Inflation and Growth

Models of inflation and growth in the sixties emphasized the portfolio substitution mechanism by which higher inflation made capital more attractive to hold relative to money, leading to higher capital intensity, and in the transition period to higher growth.The empirical evidence, however, is that growth and inflation are negatively correlated. Reasons for this negative correlation are investigated, and then embodied in a simple monetary maximizing model. Higher inflation is associated with lower growth because lower real balances reduce the efficiency of factors of production, and because there may be a link between government purchases and the use of the inflation tax. Comparative steady states and comparative dynamics is analyzed and the generally negative association between inflation and growth, both in steady states and in transition processes, is demonstrated.

- Acknowledgements and Disclosures

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Money Growth, Money Velocity and Inflation in the US, 1948–2021

- RESEARCH ARTICLE

- Published: 11 November 2023

Cite this article

- Juan E. Castañeda ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4852-9646 1 &

- José Luis Cendejas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8417-9455 2

160 Accesses

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

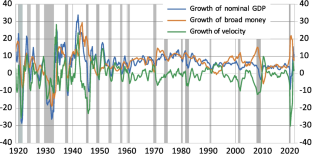

Leading central banks did not anticipate the surge in inflation in 2021 and 2022. In our paper we assess whether changes in the velocity of money and monetary growth (broadly defined) explain long term inflation patterns in the US. We use a hundred-year sample to study the long term and the cyclical behaviour of money velocity. We find that changes in the velocity of money are short lived and revert to its mean. We also characterise the periods where changes in money velocity have kept closer to its mean as those of monetary equilibrium. We use a regime switching model to test for the impact of changes in the amount of money (broadly defined) and in money velocity in inflation over the medium and long term. Our model explains both the non-inflationary outcome of the Global Financial Crisis and the surge in inflation in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

An Analysis of the Time-Varying Behavior of the Equilibrium Velocity of Money in the Euro Area

Money-based underlying inflation measure for russia: a structural dynamic factor model approach.

Elena Deryugina & Alexey Ponomarenko

Money and inflation in Switzerland

Peter Kugler & Samuel Reynard

Data Availability

Data used and sources detailed in footnote 2.

The relationship between money growth, inflation and money velocity has been modelled for the period 1948–2021 due to the availability of comparable data series since 1948. In Sect. 3 we cover a broader time period, from 1919 to 2021, as it is available for money growth and nominal GDP (on the contrary, for CPI inflation we have data since 1948).

By broad money, we mean a monetary aggregate that includes not just cash in circulation but the majority of bank deposits in the US. In this regard, we have made use of the monetary aggregate M3 calculated by Shadow Government Statistics ( http://www.shadowstats.com ), for 2006-2021, following the same method and data which the US Federal Reserve used to publish M3 (1959-2006), and broad money from Gordon ( 1986 ) for 1919-1958. For nominal GDP: Gross Domestic Product, Billions of Dollars, Quarterly ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org ) after 1959 and Gordon ( 1986 ) for 1919-1958.

https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions

We include an intercept in the test coherently with the non-zero value of the mean growth of the velocity, \(\mu_{v}\) , and select automatically the number of lags of the test by means of a Schwarz information criterion.

Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average, seasonally adjusted ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org ).

We refer to the spectral gain of the filter \(1 - L^{4}\) , which is applied when calculating the annual rate of a time series. The spectral gain measures the increase in amplitude of any specific frequency component of a time series. For the filter \(1 - L^{4}\) , the spectral gain in the frequency domain is \(2(1 - \cos 4\omega )\) with \(\omega\) a frequency component. This filter eliminates the trend and seasonal variation components, letting the remaining components pass. Within them, above the year, the fluctuations with a period between 5.3 quarters and 16 quarters have a greater weight (i. e. a normalized gain greater than 0.5).

Anderson RG, Bordo M, Duca JV (2017) Money and Velocity during Financial Crises: From the Great Depression to the Great Recession. J Econ Dyn Control 81(August):32–49

Benati L (2009) Long run evidence of money growth and inflation. Working Paper series, No. 1027. European Central Bank

Benati L (2020) Money velocity and the natural rate of interest. J Monet Econ 116:117–134

Article Google Scholar

Benati L, Lucas R, Nicolini JP, Weber W (2019) International Evidence on Long-Run Money Demand. Staff report 587. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

Borio C, Hofmann B, Zakrajšek E (2023) Does money growth help explain the recent inflation surge? BIS bulletin 67. January 2023. Accessed online

Castañeda J, Congdon T (2020) Inflation, the next threat? Covid Briefing Paper 7. June. Institute of Economic Affairs

Clarida R (2020) U.S. Economic Outlook and Monetary Policy. Speech at the New York Association for Business Economics. New York (via webcast). May 21 st 2020

Congdon T (2021) Can monetary policy run out of ammunition? The role of the money-equities-interaction channel in monetary policy. In Economic Affairs. Vol. 41, 1. February 21–37

De Grauwe P, Polan M (2005) Is Inflation Always and Everywhere a Monetary Phenomenon? Scandinavian Journal of Economics 107(2):239–259

De Santis R (2012) Quantity theory is alive. The role of international portfolio shifts. Working Paper series, 1435. European Central Bank

Dery C, Serletis A (2023) Macroeconomic Fluctuations in the United States: The Role of Monetary and Fiscal Policy Shocks. Open Economies Review. February

European Central Bank (2022) Overview of monetary policy strategy. European Central Bank, 2022. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/home/search/review/html/ecb.strategyreview_monpol_strategy_overview.en.html

Federal Reserve Board of Governors 2020 (2020) Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy. Press release. August 27 th 2020

Friedman M (1956) Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Google Scholar

Gao H, Kulish M, Nicolini JP (2020) Two illustrations of the quantity theory of money reloaded. Working Paper 774. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

Gordon RJ (ed) (1986) The American Business Cycle. University of Chicago Press, for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Chicago, pp 803–806

Greenwood J, Hanke S (2022) On monetary growth and inflation in leading economies, 2021–22: Relative prices and the overall price level. In Economic Affairs July 42(2):288–306

Haas J, Neely C, Emmons W (2020) Responses of International Central Banks to the Covid-19 Crisis. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Review, 102(4):October

Hall S, Swamy P, Tavlas G (2012) Milton Friedman, the demand for money and the ECB monetary policy strategy. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review. May-June, 153–185

Hamilton JD (1989) A New Approach to the Economic Analysis of Nonstationary Time Series and the Business Cycle. Econometrica 57(2):357–384

Hanke S, Ma Z, Cheng R (2022) On the Quantity Theory of Money: some monetary facts. Studies in Applied Economics, Num. 224, December. Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise

Kim CJ, Nelson CR (1999) State-Space Models with Regime Switching. The MIT Press, Cambridge

King M (2021) Monetary Policy in a World of Radical Uncertainty. IIMR Public Lecture, November 2021. Accessed online

Lucas R (1980) Two illustrations of the quantity theory of money. Am Econ Rev 70(5):1005–1014

Lucas R (1996) Nobel lecture: monetary neutrality. J Polit Econ 104(4):661–682

Milas C (2009) Does high M4 money growth trigger large increases in UK inflation? Evidence from a regime-switching model. Oxford Econ Pap 6(1):168–182

Nelson E (2008) Why money growth determines inflation in the long run: answering the Woodford critique. Working Paper 13. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Papadia F, Cadamuro L (2021) Does money growth tell us anything about inflation?. Working Paper 11. Bruegel

Powell J (2021a) Semi-annual Monetary Policy Report to US Congress. February 23rd. Accessed online

Powell J (2021b) House Financial Services Committee. December 1st. Accessed online

Reynard S (2023) Central bank balance sheet, money and inflation. Econ Lett 224. March. Accessed online

Schnabel I (2020) The ECB’s monetary policy during the coronavirus crisis – necessary, suitable and proportionate. Berlin Economic Roundtable. 2nd July 2020. Accessed online

Teles P, Uhlig H (2013). Is quantity theory still alive? Working Paper 1605. European Central Bank

Download references

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Guillermo Sagnier for his excellent research assistance. Financial support of Universidad Francisco de Vitoria to this research is also acknowledged. We thank the referees for their comments, as well those from the attendees and fellow contributors to the ‘2022 Institute of International Monetary Research Conference’—where an earlier version of the paper was presented.

