Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

Published on August 30, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on July 18, 2023.

A results section is where you report the main findings of the data collection and analysis you conducted for your thesis or dissertation . You should report all relevant results concisely and objectively, in a logical order. Don’t include subjective interpretations of why you found these results or what they mean—any evaluation should be saved for the discussion section .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

How to write a results section, reporting quantitative research results, reporting qualitative research results, results vs. discussion vs. conclusion, checklist: research results, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about results sections.

When conducting research, it’s important to report the results of your study prior to discussing your interpretations of it. This gives your reader a clear idea of exactly what you found and keeps the data itself separate from your subjective analysis.

Here are a few best practices:

- Your results should always be written in the past tense.

- While the length of this section depends on how much data you collected and analyzed, it should be written as concisely as possible.

- Only include results that are directly relevant to answering your research questions . Avoid speculative or interpretative words like “appears” or “implies.”

- If you have other results you’d like to include, consider adding them to an appendix or footnotes.

- Always start out with your broadest results first, and then flow into your more granular (but still relevant) ones. Think of it like a shoe store: first discuss the shoes as a whole, then the sneakers, boots, sandals, etc.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you conducted quantitative research , you’ll likely be working with the results of some sort of statistical analysis .

Your results section should report the results of any statistical tests you used to compare groups or assess relationships between variables . It should also state whether or not each hypothesis was supported.

The most logical way to structure quantitative results is to frame them around your research questions or hypotheses. For each question or hypothesis, share:

- A reminder of the type of analysis you used (e.g., a two-sample t test or simple linear regression ). A more detailed description of your analysis should go in your methodology section.

- A concise summary of each relevant result, both positive and negative. This can include any relevant descriptive statistics (e.g., means and standard deviations ) as well as inferential statistics (e.g., t scores, degrees of freedom , and p values ). Remember, these numbers are often placed in parentheses.

- A brief statement of how each result relates to the question, or whether the hypothesis was supported. You can briefly mention any results that didn’t fit with your expectations and assumptions, but save any speculation on their meaning or consequences for your discussion and conclusion.

A note on tables and figures

In quantitative research, it’s often helpful to include visual elements such as graphs, charts, and tables , but only if they are directly relevant to your results. Give these elements clear, descriptive titles and labels so that your reader can easily understand what is being shown. If you want to include any other visual elements that are more tangential in nature, consider adding a figure and table list .

As a rule of thumb:

- Tables are used to communicate exact values, giving a concise overview of various results

- Graphs and charts are used to visualize trends and relationships, giving an at-a-glance illustration of key findings

Don’t forget to also mention any tables and figures you used within the text of your results section. Summarize or elaborate on specific aspects you think your reader should know about rather than merely restating the same numbers already shown.

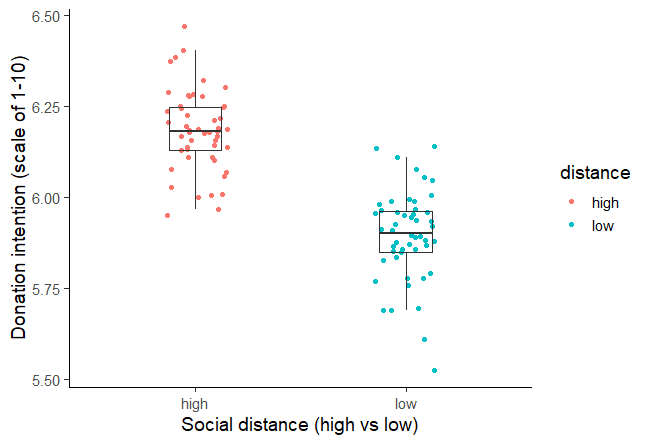

A two-sample t test was used to test the hypothesis that higher social distance from environmental problems would reduce the intent to donate to environmental organizations, with donation intention (recorded as a score from 1 to 10) as the outcome variable and social distance (categorized as either a low or high level of social distance) as the predictor variable.Social distance was found to be positively correlated with donation intention, t (98) = 12.19, p < .001, with the donation intention of the high social distance group 0.28 points higher, on average, than the low social distance group (see figure 1). This contradicts the initial hypothesis that social distance would decrease donation intention, and in fact suggests a small effect in the opposite direction.

Figure 1: Intention to donate to environmental organizations based on social distance from impact of environmental damage.

In qualitative research , your results might not all be directly related to specific hypotheses. In this case, you can structure your results section around key themes or topics that emerged from your analysis of the data.

For each theme, start with general observations about what the data showed. You can mention:

- Recurring points of agreement or disagreement

- Patterns and trends

- Particularly significant snippets from individual responses

Next, clarify and support these points with direct quotations. Be sure to report any relevant demographic information about participants. Further information (such as full transcripts , if appropriate) can be included in an appendix .

When asked about video games as a form of art, the respondents tended to believe that video games themselves are not an art form, but agreed that creativity is involved in their production. The criteria used to identify artistic video games included design, story, music, and creative teams.One respondent (male, 24) noted a difference in creativity between popular video game genres:

“I think that in role-playing games, there’s more attention to character design, to world design, because the whole story is important and more attention is paid to certain game elements […] so that perhaps you do need bigger teams of creative experts than in an average shooter or something.”

Responses suggest that video game consumers consider some types of games to have more artistic potential than others.

Your results section should objectively report your findings, presenting only brief observations in relation to each question, hypothesis, or theme.

It should not speculate about the meaning of the results or attempt to answer your main research question . Detailed interpretation of your results is more suitable for your discussion section , while synthesis of your results into an overall answer to your main research question is best left for your conclusion .

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

I have completed my data collection and analyzed the results.

I have included all results that are relevant to my research questions.

I have concisely and objectively reported each result, including relevant descriptive statistics and inferential statistics .

I have stated whether each hypothesis was supported or refuted.

I have used tables and figures to illustrate my results where appropriate.

All tables and figures are correctly labelled and referred to in the text.

There is no subjective interpretation or speculation on the meaning of the results.

You've finished writing up your results! Use the other checklists to further improve your thesis.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The results chapter of a thesis or dissertation presents your research results concisely and objectively.

In quantitative research , for each question or hypothesis , state:

- The type of analysis used

- Relevant results in the form of descriptive and inferential statistics

- Whether or not the alternative hypothesis was supported

In qualitative research , for each question or theme, describe:

- Recurring patterns

- Significant or representative individual responses

- Relevant quotations from the data

Don’t interpret or speculate in the results chapter.

Results are usually written in the past tense , because they are describing the outcome of completed actions.

The results chapter or section simply and objectively reports what you found, without speculating on why you found these results. The discussion interprets the meaning of the results, puts them in context, and explains why they matter.

