-out in the control group. These more motivated participants were possibly not representative for the whole control group, thus masking a possible difference with the intervention group.

Some limitations should be acknowledged. First, since the course was intended to involve PhD students from all disciplinary fields, issues focussing on quantitative research and statistical analysis, such as p-hacking and HARKing were not addressed in the course and therefore also not addressed in the questionnaire. Similarly, because of the limited research experience of starting PhD students, we did not include issues such as retraction, citation bias, publication bias or pre-registration.

Second, the proportion of PhD students from the natural science may appear high, but this also reflects the composition of PhD students in our university (44% of all PhD students come from natural sciences).

Third, participants were not randomised, and the intervention and control group originated from different populations (PhD and Master students, respectively).

Lastly, the drop-out percentages after 3-month timepoints may appear high. We had hoped that the subjects with a follow-up measurement would be similar to those without a follow-up information. However, in general, the mean scores at pre-test proved slightly higher for participants with complete follow-up than the mean scores of dropouts [for knowledge (3.68 vs 3.86), for attitude [38.46 vs 39.36], and behaviour yes/no (1.63 vs 1.82); no changes in behaviour Likert scale (10.63 vs 10.36)]. We trust that these minimal differences did not materially reflect our outcome.

One could criticise that our empirical study simply demonstrated what was to be expected, namely that simply attending lectures for 3 h is unlikely to have a lasting substantial impact on knowledge, attitude, and behaviour about research integrity. However, although the scores of these outcome variables showed little or no improvement 3 months after the intervention, our study did reveal that the single intervention had succeeded in placing research integrity on the agenda of the participants, as evidenced by the fact that more than 90% of respondents reported having talked about the concepts addressed during the course, and more than 70% even indicated that they had applied some of these concepts. These admittedly less tangible outcomes suggest that the content of the lectures had moved beyond the lecture hall and that the intervention thus might have lastingly influenced the students’ actual practice of research. In other words, we propose that the conversations spurred by the course may have engendered a greater—hopefully beneficial—effect on the integrity of research than the instruction itself. This is why the research integrity training at the KU Leuven also involves interactive workshops for small groups of more advanced PhD students and, more recently, also for newly appointed PhD supervisors. We hope that this comprehensive approach will contribute to fostering a culture of research integrity, which we consider, in agreement with others (Martinson et al. 2005 ; Mejlgaard et al. 2020 ; Peiffer et al. 2008 ; Lerouge and Hol, 2020 ), to be most influential for shaping researchers’ behaviour.

Questionnaire development

The questionnaires used for the study are included in a Supplement. They were all in English, which is widely used for research at KU Leuven. First, we developed a 36-item questionnaire on knowledge, attitude and behaviour in research integrity and misconduct based on a list of 16 research misbehaviours, 22 actions of research misconduct, and a comprehensive list of 60 major and minor research misbehaviours, as described in the literature (Bouter et al. 2016 ; Godecharle et al. 2018 ; Martinson et al. 2005 ). We added questions on research integrity, such as I made a data management plan (Behaviour item), Research integrity training for junior researchers should be mandatory (Attitude item). We also adapted some questions to the target population of starting PhD students, who typically have limited experience with certain issues, such as retractions.

Second, we validated the content of the questions by consulting six independent experts: two lecturers of the research integrity course, two research integrity officers, one expert in methodology and one person holding a PhD on the topic of research integrity. We asked them to rate the relevance of each item on a four-point Likert scale ranging from ‘1 = not relevant’ to ‘4 = highly relevant’ . We used a multirater kappa coefficient of agreement (Polit et al. 2007 ) to calculate agreement among the six experts for each item and applied the evaluation criteria for kappa as outlined by Cicchetti ( 1984 ) and Fleiss ( 1971 ). As a consequence, we removed seven items, thus resulting finally in 29 items (see supplementary material 1 and supplementary material 2 ): six multiple-choice knowledge items, ten attitude items on a five-point Likert scale, one attitude top 3 ranking item, seven behaviour items on a four-point Likert scale and five behaviour yes/no items. We determined the correct answers for each knowledge item.

Finally, we conducted a pilot study with ten members of the Department of Public Health and Primary Care to test the user-friendliness and layout of the survey.

