Political Parties in the United States Essay

The two-party system in the United States has been historically dominant for a variety of reasons. Firstly, most prominent political issues in the United States, starting with the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, typically had two sides to them, lending themselves to the two-party split (Harrison 281). Secondly, the two-party system has been fueled by the winner-take-all nature of the elections in the U.S., as opposed to the proportional representation system present in many other countries (Harrison 282). Thirdly, the election system has been created by the members of the two dominant parties, which makes it difficult for any third-party candidate to gain traction (Harrison 284). These can be summed up as the main reasons for the historical prevalence of the two-party system.

A certain argument can be made regarding whether there is currently a sixth-party system. The fifth-party system is said to have ended in 1968 with the election of Richard Nixon (Harrison 277). The previous party systems have been characterized by the dominance of one party over the other. In comparison, the main aspects of the post-Nixon election period are “intense party competition” and “a divided government” (Harrison 277). These distinctions could indicate that there is currently a sixth-party system.

The new developments in technology have notably shifted the political landscape in the U.S. Both parties employ big data to gather information about the attitudes of their voters in order to better potential target supporters (Harrison 291). Moreover, with the parties making an effort to communicate with the population via social media and mobile apps, the focus of political networking seems to have shifted to these new channels (Harrison 291). These are the changes in how the parties interact with their constituents.

Recent polls have shown low approval for President Joe Biden. Certain “fundamentalists” have claimed that based on these findings and other fundamentals, such as previous election results, the most likely outcome of the Congress elections would be a Democratic loss (Silver). However, despite being based on statistics, this approach has several flaws. Although certain Democrats disapprove of Biden (The Economist), it is unlikely that they would vote for Republicans in Congress (Silver). Moreover, other statistical evidence points out that “presidential approval and the race for Congress have diverged, not converged” (Silver). These are the main reasons why “fundamentalists” could be right or wrong regarding their prediction.

Works Cited

Harrison, Brigid C., et al. American Democracy Now . 6th ed., McGraw-Hill Education, 2019.

Silver, Nate. “ Biden Is Very Unpopular. It May Not Tell Us Much about the Midterms. ” FiveThirtyEight , 2022. Web.

“Why Young Democrats Disapprove of Joe Biden.” The Economist , 2022. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, December 14). Political Parties in the United States. https://ivypanda.com/essays/political-parties-in-the-united-states/

"Political Parties in the United States." IvyPanda , 14 Dec. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/political-parties-in-the-united-states/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Political Parties in the United States'. 14 December.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Political Parties in the United States." December 14, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/political-parties-in-the-united-states/.

1. IvyPanda . "Political Parties in the United States." December 14, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/political-parties-in-the-united-states/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Political Parties in the United States." December 14, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/political-parties-in-the-united-states/.

- Ethics in Technology for the Information Age

- Electoral College's Advantages and Disadvantages

- Converged Media: Legal, Economic, and Behavioural Impact

- Is the UK still a two-party system?

- Two-Party System Relevance: 2010 Australian Federal Election

- Two-Party System Rise in 1796-1840 in the US

- US History to 1877: Two-Party System Development

- Quality Manuals in Orbital Traction

- Google Inc.'s Competitive Advantage and Future

- Power and Social Change in the Election System

- Public Interest in Parliamentary Law Making

- Colorado and Statewide Political Culture

- Instruments of Statecraft in Australian Foreign Policy

- Western Ideology vs. Political Islam in Turkey

- Analysis of the Political Frame Skills

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.1 History of American Political Parties

Learning objectives.

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What is a political party?

- What were James Madison’s fears about political factions?

- How did American political parties develop?

- How did political machines function?

Political parties are enduring organizations under whose labels candidates seek and hold elective offices (Epstein, 1986). Parties develop and implement rules governing elections. They help organize government leadership (Key Jr., 1964). Political parties have been likened to public utilities, such as water and power companies, because they provide vital services for a democracy.

The endurance and adaptability of American political parties is best understood by examining their colorful historical development. Parties evolved from factions in the eighteenth century to political machines in the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, parties underwent waves of reform that some argue initiated a period of decline. The renewed parties of today are service-oriented organizations dispensing assistance and resources to candidates and politicians (Aldrich, 1995; Eldersveld & Walton Jr., 2000).

The Development of Political Parties

A timeline of the development of political parties can be accessed at http://www.edgate.com/elections/inactive/the_parties .

Fear of Faction

The founders of the Constitution were fearful of the rise of factions, groups in society that organize to advance a political agenda. They designed a government of checks and balances that would prevent any one group from becoming too influential. James Madison famously warned in Federalist No. 10 of the “mischiefs of faction,” particularly a large majority that could seize control of government (Publius, 2001). The suspicion of parties persisted among political leaders for more than a half century after the founding. President James Monroe opined in 1822, “Surely our government may go on and prosper without the existence of parties. I have always considered their existence as the curse of the country” (Hofstadter, 1969).

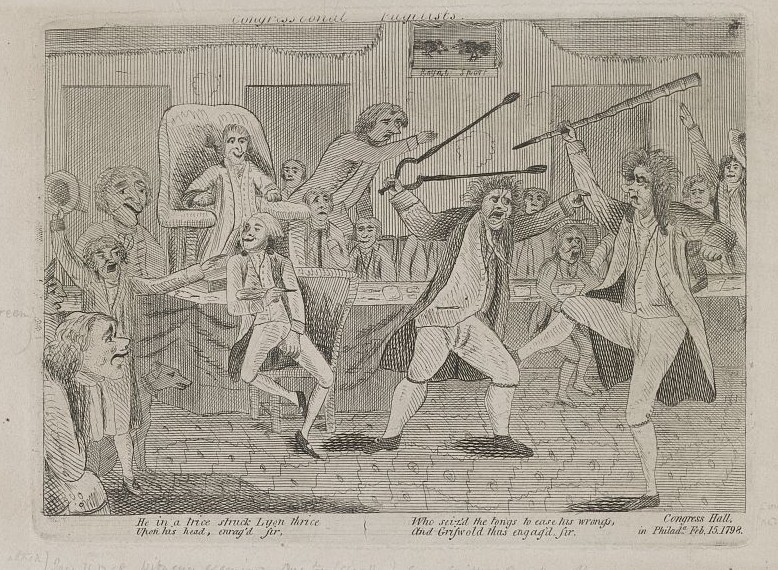

Figure 10.1

<<a href="/app/uploads/sites/193/2016/10/533c8686f8d280ce42699201aeb7f938.jpg">img src=”https://open.lib.umn.edu/app/uploads/sites/193/2016/10/533c8686f8d280ce42699201aeb7f938.jpg” width=”300″ alt=”A newspaper cartoon depicting conflicts that arose between the Federalists and Republicans, who sought to control the government.”/>

Newspaper cartoons depicted conflicts that arose between the Federalists and Republicans, who sought to control government.

Source: http://www.vermonthistory.org/freedom_and_unity/new_frontier/images/cartoon.gif .

Despite the ambiguous feelings expressed by the founders, the first modern political party, the Federalists, appeared in the United States in 1789, more than three decades before parties developed in Great Britain and other western nations (Chambers & Burnham, 1975). Since 1798, the United States has only experienced one brief period without national parties, from 1816 to 1827, when infighting following the War of 1812 tore apart the Federalists and the Republicans (Chambers, 1963).

Parties as Factions

The first American party system had its origins in the period following the Revolutionary War. Despite Madison’s warning in Federalist No. 10, the first parties began as political factions. Upon taking office in 1789, President George Washington sought to create an “enlightened administration” devoid of political parties (White & Shea, 2000). He appointed two political adversaries to his cabinet, Alexander Hamilton as treasury secretary and Thomas Jefferson as secretary of state, hoping that the two great minds could work together in the national interest. Washington’s vision of a government without parties, however, was short-lived.

Hamilton and Jefferson differed radically in their approaches to rectifying the economic crisis that threatened the new nation (Charles, 1956). Hamilton proposed a series of measures, including a controversial tax on whiskey and the establishment of a national bank. He aimed to have the federal government assume the entire burden of the debts incurred by the states during the Revolutionary War. Jefferson, a Virginian who sided with local farmers, fought this proposition. He believed that moneyed business interests in the New England states stood to benefit from Hamilton’s plan. Hamilton assembled a group of powerful supporters to promote his plan, a group that eventually became the Federalist Party (Hofstadter, 1969).

The Federalists and the Republicans

The Federalist Party originated at the national level but soon extended to the states, counties, and towns. Hamilton used business and military connections to build the party at the grassroots level, primarily in the Northeast. Because voting rights had been expanded during the Revolutionary War, the Federalists sought to attract voters to their party. They used their newfound organization for propagandizing and campaigning for candidates. They established several big-city newspapers to promote their cause, including the Gazette of the United States , the Columbian Centinel , and the American Minerva , which were supplemented by broadsheets in smaller locales. This partisan press initiated one of the key functions of political parties—articulating positions on issues and influencing public opinion (Chambers, 1963).

