Designing an ideal Case Report Form (CRF) for Clinical Research

- January 6, 2024

A Case Report Form (CRF), is a printed, optical or electronic document designed to record all of the protocol required information to be reported to the sponsor on each trial subject, as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

Designing a Case Report Form (CRF) is vital for accurate clinical trial data collection. It should align with the study protocol, regulatory requirements, and aid in testing hypotheses. The CRF design, whether paper or electronic, is a key quality step, influencing data quality, regulatory compliance, and site workflow.

Paper-based CRF or e-CRF?

Two types of Case Report Forms (CRFs) are used in clinical research: traditional paper CRFs and electronic CRFs (eCRFs).

Paper CRFs suit small or varied studies, while eCRFs are preferred for large, similar-design studies due to their time efficiency and ease of administration. In the global context, eCRFs are favored, promoting large multicentric studies simultaneously. eCRFs offer automated data entry, reducing errors, and facilitating quick data cleaning with built-in edit checks. They enable instant query resolution, leading to faster regulatory submissions and approvals. However, eCRFs face challenges such as technology availability, investigator motivation, software maintenance complexities, and high costs, limiting their widespread adoption.

Steps in designing a Case Report Form (CRF):

Designing a Case Report Form (CRF) is a scientific art requiring consideration of end-users. Including all essential sections is crucial, as incomplete or inaccurate data can be costly during analysis. Establishing a standard operating procedure and following best practices are recommended for effective CRF preparation. Standardized CRF design is crucial to meet the needs of various data handlers, ensuring user-friendliness and capturing legible, consistent, and valid data. Adhering to design standards improves data quality, simplifies analysis, and reduces query generation.

The CRF’s informative header and footer are customizable, typically including protocol ID, site code, subject ID, patient initials, investigator’s signature, date of signature, version number, and page number. To enhance readability and accurate data entry, a clean and uncluttered layout is preferred.

To optimize the clarity and functionality of a Case Report Form (CRF), it is essential to adhere to certain design principles:

- Consistent Formatting: Maintain uniform formats, font styles, and sizes throughout the CRF booklet.

- Layout Considerations: Select an appropriate layout (portrait, landscape, or combination) for enhanced readability.

- Clear and Concise Language: Use clear and concise language for questions, prompts, and instructions to minimize ambiguity.

- Visual Cues: Provide visual cues, like boxes, to guide data entry and format within the CRF.

- Answer Recording: Limit the use of circling answers; instead, utilize check boxes for clarity.

- Skip Patterns: Clearly define skip patterns to maintain connectivity between pages and reduce confusion.

- Answer Boxes or Lines: Use boxes or lines to guide where responses should be recorded, visually differentiating entries.

- Column Separation: Differentiate columns with thick lines for improved organization.

- Bold and Italicized Instructions: Emphasize instructions using bold and italicized text.

- Minimize Free Text: Reduce free-text responses to streamline data entry.

- Question Density: Position a specified density of questions on each page to avoid overcrowding.

- Consistent Page Numbering: Maintain consistent page numbering if necessary for easy reference.

- Avoid “Check All That Apply”: Minimize assumptions by avoiding the “check all that apply” format.

- Specify Units and Decimal Places: Clearly indicate the unit of measurement and the number of decimal places.

- Standard Data Format: Use a standard data format (e.g., dd/mm/yyyy) throughout the CRF.

- Precoded Answer Sets: Employ precoded answer sets where applicable for consistency.

- Module/Section Integrity: Do not split modules or sections across pages to ensure cohesive data collection.

- NCR Copies: Utilize “no carbon required (NCR)” copies for exact replicas of the CRF.

- Instructional Guidance: Provide clear instructions with page numbers where data should be entered for specific events or modules.

At present, several customizable softwares or templates are also available to develop a good CRF. Researchers are advised to check within their organization for available data management software packages. Common options include REDCap , while alternatives like OpenClinica l might also be accessible.

Example of a good CRF:

Figure 1: Illustrating a well-designed and poorly designed data fields imparting the significance of visual cues to help the site personnel to understand the format

Figure 2 : A sample case report form (CRF) page. An adverse event page of CRF is depicted showing codes, and skips questions

CRF Completion Guidelines:

A CRF completion guideline is a study-specific document designed to assist investigators in step-by-step completion of the CRF, aligned with the protocol. There is no standardized template, but it should be created to facilitate easy and legible completion by site personnel.

Recommendations in the guidelines should be in accordance with the requirements of:

● TGA: ICH Guideline for Good Clinical Practice

● Medicines & Healthcare products, Regulatory Agency: ‘GXP’ Data Integrity Guidance and Definitions

In conclusion, addressing challenges in Case Report Form (CRF) design necessitates collaborative planning, clear objectives, and adherence to standard templates. Key considerations include avoiding extraneous data, eliminating duplication, and prioritizing user-friendly designs for enhanced accuracy. The incorporation of user feedback and best practices plays a vital role in optimizing data quality and overall efficiency in clinical research studies.

- Clinical research data

Related Posts

Navigating the regulatory landscape in nepal's clinical research.

