Join thousands of product people at Insight Out Conf on April 11. Register free.

Insights hub solutions

Analyze data

Uncover deep customer insights with fast, powerful features, store insights, curate and manage insights in one searchable platform, scale research, unlock the potential of customer insights at enterprise scale.

Featured reads

Tips and tricks

Four ways Dovetail helps Product Managers master continuous product discovery

Product updates

Dovetail retro: our biggest releases from the past year

How to affinity map using the canvas

Events and videos

© Dovetail Research Pty. Ltd.

What is phenomenology in qualitative research?

Last updated

7 February 2023

Reviewed by

Take a closer look at this type of qualitative research along with characteristics, examples, uses, and potential disadvantages.

Analyze your phenomenological research

Use purpose-built tools to surface insights faster

- What is phenomenological qualitative research?

Phenomenological research is a qualitative research approach that builds on the assumption that the universal essence of anything ultimately depends on how its audience experiences it .

Phenomenological researchers record and analyze the beliefs, feelings, and perceptions of the audience they’re looking to study in relation to the thing being studied. Only the audience’s views matter—the people who have experienced the phenomenon. The researcher’s personal assumptions and perceptions about the phenomenon should be irrelevant.

Phenomenology is a type of qualitative research as it requires an in-depth understanding of the audience’s thoughts and perceptions of the phenomenon you’re researching. It goes deep rather than broad, unlike quantitative research . Finding the lived experience of the phenomenon in question depends on your interpretation and analysis.

- What is the purpose of phenomenological research?

The primary aim of phenomenological research is to gain insight into the experiences and feelings of a specific audience in relation to the phenomenon you’re studying. These narratives are the reality in the audience’s eyes. They allow you to draw conclusions about the phenomenon that may add to or even contradict what you thought you knew about it from an internal perspective.

- How is phenomenology research design used?

Phenomenological research design is especially useful for topics in which the researcher needs to go deep into the audience’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

It’s a valuable tool to gain audience insights, generate awareness about the item being studied, and develop new theories about audience experience in a specific, controlled situation.

- Examples of phenomenological research

Phenomenological research is common in sociology, where researchers aim to better understand the audiences they study.

An example would be a study of the thoughts and experiences of family members waiting for a loved one who is undergoing major surgery. This could provide insights into the nature of the event from the broader family perspective.

However, phenomenological research is also common and beneficial in business situations. For example, the technique is commonly used in branding research. Here, audience perceptions of the brand matter more than the business’s perception of itself.

In branding-related market research, researchers look at how the audience experiences the brand and its products to gain insights into how they feel about them. The resulting information can be used to adjust messaging and business strategy to evoke more positive or stronger feelings about the brand in the future.

- The 4 characteristics of phenomenological research design

The exact nature of phenomenological research depends on the subject to be studied. However, every research design should include the following four main tenets to ensure insightful and actionable outcomes:

A focus on the audience’s interpretation of something . The focus is always on what an experience or event means to a strictly defined audience and how they interpret its meaning.

A lack of researcher bias or prior influence . The researcher has to set aside all prior prejudices and assumptions. They should focus only on how the audience interprets and experiences the event.

Connecting objectivity with lived experiences . Researchers need to describe their observations of how the audience experienced the event as well as how the audience interpreted their experience themselves.

- Types of phenomenological research design

Each type of phenomenological research shares the characteristics described above. Social scientists distinguish the following three types:

Existential phenomenology —focuses on understanding the audience’s experiences through their perspective.

Hermeneutic phenomenology —focuses on creating meaning from experiences through the audience’s perspective.

Transcendental phenomenology —focuses on how the phenomenon appears in one consciousness on a broader, scientific scale.

Existential phenomenology is the most common type used in a business context. It’s most valuable to help you better understand your audience.

You can use hermeneutic phenomenology to gain a deeper understanding of how your audience perceives experiences related to your business.

Transcendental phenomenology is largely reserved for non-business scientific applications.

- Data collection methods in phenomenological research

Phenomenological research draws from many of the most common qualitative research techniques to understand the audience’s perspective.

Here are some of the most common tools to collect data in this type of research study:

Observing participants as they experience the phenomenon

Interviewing participants before, during, and after the experience

Focus groups where participants experience the phenomenon and discuss it afterward

Recording conversations between participants related to the phenomenon

Analyzing personal texts and observations from participants related to the phenomenon

You might not use these methods in isolation. Most phenomenological research includes multiple data collection methods. This ensures enough overlap to draw satisfactory conclusions from the audience and the phenomenon studied.

Get started collecting, analyzing, and understanding qualitative data with help from quickstart research templates.

- Limitations of phenomenological research

Phenomenological research can be beneficial for many reasons, but its downsides are just as important to discuss.

This type of research is not a solve-all tool to gain audience insights. You should keep the following limitations in mind before you design your research study and during the design process:

These audience studies are typically very small. This results in a small data set that can make it difficult for you to draw complete conclusions about the phenomenon.

Researcher bias is difficult to avoid, even if you try to remove your own experiences and prejudices from the equation. Bias can contaminate the entire outcome.

Phenomenology relies on audience experiences, so its accuracy depends entirely on how well the audience can express those experiences and feelings.

The results of a phenomenological study can be difficult to summarize and present due to its qualitative nature. Conclusions typically need to include qualifiers and cautions.

This type of study can be time-consuming. Interpreting the data can take days and weeks.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 September 2023

Last updated: 14 February 2024

Last updated: 17 February 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2024

Last updated: 30 January 2024

Last updated: 12 October 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 31 January 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Qualitative study design: Phenomenology

- Qualitative study design

Phenomenology

- Grounded theory

- Ethnography

- Narrative inquiry

- Action research

- Case Studies

- Field research

- Focus groups

- Observation

- Surveys & questionnaires

- Study Designs Home

Used to describe the lived experience of individuals.

- Now called Descriptive Phenomenology, this study design is one of the most commonly used methodologies in qualitative research within the social and health sciences.

- Used to describe how human beings experience a certain phenomenon. The researcher asks, “What is this experience like?’, ‘What does this experience mean?’ or ‘How does this ‘lived experience’ present itself to the participant?’

- Attempts to set aside biases and preconceived assumptions about human experiences, feelings, and responses to a particular situation.

- Experience may involve perception, thought, memory, imagination, and emotion or feeling.

- Usually (but not always) involves a small sample of participants (approx. 10-15).

- Analysis includes an attempt to identify themes or, if possible, make generalizations in relation to how a particular phenomenon is perceived or experienced.

Methods used include:

- participant observation

- in-depth interviews with open-ended questions

- conversations and focus workshops.

Researchers may also examine written records of experiences such as diaries, journals, art, poetry and music.

Descriptive phenomenology is a powerful way to understand subjective experience and to gain insights around people’s actions and motivations, cutting through long-held assumptions and challenging conventional wisdom. It may contribute to the development of new theories, changes in policies, or changes in responses.

Limitations

- Does not suit all health research questions. For example, an evaluation of a health service may be better carried out by means of a descriptive qualitative design, where highly structured questions aim to garner participant’s views, rather than their lived experience.

- Participants may not be able to express themselves articulately enough due to language barriers, cognition, age, or other factors.

- Gathering data and data analysis may be time consuming and laborious.

- Results require interpretation without researcher bias.

- Does not produce easily generalisable data.

Example questions

- How do cancer patients cope with a terminal diagnosis?

- What is it like to survive a plane crash?

- What are the experiences of long-term carers of family members with a serious illness or disability?

- What is it like to be trapped in a natural disaster, such as a flood or earthquake?

Example studies

- The patient-body relationship and the "lived experience" of a facial burn injury: a phenomenological inquiry of early psychosocial adjustment . Individual interviews were carried out for this study.

- The use of group descriptive phenomenology within a mixed methods study to understand the experience of music therapy for women with breast cancer . Example of a study in which focus group interviews were carried out.

- Understanding the experience of midlife women taking part in a work-life balance career coaching programme: An interpretative phenomenological analysis . Example of a study using action research.

