Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Organization and Structure

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

There is no single organizational pattern that works well for all writing across all disciplines; rather, organization depends on what you’re writing, who you’re writing it for, and where your writing will be read. In order to communicate your ideas, you’ll need to use a logical and consistent organizational structure in all of your writing. We can think about organization at the global level (your entire paper or project) as well as at the local level (a chapter, section, or paragraph). For an American academic situation, this means that at all times, the goal of revising for organization and structure is to consciously design your writing projects to make them easy for readers to understand. In this context, you as the writer are always responsible for the reader's ability to understand your work; in other words, American academic writing is writer-responsible. A good goal is to make your writing accessible and comprehensible to someone who just reads sections of your writing rather than the entire piece. This handout provides strategies for revising your writing to help meet this goal.

Note that this resource focuses on writing for an American academic setting, specifically for graduate students. American academic writing is of course not the only standard for academic writing, and researchers around the globe will have different expectations for organization and structure. The OWL has some more resources about writing for American and international audiences here .

Whole-Essay Structure

While organization varies across and within disciplines, usually based on the genre, publication venue, and other rhetorical considerations of the writing, a great deal of academic writing can be described by the acronym IMRAD (or IMRaD): Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. This structure is common across most of the sciences and is often used in the humanities for empirical research. This structure doesn't serve every purpose (for instance, it may be difficult to follow IMRAD in a proposal for a future study or in more exploratory writing in the humanities), and it is often tweaked or changed to fit a particular situation. Still, its wide use as a base for a great deal of scholarly writing makes it worthwhile to break down here.

- Introduction : What is the purpose of the study? What were the research questions? What necessary background information should the reader understand to help contextualize the study? (Some disciplines include their literature review section as part of the introduction; some give the literature review its own heading on the same level as the other sections, i.e., ILMRAD.) Some writers use the CARS model to help craft their introductions more effectively.

- Methods: What methods did the researchers use? How was the study conducted? If the study included participants, who were they, and how were they selected?

- Results : This section lists the data. What did the researchers find as a result of their experiments (or, if the research is not experimental, what did the researchers learn from the study)? How were the research questions answered?

- Discussion : This section places the data within the larger conversation of the field. What might the results mean? Do these results agree or disagree with other literature cited? What should researchers do in the future?

Depending on your discipline, this may be exactly the structure you should use in your writing; or, it may be a base that you can see under the surface of published pieces in your field, which then diverge from the IMRAD structure to meet the expectations of other scholars in the field. However, you should always check to see what's expected of you in a given situation; this might mean talking to the professor for your class, looking at a journal's submission guidelines, reading your field's style manual, examining published examples, or asking a trusted mentor. Every field is a little different.

Outlining & Reverse Outlining

One of the most effective ways to get your ideas organized is to write an outline. A traditional outline comes as the pre-writing or drafting stage of the writing process. As you make your outline, think about all of the concepts, topics, and ideas you will need to include in order to accomplish your goal for the piece of writing. This may also include important citations and key terms. Write down each of these, and then consider what information readers will need to know in order for each point to make sense. Try to arrange your ideas in a way that logically progresses, building from one key idea or point to the next.

Questions for Writing Outlines

- What are the main points I am trying to make in this piece of writing?

- What background information will my readers need to understand each point? What will novice readers vs. experienced readers need to know?

- In what order do I want to present my ideas? Most important to least important, or least important to most important? Chronologically? Most complex to least complex? According to categories? Another order?

Reverse outlining comes at the drafting or revision stage of the writing process. After you have a complete draft of your project (or a section of your project), work alone or with a partner to read your project with the goal of understanding the main points you have made and the relationship of these points to one another. The OWL has another resource about reverse outlining here.

Questions for Writing Reverse Outlines

- What topics are covered in this piece of writing?

- In what order are the ideas presented? Is this order logical for both novice and experienced readers?

- Is adequate background information provided for each point, making it easy to understand how one idea leads to the next?

- What other points might the author include to further develop the writing project?

Organizing at the sentence and paragraph level

Signposting.

Signposting is the practice of using language specifically designed to help orient readers of your text. We call it signposting because this practice is like leaving road signs for a driver — it tells your reader where to go and what to expect up ahead. Signposting includes the use of transitional words and phrasing, and they may be explicit or more subtle. For example, an explicit signpost might say:

This section will cover Topic A and Topic B.

A more subtle signpost might look like this:

It's important to consider the impact of Topic A and Topic B.

The style of signpost you use will depend on the genre of your paper, the discipline in which you are writing, and your or your readers’ personal preferences. Regardless of the style of signpost you select, it’s important to include signposts regularly. They occur most frequently at the beginnings and endings of sections of your paper. It is often helpful to include signposts at mid-points in your project in order to remind readers of where you are in your argument.

Questions for Identifying and Evaluating Signposts

- How and where does the author include a phrase, sentence, or short group of sentences that explains the purpose and contents of the paper?

- How does each section of the paper provide a brief summary of what was covered earlier in the paper?

- How does each section of the paper explain what will be covered in that section?

- How does the author use transitional words and phrases to guide readers through ideas (e.g. however, in addition, similarly, nevertheless, another, while, because, first, second, next, then etc.)?

WORKS CONSULTED

Clark, I. (2006). Writing the successful thesis and dissertation: Entering the conversation . Prentice Hall Press.

Davis, M., Davis, K. J., & Dunagan, M. (2012). Scientific papers and presentations . Academic press.

Organizational Structures Essay

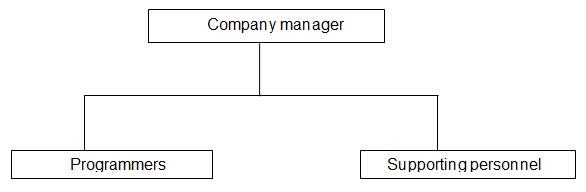

Functional organizational structure is ideal for the company 1. Its structure should have two functional levels: managerial team at the top level hierarchy while programmers and supporting personnel – under it. Below, there is a chart to illustrate company 1 functional organizational structure:

Each employee in all the levels has a task to perform in relation to their specialization. The company 1 top level hierarchy is headed by managers who have the following roles: they are responsible for planning and making strategic decisions, passing decisions to employees and controlling implementation of these decisions. They also control tasks realization process. Managers’ offices should be located in the company’s main office Ar-Riyad. All the 25 programmers and the supporting personnel are answerable to the management.

Level two of the company’s hierarchy is the programmers and the supporting personnel. Each of this team has specialization in their functional roles. The programmers search for clients, provide technical support to their clients and do programming. The rationale for choosing this type of organizational structure for the company 1 is that each of the workers in this company has a specific task to perform depending on the specialization.

For instance, the programmers have specific tasks to accomplish in addition to searching for clients, providing technical support to company’s client and doing programming. Company managers have responsibility of staffing, controlling and coordinating the company activities. Supporting employees are supposed to facilitate company functions for it to achieve its goal. Also, they are a part of communication link between the management and the other company personnel.