Intervention and survey procedures

The intervention group consisted of PhD students from all doctoral schools of the university who had been invited to attend a mandatory course on research integrity during their first year of research. As in other years, the same course was offered four times (November 2018, January, March and May 2019) and it consisted of successive lectures (with powerpoint slides, including some interactive questions via Poll Everywhere) given over 3 h by a panel of the same five lecturers from different disciplines (including two of the co-authors) to mixed groups of 200–400 PhD researchers from biomedical sciences, natural sciences, and social sciences/humanities. All attendees were asked to complete a paper-based survey containing knowledge, attitude, and behaviour items immediately before the first lecture started. This pre-test was printed on yellow pages each containing a six-digit-code. The filled pre-test questionnaires were collected before starting the lecture. Immediately after the 3-h course, before leaving the lecture hall, the PhD students were asked to fill out the post-test survey printed on pink pages, with the same six-digit-code to allow a linkage of individual pre- and post-test responses. The demographic characteristics of the participants and behaviour items were filled only once, at the pre-test. Three months after the research integrity course, participants who had filled the optional entry for their own e-mail, received an invitation with a link to the online follow-up test using LimeSurvey Version 2.00, where they were asked to reply to a questionnaire that was nearly identical to the pre-test questionnaire, plus five additional items (see supplementary material 1 ). For the online follow-up survey, we sent up to three reminders.

An identical procedure was applied to the respondents from the control group which consisted of Master students. It was not possible to have a control group consisting of PhD students because the research integrity course was a mandatory milestone for all starting PhD students from the university. So, we distributed the paper-based pre-test and post-test questionnaires to KU Leuven Master students following similar disciplines as the PhD students. Because it was not possible to find a course of 3 h, the post-test in the control group was taken after 4 h of one or a series of their normal lectures unrelated to research integrity. We slightly adapted the questionnaire to students at Master level ( e.g. Have you obtained your Bachelor’s degree in Belgium? ) (see supplementary material 2 ). These control students were included in February, March, and April 2019.

The study protocol received a favourable advice from the Social and Societal Ethics Committee of the University of Leuven (G-2018 10 1350). Each survey form had to be signed for consent (see supplementary material 1 and supplementary material 2 ). No coercion was exercised, and no incentives were given to participate in the survey. All participants were assured confidentiality.

Data analysis

The pre-test and post-test data were entered into Excel sheets and then, together with the online follow-up data, imported and analysed using SAS software version 9.4. Correct data entry was checked by an independent person. A multivariate linear model for longitudinal measurements (with an unstructured covariance matrix for the timepoints) was used to evaluate whether changes in the scores for knowledge, attitude and behaviour differed between the intervention and control group. By the use of a direct likelihood approach, all subjects with a score on at least one of the timepoints were included in the analysis. For the binary items, a binary logistic model with generalised estimating equations was used. All reported p values are two-sided.

The analysis consisted of assessing changes in scores of knowledge, attitude and behaviour compared to pre-test, at post-test and follow-up. The scores 1–5 for attitude items were reversed for the first eight attitude items (a higher score on attitude implied a more positive attitude towards research integrity). In the follow-up test, we added five additional items (see Supplementary material 1 ).

We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding one knowledge item (Who owns data collected during your PhD trajectory?) because we had not realised that the university had no explicit policy regarding ownership of data, but this sensitivity analysis did not alter the results. In addition, we excluded two behavioural items from the statistical analyses: one item was unrelated to PhD students’ own behaviour (I was denied co-authorship on a manuscript to which I had contributed substantially) ; and one item was not listed in the follow-up questionnaire (I have discussed issues related to research integrity and misconduct with fellow PhD students outside this research integrity course) .

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise research participants’ privacy and consent. However, they are available from the corresponding author [SA] upon reasonable request.

Abdi S, Pizzolato D, Nemery B, Dierickx K (2021) Educating PhD students in research integrity in Europe. Sci Eng Ethics 27:5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00290-0

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Antes AL, Wang X, Mumford MD, Brown RP, Connelly S, Devenport LD (2010) Evaluating the effects that existing instruction on responsible conduct of research has on ethical decision making. Acad Med 85:519–526. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181cd1cc5

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bouter LM, Tijdink J, Axelsen N, Martinson BC, ter Riet G (2016) Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Res Integr Peer Rev 1:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5

Central lecture research integrity for starting PhD researchers (3h lecture). https://www.kuleuven.be/english/research/integrity/training/phdlecture . Accessed 2 Nov 2020.