Figure 10.2 The Whiskey Rebellion

Farmers protested against a tax on whiskey imposed by the federal government. President George Washington established the power of the federal government to suppress rebellions by sending the militia to stop the uprising in western Pennsylvania. Washington himself led the troops to establish his presidential authority.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WhiskeyRebellion.jpg .

Disillusioned with Washington’s administration, especially its foreign policy, Jefferson left the cabinet in 1794. Jefferson urged his friend James Madison to take on Hamilton in the press, stating, “For God’s sake, my Dear Sir, take up your pen, select your most striking heresies, and cut him to pieces in the face of the public” (Chambers, 1963). Madison did just that under the pen name of Helvidius. His writings helped fuel an anti-Federalist opposition movement, which provided the foundation for the Republican Party. This early Republican Party differs from the present-day party of the same name. Opposition newspapers, the National Gazette and the Aurora , communicated the Republicans’ views and actions, and inspired local groups and leaders to align themselves with the emerging party (Chambers, 1963). The Whiskey Rebellion in 1794, staged by farmers angered by Hamilton’s tax on whiskey, reignited the founders’ fears that violent factions could overthrow the government (Schudson, 1998).

First Parties in a Presidential Election

Political parties were first evident in presidential elections in 1796, when Federalist John Adams was barely victorious over Republican Thomas Jefferson. During the election of 1800, Republican and Federalist members of Congress met formally to nominate presidential candidates, a practice that was a precursor to the nominating conventions used today. As the head of state and leader of the Republicans, Jefferson established the American tradition of political parties as grassroots organizations that band together smaller groups representing various interests, run slates of candidates for office, and present issue platforms (White & Shea, 2000).

The early Federalist and Republican parties consisted largely of political officeholders. The Federalists not only lacked a mass membership base but also were unable to expand their reach beyond the monied classes. As a result, the Federalists ceased to be a force after the 1816 presidential election, when they received few votes. The Republican Party, bolstered by successful presidential candidates Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, was the sole surviving national party by 1820. Infighting soon caused the Republicans to cleave into warring factions: the National Republicans and the Democratic-Republicans (Formisano, 1981).

Establishment of a Party System

A true political party system with two durable institutions associated with specific ideological positions and plans for running the government did not begin to develop until 1828. The Democratic-Republicans, which became the Democratic Party, elected their presidential candidate, Andrew Jackson. The Whig Party, an offshoot of the National Republicans, formed in opposition to the Democrats in 1834 (Holt, 2003).

The era of Jacksonian Democracy , which lasted until the outbreak of the Civil War, featured the rise of mass-based party politics. Both parties initiated the practice of grassroots campaigning, including door-to-door canvassing of voters and party-sponsored picnics and rallies. Citizens voted in record numbers, with turnouts as high as 96 percent in some states (Holt, 2003). Campaign buttons publically displaying partisan affiliation came into vogue. The spoils system , also known as patronage, where voters’ party loyalty was rewarded with jobs and favors dispensed by party elites, originated during this era.

The two-party system consisting of the Democrats and Republicans was in place by 1860. The Whig Party had disintegrated as a result of internal conflicts over patronage and disputes over the issue of slavery. The Democratic Party, while divided over slavery, remained basically intact (Holt, 2003). The Republican Party was formed in 1854 during a gathering of former Whigs, disillusioned Democrats, and members of the Free-Soil Party, a minor antislavery party. The Republicans came to prominence with the election of Abraham Lincoln.

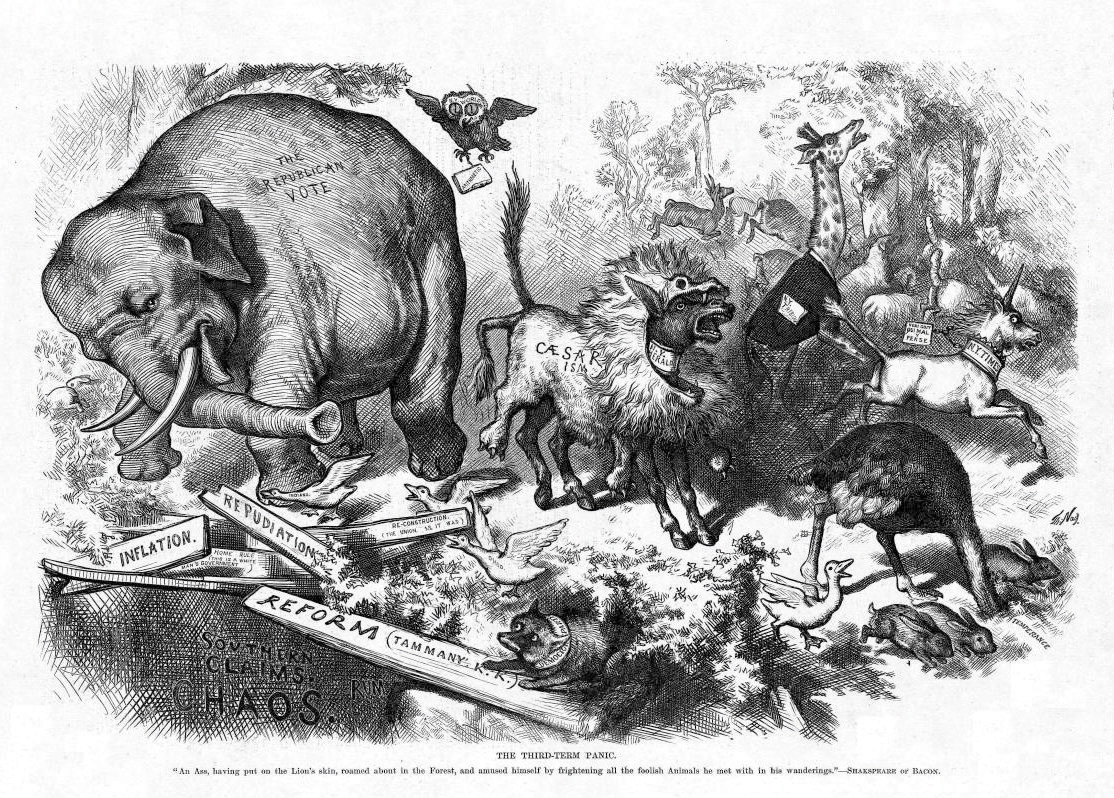

Figure 10.3 Thomas Nast Cartoon of the Republican Elephant

The donkey and the elephant have been symbols of the two major parties since cartoonist Thomas Nast popularized these images in the 1860s.

Source: Photo courtesy of Harper’s Weekly , http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NastRepublicanElephant.jpg .

Parties as Machines

Parties were especially powerful in the post–Civil War period through the Great Depression, when more than 15 million people immigrated to the United States from Europe, many of whom resided in urban areas. Party machines , cohesive, authoritarian command structures headed by bosses who exacted loyalty and services from underlings in return for jobs and favors, dominated political life in cities. Machines helped immigrants obtain jobs, learn the laws of the land, gain citizenship, and take part in politics.

Machine politics was not based on ideology, but on loyalty and group identity. The Curley machine in Boston was made up largely of Irish constituents who sought to elect their own (White & Shea, 2000). Machines also brought different groups together. The tradition of parties as ideologically ambiguous umbrella organizations stems from Chicago-style machines that were run by the Daley family. The Chicago machine was described as a “hydra-headed monster” that “encompasses elements of every major political, economic, racial, ethnic, governmental, and paramilitary power group in the city” (Rakove, 1975). The idea of a “balanced ticket” consisting of representatives of different groups developed during the machine-politics era (Pomper, 1992).

Because party machines controlled the government, they were able to sponsor public works programs, such as roads, sewers, and construction projects, as well as social welfare initiatives, which endeared them to their followers. The ability of party bosses to organize voters made them a force to be reckoned with, even as their tactics were questionable and corruption was rampant (Riechley, 1992). Bosses such as William Tweed in New York were larger-than-life figures who used their powerful positions for personal gain. Tammany Hall boss George Washington Plunkitt describes what he called “honest graft”:

My party’s in power in the city, and its goin’ to undertake a lot of public improvements. Well, I’m tipped off, say, that they’re going to lay out a new park at a certain place. I see my opportunity and I take it. I go to that place and I buy up all the land I can in the neighborhood. Then the board of this or that makes the plan public, and there is a rush to get my land, which nobody cared particular for before. Ain’t it perfectly honest to charge a good price and make a profit on my investment and foresight? Of course, it is. Well, that’s honest graft (Riordon, 1994).

