How to Write the Analysis Section of My Research Paper

How to Write a Technical Essay

Data collection is only the beginning of the research paper writing process. Writing up the analysis is the bulk of the project. As Purdue University’s Online Writing Lab notes, analysis is a useful tool for investigating content you find in various print and other sources, like journals and video media.

Locate and collect documents. Make multiple photocopies of all relevant print materials. Label and store these in a way that provides easy access. Conduct your analysis.

Create a heading for the analysis section of your paper. Specify the criteria you looked for in the data. For instance, a research paper analyzing the possibility of life on other planets may look for the weight of evidence supporting a particular theory, or the scientific validity of particular publications.

Write about the patterns you found, and note the number of instances a particular idea emerged during analysis. For example, an analysis of Native American cultures may look for similarities between spiritual beliefs, gender roles or agricultural techniques. Researchers frequently repeat the process to find patterns that were missed during the first analysis. You can also write about your comparative analysis, if you did one. It is common to ask a colleague to perform the process and compare their findings with yours.

Summarize your analysis in a paragraph or two. Write the transition for the conclusions section of your paper.

- Use compare and contrast language. Indicate where there are similarities and differences in the data through the use of phrases like ''in contrast'' and ''similarly.''

Related Articles

How to do flow proofs, how to write a rebuttal speech.

How to Do a Concept Analysis Paper for Nursing

How to Do In-Text Citations in a Research Paper

How to Write a Seminar Paper

How to Make a Rough Draft on Science Projects

How to Write a Dissertation Summary

How to Start a Good Book Report

- Purdue University Online Writing Lab - Analysis

Adam Simpson is an author and blogger who started writing professionally in 2006 and has written for OneStopEnglish and other Web sites. He has chapters in the volumes "Teaching and learning vocabulary in another language" and "Educational technology in the Arabian gulf," among others. Simpson attended the University of Central Lancashire where he earned a B.A. in international management.

Find what you need to study

Academic Paper: Discussion and Analysis

5 min read • march 10, 2023

Dylan Black

Introduction

After presenting your data and results to readers, you have one final step before you can finally wrap up your paper and write a conclusion: analyzing your data! This is the big part of your paper that finally takes all the stuff you've been talking about - your method, the data you collected, the information presented in your literature review - and uses it to make a point!

The major question to be answered in your analysis section is simply "we have all this data, but what does it mean?" What questions does this data answer? How does it relate to your research question ? Can this data be explained by, and is it consistent with, other papers? If not, why? These are the types of questions you'll be discussing in this section.

Source: GIPHY

Writing a Discussion and Analysis

Explain what your data means.

The primary point of a discussion section is to explain to your readers, through both statistical means and thorough explanation, what your results mean for your project. In doing so, you want to be succinct, clear, and specific about how your data backs up the claims you are making. These claims should be directly tied back to the overall focus of your paper.

What is this overall focus, you may ask? Your research question ! This discussion along with your conclusion forms the final analysis of your research - what answers did we find? Was our research successful? How do the results we found tie into and relate to the current consensus by the research community? Were our results expected or unexpected? Why or why not? These are all questions you may consider in writing your discussion section.

You showing off all of the cool findings of your research! Source: GIPHY

Why Did Your Results Happen?

After presenting your results in your results section, you may also want to explain why your results actually occurred. This is integral to gaining a full understanding of your results and the conclusions you can draw from them. For example, if data you found contradicts certain data points found in other studies, one of the most important aspects of your discussion of said data is going to be theorizing as to why this disparity took place.

Note that making broad, sweeping claims based on your data is not enough! Everything, and I mean just about everything you say in your discussions section must be backed up either by your own findings that you showed in your results section or past research that has been performed in your field.

For many situations, finding these answers is not easy, and a lot of thinking must be done as to why your results actually occurred the way they did. For some fields, specifically STEM-related fields, a discussion might dive into the theoretical foundations of your research, explaining interactions between parts of your study that led to your results. For others, like social sciences and humanities, results may be open to more interpretation.

However, "open to more interpretation" does not mean you can make claims willy nilly and claim "author's interpretation". In fact, such interpretation may be harder than STEM explanations! You will have to synthesize existing analysis on your topic and incorporate that in your analysis.

Liam Neeson explains the major question of your analysis. Source: GIPHY

Discussion vs. Summary & Repetition

Quite possibly the biggest mistake made within a discussion section is simply restating your data in a different format. The role of the discussion section is to explain your data and what it means for your project. Many students, thinking they're making discussion and analysis, simply regurgitate their numbers back in full sentences with a surface-level explanation.

Phrases like "this shows" and others similar, while good building blocks and great planning tools, often lead to a relatively weak discussion that isn't very nuanced and doesn't lead to much new understanding.

Instead, your goal will be to, through this section and your conclusion, establish a new understanding and in the end, close your gap! To do this effectively, you not only will have to present the numbers and results of your study, but you'll also have to describe how such data forms a new idea that has not been found in prior research.

This, in essence, is the heart of research - finding something new that hasn't been studied before! I don't know if it's just us, but that's pretty darn cool and something that you as the researcher should be incredibly proud of yourself for accomplishing.

Rubric Points

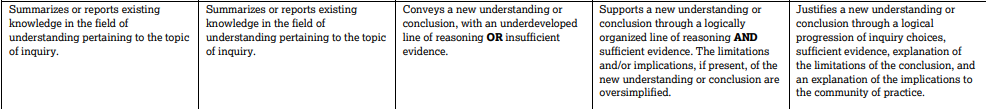

Before we close out this guide, let's take a quick peek at our best friend: the AP Research Rubric for the Discussion and Conclusion sections.

Source: CollegeBoard

Scores of One and Two: Nothing New, Your Standard Essay

Responses that earn a score of one or two on this section of the AP Research Academic Paper typically don't find much new and by this point may not have a fully developed method nor well-thought-out results. For the most part, these are more similar to essays you may have written in a prior English class or AP Seminar than a true Research paper. Instead of finding new ideas, they summarize already existing information about a topic.

Score of Three: New Understanding, Not Enough Support

A score of three is the first row that establishes a new understanding! This is a great step forward from a one or a two. However, what differentiates a three from a four or a five is the explanation and support of such a new understanding. A paper that earns a three lacks in building a line of reasoning and does not present enough evidence, both from their results section and from already published research.