Cicchetti DV (1984) On a model for assessing the security of infantile attachment: issues of observer reliability and validity. Behav. Brain Sci 7:149–150. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00026558

Article Google Scholar

Committee on Responsible Science, Committee on Science, Engineering, Medicine, and Public Policy, Policy and Global Affairs, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017) Fostering integrity in research. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 10.17226/21896

Google Scholar

Fanelli D (2009) How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS ONE 4:e5738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005738

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fleiss JL (1971) Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol. Bull. 76:378–382. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031619

Freeman S, Eddy SL, McDonough M, Smith MK, Okoroafor N, Jordt H, Wenderoth MP (2014) Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:8410–8415. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Godecharle S, Fieuws S, Nemery B, Dierickx K (2018) Scientists still behaving badly? A survey within industry and universities. Sci Eng Ethics 24:1697–1717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9957-4

Henslee AM, Murray SL, Olbricht GR, Ludlow DK, Hays ME, Nelson HM (2017) Assessing freshman engineering students’ understanding of ethical behavior. Sci Eng Ethics 23:287–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9749-2

Langlais PJ, Bent BJ (2018) Effects of training and environment on graduate students’ self-rated knowledge and judgments of responsible research behavior. Ethics Behav 28:133–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1260014

Langlais PJ, Bent BJ (2014) Individual and organizational predictors of the ethicality of graduate students’ responses to research integrity issues. Sci Eng Ethics 20:897–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-013-9471-2

Lerouge I, Hol A (2020) Towards a research integrity culture at universities: from recommendations to implementation. https://www.leru.org/publications/towards-a-research-integrity-culture-at-universities-from-recommendations-to-implementation . Accessed 27 Nov 2020.

Marsden E, Torgerson CJ (2012) Single group, pre- and post-test research designs: some methodological concerns. Oxf Rev Educ 38:583–616

Martinson BC, Anderson MS, de Vries R (2005) Scientists behaving badly. Nature 435:737–738. https://doi.org/10.1038/435737a

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Mejlgaard N, Bouter LM, Gaskell G, Kavouras P, Allum N, Bendtsen A-K, Charitidis CA, Claesen N, Dierickx K, Domaradzka A, Reyes Elizondo A, Foeger N, Hiney M, Kaltenbrunner W, Labib K, Marušić A, Sørensen MP, Ravn T, Ščepanović R, Tijdink JK, Veltri GA (2020) Research integrity: nine ways to move from talk to walk. Nature 586:358–360. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02847-8

Peiffer AM, Laurienti PJ, Hugenschmidt CE (2008) Fostering a culture of responsible lab conduct. Science 322:1186–1186. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.322.5905.1186b

Pizzolato D, Abdi S, Dierickx K (2020) Collecting and characterizing existing and freely accessible research integrity educational resources. Account Res 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2020.1736571

Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV (2007) Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health 30:459–467. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20199

Ramsden P (2003) Learning to teach in higher education. Routledge London.

Ruiz-Primo MA, Briggs D, Iverson H, Talbot R, Shepard LA (2011) Impact of undergraduate science course innovations on learning. Science 331:1269–1270

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Watts LL, Medeiros KE, Mulhearn TJ, Steele LM, Connelly S, Mumford MD (2017) Are ethics training programs improving? A meta-analytic review of past and present ethics instruction in the sciences. Ethics Behav 27:351–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1182025

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Tamarinde Haven and Fenneke Blom for their contribution to the development of the questionnaire, and Annelies Van Tongelen for her assistance on the correct research data entry into the database.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Public Health and Primary Care, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Shila Abdi, Steffen Fieuws, Benoit Nemery & Kris Dierickx

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shila Abdi .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

BN and KD are involved in educating research integrity at the KU Leuven, including by being lecturers for the course under study. This research project was funded by the Internal Funds KU Leuven C24/15/032 but the institution had no role in designing, performing, or interpreting the findings of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary material 1,2, 3, 4 and 5, rights and permissions.