Enduring Image

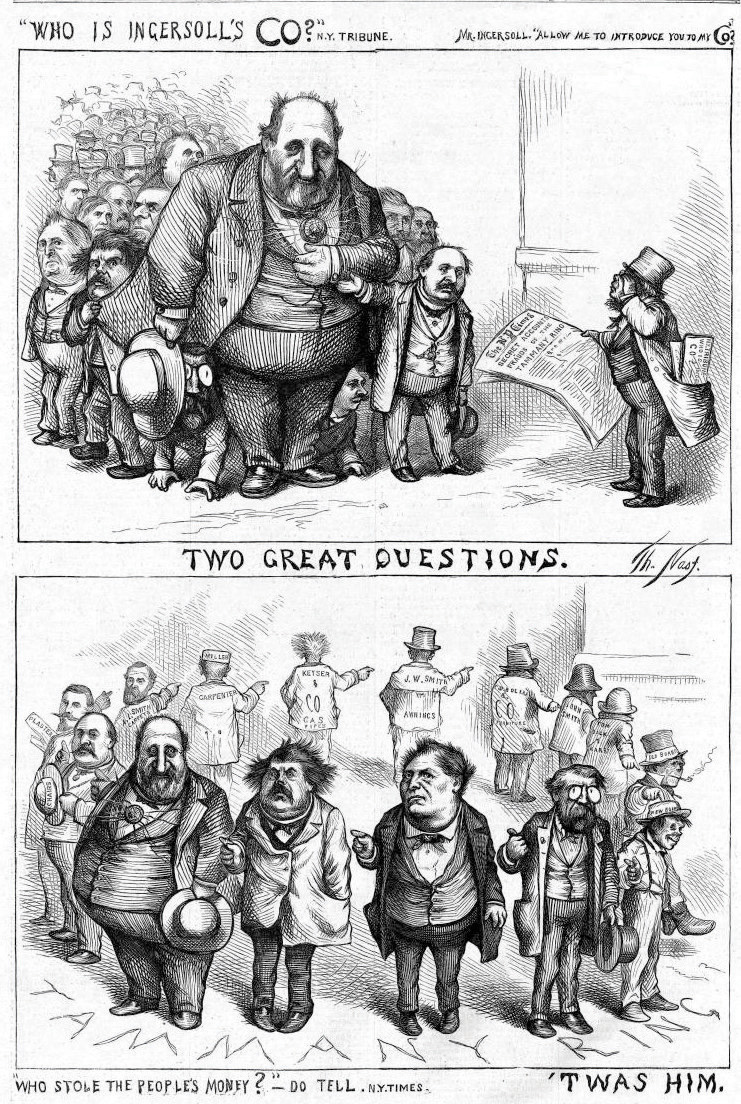

Boss Tweed Meets His Match

The lasting image of the political party boss as a corrupt and greedy fat cat was the product of a relentless campaign by American political cartoonist Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly from 1868 to 1871. Nast’s target was William “Boss” Tweed, leader of the New York Tammany Hall party machine, who controlled the local Democratic Party for nearly a decade.

Nast established the political cartoon as a powerful force in shaping public opinion and the press as a mechanism for “throwing the rascals” out of government. His cartoons ingrained themselves in American memories because they were among the rare printed images available to a wide audience in a period when photographs had not yet appeared in newspapers or magazines, and when literacy rates were much lower than today. Nast’s skill at capturing political messages in pictures presented a legacy not just for today’s cartoonists but for photographers and television journalists. His skill also led to the undoing of Boss Tweed.

Tweed and his gang of New York City politicians gained control of the local Democratic Party by utilizing the Society of Tammany (Tammany Hall), a fraternal organization, as a base. Through an extensive system of patronage whereby the city’s growing Irish immigrant population was assured employment in return for votes, the Tweed Ring was able to influence the outcome of elections and profit personally from contracts with the city. Tweed controlled all New York state and city Democratic Party nominations from 1860 to 1870. He used illegal means to force the election of a governor, a mayor, and the speaker of the assembly.

The New York Times , Harper’s Weekly , reform groups, and disgruntled Democrats campaigned vigorously against Tweed and his cronies in editorials and opinion pieces, but none was as successful as Nast’s cartoons in conveying the corrupt and greedy nature of the regime. Tweed reacted to Nast’s cartoon, “Who Stole the People’s Money,” by demanding of his supporters, “Stop them damned pictures. I don’t care what the papers write about me. My constituents can’t read. But, damn it, they can see pictures” (Kandall, 2011).

“Who Stole the People’s Money.” Thomas Nast’s cartoon, “Who Stole the People’s Money,” implicating the Tweed Ring appeared in Harper’s Weekly on August 19, 1871.

Source: Photo courtesy of Harper’s Weekly , http://www.harpweek.com/09cartoon/BrowseByDateCartoon-Large.asp?Month=August&Date=19 .

The Tweed Ring was voted out in 1871, and Tweed was ultimately jailed for corruption. He escaped and was arrested in Spain by a customs official who didn’t read English, but who recognized him from the Harper’s Weekly political cartoons. He died in jail in New York.

Parties Reformed

Not everyone benefited from political machines. There were some problems that machines either could not or would not deal with. Industrialization and the rise of corporate giants created great disparities in wealth. Dangerous working conditions existed in urban factories and rural coal mines. Farmers faced falling prices for their products. Reformers blamed these conditions on party corruption and inefficiency. They alleged that party bosses were diverting funds that should be used to improve social conditions into their own pockets and keeping their incompetent friends in positions of power.

The Progressive Era

The mugwumps, reformers who declared their independence from political parties, banded together in the 1880s and provided the foundation for the Progressive Movement . The Progressives initiated reforms that lessened the parties’ hold over the electoral system. Voters had been required to cast color-coded ballots provided by the parties, which meant that their vote choice was not confidential. The Progressives succeeded by 1896 in having most states implement the secret ballot. The secret ballot is issued by the state and lists all parties and candidates. This system allows people to split their ticket when voting rather than requiring them to vote the party line. The Progressives also hoped to lessen machines’ control over the candidate selection process. They advocated a system of direct primary elections in which the public could participate rather than caucuses , or meetings of party elites. The direct primary had been instituted in only a small number of states, such as Wisconsin, by the early years of the twentieth century. The widespread use of direct primaries to select presidential candidates did not occur until the 1970s.

The Progressives sought to end party machine dominance by eliminating the patronage system. Instead, employment would be awarded on the basis of qualifications rather than party loyalty. The merit system, now called the civil service , was instituted in 1883 with the passage of the Pendleton Act. The merit system wounded political machines, although it did not eliminate them (Merriam & Gosnell, 1922).