Functional organization structure is suitable for this company because it has bigger software market. For instance, it has ten company clients from Ar-Riyad, two from Damman, one multinational company that specializes in business software and two other clients from Argentina.

In addition, its activity coordination and specialization are centralized. Its managers oversee the company task coordination and specialization. To achieve its goals this company has to divide its operation according to functional areas in addition to possessing various levels of authority.

Command flow is from the top (management) to those below (employees) in hierarchy. This structure will allow economies of scale within all company 1 functional departments. Additionally, it will enable depth knowledge and skill development and company’s accomplishment of its functional goals. It is also bested suited for company with one product like company 1.

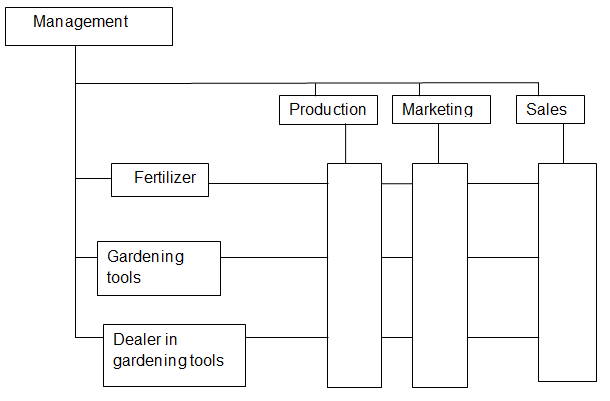

Matrix organizational structure is suitable for the company 2 because it can allow this company to address multiple business dimensions using multiple command structure. Below, there is a chart to illustrate the company 2 matrix organizational structure.

In the company 2, management coordinates the activities of all other departments in the company. It is the highest level in the organization hierarchy. Command flows from the management to all other departments in the organization. Company’s managers occupy the highest post in the company’s central administration who are responsible for planning and making strategic decisions. They also pass decision to employees and control implementation of these decisions.

They also control tasks realization process. Managerial team decision is the implementation affect of all products of company which include fertilizer, gardening, and dealers in gardening tools. Employees are supposed to give feed back to management on matters concerning the company operations. The company 2 has many employees working in various departments of the company including production, marketing and sales. Out of the 250 employees, 100 are occupied in the production sector.

Its central offices are suited in Damman. Employees who have similar skills are put together for particular task. For instance, those employees working in production sector should report to a production manager, sales and marketing employee should report to sales and marketing managers respectively.

Rationale for using Matrix organizational structure, it is because Matrix organizational structure encourages innovation and fast action and speed information in the company. Additionally, Matrix organizational structure is suitable for a company which deals with more than one product.

The company 2 is involved in production of fertilizer, manufacturing of gardening tools and dealer in gardening tools for the famous U.S brand. Matrix organizational structure fits this company because its workers are selected according to the task needed. Departmental flexibility is of essential in running this company in various departments.

Matrix organizational structure is able to leverage functional economies of scale while remaining small task focused; it focuses employees on multiple business goals and facilitates innovation solution to complex and technical problems. It improves employees’ companywide focus through increased responsibility and decision making. It also allows a quick and easy transfer of resources and increases information flow through the creation of lateral communication channels and enhances personal communication skills.

In order for a company to attain its objectives, its organization’s structure should have tasks allocation, coordination and supervision. Organizational structure is a key determinant in any organization’s operations and performance. Companies have different organizational structure depending on their goals.

Organization structure enables an organization’s tasks, activities and processes allocation to its personnel, departments or branches. Basically, organizational structure serves two main purposes in an organization. They include forming a basis guide lines in any operations. It also defines company’s workers and departments duties to gear towards achieving it goal.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 29). Organizational Structures. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organizational-structures/

"Organizational Structures." IvyPanda , 29 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/organizational-structures/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Organizational Structures'. 29 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Organizational Structures." February 29, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organizational-structures/.

1. IvyPanda . "Organizational Structures." February 29, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organizational-structures/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Organizational Structures." February 29, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organizational-structures/.

- Building a Sky Garden: Vertical Farming System Business Plan

- A Marketing Plan for Rental Community Gardens

- Career Options for a Computer Programmer

- Factors that influence Job Satisfaction

- Managing Job Applications

- Unethical business research conduct

- Sweatshops in the United States

- Goodrich A7D's Scandal

Search form

- Table of Contents

- Troubleshooting Guide

- A Model for Getting Started

- Justice Action Toolkit

- Best Change Processes

- Databases of Best Practices

- Online Courses

- Ask an Advisor

- Subscribe to eNewsletter

- Community Stories

- YouTube Channel

- About the Tool Box

- How to Use the Tool Box

- Privacy Statement

- Workstation/Check Box Sign-In

- Online Training Courses

- Capacity Building Training

- Training Curriculum - Order Now

- Community Check Box Evaluation System

- Build Your Toolbox

- Facilitation of Community Processes

- Community Health Assessment and Planning

- Section 1. Organizational Structure: An Overview

Chapter 9 Sections

- Section 2. Creating and Gathering a Group to Guide Your Initiative

- Section 3. Developing Multisector Task Forces or Action Committees for the Initiative

- Section 4. Developing an Ongoing Board of Directors

- Section 5. Welcoming and Training New Members to a Board of Directors

- Section 6. Maintaining a Board of Directors

- Section 7. Writing Bylaws

- Section 8. Including Youth on Your Board, Commission, or Committee

- Section 9. Understanding and Writing Contracts and Memoranda of Agreement

- Main Section

What is organizational structure?

Why should you develop a structure for your organization, when should you develop a structure for your organization.

By structure, we mean the framework around which the group is organized, the underpinnings which keep the coalition functioning. It's the operating manual that tells members how the organization is put together and how it works. More specifically, structure describes how members are accepted, how leadership is chosen, and how decisions are made.

- Structure gives members clear guidelines for how to proceed. A clearly-established structure gives the group a means to maintain order and resolve disagreements.

- Structure binds members together. It gives meaning and identity to the people who join the group, as well as to the group itself.

- Structure in any organization is inevitable -- an organization, by definition , implies a structure. Your group is going to have some structure whether it chooses to or not. It might as well be the structure which best matches up with what kind of organization you have, what kind of people are in it, and what you see yourself doing.

It is important to deal with structure early in the organization's development. Structural development can occur in proportion to other work the organization is doing, so that it does not crowd out that work. And it can occur in parallel with, at the same time as, your organization's growing accomplishments, so they take place in tandem, side by side. This means that you should think about structure from the beginning of your organization's life. As your group grows and changes, so should your thinking on the group's structure.

Elements of Structure

While the need for structure is clear, the best structure for a particular coalition is harder to determine. The best structure for any organization will depend upon who its members are, what the setting is, and how far the organization has come in its development.

Regardless of what type of structure your organization decides upon, three elements will always be there. They are inherent in the very idea of an organizational structure.

