The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Trusted Health Information from the National Institutes of Health

Teens are talking about mental health

High schoolers' stories give a glimpse into the national crisis.

Adolescence can be a complicated time, especially for mental health, and some teens want their communities to do more in response.

The prevalence of mental health issues is hard to measure, but federal data show how widespread the challenges are. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said we need to address threats to mental health in young people—especially adolescents.

More than one third (37%) of high schoolers in the United States reported experiencing poor mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a 2021 CDC study . Almost half (44%) of high schoolers reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless in the last year. Some of these feelings were also linked to experiences of racism, social stigma around gender and sexual identity, and sexual violence.

"I was also having issues with my friendships at school and an increased level of stress when it came time for tests, projects, and other assessments…the feeling of isolation, lack of appetite, and absolute hatred of school were not normal." –Morgan, New Jersey

Studies like these can help shed light on issues that teens may be hesitant or unable to discuss with parents, doctors , and school staff.

Stigma and a lack of information or access to care also keep many teens from getting help. But sharing personal stories about mental health can offer encouragement and connection. This can help teens feel like they are not alone. That’s why NIH asked high schoolers to describe these challenges in their own words for the 2022 Speaking Up About Mental Health! essay contest.

The contest was sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). They wanted to start conversations around youth mental health and highlight different aspects of this national health crisis.

In their essays, many students talked about feeling lost, embarrassed, or frustrated by their mental health struggles. Others wrote about going from being confident in early childhood to feeling alone or unseen in adolescence.

NIH-funded researcher Tamar Mendelson, M.A., Ph.D., Bloomberg Professor of American Health and Director for the Center for Adolescent Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, says that’s not surprising. Depression rates tend to increase around puberty, especially among girls but also in boys. Dr. Mendelson said this can be caused by a combination of hormonal changes, new social relationships, and new pressures from academic, athletic, and other activities.

"For many Asian American youths, getting help for mental health can be hindered by stereotypes. Asian American boys, in particular, may not seek therapy since their cultures expect them to be more resilient than girls. After all, as the older brother, how can I let my little sister know when I am not feeling well emotionally?" –Evan, Texas

“Young people who are feeling overwhelmed or are not sure how to cope with emotions may be more likely to use substances to kind of help with that,” Dr. Mendelson said. Such substances could include alcohol, tobacco, or prescription or illicit drugs, for example.

Puberty is also when many young people become more aware of their sexual orientations and gender identities. For some, this can lead to being unaccepted or bullied. Rates of substance use and misuse also tend to increase during puberty.

In addition to navigating the typical stressors that teens face, more recently they also had to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic and related family losses or financial struggles. They’ve experienced or witnessed racial- and identity-based discrimination, gun violence, political unrest, natural disasters, and climate change. These challenges coupled with other risk factors, including some parenting styles, can lead to mental health issues such as anxiety and depression.

Even though environmental triggers have changed over time, adolescent anxiety was rising even before the pandemic.

Michele Ybarra, Ph.D., an adjunct professor of mental health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and also an NIH-supported researcher, said that not long ago, it was widely believed that youth could not have depression because people thought, “What do [they] have to be depressed about?”

"Schools are places where students should feel safe and comfortable enough to ask for help. By using simple technology and dedicating time toward impactful mental health screening, schools can truly serve students and assist them in living happier, healthier lives." –Huda, North Carolina

But in the last several decades, Dr. Ybarra said, mental health professionals have realized that depression can happen to anyone at any age.

Several students wrote about schools with limited, outdated, or no education on the topic. Some said they could not speak to a therapist or school counselor when they needed to.

The issue is worse for students in rural areas , in schools with limited financial resources, or who need culturally appropriate care such as bilingual mental health information.

But digital tools can connect youth to information about their mental health. For example, Dr. Ybarra said, the rise of telehealth and teletherapy since the pandemic has helped increase access for some.

Dr. Ybarra said that while technology (including social media) can have both positive and negative effects on mental health, it can also be a force for good. The nature of relationships has changed in the internet age, and connecting online is natural for adolescents . Options like crisis lines or online therapy can get help to teens quickly.

Multiple students said when they could not find resources from their schools or communities, they started their own. Some also said their experiences have inspired them to study mental health and treatments after high school.

One student said they began volunteering for a teen crisis hotline after their cousin used the same service for help. The student also joined a youth advisory group for their state governor’s office and offered help as a peer-to-peer counselor at their school.

“My passion towards becoming a researcher on psychiatric disorders is stronger than ever,” they wrote.

The way people talk about mental illness could also be better, one student wrote . They preferred the phrase “living” with a mental illness rather than “suffering” from one. This small change in language signals it’s possible for people with such conditions to live happy and fulfilling lives. This student also said their own school began marking mental health-related absences as excused and holding an annual mental health week to encourage open conversation.

It’s too early to tell what the long-term effects of the past few years will have on youth mental health. But Dr. Ybarra said some teens have become more resilient since the pandemic began.

“I don’t think this generation is doomed in any way,” she said. “Several kids have said [the pandemic] really gave them the time to better understand themselves, they better understand their sexuality … Other kids took on new hobbies, and they learned how to do new things. Maybe they gave themselves permission to not talk to that toxic person in their lives.” While there’s no denying the pandemic has been a stressful experience, Dr. Ybarra’s impression is that most teens have come out the other side with perspective and an ability to thrive.

“This is good news. It also means that we need to be diligent about identifying teens who continue to struggle and connect them to services,” she said.

If you think a teen is experiencing a mental health crisis, the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline is a national, 24/7 hotline that can connect you with a trained crisis counselor by phone or online chat. Call or text 988 to connect to a trained crisis counselor 24/7 or use the live online chat option. TTY users can contact the Lifeline via their preferred relay service or by dialing 711, then 988.

By the numbers

According to the centers for disease control and prevention, in 2021:.

- Asian (non-Hispanic): 64%

- Black (non-Hispanic): 55%

- Multiracial (non-Hispanic): 55%

- Hispanic or Latino: 42%

- American Indian/Alaska Native (non-Hispanic): 27%

- Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic): 55%

- White (non-Hispanic): 23%

- 18% of female high schoolers and 5% of male high schoolers experienced sexual violence, up from 15% and 4%, respectively, in 2017

- Up from 41% and 21%, respectively, in 2017

- 14% of LGBQ+ high schoolers and 7% of heterosexual students did not go to school because of safety concerns

*Data set did not account for gender identity, although previous research has shown that transgender youth experience more stigma and are more likely to have more suicidal thoughts or behaviors compared to their peers.

NIH-supported research on adolescent mental health

Greater engagement in gender-sexuality alliances (gsas) and gsa characteristics predict youth empowerment and reduced mental health concerns.

This study, supported by NIMHD, focused on the connections between sexual and gender minority youth’s involvement in extracurricular activities and their mental health. Researchers focused on gender-sexuality alliances (also sometimes called gay-straight alliances), which are school-based clubs to bring young people together to discuss shared issues or interests. Learn more about this study .

Understanding Bystanders for Self-Directed Violence Prevention: A Prospective National Study Highlighting Marginalized Youth and Young Adults

Self-directed violence refers to anything a person does intentionally that can cause injury or death to themselves. This study will examine the effectiveness of programs that train youth to be “active bystanders” and help those in danger of self-directed violence. Researchers will survey approximately 5,000 participants ages 13 to 22, recruited via social media, about the impacts of these bystander training programs in real-world situations. Read more about this study .

