Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

Published on May 8, 2020 by Lauren Thomas . Revised on June 22, 2023.

In a longitudinal study, researchers repeatedly examine the same individuals to detect any changes that might occur over a period of time.

Longitudinal studies are a type of correlational research in which researchers observe and collect data on a number of variables without trying to influence those variables.

While they are most commonly used in medicine, economics, and epidemiology, longitudinal studies can also be found in the other social or medical sciences.

Table of contents

How long is a longitudinal study, longitudinal vs cross-sectional studies, how to perform a longitudinal study, advantages and disadvantages of longitudinal studies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about longitudinal studies.

No set amount of time is required for a longitudinal study, so long as the participants are repeatedly observed. They can range from as short as a few weeks to as long as several decades. However, they usually last at least a year, oftentimes several.

One of the longest longitudinal studies, the Harvard Study of Adult Development , has been collecting data on the physical and mental health of a group of Boston men for over 80 years!

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

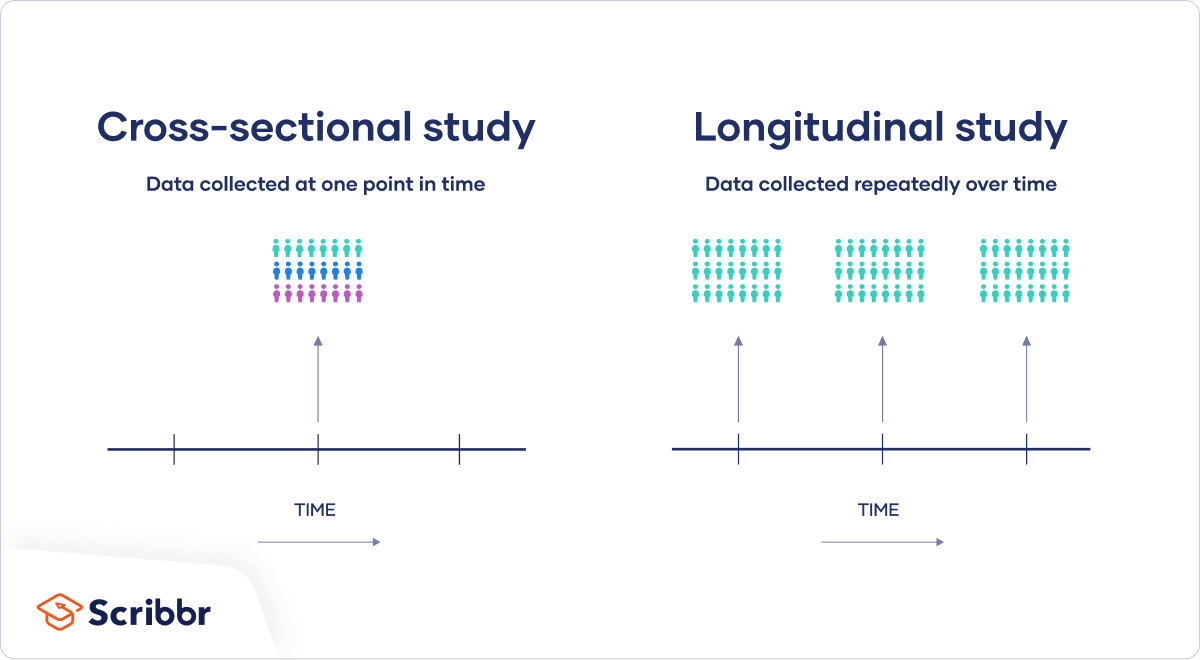

The opposite of a longitudinal study is a cross-sectional study. While longitudinal studies repeatedly observe the same participants over a period of time, cross-sectional studies examine different samples (or a “cross-section”) of the population at one point in time. They can be used to provide a snapshot of a group or society at a specific moment.

Both types of study can prove useful in research. Because cross-sectional studies are shorter and therefore cheaper to carry out, they can be used to discover correlations that can then be investigated in a longitudinal study.

If you want to implement a longitudinal study, you have two choices: collecting your own data or using data already gathered by somebody else.

Using data from other sources

Many governments or research centers carry out longitudinal studies and make the data freely available to the general public. For example, anyone can access data from the 1970 British Cohort Study, which has followed the lives of 17,000 Brits since their births in a single week in 1970, through the UK Data Service website .

These statistics are generally very trustworthy and allow you to investigate changes over a long period of time. However, they are more restrictive than data you collect yourself. To preserve the anonymity of the participants, the data collected is often aggregated so that it can only be analyzed on a regional level. You will also be restricted to whichever variables the original researchers decided to investigate.

If you choose to go this route, you should carefully examine the source of the dataset as well as what data is available to you.

Collecting your own data

If you choose to collect your own data, the way you go about it will be determined by the type of longitudinal study you choose to perform. You can choose to conduct a retrospective or a prospective study.

- In a retrospective study , you collect data on events that have already happened.

- In a prospective study , you choose a group of subjects and follow them over time, collecting data in real time.

Retrospective studies are generally less expensive and take less time than prospective studies, but are more prone to measurement error.

Like any other research design , longitudinal studies have their tradeoffs: they provide a unique set of benefits, but also come with some downsides.

Longitudinal studies allow researchers to follow their subjects in real time. This means you can better establish the real sequence of events, allowing you insight into cause-and-effect relationships.

Longitudinal studies also allow repeated observations of the same individual over time. This means any changes in the outcome variable cannot be attributed to differences between individuals.

Prospective longitudinal studies eliminate the risk of recall bias , or the inability to correctly recall past events.

Disadvantages

Longitudinal studies are time-consuming and often more expensive than other types of studies, so they require significant commitment and resources to be effective.

Since longitudinal studies repeatedly observe subjects over a period of time, any potential insights from the study can take a while to be discovered.

Attrition, which occurs when participants drop out of a study, is common in longitudinal studies and may result in invalid conclusions.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies are two different types of research design . In a cross-sectional study you collect data from a population at a specific point in time; in a longitudinal study you repeatedly collect data from the same sample over an extended period of time.

Longitudinal studies can last anywhere from weeks to decades, although they tend to be at least a year long.

Longitudinal studies are better to establish the correct sequence of events, identify changes over time, and provide insight into cause-and-effect relationships, but they also tend to be more expensive and time-consuming than other types of studies.

The 1970 British Cohort Study , which has collected data on the lives of 17,000 Brits since their births in 1970, is one well-known example of a longitudinal study .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Thomas, L. (2023, June 22). Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/longitudinal-study/

Is this article helpful?

Lauren Thomas

Other students also liked, cross-sectional study | definition, uses & examples, correlational research | when & how to use, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Longitudinal Study Design

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

A longitudinal study is a type of observational and correlational study that involves monitoring a population over an extended period of time. It allows researchers to track changes and developments in the subjects over time.

What is a Longitudinal Study?

In longitudinal studies, researchers do not manipulate any variables or interfere with the environment. Instead, they simply conduct observations on the same group of subjects over a period of time.

These research studies can last as short as a week or as long as multiple years or even decades. Unlike cross-sectional studies that measure a moment in time, longitudinal studies last beyond a single moment, enabling researchers to discover cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

They are beneficial for recognizing any changes, developments, or patterns in the characteristics of a target population. Longitudinal studies are often used in clinical and developmental psychology to study shifts in behaviors, thoughts, emotions, and trends throughout a lifetime.

For example, a longitudinal study could be used to examine the progress and well-being of children at critical age periods from birth to adulthood.

The Harvard Study of Adult Development is one of the longest longitudinal studies to date. Researchers in this study have followed the same men group for over 80 years, observing psychosocial variables and biological processes for healthy aging and well-being in late life (see Harvard Second Generation Study).

When designing longitudinal studies, researchers must consider issues like sample selection and generalizability, attrition and selectivity bias, effects of repeated exposure to measures, selection of appropriate statistical models, and coverage of the necessary timespan to capture the phenomena of interest.

Panel Study

- A panel study is a type of longitudinal study design in which the same set of participants are measured repeatedly over time.

