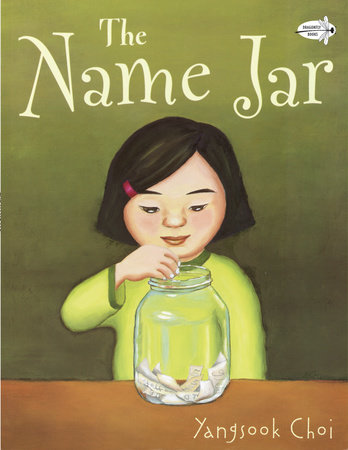

The Name Jar

Book module navigation, the name jar explores questions about difference, identity, and cultural assimilation..

When Unhei, a young Korean girl, moves to America with her family and arrives at a new school, she begins to wonder if she should also choose a new name. Her classmates suggest Daisy, Miranda, Lex, and more, but nothing seems to fit. Does she need an American name? How will she choose? And what should she do about her Korean name?

Read aloud video by Mrs. R.

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

Throughout The Name Jar , questions about difference and identity underlie Unhei’s consideration of taking an American name rather than using her given Korean name at school. Is it good to be different or bad to be different? How do we respond to difference? Is a name just another word, or it is something more? How closely is one’s identity connected to one’s name? What are the implications of changing one’s name?

If we adopt an attitude of celebrating difference, can we go so far as to say that difference is always good? While it certainly seems beneficial to recognize, value, and appreciate difference in general, it doesn’t necessarily seem reasonable to simply accept certain ideological differences which lead to great pain and suffering. What then should be done? For some, it is enough to identify and understand the reasons for the difference or to promote conversation across the difference, while others claim that steps should be taken to minimize the difference. The Name Jar asks many of these questions in the context of Unhei’s difference from her peers, particularly in the form of her name, and thus provides an opening for discussion of how it feels to be different and the ways in which we should respond to difference in others.

As for identity, the term is generally used in philosophy to refer to whatever it is that makes an entity recognizable as distinct from others, in this case the set of characteristics that distinguishes one person from another. The Name Jar particularly addresses social identity, the way in which individuals define themselves in relation to others. This issue is seen in the story as Unhei changes the way in which she introduces herself to others depending on prior reactions and on the context of that point in the story: from saying her real name on the bus to claiming that she does not yet have a name when she meets her new class, from telling Mr. Kim her real name to sharing her name choice with her class. What is it about each situation that influences this behavior and what can this tell us about social identity? Themes that might emerge here include ways in which one’s identity is shaped by family and culture and the role of peers, family, and society in supporting or denying the development of one’s identity.

More specifically, The Name Jar encourages a consideration of assimilation, particularly cultural assimilation, one example of which is often the changing of one’s name. What does the choice to change one’s name entail and what significance does it have? Arguments in favor of name change for cultural reasons include having an easily pronounceable name, showing acceptance of the new culture, and minimizing difference; while arguments against include maintaining cultural identity, keeping family history and lineage alive, and retaining connections. The Name Jar shows Unhei experiencing many of these conflicting pressures: wanting to fit in with her new classmates and not be teased for her Korean name yet retaining strong ties to this name through her family culture and name stamp. Discussing these issues begins to address the question of what connection people’s names have with their identity and whether or not this connection is the same for everybody or not.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

On the bus, none of the children are able to pronounce Unhei’s name.

- How do the other children respond when Unhei introduces herself on the bus? Why do they act this way? Do you think things would have been different if the children had been able to pronounce Unhei’s name? Why or why not?

- How does Unhei feel by the time the bus arrives at school? How can you tell?

- Have you ever had an experience like Unhei’s?

- Do you think that the children on the bus could have responded to Unhei’s name in a different way? What could they have done, and how would that have made a difference?

- What should we do when we have difficulty pronouncing other people’s names? Is it important that we say them correctly? Why or why not?

- How should we respond to people who are different than us? Why?

When her new class asks for her name, Unhei replies, “Um, I haven’t picked one yet.” When she goes home, she tells her mother, “I think I would like my own American name.”

- Why does Unhei choose not to share her name with her class? How does the class react?

- How does Unhei explain her wish for an American name to her mother? How does her mother respond? Do you agree with Unhei’s mother, that being different is a good thing? Why or why not?

- In what ways are you different from other people? Is each good or bad? Why?

- What do you think would be a good thing about Unhei having an American name? What would be bad? Why?

- What makes a name an American name? Why? What kind of name is your name?

The next day when Unhei arrives at school, she finds the name jar on her desk.

- Why does Unhei’s class create the name jar? What is it for?

- How does Unhei feel about the name jar? How can you tell?

- What are the differences between the ways that the children on the bus responded to Unhei and the ways that her class responds? Why do you think this is?

- What are some of reasons for the names that Unhei’s classmates suggest? Are these good reasons for picking names? Why or why not?

- How do Joey and the class support Unhei as she thinks about choosing a new name? Do you think that this was important? Why or why not?

- Do you think that the class cares which name Unhei chooses? Will it make a difference? Why or why not?

Unhei spends a lot of time thinking about a new name, during which time she visits Mr. Kim’s shop, shows Joey her name stamp, and receives a letter from her grandma.

- What do we learn about Unhei’s name when she visits Mr. Kim’s shop? Is this important? Why?

- Do all names have meaning? Why or why not? Where do those meanings come from?

- What does Unhei share with Joey? Why does she do this? How do you think Unhei is feeling about her name when she does this?

- How can somebody have a name that they can show you but not tell you? Can you think of any other names like that?

- What does her grandma’s letter make Unhei think about? How is Unhei’s name connected to her grandma? Is your name connected to your family? How?

- What is the purpose of names? Why do we have them? Does your name help to make you who you are? Why or why not?

After the weekend, Unhei is ready to introduce herself to the class. “‘I liked the beautiful names and funny names you thought of for me,’ she told the class. ‘But I realized that I liked my name best, so I chose it again.’”

- Why does Unhei choose her own name at the end? What were some of the experiences that helped her to decide this? Do you think this was the right choice? Why or why not?

- If you could choose your own name, would you choose the name you already have or would you pick a different one? Why?

- Could Unhei still have been Unhei if she had picked a different name? Why or why not?

- How does Unhei’s class respond when she tells them her name? Why is this important?

