The Current Education Issues in the Philippines — and How Childhope Rises to the Challenge

- August 25, 2021

Even before COVID-19 struck and caused problems for millions of families, the country’s financial status is one of the top factors that add to the growing education issues in the Philippines. Furthermore, more children, youth, and adults can’t get a leg up and are thus left behind due to unfair access to learning.

Moving forward, such issues can lead to worse long-term effects. Now, we’ll delve deep into the current status and how we can take part in social efforts to help fight these key concerns of our country.

Crisis in Philippine Education: How is It Really?

Filipinos from rich households or living in cities and developed towns have more access to private schools. In contrast, less favored groups are more bound to deal with lack of classrooms, teachers, and means to sustain topnotch learning.

A 2018 study found that a sample number of 15-year-old Filipino students ranked last in reading comprehension out of 79 countries . They also ranked 78 th in science and math. One key insight from this study is it implies those tested mostly came from public schools. Hence, the crisis also lies in the fact that a lot of Filipinos can’t read or do simple math.

Indeed, it’s clear that there is a class divide between rich and poor students in the country. Though this is the case, less developed states can focus on learning if it’s covered in their top concerns. However, the Philippines doesn’t invest on topnotch learning as compared to its neighbor countries. In fact, many public schools lack computers and other tools despite the digital age. Further, a shortfall in the number of public school teachers is also one of the top issues in the country due to their being among the lowest-paid state workers. Aside from that, more than 3 million children, youth, and adults remain unenrolled since the school shutdown.

It goes without saying that having this constant crisis has its long-term effects. These include mis- and disinformation, poor decision-making, and other social concerns.

The Education System in the Philippines

Due to COVID-19, education issues in the Philippines have increased and received new challenges that worsened the current state of the country. With the sudden events brought about by the health crisis, distance learning modes via the internet or TV broadcasts were ordered. Further, a blended learning program was launched in October 2020, which involves online classes, printouts, and lessons broadcast on TV and social platforms. Thus, the new learning pathways rely on students and teachers having access to the internet.

This yet brings another issue in the current system. Millions of Filipinos don’t have access to computers and other digital tools at home to make their blended learning worthwhile. Hence, the value of tech in learning affects many students. Parents’ and guardians’ top concerns with this are:

- Money for mobile load

- Lack of gadget

- Poor internet signal

- Students’ struggle to focus and learn online

- Parents’ lack of knowledge of their kids’ lessons

It’s key to note that equipped schools have more chances to use various ways to deal with the new concerns for remote learning. This further shows the contrasts in resources and training for both K-12 and tertiary level both for private and public schools.

One more thing that can happen is that schools may not be able to impart the most basic skills needed. To add, the current status can affect how tertiary education aims to impart the respect for and duty to knowledge and critical outlook. Before, teachers handled 40 to 60 students. With the current online setup, the quality of learning can be compromised if the class reaches 70 to 80 students.

Data on Students that Have Missed School due to COVID-19

Of the world’s student population, 89% or 1.52 billion are the children and youth out of school due to COVID-19 closures. In the Philippines, close to 4 million students were not able to enroll for this school year, as per the DepEd. With this, the number of out-of-school youth (OSY) continues to grow, making it a serious issue needing to be checked to avoid worse problems in the long run.

List of Issues When it Comes to the Philippines’ Education System

For a brief rundown, let’s list the top education issues in the Philippines:

- Quality – The results of the 2014 National Achievement Test (NAT) and the National Career Assessment Examination (NCAE) show that there had been a drop in the status of primary and secondary education.

- Budget – The country remains to have one of the lowest budget allotments to learning among ASEAN countries.

- Cost – There still is a big contrast in learning efforts across various social groups due to the issue of money—having education as a status symbol.

- OSY – The growing rate of OSY becomes daunting due to the adverse effects of COVID-19.

- Mismatch – There is a large sum of people who are jobless or underpaid due to a large mismatch between training and actual jobs.

- Social divide – There is no fair learning access in the country.

- Lack of resources – Large-scale shortfalls in classrooms, teachers, and other tools to sustain sound learning also make up a big issue.

All these add to the big picture of the current system’s growing concerns. Being informed with these is a great first step to know where we can come in and help in our own ways. Before we talk about how you can take part in various efforts to help address these issues, let’s first talk about what quality education is and how we can achieve it.

What Quality Education Means

Now, how do we really define this? For VVOB , it is one that provides all learners with what they need to become economically productive that help lead them to holistic development and sustainable lifestyles. Further, it leads to peaceful and democratic societies and strengthens one’s well-being.

VVOB also lists its 6 dimensions:

- Contextualization and Relevance

- Child-friendly Teaching and Learning

- Sustainability

- Balanced Approach

- Learning Outcomes

Aside from these, it’s also key to set our vision to reach such standards. Read on!

Vision for a Quality Education

Of course, any country would want to build and keep a standard vision for its learning system: one that promotes cultural diversity; is free from bias; offers a safe space and respect for human rights; and forms traits, skills, and talent among others.

With the country’s efforts to address the growing concerns, one key program that is set to come out is the free required education from TESDA with efforts to focus on honing skills, including technical and vocational ones. Also, OSY will be covered in the grants of the CHED.

Students must not take learning for granted. In times of crises and sudden changes, having access to education should be valued. Aside from the fact that it is a main human right, it also impacts the other human rights that we have. Besides, the UN says that when learning systems break, having a sustained state will be far from happening.

How Childhope KalyEskwela Program Deals with Changes

The country rolled out its efforts to help respond to new and sudden changes in learning due to the effects of COVID-19 measures. Here are some of the key ones we can note:

- Continuous learning – Since the future of a state lies on how good the learning system is, the country’s vision for the youth is to adopt new learning paths despite the ongoing threat of COVID-19.

- Action plans – These include boosting the use of special funds to help schools make modules, worksheets, and study guides approved by the DepEd. Also, LGUs and schools can acquire digital tools to help learners as needed.

Now, even with the global health crisis, Childhope Philippines remains true to its cause to help street children:

- Mobile learning – The program provides topnotch access to street children to new learning methods such as non-formal education .

- Access to tools – This is to give out sets of school supplies to help street kids attend and be ready for their remote learning.

- Online learning sessions – These are about Skills for Life, Life Skill Life Goal Planning, Gender Sensitivity, Teenage Pregnancy and Adolescent Reproductive Health.

You may also check out our other programs and projects to see how we help street children fulfill their right to education . You can be a part of these efforts! Read on to know how.

Shed a Light of Hope for Street Children to Reach Their Dreams

Building a system that empowers the youth means helping them reach their full potential. During these times, they need aid from those who can help uphold the rights of the less privileged. These include kids in the streets and their right to attain quality education.

You may hold the power to change lives, one child at a time. Donate or volunteer , and help us help street kids learn and reach their dreams and bring a sense of hope and change toward a bright future. You may also contact us for more details. We’d love to hear from you!

With our aim to reach more people who can help, we’re also in social media! Check out our Facebook page to see latest news on our projects in force.

Subscribe to our Mailing List

©1989-2024 All Rights Reserved.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

With Schools Closed, Covid-19 Deepens a Philippine Education Crisis

The country remains among the few that have not at least partially reopened, sparking worry in a place where many lack a computer or internet access.

By Jason Gutierrez and Dan Bilefsky

MANILA — As jubilant students across the globe trade in online learning for classrooms, millions of children in the Philippines are staying home for the second year in a row because of the pandemic, fanning concerns about a worsening education crisis in a country where access to the internet is uneven.