In qualitative research , results and discussion are sometimes combined. But in quantitative research , it’s considered important to separate the objective results from your interpretation of them.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, July 18). How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/results/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a discussion section | tips & examples, how to write a thesis or dissertation conclusion, what is your plagiarism score.

How To Write The Results/Findings Chapter

For qualitative studies (dissertations & theses).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD Cand). Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

So, you’ve collected and analysed your qualitative data, and it’s time to write up your results chapter – exciting! But where do you start? In this post, we’ll guide you through the qualitative results chapter (also called the findings chapter), step by step.

Overview: Qualitative Results Chapter

- What (exactly) the qualitative results chapter is

- What to include in your results chapter

- How to write up your results chapter

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

What exactly is the results chapter?

The results chapter in a dissertation or thesis (or any formal academic research piece) is where you objectively and neutrally present the findings of your qualitative analysis (or analyses if you used multiple qualitative analysis methods ). This chapter can sometimes be combined with the discussion chapter (where you interpret the data and discuss its meaning), depending on your university’s preference. We’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as that’s the most common approach.

In contrast to a quantitative results chapter that presents numbers and statistics, a qualitative results chapter presents data primarily in the form of words . But this doesn’t mean that a qualitative study can’t have quantitative elements – you could, for example, present the number of times a theme or topic pops up in your data, depending on the analysis method(s) you adopt.

Adding a quantitative element to your study can add some rigour, which strengthens your results by providing more evidence for your claims. This is particularly common when using qualitative content analysis. Keep in mind though that qualitative research aims to achieve depth, richness and identify nuances , so don’t get tunnel vision by focusing on the numbers. They’re just cream on top in a qualitative analysis.

So, to recap, the results chapter is where you objectively present the findings of your analysis, without interpreting them (you’ll save that for the discussion chapter). With that out the way, let’s take a look at what you should include in your results chapter.

What should you include in the results chapter?

As we’ve mentioned, your qualitative results chapter should purely present and describe your results , not interpret them in relation to the existing literature or your research questions . Any speculations or discussion about the implications of your findings should be reserved for your discussion chapter.

In your results chapter, you’ll want to talk about your analysis findings and whether or not they support your hypotheses (if you have any). Naturally, the exact contents of your results chapter will depend on which qualitative analysis method (or methods) you use. For example, if you were to use thematic analysis, you’d detail the themes identified in your analysis, using extracts from the transcripts or text to support your claims.

While you do need to present your analysis findings in some detail, you should avoid dumping large amounts of raw data in this chapter. Instead, focus on presenting the key findings and using a handful of select quotes or text extracts to support each finding . The reams of data and analysis can be relegated to your appendices.

While it’s tempting to include every last detail you found in your qualitative analysis, it is important to make sure that you report only that which is relevant to your research aims, objectives and research questions . Always keep these three components, as well as your hypotheses (if you have any) front of mind when writing the chapter and use them as a filter to decide what’s relevant and what’s not.

Need a helping hand?

How do I write the results chapter?

Now that we’ve covered the basics, it’s time to look at how to structure your chapter. Broadly speaking, the results chapter needs to contain three core components – the introduction, the body and the concluding summary. Let’s take a look at each of these.

Section 1: Introduction

The first step is to craft a brief introduction to the chapter. This intro is vital as it provides some context for your findings. In your introduction, you should begin by reiterating your problem statement and research questions and highlight the purpose of your research . Make sure that you spell this out for the reader so that the rest of your chapter is well contextualised.

The next step is to briefly outline the structure of your results chapter. In other words, explain what’s included in the chapter and what the reader can expect. In the results chapter, you want to tell a story that is coherent, flows logically, and is easy to follow , so make sure that you plan your structure out well and convey that structure (at a high level), so that your reader is well oriented.

The introduction section shouldn’t be lengthy. Two or three short paragraphs should be more than adequate. It is merely an introduction and overview, not a summary of the chapter.

Pro Tip – To help you structure your chapter, it can be useful to set up an initial draft with (sub)section headings so that you’re able to easily (re)arrange parts of your chapter. This will also help your reader to follow your results and give your chapter some coherence. Be sure to use level-based heading styles (e.g. Heading 1, 2, 3 styles) to help the reader differentiate between levels visually. You can find these options in Word (example below).

Section 2: Body

Before we get started on what to include in the body of your chapter, it’s vital to remember that a results section should be completely objective and descriptive, not interpretive . So, be careful not to use words such as, “suggests” or “implies”, as these usually accompany some form of interpretation – that’s reserved for your discussion chapter.

The structure of your body section is very important , so make sure that you plan it out well. When planning out your qualitative results chapter, create sections and subsections so that you can maintain the flow of the story you’re trying to tell. Be sure to systematically and consistently describe each portion of results. Try to adopt a standardised structure for each portion so that you achieve a high level of consistency throughout the chapter.

For qualitative studies, results chapters tend to be structured according to themes , which makes it easier for readers to follow. However, keep in mind that not all results chapters have to be structured in this manner. For example, if you’re conducting a longitudinal study, you may want to structure your chapter chronologically. Similarly, you might structure this chapter based on your theoretical framework . The exact structure of your chapter will depend on the nature of your study , especially your research questions.

As you work through the body of your chapter, make sure that you use quotes to substantiate every one of your claims . You can present these quotes in italics to differentiate them from your own words. A general rule of thumb is to use at least two pieces of evidence per claim, and these should be linked directly to your data. Also, remember that you need to include all relevant results , not just the ones that support your assumptions or initial leanings.

In addition to including quotes, you can also link your claims to the data by using appendices , which you should reference throughout your text. When you reference, make sure that you include both the name/number of the appendix , as well as the line(s) from which you drew your data.

As referencing styles can vary greatly, be sure to look up the appendix referencing conventions of your university’s prescribed style (e.g. APA , Harvard, etc) and keep this consistent throughout your chapter.

Section 3: Concluding summary

The concluding summary is very important because it summarises your key findings and lays the foundation for the discussion chapter . Keep in mind that some readers may skip directly to this section (from the introduction section), so make sure that it can be read and understood well in isolation.

In this section, you need to remind the reader of the key findings. That is, the results that directly relate to your research questions and that you will build upon in your discussion chapter. Remember, your reader has digested a lot of information in this chapter, so you need to use this section to remind them of the most important takeaways.

Importantly, the concluding summary should not present any new information and should only describe what you’ve already presented in your chapter. Keep it concise – you’re not summarising the whole chapter, just the essentials.

Tips and tricks for an A-grade results chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear picture of what the qualitative results chapter is all about, here are some quick tips and reminders to help you craft a high-quality chapter:

- Your results chapter should be written in the past tense . You’ve done the work already, so you want to tell the reader what you found , not what you are currently finding .