- How do you think Unhei felt about her name by the end of the story? Why?

- What can we say about names and their importance? Is a name just another word or is it something more? Why?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Sarah Hopson. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.

About the Prindle Institute

As one of the largest collegiate ethics institutes in the country, the Prindle Institute for Ethics’ uniquely robust national outreach mission serves DePauw students, faculty and staff; academics and scholars throughout the United States and in the international community; life-long learners; and the Greencastle community in a variety of ways. In 2019, the Prindle Institute partrnered with Thomas Wartenberg and became the digital home of his Teaching Children Philosophy discussion guides.

Further Resources

Some of the books on this site may contain characterizations or illustrations that are culturally insensitive or inaccurate. We encourage educators to visit the Association for Library Service to Children’s resource guide for talking to children about issues of race and culture in literature. They also have a guide for navigating tough conversations. PBS Kids’ set of resources for talking to young children about race and racism might also be useful for educators.

Philosophy often deals with big questions like the existence of a higher power or death. Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our resources page.

2961 W County Road 225 S Greencastle, IN 46135 P: (765) 658-4075

BUILDING HOURS

Monday - Friday: 8:00AM - 5:00PM Saturday-Sunday: closed

“The Name Jar” by Yangsook Choi

Being the new kid in school is hard enough, but what about when nobody can pronounce your name? Having just moved from Korea, Unhei is anxious that American kids will like her. So instead of introducing herself on the first day of school, she tells the class that she will choose a name by the following week. Her new classmates are fascinated by this no-name girl and decide to help out by filling a glass jar with names for her to pick from. But while Unhei practices being a Suzy, Laura, or Amanda, one of her classmates comes to her neighborhood and discovers her real name and its special meaning. On the day of her name choosing, the name jar has mysteriously disappeared. Encouraged by her new friends, Unhei chooses her own Korean name and helps everyone pronounce it—Yoon-Hey.

About The Author

Yangsook Choi grew up in Korea. She started drawing at age 4 and loved telling her grandma scary stories. After moving to New York to pursue her art, she has written and illustrated many books for young readers. Her books have been acclaimed as “Best of the Best” by the Chicago Public Library, included on the American Library Association Notable Books List, and have received the International Reading Association’s Children’s Book Award.

Read Aloud Tips

Give the students time to explore the illustrations and details. Encourage students to share their thoughts and feelings about how the pictures connect to the story.

Information about Korea and Korean culture are revealed throughout the story. Allow the students time to learn more.

Class activity suggestion: look up each child’s name in class to understand what they mean. This can be a time for students to appreciate the origin of their name like Unhei.

“A person’s name is a huge part of their identity. The students who enter our classrooms carry names that were chosen just for them. Please do your part to learn, honor, and respect their names (or nicknames). The Name Jar has a great message about identity, diversity, and self-acceptance.” – Amazon Review

Buy This Book

Information sheet – the name jar.

The Name Jar

Mar 18, 2017

Unhei from The Name Jar (2001), but Yangsook Choi. Fair use rationale.

Yangsook Choi wrote and illustrated The Name Jar in 2001. It relays the story of Unhei, a young girl from Korea whose family moved to America. On her first day of school, Unhei’s fellow classmates fail to pronounce her name. They continue to make fun of it, referring to her as “hey-you.” She decides to choose an American name so she could fit in. Her classmates give her a glass jar full of their suggestions. However, Unhei’s mother, grandmother and her new friend Joey all encourage her to be proud of who she is. Choi’s subtle references to Korean culture all serve to prove how unique and special the young girl’s heritage is. The character of Unhei goes on a journey and discovers the importance of her name. This results in her deciding to keep the name Unhei, and teach her fellow classmates about Korea and the Korean language.

The illustration shows Unhei surrounded by her classmates as she sits in front of her name jar. The children seem to be leering at her, portraying the part of the story where they ridicule Unhei’s name. Choi illustrates Unhei in a white jumper, sharply contrasting with the clothing of those surrounding her, and drawing in the eye of the reader. The white highlights the innocence of Unhei, and the brightness of her clothes emphasizes her uniqueness. It also acts as a blank canvas, waiting for her to make her decisions.

It is hard to separate Choi with this illustration because of the similarities between her and Unhei. Choi was also born in Korea and moved to New York to pursue her dream of art after being told that it would lead her nowhere. Therefore, the story of Unhei embodies the importance of children making their own decisions and being proud of their heritage.

Pin It on Pinterest

Authors & Events

Recommendations

- New & Noteworthy

- Bestsellers

- Popular Series

- The Must-Read Books of 2023

- Popular Books in Spanish

- Coming Soon

- Literary Fiction

- Mystery & Thriller

- Science Fiction

- Spanish Language Fiction

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Spanish Language Nonfiction

- Dark Star Trilogy

- Ramses the Damned

- Penguin Classics

- Award Winners

- The Parenting Book Guide

- Books to Read Before Bed

- Books for Middle Graders

- Trending Series

- Magic Tree House

- The Last Kids on Earth

- Planet Omar

- Beloved Characters

- The World of Eric Carle

- Llama Llama

- Junie B. Jones

- Peter Rabbit

- Board Books

- Picture Books

- Guided Reading Levels

- Middle Grade

- Activity Books

- Trending This Week

- Top Must-Read Romances

- Page-Turning Series To Start Now

- Books to Cope With Anxiety

- Short Reads

- Anti-Racist Resources

- Staff Picks

- Memoir & Fiction

- Features & Interviews

- Emma Brodie Interview

- James Ellroy Interview

- Nicola Yoon Interview

- Qian Julie Wang Interview

- Deepak Chopra Essay

- How Can I Get Published?

