Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- Spanish History Follow Following

- Contemporary History of Spain Follow Following

- Spain (History) Follow Following

- Spanish Civil War Follow Following

- Morisco Follow Following

- Spanish Studies Follow Following

- Nationalism Follow Following

- Catalonia Follow Following

- Andalus Follow Following

- Iberian Studies Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Emerg Themes Epidemiol

Hispanic Latin America, Spain and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean: A rich source of reference material for public health, epidemiology and tropical medicine

John r williams.

1 Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Faculty of Medicine (St Mary's Campus), Imperial College London, Norfolk Place, London, W2 1PG, UK

Annick Bórquez

María-gloria basáñez.

2 Centro Amazónico para Investigación y Control de Enfermedades Tropicales (CAICET) 'Simón Bolívar', Puerto Ayacucho, Estado Amazonas, Venezuela

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Associated Data

There is a multiplicity of journals originating in Spain and the Spanish-speaking countries of Latin America and the Caribbean (SSLAC) in the health sciences of relevance to the fields of epidemiology and public health. While the subject matter of epidemiology in Spain shares many features with its neighbours in Western Europe, many aspects of epidemiology in Latin America are particular to that region. There are also distinctive theoretical and philosophical approaches to the study of epidemiology and public health arising from traditions such as the Latin American social medicine movement, of which there may be limited awareness. A number of online bibliographic databases are available which focus primarily on health sciences literature arising in Spain and Latin America, the most prominent being Literatura Latinoamericana en Ciencias de la Salud (LILACS) and LATINDEX. Some such as LILACS also extensively index grey literature. As well as in Spanish, interfaces are provided in English and Portuguese. Abstracts of articles may also be provided in English with an increasing number of journals beginning to publish entire articles written in English. Free full text articles are becoming accessible, one of the most comprehensive sources being the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO). There is thus an extensive range of literature originating in Spain and SSLAC freely identifiable and often accessible online, and with the potential to provide useful inputs to the study of epidemiology and public health provided that any reluctance to explore these resources can be overcome. In this article we provide an introduction to such resources.

Introduction

The Spanish language is spoken as mother tongue by 300–400 million people, the majority of whom live in the 21 countries around the world where Spanish is the primary language. Yet the public health and epidemiology literature originating in these countries is not readily accessed by peers in the field, who tend more frequently to consult and refer to literature catalogued in English language databases [ 1 , 2 ]. In consequence, many local, national, and regional studies of interest, as well as the possibility of establishing fruitful collaborations in important areas of epidemiology research and public health are missed by the international community [ 3 ]. Here we describe and review a number of epidemiological resources from Spain and Spanish-speaking Latin America including the Hispanic Caribbean (SSLAC) -in other islands of the 'Antilles' English, French, and Dutch are spoken. We do not, by any means, aim to provide an exhaustive list, a task that would require far more space than we have at our disposal, but we do attempt to share with the readers a selection that we have found useful in our own professional practice.

The article is organised as follows. We commence by briefly outlining some historical milestones in the development of epidemiology and public health in Spain and of the Universities and Faculties of Medicine in the now predominantly Spanish-speaking countries of Latin America and the Caribbean. Second, we summarise briefly some important early epidemiological research in SSLAC mainly in the area of tropical infectious diseases, and distinctive aspects of the epidemiologies of Spain and SSLAC. Third, and again briefly, we note the results of several bibliometric studies in relation to Spain and SSLAC. Next, we introduce a selection of the Spanish and SSLAC databases available, and a selection of the relevant journals providing tables summarising these (Tables (Tables1 1 and and2). 2 ). We conclude by emphasising the range and potential value of the bibliographic resources available and, focusing on SSLAC, discuss the origins of a distinctive approach to the study of public health and the background to an equally distinctive epidemiological context, characteristic features which may merit the attention of workers in the field.

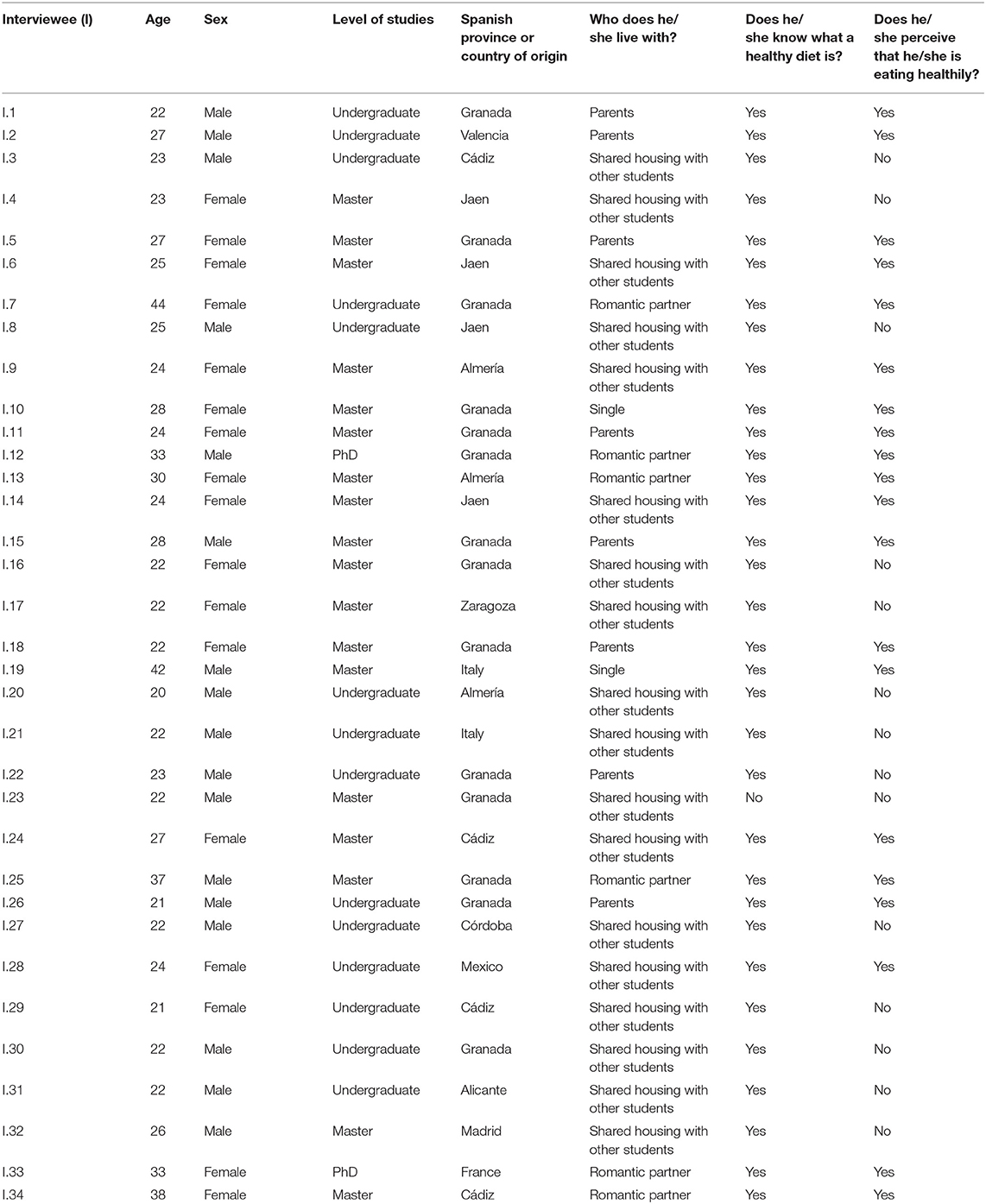

A selection of health science journals from Spain and Hispano America (part 1)

A selection of health science journals from Spain and Hispano America (part 2)

Our aim in presenting this paper is to create an awareness among researchers beyond the boundaries of Spain and SSLAC of the richness and diversity of these resources, and to facilitate their use. We hope that this may: a) help to improve the comprehensiveness and quality of reviews and meta-analyses and minimise possible bias in literature searches; b) widen opportunities for collaborations with workers sharing similar interests, and c) facilitate a fuller understanding of the field in general and of specific areas of interest within it.

Historical background

Epidemiology and public health in spain.