- Some kind of governance

Rules by which the organization operates

- A distribution of work

The first element of structure is governance - some person or group has to make the decisions within the organization.

Another important part of structure is having rules by which the organization operates. Many of these rules may be explicitly stated, while others may be implicit and unstated, though not necessarily any less powerful.

Distribution of work

Inherent in any organizational structure also is a distribution of work. The distribution can be formal or informal, temporary or enduring, but every organization will have some type of division of labor.

There are four tasks that are key to any group:

- Envisioning desired changes . The group needs someone who looks at the world in a slightly different way and believes he or she can make others look at things from the same point of view.

- Transforming the community . The group needs people who will go out and do the work that has been envisioned.

- Planning for integration . Someone needs to take the vision and figure out how to accomplish it by breaking it up into strategies and goals.

- Supporting the efforts of those working to promote change . The group needs support from the community to raise money for the organization, champion the initiative in the state legislature, and ensure that they continue working towards their vision.

Common Roles

Every group is different, and so each will have slightly different terms for the roles individuals play in their organization, but below are some common terms, along with definitions and their typical functions.

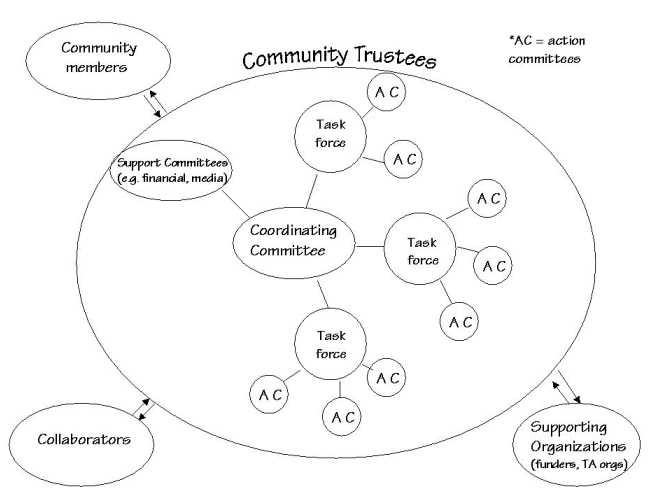

- An initial steering committee is the group of people who get things started. Often, this group will create plans for funding, and organizational and board development. It may also generate by-laws, and then dissolve. If they continue to meet after approximately the first six months, we might say they have metamorphosed into a coordinating council .

- A coordinating council (also referred to as a coordinating committee, executive committee , and executive council ), modifies broad, organization-wide objectives and strategies in response to input from individuals or committees.

- Often, one person will take the place of the coordinating council, or may serve as its head. Such a person may be known as the Executive Director, Project Coordinator, Program Director, or President . He or she sometimes has a paid position, and may coordinate, manage, inspire, supervise, and support the work of other members of the organization.

- Task forces are made up of members who work together around broad objectives. Task forces integrate the ideas set forward with the community work being done.

For example, from the director of a coalition to reduce violence in a medium-sized city: "Currently, we have three operational task forces. Members of each have an ongoing dialogue with members of the coordinating council, and also with their action committees. The oldest was formed with the goal of eliminating domestic violence about fifteen years ago, when a local woman was killed by her husband. Then, after several outbreaks of violence in the schools a few years back, our group offered to help, and a second task force sprung up around reducing youth violence. We've just started a third, with the goal of increasing gun safety. "All of it is interrelated, and all of it applies to our mission of increasing the safety of residents of South Haven, as well as that of our visitors. But each task force is contributing to that mission in vastly different ways, with different objectives, and using different strategies. 'Cause, you know, the strategies you use to stop a ninth grader from bringing a gun to school just aren't the same as the ones you use to stop a 40-year-old man on unemployment from beating his wife."

- Action committees bring about specific changes in programs, policies, and practices in the sectors in which they work.

For example, the task force on domestic violence mentioned above has the following action committees: A government and law enforcement committee . Members include police officers, lawyers, a judge, and a state representative. Currently, they are trying to pass laws with stronger penalties for those convicted of domestic violence, especially repeat offenders. They are also training officers to be better able to spot an abusive relationship, and better able to inform a victim of his or her options. A social services committee . Members (who include representatives from most of the service agencies in town) work to assure that staff members know where to send someone for the resources he or she needs. They are also trying to increase the number of trained volunteer counselors who work at the battered women's shelter. A media committee . Members include local journalists, writers, and graphic designers. They keep the project and the issue in the public's minds as much as possible with editorials, articles and news clips of events, as well as advertisements and public service announcements.

- Support committees are groups that help ensure that action committees or other individuals will have the resources and opportunities necessary to realize their vision. Financial and media committees are examples of committees formed to help support or facilitate your work.

- Community trustees , also known as the board of trustees or as the board of directors , provide overall support, advice, and resources to members of the action groups. They are often either people who are directly affected by the issue or have stature in the community. That way, they are able to make contacts, network with other community leaders, and generally remove or weaken barriers to meeting organizational objectives.

- Grantmakers are another part of the picture. Grantmakers exist on an international, national, state, and local level and may be private companies and foundations, or local, county, state, or federal government organizations (for example, block grants given by the city would fall into this category).

- Support organizations (not to be confused with the support committees listed above) are groups that can give your organization the technical assistance it needs.

- Partner organizations are other groups working on some of the same issues as your organization.

Although this list is pretty extensive, your organization may only use two or three of the above mentioned roles, especially at the beginning. It's not uncommon for a group to start with a steering committee, ask others to serve as board members, and then recruit volunteers who will serve as members of action committees. In this broad spectrum of possibilities, consider: Where does your organization fit in? Where do you want to be?

Examples of Structure

So how can all of these pieces be put together? Again, the form a community group takes should be based on what it does , and not the other way around. The structures given are simply meant to serve as examples that have been found to be effective for some community-based organizations; they can and should be adapted and modified for your own group's purposes.

A relatively complex structure

Example - The Ste. Genevieve's Children's Coalition The Ste. Genevieve's Children's Coalition is a relatively large community-based group. They have a coordinating council, a media committee, and three task forces, dealing with adolescent pregnancy, immunization, and child hunger. Each of the task forces has action committees as well. For example, the adolescent pregnancy reduction task force has a schools committee that focuses on keeping teen parents in school and modifying the human sexuality curriculum. A health organizations committee focuses on increasing access and use of the youth clinic. The media committee works to keep children's issues in the news, and includes professionals from the local television stations, radio stations, newspaper, and a marketing professional. The coordinating council is composed of the executive director, her assistant, the media committee chair, and the chairs of each of the three task forces. A board of directors has been invaluable in helping keep the coalition financially viable.

In diagram form, a complex organization might look like this:

And in diagram form:

As smaller size means fewer people, these groups are usually less complex, as they have less need for a formal hierarchy and instead have governance that is consensus-based. A diagram of such a small group might look something like this, with each of the circles representing an individual member:

What type of structure should you choose?