- October 31, 2023

Navigating the Regulatory Landscape in Nepal’s Clinical Research: A Comprehensive Guide

Best Practices in Data Management for Clinical Trials: Ensuring Accuracy and Compliance

- Data managament

- January 4, 2024

Data in clinical trials encompass a comprehensive set of information collected during the study, including participant demographics, medical history, treatment outcomes, adverse events, and other relevant measurements.

Cardiovascular Trials in the Digital Age: Wearables and Remote Monitoring

- January 22, 2024

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) stand as the foremost global cause of mortality, claiming an estimated 17.

- Data Dictionary

- Printing Instruments

- Project Bookmarks

CRF Design Guide

The following has been taken from SOP 38b AD 1, for more information please click here

Definitions

A Case Report Form (CRF), according to the ICH GCP guidelines, is ‘a printed, optical, or electronic document designed to record all the protocol required information to be reported to the sponsor on each trial subject.’ ICH GCP section 1.11

It is the tool for the collection of all clinical research data on each individual subject in a clinical trial.

When designing case report forms, the Data Protection Act – 1998 should be take into consideration.

Responsibility

The Sponsor delegates the responsibility of designing The CRF, ensuring it matched the approved protocol, and collects sufficient information to answer the research questions and evidence protocol and GCP compliance to the Chief Investigator.

Please take into consideration the following points below when designing the CRF for your trial.

The principles laid out in this guidance apply to both Paper CRFs and e-CRFs.

Patient identifiable data vs anonymised data

The definitions given below are taken from the DOH Confidentiality NHS Code of Practice November 2003, which can be downloaded from the DOH website.

General information

It is of the utmost importance that the information captured in the CRF matches that listed in the final version of the protocol. All the data elements/points within the CRF must support the identifiable objectives of the protocol, in the form of the primary and secondary endpoints. It should serve to ensure the eligibility as well as the safety of the patient. It should also demonstrate compliance with study procedures and where possible adherence to GCP.

It is important that the CRFs SHOULD NOT collect any additional data that is not to be analysed or outside the requirements of the study aims.

The intention of the CRF is to collect complete and pertinent data and to ensure consistency and standardisation with regards to data collection. Therefore, it is necessary that these forms are clear, easy to use and collect the relevant information.

The Chief Investigator (CI) or delegate is responsible for the design and development of CRFs. Instructions should be given to all participating sites on how to complete the CRF (paper or electronic CRF) to ensure data is collected in a standardised fashion and meets the data protection act.

A CRF completion guide may be useful in a multi-centre study. As per JRMO SOP on Site activation and SOP 38 Trial data management systems a training log should exist to document training has been completed.

It is vital that it is documented within the site delegation log in which members of the study team have been appropriately trained with regards to their study role, including the protocol and their role requirements, including the correct completion of the CRFs.

Development

Elements to be considered in CRF Design:

- CRFs SHOULD NOT contain any patient identifiable material – When Patients are entered/randomised onto a study, they should be allocated a code number known as the patient identifier which can include their initials alongside an allocated number generally pertaining to their entry onto the study.

- Patients Initials (the first letter of the patient’s forename, middle and surname constitute their initials e.g. John Edward Smith, the initials JES should be utilised. If the patient does not have a middle name, simply use a dash e.g. William Knight, the initials W-K should be utilised.)

- CRFs should be appropriately versioned and dated – if there are changes to be made to these documents, the version number and date should be updated accordingly, especially in the case of a protocol amendment that may lead to changes in the design of the CRFs.

- CRFs should be consistent with the protocol, as previously detailed.

- It is mandatory to record all visits and procedures that the protocol requests. This includes completion of questionnaires, participant diaries and telephone follow ups. This should include recording of dates.

- CRFs should enable to accurate capture of dose calculations and administration (what was taken / given to the participant, when and what dose).

- Avoid duplication of data collection – for example collecting the patient’s age and their date of birth. (Only ask for DoB if you feel this is specifically needed often ages at consent is enough).

- Where ever possible avoid free text. Free text is very difficult to analyse.

- Where possible tick box or drop down options should be given. This particular option should be exhaustive – in that there should be a N/A or Other box option, when applicable. Where the ‘Other’ box is an appropriate option, there should allocated space for further information to be collected.

- For data points where actual values are to be captured, the number of boxes/spaces given should be adequate and if appropriate, reflect the number of decimal places desired. Please remember that there should be no blank spaces left on the CRF once completed.

- The measurement unit should be specified.

- Lab values should be detailed/referenced (with regards to units), if there are any conversions that are necessary (e.g. in multi-site studies - local lab unit of measurement variation), there should be space in which this can be completed and documented, with the original figure alongside the conversion factor.

- Each set of entries made on the CRF should be signed off and dated by the trained and authorised individual completing the CRF. The Chief Investigator or the Principal Investigator (if multi-site) should then review the data entered into the CRF, validating their review with a signature and date of review on each CRF page (or at the end of each visit, but page signature is suggested) for every trial subject in their care.

