- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

A Guide to Rebuttals in Argumentative Essays

4-minute read

- 27th May 2023

Rebuttals are an essential part of a strong argument. But what are they, exactly, and how can you use them effectively? Read on to find out.

What Is a Rebuttal?

When writing an argumentative essay , there’s always an opposing point of view. You can’t present an argument without the possibility of someone disagreeing.

Sure, you could just focus on your argument and ignore the other perspective, but that weakens your essay. Coming up with possible alternative points of view, or counterarguments, and being prepared to address them, gives you an edge. A rebuttal is your response to these opposing viewpoints.

How Do Rebuttals Work?

With a rebuttal, you can take the fighting power away from any opposition to your idea before they have a chance to attack. For a rebuttal to work, it needs to follow the same formula as the other key points in your essay: it should be researched, developed, and presented with evidence.

Rebuttals in Action

Suppose you’re writing an essay arguing that strawberries are the best fruit. A potential counterargument could be that strawberries don’t work as well in baked goods as other berries do, as they can get soggy and lose some of their flavor. Your rebuttal would state this point and then explain why it’s not valid:

Read on for a few simple steps to formulating an effective rebuttal.

Step 1. Come up with a Counterargument

A strong rebuttal is only possible when there’s a strong counterargument. You may be convinced of your idea but try to place yourself on the other side. Rather than addressing weak opposing views that are easy to fend off, try to come up with the strongest claims that could be made.

In your essay, explain the counterargument and agree with it. That’s right, agree with it – to an extent. State why there’s some truth to it and validate the concerns it presents.

Step 2. Point Out Its Flaws

Now that you’ve presented a counterargument, poke holes in it . To do so, analyze the argument carefully and notice if there are any biases or caveats that weaken it. Looking at the claim that strawberries don’t work well in baked goods, a weakness could be that this argument only applies when strawberries are baked in a pie.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Step 3. Present New Points

Once you reveal the counterargument’s weakness, present a new perspective, and provide supporting evidence to show that your argument is still the correct one. This means providing new points that the opposer may not have considered when presenting their claim.

Offering new ideas that weaken a counterargument makes you come off as authoritative and informed, which will make your readers more likely to agree with you.

Summary: Rebuttals

Rebuttals are essential when presenting an argument. Even if a counterargument is stronger than your point, you can construct an effective rebuttal that stands a chance against it.

We hope this guide helps you to structure and format your argumentative essay . And once you’ve finished writing, send a copy to our expert editors. We’ll ensure perfect grammar, spelling, punctuation, referencing, and more. Try it out for free today!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a rebuttal in an essay.

A rebuttal is a response to a counterargument. It presents the potential counterclaim, discusses why it could be valid, and then explains why the original argument is still correct.

How do you form an effective rebuttal?

To use rebuttals effectively, come up with a strong counterclaim and respectfully point out its weaknesses. Then present new ideas that fill those gaps and strengthen your point.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- How It Works

- Prices & Discounts

A Student's Guide: Crafting an Effective Rebuttal in Argumentative Essays

Table of contents

Picture this – you're in the middle of a heated debate with your classmate. You've spent minutes passionately laying out your argument, backing it up with well-researched facts and statistics, and you think you've got it in the bag. But then, your classmate fires back with a rebuttal that leaves you stumped, and you realize your argument wasn't as bulletproof as you thought.

This scenario could easily translate to the world of writing – specifically, to argumentative essays. Just as in a real-life debate, your arguments in an essay need to stand up to scrutiny, and that's where the concept of a rebuttal comes into play.

In this blog post, we will unpack the notion of a rebuttal in an argumentative essay, delve into its importance, and show you how to write one effectively. We will provide you with step-by-step guidance, illustrate with examples, and give you expert tips to enhance your essay writing skills. So, get ready to strengthen your arguments and make your essays more compelling than ever before!

Understanding the Concept of a Rebuttal

In the world of debates and argumentative essays, a rebuttal is your opportunity to counter an opposing argument. It's your chance to present evidence and reasoning that discredits the counter-argument, thereby strengthening your stance.

Let's simplify this with an example . Imagine you're writing an argumentative essay on why school uniforms should be mandatory. One common opposing argument could be that uniforms curb individuality. Your rebuttal to this could argue that uniforms do not stifle individuality but promote equality, and help reduce distractions, thus creating a better learning environment.

Understanding rebuttals and their structure is the first step towards integrating them into your argumentative essays effectively. This process will add depth to your argument and demonstrate your ability to consider different perspectives, making your essay robust and thought-provoking.

Let's get into the nitty-gritty of how to structure your rebuttals and make them as effective as possible in the following sections.

The Structural Anatomy of a Rebuttal: How It Fits into Your Argumentative Essay

The potency of an argumentative essay lies in its structure, and a rebuttal is an integral part of this structure. It ensures that your argument remains balanced and considers opposing viewpoints. So, how does a rebuttal fit into an argumentative essay? Where does it go?

In a traditional argumentative essay structure, the rebuttal generally follows your argument and precedes the conclusion. Here's a simple breakdown:

Introduction : The opening segment where you introduce the topic and your thesis statement.

Your Argument : The body of your essay where you present your arguments in support of your thesis.

Rebuttal or Counterargument : Here's where you present the opposing arguments and your rebuttals against them.

Conclusion : The final segment where you wrap up your argument, reaffirming your thesis statement.

Understanding the placement of the rebuttal within your essay will help you maintain a logical flow in your writing, ensuring that your readers can follow your arguments and counterarguments seamlessly. Let's delve deeper into the construction of a rebuttal in the next section.

Components of a Persuasive Rebuttal: Breaking It Down

A well-crafted rebuttal can significantly fortify your argumentative essay. However, the key to a persuasive rebuttal lies in its construction. Let's break down the components of an effective rebuttal:

Recognize the Opposing Argument : Begin by acknowledging the opposing point of view. This helps you establish credibility with your readers and shows them that you're not dismissing other perspectives.

Refute the Opposing Argument : Now, address why you believe the opposing viewpoint is incorrect or flawed. Use facts, logic, or reasoning to dismantle the counter-argument.

Support Your Rebuttal : Provide evidence, examples, or facts that support your rebuttal. This not only strengthens your argument but also adds credibility to your stance.

Transition to the Next Point : Finally, provide a smooth transition to the next part of your essay. This could be another argument in favor of your thesis or your conclusion, depending on the structure of your essay.

Each of these components is a crucial building block for a persuasive rebuttal. By structuring your rebuttal correctly, you can effectively refute opposing arguments and fortify your own stance. Let's move to some practical applications of these components in the next section.

Building Your Rebuttal: A Step-by-Step Guide

Writing a persuasive rebuttal may seem challenging, especially if you're new to argumentative essays. However, it's less daunting when broken down into smaller steps. Here's a practical step-by-step guide on how to construct your rebuttal:

Step 1: Identify the Counter-Arguments

The first step is to identify the potential counter-arguments that could be made against your thesis. This requires you to put yourself in your opposition's shoes and think critically about your own arguments.

Step 2: Choose the Strongest Counter-Argument

It's not practical or necessary to respond to every potential counter-argument. Instead, choose the most significant one(s) that, if left unaddressed, could undermine your argument.

Step 3: Research and Collect Evidence

Once you've chosen a counter-argument to rebut, it's time to research. Find facts, statistics, or examples that clearly refute the counter-argument. Remember, the stronger your evidence, the more persuasive your rebuttal will be.

