- Forgot your Password?

First, please create an account

The goals of a persuasive speech: convincing, actuation, and stimulation.

- Stimulation

1. The Goals of a Persuasive Speech

The overall goal of a persuasive speech is for the audience to accept your viewpoint as the speaker.

However, this is not a nuanced enough definition to capture the actual goals of different persuasive speeches.

Persuasive speeches can be designed to convince, actuate, and/or stimulate the audience.

1a. Convincing

A convincing speech is designed to cause the audience to internalize and believe a viewpoint that they did not previously hold.

In a sense, a convincing argument changes the audience's mind.

term to know Convince To make someone believe, or feel sure about something, especially by using logic, argument or evidence.

1b. Actuation

An actuation speech has a slightly different goal. An actuation speech is designed to cause the audience to do something, to take some action.

This type of speech is particularly useful if the audience already shares some or all of your view.

term to know Actuate To incite to action; to motivate.

1c. Stimulation

Persuasive speeches can also be used to enhance how fervently the audience believes in an idea. In this instance, the speaker understands that the audience already believes in the viewpoint, but not to the degree that he or she would like.

As a result, the speaker tries to stimulate the audience, making them more enthusiastic about the view.

term to know Stimulation An activity causing excitement or pleasure.

summary In this lesson, you learned about the goals of a persuasive speech . Convincing speeches aim to get the audience to change their mind to accept the view put forth in the speech. Actuation speeches seek to incite a certain action in the audience. Stimulation speeches are designed to get an audience to believe more enthusiastically in a view.

Source: Boundless. "The Goals of a Persuasive Speech: Convincing, Actuation, and Stimulation." Boundless Communications Boundless, 17 Mar. 2017. Retrieved 22 May. 2017 from https://www.boundless.com/communications/textbooks/boundless-communications-textbook/persuasive-speaking-14/introduction-to-persuasive-speaking-72/the-goals-of-a-persuasive-speech-convincing-actuation-and-stimulation-283-7999/

To incite to action; to motivate.

To make someone believe, or feel sure about something, especially by using logic, argument or evidence.

An activity causing excitement or pleasure.

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

© 2024 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC.

Persuasive Speeches — Types, Topics, and Examples

What is a persuasive speech?

In a persuasive speech, the speaker aims to convince the audience to accept a particular perspective on a person, place, object, idea, etc. The speaker strives to cause the audience to accept the point of view presented in the speech.

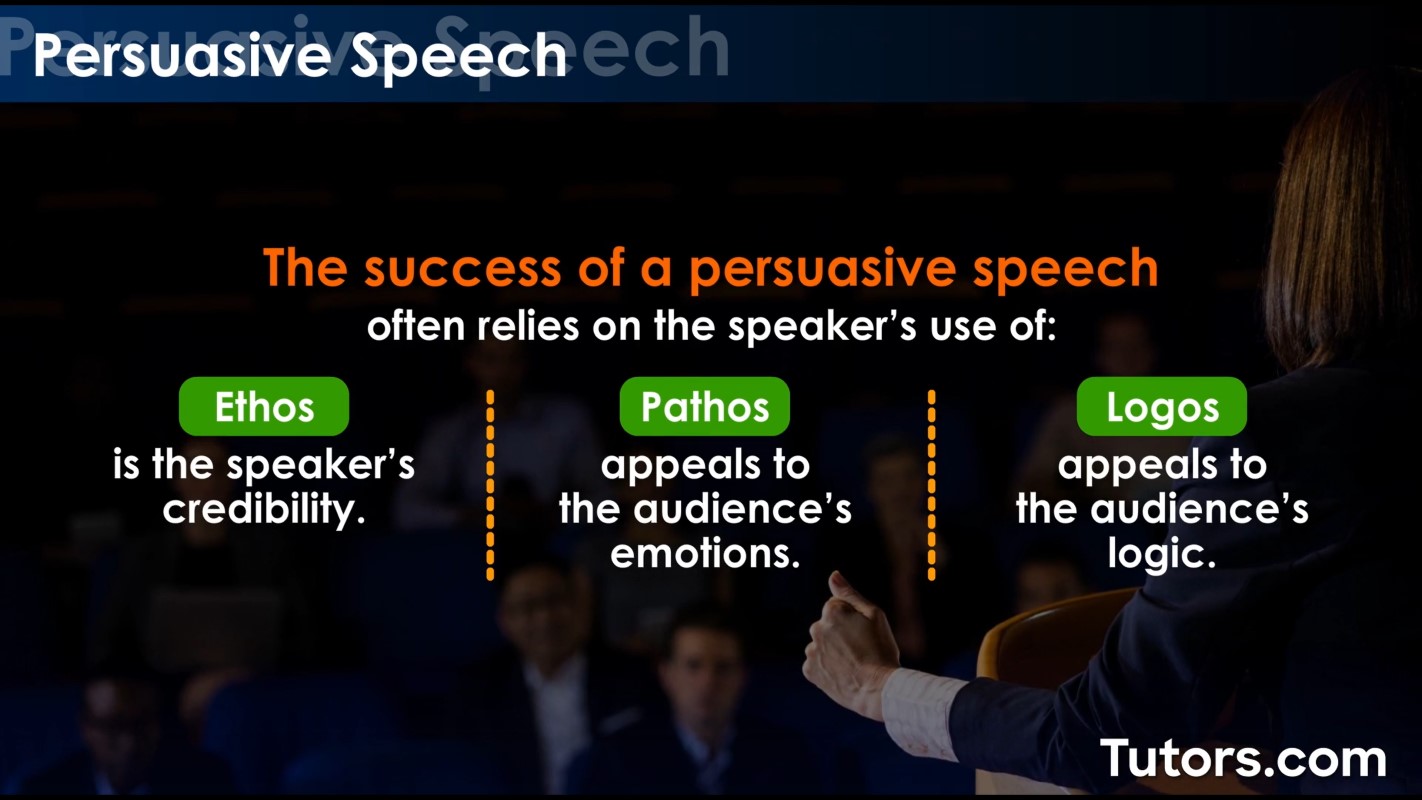

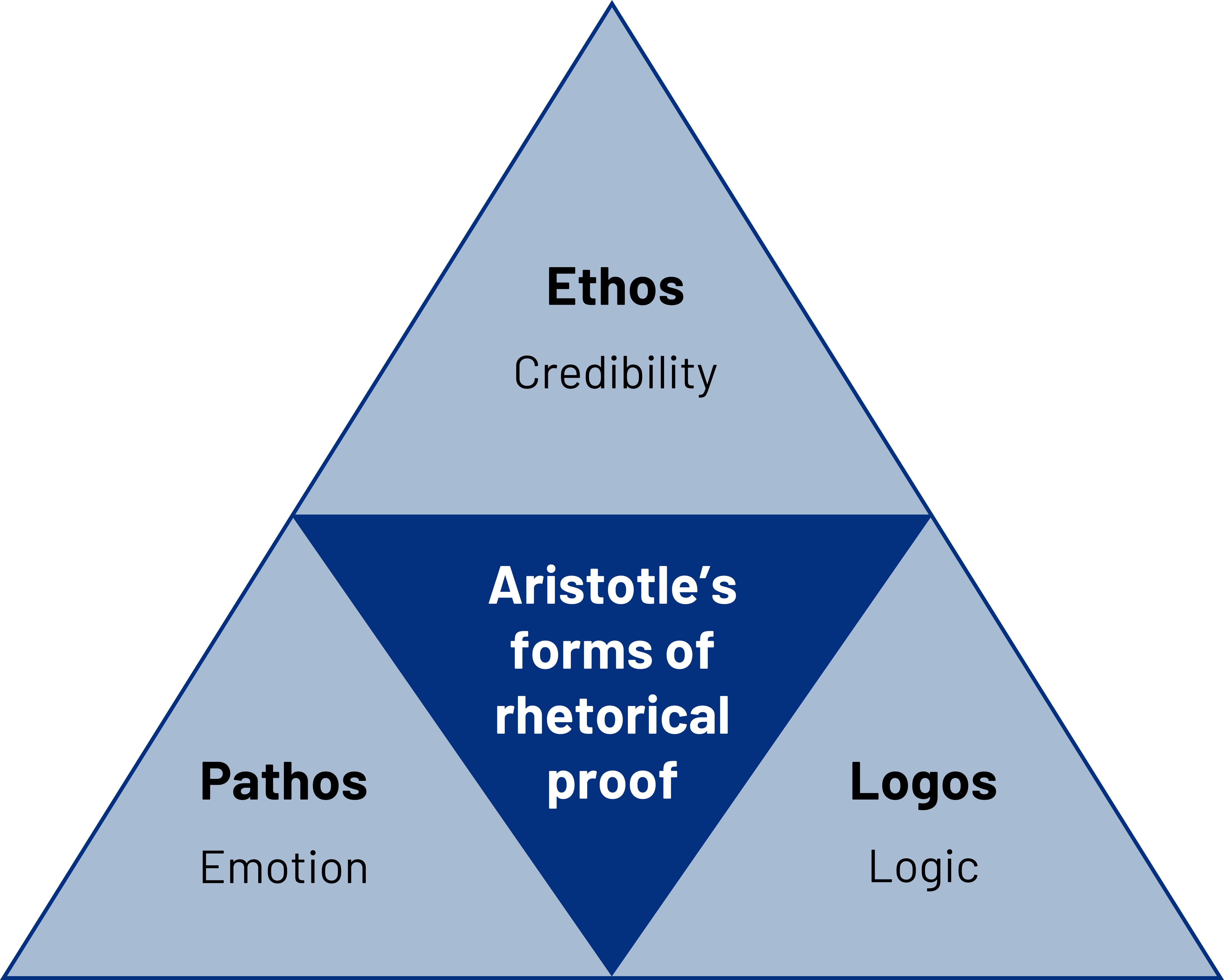

The success of a persuasive speech often relies on the speaker’s use of ethos, pathos, and logos.

Ethos is the speaker’s credibility. Audiences are more likely to accept an argument if they find the speaker trustworthy. To establish credibility during a persuasive speech, speakers can do the following:

Use familiar language.

