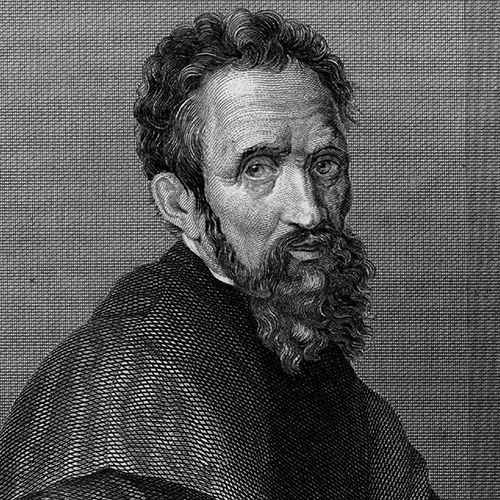

Michelangelo

Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo created the 'David' and 'Pieta' sculptures and the Sistine Chapel and 'Last Judgment' paintings.

(1475-1564)

Who Was Michelangelo?

What followed was a remarkable career as an artist, famed in his own time for his artistic virtuosity. Although he always considered himself a Florentine, Michelangelo lived most of his life in Rome, where he died at age 88.

Michelangelo was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Italy, the second of five sons.

When Michelangelo was born, his father, Leonardo di Buonarrota Simoni, was briefly serving as a magistrate in the small village of Caprese. The family returned to Florence when Michelangelo was still an infant.

His mother, Francesca Neri, was ill, so Michelangelo was placed with a family of stonecutters, where he later jested, "With my wet-nurse's milk, I sucked in the hammer and chisels I use for my statues."

Indeed, Michelangelo was less interested in schooling than watching the painters at nearby churches and drawing what he saw, according to his earliest biographers (Vasari, Condivi and Varchi). It may have been his grammar school friend, Francesco Granacci, six years his senior, who introduced Michelangelo to painter Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Michelangelo's father realized early on that his son had no interest in the family financial business, so he agreed to apprentice him, at the age of 13, to Ghirlandaio and the Florentine painter's fashionable workshop. There, Michelangelo was exposed to the technique of fresco (a mural painting technique where pigment is placed directly on fresh, or wet, lime plaster).

Medici Family

From 1489 to 1492, Michelangelo studied classical sculpture in the palace gardens of Florentine ruler Lorenzo de' Medici of the powerful Medici family. This extraordinary opportunity opened to him after spending only a year at Ghirlandaio’s workshop, at his mentor’s recommendation.

This was a fertile time for Michelangelo; his years with the family permitted him access to the social elite of Florence — allowing him to study under the respected sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni and exposing him to prominent poets, scholars and learned humanists.

He also obtained special permission from the Catholic Church to study cadavers for insight into anatomy, though exposure to corpses had an adverse effect on his health.

These combined influences laid the groundwork for what would become Michelangelo's distinctive style: a muscular precision and reality combined with an almost lyrical beauty. Two relief sculptures that survive, "Battle of the Centaurs" and "Madonna Seated on a Step," are testaments to his phenomenal talent at the tender age of 16.

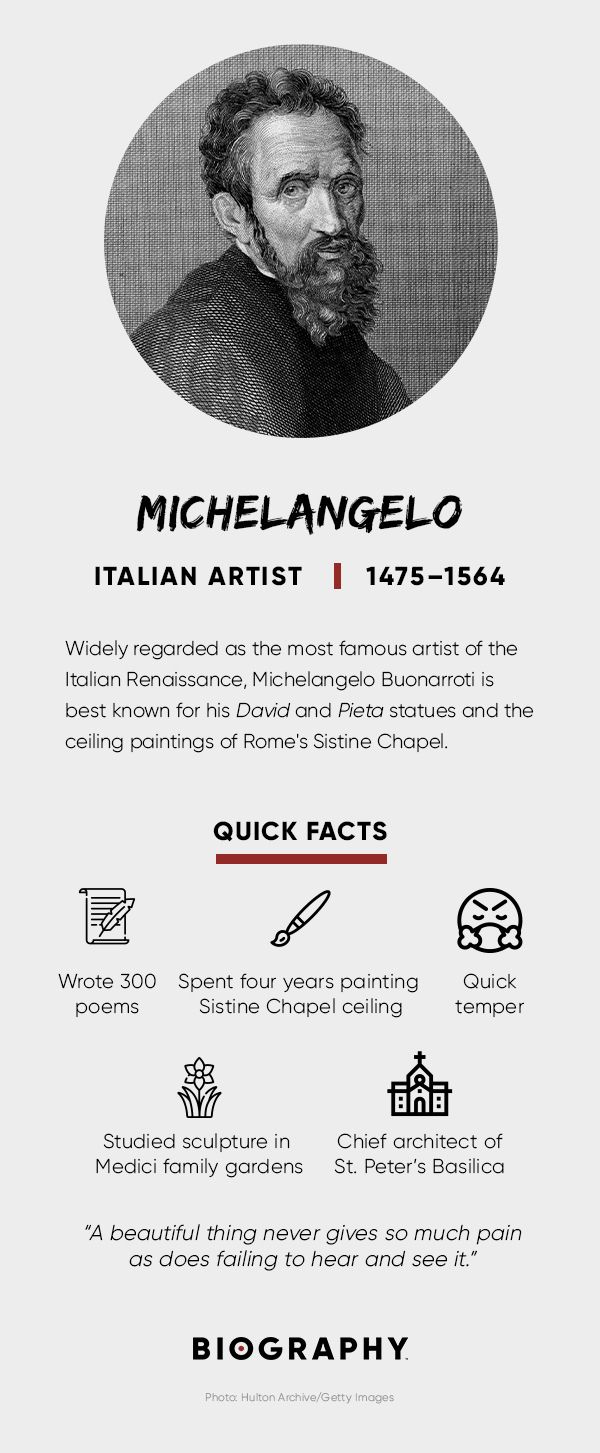

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MICHELANGELO FACT CARD

Move to Rome

Political strife in the aftermath of Lorenzo de' Medici’s death led Michelangelo to flee to Bologna, where he continued his study. He returned to Florence in 1495 to begin work as a sculptor, modeling his style after masterpieces of classical antiquity.

There are several versions of an intriguing story about Michelangelo's famed "Cupid" sculpture, which was artificially "aged" to resemble a rare antique: One version claims that Michelangelo aged the statue to achieve a certain patina, and another version claims that his art dealer buried the sculpture (an "aging" method) before attempting to pass it off as an antique.

Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio bought the "Cupid" sculpture, believing it as such, and demanded his money back when he discovered he'd been duped. Strangely, in the end, Riario was so impressed with Michelangelo's work that he let the artist keep the money. The cardinal even invited the artist to Rome, where Michelangelo would live and work for the rest of his life.

Personality

Though Michelangelo's brilliant mind and copious talents earned him the regard and patronage of the wealthy and powerful men of Italy, he had his share of detractors.

He had a contentious personality and quick temper, which led to fractious relationships, often with his superiors. This not only got Michelangelo into trouble, it created a pervasive dissatisfaction for the painter, who constantly strived for perfection but was unable to compromise.

He sometimes fell into spells of melancholy, which were recorded in many of his literary works: "I am here in great distress and with great physical strain, and have no friends of any kind, nor do I want them; and I do not have enough time to eat as much as I need; my joy and my sorrow/my repose are these discomforts," he once wrote.

In his youth, Michelangelo had taunted a fellow student, and received a blow on the nose that disfigured him for life. Over the years, he suffered increasing infirmities from the rigors of his work; in one of his poems, he documented the tremendous physical strain that he endured by painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Political strife in his beloved Florence also gnawed at him, but his most notable enmity was with fellow Florentine artist Leonardo da Vinci , who was more than 20 years his senior.

Poetry and Personal Life

Michelangelo's poetic impulse, which had been expressed in his sculptures, paintings and architecture, began taking literary form in his later years.

Although he never married, Michelangelo was devoted to a pious and noble widow named Vittoria Colonna, the subject and recipient of many of his more than 300 poems and sonnets. Their friendship remained a great solace to Michelangelo until Colonna's death in 1547.

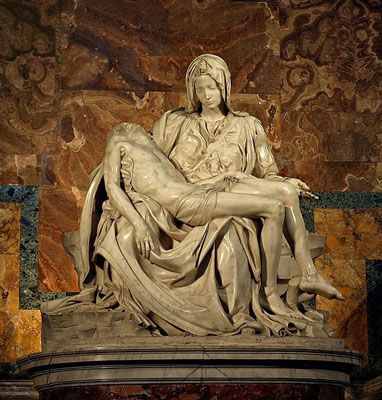

Soon after Michelangelo's move to Rome in 1498, the cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas, a representative of the French King Charles VIII to the pope, commissioned "Pieta," a sculpture of Mary holding the dead Jesus across her lap.

Michelangelo, who was just 25 years old at the time, finished his work in less than one year, and the statue was erected in the church of the cardinal's tomb. At 6 feet wide and nearly as tall, the statue has been moved five times since, to its present place of prominence at St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City.

Carved from a single piece of Carrara marble, the fluidity of the fabric, positions of the subjects, and "movement" of the skin of the Piet — meaning "pity" or "compassion" — created awe for its early viewers, as it does even today.

It is the only work to bear Michelangelo’s name: Legend has it that he overheard pilgrims attribute the work to another sculptor, so he boldly carved his signature in the sash across Mary's chest. Today, the "Pieta" remains a universally revered work.