- Holloway, I. & Galvin, K. (2017). Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare (Fourth ed.): John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Rodriguez, A., & Smith, J. (2018). Phenomenology as a healthcare research method . Journal of Evidence Based Nursing , 21(4), 96-98. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102990

- << Previous: Methodologies

- Next: Grounded theory >>

- Last Updated: Mar 19, 2024 9:32 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/qualitative-study-designs

Qualitative Research Methods

- Gumberg Library and CIQR

- Qualitative Methods Overview

Phenomenology

- Case Studies

- Grounded Theory

- Narrative Inquiry

- Oral History

- Feminist Approaches

- Action Research

- Finding Books

- Getting Help

Phenomenology helps us to understand the meaning of people's lived experience. A phenomenological study explores what people experienced and focuses on their experience of a phenomenon. As phenomenology has a strong foundation in philosophy, it is recommended that you explore the writings of key thinkers such as Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty before embarking on your research. Duquesne's Simon Silverman Phenomenology Center maintains a collection of resources connected to phenomenology as well as hosting lectures, and is a good place to start your exploration.

- Simon Silverman Phenomenology Center

- Husserl, Edmund, 1859–1938

- Heidegger, Martin, 1889–1976

- Sartre, Jean Paul, 1905–1980

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, 1908–1961

Books and eBooks

Online Resources

- Phenomenology Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry.

- << Previous: Qualitative Methods Overview

- Next: Case Studies >>

- Last Updated: Aug 18, 2023 11:56 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duq.edu/qualitative_research

- Open access

- Published: 13 March 2024

Sexuality and self-concept of morbidly obese women who are sexually attracted to men after bariatric surgery: a phenomenological study

- José Granero-Molina 1 , 2 ,

- María del Mar Jiménez-Lasserrotte 1 ,

- Cristina Arias Hoyos 3 ,

- María José Torrente Sánchez 4 ,

- Cayetano Fernández-Sola 1 &

- María Dolores Ruiz-Fernández 1

BMC Women's Health volume 24 , Article number: 174 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

154 Accesses

Metrics details

Morbid Obesity (MO) is a public health problem that affects a person’s physical, psychological and sexual well-being. Women with MO are affected by their body image and self-concept, and obesity stigma may affect women in social and sexual relationships.

To describe and understand the experiences of morbidly obese heterosexual women (who are sexually attracted to men) in relation to their body image and sexuality after bariatric surgery.

Methodology

Qualitative study using Merleau-Ponty’s hermeneutic phenomenology as a philosophical framework. Data collection took place between 2020 and 2021 in a southern Spanish province. A total of 22 in-depth interviews were conducted using open-ended questions until data saturation was reached.

Two main themes were identified: (1) “Escaping from a cruel environment”: weight loss to increase self-esteem; with the sub-themes: ‘I love myself now’, and ‘Body image and social relationships; a vicious circle; (2) “Now, I am truly me”: accepting my body to reclaim my sexuality, with the sub-themes: ‘The body as the focal point of sexuality’, and ‘When regaining your sex drive reignites your sex life and relationship’.

Weight loss and body acceptance radically change morbidly obese women’s sex lives after bariatric surgery. They rediscover their bodies, have increased self-esteem, and see improvements in their social relationships and sexuality. These women feel seen, loved and desired, and now value their body image and femininity. As they go through continuous improvements following bariatric surgery, they gradually regain self-esteem, acceptance of their bodies and control over their sex life. Even though the women’s partners benefit from these improvements, they seem to be afraid of being left.

Plain English Summary

Obesity is a problem that affects women’s physical, psychological and sexual well-being, as well as their social relationships. It is important to explore and understand the experiences of heterosexual women regarding their body and sexuality. After other treatments, women undergo surgery to reduce their obesity. After bariatric surgery women feel happier about themselves, experience less stigma and progressively recover their social and sex lives.

Peer Review reports

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines being overweight as having a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2, and obesity as a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 [ 1 ]. Morbid obesity (MO) is a serious health condition as it means having a BMI greater than 40 kg/m², combined with at least one serious obesity-related condition [ 2 , 3 ]. MO is considered a public health challenge [ 4 ]; almost 40% of adults worldwide are overweight and almost 15% are obese [ 1 , 5 ]. In Spain, 15.5% of women aged ≥ 18 years are obese [ 6 ]. MO is a precursor of high mortality [ 7 ], associated with comorbidities such as cardio-vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cancer, osteoarthritis, pelvic floor dysfunction or urinary incontinence [ 8 , 9 ]. MO is also associated with psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, low self-esteem and disorders related to self-perception and body image [ 10 ]. This is compounded by social problems such as weight-related discrimination, sexual dysfunction and social stigma [ 11 ].

MO is associated with female sexual dysfunction (FSD), which is characterised by hypoactive sexual desire disorder, sexual aversion disorder, sexual arousal disorder, orgasmic disorder and sexual pain disorders [ 12 ]. This is in addition to disorders affecting libido, pleasure, reproduction [ 13 , 14 ], intimacy, affection and self-care [ 15 ]. People with MO are affected in terms of self-perception and are dissatisfied with their body image, this is associated with worse mental and sexual health [ 7 , 16 ]. Women with MO experience depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, limited acceptance of their body image and difficulty in interpersonal relationships. Negative correlations have been found between BMI, sex drive and the ability to experience orgasm [ 17 ]. Female sexuality is related to quality of life and body image, and a woman’s perception of her own body is associated with sexual satisfaction [ 18 , 19 ]. Negative body image is linked to lower sexual activity, less satisfaction, poor communication and seeking professional help [ 20 ]. Women are a more vulnerable group because of society’s idealisation of their bodies.

The treatment of MO focuses on nutrition, physical exercise, lifestyle habits and surgical treatment. Bariatric surgery is an effective therapeutic measure for treatment of MO and its comorbidities, as it improves diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia and hypertension [ 11 ], as well as quality of life, sex hormones, fertility and sexual function [ 5 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 20 ]. Body perception and sex life are key factors in the decision to undergo bariatric surgery. Reviews suggest improved sexual function in women with MO after surgery [ 21 ], and almost half of patients dissatisfied with their sex life experienced improvements after surgery at their 5-year follow-up [ 22 ]. Body image also improved after bariatric surgery, although this is not always maintained over time [ 23 ]. Body image plays a relevant role in psychological disorders after bariatric surgery and is a key factor in the assessment and treatment of patients with MO [ 24 ]. Much of the motivation for people to opt for bariatric surgery is due to dissatisfaction with their appearance and body image [ 25 ]. The women’s motives for undergoing bariatric surgery stem from a desire to improve their fertility [ 26 ], as well as the expectation of better physical health, stronger personal identity, and improved social relationships; they consider surgery to be their last option [ 27 ]. Studies such as that of Mento et al. [ 28 ] recommend further research on self-concept and body image before and after bariatric surgery. In addition to epidemiological, nutritional, diagnostic or therapeutic studies, there is a need to understand morbidly obese heterosexual women’s experiences regarding their body image and sexuality after bariatric surgery [ 19 , 29 ]. While the relationship between body image and sexual function has been examined in epidemiological or intervention studies, qualitative studies where women describe their own experiences are scarce [ 19 ]. Some studies have explored men’s and women’s experiences of MO prior to bariatric surgery [ 29 , 30 ], but such experiences after surgery remain to be studied. Understanding these experiences could better prepare women for the life changes that follow bariatric surgery [ 31 ]. The aim of our study is to describe and understand the experiences of morbidly obese heterosexual women regarding their body image and sexuality after bariatric surgery.

Research design

This is a qualitative study that used Merleau-Ponty’s hermeneutic phenomenology as a framework. According to Merleau-Ponty, we perceive the world through our body [ 32 ], human consciousness is linked to corporeality, and the notion of ‘self’ is inextricably linked to our body and experiences. The participants live their experiences according to a body schema; we seek to understand the complexity of the phenomenon of sexuality, self-perception and body image in the different ways in which women with MO embody it. Merleau-Ponty advocates phenomenological reduction to capture experiences and the lifeworld (Lebenswelt) covering four existentials: lived space, lived body, lived time and lived relationships. In writing the manuscript, the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research were applied (COREQ) [ 33 ].

