- IAS Preparation

- NCERT Notes for UPSC

- NCERT Notes Post Mauryan India Satavahanas

Satavahana Dynasty - Important Rulers of Satavahana Empire [UPSC History Notes]

The reign of the Satavahana Dynasty began in the mid-1st century BCE and came to an end in the early 3rd century CE. The area of the Satavahana Dynasty is debated where some historians argue that the Satavahanas initially established their hold over the area around Pratishthana (modern Paithan) in the western Deccan, and expanded from there into the eastern Deccan, Andhra, and the western coast. The topic is important for Ancient History preparation in the IAS Exam . Read on to know about the Satavahana empire, its rulers and coinage for UPSC preparation.

Satavahana Dynasty:- Download PDF Here

Satavahana Dynasty [Origin & Development]

The Sunga dynasty came to an end around 73 BCE when their ruler Devabhuti was killed by Vasudeva Kanva. The Kanva dynasty then ruled over Magadha for about 45 years. Around this time, another powerful dynasty, the Satavahanas came to power in the Deccan area.

The term “Satvahana” originated from the Prakrit which means ” driven by seven” which is an implication of the Sun God’s chariot that is driven by seven horses as per Hindu mythology.

The first king of the Satavahana dynasty was Simuka . Before the emergence of the Satavahana dynasty, a brief history of the other dynasties is mentioned below:

Facts about Satavahana Dynasty

In the northern region, the Mauryas were succeeded by the Sungas and the Kanvas . However, the Satavahanas (natives) succeeded the Mauryas in Deccan and in Central India .

- It is believed that after the decline of the Mauryas and before the advent of the Satavahans, there must have been numerous small political principalities that were ruling in different parts of the Deccan (for about 100 years).

- Probably the Rathikas and the Bhojikas that have been mentioned in the Ashokan inscriptions gradually progressed into the Maharathis and Mahabhojas of pre-Satavahana times.

- The Satavahanas are considered to be identical to the Andhras who are mentioned in the Puranas , but neither the name Andhra appears in the Satavahana inscriptions nor do the Puranas mention the Satavahanas.

- According to some Puranas, the Andhras ruled for 300 years and this period is assigned to the rule of the Satavahana dynasty, with their capital at Pratishthana (modern Paithan) on the Godavari in Aurangabad district .

- The Satavahana kingdom majorly comprised present-day Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Telangana . At times, their rule also included parts of Gujarat, Karnataka as well as Madhya Pradesh.

- The kingdom had different capitals at different times. Two of the capitals were Amaravati and Pratishthana (Paithan).

- The earliest inscriptions of the Satavahans belong to the first century BCE when they defeated the Kanvas and established their power in parts of Central India.

- It is important to mention that the early Satavahana kings appeared not in Andhra but in Maharashtra, where most of their early inscriptions have been found. Gradually they extended their power over Karnataka and Andhra.

- Their greatest competitors were the Shaka Kshatrapas of western India, who had established themselves in the upper Deccan and western India.

- The Satavahans were Brahmanas and worshipped gods like Vasudeva Krishna.

- The Satavahans kings used matronyms like Gautamiputra and Vaishishthiputra, although they were not matriarchal or matrilineal in any sense.

- They assumed the title of Dakshinapatha Pati (Lord of Dakshinapatha) .

- The Satavahanas are known for starting the practice of giving royal grants of land to Brahmans and Buddhist monks.

- Simuka was the founder of the Satavahana Dynasty.

- The Satavahanas were the first native Indian kings to have issued their own coins which had the rulers’ portraits on them. Gautamiputra Satakarni started this practice which he imbibed from the Western Satraps after vanquishing them.

- The coin legends were in Prakrit . Some reverse coin legends are in Tamil, Telugu and Kannada also.

- They patronised Prakrit more than Sanskrit.

- Even though the rulers were Hindus and claimed Brahmanical status, they supported Buddhism also.

- They were successful in defending their areas from foreign invaders and had many battles with the Sakas .

The Satavahana Dynasty map is given below:

Important Rulers of the Satavahana Dynasty

- Considered to be the founder of the Satavahana dynasty and was immediately active after Ashoka’s death.

- Built Jain and Buddhist temples.

Satakarni I (70- 60 BC)

- Satakarni I was the 3rd king of the Satavahanas.

- Satakarni I was the first Satavahana king to expand his empire by military conquests.

- He conquered Kalinga after the death of Kharavela.

- He also pushed back the Sungas in Pataliputra.

- He also ruled over Madhya Pradesh.

- After annexing the Godavari Valley, he assumed the title of ‘Lord of Dakshinapatha’.

- His queen Nayanika wrote the Naneghat inscription which describes the king as Dakshinapathapati.

- He performed Ashvamedha and revived Vedic Brahmanism in the Deccan.

- King Hala compiled the Gatha Saptashati. Called Gaha Sattasai in Prakrit, it is a collection of poems with mostly love as the theme. Around forty of the poems are attributed to Hala himself.

- Hala’s minister Gunadhya composed Brihatkatha.

Gautamiputra Satakarni of Satavahana Dynasty (106 – 130 AD or 86 – 110 AD)

- He is considered the greatest king of the Satavahana dynasty.

- It is believed that at one stage, the Satavahanas were dispossessed of their dominions in the upper Deccan and western India. The fortunes of the Satavahanas were restored by Gautamiputra Satkarni. He called himself the only Brahmana who defeated the Shakas and destroyed many Kshatriya rulers.

- He is believed to have destroyed the Kshaharata lineage to which his adversary Nahapana belonged. More than 800 silver coins of Nahapana (found near Nasik) bear marks of being restruck by the Satavahana king. Nahapana was an important king of the Western Satraps.

- His kingdom ran from Krishna in the south to Malwa and Saurashtra in the north and from Berar in the east to the Konkan in the west.

- In a Nasik inscription of his mother Gautami Balashri, he is described as the destroyer of the Shakas, Pahlavas and the Yavanas (Greeks); as the uprooter of the Kshaharatas and the restorer of the glory of the Satavahanas. He is also described as Ekabrahmana (a peerless Brahmana) and Khatiya-dapa-manamada (destroyer of the pride of Kshatriyas).

- He was given the titles of Rajaraja and Maharaja .

- He donated land to the Buddhist monks. The Karle inscription mentions the grant of Karajika village, near Pune, Maharashtra.

- In the later part of his reign, he probably lost some of the conquered Kshaharata territories to the Kardamaka line of the Shaka Kshatrapas of western India, as is mentioned in the Junagadh inscription of Rudradaman Ⅰ.

- His mother was Gautami Balasri and hence his name was Gautamiputra (son of Gautami).

- He was succeeded by his son Vasisthiputra Sri Pulamavi/Pulumavi or Pulamavi II. (Alternatively spelt Pulumayi.)

Vashishthiputra Pulumayi (c. 130 – 154 CE)

- He was the immediate successor of Gautamiputra. The coins and inscriptions of Vashishthiputra Pulumayi are found in Andhra.

- According to Junagadh inscriptions, he was married to the daughter of Rudradaman Ⅰ.

- The Shaka-Kshatrapas of western India recovered some of their territories due to his engagements in the east.

Yajna Sri Satakarni (c. 165 – 194 CE)

- One of the later kings of the Satavahana dynasty. He recovered north Kokan and Malwa from the Shaka rulers.

- He was a lover of trade and navigation, as is evident from the motif of a ship on his coins . His coins have been found in Andhra, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat.

Satavahana Dynasty Administration

The administration of the Satavahana dynasty was entirely based on the Shastras, and it had the following structure:

- Rajan or the king who was the ruler

- Princes or Rajas who had their names inscribed on coins

- Maharathis, who had the power of granting villages and also had the privilege of maintaining marital relations with the ruling family.

- Mahasenapati

- Mahatalavara

The inscription of the ruler Guatamipurna Satakarni throws some light on the bureaucratic structure of administration. However, clarity on the detailed structure is still awaited by historians.

Features of Satavahana Administration

- The king was represented as the upholder of dharma and he strove for the royal ideal set forth in the Dharmashastras. The Satavahana king is represented as possessing the divine qualities of ancient gods such as Rama, Bhima, Arjuna, etc.

- The Satavahanas retained some of the administrative units of Ashokan times. The kingdom was divided into districts called ahara . Their officials were known as A matyas and Mahamatras (same as in Mauryan times). But unlike in Mauryan times, certain military and feudal elements are found in the administration of the Satavahanas . For instance, the Senapati was appointed provincial governor . It was probably done to keep the tribal people in the Deccan who were not completely brahmanised under strong military control.

- The administration in the rural areas was placed in the hands of the gaulmika (village headman) who was also the head of a military regiment consisting of 9 chariots, 9 elephants, 25 horses and 45 foot soldiers.

- The military character of the Satavahana rule is also evident from the common use of terms like kataka and skandhavara in their inscriptions. These were military camps and settlements which served as administrative centres when the king was there. Thus, coercion played an important part in the Satavahana administration.

- The Satavahanas started the practice of granting tax-free villages to Brahmanas and Buddhist monks.

