- PRESENTATION SKILLS

Deciding the Presentation Method

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Presentation Skills:

- A - Z List of Presentation Skills

- Top Tips for Effective Presentations

- General Presentation Skills

- What is a Presentation?

- Preparing for a Presentation

- Organising the Material

- Writing Your Presentation

- Managing your Presentation Notes

- Working with Visual Aids

- Presenting Data

- Managing the Event

- Coping with Presentation Nerves

- Dealing with Questions

- How to Build Presentations Like a Consultant

- 7 Qualities of Good Speakers That Can Help You Be More Successful

- Self-Presentation in Presentations

- Specific Presentation Events

- Remote Meetings and Presentations

- Giving a Speech

- Presentations in Interviews

- Presenting to Large Groups and Conferences

- Giving Lectures and Seminars

- Managing a Press Conference

- Attending Public Consultation Meetings

- Managing a Public Consultation Meeting

- Crisis Communications

- Elsewhere on Skills You Need:

- Communication Skills

- Facilitation Skills

- Teams, Groups and Meetings

- Effective Speaking

- Question Types

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

There is much to consider in deciding on an appropriate presentation method.

This page assumes that you have already prepared your presentation , or at least decided on the key messages that you wish to get across to your audience, and given at least some thought to how to organise your material .

On this page, then, we focus on the mechanics of your presentation method: how you will present.

This includes using sound systems, how to manage visual aids, how you stand, and how much interaction you want with your audience.

What Helps you to Decide your Presentation Method?

In making a decision about your presentation method, you have to take into account several key aspects. These include:

The facilities available to you by way of visual aids, sound systems, and lights. Obviously you cannot use facilities that are not available. If you are told that you will need to present without a projector, you’re going to need to decide on a method that works without slides.

The occasion. A formal conference of 200 people will require a very different approach from a presentation to your six-person team. And a speech at a wedding is totally different again. Consider the norms of the occasion. For example, at a wedding, you are not expected to use slides or other visual aids.

The audience, in terms of both size and familiarity with you, and the topic. If it’s a small, informal event, you will be able to use a less formal method. You might, for example, choose to give your audience a one-page handout, perhaps an infographic that summarises your key points, and talk them through it. A more formal event is likely to need slides.

Your experience in giving presentations. More experienced presenters will be more familiar with their own weak points, and able to tailor their preparation and style to suit. However, few people are able to give a presentation without notes. Even the most experienced speakers will usually have at least some form of notes to jog their memory and aid their presentation.

Your familiarity with the topic. As a general rule, the more you know about it, the less you will need to prepare in detail, and the more you can simply have an outline of what you want to say, with some brief reminders.

Your personal preferences. Some people prefer to ‘busk it’ (or ‘wing it’) and make up their presentation on the day, while others prefer detailed notes and outlines. You will need to know your own abilities and decide how best to make the presentation. When you first start giving presentations you may feel more confident with more detailed notes. As you become more experienced you may find that you can deliver effectively with less.

Some Different Methods of Presentation

Presentation methods vary from the very formal to the very informal.

What method you choose is largely dictated by the occasion and its formality: very formal tends to go with a larger audience, whose members you do not know well. Your role is likely to be much more providing information, and much less about having a discussion about the information.

Form Follows Function

It’s not going to be possible, for instance, to present to 200 people from a chair as part of the group, because most of your audience will not see or hear you. You need to apply common sense to your choice of presentation method.

Audience Participation

While much of your presentation method will be dictated by the event, there is one area where you have pretty much free rein: audience interaction with you and with each other.

It is perfectly feasible, even in a large conference, to get your audience talking to each other, and then feeding back to you.

In fact, this can work very well, especially in a low-energy session such as the one immediately after lunch, because it gets everyone chatting and wakes them up. It works particularly well in a room set out ‘café-style’, with round tables, but it can also work in a conference hall.

The key is to decide on one or two key questions on which you’d welcome audience views, or on which audience views could improve your session. These questions will depend on your session, but it’s always more helpful to invite views on:

- Something that you haven’t yet decided; or

- Something that the audience is going to do themselves.

For example, you might ask people to talk to their neighbour and identify one thing that they could do to put your speech into action when they return to work and/or home. You can then ask four or five people to tell you about their action points.

Handling your Notes

You also have a choice over how you manage your text, in terms of notes. For more about this, see our page on Managing Your Notes in a Presentation .

The Importance of Iteration

You will probably find that deciding on the presentation method means that you need to change or amend your presentation.

For example, if you want to include some audience participation, you will need to include that in your slides, otherwise, you might well forget in the heat of the moment.

Fortunately, revisiting your presentation in light of decisions about how you will present is probably a good idea anyway. It will enable you to be confident that it will work in practice.

Continue to: Managing your Presentation Notes Working with Visual Aids

See also: Preparing for a Presentation Organising the Presentation Material Dealing with Questions

- Health & Beauty

- Editor Picks

- Personalities

- KIDS July 2021

- KIDS June 2021

- KIDS May 2021

- KIDS April 2021

- What’s On

- All Things Food

- Wines & Spirits

- Distribution Area

- Visit Get It National

- Visit Get It National >

Should you choose contact or distance learning?

Both methods of learning hold benefits, but it can be tricky to choose between them.

While grappling with a global health crisis, teaching staff at campuses across the country have had to find new ways to continue activities that had previously been held in person, in what is known as contact learning. They had to adapt group projects for the online space and use new technologies to help their students.

For those involved in distance learning, however, it was business as usual. Course work and teaching remained relatively unaffected and, in fact, as more people shifted their lives onto the internet during lockdown, they also enrolled in online courses in higher numbers.

Which mode of learning is the best for you? Take this quiz to find out:

- Do you: a) enjoy the energy of being around people according to a timetable, or b) enjoy your own space and freedom with your time?

- Do you: a) have a solid internet connection (Wi-Fi or data), or b) have transport to and accommodation near a campus?

- Do you: a) have the self-discipline and strong internal motivation to study, or b) need motivation from your fellow students and lecturers to study?

- Do you: a) currently work or want to take up a job, or b) have time to study full-time?

- Do you: a) value affordability and convenience, or b) value world-class facilities and face-to-face interactions (with masks, of course)?

Your answers

If you’ve chosen mostly As, distance learning is a great option for you. You value time, money and convenience without compromising on quality. The advantages of distance learning are, students can learn at any time, learn at their own pace and study anywhere.

If you’ve chosen mostly Bs, you should consider contact learning. You benefit from being around people and learning through tactile methods, and you want the full experience of campus life.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

The power of collaborative play for kids

Why term 2 results are crucial for your future in tertiary education

Finding the best Easter hiding spots in your home

- Competition T&C

- Privacy Policy

Exposing children to germs… how much is too much?

Keep your precious cargo safe in the car

Ideas and insights from Harvard Business Publishing Corporate Learning

Powerful and Effective Presentation Skills: More in Demand Now Than Ever

When we talk with our L&D colleagues from around the globe, we often hear that presentation skills training is one of the top opportunities they’re looking to provide their learners. And this holds true whether their learners are individual contributors, people managers, or senior leaders. This is not surprising.

Effective communications skills are a powerful career activator, and most of us are called upon to communicate in some type of formal presentation mode at some point along the way.

