- Open access

- Published: 19 February 2023

Big five model personality traits and job burnout: a systematic literature review

- Giacomo Angelini 1

BMC Psychology volume 11 , Article number: 49 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

13 Citations

42 Altmetric

Metrics details

Job burnout negatively contributes to individual well-being, enhancing public health costs due to turnover, absenteeism, and reduced job performance. Personality traits mainly explain why workers differ in experiencing burnout under the same stressful work conditions. The current systematic review was conducted with the PRISMA method and focused on the five-factor model to explain workers' burnout risk.

The databases used were Scopus, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and PsycINFO. Keywords used were: “Burnout,” “Job burnout,” “Work burnout,” “Personality,” and “Personality traits”.

The initial search identified 3320 papers, from which double and non-focused studies were excluded. From the 207 full texts reviewed, the studies included in this review were 83 papers. The findings show that higher levels of neuroticism (r from 0.10** to 0.642***; β from 0.16** to 0.587***) and lower agreeableness (r from − 0.12* to − 0.353***; β from − 0.08*** to − 0.523*), conscientiousness (r from -0.12* to -0.355***; β from − 0.09*** to − 0.300*), extraversion (r from − 0.034** to − 0.33***; β from − 0.06*** to − 0.31***), and openness (r from − 0.18*** to − 0.237**; β from − 0.092* to − 0.45*) are associated with higher levels of burnout.

Conclusions

The present review highlighted the relationship between personality traits and job burnout. Results showed that personality traits were closely related to workers’ burnout risk. There is still much to explore and how future research on job burnout should account for the personality factors.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Burnout: origin, evolution, and definition.

Since the 1970s, when most research in occupational health psychology was focused on industrial workers, studies on burnout have seen a substantial increase. Initially considered a syndrome exclusively linked to helping professions [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ], burnout has been adopted by a broader range of human services professionals [ 5 , 6 ]. Job burnout’s construct has undergone considerable conceptual and methodological attention in the last fifty years. Nowadays, job burnout is considered a multidimensional construct closely referred to as repeated exposure to work-related stress (e.g., [ 7 ]). According to the original theoretical framework, job burnout is defined chiefly as referring to feelings of exhaustion and emotional fatigue, cynicism, negative attitudes toward work, and reduced professional efficacy [ 6 ].

While the relationship between socio-demographic, organizational, and occupational factors and burnout syndrome have received significant attention, the relationship between burnout and individual factors, such as personality, is less explored (for a meta-analysis, see [ 8 ]).

Therefore, it is interesting to investigate whether there is sufficiently convincing evidence to indicate that personality factors play a role in predictors of job burnout. Investigating to what extent personality factors predict job burnout could include a measure of these factors in the selection processes of workers. At the same time, it could also allow preventive actions to support all those at risk of job burnout. This literature review involved a search for cohort studies published since 1993, which used self-report measures of personality traits and job burnout and investigated the relationships between these variables.

Personality and job burnout

In the past, research on this issue has been chiefly haphazard and scattered ([ 9 , 10 ] for a meta-analysis; [ 11 ]). Indeed, personality has often been evaluated in terms of positive or negative affectivity (respectively, e.g., [ 12 , 13 ]), adopting the type A personality model (e.g., [ 14 ]), or the concept of psychological hardiness [ 15 ]. More recently, burnout research focused on the relationship between workers’ personalities measured by the Big Five personality model and their burnout syndrome [ 16 , 17 ]. More specifically, neuroticism (e.g., [ 18 , 19 ]) and extraversion personalities (e.g., [ 20 ]) were abundantly investigated in the scientific panorama (for review; [ 21 ]).

Personality traits according to the five-factor model (FFM)

Since the twentieth century, scholars and researchers have increasingly dedicated themselves to studying this topic, given the importance assumed by personality in the psychological panorama. One of the most famous and relevant approaches to the study of character is the five-factor model (FFM) of personality traits (often referred to as the “Big Five”) proposed by McCrae & Costa [ 22 , 23 ]. As a multidimensional set, personality traits include individuals’ emotions, cognition, and behavior patterns [ 23 – 26 ]. Furthermore, the FFM is the most robust and parsimonious model adopted to understand personality traits and behavior reciprocal relationships [ 27 ] due to two main reasons: its reliability across ages and cultures [ 28 , 29 ] and its stability over the years [ 30 ]. According to several scholars, the FFM consists of five personality traits: agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness [ 23 , 25 , 26 , 31 ]. Agreeableness refers to being cooperative, sympathetic, tolerant, and forgiving towards others, avoiding competition, conflict, pressuring, and using force [ 32 ]. Conscientiousness is reflected in being precise, organized, disciplined, abiding by principles and rules, and working hard to achieve success [ 33 ]. Extraversion is related to the quantity and intensity of individual social interaction characteristics. It is displayed through higher degrees of sociability, assertiveness, talkativeness, and self-confidence [ 32 ]. Neuroticism reflects people’s loss of emotional balance and impulse control. It is characterized by a prevalence of negative feelings and anxiety that are attempted to cope with through maladaptive coping strategies, such as delay or denial [ 29 , 34 ]. Openness is reflected in intellectual curiosity, open-mindedness, untraditionality and creativity, the preference for independence, novelty, and differences [ 33 , 35 ]. In the last thirty years, the Big Five model has been recognized as a primary representation of salient and non-pathological aspects of personality, the alteration of which contributes to the development of personality disorders [ 36 – 40 ], such as antisocial, borderline, and narcissistic personality disorders [ 41 ].

Although the role of the work environment as a predictor of burnout has been broadly documented (e.g., [ 5 , 6 , 11 ]), it cannot be neglected the effect that personality has on the development of this syndrome. Even reducing or eliminating stressors related to the work environment, some people may still experience high levels of burnout (e.g., [ 42 ]). For this reason, it is necessary to know the associations between personality traits and job burnout to identify the workers most prone to burnout and implement more risk-protection activities. Consequently, based on the literature presented above, this PRISMA review aimed to shed some light on the role that personality traits according to the Five Factors Model—Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Neuroticism, and Openness—play in the development of job burnout.