Step 4: Write the Rebuttal

Using the components we outlined earlier, write your rebuttal. Begin by acknowledging the opposing argument, refute it using your evidence, and then transition smoothly to your next point.

Step 5: Review and Refine

Finally, review your rebuttal. Check for logical consistency, clarity, and strength of evidence. Refine as necessary to ensure your rebuttal is as persuasive and robust as possible.

Remember, practice makes perfect. The more you practice writing rebuttals, the more comfortable you'll become at identifying strong counter-arguments and refuting them effectively. Let's illustrate these steps with a practical example in the next section.

Practical Example: Constructing a Rebuttal

In this section, we'll apply the steps discussed above to construct a rebuttal. We'll use a hypothetical argumentative essay topic: "Should schools switch to a four-day school week?"

Thesis Statement : You are arguing in favor of a four-day school week, citing reasons such as improved student mental health, reduced operational costs for schools, and enhanced quality of education due to extended hours.

Identify Counter-Arguments : The opposition could argue that a four-day school week might lead to childcare issues for working parents or that the extended hours each day could lead to student burnout.

Choose the Strongest Counter-Argument : The point about childcare issues for working parents is potentially a significant concern that needs addressing.

Research and Collect Evidence : Research reveals that many community organizations offer affordable after-school programs. Additionally, some schools adopting a four-day week have offered optional fifth-day enrichment programs.

Write the Rebuttal : "While it's valid to consider the childcare challenges a four-day school week could impose on working parents, many community organizations provide affordable after-school programs. Moreover, some schools that have already adopted the four-day week offer an optional fifth-day enrichment program, demonstrating that viable solutions exist."

Review and Refine: Re-read your rebuttal, refine for clarity and impact, and ensure it integrates smoothly into your argument.

This is a simplified example, but it serves to illustrate the process of crafting a rebuttal. Let's move on to look at two full-length examples to further demonstrate effective rebuttals.

Case Study: Effective vs. Ineffective Rebuttal

Now that we've covered the theoretical and practical aspects, let's delve into two case studies. These examples will compare an effective rebuttal versus an ineffective one, so you can better understand what separates a compelling argument from a weak one.

Example 1: "Homework is unnecessary."

Ineffective Rebuttal : "I don't agree with you. Homework is important because it's part of the curriculum and it helps students study."

Effective Rebuttal : "Your concern about the overuse of homework is valid, considering the amount of stress students face today. However, research shows that homework, when thoughtfully assigned and not overused, can reinforce classroom learning, provide students with valuable time management skills, and help teachers evaluate student understanding."

The effective rebuttal acknowledges the opposing argument, uses evidence-backed reasoning, and strengthens the argument by showing the value of homework in the larger context of learning.

Example 2: "Standardized testing doesn't accurately measure student intelligence."

Ineffective Rebuttal : "I think you're wrong. Standardized tests have been around for a long time, and they wouldn't use them if they didn't work."

Effective Rebuttal : "Indeed, the limitations of standardized testing, such as potential cultural bias or the inability to measure creativity, are recognized issues. However, these tests are a tool—albeit an imperfect one—for comparing student achievement across regions and identifying areas where curriculum and teaching methods might need improvement. More comprehensive methods, blending standardized testing with other assessment forms, are promising approaches for future development."

The effective rebuttal in this instance acknowledges the flaws in standardized testing but highlights its role as a tool for larger educational system assessments and improvements.

Remember, an effective rebuttal is respectful, acknowledges the opposing viewpoint, provides strong counter-arguments, and integrates evidence. With practice, you will get better at crafting compelling rebuttals. In the next section, we will discuss some additional strategies to improve your rebuttal skills.

Final Thoughts

The art of constructing a compelling rebuttal is a crucial skill in argumentative essay writing. It's not just about presenting your own views but also about understanding, acknowledging, and effectively countering the opposing viewpoint. This makes your argument more robust and balanced, increasing its persuasive power.

However, developing this skill requires patience, practice, and a thoughtful approach. The techniques we've discussed in this guide can serve as a starting point, but remember that every argument is unique, and flexibility is key.

Always be ready to adapt and refine your rebuttal strategy based on the particular argument and evidence you're dealing with. And don't shy away from seeking feedback and learning from others - this is how we grow as writers and thinkers.

But remember, you're not alone on this journey. If you're ever struggling with writing your argumentative essay or crafting that perfect rebuttal, we're here to help. Our experienced writers at Writers Per Hour are well-versed in the nuances of argumentative writing and can assist you in achieving your academic goals.

So don't stress - embrace the challenge of argumentative writing, keep refining your skills, and remember that help is just a click away! In the next section, you'll find additional resources to continue learning and growing in your argumentative writing journey.

Additional Resources

As you continue to learn and develop your argumentative writing skills, having access to additional resources can be immensely beneficial. Here are some that you might find helpful:

Posts from Writers Per Hour Blog :

- How Significant Are Opposing Points of View in an Argument

- Writing a Hook for an Argumentative Essay

- Strong Argumentative Essay Topic Ideas

- Writing an Introduction for Your Argumentative Essay

External Resources :

- University of California Berkeley Student Learning Center: Writing Argumentative Essays

- Stanford Online Writing Center: Techniques of Persuasive Argument

Remember, mastery in argumentative writing doesn't happen overnight – it's a journey that requires patience, practice, and persistence. But with the right guidance and resources, you're already on the right path. And, of course, if you ever need assistance, our argumentative essay writing service services are always ready to help you reach your academic goals. Happy writing!

Share this article

Achieve Academic Success with Expert Assistance!

Crafted from Scratch for You.

Ensuring Your Work’s Originality.

Transform Your Draft into Excellence.

Perfecting Your Paper’s Grammar, Style, and Format (APA, MLA, etc.).