For instance, you might be asked to brief management on market research results, walk your team through a new process, lay out the new budget, or explain a new product to a client or prospect. Or you may want to build support for a new idea, bring a new employee into the fold, or even just present your achievements to your manager during your performance review.

And now, with so many employees working from home or in hybrid mode, and business travel in decline, there’s a growing need to find new ways to make effective presentations when the audience may be fully virtual or a combination of in person and remote attendees.

Whether you’re making a standup presentation to a large live audience, or a sit-down one-on-one, whether you’re delivering your presentation face to face or virtually, solid presentation skills matter.

Even the most seasoned and accomplished presenters may need to fine-tune or update their skills. Expectations have changed over the last decade or so. Yesterday’s PowerPoint which primarily relied on bulleted points, broken up by the occasional clip-art image, won’t cut it with today’s audience.

The digital revolution has revolutionized the way people want to receive information. People expect presentations that are more visually interesting. They expect to see data, metrics that support assertions. And now, with so many previously in-person meetings occurring virtually, there’s an entirely new level of technical preparedness required.

The leadership development tools and the individual learning opportunities you’re providing should include presentation skills training that covers both the evergreen fundamentals and the up-to-date capabilities that can make or break a presentation.

So, just what should be included in solid presentation skills training? Here’s what I think.

The fundamentals will always apply When it comes to making a powerful and effective presentation, the fundamentals will always apply. You need to understand your objective. Is it strictly to convey information, so that your audience’s knowledge is increased? Is it to persuade your audience to take some action? Is it to convince people to support your idea? Once you understand what your objective is, you need to define your central message. There may be a lot of things you want to share with your audience during your presentation, but find – and stick with – the core, the most important point you want them to walk away with. And make sure that your message is clear and compelling.

You also need to tailor your presentation to your audience. Who are they and what might they be expecting? Say you’re giving a product pitch to a client. A technical team may be interested in a lot of nitty-gritty product detail. The business side will no doubt be more interested in what returns they can expect on their investment.

Another consideration is the setting: is this a formal presentation to a large audience with questions reserved for the end, or a presentation in a smaller setting where there’s the possibility for conversation throughout? Is your presentation virtual or in-person? To be delivered individually or as a group? What time of the day will you be speaking? Will there be others speaking before you and might that impact how your message will be received?

Once these fundamentals are established, you’re in building mode. What are the specific points you want to share that will help you best meet your objective and get across your core message? Now figure out how to convey those points in the clearest, most straightforward, and succinct way. This doesn’t mean that your presentation has to be a series of clipped bullet points. No one wants to sit through a presentation in which the presenter reads through what’s on the slide. You can get your points across using stories, fact, diagrams, videos, props, and other types of media.

Visual design matters While you don’t want to clutter up your presentation with too many visual elements that don’t serve your objective and can be distracting, using a variety of visual formats to convey your core message will make your presentation more memorable than slides filled with text. A couple of tips: avoid images that are cliched and overdone. Be careful not to mix up too many different types of images. If you’re using photos, stick with photos. If you’re using drawn images, keep the style consistent. When data are presented, stay consistent with colors and fonts from one type of chart to the next. Keep things clear and simple, using data to support key points without overwhelming your audience with too much information. And don’t assume that your audience is composed of statisticians (unless, of course, it is).

When presenting qualitative data, brief videos provide a way to engage your audience and create emotional connection and impact. Word clouds are another way to get qualitative data across.

Practice makes perfect You’ve pulled together a perfect presentation. But it likely won’t be perfect unless it’s well delivered. So don’t forget to practice your presentation ahead of time. Pro tip: record yourself as you practice out loud. This will force you to think through what you’re going to say for each element of your presentation. And watching your recording will help you identify your mistakes—such as fidgeting, using too many fillers (such as “umm,” or “like”), or speaking too fast.

A key element of your preparation should involve anticipating any technical difficulties. If you’ve embedded videos, make sure they work. If you’re presenting virtually, make sure that the lighting is good, and that your speaker and camera are working. Whether presenting in person or virtually, get there early enough to work out any technical glitches before your presentation is scheduled to begin. Few things are a bigger audience turn-off than sitting there watching the presenter struggle with the delivery mechanisms!

Finally, be kind to yourself. Despite thorough preparation and practice, sometimes, things go wrong, and you need to recover in the moment, adapt, and carry on. It’s unlikely that you’ll have caused any lasting damage and the important thing is to learn from your experience, so your next presentation is stronger.

How are you providing presentation skills training for your learners?

Manika Gandhi is Senior Learning Design Manager at Harvard Business Publishing Corporate Learning. Email her at [email protected] .

Let’s talk

Change isn’t easy, but we can help. Together we’ll create informed and inspired leaders ready to shape the future of your business.

© 2024 Harvard Business School Publishing. All rights reserved. Harvard Business Publishing is an affiliate of Harvard Business School.

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Information

- Terms of Use

- About Harvard Business Publishing

- Higher Education

- Harvard Business Review

- Harvard Business School

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Cookie and Privacy Settings

We may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

15 Essential Presentation Techniques for Winning Over Any Audience

- The Speaker Lab

- April 13, 2024

Table of Contents

Ever found yourself standing before an audience, your heart racing? That’s the moment when knowing effective presentation techniques can prove to be your unwavering ally. But what are presentation techniques? And what makes them so powerful? In this article, we’re going to answer those questions.

Before we can talk about presentation techniques, though, we first have to talk about good communication. The power of effective communication isn’t just in what you say. It’s how you say it; it’s in those deep breaths that steady nerves, and in maintaining eye contact. It’s about turning a room full of strangers into an engaged audience hanging onto your every word. When it comes to public speaking, real success comes from mastering non-verbal cues to punctuate our words and using visual aids not as crutches but as tools for engagement.

As you hone your communication skills, you will begin to form effective presentation techniques. Expect rough patches as you get the hang of things, but view them as mere footholds propelling you towards your ultimate triumph. Keep pushing forward.

Mastering Presentation Techniques for Impactful Delivery

Presentation techniques are more than just standing in front of a crowd and talking. They’re about making connections, telling stories that resonate, and leaving your audience with something to remember you by.

Elements of an Effective Presentation

For your presentation to resonate, ensure the visuals are straightforward and supportive, rather than distracting. Your message should be concise yet powerful enough to stick. And let’s not forget engagement; keeping your audience on their toes is key.

- Visuals: Keep them simple but impactful.

- Message: Make every word count.

- Engagement: Interact with your audience, ask questions, make them think.

We’ve all seen those slides crammed with text or charts. When you make your slides, don’t cram information, because nobody wants to squint at tiny fonts or decipher complex graphs while trying to listen to you speak. This resource suggests focusing on clarity and simplicity when designing slides—advice worth taking.

Strategies for Delivering a Successful Presentation

To deliver a knockout presentation, start strong. Grab attention from the get-go with an intriguing fact or story related directly back into the topic at hand. Maintain eye contact across the room so everyone feels included in the conversation. Finally, end on a memorable note, either with a call to action or insight gained during the time together. Leave them wanting more information and eager to learn about the subject matter discussed today.

- The opener: Hook your audience with a relevant fact or anecdote.

- Maintain connection: Eyes up, engage everyone around.

- Closing remarks : Last chance for impact–what’s your mic drop?