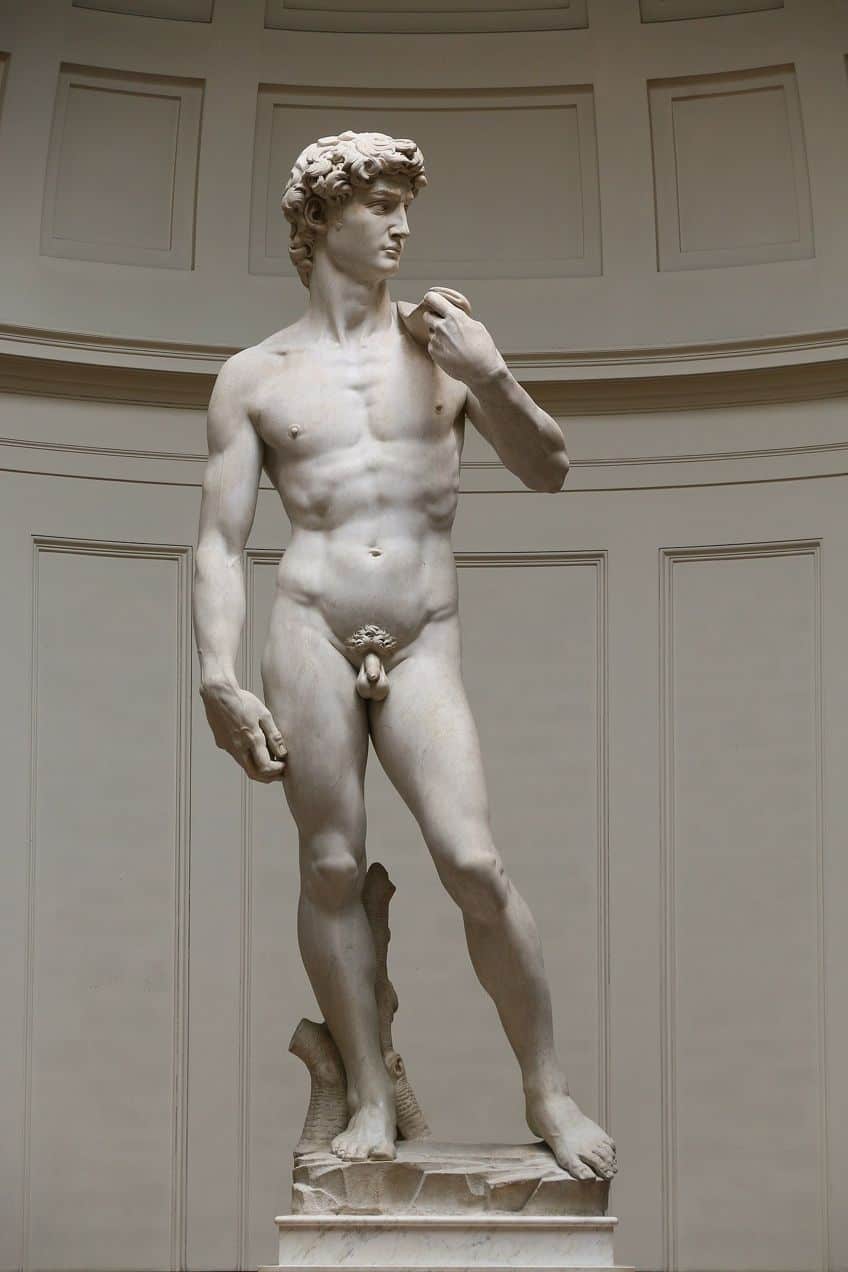

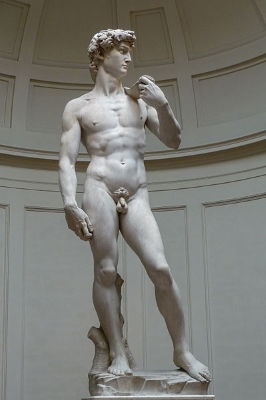

Between 1501 and 1504, Michelangelo took over a commission for a statue of "David," which two prior sculptors had previously attempted and abandoned, and turned the 17-foot piece of marble into a dominating figure.

The strength of the statue's sinews, vulnerability of its nakedness, humanity of expression and overall courage made the "David" a highly prized representative of the city of Florence.

Originally commissioned for the cathedral of Florence, the Florentine government instead installed the statue in front of the Palazzo Vecchio. It now lives in Florence’s Accademia Gallery .

Sistine Chapel

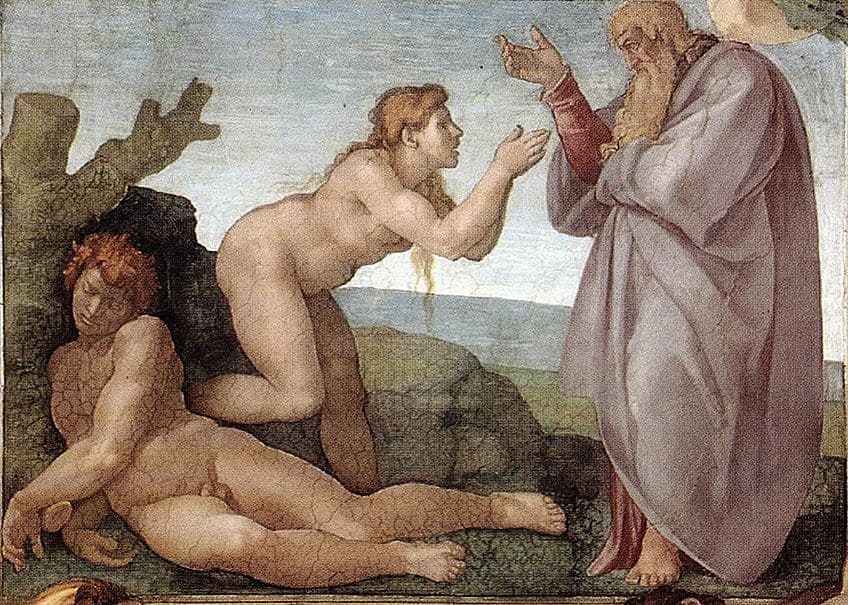

Pope Julius II asked Michelangelo to switch from sculpting to painting to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which the artist revealed on October 31, 1512. The project fueled Michelangelo’s imagination, and the original plan for 12 apostles morphed into more than 300 figures on the ceiling of the sacred space. (The work later had to be completely removed soon after due to an infectious fungus in the plaster, then recreated.)

Michelangelo fired all of his assistants, whom he deemed inept, and completed the 65-foot ceiling alone, spending endless hours on his back and guarding the project jealously until completion.

The resulting masterpiece is a transcendent example of High Renaissance art incorporating the symbology, prophecy and humanist principles of Christianity that Michelangelo had absorbed during his youth.

'Creation of Adam'

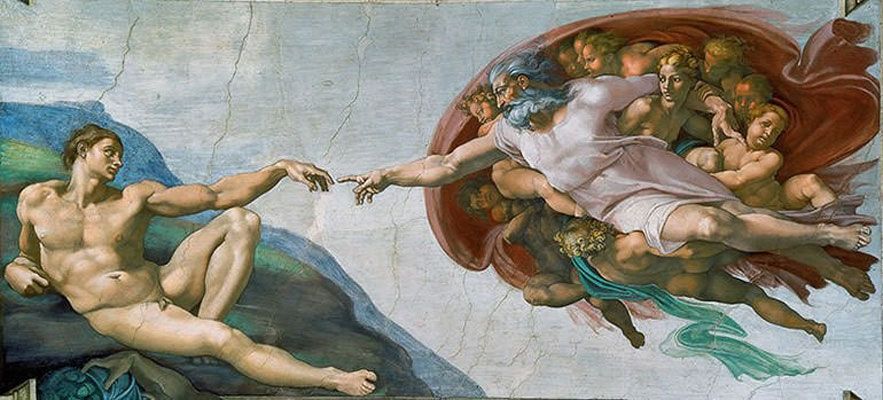

The vivid vignettes of Michelangelo's Sistine ceiling produce a kaleidoscope effect, with the most iconic image being the " Creation of Adam," a famous portrayal of God reaching down to touch the finger of man.

Rival Roman painter Raphael evidently altered his style after seeing the work.

'Last Judgment'

Michelangelo unveiled the soaring "Last Judgment" on the far wall of the Sistine Chapel in 1541. There was an immediate outcry that the nude figures were inappropriate for so holy a place, and a letter called for the destruction of the Renaissance's largest fresco.

The painter retaliated by inserting into the work new portrayals: his chief critic as a devil and himself as the flayed St. Bartholomew.

Architecture

Although Michelangelo continued to sculpt and paint throughout his life, following the physical rigor of painting the Sistine Chapel he turned his focus toward architecture.