Calculate the cost of your paper

Get ideas for your essay

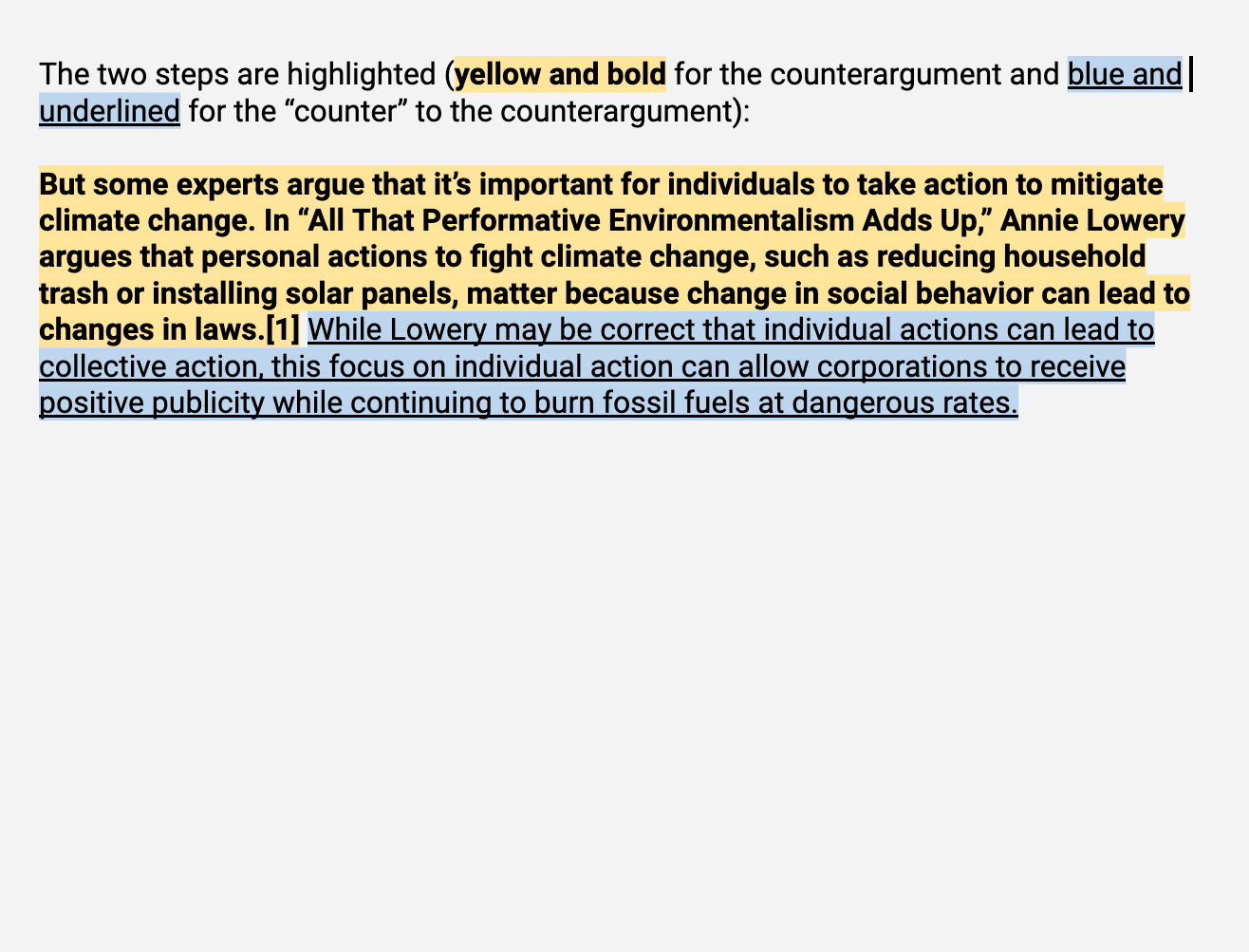

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Rebuttals and Refutations

introduction to rebuttal and refutation of counterargument.

An integral part of composing a strong argument is including a counterargument. This can be difficult, especially if a writer is arguing for a position s/he already agrees with. In such cases, writers can sometimes make good points to support their stances; however, their arguments are vulnerable unless they anticipate and address counterarguments. When a writer does this, it is often referred to as rebuttal or refutation. Some scholars of rhetoric differentiate the two words in terms of whether you can actually disprove a claim or just argue against it; however, in this section, we will use the terms as basically interchangeable to help get you more used to their function in argument. When writers are able to skillfully rebut or refute a view that runs counter to their claims, it strengthens their work. Rebuttal and refutation are common in all types of arguments, including academic arguments. As you complete more advanced work in college, you will be expected to address counterargument often. And while you might not always need to or be able to prove that other points of view are wrong, you may at least need to try to argue against them.

Formula for Refutation and Rebuttal

Though writers may handle rebuttal and refutation in different ways, there is a formula for success in academic argument. Here are the key parts of that formula:

Accurately represent opposing viewpoints

If you don’t accurately and thoroughly represent opposing viewpoints in your own writing, some of your potential audience will automatically be turned off. Good rebuttal and refutation begins with a solid understanding of all possible points of view on your topic. That may mean you even need to acknowledge and accommodate opposing points of view. Acknowledging other views shows you are aware of ideas that run counter to your claims. You will almost always be expected to at least acknowledge such views in your work. You may also, though, need to accommodate opposing views, especially if many people see them as reasonable. If, for example, you were writing a piece arguing that students should take a gap year between high school and college, it would benefit your work to acknowledge that a gap year isn’t realistic for or even desired by all students. You may further accommodate this other view by explaining how some students may thrive in the structure that school provides and would gain by going directly from high school to college. Remember that even if you cannot prove positions that counter your own are wrong, you can still use rebuttal and refutation to show why they might be problematic, flawed, or just not as good as another possible position for some people.

Use a respectful, non-incendiary tone

It doesn’t help the writer’s cause to offend, upset, or alienate potential readers, even those who hold differing views. Treating all potential readers with respect and avoiding words or phrases that belittle people and/or their views will help you get your points across more effectively. For example, if you are writing a paper on why America would benefit from a third viable major political party, it will not help your cause to write that “Republicans are dumb, and Democrats are whiny.” First, those claims are too general. But even if they weren’t, they won’t help your cause. If you choose to break down the perceived problems with members of political parties, you must do so in a way that is as respectful as possible. Calling someone a name or insulting them (directly or indirectly) is very rarely a successful strategy in argument.

Use reliable information in your rebuttal/refutation

Always be sure to carefully check the ideas or claims you make in rebutting a counterargument. The brain is not an infallible computer, and there are instances when we think we know information is accurate but it isn’t. Sometimes we know a lot about a particular subject but we get information confused or time has changed things a bit. Additionally, we may be tempted to use a source that backs up our ideas perfectly, but it might not be the most reputable, credible, or up-to-date place for information. Don’t assume you just have all of the information to shoot down counterarguments. Use your knowledge, but also do thorough research, double- and triple-check information, and look for sources that are likely to carry weight with readers. For example, it is widely assumed that bulls are attracted to the color red; however, in reality, bulls are colorblind, so what many people assume as fact is incorrect. Be thorough so you have confidence in your claims when you are rebutting/refuting and likewise when you are attempting to prevent yourself from being open to rebuttal/refutation.

Use qualifying words when applicable

Qualifying words are terms such as “many,” “most,” “some,” “might,” “rarely,” “doubtful,” “often,” etc. You get the point. These are words that don’t lock you into a claim that could be easily refuted and that can help you more easily rebut counterarguments. For example, if someone says, “Nobody dies of tuberculosis anymore,” we might get the point that it isn’t as common as it used to be. Still, it isn’t an accurate statement, and a more precise way to phrase such a claim would be to qualify it: “Not many people die each year in America from tuberculosis.” You might not always need to use qualifying terms. If you are making a point that is absolute, feel free to make it strongly; however, if there is a need to give your claim more flexibility, use qualifying words to help you.

Now let’s take a look at examples of rebuttal and refutation to further your understanding:

Download the PDF of these examples.

Felix is writing his argument paper on why his university should not have cut funding to the school’s library. His arguable thesis reads as follows: Because Northern State University has a mission statement that includes becoming a Research 1 (R1) institution, full funding should be restored to the library to ensure faculty and students have adequate resources to enhance their research agendas.

Felix has done his research, and he knows that a couple of the main counterarguments are that the school needs funds to renovate the student union and to construct a new building for the Engineering Department. Thus, he can anticipate counterarguments and include them in his paper. While Felix cannot prove beyond doubt that the school should use more funding for the library instead of addressing other needs, he can try to make the case.

Read over Felix’s passage below to see how he strengthens his case, and note the annotations to help you see parts of the formula in action:

Notice how each student has a different goal and approach, yet they both still use parts of the formula to help them accomplish their rhetorical aims.

UNM Core Writing OER Collection Copyright © 2023 by University of New Mexico is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

What is Rebuttal in an Argumentative Essay? (How to Write It)

by Antony W

April 7, 2022

Even if you have the most convincing evidence and reasons to explain your position on an issue, there will still be people in your audience who will not agree with you.