- For Book Clubs

- Reese's Book Club

- Oprah’s Book Club

- happy place " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: Happy Place

- the last white man " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: The Last White Man

- Authors & Events >

- Our Authors

- Michelle Obama

- Zadie Smith

- Emily Henry

- Amor Towles

- Colson Whitehead

- In Their Own Words

- Qian Julie Wang

- Patrick Radden Keefe

- Phoebe Robinson

- Emma Brodie

- Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Laura Hankin

- Recommendations >

- 21 Books To Help You Learn Something New

- The Books That Inspired "Saltburn"

- Insightful Therapy Books To Read This Year

- Historical Fiction With Female Protagonists

- Best Thrillers of All Time

- Manga and Graphic Novels

- happy place " data-category="recommendations" data-location="header">Start Reading Happy Place

- How to Make Reading a Habit with James Clear

- Why Reading Is Good for Your Health

- 10 Facts About Taylor Swift

- New Releases

- Memoirs Read by the Author

- Our Most Soothing Narrators

- Press Play for Inspiration

- Audiobooks You Just Can't Pause

- Listen With the Whole Family

Look Inside

The Name Jar

By yangsook choi illustrated by yangsook choi, by yangsook choi, by yangsook choi read by shannon tyo, category: children's picture books, category: children's books, category: children's books | audiobooks.

Oct 14, 2003 | ISBN 9780440417996 | 8-1/2 x 11 --> | 3-7 years | ISBN 9780440417996 --> Buy

Jul 10, 2001 | ISBN 9780375806131 | 8-1/2 x 11 --> | 5-8 years | ISBN 9780375806131 --> Buy

Oct 30, 2013 | ISBN 9780307793447 | 3-7 years | ISBN 9780307793447 --> Buy

Dec 06, 2022 | 19 Minutes | 5-8 years | ISBN 9780593682319 --> Buy

Buy from Other Retailers:

Oct 14, 2003 | ISBN 9780440417996 | 3-7 years

Jul 10, 2001 | ISBN 9780375806131 | 5-8 years

Oct 30, 2013 | ISBN 9780307793447 | 3-7 years

Dec 06, 2022 | ISBN 9780593682319 | 5-8 years

Buy the Audiobook Download:

- audiobooks.com

About The Name Jar

A heartwarming story about the new girl in school, and how she learns to appreciate her Korean name. Being the new kid in school is hard enough, but what happens when nobody can pronounce your name? Having just moved from Korea, Unhei is anxious about fitting in. So instead of introducing herself on the first day of school, she decides to choose an American name from a glass jar. But while Unhei thinks of being a Suzy, Laura, or Amanda, nothing feels right. With the help of a new friend, Unhei will learn that the best name is her own. From acclaimed creator Yangsook Choi comes the bestselling classic about finding the courage to be yourself and being proud of your background.

The new kid in school needs a new name! Or does she? Being the new kid in school is hard enough, but what about when nobody can pronounce your name? Having just moved from Korea, Unhei is anxious that American kids will like her. So instead of introducing herself on the first day of school, she tells the class that she will choose a name by the following week. Her new classmates are fascinated by this no-name girl and decide to help out by filling a glass jar with names for her to pick from. But while Unhei practices being a Suzy, Laura, or Amanda, one of her classmates comes to her neighborhood and discovers her real name and its special meaning. On the day of her name choosing, the name jar has mysteriously disappeared. Encouraged by her new friends, Unhei chooses her own Korean name and helps everyone pronounce it— Yoon-Hey .

Listen to a sample from The Name Jar

About yangsook choi.

Yangsook Choi grew up in Seoul, Korea.

Product Details

Category: children’s picture books, category: children’s books, category: children’s books | audiobooks, you may also like.

The Snail and the Whale

The Invisible Boy

Big Red Lollipop

All Are Welcome (An All Are Welcome Book)

Miss Bindergarten Gets Ready for Kindergarten

Are You Mad at Me?

I Am Smart, I Am Blessed, I Can Do Anything!

First Grade, Here I Come!

Of Thee I Sing

Sam and the Firefly

“Unhei’s reflection and inner strength are noteworthy; cultural details freshen the story, and Choi’s gleaming, expressive paintings are always a treasure.” — The New York Times

Arkansas Diamond Primary Book Master List WINNER 2003

Arizona Young Readers Award NOMINEE 2005

Visit other sites in the Penguin Random House Network

Raise kids who love to read

Today's Top Books

Want to know what people are actually reading right now?

An online magazine for today’s home cook

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

THE NAME JAR

by Yangsook Choi & illustrated by Yangsook Choi ‧ RELEASE DATE: July 10, 2001

Unhei has just left her Korean homeland and come to America with her parents. As she rides the school bus toward her first day of school, she remembers the farewell at the airport in Korea and examines the treasured gift her grandmother gave her: a small red pouch containing a wooden block on which Unhei’s name is carved. Unhei is ashamed when the children on the bus find her name difficult to pronounce and ridicule it. Lesson learned, she declines to tell her name to anyone else and instead offers, “Um, I haven’t picked one yet. But I’ll let you know next week.” Her classmates write suggested names on slips of paper and place them in a jar. One student, Joey, takes a particular liking to Unhei and sees the beauty in her special stamp. When the day arrives for Unhei to announce her chosen name, she discovers how much Joey has helped. Choi ( Earthquake , see below, etc.) draws from her own experience, interweaving several issues into this touching account and delicately addressing the challenges of assimilation. The paintings are done in creamy, earth-tone oils and augment the story nicely. (Picture book. 4-8)

Pub Date: July 10, 2001

ISBN: 0-375-80613-4

Page Count: 32

Publisher: Knopf

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: June 1, 2001

CHILDREN'S GENERAL CHILDREN'S

Share your opinion of this book

More by Roseanne Thong

BOOK REVIEW

by Roseanne Thong & illustrated by Yangsook Choi

by Yangsook Choi & illustrated by Yangsook Choi

by Milly Lee & illustrated by Yangsook Choi

More About This Book

SEEN & HEARD

A DOG NAMED SAM

by Janice Boland & illustrated by G. Brian Karas ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 1, 1996

A book that will make young dog-owners smile in recognition and confirm dogless readers' worst suspicions about the mayhem caused by pets, even winsome ones. Sam, who bears passing resemblance to an affable golden retriever, is praised for fetching the family newspaper, and goes on to fetch every other newspaper on the block. In the next story, only the children love Sam's swimming; he is yelled at by lifeguards and fishermen alike when he splashes through every watering hole he can find. Finally, there is woe to the entire family when Sam is bored and lonely for one long night. Boland has an essential message, captured in both both story and illustrations of this Easy-to-Read: Kids and dogs belong together, especially when it's a fun-loving canine like Sam. An appealing tale. (Picture book. 4-8)

Pub Date: April 1, 1996

ISBN: 0-8037-1530-7

Page Count: 40

Publisher: Dial Books

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 1996

by Carson Ellis ; illustrated by Carson Ellis ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 24, 2015

Visually accomplished but marred by stereotypical cultural depictions.