- Data is gathered on the same variables of interest at each time point using consistent methods. This allows studying continuity and changes within individuals over time on the key measured constructs.

- Prominent examples include national panel surveys on topics like health, aging, employment, and economics. Panel studies are a type of prospective study .

Cohort Study

- A cohort study is a type of longitudinal study that samples a group of people sharing a common experience or demographic trait within a defined period, such as year of birth.

- Researchers observe a population based on the shared experience of a specific event, such as birth, geographic location, or historical experience. These studies are typically used among medical researchers.

- Cohorts are identified and selected at a starting point (e.g. birth, starting school, entering a job field) and followed forward in time.

- As they age, data is collected on cohort subgroups to determine their differing trajectories. For example, investigating how health outcomes diverge for groups born in 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

- Cohort studies do not require the same individuals to be assessed over time; they just require representation from the cohort.

Retrospective Study

- In a retrospective study , researchers either collect data on events that have already occurred or use existing data that already exists in databases, medical records, or interviews to gain insights about a population.

- Appropriate when prospectively following participants from the past starting point is infeasible or unethical. For example, studying early origins of diseases emerging later in life.

- Retrospective studies efficiently provide a “snapshot summary” of the past in relation to present status. However, quality concerns with retrospective data make careful interpretation necessary when inferring causality. Memory biases and selective retention influence quality of retrospective data.

Allows researchers to look at changes over time

Because longitudinal studies observe variables over extended periods of time, researchers can use their data to study developmental shifts and understand how certain things change as we age.

High validation

Since objectives and rules for long-term studies are established before data collection, these studies are authentic and have high levels of validity.

Eliminates recall bias

Recall bias occurs when participants do not remember past events accurately or omit details from previous experiences.

Flexibility

The variables in longitudinal studies can change throughout the study. Even if the study was created to study a specific pattern or characteristic, the data collection could show new data points or relationships that are unique and worth investigating further.

Limitations

Costly and time-consuming.

Longitudinal studies can take months or years to complete, rendering them expensive and time-consuming. Because of this, researchers tend to have difficulty recruiting participants, leading to smaller sample sizes.

Large sample size needed

Longitudinal studies tend to be challenging to conduct because large samples are needed for any relationships or patterns to be meaningful. Researchers are unable to generate results if there is not enough data.

Participants tend to drop out

Not only is it a struggle to recruit participants, but subjects also tend to leave or drop out of the study due to various reasons such as illness, relocation, or a lack of motivation to complete the full study.

This tendency is known as selective attrition and can threaten the validity of an experiment. For this reason, researchers using this approach typically recruit many participants, expecting a substantial number to drop out before the end.

Report bias is possible

Longitudinal studies will sometimes rely on surveys and questionnaires, which could result in inaccurate reporting as there is no way to verify the information presented.

- Data were collected for each child at three-time points: at 11 months after adoption, at 4.5 years of age and at 10.5 years of age. The first two sets of results showed that the adoptees were behind the non-institutionalised group however by 10.5 years old there was no difference between the two groups. The Romanian orphans had caught up with the children raised in normal Canadian families.

- The role of positive psychology constructs in predicting mental health and academic achievement in children and adolescents (Marques Pais-Ribeiro, & Lopez, 2011)

- The correlation between dieting behavior and the development of bulimia nervosa (Stice et al., 1998)

- The stress of educational bottlenecks negatively impacting students’ wellbeing (Cruwys, Greenaway, & Haslam, 2015)

- The effects of job insecurity on psychological health and withdrawal (Sidney & Schaufeli, 1995)

- The relationship between loneliness, health, and mortality in adults aged 50 years and over (Luo et al., 2012)

- The influence of parental attachment and parental control on early onset of alcohol consumption in adolescence (Van der Vorst et al., 2006)

- The relationship between religion and health outcomes in medical rehabilitation patients (Fitchett et al., 1999)

Goals of Longitudinal Data and Longitudinal Research

The objectives of longitudinal data collection and research as outlined by Baltes and Nesselroade (1979):

- Identify intraindividual change : Examine changes at the individual level over time, including long-term trends or short-term fluctuations. Requires multiple measurements and individual-level analysis.

- Identify interindividual differences in intraindividual change : Evaluate whether changes vary across individuals and relate that to other variables. Requires repeated measures for multiple individuals plus relevant covariates.

- Analyze interrelationships in change : Study how two or more processes unfold and influence each other over time. Requires longitudinal data on multiple variables and appropriate statistical models.

- Analyze causes of intraindividual change: This objective refers to identifying factors or mechanisms that explain changes within individuals over time. For example, a researcher might want to understand what drives a person’s mood fluctuations over days or weeks. Or what leads to systematic gains or losses in one’s cognitive abilities across the lifespan.

- Analyze causes of interindividual differences in intraindividual change : Identify mechanisms that explain within-person changes and differences in changes across people. Requires repeated data on outcomes and covariates for multiple individuals plus dynamic statistical models.

How to Perform a Longitudinal Study

When beginning to develop your longitudinal study, you must first decide if you want to collect your own data or use data that has already been gathered.

Using already collected data will save you time, but it will be more restricted and limited than collecting it yourself. When collecting your own data, you can choose to conduct either a retrospective or prospective study .

In a retrospective study, you are collecting data on events that have already occurred. You can examine historical information, such as medical records, in order to understand the past. In a prospective study, on the other hand, you are collecting data in real-time. Prospective studies are more common for psychology research.

Once you determine the type of longitudinal study you will conduct, you then must determine how, when, where, and on whom the data will be collected.

A standardized study design is vital for efficiently measuring a population. Once a study design is created, researchers must maintain the same study procedures over time to uphold the validity of the observation.

A schedule should be maintained, complete results should be recorded with each observation, and observer variability should be minimized.

Researchers must observe each subject under the same conditions to compare them. In this type of study design, each subject is the control.

Methodological Considerations

Important methodological considerations include testing measurement invariance of constructs across time, appropriately handling missing data, and using accelerated longitudinal designs that sample different age cohorts over overlapping time periods.

Testing measurement invariance

Testing measurement invariance involves evaluating whether the same construct is being measured in a consistent, comparable way across multiple time points in longitudinal research.

This includes assessing configural, metric, and scalar invariance through confirmatory factor analytic approaches. Ensuring invariance gives more confidence when drawing inferences about change over time.

Missing data

Missing data can occur during initial sampling if certain groups are underrepresented or fail to respond.

Attrition over time is the main source – participants dropping out for various reasons. The consequences of missing data are reduced statistical power and potential bias if dropout is nonrandom.

Handling missing data appropriately in longitudinal studies is critical to reducing bias and maintaining power.

It is important to minimize attrition by tracking participants, keeping contact info up to date, engaging them, and providing incentives over time.

Techniques like maximum likelihood estimation and multiple imputation are better alternatives to older methods like listwise deletion. Assumptions about missing data mechanisms (e.g., missing at random) shape the analytic approaches taken.

Accelerated longitudinal designs

Accelerated longitudinal designs purposefully create missing data across age groups.

Accelerated longitudinal designs strategically sample different age cohorts at overlapping periods. For example, assessing 6th, 7th, and 8th graders at yearly intervals would cover 6-8th grade development over a 3-year study rather than following a single cohort over that timespan.

This increases the speed and cost-efficiency of longitudinal data collection and enables the examination of age/cohort effects. Appropriate multilevel statistical models are required to analyze the resulting complex data structure.

In addition to those considerations, optimizing the time lags between measurements, maximizing participant retention, and thoughtfully selecting analysis models that align with the research questions and hypotheses are also vital in ensuring robust longitudinal research.

So, careful methodology is key throughout the design and analysis process when working with repeated-measures data.

Cohort effects

A cohort refers to a group born in the same year or time period. Cohort effects occur when different cohorts show differing trajectories over time.

Cohort effects can bias results if not accounted for, especially in accelerated longitudinal designs which assume cohort equivalence.

Detecting cohort effects is important but can be challenging as they are confounded with age and time of measurement effects.

Cohort effects can also interfere with estimating other effects like retest effects. This happens because comparing groups to estimate retest effects relies on cohort equivalence.