First, decide upon the formality your organization will have. The following table, adapted from The Spirit of Coalition Building can help you make this first decision.

Organizational structure is something that is best decided upon internally, through a process of critical thinking and discussion by members of the group.

In your discussions, your answers to the following list of questions may guide your decisions.

- What is your common purpose? How broad is it? Groups with broader purposes often have more complicated structures, complete with many layers and parts, than do groups with more narrow purposes.

- Is your group advocacy oriented or service oriented? Service organizations use "top down," one-person-in-charge structure much more often than do advocacy based groups.

- Is your organization more centralized (e.g., through the work of a specific agency ) or decentralized (e.g., different neighborhoods working independently on the same problem)? A decentralized group might find a "top-down" structure inappropriate, as such a group often has several peers working together on an issue.

- How large is your organization? How large do you envision it becoming? A very small organization may wish to remain relatively informal, while a community-wide group might require a more formal structure. A related question, with similar consequences, is:

- How large is the community in which you work?

- How old is your organization? How long do you envision it lasting? A group formed to resolve a single issue might not need a formal structure at all, while an organization with long-term goals may want something more concrete, with clearer divisional responsibilities and authority.

- Is the organization entirely volunteer, or are there (or will there be) paid staff? How many? An organization with many paid staff members may find it more necessary to have people "in charge," as there are generally more rules and responsibilities for paid staff members, and thus, there must be more supervision in carrying out these roles.

- Should yours be a new organization, or part of an existing structure? Do you really need to form a new structure, or would it be better to work within existing structures? Sometimes, your goals may be better met if you are part of (or linked with) another organization.

Structure is what ensures that your organization will function smoothly and as you intended. You should think about structure early in the development of your organization, but be aware that the type that fits best may change as your organization grows.

Online Resources

How to Develop an Organization Structure , by Tara Duggan, Demand Media, is an informational article on how to develop organization structure with a short step-by-step analysis.

It's All About the Base: A Guide to Building a Grassroots Organizing Program from Community Catalyst.

Module 2: Organizational Structure , by Pathfinder International, is a concise manual describing pros and cons, together with suggestions for how one might change the organizational structure one has.

Print Resources

Berkowitz, W., & Wolff, T. (1999). The spirit of coalition building. Washington , DC: American Public Health Association.

Unterman, I. & Davis, R. (1984). Strategic management of not-for-profit organizations: From survival to success . New York, NY: Praeger.

10.1 Organizational Structures and Design

- What are mechanistic versus organic organizational structures?

First, an organizational structure is a system for accomplishing and connecting the activities that occur within a work organization. People rely on structures to know what work they should do, how their work supports or relies on other employees, and how these work activities fulfill the purpose of the organization itself.

Second, organizational design is the process of setting up organizational structures to address the needs of an organization and account for the complexity involved in accomplishing business objectives.

Next, organizational change refers to the constant shifts that occur within an organizational system—for example, as people enter or leave the organization, market conditions shift, supply sources change, or adaptations are introduced in the processes for accomplishing work. Through managed change , leaders in an organization can intentionally shape how these shifts occur over time.

Finally, organizational development (OD) is the label for a field that specializes in change management. OD specialists draw on social science to guide change processes that simultaneously help a business achieve its objectives while generating well-being for employees and sustainable benefits for society. An understanding of OD practices is essential for leaders who want to maximize the potential of their organizations over a long period of time.

Together, an understanding of these concepts can help managers know how to create and direct organizations that are positioned to successfully accomplish strategic goals and objectives. 1

To understand the role of organizational structure, consider the experience of Justin, a young manager who worked for a logistics and transportation company. Their success at leading change in the United States gave their leaders the confidence that Justin could handle a challenging assignment: organize a new supply chain and distribution system for a company in Northern Europe. Almost overnight, Justin was responsible for hiring competent people, forming them into a coherent organization, training them, and establishing the needed infrastructure for sustained success in this new market.

If you were given this assignment, what would you do? How would you organize your employees? How would you help them understand the challenge of setting up a new organization and system? These are the kinds of questions that require an understanding of organizational structure, organizational design, organizational change, and organizational development.

One of the first issues Justin will need to address deals with how they will organize the system. “The decisions about the structure of an organization are all related to the concept of organizational design. There are two fundamental forms of structure to remember when designing an organization.

To address these questions, we need to be familiar with two fundamental ways of building an organization.

The formal organization is an officially defined set of relationships, responsibilities, and connections that exist across an organization. The traditional organizational chart, as illustrated in Exhibit 10.2 , is perhaps the most common way of depicting the formal organization. The typical organization has a hierarchical form with clearly defined roles and responsibilities.

When Justin sets up the formal organization, they will need to design the administrative responsibilities and communication structures that should function within an organizational system. The formal systems describe how flow of information and resources should occur within an organization. To establish the formal organization, they will identify the essential functions that need to be part of the system, and they will hire people to fill these functions. They will then need to help employees learn their functions and how these functions should relate to one another.

The informal organization is sometimes referred to as the invisible network of interpersonal relationships that shape how people actually connect with one another to carry out their activities. The informal organization is emergent, meaning that it is formed through the common conversations and relationships that often naturally occur as people interact with one another in their day-to-day relationships. It is usually complex, impossible to control, and has the potential to significantly influence an organization’s success.

As depicted in Exhibit 10.3 , the informal organization can also be mapped, but it is usually very different than the formal organization. The chart you see in this example is called a network map, because it depicts the relationships that exist between different members of a system. Some members are more central than others, and the strength of relationships may vary between any two pairs or groups of individuals. These relationships are constantly in flux, as people interact with new individuals, current relationships evolve, and the organization itself changes over time. 2

The informal organization in Justin’s design will form as people begin interacting with one another to accomplish their work. As this occurs, people will begin connecting with one another as they make sense of their new roles and relationships. Usually, the informal organization closely mirrors the formal organization, but often it is different. People quickly learn who the key influencers are within the system, and they will begin to rely on these individuals to accomplish the work of the organization. The informal organization can either help or hinder an organization’s overall success.

In sum, the formal organization explains how an organization should function, while the informal organization is how the organizational actually functions. Formal organization will come as Justin hires and assigns people to different roles. They can influence the shape of the informal organization by giving people opportunities to build relationships as they work together. Both types of structures shape the patterns of influence, administration, and leadership that may occur through an organizational system.

As we continue our discussion of structure and design, we will next examine different ways of understanding formal structure.

Types of Formal Organizational Structures

Now, Justin will need to choose and implement an administrative system for delegating duties, establishing oversight, and reporting on performance. They will do this by designing a formal structure that defines the responsibilities and accountability that correspond to specific duties throughout an organizational system. In this section, we’ll discuss the factors that any manager should consider when designing an organizational structure.