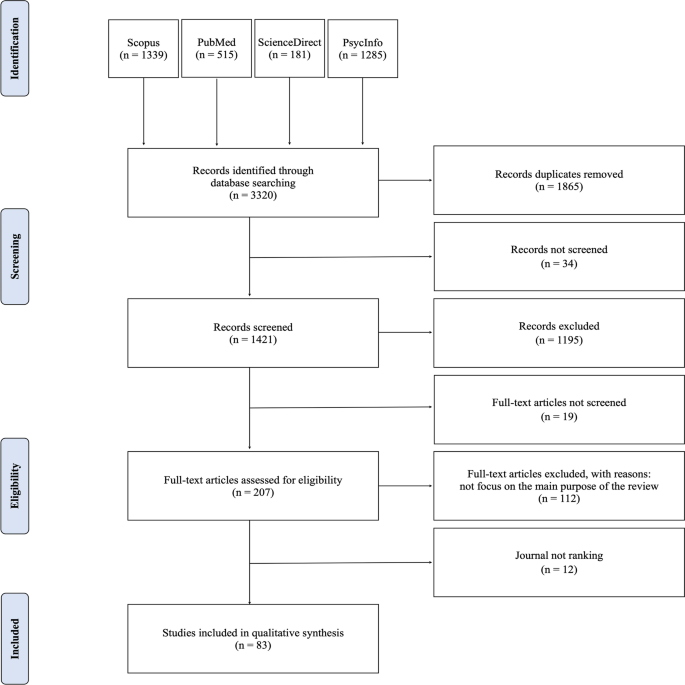

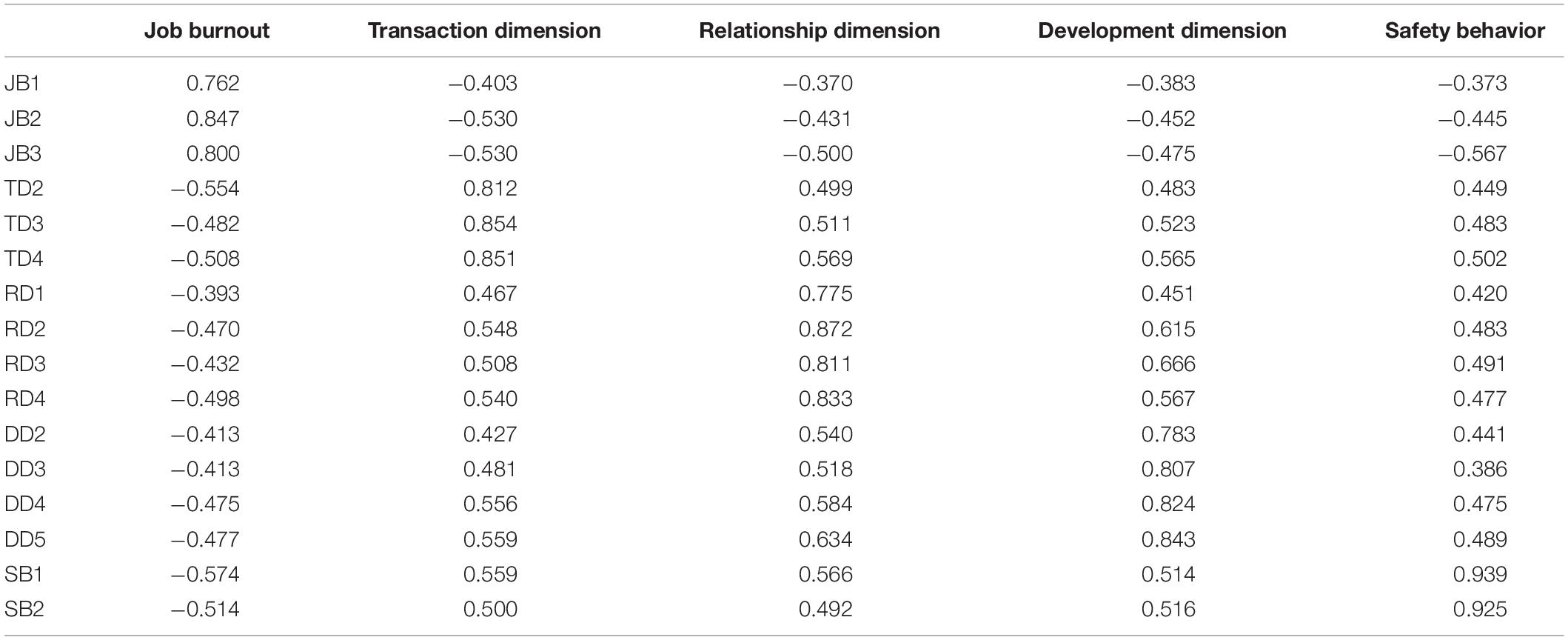

Protocol and registration

The systematic analysis of the relevant literature for this review followed procedures based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes (PRISMA) process [ 43 – 45 ], a checklist of 27 items which together with a flow-chart (see Fig. 1 ) constitute the most rigorous guide to systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis. The systematic analysis of the relevant literature for this review followed procedures based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes (PRISMA) process [ 43 – 45 ].

Diagram flow of information through the different phases of a systematic review

The PRISMA method intends to provide a checklist tool for creating systematic reviews of quality literature.

Eligibility criteria

The study was conducted by extensively searching articles published before June 30th, 2021 (time of research), limited to papers in journals published in English. Review articles, meta-analyses, book chapters, and conference proceedings were excluded. Articles investigating the relationship between personality traits and job burnout in any field of employment, except athletic and ecclesiastical, were included.

Information sources

The databases PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, and ScienceDirect, were used for the systematic search of relevant studies applying the following keywords:

* Burnout * AND * Personality *

* Burnout * AND * Personality traits *

* Job burnout * AND * Personality *

* Work burnout * AND * Personality *

* Job burnout * AND * Personality traits *

* Work burnout * AND * Personality traits *

The initial search identified 3320 papers. The details (title; author/s; year of publication; journal) of the documents identified for inclusion across all inquiries were placed in a separate excel document. After removing duplicates, reviewing titles, and reading abstracts (see Fig. 1 ), the papers were reduced to 207, of which full-text records were read. Studies selected in total for inclusion in this review were limited to the five dimensions of the Big Five Factor model [ 46 ] and were 83 papers.

Study selection

As shown by the Prisma Diagram flow (Fig. 1 ), a total of 83 studies were identified for inclusion in the review. Via the initial search process have been identified total of 3320 studies (Scopus, n = 1339; PubMed, n = 515; ScienceDirect, n = 181; PsycInfo, n = 1285). After excluding duplicates, the remaining studies were 1455 of these 1421 records analyzed, and 1195 were discarded. After reviewing the abstracts, these papers did not meet the criteria. Of the remaining 226 full texts, the 207 papers available were examined in more detail, and it emerged that 112 studies did not meet the inclusion criteria as described. Furthermore, to ensure that only studies that had received peer review and met certain quality indicators were included, the SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) was inspected. SCImago considers the reputation and quality of a journal on citations, based on four quartiles used to classify journals from the highest (Q1) to the lowest (Q4). As suggested by Peters and colleagues [ 47 ], SCImago represents a widely accepted measure of the quality of journals and reduces the possibility of including in systematic reviews papers that do not meet certain quality indices. Based on this, 12 papers were excluded. Finally, 83 studies were included in the systematic review that met the inclusion criteria. Of the articles included in the review, more than half (60%) are published in journals indexed as Q1. The others were in Q2 (28%), Q3 (5%), and finally Q4 (7%).

Study characteristics

Participants.

The included studies have involved 36,627 participants. Based on the inclusion criteria, all reviewed studies included (1) adult samples (18 years or older), (2) workers from the general population rather than clinical samples, (3) regardless of the type of work, and for most studies (4) more female participants than male (female, 57.79%; male, 42.21%). Six studies did not include participants’ demographic information [ 48 – 53 ]. The above percentages refer to the available data (n = 33,299).

The sample consisted of about 26% Teachers or Professors, 22% Nurses, 11% Physicians with various specializations, 10% Policemen, 10% Health professionals, 8% Clerks, of which about 5% worked with IT. Furthermore, the sample was made up of almost 3% Drivers, and less than 2% ICT Manager and Firefighters. Finally, about 9% of the sample carried out different types of jobs.

Countries of collecting data

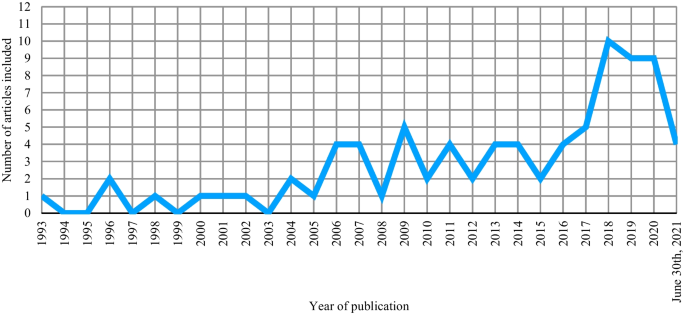

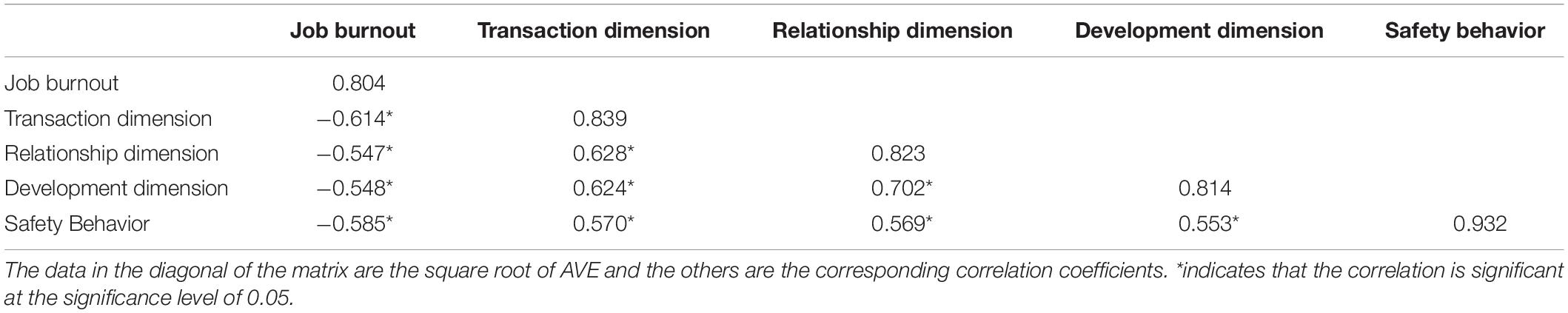

The 83 articles included in this review have been published between 1993 and 2021 (see Fig. 2 ). In terms of geographic dispersion, more than half of the studies (n = 45; 54.21%) were conducted in Europe (France, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherland, Norway, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK). In contrast, the others were conducted either in America (n = 18; Canada, Jamaica, and the USA), Asia (n = 13; China, India, Iran, Israel, Jordan, and Singapore), Africa (n = 6; Nigeria, South Africa, and Turkey) and Oceania (n = 1; Australia).

Research records achieving the inclusion criteria from 1993 to June 30th, 2021

A summary of information about the general characteristics and main methodological properties of all included 83 studies is reported in Table 1 .

