- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

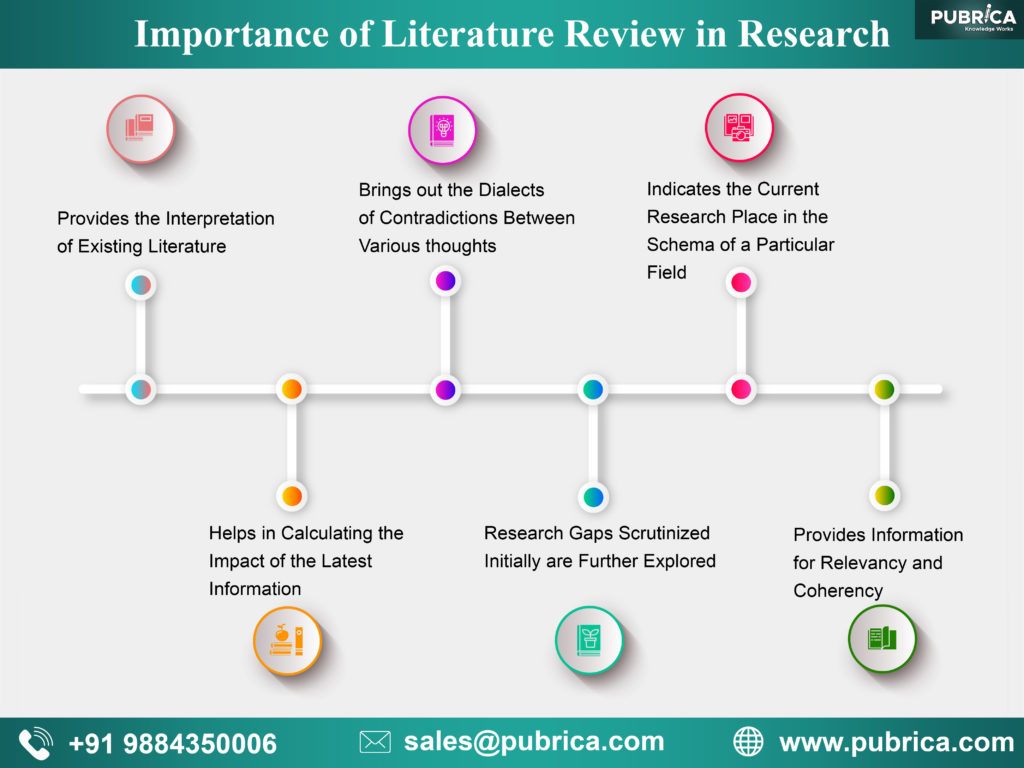

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 10:51 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 22 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Conducting a literature review: why do a literature review, why do a literature review.

- How To Find "The Literature"

- Found it -- Now What?

Besides the obvious reason for students -- because it is assigned! -- a literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

It Also Helps You:

- Publish and share your findings

- Justify requests for grants and other funding

- Identify best practices to inform practice

- Set wider context for a program evaluation

- Compile information to support community organizing

Great brief overview, from NCSU

Want To Know More?

- Next: How To Find "The Literature" >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 1:10 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/litreview

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 10:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

A Guide to Literature Reviews

Importance of a good literature review.

- Conducting the Literature Review

- Structure and Writing Style

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Citation Management Software This link opens in a new window

- Acknowledgements

A literature review is not only a summary of key sources, but has an organizational pattern which combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

- << Previous: Definition

- Next: Conducting the Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 22, 2024 3:26 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mcmaster.ca/litreview

- Research Process

Literature Review in Research Writing

- 4 minute read

- 422.7K views

Table of Contents

Research on research? If you find this idea rather peculiar, know that nowadays, with the huge amount of information produced daily all around the world, it is becoming more and more difficult to keep up to date with all of it. In addition to the sheer amount of research, there is also its origin. We are witnessing the economic and intellectual emergence of countries like China, Brazil, Turkey, and United Arab Emirates, for example, that are producing scholarly literature in their own languages. So, apart from the effort of gathering information, there must also be translators prepared to unify all of it in a single language to be the object of the literature survey. At Elsevier, our team of translators is ready to support researchers by delivering high-quality scientific translations , in several languages, to serve their research – no matter the topic.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a study – or, more accurately, a survey – involving scholarly material, with the aim to discuss published information about a specific topic or research question. Therefore, to write a literature review, it is compulsory that you are a real expert in the object of study. The results and findings will be published and made available to the public, namely scientists working in the same area of research.