As author Lilly Walters once said, “The success of your presentation will be judged not by the knowledge you send but by what the listener receives.” This quote reminds us that the true goal of any speech is the understanding achieved between the speaker and the listeners.

Free Download: 6 Proven Steps to Book More Paid Speaking Gigs in 2024

Download our 18-page guide and start booking more paid speaking gigs today!

Engaging Your Audience with Nonverbal Communication

As the name implies, nonverbal communication denotes all of the ways you communicate without using words. This includes eye contact, body language, and facial expressions. Although nonverbal communication might not be the first presentation technique that comes to mind, it’s nevertheless a very powerful tool to have in your arsenal. Let’s take a look.

The Power of Eye Contact, Body Language, and Facial Expressions

Making eye contact isn’t just about looking someone in the eye; it’s about forging a connection. Aim for brief moments of eye contact across different sections of your audience throughout your presentation. Establishing fleeting eye connections across diverse audience segments fosters a sense of trust and keeps them hooked, all while ensuring no one feels on edge.

Body language is similarly important. Stand tall with good posture; it exudes confidence even when you feel nervous. As you grow more confident, mix up standing still with moving around subtly. This dynamic shift holds attention better than being rooted to one spot or nervous pacing. Use your hands to gesture naturally as you speak—it adds emphasis and keeps things lively.

If there’s one thing people can spot from miles away, it’s insincerity. So let those facial expressions match your words. Smile when you share something amusing, and furrow your brow when diving into serious stuff. After all, it’s not just what you say but how visually engaged and passionate you appear while saying it that counts.

Tying these elements together helps you deliver impactful, memorable talks. When done right, folks will leave feeling more connected, understood, and fired up by your presentation, all thanks to your techniques.

Designing Compelling Presentation Materials

Knowing how to design engaging presentation materials is one technique you can’t do without. Far from mere embellishments, these implements are crafted to hammer your message home. Hence, it’s vital to select these aids with great care and discernment.

Tips for Creating Effective Slides

When it comes to crafting slides, think of each as a billboard advertisement for your idea. You want it clear, impactful, and memorable.

- Keep it simple : One idea per slide keeps confusion at bay and attention locked in.

- Use bullet points : Break down your points so your audience can track.

- Pick a font size : Generally speaking, bigger is better.

- Use color : Harness colors that pop without blinding anyone; contrast is key.

- Use images with purpose : A good picture or chart can help illustrate your point, but keep it relevant and don’t overdo it.

With a few helpful visuals, your presentation can go from good to great. For more on creating slides, check out this link here .

Handling Questions and Interactions Professionally

For some speakers, it’s not the presentation itself that makes them nervous—it’s the Q&A session that follows. This is the moment where you get to shine or stumble based on how well you handle those curveballs from your audience. If you want to round off your presentation well, you’re going to want to learn a few techniques for fielding these questions. Let’s look at a few ways of doing this.

Preparing for Audience Questions and How to Address Them Effectively

Below are six techniques that will help you address audience questions effectively.

- Listen Up : The first rule of thumb is to listen like it’s a superpower. When someone throws a question at you, don’t just hear them out—really listen. Demonstrating this level of attentiveness not only conveys your respect but also affords you a brief moment to collect your ideas.

- Stay Calm : You’ve got this. Even if a question catches you off guard, take a deep breath before diving into your answer. No one expects perfection, but showing confidence matters.

- Practice Beforehand : Before presentation day arrives, think about potential questions folks might ask and prep some responses in advance. Practice makes perfect, after all.

- Vary Your Techniques : Not every question needs an essay as an answer; sometimes short and sweet does the trick. Mix up how detailed or brief your answers are depending on what’s asked.

- Show You Care : If you ever get a question that leaves you stumped, say so honestly—but add that magical line: “Let me find out more and I’ll get back to you.” Then actually do it.

- Appreciate Audience Curiosity : Remember that the reason you audience is asking questions is because they’re interested. So no matter what questions you get, keep engaging with enthusiasm.

Go forth with confidence, knowing not only can these moments boost credibility—they make connections too. So next time when facing down those queries remember to listen hard, stay calm & always engage warmly. With these techniques under your belt, answering audience questions after your presentation will feel much less daunting.

Techniques for a Memorable and Effective Presentation

No matter what topic you cover in your presentation, you can easily add in a story, and more likely than not you can add a little humor too. Together, these two presentation techniques are perfect for making your speech memorable.

Incorporating Storytelling into Your Presentation

One great technique for making your presentation stick is telling stories. Stories have the power to touch people profoundly, especially when they depict relatable experiences. So, when you’re up there presenting, kick things off with a story that ties into your main message. It could be personal, something from history, or even an anecdote that gets your point across. Stories are not just fluff; they’re the glue of your presentation. They make complex ideas digestible and memorable.

Using Humor to Connect with the Audience

Another great way of engaging your audience is by using humor. But here’s the deal—use humor wisely. Keep it tasteful and tied closely to the content at hand so it enhances rather than detracts from your message.

- Pick universal themes everyone can relate to.

- Avoid anything potentially offensive.

- Tie jokes back to your key points to make them relevant.

If humor isn’t your thing, or you’re worried about your comedic timing, it’s perfectly okay to skip the jokes. Especially if you’re new to public speaking, humor can be hard to nail immediately. But as you grow and hone your presentation techniques, consider stretching yourself a bit. By starting small, you can practice using humor to connect with your audience. That is your goal, after all—to leave a positive, memorable impression on your audience.

What Type Of Speaker Are You?

Click below to discover your Speaker Archetype and how to start getting booked and paid to speak!

Overcoming Public Speaking Anxiety

For some speakers, stepping in front of a crowd to speak causes immediate anxiety. But fear not! Conquering public speaking anxiety is entirely within your grasp.

Techniques to Manage Stage Fright and Boost Confidence

First off, feeling nervous before taking the stage is completely normal. Even Mark Twain admitted, “There are two types of speakers. Those who get nervous and those who are liars.” So take that flutter in your stomach as a sign you care deeply about delivering value to your audience. In addition, consider the following tips as you prepare to hit the stage.

- Breathe Deep: Before stepping up, take some deep breaths. In through the nose, out through the mouth. Feel every muscle relax with each exhale.

- Mind Over Matter: Visualization is key. Picture yourself nailing that presentation, because if you can see it, you can achieve it.

- Keep It Simple: Stick to what you know best; this isn’t the time for surprises or untested waters.

- Pace Yourself: Speak slowly but surely—there’s no rush here.

Believe it or not, acting relaxed often leads to actually being relaxed. Remember when we said mind over matter? Well, it applies here big time. The power pose backstage might just be what turns those nerves into excitement.

So next time you feel stage fright coming on, fight back with these techniques. With these tricks up your sleeve, you’re more than ready. So go ahead, breathe deep, and step onto that stage. You’ve got this.

Using Different Presentation Methods to Engage Your Audience

While learning styles is “ little more than urban myth ,” presenting your material in a variety of ways is a great technique for engaging your audience. By switching it up, you increase your chances of explaining something in a way that clicks with individual audience members. This is especially helpful for more complex topics that might be hard to grasp.

There are three main ways of presenting your material to your audience: through visuals, audio, and hands-on activities.

- Visuals: Use slides packed with images, graphs, and bullet points.

- Audio: Tell stories, play audio clips or engage in discussions.

- Hands-on Activities: Include activities or demonstrations that allow audience members to participate physically.

