Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Systematic Review

- Published: 25 September 2020

Social determinants of health and child maltreatment: a systematic review

- Amy A. Hunter 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Glenn Flores 3 , 4

Pediatric Research volume 89 , pages 269–274 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7965 Accesses

53 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Child maltreatment causes substantial numbers of injuries and deaths, but not enough is known about social determinants of health (SDH) as risk factors. The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the association of SDH with child maltreatment.

Five data sources (PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, SCOPUS, JSTORE, and the Social Intervention Research and Evaluation Network Evidence Library) were searched for studies examining the following SDH: poverty, parental educational attainment, housing instability, food insecurity, uninsurance, access to healthcare, and transportation. Studies were selected and coded using the PICOS statement.

The search identified 3441 studies; 33 were included in the final database. All SDH categories were significantly associated with child maltreatment, except that there were no studies on transportation or healthcare. The greatest number of studies were found for poverty ( n = 29), followed by housing instability (13), parental educational attainment (8), food insecurity (1), and uninsurance (1).

Conclusions

SDH, including poverty, parental educational attainment, housing instability, food insecurity, and uninsurance, are associated with child maltreatment. These findings suggest an urgent priority should be routinely screening families for SDH, with referrals to appropriate services, a process that could have the potential to prevent both child maltreatment and subsequent recidivism.

SDH, including poverty, parental educational attainment, housing instability, food insecurity, and uninsurance, are associated with child maltreatment.

No prior published systematic review, to our knowledge, has examined the spectrum of SDH with respect to their associations with child maltreatment.

These findings suggest an urgent priority should be routinely screening families for SDH, with referrals to appropriate services, a process that could have the potential to prevent both child maltreatment and subsequent recidivism

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

A new era: improving use of sociodemographic constructs in the analysis of pediatric cohort study data

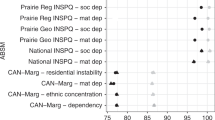

Assessing childhood health outcome inequalities with area-based socioeconomic measures: a retrospective cross-sectional study using Manitoba population data

Influence of race/ethnicity and income on the link between adverse childhood experiences and child flourishing

Child maltreatment is a pervasive public health problem in the United States (US). 1 Comprised of acts of commission and omission by a parent or other caregiver (e.g., physical abuse, sexual abuse, and various forms of neglect), 2 child maltreatment is a substantial cause of pediatric injury and death. In 2018, nearly 700,000 childhood victims of nonfatal maltreatment were identified, and an estimated 1770 children died. 1 The combined human and institutional cost attributed to maltreatment morbidity and mortality in the US is estimated to be $124 billion annually. 3

The World Health Organization defines social determinants of health (SDH) as “the conditions in which people are born, grown, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of life.” 4 These conditions are shaped by the distribution of resources, and connect facets of the physical, social, and built environment associated with health outcomes. 5 Among the most commonly recognized SDH (economic stability, education, neighborhood and built environment, health and healthcare, and social and community context), 6 poverty is a major and often overarching factor. Poverty also has been identified as a known risk factor for child maltreatment. 7 Thus, identifying how poverty and other SDH are associated with child maltreatment is a necessary step to develop effective interventions for maltreatment prevention and treatment, and mitigating the risk of associated physical and psychological injury.

Not enough is known about the association of SDH with child maltreatment. Four published systematic reviews have included analyses that examined the relationship between a single or two SDH and maltreatment. Two included socioeconomic status, 8 , 9 one included socioeconomic status and parental educational attainment, 10 and the fourth included immigration status. 11 No published systematic reviews (to our knowledge), however, have examined the spectrum of SDH with respect to their associations with child maltreatment. Therefore, the aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the associations of SDH (including poverty, housing insecurity, food insecurity, uninsurance, healthcare access, and transportation) with child maltreatment.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were selected using the PICOS approach for inclusion and exclusion. 12 , 13 The a priori inclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (1) English-language studies, (2) children 0–18 years old living in the US, (3) peer-reviewed, (4) observational and experimental designs, (5) outcome measures reported for at least one form of maltreatment, and 6) exposure measures for at least one SDH. The exclusion criteria were: (1) specific SDH could not be identified, and (2) conference presentations (e.g., abstracts, posters, or oral presentations).

The outcome of interest was child maltreatment, defined by the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Reauthorization Act of 2010 as “at a minimum, any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation, or an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.” 2 Included studies were assessed for the associations of selected SDH—including poverty, food insecurity, housing instability, parental educational attainment, child uninsurance, transportation barriers, and access barriers to healthcare—with child maltreatment. These SDH were chosen because they are domains hypothesized to be most likely associated with child maltreatment and were addressed in a recently published SDH screening instrument used for testing interventions effective in reducing SDH and improving child and caregiver health. 14 Immigration status was not included because of the recent publication of a systematic review examining the association of this SDH with child maltreatment. 11

Data sources

Five data sources were searched through March 2020: (1) PubMed, (2) Web of Science Core Collection, (3) SCOPUS, (4) JSTORE, and (5) the Social Intervention Research and Evaluation Network Evidence Library. All searches contained the following terms: (“Child Abuse”[Mesh] OR “child abuse”[tw] OR “child maltreatment”[tw] OR “child mistreatment”[tw] OR “child neglect”[tw]) AND (“Social Determinants of Health”[Mesh] OR “social determinants of health”[tw] OR “social class”). Searches for terms related to specific SDH varied. A sample search strategy (SCOPUS) can be found in Supplementary Table S 1 (online) .

An effort-to-yield measure of search precision, number needed to read (NNR) was calculated by taking the inverse of the precision of the searches. Precision was calculated by dividing the number of included studies by the number of screened studies, after removal of duplicates. NNR quantifies the number of articles that would be needed to be read before finding one that meets the established inclusion criteria. Dependent on the subject and inclusion criteria, this number provides insights into the time and resources needed for replication, or to conduct a similar study.

Selection of studies

All studies were stored on a Microsoft Excel document detailing the reasons for inclusion or exclusion.

Data abstraction

A codebook was developed using Microsoft Excel. Variables included study characteristics (year of publication, study design and population size, duration, data sources, and level[s] of analysis), sociodemographic characteristics of the study population (child age, racial composition, and sex), SDH under investigation, child maltreatment type (sexual, physical, psychological, neglect, multiple forms, and other), and measures of study quality.

Study quality

A modified version of the Downs and Black checklist was used to assess study quality (Supplementary Table S 2 ). 15 Each item was scored as no (0) or yes (1). The sum of all items ranged from 1 to 8, with higher scores representing a lower risk of bias.

Data synthesis

The criteria for SDH and definitions of child maltreatment varied by study. Therefore, we were unable to combine endpoints in a meta-analysis. Data synthesis at the level of the individual, family, and community were used to analyze included studies.

Study registration

The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020166969).

