Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Descriptive research aims to accurately and systematically describe a population, situation or phenomenon. It can answer what , where , when , and how questions , but not why questions.

A descriptive research design can use a wide variety of research methods to investigate one or more variables . Unlike in experimental research , the researcher does not control or manipulate any of the variables, but only observes and measures them.

Table of contents

When to use a descriptive research design, descriptive research methods.

Descriptive research is an appropriate choice when the research aim is to identify characteristics, frequencies, trends, and categories.

It is useful when not much is known yet about the topic or problem. Before you can research why something happens, you need to understand how, when, and where it happens.

- How has the London housing market changed over the past 20 years?

- Do customers of company X prefer product Y or product Z?

- What are the main genetic, behavioural, and morphological differences between European wildcats and domestic cats?

- What are the most popular online news sources among under-18s?

- How prevalent is disease A in population B?

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Descriptive research is usually defined as a type of quantitative research , though qualitative research can also be used for descriptive purposes. The research design should be carefully developed to ensure that the results are valid and reliable .

Survey research allows you to gather large volumes of data that can be analysed for frequencies, averages, and patterns. Common uses of surveys include:

- Describing the demographics of a country or region

- Gauging public opinion on political and social topics

- Evaluating satisfaction with a company’s products or an organisation’s services

Observations

Observations allow you to gather data on behaviours and phenomena without having to rely on the honesty and accuracy of respondents. This method is often used by psychological, social, and market researchers to understand how people act in real-life situations.

Observation of physical entities and phenomena is also an important part of research in the natural sciences. Before you can develop testable hypotheses , models, or theories, it’s necessary to observe and systematically describe the subject under investigation.

Case studies

A case study can be used to describe the characteristics of a specific subject (such as a person, group, event, or organisation). Instead of gathering a large volume of data to identify patterns across time or location, case studies gather detailed data to identify the characteristics of a narrowly defined subject.

Rather than aiming to describe generalisable facts, case studies often focus on unusual or interesting cases that challenge assumptions, add complexity, or reveal something new about a research problem .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 25 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/descriptive-research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, correlational research | guide, design & examples, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods.

Demystifying the research process: understanding a descriptive comparative research design

Affiliation.

- 1 College of Nursing, Villanova University, Villanova, PA, USA.

- PMID: 21916346

Publication types

- Comparative Study

- Pediatric Nursing

- Reproducibility of Results

- Research Design*

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Descriptive Research | Definition, Types, Methods & Examples

Descriptive Research | Definition, Types, Methods & Examples

Published on May 15, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Descriptive research aims to accurately and systematically describe a population, situation or phenomenon. It can answer what , where , when and how questions , but not why questions.

A descriptive research design can use a wide variety of research methods to investigate one or more variables . Unlike in experimental research , the researcher does not control or manipulate any of the variables, but only observes and measures them.

Table of contents

When to use a descriptive research design, descriptive research methods, other interesting articles.

Descriptive research is an appropriate choice when the research aim is to identify characteristics, frequencies, trends, and categories.

It is useful when not much is known yet about the topic or problem. Before you can research why something happens, you need to understand how, when and where it happens.

Descriptive research question examples

- How has the Amsterdam housing market changed over the past 20 years?

- Do customers of company X prefer product X or product Y?

- What are the main genetic, behavioural and morphological differences between European wildcats and domestic cats?

- What are the most popular online news sources among under-18s?

- How prevalent is disease A in population B?

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Descriptive research is usually defined as a type of quantitative research , though qualitative research can also be used for descriptive purposes. The research design should be carefully developed to ensure that the results are valid and reliable .

Survey research allows you to gather large volumes of data that can be analyzed for frequencies, averages and patterns. Common uses of surveys include:

- Describing the demographics of a country or region

- Gauging public opinion on political and social topics

- Evaluating satisfaction with a company’s products or an organization’s services

Observations

Observations allow you to gather data on behaviours and phenomena without having to rely on the honesty and accuracy of respondents. This method is often used by psychological, social and market researchers to understand how people act in real-life situations.

Observation of physical entities and phenomena is also an important part of research in the natural sciences. Before you can develop testable hypotheses , models or theories, it’s necessary to observe and systematically describe the subject under investigation.

Case studies

A case study can be used to describe the characteristics of a specific subject (such as a person, group, event or organization). Instead of gathering a large volume of data to identify patterns across time or location, case studies gather detailed data to identify the characteristics of a narrowly defined subject.

Rather than aiming to describe generalizable facts, case studies often focus on unusual or interesting cases that challenge assumptions, add complexity, or reveal something new about a research problem .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, June 22). Descriptive Research | Definition, Types, Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/descriptive-research/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is quantitative research | definition, uses & methods, correlational research | when & how to use, descriptive statistics | definitions, types, examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Health Policy Manag

- v.7(9); 2018 Sep

The Qualitative Descriptive Approach in International Comparative Studies: Using Online Qualitative Surveys

Brayan v. seixas.

1 School of Population and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Neale Smith

2 Centre for Clinical Epidemiology & Evaluation, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Craig Mitton

International comparative studies constitute a highly valuable contribution to public policy research. Analysing different policy designs offers not only a mean of knowing the phenomenon itself but also gives us insightful clues on how to improve existing practices. Although much of the work carried out in this realm relies on quantitative appraisal of the data contained in international databases or collected from institutional websites, countless topics may simply not be studied using this type of methodological design due to, for instance, the lack of reliable databases, sparse or diffuse sources of information, etc. Here then we discuss the use of the qualitative descriptive approach as a methodological tool to obtain data on how policies are structured. We propose the use of online qualitative surveys with key stakeholders from each relevant national context in order to retrieve the fundamental pieces of information on how a certain public policy is addressed there. Starting from Sandelowski’s seminal paper on qualitative descriptive studies, we conduct a theoretical reflection on the current methodological proposition. We argue that a researcher engaged in this endeavour acts like a composite-sketch artist collecting pieces of information from witnesses in order to draw a valid depiction of reality. Furthermore, we discuss the most relevant aspects involving sampling, data collection and data analysis in this context. Overall, this methodological design has a great potential for allowing researchers to expand the international analysis of public policies to topics hitherto little appraised from this perspective.

Introduction

International comparative studies may contribute enormously to public policy research. Understanding the distinct manners in which a certain issue may be tackled provides better comprehension of the problem itself as well as useful insights on the design of institutional responses. For instance, the works of Hall and Lamont, 1 Stuckler and Basu, 2 and Schrecker and Bambra 3 consistently show through cross-national comparisons how certain economic policies have profoundly impacted on population health.

