Imagining the Anthropocene: Anne Carson’s “The Anthropology of Water”

Traveling by foot creates a corporeal connection with the land. Our species first migrated one footstep at a time in pursuit of the flora and fauna that fed us. When we began to undertake such journeys for spiritual reasons as well, our planet became marked by the many paths of our species’ longing.

“Anthropology is a science of mutual surprise,” Anne Carson writes. A sweeping sense of astonishment pervades her lyric essay “ The Anthropology of Water ,” in which a young, female speaker walks the Camino de Santiago. Along the course of a rugged pilgrimage, Carson’s defined formal structure enables the logical leaps that keep the speaker in a constant state of new encounter. The speaker considers dreams, folklore, the purposes and sensations of pilgrimage, and her love affair with a male companion she refers to only as “my Cid” as she seeks penance (for what, the reader doesn’t know). As her mind’s constellated meanderings undercut the journey’s unceasing forward motion, “The Anthropology of Water” erodes assumptions of linear progress.

Much of “Anthropology” is written in a diaristic sequence, a form attuned to the speaker’s movement. Each entry in “Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela” opens with a date (8 th of July, for example), a place (Sahagún, El Burgo…), and an epigraph from an earlier literary pilgrim (Mitsune, Basho, Shiren…). Simultaneously designating one place in time and referencing another point in another human’s journey, Carson twists her speaker’s path with that of previous travelers as interested as she is in a “sardine” or a “rising moon.”

Defined temporal and spatial markers act as stable fenceposts between which Carson pursues a pilgrim’s enigmas. “Penance can be a surprising study and pilgrims, even very authentic ones, raven in ways they do not expect,” Carson writes. In each day’s entry, thematic threads spring from, but are not limited to, the day’s path. Writing in the present tense to an unnamed “you,” the speaker refers to absent photographs and circles through recurrent images: bread, gold, dogs, “kinds of water.” Each entry shifts between direct address and scientific remove, terminating in a question or riddle: “When is a pilgrim like a photograph? When the blend of acids and sentiment is just right.” Carson’s elusive exits return the reader to the feeling of an endless pursuit through new territory.

A pilgrim moves through a foreign space in the act of questioning. “Pilgrims were people wondering, wondering. Whom shall I meet now?” The dizzying returns and repetitions allow the reader to feel the speaker’s accumulating emotions. She pushes through angers and absurdities, unable to communicate openly with her effortlessly affable companion. In both the journey and the written account, physical discipline holds the pilgrimage together. “Penance is one form we find, one form we insist on,” Carson writes.

The word “pilgrim” derives from the Latin “peregrinus,” meaning “foreign.” A foreigner moves across the earth, through a new land, seeking what? Near the beginning of the journey, Carson writes, “Spanish bread is the same color as the stones that lie along the roadside—gold. True, I often mistake stones for bread. Pilgrims’ hunger is a curious thing.” Though primary observation drives the speaker forward, it is not to be relied upon: “Breaking points appear.”

A diary is a daily practice of pouring out. It insists on forward motion, like the procession of footsteps the camino requires. Within those structures, Carson crafts a speaker whose vast and disparate inquiries engulf the reader in a fevered, feminine, consummately human voice. Just like the folktales about queens, murderers, and thieves, the speaker’s account switches and sparks; “Horizon beats upon the eyes.” Where does a pilgrimage end?

Related Posts

About Author

International literary expertise in licensing, live events, publishing & retail

KINDS OF WATER: AN ESSAY ON THE ROAD TO COMPOSTELA (from PLAINWATER)

- Anne Carson: Ecstatic Lyre

In this Book

- Joshua Marie Wilkinson, editor

- Published by: University of Michigan Press

- Series: Under Discussion

Table of Contents

- Half Title, Series Page, Title Page, Copyright, Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Joshua Marie Wilkinson

- Anne Carson’s Stereoscopic Poetics

- Jessica Fisher

- What Kind of Monster Am I?

- Dan Beachy-Quick

- Living on the Edge: The Bittersweet Place of Poetry

- Martin Corless-Smith

- Reading Carson Reading Brontë RE: The Soul’s Difficult Sexual Destiny

- Brian Teare

- The Gender of Sound: No Witness, No Words (or Song)?

- Virginia Konchan

- On Anne Carson’s Short Talks

- Timothy Liu

- How Is a Pilgrim Like a Soldier? Anne Carson’s “Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela”

- Christine Hume

- The Unbearable Withness of Being: On Anne Carson’s Plainwater

- Kristi Maxwell

- The Pilgrim and the Anthropologist

- Jennifer K. Dick

- Masters of the Open Secret: Meditations on Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red

- Harmony Holiday

- Who Can a Monster Blame for Being Red? Three Fragments on the Academic and the “Other” in Autobiography of Red

- Bruce Beasley

- “Some Affluence”: Reading Wallace Stevens with Anne Carson’s Economy of the Unlost

- Graham Foust

- To Gesture at Absence: A Reading-With

- Karla Kelsey

- “Parts of Time Fall on Her”: Anne Carson’s Men in the Off Hours

- Richard Greenfield

- Lacuna Is for Reign

- Douglas A. Martin

- pp. 101-106

- The Light of This Wound: Marriage, Longing, Desire in Anne Carson’s The Beauty of the Husband