- The Satavahana kingdom had three grades of feudatories – Raja (who had the right to strike coins), Mahabhoja and Senapati.

Economy of Satavahana Empire

Agriculture was the backbone of the economy during the rule of the Satavahana kings. They also relied on trade and production of various commodities within and outside India.

Satavahana Coins

Some important points related to Satavahan coinage are mentioned below:

- The coins of the Satavahanas have been excavated from Deccan, western India, Vidarbha, Western and Eastern Ghats, etc.

- Most of the coins in the Satavahana dynasty were die-struck.

- Cast coins too existed in the Satavahana empire and there were multiple combinations of techniques that were used to cast coins.

- There were silver, copper, lead and potin coins in the Satavahana empire.

- The portrait coins were mostly in silver and some were in lead too. Dravidian language and Brahmi script were used on portrait coins.

- There were punch-marked coins too that were circulated alongside the Satavahana dynasty.

- The importance of maritime trade was derived from the images of ships present on the Satavahana coins.

- Many Satavahana coins bore the names of ‘Satakarni’ and ‘Pulumavi.’

- Satavahana coins were of different shapes – round, square, rectangular, etc.

- Chaitya symbol

- Chakra symbol

- Conch Shell symbol

- Lotus symbol

- Nandipada symbol

- Ship symbol

- Swastik symbol

- Animal motifs were found on the Satavahana coins.

Religion & Language of Satavahana Kingdom

The Satavahanas belonged to the Hindu religion and the Brahmanical caste. But, the interesting fact is their generosity towards other castes and religions which is evident from the donations made by them towards Buddhist monasteries. Many Buddhist monasteries were constructed during the rule of the Satavahana dynasty.

The official language of the Satavahanas was Prakrit, though the script was Brahmi (as was the case in the Ashokan times) . Political inscriptions also shed some light on the rare use of Sanskrit Literature.

Satavahanas – Material Culture

The material culture of the Deccan under the Satavahanas was a fusion of local elements (Deccan) and northern ingredients .

- The people of the Deccan were fairly acquainted with the use of iron and agriculture. The Satavahanas probably exploited the rich mineral resources of the Deccan such as iron ores from Karimnagar and Warangal and gold from Kolar fields. They mostly issued coins of lead, which is found on the Deccan and also coins of copper and bronze .

- The paddy transplantation was an art well known to the Satavahanas and the area between the Krishna and Godavari, especially at the mouth of the two rivers, formed a great rice bowl . The people of the Deccan also produced cotton. Thus a good portion of the Deccan developed a very advanced rural economy.

- The people of the Deccan learnt the use of coins, burnt bricks, ring wells, etc. through its contacts with the north. There was regular use of fire-baked bricks and use of flat, perforated roof tiles which must have added to the life of the structures . The drains were covered and underground to lead wastewater into soakage pits. The Andhra in the east Deccan included 30 walled towns, besides numerous villages.

Satavahanas – Social Organizations

- The Satavahanas originally seem to have been a tribe of the Deccan. They, however, were so brahmanized that they claimed to be Brahmanas. The most famous Satavahana king Gautamiputra claimed to be a Brahman and thought it his duty to uphold the four-fold varna system.

- Nagarjunakonda and Amravati in Andhra Pradesh and Nasik and Junar in Maharashtra became important Buddhist sites under the Satavahanas and their successors, the Ikshvakus.

- Merchants took pride in naming themselves after the towns to which they belonged.

- Among the artisans, the Gandhikas (perfumers) are mentioned as donors and later the term came to be used for all kinds of shopkeepers. The title ‘Gandhi’ is derived from the ancient term Gandhika.

- It was customary for their king to be named after his mother, (Gautamiputra and Vashishthiputra) which indicates that the women occupied an important position in the society .

Satavahana Architecture

In the Satavahana phase, many temples called chaityas and monasteries called viharas were cut out of the solid rock in the northwestern Deccan or Maharashtra with great precision and patience.

- The Karle chaitya is the most famous in western Deccan.

- The three viharas at Nasik carry inscriptions of Nahapana and Gautamiputra.

- The most important stupas of this period are Amravati and Nagarjunakonda. The Amaravati stupa is full of sculptures that depict the various scenes from the life of the Buddha. The Nagarjunakonda stupa contains Buddhist monuments and also the earliest Brahmanical brick temples.

The Decline of the Satavahanas

- Pulamavi IV is considered the last king of the main Satavahana line.

- He ruled until 225 AD. After his death, the empire fragmented into five smaller kingdoms.

Also Read | NCERT Notes: Decline of the Mauryan Empire

Frequently Asked Questions about the Satavahana Dynasty

Who was the most powerful king of the satavahana dynasty, who was the founder of the satavahana dynasty.

UPSC Preparation:

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

Pls give notes on sunga culture

Hi Please refer to the our page Sunga Dynasty to get the relevant details on it for IAS Exam.

IAS 2024 - Your dream can come true!

Download the ultimate guide to upsc cse preparation.

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

The Kushanas And The Satavahanas:

Que. how does the numismatic evidence of the period reflect the political and economic outlook of the kushanas and the satavahanas (ancient history, upsc cse-2016), introduction:.

Ans. Numismatic evidence, particularly coins, offers a unique lens to explore the political and economic landscapes of ancient Indian dynasties. This analysis focuses on the Kushanas and the Satavahanas, examining how their coins reveal not just economic transactions but also the ideological and strategic dimensions of governance during their respective reigns.

#1. Divine Portrayals and Political Legitimacy:

Kushana coins, notably those of Kanishka, often depicted the ruler in divine contexts, reinforcing the intertwining of political authority and religious symbolism. These portrayals aimed to legitimize the ruler’s power and present them as divinely endorsed leaders, fostering loyalty and obedience among the populace.

#2. Multicultural Scripts and Trade Networks:

The use of Greek, Kharoshthi, and Brahmi scripts on Kushana coins showcased the empire’s multicultural nature. Beyond linguistic diversity, this reflected economic integration and facilitated trade across diverse regions. The coins acted as linguistic bridges, promoting communication and trade within the expansive Kushana realm.

#3. Standardized Coinage and Economic Stability:

The introduction of the gold dinar under the Kushanas, notably during Kanishka’s reign, reflected a commitment to economic stability. Standardized coinage provided a reliable medium of exchange, fostering confidence in commercial transactions and contributing to overall economic prosperity within the Kushana Empire.

Satavahanas:

#1. prominent portraits and political assertion:.

Satavahana coins prominently featured royal portraits, emphasizing the centrality of royal authority. These images communicated the ruler’s political significance, projecting an assertive and confident stance to reinforce their position as the legitimate leaders of the Satavahana realm.

#2. Linguistic Diversity and Cultural Synthesis:

Satavahana coins exhibited linguistic diversity, incorporating Prakrit, Brahmi, and early Telugu scripts. This linguistic variety mirrored the cultural synthesis within the Satavahana domain, showcasing an ability to integrate diverse linguistic and cultural elements into the fabric of their political and economic administration.

#3. Maritime Symbols and Economic Strategies:

Symbols of maritime activities, such as ships and anchors, on Satavahana coins hinted at their engagement in maritime trade. This reflected an economic outlook that extended beyond land-based transactions, emphasizing the importance of coastal trade routes in the economic strategies of the Satavahanas.

Conclusion:

Numismatic evidence from the Kushana and Satavahana periods highlights their distinct political and economic outlooks. The Kushanas, exemplified by Kanishka’s divine portrayals and standardized coinage, showcased imperial power and economic stability. Conversely, the Satavahanas, with diverse linguistic symbols and maritime motifs, reflected cultural synthesis and adaptability in economic strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

#1. how did the kushana coins reflect divine authority and political legitimacy.

Ans. Kushana coins, especially under rulers like Kanishka, depicted divine imagery, showcasing a deliberate blending of political authority with religious symbolism. Examples include Kanishka’s portrayal in divine contexts, reinforcing his legitimacy by presenting him as a divinely endorsed leader.

#2. In what ways did the Kushana coins demonstrate multiculturalism and trade networks?

Ans. Kushana coins featured scripts in Greek, Kharoshthi, and Brahmi, reflecting a multicultural empire. This linguistic diversity facilitated communication and trade across diverse regions, exemplified by coins with inscriptions in various scripts, emphasizing economic integration and cross-cultural connections.

#3. How did the introduction of the gold dinar contribute to Kushana economic stability?

Ans. The Kushanas introduced the gold dinar, a standardized coin that fostered economic stability. This uniform currency instilled confidence in commercial transactions, contributing to overall economic prosperity within the Kushana Empire. Examples include the widespread use of the dinar in trade.

#4. What was the political significance conveyed by Satavahana royal portraits on coins?

Ans. Satavahana coins prominently featured royal portraits, emphasizing the political significance of the rulers. Examples include coins with assertive royal images, projecting the ruler’s authority and reinforcing their legitimacy as the leaders of the Satavahana realm.

#5. How did linguistic diversity on Satavahana coins reflect cultural synthesis?

Ans. Satavahana coins incorporated linguistic diversity with inscriptions in Prakrit, Brahmi, and early Telugu scripts. This diversity showcased a cultural synthesis within the Satavahana domain, exemplified by coins acting as linguistic bridges, fostering integration of diverse cultural elements within their political and economic administration.