However international comparisons pose demanding data collection challenges. Much of the work performed in such studies relies on existing databases kept by international agencies, third sector organizations or research institutions (eg, World Bank, OECD, WHO, UN). For studies on some topics, however, there is no reliable database from which the necessary information might be retrieved. Thus, it is vital that alternative, methodologically rigorous approaches emerge.

Here we discuss the use of online qualitative surveys as a tool to overcome the difficulties of conducting comparative studies on public policies in different national jurisdictions. The basic idea is that instead of relying on institutional websites, publicly available policy documents or well-established databases to understand how certain policies have been addressed, we could question key stakeholders (such as policy-makers, public servants or researchers involved with the topic in question) from each relevant national context in order to retrieve essential information directly from them.

Given that the diversity of responses can be totally unanticipated by researchers, it is necessary to have a tool that is open enough to allow any type of information to be captured, for which purpose qualitative methodologies are highly appropriate. However, taking into account that the main objective of this type of research is to obtain comparable information from a potentially large number of different countries, the methodology needs also to pre-structure responses to a sufficient extent to allow for viable and efficient data reduction and analysis. And for this particularity, a qualitative description approach through the use of online qualitative surveys, ie, structured questionnaires with open-ended questions, seems to be an interesting solution.

Thus, this paper aims to provide a discussion of the theoretical reasoning underlying the qualitative description approach – presenting as an adequate solution to the tensions noted above – as well as practical insights on the development of such work within the realm of international comparative studies on public policies.

Theoretical Reasoning

According to Sandelowski, 4 basic or fundamental qualitative description differs from other types of qualitative research, such as grounded theory, ethnography, phenomenology or narrative analysis, in the sense that it is — as the label suggests — essentially descriptive rather than interpretive in focus. This does not mean that a qualitative descriptive approach lacks interpretive efforts or that it intends a supposedly neutral depiction of reality. Qualitative description represents the methodological category that has the least level of inference among the qualitative methods, one that allows “ the reading of lines, as opposed to reading into, between, over or beyond the lines. ” 5 However, it should not be understood as a low-quality approach or solely as an entry-point to really deep research. “ There is nothing trivial or easy about getting the facts, and the meanings participants give to those facts, right and then conveying them in a coherent and useful manner. ” 4 Such qualitative description must be viewed as a valuable end-product in itself, and not simply as an entry-point.

We propose the use of on-line surveys as a way of operationalizing qualitative description in international comparative studies, allowing the retrieval of information on governmental/institutional efforts to develop, implement and evaluate public policies based on the reports of involved stakeholders who draw upon their own situated experience and knowledge. Within this context, we offer a reflection emerging from Kvale’s metaphor 6 on the role of a researcher. Kvale presents two ideal types: the researcher as a miner and the researcher as a traveller. For the former, the reality is out there waiting to be discovered. The job of a miner is then to find the precious stones, the gems, ie, the pieces of reality that have value in a given social setting. Thus, the miner-researcher operates under a predominantly positivist framework. On the contrary, the traveller is experiencing the reality herself. There is no separation of what a traveller has to tell us about the reality from the actual reality. Therefore, the traveller-researcher is not a collector of pieces of information, but rather she/he is the proper constructor of the pieces. This type of researcher marches mainly under a socio-constructivist paradigm.

Kvale’s metaphor is indeed incredibly insightful to reflect on the role of the qualitative researcher in general, which should not be understood as either miner or traveller, but as an enterprise with a predominance of one or the other role. Yet for qualitative descriptive studies particularly, we suggest that another metaphorical representation can be even more powerful. Here we propose that the role of a researcher involved in qualitative descriptive efforts is that of a composite sketch artist . The underlying idea is that this artist has the role of depicting a ‘reality’ based on the reports of the witnesses. In other words, the artist has the duty of drawing a picture that is in accordance to the memories of the witnesses, rather than substituting his/her own speculation in its stead. The artist inevitably has her/his own images in mind, but the aim is to capture the understanding of the other—a picture that the witnesses would agree represents the reality they experienced. Contextualizing this for the field of policy research, the role of the researcher conducting qualitative descriptive study is to retrieve information from stakeholders about their own experiences with the institutions in order to reconstruct the actual governmental designs of public policies or organizational management systems. Thus, the method employed has to faithfully draw the picture upon which most of the interviewees from a given setting will agree.

This metaphor leads us to reflect on the concepts of descriptive and interpretive validity, as elaborated by Maxwell. 7 For Maxwell, descriptive validity refers to the accurate, ‘correct’ or faithful use of the factual aspects of data. It is predominantly related to the elements “pertaining to physical and behavioral events that are, in principle, observable.” 7 For example, policy content and the means by which policy is enacted within given political jurisdictions. Thus, the large majority of the work conducted in qualitative descriptions are almost exclusively circumscribed to this level of interpretation and validity. In other words, descriptive validity deals with how the composite-sketch artist treats the information provided by the witness. It does not mean that the researcher would actually work as a copier or a mere reproducer – impossible as he/she is not within the head of the observer and does not share the experience in question. The important thing to note here is that qualitative description is not an inference-free approach, but rather the methodological work of least inference among categories of qualitative work. In the context of international comparative studies, the researcher has to ‘keep close to the surface’ of the information provided by the stakeholders in order to appropriately describe the local systems of management or public policies.

Albeit the fundamental concern of qualitative descriptive studies is to provide a sort of report of events, institutional structures, and commonly observable behaviors, it is also important that researchers account for the meaning of these things for the people studied. It does not signify that qualitative description will dive deeply into the web of meanings in which subjects are constantly moving, but there has to be at least a conscious movement of acknowledging this phenomenon in order to obtain a valid drawing of the reality. This is what Maxwell calls interpretive validity. 7 Thinking in terms of our proposed metaphor, the composite-sketch artist needs to take into consideration what pieces of information provided by witnesses actually can mean to them. So, the witness may say that the crime perpetrator has big green eyes, but although this constitutes factual information, this is not enough in order to draw the actual eyes that would be recognized by the witness. The understood meaning of ‘big’ emerges on paper through the efforts of the sketch artist. It is necessary to take account some level of interpretive data, though just as long as it indeed helps the ‘reconstruction of reality.’