Making sure everyone gets something from your presentation means considering these techniques when planning content. Not only can incorporating various methods increase audience engagement, but it can also elevate your presentation from decent to memorable.

Essential Tips for First-Time Presenters

Stepping onto the stage or logging into that webinar platform as a first-time presenter can feel nerve-wracking. But fear not! With these tips on how to dress appropriately, arrive early, and make your presentation shine, you’ll be ready to confidently nail that presentation.

Dress Appropriately

Your outfit is your armor. Choose something professional yet comfortable. Whether it’s in-person or online, dressing one notch above what you expect your audience to wear usually hits the sweet spot. Aim for solid colors that won’t distract your audience.

Arriving Early

If possible, arrive at the venue before your audience does. This gives you time to settle in, test any tech gear like microphones or projectors, and take those deep breaths. This extra time also lets you chat with early birds. By connecting with people before taking center stage, you can ease nerves significantly.

Making Presentation Time Count

You only have the audience’s attention for so long. Keep an eye on the clock as you present, but avoid rushing through content. It especially helps to pause after key points, letting information sink in. Your end goal? Leave you’re audience wanting more. You’ll know if you succeeded based on the number of questions you get during the Q&A.

So there you have it—the techniques you need to deliver an engaging presentation. By honing nonverbal communication, like eye contact and posture, you can captivate your audience with your energy. And visual aids? They’re not just ornamental; they help bolster your point and drive it home.

We also learned that tackling audience questions is not an art reserved for the eloquent few but a skill sharpened by preparation and presence. While it takes a little work to nail good storytelling and well-timed humor, the ultimate outcome is worth it.

So while standing before an audience may set your heart racing, know that arming yourself with knowledge and technique can transform not just your presentation, but you yourself. So don’t be afraid to try your hand at these skills; in doing so, you build your own confidence and become a better speaker in the process.

- Last Updated: April 11, 2024

Explore Related Resources

Learn How You Could Get Your First (Or Next) Paid Speaking Gig In 90 Days or Less

We receive thousands of applications every day, but we only work with the top 5% of speakers .

Book a call with our team to get started — you’ll learn why the vast majority of our students get a paid speaking gig within 90 days of finishing our program .

If you’re ready to control your schedule, grow your income, and make an impact in the world – it’s time to take the first step. Book a FREE consulting call and let’s get you Booked and Paid to Speak ® .

About The Speaker Lab

We teach speakers how to consistently get booked and paid to speak. Since 2015, we’ve helped thousands of speakers find clarity, confidence, and a clear path to make an impact.

Get Started

Let's connect.

Copyright ©2023 The Speaker Lab. All rights reserved.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What It Takes to Give a Great Presentation

- Carmine Gallo

Five tips to set yourself apart.

Never underestimate the power of great communication. It can help you land the job of your dreams, attract investors to back your idea, or elevate your stature within your organization. But while there are plenty of good speakers in the world, you can set yourself apart out by being the person who can deliver something great over and over. Here are a few tips for business professionals who want to move from being good speakers to great ones: be concise (the fewer words, the better); never use bullet points (photos and images paired together are more memorable); don’t underestimate the power of your voice (raise and lower it for emphasis); give your audience something extra (unexpected moments will grab their attention); rehearse (the best speakers are the best because they practice — a lot).

I was sitting across the table from a Silicon Valley CEO who had pioneered a technology that touches many of our lives — the flash memory that stores data on smartphones, digital cameras, and computers. He was a frequent guest on CNBC and had been delivering business presentations for at least 20 years before we met. And yet, the CEO wanted to sharpen his public speaking skills.

- Carmine Gallo is a Harvard University instructor, keynote speaker, and author of 10 books translated into 40 languages. Gallo is the author of The Bezos Blueprint: Communication Secrets of the World’s Greatest Salesman (St. Martin’s Press).

Partner Center

Do Presentation Methods Matter? 5 Ways on How to Present Information

Presentation methods may vary, but the objective remains the same: achieve validation for an idea, proposal or action. However, a presentation’s impact depends on several factors. Chief among them is the choice of which methods to employ.

For instance, will a simple speech with no visual aids be enough to carry your message across? Or, will you need visuals like images, graphs, charts and tables to bolster your ideas?

Studies show lack of preparation is the reason 90% of people experience anxiety before a presentation. To overcome that problem, much thought and preparation should go into a presentation before you ever start on the first slide.

All in all, presentation methods matter when you’re conveying a message. But how that message affects your audience depends greatly on how you communicate your ideas.

Presentation Skills Basics

The art of the presentation covers more than just explaining an idea. Everything you do in front of an audience can influence the way it reacts to your presentation. This is why presenters must stay in control when speaking in front of a group of people.

Any small gesture or unscripted words can cause a distraction. How do you think the audience will react if a speaker keeps yawning while delivering a speech? At the same time, listeners would have trouble keeping up when confronted with slides that are crammed full of text.

Here are some ways to keep the audience engaged throughout your presentation:

Show Enthusiasm When Presenting an Idea

Nothing turns off listeners more than watching a presenter who’s bored with his own show. How do you expect to engage others when you can’t even engage yourself?

To sell an idea, a speaker must first sell themselves. Not only should you know what you’re talking about, but you must also give an air of confidence when sharing your ideas. Combining both attributes can boost a your enthusiasm levels, which can carry over to the audience during the talk.

Control Your Body Language and Mannerisms

Excessive on-stage body movement can distract the audience enough that they stop listening and start watching instead. Remember, communication also involves non-verbal language, so listeners might be tuning into your movements more than they should.

For example, fidgeting on stage can signal nervousness or uncertainty, which the audience might mistake for a lack of confidence. Conversely, acting overly confident and dismissive can come across as negative. The crowd may want to listen and learn, but they don’t want to be lectured.

Keep Things Simple

When discussing an idea or proposal, avoid veering off topic or including so much information that the audience begins to disengage. You should make it simple for listeners to easily grasp what you’re communicating.

Now, this doesn’t mean using friendly terms or talking slowly. What’s more important is the effort you made to understand your audience before your presentation. Are you speaking in front of engineers? Then you should be comfortable using terms and acronyms they’re already familiar with. Are you talking to buyers? Cut down on jargon, focus on solutions and have the numbers ready even before they ask. Knowing your audience and preparing your talk accordingly is a much better approach than simply dialing down your language.

When presenting, focus on the fact that you have a great idea that can benefit many people. Your immediate goal should be to use your limited time to share this exciting idea as enthusiastically and completely as possible without going overboard.

Importance of Presentation Skills

Communication and presentation skills are important assets to have across all industries. Unfortunately, presentation skills are not inherent traits a person is born with. The good news, however, is that they can be easily learned. Even better, with enough practice and continual refinement, anyone can master the various presentation methods.

Skill in Presentation Methods Can Lead to Corporate Success

Many professions rely on skilled presentation methods to get the job done, including teachers, HR trainers and management executives. These positions depend highly on the employee’s ability to communicate with their audiences. Their presentation skills help them master their jobs every day. Sales representatives are no exception.

A salesperson’s career relies on the ability to convert leads into customers. This includes the extraordinary ability to convince buyers that their proposed solution outshines the rest of the field. More importantly, the savvy sales rep should possess presentation skills that are better than their competitors.