- Make sure that you review your work multiple times and check that every claim is adequately backed up by evidence . Aim for at least two examples per claim, and make use of an appendix to reference these.

- When writing up your results, make sure that you stick to only what is relevant . Don’t waste time on data that are not relevant to your research objectives and research questions.

- Use headings and subheadings to create an intuitive, easy to follow piece of writing. Make use of Microsoft Word’s “heading styles” and be sure to use them consistently.

- When referring to numerical data, tables and figures can provide a useful visual aid. When using these, make sure that they can be read and understood independent of your body text (i.e. that they can stand-alone). To this end, use clear, concise labels for each of your tables or figures and make use of colours to code indicate differences or hierarchy.

- Similarly, when you’re writing up your chapter, it can be useful to highlight topics and themes in different colours . This can help you to differentiate between your data if you get a bit overwhelmed and will also help you to ensure that your results flow logically and coherently.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help. If you’d like 1-on-1 help with your results chapter (or any chapter of your dissertation or thesis), check out our private dissertation coaching service here or book a free initial consultation to discuss how we can help you.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

20 Comments

This was extremely helpful. Thanks a lot guys

Hi, thanks for the great research support platform created by the gradcoach team!

I wanted to ask- While “suggests” or “implies” are interpretive terms, what terms could we use for the results chapter? Could you share some examples of descriptive terms?

I think that instead of saying, ‘The data suggested, or The data implied,’ you can say, ‘The Data showed or revealed, or illustrated or outlined’…If interview data, you may say Jane Doe illuminated or elaborated, or Jane Doe described… or Jane Doe expressed or stated.

I found this article very useful. Thank you very much for the outstanding work you are doing.

What if i have 3 different interviewees answering the same interview questions? Should i then present the results in form of the table with the division on the 3 perspectives or rather give a results in form of the text and highlight who said what?

I think this tabular representation of results is a great idea. I am doing it too along with the text. Thanks

That was helpful was struggling to separate the discussion from the findings

this was very useful, Thank you.

Very helpful, I am confident to write my results chapter now.

It is so helpful! It is a good job. Thank you very much!

Very useful, well explained. Many thanks.

Hello, I appreciate the way you provided a supportive comments about qualitative results presenting tips

I loved this! It explains everything needed, and it has helped me better organize my thoughts. What words should I not use while writing my results section, other than subjective ones.

Thanks a lot, it is really helpful

Thank you so much dear, i really appropriate your nice explanations about this.

Thank you so much for this! I was wondering if anyone could help with how to prproperly integrate quotations (Excerpts) from interviews in the finding chapter in a qualitative research. Please GradCoach, address this issue and provide examples.

what if I’m not doing any interviews myself and all the information is coming from case studies that have already done the research.

Very helpful thank you.

This was very helpful as I was wondering how to structure this part of my dissertation, to include the quotes… Thanks for this explanation

This is very helpful, thanks! I am required to write up my results chapters with the discussion in each of them – any tips and tricks for this strategy?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Qualitative Data Analysis

23 Presenting the Results of Qualitative Analysis

Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur

Qualitative research is not finished just because you have determined the main findings or conclusions of your study. Indeed, disseminating the results is an essential part of the research process. By sharing your results with others, whether in written form as scholarly paper or an applied report or in some alternative format like an oral presentation, an infographic, or a video, you ensure that your findings become part of the ongoing conversation of scholarship in your field, forming part of the foundation for future researchers. This chapter provides an introduction to writing about qualitative research findings. It will outline how writing continues to contribute to the analysis process, what concerns researchers should keep in mind as they draft their presentations of findings, and how best to organize qualitative research writing

As you move through the research process, it is essential to keep yourself organized. Organizing your data, memos, and notes aids both the analytical and the writing processes. Whether you use electronic or physical, real-world filing and organizational systems, these systems help make sense of the mountains of data you have and assure you focus your attention on the themes and ideas you have determined are important (Warren and Karner 2015). Be sure that you have kept detailed notes on all of the decisions you have made and procedures you have followed in carrying out research design, data collection, and analysis, as these will guide your ultimate write-up.

First and foremost, researchers should keep in mind that writing is in fact a form of thinking. Writing is an excellent way to discover ideas and arguments and to further develop an analysis. As you write, more ideas will occur to you, things that were previously confusing will start to make sense, and arguments will take a clear shape rather than being amorphous and poorly-organized. However, writing-as-thinking cannot be the final version that you share with others. Good-quality writing does not display the workings of your thought process. It is reorganized and revised (more on that later) to present the data and arguments important in a particular piece. And revision is totally normal! No one expects the first draft of a piece of writing to be ready for prime time. So write rough drafts and memos and notes to yourself and use them to think, and then revise them until the piece is the way you want it to be for sharing.

Bergin (2018) lays out a set of key concerns for appropriate writing about research. First, present your results accurately, without exaggerating or misrepresenting. It is very easy to overstate your findings by accident if you are enthusiastic about what you have found, so it is important to take care and use appropriate cautions about the limitations of the research. You also need to work to ensure that you communicate your findings in a way people can understand, using clear and appropriate language that is adjusted to the level of those you are communicating with. And you must be clear and transparent about the methodological strategies employed in the research. Remember, the goal is, as much as possible, to describe your research in a way that would permit others to replicate the study. There are a variety of other concerns and decision points that qualitative researchers must keep in mind, including the extent to which to include quantification in their presentation of results, ethics, considerations of audience and voice, and how to bring the richness of qualitative data to life.

Quantification, as you have learned, refers to the process of turning data into numbers. It can indeed be very useful to count and tabulate quantitative data drawn from qualitative research. For instance, if you were doing a study of dual-earner households and wanted to know how many had an equal division of household labor and how many did not, you might want to count those numbers up and include them as part of the final write-up. However, researchers need to take care when they are writing about quantified qualitative data. Qualitative data is not as generalizable as quantitative data, so quantification can be very misleading. Thus, qualitative researchers should strive to use raw numbers instead of the percentages that are more appropriate for quantitative research. Writing, for instance, “15 of the 20 people I interviewed prefer pancakes to waffles” is a simple description of the data; writing “75% of people prefer pancakes” suggests a generalizable claim that is not likely supported by the data. Note that mixing numbers with qualitative data is really a type of mixed-methods approach. Mixed-methods approaches are good, but sometimes they seduce researchers into focusing on the persuasive power of numbers and tables rather than capitalizing on the inherent richness of their qualitative data.