Universidad Francisco de Vitoria.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Vinson Centre, University of Buckingham, Hunter Street Campus, Buckingham, MK18 1EG, UK

Juan E. Castañeda

Universidad Francisco de Vitoria. Pozuelo de Alarcón, 28223, Madrid, Spain

José Luis Cendejas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Juan E. Castañeda .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Castañeda, J.E., Cendejas, J.L. Money Growth, Money Velocity and Inflation in the US, 1948–2021. Open Econ Rev (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-023-09739-0

Download citation

Accepted : 25 September 2023

Published : 11 November 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-023-09739-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Money velocity

- Monetary equilibrium

- Money and inflation

- Quantity theory of money

- Regime switching model

JEL Clasification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Inflation targeting and economic performance over the crisis: evidence from emerging market economies

Asian Journal of Economics and Banking

ISSN : 2615-9821

Article publication date: 9 November 2021

Issue publication date: 1 November 2022

Inflation targeting has increasingly become a popular monetary framework since its first introduction in New Zealand at the beginning of 1990. However, the causality effects of this policy on economic performance, particularly in periods of economic turmoil remain controversial. Thus, this paper re-examines the treatment effect of inflation targeting on two important macro indicators which are inflation rate and output growth with the focus on emerging market economies. The global financial crisis, which is known as the great recession since the last decade, is investigated as an exogenous shock to test for the effectiveness of this popular regime.

Design/methodology/approach

The difference-in-difference approach in the fixed-model is employed for this investigation using a balanced panel data of 54 countries with 15 inflation-targeting countries for the period 2002 to 2010.

The examination finds that there is no significant difference in terms of the inflation rate and gross domestic product growth over the whole research period between the treatment and control groups. However, the outcome suggests that emerging economies can control the increase in inflation rate when the economy has to cope with the exogenous uncertainties.

Research limitations/implications

This finding indicates important policy implications for central banks in many countries.

Originality/value

Inflation targeting can help emerging countries to reduce an increase in inflation rate in the crisis period without many trade-offs in the growth of output.

- Inflation targeting

- Global financial crisis

- Emerging market countries

- Difference-in-difference approach

- Fixed model

Duong, T.H. (2022), "Inflation targeting and economic performance over the crisis: evidence from emerging market economies", Asian Journal of Economics and Banking , Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 337-352. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEB-05-2021-0054

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Thuy Hang Duong

Published in Asian Journal of Economics and Banking . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode .

1. Introduction

Many may continue to remember the global financial crisis which originated from the collapse of the US housing market in 2007, ruining several financial markets globally. This crisis is known as the Great Recession. Estimates from the International Monetary Fund ( IMF, 2010 ) show that real gross domestic product (GDP) growth in emerging and developing economies fell dramatically from 8.3% in 2007 to 6.1% in 2008, then to 2.4% in 2009. Inflation doubled in many countries during this period. While the consequences are on a global level, the magnitude of effects differed by country ( Claessens et al. , 2010 ).

As such shocks are risks in the context of the global economic integration, choosing a sound monetary framework to mitigate or even eliminate the consequences of economic disturbance is an important mandate for any central bank. In 1990, inflation targeting was first introduced by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand; gradually, it has been adopted by an increasing number of central banks as a strategy for monetary policy implementation. Under the inflation-targeting framework, the central bank officially announces a unique numerical target in the level or a range for annual inflation. Thus, this regime is expected to act as a guide for inflation expectations, assure a low and stable inflation rate and improve the central bank's credibility. However, to date, the effectiveness of this monetary framework remains controversial among policymakers and macroeconomists ( Ball and Sheridan, 2004 ; Vega and Wikelried, 2005 ; Stiglitz, 2008 ).

Numerous studies have been conducted to address whether inflation targeting matters ( Ball and Sheridan, 2004 ; Gonçalves et al. , 2006 ; Batini and Laxton, 2007 ; Lin and Ye, 2007 , 2009 ; Samarina et al. , 2014 ); nevertheless, significantly less analysis has been undertaken on evaluating this regime in the existing global economic downturn. On the empirical front, the work of Neumann and Von Hagen (2002) is one of few papers considering the impacts of inflation targeting implementation in periods of economic crisis. They compare the performance of inflation targeting and non-inflation targeting central banks under two exogenous shocks; namely, the oil price hikes of 1978 and 1998. Using the difference-in-difference approach with a sample of nine countries (six of which have adopted inflation targeting), they provide optimistic evidence about the performance of this policy in terms of lower levels of inflation, less volatile inflation and lower interest rates. Similarly, Miskin and Schimidt-Hebbel (2007) examine the macroeconomic and monetary policy performance of the inflation targeting policy before and after the oil price shock of 1997–1998 but use a more diverse sample of 34 industrial and emerging countries. The results from their panel vector autoregressive (panel VAR) models show that this monetary framework helps the targeters reduce the domestic inflation response to an oil price shock relative to periods before the adoption of inflation targeting and to the non-targeting countries. However, in terms of macroeconomic performance, Miskin and Schimidt-Hebbel (2007) find that emerging countries experienced major reductions in output as a trade-off for stable inflation.

Some recent studies focus on the global financial crisis of 2007–2008 to evaluate the treatment effects of inflation targeting. To the best of the author's knowledge, the first to publish on this theme is de Carvalho Filho (2010) , who used the fixed effects model for a sample of 84 advanced and emerging countries from January 2006 to August 2009 to compare inflation “targeters” and “non-targeters” in terms of the monetary policy responses and economic activity outcomes. His findings highlight the role of inflation targeting in smoothing this shock more effectively than the outcomes observed in their non-inflation targeting peers. Targeting countries enjoyed lower nominal policy rates, lower sovereign default risk and higher GDP growth rates in comparison to their counterparts. This conclusion regarding the positive impact of the inflation targeting policy on GDP growth is not supported by Armand (2012) . Considering the same control group and same break-date of the financial crisis of 2007 used by de Carvalho Filho (2010) , using the difference-in-difference models, Armand (2012) reveals an insignificant impact of this framework on GDP growth and inflation rate for both groups of countries.

Considered together, while these papers provide good evidence for treatment effects of inflation targeting policy on inflation control in the periods of economic disturbance, conclusions for the role of this policy in promoting GDP growth have limited consensus. Moreover, there are certain drawbacks of the empirical procedures in previous studies making their evaluation regarding the effectiveness of inflation targeting ambiguous. First , on the matter of the data, Blinder et al. (2008) suggest that the selection of the control group plays an important role in this line of research. Unfortunately, not all previous studies consider this issue carefully. Neumann and Von Hagen (2002) use a very small sample of three countries in the control group. Thus, it is unreasonable to generalize the treatment effect of the inflation targeting regime. In Miskin and Schimidt-Hebbel (2007) and de Carvalho Filho (2010) , the number of observations is larger, but no particular explanation of selected countries is provided. Second , the possibility of endogeneity is ignored in the difference-in-difference models of Neumann and Von Hagen (2002) . The adoption of inflation targeting is probably an endogenous choice considering different periods and unobserved macroeconomic situations. Hence, research that does not control for these initial conditions or for the time and country fixed effects tends to produce biased results. Following Ball and Sheridan's approach ( 2004 ), Armand (2012) controls the initial output when modeling the treatment effect of inflation targeting in an effort to deal with the endogenous issues. However, the satisfaction of the underlying assumption of a parallel trend in Armand's difference-in-difference approach ( 2012 ) appears to be ignored which could be against his conclusions considering a violated assumption.