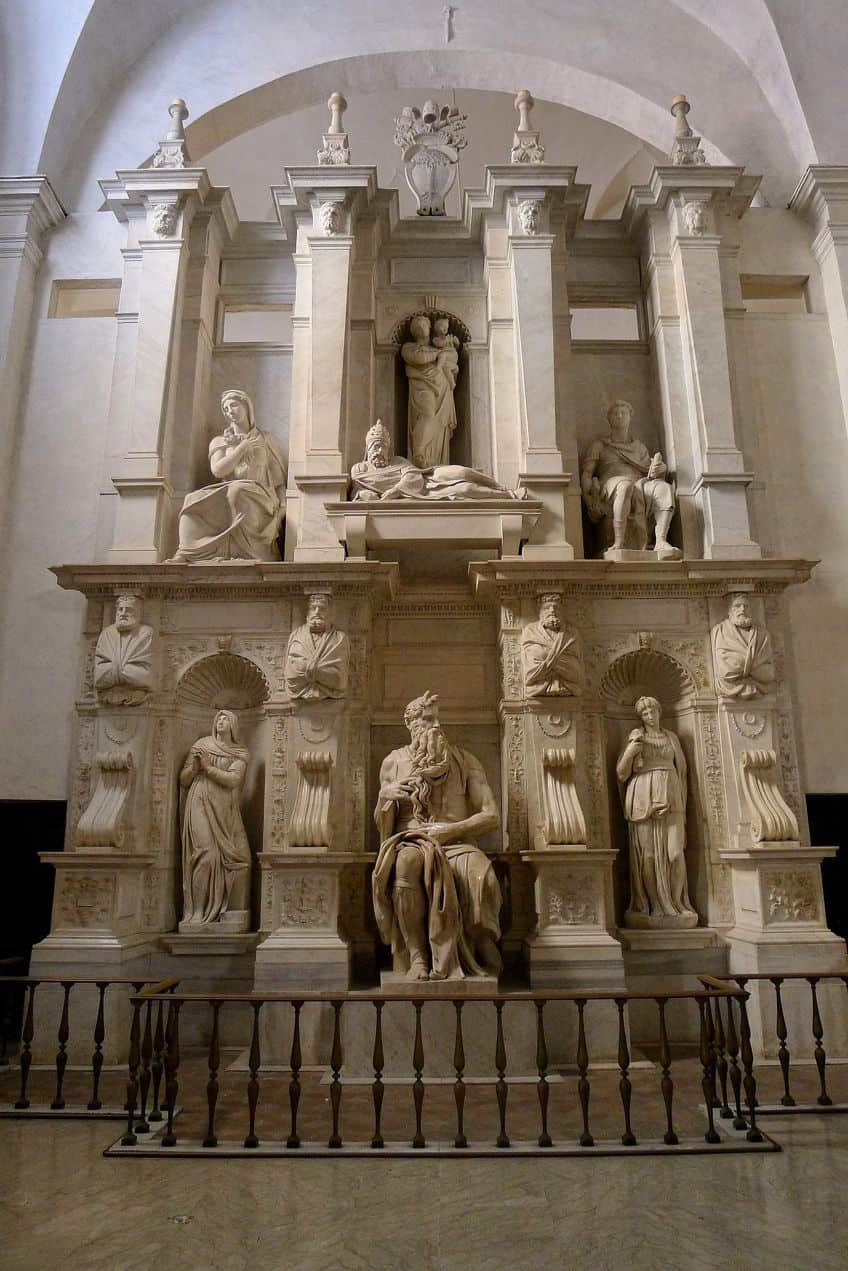

He continued to work on the tomb of Julius II, which the pope had interrupted for his Sistine Chapel commission, for the next several decades. Michelangelo also designed the Medici Chapel and the Laurentian Library — located opposite the Basilica San Lorenzo in Florence — to house the Medici book collection. These buildings are considered a turning point in architectural history.

But Michelangelo's crowning glory in this field came when he was made chief architect of St. Peter's Basilica in 1546.

Was Michelangelo Gay?

In 1532, Michelangelo developed an attachment to a young nobleman, Tommaso dei Cavalieri, and wrote dozens of romantic sonnets dedicated to Cavalieri.

Despite this, scholars dispute whether this was a platonic or a homosexual relationship.

Michelangelo died on February 18, 1564 — just weeks before his 89th birthday — at his home in Macel de'Corvi, Rome, following a brief illness.

A nephew bore his body back to Florence, where he was revered by the public as the "father and master of all the arts." He was laid to rest at the Basilica di Santa Croce — his chosen place of burial.

Unlike many artists, Michelangelo achieved fame and wealth during his lifetime. He also had the peculiar distinction of living to see the publication of two biographies about his life, written by Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi.

Appreciation of Michelangelo's artistic mastery has endured for centuries, and his name has become synonymous with the finest humanist tradition of the Renaissance.

Watch "Michelangelo: Artist and Man" on HISTORY Vault

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Michelangelo Buonarroti

- Birth Year: 1475

- Birth date: March 6, 1475

- Birth City: Caprese (Republic of Florence)

- Birth Country: Italy

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo created the 'David' and 'Pieta' sculptures and the Sistine Chapel and 'Last Judgment' paintings.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Pisces

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Michelangelo was just 25 years old at the time when he created the 'Pieta' statue.

- For the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo fired all of his assistants and painted the 65-foot ceiling alone.

- Despite his immense talent, Michelangelo had a quick temper and contempt for authority.

- Death Year: 1564

- Death date: February 18, 1564

- Death City: Rome

- Death Country: Italy

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Michelangelo Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/michelangelo

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: March 4, 2020

- Lord, grant that I may always desire more than I accomplish.

- I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

- I am here in great distress and with great physical strain, and have no friends of any kind, nor do I want them; and I do not have enough time to eat as much as I need; my joy and my sorrow/my repose are these discomforts.

- With my wet-nurse's milk, I sucked in the hammer and chisels I use for my statues.

- A beautiful thing never gives so much pain as does failing to hear and see it.

- Faith in oneself is the best and safest course.

- If people knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, it wouldn't seem so wonderful at all.

- Critique by creating.

- The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.

- With few words I will make thee understand my soul.

- Lord, make me see thy glory in every place.

- Genius is eternal patience.

- If you knew how much work went into it, you wouldn't call it genius.

Famous Painters

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

Margaret Keane

Andy Warhol

Michelangelo Buonarroti – A Detailed Michelangelo Biography

Michelangelo Buonarroti is considered by many to be among the most significant luminaries in the history of art. But, what is Michelangelo famous for and what did Michelangelo study? Michelangelo was one of those incredibly talented people that excelled in multiple disciplines, and was renowned for his sculptures, architecture, and paintings. To find out more about this fascinating Renaissance man, let’s take a deeper look at Michelangelo’s biography, as well as address some common questions on the topic, such as, “where did Michelangelo live?”, “was Michelangelo married?”, “how did Michelangelo die?”, and “how old was Michelangelo when he died?”.

Table of Contents

- 1.1 Childhood and Early Training

- 1.2.1 Time in Florence

- 1.2.2 Time in Rome

- 1.2.3 The Making of David and Other Works

- 1.2.4 Rivalries

- 1.3.1 The Sistine Chapel

- 1.3.2 Julius II’s Tomb

- 1.4 Late Period

- 2 The Legacy of Michelangelo

- 3 Notable Artworks

- 4.1 How Did Michelangelo Die?

- 4.2 How Old Was Michelangelo When He Died?

- 4.3 What Did Michelangelo Study?

- 4.4 Was Michelangelo Married to Anyone?

- 4.5 Where Did Michelangelo Live?

Exploring Michelangelo’s Biography

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born in Caprese, a little village close to Arezzo. He came from a middle-class background and his father was a banker. His mother had suffered for many years from an illness which unfortunately took her life when the young Michelangelo was only six years of age. His father had no choice but to leave him in the care of his nanny as he did not have the time to raise him. The nanny’s husband was a stonecutter by trade and it is believed that this is where the young artist’s passion for marble first began.

Childhood and Early Training

Even at the age of 13, it was apparent to Michelangelo’s father that the young boy had no desire to follow the family trade of banking and so he was sent to Domenico Ghirlandaio’s studio to serve as his apprentice. This studio would be the perfect place for the aspiring artist to pick up all the necessary techniques and tricks of the trade, with Ghirlandaio possessing a thorough knowledge of draftsmanship and fresco painting techniques. However, it is believed that Michelangelo found that his personal views on art often clashed with those of his mentor, and he preferred to study the works of the masters such as Donatello , Masaccio, and Giotto than follow Ghirlandaio’s methods. He had only been working at the studio for around a year when the ruler of Florence, Lorenzo de’ Medici, asked Ghirlandaio to let Michelangelo and Francesco Grancci (his two best students) join his Humanist academy.

In Renaissance Florence at this time, new ideas and philosophies were starting to emerge and artists were encouraged to study the humanities in order to supplement their artistic works with an understanding of ancient Greco-Roman art and philosophy.

The more progressive artists were establishing a Renaissance style that would promote humanist principles and recognize man’s essential role in creating the modern world, moving away from Gothic imagery and devotional works. While there, Michelangelo Buonarroti trained under Bertoldo di Giovanni, the bronze sculptor, who exposed him to the iconic classical statues in the Lorenzo Palace. Michelangelo, like Leonardo da Vinci , was not content with studying the principles of anatomy from classical sculptures. He undertook his own studies into human anatomy, dissecting corpses, and sketching from models until he got to the point where the human body no longer held any mysteries for him, and he felt like he quite literally knew the human body inside-out.

Yet, he differed from da Vinci in the fact that anatomy was just one riddle to be figured out of many for the other artist, whereas for Michelangelo, it was the single most important problem that he wanted to master above all others. Around this time, he received the necessary permission from the friars of Santo Spirito Church to examine corpses in the convent’s hospital, where he would acquire a thorough grasp of the anatomy of humans. After Lorenzo de’ Medici passed away in 1492, the 17-year-old Michelangelo found himself without a patron and was offered shelter in the monastery. Michelangelo produced a strikingly life-like wooden sculpture that hung over the main altar out of gratitude. It was reported as lost after the French conquest in the late 18th century, although it had actually been transported to another church and painted to conceal its identity.

The Republic of Florence was threatened with siege by the French in 1494. Concerned about his safety, Michelangelo relocated to Bologna, with a brief detour in Venice. In the city, he met Giovan Francesco Aldrovandi, a rich Bolognese senator who was successful in obtaining the commission for the outstanding statuettes for the marble tomb lid for the Arca of St. Dominic for Michelangelo. The original lid was produced by Niccolo dell’Arca in 1473, with Michelangelo carving the few surviving figures in 1496, including Saint Petronio, Saint Proculus, and an angel with candles.

Michelangelo, who was still just 19 years old at the time, eclipsed the production of the elder sculptor with his unprecedented detail in the folds of the linen and fabric, and in the form of Petronio, to whom he added a palpable feeling of motion by depicting him in mid-step.

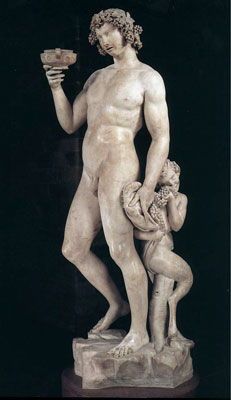

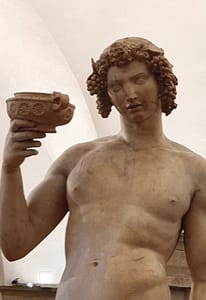

Time in Florence

Once the risk of a French invasion passed, Michelangelo temporarily returned back to Florence. He was working on two sculptures: one of St. John the Baptist and another depicting a cupid. Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio bought the sculpture after being deceived into thinking it was actually an antique statue. Despite his initial anger upon learning about the deceit, Cardinal Riario was rather impressed by the young sculptor’s talent and summoned him to Rome to start on a new project. Michelangelo sculpted a figure of the Roman god of wine, Bacchus, for the commission, which was ultimately rejected by the Cardinal, who felt it was politically inappropriate to be affiliated with a nude pagan figure. Michelangelo, who had by that point gained notoriety for being temperamental, was enraged and told Condivi, his biographer, years later to instead record it as an order from his banker, Jacopo Galli, the man who ultimately bought the finished sculpture.

