11 min read

Seven case studies in carbon and climate

Every part of the mosaic of Earth's surface — ocean and land, Arctic and tropics, forest and grassland — absorbs and releases carbon in a different way. Wild-card events such as massive wildfires and drought complicate the global picture even more. To better predict future climate, we need to understand how Earth's ecosystems will change as the climate warms and how extreme events will shape and interact with the future environment. Here are seven pressing concerns.

The Far North is warming twice as fast as the rest of Earth, on average. With a 5-year Arctic airborne observing campaign just wrapping up and a 10-year campaign just starting that will integrate airborne, satellite and surface measurements, NASA is using unprecedented resources to discover how the drastic changes in Arctic carbon are likely to influence our climatic future.

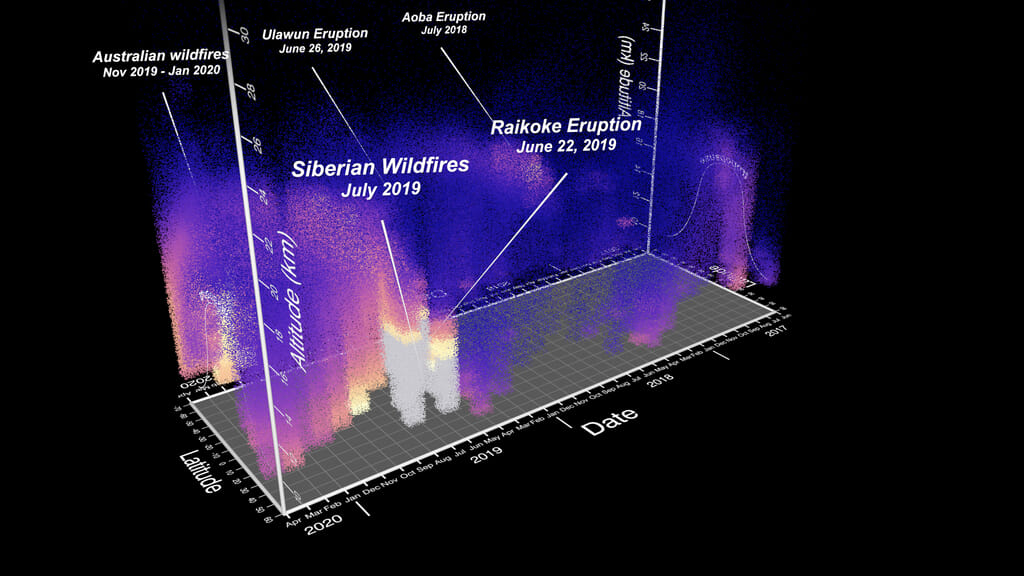

Wildfires have become common in the North. Because firefighting is so difficult in remote areas, many of these fires burn unchecked for months, throwing huge plumes of carbon into the atmosphere. A recent report found a nearly 10-fold increase in the number of large fires in the Arctic region over the last 50 years, and the total area burned by fires is increasing annually.

Organic carbon from plant and animal remains is preserved for millennia in frozen Arctic soil, too cold to decompose. Arctic soils known as permafrost contain more carbon than there is in Earth's atmosphere today. As the frozen landscape continues to thaw, the likelihood increases that not only fires but decomposition will create Arctic atmospheric emissions rivaling those of fossil fuels. The chemical form these emissions take — carbon dioxide or methane — will make a big difference in how much greenhouse warming they create.

Initial results from NASA's Carbon in Arctic Reservoirs Vulnerability Experiment (CARVE) airborne campaign have allayed concerns that large bursts of methane, a more potent greenhouse gas, are already being released from thawing Arctic soils. CARVE principal investigator Charles Miller of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Pasadena, California, is looking forward to NASA's ABoVE field campaign (Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment) to gain more insight. "CARVE just scratched the surface, compared to what ABoVE will do," Miller said.

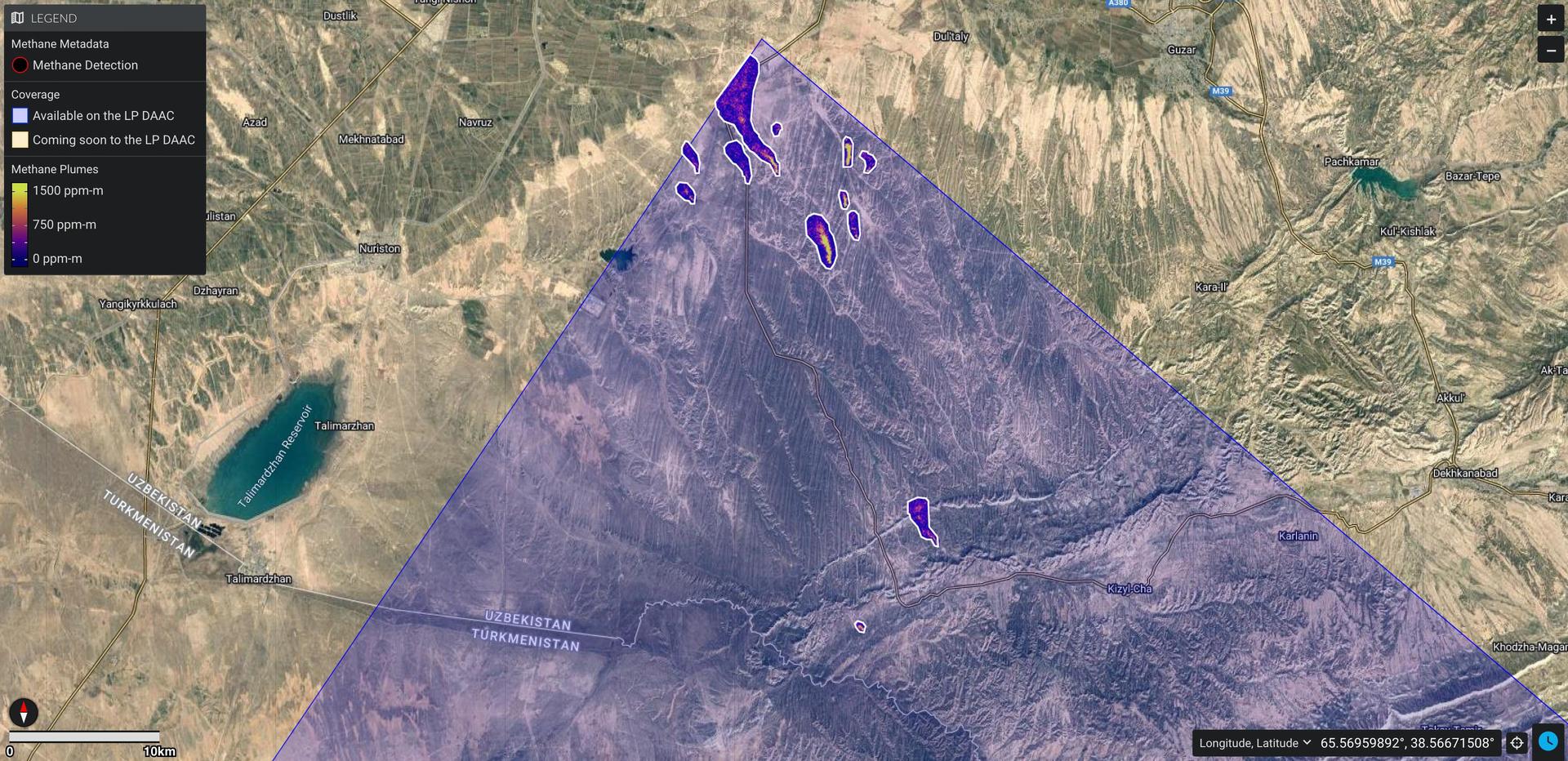

Methane is the Billy the Kid of carbon-containing greenhouse gases: it does a lot of damage in a short life. There's much less of it in Earth's atmosphere than there is carbon dioxide, but molecule for molecule, it causes far more greenhouse warming than CO 2 does over its average 10-year life span in the atmosphere.

Methane is produced by bacteria that decompose organic material in damp places with little or no oxygen, such as freshwater marshes and the stomachs of cows. Currently, over half of atmospheric methane comes from human-related sources, such as livestock, rice farming, landfills and leaks of natural gas. Natural sources include termites and wetlands. Because of increasing human sources, the atmospheric concentration of methane has doubled in the last 200 years to a level not seen on our planet for 650,000 years.

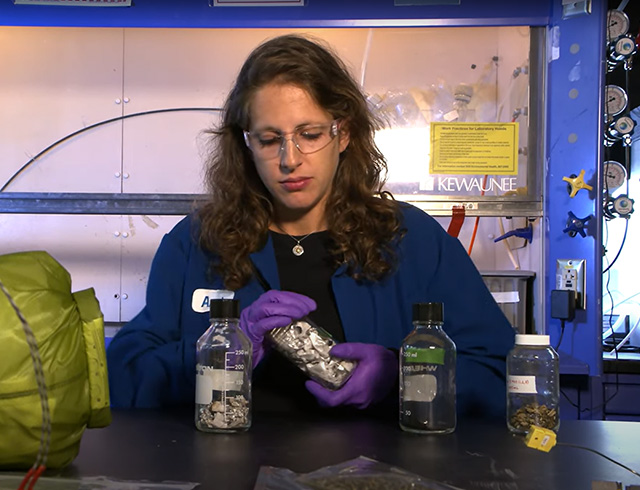

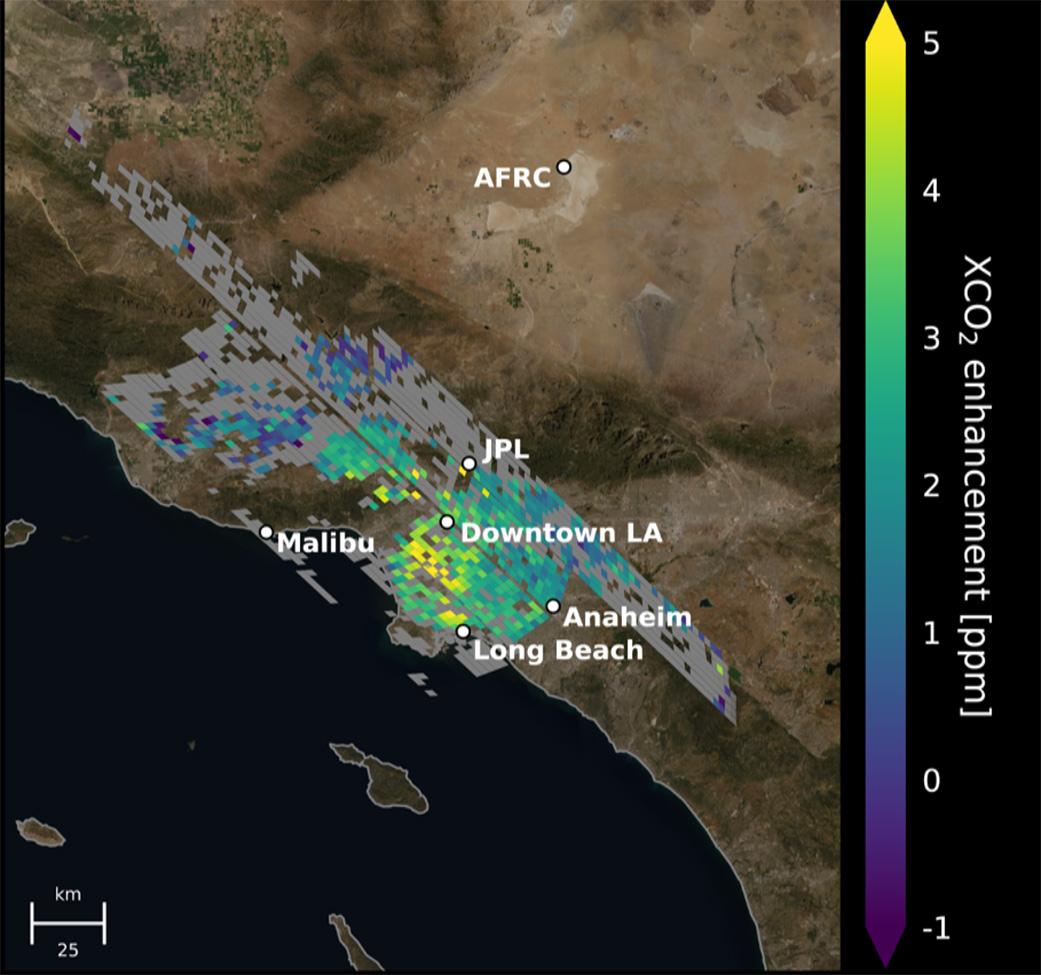

Locating and measuring human emissions of methane are significant challenges. NASA's Carbon Monitoring System is funding several projects testing new technologies and techniques to improve our ability to monitor the colorless gas and help decision makers pinpoint sources of emissions. One project, led by Daniel Jacob of Harvard University, used satellite observations of methane to infer emissions over North America. The research found that human methane emissions in eastern Texas were 50 to 100 percent higher than previous estimates. "This study shows the potential of satellite observations to assess how methane emissions are changing," said Kevin Bowman, a JPL research scientist who was a coauthor of the study.