Study characteristics

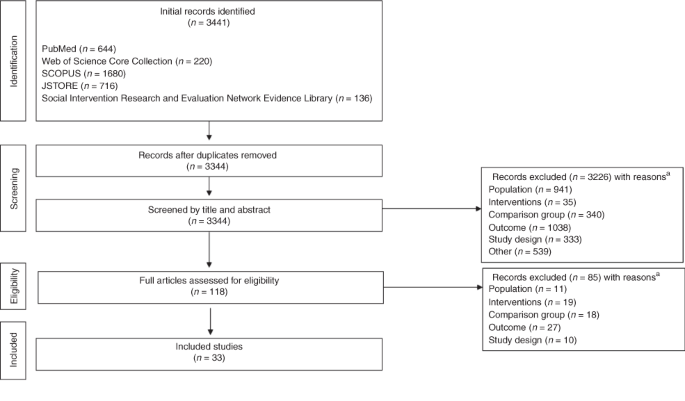

Our initial search yielded 3441 studies. After screening by titles and abstracts, 118 met the initial inclusion criteria. Following a full review of 118 studies, 33 were included in the final analysis. The process for selecting included studies is presented in Fig. 1 . Search precision was 0.0096 and the NNR was 104. The characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1 . Included studies were published from 1978 to 2020. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 Nine studies used national data, 16 , 23 , 27 , 30 , 36 , 38 , 42 , 43 , 47 and the remaining studies used data from individual states, including 14 from the Midwest, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 45 four from the South, 21 , 22 , 32 , 37 four from the Northeast, 34 , 35 , 46 , 48 one from the West (California), 24 and one from the Pacific (Alaska). 44 Of these studies, 5 conducted chart reviews, 7 used cohort study designs, 7 used a cross-sectional design, and 14 conducted ecological analyses. Included studies assessed the relationship between SDH and child maltreatment at the levels of the individual, zip code, county, and census tracts.

a Studies may have been excluded for multiple reasons.

Study outcomes

Twenty-nine studies explored the association of poverty with child maltreatment. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 47 Poverty was found to be consistently and strongly associated with maltreatment, with all but three studies identifying a significant association between either familial or community-level poverty and child maltreatment. 16 , 18 , 21 Across studies, poverty was defined by county, 45 neighborhood, 41 familial/household income, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 23 , 28 , 41 , 42 , 43 socioeconomic status, 44 poverty rate, 21 , 27 , 35 , 40 unemployment, 16 , 17 , 21 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 40 percentage of families living below the federal poverty level, 24 , 28 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 children living in poverty, 17 , 47 receipt of public assistance, 19 , 25 , 31 , 40 composite impoverishment scores, 26 and self-reported acute financial challenges. 22

In some studies, the relationship between poverty and maltreatment differed by abuse type. For example, one study found that neighborhood poverty was associated with all three forms of child maltreatment, but to different degrees. 38 Another study indicated that financial problems were strongly associated with neglect and abandonment, but the association was less pronounced for sexual abuse. 21

Associations between poverty and maltreatment varied by race/ethnicity. A study comparing predominantly white and black neighborhoods found that the association between poverty and child maltreatment was strongest in whites. 25 Research linking multiple sources of data showed that black children living in poverty were twice as likely to be reported for needs-based neglect than their white counterparts. 26 A recent study showed that when income was held constant, white race was strongly associated with both sexual abuse and neglect, and black race was associated with physical abuse. 27

Housing instability

Thirteen studies examined the relationship between housing instability and child maltreatment. 16 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 40 , 46 Most studies revealed that housing instability is associated with child maltreatment. Among these studies, the definition of housing stability varied, and included percent vacancy, 21 , 26 , 32 , 33 , 40 rates of foreclosure and delinquency, 16 , 18 , 34 hazardous living conditions, 29 and instability/mobility (>1 move per year). 20 , 23 , 28 Only one study examined homelessness, performing an analysis of hospital and pediatric ambulatory records of children <18 years old. 46 After matching families on income, homeless children were found to have higher rates of maltreatment-related emergency-department (ED) visits and child maltreatment than their nonhomeless counterparts. One study found that displacement due to foreclosure, eviction, or mortgage delinquency was associated with maltreatment investigations. 34 Two studies documented that housing instability/mobility (>1 move per year) was associated with child protective service (CPS) reports and maltreatment risk. 20 , 23

Two studies found no association between housing insecurity and child maltreatment. 18 , 28 In the first, housing instability consisted of an aggregate measure of material hardship, including difficulty paying rent, eviction, or having experienced any utility shutoff in the previous year. 18 In the second, housing instability was measured by residential mobility. 28

Several studies reported differences in the association between housing stability and child maltreatment type. Two identified an association between the percent of vacant housing in communities and sexual abuse. 21 , 32 Another study found that hazardous housing conditions were associated with neglect, but not physical abuse; a history of housing instability increased the strength of this association. 29 One study found that mortgage delinquency was associated with traumatic brain injury and other forms of physical abuse. 20

Food insecurity

Just one study examined the relationship between food insecurity and child maltreatment. 30 An analysis of a national sample from the Fragile Families and Childhood Wellbeing Study revealed that, compared with food-secure households, food-insecure households experienced increased rates of total parental aggression (7% vs. 20%, respectively). Controlling for maternal characteristics did not attenuate this association.

Parental educational attainment

Eight studies considered the relationship between parental educational attainment and child maltreatment. 17 , 18 , 20 , 24 , 25 , 32 , 41 , 42 The results of most studies indicate that low parental educational attainment is associated with child maltreatment. Parental educational attainment was defined as high-school completion in six studies, 17 , 18 , 20 , 32 , 41 , 42 maternal education level in one, 25 and completion of postsecondary education in the last. 24 Two studies found no association. 18 , 24 Notably, one of these studied failed to report victim and perpetrator demographic characteristics (age, sex, or race/ethnicity), 18 and the other relied on self-reported data. 24

Uninsurance

One study was identified that examined the association of the child lacking health insurance with child maltreatment. 48 This study reported that a higher proportion of preadolescent children seen in the ED with suspected sexual child abuse were uninsured, compared with a control group of children seen in the ED with upper-limb fractures, at 52% vs. 1%, respectively. No statistical analyses, however, were conducted, nor is it clear whether there was matching of cases and controls by age, sex, or other relevant characteristics.

The search did not reveal any studies that examined the associations of transportation or access to healthcare with child maltreatment.

Multiple studies document that SDH, including poverty, housing instability, food insecurity, low parental educational attainment, and child uninsurance, are significantly associated with child maltreatment. A recent systematic review also concluded that although the immigrant parental status is associated with a lower likelihood of overall child maltreatment, it may be associated with a higher risk of child neglect and neglectful supervision. 11 Taken together, these findings suggest that an urgent priority, therefore, should be to routinely screen families for SDH in inpatient and outpatient settings and in CPS, and to address identified SDH with referrals to appropriate services. This screening and referral process could have the potential to not only prevent child maltreatment by reducing or eliminating the SDH before they result in maltreatment, but might also decrease the risk of maltreatment recidivism in families in which maltreatment already has occurred. The American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, and the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine all have endorsed SDH screening and service referral. 49 , 50 , 51 Several studies document that patients and caregivers are comfortable with completing SDH screening. 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 Addressing SDH by referral to such services as case managers, social workers, housing vouchers, medical–legal partnerships, and parent mentors, already has been shown to reduce hospitalizations, improve housing quality and stability, enhance economic security, improve healthcare outcomes, insure more uninsured children, increase the quality of care, empower parents, and save money for society, 57 thereby holding great promise as interventions that may prove effective in ultimately reducing or preventing child maltreatment.

Poverty was the SDH for which the greatest number of studies documented an association with child maltreatment. Although few studies have investigated the temporal relationship between poverty and child maltreatment, 8 there is evidence that families living in poverty are more likely to be reported to CPS for neglect. 58 Poverty sequelae, such as inability to feed, clothe, or house a child, overlap with the definition of child neglect, so it is important to distinguish intentional neglect from family challenges related to living in poverty. Differential or alternative response is one CPS approach that addresses maltreatment reports by attending to unmet family needs. 59 An analysis of the effectiveness of this form of intervention has shown that families living in poverty benefit most from this approach. 60 To date, this response has been implemented at the individual and family levels. Extending differential or alternative response to the community level may be an effective strategy for families living in impoverished neighborhoods, where racial biases in child maltreatment reports and investigations have been identified.