The mastery of various presentation methods can lead an employee to earn a distinctive role in the company. Not everybody can keep an audience engaged, informed and entertained at the same time. If you can master this ability, rest assured that your company will create every opportunity to put those skills to the test. Here are specific instances where skilled presentation methods can ensure professional success:

Acing the Job Interview

For many employees, the earliest part of their successful career path started by acing that final job interview. Having sharp presentation skills can immediately set you apart from other candidates and mark you as a potential leader among recruiters.

By mastering various presentation methods, the ideal candidate has demonstrated they have the confidence and the skills to represent the company both within and outside the office walls. As a result, the company is more than happy to add the necessary training and knowledge to develop the candidate into a model employee.

Closing the Deal

Of course, the bulk of a sales representative’s work is convincing the client their solution is better than all others combined. While many companies offer products that check all the buyer’s boxes, how the sales rep positions their solution often plays the definitive part in getting the big yes.

It starts with the sales representative clearly demonstrating the company understands the client’s problem. Then, they offer a solution that dovetails with the specific problems. Finally, mastery of presentation methods allows the sales rep to skillfully handle objections and close the deal.

At some point in their careers, all other non-sales employees will also find the need to act as salespersons to advance the interests of their department. During annual budget meetings, for instance, many employees will be asked to present their department proposals. They’ll need to convince finance bosses and upper management of the importance of their projects to get the budget approvals they need.

Winning Public Opinion

Many people form their opinions of companies based on what they hear or read about them. Skillful presentation methods can also help a company get out of a potential public relations disaster. Even in the midst of a serious problem, a veteran PR person can convey the company’s utmost sincerity in righting a perceived misstep or inaction. In other cases, an enthusiastic presenter armed with an equally great presentation can highlight a company’s social responsibility programs and show that it gives as much as it takes from the community.

Specific Presentation Skills That Are Valuable in the Workplace

Mastering the art of presenting requires a number of talents. Savvy presenters know they can’t rely on content alone. After all, a successful storyteller might have a very interesting tale to tell, but they’ll also need to apply various other skills to make a story stand out and resonate with its listeners. Outside of confidence, here are additional attributes that can enhance a person’s presentation skills:

Public Speaking

All presentation methods involve speaking in front of an audience. Therefore, a basic requirement is public speaking. Those without a love for storytelling or the confidence to talk to strangers will soon find presenting a heavy burden that gets harder to perform every time.

Organization

Another necessary skill to master is the ability to organize thoughts into a coherent and orderly presentation. Like any story, a presentation must have a logical beginning, middle and end. An organized person should have no problems arranging and composing a story that moves in a logical sequence the audience can easily follow. Otherwise, the presentation could become an incoherent mess that’s hard to follow and harder to agree with.

Time Management

Not all audiences have time to endure a 30-minute presentation. The skilled presenter should know the set limit for a presentation and be able to condense their slideshow into a version that fits the allotted time. In some cases, a busy client won’t even have time to sit in a meeting with a seller, so they’ll settle for an elevator pitch . Given that last-second reprieve, the intrepid salesperson should be ready and take that shot.

Empathy With Audiences

By itself, empathy is already a key skill to learn. Applied to the workplace and to presentation methods, this ability becomes even more valuable. It takes a certain kind of talent to master public speaking, and even more so public listening. Being attuned to what the audience feels in certain situations is a great way to steer your presentation in the right direction. For sales presenters, acknowledging your audience’s pain points reinforces the idea that the proposed solution can solve its specific problems.

Sense of Humor

The masterful presenter knows how to laugh with their audience. Adding some light moments to heavy presentations can ease the building tension. It also puts the audience in a better mood to accept new ideas or listen to offered solutions. Of course, jokes and witty humor should always remain within the confines of good taste to remain effective.

Presentation Software Skills

As great presentations require great visual support, skilled presenters know how valuable the right presentation software is. Learning how to operate presentation software to produce awesome content is a valuable skill everybody should strive for.

The Bottom Line: Improved Presentation Methods

Mastering these abilities will sharpen a person’s presentation skills and improve their presentation methods. By applying these attributes to certain situations, they’re more likely to engage the crowd. Ultimately, this can make your audience more receptive to proposed ideas and less resistant to closing a sale.

More importantly, great presentation skills can lead to better relationships with clients. When the client confirms you have their best interests at heart, they can rightly conclude that your solutions can address their specific concerns. Thanks to a mastery of presentation methods, what started as an opportunity to tell a story can turn into a successful long-term partnership.

The Importance of Presentation Skills in Sales

For sales in particular, possessing refined presentation skills means being ready to talk to clients at all times. Admittedly, not all client encounters end on a happy note. But enhancing your sales team’s presentation methods can help them anticipate and deal with every possible uncertainty.

Presentation skills also encourage sales teams to learn more about their prospects. Crafting a unique presentation that caters to their specific requirements means taking the time to listen to and understand clients. Otherwise, they risk creating and sharing a presentation that’s far from what buyers expected.

Finally, presentation skills allow sales teams to collaborate with each other and with other departments like marketing and customer service. Using the right cloud-based presentation software, members can remotely share their expertise in every presentation before it goes to the client.

The Importance of Presentation Skills in Marketing

For marketing, building up presentation skills is equally crucial in achieving the company’s objectives. Digital marketing guru Neil Patel noted that most of the important personality traits found in successful marketers are also found in people with exceptional presentation skills. He added that for marketing personnel, having the right presentation skills can directly help brand efforts.

When presenting before an audience, a savvy marketer can increase brand trust, raise awareness and even drive sales. All it takes is a well-designed, well-crafted and superbly delivered presentation.

Besides, it’s marketing’s job to deliver the finer points to the rest of the organization, including brand reports, market analysis and even customer profiles. Marketing needs to share this information with the sales team so it can focus efforts in the right places.

Additionally, marketing produces the content that’s responsible for promoting the brand and driving demand. With marketing having a great story to tell, they’ll need an equally great presentation to get sales to buy in. Without the requisite presentation skills and methods, sales may not get the entire picture or understand the whole story.

Presentation Methods and Techniques

Like stories, presentations come in different forms and travel in various ways to arrive at an ending. What works for one presentation might not necessarily produce the same effect in another. Some start with an action-packed opening, while others take their sweet time getting to the conclusion. Meanwhile, other presenters prefer delivering a story that’s short, sweet and to the point.

The variety of methods is one of the great things about making a presentation. You can mix and match various techniques to come up with your own unique stories the audience will love.

These are some of the more popular presentation methods and techniques used by many successful presenters over the years:

Start With a Hook

Almost all successful artists will say the first few seconds of a show determine its success. Similarly, a presenter needs to jump-start the conversation immediately or risk losing the audience. Forbes is a bit more merciful on attention spans. The media company reported the average audience member will give a presenter a full 10 minutes before starting to tune them out .

Whether 10 seconds or 10 minutes, a presenter must realize that once onstage, they’re living on borrowed time. They need to engage the audience to keep it in the room until the exciting conclusion.

Starting your presentation by muttering “Thank you for coming” and showing an outline isn’t exactly a crowd-pleaser. Instead, jump-start the session by opening with a story (preferably one related to the topic), a humorous anecdote (similarly related) or a question directed at the audience. Whatever opening you decide on, make sure it can capture a drifting audience’s attention and make it stick around.