President Rodrigo Duterte has justified keeping elementary schools and high schools closed by arguing that students and their families need to be protected from the coronavirus. The Philippines has one of the lowest vaccination rates in Asia, with just 16 percent of its population fully inoculated, and Delta variant infections have surged in recent months.

That makes the Philippines, with its roughly 27 million students, one of only a handful of countries that has kept schools fully closed throughout the pandemic, joining Venezuela, according to UNICEF, the United Nations Agency for Children. Other countries that kept schools closed, like Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, have moved to reopen them.

“I cannot gamble on the health of the children,” Mr. Duterte said in June, rejecting recommendations by the health department to reopen schools.

The move — which has kept nearly 2,000 schools closed — has spawned a backlash among parents and students in a sprawling nation with endemic poverty. Many people, particularly in remote and rural areas, do not have access to a computer or the internet at home for online learning.

Iljon Roxas, a high school student stuck at home in Bacoor City, south of Manila, said the monotony of staring at a computer screen over the past year made it difficult to concentrate, and he yearned to return to a real classroom. The fun and joy of learning, he added, had evaporated.

“I miss a lot of things, like bonding with classmates during free time,” said Iljon, 16. “I also miss my teachers, believe it or not. Since last year we have been stuck in front of our screens — you listen, you tune out.”

The crisis in the Philippines comes as countries across the world, including the United States, have been grappling with one of the worst disruptions of public schooling in modern history. Governments have struggled to balance the imperative of health and safety with the public duty to educate children.

Some countries, like Britain, have taken an aggressive approach to keeping schools open, including from late spring into early summer, when the Delta variant surged. While many elementary school students and their teachers did not wear masks, the British government focused instead on other safety measures, such as rapid testing and widespread quarantining.

Where schools have been closed for a long time, such as the Philippines, education experts have expressed concerns that the pandemic has created a “lost generation” of students, buffeted by the limits of remote learning and by overstretched parents struggling to serve as surrogate physics and literature teachers.

Maritess Talic, 46, a mother of two, said she feared her children had barely learned anything during the past year. Ms. Talic, who works part time as a maid, said she and her husband, a construction worker, had scraped together about 5,000 pesos, or about $100, to buy a secondhand computer tablet to share with their children, ages 7 and 9.

But the family — which lives in Imus, a suburb south of Manila — does not have consistent internet access at home. They rely on prepaid internet cards that are constantly running out, sometimes in the middle of her children’s online classes, Ms. Talic said. She has also struggled to teach her children science and math with her limited schooling.

“It is very hard,” she said, adding that the children struggled to share one device. “We can’t even find enough money to pay our electricity bill sometimes, and now we have to also look for extra money to pay for internet cards.”

She said she understood the need to prioritize health ahead of keeping schools opened, but she feared for her children’s future. “The thing is, I don’t think they are learning at all,” she added. “The internet connection is just too slow sometimes.”

Even before the pandemic, the Philippines was facing an education crisis, with overcrowded classrooms, shoddy public school infrastructure and desperately low wages for teachers creating a teacher shortage.

A 2020 World Bank report said the country also suffered from a digital divide. In 2018, it said, about 57 percent of the Philippines’s roughly 23 million households did not have internet access. However, the government has since been working to narrow that gap. Manila City Mayor Francisco Domagoso , said in an interview that last year, City Hall had handed out 130,000 tablets for school children and some 11,000 laptops for teachers.

UNICEF said in an August study that the school closures were especially damaging for vulnerable children, already facing the challenges of poverty and inequality. It called for the phased reopening of schools in the country, starting in low-risk areas and with stringent safety protocols in place.

The school closures have had negative consequences for students, said Oyunsaikhan Dendevnorov , UNICEF’s representative in the Philippines. Students have fallen behind and reported mental distress. She also cited a heightened risk of drop outs, child labor and child marriage.

As remote classes resumed this week, Leonor Briones, the education secretary, sought to portray the electronic reopening as a success. She said that about 24 million children, from elementary school to high school, were enrolled in school. But she acknowledged that the enrollment figure included about two million fewer students than last year.

Regina Tolentino, deputy secretary general of the College Editors Guild of the Philippines, which represents college newspaper editors, said the government’s attempt to put a positive spin on the second year of shuttered schools was “delusional.”

With remote learning the only option, she said, poor students were being forced to spend money on computers and internet cards rather than on basic necessities like food. “The government must hear students out and uphold their basic rights to education even during the pandemic,” she said.

But leading doctors and health experts said that, while opening schools was an important aim, health and safety needed to be prioritized.

They pointed out that just over 14 million people in the Philippines were fully vaccinated, well below the government’s initial target of 70 million by the end of the year. Some hospitals were filled to capacity, and scenes of patients receiving oxygen in parking lots had become commonplace.

Dr. Anthony Leachon, a prominent public health expert who was a member of the government’s Covid-19 advisory panel, called for the vaccination of 12 to 17 year-olds to be fast-tracked to help clear the way for schools to be reopened.

“It’s dangerous,” he said, “to reopen schools with the Delta variant strains at the moment.”

Dan Bilefsky is a Canada correspondent for The New York Times, based in Montreal. He was previously based in London, Paris, Prague and New York. He is author of the book "The Last Job," about a gang of aging English thieves called "The Bad Grandpas." More about Dan Bilefsky

- Geopolitics

- Environment

Philippines needs to improve its education system

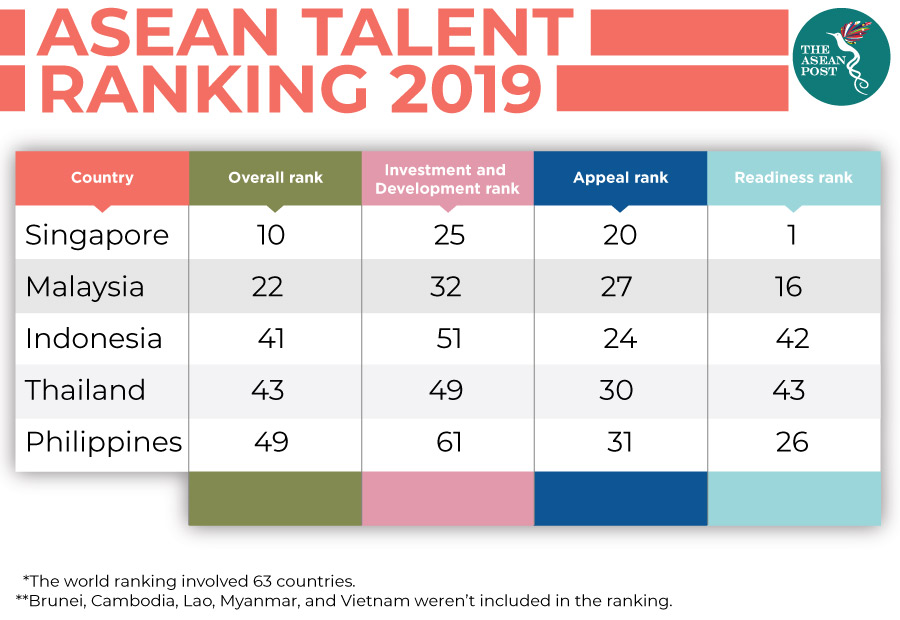

The research arm of Switzerland-based business school, the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) recently released the results of its survey on the talent competitiveness of 63 countries from around the world. Based on the rankings, the Philippines managed to jump up to 49th place from 55th last year.

Regardless of the jump, the ASEAN country, unfortunately, still performed the worst when compared to other bloc members. In order to understand how this happened, it’s important to look at what the study uses for its indicators.