The study results underscore several unanswered questions regarding the association between SDH and child maltreatment. First, it is unclear whether transportation barriers or impaired access to healthcare are associated with child maltreatment, given that no studies were identified on these SDH. Second, because the definitions for each SDH varied considerably within and across studies (especially for poverty), it is unclear whether more consistent SDH definitions would yield different findings. Third, because males as caregivers and heads of household were under-represented and often excluded from some study populations, 20 , 23 , 25 , 33 an unanswered question is whether there are associations of paternal educational attainment and other male-caregiver SDHs with child maltreatment. Although single mothers have been identified as an at-risk population for maltreatment perpetration, it is equally important to examine the role that men play in maltreatment. In a previous analysis, the first author identified men as the predominant perpetrator in 58% of cases of fatal maltreatment in the US. 61 Results of our study emphasize the need for research inclusive of male caregivers, to identify and mitigate risk factors before they escalate to maltreatment fatalities. Fourth, most studies focusing on sexual abuse were primarily limited to female populations, 32 despite evidence that male children also are victims of sexual abuse. There is an urgent need to investigate how SDH perpetuate or protect against sexual abuse in male children, so that prevention efforts can be tailored by sex. Finally, because most studies combined maltreatment into one aggregate category, an unanswered question is what are the associations of SDH with specific maltreatment categories. It has been posited that each maltreatment type has a unique etiology, and lumping these types into one category likely attenuates the ability to identify meaningful associations. Although few studies in this systematic review disaggregated by maltreatment categories, those that did found significant differences in maltreatment risk according to the SDH examined.

Based on the study findings, a research agenda is proposed to address key issues regarding the association of SDH with child maltreatment. Research is needed to address the aforementioned identified research gaps, including studies on transportation barriers, impaired access to healthcare, consistently defined SDH, SDH for male caregivers, and the associations of SDH with specific maltreatment categories and male victims of sexual abuse. Studies are needed to determine whether there is a direct association between the number of SDH and the risk of maltreatment, and whether the presence of multiple SDH can synergistically increase maltreatment risk. Research is urgently needed to determine whether SDH screening and referral to appropriate services result in SDH reduction and elimination as well as decreases in or the prevention of child maltreatment and maltreatment recidivism.

Limitations and strengths

Certain study limitations should be noted. First, as with all systematic reviews, the quality of this analysis is limited by the scientific rigor of included studies. Second, studies were selected based on the search criteria. It is possible that relevant literature was missed because of the heterogeneity of terms used to describe the various SDH and child maltreatment. Third, many included studies were cross-sectional or ecological, preventing the ability to draw conclusions about the temporal relationship between SDH and child maltreatment. Fourth, many data sources for the included studies used administrative data derived from CPS. In most instances, these records only included reports of maltreatment that were screened in and accepted for either an investigation or alternative response. As a result, these data sources likely exclude many cases of maltreatment, given evidence demonstrating equivalent risk of incidence and recurrence between maltreatment reports and substantiations. 28 , 38

SDH, including poverty, parental educational attainment, housing instability, food insecurity, and uninsurance, are associated with child maltreatment. These findings suggest that an urgent priority should be routinely screening families for SDH, with referrals to appropriate services, a process that could have the potential to prevent both child maltreatment and subsequent recidivism. Unanswered questions include whether SDH are associated with specific maltreatment categories and male victims of sexual abuse, and whether transportation barriers, impaired access to healthcare, consistently defined SDH, and SDH for male caregivers are associated with child maltreatment. A proposed research agenda includes addressing these unanswered questions; determining whether there is a direct association between the number of SDH and the risk of maltreatment, and whether the presence of multiple SDH can synergistically increase maltreatment risk; and investigations on whether SDH screening and referral to appropriate services result in SDH reduction and elimination, as well as decreases in or the prevention of child maltreatment and maltreatment recidivism.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child maltreatment 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2018 (2020).

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, Children’s Bureau. The Child Abuse Prevention And Treatment Act (CAPTA) 2010, Washington, DC. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/capta.pdf (2011).

Fang, X., Brown, D. S., Florence, C. S. & Mercy, J. A. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse Negl. 36 , 156–165 (2012).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

World Health Organization. About social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/ (2020).

US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Establishing a Holistic Framework to Reduce Inequities in HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STDs, and Tuberculosis in the United States . (US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 2010).

Healthy People 2020. Social determinants of health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health (2020).

Fortson, B. L., Klevens, J., Merrick, M. T., Gilbert, L. K. & Alexander, S. P. Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect: A Technical Package for Policy, Norm, and Programmatic Activities (National Center for Injury Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016).

Conrad-Hiebner, A. & Byram, E. The temporal impact of economic insecurity on child maltreatment: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 21 , 157–178 (2020).

PubMed Google Scholar

Stith, S. M. et al. Risk factors in child maltreatment: a meta analytic review of the literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 14 , 13–29 (2009).

Google Scholar

Connell-Carrick, K. A critical review of the empirical literature: identifying correlates of child neglect. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 20 , 389–425 (2003).

Millett, L. S. The healthy immigrant paradox and child maltreatment: a systematic review. J. Immigr. Minor Health 18 , 1199–1215 (2016).

Higgins, J. P. & Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions , Vol. 4 (Wiley, Hoboken, 2011).

Littlel, J. H., Corcoran, J. & Pillai, V. K. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (Oxford University Press, New York, 2008).

Gottlieb, L. M. et al. Effects of in-person assistance vs personalized written resources about social services on household social risks and child and caregiver health: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 3 , e200701 (2020).

Downs, S. H. & Black, N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 52 , 377–384 (1998).

CAS Google Scholar

Wood, J. N. et al. Local macroeconomic trends and hospital admissions for child abuse, 2000-2009. Pediatrics 130 , e358–364 (2012).

Weissman, A. M., Jogerst, G. J. & Dawson, J. D. Community characteristics associated with child abuse in Iowa. Child Abuse Negl. 27 , 1145–1159 (2003).

Slack, K. S., Holl, J. L., McDaniel, M., Yoo, J. & Bolger, K. Understanding the risks of child neglect: an exploration of poverty and parenting characteristics. Child Maltreatment 9 , 395–408 (2004).

Slack, K. et al. Child protective intervention in the context of welfare reform: the effects of work and welfare on maltreatment reports. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 22 , 517–536 (2003).

Slack, K. S., Font, S., Maguire-Jack, K. & Berger, L. M. Predicting child protective services (CPS) involvement among low-income U.S. families with young children receiving nutritional assistance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14 , 1197 (2017).

PubMed Central Google Scholar

Morris, M. C. et al. Connecting child maltreatment risk with crime and neighborhood disadvantage across time and place: a bayesian spatiotemporal analysis. Child Maltreatment 24 , 181–192 (2019).

Martin, M. J. & Walters, J. Familial correlates of selected types of child abuse and neglect. J. Marriage Fam. 44 , 267–276 (1982).

Marcal, K. E. The impact of housing instability on child maltreatment: a causal investigation. J. Fam. Soc. Work 21 , 331–347 (2018).

Maguire-Jack, K. & Font, S. A. Community and individual risk factors for physical child abuse and child neglect: variations by poverty status. Child Maltreatment 22 , 215–226 (2017).

Koch, J. et al. Risk of child abuse or neglect in a cohort of low-income children. Child Abuse Negl . 19 , 291–295 (1995).

Korbin, J. E., Coulton, C. J., Chard, S., Platt-Houston, C. & Su, M. Impoverishment and child maltreatment in African American and European American neighborhoods. Dev. Psychopathol. 10 , 215–233 (1998).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kim, H. & Drake, B. Child maltreatment risk as a function of poverty and race/ethnicity in the USA. Int. J. Epidemiol. 47 , 780–787 (2018).