If you plan on using a hook to catch your listeners off-guard, make sure the intro remains pertinent to the discussion. Note that an off-topic hook can fall flat without additional relevance. Whatever the hook attempt, just make sure that once you have their attention, you make their time worthwhile.

10/20/30 Presentation

How long should a presentation last? We know 10 minutes is the threshold before audiences begin to peel themselves away from the discussion. But a typically compelling presentation will likely take more than 10 minutes unless it’s a TED Talk . A typical TED Talk runs less than 10 minutes, and organizers have said the 18-minute limit is an absolute cut-off and not an approximation.

Considering a person’s average attention span, former Apple evangelist Guy Kawasaki thought of the 10/20/30 rule when making a presentation. The 10/20/30 rule simply states that an effective presentation should:

- Have 10 slides

- Take less than 20 minutes

- Use a font size smaller than 30 pts

Kawasaki said he originally came up with the rule to prevent an attack of Ménière’s disease, which makes listening to any presentation uncomfortable after a few minutes. As a venture capitalist, he had to listen to an inordinate amount of pitches that often run down the allotted 60 minutes with excessive slides or unnecessary details. For the 10/20/30 rule, a presenter has 10 slides to make his point within 20 minutes. That gives them the remaining 40 minutes to answer any questions or close the deal.

Storytelling

Who doesn’t love hearing stories, especially new ones? Stories have a logical sequence that starts at the origin and ends after a successful resolution of the conflict. In between, the protagonist witnesses the development of conflict and will often arrive at a climactic scene to attempt a resolution.

In telling a story, a presenter usually bridges the narrative with the actual topic to establish relevance. A good, happy ending in the story can also mean happy endings for the audience if it buys the product or uses the offered solution.

Storytelling presentation methods take many forms aside from a heroic journey. They also include nested loops, where a storyteller refers to a story as told to another person. Meanwhile, sparklines describe a real-world situation contrasted with an alternate but more positive scenario. Another story type is the false start, where the hero attempts multiple wrong solutions before ending up with the right one.

Whatever storytelling method a presenter chooses, the presentation story should only take around one and a half minutes to complete. Anything longer or more complicated to narrate might take its toll on a restless audience. Instead of delivering a powerful analogy, listeners might turn against the presenter and the product out of disappointment.

Presentation Styles

Apart from various presentation methods, there are also a number of presentation styles to choose from. Styles are the manners in which a presentation is made. Here are five of the more common and popular presentation styles used by people to effectively convey their desired message. Often, the complexity of a presentation determines the type of presentation style used.

1. Freeform Style

As the name implies, the freeform presentation style relies on the presenter knowing their script well enough to present on the spot. This presentation method is great for speakers who don’t require slideshow backgrounds and aren’t afraid to deliver impromptu speeches.

The freeform style is a great presentation method to use when pressed for time or asked on the spot. However, anybody attempting to deliver a freeform presentation without actually knowing the content details will likely get into trouble as questions start flowing.

2. Visual Style

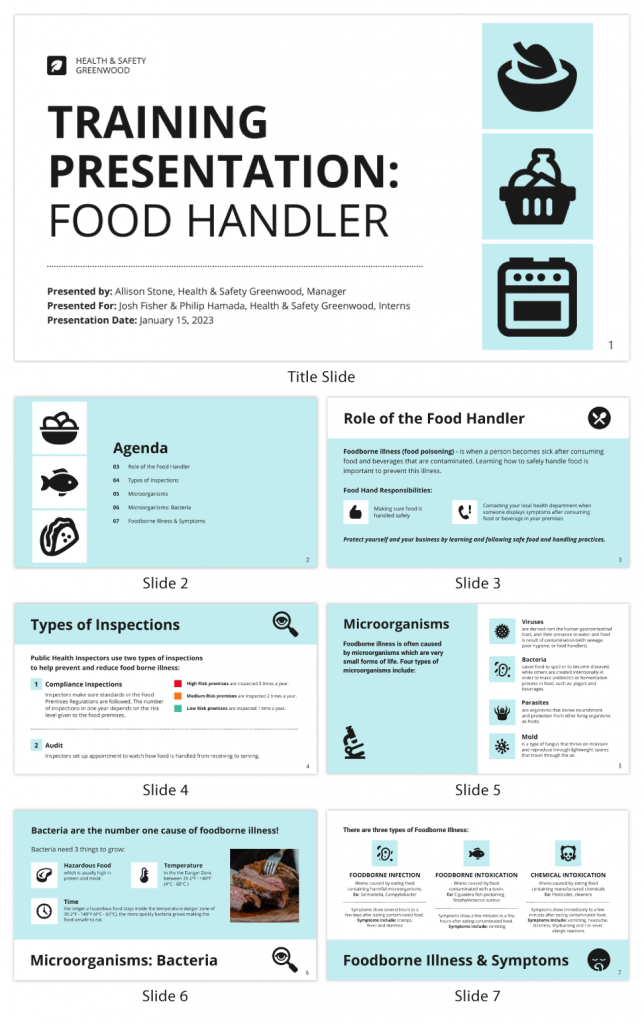

The visual presentation style is the use of graphic elements to support an oral presentation being delivered. This entails the use of slideshow presentation software to display supporting images in the background while the speaker tells the story. Graphs, charts, tables and stock images can enhance the presentation and add more detail to an already informative slideshow.

Visuals are great when explaining complicated topics or ideas that have data points. However, visuals are useless if the presenter’s topic is abstract and short. In these cases, a freeform style is likely what’s needed.

3. Instructor Style

Similar to the visual style, the instructor style takes on complicated presentation topics requiring lots of analogies, figures of speeches and data points. As the presenter aims to educate the audience, the instructor’s style requires a lot of support images as well as a long, instructional oral presentation. Teachers, trainers and coaches often use this presentation style to explain complicated topics or visually show how products, services or processes work.

The instructor presentation style is great to use when you need to go over a complex set of instructions with your audience. However, be careful when applying metaphors and other figures of speech. Using too many analogies might backfire and confuse your audience more. Unless you have thorough knowledge of what’s being presented, you shouldn’t attempt instructor presentations.

4. Lessig Style

Named after Harvard professor and founder of the Center for Internet and Society Lawrence Lessig , the Lessig style is a rapid-paced presentation style geared toward larger audiences. In this style, each slide can stay onscreen for a maximum of 15 seconds. In addition, text will only appear on a slide if it matches the speaker’s exact words.

The Lessig style is an ideal approach to use when making a fast presentation within a specific time limit. The quick pace is great for engaging and educating large audiences. Conversely, the Lessig style won’t work as well with novice presenters who might find the pace too frantic for their experience level.

5. Takahashi Style

The Takahashi style of presentation, named after its proponent Masayoshi Takahashi, is the opposite of graphics-heavy Lessig and visual styles. In fact, there are no visuals found in the Takahashi style of presentations. Instead, text in super large fonts dominates each slide. Users select a keyword to display for every slide.

While innovative, the Takahashi style is more suitable for non-Latin alphabet languages such as Japanese and Korean. Also, most of those who attend a Takahashi-style presentation will need to listen more carefully during the presentation due to the lack of supporting visuals.

Why Choosing the Right Presentation Methods Is Important

Matching the presentation with the presentation style is important. It takes time to develop an actual, effective slideshow. And if you happen to choose the wrong format when developing a presentation, you could find yourself either lacking content to display or severely in need of additional slides.