A variety of issues of scholarly ethics and research integrity are raised by the writing process. Some of these are unique to qualitative research, while others are more universal concerns for all academic and professional writing. For example, it is essential to avoid plagiarism and misuse of sources. All quotations that appear in a text must be properly cited, whether with in-text and bibliographic citations to the source or with an attribution to the research participant (or the participant’s pseudonym or description in order to protect confidentiality) who said those words. Where writers will paraphrase a text or a participant’s words, they need to make sure that the paraphrase they develop accurately reflects the meaning of the original words. Thus, some scholars suggest that participants should have the opportunity to read (or to have read to them, if they cannot read the text themselves) all sections of the text in which they, their words, or their ideas are presented to ensure accuracy and enable participants to maintain control over their lives.

Audience and Voice

When writing, researchers must consider their audience(s) and the effects they want their writing to have on these audiences. The designated audience will dictate the voice used in the writing, or the individual style and personality of a piece of text. Keep in mind that the potential audience for qualitative research is often much more diverse than that for quantitative research because of the accessibility of the data and the extent to which the writing can be accessible and interesting. Yet individual pieces of writing are typically pitched to a more specific subset of the audience.

Let us consider one potential research study, an ethnography involving participant-observation of the same children both when they are at daycare facility and when they are at home with their families to try to understand how daycare might impact behavior and social development. The findings of this study might be of interest to a wide variety of potential audiences: academic peers, whether at your own academic institution, in your broader discipline, or multidisciplinary; people responsible for creating laws and policies; practitioners who run or teach at day care centers; and the general public, including both people who are interested in child development more generally and those who are themselves parents making decisions about child care for their own children. And the way you write for each of these audiences will be somewhat different. Take a moment and think through what some of these differences might look like.

If you are writing to academic audiences, using specialized academic language and working within the typical constraints of scholarly genres, as will be discussed below, can be an important part of convincing others that your work is legitimate and should be taken seriously. Your writing will be formal. Even if you are writing for students and faculty you already know—your classmates, for instance—you are often asked to imitate the style of academic writing that is used in publications, as this is part of learning to become part of the scholarly conversation. When speaking to academic audiences outside your discipline, you may need to be more careful about jargon and specialized language, as disciplines do not always share the same key terms. For instance, in sociology, scholars use the term diffusion to refer to the way new ideas or practices spread from organization to organization. In the field of international relations, scholars often used the term cascade to refer to the way ideas or practices spread from nation to nation. These terms are describing what is fundamentally the same concept, but they are different terms—and a scholar from one field might have no idea what a scholar from a different field is talking about! Therefore, while the formality and academic structure of the text would stay the same, a writer with a multidisciplinary audience might need to pay more attention to defining their terms in the body of the text.

It is not only other academic scholars who expect to see formal writing. Policymakers tend to expect formality when ideas are presented to them, as well. However, the content and style of the writing will be different. Much less academic jargon should be used, and the most important findings and policy implications should be emphasized right from the start rather than initially focusing on prior literature and theoretical models as you might for an academic audience. Long discussions of research methods should also be minimized. Similarly, when you write for practitioners, the findings and implications for practice should be highlighted. The reading level of the text will vary depending on the typical background of the practitioners to whom you are writing—you can make very different assumptions about the general knowledge and reading abilities of a group of hospital medical directors with MDs than you can about a group of case workers who have a post-high-school certificate. Consider the primary language of your audience as well. The fact that someone can get by in spoken English does not mean they have the vocabulary or English reading skills to digest a complex report. But the fact that someone’s vocabulary is limited says little about their intellectual abilities, so try your best to convey the important complexity of the ideas and findings from your research without dumbing them down—even if you must limit your vocabulary usage.

When writing for the general public, you will want to move even further towards emphasizing key findings and policy implications, but you also want to draw on the most interesting aspects of your data. General readers will read sociological texts that are rich with ethnographic or other kinds of detail—it is almost like reality television on a page! And this is a contrast to busy policymakers and practitioners, who probably want to learn the main findings as quickly as possible so they can go about their busy lives. But also keep in mind that there is a wide variation in reading levels. Journalists at publications pegged to the general public are often advised to write at about a tenth-grade reading level, which would leave most of the specialized terminology we develop in our research fields out of reach. If you want to be accessible to even more people, your vocabulary must be even more limited. The excellent exercise of trying to write using the 1,000 most common English words, available at the Up-Goer Five website ( https://www.splasho.com/upgoer5/ ) does a good job of illustrating this challenge (Sanderson n.d.).

Another element of voice is whether to write in the first person. While many students are instructed to avoid the use of the first person in academic writing, this advice needs to be taken with a grain of salt. There are indeed many contexts in which the first person is best avoided, at least as long as writers can find ways to build strong, comprehensible sentences without its use, including most quantitative research writing. However, if the alternative to using the first person is crafting a sentence like “it is proposed that the researcher will conduct interviews,” it is preferable to write “I propose to conduct interviews.” In qualitative research, in fact, the use of the first person is far more common. This is because the researcher is central to the research project. Qualitative researchers can themselves be understood as research instruments, and thus eliminating the use of the first person in writing is in a sense eliminating information about the conduct of the researchers themselves.

But the question really extends beyond the issue of first-person or third-person. Qualitative researchers have choices about how and whether to foreground themselves in their writing, not just in terms of using the first person, but also in terms of whether to emphasize their own subjectivity and reflexivity, their impressions and ideas, and their role in the setting. In contrast, conventional quantitative research in the positivist tradition really tries to eliminate the author from the study—which indeed is exactly why typical quantitative research avoids the use of the first person. Keep in mind that emphasizing researchers’ roles and reflexivity and using the first person does not mean crafting articles that provide overwhelming detail about the author’s thoughts and practices. Readers do not need to hear, and should not be told, which database you used to search for journal articles, how many hours you spent transcribing, or whether the research process was stressful—save these things for the memos you write to yourself. Rather, readers need to hear how you interacted with research participants, how your standpoint may have shaped the findings, and what analytical procedures you carried out.

Making Data Come Alive

One of the most important parts of writing about qualitative research is presenting the data in a way that makes its richness and value accessible to readers. As the discussion of analysis in the prior chapter suggests, there are a variety of ways to do this. Researchers may select key quotes or images to illustrate points, write up specific case studies that exemplify their argument, or develop vignettes (little stories) that illustrate ideas and themes, all drawing directly on the research data. Researchers can also write more lengthy summaries, narratives, and thick descriptions.

Nearly all qualitative work includes quotes from research participants or documents to some extent, though ethnographic work may focus more on thick description than on relaying participants’ own words. When quotes are presented, they must be explained and interpreted—they cannot stand on their own. This is one of the ways in which qualitative research can be distinguished from journalism. Journalism presents what happened, but social science needs to present the “why,” and the why is best explained by the researcher.