Early in the previous millennium the Islamic south of Spain, Al-Andalus, was the centre of scientific and medical knowledge in Europe. In addition, the first universities in Christian Spain (including the present day University of Salamanca), were founded in the 13th C, well before the 15th C completion of the Spanish Reconquest. The beginnings of the study of public health in Spain were seen during the Renaissance under the sponsorship of Philip II [ 4 ], in the same era as enormous wealth was flowing into Spain from the Americas. Despite all this, as the 19th C drew to a close, Spain was, in Western European terms, an underdeveloped country characterised by poverty and life expectancy in 1901 of a mere 40 years [ 5 ]. Also, despite its colonial history, and unlike Belgium, Germany and the UK, in Spain there had been little development in the area of tropical medicine [ 6 ]. However, it was this epoch at the turn of the 20th C that saw the laying down of the foundations of an effective public health system. The Instituto Nacional de Higiene "Alfonso XIII" (INH) had its origin in this period [ 6 ], and a National School of Health (Escuela Nacional de Sanidad, ENS) was founded in 1924 [ 7 ]. Until the INH and ENS merged in 1934 as the Instituto Nacional de Sanidad (INS), the place of the teaching of 'hygiene' in the Universities had been precarious, being far below the levels seen in other European countries [ 8 ]. Unfortunately, the 1936–39 Spanish civil war interrupted this development of the study of epidemiology and public health for some years, and it was not before 1986 that this work began to be revitalised with the reinvention of the INS through the founding of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III [ 6 ]. Since then, in recent years (1995–2005) authors based in Spain have accounted for some 2,000 of the papers relating to infectious disease identified in the PubMed database [ 9 ]. However a study in 1999 had also identified a further 3,000 papers relating to public health and health policy in Spanish journals indexed in the Spanish Medical Index (Índice Médico Español, IME) [ 10 ], and a similar study one year earlier found that 2–3% of the papers indexed in IME related to epidemiology or public health, with only 0.2% published in English [ 11 ].

The University and the teaching of Medicine in Latin America

Pre-dating independence from Spain by nearly three centuries, the early dates of foundation of the first universities in what are now the Spanish-speaking nations of Latin America and the Caribbean, may not be well recognised in the Anglophone world. Claims to be the oldest university in Latin America are controversial, but in 1538 the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo [ 12 ] was founded in what is now the Dominican Republic, although not officially recognised until two decades later. In the meantime were founded in 1551 the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (UNMSM), Perú [ 13 ] and also the Real y Pontificia Universidad de México (RPUM) which, after an interrupted history in the 19th C was to become the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) [ 14 ]. These were followed by the foundation of the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (Argentina) [ 15 ] and the Universidad de Chile [ 16 ] in 1622. The oldest medical school in the USA is the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, founded in 1765, but the faculties of medicine of UNMSM and UNAM both lay claim to earlier beginnings. Two chairs in medicine were established at UNMSM in 1571, with a functioning faculty by the 17th C, although not formally constituted until 1856. At RPUM the first course on medicine began in 1579 [ 17 ] (and, despite the 19th C closures of RPUM, the medical school continued in being until absorbed into the refounded university which became UNAM). In 1676 the Universidad San Carlos de Guatemala also officially opened its doors, incorporating the study of medicine along with theology and law [ 18 ].

Early epidemiological work in Latin America

This long history perhaps reflects the fact that in contrast to the colonisation of Africa and the English Caribbean, primarily focused on trade and the exploitation of resources, in Latin America the plundering of wealth was accompanied by a parallel focus on establishing and peopling a (Catholic) civilisation and conversion of the many indigenous populations [ 19 ]. In many aspects this latter focus was a reflection – perhaps even, in a sense, a continuation – of the methods of the Reconquista, i.e. the reconquest of the Iberian peninsula by the Christians after eight centuries of Islamic rule by the Moors, a process that proved a training ground for the conquests in the Americas and which was completed with the fall of Granada in 1492, the very year that Christopher Columbus made his first encounter with the 'New World' [ 19 ].

The medical science and epidemiology that grew from this environment in Latin America was faced with the challenge of both autochthonous and imported infections. A surprisingly early record of a correctly made, but overlooked association between biting insects and disease dates back to 1764 and comes from Peru, where the Spanish-born physician Cosme Bueno described both bartonellosis (Carrion's disease) and cutaneous leishmaniasis and attributed it to the bite of small flies called 'uta' (a term still used in the Peruvian highlands to refer to the disease and the sandfly vectors) [ 20 ]. The accurate deduction of this relationship preceded the formulation of the 'germ theory' by Pasteur in 1877. From the late 19th C important figures emerge in Latin America, perhaps one of the most prominent being Carlos Finlay in Cuba, who proposed and tried to demonstrate in 1880, while conducting important work on cholera, that mosquitoes transmit yellow fever. In the early 20th C Carlos Chagas in Brazil discovered the presence of Trypanosoma cruzi in human blood (the causative agent of what came to be known as Chagas disease) and in 1909 unravelled its transmission by triatomines [ 21 , 22 ]. Rodolfo Robles in Guatemala was the first to hypothesise in 1915 the role of blackflies as vectors of human onchocerciasis (called Enfermedad de Robles or Robles disease in Guatemala) and link the infection to blindness, predating by nearly 10 years the work of Blacklock incriminating Simulium damnosum as the vector of river blindness in Africa [ 23 ].

Nevertheless, as late as 1960, as Director of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Dr Abraham Horwitz [ 24 ] was still able to concur with the observation that in Latin America epidemiology was the "Cinderella of the medical sciences" [ 25 ]. Since then epidemiology in Latin America has made substantial advances although in many countries an "epidemiological polarisation" prevails, where communicable diseases persist but chronic diseases occupy a critically important and increasing place [ 26 , 27 ].

Epidemiology in Spain and Latin America

Spain, since arrival of democracy following the end of the Franco dictatorship in the 1970s, has rapidly achieved a Western European standard of living with research in public health and epidemiology becoming associated with the European tradition [ 9 , 28 ]. In contrast, globally, Brazil and Hispanic Latin America exhibit the highest national levels of health inequality [ 29 - 32 ] reflected in a tradition of research and literature on health inequalities [ 33 ] and which is associated with the social medicine movement, a movement having a historical role in attempting to resist both colonialism and post-independence military dictatorships [ 34 , 35 ]. Regrettably there appears to be little knowledge in the English-speaking world of the fruits of this research in the field of social medicine [ 36 ]. With regard to this, although Almeida-Filho et al. [ 33 ] identified a relative neglect of gender, race, and ethnicity issues in health inequity research in the Latin American literature, they also highlighted, at the methodological level, a remarkable diversity of epidemiological research designs and a refined ecological tradition, with consideration of aggregate and ethnographic methods not evident in other research traditions.

Bibliometrics and databases

Bibliometric studies.

In public health and epidemiology, Falagas and colleagues [ 37 ] reported that between 1995 and 2003, 686 articles (1.4% of the global total) originating from Latin America and the Caribbean were published in Thomson-ISI indexed journals, a number of the same order as for Eastern Europe but far below that of Western Europe or the United States of America. The mean impact factor of 1.7 however was comparable, exceeding that of W Europe (1.5) and approaching that of the USA (2.0). In parasitology, Falagas et al. [ 38 ] reported that in the PubMed database over the same period, 17%, of journal articles originated from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), comparable with the production from the USA (20%), and that since 2001 increasing production in the former had resulted in LAC displacing the USA from second place behind W Europe (with 35% of the articles). Falagas et al. [ 39 ] subsequently reported that LAC assumed third place behind W Europe and Africa in production of articles in the field of tropical medicine with 21% of articles published, ahead of the USA with 11%. However as with parasitology, the mean impact factors were lower -in tropical medicine 0.90 for LAC compared with 1.65 for USA and 1.21 for W Europe. In the fields of microbiology [ 40 ] and infectious diseases [ 41 ] 1995–2002 productivity in terms of PubMed indexed journals was much lower with just over 2% of articles in both fields although the mean impact factor, 2.89, just exceeded that of W Europe with 2.82, with 3.42 for articles originating in the USA. The latter study also noted that, together with Africa and E Europe, the rate of increase in production in Latin America exceeded that of W Europe and the USA, and that if existing rates of increase were maintained their production would exceed that of the USA within 20 years or so.

A recent bibliometric study [ 33 ] using both PubMed and the Literatura Latinoamericana en Ciencias de la Salud (LILACS) [ 42 ] database noted that observed differences in research production between SSLAC countries could be misleading, e.g. the searching of indexed journals favours Mexico as, for reasons of geography, Mexican researchers engage in relatively more scientific exchange with North American universities. In fact, Hermes Lima et al. [ 43 ] point out that in the field of biomedicine, the predominant pattern of collaborations is South-North, favouring North America, rather than strengthening South-South links between countries within Latin America. However it is clear that among dominant factors influencing levels of research publication in public health are, of course, national expenditure on health research and, by implication, the level of economic wealth, an illustration of which is provided in Figure Figure1 1 .

National expenditure on research and economic performance versus research productivity . a) Relationship for several Latin American countries between health research expenditure http://www.cohred.org/main/publications/backgroundpapers/FIHR_ENG.pdf and: i) journal articles on public health (triangles); ii) total public health research publications (crosses) indexed in LILACS-SP for 1980–2002) [ 45 ]. b) Relationship between gross domestic product (GDP) and biomedicine research productivity for three higher income countries and for Latin America (source: Falagas et al [ 37 ]).