Select examples that connect to the specific audience.

Utilize credible and well-known sources.

Logically structure the speech in an audience-friendly way.

Use appropriate eye contact, volume, pacing, and inflection.

Pathos appeals to the audience’s emotions. Speakers who create an emotional bond with their audience are typically more convincing. Tapping into the audience’s emotions can be accomplished through the following:

Select evidence that can elicit an emotional response.

Use emotionally-charged words. (The city has a problem … vs. The city has a disease …)

Incorporate analogies and metaphors that connect to a specific emotion to draw a parallel between the reference and topic.

Utilize vivid imagery and sensory words, allowing the audience to visualize the information.

Employ an appropriate tone, inflection, and pace to reflect the emotion.

Logos appeals to the audience’s logic by offering supporting evidence. Speakers can improve their logical appeal in the following ways:

Use comprehensive evidence the audience can understand.

Confirm the evidence logically supports the argument’s claims and stems from credible sources.

Ensure that evidence is specific and avoid any vague or questionable information.

Types of persuasive speeches

The three main types of persuasive speeches are factual, value, and policy.

A factual persuasive speech focuses solely on factual information to prove the existence or absence of something through substantial proof. This is the only type of persuasive speech that exclusively uses objective information rather than subjective. As such, the argument does not rely on the speaker’s interpretation of the information. Essentially, a factual persuasive speech includes historical controversy, a question of current existence, or a prediction:

Historical controversy concerns whether an event happened or whether an object actually existed.

Questions of current existence involve the knowledge that something is currently happening.

Predictions incorporate the analysis of patterns to convince the audience that an event will happen again.

A value persuasive speech concerns the morality of a certain topic. Speakers incorporate facts within these speeches; however, the speaker’s interpretation of those facts creates the argument. These speeches are highly subjective, so the argument cannot be proven to be absolutely true or false.

A policy persuasive speech centers around the speaker’s support or rejection of a public policy, rule, or law. Much like a value speech, speakers provide evidence supporting their viewpoint; however, they provide subjective conclusions based on the facts they provide.

How to write a persuasive speech

Incorporate the following steps when writing a persuasive speech:

Step 1 – Identify the type of persuasive speech (factual, value, or policy) that will help accomplish the goal of the presentation.

Step 2 – Select a good persuasive speech topic to accomplish the goal and choose a position .

Step 3 – Locate credible and reliable sources and identify evidence in support of the topic/position. Revisit Step 2 if there is a lack of relevant resources.

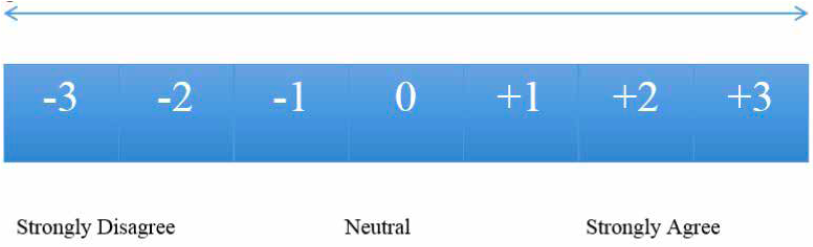

Step 4 – Identify the audience and understand their baseline attitude about the topic.

Step 5 – When constructing an introduction , keep the following questions in mind:

What’s the topic of the speech?

What’s the occasion?

Who’s the audience?

What’s the purpose of the speech?

Step 6 – Utilize the evidence within the previously identified sources to construct the body of the speech. Keeping the audience in mind, determine which pieces of evidence can best help develop the argument. Discuss each point in detail, allowing the audience to understand how the facts support the perspective.

Step 7 – Addressing counterarguments can help speakers build their credibility, as it highlights their breadth of knowledge.

Step 8 – Conclude the speech with an overview of the central purpose and how the main ideas identified in the body support the overall argument.

Persuasive speech outline

One of the best ways to prepare a great persuasive speech is by using an outline. When structuring an outline, include an introduction, body, and conclusion:

Introduction

Attention Grabbers

Ask a question that allows the audience to respond in a non-verbal way; ask a rhetorical question that makes the audience think of the topic without requiring a response.

Incorporate a well-known quote that introduces the topic. Using the words of a celebrated individual gives credibility and authority to the information in the speech.

Offer a startling statement or information about the topic, typically done using data or statistics.

Provide a brief anecdote or story that relates to the topic.

Starting a speech with a humorous statement often makes the audience more comfortable with the speaker.

Provide information on how the selected topic may impact the audience .

Include any background information pertinent to the topic that the audience needs to know to understand the speech in its entirety.

Give the thesis statement in connection to the main topic and identify the main ideas that will help accomplish the central purpose.

Identify evidence

Summarize its meaning

Explain how it helps prove the support/main claim

Evidence 3 (Continue as needed)

Support 3 (Continue as needed)

Restate thesis

Review main supports

Concluding statement

Give the audience a call to action to do something specific.

Identify the overall importan ce of the topic and position.

Persuasive speech topics

The following table identifies some common or interesting persuasive speech topics for high school and college students:

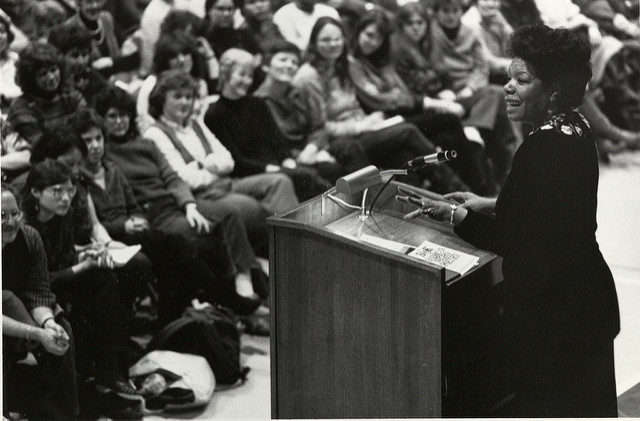

Persuasive speech examples

The following list identifies some of history’s most famous persuasive speeches:

John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address: “Ask Not What Your Country Can Do for You”

Lyndon B. Johnson: “We Shall Overcome”

Marc Antony: “Friends, Romans, Countrymen…” in William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar

Ronald Reagan: “Tear Down this Wall”

Sojourner Truth: “Ain’t I a Woman?”

How to Write and Structure a Persuasive Speech

- Homework Tips

- Learning Styles & Skills

- Study Methods

- Time Management

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

The purpose of a persuasive speech is to convince your audience to agree with an idea or opinion that you present. First, you'll need to choose a side on a controversial topic, then you will write a speech to explain your position, and convince the audience to agree with you.

You can produce an effective persuasive speech if you structure your argument as a solution to a problem. Your first job as a speaker is to convince your audience that a particular problem is important to them, and then you must convince them that you have the solution to make things better.

Note: You don't have to address a real problem. Any need can work as the problem. For example, you could consider the lack of a pet, the need to wash one's hands, or the need to pick a particular sport to play as the "problem."

As an example, let's imagine that you have chosen "Getting Up Early" as your persuasion topic. Your goal will be to persuade classmates to get themselves out of bed an hour earlier every morning. In this instance, the problem could be summed up as "morning chaos."

A standard speech format has an introduction with a great hook statement, three main points, and a summary. Your persuasive speech will be a tailored version of this format.

Before you write the text of your speech, you should sketch an outline that includes your hook statement and three main points.

Writing the Text

The introduction of your speech must be compelling because your audience will make up their minds within a few minutes whether or not they are interested in your topic.

Before you write the full body you should come up with a greeting. Your greeting can be as simple as "Good morning everyone. My name is Frank."

After your greeting, you will offer a hook to capture attention. A hook sentence for the "morning chaos" speech could be a question:

- How many times have you been late for school?

- Does your day begin with shouts and arguments?

- Have you ever missed the bus?

Or your hook could be a statistic or surprising statement:

- More than 50 percent of high school students skip breakfast because they just don't have time to eat.

- Tardy kids drop out of school more often than punctual kids.

Once you have the attention of your audience, follow through to define the topic/problem and introduce your solution. Here's an example of what you might have so far:

Good afternoon, class. Some of you know me, but some of you may not. My name is Frank Godfrey, and I have a question for you. Does your day begin with shouts and arguments? Do you go to school in a bad mood because you've been yelled at, or because you argued with your parent? The chaos you experience in the morning can bring you down and affect your performance at school.

Add the solution:

You can improve your mood and your school performance by adding more time to your morning schedule. You can accomplish this by setting your alarm clock to go off one hour earlier.

Your next task will be to write the body, which will contain the three main points you've come up with to argue your position. Each point will be followed by supporting evidence or anecdotes, and each body paragraph will need to end with a transition statement that leads to the next segment. Here is a sample of three main statements:

- Bad moods caused by morning chaos will affect your workday performance.

- If you skip breakfast to buy time, you're making a harmful health decision.

- (Ending on a cheerful note) You'll enjoy a boost to your self-esteem when you reduce the morning chaos.

After you write three body paragraphs with strong transition statements that make your speech flow, you are ready to work on your summary.

Your summary will re-emphasize your argument and restate your points in slightly different language. This can be a little tricky. You don't want to sound repetitive but will need to repeat what you have said. Find a way to reword the same main points.

Finally, you must make sure to write a clear final sentence or passage to keep yourself from stammering at the end or fading off in an awkward moment. A few examples of graceful exits:

- We all like to sleep. It's hard to get up some mornings, but rest assured that the reward is well worth the effort.

- If you follow these guidelines and make the effort to get up a little bit earlier every day, you'll reap rewards in your home life and on your report card.

Tips for Writing Your Speech

- Don't be confrontational in your argument. You don't need to put down the other side; just convince your audience that your position is correct by using positive assertions.

- Use simple statistics. Don't overwhelm your audience with confusing numbers.

- Don't complicate your speech by going outside the standard "three points" format. While it might seem simplistic, it is a tried and true method for presenting to an audience who is listening as opposed to reading.