Strategic Framework for Addressing Youth Mental Health Disparities

This plan outlines research studies and other activities by NIMH, NICHD, and NIMHD to reduce mental health disparities among underserved and underrepresented youth by 2031. Some of the plan’s goals are to develop culturally appropriate mental health interventions for youth and parents and to research co-occurring mental illness among young people in groups that have been marginalized. Read more about the framework .

Alternative accessible version (pdf)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ; Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Supplement, Vol. 71, No. 3 ; CDC report shows concerning increases in sadness and exposure to violence among teen girls and LGBQ+ youth ; LGBQ+ Teens

May 16, 2023

You May Also Like

Teens and stress: When it’s more than worry

Stress—and sometimes feeling anxious—is a natural and normal experience for everyone, including children and teenagers. But when those feelings last...

Children and the pandemic: NIH explores mental health impact on American youth

COVID-19 has likely had some mental health impact on most of us, especially children and adolescents. The National Institutes of...

To help an anxious child, start with their parents

The best way to help children with an anxiety disorder may be to help their parents first, a new NIH-funded...

Trusted health information delivered to your inbox

Enter your email below

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 07 October 2021

Young people’s mental health is finally getting the attention it needs

You have full access to this article via your institution.

A kite-flying festival in a refugee camp near Syria’s border with Turkey. The event was organized in July 2020 to support the health and well-being of children fleeing violence in Syria. Credit: Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency/Getty

Worldwide, at least 13% of people between the ages of 10 and 19 live with a diagnosed mental-health disorder, according to the latest State of the World’s Children report , published this week by the United Nations children’s charity UNICEF. It’s the first time in the organization’s history that this flagship report has tackled the challenges in and opportunities for preventing and treating mental-health problems among young people. It reveals that adolescent mental health is highly complex, understudied — and underfunded. These findings are echoed in a parallel collection of review articles published this week in a number of Springer Nature journals.

Anxiety and depression constitute more than 40% of mental-health disorders among young people (those aged 10–19). UNICEF also reports that, worldwide, suicide is the fourth most-common cause of death (after road injuries, tuberculosis and interpersonal violence) among adolescents (aged 15–19). In eastern Europe and central Asia, suicide is the leading cause of death for young people in that age group — and it’s the second-highest cause in western Europe and North America.

Collection: Promoting youth mental health

Sadly, psychological distress among young people seems to be rising. One study found that rates of depression among a nationally representative sample of US adolescents (aged 12 to 17) increased from 8.5% of young adults to 13.2% between 2005 and 2017 1 . There’s also initial evidence that the coronavirus pandemic is exacerbating this trend in some countries. For example, in a nationwide study 2 from Iceland, adolescents (aged 13–18) reported significantly more symptoms of mental ill health during the pandemic than did their peers before it. And girls were more likely to experience these symptoms than were boys.

Although most mental-health disorders arise during adolescence, UNICEF says that only one-third of investment in mental-health research is targeted towards young people. Moreover, the research itself suffers from fragmentation — scientists involved tend to work inside some key disciplines, such as psychiatry, paediatrics, psychology and epidemiology, and the links between research and health-care services are often poor. This means that effective forms of prevention and treatment are limited, and lack a solid understanding of what works, in which context and why.

This week’s collection of review articles dives deep into the state of knowledge of interventions — those that work and those that don’t — for preventing and treating anxiety and depression in young people aged 14–24. In some of the projects, young people with lived experience of anxiety and depression were co-investigators, involved in both the design and implementation of the reviews, as well as in interpretation of the findings.

Quest for new therapies

Worldwide, the most common treatment for anxiety and depression is a class of drug called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which increase serotonin levels in the brain and are intended to enhance emotion and mood. But their modest efficacy and substantial side effects 3 have spurred the study of alternative physiological mechanisms that could be involved in youth depression and anxiety, so that new therapeutics can be developed.

Mental health: build predictive models to steer policy

For example, researchers have been investigating potential links between depression and inflammatory disorders — such as asthma, cardiovascular disease and inflammatory bowel disease. This is because, in many cases, adults with depression also experience such disorders. Moreover, there’s evidence that, in mice, changes to the gut microbiota during development reduce behaviours similar to those linked to anxiety and depression in people 4 . That suggests that targeting the gut microbiome during adolescence could be a promising avenue for reducing anxiety in young people. Kathrin Cohen Kadosh at the University of Surrey in Guildford, UK, and colleagues reviewed existing reports of interventions in which diets were changed to target the gut microbiome. These were found to have had minimal effect on youth anxiety 5 . However, the authors urge caution before such a conclusion can be confirmed, citing methodological limitations (including small sample sizes) among the studies they reviewed. They say the next crop of studies will need to involve larger-scale clinical trials.

By contrast, researchers have found that improving young people’s cognitive and interpersonal skills can be more effective in preventing and treating anxiety and depression under certain circumstances — although the reason for this is not known. For instance, a concept known as ‘decentring’ or ‘psychological distancing’ (that is, encouraging a person to adopt an objective perspective on negative thoughts and feelings) can help both to prevent and to alleviate depression and anxiety, report Marc Bennett at the University of Cambridge, UK, and colleagues 6 , although the underlying neurobiological mechanisms are unclear.

In addition, Alexander Daros at the Campbell Family Mental Health Institute in Toronto, Canada, and colleagues report a meta-analysis of 90 randomized controlled trials. They found that helping young people to improve their emotion-regulation skills, which are needed to control emotional responses to difficult situations, enables them to cope better with anxiety and depression 7 . However, it is still unclear whether better regulation of emotions is the cause or the effect of these improvements.

Co-production is essential

It’s uncommon — but increasingly seen as essential — that researchers working on treatments and interventions are directly involving young people who’ve experienced mental ill health. These young people need to be involved in all aspects of the research process, from conceptualizing to and designing a study, to conducting it and interpreting the results. Such an approach will lead to more-useful science, and will lessen the risk of developing irrelevant or inappropriate interventions.

Science careers and mental health

Two such young people are co-authors in a review from Karolin Krause at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Canada, and colleagues. The review explored whether training in problem solving helps to alleviate depressive symptoms 8 . The two youth partners, in turn, convened a panel of 12 other youth advisers, and together they provided input on shaping how the review of the evidence was carried out and on interpreting and contextualizing the findings. The study concluded that, although problem-solving training could help with personal challenges when combined with other treatments, it doesn’t on its own measurably reduce depressive symptoms.

The overarching message that emerges from these reviews is that there is no ‘silver bullet’ for preventing and treating anxiety and depression in young people — rather, prevention and treatment will need to rely on a combination of interventions that take into account individual needs and circumstances. Higher-quality evidence is also needed, such as large-scale trials using established protocols.

Along with the UNICEF report, the studies underscore the transformational part that funders must urgently play, and why researchers, clinicians and communities must work together on more studies that genuinely involve young people as co-investigators. Together, we can all do better to create a brighter, healthier future for a generation of young people facing more challenges than ever before.