Time in Rome

After finishing the statue, Michelangelo stayed in Rome, and Cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas ordered his Pietà for the chapel in Saint Peter’s Basilica for the King of France. “Pietà” was actually a generalized label assigned to devotional works aimed to encourage worshippers to participate in penitent prayer, but Michelangelo’s piece was its most renowned interpretation. Michelangelo’s sculpture was unique in that he created two characters from a single piece of marble. Additionally, his presentation of his figures, which highlighted the artist’s attention to emotion and naturalism, earned Michelangelo considerable praise and new followers. Despite the fact that his reputation as one of the most divinely talented individuals of the time was assured, Michelangelo failed to secure any big assignments for another two years.

Yet, he was not particularly concerned about a lack of employment or financial stability.

“No matter how affluent I may have been, I always behaved like a poor man”, he would declare to Condivi at the end of his life. Girolamo Savonarola, a Florentine puritanical monk, would become notorious in 1497 for his Bonfire of the Vanities, an occurrence in which he and his followers publicly destroyed paintings and books. Their behavior disrupted what had been a flourishing era of Renaissance culture. Michelangelo did not return to Florence until Savonarola was deposed a year later. In 1501, he received an order from the Guild of Wool to finish an incomplete project started four decades earlier by Agostino di Duccio.

The Making of David and Other Works

The 17-foot-tall naked figure of the scriptural hero David was completed in 1504. The piece was a testament to his unmatched talent in sculpting strikingly lifelike human beings out of cold marble. It has become the definitive symbol of the Renaissance concept of ideal humanity . Even though the artwork was initially planned for the cathedral’s buttress, the grandeur of the completed project persuaded Michelangelo’s peers to set it in a more significant location, to be decided by a committee of artists and influential figures. They opted to place the statue in front of the Palazzo Vecchio’s entryway as a representation of the Florentine Republic. Upon the iconic sculpture’s completion, he received numerous painting commissions.

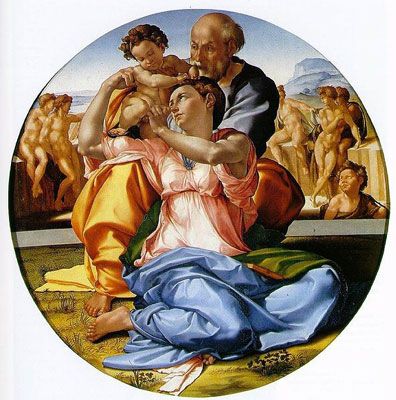

Doni Tondo (1504) is the only painting of Michelangelo known to survive to the present day. Scholars believe the artwork reveals the artist’s infatuation with Da Vinci’s works. They claim that Michelangelo repeatedly denied being influenced by anybody, and his comments were typically accepted without question. However, Da Vinci’s return to Florence following almost two decades was exhilarating to the city’s younger artists, and later academics typically accepted that Michelangelo was among those artists influenced by his output. Competition between Michelangelo and his contemporaries was strong throughout the High Renaissance in Florence, with painters all competing for the same commissions.

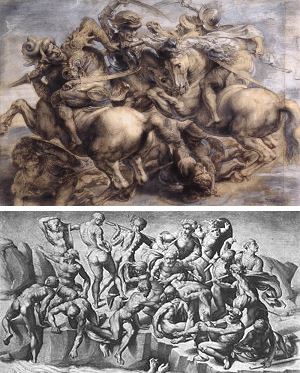

Da Vinci was considered to be the most notable individual of the whole Florentine brotherhood of Renaissance masters and 23 years older than Michelangelo. Yet an unstated rivalry between the two artists was well recognized. Piero Soderini commissioned both painters to paint opposite walls of the Palace Vecchio’s Salone dei Cinquecento in 1503. It was a momentous time in art history when these two titans contended for the palm, and everyone in Florence observed their preparatory efforts with eager anticipation. Unfortunately,

Soderini abandoned the project, and neither of the artworks were ever completed. Da Vinci traveled to Milan, while Pope Julius II summoned Michelangelo to Rome.

Mature Period

When in Rome, Michelangelo began work on the Pope’s tomb, a gigantic mausoleum that was scheduled to be finished in five years. After visiting the famed Carrara quarries, he spent six months carefully searching for the ideal blocks of marble from which to create his figures. To his great disappointment, Julius summoned Michelangelo to Rome, where he heard that the structure designated to hold the tomb was to be demolished and the undertaking as a whole halted. Michelangelo was enraged and believed that there was some kind of plot to destroy him. He even suspected that Bramante, the new St. Peter’s Basilica’s architect, was plotting to poison him. Michelangelo then returned to Florence, enraged, and penned a letter to the Pope, voicing his indignation at his mistreatment in Rome.

The Sistine Chapel

The artist found himself in the midst of a complex diplomatic struggle between Rome and Florence. The head of the Florence city government convinced Michelangelo to return to Julius II’s employment and provided him with a recommendation letter in which he stated that his art was unparalleled across the whole of Italy, possibly even throughout the whole world. After creating a massive bronze figure of the pope for the recently acquired city of Bologna (which was abruptly demolished after papal invaders were defeated),

Julius commissioned Michelangelo to finish a project begun by Ghirlandaio, Botticelli, and others.

The assignment was to create frescoes for the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and it is believed that Bramante persuaded the Pope that Michelangelo was the ideal person for the task, despite the fact that Michelangelo was primarily recognized for his sculptures and hence almost certainly would not succeed in this massive endeavor. Michelangelo would spend the next four years working on the Sistine Chapel. He painted the ceiling while lying on his back on a scaffold structure made from wood, with only one assistant to mix the paint. What emerged, though, was a significant work of incredible talent depicting Old Testament narratives.

The completed painting, which featured multiple naked individuals (an unusual sight at the time), would ultimately become a magnificent masterwork of artistic expression. After completing the Sistine ceiling, he went back to working on the initial project for Pope Julius’ tomb. After the passing of Pope Julius II in 1513, financing for his tomb came to a halt, and the artist was assigned by the new Pope Leo X to start working on the Basilica San Lorenzo’s façade, Florence’s largest church. Michelangelo worked on it for the next three years before abandoning it because of a shortage of funding. Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici ruled Florence at the time, and the two men had a strong professional connection. Actually, under the Cardinal, Michelangelo enjoyed considerable creative freedom, which enabled him to venture deeper into the sphere of architectural design.

Julius II’s Tomb

Florence was proclaimed a republic following the conquest and pillage of Rome by Charles V’s forces in 1527. Nevertheless, the city was besieged in October 1529 before eventually falling in August 1530. The Medici family was reinstated to authority in the city by a new accord between Charles V and Pope Clement VII. After building defense structures for the fortification of Florence, Michelangelo was re-hired by Pope Clement, who offered him a new contract to resume work on Pope Julius II’s tomb. Michelangelo turned to fresco painting once more in Rome, this time for Pope Paul III. In 1534, he returned to the location of one of his greatest accomplishments, painting a huge and vibrant redemption tale for the Sistine Chapel’s altar wall.

The Last Judgment, with its concept of Jesus’ “second coming,” was part of Roman Catholic teaching’s great narrative, and it took him seven years to complete.

Late Period

Toward the end of his career, Michelangelo began to focus more on architectural designs, and his most recognized work is St. Peter’s Basilica. Pope Julius II suggested removing the existing Basilica and replacing it with the “greatest structure in Christendom”. While Donato Bramante’s design was selected in 1505, and foundations were constructed the year after that, minimal progress had been made since. Michelangelo was in his 70s when he hesitantly took over the project from his rival (Bramante) in 1546, claiming, “I do this solely for the love of God and in reverence of the Apostle”. He continued working on the Basilica as Chief Architect for the remainder of his existence.

His most significant contribution to the design was his work on the dome at the Basilica’s eastern end. Except for the initial plans of Bramante, who had also envisioned an edifice to rival even Brunelleschi’s iconic dome in Florence, he disregarded all preceding architects’ ideas on the project. While the dome was not completed until after his passing, the foundation on which the dome was to be put was constructed, ensuring that the final draft of the dome remained loyal to Michelangelo’s grandiose vision.

The dome, which is still the biggest cathedral in the world, is both a Roman landmark and a tribute to Michelangelo’s eternal bond with the city.

Michelangelo’s final paintings, completed between 1542 and 1550, were a series of frescoes for the Vatican’s private Pauline Chapel. One of these works, The Crucifixion of St. Peter (1550), includes a horseman with a turban, and conservators and scholars think that this was actually a self-portrait. He also kept sculpting but did so privately for his own enjoyment. He finished a number of Pietàs, including the Deposition (1547), (which he actually tried to destroy) and his final work, the Rondanini Pietà (1564), on which he worked until his eventual death.

In his late years, the artist appears to have withdrawn more and more into himself. The poetry he composed indicates that he was tormented by uncertainties as to whether his artwork had been as sinful as others had accused it of being, while his letters made it obvious that the higher he gained in favor in the world, the more unpleasant and caustic he became. His infamous temper not only left others in awe but also in fear. His intensely private and reserved demeanor, including an instance where, while painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, he flung wooden boards at a passing Pope who he had confused for a spy, indicates he battled from bouts of paranoia.

The Legacy of Michelangelo

What is Michelangelo famous for? Michelangelo was regarded as the absolute master of sculpting when it came to the human form, which he accomplished with so much technical flair that his marble almost appeared to transform into life. Scholars have noted his influence on the works of other masters such as Peter Paul Rubens , Raphael, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, as well as Auguste Rodin, considered to be the last great sculptor to follow Michelangelo’s realist manner. Michelangelo has always been regarded as among a very small group of creative minds that were able to express the deepest and most tragic of human emotions to a degree of universal scope, along with other luminaries such as Beethoven and Shakespeare. And although the works of artists in this group were highly revered, they were seldom replicated and their subsequent influence was rather limited.

This was not because the artwork was regarded as too difficult to try and emulate – in fact, Raphael was regarded in the same light as Michelangelo as far as abilities are concerned, yet he was emulated much more by subsequent artists.

It appears that it was his particular style (that aspired to a “cosmic grandeur”), which artists found creatively inhibiting, and therefore did not try to mimic, except for a few artists such as Daniele de Volterra, who fully embraced his style. Rather, there were specific elements of his work that were embraced by certain movements. He was considered to be a master of anatomical drawing in the 17th century, for example, yet they found other aspects of his art lacking. Yet, while his influence may not always be so apparent or obvious, there is no doubt that his work had a very significant impact on the world of art.