Usually, this creates an opportunity for counterclaims, which requires a response through rebuttal. So what exactly is rebuttal in an argumentative essay?

A rebuttal in an argumentative essay is a response you give to your opponent’s argument to show that the position they currently hold on an issue is wrong. While you agree with their counterargument, you point out the flaws using the strongest piece of evidence to strengthen your position.

To be clear, it’s hard to write an argument on an issue without considering counterclaim and rebuttals in the first place.

If you think about it, debatable topics require a consideration of both sides of an issue, which is why it’s important to learn about counterclaims and rebuttals in argumentative writing.

What is a Counterclaim in an Argument?

To understand why rebuttal comes into play in an argumentative essay, you first have to know what a counterclaim is and why it’s important in writing.

A counterclaim is an argument that an opponent makes to weaken your thesis. In particular, counterarguments try to show why your argument’s claim is wrong and try to propose an alternative to what you stand for.

From a writing standpoint, you have to recognize the counterclaims presented by the opposing side.

In fact, argumentative writing requires you to look at the two sides of an issue even if you’ve already taken a strong stance on it.

There are a number of benefits of including counterarguments in your argumentative essay:

- It shows your instructor that you’ve looked into both sides of the argument and recognize that some readers may not share your views initially.

- You create an opportunity to provide a strong rebuttal to the counterclaims, so readers see them before they finish reading the essay.

- You end up strengthening your writing because the essay turns out more objective than it would without recognizing the counterclaims from the opposing side.

What is Rebuttal in Argumentative Essay?

Your opponent will always look for weaknesses in your argument and try the best they can to show that you’re wrong.

Since you have solid grounds that your stance on an issue is reasonable, truthful, or more meaningful, you have to give a solid response to the opposition.

This is where rebuttal comes in.

In argumentative writing, rebuttal refers to the answer you give directly to an opponent in response to their counterargument. The answer should be a convincing explanation that shows an opponent why and/or how they’re wrong on an issue.

How to Write a Rebuttal Paragraph in Argumentative Essay

Now that you understand the connection between a counterclaim and rebuttal in an argumentative writing, let’s look at some approaches that you can use to refute your opponent’s arguments.

1. Point Out the Errors in the Counterargument

You’ve taken a stance on an issue for a reason, and mostly it’s because you believe yours is the most reasonable position based on the data, statistics, and the information you’ve collected.

Now that there’s a counterargument that tries to challenge your position, you can refute it by mentioning the flaws in it.

It’s best to analyze the counterargument carefully. Doing so will make it easy for you to identify the weaknesses, which you can point out and use the strongest points for rebuttal

2. Give New Points that Contradict the Counterclaims

Imagine yourself in a hall full of debaters. On your left side is an audience that agrees with your arguable claim and on your left is a group of listeners who don’t buy into your argument.

Your opponents in the room are not holding back, especially because they’re constantly raising their hands to question your information.

To win them over in such a situation, you have to play smart by recognizing their stance on the issue but then explaining why they’re wrong.

Now, take a closer look at the structure of an argument . You’ll notice that it features a section for counterclaims, which means you have to address them if your essay must stand out.

Here, it’s ideal to recognize and agree with the counterargument that the opposing side presents. Then, present a new point of view or facts that contradict the arguments.

Doing so will get the opposing side to consider your stance, even if they don’t agree with you entirely.

3. Twist Facts in Favor of Your Argument

Sometimes the other side of the argument may make more sense than yours does. However, that doesn’t mean you have to concede entirely.

You can agree with the other side of the argument, but then twist facts and provide solid evidence to suit your argument.

This strategy can work for just about any topic, including the most complicated or controversial ones that you have never dealt with before.

4. Making an Emotional Plea

Making an emotional plea isn’t a powerful rebuttal strategy, but it can also be a good option to consider.

It’s important to make sure that the emotional appeal you make outweighs the argument that your opponent brings forth.

Given that it’s often the least effective option in most arguments, making an emotional appeal should be a last resort if all the other options fail.

Final Thoughts

As you can see, counterclaims are important in an argumentative essay and there’s more than one way to give your rebuttal.

Whichever approach you use, make sure you use the strongest facts, stats, evidence, or argument to prove that your position on an issue makes more sense that what your opponents currently hold.

Lastly, if you feel like your essay topic is complicated and you have only a few hours to complete the assignment, you can get in touch with Help for Assessment and we’ll point you in the right direction so you get your essay done right.

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to write an a+ argumentative essay.

Miscellaneous

You'll no doubt have to write a number of argumentative essays in both high school and college, but what, exactly, is an argumentative essay and how do you write the best one possible? Let's take a look.

A great argumentative essay always combines the same basic elements: approaching an argument from a rational perspective, researching sources, supporting your claims using facts rather than opinion, and articulating your reasoning into the most cogent and reasoned points. Argumentative essays are great building blocks for all sorts of research and rhetoric, so your teachers will expect you to master the technique before long.

But if this sounds daunting, never fear! We'll show how an argumentative essay differs from other kinds of papers, how to research and write them, how to pick an argumentative essay topic, and where to find example essays. So let's get started.

What Is an Argumentative Essay? How Is it Different from Other Kinds of Essays?

There are two basic requirements for any and all essays: to state a claim (a thesis statement) and to support that claim with evidence.

Though every essay is founded on these two ideas, there are several different types of essays, differentiated by the style of the writing, how the writer presents the thesis, and the types of evidence used to support the thesis statement.

Essays can be roughly divided into four different types:

#1: Argumentative #2: Persuasive #3: Expository #4: Analytical

So let's look at each type and what the differences are between them before we focus the rest of our time to argumentative essays.

Argumentative Essay

Argumentative essays are what this article is all about, so let's talk about them first.

An argumentative essay attempts to convince a reader to agree with a particular argument (the writer's thesis statement). The writer takes a firm stand one way or another on a topic and then uses hard evidence to support that stance.

An argumentative essay seeks to prove to the reader that one argument —the writer's argument— is the factually and logically correct one. This means that an argumentative essay must use only evidence-based support to back up a claim , rather than emotional or philosophical reasoning (which is often allowed in other types of essays). Thus, an argumentative essay has a burden of substantiated proof and sources , whereas some other types of essays (namely persuasive essays) do not.

You can write an argumentative essay on any topic, so long as there's room for argument. Generally, you can use the same topics for both a persuasive essay or an argumentative one, so long as you support the argumentative essay with hard evidence.

Example topics of an argumentative essay:

- "Should farmers be allowed to shoot wolves if those wolves injure or kill farm animals?"

- "Should the drinking age be lowered in the United States?"

- "Are alternatives to democracy effective and/or feasible to implement?"

The next three types of essays are not argumentative essays, but you may have written them in school. We're going to cover them so you know what not to do for your argumentative essay.

Persuasive Essay

Persuasive essays are similar to argumentative essays, so it can be easy to get them confused. But knowing what makes an argumentative essay different than a persuasive essay can often mean the difference between an excellent grade and an average one.

Persuasive essays seek to persuade a reader to agree with the point of view of the writer, whether that point of view is based on factual evidence or not. The writer has much more flexibility in the evidence they can use, with the ability to use moral, cultural, or opinion-based reasoning as well as factual reasoning to persuade the reader to agree the writer's side of a given issue.