Nature 598 , 235-236 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02690-5

Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E. & Binau, S. G. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 128 , 185–199 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Thorisdottir, I. E. et al. Lancet Psychiatr. 8 , 663–672 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Murphy, S. E. et al. Lancet Psychiatr. 8 , 824–835 (2021).

Murray, E. et al. Brain Behav. Immun. 81 , 198–212 (2019).

Cohen Kadosh, K. et al. Transl. Psychiatr. 11 , 352 (2021).

Bennett, M. P. et al. Transl Psychiatr. 11 , 288 (2021).

Daros, A. R. et al. Nature Hum. Behav . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01191-9 (2021).

Krause, K. R. et al. BMC Psychiatr. 21 , 397 (2021).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Psychiatric disorders

- Public health

Targeting RNA opens therapeutic avenues for Timothy syndrome

News & Views 24 APR 24

The rise of eco-anxiety: scientists wake up to the mental-health toll of climate change

News Feature 10 APR 24

Use fines from EU social-media act to fund research on adolescent mental health

Correspondence 09 APR 24

We need more-nuanced approaches to exploring sex and gender in research

Comment 01 MAY 24

Bird flu virus has been spreading among US cows for months, RNA reveals

News 27 APR 24

WHO redefines airborne transmission: what does that mean for future pandemics?

News 24 APR 24

How to meet Africa’s grand challenges with African know-how

World View 01 MAY 24

Support communities that will lose out in the energy transition

Editorial 01 MAY 24

Climate-targets group should rescind its endorsement of carbon offsets

Correspondence 30 APR 24

Faculty Positions in Neurobiology, Westlake University

We seek exceptional candidates to lead vigorous independent research programs working in any area of neurobiology.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

School of Life Sciences, Westlake University

Seeking Global Talents, the International School of Medicine, Zhejiang University

Welcome to apply for all levels of professors based at the International School of Medicine, Zhejiang University.

Yiwu, Zhejiang, China

International School of Medicine, Zhejiang University

Assistant, Associate, or Full Professor

Athens, Georgia

University of Georgia

Associate Professor - Synthetic Biology

Position Summary We seek an Associate Professor in the department of Synthetic Biology (jcvi.org/research/synthetic-biology). We invite applicatio...

Rockville, Maryland

J. Craig Venter Institute

Associate or Senior Editor (microbial genetics, evolution, and epidemiology) Nature Communications

Job Title: Associate or Senior Editor (microbial genetics, evolution, and epidemiology), Nature Communications Locations: London, New York, Philade...

New York (US)

Springer Nature Ltd

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Being a teen comes with exciting milestones that double as challenges – like becoming independent, navigating high school and forming new relationships. For all the highs that come with getting a driver’s license or acing that difficult test, there are lows that come with growing up in a rapidly changing world being shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic, social media and distance learning.

Teens’ brains are growing and developing, and the ways they process their experiences and spend their time are crucial to their development. Each great experience and every embarrassing moment can impact their mental health.

Sometimes a mood is about more than just being lonely or angry or frustrated.

Mental health challenges are different than situational sadness or fatigue. They’re more severe and longer-lasting, and they can have a large impact on daily life. Some common mental health challenges are anxiety, depression, eating disorders, substance use, and experiencing trauma. They can affect a teen’s usual way of thinking, feeling or acting, and interfere with daily life.

Adding to the urgency: Mental health challenges among teens are not uncommon. Up to 75% of mental health challenges emerge during adolescence, and according to the Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) curriculum, one in five teens has had a serious mental health disorder at some point in their life.

Not every mental health challenge will be diagnosed as a mental disorder, but every challenge should be taken seriously.

A mental health challenge left unchecked can become a more serious problem that also impacts physical health — think of how substance use, and changes in sleep patterns and eating habits affect the body as well as the mind. Signs of fatigue, withdrawing socially or changes in mood may point to an emerging mental health challenge like a depressive or substance use disorder.

As teens mature, they begin spending more time with their friends, gain a sense of identity and purpose, and become more independent. All of these experiences are crucial for their development, and a mental health challenge can disrupt or complicate that development. Depending on the severity of the mental health challenge, the effects can last long into adulthood if left unaddressed.

How do we address teens’ mental health?

Teens need tools to talk about what’s going on with them, and they need tools for when their friends reach out to them. Research shows that teens are more likely to talk to their friends than an adult about troubles they’re facing.

That’s why it’s important to talk to teens about the challenges they may deal with as they grow up and navigate young adulthood. They need to know it’s OK to sometimes feel sad, angry, alone, and frustrated. But persistent problems may be pointing to something else, and it is crucial to be able to recognize early warning signs so teens can get appropriate help in a timely manner. teen Mental Health First Aid teaches high school students in grades 10-12 how to identify, understand and respond to signs of a mental health problem or crisis among their friends — and how to bring in a trusted adult when it’s appropriate and necessary. With proper care and treatment, many teens with mental health or substance use challenges can recover. The first step is getting help.

Learn more about teen Mental Health First Aid by watching this video and checking out our blog . Your school or youth-serving organization can also apply to bring this training to your community.

teen Mental Health First Aid is run by the National Council for Mental Wellbeing and supported by Lady Gaga’s Born This Way Foundation.

Resource Guide:

- Mental Health First Aid USA. (2020). teen Mental Health First Aid USA: A manual for young people in 10 th -12 th grade helping their friends. Washington, DC: National Council for Mental Wellbeing.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2020). The Teen Brain: 7 Things to Know. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/the-teen-brain-7-things-to-know/index.shtml.

Get the latest MHFA blogs, news and updates delivered directly to your inbox so you never miss a post.

Share and help spread the word.

Related stories.

No related posts.

- Open access

- Published: 14 September 2023

Children and youth’s perceptions of mental health—a scoping review of qualitative studies

- Linda Beckman 1 , 2 ,

- Sven Hassler 1 &

- Lisa Hellström 3

BMC Psychiatry volume 23 , Article number: 669 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5487 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

Recent research indicates that understanding how children and youth perceive mental health, how it is manifests, and where the line between mental health issues and everyday challenges should be drawn, is complex and varied. Consequently, it is important to investigate how children and youth perceive and communicate about mental health. With this in mind, our goal is to synthesize the literature on how children and youth (ages 10—25) perceive and conceptualize mental health.

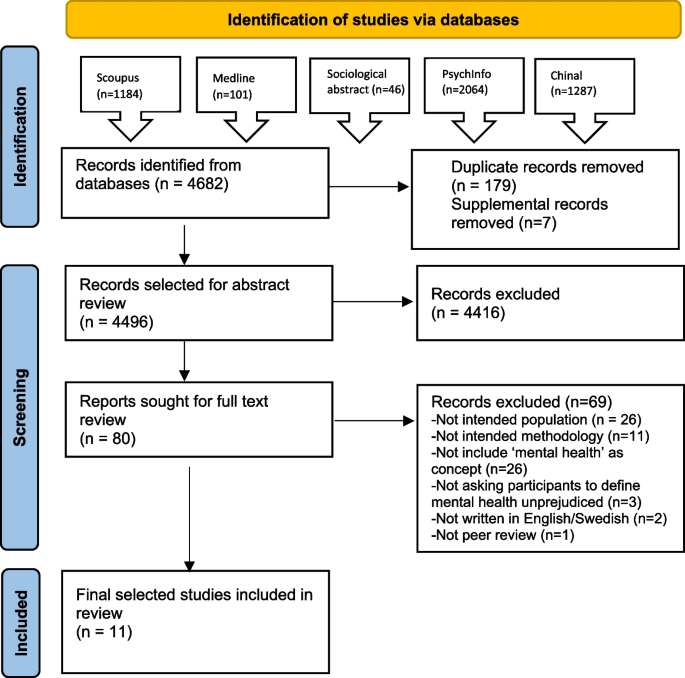

We conducted a preliminary search to identify the keywords, employing a search strategy across electronic databases including Medline, Scopus, CINAHL, PsychInfo, Sociological abstracts and Google Scholar. The search encompassed the period from September 20, 2021, to September 30, 2021. This effort yielded 11 eligible studies. Our scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR Checklist.