Bibliographic databases

The LILACS database is a key resource for the identification of publications originating in Latin America and the Caribbean, whether written in English, Spanish or Portuguese. It includes theses, books and proceedings as well as journal papers. Clark and Castro [ 1 ] observed that "LILACS is an under-explored and unique source of articles whose use can improve the quality of systematic reviews" (for a succinct description of LILACS and how to access it see the article by Barreto and Barata in this thematic series [ 44 ]). Of 64 systematic reviews published in five high impact factor medical journals, only 2 had used LILACS whereas, of the remaining 62 reviews, 23 restricted their search to English language articles with only 18 clearly specifying no language restriction; for 44 of the reviews a subsequent LILACS search revealed articles which had been omitted but which were suitable for inclusion [ 1 ], evidence of the "lost science" highlighted by Gibbs [ 3 ]. Between 1980 and 2002, of the 98,000 publications relating to public health indexed in LILACS, Brazil and a group of seven countries of SSLAC (in descending order of production: Chile, Mexico, Argentina, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru and Cuba) each accounted for 42–43% [ 45 ]. In these 7 countries of SSLAC the majority (57–89%) of publications were in the form of journal articles with the exception of Peru where 69% was in the form of monographs [ 45 ]. Between 94% and > 99% of publications from the SSLAC group, depending on country, were written in Spanish with the majority of the rest in English; Venezuela, with 4%, lead the production of publications in English [ 45 ]. Many of the publications in Spanish, however, also had abstracts in English. These publications were to be found in some 400 journals based in Brazil and over 500 journals in SSLAC, although 47% of the articles were located in just 91 journals, of which those publishing the largest number of articles in Spanish were Revista Médica de Chile (Chile), Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición (Venezuela), Salud Pública de México (México), Gaceta Médica de México (México), Revista Chilena de Pediatría (Chile) and Revista Médica del IMSS (México) (see Macias Chapula [ 45 ] for the full list of 91 journals and their specialisms).

The LILACS database is nested within the Virtual Health Library (VHL) [ 46 ] of the Pan-American Health Organization's (PAHO) Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information (BIREME) (Figure (Figure2). 2 ). The VHL (or BVS, Biblioteca Virtual en Salud [ 47 ]/Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde [ 48 ]) also encompasses a number of other relevant databases, ADOLEC (Literature on Adolescence Health) and HISA (Latin American and Caribbean History of Public Health) being just two examples. The VHL portal also provides for searches of MEDLINE and the Cochrane database.

Databases for Spanish language health journals . Diagram illustrates databases offering free access to scientific articles with emphasis given to Public Health and Epidemiology journals written in Spanish. Within each box is indicated year of launch, founding institution or organisation, and subjects covered. Arrows represent links between services.

Whilst LILACS provides a comprehensive database of Latin American literature, both peer-reviewed and "grey", on public health and epidemiology, the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) [ 49 ], a collaboration between a number or organisations, including BIREME, offers a portal providing free access to many journals from Latin America and the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) (see Barreto and Barata [ 44 ] in this thematic series for a succinct introduction to this also).

VHL/LILACS is not the only database which specialises in journals emanating from Latin America and/or Spain; see Figure Figure2. 2 . For example, LATINDEX [ 50 ] offers a directory of a large number of Spanish and SSLAC journals in all the sciences, a proportion of which appear in a catalogue selected according to international quality standards. There are several others resulting from national or multinational initiatives (e.g. IMBIOMED [ 51 ]; LASM (Latin American Social Medicine) [ 52 ]) and focusing on medicine and health or with a wider remit (e.g. E-REVISTAS [ 53 ]; CLASE [ 54 ], PERIÓDICA [ 54 ]; REDALYC [ 55 ]). Both PERIÓDICA and CLASE were created by UNAM's Centro de Información Científica y Humanística (CICH) in the 1970s and constitute relevant regional sources of information. Regional full text access to articles appearing in the better quality health sciences journals published in Mexico is also available using the CD-ROM based ARTEMISA (Artículos Editados en México de Información en Salud) database or online since 2006 at Medigraphic Literatura Biomédica [ 56 ]. Table Table3 3 provides a list of such databases together with the addresses of the relevant websites.

Bibliographic databases. A selected list of less widely known databases indexing significant numbers of Spanish language articles

VHL however provides the best starting point for investigating the rich range of Spanish language literature in the field as well as providing a number of other tools such as its "Evidence Portal" and "Health Information Locator". In addition there are many links to national VHL sites which, whilst there is a substantial degree of overlap with the main VHL web site, also provide additional resources – national SciELO sites for example may include journals not featured on the main SciELO site. In fact the wealth of resources is such that it would not be surprising if first-time users experienced a certain degree of bewilderment in navigating their way through this network and, in truth a full description of what is available would stretch to many pages (such a description would also quickly become obsolete as development and consolidation continue to proceed hand in hand).

Focusing now on the Spanish and Latin American Spanish-language journals themselves, Tables Tables1 1 and and2 2 provide a summary of many of those which we feel may be of use to those working in the field of public health or epidemiology (we should emphasise that this list is by no means exhaustive). Amongst other things Tables Tables1 1 and and2 2 indicate the general area of interest for each journal, frequency of publication and addresses of the web pages, many within the SciELO database, where further details and/or online copies of journal articles may be available (a number of these journals are indexed in widely used databases such as MEDLINE, EMBASE or Ulrich's and links for some are also provided from the websites of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors [ 57 ] or World Association of Medical Editors [ 58 ]). While the number of journals specifically focused on public health and epidemiology is not great, many others may potentially be of interest to workers in the field. A significant number of these journals provide an abstract in English and some also in Portuguese (see Tables Tables1 1 and and2). 2 ). Of those focussed on public health, it is worth mentioning a few that have greater visibility (see Table Table4). 4 ). The Revista de Salud Pública , published by the Universidad Nacional de Colombia since 1999, treats a wide range of subjects relevant to national as well as international public health. It is indexed in MEDLINE, SciELO, LILACS, LATINDEX as well as in two Colombian databases: the National Index of Scientific and Technological Colombian Journals and LILOCS (Literatura Colombiana de la Salud). In 2006 it had an impact factor on a two year basis of 0.18 and a citation half life of 3.25 years in the SciELO database (Table (Table4). 4 ). Two Cuban journals, Revista Cubana de Higiene y Epidemiología and Revista Cubana de Salud Pública offer slightly different approaches to public health. The first is more empirical and reports findings of studies in environmental hygiene, food-related infections and occupational medicine while the second mainly publishes essay-type articles on historical, controversial or novel issues relevant to public health involving professionals from other fields. The SciELO 2006 impact factor for these journals are 0.1591 and 0.0395 respectively while the half lives are 5.17 and 2.25 years respectively, suggesting that the Revista Cubana de Higiene y Epidemiología has more visibility. Salud Pública de México , the official journal of the National Institute of Public Health addresses a broad scope of subjects, publishing original articles resulting from research in parasitic diseases' epidemiology to health economics. Its SciELO impact factor for 2006 was 0.2747 and its half life was 4.86 years which reveals its importance in the field. All the articles are available in Spanish and English. Of the Spanish journals, Gaceta Sanitaria , Revista Española de Salud Pública , and Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra provide a robust assortment of information. Gaceta Sanitaria is published by the Spanish Society of Public Health and Sanitary Administration (SESPAS) and it has recently been indexed in the Thomson database with an ISI impact factor of 0.825 in 2007 (note the contrast in scale between ISI and SciELO impact factors, reflecting differences in their corresponding bibliometric algorithms; aside from the issue of scale, Figure Figure3 3 illustrates disparities between rankings for a selection of journals). Revista Española de Salud Pública had an impact factor of 0.0417 and a citation half life of 4.14 years in SciELO in 2006. Although Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra is indexed in SciELO, bibliometric information is not provided, however it does have a SCIMago Journal Rank (SJR) of 0.044 (a measure of impact in the SCImago – Science Visualisation – database), while Gaceta Sanitaria has an SJR of 0.068 and Revista Española de Salud Pública has an SJR of 0.052 in this database. An important source of information of public health in Latin America is the Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública/Pan American Journal of Public Health (previously the separate journals: Boletín de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana and Bulletin of the Pan American Health Organization ) publishing in Spanish, English, and Portuguese by PAHO since 1997. This publishes original research and analysis, with a focus on health promotion and the evolution of the programmes with which PAHO is involved. Its 2006 SciELO's impact factor was 0.2030 with a citation half life of 4.52 years.

Public health and epidemiology journals of Spain and Latin America

The table shows those journals having a ranking from at least one of the Thomson ISI, SCImago or SciELO ranking lists

NB 1 Brazilian journals which also publish articles in Spanish are not included in this table as these are dealt with elsewhere in this issue (see Barreto and Barata [ 44 ])

2 The Institute of Scientific Information's (ISI) impact factor is calculated using data from the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) from the Science Citation Index (SCI). The algorithm is as follows: the number of times articles published in the former two years were cited in indexed journals during the following year divided by the number of published articles in these two years http://www.thomsonreuters.com/business_units/scientific/free/essays/impactfactor/ . The SciELO's impact factor follows the same algorithm but takes citations given by journals indexed in the SciELO database and does it for the former two and three years. The SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) uses a different and more complex algorithm developed by Stanford University for Google named PageRank, the basic concept being that each journal's prestige is dependent on the prestige of the journals citing it which are themselves dependent on the prestige of the journals citing them et cetera . It is an iterative process based not only on the number of citations a journal receives but on where these citations come from http://www.scimagojr.com/SCImagoJournalRank.pdf and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PageRank

Scatter plots illustrating lack of consistency between measures of impact . a) Thomson-ISI impact factors versus SCImago Journal Rankings for 2006 for 28 journals of health and life sciences from Spain and Latin America found in both indexes; b) Thomson-ISI impact factors versus SciELO impact factors for 10 journals of health and life sciences from Spain and Latin America found in both indexes.