Overall, researchers need to test for and control cohort effects which could otherwise lead to invalid conclusions. Careful study design and analysis is required.

Retest effects

Retest effects refer to gains in performance that occur when the same or similar test is administered on multiple occasions.

For example, familiarity with test items and procedures may allow participants to improve their scores over repeated testing above and beyond any true change.

Specific examples include:

- Memory tests – Learning which items tend to be tested can artificially boost performance over time

- Cognitive tests – Becoming familiar with the testing format and particular test demands can inflate scores

- Survey measures – Remembering previous responses can bias future responses over multiple administrations

- Interviews – Comfort with the interviewer and process can lead to increased openness or recall

To estimate retest effects, performance of retested groups is compared to groups taking the test for the first time. Any divergence suggests inflated scores due to retesting rather than true change.

If unchecked in analysis, retest gains can be confused with genuine intraindividual change or interindividual differences.

This undermines the validity of longitudinal findings. Thus, testing and controlling for retest effects are important considerations in longitudinal research.

Data Analysis

Longitudinal data involves repeated assessments of variables over time, allowing researchers to study stability and change. A variety of statistical models can be used to analyze longitudinal data, including latent growth curve models, multilevel models, latent state-trait models, and more.

Latent growth curve models allow researchers to model intraindividual change over time. For example, one could estimate parameters related to individuals’ baseline levels on some measure, linear or nonlinear trajectory of change over time, and variability around those growth parameters. These models require multiple waves of longitudinal data to estimate.

Multilevel models are useful for hierarchically structured longitudinal data, with lower-level observations (e.g., repeated measures) nested within higher-level units (e.g., individuals). They can model variability both within and between individuals over time.

Latent state-trait models decompose the covariance between longitudinal measurements into time-invariant trait factors, time-specific state residuals, and error variance. This allows separating stable between-person differences from within-person fluctuations.

There are many other techniques like latent transition analysis, event history analysis, and time series models that have specialized uses for particular research questions with longitudinal data. The choice of model depends on the hypotheses, timescale of measurements, age range covered, and other factors.

In general, these various statistical models allow investigation of important questions about developmental processes, change and stability over time, causal sequencing, and both between- and within-person sources of variability. However, researchers must carefully consider the assumptions behind the models they choose.

Longitudinal vs. Cross-Sectional Studies

Longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies are two different observational study designs where researchers analyze a target population without manipulating or altering the natural environment in which the participants exist.

Yet, there are apparent differences between these two forms of study. One key difference is that longitudinal studies follow the same sample of people over an extended period of time, while cross-sectional studies look at the characteristics of different populations at a given moment in time.

Longitudinal studies tend to require more time and resources, but they can be used to detect cause-and-effect relationships and establish patterns among subjects.

On the other hand, cross-sectional studies tend to be cheaper and quicker but can only provide a snapshot of a point in time and thus cannot identify cause-and-effect relationships.

Both studies are valuable for psychologists to observe a given group of subjects. Still, cross-sectional studies are more beneficial for establishing associations between variables, while longitudinal studies are necessary for examining a sequence of events.

1. Are longitudinal studies qualitative or quantitative?

Longitudinal studies are typically quantitative. They collect numerical data from the same subjects to track changes and identify trends or patterns.

However, they can also include qualitative elements, such as interviews or observations, to provide a more in-depth understanding of the studied phenomena.

2. What’s the difference between a longitudinal and case-control study?

Case-control studies compare groups retrospectively and cannot be used to calculate relative risk. Longitudinal studies, though, can compare groups either retrospectively or prospectively.

In case-control studies, researchers study one group of people who have developed a particular condition and compare them to a sample without the disease.

Case-control studies look at a single subject or a single case, whereas longitudinal studies are conducted on a large group of subjects.

3. Does a longitudinal study have a control group?

Yes, a longitudinal study can have a control group . In such a design, one group (the experimental group) would receive treatment or intervention, while the other group (the control group) would not.

Both groups would then be observed over time to see if there are differences in outcomes, which could suggest an effect of the treatment or intervention.

However, not all longitudinal studies have a control group, especially observational ones and not testing a specific intervention.

Baltes, P. B., & Nesselroade, J. R. (1979). History and rationale of longitudinal research. In J. R. Nesselroade & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), (pp. 1–39). Academic Press.

Cook, N. R., & Ware, J. H. (1983). Design and analysis methods for longitudinal research. Annual review of public health , 4, 1–23.

Fitchett, G., Rybarczyk, B., Demarco, G., & Nicholas, J.J. (1999). The role of religion in medical rehabilitation outcomes: A longitudinal study. Rehabilitation Psychology, 44, 333-353.

Harvard Second Generation Study. (n.d.). Harvard Second Generation Grant and Glueck Study. Harvard Study of Adult Development. Retrieved from https://www.adultdevelopmentstudy.org.

Le Mare, L., & Audet, K. (2006). A longitudinal study of the physical growth and health of postinstitutionalized Romanian adoptees. Pediatrics & child health, 11 (2), 85-91.

Luo, Y., Hawkley, L. C., Waite, L. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: a national longitudinal study. Social science & medicine (1982), 74 (6), 907–914.

Marques, S. C., Pais-Ribeiro, J. L., & Lopez, S. J. (2011). The role of positive psychology constructs in predicting mental health and academic achievement in children and adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 12( 6), 1049–1062.

Sidney W.A. Dekker & Wilmar B. Schaufeli (1995) The effects of job insecurity on psychological health and withdrawal: A longitudinal study, Australian Psychologist, 30: 1,57-63.

Stice, E., Mazotti, L., Krebs, M., & Martin, S. (1998). Predictors of adolescent dieting behaviors: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 12 (3), 195–205.

Tegan Cruwys, Katharine H Greenaway & S Alexander Haslam (2015) The Stress of Passing Through an Educational Bottleneck: A Longitudinal Study of Psychology Honours Students, Australian Psychologist, 50:5, 372-381.

Thomas, L. (2020). What is a longitudinal study? Scribbr. Retrieved from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/longitudinal-study/

Van der Vorst, H., Engels, R. C. M. E., Meeus, W., & Deković, M. (2006). Parental attachment, parental control, and early development of alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20 (2), 107–116.

Further Information

- Schaie, K. W. (2005). What can we learn from longitudinal studies of adult development?. Research in human development, 2 (3), 133-158.

- Caruana, E. J., Roman, M., Hernández-Sánchez, J., & Solli, P. (2015). Longitudinal studies. Journal of thoracic disease, 7 (11), E537.

- Open access

- Published: 01 October 2022

Qualitative longitudinal research in health research: a method study

- Åsa Audulv 1 ,

- Elisabeth O. C. Hall 2 , 3 ,

- Åsa Kneck 4 ,

- Thomas Westergren 5 , 6 ,

- Liv Fegran 5 ,

- Mona Kyndi Pedersen 7 , 8 ,

- Hanne Aagaard 9 ,

- Kristianna Lund Dam 3 &

- Mette Spliid Ludvigsen 10 , 11

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 22 , Article number: 255 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

17 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Qualitative longitudinal research (QLR) comprises qualitative studies, with repeated data collection, that focus on the temporality (e.g., time and change) of a phenomenon. The use of QLR is increasing in health research since many topics within health involve change (e.g., progressive illness, rehabilitation). A method study can provide an insightful understanding of the use, trends and variations within this approach. The aim of this study was to map how QLR articles within the existing health research literature are designed to capture aspects of time and/or change.

This method study used an adapted scoping review design. Articles were eligible if they were written in English, published between 2017 and 2019, and reported results from qualitative data collected at different time points/time waves with the same sample or in the same setting. Articles were identified using EBSCOhost. Two independent reviewers performed the screening, selection and charting.

A total of 299 articles were included. There was great variation among the articles in the use of methodological traditions, type of data, length of data collection, and components of longitudinal data collection. However, the majority of articles represented large studies and were based on individual interview data. Approximately half of the articles self-identified as QLR studies or as following a QLR design, although slightly less than 20% of them included QLR method literature in their method sections.