Notable Artworks

Many consider Michelangelo’s ability to carve a figure (sometimes multiple figures) out of a single block of marble to be unmatched by any other sculptor. Yet, in addition to being so well-renowned as a sculptor, his artistic abilities knew no bounds, and he also created one of the most iconic frescoes in the history of art – the paintings on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel . That’s not even mentioning his world-famous architecture! Here are a few of his most notable artworks.

As we have discovered through our exploration of Michelangelo’s biography, he was an extremely talented yet temperamental individual who was determined to unravel all the secrets of human anatomy so that he could accurately depict our form in his famous sculptures. His talent was also the source of much paranoia in his life, often believing that someone was out to destroy him and his career. Despite his increasingly reclusive nature over the years, he was often called upon to produce works – many of which that have become some of the most iconic pieces in the history of art.

Frequently Asked Questions

How did michelangelo die.

It is believed that Michelangelo Buonarroti passed away due to a combination of issues with his kidneys and a simultaneous fever. Yet, despite his deteriorating condition, he worked right up to his death. He was even preparing sketches for new projects just before he passed away.

How Old Was Michelangelo When He Died?

The renowned sculptor and artist, Michelangelo Buonarroti, was 88 years of age when he eventually passed away. He died on the 18th of February 1564, following a prolonged illness that affected his kidneys and a serious fever. He was an active artist even in the final years of his life.

What Did Michelangelo Study?

From a young age, Michelangelo apprenticed under a series of various artists, such as Domenico Ghirlandaio, whom he first worked under when he was 13 years of age. He also took it upon himself to learn about human anatomy by dissecting corpses. He also studied humanities for a while at the De Medici Academy in Florence.

Was Michelangelo Married to Anyone?

No, Michelangelo Buonarroti is not known to have married anyone throughout his life, and it is not even known if he ever had any romantic relationships. There were many rumors that he was actually gay, much of which could be backed up by his own writings, which were apparently very homo-erotic in nature. Yet, his main love was his art, and this is where all of his attention and devotion went to. However, we do know that he enjoyed the company of close friends, several of whom he was particularly fond of and confided in.

Where Did Michelangelo Live?

Michelangelo Buonarroti first grew up in Caprese in Florence, near Tuscany. Many of his famous works were created while living in Florence, such as David . He also spent a considerable amount of time in Rome, living and working on various projects such as the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo would continue to move depending on where he was commissioned to go, or sometimes based on political events where he no longer felt safe to stay where he was. He spent a fair amount of time in Venice, working on the Virgin Mary and Child sculpture. Several years were also spent in Bologna working on St. Dominic’s tomb, and he also spent time selecting marble for his sculptures in places such as Carrara.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20 th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Michelangelo Buonarroti – A Detailed Michelangelo Biography.” Art in Context. June 1, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/michelangelo-buonarroti/

Meyer, I. (2023, 1 June). Michelangelo Buonarroti – A Detailed Michelangelo Biography. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/michelangelo-buonarroti/

Meyer, Isabella. “Michelangelo Buonarroti – A Detailed Michelangelo Biography.” Art in Context , June 1, 2023. https://artincontext.org/michelangelo-buonarroti/ .

Similar Posts

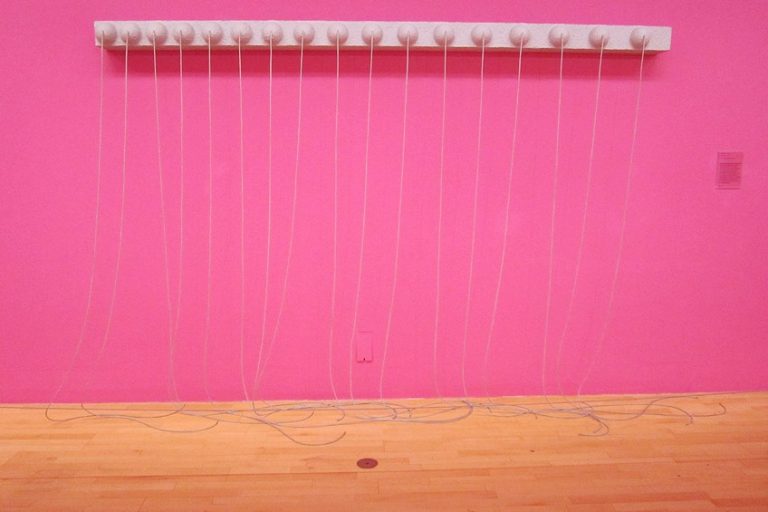

Eva Hesse – The Sculptor Who Brought Life to Minimalism

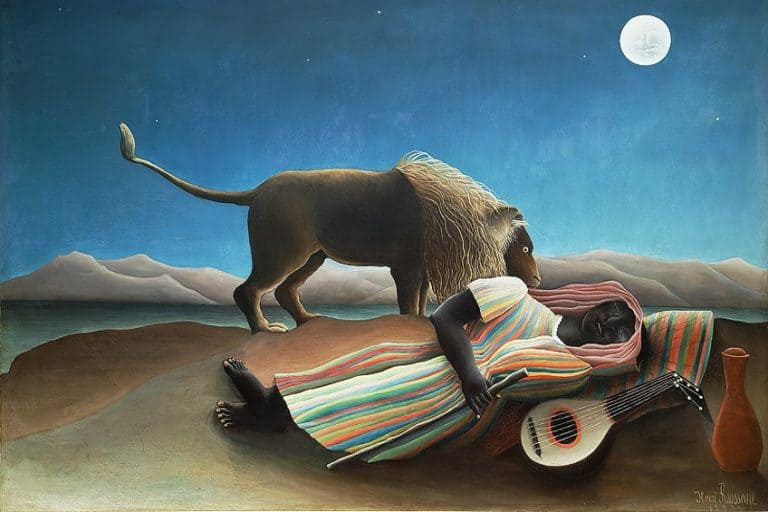

Henri Rousseau – A Look at the Life of the Tropical Paintings Artist

Winslow Homer – The Life and Paintings of the Famous Watercolor Artist

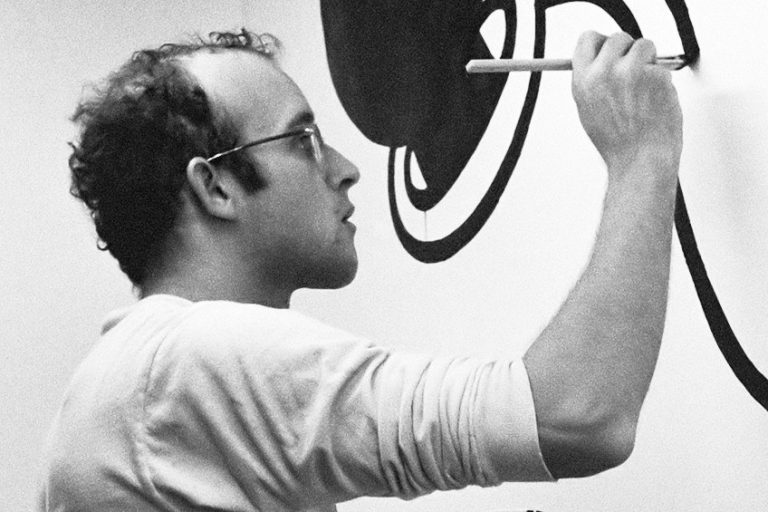

Keith Haring – An Introduction to Keith Haring’s Biography and Art

Wangechi Mutu – Explore the Work of the Afrofuturist Sculptor

Barbara Hepworth – Grande Dame of Modern British Sculpture

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Most Famous Artists and Artworks

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors…in all of history!

MOST FAMOUS ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors!

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Michelangelo

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 6, 2019 | Original: October 18, 2010

Michelangelo was a sculptor, painter and architect widely considered to be one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance—and arguably of all time. His work demonstrated a blend of psychological insight, physical realism and intensity never before seen. His contemporaries recognized his extraordinary talent, and Michelangelo received commissions from some of the most wealthy and powerful men of his day, including popes and others affiliated with the Catholic Church. His resulting work, most notably his Pietà and David sculptures and his Sistine Chapel paintings, has been carefully tended and preserved, ensuring that future generations would be able to view and appreciate Michelangelo’s genius.

Early Life and Training

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni) was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Italy. His father worked for the Florentine government, and shortly after his birth his family returned to Florence, the city Michelangelo would always consider his true home.

Did you know? Michelangelo received the commission to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling as a consolation prize of sorts when Pope Julius II temporarily scaled back plans for a massive sculpted memorial to himself that Michelangelo was to complete.

Florence during the Italian Renaissance period was a vibrant arts center, an opportune locale for Michelangelo’s innate talents to develop and flourish. His mother died when he was 6, and initially his father initially did not approve of his son’s interest in art as a career.

At 13, Michelangelo was apprenticed to painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, particularly known for his murals. A year later, his talent drew the attention of Florence’s leading citizen and art patron, Lorenzo de’ Medici , who enjoyed the intellectual stimulation of being surrounded by the city’s most literate, poetic and talented men. He extended an invitation to Michelangelo to reside in a room of his palatial home.

Michelangelo learned from and was inspired by the scholars and writers in Lorenzo’s intellectual circle, and his later work would forever be informed by what he learned about philosophy and politics in those years. While staying in the Medici home, he also refined his technique under the tutelage of Bertoldo di Giovanni, keeper of Lorenzo’s collection of ancient Roman sculptures and a noted sculptor himself. Although Michelangelo expressed his genius in many media, he would always consider himself a sculptor first.

Sculptures: The Pieta and David

Michelangelo was working in Rome by 1498 when he received a career-making commission from the visiting French cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas, envoy of King Charles VIII to the pope. The cardinal wanted to create a substantial statue depicting a draped Virgin Mary with her dead son resting in her arms—a Pieta—to grace his own future tomb. Michelangelo’s delicate 69-inch-tall masterpiece featuring two intricate figures carved from one block of marble continues to draw legions of visitors to St. Peter’s Basilica more than 500 years after its completion.