#6. What role did maritime symbols play in Satavahana coins and economic strategies?

Ans. Satavahana coins featured maritime symbols like ships and anchors, indicating engagement in maritime trade. Examples include coins with these motifs, emphasizing an economic outlook extending beyond land-based transactions, highlighting the significance of coastal trade routes in their economic strategies.

#7. How did Satavahana coins assert dynastic claims and reinforce political lineage?

Ans. Satavahana coins often carried inscriptions proclaiming dynastic claims and genealogical details. Examples include coins with such inscriptions, asserting the lineage of rulers and reinforcing their right to govern, showcasing the political significance embedded in numismatic evidence.

#8. What did the cultural synthesis on Satavahana coins reveal about their political and economic adaptability?

Ans. Satavahana coins, through linguistic diversity and cultural symbols, revealed adaptability. Examples include coins showcasing a synthesis of diverse cultural elements, highlighting the Satavahanas’ ability to integrate linguistic and cultural diversity into their political and economic administration, fostering a resilient and adaptable governance structure.

Rajendra Mohwiya Sir

"www.historyoptional.in" राजेन्द्र मोहविया सर द्वारा UPSC सिविल सेवा परीक्षा की तैयारी कर रहे विद्यार्थियों के लिए एक मार्गदर्शक के रूप में शुरू की गई पहल है, जो अपनी ऐतिहासिक समझ और विश्लेषणात्मक कौशल को निखारने के लिए डिज़ाइन किए गए पाठ्यक्रमों की एक विस्तृत श्रृंखला प्रदर्शित करती है। उत्कृष्टता के प्रति हमारी प्रतिबद्धता एक बहुआयामी दृष्टिकोण में परिलक्षित होती है जिसमें मुख्य रूप से UPSC सिविल सेवा परीक्षा से संबंधित 'इतिहास' (वैकल्पिक विषय) के विषयवार नोट्स, दैनिक उत्तर लेखन, टेस्ट सीरीज़ (प्रारंभिक एवं मुख्य परीक्षा), करंट अफेयर्स (दैनिक एवं मासिक स्तर पर) तथा विगत वर्षों (2023-2013) में पूछे गए प्रश्नपत्रों के व्याख्या सहित उत्तर को शामिल किया गया है।

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Privacy and Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Refund and Cancellation Policy

- Ancient History Topic Wise Notes

- Medieval History Topic Wise Notes

- Modern History Topic Wise Notes

- Art and Culture Topic Wise Notes

- World History Topic Wise Notes

- Ancient History Daily Answer Writing

- Medieval History Daily Answer Writing

- Modern History Daily Answer Writing

- Art and Culture Daily Answer Writing

- World History Daily Answer Writing

- Ancient History Previous Years Solved Papers

- Medieval History Previous Years Solved Papers

- Modern History Previous Years Solved Papers

- Art and Culture Previous Years Solved Papers

- World History Previous Years Solved Papers

- History Optional Foundation Course

- History Optional Mentorship Program

- Prelims GS Test Series 2024

- Prelims CSAT Test Series 2024

- Mains GS Test Series 2024

- Mains Essay Test Series 2024

- History Optional Test Series 2024

- Latest Notification 2024

- UPSC CSE Syllabus

- History Optional Notes

- Daily Current Affairs

Satavahanas-Sakas-Kushanas Dynasty, Rulers, Rise and Decline

The Satavahanas, Sakas, and Kushanas were dynasties that ruled over various parts of ancient India. Let us know about Satavahanas-Sakas-Kushanas Dynasty, Rulers, Rise and Decline.

Table of Contents

The Satavahanas, Sakas, and Kushanas were three important dynasties that ruled over various parts of ancient India. These dynasties played a significant role in shaping the political, social, and cultural landscape of the Indian subcontinent during their respective reigns.

The Satavahanas: Overview

The Satavahanas were a South Indian dynasty that ruled from the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE. They were known for their administrative skills and were responsible for the establishment of a stable and prosperous kingdom in the Deccan region. The Satavahanas were patrons of the arts and encouraged the development of literature, music, and dance.

The most prominent ruler of the Satavahanas was Gautamiputra Satakarni, who is credited with expanding the empire to include parts of present-day Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. He was also responsible for defeating the Shaka and Yavana invaders who had threatened the stability of the empire.

The Sakas: Overview

The Sakas were a Central Asian tribe that invaded India in the 2nd century BCE. They established a powerful kingdom in the northwestern part of the country, which is now modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Sakas were known for their military prowess and were responsible for introducing new weapons and techniques of warfare to the Indian subcontinent.

The most famous Saka ruler was Maues, who established his capital in Taxila and expanded the kingdom to include parts of present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan. However, the most significant contribution of the Sakas was the introduction of the Indo-Greek style of art and architecture, which had a lasting impact on Indian culture.

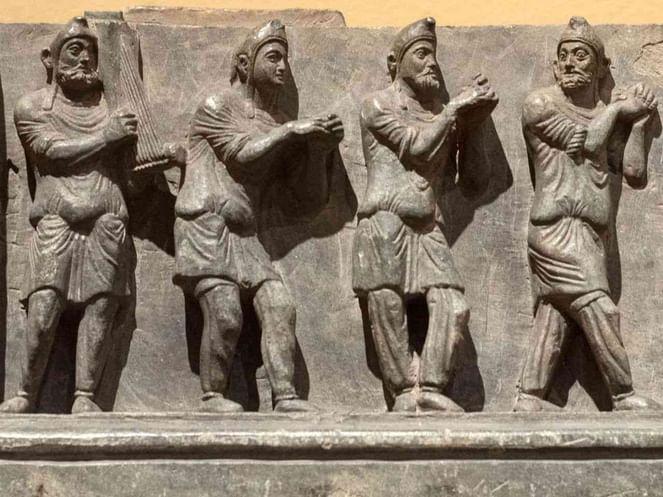

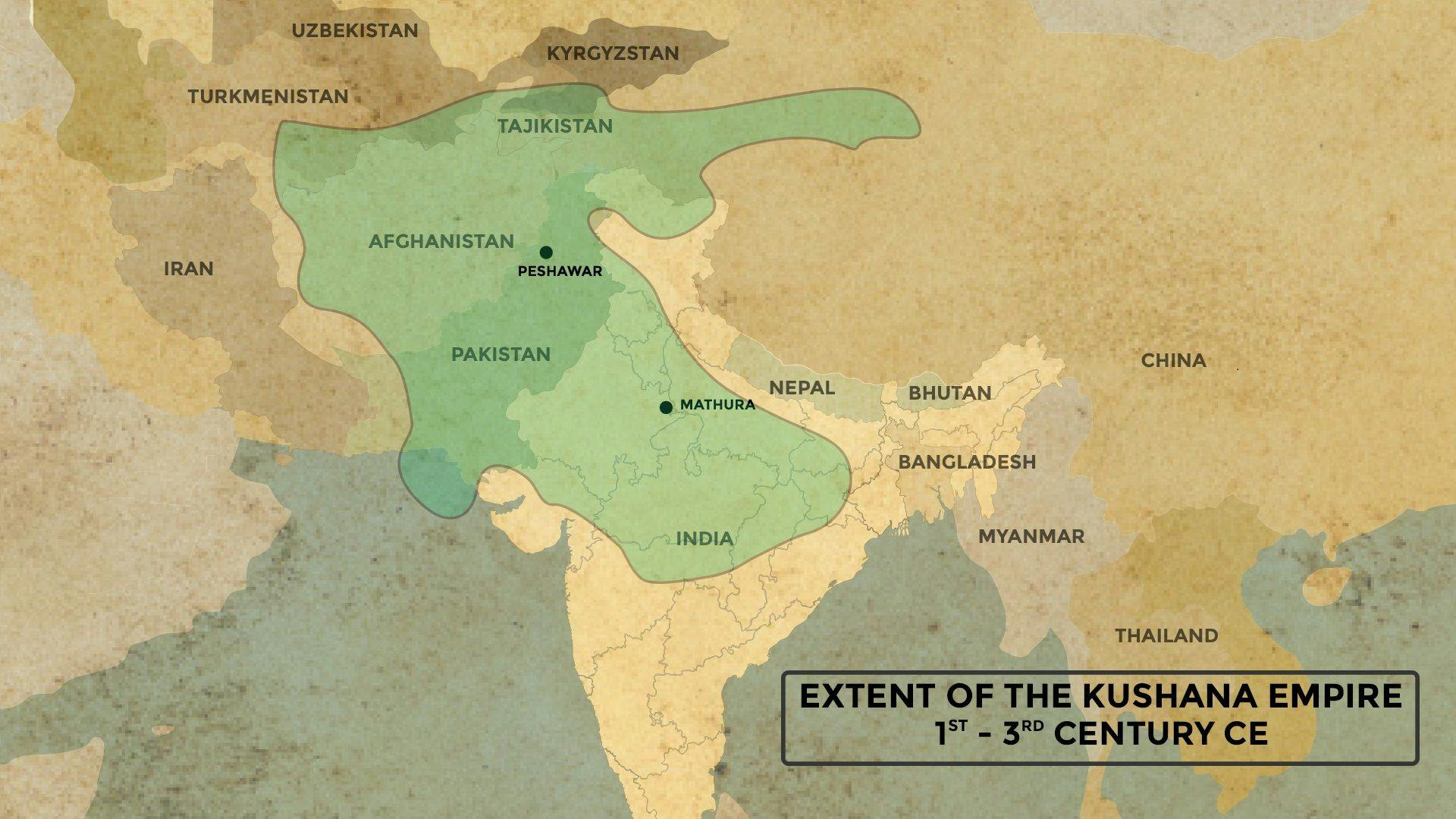

The Kushanas: Overview

The Kushanas were a Central Asian tribe that established a vast empire in northern India in the 1st century CE. They were known for their administrative skills and were responsible for the development of trade and commerce in the region. The Kushanas were also patrons of the arts and encouraged the development of literature, music, and sculpture.