Instead of being forced to use "pure" reason as one would in an argumentative essay, the writer of a persuasive essay can manipulate or appeal to the reader's emotions. So long as the writer attempts to steer the readers into agreeing with the thesis statement, the writer doesn't necessarily need hard evidence in favor of the argument.

Often, you can use the same topics for both a persuasive essay or an argumentative one—the difference is all in the approach and the evidence you present.

Example topics of a persuasive essay:

- "Should children be responsible for their parents' debts?"

- "Should cheating on a test be automatic grounds for expulsion?"

- "How much should sports leagues be held accountable for player injuries and the long-term consequences of those injuries?"

Expository Essay

An expository essay is typically a short essay in which the writer explains an idea, issue, or theme , or discusses the history of a person, place, or idea.

This is typically a fact-forward essay with little argument or opinion one way or the other.

Example topics of an expository essay:

- "The History of the Philadelphia Liberty Bell"

- "The Reasons I Always Wanted to be a Doctor"

- "The Meaning Behind the Colloquialism ‘People in Glass Houses Shouldn't Throw Stones'"

Analytical Essay

An analytical essay seeks to delve into the deeper meaning of a text or work of art, or unpack a complicated idea . These kinds of essays closely interpret a source and look into its meaning by analyzing it at both a macro and micro level.

This type of analysis can be augmented by historical context or other expert or widely-regarded opinions on the subject, but is mainly supported directly through the original source (the piece or art or text being analyzed) .

Example topics of an analytical essay:

- "Victory Gin in Place of Water: The Symbolism Behind Gin as the Only Potable Substance in George Orwell's 1984"

- "Amarna Period Art: The Meaning Behind the Shift from Rigid to Fluid Poses"

- "Adultery During WWII, as Told Through a Series of Letters to and from Soldiers"

There are many different types of essay and, over time, you'll be able to master them all.

A Typical Argumentative Essay Assignment

The average argumentative essay is between three to five pages, and will require at least three or four separate sources with which to back your claims . As for the essay topic , you'll most often be asked to write an argumentative essay in an English class on a "general" topic of your choice, ranging the gamut from science, to history, to literature.

But while the topics of an argumentative essay can span several different fields, the structure of an argumentative essay is always the same: you must support a claim—a claim that can reasonably have multiple sides—using multiple sources and using a standard essay format (which we'll talk about later on).

This is why many argumentative essay topics begin with the word "should," as in:

- "Should all students be required to learn chemistry in high school?"

- "Should children be required to learn a second language?"

- "Should schools or governments be allowed to ban books?"

These topics all have at least two sides of the argument: Yes or no. And you must support the side you choose with evidence as to why your side is the correct one.

But there are also plenty of other ways to frame an argumentative essay as well:

- "Does using social media do more to benefit or harm people?"

- "Does the legal status of artwork or its creators—graffiti and vandalism, pirated media, a creator who's in jail—have an impact on the art itself?"

- "Is or should anyone ever be ‘above the law?'"

Though these are worded differently than the first three, you're still essentially forced to pick between two sides of an issue: yes or no, for or against, benefit or detriment. Though your argument might not fall entirely into one side of the divide or another—for instance, you could claim that social media has positively impacted some aspects of modern life while being a detriment to others—your essay should still support one side of the argument above all. Your final stance would be that overall , social media is beneficial or overall , social media is harmful.

If your argument is one that is mostly text-based or backed by a single source (e.g., "How does Salinger show that Holden Caulfield is an unreliable narrator?" or "Does Gatsby personify the American Dream?"), then it's an analytical essay, rather than an argumentative essay. An argumentative essay will always be focused on more general topics so that you can use multiple sources to back up your claims.

Good Argumentative Essay Topics

So you know the basic idea behind an argumentative essay, but what topic should you write about?

Again, almost always, you'll be asked to write an argumentative essay on a free topic of your choice, or you'll be asked to select between a few given topics . If you're given complete free reign of topics, then it'll be up to you to find an essay topic that no only appeals to you, but that you can turn into an A+ argumentative essay.

What makes a "good" argumentative essay topic depends on both the subject matter and your personal interest —it can be hard to give your best effort on something that bores you to tears! But it can also be near impossible to write an argumentative essay on a topic that has no room for debate.

As we said earlier, a good argumentative essay topic will be one that has the potential to reasonably go in at least two directions—for or against, yes or no, and why . For example, it's pretty hard to write an argumentative essay on whether or not people should be allowed to murder one another—not a whole lot of debate there for most people!—but writing an essay for or against the death penalty has a lot more wiggle room for evidence and argument.

A good topic is also one that can be substantiated through hard evidence and relevant sources . So be sure to pick a topic that other people have studied (or at least studied elements of) so that you can use their data in your argument. For example, if you're arguing that it should be mandatory for all middle school children to play a sport, you might have to apply smaller scientific data points to the larger picture you're trying to justify. There are probably several studies you could cite on the benefits of physical activity and the positive effect structure and teamwork has on young minds, but there's probably no study you could use where a group of scientists put all middle-schoolers in one jurisdiction into a mandatory sports program (since that's probably never happened). So long as your evidence is relevant to your point and you can extrapolate from it to form a larger whole, you can use it as a part of your resource material.

And if you need ideas on where to get started, or just want to see sample argumentative essay topics, then check out these links for hundreds of potential argumentative essay topics.

101 Persuasive (or Argumentative) Essay and Speech Topics

301 Prompts for Argumentative Writing

Top 50 Ideas for Argumentative/Persuasive Essay Writing

[Note: some of these say "persuasive essay topics," but just remember that the same topic can often be used for both a persuasive essay and an argumentative essay; the difference is in your writing style and the evidence you use to support your claims.]

KO! Find that one argumentative essay topic you can absolutely conquer.

Argumentative Essay Format

Argumentative Essays are composed of four main elements:

- A position (your argument)

- Your reasons

- Supporting evidence for those reasons (from reliable sources)

- Counterargument(s) (possible opposing arguments and reasons why those arguments are incorrect)

If you're familiar with essay writing in general, then you're also probably familiar with the five paragraph essay structure . This structure is a simple tool to show how one outlines an essay and breaks it down into its component parts, although it can be expanded into as many paragraphs as you want beyond the core five.

The standard argumentative essay is often 3-5 pages, which will usually mean a lot more than five paragraphs, but your overall structure will look the same as a much shorter essay.

An argumentative essay at its simplest structure will look like:

Paragraph 1: Intro

- Set up the story/problem/issue

- Thesis/claim

Paragraph 2: Support

- Reason #1 claim is correct

- Supporting evidence with sources

Paragraph 3: Support

- Reason #2 claim is correct

Paragraph 4: Counterargument

- Explanation of argument for the other side

- Refutation of opposing argument with supporting evidence

Paragraph 5: Conclusion

- Re-state claim

- Sum up reasons and support of claim from the essay to prove claim is correct

Now let's unpack each of these paragraph types to see how they work (with examples!), what goes into them, and why.

Paragraph 1—Set Up and Claim

Your first task is to introduce the reader to the topic at hand so they'll be prepared for your claim. Give a little background information, set the scene, and give the reader some stakes so that they care about the issue you're going to discuss.

Next, you absolutely must have a position on an argument and make that position clear to the readers. It's not an argumentative essay unless you're arguing for a specific claim, and this claim will be your thesis statement.

Your thesis CANNOT be a mere statement of fact (e.g., "Washington DC is the capital of the United States"). Your thesis must instead be an opinion which can be backed up with evidence and has the potential to be argued against (e.g., "New York should be the capital of the United States").