Michelangelo returned to Florence and in 1501 was contracted to create, again from marble, a huge male figure to enhance the city’s famous Duomo, officially the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. He chose to depict the young David from the Old Testament of the Bible as heroic, energetic, powerful and spiritual and literally larger than life at 17 feet tall. The sculpture, considered by scholars to be nearly technically perfect, remains in Florence at the Galleria dell’Accademia , where it is a world-renowned symbol of the city and its artistic heritage.

Paintings: Sistine Chapel

In 1505, Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to sculpt a grand tomb with 40 life-size statues, and the artist began work. But the pope’s priorities shifted away from the project as he became embroiled in military disputes and his funds became scarce, and a displeased Michelangelo left Rome (although he continued to work on the tomb, off and on, for decades).

However, in 1508, Julius called Michelangelo back to Rome for a less expensive, but still ambitious painting project: to depict the 12 apostles on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel , a most sacred part of the Vatican where new popes are elected and inaugurated.

Instead, over the course of the four-year project, Michelangelo painted 12 figures—seven prophets and five sibyls (female prophets of myth)—around the border of the ceiling and filled the central space with scenes from Genesis.

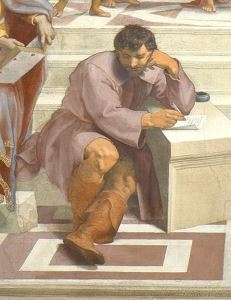

Critics suggest that the way Michelangelo depicts the prophet Ezekiel—as strong yet stressed, determined yet unsure—is symbolic of Michelangelo’s sensitivity to the intrinsic complexity of the human condition. The most famous Sistine Chapel ceiling painting is the emotion-infused The Creation of Adam, in which God and Adam outstretch their hands to one another.

Architecture & Poems

The quintessential Renaissance man, Michelangelo continued to sculpt and paint until his death, although he increasingly worked on architectural projects as he aged: His work from 1520 to 1527 on the interior of the Medici Chapel in Florence included wall designs, windows and cornices that were unusual in their design and introduced startling variations on classical forms.

Michelangelo also designed the iconic dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (although its completion came after his death). Among his other masterpieces are Moses (sculpture, completed 1515); The Last Judgment (painting, completed 1534); and Day, Night, Dawn and Dusk (sculptures, all completed by 1533).

Later Years

From the 1530s on, Michelangelo wrote poems; about 300 survive. Many incorporate the philosophy of Neo-Platonism—that a human soul, powered by love and ecstasy, can reunite with an almighty God—ideas that had been the subject of intense discussion while he was an adolescent living in Lorenzo de’ Medici’s household.

After he left Florence permanently in 1534 for Rome, Michelangelo also wrote many lyrical letters to his family members who remained there. The theme of many was his strong attachment to various young men, especially aristocrat Tommaso Cavalieri. Scholars debate whether this was more an expression of homosexuality or a bittersweet longing by the unmarried, childless, aging Michelangelo for a father-son relationship.

Michelangelo died at age 88 after a short illness in 1564, surviving far past the usual life expectancy of the era. A pieta he had begun sculpting in the late 1540s, intended for his own tomb, remained unfinished but is on display at the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence—not very far from where Michelangelo is buried, at the Basilica di Santa Croce .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Michelangelo

Italian Painter, Sculptor, Poet, and Architect

Summary of Michelangelo

It is universally accepted that Michelangelo is one of the greatest artists in the history of art. His phenomenal virtuosity as a sculptor, and also as a painter and architect, is married to a reputation for being hot-tempered and volatile. He was central to the revival in classical Greek and Roman art , but his contribution to Renaissance art and culture went far beyond the mere imitation of antiquity. Indeed, he conjured figures, both carved and painted, that were infused with such psychological intensity and emotional realism they set a new standard of excellence. Michelangelo's most seminal pieces: the massive painting of the biblical narratives on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the 17-foot-tall and anatomically flawless David, and the heartbreakingly genuine Pietà, are considered some of the greatest achievements in human history. Tourists flock to Rome and Florence to stand before them.

Accomplishments

- Michelangelo's early studies of classical sculpture were coupled with research into human cadavers. Having been granted access to a local hospital, he gained an almost surgical understanding of human anatomy. The resultant musculature of his figures is so naturalistic and precise they have been expected to spring to life at any moment.

- Michelangelo's dexterity with carving an entire sculpture from a single block of marble remains unmatched. He once said, "I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free." He was known as the sculptor who could summon the living from stone.

- The fact that he considered himself first and foremost a sculptor, didn't stop Michelangelo from producing what is perhaps the most famous fresco in the history of world art. Featuring scenes from the Old Testament, his sublime achievement, which adorns the ceiling of the Vatican's holy Sistine Chapel, attracts millions of visitors to Rome each year. The task of painting the ceiling is at the heart of Michelangelo's legend. It is the tale of a disgruntled artist working for four years, in uncomfortable and cramped conditions atop a scaffold structure, on a commission that he never wanted.

- Michelangelo is one of the greatest artists in history and was the first to have had his biography published while still working. The great Renaissance biographer, Giorgio Vasari, confirmed Michelangelo’s genius in his legendary book, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550).

- The artist's feisty and tempestuous personality is legendary. He often abandoned projects midway through or expressed his defiance through controversial means such as painting his own face on figures, or by putting in the faces of his enemies (in mocking fashion). One infamous attack was aimed at a high-ranking Vatican priest, Biagio de Cesena, who had complained about the level nudity in Michelangelo's Last Judgment fresco. In an act of revenge, the artist painted Minos (judge of the dead in Greek mythology) with Cesena's face, giving him donkeys ears, and with his testicles being bitten by a serpent.

The Life of Michelangelo

"The sculptor's hand can only break the spell to free the figures slumbering in the stone," Michelangelo famously said. Carved from a single block of marble, each figure he sculpted came alive with physical and psychological power, making him the most famous sculptor in history.

Important Art by Michelangelo

Bacchus , Michelangelo's first surviving large statue, depicts the Roman god of wine precariously balancing on a rock in a state of intoxication. He wears a wreath of ivy and holds a goblet in one hand, raised up toward his lips. In the other hand, he holds a lion skin, which is a symbol of death as derived from the myth of Hercules. From behind his left leg peeks a satyr, significant to the cult of Bacchus as often representing a drunken, lusty, woodland deity. The art historian Creighton E. Gilbert writes, "The Bacchus relies on ancient Roman nude figures as a point of departure, but it is much more mobile and more complex in outline. The conscious instability evokes the god of wine and Dionysian [relating to the sensuous and the orgiastic] revels with extraordinary virtuosity. Made for a garden, it is also unique among Michelangelo's works in calling for observation from all sides rather than primarily from the front." The work caused considerable controversy when it was unveiled. It was originally commissioned by Cardinal Riario and was inspired by a description of a lost bronze sculpture by the ancient sculptor Praxiteles. But when Riario saw the finished piece he found it inappropriate and rejected it. Michelangelo duly sold it to his banker, Jacopo Galli. Despite its checkered past, the piece is early evidence of Michelangelo's genius. His excellent knowledge of anatomy is seen in the androgynous figure's body which biographer Giorgio Vasari described as having the "the slenderness of a young man and the fleshy roundness of a woman." A high center of gravity lends the figure a sense of captured movement, which Michelangelo would later perfect for David . Although intended to mimic classical Greek sculpture Michelangelo remained true to what it means to be drunk; the unseemly swaying body was unlike any depiction of a god previously. Art historian Claire McCoy said of the sculpture, "Bacchus marked a moment when originality and imitation of the antique came together."

Marble - National Museum of Bargello, Florence

This was the first of a number of Pietàs Michelangelo worked on during his lifetime. It depicts the body of Jesus in the lap of his mother after the Crucifixion. This particular scene is one of the seven sorrows of Mary used in Catholic devotional prayers and depicts a key moment in her life foretold by the prophet, Simeon. Cardinal Jean de Bilhères commissioned the work, stating that he wanted to acquire the most beautiful work of marble in Rome, one that no living artist could better. The 24-year-old Michelangelo answered his call, carving the work in two years out of a single block of marble. Although the work continued a long tradition of devotional images, stretching back to 14 th century Germany, the depiction was unique to Italian Renaissance art of the time. Many artists were translating traditional religious narratives in a more humanist vein, blurring the boundaries between the divine and man by humanizing biblical figures and by taking liberties with expression. Mary was a popular subject, portrayed in myriad ways, and in this piece Michelangelo presented her, not as a mother in her fifties, but as a figure of youthful beauty. As Michelangelo related to his biographer Ascanio Condivi, "Do you not know that chaste women stay fresh much more than those who are not chaste?" Not only was Pietà the first interpretation of the scene in marble, but Michelangelo also moved away from the depiction of the Virgin's suffering which was usually portrayed in Pietàs of the time, presenting her instead with a profound sense of maternal tenderness. Christ too, shows little sign of his recent crucifixion with only slightly discernible nail marks in his hands and through the small wound in his side. Rather than a dead man, he looks as if he is sleeping in the arms of his mother while she waits for her son to awaken. A pyramidal structure, signature to the time, was also adopted here: Mary's head at the top and then the gradual widening through her layered garments towards the base. The folds of the draped clothing give credence to Michelangelo's mastery of marble, as they retain a sense of flowing movement, and an incredible standard of polished sheen, that is so difficult to achieve in stone. This is the only sculpture Michelangelo ever signed. In a fiery fit of reaction to rumors circulating that the piece was made by one of his competitors, Cristoforo Solari, he carved his name across Mary's sash right between her breasts. He also split his name in two as Michael Angelus, which can be seen as a reference to the Archangel Michael - an egotistical move and one he would later regret. He swore to never again sign another piece and stayed true to his word. This Pietà became famous immediately following its completion and was pivotal in contributing to Michelangelo's fame. The sculpture was loaned to the 1964 World's Fair in New York City. It was transported there by sea in a 2.5 ton buoyant and waterproof plexiglass case that contained a radio transmitter (so, should the ship sink, the sculpture could still be located and recovered). Despite an attack in 1972 (by a mentally unstable Hungarian-Austrian geologist, who cried out "I am Jesus Christ, risen from the dead!") which damaged Mary's arm and face, it was restored, placed behind a bulletproof crystal wall, and continues to inspire awe in visitors to this day.