- Andrea Rexilius

- pp. 107-113

- Who with Her Tears Soaks Mortal Streaming: Anne Carson and Wonderwater

- J. Michael Martinez

- pp. 114-120

- Antagonistic Collaborations, Tender Questions: On Anne Carson’s Answer Scars / Roni Horn’s Wonderwater

- Hannah Ensor

- pp. 121-126

- Opera Povera: Decreation, an Opera in Three Parts

- Cole Swensen

- pp. 127-131

- “To Undo the Creature”: The Paradox of Writing in Anne Carson’s Decreation

- Johanna Skibsrud

- pp. 132-137

- No Video: On Anne Carson

- pp. 138-144

- X inside an X

- Ander Monson

- pp. 145-147

- Sentences on Nox

- Eleni Sikelianos

- pp. 148-151

- Your Soul Is Blowing Apart: Antigonick and the Influence of Collaborative Process

- Bianca Stone

- pp. 152-155

- “Standing in / the Nick of Time”: Antigonick in Seven Short Takes

- Andrew Zawacki

- pp. 156-164

- What’s So Funny about Antigonick?

- Vanessa Place

- pp. 165-171

- From Geryon to G: Anne Carson’s Red Doc> and the Avatar

- pp. 172-180

- An Antipoem That Condenses Everything: Anne Carson’s Translations of the Fragments of Sappho

- Elizabeth Robinson

- pp. 181-187

- Sappho and the “Papyrological Event”

- John Melillo

- pp. 188-193

- Bringing the House Down: Trojan Horses and Other Malware in Anne Carson’s Grief Lessons: Four Plays by Euripides

- pp. 194-199

- Lessons in Grief and Corruption: Anne Carson’s Translations of Euripides

- Erika L. Weiberg

- pp. 200-205

- The “Dread Work” of Lyric: Anne Carson’s An Oresteia

- Angela Hume

- pp. 206-213

- Collaborating on Decreation : An Interview with Anne Carson

- Peter Streckfus

- pp. 214-222

- Contributors

- pp. 223-228

Additional Information

Project muse mission.

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Half Lives and Long Drives: An Interview with Anne Carson and Robert Currie

In conversation with sara elkamel and nyu undergraduates.

My copy of Anne Carson’s Plainwater is falling apart. It looks like a wall with slight water damage. I bought it at The Strand in 2016, and it has since traveled with me to at least four continents. Mostly, I have held onto the lyric essay at its center, “The Anthropology of Water,” which narrates an unnamed speaker’s pilgrimage to Compostela while together with a companion from whom she is, in many ways, distant. Time-stamped, anchored in towns along the trek, the prose moves us forward as the speaker’s mind leaps non-linearly. Carson’s writing was perhaps my first introduction to the mapless, lyric pilgrimage of the mind. “A pool of thoughts tilts this way and that in me,” she writes in Plainwater .

In Spring 2020, I managed to take the last class she taught at New York University’s Poetry MFA program, together with her partner and collaborator Robert Currie, before they retired. They call the class “EgoCircus,” and have taught versions of it over the years, at NYU and elsewhere. The pair have also worked together on various other cross-disciplinary projects, including the design of her book Nox (New Directions, 2010) and a series of experimental performances that incorporate Carson’s poetry with dance and film.

This spring, I started teaching an undergraduate class at NYU, assembled around ideas of the poetry and prose of pilgrimage and stasis. Naturally, I assigned excerpts from Plainwater , and to my delight, Anne Carson and Robert Currie accepted my invitation for a class visit. In the conversation below, a few of the students and I talk to Carson and Currie about the color red, finding a lyric voice, their collaborative creative process, and more.

Anne Carson: Sara [Elkamel] asked me to read from Plainwater , but I wrote it in the 80s and I haven’t looked at it since. So I decided that rather than study up on it, I would try to think what of it is still in my memory. And the only image really that I retained from writing that book is the one day where it describes the women who live in a wall. I don’t know if you remember that part. But there’s a town they go through, the two travelers, called Astorga, and in that town, it’s a traditional form of penance (or it was [in] medieval times) for a woman to wall herself up in the wall of a house and live in the hole, as a religious exercise in order to atone for sins, or undertake prayer, or who knows what. But she would live there and have no other life, no movement, and survive on whatever people gave her through the hole. I found that image so totally horrifying that as I say, it would never leave my mind. And it is a nightmare image, but it’s interesting in the context of pilgrimage.

It seems to me that people undertake pilgrimages because they’re stuck; they’re in some kind of situation in their life, or their mind, where they don’t want to be the person they are, and they don’t know how to change that unless they change everything . So they leave wherever they are, and go on a trek somewhere else. It’s an image of freedom; the idea of leaving your life and going on to the open road and ending up somewhere different. But oddly enough, it’s a kind of freedom that is also a sort of bondage, because when you undertake a pilgrimage, you’re bound to everything about the road—the geography, the weather, and all the traditions that are part of that pilgrimage from ancient times. So there is a freedom within which it is also binding and imprisoning. Anyhow, that’s why I thought this part was interesting to read. If you have the book, it’s the 14th of July. [Anne reads excerpt from “Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela,” Plainwater (Vintage, 2000).] And I will leave it there. It’s not a really upbeat passage, but I still think about it all the time.

Robert Currie: When you first read it, what was your impression?

Brede Baldwin: I just notice how much red there is everywhere. You’re talking about blushing, you’re talking about cheeks, and you’re talking about wolves seeing red. To me, that’s the most intimate color you could choose. So it just puts you in this mood for the entire passage. I’m wondering if there was any specific purpose behind this choice, or if you sort of just ran with it? Maybe I’m reading into nothing.