The most famous Kushana ruler was Kanishka, who is credited with establishing a great empire that extended from Central Asia to the Gangetic plain. He was also responsible for promoting Buddhism and was a patron of Buddhist art and architecture. The Kushanas are known for their contribution to the development of the Gandhara school of art, which combined Indian and Hellenistic styles.

Satavahanas, Sakas, Kushanas in Detail

The Satavahanas, Sakas, and Kushanas were three dynasties that played a significant role in the history of ancient India. They were known for their administrative skills, military prowess, and patronage of the arts. Their contributions to the development of Indian culture and civilization are still felt today, and their legacy continues to inspire future generations.

Satavahana Dynasty

The Satavahanas were an ancient Indian dynasty that ruled over parts of the Indian subcontinent from the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE. They were known for their military prowess, administrative skills, and patronage of art and culture. The Satavahanas are considered to be one of the most significant dynasties in Indian history, and their contributions to Indian culture and society are still felt today.

Satavahana Dynasty: Origins and Early History

The origins of the Satavahanas are shrouded in mystery, and much of what is known about them is based on inscriptions and coins. According to some scholars, they were a tribe of people who lived in the Deccan region of India and rose to prominence during the 1st century BCE. Others believe that they were a Brahmin family that migrated to the Deccan region from northern India.

The earliest known ruler of the Satavahana dynasty was Simuka, who is believed to have ascended to the throne around 230 BCE. Simuka established his capital in Pratisthan, which is believed to be present-day Paithan in Maharashtra. Over the next few centuries, the Satavahanas expanded their territory through a combination of military conquest and strategic alliances with neighboring kingdoms.

Satavahana Dynasty Founder

The Satavahana dynasty was founded by Simuka, who ruled from around 230 BCE to 207 BCE. He is considered to be the first king of the Satavahana dynasty, which was one of the earliest South Indian dynasties. The Satavahanas were known for their patronage of Buddhism and the construction of several Buddhist stupas and other monuments.

They also played an important role in the trade routes between North and South India, and their rule saw the development of a number of important towns and cities in the region.

Satavahana Dynasty Rulers

The Satavahana dynasty ruled a large part of present-day India from around 230 BCE to 220 CE. Some of the important rulers of the Satavahana dynasty are:

1. Satavahana Dynasty Rulers: Simuka (230-207 BCE):

He is considered as the founder of the Satavahana dynasty and established his capital at Pratishthana (present-day Paithan in Maharashtra).

2. Satavahana Dynasty Rulers: Satakarni I (c. 180-160 BCE)

He was one of the most powerful rulers of the Satavahana dynasty and extended his empire to cover a large part of present-day India.

3. Satavahana Dynasty Rulers: Gautamiputra Satakarni (c. 106-130 CE)

He was a powerful ruler who is known for his military conquests and patronage of Buddhism.

4. Satavahana Dynasty Rulers: Vasishthiputra Pulumavi (c. 130-159 CE)

He was a patron of the arts and is credited with the construction of several important monuments.

5. Satavahana Dynasty Rulers: Yajna Sri Satakarni (c. 167-196 CE)

He was a powerful ruler who expanded the Satavahana empire and patronized Buddhism.

6. Satavahana Dynasty Rulers: Vijaya (c. 207-223 CE)

He was the last ruler of the Satavahana dynasty, and his reign marked the end of the dynasty’s dominance in Indian politics.

Satavahana Dynasty: Military Prowess

The Satavahanas were known for their military prowess and their ability to conquer and control vast territories. They had a formidable army that was equipped with state-of-the-art weapons and armor, and they employed innovative tactics to defeat their enemies. The Satavahanas also had a well-organized administrative system that helped them maintain control over their territories.

One of the most significant military achievements of the Satavahanas was their defeat of the Shakas, a Central Asian tribe that had invaded northwestern India in the 1st century BCE. The Satavahanas, under the leadership of Gautamiputra Satakarni, defeated the Shakas in a series of battles and forced them to flee back to Central Asia.

Satavahana Dynasty: Administrative System

The Satavahanas had a well-organized administrative system that helped them maintain control over their vast territories. They divided their empire into provinces, which were governed by governors appointed by the king. The governors were responsible for maintaining law and order, collecting taxes, and ensuring the smooth functioning of the administrative machinery.

The Satavahanas also had a complex system of taxation, which included taxes on agriculture, trade, and professions. They used the revenue generated from these taxes to fund their military campaigns and patronage of art and culture.

Satavahana Dynasty: Patronage of Art and Culture

The Satavahanas were great patrons of art and culture, and they supported a thriving artistic and literary culture in their empire. They were particularly known for their patronage of Buddhist art and architecture, and many of the famous Buddhist caves and stupas in India were built during the Satavahana period.

The Satavahanas also promoted the development of Sanskrit literature and supported the work of famous poets and scholars such as Vimalakirti, Harisena, and Sarvasena. They were also known for their patronage of the performing arts, and their court was renowned for its music, dance, and drama.

Decline of Satavahana Dynasty

- The Satavahana dynasty was an ancient Indian dynasty that ruled in the Deccan region from around 230 BCE to 220 CE.

- The decline of the Satavahana dynasty is believed to have been caused by a combination of internal factors such as weak successors, succession struggles, and a decline in economic and administrative efficiency, as well as external factors such as invasions and attacks from foreign powers.

- One of the major internal factors that contributed to the decline of the Satavahanas was the succession struggles and weak successors.

- After the death of Gautamiputra Satakarni, the last great ruler of the Satavahanas, the empire was divided among his sons, which led to internal conflicts and weakened the central authority of the dynasty.

- This resulted in regional governors becoming more powerful and eventually breaking away to form their own independent states.

- Another factor that contributed to the decline of the Satavahanas was a decline in economic and administrative efficiency.

- The Satavahanas were known for their efficient administration, trade and commerce, and patronage of arts and culture.

- However, towards the end of the dynasty, the administration became weak, and the economy suffered due to a decline in trade and commerce.

- External factors such as invasions and attacks from foreign powers also contributed to the decline of the Satavahanas.

- The Sakas, Yavanas, and Pahlavas, who had been living in the northwest of India, began to infiltrate into the Deccan region during the reign of Satavahana king Gautamiputra Satakarni.

- These foreign powers threatened the security and stability of the Satavahana empire, and their constant attacks weakened the dynasty further.

Overall, a combination of internal and external factors contributed to the decline of the Satavahana dynasty. The weakening of the central authority, succession struggles, a decline in economic and administrative efficiency, and attacks from foreign powers all played a role in the eventual downfall of this once-great empire.

Satavahana Dynasty: Legacy

The Satavahanas made significant contributions to Indian culture and society, and their legacy can still be felt today. They played an important role in the spread of Buddhism in India and helped establish it as a major religion in the country. They also helped promote the development of Sanskrit literature and supported the work of famous poets and scholars.

Saka Dynasty

The Saka Dynasty is one of the most significant dynasties of ancient India. It was established in the 1st century BCE by the nomadic Saka tribes, who originated from Central Asia. The dynasty ruled over a vast area that encompassed modern-day Pakistan, Afghanistan, and parts of northwestern India. The Saka Dynasty played a crucial role in shaping the history and culture of ancient India.

Origins of the Saka Dynasty

The Saka tribes were originally from the region of present-day Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. They were a nomadic people who had migrated to the Indian subcontinent in search of new pastures for their herds of cattle. They settled in the northwestern regions of the subcontinent, including modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The Saka tribes were fierce warriors and skilled horse riders. They established their rule over the regions they had settled in and gradually assimilated with the local population. Over time, they formed a distinct culture and identity that came to be known as the Saka culture.

Saka Dynasty Founder

The Saka dynasty is believed to have been founded by King Kharavela in the 1st century BCE. Kharavela was a powerful king of Kalinga (present-day Odisha, India) who ruled from his capital city of Kalinganagara (modern-day Sisupalgarh). He is known for his military conquests and patronage of the arts and culture. The Saka dynasty was one of the important dynasties in ancient India, and it ruled over parts of present-day India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

Saka Dynasty Rulers

The Saka dynasty was a dynasty of Indo-Scythian rulers who ruled parts of present-day Pakistan, Afghanistan, and northwestern India from around 200 BCE to 400 CE. The Saka dynasty had several rulers, including:

1. Saka Dynasty Rulers: Maues (c. 90 BCE)

He was the first known ruler of the Saka dynasty who consolidated the Indo-Scythian territories in northwest India.