For example, applying the Takahashi style to an instructor-style presentation can backfire badly . Instructor presentations require a steady stream of visuals such as graphs, tables, charts and images. However, the Takahashi style doesn’t use images in the presentation. Another example would be insisting on applying a Lessig style of presentation to freeform presentations, which don’t require visual backgrounds.

How to Choose the Right Presentation Style

To avoid making costly mistakes, always check the presentation requirements first. Determine if your presentation requires visuals, images or simply supportive background. Then, consider the length and complexity of your presentation. When speaking, will you need more than 15 seconds per slide? If yes, you can eliminate rapid-pace styles like Lessig and freeform and instead focus on visual-rich styles.

You’ll also need to consider your audience before finalizing the style to use. Do listeners need detailed information to appreciate your presentation better? Or, have they heard you present before and somewhat know what you’re talking about? The answer to both questions can help determine whether you need a rapid-fire presentation method or an explainer style that’s heavy on visuals.

Finally, think about how you plan to end the presentation. The call to action can also influence the style required. For instance, pitching for funding or asking the crowd to buy your product will require lots of charts and data proof for your thesis. But for raising brand awareness or increasing your brand visibility, a session of compelling storytelling can do the trick.

Best Practices for Creating a Powerful Presentation

Creating a presentation shouldn’t be a heavy burden, especially when dealing with topics you and your team are very familiar with. Use these popular practices to bring together the best elements for your next presentation:

Present Problems, Then Show Solutions

As a solutions provider, the audience will expect you to be familiar with its problems. Otherwise, it wouldn’t bother showing up to your presentation. By acknowledging a customer’s pain points and tying them to your offered solutions, you can increase the perceived value of your product or service.

Getting to the root of the audience’s pain points will require heavy research prior to your talk. An exploratory interview can help determine the right people to talk to about their challenges. Once you identify them, have a quick meeting to learn more about their concerns.

However, start in-depth discussions about potential solutions with your team only after you’re sure you understand the client’s predicament. Then, before adopting a solution, have your team attack each proposal to see if they’ll stand to scrutiny. As a result, you’ll come to the next meeting ready and confident the solutions you propose tailor-fit the specific problems the client is facing.

Did you notice that, throughout the process, the word “selling” was never mentioned? That’s because buying will occur naturally once the audience realizes what you have is exactly what it needs.

Be a Showman in Your Presentation

Being a showman doesn’t necessarily mean including a song-and-dance routine in your scheduled pitch. However, making an impact and getting engagement means creating a lasting impression that should linger well after the presentation.

The secret to making a killer presentation is plain old prep work. If you know the information like the back of your hand, you’ll have no problem presenting your case, even among objections and skeptics. Knowing your stuff can also give you a massive boost of confidence, as you can repeatedly get back on track despite a myriad of distractions. In a room full of expectant audience members, stay confident and project a calm and collected but passionate attitude. You’ll know you’ve made it when the crowd sees you as someone genuinely interested in helping others solve a problem.

Additionally, stay aware of your presentation limits. If you have a strict time allotment, make sure you use an applicable presentation method like a 10/20/30 or a controlled but engaging storytelling session.

Being a showman means having the audience buy into your ideas. By keeping listeners interested in the presentation contents, they’re more likely to recognize your proposal’s value and accept your solution.

Believe in Your Product

Being a pitchman who’s not confident about your product is a losing proposition. You should be the biggest, most excited kid in the room when it comes to showing off what you have to offer. The moment you reveal your product, the audience should stop seeing you as a salesperson and instead see you as a solutions provider.

However, be careful when acting as a product evangelist. Your belief in your product should be authentic and not something motivated by a desire to close a deal. Audiences can spot a shill easily, and pretending can seriously hamper your efforts to come across as genuinely interested in solving their problems.

Engage Your Audience

Engaging your audience doesn’t mean telling it what it wants to hear. Your choice of presentation methods and styles will greatly affect how your audience reacts to everything you say. So if you took the time to learn what can engage your clients, then you’ll find it even easier to connect with them while you’re onstage.

Audience engagement also means keeping clients in the conversation instead of staying locked in a monologue. Ask audience members questions and let them share experiences. Keep the conversation flowing in the direction that ends with you providing a solution.

Finally, engaging means getting the audience to see things your way before arriving at the conclusion. The trick in doing so lies in two things: how prepared your story is, and how prepared the audience is to listen to that story. Your knowledge of the client’s problems, your confidence in the solution and your genuine interest in helping combine to make your presentation engaging, memorable and productive.

How Tools Help Improve Your Presentation Methods

The tools you use to build your story can help the audience buy into your ideas. For instance, in some cases, a client’s busy schedule means they can only view your presentation on their own time rather than hearing you deliver it in person. If you use the right tools when creating your presentation , then you shouldn’t be afraid of losing your advantage.

Choosing cloud-based interactive presentation software lets you develop a presentation that tells the story in the manner you want it to. Interactive elements allow you to add details that show up when the viewer performs an action. It also helps if you make your presentation dynamic and enable viewers to move back and forth between different sections when reading. That way, they can revisit certain areas and ideas to validate your points. More importantly, it allows for better-looking and more engaging content .

During the development, collaboration features allow you to get input from your team members remotely. Working jointly on a presentation now means logging into a cloud app instead of having an all-nighter at the office. With easier collaboration comes more efficient ways to share ideas and make improvements .

More Tips and Tricks to Help Develop Your Presentation Methods

A presenter is only as good as their last presentation. So, there’s definitely work needed to be done to keep your presentation skills fresh, relevant and engaging.

Practice and Polish

Perfecting your presentation methods requires you to sharpen your skills every chance you get. It also means you’ll have to put in additional work to improve the output of every presentation.

Continuous improvements also mean taking the time to polish your work before sending presentations off to clients. Having your peers review and make comments or suggestions can help you see things you previously didn’t notice. That’s why additional pairs of eyes should always be appreciated when they’re available.

Watch Other Presenters

To become a master in any craft, you must start as a student. Even if you’re already a seasoned presenter, you can’t go wrong looking up other notable presenters and learning how they captivate an audience or save a doomed presentation at the last minute. For the presentation scholar, listening to great speeches from the past can give you ideas on how master orators can keep an audience hanging onto every word.

Take Advantage of Technology

Making use of existing tech tools can give you an edge when competing for attention with your rivals. For example, use cloud-based interactive presentation software to breathe more life into the stories you tell. In addition, take advantage of collaboration and productivity software to share your work with your team and get their input.

Upgrade Your Presentation Methods With Ingage

Presenting is a skill many people desire to have but few want to work on. Selling an idea is easier if you know your audience and are aware of its problems. More importantly, you should believe in your solutions and confidently stand by them. To show the world all this knowledge requires awesome presentation skills and mastery of various presentation methods. While research and practice make perfect, using modern tools can also help improve your presentation skills.

Ingage is cloud-based interactive presentation software that helps you and your team create engaging content for your clients. Collaboration features allow you to remotely share your work with your team so you can jointly develop the presentation. Once finished, simply send the presentation link to your clients so they can view the pitch at their leisure.

Ingage’s analytics features also allow you to track viewer responses to your presentation. In addition, it can tell you which sections resonated with your audience and which areas need improvement.