Scores of Four and Five: New Understanding With A Line of Reasoning

We've made it to the best of the best! With scores of four and five, successful papers describe a new understanding with an effective line of reasoning, sufficient evidence, and an all-around great presentation of how their results signify filling a gap and answering a research question .

As far as the discussions section goes, the difference between a four and a five is more on the side of complexity and nuance. Where a four hits all the marks and does it well, a five exceeds this and writes a truly exceptional analysis. Another area where these two sections differ is in the limitations described, which we discuss in the Conclusion section guide.

You did it!!!! You have, for the most part, finished the brunt of your research paper and are over the hump! All that's left to do is tackle the conclusion, which tends to be for most the easiest section to write because all you do is summarize how your research question was answered and make some final points about how your research impacts your field. Finally, as always...

Key Terms to Review ( 1 )

Research Question

Stay Connected

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

AP® and SAT® are trademarks registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website.

Research Paper Writing: 6. Results / Analysis

- 1. Getting Started

- 2. Abstract

- 3. Introduction

- 4. Literature Review

- 5. Methods / Materials

- 6. Results / Analysis

- 7. Discussion

- 8. Conclusion

- 9. Reference

Writing about the information

There are two sections of a research paper depending on what style is being written. The sections are usually straightforward commentary of exactly what the writer observed and found during the actual research. It is important to include only the important findings, and avoid too much information that can bury the exact meaning of the context.

The results section should aim to narrate the findings without trying to interpret or evaluate, and also provide a direction to the discussion section of the research paper. The results are reported and reveals the analysis. The analysis section is where the writer describes what was done with the data found. In order to write the analysis section it is important to know what the analysis consisted of, but does not mean data is needed. The analysis should already be performed to write the results section.

Written explanations

How should the analysis section be written?

- Should be a paragraph within the research paper

- Consider all the requirements (spacing, margins, and font)

- Should be the writer’s own explanation of the chosen problem

- Thorough evaluation of work

- Description of the weak and strong points

- Discussion of the effect and impact

- Includes criticism

How should the results section be written?

- Show the most relevant information in graphs, figures, and tables

- Include data that may be in the form of pictures, artifacts, notes, and interviews

- Clarify unclear points

- Present results with a short discussion explaining them at the end

- Include the negative results

- Provide stability, accuracy, and value

How the style is presented

Analysis section

- Includes a justification of the methods used

- Technical explanation

Results section

- Purely descriptive

- Easily explained for the targeted audience

- Data driven

Example of a Results Section

Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association Sixth Ed. 2010

- << Previous: 5. Methods / Materials

- Next: 7. Discussion >>

- Last Updated: Nov 7, 2023 7:37 AM

- URL: https://wiu.libguides.com/researchpaperwriting

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Analysis is a type of primary research that involves finding and interpreting patterns in data, classifying those patterns, and generalizing the results. It is useful when looking at actions, events, or occurrences in different texts, media, or publications. Analysis can usually be done without considering most of the ethical issues discussed in the overview, as you are not working with people but rather publicly accessible documents. Analysis can be done on new documents or performed on raw data that you yourself have collected.

Here are several examples of analysis:

- Recording commercials on three major television networks and analyzing race and gender within the commercials to discover some conclusion.

- Analyzing the historical trends in public laws by looking at the records at a local courthouse.

- Analyzing topics of discussion in chat rooms for patterns based on gender and age.

Analysis research involves several steps:

- Finding and collecting documents.

- Specifying criteria or patterns that you are looking for.

- Analyzing documents for patterns, noting number of occurrences or other factors.

How to Write the Discussion Section of a Research Paper

The discussion section of a research paper analyzes and interprets the findings, provides context, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future research directions.

Updated on September 15, 2023

Structure your discussion section right, and you’ll be cited more often while doing a greater service to the scientific community. So, what actually goes into the discussion section? And how do you write it?

The discussion section of your research paper is where you let the reader know how your study is positioned in the literature, what to take away from your paper, and how your work helps them. It can also include your conclusions and suggestions for future studies.

First, we’ll define all the parts of your discussion paper, and then look into how to write a strong, effective discussion section for your paper or manuscript.

Discussion section: what is it, what it does

The discussion section comes later in your paper, following the introduction, methods, and results. The discussion sets up your study’s conclusions. Its main goals are to present, interpret, and provide a context for your results.

What is it?

The discussion section provides an analysis and interpretation of the findings, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future directions for research.

This section combines information from the preceding parts of your paper into a coherent story. By this point, the reader already knows why you did your study (introduction), how you did it (methods), and what happened (results). In the discussion, you’ll help the reader connect the ideas from these sections.

Why is it necessary?

The discussion provides context and interpretations for the results. It also answers the questions posed in the introduction. While the results section describes your findings, the discussion explains what they say. This is also where you can describe the impact or implications of your research.

Adds context for your results

Most research studies aim to answer a question, replicate a finding, or address limitations in the literature. These goals are first described in the introduction. However, in the discussion section, the author can refer back to them to explain how the study's objective was achieved.

Shows what your results actually mean and real-world implications

The discussion can also describe the effect of your findings on research or practice. How are your results significant for readers, other researchers, or policymakers?

What to include in your discussion (in the correct order)

A complete and effective discussion section should at least touch on the points described below.

Summary of key findings

The discussion should begin with a brief factual summary of the results. Concisely overview the main results you obtained.

Begin with key findings with supporting evidence

Your results section described a list of findings, but what message do they send when you look at them all together?

Your findings were detailed in the results section, so there’s no need to repeat them here, but do provide at least a few highlights. This will help refresh the reader’s memory and help them focus on the big picture.

Read the first paragraph of the discussion section in this article (PDF) for an example of how to start this part of your paper. Notice how the authors break down their results and follow each description sentence with an explanation of why each finding is relevant.

State clearly and concisely

Following a clear and direct writing style is especially important in the discussion section. After all, this is where you will make some of the most impactful points in your paper. While the results section often contains technical vocabulary, such as statistical terms, the discussion section lets you describe your findings more clearly.

Interpretation of results

Once you’ve given your reader an overview of your results, you need to interpret those results. In other words, what do your results mean? Discuss the findings’ implications and significance in relation to your research question or hypothesis.