The next section will focus on the more practical details of developing an online survey as a qualitative descriptive endeavour for international comparative studies.

Methodological Issues

As Sandelowski 5 points out, qualitative description is a distributed residual category and, as such, it makes visible the “ porous lines between qualitative and quantitative description (…) and between the erosion and re-invention of method ” (p. 82). In other words, this category of inquiry may incorporate elements from quantitative and qualitative methodologies and, thus, serve as an innovative research tool. In the particular case of obtaining information from different national contexts, a qualitative description approach allows collection of data that will be analysed not only from the perspective of traditionally qualitative methodologies, but also from a more quantitative lens, making possible a quasi-statistical analysis of content, providing an overall summary of the findings.

For this type of research, we propose a combination of purposeful sampling strategies – here we rely on the classification system developed by Patton. 8 At the initial level of sampling, ie, the country-level, it is important to ensure comparability among the selected nations. This is extremely important for the validity of the quantitizing stage of data analysis, which should report a numerical summary of the data and observed patterns. For this level of sampling, hence, it is important to combine two strategies: homogeneity sampling and criterion sampling. For instance, we could select countries by the number of inhabitants or we could decide to include countries only above or below a given value of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

Subsequently, sampling may focus on using strategies to guarantee that there is meaningful variation within the sample and that politically important cases are not missing. For example, it may be appropriate to include cases with distinct institutional models, such as countries with parliamentary and presidential systems, or countries with centralized and decentralized responsibilities for a given public service.

Once the countries to be included in an international comparative study are determined, researchers need to identify individual informants. While an explicit sampling frame (eg, a directory of government department heads) may sometimes be available, strategies such as snowball sampling and convenience sampling may be required in order to make the study viable. Figure depicts this whole process of sampling within the context of using a survey as a qualitative descriptive tool to study public policies across countries.

Purposeful Sampling Strategies for Qualitative Description in International Comparative Studies.

Data Collection

As aforementioned, the main objective of data collection within this context is to obtain information about the institutional design of public policies. For this, researchers will rely on the reports of participants to reconstruct the ‘reality’ of each national scenario.

It is precisely at this point that the survey is the basic tool for collecting data. Respondents located in each national context would be invited to participate in an online qualitative survey. Researchers will have to circulate a structured survey instrument that allows participants to express their ideas on their own terms, but, at the same time, within a format that facilitates or guides the process of data analysis. Considering that qualitative description aims to record the fact, or in other words, to describe the things upon which most people would readily agree, the research team needs to develop an effective survey to engage participants in the description of the essential policy elements, without narrowing their possibilities of responses.

Data Analysis

For Sandelowski, 4 the analytic strategy of choice in qualitative description is Qualitative Content Analysis . This is a dynamic analytical tool intended to depict the informational content of the data. 9 Although similar to quantitative content analysis, this is different because the codes are commonly generated from the data (ie, derived inductively) in the course of the study. In addition, in qualitative content analysis, the quantitizing phase (the stage when the coded data elements can be numerically organized) allows the researcher to go beyond the mere summarization of the manifest data (the information readily retrievable from the raw dataset). Inferring associations, depicting tendencies and making predictions provide insight into the latent content of data obtained (ie, the type of information that requires a deeper analytic effort to be revealed).

In the context of international comparative studies, other data analysis strategies may also prove fruitful. For instance, the gaps between qualitative and quantitative analyses can be bridged using Ragin’s Qualitative Comparative Analysis. 10 This may be a valuable tool to investigate the generalizability of findings as well as the causal complexity of the variables encountered in the coded data.

By conducting qualitative descriptive studies with decision-makers, public servants and/or the local research community, it is possible for international comparative studies to use participants’ contextually-situated knowledge to depict the realities of different public policy contexts. The metaphor of the composite sketch artist can be a powerful device to guide methodological reflections, such as the notions of descriptive validity (the depiction of events as perceived by observers in their apparent sequence) and interpretive validity (the appropriate elicitation of the meanings attributed by the agents to those events). It illuminates the researcher’s role in presenting a picture of the topic investigated that most observers would likely agree with.

We argue that qualitative descriptive efforts are neither thick nor thin descriptions, in the sense used by Clifford Geertz. 11 By his account, a thick description is an instrument that unveils the web of significance allowing the researcher to differentiate among ‘the conspiratorial winking,’ ‘the involuntary twitch,’ ‘the parodic-fake winking,’ and ‘the rehearsing winking,’ whereas the thin description is the mere report of people rapidly contracting the eyelids. A qualitative description is something else. A fundamental or basic qualitative descriptive endeavour would seek to describe, for instance, who are the ones supposedly winking, how many they are, how many times they wink, which other gestures are being done, where these people are situated, who else is present, etc. Basic or fundamental qualitative descriptive studies thus cannot be properly understood within this Geertzian dualistic epistemological framework. Its virtue as a qualitative category of inquiry that stand per se (despite its residual nature) is only acknowledged by inscribing it within other framings. A qualitative description could be understood as a comprehensive description, one that seeks to provide a detailed description of the findings more likely to generate consensus among observers.

In the voluminous literature on qualitative research methods, there is no comprehensive study with a systematic reflection about the use of online qualitative surveys in international comparative studies on public policies. Therefore, our current endeavour may provide a valuable contribution to the research community as a potential approach available to researchers for investigating comparative topics in a methodologically rigorous manner.

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BVS developed the paper’s central reasoning and crafted the first draft; NS provided extensive support in reviewing the text and offering fundamental contributions; CM supervised the whole work and provided meaningful contributions up to its final version.

Authors’ affiliations

1 School of Population and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada. 2 Centre for Clinical Epidemiology & Evaluation, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Citation: Seixas BV, Smith N, Mitton C. The qualitative descriptive approach in international comparative studies: using online qualitative surveys. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(9):778–781. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2017.142

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Descriptive Research Design

Definition:

Descriptive research design is a type of research methodology that aims to describe or document the characteristics, behaviors, attitudes, opinions, or perceptions of a group or population being studied.

Descriptive research design does not attempt to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables or make predictions about future outcomes. Instead, it focuses on providing a detailed and accurate representation of the data collected, which can be useful for generating hypotheses, exploring trends, and identifying patterns in the data.