Jonson-Reid, M., Drake, B. & Zhou, P. Neglect subtypes, race, and poverty: individual, family, and service characteristics. Child Maltreatment 18 , 30–41 (2013).

Hirsch, B. K., Yang, M. Y., Font, S. & Slack, K. S. Physically hazardous housing and risk for child protective services involvement. Child Welf. 94 , 87–104 (2015).

Helton, J. J., Jackson, D. B., Boutwell, B. B. & Vaughn, M. G. Household food insecurity and parent-to-child aggression. Child Maltreatment 24 , 213–221 (2019).

Gross-Manos, D. et al. Why does child maltreatment occur? Caregiver perspectives and analyses of neighborhood structural factors across twenty years. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 99 , 138–145 (2019).

Greeley, S. C. et al. Community characteristics associated with seeking medical evaluation for suspected child sexual abuse in greater Houston. J. Prim. Prev. 37 , 215–230 (2016).

Garbarino, J. & Crouter, A. Defining the community context for parent-child relations: the correlates of child maltreatment. Child Dev. 49 , 604–616 (1978).

Frioux, S. et al. Longitudinal association of county-level economic indicators and child maltreatment incidents. Matern. Child Health J. 18 , 2202–2208 (2014).

Fong, K. Neighborhood inequality in the prevalence of reported and substantiated child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 90 , 13–21 (2019).

Farrell, C. A. et al. Community poverty and child abuse fatalities in the United States. Pediatrics 139 , e20161616 (2017).

Ernst, J. S. Community-level factors and child maltreatment in a suburban county. Soc. Work Res. 25 , 133–142 (2001).

Eckenrode, J., Smith, E. G., McCarthy, M. E. & Dineen, M. Income inequality and child maltreatment in the United States. Pediatrics 133 , 454–461 (2014).

Drake, B. & Pandey, S. Understanding the relationship between neighborhood poverty and specific types of child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 20 , 1003–1018 (1996).

Coulton, C. J., Richter, F. G., Korbin, J., Crampton, D. & Spilsbury, J. C. Understanding trends in neighborhood child maltreatment rates: a three-wave panel study 1990-2010. Child Abuse Negl. 84 , 170–181 (2018).

Coulton, C. J., Korbin, J. E. & Su, M. Neighborhoods and child maltreatment: a multi-level study. Child Abuse Negl. 23 , 1019–1040 (1999).

Berger, L. Socioeconomic factors and substandard parenting. Soc. Serv. Rev. 81 , 485–522 (2007).

Berger, L. M., Font, S. A., Slack, K. S. & Waldfogel, J. Income and child maltreatment in unmarried families: evidence from the earned income tax credit. Rev. Econ. House. 15 , 1345–1372 (2017).

Austin, A. E. et al. Heterogeneity in risk and protection among Alaska Native/American Indian and Non-Native children. Prev. Sci. 21 , 86–97 (2020).

Anderson, B. L., Pomerantz, W. J. & Gittelman, M. A. Intentional injuries in young Ohio children: is there urban/rural variation? J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 77 , S36–40 (2014).

Alperstein, G., Rappaport, C. & Flanigan, J. M. Health problems of homeless children in New York City. Am. J. Public Health 78 , 1232–1233 (1988).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Moore, K. A., Nord, C. W. & Peterson, J. L. Nonvoluntary sexual activity among adolescents. Fam. Plann. Perspect. 21 , 110–114 (1989).

Kupfer, G. M. & Giardino, A. P. Reimbursement and insurance coverage in cases of suspected sexual abuse in the emergency department. Child Abuse Negl. 19 , 291–295 (1995).

Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics . 137 , 1–14 (2016).

American Academy of Physicians. The EveryONE project: screening tools and resources to advance health equity. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/social-determinants-of-health/everyone-project/eop-tools.html (2020).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health (National Academies Press, Washington, 2019).

De Marchis, E. H., Alderwick, H. & Gottlieb, L. M. Do patients want help addressing social risks? J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 33 , 170–175 (2020).

De Marchis, E. H. et al. Part I: a quantitative study of social risk screening acceptability in patients and caregivers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 57 , S25–S37 (2019).

Wylie, S. A. et al. Assessing and referring adolescents’ health-related social problems: qualitative evaluation of a novel web-based approach. J. Telemed. Telecare 18 , 392–398 (2012).

Hassan, A. et al. Youths’ health-related social problems: concerns often overlooked during the medical visit. J. Adolesc. Health 53 , 265–271 (2013).

Byhoff, E. et al. Part II. A qualitative study of social risk screening acceptability in patients and caregivers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 57 , S38–S46 (2019).

Hogan, A. H. & Flores, G. Social determinants of health and the hospitalized child. Hosp. Pediatr. 10 , 101–103 (2020).

Yang, M. Y. The effect of material hardship on child protective service involvement. Child Abuse Negl. 41 , 113–125 (2015).

Child Welfare Information Gateway. Differential Response to Reports of Child Abuse and Neglect (US Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau, Washington, 2014).

Siegel, G. L. Lessons from the Beginning of Differential Response: Why it Works and When it Doesn’t (Institute of Applied Research, St. Louis, 2012); retrieved from http://www.iarstl.org/papers/DRLessons.pdf (2012).

Hunter, A. A., DiVietro, S., Scwab-Reese, L. & Riffon, M. An epidemiologic examination of perpetrators of fatal child maltreatment using the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS). J. Interpers. Violence 886260519851787 (2019).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Marissa Gauthier for her assistance with the initial citation search.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Injury Prevention Center, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT, USA

Amy A. Hunter

Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Connecticut, Farmington, CT, USA

Department of Pediatrics, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, CT, USA

Amy A. Hunter & Glenn Flores

Health Services Research Institute, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, CT, USA

Glenn Flores

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

A.A.H. and G.F. made substantial contributions to the study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the article, and revising the article critically for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Glenn Flores .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary material, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hunter, A.A., Flores, G. Social determinants of health and child maltreatment: a systematic review. Pediatr Res 89 , 269–274 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01175-x

Download citation

Received : 30 June 2020

Revised : 09 September 2020

Accepted : 10 September 2020

Published : 25 September 2020

Issue Date : January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01175-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Child and caregiver reporting on child maltreatment and mental health in the philippines before and after an international child development program (icdp) parenting intervention.

- Emil Graff Ramsli

- Ane-Marthe Solheim Skar

- Ingunn Marie S. Engebretsen

Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma (2023)

Taking Stock of Canadian Population-Based Data Sources to Study Child Maltreatment: What’s Available, What Should Researchers Know, and What are the Gaps?

- Danielle Bader

- Kristyn Frank

- Dafna Kohen

Child Indicators Research (2023)

Socioeconomic Factors and Pediatric Injury

- Stephen Trinidad

- Meera Kotagal

Current Trauma Reports (2023)

FAST: A Framework to Assess Speed of Translation of Health Innovations to Practice and Policy

- Enola Proctor

- Alex T. Ramsey

- Ross C. Brownson

Global Implementation Research and Applications (2022)

Playing to Succeed: The Impact of Extracurricular Activity Participation on Academic Achievement for Youth Involved with the Child Welfare System

- Sarah E. Connelly

- Erin J. Maher

- Angela B. Pharris

Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal (2022)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2021

Child maltreatment, cognitive functions and the mediating role of mental health problems among maltreated children and adolescents in Uganda

- Herbert E. Ainamani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7290-7232 1 , 2 ,

- Godfrey Z. Rukundo 3 ,

- Timothy Nduhukire 4 ,

- Eunice Ndyareba 5 &

- Tobias Hecker 6

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health volume 15 , Article number: 22 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

5769 Accesses

14 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

Child maltreatment poses high risks to the mental health and cognitive functioning of children not only in childhood but also in later life. However, it remains unclear whether child maltreatment is directly associated with impaired cognitive functioning or whether this link is mediated by mental health problems. Our study aimed at examining this research question among children and adolescents in Uganda.