Anne Carson: No, it’s not nothing. I guess you might be able to see we have painted the room behind us entirely red. So red does spontaneously arise somehow. I don’t think I planned it that way. But one thing I have noticed—I don’t know if you’ve been to Spain, or if you’ve visited old dusty churches where there are religious paintings, but often they’re a bit faded. And what stays unfaded is usually the red. I guess it’s because of what they used to make the red in those times. But I remember the cheeks of people in religious paintings from the Middle Ages or early Renaissance being the thing that stands out. But I also just like red and put it in everywhere.

Robert Currie: The idea of pilgrimage is interesting to me because I was working on a piece a few years ago with another artist where we were fascinated with this nun, and we were trying to figure out how to film her. She was quite elderly, and she wanted to go on this particular pilgrimage, but Mother Superior wouldn’t let her. So she walked the interior of the monastery until she covered the distance of the pilgrimage. So she had her pilgrimage, but she did it on her own, within the walls of the monastery, which I thought was kind of amazing.

Anne Carson: Well, that’s the thing about this kind of religious penance, if that’s what it is, that it’s a game you make up. The only thing you have to do is make up some rules and then keep the rules, no matter what. That’s what pilgrims do. And there’s all these different ways to do it. Like when I did it with my friend, we walked the whole way. So it was 380 miles or something, it took six weeks, and we walked every day till we got to the next town. But there are a lot of people nowadays who commit themselves to taking a bus to the outskirts of town, the limit of the town, and they walk into the town center to be part of the practice of walking a pilgrimage. So it sort of seems hypocritical or even fake, but it’s just the question of you making up rules for yourself and keeping them. It’s like monopoly.

Mike Baretz: What kind of rules do you make up for yourself as you write? Specifically, what is your process of finding your voice and deciding how to say things? Is your writing voice the same way you think, or speak?

Anne Carson: Well, I think every piece of work has its own voice, and you have to figure out what that is, sort of work into it. It’s not the same voice from piece to piece. So when I read this now, it seemed like someone else wrote it. But I find that each thought has a sound inside it. I mean, you can hear in your head how the thought should sound like. Sometimes there are rhythms and melodies even before there are words, and you have to find the words that fit into that rhythm or melody. But the voice comes with the thought, for me.

Mike Baretz: Is it at all like method acting, as in, are you thinking in that voice a lot? Or do you step away, and then come back to it?

Anne Carson: I don’t believe I’m much of a method actor. I don’t think I would make dinner while talking to myself as Geryon [ Autobiography of Red ’s protagonist], or argue with Currie in the voice of Isaiah , although, that might be effective, now that I think about it.

Robert Currie: But you do think of the idea in every setting. If you’re swimming, you’re thinking about the idea. If you’re cooking, you’re thinking about the idea. You might not be in the idea, but you’re thinking about it. And you’re kind of working through it.

Anne Carson: Yeah. I think most writers live half lives. You’re half in your life and half in your head, going on with what you’ve been writing; the sort of the divided page of every day.

Robert Currie: You know, people often ask what makes an artist, and I think it’s just the willingness to do the work without thinking in terms of the result. Anne gets up at eight in the morning and she writes, and then she goes swimming and then she writes, and then she comes back and writes and then she has dinner, she takes a walk, and she thinks and she writes. And Julian Schnabel makes a movie and when he’s done with the movie he goes to his studio and he paints.

Sara Elkamel: But when it comes to collaboration, there isn’t a clear workspace, medium or tool; there isn’t the notebook or the studio—the work often happens in-between places, especially when, as is the case for you two, you’re already living together. So what does the willingness to do the work look like?

Robert Currie: Well, there are a zillion different ways to collaborate. John Cage and Merce Cunningham worked separately and then combined what they made the evening of the performance. [Igor] Stravinsky and George Balanchine worked note by note through a score to the movement of a dance. And they were both extraordinary collaborations. But when Anne and I collaborate, it always starts with her text, it always starts in the same place; she gives me the text and I wander around with it, and deal with it. And I don’t think we talk that much about it, until we get to a certain point.

Anne Carson: Well, before there’s a text though, we do do a lot of driving around. Talking in the car is great, because you don’t have to look at the other person, you know, they’re over there. And you can have the radio on.

Robert Currie: Anne rides in the backseat by the way, with books and notebooks. I’m always in the front seat by myself.

Anne Carson: But still, it’s a difference because you’re physically moving. It’s a different space of thought than being stationery in a room. I think a lot of our ideas germinate in the car.

Robert Currie: We take walks too…

Anne Carson: Yeah, but cars are better than walks.

Robert Currie: I just remembered something. Anne and I were at a dinner party a zillion years ago, and it was one of those parties where someone wanted everybody to go around the table and say something about themselves, you know, one of those horrible situations. This question was who is the artist that most inspired you. And they got to us, and Anne said:

Anne Carson: Oh. I said Homer.

Robert Currie: And I said John Cage. And this leads to the next thing I wanted to say, which is: When you have somebody who’s interested in Homer, and somebody who’s interested in John Cage, how do you make that work together?

Anne Carson: How do we make it work?

Robert Currie: I don’t know, I’ve never figured it out.

Anne Carson: I was hoping it was a rhetorical question!