Ellis, known for her illustrations for Colin Meloy’s Wildwood series, here riffs on the concept of “home.”

Shifting among homes mundane and speculative, contemporary and not, Ellis begins and ends with views of her own home and a peek into her studio. She highlights palaces and mansions, but she also takes readers to animal homes and a certain famously folkloric shoe (whose iconic Old Woman manages a passel of multiethnic kids absorbed in daring games). One spread showcases “some folks” who “live on the road”; a band unloads its tour bus in front of a theater marquee. Ellis’ compelling ink and gouache paintings, in a palette of blue-grays, sepia and brick red, depict scenes ranging from mythical, underwater Atlantis to a distant moonscape. Another spread, depicting a garden and large building under connected, transparent domes, invites readers to wonder: “Who in the world lives here? / And why?” (Earth is seen as a distant blue marble.) Some of Ellis’ chosen depictions, oddly juxtaposed and stripped of any historical or cultural context due to the stylized design and spare text, become stereotypical. “Some homes are boats. / Some homes are wigwams.” A sailing ship’s crew seems poised to land near a trio of men clad in breechcloths—otherwise unidentified and unremarked upon.

Pub Date: Feb. 24, 2015

ISBN: 978-0-7636-6529-6

Publisher: Candlewick

Review Posted Online: Nov. 17, 2014

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Dec. 1, 2014

More by Randall de Sève

by Randall de Sève ; illustrated by Carson Ellis

by Mac Barnett ; illustrated by Carson Ellis

by Carson Ellis ; illustrated by Carson Ellis

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

- Announcements

- About About the Journal About the American Name Society Journal Aims and Scope Editors' Profiles Editorial Team Ethical Standards and Policies Privacy Statement Contact

- Submissions Manuscript Guidelines Names Style Sheet Terminology/Keywords Publication Policy Publication Charges Submission Checklist Copyright Policy Book Reviews

Planting Seeds in Literary Narrative: Onomastic Concepts and Questions in Yangsook Choi's The Name Jar

- Anne W. Anderson

Author Biography

Independent Researcher

Published 2022-12-06

- onomastic theory ,

- narrativity ,

- anthroponymy ,

- children's literature ,

- immigration ,

- The Name Jar ,

- name giving

Copyright (c) 2022 Dr. Anderson

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

On the surface, Yangsook Choi’s The Name Jar (2001) is a simple story of a very young immigrant girl who considers changing her name so her new classmates will like her. Embedded within the story, however, are key onomastic concepts and questions: What are names? Who decides our names and how? Can we choose different names for different contexts and should we? If we change our names, does who we are change? I revisit scholarly conversations about onomastic theory and discuss narrative as a means of knowing. I draw on Nikolajeva’s (2003) work in narrativity, that is, the ways in which the narrative encourages or discourages deeper thought about the implications of the text. Using analytic reading strategies, I demonstrate how Choi’s uses of verbal and visual narrative devices give the story depth and create space for readers, including scholars, to parse out and ponder onomastic concepts and questions for themselves.

- Abbott, H. Porter. 2008. The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Akinnaso, F. Niyi. 1981. “Names and Naming Principles in Cross-Cultural Perspective”. Names 29,

- no. 1: 37–63.

- Algeo, John. 1982. “Magic Names: Onomastics in the Fantasies of Ursula Le Guin”. American Name Society 30, no. 2: 59–67.

- Algeo, John. 1985 (2010). “Is a Theory of Names Possible?” Names 33, no. 3: 136–144. Reprint, 58,

- no. 2: 90–96.

- Algeo, John. 2001. “A Fancy for the Fantastic: Reflections on Names in Fantasy Literature”. Names 49,

- no. 4: 248–253.

- Algeo, John and Katie Algeo. 2000. “Onomastics as an Interdisciplinary Study”. Names 48, no. 3/4: 265–274.

- Alter, Grit. 2016. “What’s in a Name? Assimilation Ideology in Picturebooks”. Children’s Literature in English Language Education Journal 4, no. 1: 1–24.

- Anderson, Anne W. 2016. “‘Out of the Everywhere Into Here’: Rhetoricity and Transcendence as Common Ground for Spiritual Research”. Toward a Spiritual Research Paradigm: Exploring New Ways of Knowing, Researching, and Being. Edited by Jing Lin, Rebecca L. Oxford, and Tom Culham, 25–53. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

- Bertills, Yvonne. 2013. Beyond Identification: Proper Names in Children’s Literature. Tavastg: Åbo Akademi University Press.

- Black, Sharon and Brad Wilcox. 2011. “Sense and Serendipity: Some Ways Fictions Writers Choose Character Names”. Names 59, no. 3: 152–63.

- Chen, Jinyan. 2021. “The Adoption of non-Chinese Names as Identity Markers of Chinese International Students in Japan: A Case Study at a Japanese Comprehensive Research University”. Names 69, no. 2: 11–19.

- Choi, Yangsook. 2001. The Name Jar. Illustrated by Yangsook Choi. New York: Dragonfly Books.

- Clark, Beverly Lyon. 2003. Kiddie Lit: The Cultural Construction of Children’s Literature in America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Crotty, Michael. 2010. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. First published 1998 by Allen & Unwin (St. Leonards, Australia).

- Gardner, Janet E. and Joanne Diaz. 2021. Reading and Writing about Literature: A Portable Guide. 5th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

- Gerhards, Jürgen and Julia Tuppat. 2001. “‘Boundary Maintenance’ or ‘Boundary Crossing’? Name-Giving Practices among Immigrants in Germany”. Names 69, no. 3: 28–40.

- Gerus-Tarnawecky, Iraida. 1968. “Literary Onomastics”. Names 16, no. 4: 312–324.

- Hopson, Sarah. 2020. “Teaching Children Philosophy: The Name Jar”. The Prindle Institute for Ethics. https://www.prindleinstitute.org/books/the-name-jar/

- Iser, Wolfgang. 2006. How to Do Theory. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Jacobus, Lee A. 2005. The Bedford Introduction to Drama. 5th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

- Kallio, Kirsi Paulina. 2012. “Political Presence and the Politics of Noise”. Space and Polity, 16, no. 3: 287–302.