2. Saka Dynasty Rulers: Vonones (c. 75-65 BCE)

He was a successor of Maues and expanded the Saka rule further eastwards into northern India.

3. Saka Dynasty Rulers: Azes I (c. 58-12 BCE)

He was one of the most important Saka rulers who consolidated the Saka rule in northern India and issued several coins with his name on it.

4. Saka Dynasty Rulers: Azilises (c. 12 BCE-10 CE)

He was the son of Azes I and succeeded him on the throne.

5. Saka Dynasty Rulers: Zeionises (c. 10-35 CE)

He was a successor of Azilises and is known for his coins and inscriptions found in the Punjab region.

6. Saka Dynasty Rulers: Kharahostes (c. 10-20 CE)

He was a contemporary of Zeionises and ruled parts of the present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan.

7. Saka Dynasty Rulers: Kanishka (c. 127-150 CE)

He was the most famous ruler of the Saka dynasty and one of the greatest kings of ancient India. He expanded the Saka rule further into northern India and is known for his patronage of Buddhism.

8. Saka Dynasty Rulers: Vasudeva I (c. 192-225 CE)

He was a successor of Kanishka and ruled over a smaller territory than his predecessor.

Rise of the Saka Dynasty

- The Saka Dynasty was established by Maues, a Saka king who had conquered the region of Gandhara in present-day Pakistan.

- Maues was succeeded by his son, Azes I, who further expanded the Saka kingdom.

- Azes I was a powerful ruler who is credited with establishing the Saka era in 78 CE.

- The Saka Dynasty reached its zenith under the rule of Kanishka I, who was one of the greatest rulers of ancient India.

- Kanishka I was a patron of the arts and sciences and was instrumental in promoting Buddhism in the region.

- He is credited with organizing the Fourth Buddhist Council, which was held in Kashmir in the 1st century CE.

Kanishka I was also a great warrior and expanded the Saka kingdom to its greatest extent. He conquered large parts of present-day Pakistan, Afghanistan, and northwestern India. His rule marked the peak of the Saka Dynasty and the height of its power and influence.

Decline of Saka Dynasty

- The decline of the Saka dynasty is a complex topic, as several branches of the Saka dynasty ruled different regions of Central Asia and India at different times.

- However, one of the most significant factors contributing to the decline of the Saka dynasty was the invasion of the White Huns, also known as the Hephthalites.

- The White Huns were a nomadic people from Central Asia who invaded the region in the 5th century AD.

- They were fierce warriors who had a reputation for brutality and destruction.

- They swept through Central Asia and India, conquering and destroying many kingdoms, including the Saka dynasty.

- The Saka rulers who were able to survive the White Hun invasion were weakened by the conflict, and the power of the dynasty declined.

- Other factors that contributed to the decline of the Saka dynasty included internal conflicts, economic decline, and the rise of other regional powers.

Eventually, the Saka dynasty was absorbed into other regional powers, such as the Gupta Empire in India. The legacy of the Saka dynasty, however, continued to live on in the cultural and artistic achievements of the region, such as the famous Buddhist cave temples of Ajanta and Ellora.

Legacy of the Saka Dynasty

- The Saka Dynasty left a lasting legacy on the history and culture of ancient India.

- Their rule led to the assimilation of the Saka culture with the local cultures of the subcontinent, which resulted in the emergence of a unique Indo-Saka culture.

- The Saka Dynasty was also instrumental in the spread of Buddhism in the region.

- The rulers of the dynasty were great patrons of Buddhism and promoted its teachings and philosophy.

- This led to the establishment of numerous Buddhist monasteries and stupas across the Saka kingdom.

- The Saka era, which was established by Azes I in 78 CE, is still used as the official calendar in many parts of India and Nepal.

- The Saka era is also recognized by the Indian government as the official calendar for official purposes.

The Saka Dynasty played a crucial role in shaping the history and culture of ancient India. Their rule led to the emergence of a unique Indo-Saka culture, and they were instrumental in the spread of Buddhism in the region. The legacy of the Saka Dynasty is still felt in many parts of India and Nepal, and their contributions to Indian history and culture cannot be overstated.

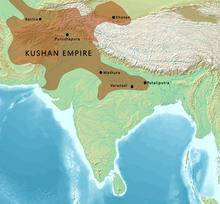

Kushan Dynasty

The Kushan Dynasty was an ancient empire that ruled a large part of Central Asia, northern India, and parts of China from the 1st to the 3rd century CE. The Kushans were a nomadic people of Central Asia who established a vast empire that played a significant role in the spread of Buddhism and the development of the Silk Road.

Origins of the Kushan Dynasty

The origins of the Kushan Dynasty can be traced back to the Yuezhi people, a nomadic tribe that lived in the region of present-day western China and Central Asia. The Yuezhi were defeated by the Xiongnu Empire in the 2nd century BCE and were forced to migrate to the west. The Yuezhi migrated to the region that is now Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, where they established a powerful confederation of tribes that became known as the Kushans.

Kushan Dynasty Founder

The Kushan Empire was founded by Kujula Kadphises, who was the first known ruler of the Kushan dynasty. Kujula Kadphises ruled from around 30 CE to 80 CE and was known for his military conquests and his efforts to expand the Kushan Empire. He was succeeded by his son, Vima Takto, who continued to expand the empire and is known for his patronage of Buddhism. The Kushan Empire was one of the most significant empires of ancient India and played an important role in the spread of Buddhism and trade along the Silk Road.

Kushan Dynasty Rulers

The Kushan Empire was a large ancient empire that existed from the 1st to the 4th century AD in parts of present-day India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central Asia. The Kushan rulers, also known as Kushanshahs, were a series of emperors who ruled the Kushan Empire. Here are some of the most significant Kushan dynasty rulers:

1. Kushan Dynasty Rulers: Kujula Kadphises (30 CE to 80 CE)

He was the founder of the Kushan Empire and ruled from around 30 CE to 80 CE.

2. Kushan Dynasty Rulers: Vima Kadphises (80 CE to 100 CE)

He was the son of Kujula Kadphises and ruled from around 80 CE to 100 CE. He expanded the empire into the regions of Gandhara and the Punjab.

3. Kushan Dynasty Rulers: Kanishka (127 CE to 150 CE)

He was one of the most famous and powerful Kushan rulers, who ruled from around 127 CE to 150 CE. He was known for his support of Buddhism and is credited with convening the Fourth Buddhist Council.

4. Kushan Dynasty Rulers: Huvishka (150 CE to 180 CE)

He was the successor of Kanishka and ruled from around 150 CE to 180 CE. He continued his predecessor’s support for Buddhism and sponsored many Buddhist projects.

5. Kushan Dynasty Rulers: Vasudeva I (191 CE to 230 CE)

He was the last significant Kushan ruler and ruled from around 191 CE to 230 CE. He faced many challenges, including invasions by the Sassanid Empire, which weakened the Kushan Empire.

Kushan Dynasty: Expansion of the Kushan Empire

- The Kushans established their capital at Peshawar, in present-day Pakistan, and began to expand their territory.

- They conquered the regions of Bactria, Sogdiana, and Gandhara, which encompassed present-day Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and parts of Pakistan.

- The Kushans also expanded into northern India, where they established their rule in the regions of Punjab, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh.

- The Kushan Empire was a cosmopolitan society that attracted traders and scholars from all over the world.

- The Kushans played a significant role in the development of the Silk Road, which was a network of trade routes that connected China to the Mediterranean.

- The Kushans established a strong trading relationship with the Chinese Han Dynasty, which allowed them to import Chinese goods such as silk and porcelain.

The Kushan Empire was also a center of Buddhist culture. The Kushan emperor Kanishka was a patron of Buddhism and sponsored the construction of several Buddhist monasteries and stupas, including the famous Gandhara school of art. The Kushan Empire played a significant role in the spread of Buddhism to China and other parts of Asia.

Decline of the Kushan Dynasty

The Kushan Empire, which existed from the 1st to the 3rd century CE, experienced a gradual decline over several decades, which eventually led to its collapse. Some of the major factors that contributed to the decline of the Kushan Dynasty are:

- Internal Conflicts: The Kushan Empire was plagued by internal conflicts and power struggles, which weakened the central authority and led to fragmentation of the empire.

- Economic Instability: The Kushan Empire heavily relied on trade, and its decline in trade relations with Rome and China caused economic instability and weakened the empire’s financial resources.

- External Threats: The rise of the Sassanid Empire in Persia and the Gupta Empire in India, both of which were expanding their territories, posed a serious threat to the Kushan Dynasty.

- Invasion by the Huns: The Huns, a nomadic tribe from Central Asia, invaded the Kushan Empire in the 4th century CE and destabilized the region, which led to the eventual collapse of the Kushan Dynasty.