Types of Descriptive Research Design

Types of Descriptive Research Design are as follows:

Cross-sectional Study

This involves collecting data at a single point in time from a sample or population to describe their characteristics or behaviors. For example, a researcher may conduct a cross-sectional study to investigate the prevalence of certain health conditions among a population, or to describe the attitudes and beliefs of a particular group.

Longitudinal Study

This involves collecting data over an extended period of time, often through repeated observations or surveys of the same group or population. Longitudinal studies can be used to track changes in attitudes, behaviors, or outcomes over time, or to investigate the effects of interventions or treatments.

This involves an in-depth examination of a single individual, group, or situation to gain a detailed understanding of its characteristics or dynamics. Case studies are often used in psychology, sociology, and business to explore complex phenomena or to generate hypotheses for further research.

Survey Research

This involves collecting data from a sample or population through standardized questionnaires or interviews. Surveys can be used to describe attitudes, opinions, behaviors, or demographic characteristics of a group, and can be conducted in person, by phone, or online.

Observational Research

This involves observing and documenting the behavior or interactions of individuals or groups in a natural or controlled setting. Observational studies can be used to describe social, cultural, or environmental phenomena, or to investigate the effects of interventions or treatments.

Correlational Research

This involves examining the relationships between two or more variables to describe their patterns or associations. Correlational studies can be used to identify potential causal relationships or to explore the strength and direction of relationships between variables.

Data Analysis Methods

Descriptive research design data analysis methods depend on the type of data collected and the research question being addressed. Here are some common methods of data analysis for descriptive research:

Descriptive Statistics

This method involves analyzing data to summarize and describe the key features of a sample or population. Descriptive statistics can include measures of central tendency (e.g., mean, median, mode) and measures of variability (e.g., range, standard deviation).

Cross-tabulation

This method involves analyzing data by creating a table that shows the frequency of two or more variables together. Cross-tabulation can help identify patterns or relationships between variables.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing qualitative data (e.g., text, images, audio) to identify themes, patterns, or trends. Content analysis can be used to describe the characteristics of a sample or population, or to identify factors that influence attitudes or behaviors.

Qualitative Coding

This method involves analyzing qualitative data by assigning codes to segments of data based on their meaning or content. Qualitative coding can be used to identify common themes, patterns, or categories within the data.

Visualization

This method involves creating graphs or charts to represent data visually. Visualization can help identify patterns or relationships between variables and make it easier to communicate findings to others.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing data across different groups or time periods to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can help describe changes in attitudes or behaviors over time or differences between subgroups within a population.

Applications of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has numerous applications in various fields. Some of the common applications of descriptive research design are:

- Market research: Descriptive research design is widely used in market research to understand consumer preferences, behavior, and attitudes. This helps companies to develop new products and services, improve marketing strategies, and increase customer satisfaction.

- Health research: Descriptive research design is used in health research to describe the prevalence and distribution of a disease or health condition in a population. This helps healthcare providers to develop prevention and treatment strategies.

- Educational research: Descriptive research design is used in educational research to describe the performance of students, schools, or educational programs. This helps educators to improve teaching methods and develop effective educational programs.

- Social science research: Descriptive research design is used in social science research to describe social phenomena such as cultural norms, values, and beliefs. This helps researchers to understand social behavior and develop effective policies.

- Public opinion research: Descriptive research design is used in public opinion research to understand the opinions and attitudes of the general public on various issues. This helps policymakers to develop effective policies that are aligned with public opinion.

- Environmental research: Descriptive research design is used in environmental research to describe the environmental conditions of a particular region or ecosystem. This helps policymakers and environmentalists to develop effective conservation and preservation strategies.

Descriptive Research Design Examples

Here are some real-time examples of descriptive research designs:

- A restaurant chain wants to understand the demographics and attitudes of its customers. They conduct a survey asking customers about their age, gender, income, frequency of visits, favorite menu items, and overall satisfaction. The survey data is analyzed using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulation to describe the characteristics of their customer base.

- A medical researcher wants to describe the prevalence and risk factors of a particular disease in a population. They conduct a cross-sectional study in which they collect data from a sample of individuals using a standardized questionnaire. The data is analyzed using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulation to identify patterns in the prevalence and risk factors of the disease.

- An education researcher wants to describe the learning outcomes of students in a particular school district. They collect test scores from a representative sample of students in the district and use descriptive statistics to calculate the mean, median, and standard deviation of the scores. They also create visualizations such as histograms and box plots to show the distribution of scores.

- A marketing team wants to understand the attitudes and behaviors of consumers towards a new product. They conduct a series of focus groups and use qualitative coding to identify common themes and patterns in the data. They also create visualizations such as word clouds to show the most frequently mentioned topics.

- An environmental scientist wants to describe the biodiversity of a particular ecosystem. They conduct an observational study in which they collect data on the species and abundance of plants and animals in the ecosystem. The data is analyzed using descriptive statistics to describe the diversity and richness of the ecosystem.

How to Conduct Descriptive Research Design

To conduct a descriptive research design, you can follow these general steps:

- Define your research question: Clearly define the research question or problem that you want to address. Your research question should be specific and focused to guide your data collection and analysis.

- Choose your research method: Select the most appropriate research method for your research question. As discussed earlier, common research methods for descriptive research include surveys, case studies, observational studies, cross-sectional studies, and longitudinal studies.

- Design your study: Plan the details of your study, including the sampling strategy, data collection methods, and data analysis plan. Determine the sample size and sampling method, decide on the data collection tools (such as questionnaires, interviews, or observations), and outline your data analysis plan.

- Collect data: Collect data from your sample or population using the data collection tools you have chosen. Ensure that you follow ethical guidelines for research and obtain informed consent from participants.

- Analyze data: Use appropriate statistical or qualitative analysis methods to analyze your data. As discussed earlier, common data analysis methods for descriptive research include descriptive statistics, cross-tabulation, content analysis, qualitative coding, visualization, and comparative analysis.

- I nterpret results: Interpret your findings in light of your research question and objectives. Identify patterns, trends, and relationships in the data, and describe the characteristics of your sample or population.

- Draw conclusions and report results: Draw conclusions based on your analysis and interpretation of the data. Report your results in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate tables, graphs, or figures to present your findings. Ensure that your report follows accepted research standards and guidelines.

When to Use Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design is used in situations where the researcher wants to describe a population or phenomenon in detail. It is used to gather information about the current status or condition of a group or phenomenon without making any causal inferences. Descriptive research design is useful in the following situations:

- Exploratory research: Descriptive research design is often used in exploratory research to gain an initial understanding of a phenomenon or population.