Let Ingage turn your presentations into engaging, compelling stories clients can relate to. Contact us today, and we’ll be happy to arrange a free demonstration .

- BEGINNER TRAINING

- ADVANCED PRESENTATION TRAINING

- CORPORATE PRESENTATION TRAINING

- PRESENTATION SKILLS COACHING

- TRAINING OUTLINE

- PRESENTATION REFRESHER

- REFER A COLLEAGUE

- PRESENTATION REHEARSAL

- PRESENTATION REVIEW

- PRESENTATION SEMINAR

- ADVANCED TRAINING

- CORPORATE TRAINING

- ONLINE COURSE

- PUBLIC SPEAKING COACHING

- PUBLIC SPEAKING REFRESHER

- SPEECH REHEARSAL

- EFFECTIVE PRESENTATION TIPS

- CONFIDENT PRESENTATION TIPS

- SUCCESSFUL PRESENTATION TIPS

- PRESENTATION DESIGN TIPS

- PUBLIC SPEAKING TIPS

- TIPS FOR SPEAKERS

- PRESENTATION VIDEOS

- Presentation Methods For Your Success

- Presentation Tips You Should Know

Your choice of presentation methods says something about you. And if that sounds just a little bit scary, then it's not intended to be! Because everything you do as a presenter says something to the audience. That's really what a presentation is all about. It's a means for communication between you and your audience. Your job is to make sure that you convey the right set of messages….the messages you really want to transfer.

Your Presentation Methods Are Really Important

Thus your choice of presentation method might suggest the following:

- How well-practised are you?

- Do you know your material?

- What do you know about your audience?

Your audience will notice and will respond accordingly. But, that's not a problem, because your choice of presentation method is influenced by all three.

Presentation Methods: It's Your Choice

Do you know your audience really well? So take inspiration. Try to break the bounds of PowerPoint or Keynote. It might possibly encourage you to try out newer presentation manager alternatives such as Prezi presentation software . There are some good alternatives to PowerPoint out there. So this list shows off the presentation features of more than 20 of them.

Therefore, your choice of presentation methods reflects your earlier preparation and your research.

Because when you know your material and your audience, you will have more options for an effective presentation.

As a result, and more importantly, you will have more control over the presentation methods you use.

A Less-Practised Presenter

A less-practised presenter might use presentation software as a crutch. That’s because they don’t have a good knowledge of their material. So, they use the software to help them get by with their presentation. They might not know their material too well. Or, possibly they haven’t had much time to prepare, practise and rehearse. PowerPoint might help to give them security as it hides the gaps in their work. That’s the theory. However, most audiences can see through this.

A Well-Practised Presenter

A well-practised presenter might choose to use PowerPoint or Keynote for their presentation. So they emphasise key points with some multimedia in their presentation’s slides. Their PowerPoint presentation is visually emphatic. And their slides are clear and consistent. Additionally, their organisation is ordered. And, because of this, their presentation is more effective.

What Presentation Methods Can You Use?

You have a range of presentation methods to choose from. You might use some as a crutch, but others will definitely boost your presentation performance.

- Use PowerPoint .

- Take advantage of Keynote or PowerPoint For Mac.

- Try one of the many PowerPoint alternatives. We've listed some alternatives to PowerPoint in this article.

- Use props , a flip-chart or whiteboard. Here are some tips for using a prop when giving a presentation .

You can learn more presentation skills and techniques on a public presentation training course . Because we organise our courses to a regular schedule, there’s something for everyone. Or, when you want a more intensive approach, then you can always try individual presentation coaching . Whatever your approach, please don’t hesitate to get in touch when the time is right.

“PowerPoint is popular only because it helps disorganized presenters feel more organized.”

Edward Tufte

Related Tips

5 ways to a fully prepared presentation, what’s the purpose of a presentation what you need to know, how to handle feedback after your presentation, grow in confidence with these office party presentation skills, how to be a dynamic communicator with your presentations, 10 ways to improve your powerpoint presentation skills, how to finish your presentation with a bang, how you can achieve a title effect for your next presentation, how to point, turn and talk with powerpoint, how to be a confident presenter with better rehearsal skills, how to take questions during a presentation, how to manage time as a presenter, join our mailing list to get the latest updates.

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

A Guide to The Techniques of Presentation

Hrideep barot.

- Body Language & Delivery , Presentation , Public Speaking , Workplace Communication

We’re guessing you are here because you’re either tired of having sweaty palms before giving a presentation or you have vowed to become the Steve Jobs of presentations!

Whatever be your motto, we have sworn to not leave you without guiding you through the numerous techniques of presentation.

Presentation Techniques are all the essential skills you ought to develop to deliver presentations successfully and become a better presenter. Presentation techniques include focusing on the audience, cutting down to the core idea, brainstorming, using visual aids, the 10-20-30 rule, structuring, recording yourself, practice and feedback, and open body language.

We are going to discuss these techniques in detail in the upcoming sections.

Techniques of Creation

A successful presentation requires a good amount of brainstorming and planning before D-Day dawns. Here are techniques you can focus on to create a stellar presentation.

1. The Topic at Hand

This involves first and foremost choosing a subject or topic to present on.

Why choose a topic that interests you?

If you have the liberty to choose a topic according to your liking, see that it is one that you are passionate about . This will help you look forward to the preparation as well as delivery because it is something you believe so much in.

But what if you have no choice?

However, if the situation is such that you do not like the topic or it is particularly boring, then don’t dread it yet. You can always tweak it by bringing in humor , using a case study , narrating a story , or a personal anecdote relating to the topic.

How to make a boring topic interesting?

Find fun ways to bring your topic to life. Your presentation need not be restricted to you speaking and showing some visuals. You can be unconventional (Like Dr. Jill Bolte-Taylor was when she got an actual human brain on stage during her TED talk!) and make use of sound and video, physical props, or audience engagement activities .

For example, at the beginning of one presentation, a speaker gave out the letters T, E, And M to members of the audience. Towards the end, the speaker highlighted how little difference the letters made individually but when put together, they made a team.

This shows how simple props can be used to give out a powerful message that generates a great connection through a memorable activity.

2. The Audience

What do you need to know about them?

Form an image of your typical audience member in your head. Jot down things like their psychographic information such as their interests, values, traits, etc. List down their expectations and your aim – to inform, inspire, entertain or prove, persuade and demonstrate.

This will enable you to tailor your presentation in a way that you can make the audience achieve what you have for them in your mind. Find out how much they know about your topic, then cater your talk, and the language you use to deliver it in accordance with their level and familiarity with the topic. Best to keep the jargon off the stage.

How can you know get to know them?

If you are presenting at your workplace, you already will have an idea about the interest and values of your colleagues. You can always get to know more about them by sharing your topic with them and asking their opinions on it.

If you are to present in a new setting, try arriving a bit ahead of time and engage yourself in conversation with the audience members by greeting them, introducing yourself, and having a casual conversation over a range of topics.

Be prepared to also face any objections or resistance to your subject and think of ways you can address them in case they arise.

When you have an idea of what they know, believe, and feel about your topic before you present, you can control what they know, believe, and feel about your topic after you are done presenting.

3. Brainstorming

The next thing is to jot down all ideas you have about that topic. Mindmapping is especially helpful when it comes to this. It means sketching out ideas from a central theme, like the branches of a tree.