- How to Write a Persuasive Essay

- 5 Tips on How to Write a Speech Essay

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- Writing an Opinion Essay

- How To Write an Essay

- 5 Steps to Writing a Position Paper

- How to Structure an Essay

- Ethos, Logos, Pathos for Persuasion

- What Is Expository Writing?

- Audience Analysis in Speech and Composition

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- 100 Persuasive Speech Topics for Students

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- How to Write a Graduation Speech as Valedictorian

- How to Write a Letter of Complaint

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11 Persuasive Speaking

Introduction, 11.1 foundation of persuasion.

Persuasive speaking seeks to influence the beliefs, attitudes, values, or behaviors of audience members. In order to persuade, a speaker has to construct arguments that appeal to audience members (Poggi, 2005). Arguments form around three components: claim, evidence, and warrant.

The claim is the statement that will be supported by evidence. Your thesis statement is the overarching claim for your speech, but you will make other claims within the speech to support the larger thesis (Nordquist, 2020). Evidence , also called grounds, supports the claim (McCroskey, 1969). The main points of your persuasive speech and the supporting material you include serve as evidence. For example, a speaker may make the following claim: “There should be a national law against texting while driving.” The speaker could then support the claim by providing the following evidence: “Research from the US Department of Transportation has found that texting while driving creates a crash risk that is twenty-three times worse than driving while not distracted.” The warrant is the underlying justification that connects the claim and the evidence (McCroskey, 1966). One warrant for the claim and evidence cited in this example is that the U.S. Department of Transportation is an institution that funds research conducted by credible experts. An additional and more implicit warrant is that people should not do things they know are unsafe.

As you put together a persuasive argument, you act as the judge. You can evaluate arguments that you come across in your research by analyzing the connection (the warrant) between the claim and the evidence (McCroskey, 1966). If the warrant is strong, you may want to highlight that argument in your speech. You may also be able to point out a weak warrant in an argument that goes against your position, which you could then include in your speech. Every argument starts by putting together a claim and evidence, but arguments grow to include many interrelated units.

11.2 Adapting Persuasive Messages

Competent speakers should consider their audience throughout the speech-making process. Given that persuasive messages seek to influence directly the audience in some way, audience adaptation becomes even more important (Hamm, 2006).

When you have audience members who already agree with your proposition, you should focus on intensifying their agreement. You can also assume that they have foundational background knowledge of the topic, which means you can take the time to inform them about lesser-known aspects of a topic or cause to reinforce further their agreement. Rather than move these audience members from disagreement to agreement, you can focus on moving them from agreement to action. Remember, calls to action should be as specific as possible to help you capitalize on audience members’ motivation in the moment, so they are more likely to follow through on the action (Hamm, 2006).

There are two main reasons audience members may be neutral about your topic: (1) they are uninformed about the topic or (2) they do not think the topic affects them. In this case, you should focus on instilling a concern for the topic. Uninformed audiences may need background information before they can decide if they agree or disagree with your proposition. If the issue is familiar but audience members are neutral because they do not see how the topic affects them, focus on getting the audience’s attention and demonstrating relevance. Remember that concrete and proxemic supporting materials will help an audience find relevance in a topic. Students who pick narrow or unfamiliar topics will have to work harder to persuade their audience, but neutral audiences often provide the most chance of achieving your speech goal since even a small change may move them into agreement (Williams, 2018).

When audience members disagree with your proposition, you should focus on changing their minds. To persuade effectively, you must be seen as a credible speaker. When an audience is hostile to your proposition, establishing credibility is even more important, as audience members may be quick to discount or discredit someone who does not appear prepared or does not present well-researched and supported information. Do not give an audience a chance to write you off before you even get to share your best evidence. When facing a disagreeable audience, the goal should also be small change. You may not be able to switch someone’s position completely but influencing him or her is still a success. Aside from establishing your credibility, you should also establish common ground with an audience. Acknowledging areas of disagreement and logically refuting counterarguments in your speech is also a way to approach persuading an audience in disagreement, as it shows that you are open-minded enough to engage with other perspectives (Williams, 2018).

11.3 Determining Your Proposition

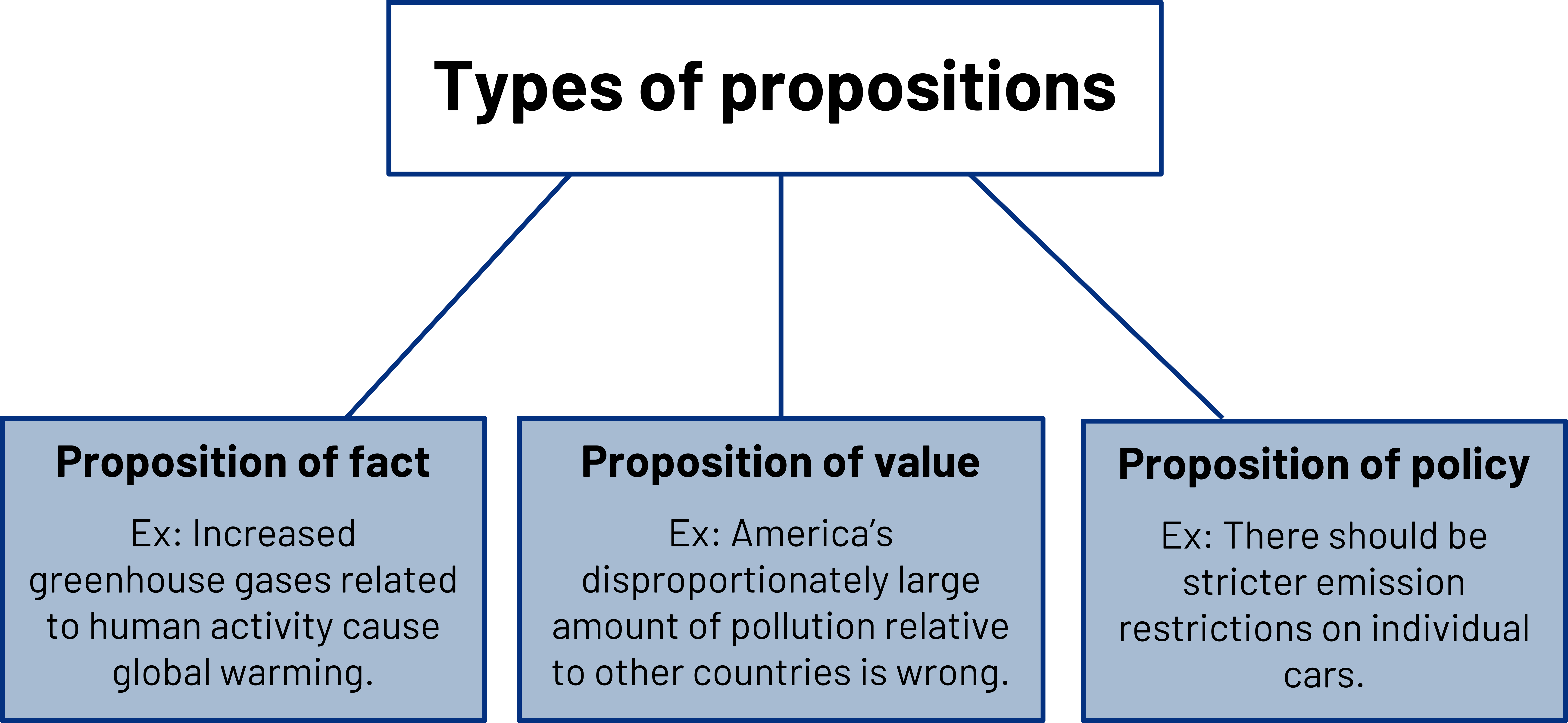

The proposition of your speech is the overall direction of the content and how that content relates to the speech goal. A persuasive speech will fall primarily into one of three categories: propositions of fact, value, or policy (Mackay, 2012). A speech may have elements of any of the three propositions, but you can usually determine the overall proposition of a speech from the specific purpose and thesis statements.

Propositions of fact focus on beliefs and try to establish that something “is or isn’t.” Propositions of value focus on persuading audience members that something is “good or bad,” “right or wrong,” or “desirable or undesirable.” Propositions of policy advocate that something “should or shouldn’t” be done (Mackay, 2012). Since most persuasive speech topics can be approached as propositions of fact, value, or policy, it is a good idea to start thinking about what kind of proposition you want to make, as it will influence how you go about your research and writing. As you can see in the following example using the topic of global warming, the type of proposition changes the types of supporting materials you would need:

- Proposition of fact. Increased greenhouse gases related to human activity cause global warming.

- Proposition of value. America’s disproportionately large amount of pollution relative to other countries is wrong.

- Proposition of policy. There should be stricter emission restrictions on individual cars.

To support propositions of fact, you would want to present a logical argument based on objective facts that can then be used to build persuasive arguments. Propositions of value may require you to appeal more to your audience’s emotions and cite expert and lay testimony. Persuasive speeches about policy usually require you to research existing and previous laws or procedures and determine if any relevant legislation or propositions are currently being considered (Barton & Tucker, 2021).

11.4 Organizing a Persuasive Speech

We have already discussed several patterns for organizing your speech, but some organization strategies are specific to persuasive speaking. Some persuasive speech topics lend themselves to a topical organization pattern, which breaks the larger topic up into logical divisions. Recency and primacy, as well as adapting a persuasive speech based on the audience’s orientation toward the proposition can be connected when organizing a persuasive speech topically. Primacy means putting your strongest information first. It is based on the idea that audience members put more weight on what they hear first. This strategy can be especially useful when addressing an audience that disagrees with your proposition, as you can try to win them over early. Recency means putting your strongest information last to leave a powerful impression. This can be useful when you are building to a climax in your speech, specifically if you include a call to action (Morrison, 2015).