- Identifying trends: Descriptive research design can be used to identify trends or patterns in a population, such as changes in consumer behavior or attitudes over time.

- Market research: Descriptive research design is commonly used in market research to understand consumer preferences, behavior, and attitudes.

- Health research: Descriptive research design is useful in health research to describe the prevalence and distribution of a disease or health condition in a population.

- Social science research: Descriptive research design is used in social science research to describe social phenomena such as cultural norms, values, and beliefs.

- Educational research: Descriptive research design is used in educational research to describe the performance of students, schools, or educational programs.

Purpose of Descriptive Research Design

The main purpose of descriptive research design is to describe and measure the characteristics of a population or phenomenon in a systematic and objective manner. It involves collecting data that describe the current status or condition of the population or phenomenon of interest, without manipulating or altering any variables.

The purpose of descriptive research design can be summarized as follows:

- To provide an accurate description of a population or phenomenon: Descriptive research design aims to provide a comprehensive and accurate description of a population or phenomenon of interest. This can help researchers to develop a better understanding of the characteristics of the population or phenomenon.

- To identify trends and patterns: Descriptive research design can help researchers to identify trends and patterns in the data, such as changes in behavior or attitudes over time. This can be useful for making predictions and developing strategies.

- To generate hypotheses: Descriptive research design can be used to generate hypotheses or research questions that can be tested in future studies. For example, if a descriptive study finds a correlation between two variables, this could lead to the development of a hypothesis about the causal relationship between the variables.

- To establish a baseline: Descriptive research design can establish a baseline or starting point for future research. This can be useful for comparing data from different time periods or populations.

Characteristics of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has several key characteristics that distinguish it from other research designs. Some of the main characteristics of descriptive research design are:

- Objective : Descriptive research design is objective in nature, which means that it focuses on collecting factual and accurate data without any personal bias. The researcher aims to report the data objectively without any personal interpretation.

- Non-experimental: Descriptive research design is non-experimental, which means that the researcher does not manipulate any variables. The researcher simply observes and records the behavior or characteristics of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Quantitative : Descriptive research design is quantitative in nature, which means that it involves collecting numerical data that can be analyzed using statistical techniques. This helps to provide a more precise and accurate description of the population or phenomenon.

- Cross-sectional: Descriptive research design is often cross-sectional, which means that the data is collected at a single point in time. This can be useful for understanding the current state of the population or phenomenon, but it may not provide information about changes over time.

- Large sample size: Descriptive research design typically involves a large sample size, which helps to ensure that the data is representative of the population of interest. A large sample size also helps to increase the reliability and validity of the data.

- Systematic and structured: Descriptive research design involves a systematic and structured approach to data collection, which helps to ensure that the data is accurate and reliable. This involves using standardized procedures for data collection, such as surveys, questionnaires, or observation checklists.

Advantages of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has several advantages that make it a popular choice for researchers. Some of the main advantages of descriptive research design are:

- Provides an accurate description: Descriptive research design is focused on accurately describing the characteristics of a population or phenomenon. This can help researchers to develop a better understanding of the subject of interest.

- Easy to conduct: Descriptive research design is relatively easy to conduct and requires minimal resources compared to other research designs. It can be conducted quickly and efficiently, and data can be collected through surveys, questionnaires, or observations.

- Useful for generating hypotheses: Descriptive research design can be used to generate hypotheses or research questions that can be tested in future studies. For example, if a descriptive study finds a correlation between two variables, this could lead to the development of a hypothesis about the causal relationship between the variables.

- Large sample size : Descriptive research design typically involves a large sample size, which helps to ensure that the data is representative of the population of interest. A large sample size also helps to increase the reliability and validity of the data.

- Can be used to monitor changes : Descriptive research design can be used to monitor changes over time in a population or phenomenon. This can be useful for identifying trends and patterns, and for making predictions about future behavior or attitudes.

- Can be used in a variety of fields : Descriptive research design can be used in a variety of fields, including social sciences, healthcare, business, and education.

Limitation of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design also has some limitations that researchers should consider before using this design. Some of the main limitations of descriptive research design are:

- Cannot establish cause and effect: Descriptive research design cannot establish cause and effect relationships between variables. It only provides a description of the characteristics of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Limited generalizability: The results of a descriptive study may not be generalizable to other populations or situations. This is because descriptive research design often involves a specific sample or situation, which may not be representative of the broader population.

- Potential for bias: Descriptive research design can be subject to bias, particularly if the researcher is not objective in their data collection or interpretation. This can lead to inaccurate or incomplete descriptions of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Limited depth: Descriptive research design may provide a superficial description of the population or phenomenon of interest. It does not delve into the underlying causes or mechanisms behind the observed behavior or characteristics.

- Limited utility for theory development: Descriptive research design may not be useful for developing theories about the relationship between variables. It only provides a description of the variables themselves.

- Relies on self-report data: Descriptive research design often relies on self-report data, such as surveys or questionnaires. This type of data may be subject to biases, such as social desirability bias or recall bias.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

- Descriptive Research Designs: Types, Examples & Methods

One of the components of research is getting enough information about the research problem—the what, how, when and where answers, which is why descriptive research is an important type of research. It is very useful when conducting research whose aim is to identify characteristics, frequencies, trends, correlations, and categories.

This research method takes a problem with little to no relevant information and gives it a befitting description using qualitative and quantitative research method s. Descriptive research aims to accurately describe a research problem.

In the subsequent sections, we will be explaining what descriptive research means, its types, examples, and data collection methods.

What is Descriptive Research?

Descriptive research is a type of research that describes a population, situation, or phenomenon that is being studied. It focuses on answering the how, what, when, and where questions If a research problem, rather than the why.

This is mainly because it is important to have a proper understanding of what a research problem is about before investigating why it exists in the first place.

For example, an investor considering an investment in the ever-changing Amsterdam housing market needs to understand what the current state of the market is, how it changes (increasing or decreasing), and when it changes (time of the year) before asking for the why. This is where descriptive research comes in.

What Are The Types of Descriptive Research?

Descriptive research is classified into different types according to the kind of approach that is used in conducting descriptive research. The different types of descriptive research are highlighted below:

- Descriptive-survey

Descriptive survey research uses surveys to gather data about varying subjects. This data aims to know the extent to which different conditions can be obtained among these subjects.