Concerning the key methodological features of studies, all studies reviewed involved empirical and quantitative research design. Most of the papers included (n = 73; 88%) in this review were cross-sectional and descriptive studies, except nine (11%) papers presenting longitudinal studies [ 50 , 54 – 61 ]. Furthermore, one paper (1%; [ 62 ]) presented two different studies within it, one cross-sectional and the other longitudinal.

Most of the studies, 84% (n = 70), assessed job burnout via the Maslach Burnout Inventory, both in the original version (MBI; [ 3 , 63 ]), and in the subsequent versions [ 64 , 65 ], or its adaptation [ 66 ]. The other studies, 16% (n = 13), used tools other than MBI, but which share with it the theoretical approach to job burnout and the dimensions of (emotional) exhaustion, depersonalization or cynicism, and reduced personal or professional accomplishment (see Table 1 ). Five papers used the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure (SMBM; [ 67 ]), four the Oldenburg burnout inventory (OLBI; [ 68 , 69 ]), one the Bergen Burnout Indicator (BBI; [ 70 ]), one the Brief Burnout Questionnaire (CBB; [ 71 ]), one the Burnout Measure [ 72 ] and one the Short Burnout Measure (SBM; [ 73 ]).

According to the Big Five model, the outcome of the analyzed studies was the correlational and regressive between work burnout and personality traits. The data of the models in which the personality traits mediated or moderated the relationships with other variables, which were not the study’s object, were not considered in this review. Concerning personality, all included studies were compatible with the "Big Five" model [ 74 , 75 ] and investigated traits of Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Neuroticism, and Openness.

In detail, about 28% (n = 23) of the studies used the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; [ 33 , 76 – 79 ]), 17% (n = 14) have used the Big Five Inventory (BFI; [ 31 , 75 , 80 – 83 ]), one of which is the 10-item version [ 84 ]. Yet, 10% (n = 8) used the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ; [ 85 , 86 ]), with one study with the revised version [ 87 ], and four studies with the revised and short version [ 88 ]. Furthermore, 7% (n = 6) involved the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP; [ 89 , 90 ]), with two studies adopting the mini version [ 91 ], while another 7% (n = 6) involved the NEO-Personality Inventory (NEO-PI; [ 81 ]), with five studies adopting the revised version. About 5% (n = 4) has used the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI; [ 92 ]), 4% (n = 3) has used the Big Five mini markers scale [ 93 ], and 4% (n = 3) involved the Big Five Questionnaire (BFQ; [ 94 ]) Finally, about 2% (n = 2) has submitted the Five Factor Personality Inventory (FFPI; [ 95 ]), and 2% (n = 2) used the Mini Markers Inventory [ 93 ].

The remaining studies, about 14% (n = 12), used the following tools: the Basic Character Inventory (BCI; [ 96 ]), the Big Five factor markers [ 90 ], the Big Five measure-Short version [ 32 , 97 ], the Big Five Plus Two questionnaire-Short version [ 98 ], the Brief Big five Personality Scale [ 92 ], the Basic Traits Inventory (BTI; [ 99 ]), the Comprehensive Personality and Affect Scales (COPAS; [ 100 ]), the Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI; [ 101 ]), the Freiburg Personality Inventory (FPI; [ 102 ]), the M5-120 Questionnaire [ 103 ], the Minimal Redundant Scales (MRS-30; [ 104 ][ 104 ]), and the Personality Characteristics Inventory (PCI; [ 105 , 106 ]).

All instruments included in the studies were in line with the “Big Five” domains [ 26 ], such as e.g., the NEO-FFI and the NEO-PI, widely used measures of the Big Five [ 81 ], the dimensions of the TIPI and the IPIP [ 89 , 92 ], or the factors of the EPQ and the EPI, compatible with the Big Five model [ 107 , 108 ].

Risk of bias in individual studies

Study design, sampling, and measurement bias were assessed regarding the evaluation risk of bias in each study. Table 2 summarizes the limits reported in each study. Where not registered, no limitations related to the study were referred by the authors of the original studies.

Study design bias

Although most of the studies (89%) have a cross-sectional design, this review reported in the table (see Table 2 ) this bias only on the studies that highlighted this as a weakness (50%). Cross-sectional methods are cheap to conduct, agile for both the researcher and the participant, and can give answers to many research questions [ 109 ]. At the same time, however, since it is a one-time measurement, it does not allow us to test dynamic and progressive effects to conclude the causal relationships among variables.

Three longitudinal studies reported a shortness [ 56 , 58 ] or longness [ 55 ] time-lag between the first and successive administrations. The time length between the study’s waves is an essential issue in longitudinal research methodology. The time interval between the first and following measurements should correspond with the underlying causal lag (e.g., [ 110 ]). If the time lag is too short, probably the antecedent variable does not affect the outcome variable. If, on the contrary, the time lag is too long, the effect of the antecedent variable may already have disappeared. In both cases, the possibility of detecting the impact of the antecedent variable on the outcome variable may decrease.

Furthermore, it is possible that in the period between the first and subsequent measurements, several events may occur affecting the outcome. Finally, the same participant in the sample could change the condition under study (to know more, [ 177 ]). Especially in work-related studies, employees may be subject to changes in context, needs, and working hours [ 178 ]. Despite this, longitudinal designs offer substantial advantages over cross-sectional methods in examining the causal links between the variables [ 177 ].

Sampling bias

About 29% of the studies (n = 24) reported the small samples as limitation. Among these, one study that had two different samples reported a small sample only in second one [ 62 ], while another study, in investigating differences, highlighted that certain groups have a relatively small sample size and reported this as a limitation [ 140 ]. Additionally, about 10% of the studies reported having received an inadequate response rate. About 18% of the studies reported a non-probabilistic sampling as a limitation, and 6% of studies examined reported having a gender-biased sample (male/female). Other studies (13%) reported collecting data in a single organization, country, or an imbalance among workers’ categories. Finally, three studies [ 154 , 168 , 170 ] reported a cultural or geographical bias. To sum up, studies’ limitations regarding the sample characteristics may significantly impact scores’ reliability [ 179 , 180 ]. Specifically, this research’s limits prevent to generalize the findings.

Measurement and response bias

Since inclusion evaluated burnout and personality traits through self-reports that respected the previously illustrated models, all the studies examined used self-report measures. Again, only 40% report this as a limitation. Using perceptual measures, one could be subject to the Common Method Bias (CMB; [ 181 ]). The CMB occurs when the estimated relationships among variables are biased due to a unique-measure method [ 182 ]. This bias may be due to several factors, including response trends due to social desirability, similar responses of respondents due to proximity and wording of items, and similarity in the conditions of time, medium, and place of measurements [ 183 – 185 ]. These variations in responses are artificially attributed to the instrument rather than to the basic predispositions of the participants [ 181 , 186 , 187 ]. Suppose the systematic method variance is not contained. In that case, it can result in an incorrect evaluation of the scale's reliability and convergent validity, inflating the reliability estimates of correlations [ 188 ] and distorting the estimates of the effects of the predictors in the regressions [ 184 ].

Furthermore, about 5% of studies reported using single-item measures. Personality characteristics were often measured through self-reports with single items and assessed through a Likert scale [ 189 ]. This type of assessment is susceptible to social desirability (SDR; [ 184 , 185 ]), i.e., the tendency to respond coherently with what others perceive as desirable [ 190 ]. Furthermore, this type of assessment is also susceptible to acquiescent responding (ACQ; [ 191 ]), i.e., the tendency to prefer positive scores on the Likert scale, regardless of the meaning of the item [ 192 ]. Response-style-induced errors can influence reliability estimates (e.g., [ 193 , 194 ]) and overestimate or underestimate the relationships between the variables examined [ 195 ]. Despite these response biases, widely documented in the literature [ 184 – 186 , 196 – 198 ], it appears that this bias is overstated in psychological research [ 185 ]. Indeed, self-reports would seem to be the most valid measurement method for evaluating personality factors because the same participant is the most suitable person to report their personality and level of burnout [ 42 ]. Other studies (10%) reported using a poor reliability scale: employing imprecise psychometric procedures in a study is likely to distort the outcome, therefore not allowing to make inferences about an individual and creating a response bias [ 199 ]. Finally, about 16% of the studies examined reported that the study did not review all the variables relating to the constructs investigated. Table 2 also identifies some specific limitations of the studies examined, such as, e.g., the comparison between non-numerically equivalent samples [ 174 ], the long compilation time required [ 165 ], and the lack of a control group [ 57 , 138 ]. Furthermore, some studies have used tools that evaluate only a total score of burnout [ 17 ] or personality [ 54 ] Finally, other studies have focused only on individual factors, leaving out job-related and organizational factors [ 147 ].