Paragraphs 2 and 3—Your Evidence

These are your body paragraphs in which you give the reasons why your argument is the best one and back up this reasoning with concrete evidence .

The argument supporting the thesis of an argumentative essay should be one that can be supported by facts and evidence, rather than personal opinion or cultural or religious mores.

For example, if you're arguing that New York should be the new capital of the US, you would have to back up that fact by discussing the factual contrasts between New York and DC in terms of location, population, revenue, and laws. You would then have to talk about the precedents for what makes for a good capital city and why New York fits the bill more than DC does.

Your argument can't simply be that a lot of people think New York is the best city ever and that you agree.

In addition to using concrete evidence, you always want to keep the tone of your essay passionate, but impersonal . Even though you're writing your argument from a single opinion, don't use first person language—"I think," "I feel," "I believe,"—to present your claims. Doing so is repetitive, since by writing the essay you're already telling the audience what you feel, and using first person language weakens your writing voice.

For example,

"I think that Washington DC is no longer suited to be the capital city of the United States."

"Washington DC is no longer suited to be the capital city of the United States."

The second statement sounds far stronger and more analytical.

Paragraph 4—Argument for the Other Side and Refutation

Even without a counter argument, you can make a pretty persuasive claim, but a counterargument will round out your essay into one that is much more persuasive and substantial.

By anticipating an argument against your claim and taking the initiative to counter it, you're allowing yourself to get ahead of the game. This way, you show that you've given great thought to all sides of the issue before choosing your position, and you demonstrate in multiple ways how yours is the more reasoned and supported side.

Paragraph 5—Conclusion

This paragraph is where you re-state your argument and summarize why it's the best claim.

Briefly touch on your supporting evidence and voila! A finished argumentative essay.

Your essay should have just as awesome a skeleton as this plesiosaur does. (In other words: a ridiculously awesome skeleton)

Argumentative Essay Example: 5-Paragraph Style

It always helps to have an example to learn from. I've written a full 5-paragraph argumentative essay here. Look at how I state my thesis in paragraph 1, give supporting evidence in paragraphs 2 and 3, address a counterargument in paragraph 4, and conclude in paragraph 5.

Topic: Is it possible to maintain conflicting loyalties?

Paragraph 1

It is almost impossible to go through life without encountering a situation where your loyalties to different people or causes come into conflict with each other. Maybe you have a loving relationship with your sister, but she disagrees with your decision to join the army, or you find yourself torn between your cultural beliefs and your scientific ones. These conflicting loyalties can often be maintained for a time, but as examples from both history and psychological theory illustrate, sooner or later, people have to make a choice between competing loyalties, as no one can maintain a conflicting loyalty or belief system forever.

The first two sentences set the scene and give some hypothetical examples and stakes for the reader to care about.

The third sentence finishes off the intro with the thesis statement, making very clear how the author stands on the issue ("people have to make a choice between competing loyalties, as no one can maintain a conflicting loyalty or belief system forever." )

Paragraphs 2 and 3

Psychological theory states that human beings are not equipped to maintain conflicting loyalties indefinitely and that attempting to do so leads to a state called "cognitive dissonance." Cognitive dissonance theory is the psychological idea that people undergo tremendous mental stress or anxiety when holding contradictory beliefs, values, or loyalties (Festinger, 1957). Even if human beings initially hold a conflicting loyalty, they will do their best to find a mental equilibrium by making a choice between those loyalties—stay stalwart to a belief system or change their beliefs. One of the earliest formal examples of cognitive dissonance theory comes from Leon Festinger's When Prophesy Fails . Members of an apocalyptic cult are told that the end of the world will occur on a specific date and that they alone will be spared the Earth's destruction. When that day comes and goes with no apocalypse, the cult members face a cognitive dissonance between what they see and what they've been led to believe (Festinger, 1956). Some choose to believe that the cult's beliefs are still correct, but that the Earth was simply spared from destruction by mercy, while others choose to believe that they were lied to and that the cult was fraudulent all along. Both beliefs cannot be correct at the same time, and so the cult members are forced to make their choice.

But even when conflicting loyalties can lead to potentially physical, rather than just mental, consequences, people will always make a choice to fall on one side or other of a dividing line. Take, for instance, Nicolaus Copernicus, a man born and raised in Catholic Poland (and educated in Catholic Italy). Though the Catholic church dictated specific scientific teachings, Copernicus' loyalty to his own observations and scientific evidence won out over his loyalty to his country's government and belief system. When he published his heliocentric model of the solar system--in opposition to the geocentric model that had been widely accepted for hundreds of years (Hannam, 2011)-- Copernicus was making a choice between his loyalties. In an attempt t o maintain his fealty both to the established system and to what he believed, h e sat on his findings for a number of years (Fantoli, 1994). But, ultimately, Copernicus made the choice to side with his beliefs and observations above all and published his work for the world to see (even though, in doing so, he risked both his reputation and personal freedoms).

These two paragraphs provide the reasons why the author supports the main argument and uses substantiated sources to back those reasons.

The paragraph on cognitive dissonance theory gives both broad supporting evidence and more narrow, detailed supporting evidence to show why the thesis statement is correct not just anecdotally but also scientifically and psychologically. First, we see why people in general have a difficult time accepting conflicting loyalties and desires and then how this applies to individuals through the example of the cult members from the Dr. Festinger's research.

The next paragraph continues to use more detailed examples from history to provide further evidence of why the thesis that people cannot indefinitely maintain conflicting loyalties is true.

Paragraph 4

Some will claim that it is possible to maintain conflicting beliefs or loyalties permanently, but this is often more a matter of people deluding themselves and still making a choice for one side or the other, rather than truly maintaining loyalty to both sides equally. For example, Lancelot du Lac typifies a person who claims to maintain a balanced loyalty between to two parties, but his attempt to do so fails (as all attempts to permanently maintain conflicting loyalties must). Lancelot tells himself and others that he is equally devoted to both King Arthur and his court and to being Queen Guinevere's knight (Malory, 2008). But he can neither be in two places at once to protect both the king and queen, nor can he help but let his romantic feelings for the queen to interfere with his duties to the king and the kingdom. Ultimately, he and Queen Guinevere give into their feelings for one another and Lancelot—though he denies it—chooses his loyalty to her over his loyalty to Arthur. This decision plunges the kingdom into a civil war, ages Lancelot prematurely, and ultimately leads to Camelot's ruin (Raabe, 1987). Though Lancelot claimed to have been loyal to both the king and the queen, this loyalty was ultimately in conflict, and he could not maintain it.

Here we have the acknowledgement of a potential counter-argument and the evidence as to why it isn't true.

The argument is that some people (or literary characters) have asserted that they give equal weight to their conflicting loyalties. The refutation is that, though some may claim to be able to maintain conflicting loyalties, they're either lying to others or deceiving themselves. The paragraph shows why this is true by providing an example of this in action.

Paragraph 5

Whether it be through literature or history, time and time again, people demonstrate the challenges of trying to manage conflicting loyalties and the inevitable consequences of doing so. Though belief systems are malleable and will often change over time, it is not possible to maintain two mutually exclusive loyalties or beliefs at once. In the end, people always make a choice, and loyalty for one party or one side of an issue will always trump loyalty to the other.

The concluding paragraph summarizes the essay, touches on the evidence presented, and re-states the thesis statement.