The World Talent Ranking looks at three main factors when determining how to rank a country. The investment and development factor, which measures resources used to cultivate homegrown human capital; the appeal factor, which evaluates the extent to which a country attracts and retains foreign and local talent; and the readiness factor, which looks at the quality of skills and competencies of a country’s labour force.

While a simple example of the investment and development factor would be whether a country is able to provide education to its citizens, the readiness factor seems to indicate that it is also important to look at the quality of the education provided. This, according to the study, is where countries like the Philippines fall short.

Quality of education

For the three factors, the Philippines scored 31st for appeal, 61st for investment and development, and 26th for readiness. Similarly, last year, the Philippines scored lowest for investment and development.

In 2018, the IMD World Competitiveness Center’s director, Arturo Bris told the media that the Philippines’ labour force is not as equipped with skills that firms are looking for.

He acknowledged that it was true that the Philippines was making progress in managing its talent pool and is, in fact, one of only two countries in Southeast Asia along with Malaysia which has improved government investment in education as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

“However, in 2018, The Philippines witnessed a deterioration of its ability to provide the economy with the skills needed, which points to a mismatch between school curriculums and the demands of companies,” he said.

But it isn’t just a Swiss business school that thinks the Philippines needs to improve its quality of education. In June last year, local media reported the Philippine Business for Education (PBEd) as saying that while the state of education nationwide has progressed in terms of accessibility, it still has a long way to go when it comes to delivery of quality learning for the success of every learner.

PBEd executive director, Love Basillote said this can be attributed to many factors such as prevalence of malnutrition and a shortage of appropriate learning tools, adding that many college graduates are not work-ready due to a lack of socio-emotional skills.

“Our recommendation is we focus on learning by starting early, monitoring learning, raising accountability and aligning actors,” she said, also suggesting that the country participate consistently in international learning assessments to make Filipino learners and graduates globally competitive.

The World Talent Ranking 2018 cited the country’s top weaknesses in the areas of total public expenditure on education, pupil-teacher ratio in primary and secondary schools, and remuneration in service professions and labour force growth.

Upgrading digital skills

The World Economic Forum (WEF) head of Asia Pacific and Member of the Executive Committee, Justin Wood noted that Industry 4.0, also known as the Fourth Industrial Revolution, was unfolding at accelerating speed and changing the skills that workers will need for the jobs of the future.

On 19 November last year, a coalition of major technology companies pledged to develop digital skills for the ASEAN workforce. Being part of the WEF’s Digital ASEAN initiative, the pledge aims to train some 20 million people in Southeast Asia by 2020, especially those working in small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs).

The move is most welcomed especially due to the threat of huge job displacement across the region. Now, following results from the World Talent Ranking, it seems that this initiative would be much needed in the Philippines as well.

However, the Philippines must understand that the pledge will only go so far in ensuring that it has the right workforce for the new skills demands of companies. Improving the quality of education in the country is still critical and as 2019’s results highlight, the Philippines needs to continue working on this.

This article was first published on 5 December, 2019.

Related articles:

Critical thinking needed to upgrade skills

Time to invest in human capital

Tangshan And Xuzhou: China's Treatment Of Women

Myanmar's suu kyi: prisoner of generals, philippines ends china talks for scs exploration, ukraine war an ‘alarm for humanity’: china’s xi, china to tout its governance model at brics summit, wrist-worn trackers detect covid before symptoms.

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Reimagining Philippine education

Education is our passport to employment and a stable future. Ask any parent about their dream for their child and it will always be: to finish school, earn a diploma, land a job, and lead a good life. A priceless inheritance that no one can take away. However, with many students graduating and lacking the competencies needed for employment, we need to ask ourselves—are we doing enough to prepare learners for the future? Are we equipping them with enough skills to thrive in the workplaces of today and tomorrow?

The passage of the K-to-12 law promised quality education and life-ready graduates, but 10 years into its implementation, challenges remain, keeping us from realizing what was promised.

Many of our senior high school students are not able to find jobs upon graduation. Even those with college degrees face similar challenges, with many of them having to take additional programs to upskill in order to find a job. Worse, students in their early years are not even learning properly.

One in every three Filipino children under the age of 5 are malnourished and stunted, affecting their capacity to learn. So by the age of 10, it is no longer a surprise that 90 percent of our learners cannot even read a simple text.

We also have a long way to go to capacitate our teachers, both preservice and in service. A study by Philippine Business for Education (PBEd) revealed that since 2010, 56 percent of teacher education schools scored below average passing rates in the board licensure examination for professional teachers. And once they are in service, challenges continue to burden them, including administrative work that takes time away from teaching.

Our resources are not enough to support teaching and learning, as we still haven’t met the international recommendations for education budget allocation. We continue to play catch-up in education spending, and we have not yet fully harnessed the resources that the private sector can offer.

These challenges in the education system necessitates work that is coordinated, collaborative, intentional—and with the Filipino learner at the heart of it all. This is precisely why during PBEd’s Higher Education Summit last Feb. 16-17 in Mactan, Cebu, over 80 leaders from the government, industry, academe, and civil society worked together to discuss the most pressing issues in education and employability, and how we can all work together to address them. These hurdles in education governance, early childhood care and development, teaching quality, standards and assessment, as well public-private complementarity keep us from realizing the promise of quality education.

PBEd’s series of higher education summits also speak to the commitment of multiple stakeholders and the power of coordination. Since the first summit in 2013, we have seen various efforts to improve education quality over the years, including the rise in the government industry academe councils in many local governments, as well as stronger involvement of industry associations and sector skills councils in skills development—such as review of curriculum, development of training programs, and work-based training. Collective work of multiple sectors allows for efforts and resources to be aligned, and initiatives to be implemented at scale.

And with the recent convening of the Second Congressional Commission on Education (EdCom II), we have a once in a lifetime opportunity to reform education. We should seize this moment to act on our promise of providing a comprehensive and responsive education system. We need strong voices to reverberate as we call for policy reforms to address the learning crisis together.

By we, I mean all of us in the community—students, teachers, both public and private sector, and civil society groups. We are the “citizen’s EdCom.”

We need to reimagine a better education for our children, more than just acquiring a diploma. We need to work toward an education system where learners are nourished and supported in the best ways possible, so they can succeed. It takes a whole-of-society approach to empower our youth to achieve their full potential and lead better lives. This is the best gift that we can give our children that no one can take away.

——————

Justine B. Raagas is executive director of Philippine Business for Education. For questions or comments, email [email protected] .

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Business Matters is a project of the Makati Business Club ( [email protected] ).

Fearless views on the news

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

- High contrast

- OUR REPRESENTATIVE

- WORK FOR UNICEF

- NATIONAL AMBASSADORS

- PRESS CENTRE

Search UNICEF

For every child in bangsamoro, an education, over 45,000 children in the bangsamoro region don't have access to a school.

SOUTH UPI, Maguindanao, Philippines —Lizabel starts her day in pre-dawn hours. With a homemade lamp in hand, she makes her way through the darkness to a spring 500 meters away to take a bath. Her village, to this day, does not have electricity.

The 11-year-old meets up with her cousins and neighbors by the spring to wash up and get ready for another grueling day. The girls would then drop by their grandmother’s to help prepare breakfast and the meal they would bring to school.

On a typical day, breakfast is either boiled cassava or banana which they eat on their way to school. Lunch is ground corn, a cheap alternative to white rice that their families cannot afford. On better days, the children get a small dried fish each on top of the vegetables and ground corn.