- Kiefer, Barbara Z. 2010. Charlotte Huck’s Children’s Literature. 10th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Nikolajeva, Maria. 2003. “Beyond the Grammar of Story, or How Can Children’s Literature Criticism Benefit from Narrative Theory?” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 28, no. 1: 5–16.

- Nikolajeva, Maria and Carole Scott. 2006. How Picturebooks Work. New York: Routledge.

- Nilsen, Aleen Pace and Don L. F. Nilsen. 2007. Names and Naming in Young Adult Literature. Lanham: Scarecrow Press.

- Nilsen, Aleen Pace and Don L. F. Nilsen. 2009. “Tropes and Schemes in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Books”. The English Journal 98, no. 6: 60-68.

- Nodelman, Perry and Mavis Reimer. 2003. The Pleasures of Children’s Literature. 3rd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Pritchard, Michael. 2020. "Philosophy for Children”. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/children/

- Recorvits, Helen. 2003. My Name is Yoon. Illustrated by Gabi Swiatkowska. New York: Macmillan.

- Robinson, Christopher L. 2011. “Onomaturgy vs. Onomastics: An Introduction to the Namecraft of Ursula K. Le Guin”. Names 59, no. 3: 129–38.

- Robinson, Christopher L. 2013. “What Makes the Names of Middle-earth So Fitting? Elements of Style in the Namecraft of J. R. R. Tolkien”. Names 61, no. 2: 65–74.

- Robinson, Christopher L. 2015. “A Sense of the Magical: Names in Lord Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter”. Names 63, no. 4: 189–199.

- Robinson, Christopher L. 2018. “The Namework of Ursula K. Le Guin”. Names 66, no. 3: 125–134.

- Rose, Gillian. 2012. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Sands-O’Connor, Karen. 2008. “After Midnight: Naming, West Indians, and British Children’s Literature”. Names 56, no. 1: 41–46.

- Solomon, J. Fisher. 1985. “Speaking of No One: the Logical Status of Fictional Proper Names”. Names 33, no. 3: 145–157.

- Tatar, Maria, ed. 2012. The Annotated Brothers Grimm: The Bicentennial Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Wartenberg, Thomas E. 2013. A Sneetch is a Sneetch and Other Philosophical Discoveries: Finding Wisdom in Children’s Literature. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Wartenberg, Thomas E. 2014. Big Ideas for Little Kids: Teaching Philosophy through Children’s Literature. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Wu, Ellen Dionne. 1999. “They Call Me Bruce, But They Won’t Call Me Bruce Jones:” Asian American Naming Preferences and Patterns”. Names 47, no. 1: 21–50.

- Yi, Joanne H. 2014. “‘My Heart Beats in Two Places’: Immigration Stories in Korean-American Picture Books.” Children’s Literature in Education 45: 129–144.

- Zelinsky, Wilbur. 2002. “Slouching Toward a Theory of Names: A Tentative Taxonomic Fix”. Names 50,

- no. 4: 243–262.

- Frequently Asked Questions

- About the Writers

- Book Reviews

- Book Reviews A-Z

- Books Written for Preschoolers (infant – 5 yrs)

- Books written for Grades 1-4 (Ages 6 – 9 years)

- Books written for Grades 5-8 (Ages 10 – 13 years)

- Books written for Grades 9-12 (Ages 14 – 17)

- Lectionary Links:Narrative Lectionary

- Lectionary Links:Revised Common Lectionary

- Children (Multi-Age) Lesson Plans

- Youth Lesson Plans

- Adult Lesson Plans

- Intergenerational Lesson Plans

- Bibliographies

- Guest Voices

- Scripture Index

- Theme Index

Book Review

The name jar.

Author: Yangsook Choi

Publisher: Dragonfly Books; Reprint Edition

Publication Date: October 14, 2003

ISBN: 978-0440417996

Audience: Ages 4-8

Summary: New year, new country, new school, the first day. Unhei ( Yoon-hye)is nervous and excited, but for assurance she carries with her the red pouch that her grandmother gave her as they said goodbye in Korea. In the pouch is a block of wood with her name written on it in Korean characters and an ink pad. The other children on the bus ask her name then make fun of it and mispronounce it. The welcome in her class is better but she tells them when they ask her name, “I haven’t picked one yet.” At home, when Unhei says she would like an American name, her mother reminds her of how carefully her name was chosen with the help of a Name Master. “It’s too different,” complains Unhei and her mother reminds her that she is different and “That’s a good thing.” Mr. Kim at the Korean market pronounces her name correctly and appreciates its beauty and meaning. The next morning at school there is a glass jar on her desk containing American names on slips of paper. The class wants to help her select a new name Her new friend, Joey, sees her name stamp and printed name and admires it. On the day that Unhei is to choose her American name, the name jar is missing. But by now Unhei chooses to keep her own name and Joey chooses a Korean name for himself that means “friend.” Joey brings the name jar to her home. He had taken it because he wanted her to choose her Korean name.

Literary elements at work in the story: The theme of this simple story is cultural differences from pronunciation to customs and family. The unappreciative children on the bus ridicule Unhei’s name (in part because they can’t pronounce it.) Unhei’s acceptance in her class room is almost immediate. Still we can feel how difficult it is for Unhei to be different even as she is reminded of the values of her Korean culture.. Yangsook Choi came to the US from Korea in 1991 and has produced an ALA Notable Book and an IRA Children’s Book Award winner.

How does the perspective on gender/race/culture/economics/ability make a difference to the story? The cultural differences are a source of ridicule in one instance but are accepted and enjoyed in Unhei’s class. The teacher of this class (2 nd grade?) is a man, Mr. Cocotos, possibly Japanese. Cultural differences are valued in several conversations.

Theological Conversation Partners: Three aspects of The Name Jar deserve our attention. Biblically, names are important. Abraham, Sarah, Jacob, and Peter all had their names changed to indicate who they were becoming. In baptism our names are said, marking us as Christ’s own. God knows Israel by name and calls Israel by name. (Is. 43: 1) Jesus was given two names in the gospels: Jesus, which means savior, and Emmanuel, which means God with us. Names represent our identity. There is value in helping children say their own names and the names of others clearly and respectfully, in practicing introduction. The second aspect is welcoming the stranger. The Hebrews are reminded that they were aliens and God gives special instructions about showing hospitality and care for them. (Ex.23:9 is one of many examples.) And the third is the diversity of God’s children. Each child, each culture has some richness and strength that we need to value and which will broaden our lives.