A sample of 232 school-going children and adolescents with a mean age of 14.03 ( SD = 3.25) was assessed on multiple forms of maltreatment using the Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology Exposure—Pediatric Version (pediMACE). Executive functions were assessed by the Tower of London task and working memory by the Corsi Block Tapping task, while mental health problems were assessed using the Child PTSD Symptom Scale for PTSD and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC).

In total, 232 (100%) of the participant reported to have experienced at least one type of maltreatment in their lifetime including emotional, physical, and sexual violence as well as neglect. We found a negative association between child maltreatment and executive functions (β = − 0.487, p < 0.001) and working memory (β = − 0.242, p = 0.001). Mental health problems did not mediate this relationship.

Conclusions

Child maltreatment seems to be related to lower working memory and executive functioning of affected children and adolescents even after controlling for potential cofounders. Our study indicates that child maltreatment the affects children’s cognitive functionality beyond health and well-being.

Child maltreatment which is defined as any act of abuse or neglect by a parent, caregiver or a community member that results in harm, potential harm, or threat of harm to a child has been remarked as one of the greatest global public health concerns [ 1 ]. Child maltreatment may include, emotional, physical, and sexual violence as well as neglect [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Estimates on the prevalence of violence against children in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) show that a minimum of 50% of children in Asia and Africa between the ages of 2 and17 experience violence in their upbringing [ 4 ]. Various studies in Africa have shown that there is high level of child abuse in varying samples of children and adults [ 5 ]. Child maltreatment, has also been documented in East-African families, e.g., in Tanzania more than 90% of the children reported to have experienced violent discipline by parents [ 6 ] and different forms of maltreatments by teachers [ 7 ].While in Kenya, severe forms of child sexual abuse was reported [ 8 ] with key perpetrators being relatives (29%).

Similarly, studies in Uganda have reported that children and adolescents experienced violence very frequently [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. For example, physical and emotional violence have been experienced by 98% of children, sexual violence by 76% and economic violence by 74% [ 10 ].

Child maltreatment does not only inflict physical pain on the affected children but also poses a major risk to cognitive impairment in both childhood and adulthood [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. In support of the above findings, the toxic stress theory implicates exposure to early childhood adversity for altering the neuro-endocrinal immune system, which renders individual vulnerability to all forms of functional impairments and disease [ 15 ]. A systematic review of cognitive function after childhood trauma concluded that cognitive abnormalities may be linked to neuro-psychological and neurological impacts [ 16 ]. Studies with both animals and humans show that exposure to adverse experiences in early life affects brain regulation and endocrine responses to stress [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. In fact, a number of studies on neuropsychological impairments have observed a significant disruption in prefrontal cortex that plays an important role in executive functioning following exposure to trauma and subsequent PTSD diagnosis [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. Moreover, previous studies have documented how exposure to continuous stress affects hippocampal volume resulting from constant increase in glucocorticoid hormone which is released as the brain seeks to mitigate negative effects of stress. Stress in turn seems to affect the functionality of human memory and learning [ 18 , 26 , 27 , 28 ].

Therefore, it is not surprising that a systematic review on the impact of child maltreatment on later cognitive functions reported that children with experiences of child maltreatment performed poorly on tasks of working memory, attention, episodic memory and executive functions [ 29 ]. In line with these findings, other studies mostly from high income countries showed that as a consequence of adverse childhood experiences many affected children and adolescents suffer from cognitive deficiencies [ 25 , 30 , 31 ]. For example, child abuse was found to be associated with delayed language development, cognitive development, and a lower intelligence quotient [ 12 , 32 ]. A systematic review indicated that maltreated children performed poorly on tasks requiring executive functions, working memory and attention [ 33 ].

In addition to the high risk of cognitive impairment associated with child maltreatment, studies in high income countries have also found a strong association between maltreatment and mental health problems [ 34 , 35 , 36 ]. Others have repeatedly found links between maltreatment, PTSD, depression, impairments of prefrontal cortex functioning and dysregulation of HPA [ 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. Furthermore, a negative effect of PTSD symptoms severity on cognitive functions but not trauma, has been frequently reported [ 24 , 41 , 42 ].

The described association between maltreatment and impaired cognitive functioning, maltreatment and mental health problems, as well as mental health problems and impaired cognitive functioning raise the question whether the association between child maltreatment and cognitive functions may be mediated by mental health problems [ 12 , 43 ]. A review of maltreatment studies recommended further studies that control for the mediation effect of psychiatric co-morbidities [ 32 ]. In line with this recommendation and other previous findings, it remains unclear whether child maltreatment is directly associated with impaired cognitive functioning or whether this link is mediated by mental health problems. Moreover, most of the studies testing this link have been conducted in high income-countries. Only one study in Tanzania showed that the relation between child maltreatment and cognitive functioning was mediated by internalizing mental health problems. The other existing studies in low- and middle-income countries, in which violence against and maltreatment of children is much more common, have either examined cognitive impairment among people living with HIV [ 44 , 45 , 46 ], refugees [ 41 ] and the elderly [ 47 ] but not among children and adolescents with a history of maltreatment.

To close this gap, our study sought to examine the relationship between child maltreatment and cognitive functioning (working memory and executive functions) and the mediating role of mental health problems (PTSD symptom severity and depressive symptoms) among maltreated children and adolescents in Southwestern Uganda. We hypothesized that child maltreatment would be negatively correlated with (a) working memory and (b) executive functions, and (c) that these relations would be mediated by mental health problems.

Participants

In total, 232 children and adolescents (52% male) with a mean age of 15 years ( SD = 2.95) participated in our study. Overall, boys were older than girls and the majority ( n = 145, 63%) attended primary school (Table 1 ). In total, 101 (44%) participants were living with their mothers as primary caregivers, 40 (17%) were under the primary care of their grandparents, 21 (9%) were primarily cared for by their fathers and 21(9%) were cared for by their siblings, while 30 (13%) indicated other relatives as their main primary caregivers. Only 19 (8%) participants were cared for by another person. Overall, 103 (44%) participants reported to have lived in more than two families in their lifetime.

Study setting and design

This was a cross-sectional study in which 232 children and adolescents between the ages of 8 to 18 studying at two primary schools and one secondary school located in the districts of Mbarara and Rubanda in Southwestern Uganda. The three schools were chosen because they were mainly supported by nonprofit organizations and were expected to have enrolled at-risk children in terms of maltreatment experiences. On average, the enrollment per each school was at 300 (n = 900) children with a total number of 305 children recorded as the most at risk of child maltreatment. Southwestern Uganda is mainly inhabited by Bantu and Nile Hamites ethnic groups. Most residents live in rural areas, where the local economy is primarily characterized by subsistence economy with high levels of food and water insecurity [ 48 , 49 ].

Recruitment and sampling procedure

Data were collected between June 2018 and May 2019. The social workers within the schools helped to locate children and adolescents with a known history of maltreatment in their schools. Only children below the ages of 18 were recruited. We interviewed all children that were identified by the school social workers until there were no more potential participants. Two counsellors and one psychologist conducted the interviews.

The interviewers went through 1-week training in the psychological assessment and practiced the assessment in joint interviews to accomplish high inter-rater reliability. Generally, each interview took 45–60 min in a private setting within the school premises.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Mbarara University of Science and Technology Research Ethics Committee (MUST-REC) under approval number 07/02-18 and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNSCT) under approval number SS 4928.