It is perhaps surprising to witness the quantity and diversity of databases and interfaces devoted to the Spanish language literature in public health and epidemiology, a result of several independent initiatives. In the period from 1996 to 2003 over 10 databases were launched, and although two (LILACS and SciELO) have achieved international recognition, most of this effort appears to have been neglected by the wider international scientific community. Only rarely are these databases used in systematic reviews and citation of articles in Spanish are infrequent in papers in the English language journals of Europe, North America or Australasia.

The multiplicity of resources may be a problem in itself but development is ongoing and some degree of consolidation is likely although the fact that a number of countries are involved, with varying research standards and infrastructure and, indeed, differing policy objectives for public health, will make this task harder and perhaps slow down their adoption by a wider audience. Nevertheless the creation of LILACS and SciELO, robust sources for dissemination of scientific literature, is worthy of remark. Collaborations between Latin American countries have been relatively uncommon, yet these countries now are participating in the expansion of existing initiatives such as VHL/BVS, LILACS and SciELO and links are being developed between independent initiatives such as LATINDEX and REDALYC.

In the context of searching author names in any bibliographic database, it may be worth mentioning in passing a peculiarity of individuals' family names in many Spanish-speaking countries, and one which can impact on the search for publications by a specific author is the use together of paternal and maternal family names (although for everyday purposes only the paternal family name may be given) [ 59 - 62 ]. As an example, let us take the name of an individual from the Spanish-speaking world with perhaps the greatest global 'name recognition', the former Cuban leader Fidel Castro. His full name is Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz, the paternal family name being 'Castro' and the maternal being 'Ruz'. Were he to be an author of a paper indexed in bibliographic databases, therefore, his name might be cited in different ways in different databases as FAC Ruz, as FA Castro Ruz or as FA Castro, clearly a potential source of confusion.

The increasing interest in disseminating research findings within Spain and Latin America arises in part from the need to keep pace with the global growth of Internet-based resources, but mainly because there is a tradition of research in this field which has been growing in the past few decades [ 33 , 63 ]. The end of the Franco regime in Spain and the emergence of the socialist movements across Latin America can be considered to have provided the sparks for the modern development of public health in these countries, a development which occurred rather late compared to that in other countries. Reintegration into the European mainstream influenced its development in Spain. The influence of specific ideological movements in Latin America meant that it was approached in a somewhat different manner to that in other parts of the world [ 64 ]. Much earlier, towards the end of the 18th C the work of Espejo in Ecuador [ 65 - 67 ] and that of Virchow in Europe [ 68 ], in the first half of the 19th C, had already provided a basis from which the study of social medicine in Latin America could develop, however the most significant step in the development of this study occurred in Chile in the 1930's with the epidemiological work of the physician and pathologist Dr Salvador Allende [ 34 , 69 - 71 ]. During the 1960's and 70's the political parties of the left, including that of Allende who was to become President of Chile, integrated health as a priority in their programmes and denounced the role of poverty as a determinant of disease [ 34 , 72 , 73 ]. The study of social medicine began to expand rapidly and although many experts in the field were forced into exile at the onset of the military dictatorships in the 1970's they continued to contribute from abroad. In those countries with less repressive regimes the development of theory continued to advance the debate [ 34 ]. This social medicine approach integrates health and disease in its social, economical and political context and stresses the multi-factorial nature of causality and implies a need for more qualitative research, as well as a variety of study designs and methodologies [ 33 ], a distinctive approach to epidemiology which may warrant the interest of the wider international scientific community.

Apart from its distinctive vision of epidemiology, Latin America also represents a very rich and distinctive context which may be of special interest to epidemiologists and other health professionals. Most countries in this region are now experiencing an epidemiological transition characterised by the coexistence of infectious diseases and the so called chronic diseases of "modern life". While, in the second half of the 20th C, huge improvements in public health indicators (e.g. life expectancy and infant mortality) were observed, epidemics of non-communicable diseases began to grow [ 64 ]. Globalisation here has been characterised by rapid industrialisation, uncontrolled urbanisation and important changes in lifestyle, all contributing to the emergence of new epidemics but also to the resurgence and/or spread of infectious diseases such as dengue, cholera, and Chagas disease which were considered to belong to the past [ 64 ] or be confined to rural areas. Unregulated industrialisation of agriculture characterised by unrestrained release of pesticides and other chemicals not only caused environmental damage but also the appearance of occupational diseases [ 64 ]. Two out of the world's ten most populous cities are now found in Latin America, Mexico City and São Paulo, both harbouring over 20 million inhabitants. This accelerated growth was not followed by adequate provision of the basic requirements for human well-being, clean water and sewage disposal. Also, fuelling the burden of non-communicable diseases are changes in nutritional habits and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle. In 2000, 31% of deaths were caused solely by cardiovascular diseases [ 74 ], but widespread occurrence of cardiomyopathies arising from Chagas' disease [ 75 ] emphasises the overlap between the epidemiologies of chronic and infectious disease. With the highest levels of social inequality in the world [ 74 ], Latin America has been facing dramatic increases in violence fostering mental health problems as well as high rates of intentional injuries [ 74 ]. Inequities in access to health-care depending on socio-economic status, gender and ethnicity continue to grow [ 76 ]. Here we cannot give a comprehensive overview of epidemiology and public health in Latin America, but we wish to remind the reader of its complexity and distinctive nature and of the potentially important contribution that the research undertaken in this region could bring to the international community.

Unfortunately, there is often a perception that Spanish and Latin American journals in the fields of epidemiology and public health are of lower scientific quality. In this same issue, Barreto and Barata [ 44 ] comment on the inadequacy of the ISI impact factor to rate foreign language articles on public health and epidemiology and they describe several alternatives proposed by different researchers. The topic is well documented in his article and we will not go over it again, but it is perhaps of interest to note SCImago, employing a recently launched scientometric journal ranking algorithm, developed jointly by researchers from a number of Spanish universities [ 77 ]. This project offers an alternative, and perhaps a more appropriate means to judge the soundness of scientific articles, which may be particularly useful in relation to those written from Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking countries. Although the language barrier remains a problem, many journals now provide abstracts in English and, increasingly, journals and databases are encouraging bilingual and multilingual publication.

Dissemination of information about the resources described here is not only important to facilitate global awareness of relevant research and to stimulate the collaboration between Spanish-speaking countries and the international community, but also to encourage and facilitate it within Spain and Latin America, even at the level of individual countries. It has been found that these resources are rarely accessed by researchers in Latin American countries. A study among researchers in 16 countries showed that only 6% of them used LILACS and that after MEDLINE the most accessed interfaces were Google and Yahoo [ 78 ]. Institutions in the region rarely provide interfaces such as free access to online libraries and furthermore, in some settings, slow and unreliable Internet connections may take an hour or more to download a single paper, if at all. The price of articles is generally a barrier to the dissemination of scientific literature, which is exacerbated in countries with poor resources and especially in public universities. Open access publishing will certainly make a huge difference, but first requires awareness of the availability of these resources.

In summary, there is much published Spanish language material which is available online, most comprehensively via VHL, LILACS and SciELO. Nevertheless these resources are under utilised, not only by non-Spanish-speaking researchers but also by many researchers based in Spanish-speaking countries. We hope that this article will have contributed to the creation of an awareness of the existence of these resources and that the detailed information provided will facilitate their access.

• There is evidence of omission by systematic reviews of relevant studies published in Spanish

• A wealth of bibliographic databases focusing on journals of epidemiology and public health from Spain and Latin America is available

• Historical and present day contexts of public health studies in Spain and Latin America are discussed, emphasising the development of theories of social medicine

• The main features of the most prominent databases are described.