The problem-solution pattern is an organizational pattern that advocates for a particular approach to solve a problem. You would provide evidence to show that a problem exists and then propose a solution with additional evidence or reasoning to justify the course of action (Macasieb, 2018). One main point addressing the problem and one main point addressing the solution may be sufficient, but you are not limited to two. You could add a main point between the problem and solution that outlines other solutions that have failed. You can also combine the problem-solution pattern with the cause-effect pattern or expand the speech to fit with Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

The cause-effect pattern can be used for informative speaking when the relationship between the cause and effect is not contested. The pattern is more fitting for persuasive speeches when the relationship between the cause and effect is controversial or unclear. There are several ways to use causes and effects to structure a speech. You could have a two-point speech that argues from cause to effect or from effect to cause. You could also have more than one cause that leads to the same effect or a single cause that leads to multiple effects. The following are some examples of thesis statements that correspond to various organizational patterns. As you can see, the same general topic area, prison overcrowding, is used for each example. This illustrates the importance of considering your organizational options early in the speech-making process, since the pattern you choose will influence your researching and writing.

- Problem-solution. Prison overcrowding is a serious problem that we can solve by finding alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

- Problem–failed solution–proposed solution. Prison overcrowding is a serious problem that should not be solved by building more prisons; instead, we should support alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

- Cause-effect. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-cause-effect. State budgets are being slashed and prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-effect-effect. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to increased behavioral problems among inmates and lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-effect-solution. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals; therefore, we need to find alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

Monroe’s motivated sequence is an organizational pattern designed for persuasive speaking that appeals to audience members’ needs and motivates them to action (Watt & Barnett, 2021). If your persuasive speaking goals include a call to action, you may want to consider this organizational pattern. Here is an example of that pattern:

Step 1: Attention

- Hook the audience by making the topic relevant to them.

- Imagine living a full life, retiring, and slipping into your golden years. As you get older, you become more dependent on others and move into an assisted-living facility. Although you think life will be easier, things get worse as you experience abuse and mistreatment from the staff. You report the abuse to a nurse and wait, but nothing happens and the abuse continues. Elder abuse is a common occurrence, and unlike child abuse, there are no laws in our state that mandate complaints of elder abuse be reported or investigated.

Step 2: Need

- Cite evidence to support the fact that the issue needs to be addressed.

- According to the American Psychological Association, one to two million elderly Americans have been abused by their caretakers. In our state, those in the medical, psychiatric, and social work field are required to report suspicion of child abuse but are not mandated to report suspicions of elder abuse.

Step 3: Satisfaction

- Offer a solution and persuade the audience that it is feasible and well thought out.

- There should be a federal law mandating that suspicion of elder abuse be reported and that all claims of elder abuse be investigated.

Step 4: Visualization

- Take the audience beyond your solution and help them visualize the positive results of implementing it or the negative consequences of not.

- Elderly people should not have to live in fear during their golden years. A mandatory reporting law for elderly abuse will help ensure that the voices of our elderly loved ones will be heard.

Step 5: Action

- Call your audience to action by giving them concrete steps to follow to engage in a particular action or to change a thought or behavior.

- I urge you to take action in two ways. First, raise awareness about this issue by talking to your own friends and family. Second, contact your representatives at the state and national level to let them know that elder abuse should be taken seriously and given the same level of importance as other forms of abuse. I brought cards with the contact information for our state and national representatives for this area. Please take one at the end of my speech. A short e-mail or phone call can help end the silence surrounding elder abuse.

11.5 Persuasive Reasoning and Fallacies

Persuasive speakers should be concerned with what strengthens and weakens an argument. Knowing different types of reasoning can help you put claims and evidence together in persuasive ways and help you evaluate the quality of arguments that you encounter. Further, being able to identify common fallacies of reasoning can help you be a more critical consumer of persuasive messages.

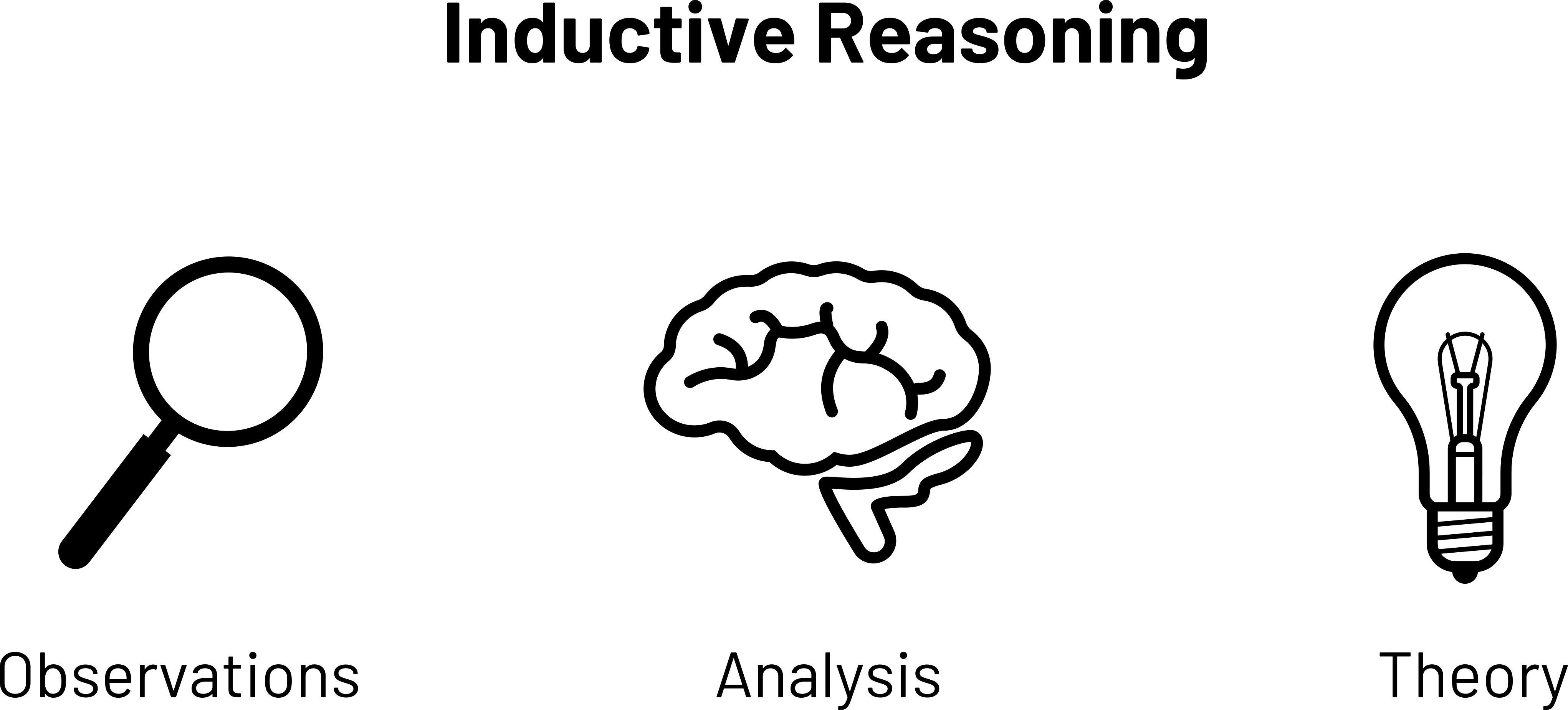

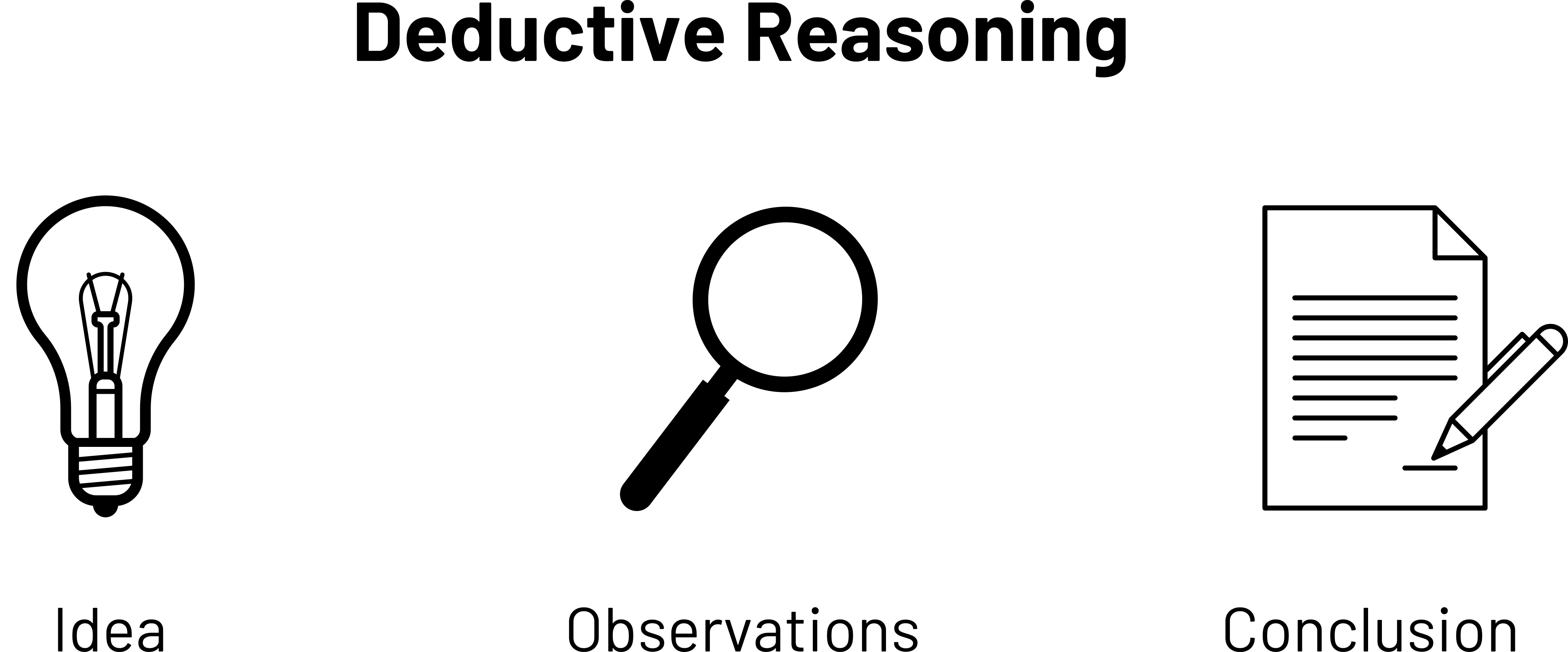

Reasoning refers to the process of making sense of things around us. In order to understand our experiences, draw conclusions from information, and present new ideas, we must use reasoning. We often reason without being aware of it, however, becoming more aware of how we think can empower us to be better producers and consumers of communicative messages. The three types of reasoning we will explore are inductive, deductive, and causal.

Inductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning reaches conclusions through the citation of examples and is the most frequently used form of logical reasoning (Walter, 1966). While introductory speakers are initially attracted to inductive reasoning because it seems easy, it can be difficult to employ well. Inductive reasoning, unlike deductive reasoning, does not result in true or false conclusions. Instead, since conclusions are generalized based on observations or examples, conclusions are “more likely” or “less likely.” Despite the fact that this type of reasoning is not definitive, it can still be valid and persuasive.

Some arguments based on inductive reasoning will be more cogent, or convincing and relevant, than others. For example, inductive reasoning can be weak when claims are made too generally. An argument that fraternities should be abolished from campus because they contribute to underage drinking and do not uphold high academic standards could be countered by providing examples of fraternities that sponsor alcohol education programming for the campus and have members that have excelled academically (Walter, 1966). In this case, one overly general claim is countered by another general claim, and both of them have some merit. It would be more effective to present a series of facts and reasons and then share the conclusion or generalization that you have reached from them.

You can see inductive reasoning used in the following speech excerpt from President George W. Bush’s address to the nation on the evening of September 11, 2001. Notice how he lists a series of events from the day, which builds to his conclusion that the terrorist attacks failed in their attempt to shake the foundation of America.

“Today, our fellow citizens, our way of life, our very freedom came under attack in a series of deliberate and deadly terrorist acts. The victims were in airplanes or in their offices: secretaries, business men and women, military and federal workers, moms and dads, friends, and neighbors. Thousands of lives were suddenly ended by evil, despicable acts of terror. The pictures of airplanes flying into building, fires burning, huge—huge structures collapsing have filled us with disbelief, terrible sadness, and a quiet unyielding anger. These acts of mass murder were intended to frighten our nation into chaos and retreat. But they have failed. Our country is strong. A great people has been moved to defend a great nation. Terrorist attacks can shake the foundations of our biggest buildings, but they cannot touch the foundation of America.”

If a speaker is able to provide examples that are concrete, proxemic, and relevant to the audience, as Bush did in this example, audience members are prompted to think of additional examples that connect to their own lives. Inductive reasoning can be useful when an audience disagrees with your proposition. As you present logically connected examples as evidence that build to a conclusion, the audience may be persuaded by your evidence before they realize that the coming conclusion will counter what they previously thought. This also sets up cognitive dissonance, which is a persuasive strategy we will discuss later.

Reasoning by analogy is a type of inductive reasoning that argues that what is true in one set of circumstances will be true in another (Walter, 1966). Reasoning by analogy has been criticized and questioned by logicians, since two sets of circumstances are never exactly the same. While this is true, our goal when using reasoning by analogy in persuasive speaking is not to create absolutely certain conclusions but to cite cases and supporting evidence that can influence an audience. For example, let’s say you are trying to persuade a university to adopt an alcohol education program by citing the program’s success at other institutions. Since two universities are never exactly the same, the argument cannot be airtight. To better support this argument, you could first show that the program was actually successful using various types of supporting material such as statistics from campus offices and testimony from students and staff. Second, you could show how the cases relate by highlighting similarities in the campus setting, culture, demographics, and previous mission. Since you cannot argue that the schools are similar in all ways, choose to highlight significant similarities. In addition, it is better to acknowledge significant limitations of the analogy and provide additional supporting material to address them than it is to ignore or hide such limitations.

So how do we evaluate inductive reasoning? When inductive reasoning is used to test scientific arguments, there is rigorous testing and high standards that must be met for a conclusion to be considered valid. Inductive reasoning in persuasive speaking is employed differently. A speaker cannot cite every example that exists to build to a conclusion, so to evaluate inductive reasoning you must examine the examples that are cited in ways other than quantity. First, the examples should be sufficient, meaning that enough are cited to support the conclusion. If not, you risk committing the hasty generalization fallacy. A speaker can expect that the audience will be able to think of some examples as well, so there is no set number on how many examples is sufficient. If the audience is familiar with the topic, then fewer examples are probably sufficient, while more may be needed for unfamiliar topics. A speaker can make his or her use of reasoning by example more powerful by showing that the examples correspond to the average case, which may require additional supporting evidence in the form of statistics. Arguing that teacher salaries should be increased by providing an example of a teacher who works side jobs and pays for his or her own school supplies could be effectively supported by showing that this teacher’s salary corresponds to the national average (Walter, 1966).

Second, the examples should be typical, meaning they were not cherry-picked to match the point being argued. A speaker who argues to defund the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) because the organization supports art that is “pornographic and offensive” may cite five examples of grants given for projects that caused such controversy. Failing to mention that these examples were pulled from the more than 128,000 grants issued by the NEA would be an inappropriate use of inductive reasoning since the examples are not sufficient or typical enough to warrant the argument. Another way to support inductive arguments is to show that the examples are a fair sample, meaning they are representative of the larger whole. Arguing that college athletes should not receive scholarships because they do not have the scholastic merit of other students and have less academic achievement could be supported by sharing several examples. However, if those examples were not representative, then they are biased, and the reasoning faulty. A speaker would need to show that the athletes used in the example are representative, in terms of their race, gender, sport, and background, of the population of athletes at the university.

Deductive Reasoning

Deductive reasoning derives specifics from what is already known. It was the preferred form of reasoning used by ancient rhetoricians like Aristotle to make logical arguments (Cooper & Nothstine, 1996).

A syllogism is an example of deductive reasoning that is commonly used when teaching logic. A syllogism is an example of deductive reasoning in which a conclusion is supported by major and minor premises. The conclusion of a valid argument can be deduced from the major and minor premises. A commonly used example of a syllogism is “All humans are mortal. Socrates is a human. Socrates is mortal.” In this case, the conclusion, “Socrates is mortal,” is derived from the major premise, “All humans are mortal,” and the minor premise, “Socrates is a human.” In some cases, the major and minor premises of a syllogism may be taken for granted as true. In the previous example, the major premise is presumed true because we have no knowledge of an immortal person to disprove the statement. The minor premise is presumed true because Socrates looks and acts like other individuals we know to be human. Detectives or scientists using such logic would want to test their conclusion. We could test our conclusion by stabbing Socrates to see if he dies, but since the logic of the syllogism is sound, it may be better to cut Socrates a break and deem the argument valid. Since most arguments are more sophisticated than the previous example, speakers need to support their premises with research and evidence to establish their validity before deducing their conclusion.

A syllogism can lead to incorrect conclusions if one of the premises is not true, as in the following example:

- All presidents have lived in the White House. (Major premise)

- George Washington was president. (Minor premise)

- George Washington lived in the White House. (Conclusion)

In the previous example, the major premise was untrue, since John Adams, our second president, was the first president to live in the White House. This causes the conclusion to be false. A syllogism can also exhibit faulty logic even if the premises are both true but are unrelated, as in the following example:

- Penguins are black and white. (Major premise)

- Some old television shows are black and white. (Minor premise)

- Some penguins are old television shows. (Conclusion)

Causal Reasoning

Causal reasoning argues to establish a relationship between a cause and an effect. When speakers attempt to argue for a particular course of action based on potential positive or negative consequences that may result, they are using causal reasoning. Such reasoning is evident in the following example: Eating more local foods will boost the local economy and make you healthier. The “if/then” relationship that is set up in causal reasoning can be persuasive, but the reasoning is not always sound. Rather than establishing a true cause-effect relationship, speakers more often set up a correlation, which means there is a relationship between two things but there are other contextual influences.

To use causal reasoning effectively and ethically, speakers should avoid claiming a direct relationship between a cause and an effect when such a connection cannot be proven. Instead of arguing “x caused y,” it is more accurate for a speaker to say “x influenced y.” Causal thinking is often used when looking to blame something or someone, as can be seen in the following example: It’s the president’s fault that the economy has not recovered more. While such a statement may garner a speaker some political capital, it is not based on solid reasoning.

Economic and political processes are too complex to distill to such a simple cause-effect relationship. A speaker would need to use more solid reasoning, perhaps inductive reasoning through examples, to build up enough evidence to support that a correlation exists and a causal relationship is likely. When using causal reasoning, present evidence that shows the following: (1) the cause occurred before the effect, (2) the cause led to the effect, and (3) it is unlikely that other causes produced the effect.

11.6 Persuasive Strategies

Do you think you are easily persuaded? If you are like most people, you are not swayed easily to change your mind about something. Persuasion is difficult because changing views often makes people feel like they were either not informed or ill informed, which also means they have to admit they were wrong about something. We will learn about nine persuasive strategies that you can use to influence more effectively audience members’ beliefs, attitudes, and values. They are ethos, logos, pathos, positive motivation, negative motivation, cognitive dissonance, appeal to safety needs, appeal to social needs, and appeal to self-esteem needs.

Ethos, Logos, and Pathos

Ethos, logos, and pathos were Aristotle’s three forms of rhetorical proof, meaning they were primary to his theories of persuasion. Ethos refers to the credibility of a speaker and includes three dimensions: competence, trustworthiness, and dynamism. The two most researched dimensions of credibility are competence and trustworthiness (Stiff & Mongeau, 2003).

Competence refers to the perception of a speaker’s expertise in relation to the topic being discussed. A speaker can enhance their perceived competence by presenting a speech based in solid research and that is well organized and practiced. Competent speakers must know the content of their speech and be able to deliver that content. Trustworthiness refers to the degree that audience members perceive a speaker to be presenting accurate, credible information in a non-manipulative way. Perceptions of trustworthiness come from the content of the speech and the personality of the speaker. In terms of content, trustworthy speakers consider the audience throughout the speech-making process, present information in a balanced way, do not coerce the audience, cite credible sources, and follow the general principles of communication ethics. In terms of personality, trustworthy speakers are also friendly and warm (Stiff & Mongeau, 2003).