Bureaucracy

One of the most common frameworks for thinking about these issues is called the bureaucratic model . It was developed by Max Weber, a 19th-century sociologist. Weber’s central assumption was that organizations will find efficiencies when they divide the duties of labor, allow people to specialize, and create structure for coordinating their differentiated efforts, usually within a hierarchy of responsibility. He proposed five elements of bureaucracy that serve as a foundation for determining an appropriate structure: specialization, command-and-control, span of control, centralization, and formalization. 3

Specialization

The degree to which people are organized into subunits according to their expertise is referred to as specialization —for example, human resources, finance, marketing, or manufacturing. It may also include specialization within those functions. For instance, people who work in a manufacturing facility may be well-versed in every part of a manufacturing process, or they may be organized into specialty units that focus on different parts of the manufacturing process, such as procurement, material preparation, assembly, quality control, and the like.

Command-and-Control

The next element to consider is the reporting and oversight structure of the organization. Command-and-control refers to the way in which people report to one another or connect to coordinate their efforts in accomplishing the work of the organization.

Span of Control

Another question addresses the scope of the work that any one person in the organization will be accountable for, referred to as span of control . For instance, top-level leaders are usually responsible for all of the work of their subordinates, mid-level leaders are responsible for a narrower set of responsibilities, and ground-level employees usually perform very specific tasks. Each manager in a hierarchy works within the span of control of another manager at a level of the organization.

Centralization

The next element to consider is how to manage the flows of resources and information in an organization, or its centralization . A highly centralized organization concentrates resources in only one or very few locations, or only a few individuals are authorized to make decisions about the use of resources. In contrast, a diffuse organization distributes resources more broadly throughout an organizational system along with the authority to make decisions about how to use those resources.

Formalization

The last element of bureaucracy, formalization , refers to the degree of definition in the roles that exist throughout an organization. A highly formalized system (e.g., the military) has a very defined organization, a tightly structured system, in which all of the jobs, responsibilities, and accountability structures are very clearly understood. In contrast, a loosely structured system (e.g., a small, volunteer nonprofit) relies heavily on the emergent relationships of informal organization.

Mechanistic and Organic Structures

Using the principles of bureaucracy outlined above, managers like Justin have experimented with many different structures as way to shape the formal organization and potentially to capture some of the advantages of the informal organization. Generally, the application of these principles leads to some combination of the two kinds of structures that can be seen as anchors on a continuum (see Table 10.1 ).

On one end of the continuum is mechanistic bureaucratic structure . This is a strongly hierarchical form of organizing that is designed to generate a high degree of standardization and control. Mechanistic organizations are often characterized by a highly vertical organizational structure , or a “tall” structure, due to the presence of many levels of management. A mechanistic structure tends to dictate roles and procedure through strong routines and standard operating practices.

In contrast, an organic bureaucratic structure relies on the ability of people to self-organize and make decisions without much direction such that they can adapt quickly to changing circumstances. In an organic organization, it is common to see a horizontal organizational structure , in which many individuals across the whole system are empowered to make organizational decision. An organization with a horizontal structure is also known as a flat organization because it often features only a few levels of organizational hierarchy.

The principles of bureaucracy outlined earlier can be applied in different ways, depending on the context of the organization and the managers’ objectives, to create structures that have features of either mechanistic or organic structures.

For example, the degree of specialization required in an organization depends both on the complexity of the activities the organization needs to account for and on the scale of the organization. A more organic organization may encourage employees to be both specialists and generalists so that they are more aware of opportunities for innovation within a system. A mechanistic organization may emphasize a strong degree of specialization so that essential procedures or practices are carried out with consistency and predictable precision. Thus, an organization’s overall objectives drive how specialization should be viewed. For example, an organization that produces innovation needs to be more organic, while an organization that seeks reliability needs to be more mechanistic.

Similarly, the need for a strong environment of command-and-control varies by the circumstances of each organization. An organization that has a strong command-and-control system usually requires a vertical, tall organizational administrative structure. Organizations that exist in loosely defined or ambiguous environments need to distribute decision-making authority to employees, and thus will often feature a flat organizational structure.

The span of control assigned to any specific manager is commonly used to encourage either mechanistic or organic bureaucracy. Any manager’s ability to attend to responsibilities has limits; indeed, the amount of work anyone can accomplish is finite. A manager in an organic structure usually has a broad span of control, forcing her to rely more on subordinates to make decisions. A manager in a mechanistic structure usually has a narrow span of control so that they can provide more oversight. Thus, increasing span of control for a manager tends to flatten the hierarchy while narrowing span of control tends to reinforce the hierarchy.

Centralization addresses assumptions about how an organization can best achieve efficiencies in its operations. In a mechanistic structure, it is assumed that efficiencies will occur in the system if the resources and decisions flow through in a centralized way. In an organic system, it is assumed that greater efficiencies will be seen by distributing those resources and having the resources sorted by the users of the resources. Either perspective may work, depending on the circumstances.

Finally, managers also have discretion in how tightly they choose to define the formal roles and responsibilities of individuals within an organization. Managers who want to encourage organic bureaucracy will resist the idea of writing out and tightly defining roles and responsibilities. They will encourage and empower employees to self-organize and define for themselves the roles they wish to fill. In contrast, managers who wish to encourage more mechanistic bureaucracy will use tools such as standard operating procedures (SOPs) or written policies to set expectations and exercise clear controls around those expectations for employees.

When a bureaucratic structure works well, an organization achieves an appropriate balance across all of these considerations. Employees specialize in and become highly advanced in their ability to perform specific functions while also attending to broader organizational needs. They receive sufficient guidance from managers to stay aligned with overall organizational goals. The span of control given to any one manager encourages them to provide appropriate oversight while also relying on employees to do their part. The resources and decision-making necessary to accomplish the goals of the organization are efficiently managed. There is an appropriate balance between compliance with formal policy and innovative action.

Business Structures

Aside from the considerations outlined above, organizations will often set structures according to the functional needs of the organization. A functional need refers to a feature of the organization or its environment that is necessary for organizational success. A business structure is designed to address these organizational needs. There are two common examples of functional structures illustrated here.

Product structures exist where the business organizes its employees according to product lines or lines of business. For example, employees in a car company might be organized according to the model of the vehicle that they help to support or produce. Employees in a consulting firm might be organized around a particular kind of practice that they work in or support. Where a functional structure exists, employees become highly attuned to their own line of business or their own product.

Geographic structures exist where organizations are set up to deliver a range of products within a geographic area or region. Here, the business is set up based on a territory or region. Managers of a particular unit oversee all of the operations of the business for that geographical area.

In either functional structure, the manager will oversee all the activities that correspond to that function: marketing, manufacturing, delivery, client support systems, and so forth. In some ways, a functional structure is like a smaller version of the larger organization—a smaller version of the bureaucracy that exists within the larger organization.

One common weakness of a bureaucratic structure is that people can become so focused on their own part of the organization that they fail to understand or connect with broader organizational activities. In the extreme, bureaucracy separates and alienates workers from one another. These problems can occur when different parts of an organization fail to communicate effectively with one another.