Tropical forests

Tropical forests are carbon storage heavyweights. The Amazon in South America alone absorbs a quarter of all carbon dioxide that ends up on land. Forests in Asia and Africa also do their part in "breathing in" as much carbon dioxide as possible and using it to grow.

However, there is evidence that tropical forests may be reaching some kind of limit to growth. While growth rates in temperate and boreal forests continue to increase, trees in the Amazon have been growing more slowly in recent years. They've also been dying sooner. That's partly because the forest was stressed by two severe droughts in 2005 and 2010 — so severe that the Amazon emitted more carbon overall than it absorbed during those years, due to increased fires and reduced growth. Those unprecedented droughts may have been only a foretaste of what is ahead, because models predict that droughts will increase in frequency and severity in the future.

In the past 40-50 years, the greatest threat to tropical rainforests has been not climate but humans, and here the news from the Amazon is better. Brazil has reduced Amazon deforestation in its territory by 60 to 70 percent since 2004, despite troubling increases in the last three years. According to Doug Morton, a scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, further reductions may not make a marked difference in the global carbon budget. "No one wants to abandon efforts to preserve and protect the tropical forests," he said. "But doing that with the expectation that [it] is a meaningful way to address global greenhouse gas emissions has become less defensible."

In the last few years, Brazil's progress has left Indonesia the distinction of being the nation with the highest deforestation rate and also with the largest overall area of forest cleared in the world. Although Indonesia's forests are only a quarter to a fifth the extent of the Amazon, fires there emit massive amounts of carbon, because about half of the Indonesian forests grow on carbon-rich peat. A recent study estimated that this fall, daily greenhouse gas emissions from recent Indonesian fires regularly surpassed daily emissions from the entire United States.

Wildfires are natural and necessary for some forest ecosystems, keeping them healthy by fertilizing soil, clearing ground for young plants, and allowing species to germinate and reproduce. Like the carbon cycle itself, fires are being pushed out of their normal roles by climate change. Shorter winters and higher temperatures during the other seasons lead to drier vegetation and soils. Globally, fire seasons are almost 20 percent longer today, on average, than they were 35 years ago.

Currently, wildfires are estimated to spew 2 to 4 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere each year on average — about half as much as is emitted by fossil fuel burning. Large as that number is, it's just the beginning of the impact of fires on the carbon cycle. As a burned forest regrows, decades will pass before it reaches its former levels of carbon absorption. If the area is cleared for agriculture, the croplands will never absorb as much carbon as the forest did.

As atmospheric carbon dioxide continues to increase and global temperatures warm, climate models show the threat of wildfires increasing throughout this century. In Earth's more arid regions like the U.S. West, rising temperatures will continue to dry out vegetation so fires start and burn more easily. In Arctic and boreal ecosystems, intense wildfires are burning not just the trees, but also the carbon-rich soil itself, accelerating the thaw of permafrost, and dumping even more carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere.

North American forests

With decades of Landsat satellite imagery at their fingertips, researchers can track changes to North American forests since the mid-1980s. A warming climate is making its presence known.

Through the North American Forest Dynamics project, and a dataset based on Landsat imagery released this earlier this month, researchers can track where tree cover is disappearing through logging, wildfires, windstorms, insect outbreaks, drought, mountaintop mining, and people clearing land for development and agriculture. Equally, they can see where forests are growing back over past logging projects, abandoned croplands and other previously disturbed areas.

"One takeaway from the project is how active U.S. forests are, and how young American forests are," said Jeff Masek of Goddard, one of the project’s principal investigators along with researchers from the University of Maryland and the U.S. Forest Service. In the Southeast, fast-growing tree farms illustrate a human influence on the forest life cycle. In the West, however, much of the forest disturbance is directly or indirectly tied to climate. Wildfires stretched across more acres in Alaska this year than they have in any other year in the satellite record. Insects and drought have turned green forests brown in the Rocky Mountains. In the Southwest, pinyon-juniper forests have died back due to drought.

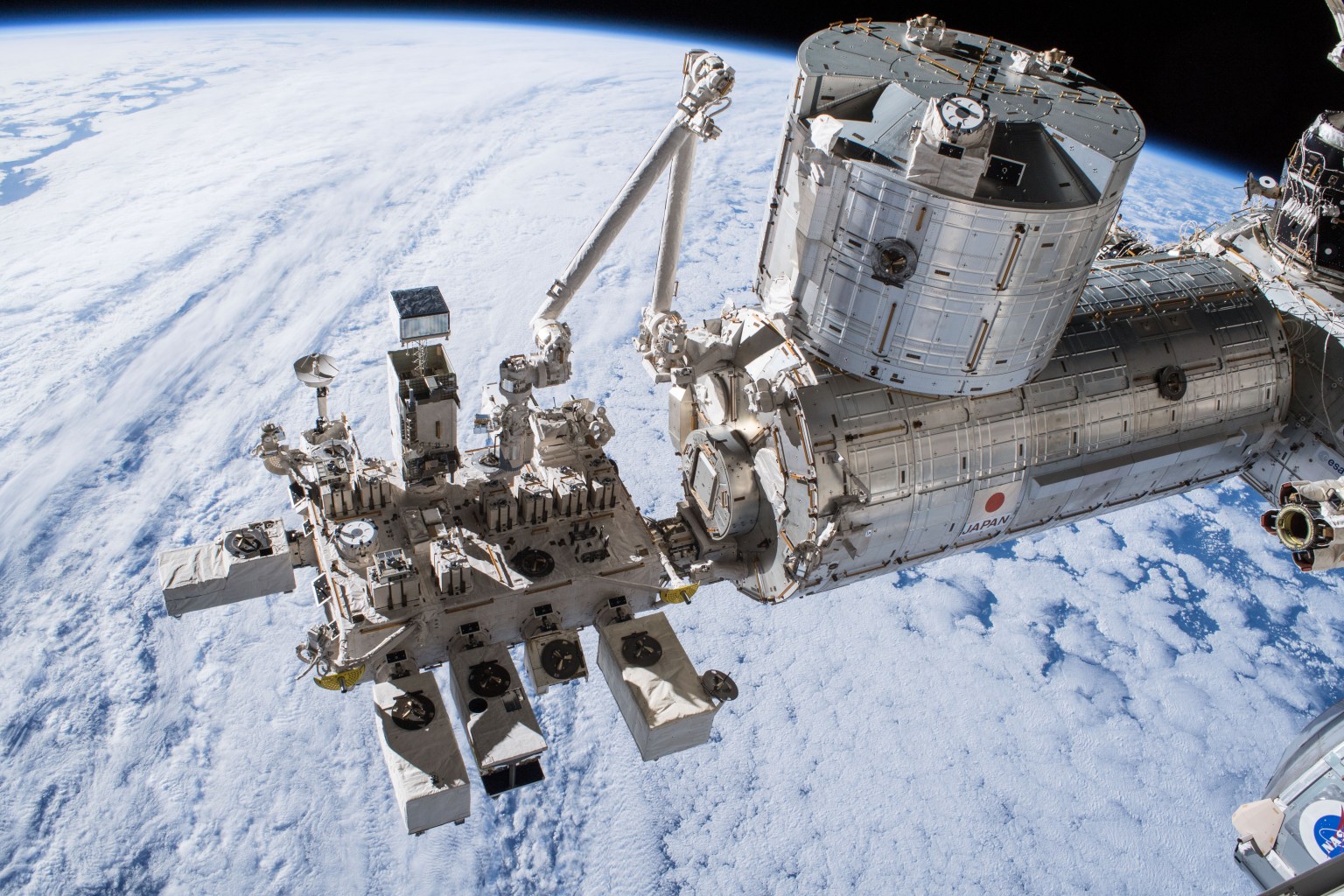

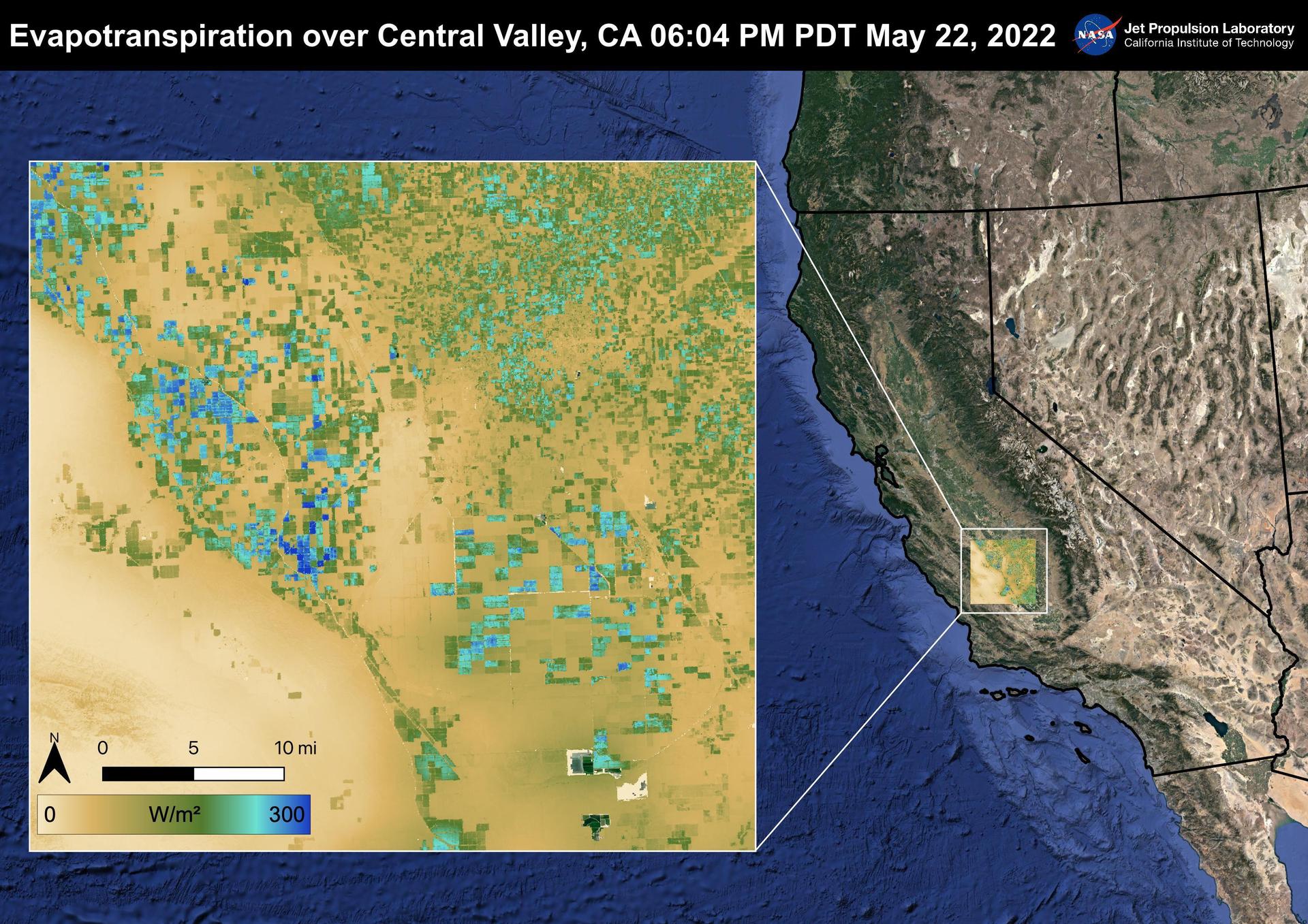

Scientists are studying North American forests and the carbon they store with other remote sensing instruments. With radars and lidars, which measure height of vegetation from satellite or airborne platforms, they can calculate how much biomass — the total amount of plant material, like trunks, stems and leaves — these forests contain. Then, models looking at how fast forests are growing or shrinking can calculate carbon uptake and release into the atmosphere. An instrument planned to fly on the International Space Station (ISS), called the Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) lidar, will measure tree height from orbit, and a second ISS mission called the Ecosystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer Experiment on Space Station (ECOSTRESS) will monitor how forests are using water, an indicator of their carbon uptake during growth. Two other upcoming radar satellite missions (the NASA-ISRO SAR radar, or NISAR, and the European Space Agency’s BIOMASS radar) will provide even more complementary, comprehensive information on vegetation.

Ocean carbon absorption

When carbon-dioxide-rich air meets seawater containing less carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas diffuses from the atmosphere into the ocean as irresistibly as a ball rolls downhill. Today, about a quarter of human-produced carbon dioxide emissions get absorbed into the ocean. Once the carbon is in the water, it can stay there for hundreds of years.