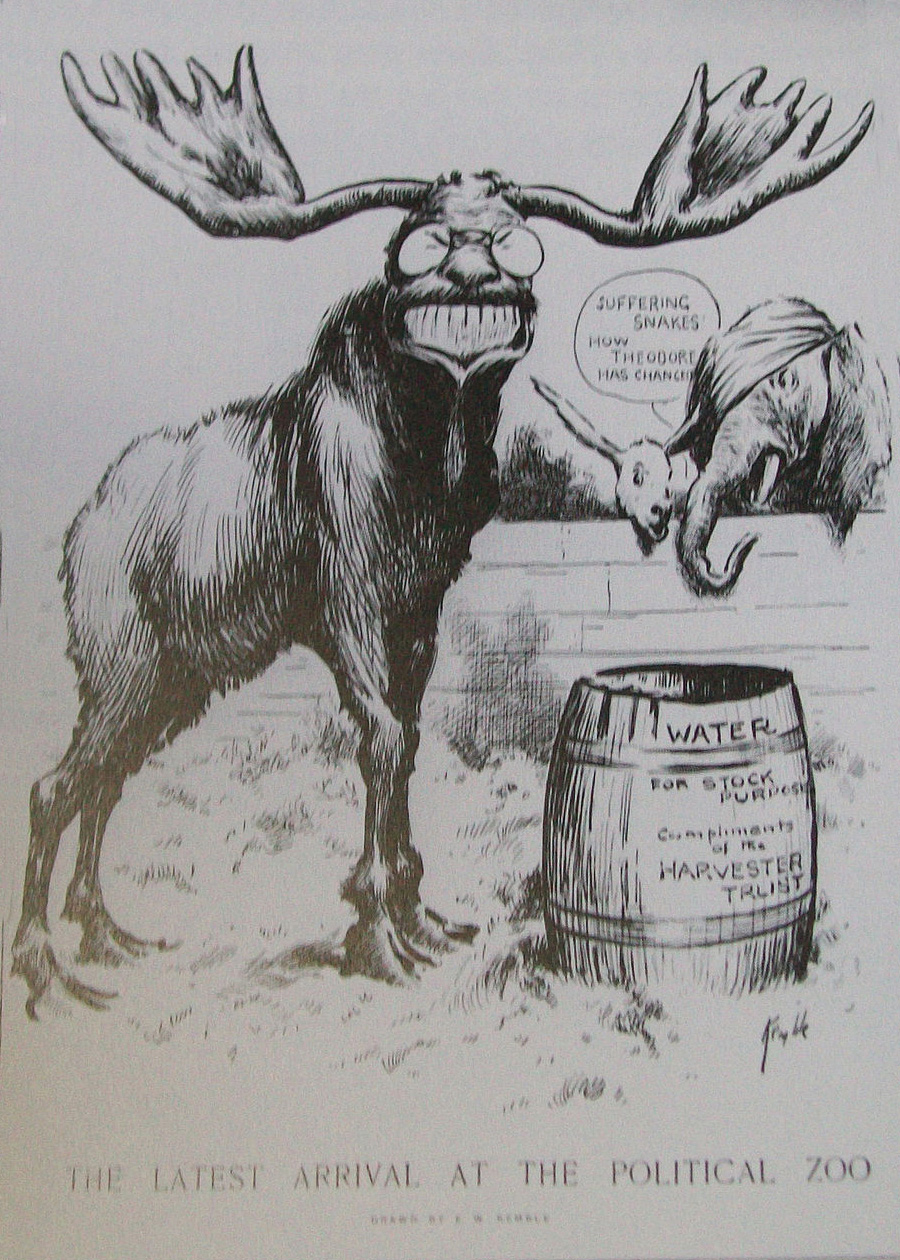

Progressive reformers ran for president under party labels. Former president Theodore Roosevelt split from the Republicans and ran as the Bull Moose Party candidate in 1912, and Robert LaFollette ran as the Progressive Party candidate in 1924. Republican William Howard Taft defeated Roosevelt, and LaFollette lost to Republican Calvin Coolidge.

Figure 10.4 Progressive Reformers Political Cartoon

The Progressive Reformers’ goal of more open and representative parties resonate today.

Source: Photo courtesy of E W Kemble, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Theodore_Roosevelt_Progressive_Party_Cartoon,_1912_copy.jpg .

New Deal and Cold War Eras

Democratic President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal program for leading the United States out of the Great Depression in the 1930s had dramatic effects on political parties. The New Deal placed the federal government in the pivotal role of ensuring the economic welfare of citizens. Both major political parties recognized the importance of being close to the power center of government and established national headquarters in Washington, DC.

An era of executive-centered government also began in the 1930s, as the power of the president was expanded. Roosevelt became the symbolic leader of the Democratic Party (Riechley, 1992). Locating parties’ control centers in the national capital eventually weakened them organizationally, as the basis of their support was at the local grassroots level. National party leaders began to lose touch with their local affiliates and constituents. Executive-centered government weakened parties’ ability to control the policy agenda (White & Shea, 2000).

The Cold War period that began in the late 1940s was marked by concerns over the United States’ relations with Communist countries, especially the Soviet Union. Following in the footsteps of the extremely popular president Franklin Roosevelt, presidential candidates began to advertise their independence from parties and emphasized their own issue agendas even as they ran for office under the Democratic and Republican labels. Presidents, such as Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush, won elections based on personal, rather than partisan, appeals (Caeser, 1979).

Candidate-Centered Politics

Political parties instituted a series of reforms beginning in the late 1960s amid concerns that party elites were not responsive to the public and operated secretively in so-called smoke-filled rooms. The Democrats were the first to act, forming the McGovern-Fraser Commission to revamp the presidential nominating system. The commission’s reforms, adopted in 1972, allowed more average voters to serve as delegates to the national party nominating convention , where the presidential candidate is chosen. The result was that many state Democratic parties switched from caucuses, where convention delegates are selected primarily by party leaders, to primary elections, which make it easier for the public to take part. The Republican Party soon followed with its own reforms that resulted in states adopting primaries (Crotty, 1984).

Figure 10.5 Jimmy Carter Campaigning in the 1980 Presidential Campaign

Democrat Jimmy Carter, a little-known Georgia governor and party outsider, was one of the first presidential candidates to run a successful campaign by appealing to voters directly through the media. After Carter’s victory, candidate-centered presidential campaigns became the norm.

Source: Used with permission from AP Photo/Wilson.

The unintended consequence of reform was to diminish the influence of political parties in the electoral process and to promote the candidate-centered politics that exists today. Candidates build personal campaign organizations rather than rely on party support. The media have contributed to the rise of candidate-centered politics. Candidates can appeal directly to the public through television rather than working their way through the party apparatus when running for election (Owen, 1991). Candidates use social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, to connect with voters. Campaign professionals and media consultants assume many of the responsibilities previously held by parties, such as developing election strategies and getting voters to the polls.

Key Takeaways

Political parties are enduring organizations that run candidates for office. American parties developed quickly in the early years of the republic despite concerns about factions expressed by the founders. A true, enduring party system developed in 1828. The two-party system of Democrats and Republicans was in place before the election of President Abraham Lincoln in 1860.

Party machines became powerful in the period following the Civil War when an influx of immigrants brought new constituents to the country. The Progressive Movement initiated reforms that fundamentally changed party operations. Party organizations were weakened during the period of executive-centered government that began during the New Deal.

Reforms of the party nominating system resulted in the rise of candidate-centered politics beginning in the 1970s. The media contributes to candidate-centered politics by allowing candidates to take their message to the public directly without the intervention of parties.

- What did James Madison mean by “the mischiefs of faction?” What is a faction? What are the dangers of factions in politics?

- What role do political parties play in the US political system? What are the advantages and disadvantages of the party system?

- How do contemporary political parties differ from parties during the era of machine politics? Why did they begin to change?

Aldrich, J. H., Why Parties? The Origin and Transformation of Party Politics in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995)

Caeser, J. W., Presidential Selection (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979).

Chambers, W. N., Political Parties in a New Nation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1963).

Chambers, W. N. and Walter Dean Burnham, The American Party Systems (New York, Oxford University Press, 1975).

Charles, J., The Origins of the American Party System (New York: Harper & Row, 1956).

Crotty, W., American Parties in Decline (Boston: Little, Brown, 1984).

Eldersveld, S. J. and Hanes Walton Jr., Political Parties in American Society , 2nd ed. (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000).

Epstein, L. D., Political Parties in the American Mold (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1986), 3.

Formisano, R. P., “Federalists and Republicans: Parties, Yes—System, No,” in The Evolution of the American Electoral Systems , ed. Paul Kleppner, Walter Dean Burnham, Ronald P. Formisano, Samuel P. Hays, Richard Jensen, and William G. Shade (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981), 37–76.

Hofstadter, R., The Idea of a Party System (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969), 200.

Holt, M. F., The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).

Kandall, J., “Boss,” Smithsonian Magazine , February 2002, accessed March 23, 2011, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/people-places/boss.html .

Key Jr., V. O., Politics, Parties, & Pressure Groups , 5th ed. (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1964).

Merriam, C. and Harold F. Gosnell, The American Party System (New York: MacMillan, 1922).

Owen, D., Media Messages in American Presidential Elections (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1991).

Pomper, G. M., Passions and Interests (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992).

Publius (James Madison), “The Federalist No. 10,” in The Federalist , ed. Robert Scigliano (New York: The Modern Library Classics, 2001), 53–61.

Rakove, M., Don’t Make No Waves, Don’t Back No Losers: An Insider’s Analysis of the Daley Machine (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975), 3.

Riechley, A. J., The Life of the Parties (New York: Free Press, 1992).

Riordon, W. L., Plunkitt of Tammany Hall (St. James, NY: Brandywine Press, 1994), 3.

Schudson, M., The Good Citizen (New York: Free Press, 1998).

White, J. K. and Daniel M. Shea, New Party Politics (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000).

American Government and Politics in the Information Age Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

US government and civics

Course: us government and civics > unit 6.

- Linkage institutions and political parties

Political parties: lesson overview

- Political parties

Key takeaways

Review questions, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Stanford University

Political Parties Are Essential Democratic Institutions

Essay within "The Realistic Promise of Multiparty Democracy in the United States," a political reform report from New America.

In April 2023, New America, the Center for Ballot Freedom, Protect Democracy, Lyceum Labs, and Stanford University’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law convened a conference at Stanford University on the future of political parties in the United States. The conference, titled “More Parties, Better Parties,” focused on the idea that U.S. democracy would benefit from stronger and more representative parties and that essential to that vision was opportunity for more parties beyond the current party duopoly to emerge. The essays in this collection, derived from papers prepared for the conference, trace the following argument: Parties are essential institutions in a democracy; there is an unjustified hostility to parties in much American political discourse; and fluid and overlapping coalitions of a multiparty system can improve governance and confidence. We then look at the promise of fusion voting, a practice once widespread and now prohibited in most states, which could allow new parties to gain a foothold by cross-endorsing candidates from established parties.

Political Parties (Origins, 1790s)

By Brian Hendricks

Philadelphia, long considered the “cradle of liberty” in America, was also the “cradle of political parties” that emerged in American politics during the 1790s, when the city was also the fledgling nation’s capital. A decade that began with the unanimously-chosen George Washington (1732-99) as the first President of the United States ended with partisan rancor, as the economic policies of Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804), tensions in America’s relationship with France, and the controversial Jay Treaty with England divided Americans into two distinct political parties which had little, if anything, in common. Philadelphia was the epicenter of this political earthquake.