This systematic review was conducted to identify, categorize, and evaluate the studies investigating the relationship between job burnout and personality traits addressed to date. Specifically, the interest of this review was to explore the role of personality traits as individual factors related to job burnout. To do this, only studies that analyzed the direct relationship between personality traits and job burnout were included, leaving out all those studies that investigated additional variables that could in any way mediate or moderate this relationship.

Results of the studies included

Table 3 summarizes the results, the correlation and regression indices, and the power of significance of the studies included in this review.

The results of the included studies based on the five personality traits and the association with a dimension of job burnout are discussed below. The correlations between the personality trait and the size of the job burnout report first, while subsequently those of the regressions, presenting the cross-sectional studies first, which are most of them, and then also the longitudinal ones.

As seen previously, job burnout is a multidimensional construct that consists of the individual response to stressors at work [ 3 , 9 ]. The literature has long investigated the association between organizational and occupational factors and burnout. However, a recent meta-analysis shows that there is a bidirectional relationship between occupational stressors and burnout [ 200 ]. Because the research on individual factors has been less systematic, partial, and contradictory [ 113 ], this review aimed to synthesize research evidence about the role that FFM personality traits play in the development of job burnout. To do this, 83 independent studies that used different tools to assess both job burnout and personality traits while maintaining the same reference theory were identified. The most investigated personality traits were, in order, neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience.

The present review extracted data from the reviewed studies, including (1) main characteristics of participants (including job type), (2) data collected country, (3) personality traits related to job burnout, (4) risk of bias in individual studies, and (5) methodological features of studies. As for the participants, all reviewed studies included (1) adult samples, (2) workers from the general population rather than clinical samples, (3) regardless of the type of work, and for most studies (4) more female participants than male. Based on these observations, future studies examining personality traits and work burnout should employ other samples (e.g., clinical samples) to enhance external validity.

This systematic review focused exclusively on personality traits and the relationship between them and job burnout. Results of the included studies confirmed a relationship between job burnout and the five distinct personality traits of the Big Five model [ 46 ] and that some of these were risk factors for job burnout (although not always in the same direction). A descriptive picture of the relationship between the five personality traits and job burnout will be discussed.

Agreeableness

A negative association between Agreeableness and job burnout was reported (range, r from − 0.12* to − 0.353***; β from − 0.08*** to − 0.523*). Longitudinal studies also suggest a role of Agreeableness as a protective factor of dimensions of Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and reduced Professional Accomplishment (EE; β, − 0.83*; β, − 0.48*; D; β, − 0.31*; PA; β, − 0.22*; rPA; β, − 0.28**). As seen previously, the Agreeableness trait has been described as a sense of cooperation, tolerance, and avoidance of conflict on problematic issues [ 32 ]. Agreeable individuals are warm, supportive, and good-natured [ 201 , 202 ], protecting them from feelings of frustration and emotional exhaustion [ 113 ]. Indeed, their tendency towards a positive understanding of others, coupled with interpersonal relationships based on feelings of affection and warmth [ 201 ], could protect them from developing job burnout and greater depersonalization [ 8 , 203 ]. Although most of the studies found a negative relationship between Agreeableness and job burnout, in some studies Agreeableness was positively correlated with Emotional exhaustion [ 159 ], and reduced Professional Accomplishment [ 50 , 62 ].

Conscientiousness

A negative association between Conscientiousness and job burnout was reported (range, r from − 0.12* to − 0.355***; β from − 0.09*** to − 0.300*). Longitudinal studies also suggest the role of Conscientiousness as a protective factor against Burnout (B; β, -0.21*). As seen previously, the Conscientiousness trait is reflected in precise, organized, and disciplined individuals who respect the rules and work hard to achieve success [ 33 ]. Their perseverance in work and success orientation would protect these people from developing emotional exhaustion [ 76 , 204 ] and poor personal accomplishment, as they are unlikely to perceive themselves as unproductive. Although most studies found a negative relationship between Conscientiousness and job burnout dimensions, some studies pointed out an unexpected inverse correlation between Conscientiousness and reduced Professional Accomplishment [ 60 , 62 , 143 , 159 , 166 ]. Furthermore, Conscientiousness was positively associated with Emotional exhaustion and Depersonalization [ 131 ]. This result would be due to the greater commitment and effort employed in their work, which would have greater levels of exhaustion and depersonalization [ 131 ]. Finally, another longitudinal study [ 56 ] attributes Conscientiousness as a negative predictor role for the dimensions of Personal/Professional Accomplishment. However, the authors do not provide reasons for this discordant result from the literature.

Extraversion

A negative association between Extraversion and job burnout was reported (range, r from − 0.034** to − 0.33***; β from − 0.06*** to − 0.31***). Longitudinal studies also suggest the role of Extraversion as a protective factor against burnout and its dimension of Exhaustion (B; β, − 0.16*; EE; β, − 0.26*). As seen previously, the Extraversion trait has been identified as the intensity of social interaction and the level of self-esteem of individuals [ 32 ]. People with higher levels of extraversion appear positive, cheerful, optimistic, and have more likely to experience positive emotions [ 206 ]. This positive view of their level of job-related self-efficacy [ 207 ], often associated with the interpersonal bonds they tend to create [ 208 ] can protect outgoing individuals from experiencing high levels of emotional exhaustion. On the contrary, introverted individuals tend to experience greater feelings of helplessness and lower levels of ambition [ 204 ], which instead results in a risk factor for job burnout. Although the negative association is the most frequent, some studies have found a directly proportional association between Burnout and Extraversion [ 54 ], Cynicism [ 127 , 173 ], and reduced Professional Accomplishment [ 50 , 60 , 62 , 143 , 146 , 159 ]. Again, the authors do not provide reasons for this discordant result from the literature.

Neuroticism

A positive association between Neuroticism and job burnout was reported (range, r from 0.10** to 0.642***; β from 0.16** to 0.587***). Longitudinal studies also suggest a role of Neuroticism as a predictor of Burnout and its extent of Exhaustion, while predicting a decrease in Professional Accomplishment (B; β, 0.21*; EE; β, 0.31***; β, 0.15**; β, 0.19**; PA; β, − 0.23**). As seen previously, it is possible to define Neuroticism as the inability of people to control their impulses and manage their emotional balance. Neurotic people experience a series of feelings of insecurity, anxiety, anger, and depression [ 25 , 76 , 204 ] that they try to manage through maladaptive coping strategies, such as delay or denial [ 29 , 34 ]. These characteristics of the personality trait of Neuroticism would interfere with job functioning and satisfaction, operating a negative "filter" that magnifies the impact of adverse events (see [ 209 ]) and constitutes a significant risk factor for job burnout [ 8 , 174 ]. Feelings of anxiety and nervousness could lead them more easily to experience higher levels of emotional exhaustion, and by focusing on more aspects of their work, they are more likely to manifest depersonalization. Although most studies report a positive association between Neuroticism and Burnout [ 164 ], Burnout [ 159 , 169 ], Depersonalization [ 133 , 159 ], and reduced Professional Accomplishment [ 60 , 62 , 126 ]. Ye and colleagues [ 164 ] tie this result to the Chinese cultural situation, whereby the observed greater sense of responsibility and discipline could reduce the effects of extroversion on job burnout. Farfán and colleagues [ 169 ], on the contrary, link this result to the tendency of the neurotic personality trait to use rationalization as a defense against job burnout. Unlike most of the studies included in this review, some results show a negative association between Neuroticism and Burnout [ 159 , 164 ], Emotional exhaustion, and Depersonalization [ 155 ]. Furthermore, a study indicates that Neuroticism is positively associated with reduced Personal/Professional Accomplishment [ 131 ]. Finally, in the longitudinal study by Armon and colleagues [ 54 ], Neuroticism even seems to protect against Emotional exhaustion. The authors explain the association over time of Neuroticism with job burnout as due to an underrepresentation in the measurement scales used or the moderating effect of gender on these associations [ 159 ].

A negative association between Openness and job burnout was reported (range, r from − 0.18*** to − 0.237**; β from − 0.092* to − 0.45*). Longitudinal studies have suggested the role of Openness as a protective factor of reduced Professional Accomplishment (rPA; β, 0.10*). As seen previously, individuals with high levels of Openness tend to be more intellectually curious about novelty and open-minded and have a predisposition to independence [ 35 , 76 , 202 ]. These characteristics protect individuals from experiencing discomfort, experiencing novelty and failures as opportunities [ 203 ], and protecting them from job burnout from emotional exhaustion. Conversely, when faced with stressors at work, less open individuals can adopt quick but suboptimal strategies, such as depersonalization [ 8 ]. Although most of the studies found a negative relationship between Openness and job burnout, five studies found a positive correlation between Openness and Emotional exhaustion [ 54 , 122 ] and Depersonalization [ 159 ], while negative with Personal/Professional Accomplishment [ 62 , 131 , 159 ]. The authors do not provide reasons for this discordant result from the literature. Other studies instead have found a positive association between Openness and all dimensions of Burnout [ 116 ]: Exhaustion [ 131 , 173 ], Depersonalization [ 131 ], and reduced Personal/Professional Accomplishment [ 142 ]. Finally, the longitudinal study by Ghorpade and colleagues [ 120 ] attributes Openness to the role of the positive predictor of Emotional exhaustion. According to the authors, this result could be attributed to the work of the professors (Professors) which, requiring a greater openness to listening to students' different problems and encouraging different positions in them, could increase emotional exhaustion.