So how do authors go about integrating quotes into their written work? Julie Posselt (2017), a sociologist who studies graduate education, provides a set of instructions. First of all, authors need to remain focused on the core questions of their research, and avoid getting distracted by quotes that are interesting or attention-grabbing but not so relevant to the research question. Selecting the right quotes, those that illustrate the ideas and arguments of the paper, is an important part of the writing process. Second, not all quotes should be the same length (just like not all sentences or paragraphs in a paper should be the same length). Include some quotes that are just phrases, others that are a sentence or so, and others that are longer. We call longer quotes, generally those more than about three lines long, block quotes , and they are typically indented on both sides to set them off from the surrounding text. For all quotes, be sure to summarize what the quote should be telling or showing the reader, connect this quote to other quotes that are similar or different, and provide transitions in the discussion to move from quote to quote and from topic to topic. Especially for longer quotes, it is helpful to do some of this writing before the quote to preview what is coming and other writing after the quote to make clear what readers should have come to understand. Remember, it is always the author’s job to interpret the data. Presenting excerpts of the data, like quotes, in a form the reader can access does not minimize the importance of this job. Be sure that you are explaining the meaning of the data you present.

A few more notes about writing with quotes: avoid patchwriting, whether in your literature review or the section of your paper in which quotes from respondents are presented. Patchwriting is a writing practice wherein the author lightly paraphrases original texts but stays so close to those texts that there is little the author has added. Sometimes, this even takes the form of presenting a series of quotes, properly documented, with nothing much in the way of text generated by the author. A patchwriting approach does not build the scholarly conversation forward, as it does not represent any kind of new contribution on the part of the author. It is of course fine to paraphrase quotes, as long as the meaning is not changed. But if you use direct quotes, do not edit the text of the quotes unless how you edit them does not change the meaning and you have made clear through the use of ellipses (…) and brackets ([])what kinds of edits have been made. For example, consider this exchange from Matthew Desmond’s (2012:1317) research on evictions:

The thing was, I wasn’t never gonna let Crystal come and stay with me from the get go. I just told her that to throw her off. And she wasn’t fittin’ to come stay with me with no money…No. Nope. You might as well stay in that shelter.

A paraphrase of this exchange might read “She said that she was going to let Crystal stay with her if Crystal did not have any money.” Paraphrases like that are fine. What is not fine is rewording the statement but treating it like a quote, for instance writing:

The thing was, I was not going to let Crystal come and stay with me from beginning. I just told her that to throw her off. And it was not proper for her to come stay with me without any money…No. Nope. You might as well stay in that shelter.

But as you can see, the change in language and style removes some of the distinct meaning of the original quote. Instead, writers should leave as much of the original language as possible. If some text in the middle of the quote needs to be removed, as in this example, ellipses are used to show that this has occurred. And if a word needs to be added to clarify, it is placed in square brackets to show that it was not part of the original quote.

Data can also be presented through the use of data displays like tables, charts, graphs, diagrams, and infographics created for publication or presentation, as well as through the use of visual material collected during the research process. Note that if visuals are used, the author must have the legal right to use them. Photographs or diagrams created by the author themselves—or by research participants who have signed consent forms for their work to be used, are fine. But photographs, and sometimes even excerpts from archival documents, may be owned by others from whom researchers must get permission in order to use them.

A large percentage of qualitative research does not include any data displays or visualizations. Therefore, researchers should carefully consider whether the use of data displays will help the reader understand the data. One of the most common types of data displays used by qualitative researchers are simple tables. These might include tables summarizing key data about cases included in the study; tables laying out the characteristics of different taxonomic elements or types developed as part of the analysis; tables counting the incidence of various elements; and 2×2 tables (two columns and two rows) illuminating a theory. Basic network or process diagrams are also commonly included. If data displays are used, it is essential that researchers include context and analysis alongside data displays rather than letting them stand by themselves, and it is preferable to continue to present excerpts and examples from the data rather than just relying on summaries in the tables.

If you will be using graphs, infographics, or other data visualizations, it is important that you attend to making them useful and accurate (Bergin 2018). Think about the viewer or user as your audience and ensure the data visualizations will be comprehensible. You may need to include more detail or labels than you might think. Ensure that data visualizations are laid out and labeled clearly and that you make visual choices that enhance viewers’ ability to understand the points you intend to communicate using the visual in question. Finally, given the ease with which it is possible to design visuals that are deceptive or misleading, it is essential to make ethical and responsible choices in the construction of visualization so that viewers will interpret them in accurate ways.

The Genre of Research Writing

As discussed above, the style and format in which results are presented depends on the audience they are intended for. These differences in styles and format are part of the genre of writing. Genre is a term referring to the rules of a specific form of creative or productive work. Thus, the academic journal article—and student papers based on this form—is one genre. A report or policy paper is another. The discussion below will focus on the academic journal article, but note that reports and policy papers follow somewhat different formats. They might begin with an executive summary of one or a few pages, include minimal background, focus on key findings, and conclude with policy implications, shifting methods and details about the data to an appendix. But both academic journal articles and policy papers share some things in common, for instance the necessity for clear writing, a well-organized structure, and the use of headings.

So what factors make up the genre of the academic journal article in sociology? While there is some flexibility, particularly for ethnographic work, academic journal articles tend to follow a fairly standard format. They begin with a “title page” that includes the article title (often witty and involving scholarly inside jokes, but more importantly clearly describing the content of the article); the authors’ names and institutional affiliations, an abstract , and sometimes keywords designed to help others find the article in databases. An abstract is a short summary of the article that appears both at the very beginning of the article and in search databases. Abstracts are designed to aid readers by giving them the opportunity to learn enough about an article that they can determine whether it is worth their time to read the complete text. They are written about the article, and thus not in the first person, and clearly summarize the research question, methodological approach, main findings, and often the implications of the research.

After the abstract comes an “introduction” of a page or two that details the research question, why it matters, and what approach the paper will take. This is followed by a literature review of about a quarter to a third the length of the entire paper. The literature review is often divided, with headings, into topical subsections, and is designed to provide a clear, thorough overview of the prior research literature on which a paper has built—including prior literature the new paper contradicts. At the end of the literature review it should be made clear what researchers know about the research topic and question, what they do not know, and what this new paper aims to do to address what is not known.