Participants and recruitment

The participants were selected through purposive sampling. A total of 22 women diagnosed with MO were recruited. The study took place in southern Spain between 2021 and 2022. Inclusion criteria: to be a heterosexual woman, aged 18 to 60 years, included in the Bariatric Surgery Programme, to have undergone surgery 2 or more years ago, to speak Spanish and to give informed consent. Exclusion criteria: a recent pregnancy, currently breastfeeding, going through menopause, previous bariatric surgery or refusal to participate in the study. The sociodemo-graphic characteristics of the participants are listed in Table 1 .

Data collection

After obtaining permission, the researchers contacted the participants. The researchers knew the patients because they monitor them for up to 5 years post-intervention. Of thirty-four women with MO contacted, four did not answer the phone and eight refused to participate. In-depth interviews were conducted in which open-ended questions allowed for the women’s narratives to be told. Interviews, with an average duration of 52 min, took place in a room at the Department of Nursing, Physiotherapy and Medicine at the University of …., between November 2021 and April 2022. The interviews were conducted in Spanish by two researchers (M.J.T.S., C.A.H.) with more than 8 years of experience in bariatric surgery, which allowed for in-depth data collection. Before starting, the participants were given an explanation of the aim and ethical issues of the study, sociodemographic data were collected and informed consent was obtained. The interview began with an open-ended question: ‘What does the topic of sexuality after bariatric surgery suggest to you?’ The participants shared their experiences, and the interviewers took notes of verbal and non-verbal elements of communication. The interview ended with the question: ‘Do you have anything else to add?’ The researchers’ interpretations and reflections were continuously edited during the data analysis process. Data collection was stopped when data saturation was reached. Focus groups were ruled out as the participants refused to discuss their sexuality with other women.

Data analysis

All annotations and in-depth interviews were transcribed and incorporated into a hermeneutic unit of the ATLAS programme. Ti 9.0. The analysis process was organised in three steps according to Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology [ 34 ]: (1) Description: interviews were transcribed verbatim, transcripts were read and then re-read to understand the experiences of the participants. (2) Phenomenological reduction: a process of coding the transcripts without incorporating standpoints, concepts, memories or personal experiences of the researchers. (3) Phenomenological interpretation: the researchers develop themes and sub-themes drawn from the inductive data analysis to understand the study phenomenon. Analysis was conducted by the researchers who did not know the participants. Discrepancies in the analysis were discussed with the other mem-bers of the research team until a consensus was reached.

To ensure rigour, quality criteria were followed [ 35 ]. (1) Credibility: all phases of data collection are detailed, data interpretation followed a descriptive process verified by independent researchers (surgeon and nurse, bariatric surgery). (2) Transferability: exhaustive description of setting, participants, context and method. (3) Dependability: an expert not involved in data collection and analysis examined the results. (4) Confirmability: all researchers read the transcripts and agreed on the units of meaning, themes and subthemes.

Ethical considerations

Permission was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the Department of Nursing, Physiotherapy and Medicine of the University of Almeria (EFM/45/2018). The study complies with the requirements and ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants provided informed consent upon commencing the study.

A total of 22 women with MO who underwent bariatric surgery 2 or > years ago were interviewed. The mean age was 42.7 years, SD = 9.7. MO started during childhood for 40.9% of the participants, during adolescence for 27.3%, after getting married for 13.65%, and after pregnancy for 18.2%. The mean BMI was 39.1625 kg/m2 before surgery and 28.08 25 kg/m2 two or more years after bariatric surgery. 59.2% of the women were married, 31.8% were single, 4.5% were unmarried and 4.5% were living with a partner. Two main themes were extracted from the inductive data analysis: (1) “Escaping a cruel environment”: weight loss to increase self-esteem; and (2) “Now, I am truly me”: accepting my body to reclaim my sexuality (see Table 2 ).

“Escaping a cruel environment”: weight loss to increase self-esteem

The lives of women with MO change dramatically before and after undergoing bariatric surgery. A key aspect is increased self-esteem, which is linked to improved self-perception and social relationships. Two subthemes emerged.

I love myself now

The participants highlighted two fundamental factors in their decision to undergo bariatric surgery: a feeling of self-consciousness brought about by not being comfortable with their own body, and an awareness of the deterioration of their health and quality of life due to MO. This is compounded by the aggravation of associated conditions, such as thyroid disease and difficulties in getting pregnant.

I had surgery because I had a lot of complexes, because I had thyroid problems that were getting worse, and because I wanted to be a mother and I couldn’t because of my MO. ” (IDI1).

One of the most significant changes in women after bariatric surgery is the improvement in their self-esteem. The participants recognised that, prior to surgery, their attitude towards life was very negative; it affected the way they dressed, communication, leisure activities, establishing relationships and dating. Surgery changes their body physically and mentally, which gives them more confidence in decision-making.

I have learned to say yes to what I used to say no to. What does the operation change for you? Confidence, physique, will to live and health, … they’re all very important.” (IDI4).

Prior to surgery the participants rejected their own bodies; they did not look at themselves in the mirror because they did not like what they saw. They did not care about their appearance and neglected their sense of femininity. They did not find themselves attractive and did nothing to make others find them attractive either. One of the participants described her situation as follows:

I saw this shapeless thing, an amorphous, ugly, very fat body with cellulite. I was disgusted to look at myself.” (IDI5).

Surgery has many positive consequences. As one participant stated, she started to pay more attention to her physical appearance after the operation because she felt good about herself and her body. Likewise, the participants have better social and romantic relationships, and experience improvements in their overall quality of life. Now that they see a future that MO was hiding, they want to take care of their body and their appearance because it is an essential element of their new life.

I like to get dressed up a lot more than I used to, …you feel prettier and better. ” (IDI2).

Another factor that helps them is the positive feedback from the people around them. According to the participants, since undergoing surgery, they get positive comments from others, which reaffirms their self-esteem and desire to improve every day.

It motivates you, it makes you want to get dolled up. They say, “My goodness, look at you today!” That makes you feel motivated, not because you’re sexually interested in the men but because they’re looking at you, they’re telling you you’re beautiful…. tomorrow I’ll be even more beautiful!” (IDI6).

Body image and social relationships: a vicious circle

Social relationships are a fundamental aspect of people’s lives; the participants defined theirs as negative prior to bariatric surgery. At this stage, it is very difficult for them to relate to others, they lose their self-confidence, and insecurity isolates them socially.

I used to be very withdrawn, I seemed to dislike everyone, I didn’t talk much, and, of course, you lose touch with people … You lose your self-confidence and, when you regain it and feel good, you also feel good around other people. ” (IDI7).

The participants said that contacting and interacting with people or social groups made them feel rejected, so they made excuses not to meet up with them. They felt ashamed and knew that they were the centre of attention and did not want to be. The participants have experienced stigma related to their MO, such as unpleasant jokes and mockery due to their physique. They have felt the accusatory gaze of a society that blames them for having become morbidly obese from not taking care of their health. Weight-related stigma isolated them and kept them stuck at home.

I always made excuses, …that I didn’t feel like going, that I was tired, that I had a headache…a thousand excuses not to go.” (IDI3).

Bariatric surgery has had a very positive effect on their willingness to interact with others. Improved self-image leads to improved self-esteem, which has a positive impact on recovering their social relationships:

Now I feel more confident, I’m not ashamed to speak. When you are fat you are ashamed to talk, you think the others think: “look at what this fat woman is saying.” (IDI4).

The women expressed how after surgery they wanted to take up activities that they had given up, such as physical exercise, outdoor activities and other hobbies. They have recovered their social relationships through spending time with friends, family or at patient associations.

Now I feel like talking, being with people I know, meeting new people … I feel like going out more, having a coffee. When I was fat this didn’t happen, I feel like a new person and yes, …. I want to say it, I want you to see it!” (IDI8).

Society’s cruelty is a factor that has caused them to have negative attitudes towards others. Most of the participants have had negative experiences due to comments about their body image or being made to feel uncomfortable. Society seems to deny them the right to be attractive to others and to be able to choose a partner. The women still have painful memories of these experiences, but they no longer suffer.