Additionally, we sought permission from the school Head Teachers who introduced us to the school social workers. Before the interviews, information on the content, procedures, risks, the right to withdraw, and confidentiality were explained to the participants. Written informed consent (signature or fingerprints) of the legal guardian were obtained. In addition, children and adolescents provided their assent before participating in the study. Each family received two bars of soap as a token of appreciation for taking part in the study. Children with severe symptoms of mental health problems were referred to the nearest health facilities for specialized psychological treatment.

All instruments were translated into Runyankole-Rukiga and back translated to English in a blind written form to ensure the original meaning was not lost. Face to face interviews included socio-demographic information, such as age, gender, educational level and having stayed in two or more homes.

- Child maltreatment

Child maltreatment and other adversities encountered at home were assessed using the Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology of Exposure—Pediatric Version (pediMACE). This tool was the child-appropriate version of the Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology of Exposure [ 50 ]. The pediMACE consists of 45 dichotomous (yes/no) questions, measuring witnessed or self-experienced forms of childhood maltreatment throughout one’s lifetime. We summed up all the questions to a total child maltreatment score (possible range: 0 to 45) that was subsequently used in the analysis.

Exposure to traumatic events

Exposure to traumatic events was assessed using a 15-item checklist on the revised version of the Child PTSD Symptoms Scale for DSM-5—Self-Report (CPSS-VSR) [ 51 ]. With response to yes or no, children were assessed on their exposure to severe natural disasters, severe accidents, being robbed or threatened, being slapped or knifed, seeing relative being beaten or slapped and many others. The scale provides the participants with an opportunity to mention any other traumatizing event that could have been experienced. We summed up all the 15 items to come with a total score that was subsequently used in the analysis.

Mental health problems

We used the CPSS-VSR also to assess the PTSD symptoms severity [ 51 ]. This is a 20-item scale that assesses the occurrence and frequency of PTSD symptoms in relation to the most distressing event experienced by an individual. Participants were asked to rate the frequencies of listed symptoms during the previous 2 weeks on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all/only once) to 4 (almost every week). A total sum score was calculated. A cut off score of 31 indicated a probable PTSD diagnosis [ 52 ]. This scale has good psychometric measures and showed good psychometric properties, e.g. a Cronbach alpha of 0.92 and test retest reliability of r = 0.93 [ 53 ]. In the current study the Cronbach alpha was 0.86.

Furthermore, we assessed for depressive symptoms using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC) [ 54 ]. This is a 20-item self-report depression inventory with total scores ranging from 0 to 60. Each response to an item is scored as: 0 = “Not at All” 1 = “A Little” 2 = “Some” 3 = “A Lot”. Items 4, 8, 12, and 16 are phrased positively, and thus were inverted prior to the calculation of the total score. Higher CES-DC scores indicate higher levels of depression. Scores above 15 have been suggested to indicate significant depressive symptoms in children and adolescents [ 55 ]. However, in this study, we used an adopted cut-off score [ 56 ]. Owing to the cultural context in East Africa, the authors set the cut-off point of probable depression at > 30 [ 53 ]. In the Rwandan study, CES-DC was validated and showed good psychometric properties: Cronbach alpha of 0.86 and test–retest reliability of r = 0.85. In the current study, the Cronbach alpha was 0.87.

Working memory capacity

Corsi-block tapping (CBT) task was used to assess working memory. This neuropsychological test, which has been widely used as a measure of spatial memory in both clinical and experimental contexts for several decades and comes with good psychometric properties shown in validation studies [ 57 , 58 ]. It has also been successfully used in studies within the Great Lakes Region in Central Africa [ 7 , 41 ].The task requires participants to reproduce block-tapping sequences of increasing length in the same or in the reversed order and provides an index of working memory capacity. The Corsi apparatus consisted of nine 2.25 cm 3 black, wooden blocks fixed to a 27.5 cm × 22.8 cm grey, wooden board. The blocks were placed as described in the original test developed by Corsi [ 58 , 59 ]. Each cube was numbered on one side so that the numbers were visible to the interviewer but not to the participant. The participant was seated in front of the interviewer, who subsequently tapped the blocks starting with a sequence of three blocks. Three trials were given per block sequence of the same length. The blocks were touched with the index finger at a rate of approximately one block per second with no pauses between the individual blocks. In the first application of the test after the first half of the interview, the participant had to tap the block sequences in the same order immediately after the interviewer was finished. In the second application at the end of the interview, the participants had to tap the block sequence in reversed order. We computed a total score for both applications (same order and reversed order) by adding the number of correctly repeated sequences until the test was discontinued (i.e., the number of correct trials). The total score ranged from 0 to 21. High performance implied higher working memory capacity.

Executive functions

The Tower of London (TOL) assessed executive functions. The TOL is a classic neuropsychological test for the assessment of executive functions that include planning and problem-solving skills, which has been widely used in diverse cultures [ 41 , 60 , 61 ].

The validation study revealed sound psychometric properties [ 61 ]. The TOL consisted of three wooden pegs, which were fixed on a block of wood and three wooden balls of different colors (black, grey and white) that were placed on the pegs and moved from one peg to another. The participants were shown 12 pictures which depicted the TOL with the balls being placed in different positions on the pegs and were asked to arrange the balls to match the positions on the picture. Each trial started from the same starting positions and varied in difficulty due to the number of moves that were allowed to arrange the balls to match the picture (from two to five). Three attempts were granted for each problem. For each problem up to three points could be earned (if successful in the first attempt). The total sum scores ranged from 0 to 36. Higher grades would mean better performance.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 23 for Mac. Descriptive statistics were used to compute demographic variables for participants. We z-standardized the two sum scores of PTSD and depressive symptoms severity to compute a mental health problem composite score. Linear regression models were used to test for the association between maltreatment (predictor variable) and the outcome variables of working memory and executive functions. Furthermore, we conducted a simple mediation analysis within the set mediation assumptions that (a) the independent variable would be significantly associated with the dependent variable, (b) the independent variable would be significantly associated with the mediator, and (c) the mediator would be significantly associated with the dependent variable while controlling for the independent variable [ 62 ]. These procedures were followed through the analysis process to estimate the mediating role of mental health problems (mediator variable) on the relationship between child maltreatment and the cognitive domains of working memory and executive functions while controlling for age, years of education and trauma load. As test statistic for the mediating role, we used the Sobel test and non-parametric approach of 5000 bootstraps [ 63 ]. All models fulfilled the necessary quality criteria for linear regression analysis. The residuals did not deviate significantly from normality, linearity or homoscedasticity and no univariate outliers could be identified. The maximum variance inflation factor did not exceed 1.52. Hence, we did not need to take multicollinearity into consideration.

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for the main study variables. Overall, 232 (100%) of the participant reported to have experienced at least one type of maltreatment in their lifetime. Female participants experienced more maltreatment types than their male counterparts (see Table 1 ). For example, the majority of participants endorsed having been intentionally pushed by an authority figure (89.7%, n = 208), 89.2% (n = 207) reported having felt that their feelings were not understood by family members. In total, 37.5% of the girls (n = 45,) and 5.4% of the boys (n = 6) indicated that they had been touched in a sexual way (see Additional file 1 : Table S1 for more details). The prevalence of PTSD and depression within our sample was 60% (n = 140) and 39% (n = 91), respectively.