As various aspects of uncertainty in understanding of mental health have emerged, the results indicate the importance of establishing a shared language concerning mental health. This is essential for clarifying the distinctions between everyday challenges and issues that require treatment.

We require a language that can direct children, parents, school personnel and professionals toward appropriate support and aid in formulating health interventions. Additionally, it holds significance to promote an understanding of the positive aspects of mental health. This emphasis should extend to the competence development of school personnel, enabling them to integrate insights about mental well-being into routine interactions with young individuals. This approach could empower children and youth to acquire the understanding that mental health is not a static condition but rather something that can be enhanced or, at the very least, maintained.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In Western society, the prevalence of mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety [ 1 ], as well as recurring psychosomatic health complaints [ 2 ], has increased from the 1980s and 2000s. However, whether these changes in adolescent mental health are actual trends or influenced by alterations in how adolescents perceive, talk about, and report their mental well-being remains ambiguous [ 1 ]. Despite an increase in self-reported mental health problems, levels of mental well-being have remained stable, and severe psychiatric diagnoses have not significantly risen [ 3 , 4 ]. Recent research indicates that understanding how children and youth grasp mental health, its manifestations, and the demarcation between mental health issues and everyday challenges is intricate and diverse. Wickström and Kvist Lindholm [ 5 ] show that problems such as feeling low and nervous are considered deep-seated issues among some adolescents, while others refer to them as everyday challenges. Meanwhile, adolescents in Hellström and Beckman [ 6 ] describe mental health problems as something mainstream, experienced by everyone at some point. Furthermore, Hermann et al. [ 7 ] point out that adolescents can distinguish between positive health and mental health problems. This indicates their understanding of the complexity and holistic nature of mental health and mental health issues. It is plausible that misunderstandings and devaluations of mental health and illness concepts may increase self-reported mental health problems and provide contradictory results when the understanding of mental health is studied. In a previous review on how children and young people perceive the concept of “health,” four major themes have been suggested: health practices, not being sick, feeling good, and being able to do the desired and required activities [ 8 ]. In a study involving 8–11 year olds, children framed both biomedical and holistic perspectives of health [ 9 ]. Regarding the concept of “illness,” themes such as somatic feeling states, functional and affective states [ 10 , 11 ], as well as processes of contagion and contamination, have emerged [ 9 ]. Older age strongly predicts nuances in conceptualizations of health and illness [ 10 , 11 , 12 ].

As the current definitions of mental health and mental illness do not seem to have been successful in guiding how these concepts are perceived, literature has emphasized the importance of understanding individuals’ ideas of health and illness [ 9 , 13 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) broadly defines mental health as a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively and fruitfully and make a contribution to his or her community [ 14 ] capturing only positive aspects. According to The American Psychology Association [ 15 ], mental illness includes several conditions with varying severity and duration, from milder and transient disorders to long-term conditions affecting daily function. The term can thus cover everything from mild anxiety or depression to severe psychiatric conditions that should be treated by healthcare professionals. As a guide for individual experience, such a definition becomes insufficient in distinguishing mental illness from ordinary emotional expressions. According to the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare et al. [ 16 ], mental health works as an umbrella term for both mental well-being and mental illness : Mental well-being is about being able to handle life's difficulties, feeling satisfied with life, having good social relationships, as well as being able to feel pleasure, desire, and happiness. Mental illness includes both mild to moderate mental health problems and psychiatric conditions . Mild to moderate mental health problems are common and are often reactions to events or situations in life, e.g., worry, feeling low, and sleep difficulties.

It has been argued that increased knowledge of the nature of mental illness can help individuals to cope with the situation and improve their well-being. Increased knowledge about mental illness, how to prevent mental illness and help-seeking behavior has been conceptualized as “mental health literacy” (MHL) [ 17 ], a construct that has emerged from “health literacy” [ 18 ]. Previous literature supports the idea that positive MHL is associated with mental well-being among adolescents [ 19 ]. Conversely, studies point out that low levels of MHL are associated with depression [ 20 ]. Some gender differences have been acknowledged in adolescents, with boys scoring lower than girls on MHL measures [ 20 ] and a social gradient including a positive relationship between MHL and perceived good financial position [ 19 ] or a higher socio-economic status [ 21 ].

While MHL stresses knowledge about signs and treatment of mental illness [ 22 ], the concern from a social constructivist approach would be the conceptualization of mental illness and how it is shaped by society and the thoughts, feelings, and actions of its members [ 23 ]. Studies on the social construction of anxiety and depression through media discourses have shown that language is at the heart of these processes, and that language both constructs the world as people perceive it but also forms the conditions under which an experience is likely to be construed [ 24 , 25 ]. Considering experience as linguistically inflected, the constructionist approach offers an analytical tool to understand the conceptualization of mental illness and to distinguish mental illness from everyday challenges. The essence of mental health is therefore suggested to be psychological constructions identified through how adolescents and society at large perceive, talk about, and report mental health and how that, in turn, feeds a continuous process of conceptual re-construction or adaptation [ 26 ]. Considering experience as linguistically inflected, the constructionist approach could then offer an analytical tool to understand the potential influence of everyday challenges in the conceptualization of mental health.

Research investigating how children and youth perceive and communicate mental health is essential to understand the current rise of reported mental health problems [ 5 ]. Health promotion initiatives are more likely to be successful if they take people’s understanding, beliefs, and concerns into account [ 27 , 28 ]. As far as we know, no review has mapped the literature to explore children’s and youths’ perceptions of mental health and mental illness. Based on previous literature, age, gender, and socioeconomic status seem to influence children's and youths’ knowledge and experiences of mental health [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]; therefore, we aim to analyze these perspectives too. From a social constructivist perspective, experience is linguistically inflected [ 26 ]; hence illuminating the conditions under which a perception of health is formed is of interest.

Therefore, we aim to study the literature on how children and youth (ages 10—25) perceive and conceptualize mental health, and the specific research questions are:

What aspects are most salient in children’s and youths’ perceptions of mental health?

What concepts do children and youth associate with mental health?

In what way are children's and youth’s perceptions of mental health dependent on gender, age, and socioeconomic factors?