The findings of most of the studies reviewed indicate that individuals who have higher levels of neuroticism and lower agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness to experience are more prone to experiencing job burnout. However, the few studies that show other results than this theoretical line cannot explain the conflicting results. Some authors adduce these results to a measurement bias (e.g., [ 159 ]) or sample characteristics (e.g., [ 120 ]) but fail to explain the reason for this relationship and believe that it is due to further variables to be explored.

Limitations

Although the literature review was conducted as rigorously as possible, the search strategy was limited to four scientific search engines. Furthermore, it was impossible to find all the relevant studies if the search terms were not mentioned in the articles' titles, abstracts, or keywords. Therefore, some related papers might be missed due to the selected terms. Furthermore, the search included only studies published in English, thus excluding relevant studies in other languages. Additionally, gray literature was not included in the study, and therefore, it may not have been considered essential data contained in non-peer-reviewed studies, unpublished theses, and dissertation studies. Furthermore, one of the exclusion criteria was the journal ranking of SCImago. Although this is a widely accepted and recognized measure to reduce the possibility of including in systematic reviews papers that do not meet certain quality indices [ 47 ], they may not have been considered relevant data. In addition, the Big Five model [ 46 ] was used as a conceptual model of reference to compare the results of the studies on job burnout. Studies that did not include the Big Five models or that explored the relationship between Burnout and personality disorders (e.g., Antisocial Personality Disorder, Narcissistic Personality Disorder, Borderline Personality Disorder, etc.) were therefore not examined in this study. Restricting studies to a single conceptual model of personality was necessary to focus the review, but at the same time, it limited our investigation. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of the study samples' work type, burnout measurement tools, and personality traits prevented comparing results across studies. Finally, despite precautions to reduce selection bias, confounding, and measurement bias, no studies have addressed reverse causality problems in the relationship between personality traits and burnout. Although the cross-sectional research design does not allow us to investigate the causal links between personality and burnout, an answer to the existence of this link is offered by the longitudinal studies included in the review. This type of study demonstrates that personality traits play a role in the development of burnout, but future research must investigate this relationship, especially with the help of longitudinal studies that can reduce the problems related to reverse causality.

The findings obtained in the present review highlight the importance of examining the role of personality traits in the development of job burnout syndrome. At the same time, it is possible to observe how scientific evidence places us in front of a picture that is not fully defined. In line with Guthier's meta-analysis [ 200 ], the findings of this review highlight the need for expanding job stress theories focusing more on the role that personality plays in burnout.

I am convinced of the value of this review in directing future empirical research on job burnout, especially in the light of new approaches to burnout as a multi-component factor (see [ 210 , 211 ]). Even more future research will have the task of encouraging the use of methodologies that evaluate personality traits in work contexts. An assessment of personality traits and continuous monitoring of occupational stress levels (e.g., [ 212 ]) could help identify the people who are most likely to develop burnout syndrome to prevent or limit its damage. Future research should improve understanding and intervention on burnout, too often limited by universal approaches that have neglected the uniqueness of the antecedents of burnout [ 213 ]. Some traits related to burnout predict work outcomes such as job performance, job satisfaction, and turnover [ 203 , 214 – 218 ]. It is, therefore, necessary to investigate the antecedents of Burnout to provide implications practices for jobs and organizations.

Availability of data and materials

As this is a systematic review of the literature, this study indicates the information to obtain all data analyzed in the databases used. However, the datasets used during the current study remain available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Freudenberger HJ. Staff burn-out. J Soc Issues. 1974;30:159–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x .

Article Google Scholar

Freudenberger HJ. The staff burn-out syndrome in alternative institutions. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1975;12:73–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0086411 .

Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2:99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205 .

Schaufeli WB, Maslach C, Marek T. Professional burnout: recent developments in theory and research. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203741825

Maslach C, Leiter MP. The truth about burnout: how organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. 1997.

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Demerouti E, Bakker A, Nachreiner F, Ebbinghaus M. From mental strain to burnout. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2002;11:423–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320244000274 .

Swider BW, Zimmerman RD. Born to burnout: a meta-analytic path model of personality, job burnout, and work outcomes. J Vocat Behav. 2010;76:487–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.01.003 .

Cordes CL, Dougherty TW. A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Acad Manag Rev. 1993;18:621–56. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1993.9402210153 .

Kahill S. Symptoms of professional burnout: a review of the empirical evidence. Can Psychol. 1988;29:284–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079772 .

Lee RT, Ashforth BE. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81:123–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.2.123 .

Iverson RD, Olekalns M, Erwin PJ. Affectivity, organizational stressors, and absenteeism: a causal model of burnout and its consequences. J Vocat Behav. 1998;52:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1996.1556 .

Bellani ML, Furlani F, Gnecchi M, Pezzotta P, Trotti EM, Bellotti GG. Burnout and related factors among HIV/AIDS health care workers. AIDS Care. 1996;8:207–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540129650125885 .

Ganster DC, Type A. Behavior and occupational stress. J Organ Behav Manage. 1987;8:61–84. https://doi.org/10.1300/J075v08n02_05 .

Rush MC, Schoel WA, Barnard SM. Psychological resiliency in the public sector: “hardiness” and pressure for change. J Vocat Behav. 1995;46:17–39. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1995.1002 .

Ruggieri RA, Crescenzo P, Iervolino A, Mossi PG, Boccia G. Predictability of big five traits in high school teacher burnout. Detailed study through the disillusionment dimension. Epidemiol Biostat Public Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.2427/12923 .

Pérez-Fuentes M, Molero Jurado M, Martos Martínez Á, Gázquez LJ. Burnout and engagement: personality profiles in nursing professionals. J Clin Med. 2019;8:286. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030286 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Azeem SM. Conscientiousness, neuroticism and burnout among healthcare employees. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci. 2013. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i7/68 .

Bianchi R. Burnout is more strongly linked to neuroticism than to work-contextualized factors. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:901–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.015 .

Sulea C, van Beek I, Sarbescu P, Virga D, Schaufeli WB. Engagement, boredom, and burnout among students: basic need satisfaction matters more than personality traits. Learn Individ Differ. 2015;42:132–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.08.018 .

Hartmann É, Mathieu C. The relationship between workaholism, burnout and personality: a literature review. Sante Ment Que. 2017;42:197–218.

McCrae RR, Costa PT. Discriminant validity of NEO-PIR facet scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1992;52:229–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316449205200128 .

McCrae RR, Costa PT. Personality in adulthood: a five-factor theory perspective. 2003.

Barrick MR, Mount MK. The big five personality dimensions and job performance: a meta-analysis. Pers Psychol. 1991;44:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x .

Digman JM. Personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model. Annu Rev Psychol. 1990;41:417–40. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.002221 .

Goldberg LR. An alternative “description of personality”: the big-five factor structure. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59:1216–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.6.1216 .

Poropat AE. A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:322–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014996 .

Digman JM. Higher-order factors of the Big Five. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:1246–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1246 .

McCrae RR, Costa PT. Personality trait structure as a human universal. Am Psychol. 1997;52:509–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.5.509 .

Costa PT, McCrae RR. Personality in adulthood: a six-year longitudinal study of self-reports and spouse ratings on the NEO Personality Inventory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:853–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.853 .

John OP, Robins RW, Pervin LA. Handbook of personality: theory and research. New York; 2008.

McCrae RR, Costa PT. Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52:81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81 .

Costa PT, McCrae RR. Neo personality inventory-revised (NEO PI-R). Odessa; 1992.

Carver CS, Connor-Smith J. Personality and coping. Annu Rev Psychol. 2010;61:679–704. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352 .

Johnson JA, Ostendorf F. Clarification of the five-factor model with the Abridged Big Five Dimensional Circumplex. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:563–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.3.563 .

Krueger RF, Derringer J, Markon KE, Watson D, Skodol AE. Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1879–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711002674 .

Trull TJ, Widiger TA. Dimensional models of personality: the five-factor model and the DSM-5 . Dialog Clin Neurosci. 2013;15:135–46. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.2/ttrull .