Conclusions

QLR is often used in large complex studies. Some articles were thoroughly designed to capture time/change throughout the methodology, aim and data collection, while other articles included few elements of QLR. Longitudinal data collection includes several components, such as what entities are followed across time, the tempo of data collection, and to what extent the data collection is preplanned or adapted across time. Therefore, there are several practices and possibilities researchers should consider before starting a QLR project.

Peer Review reports

Health research is focused on areas and topics where time and change are relevant. For example, processes such as recovery or changes in health status. However, relating time and change can be complicated in research, as the representation of reality in research publications is often collected at one point in time and fixed in its presentation, although time and change are always present in human life and experiences. Qualitative longitudinal research (QLR; also called longitudinal qualitative research, LQR) has been developed to focus on subjective experiences of time or change using qualitative data materials (e.g., interviews, observations and/or text documents) collected across a time span with the same participants and/or in the same setting [ 1 , 2 ]. QLR within health research may have many benefits. Firstly, human experiences are not fixed and consistent, but changing and diverse, therefore people’s experiences in relation to a health phenomenon may be more comprehensively described by repeated interviews or observations over time. Secondly, experiences, behaviors, and social norms unfold over time. By using QLR, researchers can collect empirical data that represents not only recalled human conceptions but also serial and instant situations reflecting transitions, trajectories and changes in people’s health experiences, personal development or health care organizations [ 3 , 4 , 5 ].

Key features of QLR

Whether QLR is a methodological approach in its own right or a design element of a particular study within a traditional methodological approach (e.g., ethnography or grounded theory) is debated [ 1 , 6 ]. For example, Bennett et al. [ 7 ] describe QLR as untied to methodology, giving researchers the flexibility to develop a suitable design for each study. McCoy [ 6 ] suggests that epistemological and ontological standpoints from interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) align with QLR traditions, thus making longitudinal IPA a suitable methodology. Plano-Clark et al. [ 8 ] described how longitudinal qualitative elements can be used in mixed methods studies, thus creating longitudinal mixed methods. In contrast, several researchers have argued that QLR is an emerging methodology [ 1 , 5 , 9 , 10 ]. For example, Thomson et al. [ 9 ] have stated “What distinguishes longitudinal qualitative research is the deliberate way in which temporality is designed into the research process, making change a central focus of analytic attention” (p. 185). Tuthill et al. [ 5 ] concluded that some of the confusion might have arisen from the diversity of data collection methods and data materials used within QLR research. However, there are no investigations showing to what extent QLR studies use QLR as a distinct methodology versus using a longitudinal data collection as a more flexible design element in combination with other qualitative methodologies.

QLR research should focus on aspects of temporality, time and/or change [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. The concepts of time and change are seen as inseparable since change is happening with the passing of time [ 13 ]. However, time can be conceptualized in different ways. Time is often understood from a chronological perspective, and is viewed as fixed, objective, continuous and measurable (e.g., clock time, duration of time). However, time can also be understood from within, as the experience of the passing of time and/or the perspective from the current moment into the constructed conception of a history or future. From this perspective, time is seen as fluid, meaning that events, contexts and understandings create a subjective experience of time and change. Both the chronological and fluid understanding of time influence QLR research [ 11 ]. Furthermore, there is a distinction between over-time, which constitutes a comparison of the difference between points in time, often with a focus on the latter point or destination, and through-time, which means following an aspect across time while trying to understand the change that occurs [ 11 ]. In this article, we will mostly use the concept of across time to include both perspectives.

Some authors assert that QLR studies should include a qualitative data collection with the same sample across time [ 11 , 13 ], whereas Thomson et al. [ 9 ] also suggest the possibility of returning to the same data collection site with the same or different participants. When a QLR study involves data collection in shorter engagements, such as serial interviews, these engagements are often referred to as data collection time points. Data collection in time waves relates to longer engagements, such as field work/observation periods. There is no clear-cut definition for the minimum time span of a QLR study; instead, the length of the data collection period must be decided based upon what processes or changes are the focus of the study [ 13 ].

Most literature describing QLR methods originates from the social sciences, where the approach has a long tradition [ 1 , 10 , 14 ]. In health research, one-time-data collection studies have been the norm within qualitative methods [ 15 ], although health research using QLR methods has increased in recent years [ 2 , 5 , 16 , 17 ]. However, collecting and managing longitudinal data has its own sets of challenges, especially regarding how to integrate perspectives of time and/or change in the data collection and subsequent analysis [ 1 ]. Therefore, a study of QLR articles from the health research literature can provide an insightful understanding of the use, trends and variations of how methods are used and how elements of time/change are integrated in QLR studies. This could, in turn, provide inspiration for using different possibilities of collecting data across time when using QLR in health research. The aim of this study was to map how QLR articles within the existing health research literature are designed to capture aspects of time and/or change.

More specifically, the research questions were:

What methodological approaches are described to inform QLR research?

What methodological references are used to inform QLR research?

How are longitudinal perspectives articulated in article aims?

How is longitudinal data collection conducted?

In this method study, we used an adapted scoping review method [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Method studies are research conducted on research studies to investigate how research design elements are applied across a field [ 21 ]. However, since there are no clear guidelines for method studies, they often use adapted versions of systematic reviews or scoping review methods [ 21 ]. The adaptations of the scoping review method consisted of 1) using a large subsample of studies (publications from a three-year period) instead of including all QLR articles published, and 2) not including grey literature. The reporting of this study was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [ 20 , 22 ] (see Additional file 1 ). A (unpublished) protocol was developed by the research team during the spring of 2019.

Eligibility criteria

In line with method study recommendations [ 21 ], we decided to draw on a manageable subsample of published QLR research. Articles that were eligible for inclusion were health research primary studies written in English, published between 2017 and 2019, and with a longitudinal qualitative data collection. Our operating definition for qualitative longitudinal data collection was data collected at different time points (e.g., repeated interviews) or time waves (e.g., periods of field work) involving the same sample or conducted in the same setting(s). We intentionally selected a broad inclusion criterion for QLR since we wanted a wide variety of articles. The selected time period was chosen because the first QLR method article directed towards health research was published in 2013 [ 1 ] and during the following years the methodological resources for QLR increased [ 3 , 8 , 17 , 23 , 24 , 25 ], thus we could expect that researchers publishing QLR in 2017–2019 should be well-grounded in QLR methods. Further, we found that from 2012 to 2019 the rate of published QLR articles were steady at around 100 publications per year, so including those from a three-year period would give a sufficient number of articles (~ 300 articles) for providing an overview of the field. Published conference abstracts, protocols, articles describing methodological issues, review articles, and non-research articles (e.g., editorials) were excluded.

Search strategy

Relevant articles were identified through systematic searches in EBSCOhost, including biomedical and life science research and nursing and allied health literature. A librarian who specialized in systematic review searches developed and performed the searches, in collaboration with the author team (LF, TW & ÅA). In the search, the term “longitudinal” was combined with terms for qualitative research (for the search strategy see Additional file 2 ). The searches were conducted in the autumn of 2019 (last search 2019-09-10).

Study selection

All identified citations were imported into EndNote X9 ( www.endnote.com ) and further imported into Rayyan QCRI online software [ 26 ], and duplicates were removed. All titles and abstracts were screened against the eligibility criteria by two independent reviewers (ÅA & EH), and conflicting decisions were discussed until resolved. After discussions by the team, we decided to include articles published between 2017 and 2019, that selection alone included 350 records with diverse methods and designs. The full texts of articles that were eligible for inclusion were retrieved. In the next stage, two independent reviewers reviewed each full text article to make final decisions regarding inclusion (ÅA, EH, Julia Andersson). In total, disagreements occurred in 8% of the decisions, and were resolved through discussion. Critical appraisal was not assessed since the study aimed to describe the range of how QLR is applied and not aggregate research findings [ 21 , 22 ].

Data charting and analysis

A standardized charting form was developed in Excel (Excel 2016). The charting form was reviewed by the research team and pretested in two stages. The tests were performed to increase internal consistency and reduce the risk of bias. First, four articles were reviewed by all the reviewers, and modifications were made to the form and charting instructions. In the next stage, all reviewers used the charting form on four other articles, and the convergence in ratings was 88%. Since the convergence was under 90%, charting was performed in duplicate to reduce errors in the data. At the end of the charting process, the convergence among the reviewers was 95%. The charting was examined by the first author, who revised the charting in cases of differences.