• A detailed list of relevant journals is provided

Abstracts in non-English languages

The abstract of this paper has been translated into the following languages by the following translators (names in brackets):

• Chinese – simplified characters (Mr. Isaac Chun-Hai Fung) [see Additional file 1 ]

• Chinese – traditional characters (Mr. Isaac Chun-Hai Fung) [see Additional file 2 ]

• French (Mr. Philip Harding-Esch) [see Additional file 3 ]

• Spanish (Dr. María Gloria Basáñez) [see Additional file 4 ]

List of abbreviations

ADOLEC: Literature on Adolescence Health database; ARTEMISA: Artículos Científicos Editados en México sobre Salud [Database of science articles on health published in Mexico]; BIREME: Biblioteca Regional de Medicina [Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information]; BVS: Biblioteca Virtual en Salud/Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde [Virtual Health Library]; CICH: Centro de Información Científica y Humanística, UNAM; CLASE: Index of documents published in Latin American journals specialising in the social sciences and humanities; ENS: Escuela Nacional de Sanidad, Spain; E-REVISTAS: Plataforma Open Access de Revistas Científicas Electrónicas Españolas y Latinoamericanas [Open Access Platform for Spanish and Latin American Scientific Electronic Journals]; HISA: Latin American and Caribbean History of Public Health database; IMBIOMED: Índice Mexicano de Revistas Biomédicas Latinoamericanas [Mexican Index of Latin American Biomedical Journals]; IME: Índice Médico Español [Spanish Medical Index]; INH: Instituto Nacional de Higiene "Alfonso XIII", Spain; INS: Instituto Nacional de Sanidad; LAC: Latin America and the Caribbean; LASM: Latin American Social Medicine database; LATINDEX: Sistema Regional de Información en Línea para Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal [Regional online information system for Scientific Journals of Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal]; LILACS: Literatura Latinoamericana en Ciencias de la Salud [Latin American Literature in Health Sciences]; LILOCS: Literatura Colombiana de la Salud [Colombian Health Literature database]; PAHO: Pan American Health Organization = Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS); PERIÓDICA: Índice de Revistas Latinoamericanas en Ciencias [Index of documents published in Latin American journals specialising in science and technology]; REDALYC: Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal [Network of Science Journals of Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal]; RPUM: Real y Pontificia Universidad de México; SciELO: Scientific Electronic Library Online; SCIMago: Imago Scientae [Science Visualization]; SESPAS: Sociedad Española de Salud Pública y Administración Sanitaria [Spanish Society of Public Health and Health Administration]; SJR: SCIMago Journal Rank; SSLAC: Spanish-speaking countries of Latin America and the Caribbean; UNAM: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; UNMSM: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Perú; VHL: Virtual Health Library.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JRW conceived the paper; AB and M-GB helped prepare figures and tables; AB drafted the discussion; all authors contributed to the researching of the databases and the writing of the paper, and read and approved the final version submitted.

Supplementary Material

Chinese abstract – simplified characters. Translation of the English abstract into Chinese using simplified characters.

Chinese abstract – traditional characters. Translation of the English abstract into Chinese using traditional characters.

French abstract. Translation of the English abstract into French.

Spanish abstract. Translation of the English abstract into Spanish.

Acknowledgements

M-GB thanks the Medical Research Council UK and AB thanks UNAIDS. All the authors thank two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions. Rosalind M. Eggo copy-edited the final version of the manuscript.

- Clark A, Castro A. Searching the Literatura Latino Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS) database improves systematic reviews. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002; 31 :112–114. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.112. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Langer A, Díaz-Olavarrieta C, Berdichevsky K, Villar J. Why is research from developing countries underrepresented in international health literature, and what can be done about it? Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004; 82 :802–803. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gibbs W. Lost science in the Third World. Scientific American. 1995; 273 :92–99. (link not avalable at pubmed) [ Google Scholar ]

- López Piñero J. Los orígenes de los estudios sobre la salud pública en la España renacentista. Revista Española de Salud Pública. 2006; 80 :445–486. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martínez Navarro J. Salud pública y desarrollo de la epidemiología en la España del siglo XX. Revista de Sanidad y Higiene Pública. 1994; 68 :29–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nájera Morrondo R. El Instituto de Salud Carlos III y la sanidad española. Origen de la medicina de laboratorio, de los institutos de salud pública y de la investigación sanitaria. Revista Española de Salud Pública. 2006; 80 :585–604. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Benavides F. Epílogo para después de un paseo con Don Marcelino Pascua. Revista Española de Salud Pública. 2006; 74 :95–98. [ Google Scholar ]

- Báguena Cevallera J. La higiene y la salud pública en el marco universitario español. Revista de Sanidad y Higiene Pública. 1994; 68 :91–96. [ Google Scholar ]

- Durando P, Sticchi L, Sasso L, Gasparini R. Public health research literature on infectious diseases: coverage and gaps in Europe. European Journal of Public Health. 2007; 17 :19–23. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm066. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- López Cózar E, Ruiz Pérez R, Jiménez Contreras E. Criterios Medline para la selección de revistas científicas. Metodología e indicadores. Aplicación a las revistas médicas españolas con especial atención a las de salud pública. Revista Española de Salud Pública. 2006; 80 :521–555. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Álvarez Solar M, López González M, Cueto Espinar A. Indicadores bibliométricos, análisis temático y metodológico de la investigación publicada en España sobre epidemiología y salud pública (1988–1992) Medicina Clínica. 1998; 111 :529–535. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo – Primada de América http://uasd.edu.do/

- UNMSM http://www.unmsm.edu.pe/

- Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México http://www.unam.mx/ [ PubMed ]

- Universidad Nacional de Córdoba http://www.unc.edu.ar/

- Universidad de Chile http://www.uchile.cl/

- Facultad de Medicina UNAM http://www.facmed.unam.mx/fm/index.html

- Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala http://www.usac.edu.gt/

- Williamson E. The Penguin History of Latin America. London: Penguin Books Ltd; 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Herrer A, Christensen H. Implication of Phlebotomus sand flies as vectors of bartonellosis and leishmaniasis as early as 1764. Science. 1975; 190 :154–155. doi: 10.1126/science.1101379. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harwood R, James M. Entomology in Human and Animal Health. 7. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co Inc; 1979. [ Google Scholar ]

- Machado-Allison CE. Historia de la entomología médica. Entomotropica. 2004; 19 :65–77. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beaver PC, Jung RC, Cupp EW. Clinical Parasitology. 9. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1984. [ Google Scholar ]

- Horwitz A. Epidemiology in Latin America. Bulletin of the Pan American Sanitary Bureau. 1961. p. LI. [ PubMed ]

- Morris J. Uses of Epidemiology. Edinburgh and London: E and S Livingstone Ltd; 1957. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tribute to Dr. Abraham Horwitz (1910–2000) Epidemiological Bulletin. 2000; 21 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Horwitz A. [The present health situation in the Americas] Revista de Sanidad y Asistencia Social. 1960; 25 :199–213. In Spanish. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clarke A, Gatineau M, Grimaud O, Royer-Devaux S, Wyn-Roberts N, Le Bis I, Lewison G. A bibliometric overview of public health research in Europe. European Journal of Public Health. 2007; 17 :43–49. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm063. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Londoño J, Székely M. Persistent poverty and excess inequality: Latin America. Journal of Applied Economics. 2003; 3 :93–134. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoffman K, Centeno M. The lopsided continent: inequality in Latin America. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003; 29 :363–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100141. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Belizán J, Cafferata M, Belizán M, Althabe F. Health inequality in Latin America. Lancet. 2007; 370 :1599–1600. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61673-0. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Progress and inequality in Latin America. Lancet. 2007; 370 :1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61664-X. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Almeida-Filho N, Kawachi I, Filho A, Dachs J. Research on health inequalities in Latin America and the Caribbean: bibliometric analysis (1971–2000) and descriptive content analysis (1971–1995) American Journal of Public Health. 2003; 93 :2037–2043. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Waitzkin H, Iriart C, Estrada A, Lamadrid S. Social medicine then and now: lessons from Latin America. American Journal of Public Health. 2001; 91 :1592–1601. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Waitzkin H. Is our work dangerous? Should it be? Journal of Health and Social Behaviour. 1998; 39 :7–17. doi: 10.2307/2676386. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Waitzkin H, Iriart C, Estrada A, Lamadrid S. Social medicine in Latin America: productivity and dangers facing the major national groups. Lancet. 2001; 358 :315–323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05488-5. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Falagas M, Michalopoulos A, Bliziotis I, Soteriades E. A bibliometric analysis by geographic area of published research in several biomedical fields, 1995–2003. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006; 175 :1389–1390. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060361. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Falagas M, Papastamataki P, Bliziotis I. A bibliometric analysis of research productivity in Parasitology by different world regions during a 9-year period (1995–2003) BMC Infectious Diseases. 2006; 6 :56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-56. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Falagas M, Karavasiou A, Bliziotis I. A bibliometric analysis of global trends of research productivity in tropical medicine. Acta Tropica. 2006; 99 :155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.07.011. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vergidis P, Karavasiou A, Paraschakis K, Bliziotis I, Falagas M. Bibliometric analysis of global trends for research productivity in microbiology. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2005; 24 :342–346. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-1306-x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bliziotis I, Paraschakis K, Vergidis P, Karavasiou A, Falagas M. Worldwide trends in quantity and quality of published articles in the field of infectious diseases. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2005; 5 :16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-16. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LILACS: Literatura Latinoamericana en Ciencias de la Salud http://bases.bireme.br/cgi-bin/wxislind.exe/iah/online/?IsisScript=iah/iah.xis&base=LILACS&lang=e