A long walk from home

By 5 AM, Lizabel and her friends begin the three-hour trek to the village center, arriving just in time for school, sometimes even late. Braving the semi-dark hours through cornfields and rivers has been Lizabel’s routine for going to school for the past six years. The children flock together during the walk to avoid any danger on the way.

Lizabel belongs to the indigenous Teduray, a tribe of upland farmers, in South Upi, Maguindanao, in Southern Philippines. Her family lives in the outskirts of the village, three hours from the town center. In the absence of public transportation, walking is the only way for Lizabel and her friends in the area to get to school.

“It is difficult. I arrive at school already tired from walking and hungry too. I sometimes sleep in class. I cannot help it,” Lizabel admits. Despite the early start, she often arrives late for class.

“We teachers know Lizabel as the girl with a beautiful handwriting,” says Jocelyn Palao, a teacher from the same tribe. “She has potential, but she doesn’t participate during class activities and sometimes struggles to focus on lessons. But I can’t blame her because she walks a long way from home,” she adds.

Lizabel’s story represents the plight of children whose access to school is very limited or difficult. There are at least 213 barangays in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) where children do not have access to any learning facility. This problem is affecting over 45,000 primary school aged children.

Her hometown South Upi is located in BARMM, the most disadvantaged region in the Philippines in terms of socio-economic indicators. School enrolment and completion rates are much lower in BARMM compared to the national average in the Philippines.

About 48.5 percent of indigenous children in BARMM attend elementary school but only 11.2 percent complete basic education. A combination of armed conflict, exclusion and marginalization, and many families valuing immediate livelihood needs over the education of their children, have contributed in lagging education.

Similar issues are faced by Lizabel’s 13-year-old cousin Jinalyn studying in seventh grade. Jinalyn’s teacher in South Upi National High School, Mr. Hermane Eslabon Jr., explained that 40% of students live far away from the school. In addition to acute poverty and the exhausting daily walks to schools, the children are also expected to help parents in the fields in the harvesting seasons. They cannot cope with school work, perform poorly and most drop out from school.

Sheer determination

In school, Lizabel looks up to Jocelyn, her patient and supportive teacher who encourages her. “I feel like a second parent, and that it is my duty to educate children of my tribe. I understand their hardship. Their parents are occupied in the fields all day to make a living. They are not able to help their children at home,” Jocelyn shares.

Rain or shine, Lizabel has shown her commitment to come to school every day. But the daily trek of six hours to and from school is wearing off her little body.

Yet, for many indigenous girls in the region, Lizabel’s situation is still better than the sad alternative. Staying in school can protect her from child marriage, child labor, domestic violence, and give her the hope to break out of the vicious cycle of poverty.

“I go to school because I want to learn. I want to be a teacher someday,” she says with the determination that could only come from someone who faces life-threatening conditions just to get to school every day.

Vision for the future

Lizabel will complete her primary education this school year. Hopefully, she will join her cousin Jinalyn in South Upi National High School. For tertiary education, they can opt for the nearest vocational school in the neighboring town of North Upi or more advanced colleges in Cotabato City. The question remains: Can their parents send them to school or will they drop out just as most children and youth in their community?

The Philippine Development Plan (2017-2022) targets economic growth for all Filipinos to become globally competitive. The progress goes beyond economic growth and peace and trust building are essential to ensure that every child, including those who are marginalized, disadvantaged, and living in poverty-stricken, remote or indigenous communities, get a quality basic education.

For every child, an education.

This is the first in a series of CRC@30 Philippines stories gathered by Shirin Bhandari, Teresa Cerojano, Claro Cortes, Jeoffrey Maitem, Charena Escala, Arby Laraño and Iris Lapid, with fact checks, technical and editorial inputs by a UNICEF Philippines team.

Related topics

More to explore, old beliefs hinder vaccination in basilan.

Traditional beliefs causing resistance against vaccines

Economic status affects children’s immunization

Parental challenges that lead to missed vaccines

Upholding the rights of every Bangsamoro child

UNICEF Philippines Chief of Advocacy and Communication Lely Djuhari meets children and families in Bangsamoro region

How daycare workers strengthen the Philippines’ human capita

UNICEF and partners empower child development workers through skills training

Scaling education programs in the Philippines: A policymaker’s perspective

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, rosalina villaneza rv rosalina villaneza chief education program specialist, teaching and learning division - department of education, philippines.

August 1, 2019

This is the second blog post in a series reflecting on key scaling-related themes discussed at the global convening of the Millions Learning Real-time Scaling Labs held in July 2019 in Switzerland.

In 2016, 586,284 children of primary school age in the Philippines were out of school, underscoring demand for large-scale programs to address unmet learning needs. As a chief education program specialist in the Department of Education (DepEd) in the Philippines, I have firsthand experience planning, implementing, and monitoring and evaluating a variety of education programs. One of our main challenges is ensuring that effective initiatives, such as with our teacher professional development program, take root and grow into sustainable, system-wide approaches for improving teacher quality and encouraging responsive instructional practices to improve learning outcomes.

Testing, refining, and scaling teacher professional development in the Philippines

With the implementation of the K-12 Basic Education Program , DepEd has taken significant strides toward fulfilling its mandate of establishing a comprehensive and integrated education system relevant to the needs of people and society. The program aims to develop productive, responsible, and engaged global citizens with the essential competencies and skills for lifelong learning and employment. We believe this begins by ensuring every child of primary school age acquires basic literacy and numeracy skills.

How was DepEd able to improve literacy and numeracy skills in recent years? We began by articulating a clear vision that focused on teachers, as they play a fundamental role in developing these skills among their students. I worked closely with my team of education experts to retool teachers’ mastery of content knowledge and pedagogical skills so they could effectively lead in the classroom. In 2015, we introduced the Early Language, Literacy, and Numeracy Program (ELLN) to improve reading and numeracy skills of K-3 learners. ELLN strengthened teacher capacity to teach and assess reading and numeracy skills, improved school administration and management, established competency standards, and introduced a school-based professional development system for teachers, the “School Learning Action Cell” (SLAC). ELLN trained teachers through a ten-day, face-to-face training module. While this approach had some impact, it was not to the extent we hoped—we wanted to reach the entire country. We understood that scaling an in-person training would be costly and time-consuming to reach primary grade teachers in all schools throughout the country. Because of this, my DepEd colleagues and I began thinking about ways we could harness technology to deliver improved teacher professional development at a national scale.

Before we selected an approach for delivering technology-enabled teacher professional development, we decided to test some things to see what worked. Over a five-month period from November 2016 to March 2017, we piloted ELLN-Digital (ELLN-D) with 4,030 K-3 teachers in 240 public elementary schools that had not participated in the ELLN program. During this piloting phase, we collaborated with the local Filipino NGO, The Foundation for Information Technology, Education, and Development (FIT-ED). ELLN-D is a blended teacher professional development program on early literacy for K-3 teachers with two components: an interactive, multimedia courseware for self-study, and collaborative learning through SLACs. Due to the success of the pilot, DepEd is scaling up the program nationally (with support from FIT-ED) to more than 38,000 public elementary schools throughout the country during this coming school year. We accomplished this by planning for scale from the start: We prioritized a focus on teachers, then pursued digital solutions that could reach teachers across our island nation—experimenting at a small scale first to determine what works—and finally implemented the program through existing SLAC structures instead of creating new ones.

What have we learned about scaling and sustaining impact?

Analyzing education programs that sustainably scale offers rich insights for people like me who work in government and are trying to serve a massive population with limited resources. What common factors enable programs to scale? Who should programs serve? How can program implementers facilitate the success of programs?