They told me: “as you’re fat, you can’t expect to find the partner you want… you have to settle for whatever comes along, even if it’s not someone you really like”. All that … it’s all nonsense, but it gets stuck in your head and it wears you down.” (IDI14).

The participants say that after surgery and weight loss, everything changes. They now receive compliments and positive comments from most people. This helps them to open up and relate to others. This is how one participant put it:

They start by looking at you, then they say: “how beautiful, I don’t know what you’ve done to yourself…”. And maybe one of them is saying something to you and another one comes along and says: “it’s true, she’s very pretty”. It puts a smile on your face.” (IDI20).

The women reaffirmed that bariatric surgery has radically changed their lives. They have higher self-esteem and confidence because of a transformation in their relationships and sexuality. The women with partners feel that they can respond to their partners’ sexual needs, that their husbands look at them lustfully, and they are proud of that.

Yes, my husband now suggests going out for dinner, dancing, sexy clothes … everything has changed. I always used to be hidden, in the background… I didn’t want him to see me naked.” (1DI16).

But despite improvements after bariatric surgery, the stigma of obesity does not disappear completely, and is still present. The women continue to receive negative comments after having undergone successful surgery. They recognise that it no longer affects them as much, but they feel the social stigma. The notion of an ideal body shape continues to influence their social and intimate relationships. As one participant said, she gets negative comments from those around her even after having lost weight. It is as if society does not accept the change and expects her to become morbidly obese again in the near future.

Some people say: “keep your clothes, you’ll need them” and those words stick in your head, they are cruel, they hurt you deeply …. Puff.” (IDI12).

“Now, I am truly me”: accepting my body to reclaim my sexuality

Improvements in body self-perception and increased self-esteem directly influence the sexuality of women who undergo bariatric surgery. Two subthemes were developed from the data analysis.

The body as the focal point of sexuality

The participants reported that the operation was a turning point in their sexual relations. Prior to bariatric surgery, the women with MO had serious mobility impairments, and symptoms of asphyxia, dyspnoea, tiredness and excessive sweating. This caused discomfort for them and their partners during sexual intercourse. After bariatric surgery, the women saw improvements in their sex life and relationships. They broke the monotony of always having sex in the same position, in the same places and under the same circumstances. This is what one woman said:

“Before, you couldn’t move, you just went along with it, you weren’t active …. Now you are active, you can move, you feel good and you work out what you like. You get on top, on the bottom, on the side…” (IDI16). “Before, sex could only be in bed. Now we change positions, places … everything. What my husband likes the most is for me to get on top of him, … that was unthinkable before. Now I can, I can get on top, I can enjoy it !” (IDI21).

Most of the participants acknowledged that before the surgery they avoided sexual intercourse because they were ashamed of exposing their bodies and being touched. They all agreed that having sex with the light on was impossible, but this was no longer the case after the operation. In addition, they also claimed that their partners have noticed this positive change.

Before, I didn’t like to be touched, … I was ashamed. Now I like him to touch me, to caress me, for it to last for a long time, everything is different, and he tells me so.” (IDI1). “You feel much better (ha, ha … you don’t mind if the light is on), whether it’s in the evening or in the morning … Before it had to be at night, with the light off. Why? Because of my body weight, because I looked horrible, … he also saw it even though he didn’t tell me so.” (IDI2).

After bariatric surgery, the participants stated that they no longer felt ashamed to be naked in front of their partners. Many of them agreed that even the skin that is visible due to weight loss does not bother them during sexual intercourse.

“Before, I didn’t undress in front of my husband, now I look forward to being naked, I want my partner to be excited by my body, ….” (IDI15). “The skin flaps are visible, I don’t like it, it’s a memory of what I was, …but they’re obvious, it’s as if you don’t see them. ” (IDI12).

Before the intervention, the women did not care about other aspects such as clothing or lingerie, which they struggled to find in their size; this is no longer a concern for them. Their body image is crucial to them now as it helps them to increase their sex drive and have sexual relations.

“I didn’t buy clothes before. I never went to the shops, my mother would bring me clothes and tell me what looked good on me, … and that was it. Now, since I had the operation, I have started to lose weight and the dressing room seems too small” (IDI18). “I can wear lingerie now, I go to the shops now. I look around, I can choose things for myself. I want to buy things because I’m going to wear them, they fit me well. I’ll wear this tonight, then I’m going to take a shower and wait for him (partner) in the bedroom…. I’m doing a lot of things I’ve never done before.” (IDI14).

When regaining your sex drive reignites your sex life and relationship

The participants confessed that their sex drive was very low before the operation, blaming their lack of confidence and self-esteem. Even in an intimate setting with their partners, they did not feel comfortable revealing their bodies. Their partners accepted them and wanted sex, but the women had no sex drive; the thought of having sex was repulsive to them.

That idea is in your head… Even if your partner is telling you: “it’s me and I love you like this (with MO), who are you going to trust more? But you don’t… you close yourself off and you lose all desire.” (IDI19).

The women described a shift in their sex drive after bariatric surgery, which was linked to changes in their body image and self-concept. Low libido even led some participants not to have sex for years or even throughout their lives, until they underwent surgery and lost weight.

““I have never had a partner. I have had some opportunities, but as I didn’t love myself and I wasn’t comfortable with myself, if a man approached me, I would pull back. I wasn’t ready to discover more, … I lost my virginity at the age of 40.” (IDI7)”.

The women described how their sex drive was reawakened after bariatric surgery. The participants with partners have noticed that both of them have increased libido, which directly improves their sex lives.

“You feel great and you see that he looks at you differently, he’s more sexually at- tracted to you. Although he used to tell me that he loved me and that I was attractive, … I didn’t quite believe him. Yes, he loves you, he loved you with MO, but now with a better body you are more beautiful, more attractive, you feel better… he also has more sexual appetite, more desire to touch you, … you notice it and it’s nice .” (IDI9).

One aspect that has improved considerably is taking initiative in sexual relations. Before the surgery, the women recognised that they were incapable of taking the initiative, suggesting sex games or introducing changes in their sex life. After gaining confidence and increased libido, they are looking to make changes, to innovate, to know what they want and to suggest it to their partners.

Now I initiate things, and it’s clear that he (partner) wants to (have sex). In the past, he didn’t feel like it because he was always taking the initiative. I said no a lot and he was getting tired of it, … that has changed completely. Now I say what I want and what I don’t like.” (IDI11).

The participants expressed how they did not fully enjoy sexual intercourse before surgery and often did not experience pleasure. The women mentioned having painful sexual experiences, and frequently not reaching orgasm. One participant spoke of how she would fake orgasms to avoid her partner feeling uncomfortable.

It’s complicated, he wants to satisfy you, but you can’t, you don’t feel like it and you don’t have orgasms. It often bothered him (partner), he felt inadeqate as a man. I won’t deny it, … I have faked it because I was afraid of losing my partner .” (IDI6).

This situation changes radically after surgery; the women now achieve a state of relaxation and confidence that allows them to enjoy sex more. Some participants acknowledged that they have been able to deal with problems in their sex life with their partner that they were unable to solve before.

You are always thinking about not lying this way, that way, … I was always tense. When I was fat, I rarely ever reached orgasm with my partner. More than enjoying it … you are thinking about when it’s going to end.” (IDI5).

Improved body image boosts both partners’ sex drive. These improvements go beyond penetrative sex and have an impact on other sexual behaviours such as masturbation. In addition, improve-ments in female sexuality have a positive impact on the relationship when the man also has problems due to andropause or other sexual dysfunctions.

He had a (sexual) problem before my operation… Although penetration is still difficult, we masturbate, do our own thing and have a good time. It’s not just about penetration, there’s more to it, I go for it and, as he sees me feeling better about myself, he’s encouraged to do it.” (IDI3).

Another noteworthy aspect are the changes that are brought about by improved self-confidence. Some of the women become empowered after bariatric surgery; they feel more attractive, want to be more feminine and attract men. This situation can change the status of their relationships, occasionally leading to break-ups or their male partners feeling jealous.