However, partisan rancor in Philadelphia was not caused by the creation and presence of the federal government. Political factions and rivalries that had existed at the local level for many years were exacerbated by the fighting that emerged at the national level. Federalists who fostered an image of rule by the elites took the reins of government in a city and commonwealth where the disaffected “have-nots” had waged political war with the “haves” since the 1750s and 1760s, when Benjamin Franklin allied with many Quakers against the proprietorship of the Penn family–a family who (they believed) exploited the province for revenue.

On the national level, the signing of the U.S. Constitution in Philadelphia in 1787 and the subsequent ratification battles in the states created two distinct factions–“Federalists” who supported the document and “Anti-Federalists” who opposed it. The First Congress , which initially convened in New York in 1789 before moving to Philadelphia in 1790, consisted of men from both factions and reached agreement on a Bill of Rights and the establishment of Cabinet departments. But the proposals set forth by Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton created schisms that only widened during Washington’s administration. One such proposal involved the assumption of state war debts by the federal government. This plan angered those from states who had already paid off a large portion of their debts. Virginia Congressman James Madison (1751-1836), who had written many of the “ Federalist Papers ” along with Hamilton to promote the ratification of the Constitution, was one of those who sternly opposed Hamilton’s measures. Pennsylvania denounced the “funding scheme” as well, especially when speculators who became aware of the plan galloped across the countryside and bought up debt certificates from unsuspecting Pennsylvania veterans.

Early Divisions

When Hamilton later proposed the creation of a national bank, Madison was joined in his battle by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), who was alarmed at the growth and encroachment of the new central government and the bank’s questionable constitutionality. “A distinctive Anti-Federalist agenda emerged,” wrote Saul Cornell in The Other Founders . “The goal of Anti-Federalists was to limit the powers of the new government and bolster the states so that they would continue to be in a position to protect the liberty of their citizens.” By 1792, those opposed to Hamilton’s programs had coalesced into the Democratic-Republican Party (also styled as “Jeffersonians”). The elections in that year saw many gains by the nascent party and a majority in the U.S. House of Representatives.

The fissure between Jefferson’s party and Hamilton’s was caused by more than banks and debts. The Washington administration’s foreign policy made the gap even wider, as Hamilton’s Federalists favored closer ties with the British while the Jeffersonians favored France and the French Revolution . When war between the two European superpowers began in 1793, the Jeffersonians advocated honoring the alliance with France that was made during the American Revolution. Washington, hoping to avoid a war that the country could ill afford, sided with Hamilton and implemented a policy of neutrality, which many Jeffersonians interpreted as favoring Britain. Republicans had also criticized Washington and Vice President John Adams (1735-1826) of having monarchical tendencies, so the link to England was easily made.

During this time in 1793, Democratic Societies began to form across the country. One of the most prominent of these groups was the Pennsylvania Democratic Society, founded in Philadelphia by such prominent citizens as Alexander Dallas (1759-1817), who later served in James Madison’s cabinet. The societies extolled the virtues of the French Revolution and were inspired by Citizen Edmond Genêt , an ambassador from the new French republic to the United States.

Domestic issues also fostered growth among the societies. The Pennsylvania Democratic Society in Philadelphia vehemently opposed Hamilton’s excise tax on whiskey in 1794, which impacted many farmers in western Pennsylvania, and sought to elect officials who would repeal the excise law.

Whiskey Rebellion, French Revolution

Three events soon damaged the credibility of the societies. The French Revolution became more violent, culminating in the beheading of King Louis XVI. Citizen Genêt alienated President Washington by belligerently outfitting American privateers to engage in combat with British ships. And farmers in western Pennsylvania resorted to violence to oppose the excise tax (referred to as the “ Whiskey Rebellion ”). When Washington denounced the societies as disruptive and unrepublican, they experienced a rapid decline. Yet they served as a framework for the opposition party that emerged by the end of the decade.

An organized opposition party was not new to Pennsylvania. A quasi-party system had been developed in the aftermath of the ratification of its 1776 State Constitution . While the constitution fostered greater democracy by granting voting rights to all men regardless of property ownership, it was inadequate due to the lack of effective checks on the legislature, which soon overreached in its authority to confiscate property and overrule the judiciary. This last element was in direct contrast to the democratic spirit which prevailed in Pennsylvania when the document was drafted, and two parties – a “Constitutionalist” formation and a “Republican” faction which opposed the constitution – emerged. In 1790, Pennsylvanians adopted a new constitution that provided for greater parity among the branches, along with a bicameral legislature and a governor with veto power.

Nationally, the increasing partisanship of the 1790s was mirrored in the press, as Federalists and Republicans waged political war – which often included personal invective – in the pages of the country’s newspapers. In Philadelphia, the nation’s capital, Hamilton and Jefferson not only waged war but hired editors to create and manage partisan newspapers. John Fenno (1751-98) did the Federalists’ bidding in the Gazette of the United States , which originated in New York in 1789 and moved with the government to Philadelphia one year later. The Jeffersonians countered with the National Gazette of Philip Freneau (1752-1832) and the Aurora , which was edited by Benjamin Franklin’s grandson, Benjamin Franklin Bache (1769-98).

The Jay Treaty, signed between the United States and Britain in 1794 and ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1795, further widened the gap between the parties. While the treaty prevented war with Britain, Jeffersonians severely criticized it as a capitulation to England. The treaty did not address certain grievances, particularly the British practice of seizing American ships and the impressment of American seamen. But as a result of the treaty, along with the seeds planted by the Democratic Societies shortly beforehand, Jeffersonian Republicans observed major gains in Pennsylvania in 1796 due primarily to the aftermath of the Jay Treaty, and the Republican movement had, by this time, crystallized into a genuine opposition party.

Pennsylvania’s political evolution in the 1790s was a microcosm of the nation, as opposition to the Federalists steadily grew throughout the decade. The “have-nots” on the Western frontier and among Philadelphia’s urban poor were disillusioned with Hamiltonian policies that foreclosed their farms, taxed their whiskey, and favored the British monarchy over the French republic. By the middle of the decade, moderate Jeffersonians led by Thomas McKean (1734-1817), a signer of the Declaration of Independence and former Federalist, had taken control of the reins of Pennsylvania’s government.

Brian Hendricks is a Ph.D. candidate in early American history at Southern Illinois University. His research focuses on the election of 1796 and the growth of political parties in New York and Pennsylvania.

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

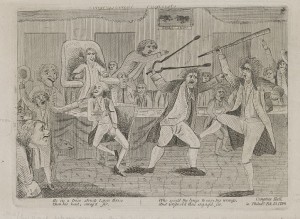

Congressional Pugilists

Library of Congress

In the first decade of political parties in the United States, a 1798 cartoon depicts fighting in Philadelphia's Congress Hall between Congressman Matthew Lyon, a Jeffersonian Republican, and Roger Griswold, a Federalist. An insulting reference to Lyon by Griswold triggered the spat. The text reads: "He in a trice struck Lyon thrice / Upon his head, enrag'd sir, / Who seiz'd the tongs to ease his wrongs, / And Griswold thus engag'd, sir."

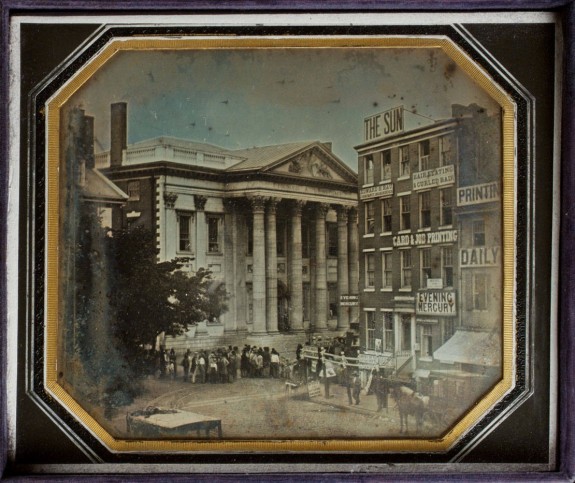

Federalist Landscape

Library Company of Philadelphia

Among the many ramifications of Alexander Hamilton’s economic policies were his plans for a national bank and the subsequent creation of the First Bank of the United States in Philadelphia, shown here in 1844, when the building was home to the Girard Bank. This institution was followed by a Second Bank of the United States during the presidency of James Madison, and the Second Bank–the focal point of bitter partisan warfare between Andrew Jackson and his opponents – existed until 1836.