First, programs that sustainably scale are relevant and responsive to the needs of the people they serve. Second, these programs should demonstrate some meaningful change that is visible to citizens. And third, to effectively scale a program, implementers should truly understand and commit to the program, believe in its success, and go above and beyond what is expected to achieve sustainable outcomes.

In the Philippines, the following approaches helped us to create, adapt, and scale programs with the aim of sustainable impact:

- Identify learning champions at all levels: There is a need to identify and empower a pool of champions at multiple levels of the system—in the regions, divisions, communities, and schools. By doing so, these champions become agents of change. In the case of ELLN, regional directors play a critical role in implementing the program by liaising with school division superintendents and public school leaders.

- Adapt programs to local context: Those implementing programs at larger scale or in new locations should be equipped to make the programs work in their areas by contextualizing approaches to suit local needs. This includes identifying and articulating the “non-negotiables” of the original design to ensure adherence to a set standard, but those implementing in new contexts should feel agency to adjust to fit local needs. Setting specific standards on program implementation through policy guidelines or memoranda can help maintain the appropriate level of consistency in implementation between different areas. On ELLN-D, we encourage slight variations in the structure and format of SLACs in ways that make sense for a given context.

- Recognize that every idea is valuable: It is important to allow champions to implement the program with standardized guidance but recognize that adjustments and changes are not only inevitable but also beneficial. Have faith that even when the originating organization or institution is no longer around, others implementing can successfully deliver the programs and have sustained positive impact on the people they serve.

Thirty-four years working in government has provided me ample opportunity to stress-test these principles, which I believe are critically important to sustainably scaling programs. Through the implementation of ELLN, ELLN-D, and similar initiatives as part of the K-12 Basic Education Program, DepEd has fully committed to providing quality, accessible, and relevant basic education to all Filipino learners. The road ahead will not be an easy one, but through adherence to these key principles, scaling effective interventions that reach all Filipino learners will help our country continue down the path toward quality educational opportunities for all citizens.

Related Content

Jenny Perlman Robinson, Marianne Stone

June 19, 2019

Patrick Hannahan, Barbara Chilangwa

July 26, 2019

Molly Curtiss Wyss

July 12, 2019

Education Policy Global Education K-12 Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Millions Learning

Brad Olsen, John McIntosh

April 3, 2024

Darcy Hutchins, Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nora, Carolina Campos, Adelaida Gómez Vergara, Nancy G. Gordon, Esmeralda Macana, Karen Robertson

March 28, 2024

Larry Cooley, Jenny Perlman Robinson

March 8, 2024

- Top Stories

- Stock Market

- BUYING RATES

- FOREIGN INTEREST RATES

- Philippine Mutual Funds

- Leaders and Laggards

- Stock Quotes

- Stock Markets Summary

- Non-BSP Convertible Currencies

- BSP Convertible Currencies

- US Commodity futures

- Infographics

- B-Side Podcasts

- Agribusiness

- Arts & Leisure

- Special Features

- Special Reports

- BW Launchpad

- Editors' Picks

Education recovery beyond face-to-face resumption

By Pilar Preciousa Pajayon-Berse

“Literacy is a bridge from misery to hope.” — Ko f i Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations

T his article comes out a bit later than the global celebration of International Literacy Day which is celebrated worldwide in September. The theme for this year was “Transforming Literacy Learning Spaces,” a timely reminder of what needs to be done as the world continues to navigate a safe return to schools for learners of varying age after more than two years of disrupted learning.

Students lost basic numeracy and literacy skills due to the prolonged period of learning outside the classroom where such skills could have been acquired and this loss is too significant to be dismissed. According to UNICEF, learning losses due to school closures in low- and middle-income countries were up by 17% from its pre-pandemic status. From 53% before the onset of COVID-19, the percentage of 10-year-olds who are unable to read and write is now at 70%. This defines the very concept of learning poverty, an indicator introduced by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics to refer to the lack of proficiency in reading and understanding simple texts at age 10. Resolving it involves a retooling of academic policies fit for post-pandemic normalcy and a serious rethinking of the role of literacy in today’s society.

In the Philippines, the outlook towards this crisis is met with concern, a bit of defiance, but overall treated as a matter of national urgency. This is not without reason. Based on a recently released and updated version of the World Bank’s State of Global Learning Poverty (2022), the country’s learning poverty ranks among the highest in the Asian region. With learning poverty at 90.9%, the Philippines outranked all its ASEAN neighbors with the exception of Lao PDR (97.7%) and Brunei (no assessment included). Outranking does not mean the country fares well. On the contrary, the scoring is such that, the higher the number is, the poorer the performance is. Singapore, a small country with population that is just a fraction of the Philippines’, performed better at 2.8%. Indonesia, though more than double the Philippines’ population, likewise scored better at 52.8%.

THE NEED FOR AN EDUCATION PRESIDENT The dismal report on the country’s state of education was not lost on key stakeholders. Thus, it was not surprising that this became an integral part of critical conversations leading to the May 2022 national elections. The Philippine Business for Education, an advocacy group led by leaders in the business sector, expressed the need for the Filipino people to choose government leaders who are focused on education, emphasizing that literacy is an elections concern.

This sentiment was echoed by other organizations, such as Education Nation, particularly on the need to elect leaders who will prioritize reforms in the education sector. Experts from Education Nation and Philippine Business for Education, in search of an education president, released a scorecard giving former Vice-President and presidential candidate Leni Robredo a perfect score of 10/10 vis-à-vis her strategies and evidence-based solutions to address the learning crisis. Then presidential candidate Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr. received a 5/10.

MARCOS’ FIRST 100 DAYS Three months into the presidency, Mr. Marcos Jr.’s focus was on putting “together a government which is functional” (Cupin, 2022). A lot of premium was and continues to be directed towards livelihood and economic recovery as seen with the administration’s efforts to secure investment pledges, among other agreements, through bilateral deals such as the ones closed during the president’s recent trips to Singapore and Indonesia (CNN, 2022).

Aside from livelihood and economic recovery, a quick rundown of Marcos’ top policy measures during his first 100 days includes public health and peace initiatives. Partnerships with the private sector have also been actively sought out in order to advance the country’s agriculture, infrastructure, water, health, and tourism sectors (PNA, 2022). After 100 days it seems all is set in motion to “get things done” for what the administration sees as the country’s most pressing concerns, controversies and issues aside.

While assessment of an executive leader’s first months into the job rests on a lot tentative variables, it does provide a picture of how the next few years will unfold. To this end, it begs to be asked: Where does post-pandemic education recovery lie in President Marcos Jr.’s priority measures?

THE ROAD TO POST-PANDEMIC RECOVERY MUST INCLUDE EDUCATION RECOVERY It goes without saying that it will take more than 100 days to recover the learning losses incurred in the past two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. But 100 days is a good start to establish where the government stands with regard to addressing the said loss. The call for an education president who will also prioritize addressing the Philippines’ state of learning poverty is valid and must be heeded.

Students, especially in the basic level and those who are marginalized, need intensive and active support from the government to recover education lost due to school closures, aggravated by economic, personal, and social circumstances. There is a need, too, “to rebuild their mental and physical health, social development and nutrition” (UNICEF, 2022), which requires more than a return to face-to-face modality of learning. In President Marcos Jr.’s SONA (state of the nation address), references to the education sector included the students’ return to face-to-face classes, the appointment of Vice-President Sara Duterte as Education Secretary, putting an end to the poor quality of educational materials given to schools, the importance of connectivity and appropriate tools for digital education, and the reinstitution of ROTC (Reserve Officers Training Corps). Would these pronouncements suffice?