Considering the shortcomings, this paper thus aims to re-evaluate the effectiveness of this popular monetary framework on the economy over the periods covering the global financial crisis. The important research questions whether a country that sets the inflation targeting as its primary monetary framework ( IT countries for short) can do better in terms of reducing the increase in inflation rate and accelerating the output growth during the crisis period in comparison to the countries that do not apply the inflation targeting framework ( non-IT countries for short) are addressed in this paper. This article contributes to the existing literature by providing a comprehensive analysis of inflation targeting impacts on the economy and dealing with the technical issues in previous studies. Specifically, panel data of 54 emerging countries (15 IT countries included) is exploited to simultaneously examine inflation and output outcomes from inflation targeting adoption. Instead of averaging the time-series observations, the author controls for time and country-specific dimensions to improve the inference on the causal effect of this framework. It is worth noting that both de Carvalho Filho (2010) and Armand (2012) evaluate the treatment effect of inflation targeting for periods before and during the global financial crisis in 2008–2009. Nevertheless, as the impact of this recession varied significantly across countries, it is not easy to distinguish if any estimated treatment impact is merely a function of treatment or includes the crisis. In this article, the author undertakes analyzes for the period 2002 to 2010 covering either pre- or post-crisis to avoid these confounding effects.

In contrast to some previous studies, this paper solely focuses on emerging economies as their similar characteristics could lead to a heterogeneous efficiency of inflation targeting regimes while coping with macroeconomics disturbances. Moreover, while many emerging markets experienced high volatility of the inflation and output before adopting inflation targeting, it is a fact that most advanced countries began this regime with relatively low and stable inflation ( Schaechter et al. , 2000 ). Hence, the inflation targeting adoption may not deliver important gains for the economy when considering advanced countries as observations. Furthermore, the main argument in favor of the inflation-targeting framework is that an improvement in credibility can be gained by central banks when they target a specific level or range of inflation. As central banks in emerging countries are likely to have significantly lower initial credibility than advanced peers ( Lin and Ye, 2009 ), it is reasonable to expect that the adoption of inflation targeting regime can substantially improve the credibility of such central banks, which leads to better policy effectiveness in developing countries.

The difference-in-difference fixed-effect model is employed to estimate the treatment effect of inflation targeting policy over the crisis period on two important indicators of the economy, namely inflation rate and output growth. For emerging economies, the study offers some evidence to suggest that inflation targeting is an effective policy that helps IT countries to avoid high inflation during economic uncertainties and maintain a similar performance in terms of output growth when compared to non-IT countries.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows. In Section 2 , the general background of the inflation-targeting framework is provided. Sections 3 and 4 discuss data and methodological issues, respectively. The empirical results for the treatment effects of inflation targeting regime on economic performance are reported in Section 5 . Sections 6 and 7 provide tests for the heterogeneity and robustness of estimates, respectively. Section 8 summarizes the main findings of the study and concludes.

2. Inflation targeting

2.1 what is inflation targeting.

The popularity of inflation targeting as an operational framework for monetary policy has been increasing since its introduction three decades ago. While this framework was restricted to a selected number of industrial countries for a certain period, in recent years, increasingly more emerging markets have been joining them in adopting this monetary policy regime. According to the International Monetary Fund's classification ( IMF, 2019 ), the number of IT countries significantly increased to 41 in 2019, and three-quarters of them were emerging countries ( Appendix Table A2 ). Although the inflation-targeting approach has been adopted in various ways, two main characteristics distinguish this nominal anchor from other monetary policy strategies as followed:

First, under an inflation-targeting framework, the central bank publicly announces a numerical level or range for annual inflation ( Gemayel et al. , 2011 ; Bernanke and Miskin, 1997 ). As targeting inflation directly requires the monetary authorities to forecast the likely path of prices, it is sometimes referred to as “inflation forecast targeting” ( Svensson, 1997 ). A variety of indicators needs to be closely monitored while considering this forward-looking assessment of inflation.

Second, in most cases, the primary focus of inflation considerably reduces the role of formal intermediate targets, such as exchange rate stability, output growth or unemployment rate ( Bernanke and Miskin, 1997 ; Batini and Laxton, 2007 ). Initial announcements of inflation indicators gradually transit from the current level of inflation to the desired inflation level, then to a steady-state level of price. To the extent that controlling inflation is inconsistent with intermediate goals, where the nominal exchange rate is unlikely to remain stable if the central bank reduces a high level of inflation by adjusting the policy interest rate or selling foreign currency from the national foreign-exchange reserve into the market. Thus, a clear mandate for the monetary authorities under the inflation targeting framework is attaining price stability rather than pursuing a multiplicity of monetary objectives.

2.2 Why can inflation targeting be expected to cope better than other regimes over periods of economic and financial downturns?

The existing literature offers some explanations of why inflation targeting can be a sound policy that can help countries mitigate risks from exogenous shocks. First , the inflation-targeting framework plays an important role not only in reducing high rates and volatility of inflation but also in preventing those targeting from persistent deflation which is a significant concern for monetary authorities in the post-crisis ( de Carvalho Filho, 2010 ; Ball and Sheridan, 2004 ; Vega and Wikelried, 2005 ; Lin and Ye, 2009 ). Second , the increasing credibility of policymakers in IT countries helps central banks face economic shocks with a significantly less contractionary monetary policy ( Lin and Ye, 2009 ; Neumann and Von Hagen, 2002 ). Third , the inflation targeting regime is generally accompanied by a flexible exchange rate regime ( de Carvalho Filho, 2010 ). The flexibility of the exchange rate is an essential factor that absorbs external shocks ( Bjørnland, 2004 ; Edwards et al. , 2005 ). Besides, in terms of fiscal policy performance, Lucotte (2012) and Tapsoba (2010) find that the treatment effects of inflation targeting on government revenues are positive and significant. Lucotte (2012) explains that this target encourages governments to strengthen the collection of domestic tax revenue as the monetary policy becomes tighter. An improved fiscal discipline acts as a beneficial condition for economic recovery in the post-crisis periods.

For each regression, this paper uses balanced panel data of annual series for the period 2002 to 2010, covering years before and after the global financial crisis. The sample countries comprise of 54 emerging countries, including 15 countries that adopted inflation targeting by the end of 2006 ( Table 1 ). Most of the data are collected from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF)'s International Financial Statistics.

The data set is divided into three sub-periods to evaluate the treatment effects of inflation targeting policy in smoothing the economic shocks. As the global financial crisis originated in mid-2007 following the collapse of the US housing market, the pre-crisis period consists of the 5 years preceding this crisis, from 2002 to 2006. As pointed in Armand (2012) , the consequences of this great downturn were notable until 2009. Thus, this paper examines the crisis period covering three consecutive years from 2007 to 2009. The year 2010 is also added to the baseline model as the post-crisis period to control the confounding effects of crisis consequences.

3.1 Dependent variables

The outcome variables considered in this study are the annual inflation rate and annual output growth which represent the economic performance in each country. In this paper, the annual inflation rate is defined as the percentage of changes in the annual Consumer Price Index (CPI), while output growth is measured by the percentage of changes in the annual real GDP.