Warm, CO 2 -rich surface water flows in ocean currents to colder parts of the globe, releasing its heat along the way. In the polar regions, the now-cool water sinks several miles deep, carrying its carbon burden to the depths. Eventually, that same water wells up far away and returns carbon to the surface; but the entire trip is thought to take about a thousand years. In other words, water upwelling today dates from the Middle Ages – long before fossil fuel emissions.

That's good for the atmosphere, but the ocean pays a heavy price for absorbing so much carbon: acidification. Carbon dioxide reacts chemically with seawater to make the water more acidic. This fundamental change threatens many marine creatures. The chain of chemical reactions ends up reducing the amount of a particular form of carbon — the carbonate ion — that these organisms need to make shells and skeletons. Dubbed the “other carbon dioxide problem,” ocean acidification has potential impacts on millions of people who depend on the ocean for food and resources.

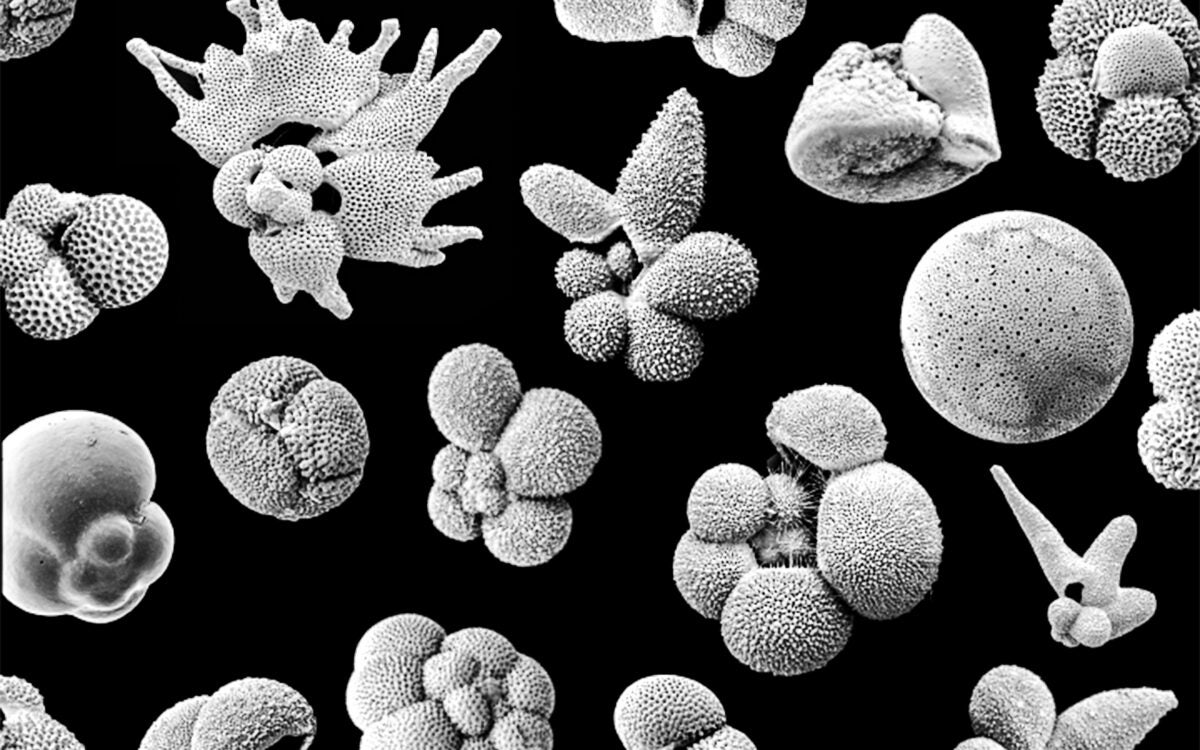

Phytoplankton

Microscopic, aquatic plants called phytoplankton are another way that ocean ecosystems absorb carbon dioxide emissions. Phytoplankton float with currents, consuming carbon dioxide as they grow. They are at the base of the ocean's food chain, eaten by tiny animals called zooplankton that are then consumed by larger species. When phytoplankton and zooplankton die, they may sink to the ocean floor, taking the carbon stored in their bodies with them.

Satellite instruments like the Moderate resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Terra and Aqua let us observe ocean color, which researchers can use to estimate abundance — more green equals more phytoplankton. But not all phytoplankton are equal. Some bigger species, like diatoms, need more nutrients in the surface waters. The bigger species also are generally heavier so more readily sink to the ocean floor.

As ocean currents change, however, the layers of surface water that have the right mix of sunlight, temperature and nutrients for phytoplankton to thrive are changing as well. “In the Northern Hemisphere, there’s a declining trend in phytoplankton,” said Cecile Rousseaux, an oceanographer with the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office at Goddard. She used models to determine that the decline at the highest latitudes was due to a decrease in abundance of diatoms. One future mission, the Pre-Aerosol, Clouds, and ocean Ecosystem (PACE) satellite, will use instruments designed to see shades of color in the ocean — and through that, allow scientists to better quantify different phytoplankton species.

In the Arctic, however, phytoplankton may be increasing due to climate change. The NASA-sponsored Impacts of Climate on the Eco-Systems and Chemistry of the Arctic Pacific Environment (ICESCAPE) expedition on a U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker in 2010 and 2011 found unprecedented phytoplankton blooms under about three feet (a meter) of sea ice off Alaska. Scientists think this unusually thin ice allows sunlight to filter down to the water, catalyzing plant blooms where they had never been observed before.

Related Terms

- Carbon Cycle

Explore More

As the Arctic Warms, Its Waters Are Emitting Carbon

Runoff from one of North America’s largest rivers is driving intense carbon dioxide emissions in the Arctic Ocean. When it comes to influencing climate change, the world’s smallest ocean punches above its weight. It’s been estimated that the cold waters of the Arctic absorb as much as 180 million metric tons of carbon per year […]

Peter Griffith: Diving Into Carbon Cycle Science

Dr. Peter Griffith serves as the director of NASA’s Carbon Cycle and Ecosystems Office at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Dr. Griffith’s scientific journey began by swimming in lakes as a child, then to scuba diving with the Smithsonian Institution, and now he studies Earth’s changing climate with NASA.

NASA Flights Link Methane Plumes to Tundra Fires in Western Alaska

Methane ‘hot spots’ in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta are more likely to be found where recent wildfires burned into the tundra, altering carbon emissions from the land. In Alaska’s largest river delta, tundra that has been scorched by wildfire is emitting more methane than the rest of the landscape long after the flames died, scientists have […]

Discover More Topics From NASA

Explore Earth Science

Earth Science in Action

Earth Science Data

Facts About Earth

U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit

- Steps to Resilience

- Case Studies

Communities, businesses, and individuals are taking action to document their vulnerabilities and build resilience to climate-related impacts. Click dots on the map to preview case studies, or browse stories below the map. Use the drop-down menus above to find stories of interest. To expand your results, click the Clear Filters link.

A Climate for Resilience

A Community Effort Stems Runoff to Safeguard Corals in Puerto Rico

A Community Works Together to Reduce Damages from Flooding

A Coral Bleaching Story With an Unknown Ending

A New Generation of Water Planners Confronts Change Along the Colorado River

A Road-Flooding Fix for a California State Park

A Town with a Plan: Community, Climate, and Conversations

Addressing Links Between Climate and Public Health in Alaska Native Villages

Addressing Short- and Long-Term Risks to Water Supply

Addressing Water Supply Risks from Flooding and Drought

After Katrina, Health Care Facility's Infrastructure Planned to Withstand Future Flooding

After Record-Breaking Rains, a Major Medical Center's Hazard Mitigation Plan Improves Resilience

Alaska Native Villages Work to Enhance Local Economies as They Minimize Environmental Risks

Alaskan Tribes Join Together to Assess Harmful Algal Blooms

Alert System Helps Strawberry Growers Reduce Costs

All Hands on Deck: Creating Green Infrastructure to Combat Flooding in Toledo

Amending Land Use Codes for Natural Infrastructure Planning

American Rivers: Increasing Community and Ecological resilience by Removing a Patapsco River Fish Barrier

An Inland City Prepares for a Changing Climate

An Integrated Plan for Water and Long-Term Ecological Resilience

Analyzing Future Urban Growth and Flood Risk in North Carolina

And the Trees Will Last Forever

Anticipating and Preventing the Spread of Invasive Plants

Aquifer Storage and Recovery: A Strategy for Long-Term Water Security in Puerto Rico

Asheville Makes a Plan for Climate Resilience

Ashland Climate and Energy Action Plan

Assessing a Tropical Estuary's Climate Change Risks

Assessing Climate Risks in a National Estuary

Assessing the Timing and Extent of Coastal Change in Western Alaska

Balancing Variable Water Supply With Increasing Demand in a Changing Climate

Battling Blazes Across Borders

Better Soil, Better Climate

Blue Lake Rancheria Tribe Undertakes Innovative Action to Reduce the Causes of Climate Change

Boosting Community Storm Resilience in Alaska

Boosting Ecosystem Resilience in the Southwest's Sky Islands

Bracing for Heat

- Our history

- Charitable Trust

- Our local action groups

- Friends of the Earth Cymru

- Friends of the Earth Northern Ireland

- Our international network

- Fossil free future

- Energy crisis

- Climate plan court case

- Double tree cover

- Planet over Profit

- Postcode Gardeners

- Mayoral elections

- Planning and environmental law

- Anti-racism

- Planet Protectors

- Send an e-card

- Fundraise for Friends of the Earth

- Support a campaign

- Join a local action group

- Switch to green companies

- Business partnerships

- Jobs and volunteering

- Publications

40 councils leading the way on climate

- The full set of case studies can be viewed here

Local authorities are crucial to the delivery of the UK’s transition to a cleaner, greener future. But progress needs to be accelerated in every local area if the UK’s climate and nature targets are to be met, Friends of the Earth and the climate charity Ashden say today as they publish new resources for councils and campaigners.

The environmental organisations have drawn together a unique set of case studies which showcase the inspiring work of 40 local authorities. They demonstrate how councils have implemented successful initiatives and solutions in response to pressing local challenges, as well as the need to fulfil their own green targets and counter the climate emergency.

These examples of best practice spanning areas such as nature restoration, energy efficiency and transport, highlight the many ways councils can make a substantial difference where they operate, and overcome some of the barriers that currently frustrate progress on local issues as well as the climate.

Among those included as part of the huge bank of examples, are:

- Warrington Borough Council , which raised funds for a renewable energy project through community municipal bonds that could be purchased for as little as £5 by residents

- Blaenau Gwent Council , which set up a citizens assembly for just £50,000 to engage the local community in climate decision-making

- Nottingham City Council , which raised millions for better public transport in the local area through its workplace parking levy

- North East Derbyshire District Council , which upgraded hundreds of council homes to improve energy efficiency and alleviate fuel poverty simultaneously

- Wirral Council , which adopted an ambitious tree strategy to plant 210,000 by 2030 and protect existing trees

- Waltham Forest Council , which has almost fulfilled its target to completely divest its pension funds from fossil fuels within 5 years

- Derry and Strabane District Council, which is one of the first local authorities in the UK to have created a zero-waste circular economy strategy

Most councils have now declared a climate emergency, and 85% have formulated climate action plans, but the quality and scale of ambition still varies greatly between local authorities. A lack of clarity from central government about the role that councils must play in the transition to a safer planet remains a significant stumbling block for the sector, alongside a shortfall in funding, resources and powers.

However, the role of councils in the coming years will be essential in meeting the UK’s decarbonisation targets. Unless progress at the local level advances swiftly, both local and national ambitions to make the country future fit will fail to be realised.

That’s why Friends of the Earth and Ashden have developed these 40 case studies, so that the wealth of knowledge and learnings that already exist within the sector can be shared widely. It is hoped that all councils can learn from the range of practical insights and examples that have been collected to help them replicate best practice in their areas.

The two organisations also hope to amplify the many benefits that come with action on climate. By making the switch to green, clean infrastructure, local authorities can guarantee warmer homes, better health and hundreds of thousands of long-term jobs in sustainable industries for their residents.

For the full set of case studies, please visit the Take Climate Action website .

Sandra Bell, campaigner at Friends of the Earth, said:

“Whether it’s declaring a climate emergency or producing a plan to curb climate and nature breakdown, most local authorities have shown they want to do more to protect our planet. But in spite of this, we’re still not seeing local progress at the rate needed to halt the worst climate impacts.

“For many councils, it’s a question of funding and powers, both of which are in short supply. But we have identified a huge number of ways that local authorities can accelerate climate progress where they operate. It’s vital that councils use the powers and resources they have now to drive things forward, while lobbying government for more support in the meantime.