Literature search

A scoping review is a review that aims to provide a snapshot of the research that is published within a specific subject area. The purpose is to offer an overview and, on a more comprehensive level, to distinguish central themes compared to a systematic review. We chose to conduct a scoping review since our aim was to clarify the key concepts of mental health in the literature and to identify specific characteristics and concepts surrounding mental health [ 29 , 30 ]. Our scoping review was conducted following the PRISMA-ScR Checklist [ 31 ]. Two authors (L.B and L.H) searched and screened the eligible articles. In the first step, titles and abstracts were screened. If the study included relevant data, the full article was read to determine if it met the eligibility criteria. Articles were excluded if they did not fulfill all the eligibility criteria. Any uncertainties were discussed among L.B. and L.H., and the third author, S.H., and were carefully assessed before making an inclusion or exclusion decision. The software Picoportal was employed for data management. Figure 1 illustrates a flowchart of data inclusion.

PRISMA flow diagram outlining the search process

Eligibility criteria

We incorporated studies involving children and youth aged 10 to 25 years. This age range was chosen to encompass early puberty through young adulthood, a significant developmental period for young individuals in terms of comprehending mental health. Participants were required not to have undergone interviews due to chronic illness, learning disabilities (e.g., mental health linked to a cancer diagnosis), or immigrant status.

Studies conducted in clinical settings were excluded. For the purpose of comparing results under similar conditions, we specifically opted for studies carried out in Western countries .

Given that this review adopts a moderately constructionist approach, intentionally allowing for the exploration of how both young participants and society in general perceive and discuss mental health and how this process contributes to ongoing conceptual re-construction, the emphasis was placed on identifying articles in which participants themselves defined or attributed meaning to mental health and related concepts like mental illness. The criterion of selecting studies adopting an inductive approach to capture the perspectives of the young participants resulted in the exclusion of numerous studies that more overtly applied established concepts to young respondents [ 32 ].

Information sources

We utilized electronic databases and reached out to study authors if the article was not accessible online. Peer-reviewed articles were exclusively included, thereby excluding conference abstracts due to their perceived lack of relevance in addressing the review questions. Only research in English was taken into account. Publication years across all periods were encompassed in the search.

Search strategy

Studies concerning children’s and youths’ perceptions of mental health were published across a range of scientific journals, such as those within psychiatry, psychology, social work, education, and mental health. Therefore, several databases were taken into account, including Medline, Scopus, CINAHL, PsychInfo, Sociological abstracts, and Google Scholar, spanning from inception on September 20, 2021 to September 30, 2021. We involved a university librarian from the start in the search process. The combinations of search terms are displayed in Table 1 .

Quality assessment

We employed the Quality methods for the development of National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE) public health guidance [ 33 ] to evaluate the quality of the studies included. The checklist is based on checklists from Spencer et al. [ 34 ], Public Health Resource Unit (PHRU) [ 26 , 35 ], and the North Thames Research Appraisal Group (NTRAG) [ 36 ] (Refer to S2 for checklist). Eight studies were assigned two plusses, and three studies received one plus. The studies with lower grades generally lacked sufficient descriptions of the researcher’s role, context reporting, and ethical reporting. No study was excluded in this stage.

Data extraction and analysis

We employed a data extraction form that encompassed several key characteristics, including author(s), year, journal, country, details about method/design, participants and socioeconomics, aim, and main results (Table 2 ). The collected data were analyzed and synthesized using the thematic synthesis approach of Thomas and Harden [ 37 ]. This approach encompassed all text categorized as 'results' or 'findings' in study reports – which sometimes included abstracts, although the presentation wasn’t always consistent throughout the text. The size of the study reports ranged from a few sentences to a single page. The synthesis occurred through three interrelated stages that partially overlapped: coding of the findings from primary studies on a line-by-line basis, organization of these 'free codes' into interconnected areas to construct 'descriptive' themes, and the formation of 'analytical' themes.

The objective of this scoping review has been to investigate the literature concerning how children and youth (ages 10—25) conceptualize and perceive mental health. Based on the established inclusion- and exclusion criteria, a total of 11 articles were included representing the United Kingdom ( n = 6), Australia ( n = 3), and Sweden ( n = 2) and were published between 2002 and 2020. Among these, two studies involved university students, while nine incorporated students from compulsory schools.

Salient aspects of children and youth’ perceptions of mental health

Based on the results of the included articles, salient aspects of children’s and youths’ understandings revealed uncertainties about mental health in various ways. This uncertainty emerged as conflicting perceptions, uncertainty about the concept of mental health, and uncertainty regarding where to distinguish between mild to moderate mental health problems and everyday stressors or challenges.

One uncertainty was associated with conflicting perceptions that mental health might be interpreted differently among children and youths, depending on whether it relates to their own mental health or someone else's mental health status. Chisholm et al. [ 42 ] presented this as distinctions being made between ‘them and us’ and between ‘being born with it’. Mental health and mental illness were perceived as a continuum that rather developed’, and distinctions were drawn between ‘crazy’ and ‘diagnosed.’ Participants established strong associations between the term mental illness and derogatory terms like ‘crazy,’ linking extreme symptoms of mental illness with others. However, their attitude was less stigmatizing when it came to individual diagnoses, reflecting a more insightful and empathetic understanding of the adverse impacts of stress based on their personal realities and experiences. Despite the initial reactions reflecting negative stereotypes, further discussion revealed that this did not accurately represent a deeper comprehension of mental health and mental illness.

There was also uncertainty about the concept of mental health , as it was not always clearly understood among the participating youth. Some participants were unable to define mental health, often confusing it with mental illness [ 28 ]. Others simply stated that they did not understand the term, as in O’Reilly [ 44 ]. Additionally, uncertainty was expressed regarding whether mental health was a positive or negative concept [ 27 , 28 , 40 , 44 ], and participants associated mental health with mental illness despite being asked about mental health [ 28 ]. One quote from a grade 9 student illustrates this: “ Interviewer: Can mental health be positive as well? Informant: No, it’s mental” [ 44 ]. In Laidlaw et al. [ 46 ], with participants ranging from 18—22 years of age, most considered mental health distinctly different from and more clinical than mental well-being. However, Roose et al. [ 38 ], for example, the authors discovered a more multifaceted understanding of mental health, encompassing emotions, thoughts, and behavior. In Molenaar et al.[ 45 ], mental health was highlighted as a crucial aspect of health overall. In Chisholm et al. [ 42 ], the older age groups discussed mental health in a more positive sense when they considered themselves or people they knew, relating mental health to emotional well-being. Connected to the uncertainty in defining the concept of mental health was the uncertainty in identifying those with good or poor mental health. Due to the lack of visible proof, children and youths might doubt their peers’ reports of mental illness, wondering if they were pretending or exaggerating their symptoms [ 27 ].

A final uncertainty that emerged was difficulties in drawing the line between psychiatric conditions and mild to moderate mental health problems and everyday stressors or challenges . Perre et al. [ 43 ] described how the participants in their study were uncertain about the meaning of mental illness and mental health issues. While some linked depression to psychosis, others related it to simply ‘feeling down.’ However, most participants indicated that, in contrast to transient feelings of sadness, depression is a recurring concern. Furthermore, the duration of feeling depressed and particularly a loss of interest in socializing was seen as appropriate criteria for distinguishing between ‘feeling down’ and ‘clinical depression.’ Since feelings of anxiety, nervousness, and apprehension are common experiences among children and youth, defining anxiety as an illness as opposed to an everyday stressor was more challenging [ 43 ].