Dynamism refers to the degree to which audience members perceive a speaker to be outgoing and animated (Stiff & Mongeau, 2003). Two components of dynamism are charisma and energy. Charisma refers to a mixture of abstract and concrete qualities that make a speaker attractive to an audience. Charismatic people usually know they are charismatic because they have been told that in their lives, and people have been attracted to them.

Unfortunately, charisma is difficult to develop intentionally, and some people seem to have a naturally charismatic personality, while others do not. Even though not everyone can embody the charismatic aspect of dynamism, the other component of dynamism, energy, is something that everyone can fathom. Communicating enthusiasm for your topic and audience by presenting relevant content and using engaging delivery strategies such as vocal variety and eye contact can increase your dynamism.

Logos refers to the reasoning or logic of an argument. The presence of fallacies would obviously undermine a speaker’s appeal to logos. Speakers employ logos by presenting credible information as supporting material and verbally citing their sources during their speech. Using the guidelines from our earlier discussion of reasoning will also help a speaker create a rational appeal. Research shows that messages are more persuasive when arguments and their warrants are made explicit (Stiff & Mongeau, 2003). Carefully choosing supporting material that is verifiable, specific, and unbiased can help a speaker appeal to logos. Speakers can also appeal to logos by citing personal experience and providing the credentials and/or qualifications of sources of information (Cooper & Nothstine, 1996). Presenting a rational and logical argument is important, but speakers can be more effective if they bring in and refute counterarguments. The most effective persuasive messages are those that present two sides of an argument and refute the opposing side, followed by single argument messages, followed by messages that present counterarguments but do not refute them (Stiff & Mongeau, 2003). In short, by clearly showing an audience why one position is superior to another, speakers do not leave an audience to fill in the blanks of an argument, which could diminish the persuasive opportunity.

Pathos refers to emotional appeals. Aristotle was suspicious of too much emotional appeal, yet this appears to have become more acceptable in public speaking. Stirring emotions in an audience is a way to get them involved in the speech, and involvement can create more opportunities for persuasion and action. Reading in the paper that a house was burglarized may get your attention but think about how different your reaction would be if you found out it was your own home. Intentionally stirring someone’s emotions to get them involved in a message that has little substance would be unethical. Yet such spellbinding speakers have taken advantage of people’s emotions to get them to support causes, buy products, or engage in behaviors that they might not otherwise, if given the chance to see the faulty logic of a message.

Effective speakers should use emotional appeals that are also logically convincing, since audiences may be suspicious of a speech that is solely based on emotion. Emotional appeals are effective when you are trying to influence a behavior or you want your audience to take immediate action (Stiff & Mongeau, 2003). Emotions lose their persuasive effect more quickly than other types of persuasive appeals. Since emotions are often reactionary, they fade relatively quickly when a person is removed from the provoking situation (Fletcher, 2001).

Emotional appeals are also difficult for some because they require honed delivery skills and the ability to use words powerfully and dramatically. The ability to use vocal variety, cadence, and repetition to rouse an audience’s emotion is not easily attained. Think of how stirring Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech was due to his ability to evoke the emotions of the audience. Dr. King used powerful and creative language in conjunction with his vocalics to deliver one of the most famous speeches in our history. Using concrete and descriptive examples can paint a picture in your audience member’s minds. Speakers can also use literal images, displayed using visual aids, to appeal to pathos.

Speakers should strive to appeal to ethos, logos, and pathos within a speech. A speech built primarily on ethos might lead an audience to think that a speaker is full of himself or herself. A speech full of facts and statistics appealing to logos would result in information overload. Speakers who rely primarily on appeals to pathos may be seen as overly passionate, biased, or unable to see other viewpoints.

Dissonance, Motivation, and Needs

Aristotle’s three rhetorical proofs—ethos, logos, and pathos—have been employed as persuasive strategies for thousands of years. More recently, persuasive strategies have been identified based on theories and evidence related to human psychology. Although based in psychology, such persuasive strategies are regularly employed and researched in communication due to their role in advertising, marketing, politics, and interpersonal relationships. The psychologically based persuasive appeals we will discuss are cognitive dissonance, positive and negative motivation, and appeals to needs.

Cognitive Dissonance

If you have studied music, you probably know what dissonance is. Some notes, when played together on a piano, produce a sound that is pleasing to our ears. When dissonant combinations of notes are played, we react by wincing or cringing because the sound is unpleasant to our ears. So dissonance is that unpleasant feeling we get when two sounds clash. The same principle applies to cognitive dissonance , which refers to the mental discomfort that results when new information clashes with or contradicts currently held beliefs, attitudes, or values. Using cognitive dissonance as a persuasive strategy relies on three assumptions: (1) people have a need for consistency in their thinking; (2) when inconsistency exists, people experience psychological discomfort; and (3) this discomfort motivates people to address the inconsistency to restore balance (Stiff & Mongeau, 2003). In short, when new information clashes with previously held information, an unpleasantness results, and we have to try to reconcile the difference.

Cognitive dissonance is not a single-shot persuasive strategy. As we have learned, people are resistant to change and not easy to persuade. While we might think that exposure to conflicting information would lead a rational person to change his or her mind, humans are not as rational as we think.

There are many different mental and logical acrobatics that people do to get themselves out of dissonance. Some frequently used strategies to resolve cognitive dissonance include discrediting the speaker or source of information, viewing yourself as an exception, seeking selective information that supports your originally held belief, or intentionally avoiding or ignoring sources of cognitive dissonance (Cooper & Nothstine, 1996). As you can see, none of those actually results in a person modifying their thinking, which means persuasive speech goals are not met. Of course, people cannot avoid dissonant information forever, so multiple attempts at creating cognitive dissonance can actually result in thought or behavior modification.

Positive and Negative Motivation

Positive and negative motivation are common persuasive strategies used by teachers, parents, and public speakers. Rewards can be used for positive motivation, and the threat of punishment or negative consequences can be used for negative motivation. We have already learned the importance of motivating an audience to listen to your message by making your content relevant and showing how it relates to their lives. We also learned an organizational pattern based on theories of motivation: Monroe’s Motivated Sequence. When using positive motivation , speakers implicitly or explicitly convey to the audience that listening to their message or following their advice will lead to positive results. Conversely, negative motivation implies or states that failure to follow a speaker’s advice will result in negative consequences. Positive and negative motivation as persuasive strategies match well with appeals to needs.

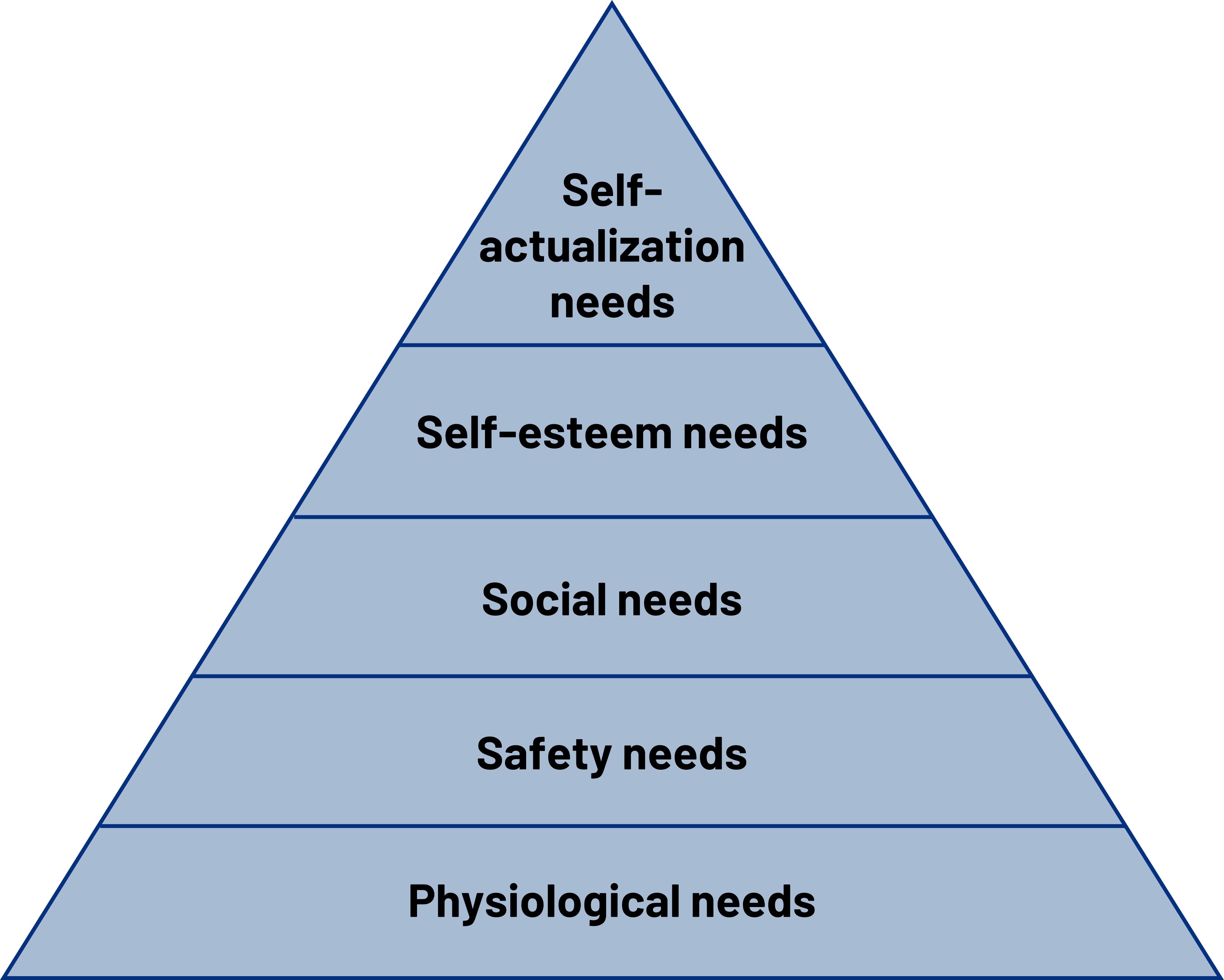

Appeals to Needs

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs states that there are several layers of needs that human beings pursue. They include physiological, safety, social, self-esteem, and self-actualization needs (Maslow, 1943). Since these needs are fundamental to human survival and happiness, tapping into needs is a common persuasive strategy. Appeals to needs are often paired with positive or negative motivation, which can increase the persuasiveness of the message.