Robert Currie: [Laughs] But anyway, I don’t know if Anne agrees with me, you probably don’t, but I think the reason I’ve enjoyed doing [Egocircus] is because I think the loveliest thing we can do on any day is think with somebody else. I just like thinking with other people. [To Anne] But you probably want to crawl into your hole.

Anne Carson: I’m not going to argue. [They both laugh.]

Hannah Siegel: Anne, you spoke about the women living alone in the walls and how you were really drawn to that element. As you work on pieces like Plainwater , do you find yourself drawn to certain elements more than others? Are there certain aspects of the world you create that you find yourself wanting to describe more than others?

Anne Carson: I follow the thought, whatever that thought is, through whatever story occurs to me to attach to it, but the parts that attract me are the parts that are unknown, fundamentally. And so it’s just searching around in those dark subjects for whatever I can figure out to think about them.

Robert Currie: But if you had five books open on your desk while you’re working, and you’ve gotten to a good point in a piece, would you just go to any of those other books that had no relationship to your idea?

Anne Carson: Well, maybe. I mean, there’s all kinds of ways to change your thought or open your thought, but I don’t think that’s what Hannah was asking about.

Robert Currie: But I think the other part she was asking about is how delving more deeply into an idea works. I mean, if you’re fascinated by it, do you stop yourself at some point, or do you go to the end of the idea?

Anne Carson: Yeah, you have to go to the end of the idea. Or it will punish you.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Sara Elkamel

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Following the Vita Sackville-West School of Gardening

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- español

- français

- português (Brasil)

Estadísticas

- UVaDOC Principal

- PUBLICACIONES UVa

- Revistas de la UVa

- ES Review. Spanish Journal of English Studies

- ES Review. Spanish Journal of English Studies - 2021 - Num. 42

- Ver ítem

Mostrar el registro sencillo del ítem

Ficheros en el ítem

Este ítem aparece en la(s) siguiente(s) colección(ones)

- ES Review. Spanish Journal of English Studies - 2021 - Num. 42 [16]

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

“Love is the mystery inside this walking”: Anne Carson on the Road to Compostela

2021, ES Review. Spanish Journal of English Studies

This paper explores Anne Carson’s “Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela,” the author’s journal on her pilgrimage to Santiago. Taking water as a metaphor for the Camino, the text reflects the creative dimension of the pilgrimage both from an artistic and personal standpoint. Alternative discourses of the female writer and pilgrim occur in a text that is an essay and a meditation on the forms of resilience put into practice by Carson after facing a series of personal losses. The progressive construction of self-knowledge is seen as an emancipatory act that transcended Carson’s mourning period in her experience, which she took as an opportunity to embrace personal transformation. I suggest that my approach can bring useful perspectives not only to further and refine knowledge on Carson in Spain but also for the consideration of resilience as an aspect that contributes to the critical understanding of narratives of individual and social transformation.

Related Papers

Vanessa Baish

I presented this paper at the 2018 ACLA Conference for a seminar titled: The Politics of Literary Cartography, organized by Rebbecca Brown and Christopher S. Lewis.

Ad Limina. Revista del Camino de Santiago y de las Peregrinaciones

Xosé M . Sánchez Sánchez

El traqueteo del tiempo y el viaje. Aspectos acústicos de la peregrinación medieval Resumen: El silencio parece la base de la vida medieval, y sin embargo el sonido acaba tomando cuerpo en cada resquicio. Este estudio indaga la alternancia de silencio y resonancia acústica, su presencia, ausencia y convivencia a lo largo del camino de la peregrinación. En la Edad Media, los peregrinos cristianos realizaban sus caminatas sagradas principalmente en un arduo silencio, interrumpido por entretenidas recitaciones, canciones de caminata rítmica e himnos latinos cantados de memoria. En cada parada, los peregrinos rompían el silencio con la reconfortante y predecible música de la liturgia. Melodías y conocidas canciones comunitarias marcaban el fluir del día hacia la sacralidad sónica de capillas e iglesias con paredes de piedra. La música y el lenguaje eran los sonidos emanados de la vida que campaban contra el ritmo de la naturaleza y testimoniaban el decidido esfuerzo humano. Este paisaje acústico de la vida medieval cambiaba en el transcurso del viaje. Cada ciudad y núcleo constituían la llegada a tierra en una "isla acústica" donde había nuevas formas de canto y habla, diferentes señales sonoras para el trabajo e incluso la ley, como llamadas al refugio, comercio y toque de queda. El silencio sagrado podía imponerse al enemigo: los musulmanes conquistadores se llevaron las campanas de las iglesias cristianas como trofeos de guerra para silenciar sus llamadas infieles al culto, mientras que los cristianos ascendentes transformaron minaretes en campanarios. No todo fue piedad silenciada, pues la estridente fiesta de los peregrinos podría incluso detener tormentas. ------------------------------ Abstract: Silence was the baseline for medieval life. In the Middle Ages, Christian pilgrims made their sacred treks mostly in an arduous hush, punctuated by entertaining recitations, rhythmic walking songs, and Latin hymns chanted from memory. At each stop pilgrims broke the silence with the comforting, predictable music of liturgy. Well-known communal music and song marked the day’s progress toward sonic sacredness in the echoey holiness of stone walled chapels and churches. Music and language were the crafted sounds of life that played against a backbeat of nature and purposeful human effort. The acoustic landscape of medieval life changed in the course of the journey. Every city and settlement was a coming ashore on an “acoustic island” where there were new forms of song and speech, different sonic signals for labor and even law, such as calls to shelter, commerce and curfew. Sacred silence could be imposed on an enemy: conquering Muslims carried off Christian church bells as war trophies to silence their infidel calls to worship, while ascendant Christians transformed minarets into bell towers. It wasn’t all muted piety: raucous pilgrim partying could even stop storms. This study categorizes some of the sounds, silences and significance of medieval travel as witnessed by art, architecture and documentary sources.