Terms used to conceptualize mental health

When children and youth were asked about mental health, they sometimes used neutral terms such as thoughts and emotions or a general ‘vibe’ [ 27 ], and some described it as ‘peace of mind’ and being able to balance your emotions [ 38 ]. The notion of mental health was also found to be closely linked with rationality and the idea of normality, although, according to the young people, Armstrong et al. [ 28 ], there was no consensus about what ‘normal’ meant. Positive aspects of mental health were described by the participants as good self-esteem, confidence [ 40 ], happiness [ 39 , 43 ], optimism, resilience, extraversion and intelligence [ 27 ], energy [ 43 ], balance, harmony [ 39 , 43 ], good brain, emotional and physical functioning and development, and a clear idea of who they are [ 27 , 41 ]. It also included a feeling of being a good person, feeling liked and loved by your parents, social support, and having people to talk with [ 27 , 39 ], as well as being able to fit in with the world socially and positive peer relationships [ 41 ], according to the children and youths, mental health includes aspects related to individuals (individual factors) as well as to people in their surroundings (relationships). Regarding mental illness, participants defined it as stress and humiliation [ 40 ], psychological distress, traumatic experiences, mental disorders, pessimism, and learning disabilities [ 27 ]. Also, in contrast to the normality concept describing mental health, mental illness was described as somehow ‘not normal’ or ‘different’ in Chisholm et al. [ 42 ].

Depression and bipolar disorder were the most often mentioned mental illnesses [ 27 ]. The inability to balance emotions was seen as negative for mental health, for example, not being able to set aside unhappiness, lying to cover up sadness, and being unable to concentrate on schoolwork [ 38 ]. The understanding of mental illness also included feelings of fear and anxiety [ 42 ]. Other participants [ 46 ] indicated that mental health is distinctly different from, and more clinical than, mental well-being. In that sense, mental health was described using reinforcing terms such as ‘serious’ and ‘clinical,’ being more closely connected to mental illness, whereas mental well-being was described as the absence of illness, feeling happy, confident, being able to function and cope with life’s demands and feeling secure. Among younger participants, a more varied and vague understanding of mental health was shown, framing it as things happening in the brain or in terms of specific conditions like schizophrenia [ 44 ].

Gender, age, socioeconomic status

Only one study had a gender theoretical perspective [ 40 ], but the focus of this perspective concerned gender differences in what influences mental health more than the conceptualization of mental health. According to Johansson et al.[ 39 ], older girls expressed deeper negative emotions (e.g., described feelings of lack of meaning and hope in various ways) than older boys and younger children.

Several of the included studies noticed differences in age, where younger participants had difficulty understanding the concept of mental health [ 39 , 44 ], while older participants used more words to explain it [ 39 ]. Furthermore, older participants seemed to view mental health and mental illness as a continuum, with mental illness at one end of the continuum and mental well-being at the other end [ 42 , 46 ].

Socioeconomic status

The role of socioeconomic status was only discussed by Armstrong et al. [ 28 ], finding that young people from schools in the most deprived and rural areas experienced more difficulties defining the term mental health compared to those from a less deprived area.

This scoping review aimed to map children's and youth’s perceptions and conceptualizations of mental health. Our main findings indicate that the concept of mental health is surrounded by uncertainty. This raises the question of where this uncertainty stems from and what it symbolizes. From our perspective, this uncertainty can be understood from two angles. Firstly, the young participants in the different studies show no clear and common understanding of mental health; they express uncertainty about the meaning of the concept and where to draw the line between life experiences and psychiatric conditions. Secondly, uncertainty exists regarding how to apply these concepts in research, making it challenging to interpret and compare research results. The shift from a positivistic understanding of mental health as an objective condition to a more subjective inner experience has left the conceptualization open ranging from a pathological phenomenon to a normal and common human experience [ 47 ]. A dilemma that results in a lack of reliability that mirrors the elusive nature of the concept of mental health from both a respondent and a scientific perspective.

“Happy” was commonly used to describe mental health, whereas "unhappy" was used to describe mental illness. The meaning of happiness for mental health has been acknowledged in the literature, and according to Layard et al. [ 48 ], mental illness is one of the main causes of unhappiness, and happiness is the ultimate goal in human life. Layard et al. [ 48 ] suggest that schools and workplaces need to raise more awareness of mental health and strive to improve happiness to promote mental health and prevent mental illness. On the other hand, being able to experience and express different emotions could also be considered a part of mental health. The notion of normality also surfaced in some studies [ 38 ], understanding mental health as being emotionally balanced or normal or that mental illness was not normal [ 42 ]. To consider mental illness in terms of social norms and behavior followed with the sociological alternative to the medical model that was introduced in the sixties portraying mental illness more as socially unacceptable behavior that is successfully labeled by others as being deviant. Although our results did not indicate any perceptions of what ‘normal’ meant [ 28 ], one crucial starting point to the understanding of mental health among adolescents should be to delineate what constitutes normal functioning [ 23 ]. Children and youths’ understanding of mental illness seems to a large extent, to be on the same continuum as a normality rather than representing a medicalization of deviant behavior and a disjuncture with normality [ 49 ].

Concerning gender, it seemed that girls had an easier time conceptualizing mental health than boys. This could be due to the fact that girls mature verbally faster than boys [ 50 ], but also that girls, to a larger extent, share feelings and problems together compared to boys [ 51 ]. However, according to Johansson et al. [ 39 ], the differences in conceptualizations of mental health seem to be more age-related than gender-related. This could be due to the fact that older children have a more complex view of mental health compared to younger children.. Not surprisingly, the older the children and youth were, the more complex the ability to conceptualize mental health becomes. Only one study reported socioeconomic differences in conceptualizations of mental health [ 28 ]. This could be linked to mental health literacy (MHL) [ 18 ], i.e., knowledge about mental illness, how to prevent mental illness, and help-seeking behavior. Research has shown that disadvantaged social and socioeconomic conditions are associated with low MHL, that is, people with low SES tends to know less about symptoms and prevalence of different mental health problems [ 19 , 21 ]. The perception and conceptualizations of mental health are, as we consider, strongly related to knowledge and beliefs about mental health, and according to von dem Knesebeck et al. [ 52 ] linked primarily to SES through level of education.

Chisholm et al. [ 42 ] found that the initial reactions from participants related to negative stereotypes, but further discussion revealed that the participants had more refined knowledge than at first glance. This illuminates the importance of talking to children and helping them verbalize their feelings, in many respects complex and diversified understanding of mental health. It is plausible that misunderstandings and devaluations of mental health and mental illness may increase self-reported mental health problems [ 5 ], as well as decrease them, preventing children and youth from seeking help. Therefore, increased knowledge of the nature of mental health can help individual cope with the situations and improve their mental well-being. Finding ways to incorporate discussions about mental well-being, mental health, and mental illness in schools could be the first step to decreasing the existing uncertainties about mental health. Experiencing feelings of sadness, anger, or upset from time to time is a natural part of life, and these emotions are not harmful and do not necessarily indicate mental illness [ 5 , 6 ]. Adolescents may have an understanding of the complexity of mental health despite using simplified language but may need guidance on how to communicate their feelings and how to manage everyday challenges and normal strains in life [ 7 ].