For example, a researcher wants to determine the qualification of employed professionals in Maryland. He uses a survey as his research instrument , and each item on the survey related to qualifications is subjected to a Yes/No answer.

This way, the researcher can describe the qualifications possessed by the employed demographics of this community.

- Descriptive-normative survey

This is an extension of the descriptive survey, with the addition being the normative element. In the descriptive-normative survey, the results of the study should be compared with the norm.

For example, an organization that wishes to test the skills of its employees by a team may have them take a skills test. The skills tests are the evaluation tool in this case, and the result of this test is compared with the norm of each role.

If the score of the team is one standard deviation above the mean, it is very satisfactory, if within the mean, satisfactory, and one standard deviation below the mean is unsatisfactory.

- Descriptive-status

This is a quantitative description technique that seeks to answer questions about real-life situations. For example, a researcher researching the income of the employees in a company, and the relationship with their performance.

A survey will be carried out to gather enough data about the income of the employees, then their performance will be evaluated and compared to their income. This will help determine whether a higher income means better performance and low income means lower performance or vice versa.

- Descriptive-analysis

The descriptive-analysis method of research describes a subject by further analyzing it, which in this case involves dividing it into 2 parts. For example, the HR personnel of a company that wishes to analyze the job role of each employee of the company may divide the employees into the people that work at the Headquarters in the US and those that work from Oslo, Norway office.

A questionnaire is devised to analyze the job role of employees with similar salaries and who work in similar positions.

- Descriptive classification

This method is employed in biological sciences for the classification of plants and animals. A researcher who wishes to classify the sea animals into different species will collect samples from various search stations, then classify them accordingly.

- Descriptive-comparative

In descriptive-comparative research, the researcher considers 2 variables that are not manipulated, and establish a formal procedure to conclude that one is better than the other. For example, an examination body wants to determine the better method of conducting tests between paper-based and computer-based tests.

A random sample of potential participants of the test may be asked to use the 2 different methods, and factors like failure rates, time factors, and others will be evaluated to arrive at the best method.

- Correlative Survey

Correlative surveys are used to determine whether the relationship between 2 variables is positive, negative, or neutral. That is, if 2 variables say X and Y are directly proportional, inversely proportional or are not related to each other.

Examples of Descriptive Research

There are different examples of descriptive research, that may be highlighted from its types, uses, and applications. However, we will be restricting ourselves to only 3 distinct examples in this article.

- Comparing Student Performance:

An academic institution may wish 2 compare the performance of its junior high school students in English language and Mathematics. This may be used to classify students based on 2 major groups, with one group going ahead to study while courses, while the other study courses in the Arts & Humanities field.

Students who are more proficient in mathematics will be encouraged to go into STEM and vice versa. Institutions may also use this data to identify students’ weak points and work on ways to assist them.

- Scientific Classification

During the major scientific classification of plants, animals, and periodic table elements, the characteristics and components of each subject are evaluated and used to determine how they are classified.

For example, living things may be classified into kingdom Plantae or kingdom animal is depending on their nature. Further classification may group animals into mammals, pieces, vertebrae, invertebrae, etc.

All these classifications are made a result of descriptive research which describes what they are.

- Human Behavior

When studying human behaviour based on a factor or event, the researcher observes the characteristics, behaviour, and reaction, then use it to conclude. A company willing to sell to its target market needs to first study the behaviour of the market.

This may be done by observing how its target reacts to a competitor’s product, then use it to determine their behaviour.

What are the Characteristics of Descriptive Research?

The characteristics of descriptive research can be highlighted from its definition, applications, data collection methods, and examples. Some characteristics of descriptive research are:

- Quantitativeness

Descriptive research uses a quantitative research method by collecting quantifiable information to be used for statistical analysis of the population sample. This is very common when dealing with research in the physical sciences.

- Qualitativeness

It can also be carried out using the qualitative research method, to properly describe the research problem. This is because descriptive research is more explanatory than exploratory or experimental.

- Uncontrolled variables

In descriptive research, researchers cannot control the variables like they do in experimental research.

- The basis for further research

The results of descriptive research can be further analyzed and used in other research methods. It can also inform the next line of research, including the research method that should be used.

This is because it provides basic information about the research problem, which may give birth to other questions like why a particular thing is the way it is.

Why Use Descriptive Research Design?

Descriptive research can be used to investigate the background of a research problem and get the required information needed to carry out further research. It is used in multiple ways by different organizations, and especially when getting the required information about their target audience.

- Define subject characteristics :

It is used to determine the characteristics of the subjects, including their traits, behaviour, opinion, etc. This information may be gathered with the use of surveys, which are shared with the respondents who in this case, are the research subjects.

For example, a survey evaluating the number of hours millennials in a community spends on the internet weekly, will help a service provider make informed business decisions regarding the market potential of the community.

- Measure Data Trends

It helps to measure the changes in data over some time through statistical methods. Consider the case of individuals who want to invest in stock markets, so they evaluate the changes in prices of the available stocks to make a decision investment decision.

Brokerage companies are however the ones who carry out the descriptive research process, while individuals can view the data trends and make decisions.

Descriptive research is also used to compare how different demographics respond to certain variables. For example, an organization may study how people with different income levels react to the launch of a new Apple phone.

This kind of research may take a survey that will help determine which group of individuals are purchasing the new Apple phone. Do the low-income earners also purchase the phone, or only the high-income earners do?

Further research using another technique will explain why low-income earners are purchasing the phone even though they can barely afford it. This will help inform strategies that will lure other low-income earners and increase company sales.

- Validate existing conditions

When you are not sure about the validity of an existing condition, you can use descriptive research to ascertain the underlying patterns of the research object. This is because descriptive research methods make an in-depth analysis of each variable before making conclusions.

- Conducted Overtime

Descriptive research is conducted over some time to ascertain the changes observed at each point in time. The higher the number of times it is conducted, the more authentic the conclusion will be.

What are the Disadvantages of Descriptive Research?

- Response and Non-response Bias

Respondents may either decide not to respond to questions or give incorrect responses if they feel the questions are too confidential. When researchers use observational methods, respondents may also decide to behave in a particular manner because they feel they are being watched.

- The researcher may decide to influence the result of the research due to personal opinion or bias towards a particular subject. For example, a stockbroker who also has a business of his own may try to lure investors into investing in his own company by manipulating results.

- A case-study or sample taken from a large population is not representative of the whole population.