Marble - Vatican City

The sculptor Donatello had revived the classical nude by sculpting a bronze version of David (1440-60). It would become a masterpiece of the Early Renaissance. But Michelangelo's towering marble figure overtook it as the most accomplished and iconic version of the story in the history of Western art. Michelangelo's majestic 17-foot-tall statue depicts the prophet David, with the slingshot he will use to slay Goliath, slung over his left shoulder. Michelangelo took the unusual decision to depict David before battle (in contrast, Donatello's triumphant David stands with his foot on top of his enemy's severed head). In fact, David's great foe (Goliath) is not referenced in the work at all. Michelangelo was commissioned to produce the sculpture for the Opera del Duomo at the Cathedral of Florence. It was to be one of a series of statues to be placed in the niches of the cathedral's tribunes (some 80 meters above ground). He was asked by the consuls of the Board to complete a project, abandoned previously by Agostino di Duccio and Antonio Rossellino, both of whom had rejected the enormous block of marble due to the presence of too many " taroli " (imperfections). The block of marble had stood idle in the Opera's courtyard for some 25 years. In his oft-cited biography, Ascanio Convidi wrote that it was known (from archive documents) that Michelangelo worked on David "in utmost secrecy, hiding his masterpiece in the making up until January 1504". He added that "since he worked in the open courtyard, when it rained he worked soaked" but, that rather than let the rain disturb him, it inspired Michelangelo's working method in which he created a wax model (of David ) and submerged it in water. As he worked, he would lower the level of the water, revealing the wax figure bit-by-bit. As Convidi explains, "using different chisels [he then] sculpted what he could see emerging". So engrossed was he in the project, Michelangelo is said to have "slept sporadically, and when he did he slept with his clothes and even in his boots still on, and rarely ate". The finished work is an exquisite example of Michelangelo's mastery of anatomy. This is most evident in David's musculature; his strength emphasized through the classical contrapposto (asymmetrical) stance, with weight shifting onto his right leg. The top half of the body was made slightly larger than the legs so that viewers glancing up at David from below, or from afar, would experience a more realistic perspective. Such was the figure's authenticity, Vasari proclaimed: "without any doubt this figure has put in the shade every other statue, ancient or modern, Greek or Roman." While the statue was widely revered, it was also reviled for its sexual explicitness. For instance, during the late nineteenth century, a plaster cast of David was exhibited at London's Victoria and Albert Museum. So as not to offend the tastes of noble women, Queen Victoria ordered that a "detachable" plaster fig leaf be added to the figure to protect David's modesty. On another occasion, a replica of David was offered to the municipality of Jerusalem to mark the 3,000th anniversary of King David's conquest of the city. Religious factions in Jerusalem urged that the gift be declined because the naked figure was considered pornographic. A fully clothed replica of David by Andrea del Verrocchio, a Florentine contemporary of Michelangelo, was accepted in its place.

Marble - Gallery of the Academy of Florence

Doni Tondo (Holy Family)

Holy Family , the only finished panel painting by the artist to survive, was commissioned by Agnolo Doni (which gives it its name) to commemorate his marriage to Maddalena Strozzi, daughter of a powerful Tuscan family. The inclusion of the infant St. John further suggests it was intended for mark the news of Maddalena's pregnancy (the couple's first child, Maria, was born in 1507). Moreover, botanists have identified the plant on the left as a clitoria plant that, like Mary's braid, was a symbol of fertility. The painting portrays Jesus, Mary, Joseph, and an infant John the Baptist. The intimate tenderness of the figures governed by the father's loving gaze emphasizes the love of family and divine love, representing the cores of Christian faith. In contrast, the five nude males in the background symbolize pagans awaiting redemption. The round (tondo) form was customary for private commissions and Michelangelo designed the intricate gold carved wooden frame. The work is believed to be entirely by his hand. We find many of the artist's influences in this painting, including Signorelli's Madonna . It is also said to have been influenced by Leonardo's The Virgin and Child with St. Anne , a full scale drawing that Michelangelo saw while working on his David in 1501. The nude figures in the background are thought to have been influenced by the ancient statue of Laocoön and His Sons attributed to the Greek sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus, which was excavated in Rome in 1506 and publicly displayed in the Vatican. Yet these influences aside, the piece is an example of the artist's individualism, which was even considered avant-garde in its time. The painting represented a significant shift from the serene, static rendition of figures depicted in classical Roman and Greek sculpture. Michelangelo's twisting figures signify great energy and movement, and the vibrant colors add to the majesty of the work, which were later used in his frescos in the Sistine Chapel. The soft modeling of the figures in the background with the focused details in the foreground gives this small painting its great depth. This painting might be said to anticipate the Mannerist style which, in contrast to the High Renaissance commitment to proportion and idealized beauty, showed a preference for exaggeration and affectation over naturalism.

Oil and tempera - The Uffizi Gallery, Florence

The Creation of Adam

This legendary image, part of the vast masterpiece that adorns the ceiling of the Vatican City's Sistine Chapel, shows Adam as a muscular classical nude, reclining on the left, as he extends his hand toward God who fills the right half of the painting. God rushes toward him, his haste conveyed by his white flaring robe and the energetic movements of his body. God is surrounded by angels and cherubim, all encased within a red cloud, while a feminine figure, thought to be Eve (first woman) or Sophia (symbol of wisdom), peers out with curious interest from underneath God's arm. Behind Adam, the green ledge upon which he lies, and the mountainous background create a strong diagonal, emphasizing the division between mortal man and heavenly God. As a result the viewer's eye is drawn to the hands of God and Adam, outlined in the central space, almost touching. Some have noted that the shape of the red cloud resembles the shape of the human brain, as if the artist meant to imply God's intent to infuse Adam with not merely animate life, but also the important gift of consciousness. This was an innovative depiction of the creation of Adam. Contrary to traditional artworks, God is not shown as aloof and regal, separate and above mortal man. For Michelangelo, it was important to depict the all-powerful giver of life as one distinctly intimate with man, whom he created in his own image. This reflected the humanist ideals of man's essential place in the world and the connection to the divine. The bodies have a sculptural quality that replicate the mastery of the artist's command of human anatomy. While acknowledging that Michelangelo painted the ceiling alone, laying on scaffolding on his back, and looking upward, the famous art historian E H Gombrich wrote that this feat of physical endurance was "nothing compared to the intellectual and artistic achievement. The wealth of ever-new [Renaissance] inventions, the unfailing mastery of execution in every detail, and, above all, the grandeur of the vision which Michelangelo revealed to those who came after him, have given mankind a quite new idea of the power of genius." The idea that Michelangelo was less than happy about the commission was confirmed through correspondences in 1509 to his friend Giovanni da Pistoia. He wrote, "I've already grown a goiter from this torture, [my] stomach's squashed under my chin, [my] face makes a fine floor for droppings, [my] skin hangs loose below me, [and my] spine's all knotted from folding myself over". He concluded, "I am not in the right place - I am not a painter."

Fresco - Vatican City

Michelangelo's monumental (eight-feet tall) statue depicts Moses seated regally as he shields the tablets on which the Ten Commandments are written. His expression is stern, reflecting his power and his displeasure at seeing the Israelites worshipping the golden calf (a pagan idol) on his return from Mount Sinai. Not only has Michelangelo rendered the great prophet with a complex emotional expression, strong muscular definition, and a flowing beard, his work on the deep folds of the fabric of Moses's clothes carries exquisite detail that completes its authenticity. Indeed, Michelangelo has imbued his Moses with a sense of energy that is remarkable for a stone figure, let alone one which who is seated. Michelangelo's reputation had reached new heights with his sculpture, David . This led to an invitation from Pope Julius II to come to Rome to work on a planned tomb. The artist initially proposed an (over) ambitious project featuring some 40 figures (the central piece being Moses). Much to the infuriation of the artist, however, Pope Julius II suspended work on the tomb so that he could paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (with the scaled-down tomb only completed in 1545 (32 years after Julius's death) and installed in San Pietro in Vincoli rather than the St. Peter's Basilica as originally planned). The sculpture has been the subject of much analysis, especially with regard to the horns protruding from Moses's head. In medieval art, Moses was often depicted with horns, and this was generally considered a symbol of the "glorification" of his power. This reading stems in fact from a mistranslation of the Hebrew word, karan which means "shining" or "emitting rays". Karan was translated into the Latin Bible as "horn", with the relevant passage reading thus: "And when Moses came down from the Mount Sinai, he held the two tables of the testimony, and he knew not that his face was horned from the conversation of the Lord." Legend tells that Michelangelo felt that Moses was his most life-like work and upon its completion he struck its knee, commanding "Now, speak!" The artist's pride in his achievement was fully warranted according to Vasari, who said of Moses that it was "a statue unrivaled by any contemporary or ancient achievement," adding that Moses's "long, lustrous beard, the strands of which are so silky and feathery that it appears as if the metal chisel has turned into a brush. The lovely face, like that of a prophet or a strong prince, seemed to require a veil to cover it, so magnificent and radiant is it, and so beautifully has the artist depicted in marble the purity with which he had bestowed that holy visage."