“It’s inspiring to see how councils have overcome some of their own local challenges with creative and practical climate solutions, and we hope that others will use these examples as the springboard to further their own climate ambitions.”

Harriet Lamb, CEO of climate charity Ashden, says:

“Behind the scenes, local authorities are often doing the climate heavy-lifting, engaging communities and seeking to cut carbon in neighbourhoods. They are trialling new initiatives from raising funds through community bonds to training people in the skills of tomorrow such as for retrofitting homes or planting parklets. These initiatives while being good for the planet also have wider benefits – such as improving health when air quality improves through fewer private cars, or warmer homes and lower fuel bills from insulating homes.”

- The full set of case studies compiled by Friends of the Earth and Ashden can be viewed here . Further examples of best practice are due to be published in due course.

- Friends of the Earth’s Climate Action Plan for Councils sets out 50 important actions that councils can take to address the climate and ecological emergencies while setting out a path to green and fair local economic recovery. Each of the case studies relate directly to 40 of these actions.

- This set of case studies showcases specific examples of good practice relating to climate action, but this is not necessarily an endorsement of the wider work that these councils are doing.

- Friends of the Earth and Ashden are part of a coalition of local government, environmental, and research organisations that has published a Blueprint for accelerating climate action and a green recovery at the local level which sets out the national leadership, policies, powers and funding needed to empower local authorities to deliver at scale, working together with communities and businesses.

- There are over 300 Climate Action groups and Friends of the Earth local groups helping to provide the local solution to a global crisis. They harness community power to make our neighbourhoods greener and more climate friendly. They have convinced local decision-makers to rollout ambitious Climate Action Plans and many are now focussed on turning those plans into action.

- To find out which councils have declared climate emergencies and adopted Climate Action Plans, please visit: https://data.climateemergency.uk/

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, how academic research and news media cover climate change: a case study from chile.

- 1 Education, Research, and Innovation (ERI) Sector, NEOM, Tabuk, Saudi Arabia

- 2 Departamento de Ciencias del Lenguaje, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Introduction: Climate change has significant impacts on society, including the environment, economy, and human health. To effectively address this issue, it is crucial for both research and news media coverage to align their efforts and present accurate and comprehensive information to the public. In this study, we use a combination of text-mining and web-scrapping methods, as well as topic-modeling techniques, to examine the similarities, discrepancies, and gaps in the coverage of climate change in academic and general-interest publications in Chile.

Methods: We analyzed 1,261 academic articles published in the Web of Science and Scopus databases and 5,024 news articles from eight Chilean electronic platforms, spanning the period from 2012 to 2022.

Results: The findings of our investigation highlight three key outcomes. Firstly, the number of articles on climate change has increased substantially over the past decade, reflecting a growing interest and urgency surrounding the issue. Secondly, while both news media and academic research cover similar themes, such as climate change indicators, climate change impacts, and mitigation and adaptation strategies, the news media provides a wider variety of themes, including climate change and society and climate politics, which are not as commonly explored in academic research. Thirdly, academic research offers in-depth insights into the ecological consequences of global warming on coastal ecosystems and their inhabitants. In contrast, the news media tends to prioritize the tangible and direct impacts, particularly on agriculture and urban health.

Discussion: By integrating academic and media sources into our study, we shed light on their complementary nature, facilitating a more comprehensive communication and understanding of climate change. This analysis serves to bridge the communication gap that commonly, exists between scientific research and news media coverage. By incorporating rigorous analysis of scientific research with the wider reach of the news media, we enable a more informed and engaged public conversation on climate change.

1. Introduction

Climate change is the most pervasive threat to the world's natural, social, political, and economic systems. Human activities have caused a rise in greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations in the atmosphere and caused the earth's surface temperature to rise, leading to many other changes around the world—in the atmosphere, on land, and in the oceans ( Wyser et al., 2020 ; Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021 ). Indicators of these changes include increases in global average air and ocean temperature, rising global sea levels ( Zemp et al., 2019 ; Garcia-Soto et al., 2021 ; Oliver et al., 2021 ), amplification of permafrost thawing and glacier retreat ( Sommer et al., 2020 ; Wilkenskjeld et al., 2022 ), reduction of snow and ice cover ( Shepherd et al., 2018 ), ocean acidification ( Doney et al., 2020 ) and stronger and more frequent extreme events such as heatwaves, storms, droughts, wildfires, and flooding ( Abram et al., 2021 ; van der Wiel and Bintanja, 2021 ). These changes are projected to continue throughout at least the rest of this century ( Smale et al., 2019 ; Cook et al., 2020 ; Kwiatkowski et al., 2020 ; Ortega et al., 2021 ). Mitigation and adaptation are two complementary strategies for addressing climate change ( Abubakar and Dano, 2020 ; Diamond et al., 2020 ; Tosun, 2022 ). Mitigation focuses on reducing emissions or enhancing GHG sinks, while adaptation involves building resilience to the unavoidable impacts on people and ecosystems. To be successful, these efforts require a deep scientific understanding, as well as the active engagement of the scientific community, civil society, and other stakeholders ( Wamsler, 2017 ; Tai and Robinson, 2018 ; Gonçalves et al., 2022 ).

News media and academic research have distinct roles in communicating scientific findings on climate change ( Corbett, 2015 ). News media rapidly disseminate scientific findings to a broader audience, shaping public understanding and influencing science-policy translation, practices, politics, public opinion, and understanding of climate change. They select and frame information to shape public awareness and perception, often influenced by various factors such as political, economic, scientific, ecological, or social events. Academic research provides a scientific foundation, evidence-based insights, and focuses on rigorous methodologies, data analysis, and the generation of scientific knowledge related to climate change. Aligning news media and academic research in their coverage is essential for effectively addressing climate change. Consistent messaging and shared thematic structures between media and academia build public trust and understanding, enabling informed decision-making and collective action. However, it's important to acknowledge that variations may exist between news media and academic research coverage due to factors like economic development, political influences, and differing focuses on the societal dimension of climate change ( Hase et al., 2021 ).

Over the past decade, media coverage of climate science has grown in accuracy, though the extent and type of coverage varies between countries and is often connected to political, scientific, ecological, or social events ( Shehata and Hopmann, 2012 ; Schmidt et al., 2013 ; Lopera and Moreno, 2014 ; Schäfer and Schlichting, 2014 ; Stecula and Merkley, 2019 ; Hase et al., 2021 ; Dubash et al., 2022 ). A growing body of experimental research has explored how climate change has been represented in news media ( Dotson et al., 2012 ; Wozniak et al., 2015 ; Barkemeyer et al., 2017 ; Bohr, 2020 ; Keller et al., 2020 ) as well as providing an overview of the state of knowledge on the science of climate change ( Berrang-Ford et al., 2015 ; Pacifici et al., 2015 ; Rojas-Downing et al., 2017 ; Cianconi et al., 2020 ; Fawzy et al., 2020 ; Olabi and Abdelkareem, 2022 ; Talukder et al., 2022 ). As far as we know, however, no previous research has investigated simultaneously news media coverage and academia's research agenda on climate change globally or locally. Therefore, the primary goal of our study is to evaluate, by means of text-mining, web-scraping methods, and topic-modeling techniques, the extent of alignment between news media and academic research in their coverage of climate change topics in the context of Chile. By examining the content and comparing the thematic focus of climate change discourse in both sources, this study will contribute to understanding the similarities, discrepancies, and gaps in the coverage of climate change in Chile. Furthermore, the findings can inform future efforts to improve the alignment and comprehensiveness of climate change communication between news media and academia, ultimately promoting public awareness and understanding of this critical global issue ( Leuzinger et al., 2019 ; Albagli and Iwama, 2022 ).

Chile is particularly interesting as study model due to a variety of political, geographic, ecological, political, and social factors. Despite contributing only 0.23% to global GHG emissions ( Labarca et al., 2023 ), Chile is highly vulnerable to climate change impacts. Evidence of current and future effects of climate change on Chilean territory has been mounting ( Bozkurt et al., 2017 ; Araya-Osses et al., 2020 ; Martínez-Retureta et al., 2021 ), which could have detrimental consequences for citizens' health and wellbeing by impacting key sectors such as fisheries and aquaculture, forestry, agriculture and livestock, mining, energy, and water resources. Additionally, the Government of Chile chaired the 2019 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP25) in Spain ( Navia, 2019 ) and has committed to reducing its GHG emissions by 30% compared to 2007 levels as part of its nationally determined contributions. Previous studies have explored ideological bias in media coverage of climate change in Chile ( Dotson et al., 2012 ), however there is a lack of research comparing academic research with news media. Although this study focuses on climate change in Chile, its results more broadly inform gaps in the coverage of climate change between academic and media discourse and emphasizes the importance of analyzing both sources to improve public understanding of climate change issues.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. academic articles.

The ISI Web of Science WOS Core Collection ( https://apps.webofknowledge.com/ ) and Scopus ( https://www.scopus.com/home.uri ) database were chosen for the collection of academic articles. On January 18, 2023, we retrieved all publications related to climate change in Chile using the following Boolean search strategy: [(climat * chang * OR global chang * OR “climat * emergenc * OR “climat * crisis OR “global warming) AND Chile * ]. A comprehensive search strategy was employed to identify relevant publications from 2012 to 2022, without any language restrictions Following the search based on these criteria, a total of 1,758 articles from Web of Science (WOS) and 1,730 articles from Scopus were retrieved. The search results were downloaded in.xlsx format for further analysis. To ensure data accuracy, a manual comparison was conducted between the SCOPUS and WOS records, which involved examining the title, primary author, source title, and year of publication. All the articles obtained, including their titles and abstracts, were exclusively in English. Duplicate articles were discarded. We next used the title and abstract- when available- of each article to ensure we only included studies aimed at understanding climate change in Chile either by Chilean or international scientists. We include original articles and reviews, but not conference proceedings or books/book chapters, in our analysis. Articles without an abstract were also excluded. This resulted in 1,261 articles used to build the academic corpus, which comprises the following metadata for each document: database, title, abstract, and publication year.

2.2. News media articles

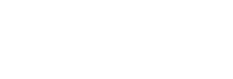

Climate Change coverage from Chilean electronic news platforms was also studied over the 10-year period from 2012 to 2022. This time period was determined by the availability of items on the selected platforms. The sample included eight electronic platforms: La Tercera, Meganoticias, CNN Chile, El Mostrador, T13, CHV Noticias, El Desconcierto and Diario Financiero. The platforms were chosen based on their national coverage, their high circulation and accessibility without a subscription fee. The approach to retrieve the articles was as follows. First, tags directly related to climate change were identified: “climate change,” “global warming,” “climatic crisis,” and “climatic emergency.” This strategy allows for a systematization of sampling. For each article, the name of the media, tag, headline, date, and URL of the source page were retrieved using the Rvest ( Wickham, 2016 ) and RSelenium ( Harrison and Harrison, 2022 ) R-packages. The URLs were then used to extract the articles' full text (body). Those articles that were not retrievable using this method due to forbidden access or any other restrictions in the source page were discarded from the collection. A total of 6,056 news articles were retrieved between January 06 and 15, 2023. Because a news item may include different tags, we removed duplicate articles for each of the platforms. Articles in which the date could not be retrieved were also discarded. After this filtering process, we obtained 5024 articles, which were used to build the news media corpus ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 . Information of electronic platform and news media articles retrieved.

2.3. Preprocessing

The corpora were preprocessed as follows: performing tokenization into unigrams (one word) using the “tidytext” R-package ( Silge and Robinson, 2016 ), normalizing text into lowercase and removing punctuation, symbols, numbers, and HTML tags. English and Spanish lists of stop words were applied to the academic ( Puurula, 2013 ) and news media (a proposed list of Spanish stop-words was used; Díaz, 2016 ) corpus, respectively. Additional terms (e.g., academic corpus: “mission”, “b.v”, “rights”, “reserved”; news media corpus: “tags”, “u-uppercase”, “video”, “cnn”, “iphone”) were added to the list of stop words as frequent words present across many documents that are expected not to be related to any topic and whose presence might hinder the interpretation of the results. Also, plural words were converted to singular (e.g., academic corpus: “glaciers” to “glacier”, “southern” to “south”; news media corpus: “gases” to “gas”, “emissions” to “emission”). To preprocess the corpora, we used the “quanteda” R-package ( Benoit et al., 2018 ).

2.4. Publication trends

The Mann-Kendall trend test was used to detect an increase, decrease or no difference in the number of articles published for both academic and news media corpora. Mann-Kendall test is a distribution-free test that can be used to identify monotonic trends for as few as four samples ( Mann, 1945 ; Kendall, 1975 ). This is relevant for our purposes, given the results of our study were limited by a small sample size ( n = 10). In brief, we tested the null hypothesis if the data are identically distributed (i.e., non-trend). The alternative hypothesis was that the data follow a monotonic trend. This monotonic trend could be positive or negative. We fitted the Mann-Kendall model using the “Kendall” R-package ( McLeod and McLeod, 2015 ).