- Limited scope:The scope of descriptive research is limited to the what of research, with no information on why thereby limiting the scope of the research.

What are the Data Collection Methods in Descriptive Research?

There are 3 main data collection methods in descriptive research, namely; observational method, case study method, and survey research.

1. Observational Method

The observational method allows researchers to collect data based on their view of the behaviour and characteristics of the respondent, with the respondents themselves not directly having an input. It is often used in market research, psychology, and some other social science research to understand human behaviour.

It is also an important aspect of physical scientific research, with it being one of the most effective methods of conducting descriptive research . This process can be said to be either quantitative or qualitative.

Quantitative observation involved the objective collection of numerical data , whose results can be analyzed using numerical and statistical methods.

Qualitative observation, on the other hand, involves the monitoring of characteristics and not the measurement of numbers. The researcher makes his observation from a distance, records it, and is used to inform conclusions.

2. Case Study Method

A case study is a sample group (an individual, a group of people, organizations, events, etc.) whose characteristics are used to describe the characteristics of a larger group in which the case study is a subgroup. The information gathered from investigating a case study may be generalized to serve the larger group.

This generalization, may, however, be risky because case studies are not sufficient to make accurate predictions about larger groups. Case studies are a poor case of generalization.

3. Survey Research

This is a very popular data collection method in research designs. In survey research, researchers create a survey or questionnaire and distribute it to respondents who give answers.

Generally, it is used to obtain quick information directly from the primary source and also conducting rigorous quantitative and qualitative research. In some cases, survey research uses a blend of both qualitative and quantitative strategies.

Survey research can be carried out both online and offline using the following methods

- Online Surveys: This is a cheap method of carrying out surveys and getting enough responses. It can be carried out using Formplus, an online survey builder. Formplus has amazing tools and features that will help increase response rates.

- Offline Surveys: This includes paper forms, mobile offline forms , and SMS-based forms.

What Are The Differences Between Descriptive and Correlational Research?

Before going into the differences between descriptive and correlation research, we need to have a proper understanding of what correlation research is about. Therefore, we will be giving a summary of the correlation research below.

Correlational research is a type of descriptive research, which is used to measure the relationship between 2 variables, with the researcher having no control over them. It aims to find whether there is; positive correlation (both variables change in the same direction), negative correlation (the variables change in the opposite direction), or zero correlation (there is no relationship between the variables).

Correlational research may be used in 2 situations;

(i) when trying to find out if there is a relationship between two variables, and

(ii) when a causal relationship is suspected between two variables, but it is impractical or unethical to conduct experimental research that manipulates one of the variables.

Below are some of the differences between correlational and descriptive research:

- Definitions :

Descriptive research aims is a type of research that provides an in-depth understanding of the study population, while correlational research is the type of research that measures the relationship between 2 variables.

- Characteristics :

Descriptive research provides descriptive data explaining what the research subject is about, while correlation research explores the relationship between data and not their description.

- Predictions :

Predictions cannot be made in descriptive research while correlation research accommodates the possibility of making predictions.

Descriptive Research vs. Causal Research

Descriptive research and causal research are both research methodologies, however, one focuses on a subject’s behaviors while the latter focuses on a relationship’s cause-and-effect. To buttress the above point, descriptive research aims to describe and document the characteristics, behaviors, or phenomena of a particular or specific population or situation.

It focuses on providing an accurate and detailed account of an already existing state of affairs between variables. Descriptive research answers the questions of “what,” “where,” “when,” and “how” without attempting to establish any causal relationships or explain any underlying factors that might have caused the behavior.

Causal research, on the other hand, seeks to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. It aims to point out the factors that influence or cause a particular result or behavior. Causal research involves manipulating variables, controlling conditions or a subgroup, and observing the resulting effects. The primary objective of causal research is to establish a cause-effect relationship and provide insights into why certain phenomena happen the way they do.

Descriptive Research vs. Analytical Research

Descriptive research provides a detailed and comprehensive account of a specific situation or phenomenon. It focuses on describing and summarizing data without making inferences or attempting to explain underlying factors or the cause of the factor.

It is primarily concerned with providing an accurate and objective representation of the subject of research. While analytical research goes beyond the description of the phenomena and seeks to analyze and interpret data to discover if there are patterns, relationships, or any underlying factors.

It examines the data critically, applies statistical techniques or other analytical methods, and draws conclusions based on the discovery. Analytical research also aims to explore the relationships between variables and understand the underlying mechanisms or processes involved.

Descriptive Research vs. Exploratory Research

Descriptive research is a research method that focuses on providing a detailed and accurate account of a specific situation, group, or phenomenon. This type of research describes the characteristics, behaviors, or relationships within the given context without looking for an underlying cause.

Descriptive research typically involves collecting and analyzing quantitative or qualitative data to generate descriptive statistics or narratives. Exploratory research differs from descriptive research because it aims to explore and gain firsthand insights or knowledge into a relatively unexplored or poorly understood topic.

It focuses on generating ideas, hypotheses, or theories rather than providing definitive answers. Exploratory research is often conducted at the early stages of a research project to gather preliminary information and identify key variables or factors for further investigation. It involves open-ended interviews, observations, or small-scale surveys to gather qualitative data.

Read More – Exploratory Research: What are its Method & Examples?

Descriptive Research vs. Experimental Research

Descriptive research aims to describe and document the characteristics, behaviors, or phenomena of a particular population or situation. It focuses on providing an accurate and detailed account of the existing state of affairs.

Descriptive research typically involves collecting data through surveys, observations, or existing records and analyzing the data to generate descriptive statistics or narratives. It does not involve manipulating variables or establishing cause-and-effect relationships.

Experimental research, on the other hand, involves manipulating variables and controlling conditions to investigate cause-and-effect relationships. It aims to establish causal relationships by introducing an intervention or treatment and observing the resulting effects.

Experimental research typically involves randomly assigning participants to different groups, such as control and experimental groups, and measuring the outcomes. It allows researchers to control for confounding variables and draw causal conclusions.

Related – Experimental vs Non-Experimental Research: 15 Key Differences

Descriptive Research vs. Explanatory Research

Descriptive research focuses on providing a detailed and accurate account of a specific situation, group, or phenomenon. It aims to describe the characteristics, behaviors, or relationships within the given context.

Descriptive research is primarily concerned with providing an objective representation of the subject of study without explaining underlying causes or mechanisms. Explanatory research seeks to explain the relationships between variables and uncover the underlying causes or mechanisms.