Considerations for Layout

The following guidance should be taken into consideration with regards to the appearance of the document.

- CRFs should be well aligned, and the arrangement of data fields should be clear, logical and user friendly. Consistency with regards to formatting should also be adhered to with regards alignment, margins, spacing and fonts.

- Particular attention to the header and footer of these documents should be taken, with the study code as well as the patient number pertaining to the study to be highly visible and be considered to be a standard.

- All CRF pages should be paginated, with headers and footers with the study code and participant code (on every page) to be highly visible to ensure if any pages get misplaced, they can be easily reunited and all the data is recovered.

- There should be space for the person making the clinical assessment as to the patient’s viability to participate within the study or/and the person who is completing the CRF to sign and date the page. This acts as verification and confirmation that the data collected is accurate.

- CRF pages should be sequentially arranged in order of patient visits.

- The data fields should be arranged to ensure that they are easy to use, clear and logical.

- If in paper format consideration should be given to how the pages are to be stored within a file or are to be bound into a booklet, ensure that the margins should allow enough room for this reason.

- The separation of sections using section dividers can be used to ensure clarity and be user friendly. (For example, Visit 1 section, Visit 2 section, IMP record, concomitant medications, adverse events).

- It may be advisable in the case of multi-centre studies to incorporate other site specific identifiers to ensure it is known where the CRF pages have originated from.

Mandatory fields and forms

When creating the CRF for a BH and QMUL Sponsored CTIMPS, certain forms are considered Mandatory, and should be included in all CRFS.

These can only be omitted with written permission from the Governance Operations Manager.

These include:

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria( confirmation the participant is eligible)

- Consent details (date, version etc.)

- AE Reporting form

- Concomitant medication

- Treatment Form/Dosing and Compliance data 1

- Withdrawal/Completed study form

- Per visit and follow-ups form ( detailing dates of each visit or procedure)

- Principal Investigator sign off statement

Additional recommended forms

- Relevant Medical History

- Patient Demographics

- Physical Examination and results

- Baseline data as stipulated by the protocol

- Randomisation/registration

- Relapse/recurrence

- End of Treatment form (end result of study)

- Lab data, ECGs, etc.

Signing Off and Training

The CRF design should be reviewed and signed off by CI, and the statistician.

The CI and Statistician should check if:

- Sufficient data is being collected to answer all trial research questions.

- All data points outlined in the protocol are being collected.

- No data points are being collected that are not outlined in the protocol.

- CRF design meets with DPA and GCP.

There should be a clear, consistent procedure for the completion of the CRF pages, this should include procedures for any amendments that need to be made to the CRFs as well as instruction for corrections. This can be provided within a training session or/and instruction to be included on the CRF pages.

- Each study is individual with its own specifications, with the responsibilities that are to be allocated to trained study members documented in the site delegation log.

Completion and management

- There should be fixed timelines with regards to CRF completion after each subject’s assessment/visit, ensuring data entry is completed on a regular basis. These timelines should be adhered to, to ensure consistent data collection, maximising completeness and accuracy throughout the life cycle of the trial.

- In the case of multi centre studies, copies of the CRFs should be sent to the lead site on a regular basis to ensure that a lack of data entry does not occur.

- In the case of multi-centre studies, please ensure that ALL ORIGINAL CRFS are to be sent to the lead centre to their data management personnel for review, whilst copies are to be kept at the local sites that are participating within the study, whether it be a photocopy or an NCR copy (non carbon copy paper).

- If the lead site becomes aware of a data discrepancy documented on the CRF the lead site can raise a query raising a data clarification form/email/query (data query). This form/email/process acts as a means to request amended data to rectify the incorrect data in the CRF whilst maintaining an auditable data trail for the clinical study.

If during the study life cycle, amendments are made to the protocol that are pertinent to the data collection endpoints, there should be changes made to the CRFs to reflect this and these documents should mirror each other. Any changes that are made should be documented and version controlled and filed in the Trial Master File (TMF) and the Investigator Site File (ISF) - if the study is multi-site.

The CRFs should collect all the information reflected in the trial, relating to patient eligibility, treatments, outcomes, and endpoints, accurately matching those detailed in the protocol.

- Ensure that there are no blank spaces left. If the data at the time of completion cannot be entered, please use phrases that explain why, such as ‘unknown’, ‘missing’ and ‘test not done’. Please do not utilise ambiguous phrases as ‘not available’.

- Ensure that the data entered corresponds with what has been documented in the source data (e.g. Medical Records, ECG, and Lab Results), and that it is accurate and legible.

- If there are notable discrepancies with the source data, there should be an explanation given in the CRF and the significance noted.

- If there are Lab values outside the laboratory’s reference ranges or other range pre-identified within the study protocol, or if a value shows significant variation from one assessment to the next, the significance should be documented within the CRF along with the course of action taken.

- Each set of entries made on the CRF should be signed off and dated by the trained and authorised individual completing the CRF. The Principal Investigator should then review the data entered into the CRF, validating their review with a signature and date of review on each CRF page (or at the end of each visit, but page signature is suggested) for every trial subject in their care.