Analyze and interpret your findings

Look into your findings and explore what’s behind them or what may have caused them. If your introduction cited theories or studies that could explain your findings, use these sources as a basis to discuss your results.

For example, look at the second paragraph in the discussion section of this article on waggling honey bees. Here, the authors explore their results based on information from the literature.

Unexpected or contradictory results

Sometimes, your findings are not what you expect. Here’s where you describe this and try to find a reason for it. Could it be because of the method you used? Does it have something to do with the variables analyzed? Comparing your methods with those of other similar studies can help with this task.

Context and comparison with previous work

Refer to related studies to place your research in a larger context and the literature. Compare and contrast your findings with existing literature, highlighting similarities, differences, and/or contradictions.

How your work compares or contrasts with previous work

Studies with similar findings to yours can be cited to show the strength of your findings. Information from these studies can also be used to help explain your results. Differences between your findings and others in the literature can also be discussed here.

How to divide this section into subsections

If you have more than one objective in your study or many key findings, you can dedicate a separate section to each of these. Here’s an example of this approach. You can see that the discussion section is divided into topics and even has a separate heading for each of them.

Limitations

Many journals require you to include the limitations of your study in the discussion. Even if they don’t, there are good reasons to mention these in your paper.

Why limitations don’t have a negative connotation

A study’s limitations are points to be improved upon in future research. While some of these may be flaws in your method, many may be due to factors you couldn’t predict.

Examples include time constraints or small sample sizes. Pointing this out will help future researchers avoid or address these issues. This part of the discussion can also include any attempts you have made to reduce the impact of these limitations, as in this study .

How limitations add to a researcher's credibility

Pointing out the limitations of your study demonstrates transparency. It also shows that you know your methods well and can conduct a critical assessment of them.

Implications and significance

The final paragraph of the discussion section should contain the take-home messages for your study. It can also cite the “strong points” of your study, to contrast with the limitations section.

Restate your hypothesis

Remind the reader what your hypothesis was before you conducted the study.

How was it proven or disproven?

Identify your main findings and describe how they relate to your hypothesis.

How your results contribute to the literature

Were you able to answer your research question? Or address a gap in the literature?

Future implications of your research

Describe the impact that your results may have on the topic of study. Your results may show, for instance, that there are still limitations in the literature for future studies to address. There may be a need for studies that extend your findings in a specific way. You also may need additional research to corroborate your findings.

Sample discussion section

This fictitious example covers all the aspects discussed above. Your actual discussion section will probably be much longer, but you can read this to get an idea of everything your discussion should cover.

Our results showed that the presence of cats in a household is associated with higher levels of perceived happiness by its human occupants. These findings support our hypothesis and demonstrate the association between pet ownership and well-being.

The present findings align with those of Bao and Schreer (2016) and Hardie et al. (2023), who observed greater life satisfaction in pet owners relative to non-owners. Although the present study did not directly evaluate life satisfaction, this factor may explain the association between happiness and cat ownership observed in our sample.

Our findings must be interpreted in light of some limitations, such as the focus on cat ownership only rather than pets as a whole. This may limit the generalizability of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had several strengths. These include its strict exclusion criteria and use of a standardized assessment instrument to investigate the relationships between pets and owners. These attributes bolster the accuracy of our results and reduce the influence of confounding factors, increasing the strength of our conclusions. Future studies may examine the factors that mediate the association between pet ownership and happiness to better comprehend this phenomenon.

This brief discussion begins with a quick summary of the results and hypothesis. The next paragraph cites previous research and compares its findings to those of this study. Information from previous studies is also used to help interpret the findings. After discussing the results of the study, some limitations are pointed out. The paper also explains why these limitations may influence the interpretation of results. Then, final conclusions are drawn based on the study, and directions for future research are suggested.

How to make your discussion flow naturally

If you find writing in scientific English challenging, the discussion and conclusions are often the hardest parts of the paper to write. That’s because you’re not just listing up studies, methods, and outcomes. You’re actually expressing your thoughts and interpretations in words.

- How formal should it be?

- What words should you use, or not use?

- How do you meet strict word limits, or make it longer and more informative?

Always give it your best, but sometimes a helping hand can, well, help. Getting a professional edit can help clarify your work’s importance while improving the English used to explain it. When readers know the value of your work, they’ll cite it. We’ll assign your study to an expert editor knowledgeable in your area of research. Their work will clarify your discussion, helping it to tell your story. Find out more about AJE Editing.

Adam Goulston, PsyD, MS, MBA, MISD, ELS

Science Marketing Consultant

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

- Research guides

Writing an Educational Research Paper

Research paper sections, customary parts of an education research paper.

There is no one right style or manner for writing an education paper. Content aside, the writing style and presentation of papers in different educational fields vary greatly. Nevertheless, certain parts are common to most papers, for example:

Title/Cover Page

Contains the paper's title, the author's name, address, phone number, e-mail, and the day's date.

Not every education paper requires an abstract. However, for longer, more complex papers abstracts are particularly useful. Often only 100 to 300 words, the abstract generally provides a broad overview and is never more than a page. It describes the essence, the main theme of the paper. It includes the research question posed, its significance, the methodology, and the main results or findings. Footnotes or cited works are never listed in an abstract. Remember to take great care in composing the abstract. It's the first part of the paper the instructor reads. It must impress with a strong content, good style, and general aesthetic appeal. Never write it hastily or carelessly.

Introduction and Statement of the Problem

A good introduction states the main research problem and thesis argument. What precisely are you studying and why is it important? How original is it? Will it fill a gap in other studies? Never provide a lengthy justification for your topic before it has been explicitly stated.

Limitations of Study

Indicate as soon as possible what you intend to do, and what you are not going to attempt. You may limit the scope of your paper by any number of factors, for example, time, personnel, gender, age, geographic location, nationality, and so on.

Methodology

Discuss your research methodology. Did you employ qualitative or quantitative research methods? Did you administer a questionnaire or interview people? Any field research conducted? How did you collect data? Did you utilize other libraries or archives? And so on.

Literature Review

The research process uncovers what other writers have written about your topic. Your education paper should include a discussion or review of what is known about the subject and how that knowledge was acquired. Once you provide the general and specific context of the existing knowledge, then you yourself can build on others' research. The guide Writing a Literature Review will be helpful here.