You suddenly feel pretty, you are noticed, you are liked, you go out and socialise more …. It is difficult for both you and your partner to deal with this situation. He doesn’t always handle it well, he is not used to people looking at me like that (with desire). Yes, it can lead to arguments and problems. If the couple does not have a solid relationship, you can lose it all .” (IDI15).

The aim of our study was to describe and understand the experiences of morbidly obese heterosexual women regarding their body image and sexuality two or more years after bariatric surgery. Our results show that the changes in the participants’ sex lives are positive for both themselves and their partners. Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology has allowed us to explore the self-perception of the body and its influence on these women’s sexuality and life, confirming experiences in lived space, body, time and relationships [ 32 ]. According to Nilsson-Condori et al. (2020), a key factor in women with MO opting for surgery is the associated improvement in self-concept and self-esteem [ 36 ]. Additional motives for our participants, previously described by Paul et al. (2023) and Cohn et al. (2019), were to better their physical health and social relationships [ 26 , 27 ]. In line with other studies [ 17 , 37 ], our results confirm that weight loss after bariatric surgery improves the perception of sexual function, body image satisfaction and self-esteem in women with MO [ 38 , 39 ]. Our results contrast with the study by Abdelsamea et al. (2023), who associate weight loss with psychological and quality of life improvements, but not with improvements in female sexual dysfunction [ 40 ]. Consistent with our findings, weight reduction after surgery boosts confidence and self-esteem, thereby improving social interactions [ 29 , 41 ]. In line with the study by Wingfield et al. (2016), two years after bariatric surgery, the patients rediscover themselves and seem to regain lost hope [ 42 ]. Although some women suffer postoperative anxiety [ 22 ], our results do not reflect this, perhaps because several years have passed since the intervention. Body image and physical appearance are fundamental in the process; surgery results in temporal, spatial and relational changes in sexuality [ 32 ]. According to our results, the process is not static; surgery is not the end of the journey with MO, but rather the beginning of a new journey that involves sexuality. Women with partners acknowledge having support before and after surgery, and their partners also benefit from their improved sexuality [ 18 ]. Our results regarding the women’s partners are ambivalent, because while they seem to experience improvements in their sex life after the women undergo bariatric surgery, female empowerment leads the men to feel insecure. Indeed, studies such as that of Braming et al. (2021) have found that bariatric surgery is associated with increased likelihood of finding a partner for single people and increased risk of separation from a partner for those in a relationship [ 43 ]. Our participants agreed that the improvement of female self-concept and body image can lead to a lack of trust in their relationship as the men fear that their partners will leave them [ 17 ]. Our findings on the participants’ experiences corroborate that bariatric surgery improves sexual activity, sex drive, orgasm, intimacy, mobility, variety of sex positions and games [ 11 , 21 , 36 , 37 , 42 , 44 ]. Even negative effects, such as excess skin, seem to be overlooked by the women in our study [ 45 ]. Understanding the concept of poor body image in bariatric surgery patients allows healthcare providers to provide preoperative preparation and postoperative interventions [ 46 ]. Implementing psychological care focusing on body functionality [ 28 , 39 , 47 ], promoting sex education and encouraging self-care [ 48 ], could be the key to a long-term recovery of morbidly obese women’s well-being, body image and sexuality after bariatric surgery. We concur with Lindberg et al. (2022) that the partners’ preparation for the life changes that arise after bariatric surgery may not be adequate; more time and a dialogic approach are needed for each individual to be able to manage and improve their sexual health [ 31 ]. Our study is one of the few that addresses the sexuality of women with MO after bariatric surgery, focusing on corporeality and their own experiences. This is a strength as women suffer from the social stigma of being overweight and struggle to talk about their sexuality, making it difficult to get them to participate in qualitative studies.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations. Part of our sample was collected from a private hospital so women with fewer financial resources could be under-represented. The women knew one of the researchers; although it led them to agree to participate in the study, their accounts could have been biased. Part of our sample also participated in previous studies on experiences in the pre-operative phase. The more time that passes after bariatric surgery, the more the participants’ experiences of their sexuality can change. Therefore, findings may differ at much later stages. Our results only reflect the experiences of women who are sexually attracted to men; conclusions cannot be extended to other female sexual identities or partners.

Sexual health has been shown to be key in improving the quality of life of women with MO after bariatric surgery. Weight loss and improved body image change the lives of these women; reconciliation with their bodies is linked to improvements in perceived self-esteem, communication and social relationships. The participants stated that since bariatric surgery they are once again able to enjoy a sense of sexuality they thought they had lost. The progressive increase in their self-confidence and desire is empowering. The women regain initiative and control of their sex lives, which has a direct impact on their social and sex lives, as well as on those of their partners. Going from a life as an obese person to having a radically slimmer body brings them face to face with an unexpected reality of mixed consequences. Despite the improvements they experience following bariatric surgery, they still have to deal with the stigma of being overweight and the impact it has on their relationships. This study is an exploration of the experiences of women with MO who have undergone bariatric surgery in relation to their sexuality. Further research could delve into these experiences at later stages among women with different sexual identities. There is also potential to develop interventions for improvement or to study the partners’ perceptions of changes in their social and sex lives.

Implications for practice

Changes in body image, sexuality and social relationships should be addressed systematically by healthcare providers throughout the care of women with MO after bariatric surgery. Sexuality should be incorporated into care protocols and clinical practice guidelines right from when women are admitted into bariatric surgery programmes, given that progressive changes in post-surgical stages call for more long-term follow-up and support. The evolution of female sexuality after bariatric surgery affects both the individual and her partner; understanding the experiences of these women is key for designing specific interventions to provide coping strategies and support, which could benefit from including their partners.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to confdentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

WHO (World Health Organization). Obesity and Overweight. WHO, Geneva, 2020.

Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, Michael, Collazo-Clavell ML, Spitz AF, et al. Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient. Obesity. 2009;17:S1–70.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, Garvey WT, Hurley DL, McMahon MM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient – 2013. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:159–91.

Liu S, Cao D, Ren Z, Li J, Peng L, Zhang Q. The relationships between bariatric surgery and sexual function: current evidence based medicine. BMC Urol. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Article Google Scholar

Mazer L, Morton JM. The obesity epidemic. In: Reavis KM, Barrett AM, Kroh MD, editors. Editors. The SAGES manual of bariatric surgery. Switzerland: Springer; 2018. pp. 81–92.

Chapter Google Scholar

INE (Instituto nacional de estadística. National Institute of statistics). Encuesta europea de salud en España 2020 [European Health Survey in Spain 2020]. 2020. https://www.ine.es/ss/Satellite?L=es_ES&c=INESeccion_C&cid=1259926457058&p=1254735110672&pagename=ProductosYServicios%2FPYSLayout . Accessed 4 Octr 2023.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2023. WHO acceleration plan to stop obesity. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/367784/9789240073234-eng.pdf?sequence=1 . Accessed 2 oct 2023.

Sfahani SB, Pal S. Does metabolic syndrome impair sexual functioning in adults with overweight and obesity? Int J Sex Health. 2019;31:170–85.

Rowland DL, McNabney SM, Mann AR. Sexual function, obesity, and weight loss in men and women. Sex Med Rev. 2016;5:323–38.

Taskin F, Karakoc A, Demirel G. The effect of body image on sexual quality of life in obese married women. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40:479–92.

Loh HH, Shahar MA, Loh HS, Yee A. Female sexual dysfunction after bariatric surgery in women with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Surg. 2022;111(1):14574969211072395.

Deniz A, Okuyucu M. The impact of obesity on fertility and sexual function in women of child bearing age. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;42:3129–33.

Jans G, Matthys C, Bel S, Ameye L, Lannoo M, Van der Schueren B, et al. AURORA: bariatric surgery registration in women of reproductive age - a multicenter prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):1–11.