Marble - San Pietro Vincoli, Rome

The Last Judgment

This fresco covers the entire altar wall of the Sistine Chapel and is one of the last pieces to be made in the seminal building, and the first commissioned by Pope Paul III. Painted when Michelangelo was 62, we see the Second Coming of Christ as he delivers the message of salvation (through the Last Judgment). The monumental work took five years to complete and consists of over 300 individual figures. The scene is one of harried action around the central presence of Christ, his hands raised to reveal the wounds of his Crucifixion, as he looks down upon the souls of humans as they rise to their fates. With this arresting tableau, Paul III was seeking to counter the Protestant Reformation by reaffirming the orthodoxies and doctrines of the Catholic Church, and the visual arts were to play a vital role in his plans. To Christ's left, the Virgin Mary glances toward the saved. To either side of Christ are John the Baptist and St Peter holding the keys to heaven. On the right, Charon the ferryman is shown bringing the damned to the gates of Hell. Minos (ruler of Crete in Greek mythology), assuming the role Dante gave him in his Inferno , admits them to Hell. Another noteworthy group are the seven angels blowing trumpets illustrating the Book of Revelation's end of the world. Michelangelo's self-portrait appears twice in the painting, meanwhile, first in the flayed skin which the figure of St. Bartholomew is carrying in his left-hand, and second in the figure in the lower left-hand corner, who is looking at the saved souls rising up from their graves. In typical Michelangelo fashion, the artist courted controversy, chiefly by rendering nude figures with pronounced muscular anatomies. One of the myths surrounding the fresco relates to the priest, and high-ranking Vatican official, Biagio de Cesena, whom Michelangelo portrayed as Minos following his public criticism of the (unfinished) painting. Cesena had complained that the painting contained so much nudity it was "more fitting for a tavern that the Sistine Chapel". Vasari reports that "Michelangelo, angry at the remark, is said to have painted Cesena's face onto Minos, judge of the underworld, with donkey's ears. Cesena complained to the Pope at being so ridiculed, but the Pope is said to have jokingly remarked that his jurisdiction did not extend to Hell." Following a recent cleaning of the fresco, moreover, it has been revealed that Minos's testicles are being attacked by a serpent. Interestingly, theologian John O'Malley, notes that in 1563 the Council of Trent pronounced that "iconoclasm is wrong" and that "images of sacred subjects […] should not contain any - sensual appeal or - seductive charm." Following the Council’s judgement, it was decreed that "The pictures in the Apostolic Chapel are to be covered..." On January 21, 1564, less than a month before Michelangelo's death, the decree was formally applied to The Last Judgment . So, next year, Michelangelo's friend, Daniele da Volterra, was commissioned to add clothing to the nude figures (earning Volterra the nickname "breeches-maker"). (O'Malley observes that "there is no instance of any other painting in Rome being defaced as a result of [the decree].") The Last Judgment was only restored to its original glory in the 1990s.

The Deposition

This piece is not only sculpturally complex, but it carries layers of meaning and has sparked multiple interpretations. In it, we see Christ the moment after the Deposition, or being taken down from the cross of his crucifixion. He is falling into the arms of his mother, the Virgin Mary, and Mary Magdalene, whose presence in a work of such importance was highly unusual. Behind the trio is a hooded figure, which is said to be either Joseph of Arimathea or Nicodemus, both of whom were in attendance at the entombment of Christ (which followed the Deposition). Joseph would give up his tomb for Christ and Nicodemus would speak with Christ about the possibility of obtaining eternal life. Because Christ is seen falling into the arms of his mother, this piece is also often referred to as a Pietà. The three themes alluded to in this one piece - The Deposition, The Pietà, and The Entombment - are further emphasized by the way Michelangelo carved out his narrative. Not only is it intense in its realism, The Deposition was sculpted so that a viewer could walk around the piece and observe each of the three narratives from different visual perspectives and to possibly reflect upon how the stories might be interrelated. The sculpture is also a perfect example of Michelangelo's temperament and perfectionism. The process of making it was arduous. Vasari relates that the artist complained about the quality of the marble. Some suggest he had a problem with the way Christ's left leg originally draped over Nicodemus, worrying that some might interpret it in a sexual way, causing him to remove it. It is also feasible that Michelangelo was so particular with the piece because he intended it for his own future tomb. In 1555, Michelangelo attempted to destroy the piece causing further speculation about its meaning. There is a suggestion that the attempted destruction of the piece was because Nicodemus, by reference to his conversation with Christ about the need to be born again to find everlasting life, is associated with Martin Luther's Reformation. Michelangelo was rumored to be a secret sympathizer, which was dangerous even for someone as influential as he. Perhaps a coincidence, but his Lutheran sympathies are given as one of the reasons why Pope Paul IV cancelled Michelangelo's pension in 1555. Vasari also suggests that the face of Nicodemus is a self-portrait, which may allude to the artist's crisis of faith. Michelangelo gave the unfinished piece to Francesco Bandini, a wealthy merchant, who commissioned Tiberio Calcagni, a friend of Michelangelo's, to finish the work and repair the damage (but stopping short of replacing Christ's left leg).

Marble - Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence

Pietà Rondanini

Pietà Rondanini is the last sculpture Michelangelo worked on in the weeks leading up to his death, finalizing a story that weaved through his many Pietàs and now reflective of the artist's reckoning with his own mortality. The depiction of Christ has changed from his earlier St. Peter's Pietà in which Christ appeared asleep, through to his Deposition, where Christ's body was more lifeless, to now, where Christ is shown in the pain and suffering of death. His mother Mary is standing in this piece, an unusual rendition, as she struggles to hold up the body of her son while engulfed with grief. What's interesting about this work is that Michelangelo abandoned his usual detail at carving the body, even though he worked on it intermittently for some 12 years. It was a departure that, coming so late in his prolific career, signified the enduring genius of an artist whose confidence would allow him to try new things even when his fame would have allowed him to rest upon his laurels. The detached arm, the subtle sketched features of the face, and the way the figures almost blend into one other provide a more abstracted quality than was his norm, and prefigures a minimalist quality that was yet to come in sculpture. The renowned sculptor Henry Moore later said of this piece, "This is the kind of quality you get in the work of old men who are really great. They can simplify, they can leave out... This Pietà is by someone who knows the whole thing so well he can use a chisel like someone else would use a pen." This sculpture's importance was ignored for centuries, and it almost entirely disappeared from public discourse until it was found in the possession of Marchese Rondanini in 1807. It has since excited many modern artists. The Italian artist Massimo Lippi is quoted as saying that modern and contemporary art began with this Pietà , and the South African painter, Marlene Dumas, based her Homage to Michelangelo (2012) on this work.

Marble - Museo d'arte antica, Sforza Castle, Milan

Biography of Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, was born to Leonardo di Buonarrota and Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena, a middle-class family of bankers, living in the small village of Caprese (now known in his honor as Michelangelo Caprese), near Arezzo, Tuscany. His mother's unfortunate and prolonged illness, which led to her death while Michelangelo was just six years old, forced his father to place his son in the primary care of his nanny. The nanny was married to a stonecutter and legend tells it that this (forced) domestic situation would form the foundation for the artist's lifelong love affair with marble.

By the time he was 13 years old, it was clear to his father that Michelangelo had no aptitude for the family vocation. The young boy was sent to apprentice in the well-known Florentine studio of Domenico Ghirlandaio . The art historian E.H. Gombrich writes, "In his workshop the young Michelangelo could certainly learn all the technical tricks of the trade, a solid technique in painting frescoes, and thorough grounding in draftsmanship. But, as far as we know, Michelangelo did not enjoy his days in the painter's firm. His ideas about art were different. Instead of acquiring the facile manner of Ghirlandaio, he went out to study the work of the great masters of the past, Giotto , Masaccio , Donatello , and other Greek and Roman sculptors whose work he could see in the Medici collection".

After only a year in the studio, Lorenzo de' Medici, the de facto ruler of Florence, and renowned patron of the arts, asked Ghirlandaio to supply his two best students - Michelangelo and Francesco Granacci - to join the Medici's Humanist academy. It was a thriving time in Renaissance Florence when artists were encouraged to study the humanities, complementing their creative endeavors with knowledge of ancient Greek and Roman art and philosophy. Progressive artists were moving away from Gothic iconography and devotional work and evolving a Renaissance style that would foreground humanist ideals and celebrate man's primary role in shaping the modern world.

Michelangelo studied under the bronze sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni, bringing him exposure to the great classical sculptures in the palace of Lorenzo. But as Gombrich says, "Like Leonardo, [Michelangelo] was not content with learning the laws of anatomy secondhand, as it were, from antique sculpture. He made his own research into human anatomy, dissected bodies and drew from models, till the human figure did not hold any secrets for him." However, unlike Leonardo, for whom human anatomy was just one of the many "riddles of nature", Michelangelo "strove with an incredible singleness of purpose to master this one problem, but to master it fully."

During this period, Michelangelo obtained permission from the friars at the Church of Santo Spirito to study cadavers in the convent's hospital where he would gain a deep understanding of human anatomy. Michelangelo's uncanny ability to render the muscular tone of the body was evidenced in two surviving sculptures from the period: Madonna of the Stairs (1491), and Battle of the Centaurs (1492). The 17-year-old Michelangelo was given refuge at the convent following the death of his patron, Lorenzo di Medici (Lorenzo the Magnificent) in 1492. By way of a "thank-you", Michelangelo carved a highly realistic wooden sculpture which hung over the main altar. (After the French occupation in the late 18 th -century, the cross was recorded as lost but it had in fact been moved to another chapel where it was painted to disguise its origins. Once restored, it was on display at the museum of Casa Buonarroti, where it remained until 2000 before being returned to its original home at Santo Spirito.)

Early Training and Work

In 1494, as the Republic of Florence was under the threat of siege from the French. Michelangelo, fearing for his safety, moved, via a brief stop in Venice, to the relative safety of Bologna. In the city he was befriended by the wealthy Bolognese senator, Giovan Francesco Aldrovandi, who was able to secure the 19-year-old Michelangelo the commission to complete the remaining statuettes for the marble sarcophagus lid for the Arca of St. Dominic. The original lid, by Niccolò dell'Arca, was installed in 1473, with Michelangelo sculpting the few remaining figures, including Saint Proculus, Saint Petronio, and an angel with candelabra, in 1496. Still just 19 years old, Michelangelo overshadowed the work of the older sculptor through his fine detail in the folds of the cloth and drapery, and in the figure of Petronio to whom he brought a tangible sense of movement by representing him in mid-step.

Michelangelo returned briefly to Florence after the threat of the French invasion abated. He worked on two statues, one of St. John the Baptist , the other, a small cupid. The Cupid was sold to Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio, who had been duped into believing that it was an antique sculpture. Although angry on learning of the deception, Cardinal Riario was impressed by Michelangelo's skill and invited him to Rome to work on a new project. For this commission, Michelangelo created a statue of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, which was, on its completion, rejected by the Cardinal who thought it politically imprudent to be associated with a naked pagan figure. Michelangelo, who had already garnered a reputation for being volatile, was left incensed and many years later instructed his biographer, Condivi, to deny the commission came from the Cardinal at all, and to record it rather as a commission from his banker, Jacopo Galli (who had purchased the finished work).