Figures 1 and 2 represent a comparison of the average inflation rates between pre- and post-adoption of inflation targeting in IT countries from 1985 to 2002 and that between IT countries and non-IT countries during the study period 2002 to 2010, respectively. Similar comparisons of the average output growth are shown in Figures 3 and 4 . In Figures 1 and 3 , year T is the first year when the inflation targeting policy in each IT country started, and (…, T − 2, T − 1, T + 1, T + 2, …) are one or two years before and after the year T (i.e. if an IT country starts the inflation targeting policy in 2000, then T = 2000, T + 1 = 2001, T − 1 = 1999). The adoption years are when countries officially set inflation targeting as the nominal anchor of monetary policy based on IMF classification. The inflation rate and output growth in these two figures are the mean values of the inflation rate and GDP growth in countries that have the same year T . In Figures 2 and 4 , the inflation rate and output growth are the mean values of the CPI growth and the GDP growth in the treatment group (IT countries) and the control group (non-IT countries) over different periods.

The preliminary results emerging from these figures suggest some noticeable points. First , IT countries experienced periods of high and volatile inflation before implementing the inflation targeting policy, but this rate reduced remarkably and was controlled at low and stable rates since the monetary framework came into effect. Meanwhile, the differences in the average GDP growth in pre- and post- IT adoption in IT countries were not apparent. Second , on average, IT countries had significantly lower inflation rates than non-IT countries during the 11-year study period, particularly in the crisis period. The average inflation in treatment countries was only approximately 7% in 2008, while that in the control group was 17% in that year. Generally, there was no significant difference in the GDP growth between these two groups of countries in Figure 4 (except for 2009). These plots seem to indicate that IT countries tend to control inflation rates better than non-IT countries in periods of economic turmoil, while the tradeoffs of GDP growth are not too severe.

3.2 Control variables and sample countries

The control variables used in the analysis include variables that could explain the probability that an emerging country chooses specific inflation as a monetary target: the fixed exchange rate dummy variable, the growth of money supply aggregate (M2), trade openness and government debt. All these, except for the exchange rate variable, are described in the percentage of output (GDP). The summary statistic of these control variables and dependent variables is represented in Appendix Table A1 .

The treatment group includes 15 emerging market countries that adopted inflation targeting by the end of 2006. As explained in the previous sub-section, the policy adoption years are based on IMF classification. These years are mentioned as “conservative starting years” in Rose (2007) and Lin and Ye (2009) . Considering the control group, non-IT countries, this paper follows the selection criterion used in Lin and Ye (2009) to form two groups of countries that can be compared. In specific, the control group includes only non-targeting developing countries that simultaneously satisfy conditions of a real GDP per capita at least as large as the poorest targeting country, and that of population size at least as large as that of the smallest targeting country. According to these criteria, the control group for this subsample consists of 39 countries. Table 1 lists a total of 54 targeting countries and non-targeting developing countries, and the years in which those targeting officially adopted the inflation targeting regime.

In comparison to the sample countries in Lin and Ye (2009) , this paper includes three IT countries in the treatment group, namely Indonesia, Guatemala and Romania, as these countries adopted inflation targeting since 2005 and satisfied the criteria mentioned. Israel is removed from the sample as it was promoted from an advanced emerging market to a developed country on 19 September 2008 according to the classification of FTSE Russell ( FTSE, 2020 ). Thus, Israel has exceeded this paper's content in evaluating the treatment effects of inflation targeting among emerging countries. Another noteworthy point is that Poland became an advanced country in 2018. However, the year 2018 is not examined in this study; thus, Poland is suitable to be treated in the treatment group.

4. Methodology

The main objective of this study is to test the (null) hypothesis that the inflation targeting framework improves the economic performance in terms of the inflation rate and output growth in the IT countries during periods of economic uncertainty when the global financial crisis is taken into account. The difference-in-difference (DID for short) approach is used to provide the evaluation of inflation targeting impacts on these dependent variables. The DID model can compare treatment and control groups in terms of outcome changes over time. Thus, it is suitable to be employed in this case. Moreover, in comparison to some other quasi-experimental methods, the DID estimator is recognized to avoid selection bias by allowing for unobserved heterogeneity ( Khandker et al. , 2010 ). The DID assumes this unobserved heterogeneity is time-invariant. As such, the bias dies out by differencing. As the adoption of inflation targeting may be an endogenous choice depending on the economic situation over different periods ( Ball and Sheridan, 2004 ), the DID approach is estimated in the fixed-effect model to remove unobserved time-invariant confounders.

The DID specification in the panel fixed-effects is estimated by Equation (1) as follows: (1) Y i t = α 1 + α 2 T i t + α 3 I i t + α 4 Z i t ′ + θ t + w i + ε i t

In Equation (1) , subscripts i and t represent individual countries and year, respectively; Y is the dependent variables which represent inflation rate and output growth; T is a dummy variable denoting inflation targeting implementation in the crisis period, which takes on the value of one for years from 2007 to 2009 in IT countries, else zero; I is a dummy variable denoting the adoption of inflation targeting for all the study period, which equals one for all years after the adoption, else zero; Z' includes covariate variables, detailed below; θ are time fixed effects; w are country fixed effects, which control for time-invariant impacts on economic performance across countries; ε is the error term; and α 1 , α 2 , α 3 and α 4 are the parameters to be estimated. The examination focuses on α 2 and α 3 which represent the estimated treatment effect of the inflation targeting policy during the crisis period and since the adoption in IT countries, respectively.

Covariate variables include the dummy variable for the fixed exchange rate regime, the growth of money supply aggregate (M2), trade openness and government debt.

Granger-type causality test : The first and second leads of the treatment dummy variable are added to Equation (1) to examine the possibility that future treatment exposures are anticipated by current outcomes. Under the key assumption, future policy changes are expected to not be associated with current outcomes. Thus, the estimated coefficients of these leads should be statistically insignificant.

Group-specific linear time trend : Each group effect interacts with the linear time index, then this interaction term is added to Equation (1) . The common trend suggests that these group-specific linear time trends should be jointly insignificant. An F -test of the compound null is used to check for insignificance.

Covariate balance test: The DID validity assumes that differences between the two groups are stable over time; thus, changes in the distribution of covariates do not affect treatment exposure. In this approach, the DID validity is examined by estimating covariate balance regressions. In Equation (1) , the outcome variable is replaced with covariates. Then, each covariate is regressed against the treatment variable and group, and year fixed effects. The estimated coefficients attached to the treatment variable should be insignificant in all or almost all regressions for a valid assumption.

5. Empirical results and interpretations

Equation (1) is estimated for both the inflation rate and output growth from 2002 to 2010. As mentioned in the previous section, estimation for the DID model is applied in the fixed effects approach. Standard errors are clustered at the country level to eliminate the serial correlation over time within groups. All regressions include constant, covariate variables as specified in the text, fixed time effects and fixed country effects. The outcomes from the DID fixed effect approach are reported in Table 2 .

As per Table 2 , the estimated coefficient associated with inflation targeting implementation (IT implementation) is statistically insignificant as the inflation rate is the dependent variable. This output suggests that the inflation targeting framework has no apparent impact on the inflation rate in IT countries after the adoption, all else remaining unchanged. However, during the crisis period, the impact of inflation targeting on the inflation rate is statistically significant at 5% level. The specific results show that by applying inflation as the priority target, emerging economies can reduce the annual inflation rate by 2.2% relative to the non-IT group when the economy faces uncertain events.