It goes beyond description and aims to understand the reasons or factors that influence a particular outcome or behavior. Explanatory research involves analyzing data, conducting statistical analyses, and developing theories or models to explain the observed relationships.

Descriptive Research vs. Inferential Research

Descriptive research focuses on describing and summarizing data without making inferences or generalizations beyond the specific sample or population being studied. It aims to provide an accurate and objective representation of the subject of study.

Descriptive research typically involves analyzing data to generate descriptive statistics, such as means, frequencies, or percentages, to describe the characteristics or behaviors observed.

Inferential research, however, involves making inferences or generalizations about a larger population based on a smaller sample.

It aims to draw conclusions about the population characteristics or relationships by analyzing the sample data. Inferential research uses statistical techniques to estimate population parameters, test hypotheses, and determine the level of confidence or significance in the findings.

Related – Inferential Statistics: Definition, Types + Examples

Conclusion

The uniqueness of descriptive research partly lies in its ability to explore both quantitative and qualitative research methods. Therefore, when conducting descriptive research, researchers have the opportunity to use a wide variety of techniques that aids the research process.

Descriptive research explores research problems in-depth, beyond the surface level thereby giving a detailed description of the research subject. That way, it can aid further research in the field, including other research methods .

It is also very useful in solving real-life problems in various fields of social science, physical science, and education.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- descriptive research

- descriptive research method

- example of descriptive research

- types of descriptive research

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Type I vs Type II Errors: Causes, Examples & Prevention

This article will discuss the two different types of errors in hypothesis testing and how you can prevent them from occurring in your research

Acceptance Sampling: Meaning, Examples, When to Use

In this post, we will discuss extensively what acceptance sampling is and when it is applied.

Extrapolation in Statistical Research: Definition, Examples, Types, Applications

In this article we’ll look at the different types and characteristics of extrapolation, plus how it contrasts to interpolation.

Cross-Sectional Studies: Types, Pros, Cons & Uses

In this article, we’ll look at what cross-sectional studies are, how it applies to your research and how to use Formplus to collect...

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Research Design in Business and Management pp 85–96 Cite as

Comparing Types of Research Designs

- Stefan Hunziker 3 &

- Michael Blankenagel 3

- First Online: 10 November 2021

3090 Accesses

Every researcher chooses the research design that is best suited to generate the envisioned conclusions they like to draw. There are several types of research designs. Each is especially well suited to generate a specific type of conclusion. Commonly used research designs in business and management are design science, action research, single case, multiple case, cross-sectional, longitudinal, experimental and literature review research. The specific characteristics depicting these research design’s idiosyncrasies, differences, and fields of application of these research designs are gathered in a synopsis. Also, we pose questions that guide researchers to the research design, matching their objectives and personal preferences. This chapter also addresses the popular terms “triangulation” and “mixed methods” and puts them into the context of research design.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Asenahabin, B. M. (2019). Basics of research design: A guide to selecting appropriate research design. International Journal of Contemporary Applied Researches, 6 (5), 76–89.

Google Scholar

Burke-Johnson, R., Onwueegbuzie, A., & Turner, L. (2007). Towards a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1 (2), 112–133.

Article Google Scholar

Creswell, J. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches . SAGE.

Dresch, A., Lacerda, D., & Antunes, J. (2014). Design science research: A method for science and technology advancement . Retrieved June 10, 2021, from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/bf2a9807a0d9be8c5c11684786ae3129f3e8003e .

Gratton, C., & Jones, I. (2010). Research methods for sports studies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Hakim, C. (2000). Research design: Successful designs in social and economic research . Routledge.

Jongbo, O. C. (2014). The role of research design in a purpose driven enquiry. Review of Public Administration and Management, 3 (6), 87–94.

Trochim, W., Donnelly, J., & Arora, K. (2015). Research methods: The essential knowledge base. CENGAGE Learning.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Wirtschaft/IFZ – Campus Zug-Rotkreuz, Hochschule Luzern, Zug-Rotkreuz, Zug , Switzerland

Stefan Hunziker & Michael Blankenagel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stefan Hunziker .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Hunziker, S., Blankenagel, M. (2021). Comparing Types of Research Designs. In: Research Design in Business and Management. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-34357-6_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-34357-6_5

Published : 10 November 2021

Publisher Name : Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN : 978-3-658-34356-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-658-34357-6

eBook Packages : Business and Economics (German Language)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

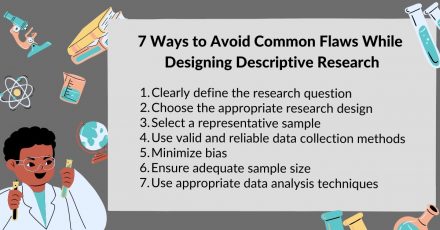

Bridging the Gap: Overcome these 7 flaws in descriptive research design

Descriptive research design is a powerful tool used by scientists and researchers to gather information about a particular group or phenomenon. This type of research provides a detailed and accurate picture of the characteristics and behaviors of a particular population or subject. By observing and collecting data on a given topic, descriptive research helps researchers gain a deeper understanding of a specific issue and provides valuable insights that can inform future studies.

In this blog, we will explore the definition, characteristics, and common flaws in descriptive research design, and provide tips on how to avoid these pitfalls to produce high-quality results. Whether you are a seasoned researcher or a student just starting, understanding the fundamentals of descriptive research design is essential to conducting successful scientific studies.

Table of Contents

What Is Descriptive Research Design?

The descriptive research design involves observing and collecting data on a given topic without attempting to infer cause-and-effect relationships. The goal of descriptive research is to provide a comprehensive and accurate picture of the population or phenomenon being studied and to describe the relationships, patterns, and trends that exist within the data.

Descriptive research methods can include surveys, observational studies , and case studies, and the data collected can be qualitative or quantitative . The findings from descriptive research provide valuable insights and inform future research, but do not establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Importance of Descriptive Research in Scientific Studies

1. understanding of a population or phenomenon.

Descriptive research provides a comprehensive picture of the characteristics and behaviors of a particular population or phenomenon, allowing researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the topic.

2. Baseline Information

The information gathered through descriptive research can serve as a baseline for future research and provide a foundation for further studies.

3. Informative Data

Descriptive research can provide valuable information and insights into a particular topic, which can inform future research, policy decisions, and programs.

4. Sampling Validation