With the aim of gaining a better understanding of how mental health is perceived among children and youth, this study has highlighted the concept’s uncertainty. Children and youth reveal a variety of understandings, from diagnoses of serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia to moods and different types of behaviors. Is there only one way of understanding mental health, and is it reasonable to believe that we can reach a consensus? Judging by the questions asked, researchers also seem to have different ideas on what to incorporate into the concept of mental health — the researchers behind the present study included. The difficulties in differentiating challenges being part of everyday life with mental health issues need to be paid closer attention to and seems to be symptomatic with the lack of clarity of the concepts.

A constructivist approach would argue that the language of mental health has changed over time and thus influence how adolescents, as well as society at large, perceive, talk about, and report their mental health [ 26 ]. The re-construction or adaptation of concepts could explain why children and youth re struggling with the meaning of mental health and that mental health often is used interchangeably with mental illness. Mental health, rather than being an umbrella term, then represents a continuum with a positive and a negative end, at least among older adolescents. But as mental health according to this review also incorporates subjective expressions of moods and feelings, the reconstruction seems to have shaped it into a multidimensional concept, representing a horizontal continuum of positive and negative mental health and a vertical continuum of positive and negative well-being, similar to the health cross by Tudor [ 53 ] referred to in Laidlaw et al. [ 46 ] A multidimensional understanding of mental health constructs also incorporates evidence from interventions aimed at reducing mental health stigma among adolescents, where attitudes and beliefs as well as emotional responses towards mental health are targeted [ 54 ].

The contextual understanding of mental health, whether it is perceived in positive terms or negative, started with doctors and psychiatrists viewing it as representing a deviation from the normal. A perspective that has long been challenged by health workers, academics and professionals wanting to communicate mental health as a positive concept, as a resource to be promoted and supported. In order to find a common ground for communicating all aspects and dimensions of mental health and its conceptual constituents, it is suggested that we first must understand the subjective meaning ascribed to the use of the term [ 26 ]. This line of thought follows a social-constructionist approach viewing mental health as a concept that has transitioned from representing objective mental descriptions of conditions to personal subjective experiences. Shifting from being conceptualized as a pathological phenomenon to a normal and common human experience [ 47 ]. That a common understanding of mental health can be challenged by the healthcare services tradition and regulation for using diagnosis has been shown in a study of adolescents’ perspectives on shared decision-making in mental healthcare [ 55 ]. A practice perceived as labeling by the adolescents, indicating that steps towards a common understanding of mental health needs to be taken from several directions [ 55 ]. In a constructionist investigation to distinguish everyday challenges from mental health problems, instead of asking the question, “What is mental health?” we should perhaps ask, “How is the word ‘mental health’ used, and in what context and type of mental health episode?” [ 26 ]. This is an area for future studies to explore.

Methodological considerations

The first limitation we want to acknowledge, as for any scoping review, is that the results are limited by the search terms included in the database searches. However, by conducting the searches with the help of an experienced librarian we have taken precautions to make the searches as inclusive as possible. The second limitation concerns the lack of homogeneous, or any results at all, according to different age groups, gender, socioeconomic status, and year when the study was conducted. It is well understood that age is a significant determinant in an individual’s conceptualization of more abstract phenomena such as mental health. Some of the studies approached only one age group but most included a wide age range, making it difficult to say anything specific about a particular age. Similar concerns are valid for gender. Regarding socioeconomic status, only one study reported this as a finding. However, this could be an outcome of the choice of methods we had — i.e., qualitative methods, where the aim seldom is to investigate differences between groups and the sample is often supposed to be a variety. It could also depend on the relatively small number of participants that are often used in focus groups of individual interviews- there are not enough participants to compare groups based on gender or socioeconomic status. Finally, we chose studies from countries that could be viewed as having similar development and perspective on mental health among adolescents. Despite this, cultural differences likely account for many youths’ conceptualizations of mental health. According to Meldahl et al. [ 56 ], adolescents’ perspectives on mental health are affected by a range of factors related to cultural identity, such as ethnicity, race, peer and family influence, religious and political views, for example. We would also like to add organizational cultures, such as the culture of the school and how schools work with mental health and related concepts [ 56 ].

Conclusions and implications

Based on our results, we argue that there is a need to establish a common language for discussing mental health. This common language would enable better communication between adults and children and youth, ensuring that the content of the words used to describe mental health is unambiguous and clear. In this endeavor, it is essential to actively listen to the voices of children and youth, as their perspectives will provide us with clearer understanding of the experiences of being young in today’s world. Another way to develop a common language around mental health is through mental health education. A common language based on children’s and youth’s perspectives can guide school personnel, professionals, and parents when discussing and planning health interventions and mental health education. Achieving a common understanding through mental health education of adults and youth could also help clarify the boundaries between everyday challenges and problems needing treatment. It is further important to raise awareness of the positive aspect of mental health—that is, knowledge of what makes us flourish mentally should be more clearly emphasized in teaching our children and youth about life. It should also be emphasized in competence development for school personnel so that we can incorporate knowledge about mental well-being in everyday meetings with children and youth. In that way, we could help children and youth develop knowledge that mental health could be improved or at least maintained and not a static condition.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Twenge JM, Joiner TE, Rogers ML, Martin GN. Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6(1):3–17.

Article Google Scholar

Potrebny T, Wiium N, Lundegård MM-I. Temporal trends in adolescents’ self-reported psychosomatic health complaints from 1980–2016: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS one. 2017;12(11):e0188374. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188374 . [published Online First: Epub Date]|.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Petersen S, Bergström E, Cederblad M, et al. Barns och ungdomars psykiska hälsa i Sverige. En systematisk litteraturöversikt med tonvikt på förändringar över tid. (The mental health of children and young people in Sweden. A systematic literature review with an emphasis on changes over time). Stockholm: Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien; 2010.

Google Scholar

Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Ferrari AJ, Norman RE, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Challenging the myth of an “epidemic” of common mental disorders: trends in the global prevalence of anxiety and depression between 1990 and 2010. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(6):506–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22230 . [published Online First: Epub Date]|.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Wickström A, Kvist LS. Young people’s perspectives on the symptoms asked for in the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children survey. Childhood. 2020;27(4):450–67.

Hellström L, Beckman L. Life Challenges and Barriers to Help Seeking: Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Voices of Mental Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24):13101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413101 . [published Online First: Epub Date]|.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hermann V, Durbeej N, Karlsson AC, Sarkadi A. ‘Feeling down one evening doesn’t count as having mental health problems’—Swedish adolescents’ conceptual views of mental health. J Adv Nurs. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15496 . [published Online First: Epub Date]|.

Boruchovitch E, Mednick BR. The meaning of health and illness: some considerations for health psychology. Psico-USF. 2002;7:175–83.

Piko BF, Bak J. Children’s perceptions of health and illness: images and lay concepts in preadolescence. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(5):643–53.

Millstein SG, Irwin CE. Concepts of health and illness: different constructs or variations on a theme? Health Psychol. 1987;6(6):515.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Campbell JD. Illness is a point of view: the development of children's concepts of illness. Child Dev. 1975;46(1):92–100.

Mouratidi P-S, Bonoti F, Leondari A. Children’s perceptions of illness and health: An analysis of drawings. Health Educ J. 2016;75(4):434–47.

Julia L. Lay experiences of health and illness: past research and future agendas. Sociol Health Illn. 2003;25(3):23–40.