The estimated treatment effect of the inflation targeting policy on output growth is represented in the two last columns in Table 2 . As the GDP growth is the dependent variable, the estimates for the inflation targeting implementation in emerging economies are statistically insignificant in either the crisis period or the stable period, all else remaining the same. Thus, in comparison to countries that pursue other primary monetary frameworks, rates of GDP growth in IT countries do not increase or decrease significantly via the inflation targeting policy over different periods.

These outcomes indicate that the inflation targeting policy helps emerging economies lower their inflation rate without placing a heavy burden on the output growth during an economic disturbance. This finding is consistent with the preliminary analysis in Section 3 which plots the remarkably lower rate of inflation in IT countries relative to the control group during the crisis period. The significant impacts of inflation targeting regime on lowering inflation rate covering the periods of economic shocks also fit with the extant literature, such as Neumann and Von Hagen (2002) , Miskin and Schimidt-Hebbel (2007) and de Carvalho Filho (2010) . In terms of output growth, the treatment effects of this monetary framework are insignificant which are supported by the conclusions in Armand (2012) . However, Miskin and Schimidt-Hebbel (2007) and de Carvalho Filho (2010) have contrast results to this paper in terms of the impacts on GDP growth. As mentioned in Section 1 of this paper, this difference could stem from the limitations of prior works in choosing improper control groups as well as dealing with selection bias issues.

The outcomes of the parallel trend tests based on Wing et al. 's (2018) approach are represented in Appendix Table A3 . Only the results of the main interests are shown in the table. As the table shows, two out of three tests support DID validity. The tests for the Granger-type causality procedure are implemented on estimates regarding the impact of inflation targeting policy on both dependent variables. Neither the first nor the second lead of the dummy variable of inflation targeting implementation have significant impacts on the inflation rate and output growth. The initial outcomes are not affected by anticipated effects; thus, the key assumption in the DID model appears to be valid in this approach.

This assumption is also satisfied by the covariate balance test. The specific results show that there is no estimated coefficient of the dummy variable for IT implementation which is statistically significant at 1 and 5% levels. This outcome indicates that the estimated treatment effect is not associated with changes in the distribution of covariates; hence, the estimates are stable over time. Only the test for group-specific linear time trend suggests that the parallel trend assumption should be problematic as the null hypothesis for the joint test of insignificant time-trend interaction terms is rejected. However, the assumption violation in this group-specific linear time trend test means that the core results should be considered more credible ( Wing et al. , 2018 ) rather than concluding them to be false. This paper proceeds with procedures for the heterogeneity and robustness of estimates in the DID models and analysis to ensure that the initial outcomes in the baseline models are robust and stable.

6. Heterogeneity analysis

In order to control for the heterogeneity within the sample, this paper runs regressions of the treatment effect of inflation targeting regimes across two sub-groups based on the level of trade openness. In this paper, trade openness is defined as the sum of exports and imports of goods and services measured as a share of GDP. The average percentage of trade openness for sample countries for the study periods from 2002 to 2010 is approximately 60%. Thus, this rate is used to divide countries into two sub-groups. Table 3 represents the outcomes of the heterogeneity test. Similar to previous tables, only the results of the main interests are provided. As per this table, the inflation targeting implementation has a negative and significant impact on the inflation rate during the crisis period in both sub-groups, while the impacts of this policy on output growth are not apparent as the economy copes with the exogenous shock. These results suggest that there is no heterogeneity treatment effect across the groups of trade openness levels. Thus, the estimated treatment effect of inflation targeting in initial results is stable across the sub-groups.

7. Robustness check

The Granger-type causality test in Section 5 suggests that estimates for the treatment variable do not change significantly as these leads are included in the model; thus, the initial outcomes in the baseline models are robust. In this section, the paper considers the year 2008 rather than 2007–2009 as the crisis period to further check the robustness of the estimated treatment effect. The dependent variable is now the changes in inflation and output growth between the crisis period 2008 and years before and after this event for the period 2002–2010. Table 4 reports the outcomes of this estimation. As observed in the table, the estimated coefficients associated with the IT dummy variables are not significantly different in comparison to the initial results. The estimated treatment effects of the inflation targeting on inflation rate are still insignificant in comparison to the pre- and post-policy adoptions during stable periods. However, inflation targeting works well in controlling the inflation rate during economic turmoil periods in IT countries relative to non-IT countries. When the output growth acts as the dependent variable, there is no significant difference between IT and non-IT countries in terms of the performance of this indicator during different periods covering the crisis. This outcome confirms that driven findings in this paper are robust.

8. Summary and conclusions

The increasing popularity of inflation targeting as a monetary framework over the last three decades partially suggests the effectiveness of this policy; however, the empirical evidence on its impact on economic performance shares limited consensus. This paper contributes to the existing research by conducting a comprehensive analysis of the treatment effect of inflation targeting two macro indicators, namely inflation rate and output growth, over the period of the global financial crisis which was considered a great recession starting in 2007. In doing so, the effectiveness of this popular monetary framework in mitigating consequences from such exogenous economic uncertainties is carefully examined.

The preferable methodological approach in this line of research – the DID model-is employed in this paper. The endogeneity of the IT regimes stemming from time-invariant factors is controlled in a fixed-effect model for the period 2002 to 2010. The sample countries consist of 54 emerging economies with 15 IT countries. When examining the case of emerging countries, the empirical results from this study indicate that inflation targeting reduces the inflation rate during the crisis period, even though the impact of this policy on the inflation indicator is insignificant during the stable periods. In terms of output growth, the inflation targeting regime does not make significant changes within the IT countries, as well as between the IT and non-IT countries over the periods covering the crisis period. This finding has proved to be robust and stable over sub-groups.

The evidence of this study does not conclude that inflation targeting is the best monetary framework and all countries must adopt it. The outcomes indicate that inflation targeting matters and works well in controlling the inflation rate when emerging countries face an exogenous shock as the global financial crisis in 2007 without significant trade-off performance of output growth. Thus, countries can consider this policy when aiming to stabilize prices during a such crisis.

This study can be extended by examining the impact of inflation targeting on other macro factors of economic performance, such as volatility of inflation rate and output growth, unemployment rate or industrial production performance. While doing this, emerging countries should have a more general view of the effectiveness of this monetary framework on the economy.

Average inflation rate in IT countries

Average inflation rate from 2002 to 2010 in IT and non-IT countries

Average GDP growth in IT countries

Average GDP growth from 2002 to 2010 in IT and non-IT countries

Sample countries

Emerging market and industrial countries that have adopted inflation targeting

Note(s): All regressions include constant, covariate variables as specified in the text, fixed time effects, and fixed country effects. Robust standard errors are in parentheses which are clustered at the country level. ** and * indicate statistical significance at the 5 and 10% level, respectively

Source(s): Author's calculation

Armand , A. ( 2012 ), Coping with the Recent Financial Crisis, Did Inflation Targeting Making Any Difference? , University of Orléans , Rue de Blois .

Ball , M. and Sheridan , N. ( 2004 ), Does Inflation Targeting Matter? , National Bureau of Economic Research, University of Chicago Press , Chicago , pp. 249 - 282 , doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226044736.003.0007 .

Batini , N. and Laxton , D. ( 2007 ), “ Under what conditions can inflation targeting be adopted? The experience of emerging markets ”, in Miskin , F. and Schmidt-Hebbel , K. (Eds), Monetary Policy under Inflation Targeting , Central Bank of Chile , pp. 1 - 38 .

Bernanke , S. and Miskin , S. ( 1997 ), “ Inflation targeting: a new framework for monetary policy? ”, Journal of Economic Perspective , Vol. 11 No. 2 , pp. 97 - 116 , doi: 10.1257/jep.11.2.97 .