These factors, along with others, contributed to the decline and eventual collapse of the Kushan Dynasty, and the region fell under the control of other powers such as the Sassanids and the Gupta Empire.

Kushan Dynasty: Legacy

The Kushan Dynasty was a powerful empire that played a significant role in the development of Central Asia, northern India, and the Silk Road. The Kushans were a cosmopolitan society that attracted traders and scholars from all over the world, and their patronage of Buddhism contributed to the spread of the religion throughout Asia. The Kushan Empire eventually declined due to internal conflicts and external pressures, but its legacy lived on in the region for centuries to come.

Check: All UPSC History Notes

Sharing is caring!

Who were the Satavahanas, and when did they rule?

The Satavahanas were a dynasty that ruled parts of present-day India from around 230 BCE to 220 CE. They were primarily centered in the Deccan region and are known for their contributions to art, literature, and architecture. The Satavahanas were also known for their patronage of Buddhism.

Who were the Sakas, and when did they rule in India?

The Sakas were a group of Central Asian nomads who migrated to India around 200 BCE. They established a powerful empire in the northwest region of India and ruled for nearly 400 years. The Sakas were known for their military prowess and their patronage of Buddhism.

Who were the Kushanas, and when did they rule in India?

The Kushanas were a Central Asian dynasty that ruled parts of present-day India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan from the 1st century CE to the 3rd century CE. They were known for their military conquests and their patronage of art, culture, and religion. The Kushanas were instrumental in spreading Buddhism to China and other parts of Asia.

Who were the Satavahanas?

The Satavahanas were a dynasty that ruled over parts of present-day India from around 230 BCE to 220 CE. They were known for their patronage of Buddhism and their military conquests.

Where did the Satavahanas originate?

The origin of the Satavahanas is somewhat unclear, but they are believed to have originated in the Deccan region of present-day India. The exact location of their capital city is also a matter of debate among historians.

What were some of the Satavahana's achievements?

The Satavahanas were known for their military conquests, which allowed them to expand their territory and establish their dominance over neighboring kingdoms. They were also known for their patronage of Buddhism, which helped to spread the religion throughout their kingdom.

What is the Saka Dynasty?

The Saka Dynasty was a royal lineage of the Indo-Scythian people who ruled in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent from the 1st century BCE to the 4th century CE.

Who founded the Saka Dynasty?

The Saka Dynasty was founded by Maues or Moga, who was a Central Asian warrior and is believed to have established his rule in the northwest region of India in the 1st century BCE.

What were the achievements of the Saka Dynasty?

The Saka Dynasty is known for its contributions in the fields of art, culture, and architecture. The Saka rulers were patrons of Buddhism and several Buddhist monasteries and stupas were built during their reign. They also introduced several new coins with various designs and inscriptions.

What was the Kushan dynasty?

The Kushan dynasty was a powerful empire that ruled over large parts of Central Asia and northern India from the 1st to the 3rd century CE. The Kushans were known for their cultural and religious diversity, as well as their military might and commercial wealth.

Who were the Kushans?

The Kushans were a Central Asian people of mixed ancestry, with roots in both the nomadic Scythian tribes and the settled Bactrian civilizations of the region. They established their rule in northern India and Central Asia during the 1st century CE, and their empire lasted for about 200 years.

What were the achievements of the Kushan dynasty?

The Kushan dynasty was known for its cultural and artistic achievements, particularly in the fields of sculpture, architecture, and coinage. They were also great patrons of Buddhism, and their empire saw the spread of Buddhism to new regions, including China. The Kushans were also known for their trade and commerce, as they controlled important trade routes linking China, India, and the Roman Empire.

Who were the famous rulers of the Kushan dynasty?

The most famous ruler of the Kushan dynasty was Kanishka the Great, who ruled from about 127 to 150 CE. Kanishka is known for his military campaigns, his patronage of Buddhism, and his support of the arts and sciences. Other notable rulers of the Kushan dynasty include Vima Kadphises, Huvishka, and Vasudeva I.

What led to the decline of the Kushan dynasty?

There were several factors that contributed to the decline of the Kushan dynasty, including political instability, economic pressures, and invasions by foreign tribes. The rise of the Gupta Empire in India in the 4th century CE also weakened the Kushan hold on the region, and by the 5th century CE, the Kushan empire had disintegrated into a number of smaller states.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

BPSC Exam 2024

- BPSC 70th Notification 2024

- BPSC Syllabus and Exam Pattern

- 69th BPSC Question Paper

- 69th BPSC Cut-Off

- BPSC Exam Date

- BPSC Officer Salary

- BPSC Previous Year paper

UPPSC RO ARO 2024

- UPPSC RO ARO Notification 2024

- UPPSC RO ARO Syllabus 2024

- UPPSC RO ARO eligibility 2024

- UPPSC RO ARO PYQ

- UPPSC RO ARO Salary 2024

RPSC RAS 2024

- RPSC RAS Question Paper

- RPSC RAS Exam Analysis

- RPSC RAS Cut off

- RPSC RAS Notification

- RPSC RAS Syllabus

- RPSC RAS Salary

- RPSC RAS Previous Year paper

- Madhya Pradesh Judiciary

- Punjab Judiciary

- Bihar Judiciary

- Notification

- Exam Date/Calendar

- History & Culture

- Polity & Governance

- Environment & Ecology

- Government Schemes & Initiatives

- UPSC Daily Quiz 2023

- UPSC Prelims Mock Test

- UPSC Current Affairs 2023

- Yojana Magazine

- The Hindu Editorial

IMPORTANT EXAMS

- UPSC Notification

- UPSC Syllabus

- UPSC Prelims P.Y.Q

- UPSC Final Result 2023

UPSC EPFO/APFC

- UPSC EPFO Syllabus

- UPSC EPFO Admit Card

- UPSC APFC Notification

- UPSC APFC Syllabus

- UPPSC PCS 2024

- MPPSC PCS 2024

- RPSC PCS 2024

- UKPSC PCS 2024

Our Other Websites

- Teachers Adda

- Bankers Adda

- Adda Malayalam

- Adda Punjab

- Current Affairs

- Defence Adda

- Adda Bengali

- Engineers Adda

- Adda Marathi

- Adda School

UPSC CSE Exam (Popularly called UPSC IAS Exam) is one of the toughest exam in this country. Needless to say, a dedicated and right approach is required to clear this IAS Exam.

Download Adda247 App

Follow us on

- Responsible Disclosure Program

- Cancellation & Refunds

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Post Mauryan Polities: The Kushanas and the Satavahanas

Sanjay Sharma

The Kushanas

The era of Kushanas, has remained relatively neglected in terms of its political importance in comparison to the other similar epochs. The imperial Kushanas established their empire in the vast areas of Asia transcending language and racial barriers. This was an age when different ethics and cultures came in contact and influenced each other. The sources of the history of Kushanas are primarily the Chinese chronicles. Prominent among them are the Ch’ien Han-Shu and the Hon Han-Shu. We begin our analysis of the political history of the Kushanas with the latest discoveries which have given new dimensions to it.

Kushana History in the Light of New Discoveries

A number of important discoveries in the last fifty years or so have given a new look to the history of the Kushana empire. One of the most prominent discovery has been the identification of the language used in most of the coins of Kaniska I and his successors. The finding of an inscription at Surkh-Kotal (Afghanistan) and few other evidences have helped the scholars to establish that the language normally used was a ‘middle Iranian’, written in Greek script. Henning called this language, Bactrian. Most of the coin legends and inscriptions under the Kushanas have been written in this language and this shows that Bactrian was the most important language of the empire.

Apart from this, there have been some inscriptions written in Kharoshti and Brahmi, which have been discovered recently. Important among them are the Kamra inscription of Vasishka of the year 20 (of the Kanishka era of c. 78 AD) and the Mathura inscription of Vasudeva II of the year 170 (of the same era). Moreover, a number of myths have now been broken, discoveries in future will break many more. One such example is that till recently Kanishka I was believed to be of a separate group from Kujula or Vima Kadphises but now it has been shown that the former was a lineal descendent of Kujula and perhaps an immediate successor of Vima Kadphises.

The Early History of Kushanas

The founders of the Kushana empire were the Hsi-hou (Yuvaga or leaders) of Kuei-Shuang (Kushana), perhaps a clan which was a part of Ta Yueh-chin or the Great Hueh-chin people. On the testimony of Chang Chien, it becomes clear that Ta Yueh-chin controlled some areas north of Oxus and also the region of Ta-hsia to the south of the river. Ta-hsia was initially equated with Bactria , but after considering the statement of Strabo in which he speaks of the conquest of Bactria by five nomadic tribes, more dimensions were touched upon for the identification of Ta-hsia. It is generally believed now that the Tokharoi, mentioned by Strabo as one of the tribes in the conquest, were either same as or affiliated with Ta Yueh-chin, and that Ta-hsia included areas of eastern Bactria-Wakhan, Chitral, Kafiristan, Badakshan etc. It was this area of eastern Bactria which was attacked by Ta Yueh-chin, the western Bactria being subjugated by the rest of the four Shaka nomadic tribes. This conquest of Bactria must have been completed by 130/129 BC.