- Hermes Lima M, Alencastro A, Santos N, Navas C, Beleboni R. The relevance and recognition of Latin American science. Introduction to the fourth issue of CBP-Latin America. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Toxicology & Pharmacology. 2007; 146 :1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2007.05.005. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barreto ML, Barata R. Public health and epidemiology journals published in Brazil and other Portuguese speaking countries. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology. 2008; 5 :18. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-5-18. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Macías-Chapula CA. Hacia un modelo de comunicación en salud pública en América Latina y el Caribe. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 2005; 18 :427–438. doi: 10.1590/S1020-49892005001000006. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Virtual Health Library http://www.bireme.br/php/index.php?lang=en

- Biblioteca Virtual en Salud http://www.bvsalud.org/php/index.php?lang=es

- Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde http://www.bvsalud.org/php/index.php?lang=pt

- SciELO: Scientific Electronic Library Online http://www.scielo.org/php/index.php

- Latindex: Sistema regional de Información en Línea para Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal http://www.latindex.unam.mx/

- Imbiomed: Índice de Revistas Biomédicas Latinoamericanas http://www.imbiomed.com/

- Latin American Social Medicine http://hsc.unm.edu/lasm/

- e-revistas: Plataforma Open Access de revistas Científicas Electrónicas Españolas y Latinoamericanas http://www.erevistas.csic.es

- CLASE and PERIÓDICA http://www.oclc.org/support/documentation/firstsearch/databases/dbdetails/details/ClasePeriodica.htm

- REDALYC: La hemeroteca Científica en Línea http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/

- Medigraphic Literatura Biomédica http://www.medigraphic.com

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors http://www.icmje.org/

- World Association of Medical Editors http://www.wame.org/

- Black B. Indexing the names of authors from Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking countries. Science Editor. 2003; 26 :4. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ruiz-Pérez R, Delgado López-Cozar E, Jiménez-Contreras E. Spanish personal name variations in national and international biomedical databases: implications for information retrieval and bibliometric studies. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA. 2002; 90 :411–430. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ruiz-Pérez R, López-Cozar ED, Jiménez-Contreras E. Spanish name indexing errors in international databases. Lancet. 2003; 361 :1656–1657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13285-0. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Macías-Chapula CA, Mendoza-Guerrero JA, Rodea-Castro IP, Gutiérrez-Carrasco A. Construcción de una metodología para identificar investigadores mexicanos en bases de datos de ISI. Revista Española de Documentación Científica. 2006; 29 :220–238. doi: 10.3989/redc.2006.v29.i2.290. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pellegrini Filho A, Goldbaum M, Silvi J. Producción de artículos científicos sobre salud en seis países de América Latina, 1973 a 1992. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 1997; 1 :23–34. doi: 10.1590/S1020-49891997000100005. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barreto ML. The globalization of epidemiology: critical thoughts from Latin America. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2004; 33 :1132–1137. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh113. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Espejo E. Reflexiones acerca de un método para preservar a los pueblos de viruelas. Quito, Perú: Comisión Nacional Permanente de Conmemoraciones Cívicas; 1993. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reflexiones acerca de un método para preservar a los pueblos de viruelas http://www.conmemoracionescivicas.gov.ec/es/publicaciones/li_29viruela.html

- Astuto PL. Eugenio Espejo (1747 – 1795) Reformador ecuatoriano de la Ilustración. Quito, Perú: Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown TM, Fee E. Rudolf Carl Virchow: medical scientist, social reformer, role model. American Journal of Public Health. 2006; 96 :2104–2105. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.078436. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allende S. Medical and social reality in Chile. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005; 34 :732–736. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi083. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allende S. La Realidad Médico-Social Chilena. Santiago, Chile: Ministerio de Salubridad; 1939. [ Google Scholar ]

- Waitzkin H. Commentary: Salvador Allende and the birth of Latin American social medicine. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005; 34 :739–741. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh176. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muir R, Angell A. Commentary: Salvador Allende: his role in Chilean politics. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005; 34 :737–739. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh175. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yamada S. Latin American social medicine and global social medicine. American Journal of Public Health. 2003; 93 :1994–1996. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perel P, Casas JP, Ortiz Z, Miranda JJ. Noncommunicable diseases and injuries in Latin America and the Caribbean: time for action. PLoS Medicine. 2006; 3 :e344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030344. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yacoub S, Mocumbi A, Yacoub M. Neglected tropical cardiomyopathies: I. Chagas disease: myocardial disease. Heart. 2008; 94 :244–248. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.132316. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Casas JA, Dachs JNW, Bambas A. Equity and Health: Views from the Pan American Sanitary Bureau. Washington DC: PAHO;; 2001. Health disparities in Latin America and the Caribbean: The role of social and economic determinants; p. 169. [ Google Scholar ]

- SCImago Journal & Country Rank http://www.scimagojr.com/index.php

- Ospina EG, Reveiz Herault L, Cardona AF. Uso de bases de datos bibliográficas por investigadores biomédicos latinoamericanos hispanoparlantes: estudio transversal. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 2005; 17 :230–236. doi: 10.1590/S1020-49892005000400003. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 26 March 2024

Climate change impacts and adaptations of wine production

- Cornelis van Leeuwen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9428-0167 1 ,

- Giovanni Sgubin 2 , 3 ,

- Benjamin Bois ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7114-2071 4 ,

- Nathalie Ollat 1 ,

- Didier Swingedouw ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0583-0850 2 ,

- Sébastien Zito 1 &

- Gregory A. Gambetta ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8838-5050 1

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment ( 2024 ) Cite this article

6953 Accesses

1333 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Climate change

- Environmental impact

Climate change is affecting grape yield, composition and wine quality. As a result, the geography of wine production is changing. In this Review, we discuss the consequences of changing temperature, precipitation, humidity, radiation and CO 2 on global wine production and explore adaptation strategies. Current winegrowing regions are primarily located at mid-latitudes (California, USA; southern France; northern Spain and Italy; Barossa, Australia; Stellenbosch, South Africa; and Mendoza, Argentina, among others), where the climate is warm enough to allow grape ripening, but without excessive heat, and relatively dry to avoid strong disease pressure. About 90% of traditional wine regions in coastal and lowland regions of Spain, Italy, Greece and southern California could be at risk of disappearing by the end of the century because of excessive drought and more frequent heatwaves with climate change. Warmer temperatures might increase suitability for other regions (Washington State, Oregon, Tasmania, northern France) and are driving the emergence of new wine regions, like the southern United Kingdom. The degree of these changes in suitability strongly depends on the level of temperature rise. Existing producers can adapt to a certain level of warming by changing plant material (varieties and rootstocks), training systems and vineyard management. However, these adaptations might not be enough to maintain economically viable wine production in all areas. Future research should aim to assess the economic impact of climate change adaptation strategies applied at large scale.

Climate change modifies wine production conditions and requires adaptation from growers.

The suitability of current winegrowing areas is changing, and there will be winners and losers. New winegrowing regions will appear in previously unsuitable areas, including expanding into upslope regions and natural areas, raising issues for environmental preservation.

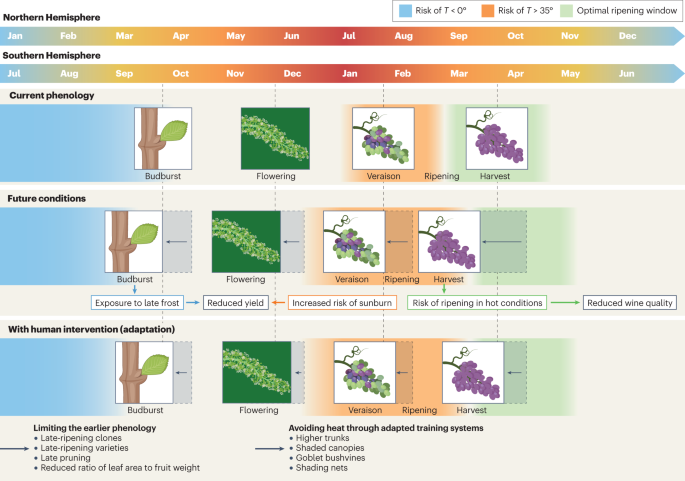

Higher temperatures advance phenology (major stages in the growing cycle), shifting grape ripening to a warmer part of the summer. In most winegrowing regions around the globe, grape harvests have advanced by 2–3 weeks over the past 40 years. The resulting modifications in grape composition at harvest change wine quality and style.

Changing plant material and cultivation techniques that retard maturity are effective adaptation strategies to higher temperatures until a certain level of warming.