Rana P.B. SINGH

Contents: Preface and Acknowledgements: xii-xv; Foreword‒ Dallen J. Timothy (USA): 1-4; Sacredscapes & Sacred Places and Sense of Geography: Some Reflections‒ Rana P.B. Singh (India): 5-46; Pilgrimage and Literature‒ Jamie S. Scott (Canada): 47-94; Sufi views on Pilgrimage in Islam‒ Muhammad Khalid Masud (Pakistan): 95-110; The ‘Architecture of Light’: Between Sacred Geometry to Biophotonic Technology‒ Aritia Poenaru & Traian D. Stãnciulescu (Romania): 111-130; Kailash– the Centre of the World‒ Tomo Vinšćak and Danijela Smiljanić (Croatia): 131-152; Rolwaling: A Sacred Buddhist Valley in Nepal‒ Janice Sacherer (Japan): 153-174; Landscape, Memory and Identity: A case of Southwest China‒ Zhou Dandan (China): 175-194; The miracles of Mt. Wutai, China: the ambiguity of Sacred place in Buddhism‒ Jeffrey F. Meyer (USA): 195-210; Sacred Spaces, Pilgrimage and Tourism at Muktinath, Nepal‒ Rana P.B. Singh (India) & P.C. Poudel (Nepal): 211-246; The Mythic landscape of the Buddhist places of Pilgrimage in India‒ Rana P.B. Singh & Pravin S. Rana (India): 247-284; Current Jewish Pilgrimage-Tourism‒ Noga Collins-Kreiner (Israel): 285-300; The road to St. James, El Camino de Santiago: the spirit of place and environmental ethics‒ Kingsley K. Wu (USA): 301-320; Sacred Places of Japan: Sacred Geography in the vicinity of the cities of Sendai and Nara‒ James A. Swan (USA): 321-334; the contributors: 335-336; Index: 337-343; Editor: 344. 26 Jan. 2011, 22x 15cm, ca. xiv + 344pp, 16 tables, 51 figures, <ca. 122,100 words> Hb, ISBN (10): 81-8290-227-4. Rs 1495.oo/ US$ 55. Shubhi Publications, New Delhi.

Peter Jan Margry

Francisco Buide del Real

Reflective Practice Formation and Supervision in Ministry

Martha Stortz

Rosanna Mestre-Perez

Durkheim's study of the social function of religion interprets pilgrimage and tourism as forms of travel that involve a transition from the profane/routine to the sacred/religious. Tourism along the Camino de Santiago today is based on Christian pilgrimage routes dating back to the 9th century leading to the tomb of the Apostle Saint James the Great in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. Since the late 20th century, institutional policies aimed at promoting the Camino de Santiago have fostered a secularised image of the Santiago pilgrimage that has resulted in a spectacular rise in tourism in recent decades. Thanks to the ability of cinema to create and disseminate powerful imaginaries related to a place or a culture, depictions of the Camino in film, among other media, have contributed to the development of this image. This article focuses on an aspect that has not received much attention in explorations of the Camino in either film studies or tourist studies, with a textu...

Imagining an end of the world. Histories and Mythologies of the Santiago - Finisterre Connection, in: Christina Sánchez-Carretero (ed.), Walking to the End of the World. Heritage, Pilgrimage and the Camino to Finisterre (New York 2015) p. 32-52

On the history and mythology of the Camino Finisterre

Edward Piekut

After taking part in the Camino the author was interested to research the impact of St James on the modern world. This draft paper contains his findings.

RELATED PAPERS

Maryjane Dunn

International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage

Daniel Moulin

International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, Volume 7(v), Special Issue "Sacred Space, Time and Pilgrimage"

Berenika Seryczyńska

Zachary Jones , Jean Leloup , Steven Gardner

Dani Schrire

Practical Matters / A Journal of Religious Practices and Practical Theology

Kathryn Barush

Journal of Religion and Health

Paula Remoaldo

Polyxeni Moira

ES Review Spanish Journal of English Studies

Magdalena Flores-Quesada

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 8 (1)

Antti Lahelma

Sara Di Resta

Vitor Ambrósio

Lana Kim McGeary

Christiane Bis-Worch & Claudia Theune (eds): Religion, cults & rituals in the medieval rural environment (Proceedings Ruralia XI, Luxembourg), p. 13-24

Bert Groenewoudt

Church History and Religious Culture 101 (2021) 3–32

Sean Perrone

Sara A. Williams

Piotr Roszak , Tomasz Huzarek

Ana Echevarria

Alex Norman

Roberto Cipriani

ES Review. Spanish Journal of English Studies

Begoña Lasa-Alvarez

Łukasz Mróz

Revista Galega de Economía

Rossella Moscarelli

ES Review: Spanish Journal of English Studies

Maria C Fellie

Lucy Ridsdale

Mosaic: a journal for the interdisciplinary study of literature

Lisa Signori

Tinakori: Critical Journal of the Katherine Mansfield Society

Kym Brindle

Tinakori: Critical Journal of the Katherine Mansfield Society.