Salari N, Hasheminezhad R, Sedighi T, Zarei H, Shohaimi S, Mohammadi M. The global prevalence of sexual dysfunction in obese and overweight women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):375.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ferrández A, Novella B, Khan KS, Zamora J, Jurado AR, Fragoso M, Suárez C. Obesity and female sexual dysfunctions: a systematic review of prevalence with meta-analysis. Semergen. 2023;49:102022.

Ivezaj V, Grilo CM. The complexity of body image following bariatric surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2018;19:1116–40.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pichlerova D, Bob P, Zmolikova J, Herlesova J, Ptacek R, Laker MK, Raboch J, Fait T, Weiss P. Sexual dysfunctions in obese women before and after bariatric surgery. Med Sci Monit. 2019;27:3108–14.

Frederick DA, Gordon AR, Cook-Cottone CP, Brady JP, Reynolds TA, Alley J, Murray S. Demographic and sociocultural predictors of sexuality-related body image and sexual frequency: the U.S. Body Project I. Body Image. 2022;41:109–27.

Thomas HN, Hamm M, Borrero S, Hess R, Thurston RC. Body image, attractiveness, and sexual satisfaction among midlife women: a qualitative study. J Womens Health. 2019;28:100–6.

Ramseyer V, Ruhr L, Pevehouse D, Pilgrim S. Exploring body image, contraceptive use, and sexual health out-comes among an ethnically diverse sample of women. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47:715–23.

Gao Z, Liang Y, Deng W, Qiu P, Li M, Zhou Z. Impact of bariatric surgery on female sexual function in obese patients: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2019;30:352–64.

Steffen KJ, King WC, White GE, et al. Changes in sexual functioning in women and men in the 5 years after bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(6):487–98.

Bosc L, Mathias F, Monsaingeon M, Gronnier C, Pupier E, Gatta-Cherifi B. Long-term changes in body image after bariatric surgery: An observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2022; 7;17(12):e0276167.

Campedelli V, Ciacchella C, Veneziani G, Meniconzi I, Paone E, Silecchia G, Lai C. Body image and body mass index influence on psychophysical well-being in bariatric patients: a cross-sectional study. J Pers Med. 2022;12(10):1597.

Makarawung DJS, Monpellier VM, van den Brink F, Woertman L, Zijlstra H, Mink AB, van Ramshorst B, Geenen R. Body image as a potential motivator for bariatric surgery: a case-control study. Obes Surg. 2020;30(10):3768–75.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Paul R, Drott J, Olbers T, Frisk J, Andersson E. Motherhood and motivations for bariatric surgery - a qualitative study. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2023;26(2):257–65.

Cohn I, Raman J, Sui Z. Patient motivations and expectations prior to bariatric surgery: a qualitative systematic review. Obes Rev. 2019;20(11):1608–18.

Mento C, Silvestri MC, Muscatello MRA, Rizzo A, Celebre L, Cedro C, Zoccali RA, Navarra G, Bruno A. The role of body image in obese identity changes post bariatric surgery. Eat Weight Disord. 2022;27(4):1269–78.

Granero-Molina J, Torrente-Sánchez MJ, Ferrer-Márquez M, Hernández-Padilla JM, Sánchez-Navarro M, Ruiz-Muelle A, Ruiz-Fernández MD, Fernández-Sola C. Sexuality amongst heterosexual women with morbid obesity in a bariatric surgery programme: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(11):4537–48.

Granero-Molina J, Torrente-Sánchez MJ, Ferrer-Márquez M, Hernández-Padilla JM, Ruiz-Muelle A, López-Entrambasaguas OM, Fernández-Sola C. Sexuality amongst heterosexual men with morbid obesity in a bariatric surgery programme: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(21–22):4258–69.

Lindberg S, Wennström B, Larsson AK. Facing an unexpected reality - oscillating between health and suffering 4–6 years after bariatric surgery. Scand J Caring Sci. 2022;36(4):1074–82.

Merleau Ponty. M. Phenomenology of perception. London: Routledge; 2013.

Book Google Scholar

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57.

Fernández-Sola C. Análisis de datos cualitativos [Qualitative data análisis] In Comprender para cuidar. Avances en Investigación Cualitativa en Ciencias de la Salud; Fernández-Sola, C., Granero-Molina, J. Hernández-Padilla, J.M, editors Servicio Publicaciones Universidad de Almería (Colección Ciencias de la Salud, Almería, 2019, pp. 239–261.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. London: Sage; 1985.

Nilsson-Condori E, Järvholm S, Thurin-Kjellberg A, Hedenbro J, Friberg B. A new beginning: young women’s experiences and sexual function 18 months after bariatric surgery. Sex Med. 2020;8(4):730–9.

Oliveira CFA, Dos Santos PO, de Oliveira RA, Leite-Filho H, de Almeida AF, Bagano GO, Lima EB, Miranda EP, de Bessa J, Arroso U. Changes in sexual function and positions in women with severe obesity af-ter bariatric surgery. Sex Med. 2019;7(1):80–5.

Souza ALL, de Souza PM, Mota BEF, Xavier CLF, Santiago FG, Oliveira JS, Borges SA, Bearzoti E, Gama EF, Souza GGL. Ghost fat: altered female body perception after bariatric surgery. Percept Mot Skills. 2023;130(1):301–16.

Cherick F, Te V, Anty R, Turchi L, Benoit M, Schiavo L, Iannelli A. Bariatric surgery significantly improves the quality of sexual life and self-esteem in morbidly obese women. Obes Surg. 2019;29(5):1576–82.

Abdelsamea GA, Amr M, Tolba AMN, Elboraie HO, Soliman A, Al-Amir B, Ali F, Osman DA. Impact of weight loss on sexual and psychological functions and quality of life in females with sexual dysfunction: a forgotten avenue. Front Psychol. 2023;1(14):1090256.

Pokorski M, Głuch A. Perception of well-being and quality of life in obese patients after bariatric surgery. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2022;1374:81–90.

Wingfield LR, Kulendran M, Laws G, Chahal H, Scholtz S, Purkayastha S. Change in sexual dysfunction following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2016;26(2):387–94.

Bramming M, Hviid SS, Becker U, Jørgensen MB, Neermark S, Bisgaard T, Tolstrup JS. Changes in relation-ship status following bariatric surgery. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021;45(7):1599–606.

Treacy PJ, Mazoyer C, Falagario U, Iannelli A. Sexual activity after bariatric surgery: a prospective monocentric study using the PISQ-IR Questionnaire. J Sex Med. 2019;16(12):1930–7.

Baillot A, Brunet J, Lemelin L, Gabriel SA, Langlois MF, Tchernof A, Biertho L, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Garneau PY, Aimé A, Bouchard S, Romain AJ, Bernard P. Factors associated with excess skin after bariatric surgery: a mixed-method study. Obes Surg. 2023;33(8):2324–34.

Perdue TO, Schreier A, Neil J, Carels R, Swanson MA. Concept analysis of disturbed body image in bariatric surgery patients. Int J Nurs Knowl. 2020;31(1):74–81.

Alleva JM, Atkinson MJ, Vermeulen W, Monpellier VM, Martijn C. Beyond body size: focusing on body func-tionality to improve body image among women who have undergone bariatric surgery. Behav Ther. 2023;54(1):14–28.

Walsh Ó, Dettmer E, Regina A, Dentakos S, Christian J, Hamilton J, Toulany A. Teenagers are into perfect-looking things’: dating, sexual attitudes and experiences of adolescents with severe obesity. Child Care Health Dev. 2022;48(3):406–14.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank all the women who participated in this study.

This study had the support of the Health Sciences Research Group of the University of Almería (CTS-451).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Physiotheraphy and Medicine Department, University of Almería, Almería, Spain

José Granero-Molina, María del Mar Jiménez-Lasserrotte, Cayetano Fernández-Sola & María Dolores Ruiz-Fernández

Faculty of Health Sciences, Universidad Autónoma de Chile, Chile, Santiago, 7500000, Spain

José Granero-Molina

Bariatric Surgery, Andalusian Health Service, Almería, Spain

Cristina Arias Hoyos

Bariatric Surgery, Mediterraneo Hospital, Almería, Spain

María José Torrente Sánchez

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JGM and MMJL conceived the study. MJTS and CAH conducted the interviews. CFS anf MRF performed the transcriptions, led the analysis, and wrote manuscript drafts.JGM, MJTS and MMJL provided critical feedback and helped shape the analysis and manuscript to its fnal version. All authors read and approved the fnal manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to María del Mar Jiménez-Lasserrotte .