The window is narrow in terms of recovering basic literacy skills impacted by learning disruptions borne out of the COVID-19 pandemic. A more explicit expression of political will prioritizing literacy and education recovery, alongside other pressing concerns, is needed to accelerate said recovery and address the country’s high learning poverty rate in a sustained manner. Senate Minority Floor Leader Franklin Drilon’s recent statement echoed the importance of political will in focusing on urgent issues such as “inadequate healthcare and poor education” (Yang, 2022).

But then again, political will is just one thing, having a catch-up plan beyond returning to school is another. The current leadership must undertake a needs assessment in order to identify learning gaps and develop appropriate short- and long-term interventions. Merely returning to face-to-face modality in the delivery of classes might not be sufficient enough as there could be other factors at play including poor nutrition of the students or the state of school facilities. Finding out what these other factors are is critical.

Ultimately, the challenge at hand is to close the learning gap and lower the country’s learning poverty rate. Political will is needed to ensure that the role of literacy today and in the future is kept alive.

Pilar Preciousa Pajayon-Berse, PhD is an assistant professor at the Department of Political Science, Ateneo de Manila University.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Analysts see room for rate cut delay

Exports likely to miss PEDP targets in 2024

Asia’s new Quad told to step up economic game beyond security

The COVID-19 financial crisis that wasn’t

Quadricula hocus ii: history in art, longchamp makes new york debut to celebrate 70 years.

Early Childhood Education in the Philippines

- First Online: 31 December 2021

Cite this chapter

- Maria Alicia Bustos-Orosa 3

Part of the book series: Springer International Handbooks of Education ((SIHE))

336 Accesses

2 Citations

Early childhood education initiatives in the Philippines aim to address the SDG 4 Education goals for inclusive and equitable quality education for all children. Despite political and socioeconomic constraints and a growing population, the country remains committed to providing learning programs and services for its youngest populace. The government has robust legislative frameworks for providing early learning programs, namely, the “Early Years Act of 2013” and the “Kindergarten Act.” Early childhood care and education are mandated for all children ages 0–8-years old, with mandatory early childhood education beginning at Kindergarten for all 5-year-olds. The governance of early childhood education in the Philippines is split between two key agencies: the Early Childhood Care and Development Council for Pre-Kindergarten programs, which caters to 0–4-year-olds; and the Department of Education for Kindergarten programs. Statistics related to participation rates, the teacher-pupil ratio, and other key indicators are provided in this chapter. The National Early Learning Framework that serves as the basis for the curriculum framework is also presented alongside the key features of the curriculum. The identified barriers related to financing, access, quality, governance, and equity are also discussed. Finally, initiatives to address these key barriers by both government and private ECCD providers are outlined.

- Local government units

- Child Development Centers (CDCs)

- Child Development Workers/Teachers (CDWs/CDTs)

- Compulsory Kindergarten

- Pre-Kindergarten

- Developmentally appropriate practices

- Conditional cash grants

- Indigenous people

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Abrigo M et al (2019) Discussion paper series no. 2019–31: situation analysis of ECCD-F1 KD initiatives in selected UNICEF-KOICA Provinces. Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Quezon City. https://pidswebs.pids.gov.ph/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/pidsdps1931.pdf

Abulon E (2013) Barangay day care centers: emergence, current status and implications to teacher education. Conference proceeding of the Global Summit on Education, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Google Scholar

Albert J, Raymundo M (2016) Discussion paper series no. 2016–39: trends in out-of-school children and other basic education statistics. Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Quezon City. https://dirp3.pids.gov.ph/websitecms/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/pidsdps1639.pdf

ASEAN (2017) ASEAN early childhood care, development and education quality standards. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/ASEAN-ECCDE-Quality-Standards-Final.pdf

ASEAN Secretariat (2020) ASEAN sustainable development goals indicators baseline report 2020 . Jakarta, Indonesia. https://asean.org/storage/2020/10/ASEAN-SDG-Indicator-Baseline-Report-2020.pdf

Asian Development Bank (2012) Sustainable development goals Part 1: trends and tables. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/443671/part1-sdgs.pdf

Bonsu D (2020) Supporting childcare workers in the Philippines during COVID-19: interview with Dr Teresita Inciong. Early Childhood Workforce Initiative, October 23, 2020. https://www.earlychildhoodworkforce.org/content/interview-dr-teresita-inciong?fbclid=IwAR3fvExLO-crlkRAqVzff4bdT_-wl6K7nnLEv-a5vaaR0capGzs3rTpUeJI

Caoli-Rodriguez R (2008) The Philippines country case study: education for all global monitoring report 2008. UNESCO, Manila

Children not enrolled in preschool face inequalities early in life (2019) Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved from https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1107350/children-not-enrolled-in-pre-school-face-inequalities-early-in-life

Commission on Higher Education (2017) CHED memo no. 76 . Policies, standards and guidelines for the Bachelor of Early Childhood Education (BECEd), Quezon City, Philippines. https://ched.gov.ph/cmo-76-s-2017/

Department of Education (2009) DepEd order 72, s. 2009. Inclusive education as strategy for increasing participation rate of children

Department of Education (2010) DepEd order 88, s. 2010. 2010 revised manual of regulations for private schools in basic education . https://www.deped.gov.ph/2010/06/24/do-88-s-2010-2010-revised-manual-of-regulations-for-private-schools-in-basic-education-amended-by/

Department of Education (2012) DepEd order 32, s. 2012. Implementing rules and regulation of republic act (RA) no. 10157 otherwise knows as “The Kindergarten Education Act”. Department of Education, Pasig City. https://www.deped.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/DO_s2012_32.pdf

Department of Education (2016) Deped order 22, S. 2016. Implementing guidelines on the allocation and utilization of the Indigenous Peoples Education (IPEd) Program Support Fund for Fiscal Year 2016

Department of Education (2016a) Standards and competencies for five-year-old Filipino children. Department of Education, Pasig City, May 2016. https://www.deped.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Kinder-CG_0.pdf

Department of Education (2016b) DepEd order no. 47, series 2016, Omnibus policy on kindergarten education, Department of Education, Pasig, Philippines

Department of Education (2017) DepEd order 42, S. 2017 – National adoption and implementation of the Philippine Professional Standards for Teachers

ECCD Checklist (n.d.) https://ECCD Council.gov.ph/downloadables/How%20to%20Use%20the%20ECCD%20Checklist.pdf

ECCD Council and UNICEF (2010) The national early learning framework of the Philippines, Pasig City, Philippines

ECCD Council of the Philippines (2015a) Standards and guidelines for center-based early childhood programs for 0 to 4 years old Filipino children, Pasig City, Philippines. https://ECCD Council.gov.ph/downloadables/ECCD%20LOGO_STANDARDS%20AND%20GUIDELINES%20v4%20(1).pdf

ECCD Council of the Philippines (2015b) Guidelines on the registration and granting of permit and recognition to public and private child development centers/learning centers offering early childhood programs for 0 to 4 years old Filipino children, Pasig City, Philippines. https://ECCD Council.gov.ph/downloadables/ECCD%20LOGO_GUIDELINES%20ON%20THE%20REGISTRATION%20(EDITED%202017).pdf

ECCD Council of the Philippines (2015c) National early learning framework Learning Resource Package (LRP) for pre-kindergarten, Pasig City, Philippines

ECCD Council of the Philippines (ECCD Council) (2017) Annual report, Pasig City, Philippines. https://ECCD Council.gov.ph/downloadables/AR%202017.pdf

ECCD Council of the Philippines (ECCD Council) (2018) Annual report, Pasig City, Philippines. https://ECCD Council.gov.ph/downloadables/AR%202018.pdf