- In the case of multi centre studies, please ensure that ALL ORIGINAL data queries to be sent to the lead site, again to the relevant data management personnel for review, whilst copies are to be kept at the local sites that are participating within the study, whether it be a photocopy. Please see the diagram below to visually demonstrate the process with regards to data collection, as previously described

If there is dose escalation, reduction or modification outlined in the protocol CRF must reflect this and enable this data to be documented ↩

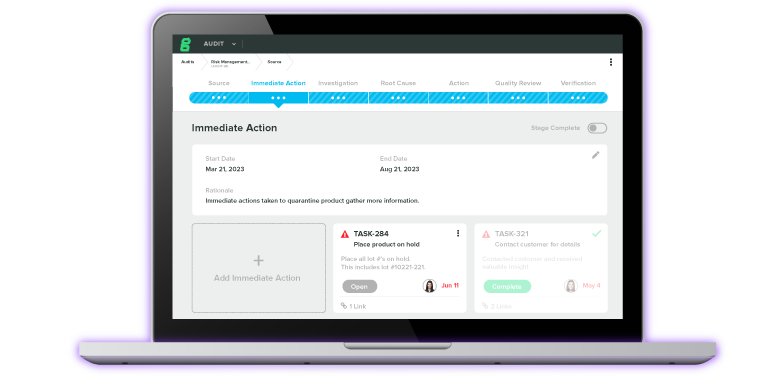

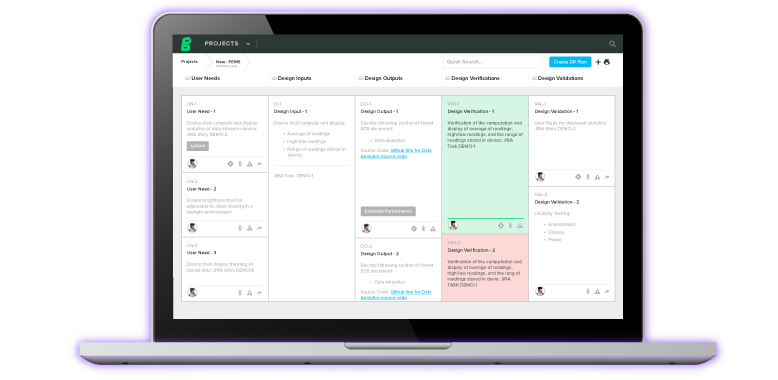

More than a Quality Management System: Tools for the entire MedTech Lifecycle.

Featured Capabilities:

Experience the #1 QMS software for medical device companies first-hand. Click through an interactive demo.

Accelerate development with integrated design control and risk software.

Schedule a custom demo of Greenlight Guru Product now.

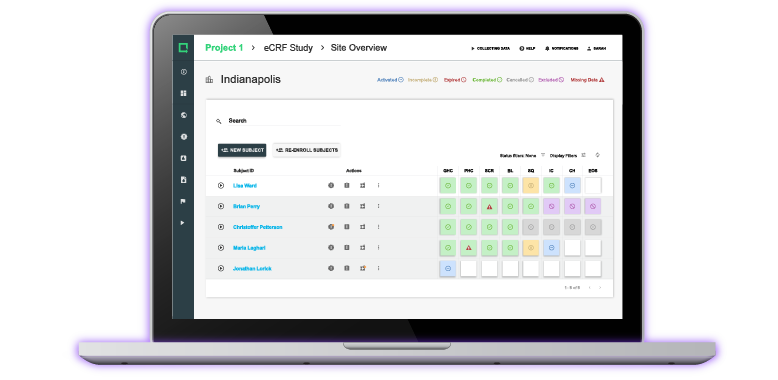

Data collection and management designed for MedTech clinical trials.

Get a personalized demo of Greenlight Guru Clinical today.

- By Initiative

- Migrating From Paper

- Managing and Assessing Risk

- Preparing for Regulatory Submissions

- Becoming Audit Ready

- Managing Postmarket Quality

- Small Business

- By Function

- Product / R&D

- ROI Calculator

- Customer Success

- Case Studies

- Checklists & Templates

- eBooks & Guides

- Content Hub

- Live & Virtual Events

- True Quality Roadshow

The Essential Guide to eCRF (Electronic Case Report Form) for Medical Devices

.png)

In clinical investigations, investigators traditionally use paper Case Report Forms (CRFs) to collect data from participating patients, including patient characteristics and demographic data, adverse events , and the results of experimental treatments.

When a study is completed, paper CRF forms are boxed and shipped from the study site to the study sponsor, where the data will be cleaned, prepared, transformed, and transcribed into a computer database prior to analysis.

Paper-based CRFs have been standard practice in clinical investigation for decades, but medical device companies in recent years are increasingly choosing to digitize the data collection process with a new kind of CRF: electronic Case Report Form (eCRF) .

In this essential guide, we’ll cover all the basics about eCRFs in clinical trials for medical device companies. You’ll learn what they are, how to design an effective eCRF, and the benefits of choosing eCRF instead of paper-based CRF for your next study.