Main Body of Paper/Argument

This is generally the longest part of the paper. It's where the author supports the thesis and builds the argument. It contains most of the citations and analysis. This section should focus on a rational development of the thesis with clear reasoning and solid argumentation at all points. A clear focus, avoiding meaningless digressions, provides the essential unity that characterizes a strong education paper.

After spending a great deal of time and energy introducing and arguing the points in the main body of the paper, the conclusion brings everything together and underscores what it all means. A stimulating and informative conclusion leaves the reader informed and well-satisfied. A conclusion that makes sense, when read independently from the rest of the paper, will win praise.

Works Cited/Bibliography

See the Citation guide .

Education research papers often contain one or more appendices. An appendix contains material that is appropriate for enlarging the reader's understanding, but that does not fit very well into the main body of the paper. Such material might include tables, charts, summaries, questionnaires, interview questions, lengthy statistics, maps, pictures, photographs, lists of terms, glossaries, survey instruments, letters, copies of historical documents, and many other types of supplementary material. A paper may have several appendices. They are usually placed after the main body of the paper but before the bibliography or works cited section. They are usually designated by such headings as Appendix A, Appendix B, and so on.

- << Previous: Choosing a Topic

- Next: Find Books >>

- Last Updated: Dec 5, 2023 2:26 PM

- Subjects: Education

- Tags: education , education_paper , education_research_paper

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

The research process, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Structuring the Research Paper

Formal research structure.

These are the primary purposes for formal research:

enter the discourse, or conversation, of other writers and scholars in your field

learn how others in your field use primary and secondary resources

find and understand raw data and information

For the formal academic research assignment, consider an organizational pattern typically used for primary academic research. The pattern includes the following: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions/recommendations.

Usually, research papers flow from the general to the specific and back to the general in their organization. The introduction uses a general-to-specific movement in its organization, establishing the thesis and setting the context for the conversation. The methods and results sections are more detailed and specific, providing support for the generalizations made in the introduction. The discussion section moves toward an increasingly more general discussion of the subject, leading to the conclusions and recommendations, which then generalize the conversation again.

Sections of a Formal Structure

The introduction section.

Many students will find that writing a structured introduction gets them started and gives them the focus needed to significantly improve their entire paper.

Introductions usually have three parts:

presentation of the problem statement, the topic, or the research inquiry

purpose and focus of your paper

summary or overview of the writer’s position or arguments

In the first part of the introduction—the presentation of the problem or the research inquiry—state the problem or express it so that the question is implied. Then, sketch the background on the problem and review the literature on it to give your readers a context that shows them how your research inquiry fits into the conversation currently ongoing in your subject area.

In the second part of the introduction, state your purpose and focus. Here, you may even present your actual thesis. Sometimes your purpose statement can take the place of the thesis by letting your reader know your intentions.

The third part of the introduction, the summary or overview of the paper, briefly leads readers through the discussion, forecasting the main ideas and giving readers a blueprint for the paper.

The following example provides a blueprint for a well-organized introduction.

Example of an Introduction

Entrepreneurial Marketing: The Critical Difference

In an article in the Harvard Business Review, John A. Welsh and Jerry F. White remind us that “a small business is not a little big business.” An entrepreneur is not a multinational conglomerate but a profit-seeking individual. To survive, he must have a different outlook and must apply different principles to his endeavors than does the president of a large or even medium-sized corporation. Not only does the scale of small and big businesses differ, but small businesses also suffer from what the Harvard Business Review article calls “resource poverty.” This is a problem and opportunity that requires an entirely different approach to marketing. Where large ad budgets are not necessary or feasible, where expensive ad production squanders limited capital, where every marketing dollar must do the work of two dollars, if not five dollars or even ten, where a person’s company, capital, and material well-being are all on the line—that is, where guerrilla marketing can save the day and secure the bottom line (Levinson, 1984, p. 9).

By reviewing the introductions to research articles in the discipline in which you are writing your research paper, you can get an idea of what is considered the norm for that discipline. Study several of these before you begin your paper so that you know what may be expected. If you are unsure of the kind of introduction your paper needs, ask your professor for more information. The introduction is normally written in present tense.

THE METHODS SECTION

The methods section of your research paper should describe in detail what methodology and special materials if any, you used to think through or perform your research. You should include any materials you used or designed for yourself, such as questionnaires or interview questions, to generate data or information for your research paper. You want to include any methodologies that are specific to your particular field of study, such as lab procedures for a lab experiment or data-gathering instruments for field research. The methods section is usually written in the past tense.

THE RESULTS SECTION

How you present the results of your research depends on what kind of research you did, your subject matter, and your readers’ expectations.

Quantitative information —data that can be measured—can be presented systematically and economically in tables, charts, and graphs. Quantitative information includes quantities and comparisons of sets of data.

Qualitative information , which includes brief descriptions, explanations, or instructions, can also be presented in prose tables. This kind of descriptive or explanatory information, however, is often presented in essay-like prose or even lists.

There are specific conventions for creating tables, charts, and graphs and organizing the information they contain. In general, you should use them only when you are sure they will enlighten your readers rather than confuse them. In the accompanying explanation and discussion, always refer to the graphic by number and explain specifically what you are referring to; you can also provide a caption for the graphic. The rule of thumb for presenting a graphic is first to introduce it by name, show it, and then interpret it. The results section is usually written in the past tense.

THE DISCUSSION SECTION

Your discussion section should generalize what you have learned from your research. One way to generalize is to explain the consequences or meaning of your results and then make your points that support and refer back to the statements you made in your introduction. Your discussion should be organized so that it relates directly to your thesis. You want to avoid introducing new ideas here or discussing tangential issues not directly related to the exploration and discovery of your thesis. The discussion section, along with the introduction, is usually written in the present tense.

THE CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS SECTION

Your conclusion ties your research to your thesis, binding together all the main ideas in your thinking and writing. By presenting the logical outcome of your research and thinking, your conclusion answers your research inquiry for your reader. Your conclusions should relate directly to the ideas presented in your introduction section and should not present any new ideas.