Some organizations set up a matrix structure to minimize the potential for these problems. A matrix structure describes an organization that has multiple reporting lines of authority. For example, an employee who specializes in a particular product might have both the functional reporting line and a geographic reporting line. This employee has accountability in both directions. The functional responsibility has to do with her specialty as it correlates with the strategy of the company as a whole. However, her geographic accountability is to the manager who is responsible for the region or part of the organization in which she is currently working. The challenge is that an employee may be accountable to two or more managers, and this can create conflict if those managers are not aligned. The potential benefit, however, is that employees may be more inclined to pay attention to the needs of multiple parts of the business simultaneously.

Concept Check

- What is an organizational structure?

- What are different types of organizational structures?

- What is organizational design?

- What concepts should guide decisions about how to design structures?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: David S. Bright, Anastasia H. Cortes

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Management

- Publication date: Mar 20, 2019

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/10-1-organizational-structures-and-design

© Jan 9, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

What is Organizational Structure? Definition, Types, Hierarchy, and Examples

By Nick Jain

Published on: April 12, 2024

What is Organizational Structure?

Organizational structure is defined as the framework of roles, responsibilities, authority relationships, and communication channels within an organization. It defines how tasks are divided, coordinated, and controlled to achieve the organization’s objectives effectively. Organizational structure establishes the hierarchy of decision-making, clarifies reporting relationships, and outlines the flow of authority and communication throughout the organization.

Key components of organizational structure include:

- Hierarchy: Organizational structure typically includes levels of hierarchy, from top management to lower-level employees. This hierarchy establishes reporting relationships and defines the chain of command within the organization.

- Departments and Units: Organizations are often divided into functional departments or units based on specialized functions or areas of expertise, such as finance, marketing, operations, and human resources.

- Roles and Responsibilities: Each position within the organization has defined roles, responsibilities, and authority levels. This clarity helps employees understand their duties and expectations within the organization.

- Centralization vs. Decentralization: Organizational structure may vary in terms of centralization or decentralization of decision-making authority. In centralized structures, decision-making authority is concentrated at the top of the hierarchy, while decentralized structures delegate decision-making to lower levels of the organization.

- Span of Control: The concept of span of control pertains to the number of subordinates or employees that a manager directly oversees. A wide span of control indicates fewer levels of hierarchy and more autonomy for employees, while a narrow span of control involves more layers of management and closer supervision.

- Formalization: Formalization refers to the degree of standardization and codification of rules, procedures, and processes within the organization. Highly formalized structures have strict rules and procedures, while less formalized structures allow for more flexibility and discretion.

- Functional Structure: Organized around specialized functions or departments, such as marketing, finance, and operations.

- Divisional Structure: Organized by product lines, geographic regions, or customer segments.

- Matrix Structure: Combines functional and divisional structures, creating dual lines of authority and reporting relationships.

- Flat Structure: Few levels of hierarchy with a wide span of control, promoting autonomy and collaboration among employees.

- Hierarchical Structure: Traditional pyramid-shaped structure with multiple levels of management and clear reporting relationships.

Overall, organizational structure plays a critical role in shaping how work is organized, coordinated, and managed within an organization. It provides a framework for allocating resources, making decisions, and achieving strategic objectives effectively.

Types of Organizational Structure

There are several types of organizational structures, each with its own advantages, disadvantages, and suitability for different types of organizations and industries. Here are some common types:

Functional Structure:

- Organizes employees into functional departments based on specialized functions, such as marketing, finance, operations, and human resources.

- Advantages: Efficient use of expertise, clear career paths, and economies of scale within each function.

- Disadvantages: Communication barriers between departments, lack of focus on overall organizational goals, and potential for a silo mentality.

Divisional Structure:

- Divide the organization into semi-autonomous divisions or units based on products, geographic regions, customer segments, or markets.

- Each division operates as a separate entity with its own functional departments (e.g., marketing, finance) to support its specific needs.

- Advantages: Allows for focus on specific markets or products, facilitates adaptation to local conditions, and promotes innovation and responsiveness.

- Disadvantages: Duplication of resources and functions across divisions, potential for competition and conflict between divisions, and coordination challenges.

Matrix Structure:

- Combines elements of both functional and divisional structures, creating a dual reporting system where employees report to both functional managers and project or product managers.

- Matrix structures are often used in project-based organizations or industries requiring cross-functional collaboration.

- Advantages: Flexibility to allocate resources based on project needs, enhanced coordination and communication between functions, and efficient use of specialized expertise.

- Disadvantages: Complexity in reporting relationships, potential for power struggles and conflicts, and increased administrative overhead.

Flat Structure:

- Has few levels of hierarchy and a wide span of control, with decentralized decision-making and greater autonomy for employees.

- Flat structures promote collaboration, innovation, and quick decision-making, as there are fewer layers of management.

- Advantages: Faster communication, empowered employees, and reduced bureaucracy.

- Disadvantages: Potential for lack of clear direction or oversight, difficulty in maintaining consistency across functions, and limited career advancement opportunities.

Hierarchical Structure:

- Traditional pyramid-shaped structure with multiple levels of management and clear reporting relationships.

- Each employee reports to a single supervisor, and decision-making authority flows from top management down through the organization.

- Advantages: Clear lines of authority and responsibility, well-defined career paths, and centralized decision-making.

- Disadvantages: Slow communication and decision-making processes, potential for bureaucratic red tape, and limited flexibility to respond to changes in the external environment.

Network Structure:

- Relies on external partnerships, alliances, and outsourcing arrangements to perform key functions or deliver products and services.

- The organization acts as a network of interconnected entities, leveraging external expertise and resources to achieve its objectives.

- Advantages: Access to specialized expertise and resources, flexibility to scale operations up or down, and cost savings through outsourcing.

- Disadvantages: Dependency on external partners, coordination challenges, and potential loss of control over key processes.

These are just a few examples of organizational structures, and organizations often use a combination of structures or adapt their structure over time to meet changing needs and objectives. The choice of organizational structure depends on factors such as the organization’s size, industry, strategy, culture, and external environment.

Hierarchical Organizational Structure

A hierarchical organizational structure is a traditional pyramid-shaped arrangement of authority and responsibility within an organization. In this structure, employees are organized into layers or levels of hierarchy, with each level having a designated level of authority and reporting relationships.

Key features of a hierarchical organizational structure include:

- Clear Chain of Command: Authority flows from top management down through the organization in a clear and well-defined chain of command. Every employee is accountable to a direct supervisor, to whom they submit reports.

- Multiple Levels of Management: The structure consists of multiple levels of management, typically including top-level executives (such as CEOs or presidents), middle managers, and frontline supervisors.

- Specialization of Functions: Different functions or departments within the organization are typically organized into separate levels of the hierarchy, such as finance, marketing, operations, and human resources.

- Centralized Decision-Making: Decision-making authority is concentrated at the top of the hierarchy, with top-level executives making strategic decisions that guide the organization’s direction and objectives.