2.5. LDA topic modeling

Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), a probabilistic topic-modeling technique, was used to identify the most common topics and themes in both corpora. Briefly, topic modeling is an unsupervised machine learning technique which can identify co-occurring terms and patterns from collections of text documents ( Kherwa and Bansal, 2019 ). Latent LDA is a well-suited unsupervised algorithm for general topic modeling tasks, particularly when dealing with long documents, which is the case with analyzing academic or news media articles ( Anupriya and Karpagavalli, 2015 ; Goyal and Kashyap, 2022 ). LDA is a three-level hierarchical Bayesian model that employs three basic elements, namely the corpus which is constituted from a set of documents that is composed from a group of words ( Blei et al., 2003 ; Blei, 2012 ). LDA can infer probabilistic word clusters, called topics, based on patterns of (co) occurrence of words in the documents that are analyzed. LDA models each document as a mixture of topics and the model generates automatic summaries of topics in terms of a discrete probability distribution over words for each topic, and further infers per-document discrete distributions over topic. LDA output can be used logically to classify the documents according to the topic it belongs to.

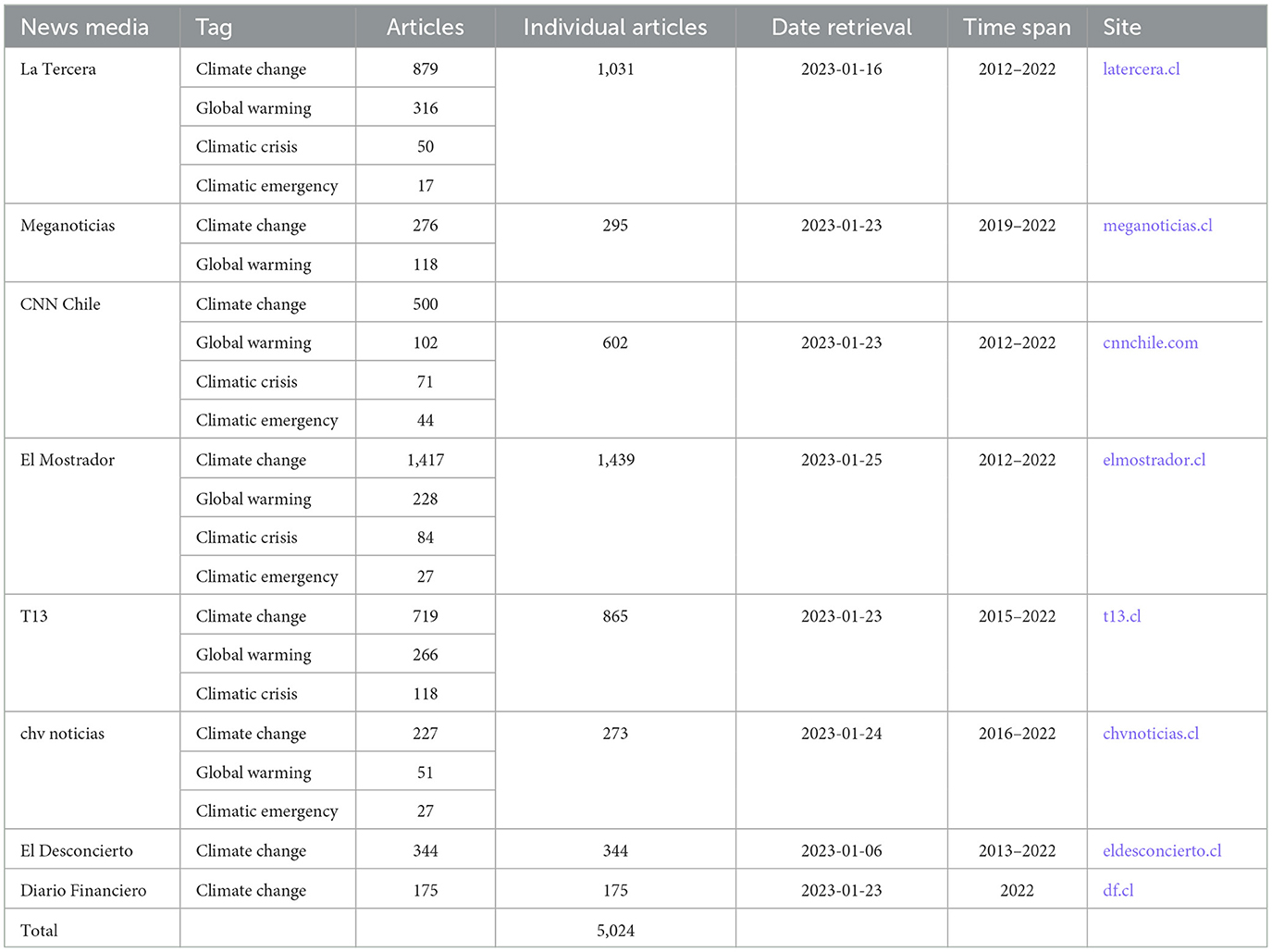

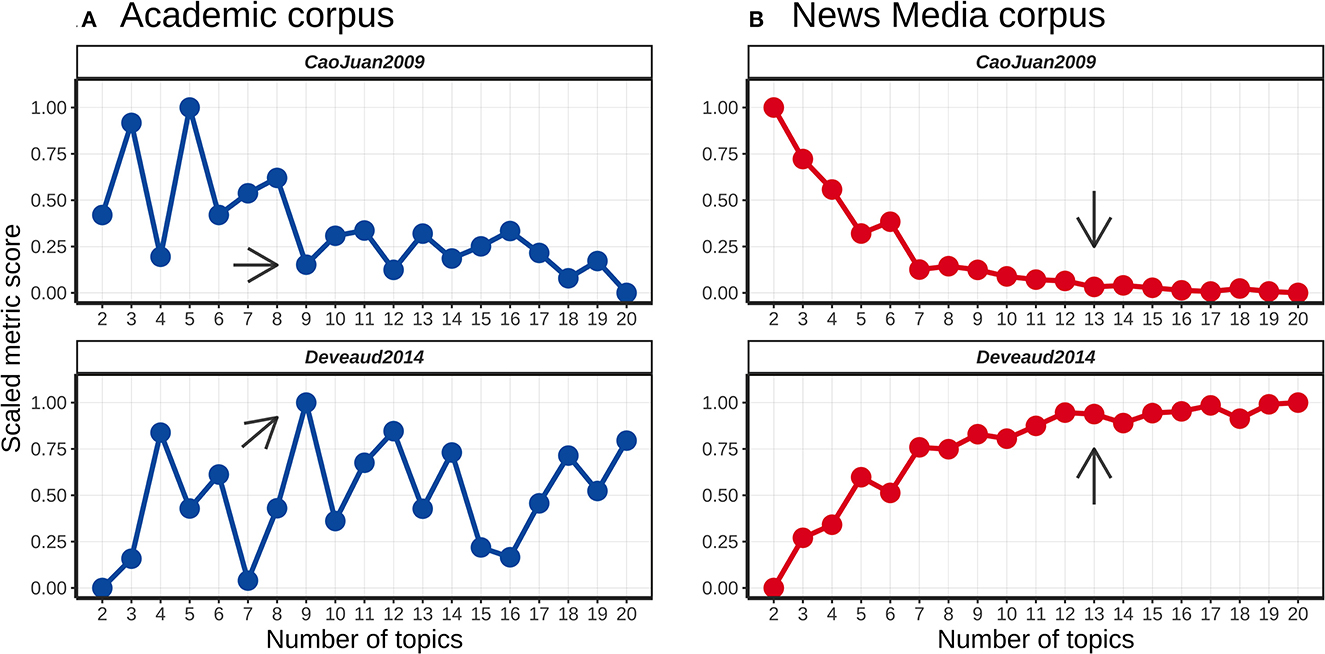

Before performing the LDA, the number of topics needs to be estimated. In this study, we used two metrics from the R-package “ldatuning” ( Nikita, 2016 ): CaoJuan2009 and Deveaud2014. Whereas measure CaoJuan2009 has to be minimized ( Cao et al., 2009 ), Deveaud2014 has to be maximized ( Deveaud et al., 2014 ). Both metrics showed a plateau in the curves at 9 and 13 topics (k) for both academic and news media corpora, respectively ( Figure 1 ). For each corpus, we fitted the LDA model using the “topicmodels” R-package ( Grün and Hornik, 2011 ). The collapsed Gibbs sampling method was used to estimate the LDA parameters with 1,000 iterations for k = 13 and k = 9 topics for academic and news media corpora, respectively). Once generated, we assigned a label that adds an interpretable meaning to each of the inferred topics. It is important to note that the news media corpus was analyzed in its original language (i.e., Spanish), but the results (i.e., topics and themes) are presented in English.

Figure 1 . Suggested number of topics in the (A) academic and (B) news media corpora using the CaoJuan2009 and Deveaud2014 metrics.