Ethics declarations

The study protocol was approved by the University of Almería Ethics and Research Committee.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Permission was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of a university (EFM-45/2018).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Granero-Molina, J., Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M.M., Arias Hoyos, C. et al. Sexuality and self-concept of morbidly obese women who are sexually attracted to men after bariatric surgery: a phenomenological study. BMC Women's Health 24 , 174 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03014-1

Download citation

Received : 29 December 2023

Accepted : 06 March 2024

Published : 13 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03014-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Bariatric surgery

- Experiences

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, patients' experiences and perspectives regarding the use of digital technology to support exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation: a qualitative interview study.

- 1 Faculty of Medicine, Paracelsus Medical University, Salzburg, Austria

- 2 Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Digital Health and Prevention, Salzburg, Austria

- 3 University Institute of Sports Medicine, Prevention and Rehabilitation and Research Institute of Molecular Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation, Paracelsus Medical University, Salzburg, Austria

- 4 Department of Health Promotion, Care and Public Health Research Institute, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands

Introduction: Despite the well-known benefits of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, participation in cardiac rehabilitation programmes and adherence to secondary prevention recommendations remain limited. Digital technologies have the potential to address low participation and adherence but attempts at implementing digital health interventions in real-life clinical practice frequently encounter various barriers. Studies about patients' experiences and perspectives regarding the use of digital technology can assist developers, researchers and clinicians in addressing or pre-empting patient-related barriers. This study was therefore conducted to investigate the experiences and perspectives of cardiac rehabilitation patients in Austria with regard to using digital technology for physical activity and exercise.

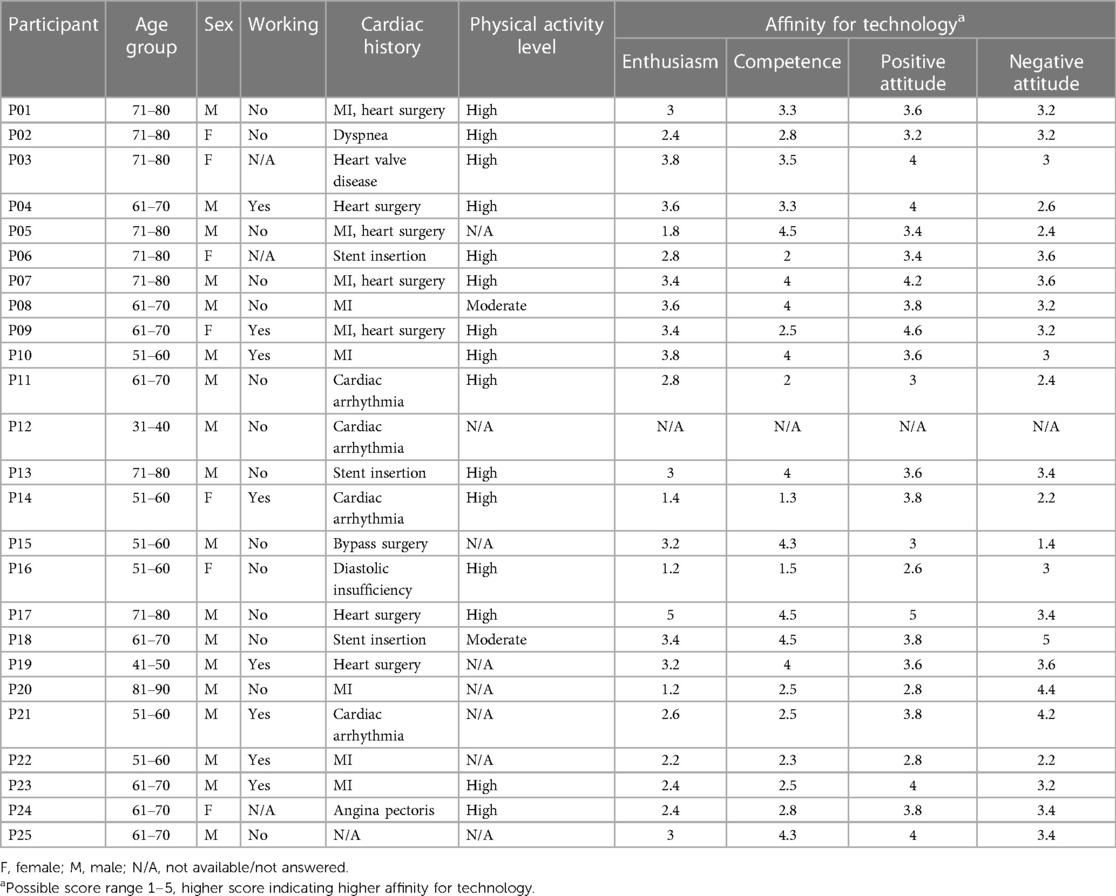

Methods: Twenty-five current and former cardiac rehabilitation patients (18 men and 7 women, age range 39 to 83) with various cardiac conditions were recruited from a clinical site in Salzburg, Austria. Semi-structured qualitative interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The analysis followed a descriptive phenomenological approach, applying the framework analysis method.

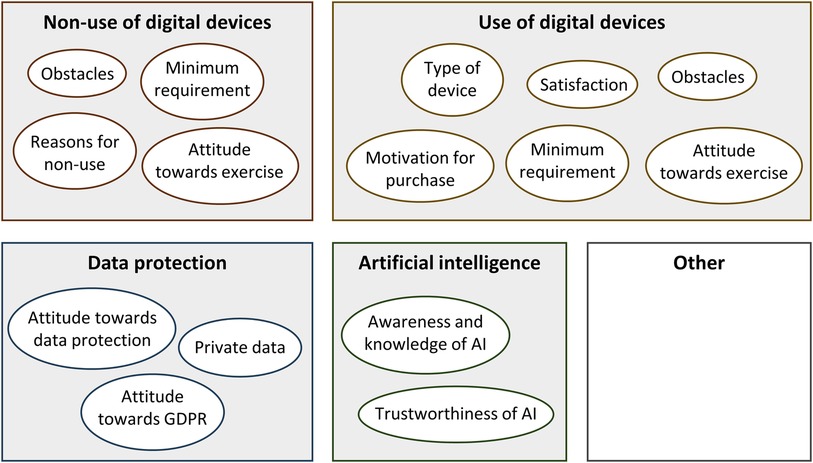

Results: The sample was diverse, including interviewees who readily used digital devices to support their physical activity, exercise and health monitoring, and interviewees who did not. Simplicity, convenience and accessibility were highlighted as important facilitators for the use of digital technology, while annoyance with digital devices, concerns about becoming dependent on them, or simply a preference to not use digital technology were commonly stated reasons for non-use. Interviewees' views on data protection, data sharing and artificial intelligence revealed wide variations in individuals' prior knowledge and experience about these topics, and a need for greater accessibility and transparency of data protection regulation and data sharing arrangements.

Discussion: These findings support the importance that is attributed to user-centred design methodologies in the conceptualisation and design of digital health interventions, and the imperative to develop solutions that are simple, accessible and that can be personalised according to the preferences and capabilities of the individual patient. Regarding data protection, data sharing and artificial intelligence, the findings indicate opportunity for information and education, as well as the need to offer patients transparency and accountability in order to build trust in digital technology and digital health interventions.

1 Introduction

The growing prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) presents an increasing global challenge. Accounting for 18.6 million deaths per year in 2019, CVD remains the leading cause of death worldwide ( 1 ). Patients suffering from CVD and its sequelae such as myocardial infarction, heart failure and stroke face severe burden, including reduced quality of life, reduced exercise tolerance and a higher risk of hospital admissions and mortality ( 2 ). In Austria in 2019, the age-standardised CVD incidence was 654 per 100,000, the age-standardised mortality attributed to CVD was 151 per 100,000, and CVD accounted for 5,105 disability-adjusted life-years per 100,000 across all ages in both sexes ( 1 ). Prevention is of utmost importance to reduce morbidity and mortality caused by CVD ( 3 ).