Widiger TA, Costa PT. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality: rationale for the third edition. In: Widiger TA, Costa PT, editors. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality. 3rd ed. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2013. p. 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/13939-001 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Widiger TA, Simonsen E. Alternative dimensional models of personality disorder: finding a common ground. J Pers Disord. 2005;19:110–30. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.19.2.110.62628 .

Watson D, Clark LA, Chmielewski M. Structures of personality and their relevance to psychopathology: ii. Further articulation of a comprehensive unified trait structure. J Pers. 2008;76:1545–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00531.x .

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington; 2013.

Alarcon G, Eschleman KJ, Bowling NA. Relationships between personality variables and burnout: a meta-analysis. Work Stress. 2009;23:244–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370903282600 .

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4 .

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906 .

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 .

McCrae RR, Costa PT, Wiggins JS. The five-factor model of personality: theoretical perspectives. New York: Guilford Press; 1996.

Google Scholar

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18:2119–26. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167 .

Deary IJ, Blenkin H, Agius RM, Endler NS, Zealley H, Wood R. Models of job-related stress and personal achievement among consultant doctors. Br J Psychol. 1996;87:3–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1996.tb02574.x .

Harizanova S, Stoyanova R, Mateva N. Do personality characteristics constitute the profile of burnout-prone correctional officers? Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6:1912–7. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2018.328 .

McManus I, Keeling A, Paice E. Stress, burnout and doctors’ attitudes to work are determined by personality and learning style: a twelve year longitudinal study of UK medical graduates. BMC Med. 2004;2:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-2-29 .

Perry SJ, Witt LA, Penney LM, Atwater L. The downside of goal-focused leadership: the role of personality in subordinate exhaustion. J Appl Psychol. 2010;95:1145–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020538 .

Zellars KL, Hochwarter WA, Perrewe PL, Hoffman N, Ford EW. Experiencing job burnout: the roles of positive and negative traits and states. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004;34:887–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02576.x .

Zellars KL, Perrewé PL. Affective personality and the content of emotional social support: coping in organizations. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:459–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.459 .

Armon G, Shirom A, Melamed S. The big five personality factors as predictors of changes across time in burnout and its facets. J Pers. 2012;80:403–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00731.x .

de Looff P, Didden R, Embregts P, Nijman H. Burnout symptoms in forensic mental health nurses: results from a longitudinal study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28:306–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12536 .

Gan T, Gan Y. Sequential development among dimensions of job burnout and engagement among IT employees. Stress Health. 2014;30:122–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2502 .

Goddard R, O’Brien P, Goddard M. Work environment predictors of beginning teacher burnout. Br Educ Res J. 2006;32:857–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920600989511 .

Hildenbrand K, Sacramento CA, Binnewies C. Transformational leadership and burnout: the role of thriving and followers’ openness to experience. J Occup Health Psychol. 2018;23:31–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000051 .

Hudek-Knežević J, Kalebić Maglica B, Krapić N. Personality, organizational stress, and attitudes toward work as prospective predictors of professional burnout in hospital nurses. Croat Med J. 2011;52:538–49. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2011.52.538 .

Mills LB, Huebner ES. A prospective study of personality characteristics, occupational stressors, and burnout among school psychology practitioners. J Sch Psychol. 1998;36:103–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(97)00053-8 .

Sterud T, Hem E, Lau B, Ekeberg Ø. A comparison of general and ambulance specific stressors: predictors of job satisfaction and health problems in a nationwide one-year follow-up study of Norwegian ambulance personnel. Jo Occup Med Toxicol. 2011;6:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6673-6-10 .

Castillo-Gualda R, Herrero M, Rodríguez-Carvajal R, Brackett MA, Fernández-Berrocal P. The role of emotional regulation ability, personality, and burnout among Spanish teachers. Int J Stress Manag. 2019;26:146–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000098 .

Maslach C, Jackson SE. MBI: Maslach Burnout Inventory; manual. research. Palo Alto: University of California; 1986.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. MBI: Maslach burnout inventory. Sunnyvale: Scarecrow Education; 1996.

Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C, Jackson SE. The Maslach burnout inventory-general survey. In: Consulting psychologists, editor. MBI manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto; 1996.

Friedman IA. Turning our schools into a healthier workplace: bridging between professional self-efficacy and professional demands. In: Understanding and preventing teacher burnout. Cambridge University Press; 1999. p. 166–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511527784.010

Shirom A, Melamed S. A comparison of the construct validity of two burnout measures in two groups of professionals. Int J Stress Manag. 2006;13:176–200. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.13.2.176 .

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Vardakou I, Kantas A. The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: a multitrait-multimethod analysis. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2003;19:12. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.19.1.12 .

Demerouti E, Mostert K, Bakker AB. Burnout and work engagement: a thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. J Occup Health Psychol. 2010;15:209–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019408 .

Matthiesen SB, Dyregrov A. Empirical validation of the Bergen burnout indicator. Int J Psychol. 1992;27:497–497.

Jiménez BM, Rodríguez RB, Alvarez AM, Caballero TM. La evaluación del burnout: problemas y alternativas: el CBB como evaluación de los elementos del proceso. 1997.

Pines A, Aronson E. Career burnout: causes and cures. 1988.

Malach-Pines A. The burnout measure, short version. Int J Stress Manag. 2005;12:78–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.12.1.78 .

Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. Am Psychol. 1993;48:26–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.1.26 .

John OP, Srivastava S. The Big-Five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. (1999).

Costa PT, McCrae RR. The NEO personality inventory manual. Odessa; 1985.

Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO PI/FFI manual supplement for use with the NEO Personality Inventory and the NEO Five-Factor Inventory. 1989.

Costa PT, McCrae RR. The revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa; 1992.

Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO PI-R manual: klinisk. København; 2004.

John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL. Big five inventory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991. https://doi.org/10.1037/t07550-000 .

Costa PT, McCrae RR. The five-factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. J Pers Disord. 1992;6:343–59. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.1992.6.4.343 .

Benet-Martínez V, John OP. Los Cinco Grandes across cultures and ethnic groups: Multitrait-multimethod analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and English. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:729–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.729 .

John OP, Naumann LP, Soto CJ. Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In: Handbook of personality: theory and research. The Guilford Press; 2008. p. 114–58.

Rammstedt B, John OP. Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10-item short version of the Big Five inventory in English and German. J Res Pers. 2007;41:203–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001 .

Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the eysenck personality inventory. London; 1964.

Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the eysenck personality questionnaire (junior & adult). 1975.

Eysenck HJ. Creativity, personality and the convergent-divergent continuum. In: Critical creative processes. Hampton Press; 2003. p. 95–114.

Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the eysenck personality scales (EPS Adult). London; 1991.

Goldberg LR. A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. Pers psychol Eur. 1999;7:7–28.

Goldberg LR. International personality item pool. 2001.

Donnellan MB, Oswald FL, Baird BM, Lucas RE. The mini-IPIP scales: tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychol Assess. 2006;18:192–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192 .

Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, Swann WB. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J Res Pers. 2003;37:504–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1 .

Saucier G. Mini-markers: a brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar big-five markers. J Pers Assess. 1994;63:506–16. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6303_8 .

Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Borgogni L, Perugini M. The, “big five questionnaire”: a new questionnaire to assess the five factor model. Pers Individ Dif. 1993;15:281–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(93)90218-R .

Hendriks AJ, Hofstee WKB, De Raad B. The five-factor personality inventory (FFPI). Pers Individ Dif. 1999;27:307–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00245-1 .

Torgersen S. Hereditary-environmental differentiation of general neurotic, obsessive, and impulsive hysterical personality traits. ACTA Genet Med et Gemellol Twin Res. 1980;29:193–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001566000007935 .

Sager KL, Gastil J. Exploring the psychological foundations of democratic group deliberation: personality factors, confirming interaction, and democratic decision making. Commun Res Rep. 2002;19:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090209384832 .

Benet V, Waller NG. The Big Seven factor model of personality description: evidence for its cross-cultural generality in a Spanish sample. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:701–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.701 .

Taylor N, de Bruin GP. Basic traits inventory. Johannesburg; 2006.

Lubin B, van Whitlock R. Development of a measure that integrates positive and negative affect and personality: the comprehensive personality and affect scales. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58:1135–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10042 .

Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the eysenck personality inventory. San Diego; 1968.

Fahrenberg J, Hampel R, Selg H. Das Freiburger Persönlichkeitsinventar. Göttingen; 1970.

Johnson JA. Screening Massively Large Data Sets For Non-Responsiveness. In: Group University of Groningen, editor. Web-Based Personality Inventories Invited talk to the joint Bielefeld-Groningen Personality Research. Netherlands; (2001).

Ostendorf F. Sprache und Persönlichkeitsstruktur: Zur Validität des Fünf-Faktoren-Modells der Persönlichkeit. Sprache und Persönlichkeitsstruktur [Language and structure of personality: The validity of the Five Factor Model of personality]. Regensburg; (1990).