You may be asked to present your recommendations separately in your research assignment. If so, you will want to add some elements to your conclusion section. For example, you may be asked to recommend a course of action, make a prediction, propose a solution to a problem, offer a judgment, or speculate on the implications and consequences of your ideas. The conclusions and recommendations section is usually written in the present tense.

Key Takeaways

- For the formal academic research assignment, consider an organizational pattern typically used for primary academic research.

- The pattern includes the following: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions/recommendations.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Research Voyage

Research Tips and Infromation

07 Easy Steps for Writing Discussion Section of a Research Paper

In my role as a journal reviewer, I’ve had the privilege (and sometimes the frustration) of reviewing numerous research papers.

I’ve encountered papers where authors neglect to discuss how their results benefit the problem at hand, the domain they are working in, and society at large. This oversight often fails to make a lasting impression on reviewers

One recurring issue that I’ve noticed, time and again, is the challenge of properly delineating the boundaries of the discussion section in research papers. It’s not uncommon to come across papers where authors blur the lines between various crucial sections in a research paper.

Some authors mistakenly present their results within the discussion section, failing to provide a clear delineation between the findings of their study and their interpretation. Even if the journal allows to combine the results and discussion section, adopting a structured approach, such as dedicating a paragraph for results and a paragraph for discussing the results, can enhance the flow and readability of the paper, ensuring that readers can easily follow the progression of the study and its implications.

I vividly recall one instance where an author proceeded to rehash the entire methodology, complete with block diagrams, within the discussion section—without ever drawing any substantive conclusions. It felt like wading through familiar territory, only to find myself back at square one.

And then there are those authors who seem more interested in speculating about future directions than analyzing the outcomes of their current work in the discussion section. While it’s important to consider the implications of one’s research, it shouldn’t overshadow the critical analysis of the results at hand.

In another instance, a researcher concealed all failures or limitations in their work, presenting only the best-case scenarios, which created doubts about the validity of their findings. As a reviewer, I promptly sent it back for a relook and suggested adding various scenarios to reflect the true behaviour of the experiment.

In this post, I’ll delve into practical strategies for crafting the discussion section of a research paper. Drawing from my experiences as a reviewer and researcher, I’ll explore the nuances of the discussion section and provide insights into how to engage in critical discussion.

Introduction

I. focus on the relevance.

- II. Highlight the Limitations

- III. Introduce New Discoveries

IV. Highlight the Observations

V. compare and relate with other research works.

- VI. Provide Alternate View Points

A. Future Directions

B. conclusion, how to validate the claims i made in the discussion section of my research paper, phrases that can be used in the discussion section of a research paper, phrases that can be used in the analysis part of the discussion section of a research paper.

- Your Next Move...

Whether charts and graphs are allowed in discussion section of my Research Paper?

Can i add citations in discussion section of my research paper, can i combine results and discussion section in my research paper, what is the weightage of discussion section in a research paper in terms of selection to a journal, whether literature survey paper has a discussion section.

The Discussion section of a research paper is where authors interpret their findings, contextualize their research, and propose future directions. It is a crucial section that provides the reader with insights into the significance and implications of the study.

Writing an effective discussion section is a crucial aspect of any research paper, as it allows researchers to delve into the significance of their findings and explore their implications. A well-crafted discussion section not only summarizes the key observations and limitations of the study but also establishes connections with existing research and opens avenues for future exploration. In this article, we will present a comprehensive guide to help you structure your discussion section in seven simple steps.

By following these steps, you’ll be able to write a compelling Discussion section that enhances the reader’s understanding of your research and contributes to the broader scientific community.

Please note, the discussion section usually follows after the Results Section. I have written a comprehensive article on ” How to Write Results Section of your Research Paper “. Please visit the article to enhance your write-up on the results section.

Which are these 07 steps for writing an Effective Discussion Section of a Research Paper?

Step 1: Focus on the Relevance : In the first step, we will discuss the importance of emphasizing the relevance of your research findings to the broader scientific context. By clearly articulating the significance of your study, you can help readers understand how your work contributes to the existing body of knowledge and why it matters.

Step 2: Highlight the Limitations : Every research study has its limitations, and it is essential to address them honestly and transparently. We will explore how to identify and describe the limitations of your study, demonstrating a thorough understanding of potential weaknesses and areas for improvement.

Step 3: Highlight the Observations : In this step, we will delve into the core findings of your study. We will discuss the key observations and results, focusing on their relevance to your research objectives. By providing a concise summary of your findings, you can guide readers through the main outcomes of your study.

Step 4: Compare and Relate with Other Research Works : Research is a collaborative and cumulative process, and it is vital to establish connections between your study and previous research. We will explore strategies to compare and relate your findings to existing literature, highlighting similarities, differences, and gaps in knowledge.

Step 5: Provide Alternate Viewpoints: Science thrives on the diversity of perspectives. Acknowledging different viewpoints and interpretations of your results fosters a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic. We will discuss how to incorporate alternative viewpoints into your discussion, encouraging a balanced and nuanced analysis.

Step 6: Show Future Directions : A well-crafted discussion section not only summarizes the present but also points towards the future. We will explore techniques to suggest future research directions based on the implications of your study, providing a roadmap for further investigations in the field.

Step 7: Concluding Thoughts : In the final step, we will wrap up the discussion section by summarizing the key points and emphasizing the overall implications of your research. We will discuss the significance of your study’s contributions and offer some closing thoughts to leave a lasting impression on your readers.

By following these seven steps, you can craft a comprehensive and insightful discussion section that not only synthesizes your findings but also engages readers in a thought-provoking dialogue about the broader implications and future directions of your research. Let’s delve into each step in detail to enhance the quality and impact of your discussion section.

The purpose of every research is to implement the results for the positive development of the relevant subject. In research, it is crucial to emphasize the relevance of your study to the field and its potential impact. Before delving into the details of how the research was conceived and the sequence of developments that took place, consider highlighting the following factors to establish the relevance of your work:

- Identifying a pressing problem or research gap: Example: “This research addresses the critical problem of network security in wireless communication systems. With the widespread adoption of wireless networks, the vulnerability to security threats has increased significantly. Existing security mechanisms have limitations in effectively mitigating these threats. Therefore, there is a pressing need to develop novel approaches that enhance the security of wireless communication systems.”