ECCD Council of the Philippines (ECCD Council) (2019) National early learning curriculum: learning resources, Pasig City, Philippines. https://ECCD Council.gov.ph/nelc.html

ECCD Council of the Philippines (ECCD Council) (2020) ECCD Council Advisory No. 2, series of 2020 ensuring that all children aged 0–4 years most especially those belonging to the more vulnerable sectors are provided access to the Quality ECCD (Q-ECCD) Program in the time of COVID-19, Pasig City, Philippines. https://ECCD Council.gov.ph/downloadables/ECCDC%20Advisory%202.June17.pdf

Luz J (2008/2009) The challenge of governance in a large bureaucracy (Department of Education): linking governance to performance in an under-performing sector. Human development network discussion paper series, 1. University of the Philippines, Quezon City. Human Development Network, https://www.hdn.org.ph/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/dp01_luz2.pdf

Macha W, Mackie C, Magaziner J (2018) Education in the Philippines. World Education News and Reviews, March 6, 2018. https://wenr.wes.org/2018/03/education-in-the-philippines

Manuel M, Gregorio E (2011) Legal frameworks for early childhood governance in the Philippines. Int J Child Care Educ Policy 5(1):65–76

Article Google Scholar

Metilla R, Pradilla L, Williams A (2016) The challenge of implementing mother tongue education in linguistically diverse contexts: the case of the Philippines. Asia-Pacific Educ Res 25(5–6):781–789

National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) (2009) Position statement: developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs. NAEYC, Washington, DC

National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) (2019) Voluntary national review 2019: high-level political forum on sustainable development. NEDA, Pasig City

Naylor R, Ndaruhutse S (2015) Non-government organizations as donors to education. Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2015. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232479

Philippine Education for All (EFA) (2015) National Review Report (2015) presentation at the World Education Forum, Incheon

Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) (2017) 2017 Philippine standard classification of education. Philippine Statistics Authority, Quezon City

Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) (2020) Sustainable development goals: 17 goals to transform our world. SDG Watch. https://psa.gov.ph/sdg/Philippines/baselinedata/4%20Quality%20Education

Republic of the Philippines (1994) RA No. 7836. An act to strengthen the regulation and supervision of the practice of teaching in the Philippines and prescribing a licensure examination for teachers and for other purposes

Republic of the Philippines (2013) RA No. 10410. An act recognizing the age from zero (0) to eight (8) years as the first crucial stage of educational development and strengthening the ECCD system, appropriating funds therefore and for other purposes, otherwise known as the “Early Years Act of 2013”

Samuelsson I, Park E (2017) How to educate children for sustainable learning and for a sustainable world. Int J Early Child 49:273–285

Santos A (2020) In the Philippines, distance learning reveals the digital divide . Heinrich Boll Stiftung Brussels, October 6, 2020. https://eu.boell.org/en/2020/10/06/philippines-distance-learning-reveals-digital-divide

Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) INNOTECH Regional Center for Educational Innovation and Technology (2010) Education policy paper: raising the standards of Early Childhood Care and Development. SEAMEO INNOTECH, Quezon City, Philippines

Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization Regional Center for Educational Innovation and Technology (SEAMEO INNOTECH) (2014) Quality assurance in Early Childhood Care and Development (ECCD) in Southeast Asia , Quezon City, Philippines

UNICEF Philippines (2018) Situation analysis of children in the Philippines. National Economic Development Authority and UNICEF Philippines, Philippines. https://www.unicef.org/philippines/media/556/file

Walter S, Dekker D (2011) Mother tongue instruction in Lubuagan: a case study from the Philippines. Int Rev Educ 57(5–6):667–683

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Education, De La Salle University Manila, Manila, Philippines

Maria Alicia Bustos-Orosa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Maria Alicia Bustos-Orosa .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

College of Education, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Lorraine Pe Symaco

School of education, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW, Australia

Martin Hayden

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Bustos-Orosa, M.A. (2022). Early Childhood Education in the Philippines. In: Symaco, L.P., Hayden, M. (eds) International Handbook on Education in South East Asia. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8136-3_3-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8136-3_3-1

Received : 11 November 2021

Accepted : 11 November 2021

Published : 31 December 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-8135-6

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-8136-3

eBook Packages : Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Short articles

Nov 03,2022

"Apart from developing literacy, it has also had a positive impact on students who have had a pleasant experience while going through the pandemic." In this reader submission, Anisah Khoridatul, Grade 6 Teacher SD Ar-Ridha Al Salaam, Depok, shares the details of a student diary project in place at the school.

Sep 28,2022

In this reader submission, teacher at SMA Lokon St. Nikolaus Tomohon in North Sulawesi, Indonesia, Martha Goni, shares the details of a Retreat Program the school has implemented, and the positive impact it is having on Year 12 students.

Aug 31,2022

A recent longitudinal study in the Philippines has followed a cohort of 4,500 public elementary school students for 5 years. The study found that children who attended preschool consistently outperformed those who did not in literacy, mathematics and social-emotional skills.

Jul 20,2022

New research has shown that while the use of immersive virtual reality (IVR) increases student enjoyment and presence in a task, when used on its own it does not improve procedural or declarative knowledge when compared to the more traditional learning activity of watching a video.

Jul 18,2022

Education systems across the world have taken different approaches to addressing the challenges of the pandemic. Jaylene S Miravel – a teacher at Lal-lo North Central School in the Philippines – shares how she is supporting students who are falling behind in reading during this prolonged period of remote learning.

May 18,2022

Satyam Mishra was one of two educators from India to make it into the prestigious Global Teacher Prize Top 50 for 2021. In today’s article, he shares practical examples for making mathematics more engaging and relevant for students.

May 04,2022

A new framework for learning through play has been developed to support teachers in the classroom and help guide policy and practice in the early years of schooling. The Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) and the LEGO Foundation have worked together to develop the framework.

Apr 20,2022

Students have a diverse range of personal and contextual factors that influence their access to and achievement in their education. A new global study calls for a re-evaluation of education systems to promote personalised education.

Apr 05,2022

After investing a lot of time and emotion into applying for a new job or promotion, finding out the position is not yours can have a negative impact on your confidence. In this reader submission, Dr Poppy Gibson and Dr Robert Morgan from the UK share their three steps for moving forward after being an unsuccessful candidate for a new position.

Mar 16,2022

How can you and your colleagues help students better prepare for the challenges and opportunities they’ll face in the future? A major new report looks at the global ‘megatrends’ shaping education. We’ve picked out 10 discussion points and suggestions for possible learning activities to inspire you and your colleagues, and get the conversation started.

- Subscribe Now

education in the Philippines

Whistleblower charged with cyber libel for posting teacher’s alleged abuse.

UP Law brings Philippines’ 3rd win in biggest moot court contest

DepEd orders public schools to implement distance learning on April 8

West Visayas university announces repeat of college entrance exams after leakage

DepEd: School heads authorized to suspend in-person classes amid extreme heat

Zamboanga state university shifts to hybrid classes to beat the heat

[ANALYSIS] The multiplier effect of negligence in education

![short articles about education in the philippines [ANALYSIS] The multiplier effect of negligence in education](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/The-multiplier-effect-of-negligence-in-education.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=277px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

[OPINION] Education for life: Weaving ethics in all subject areas

![short articles about education in the philippines [OPINION] Education for life: Weaving ethics in all subject areas](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/Education-for-Life-Weaving-Ethics-in-All-Subject-Domains.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

DLSU students win P1-million grant for cafeteria food waste to biogas project

Remember Kumon? Our childhood educational center is open for franchising

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

We've detected unusual activity from your computer network

To continue, please click the box below to let us know you're not a robot.