Mount MK, Barrick MR. Manual for the personal characteristics inventory. Libertyville; 1995.

Mount MK, Barrick MR. The personal characteristics inventory manual. Libertyville; 2002.

Goldberg LR, Rosolack TK. The Big Five factor structure as an integrative framework: an empirical comparison with Eysenck’s PEN model. In: Halverson CF Jr, Kohnstamm GA, Martin RP, Halverson CF, Kohnstamm GA, editors. The developing structure of temperament and personality from infancy to adulthood. East Sussex: Psychology Press; 1994. p. 7–35.

Markon KE, Krueger RF, Watson D. Delineating the structure of normal and abnormal personality: an integrative hierarchical approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88:139–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.139 .

Spector PE. Do Not cross me: optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. J Bus Psychol. 2019;34:125–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-09613-8 .

Ployhart RE, Vandenberg RJ. Longitudinal research: the theory, design, and analysis of change. J Manage. 2010;36:94–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309352110 .

Manlove EE. Multiple correlates of burnout in child care workers. Early Child Res Q. 1993;8:499–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2006(05)80082-1 .

Deary IJ, Agius RM, Sadler A. Personality and stress in consultant psychiatrists. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1996;42:112–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/002076409604200205 .

Zellars KL, Perrewe PL, Hochwarter WA. Burnout in health care: the role of the five factors of personality. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30:1570–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02456.x .

de Vries J, van Heck GL. Fatigue: relationships with basic personality and temperament dimensions. Pers Individ Dif. 2002;33:1311–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00015-6 .

Cano-García FJ, Padilla-Muñoz EM, Carrasco-Ortiz MÁ. Personality and contextual variables in teacher burnout. Pers Individ Dif. 2005;38:929–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.06.018 .

Burke RJ, Berge Matthiesen S, Pallesen S. Workaholism, organizational life and well-being of Norwegian nursing staff. Career Dev Int. 2006;11:463–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430610683070 .

Langelaan S, Bakker AB, van Doornen LJP, Schaufeli WB. Burnout and work engagement: Do individual differences make a difference? Pers Individ Dif. 2006;40:521–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.07.009 .

Mostert K, Rothmann S. Work-related well-being in the South African Police Service. J Crim Justice. 2006;34:479–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2006.09.003 .

Bahner AD, Berkel LA. Exploring burnout in batterer intervention programs. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22:994–1008. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260507302995 .

Ghorpade J, Lackritz J, Singh G. Burnout and personality. J Career Assess. 2007;15:240–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072706298156 .

Kim HJ, Shin KH, Umbreit WT. Hotel job burnout: the role of personality characteristics. Int J Hosp Manag. 2007;26:421–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2006.03.006 .

Teven JJ. Teacher temperament: correlates with teacher caring, burnout, and organizational outcomes. Commun Educ. 2007;56:382–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520701361912 .

Leon SC, Visscher L, Sugimura N, Lakin BL. Person-job match among frontline staff working in residential treatment centers: the impact of personality and child psychopathology on burnout experiences. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78:240–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013946 .

Chung MC, Harding C. Investigating burnout and psychological well-being of staff working with people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour: the role of personality. J Appl Res Intell Disabil. 2009;22:549–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00507.x .

de Hoogh AHB, den Hartog DN. Neuroticism and locus of control as moderators of the relationships of charismatic and autocratic leadership with burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94:1058–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016253 .

Gandoy-Crego M, Clemente M, Mayán-Santos JM, Espinosa P. Personal determinants of burnout in nursing staff at geriatric centers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;48:246–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2008.01.016 .

Kim HJ, Shin KH, Swanger N. Burnout and engagement: a comparative analysis using the Big Five personality dimensions. Int J Hosp Manag. 2009;28:96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.06.001 .

Taormina RJ, Kuok ACH. Factors related to casino dealer burnout and turnover intention in Macau: implications for casino management. Int Gambl Stud. 2009;9:275–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459790903359886 .

Barford SW, Whelton WJ. Understanding burnout in child and youth care workers. Child Youth Care Forum. 2010;39:271–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-010-9104-8 .

Ghorpade J, Lackritz J, Singh G. Personality as a moderator of the relationship between role conflict, role ambiguity, and burnout. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2011;41:1275–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00763.x .

Salami SO. Job stress and burnout among lecturers: personality and social support as moderators. Asian Soc Sci. 2011. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v7n5p110 .

Zimmerman RD, Boswell WR, Shipp AJ, Dunford BB, Boudreau JW. Explaining the pathways between approach-avoidance personality traits and employees’ job search behavior. J Manage. 2012;38:1450–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310396376 .

de la Fuente-Solana EI, Extremera RA, Pecino CV, de La Fuente GRC. Prevalence and risk factors of burnout syndrome among Spanish police officers. Psicothema. 2013;25:488–93. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2013.81 .

Garbarino S, Cuomo G, Chiorri C, Magnavita N. Association of work-related stress with mental health problems in a special police force unit. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002791. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002791 .

Hurt AA, Grist CL, Malesky LA, McCord DM. Personality traits associated with occupational ‘burnout’ in ABA therapists. J Appl Res Intell Disabil. 2013;26:299–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12043 .

Lin Q, Jiang C, Lam TH. The relationship between occupational stress, burnout, and turnover intention among managerial staff from a Sino-Japanese joint venture in Guangzhou, China. J Occup Health. 2013;55:458–67. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.12-0287-OA .

Reinke K, Chamorro-Premuzic T. When email use gets out of control: Understanding the relationship between personality and email overload and their impact on burnout and work engagement. Comput Human Behav. 2014;36:502–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.075 .

Taycan O, Taycan SE, Çelik C. Relationship of burnout with personality, alexithymia, and coping behaviors among physicians in a semiurban and rural area in Turkey. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2014;69:159–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338244.2013.763758 .

Yilmaz K. The relationship between the teachers’ personality characteristics and burnout levels. Anthropologist. 2014;18:783–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2014.11891610 .

Cañadas-De la Fuente GA, Vargas C, San Luis C, García I, Cañadas GR, de la Fuente EI. Risk factors and prevalence of burnout syndrome in the nursing profession. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:240–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.07.001 .

Srivastava SC, Chandra S, Shirish A. Technostress creators and job outcomes: theorising the moderating influence of personality traits. Inf Syst J. 2015;25:355–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12067 .

Ang SY, Dhaliwal SS, Ayre TC, Uthaman T, Fong KY, Tien CE, et al. Demographics and personality factors associated with burnout among nurses in a Singapore tertiary hospital. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6960184 .

Iorga M, Soponaru C, Hanganu B, Ioan B-G. The burnout syndrome of forensic pathologists. The influences of personality traits, job satisfaction and environmental factors. Rom J Legal Med. 2016;24:325–32. https://doi.org/10.4323/rjlm.2016.325 .

Vaulerin J, Colson SS, Emile M, Scoffier-Mériaux S, d’Arripe-Longueville F. The big five personality traits and french firefighter burnout. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58:e128–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000679 .

Zhou J, Yang Y, Qiu X, Yang X, Pan H, Ban B, et al. Relationship between anxiety and burnout among Chinese physicians: a moderated mediation model. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157013. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157013 .

de la Fuente-Solana EI, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Cañadas GR, Albendín-García L, Ortega-Campos E, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA. Burnout and its relationship with personality factors in oncology nurses. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;30:91–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2017.08.004 .

Geuens N, van Bogaert P, Franck E. Vulnerability to burnout within the nursing workforce—the role of personality and interpersonal behaviour. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:4622–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13808 .

Iorga M, Socolov V, Muraru D, Dirtu C, Soponaru C, Ilea C, et al. Factors influencing burnout syndrome in obstetrics and gynecology physicians. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9318534 .

Lovell B, Brown R. Burnout in U.K. prison officers: the role of personality. Prison J. 2017;97:713–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885517734504 .

Ntantana A, Matamis D, Savvidou S, Giannakou M, Gouva M, Nakos G, et al. Burnout and job satisfaction of intensive care personnel and the relationship with personality and religious traits: an observational, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;41:11–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.02.009 .

al Shbail M, Salleh Z, Mohd Nor MN. Antecedents of burnout and its relationship to internal audit quality. Bus Econ Horiz. 2018;14:789–817. https://doi.org/10.15208/beh.2018.55 .

Bergmueller A, Zavgorodnii I, Zavgorodnia N, Kapustnik W, Boeckelmann I. Relationship between burnout syndrome and personality characteristics in emergency ambulance crew. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2018;48:404–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11055-018-0578-4 .

Bianchi R, Mayor E, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E. Burnout and depressive symptoms are not primarily linked to perceived organizational problems. Psychol Health Med. 2018;23:1094–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2018.1476725 .