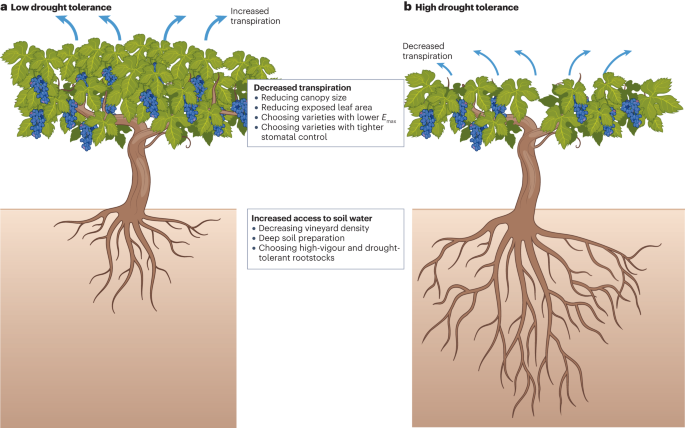

Increased drought reduces yield and can result in sustainability losses. The use of drought-resistant plant material and the adoption of different training systems are effective adaptation strategies to deal with declining water availability. Supplementary irrigation is also an option when sustainable freshwater resources are available.

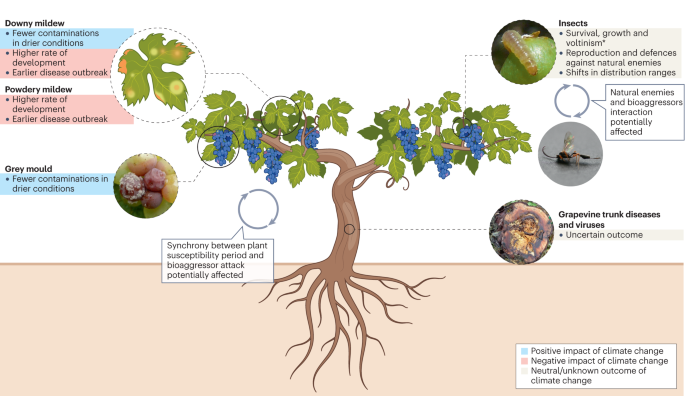

The emergence of new pests and diseases and the increasing occurrence of extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, heavy rainfall and possibly hail, also challenge wine production in some regions. In contrast, other areas might benefit from reduced pest and disease pressure.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Changes in Cabernet Sauvignon yield and berry quality as affected by variability in weather conditions in the last two decades in Lebanon

G. Ghantous, K. Popov, … Y. N. Sassine

Quantifying the grapevine xylem embolism resistance spectrum to identify varieties and regions at risk in a future dry climate

Laurent J. Lamarque, Chloé E. L. Delmas, … Sylvain Delzon

The fingerprints of climate warming on cereal crops phenology and adaptation options

Zartash Fatima, Mukhtar Ahmed, … Sajjad Hussain

Introduction

Grapes are the world’s third most valuable horticultural crop, after potatoes and tomatoes, counting for a farm-gate value of US$68 billion in 2016 ref. 1 . Global production in 2020 was 80 million tonnes of grapes, harvested from 7.4 million hectares 2 . Of the produced grapes, 49% were transformed into wine and spirits, while 43% were consumed as fresh grapes and 8% as raisins. Wine, as a commodity, can be valued over a price range from US$3 to over US$1,000 per bottle, depending on quality and reputation 3 . Hence, financial sustainability does not only rely on the balance between yield and production costs, as for most agricultural products, but also on quality and reputation. The region of production is a major driver of reputation and value 4 . This regional variation in wine quality is not surprising, because the climate, or more precisely the ‘right variety in the right climate’, is a well-identified attribute of premium wine production 3 . The effect of climate conditions on grape composition at harvest (and thus, wine composition and quality) seems to be even more important than the soil type 5 .

With climate change, this fundamental regional influence on wine quality and style is changing 6 . For example, a substantial advance in harvest dates and/or an increase in wine alcohol level have already been observed in many regions such as Bordeaux and Alsace (France) 7 , 8 , 9 . The suitability for wine production in established winegrowing regions is likely to change during the twenty-first century 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 . Pressures from temperature rise and drought could challenge production in already hot and dry regions to the point where suitability will be lost, with enormous negative social and economic consequences. Mid-latitude wine regions could be increasingly exposed to spring frost events, owing to earlier budburst 14 , 15 . Projected increased hailstorm severity can result in crop and plant damage 16 . However, some of these projections are overly pessimistic, because they do not take into account the possibility for growers to adapt to the changing conditions 17 . For example, major technical levers for adaptation include changes in plant material, training systems and/or seasonal management practices 18 , 19 , 20 .

In addition, new winegrowing regions could emerge in previously unsuitable areas, as cool and subhumid climates see increasing temperatures, creating economic opportunities but also threatening wild habitats when these emerging regions do not result from converted farmland 10 . If these new vineyards are irrigated, this will increase competition for freshwater resources. Even converting existing farmland to winegrowing means less arable land dedicated to food production.

In this Review, we synthesize climate change effects on viticulture and wine production. Many articles have been published on regional impacts of climate change on wine production, and our aim is to assemble these results to produce a global picture of the changing geography of wine. We discuss the impacts of changing temperature, radiation, water availability, pests and diseases, and CO 2 on viticulture and wine. Potential adaptation measures and their limits are discussed, for example, existing producers can adapt to a certain level of warming by changing plant material (varieties and rootstocks), training systems and vineyard management. However, these adaptations might not be enough to maintain economically viable wine production in all areas. Finally, implications of viticultural expansion are discussed and compared with historical shifts in production.

Shifting geographies of wine production

Wine grapes are cultivated from the tropics to Scandinavia 21 , 22 and can be grown at elevations of over 3,000 m 23 , revealing the remarkable adaptability of grapevine to a wide range of climate conditions. Vineyard management aims at locally adapting vine cultivation to match terrain, soil and climate conditions. In cool and subhumid environments, such as vineyards in northwestern Europe, important climate-related challenges are grapevine diseases and difficulties in obtaining fully mature fruit. Hence, vineyards are commonly planted on slopes to optimize light interception and runoff, on shallow soils to promote mild water deficits that enhance ripening, with early ripening grapevine cultivars, and using training systems that maximize exposed leaf areas per unit of ground surface 24 . In such regions, the impacts of climate change are predominantly positive, as warmer conditions and higher evaporative demand make it easier for grapes to ripen 25 and limit disease-triggering humidity. In drier and warmer regions, the main challenge is plant water availability. Adaptation to water scarcity depends on local practices, favouring either irrigation or systems that use low water consumption, such as cultivation of drought-resistant varieties cropped as bushvines and/or at low planting density (number of vines per hectare). In warm and dry regions, climate change is a threat requiring immediate adaptations because of excessively high temperatures 26 and increased water scarcity 27 .