Faith Talk Questions:

- Have you ever gone to a new school and felt like Unhei, even though it is a school in your own country?

- Have you ever worried about being different? In some ways Unhei is like you then.

- Why do the children on the bus make fun of Unhei’s name?

- Unhei’s mother says that being different is good. Do you agree?

- What experiences helped Unhei appreciate her Korean name? Do you think she made a good choice in keeping her Korean name?

- Did you get to choose your name? Does it have a special meaning?

- What name do you share with every member of your church family?

- Have your tried to pronounce a name in another language?

- Is there someone in your school or neighborhood from another country? How can you welcome that person?

Alumna and regular contributor Virginia Thomas is our book reviewer this week.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

READING ACTIVITIES

WRITING ACTIVITIES

SOCIAL- EMOTIONAL LEARNING

FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE

The Name Jar Book Review

While many teachers are on summer break or will be in the next few weeks, the teacher brain never turns off. Even while relaxing, they are thinking about plans for next year. This often includes new classroom management techniques and creating new hands-on lessons. Additionally, it includes ensuring that students feel welcome in the classroom and have positive relationships with classmates. Honestly, relationships are a crucial part of having a great school year. A favorite way to build a community is through books. They help students relate to characters while understanding how to handle different situations. Thus, this book review on The Name Jar will show an incredible way to start the year. The Name Jar book helps ensure all students are a part of the classroom and proud of who they are!

The Name Jar

Author and illustrator Yangsook Choi created a heartwarming story about facing fears in new situations.

Being the new kid in school is tough! However, Unhei is not just moving schools. She is moving countries! On the journey from South Korea to America, Unhei thinks about how much adjustment she will go through. One of the biggest worries surrounds the first day of school. Sadly, kids on the bus make fun of Unhei because they cannot pronounce her name. This makes her so nervous about entering a new classroom. When the teacher asks for her name, Unhei decides she does not want to go through the bus situation again. Instead, she says she has not selected an American name, so her classmates make a name jar. While drawing out different options, nothing feels right. Thankfully, a new friend shows Unhei that her name is the best option.

After reading this story, students will understand the importance of being themselves and proud of who they are.

The Name Jar Book Activities

The Name Jar Book Activities :

This no-prep activity set contains many ways for students to get back into an academic mindset. Specifically, there are many literary standards with discussion questions, sequencing skills, and critical detail review. Additionally, students will work on vocabulary words, compare and contrast, and fact or opinion. There are also many activities to help students be proud of who they are. They will complete a name acrostic and activities to remind them how their name makes them all unique. These activities will be sure to help build a positive classroom environment!

Family History:

Unhei did not get to pick her Korean name. However, her new classmates did not get to choose their names either. To help remind all students that no one picked their name, have them ask their families how it was selected. Then, they can write a few sentences about it and share responses with the class. This will be a great way to remind students they have been unique since birth!

Point of View:

Often, students can get confused when learning point of view. Luckily, The Name Jar book provides a helpful way to help students with this skill. They can locate different pronouns on the pages to prove the viewpoint the author wrote the book in.

Cause and Effect:

Students do not always see the relationship between what they do and the outcome in elementary or lower middle school. Thus, they need time to practice identifying cause and effect situations. Honestly, this book has so many options to use. This means that students can practice a few examples as a class. Then, they can work in small groups or independently. As students gain confidence, teachers can even make this activity more complex. For instance, students can be given a specific cause and identify the effect. Or, they can be given the effect and determine the cause.

The start of the year is such an exciting time. However, it can also be highly stressful and overwhelming. Luckily, this book review on The Name Jar shows how it is the perfect book to begin the year. Ultimately, The Name Jar book helps establish a positive and inclusive classroom climate the minute students arrive.

If you do not want to miss any of the upcoming lessons, join my email list to be notified of all the interactive lessons coming up! By joining the email list, you will also receive a FREE Growth Mindset Bell Ringer for blog exclusive subscribers!

Share this:

Latest Posts

Activities for Finding the Theme of a Story

The Benefits of Using Anchor Charts in the Classroom

How to Handle Moving Schools

Why the Kirsten’s Kaboodle Membership is a No-Brainer

Copyright © 2024 KIRSTEN'S KABOODLE

🐇 Books for Your Little Bunny's Easter Basket → 🐇

The Name Jar

By yangsook choi, illustrated by yangsook choi.

About the Book

Product details.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on January 30, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 14, 2023.

Literary analysis means closely studying a text, interpreting its meanings, and exploring why the author made certain choices. It can be applied to novels, short stories, plays, poems, or any other form of literary writing.

A literary analysis essay is not a rhetorical analysis , nor is it just a summary of the plot or a book review. Instead, it is a type of argumentative essay where you need to analyze elements such as the language, perspective, and structure of the text, and explain how the author uses literary devices to create effects and convey ideas.

Before beginning a literary analysis essay, it’s essential to carefully read the text and c ome up with a thesis statement to keep your essay focused. As you write, follow the standard structure of an academic essay :

- An introduction that tells the reader what your essay will focus on.

- A main body, divided into paragraphs , that builds an argument using evidence from the text.

- A conclusion that clearly states the main point that you have shown with your analysis.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: reading the text and identifying literary devices, step 2: coming up with a thesis, step 3: writing a title and introduction, step 4: writing the body of the essay, step 5: writing a conclusion, other interesting articles.

The first step is to carefully read the text(s) and take initial notes. As you read, pay attention to the things that are most intriguing, surprising, or even confusing in the writing—these are things you can dig into in your analysis.

Your goal in literary analysis is not simply to explain the events described in the text, but to analyze the writing itself and discuss how the text works on a deeper level. Primarily, you’re looking out for literary devices —textual elements that writers use to convey meaning and create effects. If you’re comparing and contrasting multiple texts, you can also look for connections between different texts.

To get started with your analysis, there are several key areas that you can focus on. As you analyze each aspect of the text, try to think about how they all relate to each other. You can use highlights or notes to keep track of important passages and quotes.