- Explaining the significance and potential impact of the research: Example: “By developing an intelligent intrusion detection system using machine learning algorithms, this research aims to significantly enhance the security of wireless networks. The successful implementation of such a system would not only protect sensitive data and communication but also ensure the reliability and integrity of wireless networks in various applications, including Internet of Things (IoT), smart cities, and critical infrastructure.”

- Establishing connections with previous research and advancements in the field: Example: “This study builds upon previous research on intrusion detection systems and machine learning techniques. By leveraging recent advancements in deep learning algorithms and anomaly detection methods, we aim to overcome the limitations of traditional rule-based intrusion detection systems and achieve higher detection accuracy and efficiency.”

By emphasizing the relevance of your research and articulating its potential impact, you set the stage for readers to understand the significance of your work in the broader context. This approach ensures that readers grasp the motivations behind your research and the need for further exploration in the field.

II. Highlight the Limitations

Many times the research is on a subject that might have legal limitations or restrictions. This limitation might have caused certain imperfections in carrying out research or in results. This issue should be acknowledged by the researcher before the work is criticized by others later in his/her discussion section.

In computer science research, it is important to identify and openly acknowledge the limitations of your study. By doing so, you demonstrate transparency and a thorough understanding of potential weaknesses, allowing readers to interpret the findings in a more informed manner. Here’s an example:

Example: “It is crucial to acknowledge certain limitations and constraints that have affected the outcomes of this research. In the context of privacy-sensitive applications such as facial recognition systems, there are legal limitations and ethical concerns that can impact the accuracy and performance of the developed algorithm. These limitations stem from regulations and policies that impose restrictions on data collection, access, and usage to protect individuals’ privacy rights. As a result, the algorithm developed in this study operates under these legal constraints, which may have introduced certain imperfections.”

In this example, the researcher is working on a facial recognition system and acknowledges the legal limitations and ethical concerns associated with privacy-sensitive applications. By openly addressing these limitations, the researcher demonstrates an understanding of the challenges imposed by regulations and policies. This acknowledgement sets the stage for a more nuanced discussion and prevents others from solely criticizing the work based on these limitations without considering the broader legal context.

By highlighting the limitations, researchers can also offer potential solutions or future directions to mitigate the impact of these constraints. For instance, the researcher may suggest exploring advanced privacy-preserving techniques or collaborating with legal experts to find a balance between privacy protection and system performance.

By acknowledging and addressing the limitations, researchers demonstrate their awareness of potential weaknesses in their study, maintaining credibility, and fostering a more constructive discussion of their findings within the context of legal and ethical considerations.

III. Introduce New Discoveries

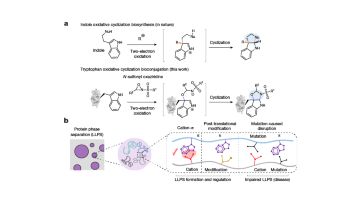

Begin the discussion section by stating all the major findings in the course of the research. The first paragraph should have the findings mentioned, which is expected to be synoptic, naming and briefly describing the analysis of results.

Example: “In this study, several significant discoveries emerged from the analysis of the collected data. The findings revealed compelling insights into the performance of parallel computing architectures for large-scale data processing. Through comprehensive experimentation and analysis, the following key discoveries were made:

- Discovery 1: The proposed parallel computing architecture demonstrated a 30% improvement in processing speed compared to traditional sequential computing methods. This finding highlights the potential of parallel computing for accelerating data-intensive tasks.

- Discovery 2: A direct relationship between the number of processing cores and the overall system throughput was observed. As the number of cores increased, the system exhibited a near-linear scalability, enabling efficient utilization of available computational resources.

- Discovery 3: The analysis revealed a trade-off between processing speed and energy consumption. While parallel computing achieved faster processing times, it also resulted in higher energy consumption. This finding emphasizes the importance of optimizing energy efficiency in parallel computing systems.

These discoveries shed light on the performance characteristics and trade-offs associated with parallel computing architectures for large-scale data processing tasks. The following sections will delve into the implications of these findings, discussing their significance, limitations, and potential applications.”

In this example, the researcher presents a concise overview of the major discoveries made during the research. Each discovery is briefly described, highlighting the key insights obtained from the analysis. By summarizing the findings in a synoptic manner, the reader gains an immediate understanding of the notable contributions and can anticipate the subsequent detailed discussion.

This approach allows the discussion section to begin with a clear and impactful introduction of the major discoveries, capturing the reader’s interest and setting the stage for a comprehensive exploration of each finding in subsequent paragraphs.

Coming to the major part of the findings, the discussion section should interpret the key observations, the analysis of charts, and the analysis of tables. In the field of computer science, presenting and explaining the results in a clear and accessible manner is essential for readers to grasp the significance of the findings. Here are some examples of how to effectively highlight observations in computer science research:

Begin with explaining the objective of the research, followed by what inspired you as a researcher to study the subject:

In a study on machine learning algorithms for sentiment analysis, start by stating the goal of developing an accurate and efficient sentiment analysis model. Share your motivation for choosing this research topic, such as the increasing importance of sentiment analysis in various domains like social media, customer feedback analysis, and market research.

Example: The objective of this research was to develop a sentiment analysis model using machine learning algorithms. As sentiment analysis plays a vital role in understanding public opinion and customer feedback, we were motivated by the need for an accurate and efficient model that could be applied in various domains such as social media analysis, customer reviews, and market research.

Explain the meaning of the findings, as every reader might not understand the analysis of graphs and charts as easily as people who are in the same field as you:

If your research involves analyzing performance metrics of different algorithms, consider presenting the results in a visually intuitive manner, such as line graphs or bar charts. In the discussion section, explain the significance of the trends observed in the graphs. For instance, if a particular algorithm consistently outperforms others in terms of accuracy, explain why this finding is noteworthy and how it aligns with existing knowledge in the field.

Example: To present the performance evaluation of the algorithms, we analyzed multiple metrics, including precision, recall, and F1 score. The line graph in Figure 1 demonstrates the trends observed. It is noteworthy that Algorithm A consistently outperformed the other algorithms across all metrics. This finding indicates that Algorithm A has a higher ability to accurately classify sentiment in comparison to its counterparts. This aligns with previous studies that have also highlighted the robustness of Algorithm A in sentiment analysis tasks.