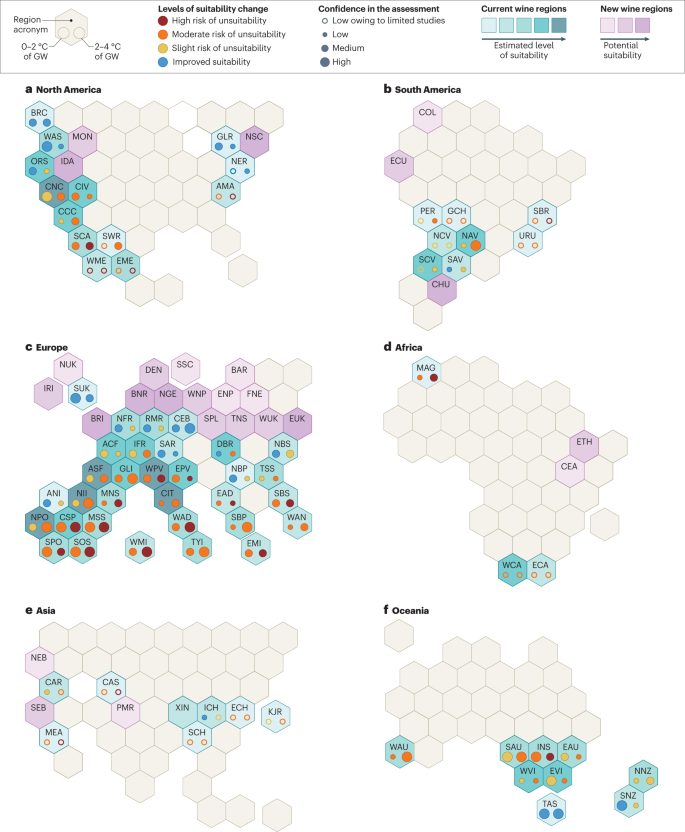

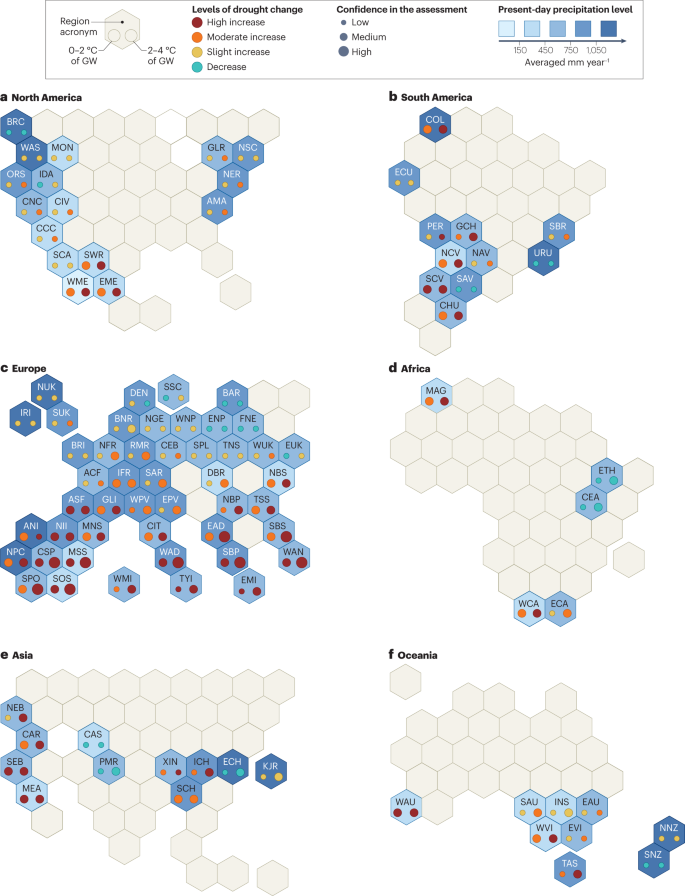

Climate change is having a growing impact on the wine industry, potentially altering the geography of high-quality wine production. After segmenting each continent and its wine-producing areas into macro-regions defined by specific climate-driven conditions (see Supplementary note and Supplementary Table 1 for definitions), we estimate a substantial risk of unsuitability (ranging from moderate to high) for 49–70% of existing wine regions, contingent on the degree of global warming (Fig. 1 ). Simultaneously, 11–25% of existing wine regions might experience enhanced production with rising temperatures, and new suitable areas might emerge at higher latitudes and altitudes (Fig. 1 ). These assessments on the future risks and opportunities for wine production worldwide are based on an exhaustive literature review (see Supplementary Table 2 ) and exhibit specific features across continents.

a – f , Current suitability across continental regions is noted by the green shading of the hexagons, from less suitable (light green) to more suitable (darker green), for North America (panel a ), South America (panel b ), Europe (panel c ), Africa (panel d ), Asia (panel e ) and Oceania (panel f ). This current suitability was based on the actual production area and on published studies (see Supplementary information ). Future suitability change in these regions is noted by the colour of the dots within the hexagons according to the key; the left dot represents the change for a scenario in which there is global warming (GW) of up to 2 °C and the right dot the change for warming of 2-4 °C. The size of the dot represents the confidence of the assessment (the larger the dot, the higher the confidence). The potential suitability of emerging wine regions is noted by hexagons that are shaded purple, from less (light purple) to more (darker purple) potential suitability based on consensus from the literature. The methodology to produce the maps is explained in the Supplementary information . The acronyms of all regions delimited by hexagons are provided in Supplementary Table 1 , and references used for the assessments are available in Supplementary Table 2 . Out of the 73 globally identified traditional wine-producing regions, an assessment on future climate suitability was feasible for 72: for global warming below (above) 2 °C, 18 (8) show improved suitability, 19 (13) show a slight risk of suitability loss, 34 (30) a moderate risk of suitability loss and 1 (21) a high risk of suitability loss. Simultaneously, 26 new potential emerging wine regions have been identified.

North America

Currently, most of the wine production in North America (10% of global wine production 2 ) is concentrated on the west coast 28 , particularly in northern California, including Napa Valley, which stands out both in terms of production and value (Fig. 1a ). Moderate levels of global warming are projected to maintain the suitability of coastal regions of California for high-quality wine production 10 , 29 . However, winemakers in this region will face increasing risks of drought, heatwaves and wildfires, necessitating the proactive adoption of adaptation measures 30 . If global warming exceeds 2 °C, coastal California will transition to a very warm and arid climate for viticulture, probably resulting in a decline in wine quality and economic sustainability 12 , 26 . The interior regions of California might experience this decline earlier and will need to adopt more radical adaptation measures even below 2 °C of global warming 31 . The southern part of California, already characterized by a warm and dry climate, is expected to become unsuitable for high-quality wine production under global warming scenarios exceeding 2 °C 10 , 12 . Overall, the net suitable area for wine production in California could decline by up to 50% by the end of the twenty-first century 12 . Similar risks exist for Mexico, the southwestern United States and those regions of the east coast south of New Jersey 10 . The northernmost wine regions of America (that is, New British Columbia, Washington State, Oregon on the west coast, Great Lakes region and New England on the east coast) are likely to shift from cool to intermediate, or even warm, climate viticulture in the future, thus increasing their potential for premium wine production 10 , 12 , 29 , 32 . However, global warming surpassing 2 °C is likely to result in antagonistic effects. On one hand, it can enhance climate suitability, with suitable areas in these regions (excluding Oregon) probably more than doubling 10 , 12 . On the other hand, it would introduce unprecedented risks of heatwaves and increased disease pressure 26 , 33 , particularly considering that these regions are predominantly classified as humid.

South America

Current wine production in South America (10% of global wine production 2 ) is primarily concentrated in the middle to high altitudes of Chile and Argentina, benefiting from favourable temperatures and sunlight along the foothills of the Andes Mountains (Fig. 1b ). Given the extensive irrigation already adopted over the driest wine regions, such as Mendoza, projections in precipitation over traditional South American vineyards do not indicate substantial changes in suitability 34 . Consequently, the future suitability in these regions will be primarily dependent on temperature increase, ground and surface water availability 35 , and the frequency of extreme events. For a limited level of warming, the Pacific sector of South America is expected to experience a low risk of suitability loss, but this risk increases for the Atlantic regions such as Brazil and Uruguay. Cool-climate winegrowing regions, such as the Pampa region, might be improved under these conditions 34 , 36 . For more severe warming, the resilience of the northern Argentinian wine regions might require a shift from lowlands to higher slopes of the Andes 34 , 36 , while the Atlantic sector will offer poor opportunities for winemaking 10 , 12 . Expanding into newly suitable areas could imply movement southward into Argentinian Patagonia 34 , 36 or potentially an exploration of the high altitudes of the Ecuadorian and Colombian Andes 10 , 12 . In general, the projected decrease in suitable areas in the Pacific South America will probably be balanced by the potential emergence of new suitable areas 10 , 12 .

Europe is recognized as the primary producer of premium wine worldwide, with a substantial production located south of approximately 50° N. Spain, France, Italy and Germany collectively contribute to half of global wine production 2 (Fig. 1c ). However, climate change is expected to shift suitable regions towards higher latitudes and altitudes 10 , 12 . Under low levels of global warming (<2 °C), most traditional wine-producing regions will maintain suitability, albeit contingent on the implementation of adaptation measures, notably in southern Europe 13 . The combination of rising temperatures and reduced rainfall will induce severe risk of drought over south Iberia, Mediterranean France and Spain, the Po Valley, coastal Italy, the Balkan Peninsula and the southwestern Black Sea regions 13 , 27 , 37 , 38 . The risk of widespread water scarcity might render unsustainable any extensive increase in irrigation intended to preserve the suitability of these areas. Moreover, warmer conditions and increased sunburn exposure will negatively affect both yield and wine quality in these areas. For more severe warming scenarios, most Mediterranean regions might become climatically unsuitable for wine production, and vineyards below 45° N might be so challenged that the only feasible adaptation would be to relocate to higher altitudes 11 , 13 , 39 , 40 , 41 . About 90% of the traditional wine regions situated in the lowlands and coastal regions of Spain, Italy and Greece could be at risk of disappearing by the end of the century 12 . Only a minor portion of this loss (less than 20%) can be potentially compensated for by shifting vineyards towards mountainous areas, considering elevations of up to 1,000 m 11 , 42 .

Atlantic sectors of Iberia and France, along with the western Black Sea regions, will face lower risks than the Mediterranean 13 , 43 , 44 , 45 . With limited global warming, the implementation of viticultural techniques that delay ripening and alleviate water stress seem sufficient to preserve high-quality wine production 46 . More severe warming scenarios are likely to necessitate the transition to later-ripening grape varieties in these regions 12 , 13 . Conversely, Galicia, the northern Balkans, and in general areas north of 46° N are expected to benefit from global warming, at least for limited levels of temperature increase 10 , 13 , 27 . Over certain regions, early budburst might lead to an increased risk from spring frost 14 , 18 , 47 . Overall, the suitable surface area of traditional wine-producing regions is expected to decline by 20–70% by the end of the century, depending on the severity of the warming scenario 13 . Simultaneously, new wine regions are expected to expand northward, notably along the Atlantic sector 10 , 11 , 12 , 14 , 27 , resulting in a net increase of climatically suitable areas in Europe by up to 60% 13 . However, such an expansion is purely theoretical and pertains solely to climate conditions, without considering soil quality, pre-existing land use and other crucial factors for establishing new vineyards.