The next major section of the paper is the section that describes research design, data collection, and data analysis, often referred to as “research methods” or “methodology.” This section is an essential part of any written or oral presentation of your research. Here, you tell your readers or listeners “how you collected and interpreted your data” (Taylor, Bogdan, and DeVault 2016:215). Taylor, Bogdan, and DeVault suggest that the discussion of your research methods include the following:

- The particular approach to data collection used in the study;

- Any theoretical perspective(s) that shaped your data collection and analytical approach;

- When the study occurred, over how long, and where (concealing identifiable details as needed);

- A description of the setting and participants, including sampling and selection criteria (if an interview-based study, the number of participants should be clearly stated);

- The researcher’s perspective in carrying out the study, including relevant elements of their identity and standpoint, as well as their role (if any) in research settings; and

- The approach to analyzing the data.

After the methods section comes a section, variously titled but often called “data,” that takes readers through the analysis. This section is where the thick description narrative; the quotes, broken up by theme or topic, with their interpretation; the discussions of case studies; most data displays (other than perhaps those outlining a theoretical model or summarizing descriptive data about cases); and other similar material appears. The idea of the data section is to give readers the ability to see the data for themselves and to understand how this data supports the ultimate conclusions. Note that all tables and figures included in formal publications should be titled and numbered.

At the end of the paper come one or two summary sections, often called “discussion” and/or “conclusion.” If there is a separate discussion section, it will focus on exploring the overall themes and findings of the paper. The conclusion clearly and succinctly summarizes the findings and conclusions of the paper, the limitations of the research and analysis, any suggestions for future research building on the paper or addressing these limitations, and implications, be they for scholarship and theory or policy and practice.

After the end of the textual material in the paper comes the bibliography, typically called “works cited” or “references.” The references should appear in a consistent citation style—in sociology, we often use the American Sociological Association format (American Sociological Association 2019), but other formats may be used depending on where the piece will eventually be published. Care should be taken to ensure that in-text citations also reflect the chosen citation style. In some papers, there may be an appendix containing supplemental information such as a list of interview questions or an additional data visualization.

Note that when researchers give presentations to scholarly audiences, the presentations typically follow a format similar to that of scholarly papers, though given time limitations they are compressed. Abstracts and works cited are often not part of the presentation, though in-text citations are still used. The literature review presented will be shortened to only focus on the most important aspects of the prior literature, and only key examples from the discussion of data will be included. For long or complex papers, sometimes only one of several findings is the focus of the presentation. Of course, presentations for other audiences may be constructed differently, with greater attention to interesting elements of the data and findings as well as implications and less to the literature review and methods.

Concluding Your Work

After you have written a complete draft of the paper, be sure you take the time to revise and edit your work. There are several important strategies for revision. First, put your work away for a little while. Even waiting a day to revise is better than nothing, but it is best, if possible, to take much more time away from the text. This helps you forget what your writing looks like and makes it easier to find errors, mistakes, and omissions. Second, show your work to others. Ask them to read your work and critique it, pointing out places where the argument is weak, where you may have overlooked alternative explanations, where the writing could be improved, and what else you need to work on. Finally, read your work out loud to yourself (or, if you really need an audience, try reading to some stuffed animals). Reading out loud helps you catch wrong words, tricky sentences, and many other issues. But as important as revision is, try to avoid perfectionism in writing (Warren and Karner 2015). Writing can always be improved, no matter how much time you spend on it. Those improvements, however, have diminishing returns, and at some point the writing process needs to conclude so the writing can be shared with the world.

Of course, the main goal of writing up the results of a research project is to share with others. Thus, researchers should be considering how they intend to disseminate their results. What conferences might be appropriate? Where can the paper be submitted? Note that if you are an undergraduate student, there are a wide variety of journals that accept and publish research conducted by undergraduates. Some publish across disciplines, while others are specific to disciplines. Other work, such as reports, may be best disseminated by publication online on relevant organizational websites.

After a project is completed, be sure to take some time to organize your research materials and archive them for longer-term storage. Some Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols require that original data, such as interview recordings, transcripts, and field notes, be preserved for a specific number of years in a protected (locked for paper or password-protected for digital) form and then destroyed, so be sure that your plans adhere to the IRB requirements. Be sure you keep any materials that might be relevant for future related research or for answering questions people may ask later about your project.

And then what? Well, then it is time to move on to your next research project. Research is a long-term endeavor, not a one-time-only activity. We build our skills and our expertise as we continue to pursue research. So keep at it.

- Find a short article that uses qualitative methods. The sociological magazine Contexts is a good place to find such pieces. Write an abstract of the article.

- Choose a sociological journal article on a topic you are interested in that uses some form of qualitative methods and is at least 20 pages long. Rewrite the article as a five-page research summary accessible to non-scholarly audiences.

- Choose a concept or idea you have learned in this course and write an explanation of it using the Up-Goer Five Text Editor ( https://www.splasho.com/upgoer5/ ), a website that restricts your writing to the 1,000 most common English words. What was this experience like? What did it teach you about communicating with people who have a more limited English-language vocabulary—and what did it teach you about the utility of having access to complex academic language?

- Select five or more sociological journal articles that all use the same basic type of qualitative methods (interviewing, ethnography, documents, or visual sociology). Using what you have learned about coding, code the methods sections of each article, and use your coding to figure out what is common in how such articles discuss their research design, data collection, and analysis methods.

- Return to an exercise you completed earlier in this course and revise your work. What did you change? How did revising impact the final product?

- Find a quote from the transcript of an interview, a social media post, or elsewhere that has not yet been interpreted or explained. Write a paragraph that includes the quote along with an explanation of its sociological meaning or significance.

The style or personality of a piece of writing, including such elements as tone, word choice, syntax, and rhythm.

A quotation, usually one of some length, which is set off from the main text by being indented on both sides rather than being placed in quotation marks.

A classification of written or artistic work based on form, content, and style.

A short summary of a text written from the perspective of a reader rather than from the perspective of an author.

Social Data Analysis Copyright © 2021 by Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Pharm Educ

- v.74(8); 2010 Oct 11

Presenting and Evaluating Qualitative Research

The purpose of this paper is to help authors to think about ways to present qualitative research papers in the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education . It also discusses methods for reviewers to assess the rigour, quality, and usefulness of qualitative research. Examples of different ways to present data from interviews, observations, and focus groups are included. The paper concludes with guidance for publishing qualitative research and a checklist for authors and reviewers.

INTRODUCTION

Policy and practice decisions, including those in education, increasingly are informed by findings from qualitative as well as quantitative research. Qualitative research is useful to policymakers because it often describes the settings in which policies will be implemented. Qualitative research is also useful to both pharmacy practitioners and pharmacy academics who are involved in researching educational issues in both universities and practice and in developing teaching and learning.