Both the prominent Chinese chronicles, the Ch’ien Han-Shu and the Hon Han-Shu mention the Ta-hsia was divided among five Hsi-hou (Yuvaga or leaders) of Ta-Yueh-chin. One of these Hsi-hou was of Kuei- Shuang (Kushana). All these Yuvagas or leaders were dependent on a central authority which based somewhere to the north of the Oxus. The first known Kushana ruler was Miaos (Eraos), who was independent. He struck coins not just in the area south of the Oxus but also to the north of the river, which makes it clear that he was responsible for liquidating the powers of central authority. The other four Hsi-hou of Ta-hsia were defeated and subjugated by Kujula Kadphises . In any case it becomes clear that Miaos extended the Kushana kingdom to the north of the Oxus.

Kujula and Vima Kadphises

Kujula Kadphises (known to Chinese chronicles as Chiu-chiu-chueh) succeeded Miaos, either immediately or sometime later. The Hon Han-Shu speaks of his conquests up to the area of Ta-hsia, P’u- ta (area around Bactria), Kao-Fu ( Kabul ) and Chi-pin (north western region of the Indian subcontinent up to Kashmir valley). He must have also retained his dominions north of Oxus which were captured by Miaos. Kujula’s coins (of different varieties) have been found apart from Ta-hsia, in Paropanisadae, Gandhara (including Pushkalavati), Taxila and even in areas east of Jhelum. Kujula captured the Kabul area from Arsacids (the imperial Parthians), and Chi-pin from the Indo Parthians. The Hon Han-Shu further says that Kujula died at the ripened age of more than eighty, and he was succeeded by his son Vima Kadphises (known in Chinese chronicles as Yen-Kao-Chen). In one Kharoshti inscription he has been addressed as Sadakshana. There are epigraphic data to prove that he was ruling, either jointly with his father or independently, in 17 AD (Khatalese inscription of the year 187 of perhaps the era of 170 BC). Vima, who is known to be a valiant warrior snatched the Kandahar area up to Mathura and also Shen-tu from the Indo-Parthains. Shen-tu is identified with the ‘Lower Indus Country’.

It was for long believed that the term Kadphises was a surname of the father and the son, but recent researches have shown that it was rather a title which was perhaps derived from the old Iranian term kata-pisa meaning ‘of honoured form.’ So the absence of this title in the name of Kanishka does not necessarily mean that he belonged to an altogether different line. The recently discovered Kamra inscription has been very useful to find out a relation between the two. The Kamra inscription of Vasishka of the year 20 (of the Kanishka’s era of c. 78 AD) relates him to the branch of the great king Kala Kabisa Sachadhamathita, who according to B.N. Mukherjee has been identified with Kujula Kadphises. Moreover in the Mat (Mathura) inscription, reference to erection of a temple and a statue of Vima has been made and in another inscription the same temple has been attributed to the grandfather of Huvishka . This shows that Vima Kadphises was the grandfather of Huvishka. There is hardly any evidence to show that there was any interregnum between the reigns of Vima and Kanishka I. If 78 AD, is considered as the start of Kanishka I’s reign than Vima must have reigned up to that year.

Vima Kadphises was succeeded on the Kushana throne by Kanishka I. He is by and large considered as the greatest monarch of Kushana family. The theory of his usurpation of the throne is now to be rejected in the light of new evidences mentioned earlier. At the very outset we must take into consideration, the fact that there were two Kanishka’s in the Kushana genealogy. The Kamra inscription of Vasishka, of the year 20 (of the Kanishka era of c. 78 AD) mentions of digging of a well on the occasion of the birth of Kanishka. This Kanishka seems to be different from the Kanishka who started the era of c. 78 AD The new born Kanishka is identified as the son of Vasishka.

The Extent of Kushana Empire Under Kanishka To authenticate the extent of Kanishka I’s empire has been a problem that has engrossed the scholars in recent times. It is certain though that Kanishka had under his control the area of North West Frontier Province, Punjab and Sind. The Rajatarangini testifies the rule of Kanishka, Vasishka and Huvishka over Kashmir and through epigraphs bearing his name in the Mathura region, the inclusion of this area in Kanishka’s empire has been confirmed. These confirmations show that he kept the Indian possession of Kujula and Vima under his rule as well. There are many more sources which indicate a further extension of his empire in India . Chinese sources have suggested his rule over Saketa (Fyzabad in UP) and Pataliputra. Testimony of inscriptions also show his control over Benaras, Kosam and Saheth-Maheth area. The Sanchi inscription of king Vakushana, who may be identified with Vasishka-Kushana, of the year 22 (of the Kanishka era) shows that eastern Malwa was also under his possession. Vasishka at this time must have been a co-ruler of Kanishka. One Chinese source (Yu Yang Tsa Tsu of year c. 860 AD) also refers to Kanishka’s successful campaign against the Satavahanas. The Satavahana king at this time seems to be Gautamiputra Satakarni . The Andhau inscription of Chastana shows that he was a contemporary of Kanishka I and as he used the title kshatrapa in the initial part of his rule, there is a possibility that he was a subordinate ruler, most probably of Kanishka.

Kanishka’s Relations with Contemporary Foreign Powers

New trends in the history of the Kushanas throw a fresh light on the relations of Kanishka with other contemporary foreign powers. A Chinese source tells us that the king of An-hsi (the Arsacid king who is not yet conclusively identified) attacked Chi-ni-cha (Kanishka) but was defeated badly by the latter. Another Chinese source tells about Kanishka’s expeditions beyond Pamirs. The source further says that the rulers of the frontier tribes in the area west of Yellow river (in China) were afraid of him.

One of the most prominent incident associated with Kanishka is that in c. 86 or 87 AD, he sent presents to the court of Han empire of China and asked for the hand of a Han Princess in marriage. The demand or request, whatever it was, was refused and so his relation with the Han emperor became inimical. In 90 AD, he attacked China with a huge army but it was repulsed by Pan-chao, the great Han general. In any case, it is clear that Kanishka ruled over a vast empire. The Naqsh-i-Rustam record of Sassanian king Shapur I indicates that even in the fag end, the Kushana empire stretched in the north up to Kashgarh, Sogdiana, and area around Tashkent. In the west it included the whole of Afghanistan except Seistan, in the east it included the Xingjiang province of China and also a territory in central Asia to the north of Oxus river.

Kanishka’s Date of Accession

Though there have been mutually divergent views among scholars about the actual date of accession of Kanishka but the generally accepted date is 78 AD. He ruled for 23 years i.e., from the year 1 to 23 of the Kanishka’s era of 78 AD. This era was given the name of Shaka era in a later age primarily because it was made popular by Shaka-Pahalava Satrapal rulers of western India and Deccan.

Kanishka : An Estimate

As we noted earlier, Kanishka was one of the most powerful monarchs and a towering personality of ancient India. His contribution to religion and art is immense. He was probably the first king in early India who incorporated north western India to his empire which extended up to central Asia. Hence the people of north-western part of Indian subcontinent got a unique exposure. Various diverse cultures started to intermingle. He gave protection to all religious communities like the Buddhists, Shaiva, Jains etc. The Bactrian, Gandhara and Mathura Schools of art flourished under him. He was associated with some prominent personalities of his age like Charak and Ashvaghosha. The fourth Buddhist council was also held under his patronage at Kundalavana (modern Harwan near Srinagar). In this council the Vibhashashastras were compiled. He established Kanishka vihara at Shah-ji-ki-dheri near Peshawar in Pakistan . This monastery was known world over for art and religion. The importance of Kanishka in encouraging trade and commerce cannot be ignored, Kushanas seem to have struck the largest number of gold coins.

The Kushana Empire After Kanishka

Kanishka was succeeded by Vasishka as the Kushana ruler. His rule has been mentioned from year 20 to 28 of the Kanishka era. But as Kanishka ruled up to year 23 of his own era, it seems that Vasishka was a co-ruler of Kanishka from year 20 to year 23. He in turn was succeeded by Huvishka who ruled from year 25 or 26 to year 60 of the Kanishka era, so he must have been a co-ruler of Vasishka from the year 25 or 26 to the year 28. They kept most of Kanishka’s possessions intact but in the east their rule must have been confined up to Mathura. According to the Hon Han-Shu, their empire stretched up to Sin Kiang province of China and in north west, it extended up to Merv in Turkmenistan. Vasishka, according to the Rajatarangini, was the founder of the town of Jushkapur, modern Zukur, to the north west of Srinagar.

Vasudeva I was the Kushana ruler who ruled from the year 64 to year 90 of the Kanishka era. The decline of Kushana empire started from his reign. It seems that in the early part of his reign, mahakshatrapa Rudradaman became an independent ruler of lower Sind and Suvira (areas of Gujarat ). This must have happened around 150 AD, which is an authentic date of Rudradaman’s Junagadh inscription. This was a shattering blow to the Kushana power. But apart from this loss the other dominions seem to have remained intact.

There are two more recorded rulers after Vasudeva I , Kanishka III and Vasudeva II. The latter was the last Kushana emperor. According to Chinese sources he must have been reigning around 230 AD. The Kushanas up to the area of Peshawar in the east were supplanted by the Sassanian king by 262 AD. They were succeeded by the Naga kings in the area of Mathura and some neighbouring areas.