FREE RESOURCE: Click here to download your free PDF copy of 7 best practices for how to design an electronic case report form.

What is an eCRF?

An eCRF (electronic case report form) is the digital version of a paper-based case report form - it’s a digital questionnaire completed by researchers to collect and report data from participating patients in a clinical trial.

While paper CRFs require physical storage, security, and transportation, collecting clinical data in a digital format with an eCRF means that the data can be securely uploaded to the cloud and shared with other stakeholders in near-real time.

As a result, switching from paper-based data collection to eCRF can help medical device companies execute clinical studies in less time, with less risk, and at a lower cost.

Is eCRF the same as Electronic Data Capture (EDC)?

eCRF and Electronic Data Capture (EDC) are semantically similar terms that relate to data collection in clinical studies, which explains why certain sources are using these terms interchangeably.

Still, eCRF and EDC are not the same thing and clinical study managers should understand the difference between them.

We’ve already defined eCRFs above as the digital version of a case report form that researchers will complete during a clinical trial.

An EDC system is a software solution, purpose-built to enable data collection as part of a clinical study. EDC systems allow sponsors to design eCRFs and provide a graphical user interface where researchers can complete and submit eCRFs as part of a clinical study.

EDC systems can also enable other forms of data collection, including automatic transmission from electronic health records (EHR) and connected medical devices.

Plus, EDC systems enable software-based controls on data entry and data access that help ensure the accuracy, authenticity, and security of clinical data. Click here to find out what other advantages to using an EDC system are and why it is a good idea to use an EDC made for medical devices.

Can I copy my paper CRF directly to the eCRF?

Concerned about the impact of adopting eCRF on clinical workflows? You might be wondering whether you can simply transcribe paper CRF documents into eCRF instead of requiring researchers to record data in a digital format.

You absolutely can choose to transcribe data into eCRF from paper source documents, however:

You will need to design a paper CRF and a matching eCRF to streamline the data entry process.

You will need to retain the source data in paper format to satisfy regulatory requirements.

The transcription process will introduce data entry errors that negatively impact data quality.

If your goal is to use eCRF in your study, designing your eCRF in a digital format is highly recommended, as your digital CRF can easily be transposed to a paper copy if needed. In contrast, it is often both time-consuming and costly to design a paper CRF and recreate it in a digital format.

However, we recommend designing your eCRF from scratch, instead of copying the design from the paper-based CRF. Download our eCRF template to get the design of your eCRF right.

How to design an eCRF

eCRFs are designed by clinical trial sponsors to collect data from a clinical investigation that can be used to test the experimental hypothesis and answer research questions that are relevant to the study.

A common mistake in eCRF design is trying to collect too much data. Including more data fields on your eCRF means more time and money spent on data collection, entry, preparation, and analysis. A well-designed eCRF should capture just the data needed for the study, without any time-consuming extras that lengthen the data collection process without adding anything useful.

To achieve this, trial sponsors should plan their clinical investigations and data collection activities in detail before designing an eCRF. Here’s how to start designing a high-quality eCRF:

1. Craft a Clear Hypothesis

The first step to designing an eCRF is to craft a clear research hypothesis for your clinical investigation. Your hypothesis should include a prediction for how your medical device will help patients in the treatment group.

Establishing a hypothesis is a critical step towards clarifying what data you must collect to support or refute your hypothesis, and what other data can safely be ignored in the context of your investigation.

2. Design a Statistical Analysis Plan

After establishing a hypothesis, you should prepare a Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) describing how the data you collect during the clinical trial will be analyzed. This is when you’ll list exactly what data must be collected, and when, to enable a sound analysis that will either support or refute your research hypothesis.

Your SAP may also include descriptions of specific graphs, charts, or other visuals you hope to create using the data collected in your clinical trial.

3. Define Your Data Collection Plan

A data collection plan defines the specific questions you will ask to collect the data that’s needed to support or refute your research hypothesis. You can also document how those questions will be asked and how they might be formatted on a digital case report form (eCRF).

You can download our eCRF template to help you start documenting specifications for your eCRF as part of your data collection plan.

4. Plan your Data Collection Activity

Planning data collection activities means describing how researchers will collect, capture, and store data during your clinical trial. To solidify your plan, you’ll need to document the answers to questions like:

What data is available?

What data will be collected?

How much data will be needed?

How will the data be collected?

When will the data be collected?

Who will collect the data?

Where will data be recorded or stored?

How will data be shared?

By crafting a research hypothesis and establishing clear plans for gathering and analyzing your clinical data, you should be able to avoid the common mistake of collecting more data than is needed to test your research hypothesis.

This is only one of the 7 most common pitfalls in clinical data collection for MedTech that we have identified along the years. If you want to learn how to avoid tripping over these pitfalls (you may not even know you're doing it already), we suggest you check out our blog post, here .

5. Follow 7 Principles of Good eCRF Design

SMART-TRIAL EDC gives our customers the ability to design and customize eCRFs for medical device clinical investigations, clinical performance, post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF), and post-market performance follow-up (PMPF) studies.