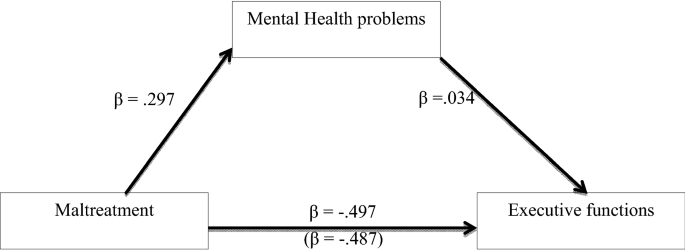

Associations between maltreatment, mental health problems, and executive functions

In a regression model with maltreatment as an explanatory variable and executive functions as the outcome variable while controlling for participant’s age, education in years and trauma load, we found a significant association between maltreatment and executive functions (see Table 2 and Fig. 1 ). The regression model explained 20% of the variability in executive functions. In addition, trauma load and maltreatment significantly correlated with mental health problems (see Table 2 and Fig. 1 ). This model explained 26% of the variance of mental health problems. To investigate whether the association between maltreatment and executive functions was mediated by mental health problems, we conducted a simple mediation analysis with maltreatment as an independent variable and executive functions as dependent variable (Fig. 1 ). When the composite score of mental health problems was added as a mediator variable, the indirect effect of child maltreatment via mental health problems was not significant (see Table 2 , Bootstrap results: B = 0.011, SE = 0.023, 95% CI − 0.036, 0.059).

Mediated regression model ( N = 232) exploring the mediating influence of mental health problems on the relation between child maltreatment and executive functions. This model indicates that the mental health problems did not mediate the association between child maltreatment and executive functions

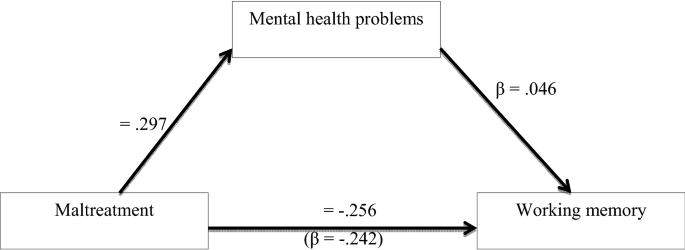

Associations between maltreatment, mental health, and working memory

After controlling for age, years of education, and trauma load, maltreatment was significantly associated with working memory (Table 3 and Fig. 2 ). The regression model explained 4% of the variability in working memory. Furthermore, maltreatment and trauma load were significantly associated with mental health problems (Table 3 and Fig. 2 ). The regression model explained 26% of the variations of mental health problems. To investigate whether the association between maltreatment and working memory is mediated by mental health problems, we conducted a simple mediation analysis with maltreatment as independent variable, working memory as dependent variable (Fig. 2 ). When the mental health composite score was added as a mediator variable, the indirect effect of child maltreatment via mental health problems was not significant (see Table 3 , Bootstrap results: B = 0.005, SE = 0.008, 95% CI − 0.010, 0.021).

Mediated regression model ( N = 232) exploring the mediating influence of mental health problems on the relation between child maltreatment and working memory. This model indicates that mental health problems did not mediate the association between child maltreatment and working memory

In this study, we aimed at examining the association between child maltreatment and the cognitive domains of executive functions and working memory as well as the mediating role of mental health problems in a sample of maltreated children and adolescents in Southwestern Uganda. In line with our hypothesis (a) and (b), we found a negative relationship between child maltreatment and both domains of cognitive functioning after controlling for potential influences, such as age, education, and trauma load. However, in contrast to our hypothesis (c), we did not find an indirect effect via mental health problems.

The finding that child maltreatment was negatively associated with executive functions is in line with previous studies suggesting impairments in executive functions among individuals exposed to child maltreatment [ 29 , 64 , 65 , 66 ]. Furthermore, we found a negative association between child maltreatment and working memory. This observation is also in line with previous findings that found a negative association between child maltreatment and executive functions [ 13 , 67 , 68 , 69 ]. A possible explanation for these negative associations could be the toxic stress theory that implicates exposure to early childhood adversity in altering the neuro-endocrinal immune system, which renders individuals vulnerable to all forms of functional impairments and disease [ 15 , 18 ]. For example, children who have experienced harsh punishments and other forms of maltreatment performed poorly on indicators of self-regulation and other cognitive domains [ 7 , 70 , 71 ]. Differences between maltreated children and non-maltreated children can also be seen in children’s physiology, stress response pathways and cortisol levels [ 72 , 73 ]. With exposure to high levels of maltreatment in our sample, high levels of stress may have negatively impacted hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex functioning. Dense concentration of cortisol receptors in specific brain areas are a possible explanation of cognitive dysfunctioining e.g., in the domains of working memory and executive functions [ 18 , 19 , 74 ]. Based on our own findings and the existing evidence base, including a systematic review [ 29 ], we may conclude that children and adolescents exposed to child maltreatment have a higher likelihood of performing poorly on tasks assessing working memory and executive functions. Our findings therefore lend further support to previous research that children exposed to maltreatment risk impairment in cognitive functions [ 14 , 29 ]. However, it is important to note that most studies on cognitive impairment in individuals exposed to maltreatment are based on cross-sectional data [ 12 , 69 , 75 , 76 ]. Therefore, it remains unclear in literature whether maltreatment leads to poor cognitive functions, whether it co-occurs or whether poor functions increase the risk for maltreatment. Future research should focus on longitudinal, prospective, and experimental studies. For example, randomized controlled studies that implement preventative intervention approaches that reduce maltreatment would offer a unique opportunity to test for causal relations [ 6 ].

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find an indirect effect of child maltreatment via mental health problems on cognitive functions. Although our results are partially in line with one study that also did not find an indirect effect of child maltreatment via PTSD on cognitive functions [ 12 ], most studies in high income countries compared individuals with and without mental health problems after trauma exposure [ 77 , 78 ], while others especially in Africa examined the direct association between mental health problems and cognitive functions [ 7 , 41 ]. Overall, the current evidence suggests that mental health problems seem to be linked with poor performance in cognitive functioning [ 79 ]. In our sample, we could not replicate this finding. Our findings, on the other hand, suggest that it is not the mental health problems but the exposure to maltreatment that is linked to poor performance. As most of the above-mentioned studies did not include maltreatment in their analysis, the question remains whether the found associations would hold when including maltreatment in their analysis. However, it is important to consider that our sample was composed of children and adolescents exposed to severe child maltreatment and the found associations may be specific for severely maltreated children. For example, potential effects on the stress response axis may have played a more prominent role [ 31 , 74 ]. Due to the limitation of our cross sectional design further research in Africa and Uganda examining the interplay between child maltreatment, mental health problems, and cognitive functions is needed to fully understand the causal mechanisms that lead to cognitive impairments.

Strength and limitations

Our study examined the relationship between child maltreatment and cognitive functioning and the mediating role of mental health problems among maltreated children and adolescents in Southwestern Uganda. To our knowledge, this is one of the few studies in Africa and other LAMICs that has assessed the mediating role of mental health on child maltreatment and cognitive functions among a sample of maltreated children. Despite our study’s strength, some limitations should be noted: first, the convenience sample does not allow generalizing our findings beyond our specific sample. Secondly, the cross-sectional nature of our study design does not allow us to draw any conclusions about the directionality of our findings. We recommend prospective and experimental studies to shed light on the causal relations. Thirdly, our sample consists of at-risk children. This also limits the possibility to generalize our findings to the general population of children and adolescents. Lastly, it is important to note that biases such as social desirability can never be completely ruled out for subjective reports.