How to Write a Literature Review

First of all, don’t forget that writing a literature review is a great responsibility. It’s a document that is expected to be highly reliable, especially concerning its sources and findings. You have to feel intellectually comfortable in the area of study and highly proficient in the target language; misconceptions and errors do not have a place in a document as important as a literature review. In fact, you might want to consider text editing services, like those offered at Elsevier, to make sure your literature is following the highest standards of text quality. You want to make sure your literature review is memorable by its novelty and quality rather than language errors.

Writing a literature review requires expertise but also organization. We cannot teach you about your topic of research, but we can provide a few steps to guide you through conducting a literature review:

- Choose your topic or research question: It should not be too comprehensive or too limited. You have to complete your task within a feasible time frame.

- Set the scope: Define boundaries concerning the number of sources, time frame to be covered, geographical area, etc.

- Decide which databases you will use for your searches: In order to search the best viable sources for your literature review, use highly regarded, comprehensive databases to get a big picture of the literature related to your topic.

- Search, search, and search: Now you’ll start to investigate the research on your topic. It’s critical that you keep track of all the sources. Start by looking at research abstracts in detail to see if their respective studies relate to or are useful for your own work. Next, search for bibliographies and references that can help you broaden your list of resources. Choose the most relevant literature and remember to keep notes of their bibliographic references to be used later on.

- Review all the literature, appraising carefully it’s content: After reading the study’s abstract, pay attention to the rest of the content of the articles you deem the “most relevant.” Identify methodologies, the most important questions they address, if they are well-designed and executed, and if they are cited enough, etc.

If it’s the first time you’ve published a literature review, note that it is important to follow a special structure. Just like in a thesis, for example, it is expected that you have an introduction – giving the general idea of the central topic and organizational pattern – a body – which contains the actual discussion of the sources – and finally the conclusion or recommendations – where you bring forward whatever you have drawn from the reviewed literature. The conclusion may even suggest there are no agreeable findings and that the discussion should be continued.

Why are literature reviews important?

Literature reviews constantly feed new research, that constantly feeds literature reviews…and we could go on and on. The fact is, one acts like a force over the other and this is what makes science, as a global discipline, constantly develop and evolve. As a scientist, writing a literature review can be very beneficial to your career, and set you apart from the expert elite in your field of interest. But it also can be an overwhelming task, so don’t hesitate in contacting Elsevier for text editing services, either for profound edition or just a last revision. We guarantee the very highest standards. You can also save time by letting us suggest and make the necessary amendments to your manuscript, so that it fits the structural pattern of a literature review. Who knows how many worldwide researchers you will impact with your next perfectly written literature review.

Know more: How to Find a Gap in Research .

Language Editing Services by Elsevier Author Services:

What is a Research Gap

- Manuscript Preparation

Types of Scientific Articles

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Topic Guide - Developing Your Research Study

- Purpose of Guide

- Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- APA 7th Edition

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

Importance of a Good Literature Review

Types of Literature Reviews

Structure and Writing Style

Writing tip, another writing tip, yet another writing tip.

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- 10. Proofreading Your Paper

- Writing Concisely

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Study

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory; thereby, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of the works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.

Some more thoroughly detailed sources to follow for developing a literature review would be Conducting Research Literature Reviews and/or Doing a Literature Review by Chris Hart — both of which are located in our Squires Library collection.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews : From the Internet to Paper . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1998.

Hart, Chris. Doing a literature review : releasing the social science research imagination London: SAGE, 2005

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in many disciplines, a literature review has an organizational pattern and combines both a summary and a synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, whereas a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Reveal conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research. This is often directly related to the gap(s) revealed .

- Locate your own research idea(s) / intent within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews : From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006 The Literature Review: Six Steps to Success . 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California : Corwin, 2016.

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.