To share our expertise, we’ve authored a white paper detailing the most important best practices in eCRF design. In the paper, we identify the seven principles behind a Good eCRF design and how you can apply them to create a perfectly optimized eCRF for your next clinical study.

What are the benefits of eCRF vs. Paper-based Reports?

1. eliminate unnecessary data duplication.

Medical device companies doing paper-based data collection must maintain a physical copy of the original source data for security and compliance purposes. Using eCRF in clinical trials eliminates the need for data duplication and allows medical device companies to satisfy these requirements by storing data securely in the cloud with appropriate back-ups.

2. Reduce or Eliminate Transcription Errors

Paper-based CRF forms must be transcribed into a computer database before analysis, which introduces the potential for transcription errors. Collecting data electronically with eCRF eliminates transcription errors and results in better quality data.

3. Streamline the Data Collection Process

When researchers complete paper CRFs in a study, those records must be packaged, shipped, and transcribed before the data can be analyzed. With eCRFs, any data collected by researchers during a subject visit is available for review and analysis in near-real time - just as soon as it’s entered into the EDC system.

Streamlining access to data accelerates the completion of clinical studies, provides a faster feedback loop for researchers, and enhances data access for all research stakeholders.

4. Facilitate Good Clinical Compliance

Collecting clinical data with eCRF can help medical device companies facilitate good compliance with clinical investigation standards like ISO 14155:2020 . EDC software can also deliver automatic warnings and notifications to help companies comply with Good Clinical Practices (GCP) as outlined by the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH).

Greenlight Guru Clinical's EDC software offers SMS and email notifications and comes with SOP and QA templates to facilitate ISO 14155:2020 and GCP compliance .

5. Facilitate Remote Data Monitoring

Clinical study monitors are responsible for ensuring that studies proceed in compliance with the experimental protocols, GCP, and relevant regulatory requirements. They also work to ensure that the rights of subjects are protected, and that study data is accurate and complete.

Using eCRF enables monitors to remotely access documentation from the clinical study over the Internet as an alternative to supervising the study in person. Remote monitoring reduces costs and increases the efficiency of clinical studies.

6. Enable Real-Time Data Access

Data recorded on eCRF is not constrained to a single physical location. Instead, the data is uploaded to the Internet where it can be accessed almost immediately by other stakeholders with the appropriate authorization and access credentials.

7. Mitigate Security Risks of Physical Paper

Paper CRFs are subject to a number of physical risks, including loss, theft, fire and water damage. Medical device companies can eliminate these risks by collecting data with eCRF and storing the data in a secure cloud environment.

8. Preserve Clinical Data for Audits

When clinical data is collected using eCRF in clinical trials and securely stored in the cloud, a digital data trail is created and preserved for inspector audits and regulatory review.

9. Reduce the Cost of Clinical Studies

Scientific research on the impact of choosing eCRFs over paper-based data collection have suggested that eCRFs accelerate the completion of clinical studies and reduce the cost of data collection. In one research paper that analyzed data collection in 27 clinical studies between 2001 and 2011, those using eCRF had a total cost of 374€ ( 381 usd) per patient, while those with paper-based data collection cost 1,135€ (1156 USD) per patient.

Design Your eCRF and Collect Clinical Data with Greenlight Guru Clinical

Greenlight Guru Clinical (formerly SMART-TRIAL) is an EDC system that enables clinical study sponsors to digitize the process of collecting, integrating, and securely storing data for clinical investigations, in-human studies, and post-market surveillance activities.

With Greenlight Guru Clinical, medical device companies can design highly customized eCRFs , then deploy those eCRFs in clinical studies to replace paper-based data collection, eliminate the risk of transcription errors, and reduce the cost of running the study.

As the first and only electronic data capture software designed for Medical Devices and Diagnostics, Greenlight Guru Clinical provides capabilities for gathering data in clinical studies, performance studies, PMCF/PMPF studies, surveys, registries, cohorts, case series, as well as from connected devices and wearables.

Ready to learn more? Contact us for a customized demo .

Páll Jóhannesson

Páll Jóhannesson, M.Sc. in Medical Market Access, is the founder and Managing Director of Greenlight Guru Clinical (formerly SMART-TRIAL). Páll was previously the CEO of Greenlight Guru Clinical where he led the team to create the only EDC specifically made for medical devices.

Read More Posts

Fda's voluntary improvement program, the state of udi across the world, adopting ai in quality management: practical solutions for the medtech industry, subscribe to our blog.

Join 200,000+ other medical device professionals outperforming their peers.

Get your free PDF

7 principles to designing an ecrf.