Our findings therefore provide further support to earlier findings, especially from high income countries, that child maltreatment is associated with poor cognitive functioning. Similarly, based on our findings, we advocate for preventive measures to protect children in Uganda and Africa from violence and maltreatment. Programs aimed at equipping parents, caregivers, and teachers with none violent competencies while interacting with children are highly needed in societies where violence against children is still socially accepted. Based on our findings, we advocate for preventing child maltreatment within schools and families to enable more children in Uganda to grow up in a secure environment and to ensure their healthy development. Future studies in Africa should investigate differential associations and consequences of different types of maltreatment on mental health and cognitive functions.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

Post traumatic stress disorder

Low- and middle-income countries

Gilbert R, et al. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):68–81.

Article Google Scholar

Afifi TO, et al. Substantiated reports of child maltreatment from the Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect 2008: examining child and household characteristics and child functional impairment. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(7):315–23.

Leeb RT, Fluke JD. Child maltreatment surveillance: enumeration, monitoring, evaluation and insight. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can Res Policy Pract. 2015;35(8–9):138–40.

Google Scholar

Hillis S, et al. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: a systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20154079.

Meinck F, et al. Risk and protective factors for physical and sexual abuse of children and adolescents in Africa: a review and implications for practice. Trauma Violence Abus. 2015;16(1):81–107.

Nkuba M, Hermenau K, Hecker T. Violence and maltreatment in Tanzanian families—findings from a nationally representative sample of secondary school students and their parents. Child Abus Negl. 2018;77:110–20.

Hecker T, et al. Harsh discipline relates to internalizing problems and cognitive functioning: findings from a cross-sectional study with school children in Tanzania. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):118.

Mwangi MW, et al. Perpetrators and context of child sexual abuse in Kenya. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;44:46–55.

Child J, et al. Responding to abuse: children’s experiences of child protection in a central district, Uganda. Child Abus Negl. 2014;38:1647–58.

Naker D. Violence against children: the voices of Ugandan children and adults. Kampala, Uganda: Raising voices: save the children in Uganda; 2005.

Ssenyonga J, Muwonge CM, Hecker T. Prevalence of family violence and mental health and their relation to peer victimization: a representative study of adolescent students in southwestern Uganda. Child Abus Negl. 2019;98:104194.

Nikulina V, Widom CS. Child maltreatment and executive functioning in middle adulthood: a prospective examination. Neuropsychology. 2013;27(4):417–27.

Majer M, et al. Association of childhood trauma with cognitive function in healthy adults: a pilot study. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:61.

Tran NK, et al. The association between child maltreatment and emotional, cognitive, and physical health functioning in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):332.

Johnson SB, et al. The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):319–27.

Aas M, et al. A systematic review of cognitive function in first-episode psychosis, including a discussion on childhood trauma, stress, and inflammation. Front Psychiatry. 2014;4:182.

Lupien SJ, et al. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):434–45.

Lupien SJ, et al. The effects of stress and stress hormones on human cognition: implications for the field of brain and cognition. Brain Cogn. 2007;65(3):209–37.

Yuen EY, et al. Repeated stress causes cognitive impairment by suppressing glutamate receptor expression and function in prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2012;73(5):962–77.

Engdahl B, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder: a right temporal lobe syndrome? J Neural Eng. 2010;7(6):066005.

Hayes JP, et al. Reduced hippocampal and amygdala activity predicts memory distortions for trauma reminders in combat-related PTSD. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(5):660–9.

Stein MB, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a twin study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1675–81.

Unterrainer J, Owen A. Planning and problem solving: from neuropsychology to functional neuroimaging. J Physiol. 2006;99:308–17.

Stein MB, Kennedy CM, Twamley EW. Neuropsychological function in female victims of intimate partner violence with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(11):1079–88.

Stein MB, et al. Hippocampal volume in women victimized by childhood sexual abuse. Psychol Med. 1997;27(4):951–9.

Heim C, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(1 Suppl 1):13–24.

Gilbertson MW, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(11):1242–7.

Heim C, et al. The link between childhood trauma and depression: insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(6):693–710.

Irigaray T, et al. Child maltreatment and later cognitive functioning: a systematic review. Psicologia Reflexão e Cr’itica. 2013;26:376–87.

Royall DR, et al. Executive control function: a review of its promise and challenges for clinical research. A report from the Committee on Research of the American Neuropsychiatric Association. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;14(4):377–405.

Teicher MH, et al. The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function and connectivity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17(10):652–66.

Hart H, Rubia K. Neuroimaging of child abuse: a critical review. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:52.

Augusti EM, Melinder A. Maltreatment is associated with specific impairments in executive functions: a pilot study. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(6):780–3.

Kisely S, et al. Child maltreatment and mental health problems in adulthood: birth cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213(6):698–703.

Vranceanu A-M, Hobfoll SE, Johnson RJ. Child multi-type maltreatment and associated depression and PTSD symptoms: the role of social support and stress. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31(1):71–84.

Raabe FJ, Spengler D. Epigenetic risk factors in PTSD and depression. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:80–80.

Richert KA, et al. Regional differences of the prefrontal cortex in pediatric PTSD: an MRI study. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23(1):17–25.

Shea A, et al. Child maltreatment and HPA axis dysregulation: relationship to major depressive disorder and post traumatic stress disorder in females. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(2):162–78.

Yehuda R. Biology of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 17):41–6.

Gonzalez A. The impact of childhood maltreatment on biological systems: implications for clinical interventions. Paediatr Child Health. 2013;18(8):415–8.

Ainamani HE, et al. PTSD symptom severity relates to cognitive and psycho-social dysfunctioning—a study with Congolese refugees in Uganda. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(1):1283086.

Schmidt M. Rey auditory verbal learning test: RAVLT: a handbook. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1996.

Carvalho JCN, et al. Cognitive, neurobiological and psychopathological alterations associated with child maltreatment: a review of systematic reviews. Child Indic Res. 2016;9(2):389–406.

Namagga JK, Rukundo GZ, Voss JG. Prevalence and risk factors of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in rural southwestern Uganda. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2019;30(5):531–8.

Sacktor N, et al. HIV-associated cognitive impairment in sub-Saharan Africa—the potential effect of clade diversity. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3(8):436–43.

Nakasujja N, et al. Depression symptoms and cognitive function among individuals with advanced HIV infection initiating HAART in Uganda. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):44.

Mubangizi V, et al. Prevalence and correlates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in rural Uganda: cross-sectional, population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):48.

Tsai AC, et al. Population-based study of intra-household gender differences in water insecurity: reliability and validity of a survey instrument for use in rural Uganda. J Water Health. 2016;14(2):280–92.

Tsai AC, et al. Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(12):2012–9.

Teicher MH, Parigger A. The ‘maltreatment and abuse chronology of exposure’ (MACE) scale for the retrospective assessment of abuse and neglect during development. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0117423.

Foa EB, et al. Psychometrics of the child PTSD symptom scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47(1):38–46.

Foa E, et al. Psychometrics of the child PTSD symptom scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;47:1–9.

Qi J, et al. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among adolescents over 1 year after the Jiuzhaigou earthquake. J Affect Disord. 2020;261:1–8.

Faulstich ME, et al. Assessment of depression in childhood and adolescence: an evaluation of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale for children (CES-DC). Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(8):1024–7.

Costello EJ, Angold A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: checklists, screens, and nets. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27(6):726–37.

Betancourt T, et al. Validating the center for epidemiological studies depression scale for children in Rwanda. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1284–92.

Berch DB, Krikorian R, Huha EM. The Corsi block-tapping task: methodological and theoretical considerations. Brain Cogn. 1998;38(3):317–38.

Kessels RP, et al. The Corsi block-tapping task: standardization and normative data. Appl Neuropsychol. 2000;7(4):252–8.