Data items that were charted included 1) the article characteristics (e.g., authors, publication year, journal, country), 2) the aim and scope (e.g., phenomenon of interest, population, contexts), 3) the stated methodology and analysis method, 4) text describing the data collection (e.g., type of data material, number of participants, time frame of data collection, total amount of data material), and 5) the qualitative methodological references used in the methods section. Extracted text describing data collection could consist of a few sentences or several sections from the articles (and sometimes figures) concerning data collection practices, rational for time periods and research engagement in the field. This was later used to analyze how the longitudinal data collection was conducted and elements of longitudinal design. To categorize the qualitative methodology approaches, a framework from Cresswell [ 27 ] was used (including the categories for grounded theory, phenomenology, ethnography, case study and narrative research). Overall, data items needed to be explicitly stated in the articles in order to be charted. For example, an article was categorized as grounded theory if it explicitly stated “in this grounded theory study” but not if it referred to the literature by Glaser and Strauss without situating itself as a grounded theory study (See Additional file 3 for the full instructions for charting).

All charting forms were compiled into a single Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (see Supplementary files for an overview of the articles). Descriptive statistics with frequencies and percentages were calculated to summarize the data. Furthermore, an iterative coding process was used to group the articles and investigate patterns of, for example, research topics, words in the aims, or data collection practices. Alternative ways of grouping and presenting the data were discussed by the research team.

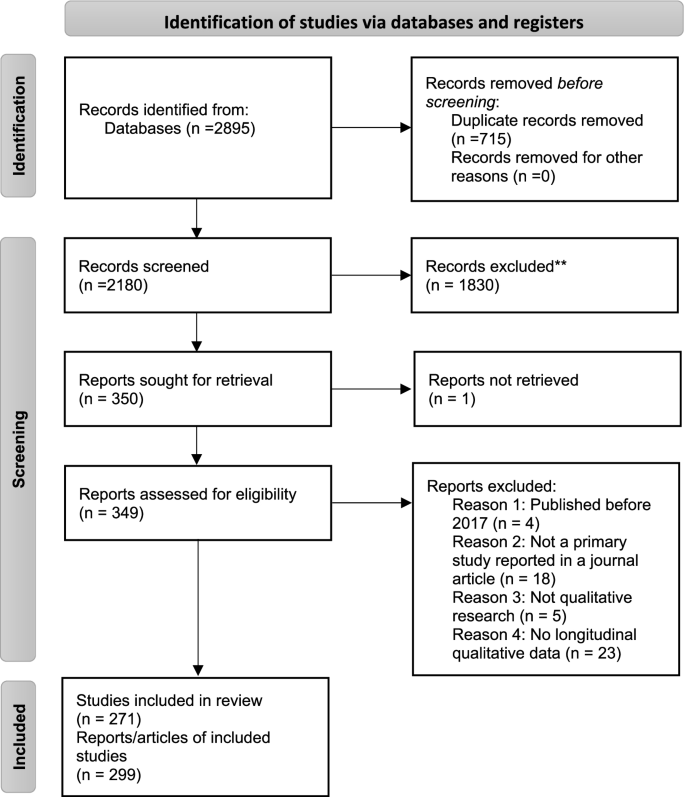

Search and selection

A total of 2179 titles and abstracts were screened against the eligibility criteria (see Fig. 1 ). The full text of one article could not be found and the article was excluded [ 28 ]. Fifty full text articles were excluded. Finally, 299 articles, representing 271 individual studies, were included in this study (see additional files 4 and 5 respectively for tables of excluded and included articles).

PRISMA diagram of study selection]

General characteristics and research areas of the included articles

The articles were published in many journals ( n = 193), and 138 of these journals were represented with one article each. BMJ Open was the most prevalent journal ( n = 11), followed by the Journal of Clinical Nursing ( n = 8). Similarly, the articles represented many countries ( n = 41) and all the continents; however, a large part of the studies originated from the US or UK ( n = 71, 23.7% and n = 70, 23.4%, respectively). The articles focused on the following types of populations: patients, families−/caregivers, health care providers, students, community members, or policy makers. Approximately 20% ( n = 63, 21.1%) of the articles collected data from two or more of these types of population(s) (see Table 1 ).

Approximately half of the articles ( n = 158, 52.8%) articulated being part of a larger research project. Of them, 95 described a project with both quantitative and qualitative methods. They represented either 1) a qualitative study embedded in an intervention, evaluation or implementation study ( n = 66, 22.1%), 2) a longitudinal cohort study collecting both quantitative and qualitative material ( n = 23, 7.7%), or 3) qualitative longitudinal material collected together with a cross sectional survey (n = 6, 2.0%). Forty-eight articles (16.1%) described belonging to a larger qualitative project presented in several research articles.

Methodological traditions

Approximately one-third ( n = 109, 36.5%) of the included articles self-identified with one of the qualitative traditions recognized by Cresswell [ 27 ] (case study: n = 36, 12.0%; phenomenology: n = 35, 11.7%; grounded theory: n = 22, 7.4%; ethnography: n = 13, 4.3%; narrative method: n = 3, 1.0%). In nine articles, the authors described using a mix of two or more of these qualitative traditions. In addition, 19 articles (6.4%) self-identified as mixed methods research.

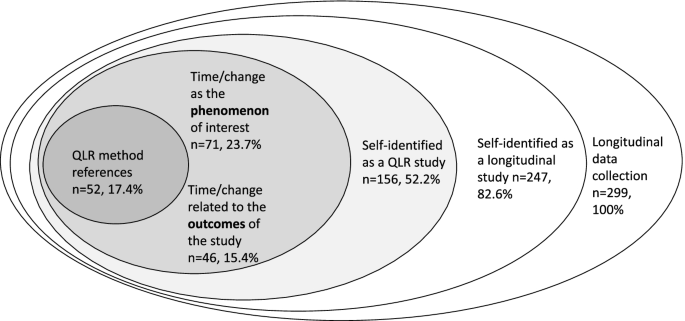

Every second article self-identified as having a qualitative longitudinal design ( n = 156, 52.2%); either they self-identified as “a longitudinal qualitative study” or “using a longitudinal qualitative research design”. However, in some articles, this was stated in the title and/or abstract and nowhere else in the article. Fifty-two articles (17.4%) self-identified both as having a QLR design and following one of the methodological approaches (case study: n = 8; phenomenology: n = 23; grounded theory: n = 9; ethnography: n = 6; narrative method: n = 2; mixed methods: n = 4).

The other 143 articles used various terms to situate themselves in relation to a longitudinal design. Twenty-seven articles described themselves as a longitudinal study (9.0%) or a longitudinal study within a specific qualitative tradition (e.g., a longitudinal grounded theory study or a longitudinal mixed method study) ( n = 64, 21.4%). Furthermore, 36 articles (12.0%) referred to using longitudinal data materials (e.g., longitudinal data or longitudinal interviews). Nine of the articles (3.0%) used the term longitudinal in relation to the data analysis or aim (e.g., the aim was to longitudinally describe), used terms such as serial or repeated in relation to the data collection design ( n = 2, 0.7%), or did not use any term to address the longitudinal nature of their design ( n = 5, 1.7%).

Use of methodological references

The mean number of qualitative method references in the methods sections was 3.7 (range 0 to 16), and 20 articles did not have any qualitative method reference in their methods sections. Footnote 1 Commonly used method references were generic books on qualitative methods, seminal works within qualitative traditions, and references specializing in qualitative analysis methods (see Table 2 ). It should be noted that some references were comprehensive books and thus could include sections about QLR without being focused on the QLR method. For example, Miles et al. [ 31 ] is all about analysis and coding and includes a chapter regarding analyzing change.