.png?width=250&height=324&name=7%20Principles%20to%20Designing%20an%20eCRF%20(cover).png)

- Checklists/Templates

- Request a Demo

- Content Title Description

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

16 Data capture tools: case report form (CRF)

- Published: February 2016

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter outlines the overall design process, highlights the aspects of design that are significant for the success of the case report form (CRF) and considers the effects of electronic data capture (EDC) in the production of electronic CRFs (eCRFs). It defines the purpose and regulatory requirements in designing a CRF. The chapter describes the data to be recorded in the CRF to answer the hypothesis being posed and collect safety data. The layout and design features are reviewed ensuring an aesthetically pleasing, easy to complete format is achieved. Hint and tips for CRF completion are described and the chapter shows how important question construction is in achieving the objectives of a CRF. The process of CRF printing is described and the different methods for binding and their importance in the production of a robust CRF. The pros and cons of Paper vs. eCRFs is described and the use of tablets and mobile phones being used for data capture is explored, Whatever the method of data capture the design features of the CFR will largely remain the same.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Br J Clin Pharmacol

- v.83(9); 2017 Sep

Electronic case report forms and electronic data capture within clinical trials and pharmacoepidemiology

David a. rorie.

1 Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, University of Dundee, Dundee, UK

Robert W. V. Flynn

Kerr grieve, alexander doney, isla mackenzie, thomas m. macdonald.

Researchers in clinical and pharmacoepidemiology fields have adopted information technology (IT) and electronic data capture, but these remain underused despite the benefits. This review discusses electronic case report forms and electronic data capture, specifically within pharmacoepidemiology and clinical research.

The review used PubMed and the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers library. Search terms used were agreed by the authors and documented. PubMed is medical and health based, whereas Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers is technology based. The review focuses on electronic case report forms and electronic data capture, but briefly considers other relevant topics; consent, ethics and security.

There were 1126 papers found using the search terms. Manual filtering and reviewing of abstracts further condensed this number to 136 relevant manuscripts. The papers were further categorized: 17 contained study data; 40 observational data; 27 anecdotal data; 47 covering methodology or design of systems; one case study; one literature review; two feasibility studies; and one cost analysis.

Electronic case report forms, electronic data capture and IT in general are viewed with enthusiasm and are seen as a cost‐effective means of improving research efficiency, educating participants and improving trial recruitment, provided concerns about how data will be protected from misuse can be addressed. Clear operational guidelines and best practises are key for healthcare providers, and researchers adopting IT, and further work is needed on improving integration of new technologies with current systems. A robust method of evaluation for technical innovation is required.

What is Already Known about this Subject

- Information technology (IT) has tangible benefits to assisting high quality research.

- Investment in IT is underfunded in healthcare and research.

What this Study Adds

- A governance support framework is necessary to assist healthcare providers and researchers to maximize the benefits of IT.

- Further work is required in improving interoperability between IT systems for research and pharmacoepidemiology.

- An unambiguous legislative framework is needed to ensure high quality research can continue successfully whilst continuing to adhere to good clinical practice, data protection and ethics.

- Generic and adaptable solutions are required to meet the software needs of researchers and healthcare providers.

Introduction

Information technology (IT) provides a fast and efficient way to collect scientific and clinical data and has become the most effective way to collaboratively share data. The benefits have underpinned the incremental introduction of electronic patient records in healthcare organizations which has been suggested as the principal reason for the increasing allocation of healthcare industry funding to IT; from 2% of total revenue, in the 1990s, to 5–7% in recent years 1 . This in turn has contributed to investment in the use of IT and electronic case report forms (eCRFs) in clinical research. Whilst these systems are designed and used differently, they share a common goal of storing, and communicating in a safe and confidential way private clinical data in a structured format 2 . Pharmacoepidemiology and clinical research have undoubtedly benefitted from IT; however, developments in these areas have continued to lag behind the healthcare sector, with investment limited due to various concerns. Reasons cited for not further using IT in research include: technical issues in setting up infrastructure, financing and maintaining the newest technology, and ethical fears 3 . Additionally, different funding streams and personnel involved in development of electronic patient records used for healthcare purposes, and those used for data capture for research, make it difficult to integrate solutions that would satisfy both aims. The objectives of both types of system are often different, which can also lead to conflicts.

Different regulatory processes govern systems used in routine healthcare and research. However, clinical research relying on IT and electronic data capture (EDC) often depends on interfacing with healthcare IT systems, which generally comprise numerous dissimilar software systems and storage formats for storing patient data. Clinical research also often operates over large geographical areas, incorporating several different healthcare providers, further compounding challenges when interfacing with diverse local systems. Although there is a drive towards IT unification in the National Health Service primary care practises and hospital trusts in the UK are under no obligation to use collaborative IT systems or storage formats, nor are they required to make these data available for research purposes. While the need to exploit healthcare data for research to cost effectively drive healthcare improvements has never been greater, it is largely for these reasons that the task of collecting, storing and amalgamating health service data is likely to become increasingly difficult in the future.

The objective of this review is to assess the advantages and disadvantages of eCRF and EDC technologies in pharmacoepidemiology and clinical research, and to explore where further research should be best directed. For the purpose of this paper the term eCRF will refer to a system used to capture clinical data for research and EDC will refer to the generic process of data capture.