Bjørnland , H.C. ( 2004 ), “ The role of the exchange rate as a shock absorber in a small open economy ”, Open Economies Review , Vol. 15 No. 1 , pp. 23 - 43 , doi: 10.1023/B:OPEN.0000009423.30895.fe .

Blinder , S. , Ehrmann , M. , Fratzscher , M. , De Hann , J. and Jansen , D. ( 2008 ), “ Central bank communication and monetary policy: a survey of theory and evidence ”, Working Paper No.13932 , NBER . doi: 10.3386/w13932 .

Claessens , S. , Aruccia , G. , Igan , D. and Laeven , L. ( 2010 ), “ Cross-country experiences and policy implications from the global financial crisis ”, Economic Policy , Vol. 25 No. 62 , pp. 267 - 293 , doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0327.2010.00244.x .

de Carvalho Filho , I. ( 2010 ), “ Inflation targeting and the crisis: an empirical assessment ”, Working Paper, No.10/45 , IMF , pp. 1 - 22 . doi: 10.5089/9781451963045.001 .

Edwards , S. and Yeyati , L. ( 2005 ), “ Flexible exchange rates as shock absorbers ”, European Economic Review , Vol. 49 No. 8 , pp. 2079 - 2105 , doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2004.07.002 .

FTSE Russell ( 2020 ), “ Equity country classification ”, FTSE , available at: https://www.ftserussell.com/equity-country-classification ( accessed 12 October 2020 ).

Gemayel , R. , Jahan , S. and Peter , A. ( 2011 ), “ What can low-income countries expect from adopting inflation targeting? ”, Working Paper WP/11/276 , IMF . doi: 10.5089/9781463925932.001 .

Gonçalves , S. and Salles , M. ( 2006 ), “ Inflation targeting in emerging economies: what do the data say? ”, Journal of Development Economics , Vol. 85 Nos 1-2 , pp. 312 - 318 , doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2006.07.002 .

International Monetary Fund (2005, 2008) , ( 2010 ), World Economic Outlook , International Monetary Fund , Washington, Distict of Columbia .

International Monetary Fund ( 2019 ), Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (AREAER) , International Monetary Fund , Washington, District of Columbia .

Khandker , R. , Koolwal , B. and Samad , A. ( 2010 ), Handbook on Impact Evaluation: Quantitative Methods and Practices , The World Bank , Washington, District of Columbia . doi: 10.1596/978-0-8213-8028-4 .

Lin , S. and Ye , H. ( 2007 ), “ Does inflation targeting really make a difference? Evaluating the treatment effect of inflation targeting in seven industrial countries ”, Journal of Monetary Economics , Vol. 54 No. 8 , pp. 2521 - 2533 , doi: 10.1016/j.jmoneco.2007.06.017 .

Lin , S. and Ye , H. ( 2009 ), “ Does inflation targeting make a difference in developing countries? ”, Journal of Development Economics , Vol. 89 No. 1 , pp. 118 - 123 , doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.04.006 .

Lucotte , Y. ( 2012 ), “ Adoption of inflation targeting and tax revenue performance in emerging market economies: an empirical investigation ”, Economic Systems , Vol. 36 No. 4 , pp. 609 - 628 , doi: 10.1016/j.ecosys.2012.01.001 .

Miskin , S. and Schimidt-Hebbel , K. ( 2007 ), “ Does inflation targeting make a difference? ”, Working Paper No.12876 , NBER . doi: 10.3386/w12876 .

Neumann , M. and Von Hagen , J. ( 2002 ), “ Does inflation targeting matter? ”, Working Paper, B 01-2002 , ZEI . doi: 10.20955/r.84.127-148 .

Roger , S. ( 2010 ), “ Inflation targeting turns 20 ”, Finance and Development , Vol. 47 No. 1 , pp. 46 - 49 .

Rose , A. ( 2007 ), “ A stable international monetary system emerges: inflation targeting is Bretton woods, reserved ”, Journal of International Money and Finance , Vol. 26 No. 5 , pp. 663 - 681 , doi: 10.1016/j.jimonfin.2007.04.004 .

Samarina , A. , Terpstra , M. and De Hann , J. ( 2014 ), “ Inflation targeting and inflation performance: a comparative analysis ”, Applied Economics , Vol. 46 No. 1 , pp. 41 - 56 , doi: 10.1080/00036846.2013.829205 .

Schaechter , A. , Stone , R. and Zelmer , M. ( 2000 ), Adopting Inflation Targeting: Practical Issues for Emerging Market Countries , International Monetary Fund, Publication Services , Washington, District of Columbia .

Stiglitz , J.E. ( 2008 ), The Failure of Inflation Targeting , Project Syndicate , available at: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/the-failure-of-inflation-targeting .

Svensson , L.E.O. ( 1997 ), “ Inflation targeting in an open economy: strict or flexible inflation targeting ”, Reserve Bank of New Zealand Discussion Paper Series G97/8, Reserve Bank of New Zealand .

Tapsoba , R. ( 2010 ), “ Does inflation targeting improve fiscal discipline? An empirical investigation ”, Working Papers 201020 , CERDI .

Vega , M. and Winkelried , D. ( 2005 ), “ Inflation targeting and inflation behavior: a successful story? ”, International Journal of Central Banking , Vol. 1 No. 3 , pp. 153 - 175 .

Wing , C. , Simon , K. and Bello-Gomez , A. ( 2018 ), “ Designing difference in difference studies: best practices for public health policy research ”, Annual Review of Public Health , Vol. 39 , pp. 453 - 469 , doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013507 .

Further reading

Central Bank News ( 2020 ), Inflation Target , CentralBankNews.info . available at: http://www.centralbanknews.info/p/inflation-targets.html ( accessed 12 October 2020 ).

Nagy , L. ( 2016 ), “ From independent Slovakian Central Bank policy to the monetary policy of the euro area ”, Focus: New Central Bank Policies, Public Finance Quarterly 2016/1 , pp. 49 - 64 .

Nell , M. ( 2004 ), “ Monetary policy in the Slovak Republic. Implicit inflation targeting and the choice of an optimal exchange rate regime ”, BIATEC , Vol. 12 No. 11 , pp. 1 - 23 .

Williard , L. ( 2012 ), “ Does inflation targeting matter? A reassessment ”, Applied Economics , Vol. 44 No. 17 , pp. 2231 - 2244 , doi: 10.1080/00036846.2011.564136 .

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Professor Blane D. Lewis and Mr. Phan Le for the guides and comments that helped significantly improve the quality of this study. Any errors and shortcomings, if any, remain the author's responsibility.

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Inflation, inflation uncertainty and the economic growth nexus: An impact study of South Africa

Inflation and inflation uncertainty are instrumental in the determination of financial stability, and ultimately, economic growth. We investigated the impact of inflation and inflation uncertainty on growth in South Africa by applying the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) estimation techniques on quarterly data covering the period 1961Q1 to 2019Q4. Unlike previous studies on South Africa, we investigated the joint impact of inflation and inflation uncertainty in South Africa, and also, pioneered in comparing the impact of both variables on growth before, and after, inflation targeting. This provided an opportunity to assess the effectiveness of inflation targeting while also investigating any changes in the behavior of the variables. We found that inflation negatively harms growth in both the short and long run, while inflation uncertainty is a short-run phenomenon in South Africa with no bearing in the long run. To promote growth, policymakers should continue to pursue policies that ensure price stability.

• The paper investigated the impact of inflation and inflation uncertainty on economic growth in South Africa covering the period 1961Q1 to 2019Q4.

• Using the autoregressive distributed lag estimation techniques, the paper found that inflation harms economic growth in both the short- and long-run in South Africa while inflation uncertainty is a short-run phenomenon as it affects economic growth only in the short run,

• Interestingly, after adoption of inflation targeting, inflation uncertainty lost it relevance as a factor determining economic growth in South Africa.