Ensure the reader can understand the key observations without being forced to go through the whole paper:

In computer science research, it is crucial to present concise summaries of your key observations to facilitate understanding for readers who may not have the time or expertise to go through the entire paper. For example, if your study compares the runtime performance of two programming languages for a specific task, clearly state the observed differences and their implications. Highlight any unexpected or notable findings that may challenge conventional wisdom or open up new avenues for future exploration.

Example: In this study comparing the runtime performance of Python and Java for a specific computational task, we observed notable differences. Python consistently showed faster execution times, averaging 20% less time than Java across varying input sizes. These results challenge the common perception that Java is the superior choice for computationally intensive tasks. The observed performance advantage of Python in this context suggests the need for further investigation into the underlying factors contributing to this discrepancy, such as differences in language design and optimization strategies.

By employing these strategies, researchers can effectively highlight their observations in the discussion section. This enables readers to gain a clear understanding of the significance of the findings and their implications without having to delve into complex technical details.

No one is ever the only person researching a particular subject. A researcher always has companions and competitors. The discussion section should have a detailed comparison of the research. It should present the facts that relate the research to studies done on the same subject.

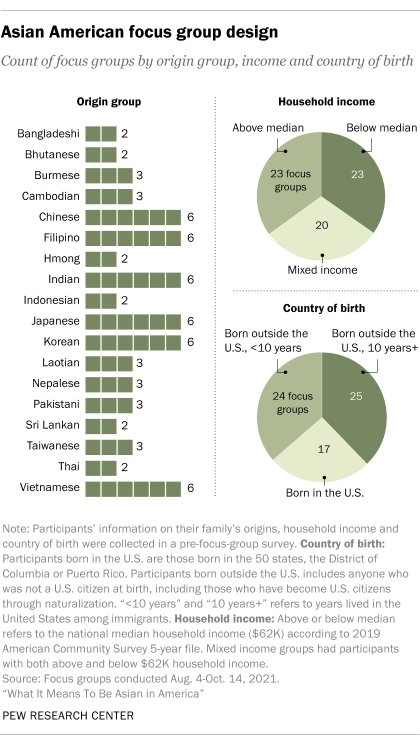

Example: The table below compares some of the well-known prediction techniques with our fuzzy predictor with MOM defuzzification for response time, relative error and Environmental constraints. Based on the results obtained it can be concluded that the Fuzzy predictor with MOM defuzzification has a less relative error and quick response time as compared to other prediction techniques. The proposed predictor is more flexible, simple to implement and deals with noisy and uncertain data from real-life situations. The relative error of 5-10% is acceptable for our system as the predicted fuzzy region and the fuzzy region of the actual position remains the same.

Table 1 : Comparison of well-known Robot Motion prediction Techniques

VI. Provide Alternate View Points

Almost every time, it has been noticed that analysis of charts and graphs shows results that tend to have more than one explanation. The researcher must consider every possible explanation and potential enhancement of the study from alternative viewpoints. It is critically important that this is clearly put out to the readers in the discussion section.

In the discussion section of a research paper, it is important to acknowledge that data analysis often yields results that can be interpreted in multiple ways. By considering different viewpoints and potential enhancements, researchers can provide a more comprehensive and nuanced analysis of their findings. Here are some examples:

Example 1: “The analysis of our experimental data showed a decrease in system performance following the implementation of the proposed optimization technique. While our initial interpretation suggested that the optimization failed to achieve the desired outcome, an alternate viewpoint could be that the decrease in performance was influenced by an external factor, such as the configuration of the hardware setup. Further investigation into the hardware settings and benchmarking protocols is necessary to fully understand the observed results and identify potential enhancements.”

Example 2: “The analysis of user feedback revealed a mixed response to the redesigned user interface. While some participants reported improved usability and satisfaction, others expressed confusion and dissatisfaction. An alternate viewpoint could be that the diverse range of user backgrounds and preferences might have influenced these varied responses. Further research should focus on conducting user studies with a larger and more diverse sample to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying factors contributing to the contrasting user experiences.”

Example 3: “Our study found a positive correlation between the implementation of agile methodologies and project success rates. However, an alternate viewpoint suggests that other factors, such as team dynamics and project complexity, could have influenced the observed correlation. Future research should explore the interactions between agile methodologies and these potential confounding factors to gain a more comprehensive understanding of their impact on project success.”

In these examples, researchers present alternative viewpoints that offer different interpretations or explanations for the observed results. By acknowledging these alternate viewpoints, researchers demonstrate a balanced and comprehensive analysis of their findings. It is crucial to clearly communicate these alternative perspectives to readers in the discussion section, as it encourages critical thinking and highlights the complexity and potential limitations of the research.

By presenting alternate viewpoints, researchers invite further exploration and discussion, fostering a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic. This approach enriches the scientific discourse and promotes a deeper analysis of the findings, contributing to the overall advancement of knowledge in the field.

VII. Future Directions and Conclusion

The section must have suggestions for research that should be done to unanswered questions. These should be suggested at the beginning of the discussion section to avoid questions being asked by critics. Emphasizing the importance of following future directions can lead to new research as well.

Example: ” While this study provides valuable insights into the performance of the proposed algorithm, there are several unanswered questions and avenues for future research that merit attention. By identifying these areas, we aim to stimulate further exploration and contribute to the continuous advancement of the field. The following future directions are suggested:

- Future Direction 1: Investigating the algorithm’s performance under different dataset characteristics and distributions. The current study focused on a specific dataset, but it would be valuable to evaluate the algorithm’s robustness and generalizability across a broader range of datasets, including real-world scenarios and diverse data sources.

- Future Direction 2: Exploring the potential integration of additional machine learning techniques or ensemble methods to further enhance the algorithm’s accuracy and reliability. By combining the strengths of multiple models, it is possible to achieve better performance and handle complex patterns and outliers more effectively.

- Future Direction 3: Extending the evaluation to consider the algorithm’s scalability in large-scale deployment scenarios. As the volume of data continues to grow exponentially, it is crucial to assess the algorithm’s efficiency and scalability in handling big data processing requirements.

By suggesting these future directions, we hope to inspire researchers to explore new avenues and build upon the foundation laid by this study. Addressing these unanswered questions will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the algorithm’s capabilities and limitations, paving the way for further advancements in the field.”