Only approximately 20% ( n = 58) of the articles referred to the QLR method literature in their methods sections. Footnote 2 The mean number of QLR method references (counted for articles using such sources) was 1.7 (range 1 to 6). Most articles using the QLR method literature also used other qualitative methods literature (except two articles using one QLR literature reference each [ 39 , 40 ]). In total, 37 QLR method references were used, and 24 of the QLR method references were only referred to by one article each.

Longitudinal perspectives in article aims

In total, 231 (77.3%) articles had one or several terms related to time or change in their aims, whereas 68 articles (22.7%) had none. Over one hundred different words related to time or change were identified. Longitudinally oriented terms could focus on changes across time (process, trajectory, transition, pathway or journey), patterns of how something changed (maintenance, continuity, stability, shifts), or phenomena that by nature included change (learning or implementation). Other types of terms emphasized the data collection time period (e.g., over 6 months) or a specific changing situation (e.g., during pregnancy, through the intervention period, or moving into a nursing home). The most common terms used for the longitudinal perspective were change ( n = 63), over time ( n = 52), process ( n = 36), transition ( n = 24), implementation ( n = 14), development ( n = 13), and longitudinal (n = 13). Footnote 3

Furthermore, the articles varied in what ways their aims focused on time/change, e.g., the longitudinal perspectives in the aims (see Table 3 ). In 71 articles, the change across time was the phenomenon of interest of the article : for example, articles investigating the process of learning or trajectories of diseases. In contrast, 46 articles investigated change or factors impacting change in relation to a defined outcome : for example, articles investigating factors influencing participants continuing in a physical activity trial. The longitudinal perspective could also be embedded in an article’s context . In such cases, the focus of the article was on experiences that happened during a certain time frame or in a time-related context (e.g., described experiences of the patient-provider relationship during 6 months of rehabilitation).

Types of data and length of data collection

The QLR articles were often large and complex in their data collection methods. The median number of participants was 20 (range from one to 1366, the latter being an article with open-ended questions in questionnaires [ 46 ]). Most articles used individual interviews as the data material ( n = 167, 55.9%) or a combination of data materials ( n = 98, 32.8%) (e.g., interviews and observations, individual interviews and focus group interviews, or interviews and questionnaires). Forty-five articles (15.1%) presented quantitative and qualitative results. The median number of interviews was 46 (range three to 507), which is large in comparison to many qualitative studies. The observation materials were also comprehensive and could include several hundred hours of observations. Documents were often used as complementary material and included official documents, newspaper articles, diaries, and/or patient records.

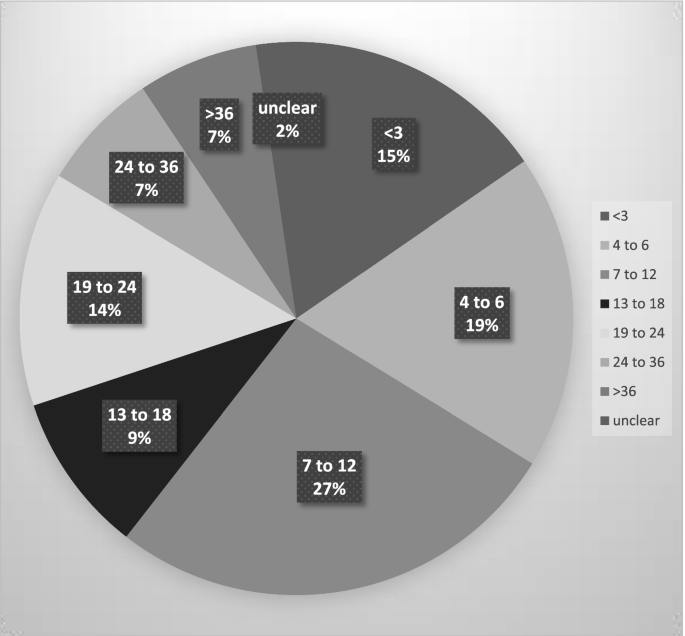

The articles’ time spans Footnote 4 for data collection varied between a few days and over 20 years, with 60% of the articles’ time spans being 1 year or shorter ( n = 180) (see Fig. 2 ). The variation in time spans might be explained by the different kinds of phenomena that were investigated. For example, Jensen et al. [ 47 ] investigated hospital care delivery and followed each participant, with observations lasting between four and 14 days. Smithbattle [ 48 ] described the housing trajectories of teen mothers, and collected data in seven waves over 28 years.

Number of articles in relation to the time span of data collection. The time span of data collection is given in months

Three components of longitudinal data collection

In the articles, the data collection was conducted in relation to three different longitudinal data collection components (see Table 4 ).

Entities followed across time

Four different types of entities were followed across time: 1) individuals, 2) individual cases or dyads, 3) groups, and 4) settings. Every second article ( n = 170, 56.9%) followed individuals across time, thus following the same participants through the whole data collection period. In contrast, when individual cases were followed across time, the data collection was centered on the primary participants (e.g., people with progressive neurological conditions) who were followed over time, and secondary participants (e.g., family caregivers) might provide complementary data at several time points or only at one-time point. When settings were followed over time, the participating individuals were sometimes the same, and sometimes changed across the data collection period. Typical settings were hospital wards, hospitals, smaller communities or intervention trials. The type of collected data corresponded with what kind of entities were followed longitudinally. Individuals were often followed with serial interviews, whereas groups were commonly followed with focus group interviews complemented with individual interviews, observations and/or questionnaires. Overall, the lengths of data collection periods seemed to be chosen based upon expected changes in the chosen entities. For example, the articles following an intervention setting were structured around the intervention timeline, collecting data before, after and sometimes during the intervention.

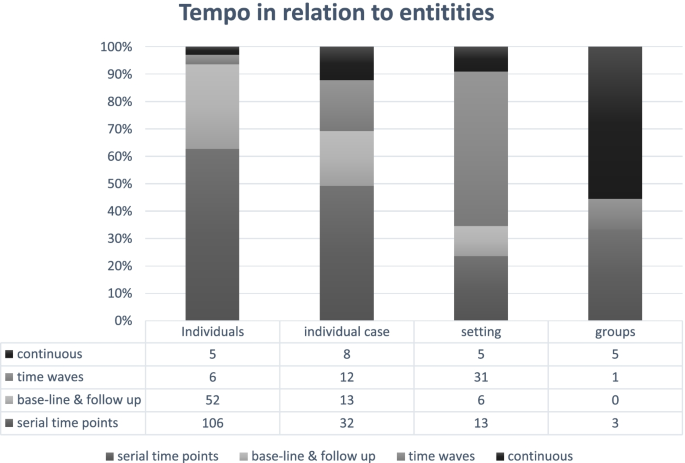

Tempo of data collection

The data collection tempo differed among the articles (e.g., the frequency and mode of the data collection). Approximately half ( n = 154, 51.5%) of the articles used serial time points, collecting data at several reoccurring but shorter sequences (e.g., through serial interviews or open-ended questions in questionnaires). When data were collected in time waves ( n = 50, 16.7%), the periods of data collection were longer, usually including both interviews and observations; often, time waves included observations of a setting and/or interviews at the same location over several days or weeks.

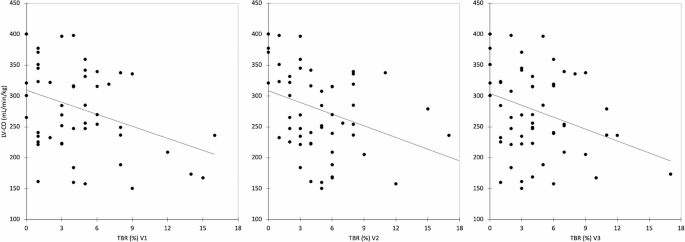

When comparing the tempo with the type of entities, some patterns were detected (see Fig. 3 ). When individuals were followed, data were often collected at time points, mirroring the use of individual interviews and/or short observations. For research in settings, data were commonly collected in time waves (e.g., observation periods over a few weeks or months). In studies exploring settings across time, time waves were commonly used and combined several types of data, particularly from interviews and observations. Groups were the least common studied entity ( n = 9, 3.0%), so the numbers should be interpreted with caution, but continuous data collection was used in five of the nine studies. The continuous data collection mode was, for example, collecting electronic diaries [ 62 ] or minutes from committee meetings during a time period [ 63 ].