Graphical abstract

Specification table

Introduction

The impact of inflation on economic growth has been the subject of macroeconomic research and debates for quite a long time. The bone of contention, particularly, hovers on the debate on whether inflation impacts economic growth negatively or positively. One of the questions often raised is whether it is inflation that affects growth, or if it is uncertainty about inflation that upsets or motivates investment decisions and in turn affects growth [28] . Judson and Orphanides [43] caution that the debate surrounding inflation and growth is seldom settled because of estimation errors due to the omission of inflation uncertainty, which is a relevant variable in the determination of growth. Although literature is rich with studies concerning the relationship between inflation and economic growth, it is however, interesting to note that most scholars turn a blind eye to the impact of inflation uncertainty on economic growth. The pioneering work on inflation uncertainty was spearheaded by Tobin [69] who reasoned that inflation uncertainty induces households to hold more real capital assets, thereby stimulating capital productivity and economic growth. Tobin [69] , in line with Mundell [51] , were of the opinion that price instabilities provide room for growth.

The stagflation of the 1970s, stemming mainly from increases in oil prices, debunked the ideas and casted doubts on the existence of a positive relationship between inflation and economic growth. Theoretical studies took a different trajectory, with studies from Okun [60] , Friedman [28] , Stockman [67] and Ball [9] , explaining that price instability inhibits economic growth. The debate spills over to empirical studies which have contrasting conclusions. For instance, among others, Judson and Orphanides [43] , Grier and Perry [31] , Grier, Henry, Olekalns and Shields [30] , Apergis [5] as well as Iyke and Ho [38] documented a negative relationship between either inflation, or inflation uncertainty or both, and economic growth. In contrast, Coulson and Robins [20] , Jansen [39] and Fountas [25] reported a positive relationship among the variables. The debate also extends to empirical results between and within industrialised countries and emerging economies.

South Africa's significance in Africa as the financial capital and its influential role as a member of the Common Monetary Area (CMA) under the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) motivated the choice of South Africa in the paper. The history of price instabilities in South Africa dates from as far back as the 1960s. Several policies have been pursued to tame inflation, but with little success, until the adoption of inflation targeting in 2000. It was the adoption of inflation targeting which triggered the fierce debate over the relationship between price stability and economic growth in South Africa. At one end, Hodge [36] with the concurrent support from pressure groups such as the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) (see [58] and [21] ) pose that South Africa can make use of higher rates of inflation to accommodate growth. At the other end, Nell [57] , Niyimbanira [59] , Munyeka [52] and Kumo [45] find that high inflation harms economic growth. It is against this background that this paper endeavours to enrich literature by examining inflation, inflation uncertainty and the economic growth nexus in South Africa during the period 1961Q1 to 2019Q4. Although the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) bounds testing procedure is a widely used estimation technique in academic circles, this paper will be the first to make use of it in estimating inflation, inflation uncertainty and the growth nexus in South Africa. The ARDL bounds testing procedure suits the purpose of the study since it separates the long-run impact from the short-run impact, necessitating the paper to quantify the long-run and short-run impacts of the variables separately. Furthermore, according to the best of our knowledge, none of the studies on South Africa estimated the joint impact of both inflation and inflation uncertainty, which may have led to estimation errors from omitting a relevant variable, and accordingly, this paper pioneers in estimating the joint effect of the variables on economic growth in South Africa. Also, this paper has estimated the joint impact of inflation and inflation uncertainty before and after inflation targeting, thereby assessing the effectiveness of inflation targeting while also investigating any changes in behavior of the variables.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents the dynamics of inflation, inflation uncertainty and economic growth in South Africa between 1960 and 2019. Section 3 reviews the theoretical and empirical literature on inflation, inflation uncertainty and the economic growth nexus. Section 4 presents the data and the empirical methodology while Section 5 discusses the empirical results and Section 6 concludes the paper.

The dynamics of inflation, inflation uncertainty and economic growth in South Africa (1960 to 2019)

Sluggish economic growth, which is characterised as not pro-poor and having a very low employment coefficient, has become one of the befitting hallmarks of the South African economy [73] . Despite efforts to stimulate economic growth using different policies (see Table 1 ), economic growth remained sluggish and falling to average rates closer to 0 – with 1.0935% being the average rate of growth between 2013 and 2019 as shown in Table 1 . In terms of inflation, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) has largely been successful in its fight for price stability [49] . Table 1 shows the rates of inflation and economic growth under different government and monetary policies between 1960 and 2019. The trends show that the rate of inflation has been high before the adoption of inflation targeting, with an average of 9.415%, while under inflation targeting, the rate of inflation averaged 5.307% as shown in Table 1 . However, economic growth was slightly higher before inflation targeting, as compared to the inflation targeting era.

Rates of inflation and economic growth under different government and monetary policy regimes between 1960 and 2019.

Source: Authors’ compilations based on data from SARB (2020) and IFS (2020).

The data in the table shows that the average rate of inflation dropped by 77%, from an average of 9.415% before the adoption of inflation targeting to 5.307% under inflation targeting, which can be attributed to the inflation targeting policy adopted by SARB in 2000. During the same period, the rate of economic growth decelerated by nearly 18%, from 3.107% before the adoption of inflation targeting to 2.641% after the adoption of inflation targeting.

It is also of significant importance to introduce the trends in inflation uncertainty during this period. Fig. I introduces inflation uncertainty trends from 1960 to 2019. The trends show that inflation uncertainty in South Africa moves in tandem with the rate of inflation; for instance, when inflation was high in the early 1980s, inflation uncertainty was also high; and when inflation was low after 2010, inflation uncertainty was also low. Particularly important to note from the trends is that inflation uncertainty has been on a downward spiral since the year 2000 when SARB adopted the inflation targeting policy.

Inflation, inflation uncertainty and economic growth trends (1960 to 2019).

Inflation, inflation uncertainty and economic growth: a theoretical and empirical review of literature

Literature shows that the debate on the relationship between inflation and growth dates back from the classical school of thought through to the new classical school of thought. The classical school reasons that competition for labor by capitalists increases the cost of labor as well as the costs of production which exert pressure on prices in the economy. The increase in costs of production erodes the capitalists’ profits, discouraging them from production. Accordingly, this implies a negative relationship between inflation and economic growth in both the short and the long run (see [68] and [35] ). In contrast, the Keynesians argue that demand for labor reduces unemployment while increasing economic growth, and it results in higher nominal wages and inflation as its by-products, hence a positive relationship in the long run [1] . Monetarists offer a distinguished view: They deduce that workers suffer from money illusion temporarily in that any increase in nominal wages (and inflation) induces workers to increase their supply of labor (and economic growth) temporarily before reverting to the original supply of labor – hence, inflation has no relationship with economic growth in the long run, but a positive one in the short run [47] . The new classicals, whose theory rests on the tenet of rational expectations, stress that inflation is not related to economic growth in both the short and the long run [48] . The bone of contention extends to different scholars and bodies of theory. The debate surrounding the theory is still ongoing and inconclusive. Although these economic schools of thought explain the relationship between inflation and economic growth, they do not explain the role of inflation uncertainty in the determination of economic growth.

It is interesting to note that the role of inflation uncertainty on economic growth was only introduced as late as 1965 in a study by Tobin [69] . It is only since then that scholars gained interest in the impact of inflation uncertainty on economic growth. Tobin [69] proposes that an increase in inflation uncertainty leads to a decline in accumulated wealth, prompting households to hold less non-interest-bearing assets but more real capital assets. As a result, these actions by households stimulate capital productivity and result in an increase in economic growth. Tobin [69] further outlines that under inflationary conditions, savings, investment spending and government spending increase which stimulate economic growth.