Related Topics

- Philadelphia and the Nation

- Cradle of Liberty

Time Periods

- Capital of the United States Era

- Center City Philadelphia

- Mayors (Philadelphia)

- Red City (The)

- Alien and Sedition Acts

- Democratic-Republican Societies

- Capital of the United States (Selection of Philadelphia)

- Political Conventions

- U.S. Congress (1790-1800)

- Philadelphia and Its People in Maps: The 1790s

- U.S. Presidency (1790-1800)

- Socialist Party

Related Reading

Burns, Eric. Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism . New York: Perseus Books, 2006.

Charles, Joseph. “Hamilton and Washington: The Origins of the American Party System.” The William and Mary Quarterly , Third Series, Vol. 12, No. 2 (April, 1955): 217-267.

Charles, Joseph. “The Jay Treaty: The Origins of the American Party System,” The William and Mary Quarterly , Third Series, Vol. 12, No. 4 (Oct., 1955): 581-630.

Cornell, Saul. The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788-1828 . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Tinkcom, Harry. The Republicans and Federalists in Pennsylvania, 1790-1801: A Study in National Stimulus and Local Response . Harrisburg, Pa.: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1950.

Related Places

Congress Hall , Sixth and Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia.

Franklin Court Printing Office , Market Street between Third and Fourth Streets, Philadelphia.

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- More Pennsylvania voters shun major parties (WHYY, October 30, 2014)

- The First American Party System: Events, Issues, and Positions (NEH)

- History of the U.S. House of Representatives

- The Federalist Papers

- Podcast: Political Parties and the Constitution (National Constitution Center)

Connecting the Past with the Present, Building Community, Creating a Legacy

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Republican Party — Political Parties in the US: History of the Democratic Party

Political Parties in The Us: History of The Democratic Party

- Categories: Republican Party

About this sample

Words: 1509 |

Published: Mar 14, 2019

Words: 1509 | Pages: 3 | 8 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, party politics in the u.s, the history of democratic party.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Government & Politics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 640 words

2 pages / 971 words

2 pages / 913 words

4 pages / 1608 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Republican Party

I’d be lying if I said my parents didn’t influence my political ideology. I believe any young man or woman our age would be lying if they said that their parents didn’t have any sort of influence on their political ideologies. [...]

To properly compare the Democratic and Republican party platforms, I am going to pick three political issues that have popped up in this year’s election and review the party’s opinions and plans and highlight their similarities [...]

Despite all the efforts and focus towards food safety, there is still a high prevalence of foodborne diseases in the restaurant industry. This high prevalence is mainly attributed to poor food handling and poor personal hygiene [...]

Lincoln Steffens was a political journalist. He became famous when he began to write a series on the corruption of American Cities, called The Shame of Cities. Steffens focused mainly on political corruption of the municipal [...]

The British Government in its response to the green paper in regards to the corporate governance reforms touched on areas that will be reformed starting June 2018. They will use a mixture of both the secondary legislation and [...]

Social Advertising is the first form of advertising that systematically leverages historically offline dynamics, such as peer-pressure, friend recommendations, and other forms of social influence. Social media has the power to [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Essay on Political Parties in the United States

The divided political factions within the United States pose several dangers within our outside certain groups and ordinary citizens. It can lead to group mentality against others who are not within the same factions such as Republicans and Democrats, using voter alienation in terms of location and work, and using times of crisis to uplift a faction similar to political groups in the past and currently.

Even though there are several political parties in the United States, Republicans and Democrats are the main polarizers. And these parties can often utilize a group-thinking mentality where members are surrounded by others who have similar beliefs to them often agreeing on the same things. There can be conflict within the group that can cause ostracization leading to being an out-group or even have conflict outside the group who are also the out-groups. Often, members and supporters can speak outwardly against the other party, leading to more tension such as at rallies or online with social media condemning the others parties’ opinions.

For example, in the in and out-group video, someone would feel empathy for an in-group member being harmed and would not harm someone else in the group and the opposite from members outside their group. An example would be during the first peek of the pandemic where Republicans were worried about the country’s economy but also their local economies during the business shutdowns and if you agreed, you were met with supportive rhetoric, and those who were not, were especially in some online spaces were met with insults.

Depending on the state, there are different concentrations of party members. Democratic members are often concentrated in the northeast and northwest while Republican Members are more concentrated in the Midwest and south. More specifically, there are more democrats in urban cities and more republicans in rural areas with suburbs being the mix of the two. The party is then able to alienate voters with speeches, commercials, and campaigns to their lives. This can be seen with campaigns run against the outside party called smear campaigns on social media and television.

This isolation creates more tension within the country which is dangerous due to the large divide impacting ordinary citizens. For example, bills may not be passed because of disagreeing and animosity exists in different spaces. This can be seen with the stimulus to spread to citizens but when it came down to voting, it was split between the leaders of the two parties. People within these groups are divided by a different means and it leads to conflict over issues such as funding and programs to different groups where one might get the short end of the stick in one stance. This can also be seen with how cities and rural areas are viewed in stereotypical lenses where the rural area might be viewed as uneducated and among other things and where a city is seen as better and more educated. This exists vice versa where leadership in urban areas typically on the west coast such as California or other major cities such as New York and Chicago which are democratic run are showing that the leadership is not doing a good job there and being a reason why there should be more support to Republicans.

Recently with the Keystone Pipeline, Republicans who were main supporters drew in more support with the promise for more jobs to ordinary citizens and economic gain which aligns with the party values. When it was shut down, there were critiques to the opposing party but also the administration. In the Don’t Be a Sucker, the Hungarian professor spoke of the speech a member of the Nazi party being the start of events. The member was speaking of wages and religion to isolate those who were only Christian but also those who may have worked in factories or are unemployed. This can often be used with patriotism and being an American who does certain work to support the country or those who want to support their country by working hard. This can be explained for Democratic speeches and rallies as well where leaders will target the urban population with city reform and targeting their life. Groupthink is dangerous especially in political settings where it will impact everyone leader, member, or opposing member where difference is not exactly welcomed with more tension created.

Times of crisis within the United States allow different parties to gain more support or get their party values out there. In the 1930s, the Nazi Party gained more support after unemployment hit due to the economic depression but also the frustration from the aftermath of World War I, allowed for the party to fulfill insecurities that the people had with the current government. This can be seen with recent events of the pandemic, unemployment crises, economic downline. Citizens who are members and supporters of different parties often become scared but also frustrated in the event of a crisis or even after a crisis. It can go back to in and out-groups to when someone speaks out, those who support it do not conflict with another and can insult the out-group or opposing group.

With the ongoing pandemic, republicans and democrats were able to gain supporters or gain traction with their existing supporters by discussing employment and economic gain for the local and national economy. The danger this invokes is a way of uses fear and frustration to overall gain and support for the party. In times where citizens are feeling the crisis and aftermath, they look to their leaders but fears and frustrations are utilized against but also for them. For example, someone might be nervous about the pandemic, the business shutdowns, and new regulations which may be impacting their job and livelihood, and this nervousness is used to push something by a party.

The polarization in modern United States politics leads to further tension and conflict which is ultimately dangerous to ordinary citizens but also the cooperation between leaders who are part of different parties. It is dangerous in that it can cause isolation, group-thinking, and utilization of fear and frustration during times of crisis.

Related Samples

- The Bill of Rights. Why is the First Amendment Important Essay Example

- The Bill of Rights and Gun Control Essay Example

- Essay on Ancient Greeks Inventions: The Impact on Modern Day Society

- Essay on Algonquin Tribe

- Why the United States Need More Regulations on Gun Control Essay Example

- Research Paper: Differences Between Political Systems

- Shirly Chisholm Biography Essay Example

- Theodore Roosevelt and the End of Progressivism Essay Example

- The Bill Of Rights Essays Example

- What it Means to Live in Cuba Essay Example

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

- How It Works

- All Projects

- Write my essay

- Buy essay online

- Custom coursework

- Creative writing

- Custom admission essay

- College essay writers

- IB extended essays

- Buy speech online

- Pay for essays

- College papers

- Do my homework

- Write my paper

- Custom dissertation

- Buy research paper

- Buy dissertation

- Write my dissertation

- Essay for cheap

- Essays for sale

- Non-plagiarized essays

- Buy coursework

- Term paper help

- Buy assignment

- Custom thesis

- Custom research paper

- College paper

- Coursework writing

- Edit my essay

- Nurse essays

- Business essays

- Custom term paper

- Buy college essays

- Buy book report

- Cheap custom essay

- Argumentative essay

- Assignment writing

- Custom book report

- Custom case study

- Doctorate essay

- Finance essay

- Scholarship essays

- Essay topics

- Research paper topics

- Top queries link

Best Politics Essay Examples

Political parties in the us.