Iorga M, Dondas C, Sztankovszky L-Z, Antofie I. Burnout syndrome among hospital pharmacists in Romania. Farmacia. 2018;66:181–6.

Tang L, Pang Y, He Y, Chen Z, Leng J. Burnout among early-career oncology professionals and the risk factors. Psychooncology. 2018;27:2436–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4847 .

Tatalovic Vorkapic S, Skocic Mihic S, Josipovic M. Early childhood educators’ personality and competencies for teaching children with disabilities as predictors of their professional burnout. Socijal Psihijatr. 2018;46:390–405. https://doi.org/10.24869/spsih.2018.390 .

Yao Y, Zhao S, Gao X, An Z, Wang S, Li H, et al. General self-efficacy modifies the effect of stress on burnout in nurses with different personality types. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:667. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3478-y .

Zaninotto L, Rossi G, Danieli A, Frasson A, Meneghetti L, Zordan M, et al. Exploring the relationships among personality traits, burnout dimensions and stigma in a sample of mental health professionals. Psychiatry Res. 2018;264:327–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.076 .

Bahadori M, Ravangard R, Raadabadi M, Hosseini-Shokouh SM, Behzadnia MJ. Job stress and job burnout based on personality traits among emergency medical technicians. Trauma Mon. 2019;24:24–31. https://doi.org/10.30491/TM.2019.104270 .

Brown PA, Slater M, Lofters A. Personality and burnout among primary care physicians: an international study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:169–77. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S195633 .

de la Fuente-Solana E, Cañadas G, Ramirez-Baena L, Gómez-Urquiza J, Ariza T, Cañadas-De la Fuente G. An explanatory model of potential changes in burnout diagnosis according to personality factors in oncology nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030312 .

Farfán J, Peña M, Topa G. Lack of group support and burnout syndrome in workers of the state security forces and corps: moderating role of neuroticism. Medicina (B Aires). 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55090536 .

Khedhaouria A, Cucchi A. Technostress creators, personality traits, and job burnout: a fuzzy-set configurational analysis. J Bus Res. 2019;101:349–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.04.029 .

Ye L, Liu S, Chu F, Zhang Q, Guo M. Effects of personality on job burnout and safety performance of high-speed rail drivers in China: the mediator of organizational identification. J Transp Saf Secur. 2021;13:695–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439962.2019.1667931 .

Banasiewicz J, Zaręba K, Rozenek H, Ciebiera M, Jakiel G, Chylińska J, et al. Adaptive capacity of midwives participating in pregnancy termination procedures: polish experience. Health Psychol Open. 2020;7:205510292097322. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102920973229 .

Bhowmick S, Mulla Z. Who gets burnout and when? the role of personality, job control, and organizational identification in predicting burnout among police officers. J Police Crim Psychol. 2021;36:243–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-020-09407-w .

de Vine JB, Morgan B. The relationship between personality facets and burnout. SA J Ind Psychol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v46i0.1786 .

Dionigi A. The relationship between, burnout, personality, and emotional intelligence in clown doctors. Humor. 2020;33:157–74. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2018-0018 .

Farfán J, Peña M, Fernández-Salinero S, Topa G. The moderating role of extroversion and neuroticism in the relationship between autonomy at work, burnout, and job satisfaction. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:8166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218166 .

Liu X-Y, Kwan HK, Zhang X. Introverts maintain creativity: a resource depletion model of negative workplace gossip. Asia Pac J Manag. 2020;37:325–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9595-7 .

Mahoney CB, Lea J, Schumann PL, Jillson IA. Turnover, burnout, and job satisfaction of certified registered nurse anesthetists in the United States: role of job characteristics and personality. AANA J. 2020;88:39–48.

PubMed Google Scholar

Malka M, Kaspi-Baruch O, Segev E. Predictors of job burnout among fieldwork supervisors of social work students. J Soc Work. 2021;21:1553–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017320957896 .

Tasic R, Rajovic N, Pavlovic V, Djikanovic B, Masic S, Velickovic I, et al. Nursery teachers in preschool institutions facing burnout: are personality traits attributing to its development? PLoS One. 2020;15:e0242562. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242562 .

Bianchi R, Manzano-García G, Rolland J-P. Is burnout primarily linked to work-situated factors? A relative weight analytic study. Front Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.623912 .

de la Fuente-Solana EI, Pradas-Hernández L, González-Fernández CT, Velando-Soriano A, Martos-Cabrera MB, Gómez-Urquiza JL, et al. Burnout syndrome in paediatric nurses: a multi-centre study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031324 .

de la Fuente-Solana EI, Suleiman-Martos N, Velando-Soriano A, Cañadas-De la Fuente GR, Herrera-Cabrerizo B, Albendín-García L. Predictors of burnout of health professionals in the departments of maternity and gynaecology, and its association with personality factors: a multicentre study. J Clin Nurs. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15541 .

Taris TW, Kompier MAJ. Cause and effect: optimizing the designs of longitudinal studies in occupational health psychology. Work Stress. 2014;28:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2014.878494 .

Wrzesniewski A, Dutton JE. Crafting a job: revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad Manag Rev. 2001;26:179–201. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4378011 .

Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Psychology press; 1983.

Henson RK, Kogan LR, Vacha-Haase T. A reliability generalization study of the teacher efficacy scale and related instruments. Educ Psychol Meas. 2001;61:404–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131640121971284 .

Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol Bull. 1959;56:81–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046016 .

Podsakoff PM, Organ DW. Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J Manage. 1986;12:531–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408 .

Edwards JR. To prosper, organizational psychology should … overcome methodological barriers to progress. J Organ Behav. 2008;29:469–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.529 .

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:539–69. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452 .

Spector PE. Method variance in organizational research. Organ Res Methods. 2006;9:221–32.

Doty DH, Glick WH. Common methods bias: Does common methods variance really bias results? Organ Res Methods. 1998;1:374–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105284955 .

Jakobsen M, Jensen R. Common method bias in public management studies. Int Public Manag J. 2015;18:3–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2014.997906 .

Le H, Schmidt FL, Putka DJ. The multifaceted nature of measurement artifacts and its implications for estimating construct-level relationships. Organ Res Methods. 2009;12:165–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428107302900 .

Kreitchmann RS, Abad FJ, Ponsoda V, Nieto MD, Morillo D. Controlling for response biases in self-report scales: forced-choice vs. psychometric modeling of likert items. Front Psychol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02309 .

Kuncel NR, Tellegen A. A conceptual and empirical reexamination of the measurement of the social desirability of items: implications for detecting desirable response style and sale development. Pers Psychol. 2009;62:201–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2009.01136.x .

Paulhus DL. Measurement and control of response bias. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS, editors. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1991. p. 17–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-590241-0.50006-X .

Weijters B, Baumgartner H, Schillewaert N. Reversed item bias: an integrative model. Psychol Methods. 2013;18:320–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032121 .

Navarro-González D, Lorenzo-Seva U, Vigil-Colet A. How response bias affects the factorial structure of personality self-reports. Psicothema. 2016;28:465–70. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.113 .

Abad FJ, Sorrel MA, Garcia LF, Aluja A. Modeling general, specific, and method variance in personality measures: results for ZKA-PQ and NEO-PI-R. Assessment. 2018;25:959–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116667547 .

Soto CJ, John OP. Optimizing the length, width, and balance of a personality scale: How do internal characteristics affect external validity? Psychol Assess. 2019;31:444–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000586 .

Antonakis J. On doing better science: from thrill of discovery to policy implications. Leadersh Q. 2017;28:5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.01.006 .

Fuller CM, Simmering MJ, Atinc G, Atinc Y, Babin BJ. Common methods variance detection in business research. J Bus Res. 2016;69:3192–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008 .

Spector PE, Brannick MT. Common method variance or measurement bias? The problem and possible solutions. In: Buchanan D, Bryman A, editors. The Sage handbook of organizational research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication; 2009. p. 346–62.

Furr M. Scale construction and psychometrics for social and personality psychology. 2011.

Guthier C, Dormann C, Voelkle MC. Reciprocal effects between job stressors and burnout: a continuous time meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2020;146:1146–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000304 .

Goldberg LR. The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychol Assess. 1992;4:26–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.26 .

Peabody D, Goldberg LR. Some determinants of factor structures from personality-trait descriptors. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57:552–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.552 .

Zimmerman RD. Understanding the impact of personality traits on individuals’ turnover decision: a meta-analytic path model. Pers Psychol. 2008;61:309–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00115.x .

Saucier G, Ostendorf F. Hierarchical subcomponents of the Big Five personality factors: a cross-language replication. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76:613–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.4.613 .

Evans JD. Straightforward statistics for the behavioral sciences. 1996.