In the same vein, Ungar and Zilberfarb [70] theoretically argue that high inflation and its uncertainty induce economic agents to invest more in generating accurate forecasts on future values. This lessens inflation uncertainty over time as economic agents generate accurate predictions of future inflation. These accurate predictions, in a way, help in making informed investment decisions, which may promote investment spending, culminating in an increase in economic growth. In support, studies by Aghion and Saint-Paul [2] and Blackburn [11] demonstrate that inflation and inflation uncertainty lower the opportunity cost of investing in capital or labor resources in technological improvements, which stimulates investment spending, and ultimately economic growth. Induced by the stagflations of the 1970s, Friedman [28] queried the positive relationship between economic growth and inflation; and informally argued that inflation weakens the price mechanism, thereby harming economic growth.

Earlier on, Okun [60] had also revisited the relationship and suggested that inflation uncertainty exposes wealth and incomes to a greater risk since individuals forgo the purchase of goods to cushion them against the possible decrease in their real incomes, thereby harming economic growth. Citing the explanations given by Okun [60] as loosely structured while attempting to formalize the hypothesis given by Friedman [28] , Ball [9] explained that high rates of inflation generate inflation uncertainty and uncertainty about future monetary policy. The public casts doubt on the monetary policy authorities during periods of high inflation, which negatively affect the credibility of monetary policy authorities. In the same vein, an increase in inflation uncertainty inhibits decision making by the public, thereby negatively affecting economic growth.

The argument also extends to empirical findings. The existing literature suggests that inflation and inflation uncertainty could hurt or enhance economic growth. First, there are studies that focused on the impact of inflation on economic growth without controlling for the role of inflation uncertainty. These studies derived two conclusions – either a negative relationship or the existence of the threshold effects. For example, De Gregorio [22] , Gylfason and Herbertsson [34] , Gillman, Harris and Mátyás [29] , Barro [10] and Niyimbanira [59] found that inflation harms economic growth, while studies such as Sarel [64] , Bruno and Easterly [16] , Khan and Senhadji [44] , Yilmazkuday [75] , Ndoricimpa [55] and Phiri [63] challenged the notion of a monotonic relationship between inflation and economic growth and noted the presence of a threshold level of inflation, below which inflation enhances growth while hurting growth above that level.

Second, there are studies that mainly focus on the impact of inflation uncertainty on economic growth without focusing on the role of inflation. These studies obtained either a positive or a negative relationship between inflation uncertainty and economic growth. A positive relationship is documented by studies such as Coulson and Robins [20] , Jansen [39] as well as Bredin, Elder and Fountas [15] while, in contrast, Grier and Perry [31] , Grier, Henry, Olekalns and Shields [30] , Apergis [5] and Baharumshah, Hamzah and Sabri [7] , among others, found a negative relationship.

Finally, there are studies that included both inflation and inflation uncertainty in their analysis, and they arrived at mixed conclusions. A certain quarter of studies found that both variables negatively inhibit growth (see [43] ; Rother, 2004; [72] ; as well as [38] , among others). In contrast, Fountas [25] argued that inflation uncertainty positively impacts economic growth. Adding to the pool of inconclusive results, Grier and Tullock [32] concluded that under the condition of low inflation uncertainty, high inflation has no effect on economic growth while Clark [19] disputed the existence of a relationship between either inflation or inflation uncertainty and economic growth. Moreover, Fountas, Ioannidis and Karansos [26] obtained different results from different countries, hence inconclusive results. Baharumshah, Slesman and Wohar [8] obtained a negative relationship between inflation and economic growth, but a positive relationship between inflation uncertainty and economic growth. This leaves this category with no definite answers but with contrasting answers on the relationship.

It is interesting to note that although literature on the inflation-growth nexus on the South African economy is rich, none of the studies focused on the joint impact of inflation and inflation uncertainty on economic growth. Studies that investigated the impact of inflation on economic growth found that inflation harms growth efforts in South Africa (see [57 , 59] and [52] ), while those that focused on inflation uncertainty also found that inflation uncertainty harms economic growth (see [56] and [45] ). Some studies, for example Phiri [63] , obtained a non-linear relationship between inflation and economic growth while Hodge [36] documented that inflation positively affects growth in the short run, but negatively in the long run. This paper pioneers in investigating the joint impact of inflation and inflation uncertainty in South Africa.

Data and methodology

Data sources.

This study uses quarterly time-series data, covering the period 1961Q1 to 2019Q4, obtained from the SARB (2020) and International Financial Statistics [ [37] (2020]. The timespan of the data is limited to 1961Q1, and not periods before, due to the availability of data. The data ends at 2019Q4 and do not include 2020 due to the economic lockdowns from the prevalence of Covid-19 in 2020, which disturbed production and economic growth. However, although the dataset we used also includes the 2007/8 global financial crisis, a study by Armand [6] found evidence that the financial crisis did not impose any significant differences with regards to the inflation rates and GDP growth for inflation targeting economies. Nevertheless, after reporting on the main empirical results, we proceeded with robustness tests where we included a dummy variable to accommodate the financial crisis.

Definitions and justifications of variables

Economic growth

Economic growth is the dependent variable in the study. [66] (n.d.) measures economic growth using two different approaches: firstly, the quarterly growth rate of real gross domestic product (GDP) at a seasonally adjusted and annualized rate; and secondly, unadjusted year-on-year quarterly growth of real GDP. Although seasonally adjusted quarterly growth at an annualized rate is used as the official growth rate, irregular occurrences in specific quarters may render the data volatile. To circumvent this weakness, this paper measures economic growth using the unadjusted year-on-year quarterly growth of real GDP since it eliminates the impact of seasonal variations.

The consumer price index (CPI) is the standard index used to calculate the rate of inflation in South Africa [65] . Different measures of inflation are used, such as month on same month of previous year, month on previous month at an annual rate, quarterly average on previous quarterly average at an annual rate and quarter on quarter of previous year [50] . This paper uses the quarter on quarter of previous year measure. This method is chosen for its alignment and consistency with the method used for calculating economic growth in this paper. The inflation rate is expressed as a percentage.

Inflation uncertainty

Inflation uncertainty, defined by Grier and Perry (1998) as unpredictable volatility in the general prices, is an unobserved variable. Inflation uncertainty can be measured ex-ante, that is, before the period of inflation has passed; or ex-post, which is measured after the inflation period has occurred. This paper uses ex-post inflation uncertainty. Sample standard deviations of the inflation rate expressed as a percentage are used as the proxy for inflation uncertainty, in line with empirical work by different scholars such as Foster [24] ; Çekin and Valcarcel [17] , Barro [10] , as well as Iyke and Ho [38] .

Interest rates

The control variable in the paper is interest rates. The interest rates on 91-day treasury bills are used as the proxy for nominal interest rates in the paper. The treasury bill rate is chosen instead of the official repo rate due to its reasonable variation over time. The treasury bill rates are commonly used as the proxy for the official repo rate, for example, in Boinet and Martin [12] , Naraidoo and Raputsoane [53] and Lee and Werner [46] . Botha [14] also stated that treasury bills serve as a reference rate for the determination of interest rates on other money-market instruments. The inclusion of nominal interest rates is informed by literature from different studies such as Amusa, Gupta, Karolia and Simo-Kengne [3] as well as Bonga-Bonga and Simo-Kengne [13] , which proxied 91-day treasury bills for nominal interest rates as a control variable to investigate inflation and output growth dynamics.

Autoregressive distributed lag bounds testing procedure for co-integration