Tempo of data collection in relation to entities followed over time

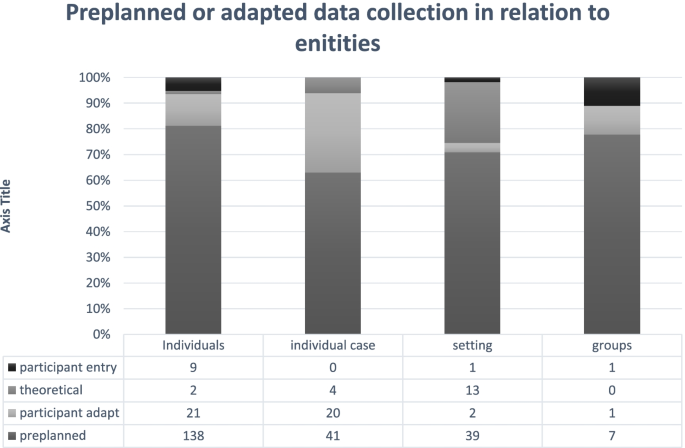

Preplanned or adapted data collection

A large majority ( n = 224, 74.9%) of the articles used preplanned data collection (e.g., in preplanned data collection, all participants were followed across time according to the same data collection plan). For example, all participants were interviewed one, six and twelve months’ post-diagnosis. In contrast to the preplanned data collection approach, 44 articles had a participant-adapted data collection (14.7%), and participants were followed at different frequencies and/or over various lengths of time depending on each participant’s situation. Participant-adapted data collection was more common among articles following individuals or individual cases (see Fig. 4 ). To adapt the data collection to the participants, the researchers created strategies to reach participants when crucial events were happening. Eleven articles used a participant entry approach to data collection ( n = 11, 6.7%), and the whole or parts of the data were independently sent in by participants in the form of diaries, questionnaires, or blogs. Another approach to data collection was using theoretical or analysis-driven ideas to guide the data collection ( n = 19, 6.4%). In these articles, the analysis and data collection were conducted simultaneously, and ideas arising in the analysis could be followed up, for example, returning to some participants, recruiting participants with specific experiences, or collecting complementary types of data materials. This approach was most common in the articles following settings across time, which often included observations and interviews with different types of populations. Articles using theoretical or analysis driven data collection were not associated with grounded theory to a greater extent than the other articles in the sample (e.g., did not self-identify as grounded theory or referred to methodological literature within grounded theory traditions to a greater proportion).

Preplanned or adapted data collection in relation to entities followed over time

According to our results, some researchers used QLR as a methodological approach and other researchers used a longitudinal qualitative data collection without aiming to investigate change. Adding to the debate on whether QLR is a methodological approach in its own right or a design element in a particular study we suggest that the use of QLR can be described as layered (see Fig. 5 ). Namely, articles must fulfill several criteria in order to use QLR as a methodological approach, and that is done in some articles. In those articles QLR method references were used, the aim was to investigate change of a phenomenon and the longitudinal elements of the data collection were thoroughly integrated into the method section. On the other hand, some articles using a longitudinal qualitative data collection were just collecting data over time, without addressing time and/or change in the aim. These articles can still be interesting research studies with valuable results, but they are not using the full potential of QLR as a methodological approach. In all, around 40% of the articles had an aim that focused on describing or understanding change (either as phenomenon or outcome); but only about 24% of the articles set out to investigate change across time as their phenomenon of interest.

The QLR onion. The use of QLR design can be described as layered, where researchers use more or less elements of a QLR design. The two inmost layers represents articles using QLR as a methodological approach

Regarding methodological influences, about one-third of the articles self-identify with any of the traditional qualitative methodologies. Using a longitudinal qualitative data collection as an element integrated with another methodological tradition can therefore be seen as one way of working with longitudinal qualitative materials. In our results, the articles referring to methodologies other than QLR preferably used case study, phenomenology and grounded theory methodologies. This was surprising since Neale [ 10 ] identified ethnography, case studies and narrative methods as the main methodological influences on QLR. Our findings might mirror the profound impacts that phenomenology and grounded theory have had on the qualitative field of health research. Regarding phenomenology, the findings can also be influenced by more recent discussions of combining interpretative phenomenological analysis with QLR [ 6 ].

Half of the articles self-identified as QLR studies, but QLR method references were used in less than 20% of the identified articles. This is both surprising and troublesome since use of appropriate method literature might have supported researchers who were struggling with for example a large quantity of materials and complex analysis. A possible explanation for the lack of use of QLR method literature is that QLR as a methodological approach is not well known, and authors might not be aware that method literature exists. It is quite understandable that researchers can describe a qualitative project with longitudinal data collection as a qualitative longitudinal study, without being aware that QLR is a specific form of study. Balmer [ 64 ] described how their group conducted serial interviews with medical students over several years before they became aware of QLR as a method of study. Within our networks, we have met researchers with similar experiences. Likewise, peer reviewers and editorial boards might not be accustomed to evaluating QLR manuscripts. In our results, 138 journals published one article between 2017 and 2019, and that might not be enough for editorial boards and peer reviewers to develop knowledge to enable them to closely evaluate manuscripts with a QLR method.

In 2007, Holland and colleagues [ 65 ] mapped QLR in the UK and described the following four categories of QLR: 1) mixed methods approaches with a QLR component; 2) planned prospective longitudinal studies; 3) follow-up studies complementing a previous data collection with follow-up; and 4) evaluation studies. Examples of all these categories can be found among the articles in this method study; however, our results do paint a more complex picture. According to our results, Holland’s categories are not multi-exclusive. For example, studies with intentions to evaluate or implement practices often used a mixed methods design and were therefore eligible for both categories one and four described above. Additionally, regarding the follow-up studies, it was seldom clearly described if they were planned as a two-time-point study or if researchers had gained an opportunity to follow up on previous data collection. When we tried to categorize QLR articles according to the data collection design, we could not identify multi-exclusive categories. Instead, we identified the following three components of longitudinal data collection: 1) entities followed across time; 2) tempo; and 3) preplanned or adapted data collection approaches. However, the most common combination was preplanned studies that followed individuals longitudinally with three or more time points.

The use of QLR differs between disciplines [ 14 ]. Our results show some patterns for QLR within health research. Firstly, the QLR projects were large and complex; they often included several types of populations and various data materials, and were presented in several articles. Secondly, most studies focused upon the individual perspective, following individuals across time, and using individual interviews. Thirdly, the data collection periods varied, but 53% of the articles had a data collection period of 1 year or shorter. Finally, patients were the most prevalent population, even though topics varied greatly. Previously, two other reviews that focused on QLR in different parts of health research (e.g., nursing [ 4 ] and gerontology [ 66 ]) pointed in the same direction. For example, individual interviews or a combination of data materials were commonly used, and most studies were shorter than 1 year but a wide range existed [ 4 , 66 ].

Considerations when planning a QLR project

Based on our results, we argue that when health researchers plan a QLR study, they should reflect upon their perspective of time/change and decide what part change should play in their QLR study. If researchers decide that change should play the main role in their project, then they should aim to focus on change as the phenomenon of interest. However, in some research, change might be an important part of the plot, without having the main role, and change in relation to the outcomes might be a better perspective. In such studies, participants with change, no change or different kinds of change are compared to explore possible explanations for the change. In our results, change in relation to the outcomes was often used in relation to intervention studies where participants who reached a desired outcome were compared to individuals who did not. Furthermore, for some research studies, change is part of the context in which the research takes place. This can be the case when certain experiences happen during a period of change; for example, when the aim is to explore the experience of everyday life during rehabilitation after stroke. In such cases a longitudinal data collection could be advisable (e.g., repeated interviews often give a deep relationship between interviewer and participants as well as the possibility of gaining greater depth in interview answers during follow-up interviews [ 15 ]), but the study might not be called a QLR study since it does not focus upon change [ 13 ]. We suggest that researchers make informed decisions of what kind of longitudinal perspective they set out to investigate and are transparent with their sources of methodological inspiration.