Physiological needs form the base of the hierarchy of needs. The closer the needs are to the base, the more important they are for human survival. Speakers do not appeal to physiological needs. After all, a person who does not have food, air, or water is not very likely to want to engage in persuasion, and it would not be ethical to deny or promise these things to someone for persuasive gain. Some speakers attempt to appeal to self-actualization needs, but I argue that this is difficult to do ethically. Self-actualization refers to our need to achieve our highest potential, and these needs are much more intrapersonal than the others are. We achieve our highest potential through things that are individual to us, and these are often things that we protect from outsiders. Some examples include pursuing higher education and intellectual fulfillment, pursuing art or music, or pursuing religious or spiritual fulfillment. These are often things we do by ourselves and for ourselves, so I like to think of this as sacred ground that should be left alone. Speakers are more likely to be successful at focusing on safety, social, and self-esteem needs.

We satisfy our safety needs when we work to preserve our safety and the safety of our loved ones. Speakers can combine appeals to safety with positive motivation by presenting information that will result in increased safety and security. Combining safety needs and negative motivation, a speaker may convey that audience members’ safety and security will be put at risk if the speaker’s message is not followed. Combining negative motivation and safety needs depends on using some degree of fear as a motivator. Think of how the insurance industry relies on appeals to safety needs for their business. While this is not necessarily a bad strategy, it can be done more or less ethically.

Our social needs relate to our desire to belong to supportive and caring groups. We meet social needs through interpersonal relationships ranging from acquaintances to intimate partnerships. We also become part of interest groups or social or political groups that help create our sense of identity. The existence and power of peer pressure is a testament to the motivating power of social needs. People go to great lengths and sometimes make poor decisions they later regret to be a part of the “in-group.” Advertisers often rely on creating a sense of exclusivity to appeal to people’s social needs. Positive and negative motivation can be combined with social appeals. Positive motivation is present in messages that promise the receiver “in-group” status or belonging, and negative motivation can be seen in messages that persuade by saying, “Don’t be left out.” Although these arguments may rely on the bandwagon fallacy to varying degrees, they draw out insecurities people have about being in the “out-group.”

We all have a need to think well of ourselves and have others think well of us, which ties to our self-esteem needs . Messages that combine appeals to self-esteem needs and positive motivation often promise increases in respect and status. A financial planner may persuade by inviting a receiver to imagine prosperity that will result from accepting his or her message. A publicly supported radio station may persuade listeners to donate money to the station by highlighting a potential contribution to society. The health and beauty industries may persuade consumers to buy their products by promising increased attractiveness. While it may seem shallow to entertain such ego needs, they are an important part of our psychological makeup. Unfortunately, some sources of persuasive messages are more concerned with their own gain than the well-being of others and may take advantage of people’s insecurities in order to advance their persuasive message. Instead, ethical speakers should use appeals to self-esteem that focus on prosperity, contribution, and attractiveness in ways that empower listeners.

11.7 Sample Persuasive Speech

Title: Education behind Bars Is the Key to Rehabilitation

General purpose: To persuade

Specific purpose : By the end of my speech, my audience will believe that prisoners should have the right to an education.

Thesis statement: There should be education in all prisons, because denying prisoners an education has negative consequences for the prisoner and society, while providing them with an education provides benefits for the prisoner and society.

Attention getter: “We must accept the reality that to confine offenders behind walls without trying to change them is an expensive folly with short-term benefits—winning battles while losing the war.” Supreme Court Justice Warren Burger spoke these words more than thirty years ago, and they support my argument today that prisoners should have access to education.

Introduction of topic: While we value education as an important part of our society, we do not value it equally for all. Many people do not believe that prisoners should have access to an education, but I believe they do.

Credibility and relevance: While researching this topic, my eyes were opened up to how much an education can truly affect a prisoner, and given my desire to be a teacher, I am invested in preserving the right to learn for everyone, even if they are behind bars. While I know from our audience analysis activity that some of you do not agree with me, you never know when this issue may hit close to home. Someday, someone you love might make a mistake in their life and end up in prison, and while they are there, I know you all would want them to receive an education so that when they get out, they will be better prepared to contribute to society.

Preview: Today, I invite you listen with an open mind as I discuss the need for prisoner education, a curriculum that will satisfy that need, and some benefits of prisoner education.

Transition: First, I will explain why prisoners need access to education.

1. According to a 2012 article in the journal Corrections Today on correctional education programs, most states have experienced an increase in incarceration rates and budgetary constraints over the past ten years, which has led many to examine best practices for reducing prison populations.

a. In that same article, criminologist and former research director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons states that providing correctional education is one of the most productive and important reentry services that our prisons offer.

b. His claim is supported by data collected directly from prisoners, 94 percent of whom identify education as a personal reentry need—ranking it above other needs such as financial assistance, housing, or employment.

c. Despite the fact that this need is clearly documented, funding for adult and vocational education in correctional education has decreased.

1. Many prisoners have levels of educational attainment that are far below those in the general population.

2. According to statistics from 2010, as cited in the Corrections Today article, approximately 40 percent of state prison inmates did not complete high school, as compared to 19 percent of the general population.

3. Additionally, while about 48 percent of the public have taken college classes, only about 11 percent of state prisoners have.

d. At the skill level, research from the United Kingdom, cited in the 2003 article from Studies in the Education of Adults titled “Learning behind Bars: Time to Liberate Prison Education,” rates of illiteracy are much higher among the prison population than the general population, and there is a link between poor reading skills and social exclusion that may lead people to antisocial behavior.

1. Prisoner education is also needed to break a cycle of negativity and stigma to which many prisoners have grown accustomed.

2. The article from Studies in the Education of Adults that I just cited states that prisoners are often treated as objects or subjected to objectifying labels like “ addict , sexual offender , and deviant .”

3. While these labels may be accurate in many cases, they do not do much to move the prisoner toward rehabilitation.

4. The label student , however, has the potential to do so because it has positive associations and can empower the prisoner to make better choices to enhance his or her confidence and self-worth.

Transition: Now that I have established the need for prisoner education, let’s examine how we can meet that need.

2. In order to meet the need for prisoner education that I have just explained, it is important to have a curriculum that is varied and tailored to various prisoner populations and needs.

a. The article from Corrections Today notes that education is offered to varying degrees in most US prisons, but its presence is often debated and comes under increased scrutiny during times of budgetary stress.

b. Some states have implemented programs that require inmates to attend school for a certain amount of time if they do not meet minimum standards for skills such as reading or math.

c. While these are useful programs, prisoner education should not be limited to or focused on those with the least amount of skills.

d. The article notes that even prisoners who have attended or even graduated from college may benefit from education, as they can pursue specialized courses or certifications.

e. Based on my research, I would propose that the prison curriculum have four tiers: one that addresses basic skills that prisoners may lack, one that prepares prisoners for a GED, one that prepares prisoners for college-level work, and one that focuses on life and social skills.

1. The first tier of the education program should focus on remediation and basic skills, which is the most common form of prisoner education as noted by Foley and Gao in their 2004 article from the Journal of Correctional Education that studied educational practices at several institutions.

a. These courses will teach prisoners basic reading, writing, and math skills that may be lacking.

b. Since there is a stigma associated with a lack of these basic skills, early instruction should be one-one-one or in small groups.

2. The second tier should prepare prisoners who have not completed the equivalent of high school to progress on to a curriculum modeled after that of most high schools, which will prepare them for a GED.

3. The third tier should include a curriculum based on the general education learning goals found at most colleges and universities and/or vocational training.

a. Basic general education goals include speaking, writing, listening, reading, and math.

b. Once these general education requirements have been met, prisoners should be able to pursue specialized vocational training or upper-level college courses in a major of study, which may need to be taken online through distance learning, since instructors may not be available to come to the actual prisons to teach.

4. The fourth tier includes training in social and life skills that most people learn through family and peer connections, which many prisoners may not have had.

a. Some population-specific areas of study that would not be covered in a typical classroom include drug treatment and anger management.

b. Life skills such as budgeting, money management, and healthy living can increase confidence.

c. Classes that focus on social skills, parenting, or relational communication can also improve communication skills and relational satisfaction; for example, workshops teaching parenting skills have been piloted to give fathers the skills needed to communicate effectively with their children, which can increase feelings of self-worth.

f. According to a 2007 article by Behan in the Journal of Correctional Education , prisons should also have extracurricular programs that enhance the educational experience.

1. Under the supervision of faculty and/or staff, prisoners could be given the task of organizing an outside speaker to come to the prison or put together a workshop.

2. Students could also organize a debate against students on the outside, which could allow the prisoners to interact (face-to-face or virtually) with other students and allow them to be recognized for their academic abilities.

3. Even within the prison, debates, trivia contests, paper contests, or speech contests could be organized between prisoners or between prisoners and prison staff as a means of healthy competition.

4. Finally, prisoners who are successful students should be recognized and put into peer-mentoring roles, because, as Behan states in the article, “a prisoner who…has had an inspirational learning experience acts as a more positive advocate for the school than any [other method].”

Transition: The model for prisoner education that I have just outlined will have many benefits.

3. Educating prisoners can benefit inmates, those who work in prisons, and society.

a. The article I just cited from the Journal of Correctional Education states that the self-reflection and critical thinking that are fostered in an educational setting can help prisoners reflect on how their actions affected them, their victims, and/or their communities, which may increase self-awareness and help them better reconnect with a civil society and reestablish stronger community bonds.