Elements of Kushana Polity and Administration

The two major forces which moulded the Kushana polity at least in their Indian possessions were the boom in trading activities which perhaps lured the Kushanas to annex the territories of north western India and the second was the problem to administer this alien territory. The Kushana administration was not as centralised as was the Mauryas, as not many officials are mentioned in their inscriptions and coins.

One interesting feature of Kushanas has been a consistent use of grandiloquent titles by the rulers. This feature is evinced more from Kanishka onward as Kujula Kadphises, the founder of the Kushana empire in India, has been described with a title Yuvaga, leader or a small chief but as their power grew, the titles became heavier.

Interestingly Ashoka ruled a vast territory but bore a title of raja - comparatively much simpler than the titles used by the Kushanas– maharaja and rajatiraja. Prof. R.S. Sharma says “These Kushana titles perhaps betray a tendency towards tributary arrangements rather than the real exaltation of royal authority.” These titles must have been used under the compulsion of a feudatory or tribute paying organizational structure which comprised of tributary states or chiefs, who used titles of kings or chiefs but at the same time showed their subordination to the central authority. This feudatory character of Kushana polity can be shown through some other titles like shahi which was used by them. Vima Kadphises used the title mahishvara meaning, the great lord. Kanishka used the title kaisar perhaps to challenge the Roman authority but it seems nothing more than a superficial imitation.

Nothing much is known about the administrative hierarchy of Kushanas. Perhaps the empire was divided into provinces, each ruled by a mahakshatrapa, assisted by a kshatrapa but how many provinces were there in the empire, is not known conclusively.

The details of the military organization are also not laid down in the records. The use of the term dandanayaka suggests that he was an important military officer. Sources tell that horsemen were bound under law to wear trousers while riding. The Mathura statue of Kanishka reflects the same. The strength and salaries of Kushana army are not known. According to Prof. R.S. Sharma, raja, maharaja, kshatrapa and mahakshatrapa were civilian authorities while dandanayaka and mahadandanayaka were military and sometimes semi-military in nature. (semi-military duties of dandanayaka were more in vogue in newly conquered territories where the civil administration was to be handled by military officers).

Let’s now move on to the territorial units of administration. Vishaya, which was used under Guptas to signify a territorial unit, has also been corroborated by a Mahayanist text for the Kushanas. It refers to a devaputra ruling in a vishaya. Nothing is known about the city or urban administration under the Kushanas except for references to nigamas and shrenis.

Village was undoubtedly the lowest administrative unit, with gramika as its head. The functions of the gramika under the Kushanas were quite different from the gramabhojaka of the pre-Mauryan period and gramika of the Mauryan age. Our major source to study about gramika in the post-Mauryan period is Manu. One significant difference between the gramika of Mauryan and the gramika of post-Mauryan period is that the latter was free from the duty pertaining to the defence of the village; it was now shifted to the gulma or military cantonments stationed by the king in two, three or five villages in the countryside. The second major difference between the two was that the gramika in the post-Mauryan age was paid through land grants rather than a cash salary as in the case of the Mauryans or through the fines gathered from the villagers. Prof. R.S. Sharma opines. “Thus the first decreased and the second increased the power of headman. But on the whole the hereditary character of the post coupled with the grant of land for the office tilted in favour of the growing importance of the village headman.”

Two other prominent features of the Kushanas were, first, the title of Devaputra used by the Kushana kings and second, the practice of Devkula. Though the Kushanas were apparently Buddhists but still used the title of Devaputra i.e., son of god. Erecting Devkulas was another popular practice under the Kushanas. Devkula, according to the Pratimanataka of Bhasha, meant “the place where the statues were erected in honour of dead potentates.”

The Contribution of The Kushanas

The Kushanas, because of their contribution to the various disciplines of life, occupy a special place in the ancient Indian history. Let us now explore some of these contributions. It is not established quite comprehensively that the political activities of the Kushanas were guided by their economic perspectives. The Hon Han-Shu says that the Kushanas became very rich after occupying lower Indus region which had quite flourishing trade relations with the Roman empire . Also, as the Kushano-Roman maritime trade ended in around 150 AD, decline of Kushana empire started to gain impetus under Vasudeva I. This shows that they were highly dependent on trade for their survival. This was perhaps the reason, why Kushanas gave so much importance to trade. Agriculture was also given proper attention. A large scale irrigation networks have been discovered in north western India, Pakistan, Afghanistan which are datable to Kushana period. Such growth in trade resulted in the growth of trading centres and cities in the empire. Some traders shifted to the eastern part of India i.e., eastern Uttar Pradesh and Vanga and developed trading and commercial relations with the south east Asia.

The healthy state of economy, under Kushanas is also indicated by the coins that they struck. A Mathura epigraph of year 28 (Shaka era of 78 AD) indicates that even private agencies were allowed to struck and circulate coins in Kushana dominions. One important aspect of Kushana coinage is that their gold coins (dinaras) and copper coins (drammas) were meant for circulation in the whole empire, a system which was different from the coins of the pre-Kushana period in which a coin circulated in one area was typologically different from the other one. To explain in simpler terms, in pre-Kushana period, a coin struck in Gandhara region by a ruler was different from the one struck by the same ruler in the area of Arachosia . Thus it seems the Kushanas issued the first Imperial coinage. Silver coins of the Kushanas are found only in the area of the lower Indus. They issued the largest number of copper coins and the quality of their gold coins was very good.

New discoveries made in the area of central Asia have shown some startling examples of the Kushana architecture and art. Some discoveries of central Asia and Afghanistan have shown sculptures with stylistic features different from Gandhara, Mathura and other Hellenistic school. Scholars have named this schools as the Bactrian school. Prof. B.N. Mukherjee, while explaining the stylistic patterns of this school, says, “The sculptured human figures, which are some what frontal in treatment, show oval faces with open, somewhat bulging, or half closed eyes. Their hair is indicated by deep incisions or by curls looking like buttons.” He further says that, “Scholars have also been able to discern recently the feature of an imperial art as betrayed by royal sanctuaries and coinage of the Kushanas.” And finally, in the field of building architecture, they built a number of Devkulas, very similar to a Hindu temple, which were erected in commemoration of their predecessors. Even in literature and medicine India made progress with scholars like Charaka and Ashvaghosha etc.

The Satavahanas

The Satavahanas, who came to the forefront in the Indian political scene sometime in the middle of the first century BC, are one of the most prominent dynasties of ancient India. The Matsya Purana lists thirty Satavahana kings who ruled in Deccan, though their geographical extent kept changing. The Satavahanas were probably of Andhra origin. The historicity of some of the kings mentioned in the Puranas has been confirmed by the numismatic and epigraphic data. The historicity of others is still not clear.

The Early Satavahana Rulers

The founder of the Satavahana dynasty was one Simuka . He laid the foundation of his empire after destroying the Kanva power. He also erased the remaining traces of the Sungas. One of the Nanaghat inscriptions testifies his historicity. His coins have been reported from Kotalingala in the Karimnagar district which proves his domination over central Deccan. Numismatic sources also show his control over Apranta in western Deccan. According to the Puranas he ruled for 23 years. Simuka was succeeded by his brother Krishna (Kanha). He is identifiable with king Kanha of satavahanakula of the Nasik inscription. This inscription shows that Nasik in western Deccan was a part of his kingdom. He ruled for 18 years. He was succeeded by his son, Sri Satakarni. Discovery of his coin types in the area of Vidisha and Tripuri shows that he conquered new territories of central India (Vidisha area). The seventeenth king of the line was king Hala who is known as the author of Gatha Saptasati. The Periplus of the Erythean Sea and Ptolemy both indicate good trading relations between the Romans and the Satavahanas. Strabo also refers to an embassy sent by a king Poros (identified with Purnotsanga, the 18th Satavahana king or Pulomavi, the 15th king in line) to the Roman king extolling their friendship and the trading relations between the two. So, it seems that the Satavahanas consolidated their position because of this flourishing trade. But a serious setback to the Satavahanas in the region was the loss of northern part of their kingdom lying to the north of Bharuch and other parts of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat to Nahapana , the Kshaharata mahakshatrapa. The Satavahana king at this point in time is believed to be Sandanes or Sunandana or Sundara Satakarni.The Puranas identify him as the 20th Satavahana king.

Gautamiputra Satakarni

The eclipsed Satavahana power was rejuvenated by the 23rd Satavahana ruler of the Puranic list, Gautamiputra Satakarni . He is credited as the liberator of the Satavahana areas captured by Nahapana. One of the Nasik inscription datable to his eighteenth regnal year refers to the regranting of a land which, till that day, was under the control of Ushavadatta. From the epigraphic data it seems that the fight between Nahapana and Gautamiputra for political supremacy was a protracted one and it started probably in the fourteenth regnal year of the great Satavahana king. The Jogalthambi hoard of coins indicates that Gautamiputra overstruck a large number of coins originally issued by Nahapana.

Extent of Gautamiputra Satakarni’s Empire