A literature review was conducted to identify articles pertaining to pharmacoepidemiology (drug epidemiology) and clinical research, and their use of eCRFs and EDC. Whilst the use of IT in routine healthcare is increasingly commonplace, the emphasis of this review was on the use of EDC and eCRFs in the conduct of clinical research. Common themes relating to these topics emerged covering a broad range of issues including technical and practical matters, consent, ethics, and security. PubMed and the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE) libraries were searched using to cast a wide net over the subject area; electronic case report form, eCRF, electronic data capture, and electronic data collection. Filters were applied to search terms to condense results to relevant articles (see Appendix). The search was conducted between 2014 and 2015 with a final analysis of the literature completed in August 2016. PubMed is a clinical library while IEEE is technology based.

All returned abstracts were read and articles deemed irrelevant to eCRFs and EDC, or articles that did not involve pharmacoepidemiology or clinical research, were excluded. Unlike clinical studies, IT has no universally accepted quality scoring system for academic papers. Therefore, it was decided that any published and peer reviewed article that was returned from the IEEE or PubMed search would be included. Exceptions to this were where there was an overt conflict of interest or the journal was not available in English. Figure 1 depicts a flow diagram of the review process. The authors endeavoured to adhere fully to the PRISMA checklist 4 in structuring this review; however, the nonstandard output of technical papers made this impractical. The included papers were sorted by relevance, and categorized according to whether they contained opinion or data. Papers reporting data included anecdotal data, observational data from selected data sources, observational data in population‐based studies, prospective observational data and experimental data such as clinical trials. Papers were analysed to identify reported positive and negative aspects of the IT tools being discussed.

Flow diagram of review

A total of 1126 papers were returned from all search topics. After review and consideration, 136 manuscripts were deemed relevant to the review. Each topic was further separated into manuscript types. There were 17 papers documenting a study or clinical trial that used EDC where the system was the primary focus of the manuscript; 40 papers discussed observational studies comparing or evaluating EDC; 27 papers contained anecdotal evidence or opinion regarding EDC; 47 papers detailed EDC models or designs. There was one literature review, one cost benefit analysis, two feasibility studies, and one case study comparing the use of EDC in five studies (Table 1 ). During this review, papers were further discarded that were found to be of poor overall quality or adding little to the topic. For a list of all included publications see Table 2 .

Characteristics of journal papers

Publication review list

Research has been conducted into ways to maximize data accuracy and efficiency using IT. Trials have taken data from patient's electronic medical records (EMRs) and transferred these directly into eCRFs. The cost savings, quality improvements, and reduction of data entry errors, were significant 5 , 6 , 7 . Whilst not all required data ARE available from the patient EMR, studies have found varying results with as much as 69% of data required being found and used to prepopulate trial eCRFs 8 . Discussions around the design and theoretical modelling of EMRs, eCRFs and ECD were prevalent within the included papers 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 . The electronic systems reported vary in quality, with some being used in mock environments and others being purely theoretical. Commercial software packages are available, but are generally not cost effective and in some circumstances it is unclear who owns the data entered into them 18 , 19 , 20 . Observational studies have compared paper based systems against EDC or canvassed opinion on the use of EDC systems 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 . These papers were overwhelmingly in favour of EDC as long as security could be maintained.

Obtaining patient consent is an ethical necessity, and up until recently, has almost always required a physical signature. Varnhagen et al. 25 considered obtaining informed consent online and questioned whether it is ethical to obtain consent electronically. Recently, electronic consent has been accepted by the National Health Service as a viable alternative to a written signature 26 . This review found one trial where consent had successfully been captured online 27 . Collecting participant consent electronically is a novel, and largely unexplored, method that invites further innovation. There are ethical implications of conducting research entirely online. IT is advancing faster than ethical review panels can address and there is a need for greater ethical consideration of conducting research online and how we share data between IT systems and within organizations 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 . Government attempts to legislate – the Health Insurance and Portability Act 36 in the USA, and the Data Protection Act 37 in the UK, have had little impact on alleviating public scepticism 38 . Patient privacy is critical and despite the well‐intentioned zeal for the mass adoption of IT within healthcare, serious security concerns remain 39 , 40 . However, patients are open to technology being used to store their medical data if trust and privacy concerns can be addressed 41 .

Clinical research and pharmacoepidemiology often involve interdisciplinary research. This not only means that various researchers deal with different data sources and formats but also that they have different workflows and organizational structures. As a consequence, there are no off‐the‐shelf solutions to facilitate this. This often results in individual solutions being developed that, over time, evolve and are ultimately difficult to maintain 42 . Unfortunately, it is often much easier to change time points, interventions, and assessment tools on paper than it is to suddenly change the programming of a computerized system. The reality demands future IT systems be flexible and adaptable with more automation 43 .

Advantages and disadvantages

There are distinct advantages to EDC in research and pharmacoepidemiology. However, there are pragmatic concerns that need to be addressed. The role of clinical research and pharmacoepidemiology is to improve healthcare by generating and providing access to high quality data. Due to the limitations of paper based records this is not possible with the status quo 44 . The objectives of ECD are to reduce medical errors, improve communication between healthcare providers, collect information for educational and research purposes and to gather complete and accurate data whilst avoiding duplication.