We would argue that length of data collection period, type of entities, and data materials should be in accordance with the type of change/changing processes that a study focuses on. Individual change is important in health research, but researchers should also remember the possibility of investigating changes in families, working groups, organizations and wider communities. Using these types of entities were less common in our material and could probably grant new perspectives to many research topics within health. Similarly, using several types of data materials can complement the insights that individual interviews can give. A large majority of the articles in our results had a preplanned data collection. Participant-adapted data collection can be a way to work in alignment with a “time-as-fluid” conceptualization of time because the events of subjective importance to participants can be more in focus and participants (or other entities) change processes can differ substantially across cases. In studies with lengthy and spaced-out data collection periods and/or uncertainty in trajectories, researchers should consider participant-adapted or participant entry data collection. For example, some participants can be followed for longer periods and/or with more frequency.

Finally, researchers should consider how to best publish and disseminate their results. Many QLR projects are large, and the results are divided across several articles when they are published. In our results, 21 papers self-identified as a mixed methods project or as part of a larger mixed methods project, but most of these did not include quantitative data in the article. This raises the question of how to best divide a large research project into suitable pieces for publication. It is an evident risk that the more interesting aspects of a mixed methods project are lost when the qualitative and quantitative parts are analyzed and published separately. Similar risks occur, for example, when data have been collected from several types of populations but are then presented per population type (e.g., one article with patient data and another with caregiver data). During the work with our study, we also came across studies where data were collected longitudinally, but the results were divided into publications per time point. We do not argue that these examples are always wrong, there are situations when these practices are appropriate. However, it often appears that data have been divided without much consideration. Instead, we suggest a thematic approach to dividing projects into publications, crafting the individual publications around certain ideas or themes and thus using the data that is most suitable for the particular research question. Combining several types of data and/or several populations in an analysis across time is in fact what makes QLR an interesting approach.

Strengths and limitations

This method study intended to paint a broad picture regarding how longitudinal qualitative methods are used within the health research field by investigating 299 published articles. Method research is an emerging field, currently with limited methodological guidelines [ 21 ], therefore we used scoping review method to support this study. In accordance with scoping review method we did not use quality assessment as a criterion for inclusion [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. This can be seen as a limitation because we made conclusions based upon a set of articles with varying quality. However, we believe that learning can be achieved by looking at both good and bad examples, and innovation may appear when looking beyond established knowledge, or assessing methods from different angles. It should also be noted that the results given in percentages hold no value for what procedures that are better or more in accordance with QLR, the percentages simply state how common a particular procedure was among the articles.

As described, the included articles showed much variation in the method descriptions. As the basis for our results, we have only charted explicitly written text from the articles, which might have led to an underestimation of some results. The researchers might have had a clearer rationale than described in the reports. Issues, such as word restrictions or the journal’s scope, could also have influenced the amount of detail that was provided. Similarly, when charting how articles drew on a traditional methodology, only data from the articles that clearly stated the methodologies they used (e.g., phenomenology) were charted. In some articles, literature choices or particular research strategies could implicitly indicate that the researchers had been inspired by certain methodologies (e.g., referring to grounded theory literature and describing the use of simultaneous data collection and analysis could indicate that the researchers were influenced by grounded theory), but these were not charted as using a particular methodological tradition. We used the articles’ aims and objectives/research questions to investigate their longitudinal perspectives. However, as researchers have different writing styles, information regarding the longitudinal perspectives could have been described in surrounding text rather than in the aim, which might have led to an underestimation of the longitudinal perspectives.

The experience and diversity of the research team in our study was a strength. The nine authors on the team represent ten universities and three countries, and have extensive experience in different types of qualitative research, QLR and review methods. The different level of experiences with QLR within the team (some authors have worked with QLR in several projects and others have qualitative experience but no experience in QLR) resulted in interesting discussions that helped drive the project forward. These experiences have been useful for understanding the field.

Based on a method study of 299 articles, we can conclude that QLR in health research articles published between 2017 and 2019 often contain comprehensive complex studies with a large variation in topics. Some research was thoroughly designed to capture time/change throughout the methodology, focus and data collection, while other articles included a few elements of QLR. Longitudinal data collection included several components, such as what entities were followed across time, the tempo of data collection, and to what extent the data collection was preplanned or adapted across time. In sum, health researchers need to be considerate and make informed choices when designing QLR projects. Further research should delve deeper into what kind of research questions go well with QLR and investigate the best practice examples of presenting QLR findings.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed in this current study are available in supplementary file 6 .

Qualitative method references were defined as a journal article or book with a title that indicated an aim to guide researchers in qualitative research methods and/or research theories. Primary studies, theoretical works related to the articles’ research topics, protocols, and quantitative method literature were excluded. References written in a language other than English was also excluded since the authors could not evaluate their content.

QLR method references were defined as a journal article or book that 1) focused on qualitative methodological questions, 2) used terms such as ‘longitudinal’ or ‘time’ in the title so it was evident that the focus was on longitudinal qualitative research. Referring to another original QLR study was not counted as using QLR method literature.

Words were charted depending on their word stem, e.g., change, changes and changing were all charted as change.

It should be noted that here time span refers to the data collection related to each participant or case. Researchers could collect data for 2 years but follow each participant for 6 months.

Calman L, Brunton L, Molassiotis A. Developing longitudinal qualitative designs: lessons learned and recommendations for health services research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:14.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Solomon P, Nixon S, Bond V, Cameron C, Gervais N. Two approaches to longitudinal qualitative analyses in rehabilitation and disability research. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42:3566–72.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Grossoehme D, Lipstein E. Analyzing longitudinal qualitative data: the application of trajectory and recurrent cross-sectional approaches. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:136.

SmithBattle L, Lorenz R, Reangsing C, Palmer JL, Pitroff G. A methodological review of qualitative longitudinal research in nursing. Nurs Inq. 2018;25:e12248.

Tuthill EL, Maltby AE, DiClemente K, Pellowski JA. Longitudinal qualitative methods in health behavior and nursing research: assumptions, design, analysis and lessons learned. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:10.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

McCoy LK. Longitudinal qualitative research and interpretative phenomenological analysis: philosophical connections and practical considerations. Qual Res Psychol. 2017;14:442–58.

Article Google Scholar

Bennett D, Kajamaa A, Johnston J. How to... Do longitudinal qualitative research. Clin Teach. 2020;17:489–92.

Plano Clark V, Anderson N, Wertz JA, Zhou Y, Schumacher K, Miaskowski C. Conceptualizing longitudinal mixed methods designs: a methodological review of health sciences research. J Mix Methods Res. 2014;23:1–23.

Google Scholar

Thomson R, Plumridge L, Holland J. Longitudinal qualitative research: a developing methodology. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2003;6:185–7.

Neale B. The craft of qualitative longitudinal research: thousand oaks. Sage. 2021.

Balmer DF, Varpio L, Bennett D, Teunissen PW. Longitudinal qualitative research in medical education: time to conceptualise time. Med Educ. 2021;55:1253–60.

Smith N. Cross-sectional profiling and longitudinal analysis: research notes on analysis in the longitudinal qualitative study, 'Negotiating transitions to Citizenship'. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2003;6:273–7.

Saldaña J. Longitudinal qualitative research - analyzing change through time. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press; 2003.

Corden A, Millar J. Time and change: a review of the qualitative longitudinal research literature for social policy. Soc Policy Soc. 2007;6:583–92.

Thorne S. Interpretive description: qualitative research for applied practice (2nd ed): Routledge; 2016.

Book Google Scholar

Kneck Å, Audulv Å. Analyzing variations in changes over time: development of the pattern-oriented longitudinal analysis approach. Nurs Inq. 2019;26:e12288.

Whiffin CJ, Bailey C, Ellis-Hill C, Jarrett N. Challenges and solutions during analysis in a longitudinal narrative case study. Nurse Res. 2014;21:20–62.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation. 2021;19:3–10.

Mbuagbaw L, Lawson DO, Puljak L, Allison DB, Thabane L. A tutorial on methodological studies: the what, when, how and why. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20:226.