741 words | 3 page(s)

In his seminal work on political parties, Monroe (2001) provides the following definition of a political party: “a political party is an institution through which elites coordinate their activities and elections and government as they attempt to satisfy the interests of their support base” (p. 17). Monroe also cites two authoritative theoreticians of the political parties Downs (1957) and Schlesinger (1985), to extend this definition. Both agree that the political elites should be perceived as acting out of self-interest be it power, income, prestige, or simply the love of conflict (Downs, 1957 in Monroe, 2001, p.17). Only from this definition can we draw a conclusion that, for the general public, the effects of political parties cannot be beneficial, since the very notion of the party suggests operating in the interest of the elites. More evidence will leave no doubt in the detrimental character of political parties’ effects.

THESIS STATEMENT: The effects of the political parties in the United States are detrimental for the society, because the parties represent the interests of those who fund them rather than masses and because parties cripple the political process by inability to reach consensus over crucial matters (i.e. cause polarization).

Use your promo and get a custom paper on "Political Parties In The US".

Political parties affect the society and the political process in a negative way these days. Specifically, they represent the interests of those who fund them, or, better, buy them instead of catering for the needs of their voters. Recent surveys show that modern parties are in decline due to lack of public trust and public loyalty. If fifty years ago the statistical data showed that one I eleven individuals on average affiliated himself/herself with a certain party, today the ration is clearly down to one in eighty-eight people (The Stationery Office, 2007). Interestingly, the decline in party loyalty and party identification has taken place in the content of young people’s having generally higher levels of genuine political interest and involvement. One the biggest reasons is that people feel that parties are funded by big corporations and manipulated by their owners. This causes them to lose trust in parties’ fairness and usefulness (The Stationery Office, 2007). A good example which shows how parties are manipulated by their sponsors is the tendency of those people who identify as Republicans to reject the idea that global warming poses a threat (Hamilton, 2009, p.407).

Next, parties have detrimental effects, since they cripple the political process by inability to reach consensus over crucial matters. In this case, with reference to the U.S. society, polarization takes place and political decisions are difficult to achieve. According to McCarty, the detrimental effects of polarization are as follows: it poses obstacles to building of legislative coalitions and leads to policy “gridlock”; it has a definite conservative effect on social policy and on the country’s economy; and it has a negative impact on the functioning of the judiciary and administrative state; it has changed the balance of power among state institutions at the expense of the U.S. Congress (McCarty, n.d.).

The supporters of the party system argue that parties are essential of democracy, as for example, James Burns (2001), the author of the textbook Government by the People. They say that political parties are essential by “simplifying voting choices, organizing the competition, unifying the electorate, bridging the separation of powers and fostering cooperation among branches of government, translating public preferences into policy, and providing loyal opposition” (p. 146). However, this claim may easily be dismissed as inherently flawed. If political parties in the United States fail to represent the interests of common people, i.e. do not perform their first and foremost function, they destroy the democracy. Therefore, all other aspects are unimportant, since democracy is about the rule of the mob.

In summary, these days the effects of the political parties on the U.S. society are clearly detrimental. Not only do the parties fail to represent the interests of the ordinary people or cripple the political process through polarization, but they also undermine the foundations of democracy.

- Burns, J. (2001). Government by the people. Prentice Hall.

- Diamond, L. & Gunther, R. (2001). Political parties and democracy. JHU Press.

- Hamilton, L. (2009). Statistics with STATA: Updated for Version 10. Cengage Learning.

- Monroe, J. (2001). The political party matrix: The persistence of organization. SYNY Press.

- McCarty, N. (2007). The policy consequences of political polarization. In Paul Pierson and Theda Skocpol eds. The transformation of the American polity. Princeton University Press.

- The Stationery Office (2007). Strengthening democracy: fair and sustainable funding of political parties. The Stationery Office.

Have a team of vetted experts take you to the top, with professionally written papers in every area of study.

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Changing partisan coalitions in a politically divided nation, party identification among registered voters, 1994-2023.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to explore partisan identification among U.S. registered voters across major demographic groups and how voters’ partisan affiliation has shifted over time. It also explores the changing composition of voters overall and the partisan coalitions.

For this analysis, we used annual totals of data from Pew Research Center telephone surveys (1994-2018) and online surveys (2019-2023) among registered voters. All telephone survey data was adjusted to account for differences in how people respond to surveys on the telephone compared with online surveys (refer to Appendix A for details).

All online survey data is from the Center’s nationally representative American Trends Panel . The surveys were conducted in both English and Spanish. Each survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, age, education, race and ethnicity and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology , as well as how Pew Research Center measures many of the demographic categories used in this report .

The contours of the 2024 political landscape are the result of long-standing patterns of partisanship, combined with the profound demographic changes that have reshaped the United States over the past three decades.

Many of the factors long associated with voters’ partisanship remain firmly in place. For decades, gender, race and ethnicity, and religious affiliation have been important dividing lines in politics. This continues to be the case today.

Yet there also have been profound changes – in some cases as a result of demographic change, in others because of dramatic shifts in the partisan allegiances of key groups.

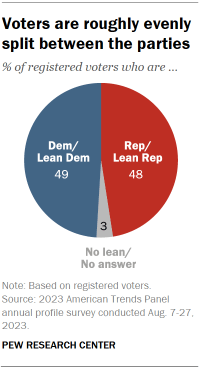

The combined effects of change and continuity have left the country’s two major parties at virtual parity: About half of registered voters (49%) identify as Democrats or lean toward the Democratic Party, while 48% identify as Republicans or lean Republican.

In recent decades, neither party has had a sizable advantage, but the Democratic Party has lost the edge it maintained from 2017 to 2021. (Explore this further in Chapter 1 . )

Pew Research Center’s comprehensive analysis of party identification among registered voters – based on hundreds of thousands of interviews conducted over the past three decades – tracks the changes in the country and the parties since 1994. Among the major findings:

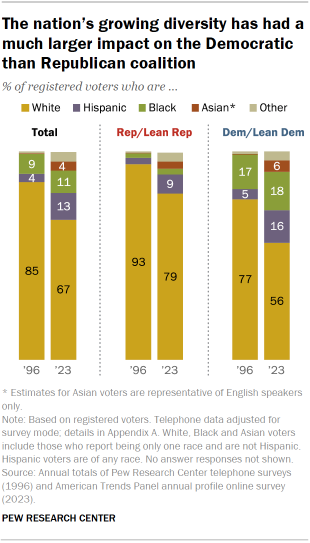

The partisan coalitions are increasingly different. Both parties are more racially and ethnically diverse than in the past. However, this has had a far greater impact on the composition of the Democratic Party than the Republican Party.

The share of voters who are Hispanic has roughly tripled since the mid-1990s; the share who are Asian has increased sixfold over the same period. Today, 44% of Democratic and Democratic-leaning voters are Hispanic, Black, Asian, another race or multiracial, compared with 20% of Republicans and Republican leaners. However, the Democratic Party’s advantages among Black and Hispanic voters, in particular, have narrowed somewhat in recent years. (Explore this further in Chapter 8 .)

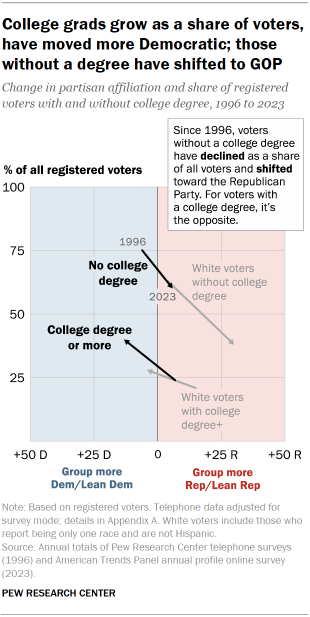

Education and partisanship: The share of voters with a four-year bachelor’s degree keeps increasing, reaching 40% in 2023. And the gap in partisanship between voters with and without a college degree continues to grow, especially among White voters. More than six-in-ten White voters who do not have a four-year degree (63%) associate with the Republican Party, which is up substantially over the past 15 years. White college graduates are closely divided; this was not the case in the 1990s and early 2000s, when they mostly aligned with the GOP. (Explore this further in Chapter 2 .)

Beyond the gender gap: By a modest margin, women voters continue to align with the Democratic Party (by 51% to 44%), while nearly the reverse is true among men (52% align with the Republican Party, 46% with the Democratic Party). The gender gap is about as wide among married men and women. The gap is wider among men and women who have never married; while both groups are majority Democratic, 37% of never-married men identify as Republicans or lean toward the GOP, compared with 24% of never-married women. (Explore this further in Chapter 3 .)

A divide between old and young: Today, each younger age cohort is somewhat more Democratic-oriented than the one before it. The youngest voters (those ages 18 to 24) align with the Democrats by nearly two-to-one (66% to 34% Republican or lean GOP); majorities of older voters (those in their mid-60s and older) identify as Republicans or lean Republican. While there have been wide age divides in American politics over the last two decades, this wasn’t always the case; in the 1990s there were only very modest age differences in partisanship. (Explore this further in Chapter 4 .)