Language choices

Consider what style of language the author uses. Are the sentences short and simple or more complex and poetic?

What word choices stand out as interesting or unusual? Are words used figuratively to mean something other than their literal definition? Figurative language includes things like metaphor (e.g. “her eyes were oceans”) and simile (e.g. “her eyes were like oceans”).

Also keep an eye out for imagery in the text—recurring images that create a certain atmosphere or symbolize something important. Remember that language is used in literary texts to say more than it means on the surface.

Narrative voice

Ask yourself:

- Who is telling the story?

- How are they telling it?

Is it a first-person narrator (“I”) who is personally involved in the story, or a third-person narrator who tells us about the characters from a distance?

Consider the narrator’s perspective . Is the narrator omniscient (where they know everything about all the characters and events), or do they only have partial knowledge? Are they an unreliable narrator who we are not supposed to take at face value? Authors often hint that their narrator might be giving us a distorted or dishonest version of events.

The tone of the text is also worth considering. Is the story intended to be comic, tragic, or something else? Are usually serious topics treated as funny, or vice versa ? Is the story realistic or fantastical (or somewhere in between)?

Consider how the text is structured, and how the structure relates to the story being told.

- Novels are often divided into chapters and parts.

- Poems are divided into lines, stanzas, and sometime cantos.

- Plays are divided into scenes and acts.

Think about why the author chose to divide the different parts of the text in the way they did.

There are also less formal structural elements to take into account. Does the story unfold in chronological order, or does it jump back and forth in time? Does it begin in medias res —in the middle of the action? Does the plot advance towards a clearly defined climax?

With poetry, consider how the rhyme and meter shape your understanding of the text and your impression of the tone. Try reading the poem aloud to get a sense of this.

In a play, you might consider how relationships between characters are built up through different scenes, and how the setting relates to the action. Watch out for dramatic irony , where the audience knows some detail that the characters don’t, creating a double meaning in their words, thoughts, or actions.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Your thesis in a literary analysis essay is the point you want to make about the text. It’s the core argument that gives your essay direction and prevents it from just being a collection of random observations about a text.

If you’re given a prompt for your essay, your thesis must answer or relate to the prompt. For example:

Essay question example

Is Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” a religious parable?

Your thesis statement should be an answer to this question—not a simple yes or no, but a statement of why this is or isn’t the case:

Thesis statement example

Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” is not a religious parable, but a story about bureaucratic alienation.

Sometimes you’ll be given freedom to choose your own topic; in this case, you’ll have to come up with an original thesis. Consider what stood out to you in the text; ask yourself questions about the elements that interested you, and consider how you might answer them.

Your thesis should be something arguable—that is, something that you think is true about the text, but which is not a simple matter of fact. It must be complex enough to develop through evidence and arguments across the course of your essay.

Say you’re analyzing the novel Frankenstein . You could start by asking yourself:

Your initial answer might be a surface-level description:

The character Frankenstein is portrayed negatively in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

However, this statement is too simple to be an interesting thesis. After reading the text and analyzing its narrative voice and structure, you can develop the answer into a more nuanced and arguable thesis statement:

Mary Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

Remember that you can revise your thesis statement throughout the writing process , so it doesn’t need to be perfectly formulated at this stage. The aim is to keep you focused as you analyze the text.

Finding textual evidence

To support your thesis statement, your essay will build an argument using textual evidence —specific parts of the text that demonstrate your point. This evidence is quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to explain your argument to the reader.

It can be useful to comb through the text in search of relevant quotations before you start writing. You might not end up using everything you find, and you may have to return to the text for more evidence as you write, but collecting textual evidence from the beginning will help you to structure your arguments and assess whether they’re convincing.

To start your literary analysis paper, you’ll need two things: a good title, and an introduction.

Your title should clearly indicate what your analysis will focus on. It usually contains the name of the author and text(s) you’re analyzing. Keep it as concise and engaging as possible.

A common approach to the title is to use a relevant quote from the text, followed by a colon and then the rest of your title.

If you struggle to come up with a good title at first, don’t worry—this will be easier once you’ve begun writing the essay and have a better sense of your arguments.

“Fearful symmetry” : The violence of creation in William Blake’s “The Tyger”

The introduction

The essay introduction provides a quick overview of where your argument is going. It should include your thesis statement and a summary of the essay’s structure.

A typical structure for an introduction is to begin with a general statement about the text and author, using this to lead into your thesis statement. You might refer to a commonly held idea about the text and show how your thesis will contradict it, or zoom in on a particular device you intend to focus on.

Then you can end with a brief indication of what’s coming up in the main body of the essay. This is called signposting. It will be more elaborate in longer essays, but in a short five-paragraph essay structure, it shouldn’t be more than one sentence.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him.

Some students prefer to write the introduction later in the process, and it’s not a bad idea. After all, you’ll have a clearer idea of the overall shape of your arguments once you’ve begun writing them!

If you do write the introduction first, you should still return to it later to make sure it lines up with what you ended up writing, and edit as necessary.

The body of your essay is everything between the introduction and conclusion. It contains your arguments and the textual evidence that supports them.

Paragraph structure

A typical structure for a high school literary analysis essay consists of five paragraphs : the three paragraphs of the body, plus the introduction and conclusion.

Each paragraph in the main body should focus on one topic. In the five-paragraph model, try to divide your argument into three main areas of analysis, all linked to your thesis. Don’t try to include everything you can think of to say about the text—only analysis that drives your argument.

In longer essays, the same principle applies on a broader scale. For example, you might have two or three sections in your main body, each with multiple paragraphs. Within these sections, you still want to begin new paragraphs at logical moments—a turn in the argument or the introduction of a new idea.

Robert’s first encounter with Gil-Martin suggests something of his sinister power. Robert feels “a sort of invisible power that drew me towards him.” He identifies the moment of their meeting as “the beginning of a series of adventures which has puzzled myself, and will puzzle the world when I am no more in it” (p. 89). Gil-Martin’s “invisible power” seems to be at work even at this distance from the moment described; before continuing the story, Robert feels compelled to anticipate at length what readers will make of his narrative after his approaching death. With this interjection, Hogg emphasizes the fatal influence Gil-Martin exercises from his first appearance.

Topic sentences

To keep your points focused, it’s important to use a topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph.