Alan Ali Saeed

Matthew R Anderson

The Way of St. James: Renewing Insights

Marcin Kazmierczak , Miguel Ángel Belmonte

Sociology of Religion

Thomas J . Coleman III

EAAE Conservation-Consumption

Donatella Fiorani

Anna Stenning

Michael Hahn

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Pilgrimage routes and the cult of the relic

Basilica Ste-Madeleine, Vézelay, France, dedicated 1104 (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The end of the world

Y2K. The Rapture. 2012. For over a decade, speculation about the end of the world has run rampant—all in conjunction with the arrival of the new millennium. The same was true for our religious European counterparts who, prior to the year 1000, believed the Second Coming of Christ was imminent, and the end was nigh.

When the apocalypse failed to materialize in 1000, it was decided that the correct year must be 1033, a thousand years from the death of Jesus Christ, but then that year also passed without any cataclysmic event.

Just how extreme the millennial panic was, remains debated. It is certain that from the year 950 onwards, there was a significant increase in building activity, particularly of religious structures. There were many reasons for this construction boom beside millennial panic, and the building of monumental religious structures continued even as fears of the immediate end of time faded.

Not surprisingly, this period also witnessed a surge in the popularity of the religious pilgrimage. A pilgrimage is a journey to a sacred place. These are acts of piety and may have been undertaken in gratitude for the fact that doomsday had not arrived, and to ensure salvation, whenever the end did come.

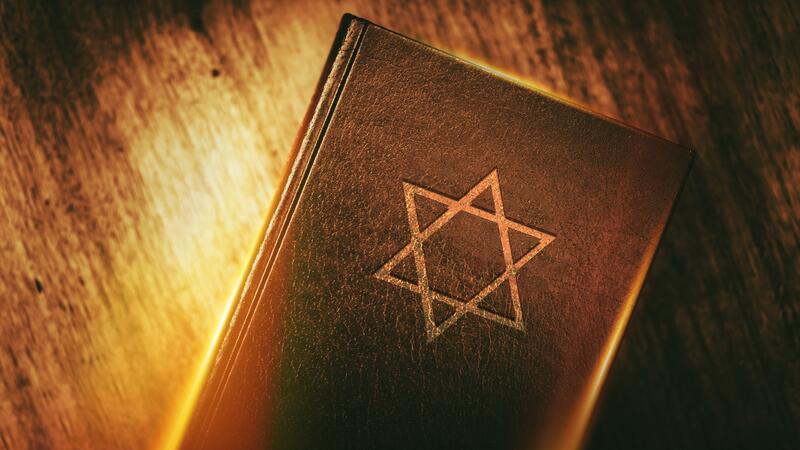

Map of pilgrimage routes (image adapted from: Manfred Zentgraf, Volkach, Germany)

The pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela

Pilgrims from the tympanum of Cathedral of St. Lazare, Autun (photo: Holly Hayes, Art History Images)

For the average European in the 12th Century, a pilgrimage to the Holy Land of Jerusalem was out of the question—travel to the Middle East was too far, too dangerous and too expensive. Santiago de Compostela in Spain offered a much more convenient option.

To this day, hundreds of thousands of faithful travel the “Way of Saint James” to the Spanish city of Santiago de Compostela. They go on foot across Europe to a holy shrine where bones, believed to belong to Saint James, were unearthed. The Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela now stands on this site.

The pious of the Middle Ages wanted to pay homage to holy relics, and pilgrimage churches sprang up along the route to Spain. Pilgrims commonly walked barefoot and wore a scalloped shell, the symbol of Saint James (the shell’s grooves symbolize the many roads of the pilgrimage).

In France alone there were four main routes toward Spain. Le Puy, Arles, Paris and Vézelay are the cities on these roads and each contains a church that was an important pilgrimage site in its own right.

Why make a pilgrimage?

A pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela was an expression of Christian devotion and it was believed that it could purify the soul and perhaps even produce miraculous healing benefits. A criminal could travel the “Way of Saint James” as an act penance. For the everyday person, a pilgrimage was also one of the only opportunities to travel and see some of the world. It was a chance to meet people, perhaps even those outside one’s own class. The purpose of pilgrimage may not have been entirely devotional.

The cult of the relic

Reliquary of St. Foy at Conque Abbey (photo: Holly Hayes, Art History images)

Pilgrimage churches can be seen in part as popular desinations, a spiritual tourism of sorts for medieval travelers. Guidebooks, badges and various souvenirs were sold. Pilgrims, though traveling light, would spend money in the towns that possessed important sacred relics.

The cult of relic was at its peak during the Romanesque period (c. 1000 – 1200). Relics are religious objects generally connected to a saint, or some other venerated person. A relic might be a body part, a saint’s finger, a cloth worn by the Virgin Mary, or a piece of the True Cross.

Relics are often housed in a protective container called a reliquary. Reliquarys are often quite opulent and can be encrusted with precious metals and gemstones given by the faithful. An example is the Reliquary of Saint Foy, located at Conques abbey on the pilgrimage route. It is said to hold a piece of the child martyr’s skull. A large pilgrimage church might be home to one major relic, and dozens of lesser-known relics. Because of their sacred and economic value, every church wanted an important relic and a black market boomed with fake and stolen goods.