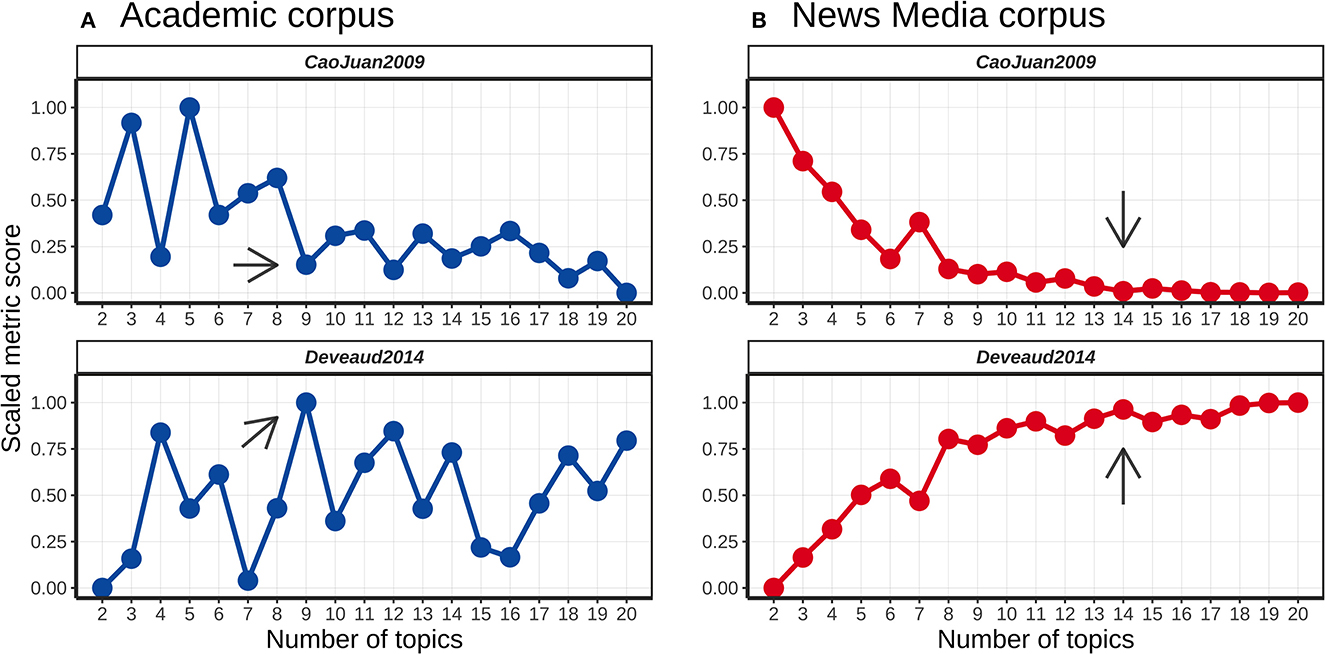

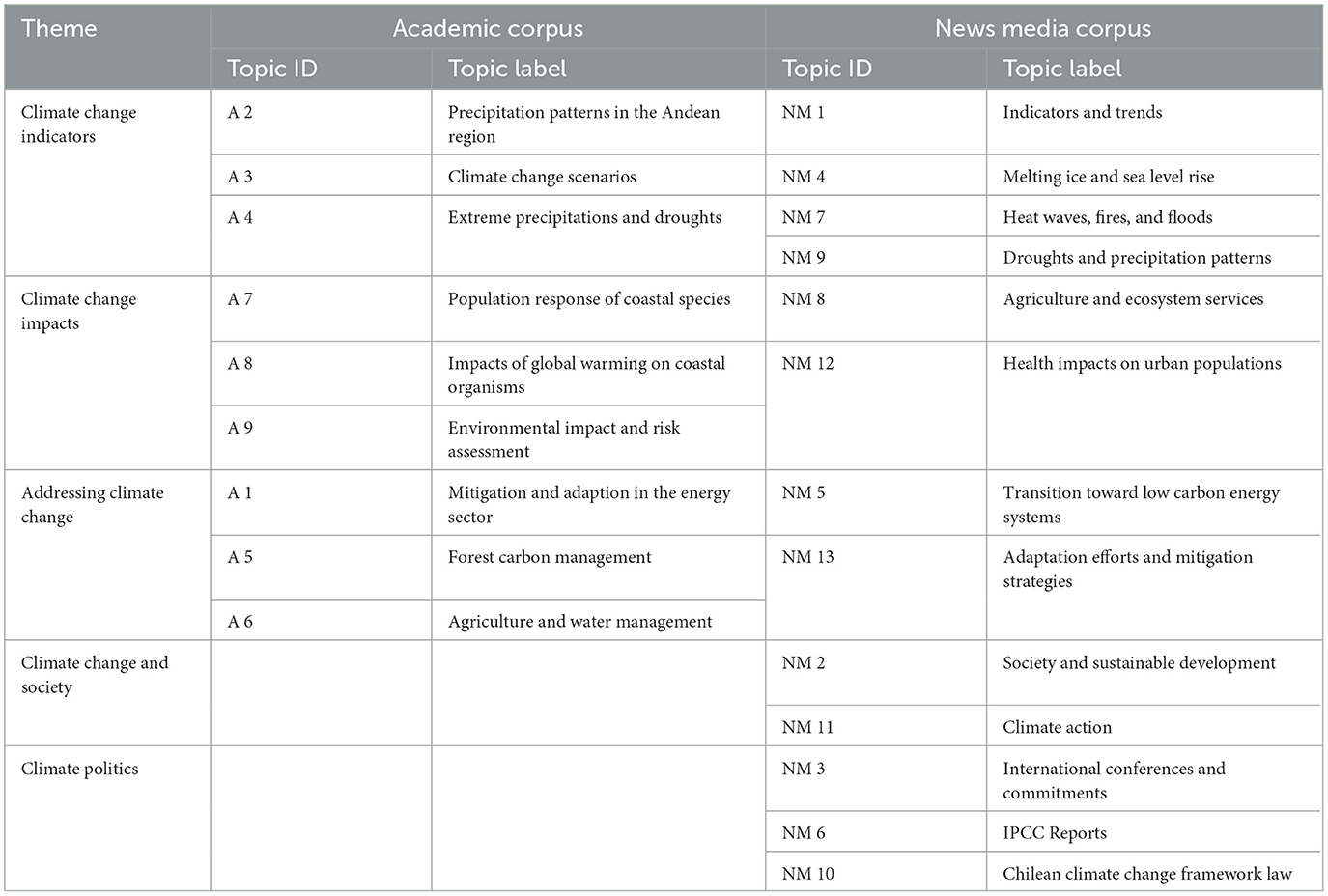

Lastly, we used a variation of Vu et al. (2019) and Keller et al. (2020) procedures to sort the topics into five overarching themes: climate change indicators (e.g., warming, temperature, glaciers, sea-level, oceans, coastal, weather, wildfires, drought, etc.); climate change impacts (e.g., water, food, agriculture, livestock, biodiversity, ecosystems, financial etc.); climate change and society (e.g., health, wellbeing, pollution, education, humanity, population, etc.); climate politics (e.g., government, law, policy, regulation, U.N., COP, agreement, etc.); and addressing climate change (e.g., adaptation, mitigation, action, renewable, GHG, emissions, fuel, management, etc.). Figure 2 summarizes the steps of data retrieval, corpus creation and content analysis.

Figure 2 . Data collection and analysis framework.

2.6. Visualizations

Data visualizations were performed using R ( R Core Team, 2022 ) in conjunction with the software package ggplot2 ( Wickham et al., 2016 ) and dplyr ( Wickham et al., 2022 ).

3.1. Publications trends over 2012–2022 period

National and international authors published 1,261 research academic articles related to climate change in Chile during the 2012–2022 period. More than half of these articles, approximately 66.0%, were published from 2019 onwards. In terms of news media, we retrieved 5,024 articles over the period 2012–2022. Of these articles, 76.6% were published in the past 4 years. Figure 3 shows trends in the number of articles for both the academic and news media corpus. Note that the scales of the y-axis are different between corpora. Mann-Kendall trend analysis showed a significant and upward trend for the number of academic articles (τ = 1, p < 0.01, Figure 3A ) and news media articles (τ = 0.85, p = < 0.05, Figure 3B ) articles. The number of articles published per year follows a similar trend in both corpora, however, news media articles showed a sharp increase in 2019. After these peaks, the number of published media articles decreased before an additional increase was observed.

Figure 3 . Annual trend of (A) academic and (B) news media articles published from 2012 to 2022.

3.2. LDA topic modeling

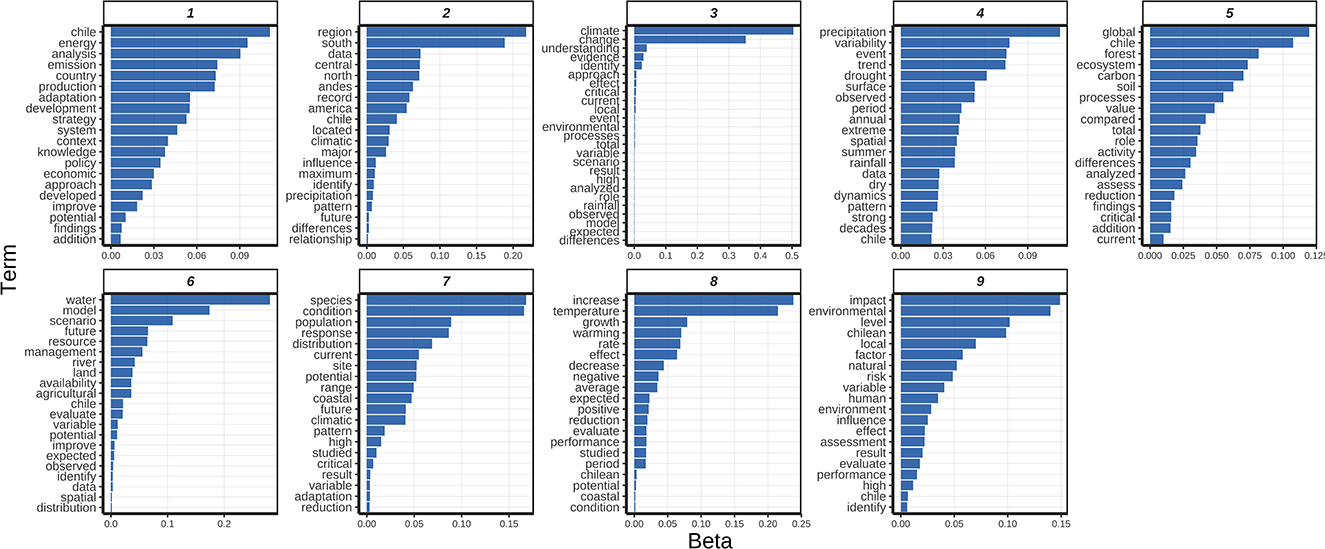

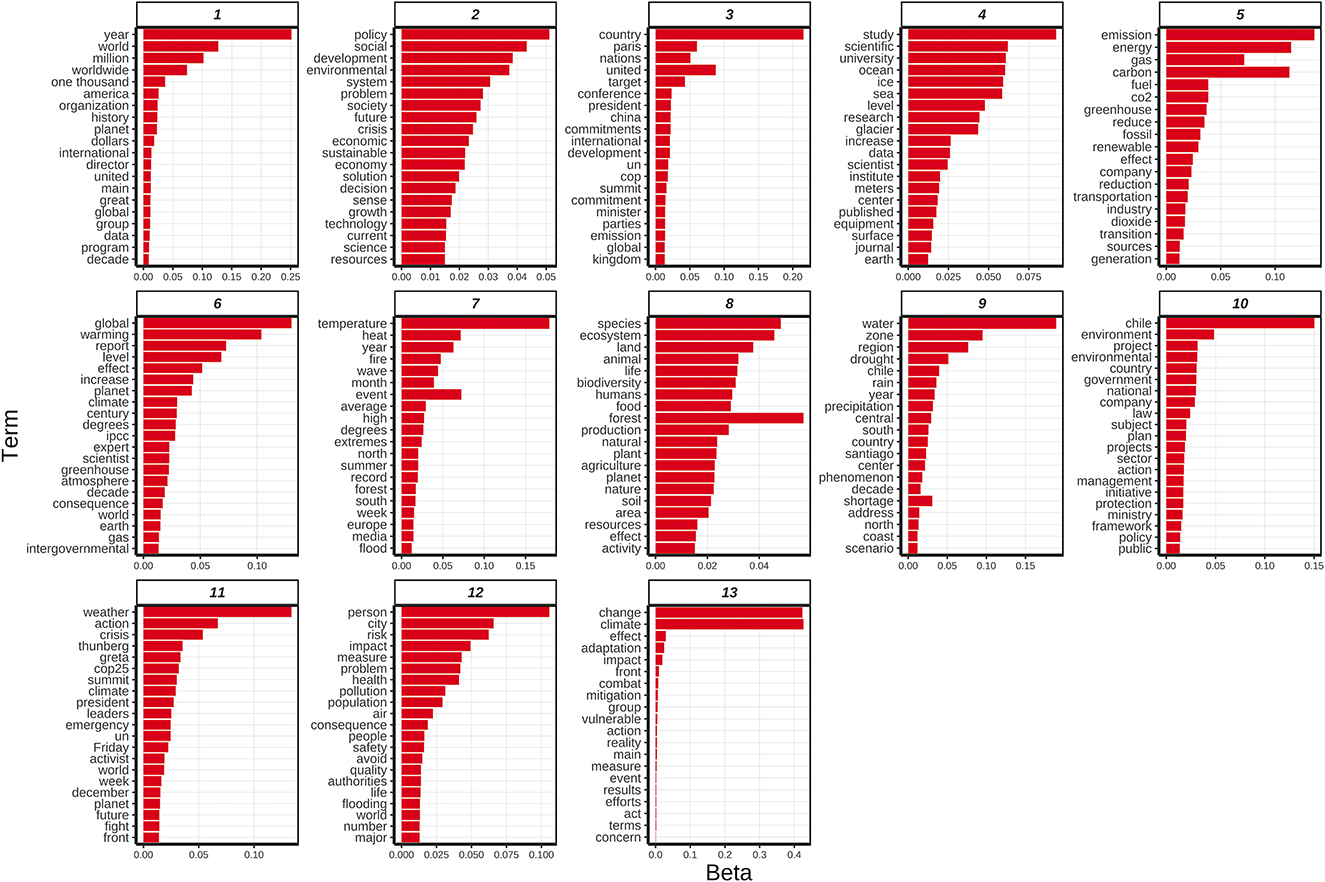

The output of the LDA for the academic and news media corpora are displayed in Table 2 . Topics were labeled based on the top 15 keywords with the largest probabilities in topics vectors ( Figures 4 , 5 ) and content in most relevant articles. In the academic corpus, the nine topics extracted were categorized into three overarching themes: “climate change indicators” (Topic A 2, A3 and A 4), “climate change impacts” (Topics A 7, A 8, and A 9), and “addressing climate change” (Topics A 1, A 5, and A 6). No topics in the academic corpus were classified as “climate change and society” or “climate politics”. The 13 topics extracted from news media corpus were classified in five themes: “climate change indicators” (Topic NM 1, NM 4, NM 7, and NM 9), “climate change impacts” (Topic NM 8 and NM 12), “addressing climate change” (Topics NM 5 and NM 13), “climate change and society” (Topics NM 2 and NM 11), and “climate politics” (Topics NM 6 and NM 10).

Table 2 . Themes, labels, and topics identified by LDA for academic ( n = 9) and news media ( n = 13) corpora.

Figure 4 . Word-topic probability from LDA model in the academic corpus.

Figure 5 . Word-topic probability from LDA model in the news media corpus.

4. Discussion

This study evaluates the extent of alignment between news media and academic research in their coverage of climate change topics in Chile between 2012 and 2022. By comparing two corpora consisting of 1,261 news articles and 5,024 academic articles, this research sheds light on the similarities, discrepancies, and gaps in the coverage of climate change in Chilean academic and general-interest publications. Our analysis revealed three key findings. Firstly, the number of articles on climate change has increased substantially over the past decade, reflecting a growing interest and urgency surrounding the issue. Secondly, while both news media and academic research cover similar themes, such as climate change indicators, climate change impacts and mitigation and adaptation strategies, the news media provides a wider variety of themes, including climate change and society and climate politics, which are not as commonly explored in academic research. Thirdly, academic literature offers in-depth insights into the ecological consequences of global warming on coastal ecosystems and their inhabitants. In contrast, press media tends to prioritize the tangible and direct impacts, particularly on agriculture and urban health. These disparities not only underscore the differing emphases between news media and academic coverage but also illustrate how news media predominantly focuses on the immediate and visible impacts of climate change events.