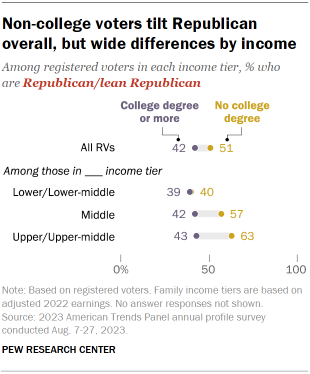

Education and family income: Voters without a college degree differ substantially by income in their party affiliation. Those with middle, upper-middle and upper family incomes tend to align with the GOP. A majority with lower and lower-middle incomes identify as Democrats or lean Democratic. There are no meaningful differences in partisanship among voters with at least a four-year bachelor’s degree; across income categories, majorities of college graduate voters align with the Democratic Party. (Explore this further in Chapter 6 .)

Rural voters move toward the GOP, while the suburbs remain divided: In 2008, when Barack Obama sought his first term as president, voters in rural counties were evenly split in their partisan loyalties. Today, Republicans hold a 25 percentage point advantage among rural residents (60% to 35%). There has been less change among voters in urban counties, who are mostly Democratic by a nearly identical margin (60% to 37%). The suburbs – perennially a political battleground – remain about evenly divided. (Explore this further in Chapter 7 . )

Growing differences among religious groups: Mirroring movement in the population overall, the share of voters who are religiously unaffiliated has grown dramatically over the past 15 years. These voters, who have long aligned with the Democratic Party, have become even more Democratic over time: Today 70% identify as Democrats or lean Democratic. In contrast, Republicans have made gains among several groups of religiously affiliated voters, particularly White Catholics and White evangelical Protestants. White evangelical Protestants now align with the Republican Party by about a 70-point margin (85% to 14%). (Explore this further in Chapter 5 .)

What this report tells us – and what it doesn’t

In most cases, the partisan allegiances of voters do not change a great deal from year to year. Yet as this study shows, the long-term shifts in party identification are substantial and say a great deal about how the country – and its political parties – have changed since the 1990s.

The steadily growing alignment between demographics and partisanship reveals an important aspect of steadily growing partisan polarization. Republicans and Democrats do not just hold different beliefs and opinions about major issues , they are much more different racially, ethnically, geographically and in educational attainment than they used to be.

Yet over this period, there have been only modest shifts in overall partisan identification. Voters remain evenly divided, even as the two parties have grown further apart. The continuing close division in partisan identification among voters is consistent with the relatively narrow margins in the popular votes in most national elections over the past three decades.

Partisan identification provides a broad portrait of voters’ affinities and loyalties. But while it is indicative of voters’ preferences, it does not perfectly predict how people intend to vote in elections, or whether they will vote. In the coming months, Pew Research Center will release reports analyzing voters’ preferences in the presidential election, their engagement with the election and the factors behind candidate support.

Next year, we will release a detailed study of the 2024 election, based on validated voters from the Center’s American Trends Panel. It will examine the demographic composition and vote choices of the 2024 electorate and will provide comparisons to the 2020 and 2016 validated voter studies.

The partisan identification study is based on annual totals from surveys conducted on the Center’s American Trends Panel from 2019 to 2023 and telephone surveys conducted from 1994 to 2018. The survey data was adjusted to account for differences in how the surveys were conducted. For more information, refer to Appendix A .

Previous Pew Research Center analyses of voters’ party identification relied on telephone survey data. This report, for the first time, combines data collected in telephone surveys with data from online surveys conducted on the Center’s nationally representative American Trends Panel.

Directly comparing answers from online and telephone surveys is complex because there are differences in how questions are asked of respondents and in how respondents answer those questions. Together these differences are known as “mode effects.”

As a result of mode effects, it was necessary to adjust telephone trends for leaned party identification in order to allow for direct comparisons over time.

In this report, telephone survey data from 1994 to 2018 is adjusted to align it with online survey responses. In 2014, Pew Research Center randomly assigned respondents to answer a survey by telephone or online. The party identification data from this survey was used to calculate an adjustment for differences between survey mode, which is applied to all telephone survey data in this report.

Please refer to Appendix A for more details.

Facts are more important than ever

In times of uncertainty, good decisions demand good data. Please support our research with a financial contribution.

Report Materials

Table of contents, behind biden’s 2020 victory, a voter data resource: detailed demographic tables about verified voters in 2016, 2018, what the 2020 electorate looks like by party, race and ethnicity, age, education and religion, interactive map: the changing racial and ethnic makeup of the u.s. electorate, in changing u.s. electorate, race and education remain stark dividing lines, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Advertisement

Supported by

More Voters Shift to Republican Party, Closing Gap With Democrats

The trend toward the Republican Party among white voters without a college degree has continued, and Democrats have lost ground among Hispanic voters, too.

- Share full article

By Ruth Igielnik

In the run-up to the 2020 election, more voters across the country identified as Democrats than Republicans. But four years into Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s presidency, that gap has shrunk, and the United States now sits almost evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans.

Republicans have made significant gains among voters without a college degree, rural voters and white evangelical voters, according to a new report from the Pew Research Center . At the same time, Democrats have held onto key constituencies, such as Black voters and younger voters, and have gained ground with college-educated voters.

The report offers a window into how partisan identification — that is, the party that voters tell pollsters they identify with or lean toward — has shifted over the past three decades. The report groups independents, who tend to behave like partisans even if they eschew the label, with the party they lean toward.

Voters are evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans.

Among all registered voters

“The Democratic and Republican parties have always been very different demographically, but now they are more different than ever,” said Carroll Doherty, the director of political research at Pew.

The implications of the trend, which has also shown up in party registration data among newly registered voters , remains uncertain, as a voter’s party affiliation does not always predict who he or she will select in an election. But partisan affiliation patterns do offer clues to help understand how the shifting coalitions over the last quarter century have shaped recent political outcomes. During the Trump administration, the Democratic Party’s coalition grew, helping to bring about huge victories in the 2018 midterm elections and a victory for President Biden in 2020.

The G.O.P. has long struggled with the fact that there have generally been fewer Americans who identified as Republicans than as Democrats. After Barack Obama was re-elected as president in 2012, the Republican Party produced an autopsy report that concluded that in order to be successful in future elections, the party would need to widen its tent to include Black and Hispanic voters, who were not traditionally aligned with the G.O.P.

Twelve years later, the party has made some small gains with Hispanic voters. But it is growth with the white working class and with rural voters that has propelled Republicans to equity with Democrats.

The catch is that white working-class voters are slowly declining as a share of registered voters, so the Republican strategy of relying heavily on the group may not be sustainable in the long term.

At the same time, a much talked-about broad political realignment among Black and Hispanic voters has yet to materialize, at least by the metric of party identification.

The education gap among white voters has grown dramatically since 2010.

Percent who identify as Republican or lean toward the Republican party

Republicans’ growing strength with white working-class voters represents one of the biggest political schisms in the country over the past 15 years. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Democrats had a slight partisan identification advantage among voters without a college degree, while college-educated voters were more evenly divided between the two parties. Beginning in the early 2010s — and accelerating during the presidency of Donald J. Trump — voters without a college degree, in particular white voters without a degree, increasingly moved toward the Republican Party.

Now, nearly two-thirds of all white noncollege voters identify as Republicans or lean toward the Republican Party.

And Republicans are making gains among white women, as well. In 2018, a year after the Women’s March that attracted millions to protest Mr. Trump’s policies, the group was split about evenly between Democrats and Republicans. But since then, Republicans have slowly been gaining ground. They now hold a 10 percentage point partisanship advantage.

Overall, over most of the last 30 years, white voters have been more likely to identify as Republicans than Democrats, though the gap closed briefly in the mid-2000s.

While Hispanic voters are still far more likely to identify as Democrats, the party’s edge with the group has narrowed in the past few years. Currently, 61 percent of Hispanic voters identify as Democrats or lean toward the Democratic Party, down from nearly 70 percent in 2016. That trend mirrors polling in 2020 and 2024 that has shown the potential for support for Mr. Trump to grow among Hispanic voters.

That change appears most notable among Hispanic voters who do not have a college degree or who identify as Protestant. As recently as 2017, the latter group leaned Democratic; now, it is more likely to identify as Republican, even as Hispanic Catholics are still more likely to identify as Democrats.

These shifts in partisanship fall short of what some predicted to be a political realignment, said Bernard Fraga, an associate professor of political science at Emory University who studies Latino voters.

But Latino voters care deeply about the economy, Mr. Fraga noted, and Latinos who are ideologically conservative are interested in Republicans and their plans for the country.

“It is also important to remember that the Latino population is extremely dynamic,” Mr. Fraga said. “There are a tremendous number of newly eligible voters in every election cycle. And what we perceive as a change or shift for Latinos is going to be disproportionately due to new voters.”

“About one third of Latino voters weren’t even in the electorate before 2016,” he added.

More Hispanic voters now identify as Republicans than in 2016.

Percent who identify as Republican or lean toward the Republican Party