Portal, Cathedral of Saint Lazare, Autun, 12th century

Accommodating crowds

St. Sernin, Toulouse (plan)

Pilgrimage churches were constructed with some special features to make them particularly accessible to visitors. The goal was to get large numbers of people to the relics and out again without disturbing the Mass in the center of the church. A large portal that could accommodate the pious throngs was a prerequisite. Generally, these portals would also have an elaborate sculptural program, often portraying the Second Coming—a good way to remind the weary pilgrim why they made the trip!

A pilgrimage church generally consisted of a double aisle on either side of the nave (the wide hall that runs down the center of a church). In this way, the visitor could move easily around the outer edges of the church until reaching the smaller apsidioles or radiating chapels. These are small rooms generally located off the back of the church behind the altar where relics were often displayed. The faithful would move from chapel to chapel venerating each relic in turn.

Thick walls, small windows

The thrust of a barrel vault

Romanesque churches were dark. This was in large part because of the use of stone barrel-vault construction. This system provided excellent acoustics and reduced fire danger. However, a barrel vault exerts continuous lateral (outward pressure) all along the walls that support the vault.

This meant the outer walls of the church had to be extra thick. It also meant that windows had to be small and few. When builders dared to pierce walls with additional or larger windows they risked structural failure. Churches did collapse.

Nave, Tournus Cathedral, 11th century

Groin vault

Later, the masons of the Gothic period replaced the barrel vault with the groin vault which carries weight down to its four corners, concentrating the pressure of the vaulting, and allowing for much larger windows.

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

¿En qué podemos ayudarle?

- Co n gresos

“Love is the mystery inside this walking” : Anne Carson on the Road to Compostela

Universidad de almería.

Almería, España

- Localización: ES Review. Spanish Journal of English Studies , ISSN-e 2531-1654, ISSN 2531-1646, Nº. 42, 2021 , págs. 179-197

- Idioma: inglés

- “El amor es el misterio de este caminar”: Anne Carson en el Camino de Santiago

- Texto completo ( pdf )

Este artículo estudia “Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela,” de Anne Carson, el diario sobre su peregrinación a Santiago. Con el agua como metáfora del Camino, el texto refleja la dimensión creativa de la peregrinación tanto desde el punto de vista artístico como personal. Concurren en el texto discursos diferentes: el de la escritora y el de la peregrina, en un trabajo que es a la vez ensayo y meditación sobre las formas de resiliencia empleadas por Carson tras sufrir una serie de pérdidas personales. La construcción progresiva de autoconocimiento se observa como un acto emancipador que trasciende el período de duelo de Carson, como oportunidad para abrazar una experiencia de transformación personal. Propongo una aproximación a Carson que puede contribuir no solo a conocer más a la autora en España, sino también a la consideración de la resiliencia como aspecto a tener en cuenta en el análisis de las narrativas de transformación individual y social.

This paper explores Anne Carson’s “Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela, ” the author’s journal on her pilgrimage to Santiago. Taking water as a metaphor for the Camino, the text reflects the creative dimension of the pilgrimage both from an artistic and personal standpoint. Alternative discourses of the female writer and pilgrim occur in a text that is an essay and a meditation on the forms of resilience put into practice by Carson after facing a series of personal losses. The progressive construction of self-knowledge is seen as an emancipatory act that transcended Carson’s mourning period in her experience, which she took as an opportunity to embrace personal transformation. I suggest that my approach can bring useful perspectives not only to further and refine knowledge on Carson in Spain but also for the consideration of resilience as an aspect that contributes to the critical understanding of narratives of individual and social transformation.

Acceso de usuarios registrados

- Dialnet Plus

Opciones de compartir

Opciones de entorno.

- Sugerencia / Errata

© 2001-2024 Fundación Dialnet · Todos los derechos reservados

- Accesibilidad

- Aviso Legal

- R e gistrarse

On The Road to Compostela

Learn online, on-demand webinar, about harold attridge, reading material, upcoming content with harold attridge, related content, return to academy courses.

Information Links

- About the Professor

Harold Attridge

Professor Attridge, dean of Yale Divinity School from 2002 to 2012, has made scholarly contributions to New Testament exegesis and to the study of Hellenistic Judaism and the history of the early Church. His publications include Essays on John and Hebrews, Hebrews: A Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews, First-Century Cynicism in the Epistles of Heraclitus, The Interpretation of Biblical History in the Antiquitates Judaicae of Flavius Josephus, Nag Hammadi Codex I: The Jung Codex, and The Acts of Thomas, as well as numerous book chapters and articles in scholarly journals.

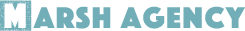

Codex Calixtinus

Read portions of the Codex Calixtinus.

Download the reading.

The Golden Legend of St. James

These are the highlights of the story of the apostle James, also known as James the son of Zebedee, or James the brother of John, or Boanerges, (which means the Son of Thunder), or James the Greater, or also Santiago.

Recommended Books

A compilation of books and readings from Professor Harold Attridge.

Download the reading list.

Upcoming Content

Hellenistic Judaism:From Alexander the Great to the End of the Second Temple

Tuesdays at 11 - 12:30 p.m. eastern October 13 - November 10, 2020

Faculty: Harold Attridge

Our Place in the World: The Histories of Maps

Faculty: James Salzman ’85 Tuesday, July 14 at 3 p.m. eastern

Watch On-Demand

Camino de Santiago: La Creación Divina

Faculty Commentary: Harold Attridge Thursday, July 16 at 1 p.m. eastern

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

As her mind's constellated meanderings undercut the journey's unceasing forward motion, "The Anthropology of Water" erodes assumptions of linear progress. Much of "Anthropology" is written in a diaristic sequence, a form attuned to the speaker's movement. Each entry in "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela" opens ...