- Standardized Procedures: Hierarchical organizations often rely on standardized procedures, rules, and policies to maintain consistency and control over operations.

- Vertical Communication: Communication flows primarily up and down the hierarchy, with information and directives passed down from top management to lower levels, and feedback and reports moving upward.

Advantages of a hierarchical organizational structure include:

- Clarity of Roles and Responsibilities: Clear reporting relationships and lines of authority help employees understand their roles and responsibilities within the organization.

- Efficient Decision-Making: Centralized decision-making can lead to quicker decisions, particularly on strategic matters, as top management has the authority to make decisions without needing to consult lower levels of the hierarchy.

- Clear Career Paths: Hierarchical structures often offer clear career advancement paths, with opportunities for promotion as employees move up through the ranks.

Disadvantages of a hierarchical organizational structure include:

- Bureaucracy: Hierarchical structures can be bureaucratic and slow-moving, with decisions and information needing to pass through multiple levels of management before action is taken.

- Limited Flexibility: The rigid nature of hierarchical structures may limit an organization’s ability to adapt quickly to changes in the external environment or respond to customer needs.

- Communication Barriers: Communication may be hindered by the strict hierarchy, with information getting filtered or distorted as it moves up and down the chain of command.

- Potential for Micromanagement: Middle managers may engage in micromanagement as they oversee the work of their subordinates, leading to decreased employee autonomy and motivation.

Despite these disadvantages, hierarchical organizational structures remain common in many organizations, particularly large corporations and government agencies, due to their stability, clarity, and familiarity. However, some organizations may adopt flatter or more decentralized structures to overcome the limitations of hierarchy and promote agility and innovation.

Organizational Structure Example

Here’s an example of a hierarchical organizational structure for a fictional company:

Company Name: XYZ Corporation

1. Top-Level Management:

- CEO (Chief Executive Officer): Responsible for overall strategic direction and leadership of the company. Directly oversees other top executives and reports to the board of directors.

- CFO (Chief Financial Officer): Responsible for financial planning, reporting, and management. Oversees accounting, budgeting, and financial analysis.

- COO (Chief Operating Officer): Responsible for day-to-day operations of the company. Oversees production, logistics, and supply chain management.

2. Middle Management:

- Vice President of Sales and Marketing: Oversees sales, marketing, and customer relations. Manages sales teams, advertising campaigns, and market research.

- Vice President of Operations: Oversees manufacturing, production, and logistics. Manages production schedules, quality control, and inventory management.

- Vice President of Human Resources: Responsible for recruiting, training, and managing personnel. Manages employee relations, performance evaluations, and HR policies.

3. Lower-Level Management:

- Sales Manager (North Region): Manages sales representatives in the northern region. Sets sales targets, monitors performance, and provides training and support.

- Production Manager: Oversees manufacturing operations and production staff. Ensures production schedules are met, monitors quality standards, and implements process improvements.

- Marketing Manager: Leads marketing campaigns and promotional activities. Coordinates with advertising agencies, analyzes market trends, and develops marketing strategies.

4. Non-Managerial Employees:

- Sales Representatives: Responsible for selling company products or services to customers. Develops leads, negotiates contracts, and maintains customer relationships.

- Production Supervisors: Supervises production line workers and ensures adherence to safety and quality standards. Coordinates with production manager to optimize workflow.

- Marketing Assistants: Assists marketing manager in executing marketing campaigns. Prepares promotional materials, manages social media accounts, and analyzes campaign performance.

This hierarchical organizational structure illustrates the division of roles, responsibilities, and reporting relationships within the company. Each level of management has its own set of duties and authority, with clear lines of communication and supervision. While this structure provides stability and clarity, it may also face challenges such as bureaucracy and communication barriers.

Igniting Innovation

Powerful innovation starts as an idea. Launch your IdeaScale community today

Ignite Innovation With Your IdeaScale Community!

IdeaScale is an innovation management solution that inspires people to take action on their ideas. Your community’s ideas can change lives, your business and the world. Connect to the ideas that matter and start co-creating the future.

Copyright © 2024 IdeaScale

Privacy Overview

- Book a Speaker

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Vivamus convallis sem tellus, vitae egestas felis vestibule ut.

Error message details.

Reuse Permissions

Request permission to republish or redistribute SHRM content and materials.

Understanding Organizational Structures

Organizational structure aligns and relates parts of an organization, so it can achieve its maximum performance. The structure chosen affects an organization's success in carrying out its strategy and objectives. Leadership should understand the characteristics, benefits and limitations of various organizational structures to assist in this strategic alignment.

Overview Background Business Case Key Elements of Organizational Structures Types of Organizational Structures

Vertical structures (functional and divisional)

Matrix organizational structures, open boundary structures (hollow, modular virtual and learning).

The Impact of Growth Stages on Organizational Structure Metrics Communications and Technology Global Issues Legal Issues

This article addresses the following topics related to organizational structure:

- The case for aligning organizational structure with the enterprise's business strategy.

- Key elements of organizational structure.

- Types of organizational structures and the possible benefits and limitations of each.

- The impact of an organization's stage of development on its structure.

- Communications, technology, metrics, global and legal issues.

Organizational structure is the method by which work flows through an organization. It allows groups to work together within their individual functions to manage tasks. Traditional organizational structures tend to be more formalized—with employees grouped by function (such as finance or operations), region or product line. Less traditional structures are more loosely woven and flexible, with the ability to respond quickly to changing business environments.

Organizational structures have evolved since the 1800s. In the Industrial Revolution, individuals were organized to add parts to the manufacture of the product moving down the assembly line. Frederick Taylor's scientific management theory optimized the way tasks were performed, so workers performed only one task in the most efficient way. In the 20th century, General Motors pioneered a revolutionary organizational design in which each major division made its own cars.

Today, organizational structures are changing swiftly—from virtual organizations to other flexible structures. As companies continue to evolve and increase their global presence, future organizations may embody a fluid, free-forming organization, member ownership and an entrepreneurial approach among all members. See Inside Day 1: How Amazon Uses Agile Team Structures and Adaptive Practices to Innovate on Behalf of Customers .

Business Case

A hallmark of a well-aligned organization is its ability to adapt and realign as needed. To ensure long-term viability, an organization must adjust its structure to fit new economic realities without diminishing core capabilities and competitive differentiation. Organizational realignment involves closing the structural gaps impeding organizational performance.

Problems created by a misaligned organizational structure

Rapid reorganization of business units, divisions or functions can lead to ineffective, misaligned organizational structures that do not support the business. Poorly conceived reorganizations may create significant problems, including the following:

- Structural gaps in roles, work processes, accountabilities and critical information flows can occur when companies eliminate middle management levels without eliminating the work, forcing employees to take on additional responsibilities.

- Diminished capacity, capability and agility issues can arise when a) lower-level employees who step in when middle management is eliminated are ill-equipped to perform the required duties and b) when higher-level executives must take on more tactical responsibilities, minimizing the value of their leadership skills.