Why did this happen?

Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy .

For inquiries related to this message please contact our support team and provide the reference ID below.

share this!

April 2, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

reputable news agency

Hundreds of Philippine schools suspend classes over heat danger

by Cecil MORELLA

Hundreds of schools in the Philippines, including dozens in the capital Manila, suspended in-person classes on Tuesday due to dangerous levels of heat, education officials said.

The country's heat index measures what a temperature feels like, taking into account humidity.

The index was expected to reach the "danger" level of 42 degrees Celsius in Manila on Tuesday and 43C on Wednesday, with similar levels in a dozen other areas of the country, the state weather forecaster said.

The actual highest recorded temperature for the metropolis on Tuesday was 35.7C, below the record of 38.6C reached on May 17, 1915.

Local officials across the main island of Luzon, the central islands, and the southern island of Mindanao suspended in-person classes or shortened school hours to avoid the hottest part of the day, education ministry officials said.

The Department of Education was unable to provide an exact number of schools affected.

March, April and May are typically the driest months of the year for swathes of the tropical country. This year conditions have been exacerbated by the El Niño weather phenomenon.

Primary and secondary schools in Quezon, the most populous part of the capital, were ordered to shut while schools in other areas were given the option by local officials to shift to remote learning.

Some schools in Manila also reduced class hours.

A heat index of 42-51C can cause heat cramps and exhaustion, with heat stroke "probable with continued exposure", the weather forecaster said in an advisory.

Heat cramps and heat exhaustion are also possible at 33-41C, according to the forecaster.

The orders affected hundreds of schools in the Mindanao provinces of Cotabato, South Cotabato and Sultan Kudarat, as well as the cities of Cotabato, General Santos and Koronadal, Zamboanga regional education ministry spokeswoman Rea Halique told AFP.

Five schools in Mindanao's Zamboanga region also shut schools for the day, though local officials in the area did not recommend the suspension of in-person classes in other schools, the ministry said.

"At the Pagadian City Pilot School one (kindergarten) student and two in the elementary school suffered nosebleeds," Zamboanga regional education ministry official Dahlia Paragas told AFP.

"All of them are back at home in stable condition and were advised to avoid exposure to the sunlight."

Cotabato city experienced the highest heat index in Mindanao, reaching 42C on Monday and Tuesday, the state forecaster reported.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

A microbial plastic factory for high-quality green plastic

45 minutes ago

Can the bias in algorithms help us see our own?

3 hours ago

Humans have converted at least 250,000 acres of estuaries to cities and farms in last 35 years, study finds

Mysterious bones may have belonged to gigantic ichthyosaurs

Hurricane risk perception drops after storms hit, study shows

4 hours ago

Peter Higgs, who proposed the existence of the 'God particle,' has died at 94

Scientists help link climate change to Madagascar's megadrought

5 hours ago

Heat from El Niño can warm oceans off West Antarctica—and melt floating ice shelves from below

7 hours ago

Peregrine falcons expose lasting harms of flame retardant use

The hidden role of the Milky Way in ancient Egyptian mythology

Relevant physicsforums posts, iceland warming up again - quakes swarming.

8 hours ago

M 4.8 - Whitehouse Station, New Jersey, US

Apr 6, 2024

Major Earthquakes - 7.4 (7.2) Mag and 6.4 Mag near Hualien, Taiwan

Apr 5, 2024

Unlocking the Secrets of Prof. Verschure's Rosetta Stones

‘our clouds take their orders from the stars,’ henrik svensmark on cosmic rays controlling cloud cover and thus climate.

Mar 27, 2024

Higher Chance to get Lightning Strike by Large Power Consumption?

Mar 20, 2024

More from Earth Sciences

Related Stories

Stay hydrated: It's going to be a long, hot July for much of the U.S.

Jul 13, 2020

Expert discusses heat exhaustion and heatstroke

Jul 18, 2023

Italy's Milan records hottest day in 260 years

Aug 25, 2023

Spanish city shatters heat record

Aug 10, 2023

France sizzles in late summer 'heat dome'

Aug 21, 2023

Factors in the severity of heat stroke in China

Aug 16, 2022

Recommended for you

Study finds 17 mountains at high risk of losing biodiversity under climate change

10 hours ago

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Philippines' Basic Education Crisis . Out of the country's 327,000-odd school buildings, less than a third are in good condition, according to government figures. By Mong ...

Due to COVID-19, education issues in the Philippines have increased and received new challenges that worsened the current state of the country. With the sudden events brought about by the health crisis, distance learning modes via the internet or TV broadcasts were ordered. Further, a blended learning program was launched in October 2020, which ...

In the Philippines, the Department of Education (DepEd) expected a drop of 20 percent of enrollment last school year. Online schooling was a great challenge to teachers who were not familiar with ...

Participation in higher education in the Philippines has, without question, expanded strongly in recent years. The gross tertiary enrollment rate increased from 27.5 percent in 2005 to 35.7 percent in 2014, while the total number of students enrolled in tertiary education grew from 2.2 million in 1999 to 4.1 million in 2015/16.

The Philippine Education T oday and Its Way Forward. Rujonel F. Cariaga*. For affiliations and correspondence, see the last page. Abstract. The Philippines is concerned about the number of ...

MANILA,25 August 2021-- A child's first day of school—a landmark moment for the youngest students and their parents around the world—has been delayed due to COVID-19 for an estimated 140 million young minds, UNICEF said in a new analysis released as summer break comes to end in many parts of the world. The Philippines is one of the five ...

Aaron Favila/Associated Press. MANILA — As jubilant students across the globe trade in online learning for classrooms, millions of children in the Philippines are staying home for the second ...

The Philippines, an archipelago of 7641 islands located in Southeast Asia, had an estimated population of 106,651 million in 2018 (GovPH n.d.; UNESCO UIS 2021).It ranks 13th among the most populous nations globally and has a young population (Worldometer n.d.), 31% of whom are under 15 years old.Considered a lower-middle-income country, almost one of five families live below the poverty line.

The number of children accessing education, the quality of education they receive, and the condition of their learning environment are causes for concern. Only half of children 3 to 4 years old are enrolled in day care, and only 78 per cent complete basic education. Many schools do not have toilets and clean water.

Overview. The Philippines, an archipelago of 7641 islands located in Southeast Asia, had an estimated population of 106,651 million in 2018 (GovPH n.d.; UNESCO UIS 2021). It ranks 13th among the most populous nations globally and has a young population (Worldometer n.d.), 31% of whom are under 15 years old.

Improving the quality of education in the country is still critical and as 2019's results highlight, the Philippines needs to continue working on this. This article was first published on 5 December, 2019. Critical thinking needed to upgrade skills. Time to invest in human capital. The Philippines scored poorly for education among ASEAN ...

A study by Philippine Business for Education (PBEd) revealed that since 2010, 56 percent of teacher education schools scored below average passing rates in the board licensure examination for professional teachers. And once they are in service, challenges continue to burden them, including administrative work that takes time away from teaching.

Over 45,000 children in the Bangsamoro region don't have access to a school. SOUTH UPI, Maguindanao, Philippines —Lizabel starts her day in pre-dawn hours. With a homemade lamp in hand, she makes her way through the darkness to a spring 500 meters away to take a bath. Her village, to this day, does not have electricity.

Mapping the Terrain of Education Reforms: Global trends and local responses in the Philippines discusses: -Challenges against effective education reforms -The oscillation between global and local ...