How to Write an Argumentative Essay: 8 Steps

Writing the best argumentative essay is all about the preparation, so let's talk steps:

#1: Preliminary Research

If you have the option to pick your own argumentative essay topic (which you most likely will), then choose one or two topics you find the most intriguing or that you have a vested interest in and do some preliminary research on both sides of the debate.

Do an open internet search just to see what the general chatter is on the topic and what the research trends are.

Did your preliminary reading influence you to pick a side or change your side? Without diving into all the scholarly articles at length, do you believe there's enough evidence to support your claim? Have there been scientific studies? Experiments? Does a noted scholar in the field agree with you? If not, you may need to pick another topic or side of the argument to support.

#2: Pick Your Side and Form Your Thesis

Now's the time to pick the side of the argument you feel you can support the best and summarize your main point into your thesis statement.

Your thesis will be the basis of your entire essay, so make sure you know which side you're on, that you've stated it clearly, and that you stick by your argument throughout the entire essay .

#3: Heavy-Duty Research Time

You've taken a gander at what the internet at large has to say on your argument, but now's the time to actually read those sources and take notes.

Check scholarly journals online at Google Scholar , the Directory of Open Access Journals , or JStor . You can also search individual university or school libraries and websites to see what kinds of academic articles you can access for free. Keep track of your important quotes and page numbers and put them somewhere that's easy to find later.

And don't forget to check your school or local libraries as well!

#4: Outline

Follow the five-paragraph outline structure from the previous section.

Fill in your topic, your reasons, and your supporting evidence into each of the categories.

Before you begin to flesh out the essay, take a look at what you've got. Is your thesis statement in the first paragraph? Is it clear? Is your argument logical? Does your supporting evidence support your reasoning?

By outlining your essay, you streamline your process and take care of any logic gaps before you dive headfirst into the writing. This will save you a lot of grief later on if you need to change your sources or your structure, so don't get too trigger-happy and skip this step.

Now that you've laid out exactly what you'll need for your essay and where, it's time to fill in all the gaps by writing it out.

Take it one step at a time and expand your ideas into complete sentences and substantiated claims. It may feel daunting to turn an outline into a complete draft, but just remember that you've already laid out all the groundwork; now you're just filling in the gaps.

If you have the time before deadline, give yourself a day or two (or even just an hour!) away from your essay . Looking it over with fresh eyes will allow you to see errors, both minor and major, that you likely would have missed had you tried to edit when it was still raw.

Take a first pass over the entire essay and try your best to ignore any minor spelling or grammar mistakes—you're just looking at the big picture right now. Does it make sense as a whole? Did the essay succeed in making an argument and backing that argument up logically? (Do you feel persuaded?)

If not, go back and make notes so that you can fix it for your final draft.

Once you've made your revisions to the overall structure, mark all your small errors and grammar problems so you can fix them in the next draft.

#7: Final Draft

Use the notes you made on the rough draft and go in and hack and smooth away until you're satisfied with the final result.

A checklist for your final draft:

- Formatting is correct according to your teacher's standards

- No errors in spelling, grammar, and punctuation

- Essay is the right length and size for the assignment

- The argument is present, consistent, and concise

- Each reason is supported by relevant evidence

- The essay makes sense overall

#8: Celebrate!

Once you've brought that final draft to a perfect polish and turned in your assignment, you're done! Go you!

Be prepared and ♪ you'll never go hungry again ♪, *cough*, or struggle with your argumentative essay-writing again. (Walt Disney Studios)

Good Examples of Argumentative Essays Online

Theory is all well and good, but examples are key. Just to get you started on what a fully-fleshed out argumentative essay looks like, let's see some examples in action.

Check out these two argumentative essay examples on the use of landmines and freons (and note the excellent use of concrete sources to back up their arguments!).

The Use of Landmines

A Shattered Sky

The Take-Aways: Keys to Writing an Argumentative Essay

At first, writing an argumentative essay may seem like a monstrous hurdle to overcome, but with the proper preparation and understanding, you'll be able to knock yours out of the park.

Remember the differences between a persuasive essay and an argumentative one, make sure your thesis is clear, and double-check that your supporting evidence is both relevant to your point and well-sourced . Pick your topic, do your research, make your outline, and fill in the gaps. Before you know it, you'll have yourself an A+ argumentative essay there, my friend.

What's Next?

Now you know the ins and outs of an argumentative essay, but how comfortable are you writing in other styles? Learn more about the four writing styles and when it makes sense to use each .

Understand how to make an argument, but still having trouble organizing your thoughts? Check out our guide to three popular essay formats and choose which one is right for you.

Ready to make your case, but not sure what to write about? We've created a list of 50 potential argumentative essay topics to spark your imagination.

Courtney scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT in high school and went on to graduate from Stanford University with a degree in Cultural and Social Anthropology. She is passionate about bringing education and the tools to succeed to students from all backgrounds and walks of life, as she believes open education is one of the great societal equalizers. She has years of tutoring experience and writes creative works in her free time.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Usage and Examples of a Rebuttal

Weakening an Opponent's Claim With Facts

David Hume Kennerly/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

A rebuttal takes on a couple of different forms. As it pertains to an argument or debate, the definition of a rebuttal is the presentation of evidence and reasoning meant to weaken or undermine an opponent's claim. However, in persuasive speaking, a rebuttal is typically part of a discourse with colleagues and rarely a stand-alone speech.

Rebuttals are used in law, public affairs, and politics, and they're in the thick of effective public speaking. They also can be found in academic publishing, editorials, letters to the editor, formal responses to personnel matters, or customer service complaints/reviews. A rebuttal is also called a counterargument.

Types and Occurrences of Rebuttals

Rebuttals can come into play during any kind of argument or occurrence where someone has to defend a position contradictory to another opinion presented. Evidence backing up the rebuttal position is key.

Formally, students use rebuttal in debate competitions. In this arena, rebuttals don't make new arguments , just battle the positions already presented in a specific, timed format. For example, a rebuttal may get four minutes after an argument is presented in eight.

In academic publishing, an author presents an argument in a paper, such as on a work of literature, stating why it should be seen in a particular light. A rebuttal letter about the paper can find the flaws in the argument and evidence cited, and present contradictory evidence. If a writer of a paper has the paper rejected for publishing by the journal, a well-crafted rebuttal letter can give further evidence of the quality of the work and the due diligence taken to come up with the thesis or hypothesis.

In law, an attorney can present a rebuttal witness to show that a witness on the other side is in error. For example, after the defense has presented its case, the prosecution can present rebuttal witnesses. This is new evidence only and witnesses that contradict defense witness testimony. An effective rebuttal to a closing argument in a trial can leave enough doubt in the jury's minds to have a defendant found not guilty.

In public affairs and politics, people can argue points in front of the local city council or even speak in front of their state government. Our representatives in Washington present diverging points of view on bills up for debate . Citizens can argue policy and present rebuttals in the opinion pages of the newspaper.

On the job, if a person has a complaint brought against him to the human resources department, that employee has a right to respond and tell his or her side of the story in a formal procedure, such as a rebuttal letter.

In business, if a customer leaves a poor review of service or products on a website, the company's owner or a manager will, at minimum, need to diffuse the situation by apologizing and offering a concession for goodwill. But in some cases, a business needs to be defended. Maybe the irate customer left out of the complaint the fact that she was inebriated and screaming at the top of her lungs when she was asked to leave the shop. Rebuttals in these types of instances need to be delicately and objectively phrased.