How Is a Pilgrim Like a Soldier?: Anne Carson's "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela" Download; XML; The Unbearable Withness of Being:: On Anne Carson's Plainwater Download; XML; The Pilgrim and the Anthropologist Download; XML; Masters of the Open Secret:: Meditations on Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red Download; XML

This paper explores Anne Carson's "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela," the author's journal on her pilgrimage to Santiago. Taking water as a metaphor for the Camino, the ...

Carson's work by focusing on "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela" (hereinafter, "Kinds of Water"), which is one of the seven pieces that make "The Anthropology of Water ...

"Kinds of Water: An essay on the road to Compostela" 50 CHRISTINE HUME The Unbearable Withness of Being: on Anne Carson's Plainwater 56 KRISTI MAXWELL The Pilgrim and the Anthropologist 63 JENNIFER K. DICK Masters of the open secret: Meditations on Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red 69

© All rights reserved. The Marsh Agency. 2024 | Privacy PolicyPrivacy Policy

Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela St. Jean Pied de Port 20th of June the good thing is we know the glasses are for drinking Machado At the foot of the port of Roncesvalles, a small town bathes itself. Thunderstorms come down from the mountains at evening. Balls of fire roll through the town. Air cracks apart like a green fruit.

This paper explores Anne Carson's "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela," the author's journal on her pilgrimage to Santiago. Taking water as a metaphor for the Camino, the text reflects the creative dimension of the pilgrimage both from an artistic and personal standpoint.

Taking water as... This paper explores Anne Carson's "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela," the author's journal on her pilgrimage to Santiago. This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience.

Published by: University of Michigan Press. View. summary. Anne Carson's works re-think genre in some of the most unusual and nuanced ways that few writers ever attempt, from her lyric essays, enigmatic poems, and novels in verse to further forays into video and comics and collaborative performance. Carson's pathbreaking translations of ...

This paper explores Anne Carson's "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela," the author's journal on her pilgrimage to Santiago.

So there is a freedom within which it is also binding and imprisoning. Anyhow, that's why I thought this part was interesting to read. If you have the book, it's the 14th of July. [Anne reads excerpt from "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela," Plainwater (Vintage, 2000).] And I will leave it there.

Cambiar navegación. español; English; français; Deutsch; português (Brasil) español; English; français; Deutsch; português (Brasil)

Kinds of water drown us. Kinds of water do not. My water jar splashes companionably on my back as I walk. A pool of thoughts tilts this way and that in me. Socrates, after bathing, came back to his cell unhurriedly and drank the hemlock. The others wept. Swans swam in around him. And he began to talk about the coming journey, to an un

A few parts I did enjoy but they were sparse. The contents are a varied lot to say the least. Even the last part "The Anthropology of Water," which is over half of the book consists of 7 different, highly varied, pieces. The piece I enjoyed the most was "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela" from "The Anthropology of Water."

Short essay on Anne Carson's "Kinds of Water" from the book "ANNE CARSON ECSTATIC LYRE" out from University of Michigan Press this spring (2015) and edited by JM Wilkinson. I have also included in the PDF the Table of Contents for the entire book on Carson.

The most travelled pilgrimage road - the Camino Francés - is an east-west route covering 500 miles from St. Jean Pied-au-Port in France to Santiago (Figure 4).It traverses northern Spain through the Basque country and Pamplona, the arid meseta region, and the green Celtic hills of Galicia. This main camino is a geopolitical transect through the cultural landscapes of Basques, Castilians ...

This paper explores Anne Carson's "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela," the author's journal on her pilgrimage to Santiago.

6. See for example: Theresa Burkhardt-Felder, Pray for Me in Santiago: Walking the Ancient Pilgrim Road to Santiago de Compostela (Fremantle: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 2005), 271; Lee Hoinacki, El Camino: Walking to Santiago de Compostela (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996); Tony Kevin, Walking the Camino: A Modern Pilgrimage to Santiago (Melbourne: Scribe, 2007), 172.

This paper explores Anne Carson's "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela," the author's journal on her pilgrimage to Santiago. Taking water as a metaphor for the Camino, the text reflects the creative dimension of the pilgrimage both

The pious of the Middle Ages wanted to pay homage to holy relics, and pilgrimage churches sprang up along the route to Spain. Pilgrims commonly walked barefoot and wore a scalloped shell, the symbol of Saint James (the shell's grooves symbolize the many roads of the pilgrimage). In France alone there were four main routes toward Spain.

This paper explores Anne Carson's "Kinds of Water: An Essay on the Road to Compostela, " the author's journal on her pilgrimage to Santiago. Taking water as a metaphor for the Camino, the text reflects the creative dimension of the pilgrimage both from an artistic and personal standpoint. Alternative discourses of the female writer and ...

Professor Attridge, dean of Yale Divinity School from 2002 to 2012, has made scholarly contributions to New Testament exegesis and to the study of Hellenistic Judaism and the history of the early Church. His publications include Essays on John and Hebrews, Hebrews: A Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews, First-Century Cynicism in the ...