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is an evidence-based secondary prevention model that has been proven to prolong life and improve functional capacity, well-being and quality of life for individuals with CVD ( 4 , 5 ). Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is a multidisciplinary intervention comprising clinical assessments, patient education, pharmacological therapy, exercise training, physical activity counselling, psychological support and support to address CVD risk factors and lifestyle modifications. In the setting of this study in Austria, cardiac rehabilitation provision is standardised according to national guidelines and organised in four phases: phase I refers to the acute hospital admission; phase II refers to a structured programme under medical supervision in an inpatient (3 to 4 weeks) or outpatient (up to 6 weeks) setting, with the main focus on improving physical performance; phase III refers to a 6 to 12 months outpatient programme, with the aim of supporting sustainability of lifestyle modifications; and phase IV refers to patients' independent lifelong secondary prevention by continuing the CVD preventive behaviour from the previous phases ( 6 , 7 ). Notably, the structure and organisation of cardiac rehabilitation programmes can differ between countries ( 8 ).

Despite the well-known benefits of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation, many patients who qualify for it based on their medical history do not participate in cardiac rehabilitation programmes, with reported participation rates among eligible CVD patients in Austria of 30% and 20% for phases II and III, respectively ( 9 ), and 30%–50% in other European countries ( 8 ). Moreover, there is limited adherence and carry-over from the well-supervised cardiac rehabilitation phases to patients' independent secondary prevention behaviour. The maintenance of regular heart-healthy physical activity and exercise, for example, constitutes a crucial secondary prevention behaviour, but the effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation programmes for establishing long-tern physical activity habits is variable ( 10 , 11 ).

Low participation in cardiac rehabilitation programmes and poor long-term adherence to CVD secondary prevention behaviours are important contributing factors for re-hospitalisation and high rates of morbidity and mortality. The underlying reasons for low participation and poor adherence are many and multi-faceted ( 12 , 13 ), including patients' employment and family responsibilities, location of cardiac rehabilitation centres and resulting travel times for patients, lack of social support from family and friends, and lack of knowledge and low health literacy (i.e., an individual's ability to access, understand and act on health information; 14 ) of individuals with CVD.

Digital technologies have the potential to address or at least alleviate some of these reasons. The term “digital health” describes the implementation of digital technology in the context of healthcare, encompassing “electronic health” (i.e., the use of information and communications technology in the health domain), “mobile health” (i.e., the use of wireless technologies for the purpose of health), “telemedicine” (i.e., the provision of health services at a distance), and emerging areas such as the use of advanced computing sciences in big data and artificial intelligence ( 15 ). Numerous scientific publications describe the vast potential of digital health interventions to advance the care of individuals with CVD, for example by enabling home-based and technology-based cardiac rehabilitation across phases II, III and IV ( 16 ), by supporting regular physical activity and other heart-healthy lifestyle modifications through text-messaging programmes, smartphone applications and wearable devices ( 17 ), or by enhancing clinical decision-making through artificial intelligence-supported analysis of large volumes of patient data ( 18 ). Moreover, systematic reviews provide good evidence of patient safety of digital health interventions for cardiac rehabilitation, with some studies even reporting fewer associated adverse events in digital intervention groups than in control groups ( 19 ). However, attempts at implementing such digital health interventions in real-life clinical practice frequently encounter various barriers ( 20 ). From the perspective of CVD patients, two consistently reported barriers are poor digital literacy and skills (i.e., lack of understanding of, or lack of physical capabilities to interact with digital health interventions) and low acceptability (i.e., lack of perceived effectiveness and low use of digital health interventions; 20 ).

Insight into CVD patients’ experiences and perspectives regarding the use of digital technology can assist developers, researchers and clinicians in addressing or pre-empting these patient-related barriers. These patient perspectives can be incorporated in the design of digital health interventions and in the design of evaluation studies and implementation strategies for digital health interventions. But to date, there have not been any publications of such studies for the Austrian cardiac rehabilitation community.

The present study was therefore conducted to investigate the experiences and perspectives of cardiac rehabilitation patients in Austria with regard to using digital technology, in particular for physical activity and exercise. The study addressed the following research questions: What are the reasons for use or non-use of digital devices? What are obstacles to the implementation of digital health interventions? What is the user experience and acceptance of currently available digital technology? And what are patients' views on recent developments and challenges in digital health around data protection, data sharing and artificial intelligence?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 study design.

We conducted a qualitative study with semi-structured interviews to explore patients' experiences and perspectives regarding the use of digital technology to support exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation. The reporting of this study follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ; 21 ). The COREQ checklist is provided in Supplementary Appendix S1 . In the overarching methodological orientation of this work, we took a phenomenological approach, aiming to explore the topic from the perspective of those who have lived experience of CVD and cardiac rehabilitation ( 22 ).

2.2 Setting and sampling

The study was conducted at the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Digital Health and Prevention in Salzburg, Austria. Participants were recruited from among current and previous cardiac rehabilitation patients at the University Institute of Sports Medicine, Prevention and Rehabilitation in Salzburg, Austria. The sampling strategy was purposive, aiming for diverse representation in terms of age, gender and time since cardiac event.

A target sample of 25 participants was possible within the study resources and timeline and expected to yield relevant breadth and depth of data. Eligible were adult patients with a diagnosed CVD who were current or previous participants in phase II cardiac rehabilitation and residents of the city of Salzburg or its surrounding areas. Excluded were individuals with limited German language proficiency. Forty-nine eligible patients were identified from patient records at the recruiting site and invited to take part in the study, either in writing by letter or in person by clinical staff at the site. Patients were provided with a study information leaflet including a contact for patients to inquire further about the study. Patients were given at least 48 h to consider their participation in the study. All patients who agreed to take part in the study gave written informed consent.

2.3 Data collection

The content of the semi-structured interviews was developed based on relevant literature and included questions to explore two major topic areas: physical activity in cardiac rehabilitation, and digital technology. The interview guide was piloted with members of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute's service user advisory group, consisting of CVD patients who had attended cardiac rehabilitation. All interviews were conducted by JG either face-to-face in a private room at the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute or remotely via video call if preferred by the participant. Interviews lasted between 34 and 92 min. No other persons were present during the interviews. Each participant gave one interview. All interviews took place during July to October 2020. All interviews were conducted in German. Interviews were audio-recorded on two voice recorders. Opening questions were asked verbatim according to the interview guide, and follow-up questions were asked optionally and depending on the course of the conversation. An English translation of the interview guide is attached in Supplementary Appendix S2 .

Concluding the interview, participants were asked to answer demographic and disease-related questions, and to self-complete the German version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF; 23 ) and the German TA-EG questionnaire, a measure of affinity for technology ( 24 ). The IPAQ-SF includes seven questions to capture the volume and intensity of physical activity during the past seven days, allowing an estimate of physical activity levels (low, moderate, high) based on metabolic equivalents of tasks. The TA-EG questionnaire comprises 19 statements about technology (enthusiasm in the interaction with technology, subjectively experienced competence, positive consequences and negative consequences of the usage of technology), and respondents rate the extent to which each statement applies to them. Ratings range from 1 to 5, with higher scores reflecting higher affinity for technology. Participants completed the questionnaires independently while the interviewer remained in the room, available to answer questions if needed.

2.4 Data analysis

For our data analysis, we applied a mixed deductive and data-driven inductive approach using framework analysis according to the steps described by Gale et al. ( 25 ): transcription, familiarisation with the interview, coding, developing a working analytical framework, applying the analytical framework, charting data into a framework matrix and interpreting the data.

All audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim, partly by the interviewing researcher (JG) and partly by a professional transcription service. Transcripts were pseudonymised, removing any information that could identify the speaking participant. These transcripts, supplemented by the IPAQ-SF and TA-EG questionnaires, constituted the data for analysis.