- Disorganization and improper staffing can affect a company's cost structure, cash flow and ability to deliver goods or services. Agile organizations can rapidly deploy people to address shifting business needs. With resources cut to the bone, however, most organizations' staff members can focus only on their immediate responsibilities, leaving little time, energy or desire to work outside their current job scope. Ultimately, diminished capacity and lagging response times affect an organization's ability to remain competitive.

- Declining workforce engagement can reduce retention, decrease customer loyalty and limit organizational performance and stakeholder value.

The importance of aligning the structure with the business strategy

The key to profitable performance is the extent to which four business elements are aligned:

Leadership. The individuals responsible for developing and deploying the strategy and monitoring results.

Organization. The structure, processes and operations by which the strategy is deployed.

Jobs. The necessary roles and responsibilities.

People. The experience, skills and competencies needed to execute the strategy.

An understanding of the interdependencies of these business elements and the need for them to adapt to change quickly and strategically are essential for success in the high-performance organization. When these four elements are in sync, outstanding performance is more likely.

Achieving alignment and sustaining organizational capacity requires time and critical thinking. Organizations must identify outcomes the new structure or process is intended to produce. This typically requires recalibrating the following:

- Which work is mission-critical, can be scaled back or should be eliminated.

- Existing role requirements, while identifying necessary new or modified roles.

- Key metrics and accountabilities.

- Critical information flows.

- Decision-making authority by organization level.

See Meeting the Challenges of Developing Collaborative Teams for Future Success.

Key Elements of Organizational Structures

Five elements create an organizational structure: job design, departmentation, delegation, span of control and chain of command. These elements comprise an organizational chart and create the organizational structure itself. "Departmentation" refers to the way an organization structures its jobs to coordinate work. "Span of control" means the number of individuals who report to a manager. "Chain of command" refers to a line of authority.

The company's strategy of managerial centralization or decentralization also influences organizational structures. "Centralization," the degree to which decision-making authority is restricted to higher levels of management, typically leads to a pyramid structure. Centralization is generally recommended when conflicting goals and strategies among operating units create a need for a uniform policy. "Decentralization," the degree to which lower levels of the hierarchy have decision-making authority, typically leads to a leaner, flatter organization. Decentralization is recommended when conflicting strategies, uncertainty or complexity require local adaptability and decision-making.

Types of Organizational Structures

Organizational structures have evolved from rigid, vertically integrated, hierarchical, autocratic structures to relatively boundary-less, empowered, networked organizations designed to respond quickly to customer needs with customized products and services.

Today, organizations are usually structured vertically, vertically and horizontally, or with open boundaries. Specific types of structures within each of these categories are the following:

- Vertical — functional and divisional.

- Vertical and horizontal — matrix.

- Boundary-less (also referred to as "open boundary")—modular, virtual and cellular.

See What are commonly-used organization structures?

Two main types of vertical structure exist, functional and divisional. The functional structure divides work and employees by specialization. It is a hierarchical, usually vertically integrated, structure. It emphasizes standardization in organization and processes for specialized employees in relatively narrow jobs.

This traditional type of organization forms departments such as production, sales, research and development, accounting, HR, and marketing. Each department has a separate function and specializes in that area. For example, all HR professionals are part of the same function and report to a senior leader of HR. The same reporting process would be true for other functions, such as finance or operations.

In functional structures, employees report directly to managers within their functional areas who in turn report to a chief officer of the organization. Management from above must centrally coordinate the specialized departments.

A functional organizational chart might look something like this:

Advantages of a functional structure include the following:

- The organization develops experts in its respective areas.

- Individuals perform only tasks in which they are most proficient.

- This form is logical and easy to understand.

Disadvantages center on coordination or lack thereof:

- People are in specialized "silos" and often fail to coordinate or communicate with other departments.

- Cross-functional activity is more difficult to promote.

- The structure tends to be resistant to change.

This structure works best for organizations that remain centralized (i.e., a majority of the decision-making occurs at higher levels of the organization) because there are few shared concerns or objectives between functional areas (e.g., marketing, production, purchasing, IT). Given the centralized decision-making, the organization can take advantage of economies of scale in that there are likely centralized purchasing functions.

An appropriate management system to coordinate the departments is essential. The management system may be a special leader, like a vice president, a computer system or some other format.

Also a vertical arrangement, a divisional structure most often divides work and employees by output, although a divisional structure could be divided by another variable such as market or region. For example, a business that sells men's, women's and children's clothing through retail, e-commerce and catalog sales in the Northeast, Southeast and Southwest could be using a divisional structure in one of three ways:

- Product—men's wear, women's wear and children's clothing.

- Market—retail store, e-commerce and catalog.

- Region—Northeast, Southeast and Southwest.

A divisional organizational structure might look like this:

The advantages of this type of structure are the following:

- It provides more focus and flexibility on each division's core competency.

- It allows the divisions to focus on producing specialized products while also using knowledge gained from related divisions.

- It allows for more coordination than the functional structure.

- Decision-making authority pushed to lower levels of the organization enables faster, customized decisions.

The disadvantages of this structure include the following:

- It can result in a loss of efficiency and a duplication of effort because each division needs to acquire the same resources.

- Each division often has its own research and development, marketing, and other units that could otherwise be helping each other.

- Employees with similar technical career paths have less interaction.

- Divisions may be competing for the same customers.

- Each division often buys similar supplies in smaller quantities and may pay more per item.

This type of structure is helpful when the product base expands in quantity or complexity. But when competition among divisions becomes significant, the organization is not adapting quickly enough, or when economies of scale are lacking, the organization may require a more sophisticated matrix structure.

A matrix structure combines the functional and divisional structures to create a dual-command situation. In a matrix structure, an employee reports to two managers who are jointly responsible for the employee's performance. Typically, one manager works in an administrative function, such as finance, HR, information technology, sales or marketing, and the other works in a business unit related to a product, service, customer or geography.

A typical matrix organizational structure might look like this:

Advantages of the matrix structure include the following:

- It creates a functional and divisional partnership and focuses on the work more than on the people.

- It minimizes costs by sharing key people.

- It creates a better balance between time of completion and cost.

- It provides a better overview of a product that is manufactured in several areas or sold by various subsidiaries in different markets.

Disadvantages of matrix organizations include the following:

- Responsibilities may be unclear, thus complicating governance and control.

- Reporting to more than one manager at a time can be confusing for the employee and supervisors.

- The dual chain of command requires cooperation between two direct supervisors to determine an employee's work priorities, work assignments and performance standards.

- When the function leader and the product leader make conflicting demands on the employee, the employee's stress level increases, and performance may decrease.

- Employees spend more time in meetings and coordinating with other employees.

These disadvantages can be exacerbated if the matrix goes beyond two-dimensional (e.g., employees report to two managers) to multidimensional (e.g., employees report to three or more managers).