World Health Organization. Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice (Summary Report). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42940 .

American Psychiatric Association. What is mental illness?. Secondary What is mental illness? 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mentalillness .

National board of health and welfare TSAoLAaRatSAfHTA, Assessment of Social Services. What is mental health and mental illness? Secondary What is mental health and mental illness? 2022. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/kunskapsstod-och-regler/omraden/psykisk-ohalsa/vad-menas-med-psykisk-halsa-och-ohalsa/ .

Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. “Mental health literacy”: a survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust. 1997;166(4):182–6.

Kutcher S, Wei Y, Coniglio C. Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(3):154–8.

Bjørnsen HN, Espnes GA, Eilertsen M-EB, Ringdal R, Moksnes UK. The relationship between positive mental health literacy and mental well-being among adolescents: implications for school health services. J Sch Nurs. 2019;35(2):107–16.

Lam LT. Mental health literacy and mental health status in adolescents: a population-based survey. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2014;8:1–8.

Campos L, Dias P, Duarte A, Veiga E, Dias CC, Palha F. Is it possible to “find space for mental health” in young people? Effectiveness of a school-based mental health literacy promotion program. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1426.

Mårtensson L, Hensing G. Health literacy–a heterogeneous phenomenon: a literature review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26(1):151–60.

Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, Bierman A. The sociology of mental health: Surveying the field. Handbook of the sociology of mental health: Springer; 2013. p. 1–19.

Book Google Scholar

Johansson EE, Bengs C, Danielsson U, Lehti A, Hammarström A. Gaps between patients, media, and academic medicine in discourses on gender and depression: a metasynthesis. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(5):633–44.

Dowbiggin IR. High anxieties: The social construction of anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(7):429–36.

Stein JY, Tuval-Mashiach R. The social construction of loneliness: an integrative conceptualization. J Constr Psychol. 2015;28(3):210–27.

Teng E, Crabb S, Winefield H, Venning A. Crying wolf? Australian adolescents’ perceptions of the ambiguity of visible indicators of mental health and authenticity of mental illness. Qual Res Psychol. 2017;14(2):171–99.

Armstrong C, Hill M, Secker J. Young people’s perceptions of mental health. Child Soc. 2000;14(1):60–72.

Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:1–7.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2004;169(7):467–73.

Järvensivu T, Törnroos J-Å. Case study research with moderate constructionism: conceptualization and practical illustration. Ind Mark Manage. 2010;39(1):100–8.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance (third edition). Process and methods PMG4. 2012. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/introduction .

Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J, Dillon L. Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence. Cabinet Office. 2004. Available at: https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/Spencer-Quality-in-qualitative-evaluation.pdf .

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP qualitative research checklist: 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. 2013. Available at: https://www.casp-uk.net/#!casp-tools-checklists/c18f8 .

North Thames Research Appraisal Group (NTRAG). Critical review form for reading a paper describing qualitative research British Sociological Association (BSA). 1998.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):1–10.

Roose GA, John A. A focus group investigation into young children’s understanding of mental health and their views on appropriate services for their age group. Child Care Health Dev. 2003;29(6):545–50.

Johansson A, Brunnberg E, Eriksson C. Adolescent girls’ and boys’ perceptions of mental health. J Youth Stud. 2007;10(2):183–202.

Landstedt E, Asplund K, Gillander GK. Understanding adolescent mental health: the influence of social processes, doing gender and gendered power relations. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31(7):962–78.

Svirydzenka N, Bone C, Dogra N. Schoolchildren’s perspectives on the meaning of mental health. J Public Ment Health. 2014;13(1):4–12.

Chisholm K, Patterson P, Greenfield S, Turner E, Birchwood M. Adolescent construction of mental illness: implication for engagement and treatment. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(4):626–36.

Perre NM, Wilson NJ, Smith-Merry J, Murphy G. Australian university students’ perceptions of mental illness: a qualitative study. JANZSSA. 2016;24(2):1–15. Available at: https://janzssa.scholasticahq.com/article/1092-australian-university-students-perceptions-of-mental-illness-a-qualitative-study .

O’reilly M, Dogra N, Whiteman N, Hughes J, Eruyar S, Reilly P. Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;23(4):601–13.

Molenaar A, Choi TS, Brennan L, et al. Language of health of young Australian adults: a qualitative exploration of perceptions of health, wellbeing and health promotion via online conversations. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):887.

Laidlaw A, McLellan J, Ozakinci G. Understanding undergraduate student perceptions of mental health, mental well-being and help-seeking behaviour. Stud High Educ. 2016;41(12):2156–68.

Nilsson B, Lindström UÅ, Nåden D. Is loneliness a psychological dysfunction? A literary study of the phenomenon of loneliness. Scand J Caring Sci. 2006;20(1):93–101.

Layard R. Happiness and the Teaching of Values. CentrePiece. 2007;12(1):18–23.

Horwitz AV. Transforming normality into pathology: the DSM and the outcomes of stressful social arrangements. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(3):211–22.

Björkqvist K, Lagerspetz KM, Kaukiainen A. Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggressive Behav. 1992;18(2):117–27.

Rose AJ, Smith RL, Glick GC, Schwartz-Mette RA. Girls’ and boys’ problem talk: Implications for emotional closeness in friendships. Dev Psychol. 2016;52(4):629.

von dem Knesebeck O, Mnich E, Daubmann A, et al. Socioeconomic status and beliefs about depression, schizophrenia and eating disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(5):775–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0599-1 . [published Online First: Epub Date]|.

Tudor K. Mental health promotion: paradigms and practice (1st ed.). Routledge: 1996. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315812670 .

Ma KKY, Anderson JK, Burn AM. School-based interventions to improve mental health literacy and reduce mental health stigma–a systematic review. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2023;28(2):230–40.

Bjønness S, Grønnestad T, Storm M. I’m not a diagnosis: Adolescents’ perspectives on user participation and shared decision-making in mental healthcare. Scand J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Psychol. 2020;8(1):139–48.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Meldahl LG, Krijger L, Andvik MM, et al. Characteristics of the ideal healthcare services to meet adolescents’ mental health needs: A qualitative study of adolescents’ perspectives. Health Expect. 2022;25(6):2924–36.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Karlstad University. The authors report no funding source.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health Service, Management and Policy, University of Florida, 1125, Central Dr. 32610, Gainesville, FL, USA

Linda Beckman & Sven Hassler

Department of Public Health Science, Karlstad University, Universitetsgatan 2, 651 88, Karlstad, Sweden

Linda Beckman

Department of School Development and Leadership, Malmö University, 211 19, Malmö, Sweden

Lisa Hellström

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

L.B and L.H conducted the literature search and scanned the abstracts. L.B drafted the manuscript, figures, and tables. All (L.B, L.H., S.H.) authors discussed and wrote the results, as well as the discussion. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sven Hassler .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Since data is based on published articles, no ethical approval is necessary.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Beckman, L., Hassler, S. & Hellström, L. Children and youth’s perceptions of mental health—a scoping review of qualitative studies. BMC Psychiatry 23 , 669 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05169-x

Download citation

Received : 06 May 2023

Accepted : 05 September 2023

Published : 14 September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05169-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Perceptions

- Public health

- Scoping review

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]