4.1. Publications trends over 2012–2022 period

Our study explores the coverage of climate change in Chile by news media and research academia during the 2012–2022 period. We found a significant increase in the number of academic and news media articles published on climate change in Chile over the past decade, indicating growing interest and urgency surrounding the issue ( Figure 3 ). The rise in Chilean literature suggests an increased interest by the scientific community in understanding climate change in Chile, which is crucial for understanding global environmental changes and their impacts on natural, social, political, and economic systems. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that have mapped the evolution of climate change science worldwide ( Klingelhöfer et al., 2020 ; Nalau and Verrall, 2021 ; Reisch et al., 2021 ; Rocque et al., 2021 ). The media coverage of climate change in Chile also increased significantly since 2012, reaching a peak during 2019 before decreasing sharply in 2020 and increasing again thereafter. In 2019, the peak coincided with the climate summit (COP 25) held by Chile, generating great interest among civil society, scientists, and the private sector to share their plans for mitigating and adapting to climate change ( Hjerpe and Linnér, 2010 ). This event occurred at the same time as the #FridaysForFuture campaign, which mobilized an unprecedented number of youths worldwide to join the climate movement, including Chile ( Fisher, 2019 ). The campaign was instrumental not only for its potential impact on policy but also for raising public awareness about climate change and promoting action to address it. However, the media landscape experienced a notable shift in priorities due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic brought about unprecedented challenges and uncertainties, leading to changes in media coverage patterns and public attention. News media had to allocate significant resources to reporting on the pandemic, including public health information, policy responses, and updates on the spread of the virus ( Krawczyk et al., 2021 ; Mach et al., 2021 ). This shift in media priorities affected the extent and prominence of climate change coverage. Consequently, the media coverage of climate change in Chile experienced a temporary decline in 2020. However, as the world gradually adapted to the ongoing pandemic, news media resumed their coverage of climate change, and the topic regained attention. Additionally, the upcoming international conferences, such as COP 26 in England (2021) and COP 27 in Egypt (2022), may have contributed to the increased media coverage observed since 2021, as these events serve as key moments to discuss global climate action.

4.2. LDA topic modeling

Using LDA topic analysis, we found that both academic and news media articles covered three of the five evaluated themes—“climate change indicators”, “climate change impacts”, and “addressing climate change”—as shown in Table 2 and Figures 4 , 5 . The themes “climate change and society” and “climate politics” were covered by news media but has been relatively underexplored in academic research.

4.2.1. Climate change indicators

Both corpora shared a common focus on droughts and precipitations as key climate change indicators. Academic studies covered extreme precipitation and drought (Topic A 2), as well as precipitation patterns in the Andean region (Topic A 4). Similarly, news media concentrated on drought and precipitation patterns in central Chile (Topic NM 9). Research by Chilean scientists shows that since 2010, the country has witnessed a significant increase in drought intensity and frequency, accompanied by a sharp reduction in precipitation ( Garreaud et al., 2020 ; González-Reyes et al., 2023 ). The resulting prolonged drought has caused acute water stress, food insecurity, loss of livelihoods, and severe biodiversity impacts, particularly in the central region. The shared focus reflects the concern for the tangible and urgent impacts of the mega-drought experienced by Chile over the last decade ( De la Barrera et al., 2018 ; Sarricolea et al., 2020 ; Alvarez-Garreton et al., 2021 ). Thus, the alignment in attention to these issues highlights the pressing nature of the topic in Chile's context.

Moreover, the academic corpus focuses on climate change scenarios scenarios (Topic A 3) related to precipitation patterns. This indicates a strong emphasis on understanding the potential impacts of climate change on rainfall patterns and hydrological systems. On the other hand, the news media corpus predominantly focuses on indicators and trends (Topic NM 1) related to financial aspects, such as countries' expenditures, economic programs over the last decade, and historical perspectives on the planet. Although the focus of the two corpora differs in terms of temporal perspective, both share the overarching objective of understanding climate change and its indicators. The academic corpus with its emphasis on scenarios offers valuable insights into long-term projections and the potential consequences of climate change. Meanwhile, the news media corpus, with its focus on indicators and trends, serves to inform the public about the immediate impacts of climate change. By examining these complementary approaches, a more holistic understanding of climate change and its multifaceted nature can be obtained, incorporating both long-term projections and current reality.

Interestingly, news media coverage of climate change impacts extends beyond droughts and precipitation scenarios, encompassing a wide range of issues such as melting ice, sea-level rise, urban flooding, heatwaves, and fires, which have become particularly problematic in Chile and other countries, notably Europe (Topic NM 4 and 7). Heatwaves have been increasingly frequent and intense, resulting in record-breaking high temperatures across, Chile ( Piticar, 2018 ; Suli et al., 2023 ), Europe ( Xu et al., 2020 ; Becker et al., 2022 ; Lhotka and Kyselý, 2022 ) and worldwide. These episodes result in elevated mortality rates, particularly among vulnerable populations, and the amplification of other health-related risks ( An der Heiden et al., 2020 ; Błazejczyk et al., 2022 ). Fires, fueled by warmer and drier conditions, have also received considerable attention in news media. The incidence of wildfires has risen substantially, causing significant ecological damage, property destruction, and threats to human wellbeing ( Wong-Parodi, 2020 ; Hertelendy et al., 2021 ). Fires have been a significant concern in Chile between 2015 and 2022, accounting for 36% of the total burnt area from 1985 to 2022 ( Ruffault et al., 2018 ; CONAF, 2022 ; Varga et al., 2022 ). These fires have resulted in the destruction of thousands of hectares of land, vital ecosystems, and significant air pollution, all of which have adverse effects on human health. This broader coverage aligns with academic research findings that emphasize the devastating effects of climate change events on the environment, local communities, economy, welfare, and health in Chile and elsewhere ( Piticar, 2018 ; Suli et al., 2023 ). The news media serves a pivotal role in disseminating information about these climate change impacts, effectively highlighting their far-reaching consequences. Furthermore, these examples shed light on the differing emphases between news media and academic coverage, with news media giving considerable attention to the immediate and visible impacts of climate change events. This approach serves to raise awareness and engage the public in comprehending and addressing these pressing challenges.

4.2.2. Climate change impacts

The analysis reveals that academic literature predominantly concentrates on the impacts of global warming on coastal organisms (Topics A 9). Similarly, the population response of coastal species is a major research focus within academia, examining the implications of climate change on species' survival, reproductive success, and migration patterns (Topics A 7). Changes in oceans, such as temperature increase, sea level rise, and acidification, have had wide-ranging biological implications ( Dewitte et al., 2021 ; Navarrete et al., 2022 ), and recent studies have shown that marine organisms can adapt or acclimate to these changes ( Navarro et al., 2016 ; Ramajo et al., 2019 ; Fernandez et al., 2021 ; Lardies et al., 2021 ; Vargas et al., 2022 ). For instance, Navarro et al. (2020) examined the effects of ocean warming and acidification on juvenile Chilean oysters ( Ostrea chilensis ), inhabiting coastal and estuarine areas of the mid to high latitudes of southern Chile. Silva et al. (2016) investigated the impacts of projected sea surface temperature on habitat suitability and geographic distribution of anchovy ( Engraulis ringens ) due to climate change in the coastal areas off Chile, an important commercial fishery resource in Chile. Most of these species are commercially important and provide food and livelihoods for local communities. The future impacts of climate change on marine biodiversity in Chile are uncertain but could be severe if current trends persist ( Du Pontavice et al., 2020 ). Additionally, a considerable amount of academic research revolves around environmental impact and risk assessment (Topics A 9), which reflects the growing concern over the susceptibility of human and natural systems to climate change impacts in Chile. Vulnerability and risk assessment can help identify populations, regions, and sectors that are most susceptible to the current and future impacts of climate change ( Urquiza et al., 2021 ). Addressing these vulnerabilities can inform decision-making processes and support the development of effective policies and adaptation strategies ( Gandini et al., 2021 ; Simpson et al., 2021 ).

In contrast, news media predominantly highlights the significant impacts of climate change on Chilean agriculture and ecosystem services (Topic NM 8) ( Fernández et al., 2019 ). Extreme weather events, such as heatwaves and droughts, have resulted in significant alterations in the timing and quantity of rainfall. These changes, in turn, have led to notable shifts in soil moisture levels and water availability for crop cultivation. These events have also impacted soil fertility, crop yields, and farm infrastructure, as well as pollination services provided by insects, such as bees, which are critical for fruit and vegetable production ( Gajardo-Rojas et al., 2022 ). By emphasizing this interconnectedness, news media can help people understand the significant economic, social, and food security impacts of climate change on the country's agricultural sector ( Muluneh, 2021 ). Furthermore, news articles often focus on the health impacts of climate change on urban populations (Topic NM 12), such as the increased prevalence of heat-related illnesses, air pollution-related respiratory diseases, and the spread of vector-borne diseases in cities ( Bell et al., 2008 ; Oyarzún et al., 2021 ).

These disparities between academic literature and news media highlight the communication gap between scientific research and mainstream discourse on climate change impacts in Chile. While academia provides detailed insights into the ecological consequences of global warming on coastal ecosystems and their inhabitants, the news media places more emphasis on tangible and direct impacts, such as those on agriculture and urban health. Bridging this gap between academia and news media is crucial for enhancing public awareness and understanding of the comprehensive range of climate change impacts, ultimately supporting informed decision-making and sustainable action in response to this urgent global issue.

4.2.3. Adressing climate change

An alignment between academic literature and news media can be observed in their shared focus on adaptation efforts and mitigation strategies. Academic literature extensively examines the role of mitigation and adaptation in the energy sector (Topic A 1), emphasizing the importance of diversifying energy sources, developing and implementing renewable energy sources, and energy efficiency to reduce GHG emissions and provide cost-effective mitigation and adaptation benefits to households and businesses ( Nasirov et al., 2019 ; Pamparana et al., 2019 ; Kairies-Alvarado et al., 2021 ; Martinez-Soto et al., 2021 ; Raihan, 2023 ). This aligns with the coverage in news media, which highlights the transition toward low carbon energy systems (Topic NM 5), reflecting policy agendas in many countries, including Chile, where the energy sector is the largest contributor to GHG emissions ( Álamos et al., 2022 ; Labarca et al., 2023 ). The transition to a more sustainable energy system in Chile has been promoted through the implementation of renewable energy production and energy efficiency ( Simsek et al., 2019 , 2020 ; Babonneau et al., 2021 ; Osorio-Aravena et al., 2021 ; Ferrada et al., 2022 ). These findings are in line with those of Lyytimäki (2018) , who found that news media created a highly positive narrative of renewable energies as an environmentally friendly solution to GHG emissions.

However, disparities between academic literature and news media coverage are apparent. While both sources recognize the significance of these measures, academic literature provides more comprehensive coverage than news media. Academic literature places significant emphasis on forest carbon management, acknowledging the crucial role of forests in carbon sequestration (Topic A 5), and climate change mitigation. This involves implementing forest conservation, reforestation, and afforestation practices to increase carbon sequestration in forest biomass and soil, thereby reducing GHG emissions Additionally, academic literature extensively addresses agriculture-water management (Topic A 6), emphasizing the importance of sustainable agricultural practices and efficient water resource management in response to changing climate conditions. Relevant mitigation and adaptation strategies for agriculture, such as improving water use efficiency, adopting irrigation technologies, and modifying crop choices, have been identified in academic research ( Novoa et al., 2019 ; Jordán and Speelman, 2020 ; Zúñiga et al., 2021 ). In contrast, news media coverage is more limited in these areas, focusing more narrowly on the transition toward low carbon energy systems (Topic NM 5), and general adaptation efforts and mitigation strategies (Topic NM 13). Despite this, news media plays a vital role in climate change communication by highlighting various actions that can be taken to effectively mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change, which can help promote the adoption of sustainable solutions.

4.2.4. Climate change and society

Our analysis reveals an interesting pattern: the theme of “climate change and society” is covered by news media but has been relatively underexplored in academic research. In news media coverage, the theme of society and sustainable development (Topic NM 2) takes center stage, focusing on dimensions such as economy, technology, social, and environment. Additionally, news media pays significant attention to climate action (Topic NM 11), exemplified by movements like “Fridays for Future” and speeches by climate activist Greta Thunberg during international climate conferences such as COP.

This media coverage plays a vital role in highlighting contingent events and showcasing the direct and indirect impacts of climate change on people's daily lives on both local and global scales. However, it is notable that the theme of “climate change and society” lacks adequate representation in the scientific literature.