In this example, the researcher presents specific future directions that can guide further research. Each future direction is described concisely, highlighting the specific area of investigation and the potential benefits of pursuing those directions. By suggesting these future directions early in the discussion section, the researcher proactively addresses potential questions or criticisms and demonstrates a proactive approach to knowledge expansion.

By emphasizing the importance of following future directions, researchers not only inspire others to continue the research trajectory but also contribute to the collective growth of the field. This approach encourages ongoing exploration, innovation, and collaboration, ensuring the continuous development and improvement of computer science research.

In the final step, wrap up the discussion section by summarizing the key points and emphasizing the overall implications of your research. We will discuss the significance of your study’s contributions and offer some closing thoughts to leave a lasting impression on your readers. This section serves as a crucial opportunity to reinforce the main findings and highlight the broader impact of your work. Here are some examples:

Example 1: “In conclusion, this research has made significant contributions to the field of natural language processing. By proposing a novel neural network architecture for language generation, we have demonstrated the effectiveness and versatility of the model in generating coherent and contextually relevant sentences. The experimental results indicate a significant improvement in language generation quality compared to existing approaches. The implications of this research extend beyond traditional applications, opening up new possibilities for automated content creation, chatbot systems, and dialogue generation in artificial intelligence.”

Example 2: “In summary, this study has provided valuable insights into the optimization of network routing protocols for wireless sensor networks. By proposing a novel hybrid routing algorithm that combines the advantages of both reactive and proactive protocols, we have demonstrated enhanced network performance in terms of latency, energy efficiency, and scalability. The experimental results validate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm in dynamic and resource-constrained environments. These findings have implications for various applications, including environmental monitoring, industrial automation, and smart city infrastructure.”

Example 3: “In closing, this research sheds light on the security vulnerabilities of blockchain-based smart contracts. By conducting an extensive analysis of existing smart contract platforms and identifying potential attack vectors, we have highlighted the need for robust security measures to mitigate risks and protect user assets. The insights gained from this study can guide the development of more secure and reliable smart contract frameworks, ensuring the integrity and trustworthiness of blockchain-based applications across industries such as finance, supply chain, and decentralized applications.”

In these examples, the concluding thoughts summarize the main contributions and findings of the research. They emphasize the significance of the study’s implications and highlight the potential impact on various domains within computer science. By providing a succinct and impactful summary, the researcher leaves a lasting impression on readers, reinforcing the value and relevance of the research in the field.

Validating claims in the discussion section of a research paper is essential to ensure the credibility and reliability of your findings. Here are some strategies to validate the claims made in the discussion section:

- Referencing supporting evidence: Cite relevant sources from the existing literature that provide evidence or support for your claims. These sources can include peer-reviewed studies, research articles, and authoritative sources in your field. By referencing credible and reputable sources, you establish the validity of your claims and demonstrate that your interpretations are grounded in existing knowledge.

- Relating to the results: Connect your claims to the results presented in the earlier sections of your research paper. Clearly demonstrate how the findings support your claims and provide evidence for your interpretations. Refer to specific data, measurements, statistical analyses, or other evidence from your results section to substantiate your claims.

- Comparing with previous research: Discuss how your findings align with or diverge from previous research in the field. Reference relevant studies and explain how your results compare to or build upon existing knowledge. By contextualizing your claims within the broader research landscape, you provide further validation for your interpretations.

- Addressing limitations and alternative explanations: Acknowledge the limitations of your study and consider alternative explanations for your findings. By addressing potential counterarguments and alternative viewpoints, you demonstrate a thorough evaluation of your claims and increase the robustness of your conclusions.

- Seeking peer feedback: Prior to submitting your research paper, consider seeking feedback from colleagues or experts in your field. They can provide valuable insights and suggestions for further validating your claims or improving the clarity of your arguments.

- Inviting replication and further research: Encourage other researchers to replicate your study or conduct further investigations. By promoting replication and future research, you contribute to the ongoing validation and refinement of your claims.

Remember, the validation of claims in the discussion section is a critical aspect of scientific research. By employing rigorous methods and logical reasoning, you can strengthen the credibility and impact of your findings and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in your field.

Here are some common phrases that can be used in the discussion section of a paper or research article. I’ve included a table with examples to illustrate how these phrases might be used:

Here are some common academic phrases that can be used in the analysis section of a paper or research article. I have included a table with examples to illustrate how these phrases might be used:

Your Next Move…

I believe you will proceed to write conclusion section of your research paper. Conclusion section is the most neglected part of the research paper as many authors feel it is unnecessary but write in a hurry to submit the article to some reputed journal.

Please note, once your paper gets published , the readers decide to read your full paper based only on abstract and conclusion. They decide the relevance of the paper based on only these two sections. If they don’t read then they don’t cite and this in turn affects your citation score. So my sincere advice to you is not to neglect this section.

Visit my article on “How to Write Conclusion Section of Research Paper” for further details.

Please visit my article on “ Importance and Improving of Citation Score for Your Research Paper ” for increasing your visibility in research community and on Google Scholar Citation Score.

The Discussion section of a research paper is an essential part of any study, as it allows the author to interpret their results and contextualize their findings. To write an effective Discussion section, authors should focus on the relevance of their research, highlight the limitations, introduce new discoveries, highlight their observations, compare and relate their findings to other research works, provide alternate viewpoints, and show future directions.

By following these 7 steps, authors can ensure that their Discussion section is comprehensive, informative, and thought-provoking. A well-written Discussion section not only helps the author interpret their results but also provides insights into the implications and applications of their research.

In conclusion, the Discussion section is an integral part of any research paper, and by following these 7 steps, authors can write a compelling and informative discussion section that contributes to the broader scientific community.

Frequently Asked Questions

Yes, charts and graphs are generally allowed in the discussion section of a research paper. While the discussion section is primarily focused on interpreting and discussing the findings, incorporating visual aids such as charts and graphs can be helpful in presenting and supporting the analysis.

Yes, you can add citations in the discussion section of your research paper. In fact, it is highly recommended to support your statements, interpretations, and claims with relevant and credible sources. Citations in the discussion section help to strengthen the validity and reliability of your arguments and demonstrate that your findings are grounded in existing literature.