Characteristics of an Effective Rebuttal

"If you disagree with a comment, explain the reason," says Tim Gillespie in "Doing Literary Criticism." He notes that "mocking, scoffing, hooting, or put-downs reflect poorly on your character and on your point of view. The most effective rebuttal to an opinion with which you strongly disagree is an articulate counterargument."

Rebuttals that rely on facts are also more ethical than those that rely solely on emotion or diversion from the topic through personal attacks on the opponent. That is the arena where politics, for example, can stray from trying to communicate a message into becoming a reality show.

With evidence as the central focal point, a good rebuttal relies on several elements to win an argument, including a clear presentation of the counterclaim, recognizing the inherent barrier standing in the way of the listener accepting the statement as truth, and presenting evidence clearly and concisely while remaining courteous and highly rational.

The evidence, as a result, must do the bulk work of proving the argument while the speaker should also preemptively defend certain erroneous attacks the opponent might make against it.

That is not to say that a rebuttal can't have an emotional element, as long as it works with evidence. A statistic about the number of people filing for bankruptcy per year due to medical debt can pair with a story of one such family as an example to support the topic of health care reform. It's both illustrative — a more personal way to talk about dry statistics — and an appeal to emotions.

To prepare an effective rebuttal, you need to know your opponent's position thoroughly to be able to formulate the proper attacks and to find evidence that dismantles the validity of that viewpoint. The first speaker will also anticipate your position and will try to make it look erroneous.

You will need to show:

- Contradictions in the first argument

- Terminology that's used in a way in order to sway opinion ( bias ) or used incorrectly. For example, when polls were taken about "Obamacare," people who didn't view the president favorably were more likely to want the policy defeated than when the actual name of it was presented as the Affordable Care Act.

- Errors in cause and effect

- Poor sources or misplaced authority

- Examples in the argument that are flawed or not comprehensive enough

- Flaws in the assumptions that the argument is based on

- Claims in the argument that are without proof or are widely accepted without actual proof. For example, alcoholism is defined by society as a disease. However, there isn't irrefutable medical proof that it is a disease like diabetes, for instance. Alcoholism manifests itself more like behavioral disorders, which are psychological.

The more points in the argument that you can dismantle, the more effective your rebuttal. Keep track of them as they're presented in the argument, and go after as many of them as you can.

Refutation Definition

The word rebuttal can be used interchangeably with refutation , which includes any contradictory statement in an argument. Strictly speaking, the distinction between the two is that a rebuttal must provide evidence, whereas a refutation merely relies on a contrary opinion. They differ in legal and argumentation contexts, wherein refutation involves any counterargument, while rebuttals rely on contradictory evidence to provide a means for a counterargument.

A successful refutation may disprove evidence with reasoning, but rebuttals must present evidence.

- 4 Fast Debate Formats for the Secondary Classroom

- What Is a Critique in Composition?

- Definition and Examples of Praeteritio (Preteritio) in Rhetoric

- AP English Exam: 101 Key Terms

- Definition and Examples of an Ad Hominem Fallacy

- What Does Argumentation Mean?

- What Is the Straw Man Fallacy?

- Overview of the Jury Trial Stage of a Criminal Case

- Tips on Winning the Debate on Evolution

- Use Social Media to Teach Ethos, Pathos and Logos

- Reductio Ad Absurdum in Argument

- Ethos, Logos, Pathos for Persuasion

- Stage a Debate in Class

- The Parts of a Speech in Classical Rhetoric

- Men and Women: Equal at Last?

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.3: The Argumentative Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58378

- Lumen Learning

Learning Objectives

- Examine types of argumentative essays

Argumentative Essays

You may have heard it said that all writing is an argument of some kind. Even if you’re writing an informative essay, you still have the job of trying to convince your audience that the information is important. However, there are times you’ll be asked to write an essay that is specifically an argumentative piece.

An argumentative essay is one that makes a clear assertion or argument about some topic or issue. When you’re writing an argumentative essay, it’s important to remember that an academic argument is quite different from a regular, emotional argument. Note that sometimes students forget the academic aspect of an argumentative essay and write essays that are much too emotional for an academic audience. It’s important for you to choose a topic you feel passionately about (if you’re allowed to pick your topic), but you have to be sure you aren’t too emotionally attached to a topic. In an academic argument, you’ll have a lot more constraints you have to consider, and you’ll focus much more on logic and reasoning than emotions.

Argumentative essays are quite common in academic writing and are often an important part of writing in all disciplines. You may be asked to take a stand on a social issue in your introduction to writing course, but you could also be asked to take a stand on an issue related to health care in your nursing courses or make a case for solving a local environmental problem in your biology class. And, since argument is such a common essay assignment, it’s important to be aware of some basic elements of a good argumentative essay.

When your professor asks you to write an argumentative essay, you’ll often be given something specific to write about. For example, you may be asked to take a stand on an issue you have been discussing in class. Perhaps, in your education class, you would be asked to write about standardized testing in public schools. Or, in your literature class, you might be asked to argue the effects of protest literature on public policy in the United States.

However, there are times when you’ll be given a choice of topics. You might even be asked to write an argumentative essay on any topic related to your field of study or a topic you feel that is important personally.

Whatever the case, having some knowledge of some basic argumentative techniques or strategies will be helpful as you write. Below are some common types of arguments.

Causal Arguments

- In this type of argument, you argue that something has caused something else. For example, you might explore the causes of the decline of large mammals in the world’s ocean and make a case for your cause.

Evaluation Arguments

- In this type of argument, you make an argumentative evaluation of something as “good” or “bad,” but you need to establish the criteria for “good” or “bad.” For example, you might evaluate a children’s book for your education class, but you would need to establish clear criteria for your evaluation for your audience.

Proposal Arguments

- In this type of argument, you must propose a solution to a problem. First, you must establish a clear problem and then propose a specific solution to that problem. For example, you might argue for a proposal that would increase retention rates at your college.

Narrative Arguments

- In this type of argument, you make your case by telling a story with a clear point related to your argument. For example, you might write a narrative about your experiences with standardized testing in order to make a case for reform.

Rebuttal Arguments

- In a rebuttal argument, you build your case around refuting an idea or ideas that have come before. In other words, your starting point is to challenge the ideas of the past.

Definition Arguments

- In this type of argument, you use a definition as the starting point for making your case. For example, in a definition argument, you might argue that NCAA basketball players should be defined as professional players and, therefore, should be paid.

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...essments/20277

Essay Examples

- Click here to read an argumentative essay on the consequences of fast fashion . Read it and look at the comments to recognize strategies and techniques the author uses to convey her ideas.

- In this example, you’ll see a sample argumentative paper from a psychology class submitted in APA format. Key parts of the argumentative structure have been noted for you in the sample.

Link to Learning

For more examples of types of argumentative essays, visit the Argumentative Purposes section of the Excelsior OWL .

Contributors and Attributions

- Argumentative Essay. Provided by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/rhetorical-styles/argumentative-essay/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of a man with a heart and a brain. Authored by : Mohamed Hassan. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : pixabay.com/illustrations/decision-brain-heart-mind-4083469/. License : Other . License Terms : pixabay.com/service/terms/#license

Module 4: Writing in College

Argumentation, learning objectives.

- Examine the purpose, structure, and style of an argumentative essay

Argumentative Essays

Figure 1 . In political debate, politicians often tackle controversial topics. These same types of topics, where you are asked to defend a certain point of view, are often suitable for an argumentative essay.