Understanding the societal implications of climate change is of paramount importance for all stakeholders, including policymakers, civil society organizations, and individuals. The scientific exploration of this topic can provide valuable insights into effective and equitable adaptation and mitigation strategies. Consequently, there is a pressing need to develop further research on this topic, bridging the gap between news media coverage and scientific inquiry. By expanding our understanding of the societal dimensions of climate change in the academic literature, we can better inform evidence-based decision-making, foster collective action, and ultimately contribute to a more sustainable future.

4.2.5. Climate politics

Climate politics is another topic covered by news media underexplored in academic. This theme has included topics such international conferences and commitments (Topic NM 3), IPCC Reports (Topic NM 6) and Chilean climate change framework law (Topic NM 10). The Climate Change Framework Law, is a recent important policy instrument for addressing climate change, as it aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change ( Madariaga Gómez de Cuenca, 2021 ). The IPCC report, on the other hand, is a crucial scientific report that provides a comprehensive assessment of the state of knowledge on climate change, its causes, impacts, and future risks ( Pörtner et al., 2019 ). IPCC report coverage in the news media is vital for the understanding of climate change in Chile and worldwide, as they inform the public about the latest developments in climate policy and the scientific understanding of climate change. The coverage of these topics in the news media is important for society's understanding of climate change, both in Chile and worldwide, as it highlights the importance of political will and action in tackling climate change at local, national, and global levels. The relatively low coverage of these themes in academic research, however, suggests the need for more interdisciplinary research on the social and political dimensions of climate change.

4.3. Analyzing news media and academic research

Our study focused on assessing the alignment between climate change coverage in news media and academic research in Chile, revealing significant gaps in the framing of climate change between these two domains. Academic research and media coverage of climate change often focus on different aspects and utilize distinct methodologies. Academic sources offer rigorous scientific investigations, providing in-depth analysis and evidence-based insights into the complexities of climate change ( Cook, 2019 ; Farrell et al., 2019 ; Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021 ). In contrast, media sources serve as a bridge between scientific findings and public understanding, shaping public opinion and influencing societal actions ( Boykoff, 2009 ; Drews and Van den Bergh, 2016 ; Boykoff and Luedecke, 2017 ; Stecula and Merkley, 2019 ; Merkley, 2020 ; McAllister et al., 2021 ; Okoliko and de Wit, 2023 ). The complementary nature of academic and media sources allows for a more comprehensive communication and understanding of climate change ( Goldstein et al., 2020 ; Lewandowsky, 2021 ). Through analyzing both academic and media sources, discrepancies and gaps in climate change coverage can be identified, uncovering biases and insufficient attention to certain aspects. This analysis significantly enhances public understanding by facilitating the development of targeted communication strategies that bridge these gaps, ultimately promoting informed public debates and driving effective actions. However, it is crucial to recognize that the level of media influence on public opinion depends on the level of audience engagement with climate change discourse ( Wonneberger et al., 2020 ). Consequently, aligning academic and media coverage becomes even more essential as it enables a more accurate and balanced portrayal of climate change, thereby facilitating the implementation of necessary policies and practices to address this pressing global concern. Our findings have important implications for future research and climate communication in Chile, suggesting the need for increased attention to the challenging dimensions of climate change, such as the social dynamics and political factors associated with this global issue.

4.4. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. Firstly, the academic corpus only included articles published in English, while the news media corpus only included articles published in Spanish. As a result, topics' keywords had to be translated into English for comparison between corpora, which could have an effect on the results. Secondly, we selected eight Chilean electronic news media sources with high readership and free accessibility without subscription fees; however, future studies should consider including other paid subscription news media as well. Thirdly, our research does not take into account other mass media platforms that can provide information about climate change ( Tandoc and Eng, 2017 ; Becken et al., 2022 ). Future research could explore this topic further. Lastly, this study analyzed two corpora inherently different in terms of their coverage; news media tends to cover climate change from an international perspective, while academia focuses on a more local or regional level. These limitations do not diminish the significance of our findings. Our study highlights the need for better communication and dissemination of scientific findings to the general public. The findings of this study are not only relevant to Chile but also have global implications in addressing the pressing issue of climate change. It is crucial to bridge the gap between academic research and news media coverage to promote effective solutions for tackling this issue.

5. Conclusion

Through the application of text-mining, web-scraping methods, and topic-modeling techniques to an academic and news media corpus, this study has yielded valuable insights into the similarities, discrepancies, and gaps in the coverage of climate change in Chilean academic and general-interest publications. By identifying and analyzing these patterns, our research contributes to a deeper understanding of climate change coverage in Chile, providing relevant evidence that bridges the communication gap between scientific research and mainstream discourse. The integration of academic and media sources in this study has revealed their complementary nature, facilitating a more comprehensive communication and understanding of climate change. This interdisciplinary approach expands our perspective, allowing us to appreciate the multifaceted aspects associated with climate change more holistically. This study underscores the importance of considering both academic and media sources when addressing climate change. By combining the rigorous analysis of scientific research with the broader reach of media coverage, it's possible to promote a more informed and engaged public discourse on climate change.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary material , further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PC and RQ contributed to conception and design of the study. PC organized the database, retrieved the information, performed the analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank to Dr. Christos Joannides, Fredy Núñez, and Manuel Valenzuela for their feedback on previous versions of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1226432/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1. Academic and news media corpora analyzed in this study.

Abram, N. J., Henley, B. J., Sen Gupta, A., Lippmann, T. J., Clarke, H., Dowdy, A. J., et al. (2021). Connections of climate change and variability to large and extreme forest fires in southeast Australia. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 8. doi: 10.1038/s43247-020-00065-8

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Abubakar, I. R., and Dano, U. L. (2020). Sustainable urban planning strategies for mitigating climate change in Saudi Arabia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 22, 5129–5152. doi: 10.1007/s10668-019-00417-1

Álamos, N., Huneeus, N., Opazo, M., Osses, M., Puja, S., Pantoja, N., et al. (2022). High-resolution inventory of atmospheric emissions from transport, industrial, energy, mining and residential activities in Chile. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 361–379. doi: 10.5194/essd-14-361-2022

Albagli, S., and Iwama, A. Y. (2022). Citizen science and the right to research: Building local knowledge of climate change impacts. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 9, 39. doi: 10.1057/s41599-022-01040-8

Alvarez-Garreton, C., Boisier, J. P., Garreaud, R., Seibert, J., and Vis, M. (2021). Progressive water deficits during multiyear droughts in basins with long hydrological memory in Chile. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 429–446. doi: 10.5194/hess-25-429-2021

An der Heiden, M., Muthers, S., Niemann, H., Buchholz, U., Grabenhenrich, L., and Matzarakis, A. (2020). Heat-related mortality: an analysis of the impact of heatwaves in Germany between 1992 and 2017. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int. 117, 603–609. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0603

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Anupriya, P., and Karpagavalli, S. (2015). LDA based topic modeling of journal abstracts. Int. Conf. Adv. Comput. Commun. Syst. 2015:1–5. doi: 10.1109/ICACCS.2015.7324058

Araya-Osses, D., Casanueva, A., Román-Figueroa, C., Uribe, J. M., and Paneque, M. (2020). Climate change projections of temperature and precipitation in Chile based on statistical downscaling. Clim. Dyn. 54, 4309–4330. doi: 10.1007/s00382-020-05231-4

Babonneau, F., Barrera, J., and Toledo, J. (2021). Decarbonizing the Chilean electric power system: a prospective analysis of alternative carbon emissions policies. Energies 14, 4768. doi: 10.3390/en14164768

Barkemeyer, R., Figge, F., Hoepner, A., Holt, D., Kraak, J. M., and Yu, P. S. (2017). Media coverage of climate change: an international comparison. Environ. Plann. C Polit. Space 35, 1029–1054. doi: 10.1177/0263774X16680818

Becken, S., Stantic, B., Chen, J., and Connolly, R. M. (2022). Twitter conversations reveal issue salience of aviation in the broader context of climate change. J. Air Transp. Manag. 98, 102157. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2021.102157

Becker, F. N., Fink, A. H., Bissolli, P., and Pinto, J. G. (2022). Towards a more comprehensive assessment of the intensity of historical European heat waves (1979–2019). Atmosph. Sci. Lett. 23, e1120. doi: 10.1002/asl.1120

Bell, M. L., O'neill, M. S., Ranjit, N., Borja-Aburto, V. H., Cifuentes, L. A., and Gouveia, N. C. (2008). Vulnerability to heat-related mortality in Latin America: a case-crossover study in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Santiago, Chile and Mexico City, Mexico. Int. J. Epidemiol. 37, 796–804. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn094

Benoit, K., Watanabe, K., Wang, H., Nulty, P., Obeng, A., Müller, S., et al. (2018). quanteda: an R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 774–774. doi: 10.21105/joss.00774

Berrang-Ford, L., Pearce, T., and Ford, J. D. (2015). Systematic review approaches for climate change adaptation research. Reg. Environ. Change 15, 755–769. doi: 10.1007/s10113-014-0708-7

Błazejczyk, K., Twardosz, R., Wałach, P., Czarnecka, K., and Błazejczyk, A. (2022). Heat strain and mortality effects of prolonged central European heat wave—an example of June 2019 in Poland. Int. J. Biometeorol. 66, 149–161. doi: 10.1007/s00484-021-02202-0

Blei, D. M. (2012). Probabilistic topic models. Commun. ACM 55, 77–84. doi: 10.1145/2133806.2133826

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., and Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 3, 993−1022.

Google Scholar

Bohr, J. (2020). Reporting on climate change: a computational analysis of US newspapers and sources of bias, 1997–2017. Global Environ. Change 61, 102038. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102038

Boykoff, M. T. (2009). We speak for the trees: Media reporting on the environment. Ann. Rev. Environ. Resour. 34, 431–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.environ.051308.084254

Bozkurt, D., Rojas, M., Boisier, J. P., and Valdivieso, J. (2017). Climate change impacts on hydroclimatic regimes and extremes over Andean basins in central Chile. Hydrol Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 1–29. doi: 10.5194/hess-2016-690

Cao, J., Xia, T., Li, J., Zhang, Y., and Tang, S. (2009). A density-based method for adaptive LDA model selection. Neurocomputing 72, 1775–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2008.06.011

Cianconi, P., Betr,ò, S., and Janiri, L. (2020). The impact of climate change on mental health: a systematic descriptive review. Front. Psychiatry 11, 74. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

CONAF (2022). Corporación Nacional Forestal: Estadí sticas históricas . Available online at: https://www.conaf.cl/incendios-forestales/incendios-forestales-en-chile/estadisticas-historicas/ (accessed February 5, 2023).

Cook, B. I., Mankin, J. S., Marvel, K., Williams, A. P., Smerdon, J. E., and Anchukaitis, K. J. (2020). Twenty-first century drought projections in the CMIP6 forcing scenarios. Earths Fut. 8, e2019EF001461. doi: 10.1029/2019EF001461

Cook, J. (2019). “Understanding and countering misinformation about climate change,” in Handbook of Research on Deception, Fake News, and Misinformation , eds I. Chiluwa and S. Samoilenko (Hershey, PA: IGI-Global).

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Corbett, J. B. (2015). Media power and climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 288–290. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2592

De la Barrera, F., Barraza, F., Favier, P., Ruiz, V., and Quense, J. (2018). Megafires in Chile 2017: monitoring multiscale environmental impacts of burned ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 637, 1526–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.119

Deveaud, R., SanJuan, E., and Bellot, P. (2014). Accurate and effective latent concept modeling for ad hoc information retrieval. Doc. Num. 17, 61–84. doi: 10.3166/dn.17.1.61-84

Dewitte, B., Conejero, C., Ramos, M., Bravo, L., Garcon, V., Parada, C., et al. (2021). Understanding the impact of climate change on the oceanic circulation in the Chilean island ecoregions. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshwater Ecosyst. 31, 232–252. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3506

Diamond, E., Bernauer, T., and Mayer, F. (2020). Does providing scientific information affect climate change and GMO policy preferences of the mass public? Insights from survey experiments in Germany and the United States. Environ. Polit. 29, 1199–1218. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2020.1740547

Díaz, G. (2016). Download Stop Words . Available online at: https://github.com/stopwords-iso/stopwords-es (accessed December 15, 2022).

Doney, S. C., Busch, D. S., Cooley, S. R., and Kroeker, K. J. (2020). The impacts of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and reliant human communities. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 45, 83–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-083019

Dotson, D. M., Jacobson, S. K., Kaid, L. L., and Carlton, J. S. (2012). Media coverage of climate change in Chile: a content analysis of conservative and liberal newspapers. Environ. Commun. J. Nat. Cult. 6, 64–81. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2011.642078

Drews, S., and Van den Bergh, J. C. (2016). What explains public support for climate policies? A review of empirical and experimental studies. Clim. Policy 16, 855–876. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2015.1058240

Du Pontavice, H., Gascuel, D., Reygondeau, G., Maureaud, A., and Cheung, W. W. (2020). Climate change undermines the global functioning of marine food webs. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 1306–1318. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14944