1. The Corrections Today article I cited earlier notes that a federally funded three-state survey provided the strongest evidence to date that prisoner education reduces the recidivism rate and increases public safety.

2. The Corrections Today article also notes that prisoners who completed a GED reoffended at a rate 20 percent lower than the general prison population, and those that completed a college degree reoffended at a rate 44 percent lower than the general prison population.

b. So why does prisoner education help reduce recidivism rates?

1. Simply put, according to the article in the Studies in the Education of Adults I cited earlier, the skills gained through good prison education programs make released prisoners more desirable employees, which increases their wages and helps remove them from a negative cycles of stigma and poverty that led many of them to crime in the first place.

2. Further, the ability to maintain consistent employment has been shown to reduce the rate of reoffending.

3. Education does not just improve the lives of the prisoners; it also positively affects the people who work in prisons.

c. An entry on eHow.com by Kinney about the benefits of prisoners getting GEDs notes that a successful educational program in a prison can create a more humane environment that will positively affect the officers and staff as well.

1. Such programs also allow prisoners to do more productive things with their time, which lessens violent and destructive behavior and makes prison workers’ jobs safer.

2. Prisoner education can also save cash-strapped states money.

3. Giving prisoners time-off-sentence credits for educational attainment can help reduce the prison population, as eligible inmates are released earlier because of their educational successes.

4. As noted by the Corrections Today article, during the 2008–9 school year the credits earned by prisoners in the Indiana system led to more than $68 million dollars in avoided costs.

Transition to conclusion and summary of importance: In closing, it is easy to see how beneficial a good education can be to a prisoner. Education may be something the average teenager or adult takes for granted, but for a prisoner it could be the start of a new life.

Review of main points: There is a clear need for prisoner education that can be met with a sound curriculum that will benefit prisoners, those who work in prisons, and society.

Closing statement: While education in prisons is still a controversial topic, I hope you all agree with me and Supreme Court Justice Burger, whose words opened this speech, when we say that locking a criminal away may offer a short-term solution in that it gets the criminal out of regular society, but it doesn’t better the prisoner and it doesn’t better us in the long run as a society.

Figure 11.1: Types of propositions with examples. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 11.2: Inductive reasoning. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0 . Includes Lightbulb by Maxim Kulikov from NounProject , Magnifying Glass by Pedro Santos from NounProject , and Brain by Bernar Novalyi from NounProject (all Noun Project license ).

Figure 11.3: Deductive reasoning. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0 . Includes Lightbulb by Maxim Kulikov from NounProject , Magnifying Glass by Pedro Santos from NounProject , and Paper by AdbA Icons ❤️ from NounProject (all Noun Project license ).

Figure 11.4: Aristotle’s modes of persuassion. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 11.5: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0 .

Section 11. 1-11.4

Barton, K., & Tucker, B. G. (2021, February 20). Constructing a persuasive speech . https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Communication/Public_Speaking/Exploring_Public_Speaking_(Barton_and_Tucker)/13%3A_Persuasive_Speaking/13.05%3A_Constructing_a_Persuasive_Speech

Hamm, P. H. (2006). Teaching and persuasive communication: Class presentation skills . Harriet W. Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning at Brown University.

Macasieb, D. (2018, June 13). Speech patterns: The proposition-to-proof versus the problem-solution method . https://drumac.com/2018/06/13/speech-patterns-the-proposition-to-proof-versus-the-problem-solution-method/

McCroskey, J. C. (1966). Toward an understanding of the importance of ‘evidence’ in persuasive communication. The Pennsylvania Speech Annual , 23 , 65–71.

McCroskey, J. C. (1969). A summary of experimental research on the effects of evidence in persuasive communication. Quarterly Journal of Speech , 55 (2), 169-176. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335636909382942

Nordquist, R. (2020, December 3). What does it mean to make a claim during an argument? https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-claim-argument-1689845

Poggi, I. (2005). The goals of persuasion. Pragmatics and Cognition , 13 (2), 297-335. https://doi.org/10.1075/pc.13.2.04pog

Watt, S. S., & Barnett, J. T. (2021, January 4). Organizing persuasive messages . https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Communication/Public_Speaking/Public_Speaking_(The_Public_Speaking_Project)/16%3A_Persuasive_Speaking/16.09%3A_Organizing_Persuasive_Messages

Williams, E. (2018, October 19). Effective persuasive communication . https://smallbusiness.chron.com/effective-persuasive-communication-56248.html

Section 11.5

ReferencesCooper, M. D., & Nothstine, W. L. (1996). Power persuasion: Moving an ancient art into the media age. Educational Video Group.

Walter, O. M., Speaking to inform and persuade . Macmillan.

Section 11.6

Cooper, M. D., & Nothstine, W. L. (1996). Power persuasion: Moving an ancient art into the media age . Educational Video Group.

Fletcher, L. (2001). How to design and deliver speeches (7th ed.). Longman.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50 (4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Stiff, J. B., & Mongeau, P. A. (2003). Persuasive communication (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Sample Persuasive Speech

Bayliss, P. (2003). Learning behind bars: Time to liberate prison education. Studies in the Education of Adults, 35 (2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2003.11661480

Behan, C. (2007). Context, creativity and critical reflection: Education in correctional institutions. Journal of Correctional Education, 58 (2), 157–169. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23282734

Foley, R. M., & Gao, J. (2004). Correctional education: Characteristics of academic programs serving incarcerated adults. Journal of Correctional Education, 55 (1), 6–21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23292120

Kinney, A. (2011). What are the benefits of inmates getting GEDs? Ehow.com . Retrieved from https://ehow.com/list_6018033_benefits-inmates-getting-geds_.html

Steurer, S. J., Linton, J., Nally, J., & Lockwood, S. (2010). The top-nine reasons to increase correctional education programs. Corrections Today, 72 (4), 40–43.

The statement that will be supported by evidence

Also called grounds, it supports the claim

The underlying justification that connects the claim and the evidence

A five step organizational pattern to help persuade an audience. 1. Attention Step: Grab the audience’s attention in the introduction. 2. Need Step: Establish the reason that your topic needs to be addressed. Satisfaction Step: Present a solution to the problem that you are addressing. 4. Visualization Step: Incorporate a positive/negative motivation to support the relationship you have set up between the need and your proposal. 5. Action Step: Include a call to action that tells people what they can do about the situation.

Reaches conclusions through citation of examples and is the most frequently used form of logical reasoning

Derives specifics from what is already known

Argues to establish a relationship between a cause and effect

Refers to the credibility of the speaker and includes dimensions: competence, trustworthiness, and dynamism

Refers to the perception of a speaker’s expertise in relation to the topic being discussed

The second component of ethos and is the degree that audience members perceive a speaker to be presenting accurate, credible information in a non-manipulative way

Refers to the degree to which audience members perceive a speaker to be outgoing and animated

The reasoning or logic of an argument

The emotional appeal

Refers to the mental discomfort that results when new information clashes with or contradicts currently held beliefs, attitudes, or values

Communication in the Real World Copyright © by Faculty members in the School of Communication Studies, James Madison University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Learning Objectives

- Define persuasive speaking

- Explore organizational patterns for persuasive speeches

Explain the barriers to persuading an audience

- Identify common logical fallacies

On the first day of class, your instructor provided you a “lay of the land.” They introduced you to course documents, the syllabus, and reading materials.

“It’s important that you read your textbook,” they likely shared. “The material will allow you to dive deeper into the course material and, even if you don’t initially realize its importance, the reading material will build throughout the semester. The time spent reading will be worth it because without that knowledge, it will be difficult to complete assignments and receive full credit. The time spent reading will benefit you after you leave for the semester, too, and you’ll have critical thinking skills that will permeate your life out of the classroom.” Sound familiar?

This is persuasion. Your instructor is persuading you that reading the textbook is a good idea—that it’s an action that you should take throughout the semester. As an audience member, you get to weigh the potential benefits of reading the textbook in relation to the consequences. But if your instructor has succeeded in their persuasive attempt, you will read the book because they have done a good job of helping you to conclude in favor of their perspective.

Persuasion is everywhere. We are constantly inundated with ideas, perspectives, politics, and products that are requesting our attention. Persuasion is often positively paired with ideas of encouragement, influence, urging, or logic. Your instructors, for example, are passionate about the subject position and want you to succeed in the class. Sadly, persuasion can also be experienced as manipulation, force, lack of choice, or inducement. You might get suspicious if you think someone is trying to persuade you. You might not appreciate someone telling you to change your viewpoints.

In this chapter, we explore persuasive speaking and work through best practices in persuasion. Because persuasion is everywhere, being critical and aware of persuasive techniques will allow you to both ethically persuade audiences and evaluate arguments when others attempt to persuade you. We’ll start with the basics by answering the question, “what is persuasion?”

Introducing Persuasive Speaking

Persuasion is “the process of creating, reinforcing, or changing people’s beliefs or actions” (Lucas, 2015, p. 306). Persuasion is important in all communication processes and contexts—interpersonal, professional, digital—and it’s something that you do every day. Convincing a friend to go see the latest movie instead of staying in to watch TV; giving your instructor a reason to give you an extension on an assignment; writing a cover letter and resume and going through an interview for a job—all of these and so many more are examples of persuasion. In fact, it is hard to think of life without the everyday give-and-take of persuasion. In each example listed, Lucas’s definition of persuasion is being implemented: you are asking a person or group to agree with your main idea.

When using persuasion in a public speech, the goal is to create, change, or reinforce a belief or action by addressing community problems or controversies. Remember that public speaking is a long-standing type of civic engagement; when we publicly speak, we are participating in democratic deliberation. Deliberatio n , or the process of discussing feasible choices that address community problems, is important in resolving community concerns because it allows all perspectives to be considered. Persuasive speaking means addressing a public controversy and advocating for a perspective that the speaker hopes the audience will adopt. If the issue isn’t publicly controversial – if everyone agrees or if there are not multiple perspectives – you are not persuading. You’re informing.

So, what’s a public controversy? Public controversies are community disputes that affect a large number of people. Because they involve a large number of people, public controversies often have multiple perspectives, leading to public deliberation and debate to resolve each dispute.