Qualitative research involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data that are not easily reduced to numbers. These data relate to the social world and the concepts and behaviors of people within it. Qualitative research can be found in all social sciences and in the applied fields that derive from them, for example, research in health services, nursing, and pharmacy. 1 It looks at X in terms of how X varies in different circumstances rather than how big is X or how many Xs are there? 2 Textbooks often subdivide research into qualitative and quantitative approaches, furthering the common assumption that there are fundamental differences between the 2 approaches. With pharmacy educators who have been trained in the natural and clinical sciences, there is often a tendency to embrace quantitative research, perhaps due to familiarity. A growing consensus is emerging that sees both qualitative and quantitative approaches as useful to answering research questions and understanding the world. Increasingly mixed methods research is being carried out where the researcher explicitly combines the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the study. 3 , 4

Like healthcare, education involves complex human interactions that can rarely be studied or explained in simple terms. Complex educational situations demand complex understanding; thus, the scope of educational research can be extended by the use of qualitative methods. Qualitative research can sometimes provide a better understanding of the nature of educational problems and thus add to insights into teaching and learning in a number of contexts. For example, at the University of Nottingham, we conducted in-depth interviews with pharmacists to determine their perceptions of continuing professional development and who had influenced their learning. We also have used a case study approach using observation of practice and in-depth interviews to explore physiotherapists' views of influences on their leaning in practice. We have conducted in-depth interviews with a variety of stakeholders in Malawi, Africa, to explore the issues surrounding pharmacy academic capacity building. A colleague has interviewed and conducted focus groups with students to explore cultural issues as part of a joint Nottingham-Malaysia pharmacy degree program. Another colleague has interviewed pharmacists and patients regarding their expectations before and after clinic appointments and then observed pharmacist-patient communication in clinics and assessed it using the Calgary Cambridge model in order to develop recommendations for communication skills training. 5 We have also performed documentary analysis on curriculum data to compare pharmacist and nurse supplementary prescribing courses in the United Kingdom.

It is important to choose the most appropriate methods for what is being investigated. Qualitative research is not appropriate to answer every research question and researchers need to think carefully about their objectives. Do they wish to study a particular phenomenon in depth (eg, students' perceptions of studying in a different culture)? Or are they more interested in making standardized comparisons and accounting for variance (eg, examining differences in examination grades after changing the way the content of a module is taught). Clearly a quantitative approach would be more appropriate in the last example. As with any research project, a clear research objective has to be identified to know which methods should be applied.

Types of qualitative data include:

- Audio recordings and transcripts from in-depth or semi-structured interviews

- Structured interview questionnaires containing substantial open comments including a substantial number of responses to open comment items.

- Audio recordings and transcripts from focus group sessions.

- Field notes (notes taken by the researcher while in the field [setting] being studied)

- Video recordings (eg, lecture delivery, class assignments, laboratory performance)

- Case study notes

- Documents (reports, meeting minutes, e-mails)

- Diaries, video diaries

- Observation notes

- Press clippings

- Photographs

RIGOUR IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative research is often criticized as biased, small scale, anecdotal, and/or lacking rigor; however, when it is carried out properly it is unbiased, in depth, valid, reliable, credible and rigorous. In qualitative research, there needs to be a way of assessing the “extent to which claims are supported by convincing evidence.” 1 Although the terms reliability and validity traditionally have been associated with quantitative research, increasingly they are being seen as important concepts in qualitative research as well. Examining the data for reliability and validity assesses both the objectivity and credibility of the research. Validity relates to the honesty and genuineness of the research data, while reliability relates to the reproducibility and stability of the data.

The validity of research findings refers to the extent to which the findings are an accurate representation of the phenomena they are intended to represent. The reliability of a study refers to the reproducibility of the findings. Validity can be substantiated by a number of techniques including triangulation use of contradictory evidence, respondent validation, and constant comparison. Triangulation is using 2 or more methods to study the same phenomenon. Contradictory evidence, often known as deviant cases, must be sought out, examined, and accounted for in the analysis to ensure that researcher bias does not interfere with or alter their perception of the data and any insights offered. Respondent validation, which is allowing participants to read through the data and analyses and provide feedback on the researchers' interpretations of their responses, provides researchers with a method of checking for inconsistencies, challenges the researchers' assumptions, and provides them with an opportunity to re-analyze their data. The use of constant comparison means that one piece of data (for example, an interview) is compared with previous data and not considered on its own, enabling researchers to treat the data as a whole rather than fragmenting it. Constant comparison also enables the researcher to identify emerging/unanticipated themes within the research project.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative researchers have been criticized for overusing interviews and focus groups at the expense of other methods such as ethnography, observation, documentary analysis, case studies, and conversational analysis. Qualitative research has numerous strengths when properly conducted.

Strengths of Qualitative Research

- Issues can be examined in detail and in depth.

- Interviews are not restricted to specific questions and can be guided/redirected by the researcher in real time.

- The research framework and direction can be quickly revised as new information emerges.

- The data based on human experience that is obtained is powerful and sometimes more compelling than quantitative data.

- Subtleties and complexities about the research subjects and/or topic are discovered that are often missed by more positivistic enquiries.

- Data usually are collected from a few cases or individuals so findings cannot be generalized to a larger population. Findings can however be transferable to another setting.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Research quality is heavily dependent on the individual skills of the researcher and more easily influenced by the researcher's personal biases and idiosyncrasies.

- Rigor is more difficult to maintain, assess, and demonstrate.

- The volume of data makes analysis and interpretation time consuming.

- It is sometimes not as well understood and accepted as quantitative research within the scientific community

- The researcher's presence during data gathering, which is often unavoidable in qualitative research, can affect the subjects' responses.

- Issues of anonymity and confidentiality can present problems when presenting findings

- Findings can be more difficult and time consuming to characterize in a visual way.

PRESENTATION OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH FINDINGS

The following extracts are examples of how qualitative data might be presented:

Data From an Interview.

The following is an example of how to present and discuss a quote from an interview.

The researcher should select quotes that are poignant and/or most representative of the research findings. Including large portions of an interview in a research paper is not necessary and often tedious for the reader. The setting and speakers should be established in the text at the end of the quote.

The student describes how he had used deep learning in a dispensing module. He was able to draw on learning from a previous module, “I found that while using the e learning programme I was able to apply the knowledge and skills that I had gained in last year's diseases and goals of treatment module.” (interviewee 22, male)

This is an excerpt from an article on curriculum reform that used interviews 5 :

The first question was, “Without the accreditation mandate, how much of this curriculum reform would have been attempted?” According to respondents, accreditation played a significant role in prompting the broad-based curricular change, and their comments revealed a nuanced view. Most indicated that the change would likely have occurred even without the mandate from the accreditation process: “It reflects where the profession wants to be … training a professional who wants to take on more responsibility.” However, they also commented that “if it were not mandated, it could have been a very difficult road.” Or it “would have happened, but much later.” The change would more likely have been incremental, “evolutionary,” or far more limited in its scope. “Accreditation tipped the balance” was the way one person phrased it. “Nobody got serious until the accrediting body said it would no longer accredit programs that did not change.”

Data From Observations

The following example is some data taken from observation of pharmacist patient consultations using the Calgary Cambridge guide. 6 , 7 The data are first presented and a discussion follows:

Pharmacist: We will soon be starting a stop smoking clinic. Patient: Is the interview over now? Pharmacist: No this is part of it. (Laughs) You can't tell me to bog off (sic) yet. (pause) We will be starting a stop smoking service here, Patient: Yes. Pharmacist: with one-to-one and we will be able to help you or try to help you. If you want it. In this example, the pharmacist has picked up from the patient's reaction to the stop smoking clinic that she is not receptive to advice about giving up smoking at this time; in fact she would rather end the consultation. The pharmacist draws on his prior relationship with the patient and makes use of a joke to lighten the tone. He feels his message is important enough to persevere but he presents the information in a succinct and non-pressurised way. His final comment of “If you want it” is important as this makes it clear that he is not putting any pressure on the patient to take up this offer. This extract shows that some patient cues were picked up, and appropriately dealt with, but this was not the case in all examples.

Data From Focus Groups

This excerpt from a study involving 11 focus groups illustrates how findings are presented using representative quotes from focus group participants. 8

Those pharmacists who were initially familiar with CPD endorsed the model for their peers, and suggested it had made a meaningful difference in the way they viewed their own practice. In virtually all focus groups sessions, pharmacists familiar with and supportive of the CPD paradigm had worked in collaborative practice environments such as hospital pharmacy practice. For these pharmacists, the major advantage of CPD was the linking of workplace learning with continuous education. One pharmacist stated, “It's amazing how much I have to learn every day, when I work as a pharmacist. With [the learning portfolio] it helps to show how much learning we all do, every day. It's kind of satisfying to look it over and see how much you accomplish.” Within many of the learning portfolio-sharing sessions, debates emerged regarding the true value of traditional continuing education and its outcome in changing an individual's practice. While participants appreciated the opportunity for social and professional networking inherent in some forms of traditional CE, most eventually conceded that the academic value of most CE programming was limited by the lack of a systematic process for following-up and implementing new learning in the workplace. “Well it's nice to go to these [continuing education] events, but really, I don't know how useful they are. You go, you sit, you listen, but then, well I at least forget.”

The following is an extract from a focus group (conducted by the author) with first-year pharmacy students about community placements. It illustrates how focus groups provide a chance for participants to discuss issues on which they might disagree.

Interviewer: So you are saying that you would prefer health related placements? Student 1: Not exactly so long as I could be developing my communication skill. Student 2: Yes but I still think the more health related the placement is the more I'll gain from it. Student 3: I disagree because other people related skills are useful and you may learn those from taking part in a community project like building a garden. Interviewer: So would you prefer a mixture of health and non health related community placements?

GUIDANCE FOR PUBLISHING QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative research is becoming increasingly accepted and published in pharmacy and medical journals. Some journals and publishers have guidelines for presenting qualitative research, for example, the British Medical Journal 9 and Biomedcentral . 10 Medical Education published a useful series of articles on qualitative research. 11 Some of the important issues that should be considered by authors, reviewers and editors when publishing qualitative research are discussed below.

Introduction.

A good introduction provides a brief overview of the manuscript, including the research question and a statement justifying the research question and the reasons for using qualitative research methods. This section also should provide background information, including relevant literature from pharmacy, medicine, and other health professions, as well as literature from the field of education that addresses similar issues. Any specific educational or research terminology used in the manuscript should be defined in the introduction.

The methods section should clearly state and justify why the particular method, for example, face to face semistructured interviews, was chosen. The method should be outlined and illustrated with examples such as the interview questions, focusing exercises, observation criteria, etc. The criteria for selecting the study participants should then be explained and justified. The way in which the participants were recruited and by whom also must be stated. A brief explanation/description should be included of those who were invited to participate but chose not to. It is important to consider “fair dealing,” ie, whether the research design explicitly incorporates a wide range of different perspectives so that the viewpoint of 1 group is never presented as if it represents the sole truth about any situation. The process by which ethical and or research/institutional governance approval was obtained should be described and cited.

The study sample and the research setting should be described. Sampling differs between qualitative and quantitative studies. In quantitative survey studies, it is important to select probability samples so that statistics can be used to provide generalizations to the population from which the sample was drawn. Qualitative research necessitates having a small sample because of the detailed and intensive work required for the study. So sample sizes are not calculated using mathematical rules and probability statistics are not applied. Instead qualitative researchers should describe their sample in terms of characteristics and relevance to the wider population. Purposive sampling is common in qualitative research. Particular individuals are chosen with characteristics relevant to the study who are thought will be most informative. Purposive sampling also may be used to produce maximum variation within a sample. Participants being chosen based for example, on year of study, gender, place of work, etc. Representative samples also may be used, for example, 20 students from each of 6 schools of pharmacy. Convenience samples involve the researcher choosing those who are either most accessible or most willing to take part. This may be fine for exploratory studies; however, this form of sampling may be biased and unrepresentative of the population in question. Theoretical sampling uses insights gained from previous research to inform sample selection for a new study. The method for gaining informed consent from the participants should be described, as well as how anonymity and confidentiality of subjects were guaranteed. The method of recording, eg, audio or video recording, should be noted, along with procedures used for transcribing the data.

Data Analysis.

A description of how the data were analyzed also should be included. Was computer-aided qualitative data analysis software such as NVivo (QSR International, Cambridge, MA) used? Arrival at “data saturation” or the end of data collection should then be described and justified. A good rule when considering how much information to include is that readers should have been given enough information to be able to carry out similar research themselves.

One of the strengths of qualitative research is the recognition that data must always be understood in relation to the context of their production. 1 The analytical approach taken should be described in detail and theoretically justified in light of the research question. If the analysis was repeated by more than 1 researcher to ensure reliability or trustworthiness, this should be stated and methods of resolving any disagreements clearly described. Some researchers ask participants to check the data. If this was done, it should be fully discussed in the paper.

An adequate account of how the findings were produced should be included A description of how the themes and concepts were derived from the data also should be included. Was an inductive or deductive process used? The analysis should not be limited to just those issues that the researcher thinks are important, anticipated themes, but also consider issues that participants raised, ie, emergent themes. Qualitative researchers must be open regarding the data analysis and provide evidence of their thinking, for example, were alternative explanations for the data considered and dismissed, and if so, why were they dismissed? It also is important to present outlying or negative/deviant cases that did not fit with the central interpretation.