A good topic sentence allows a reader to see at a glance what the paragraph is about. It can introduce a new line of argument and connect or contrast it with the previous paragraph. Transition words like “however” or “moreover” are useful for creating smooth transitions:

… The story’s focus, therefore, is not upon the divine revelation that may be waiting beyond the door, but upon the mundane process of aging undergone by the man as he waits.

Nevertheless, the “radiance” that appears to stream from the door is typically treated as religious symbolism.

This topic sentence signals that the paragraph will address the question of religious symbolism, while the linking word “nevertheless” points out a contrast with the previous paragraph’s conclusion.

Using textual evidence

A key part of literary analysis is backing up your arguments with relevant evidence from the text. This involves introducing quotes from the text and explaining their significance to your point.

It’s important to contextualize quotes and explain why you’re using them; they should be properly introduced and analyzed, not treated as self-explanatory:

It isn’t always necessary to use a quote. Quoting is useful when you’re discussing the author’s language, but sometimes you’ll have to refer to plot points or structural elements that can’t be captured in a short quote.

In these cases, it’s more appropriate to paraphrase or summarize parts of the text—that is, to describe the relevant part in your own words:

The conclusion of your analysis shouldn’t introduce any new quotations or arguments. Instead, it’s about wrapping up the essay. Here, you summarize your key points and try to emphasize their significance to the reader.

A good way to approach this is to briefly summarize your key arguments, and then stress the conclusion they’ve led you to, highlighting the new perspective your thesis provides on the text as a whole:

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, August 14). How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved March 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/literary-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write a narrative essay | example & tips, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Name Jar explores questions about difference, identity, and cultural assimilation. When Unhei, a young Korean girl, moves to America with her family and arrives at a new school, she begins to wonder if she should also choose a new name. Her classmates suggest Daisy, Miranda, Lex, and more, but nothing seems to fit.

Her new classmates are fascinated by this no-name girl and decide to help out by filling a glass jar with names for her to pick from. But while Unhei practices being a Suzy, Laura, or Amanda, one of her classmates comes to her neighborhood and discovers her real name and its special meaning. On the day of her name choosing, the name jar has ...

September 22, 2022. Yangsook Choi's The Name Jar traces the literal journey of Unhei from her home in South Korea to her new life in the United States. Unhei faces a new land, a new language, a new school, even a new alphabet! When children on her first day of school butchered her name, Unhei starts believing that a new country must mean she ...

The Name Jar: A Book Review. Summary: Unhei (pronounced Yoon-Hey) is leaving all that she knows in Korea to move to the United States. Before she leaves, her grandmother gives her a red satin pouch with her name engraved on a stamp written in Korean. When Unhei comes to the United States she is very anxious about starting school.

Multicultural Literature for My Classroom Title: The Name Jar Author: Yangsook Chor Publication Date: 2001 Plot Summary: Unhei is a Korean girl attending an American school for the first time. On her first day of school, ... In primary grades, I will create a name jar for my students to add their names. The students will

Yangsook Choi wrote and illustrated The Name Jar in 2001. It relays the story of Unhei, a young girl from Korea whose family moved to America. On her first day of school, Unhei's fellow classmates fail to pronounce her name. They continue to make fun of it, referring to her as "hey-you.". She decides to choose an American name so she ...

So instead of introducing herself on the first day of school, she decides to choose an American name from a glass jar. But while Unhei thinks of being a Suzy, Laura, or Amanda, nothing feels right. With the help of a new friend, Unhei will learn that the best name is her own. From acclaimed creator Yangsook Choi comes the bestselling classic ...

Unhei has just left her Korean homeland and come to America with her parents. As she rides the school bus toward her first day of school, she remembers the farewell at the airport in Korea and examines the treasured gift her grandmother gave her: a small red pouch containing a wooden block on which Unhei's name is carved. Unhei is ashamed when the children on the bus find her name difficult ...

Yangsook Choi grew up in Seoul, Korea. She has written and illustrated several books for young readers, including The Sun Girl and the Moon Boy and Good-bye, 382 Shin Dang Dong by Frances Park and Ginger Park. The first book she illustrated, Nim and the War Effort by Milly Lee, was an ALA Notable Book and an IRA-CBC Children's Book Award ...

But while Unhei practices being a Suzy, Laura, or Amanda, one of her classmates comes to her neighborhood and discovers her real name and its special meaning. On the day of her name choosing, the name jar has mysteriously disappeared. Encouraged by her new friends, Unhei chooses her own Korean name and helps everyone pronounce it—Yoon-Hey.

The Name Jar. Author Yangsook Choi. Illustrated by Yangsook Choi. Add to Wish List Look inside. Listen to a clip from the audiobook. 0:000:00. Paperback. $ 8.99 US. RH Childrens Books | Dragonfly Books.

Planting Seeds in Literary Narrative: Onomastic Concepts and Questions in Yangsook Choi's The Name Jar PDF Anne W. Anderson ... On the surface, Yangsook Choi's The Name Jar (2001) is a simple story of a very young immigrant girl who considers changing her name so her new classmates will like her. Embedded within the story, however, are key ...

Having just moved from Korea, Unhei is anxious about fitting in. So instead of introducing herself on the first day of school, she decides to choose an American name from a glass jar. But while Unhei thinks of being a Suzy, Laura, or Amanda, nothing feels right. With the help of a new friend, Unhei will learn that the best name is her own. From ...

By Yangsook Choi (story and art) From the September 2021 Issue. Learning Objective: Students will read a realistic fiction story about Unhei, a young girl who has just moved to the United States from Korea, and identify how her feelings about her name change throughout the story. Complexity Factors. Lexiles: 500L-600L.

Having just moved from Korea, Unhei is anxious about fitting in. So instead of introducing herself on the first day of school, she decides to choose an American name from a glass jar. But while Unhei thinks of being a Suzy, Laura, or Amanda, nothing feels right. With the help of a new friend, Unhei will learn that the best name is her own.

The Name Jar. Yangsook Choi. $8.99 US. Paperback. Oct 14, 2003. Join Penguin Random House Education in celebrating the contributions of Black authors and illustrators. In honor of Black History Month in February, we are highlighting essential fiction and nonfiction to be shared and discussed by students and teachers alike.

The Name Jar. Title: The Name Jar. Author: Yangsook Choi. Publisher: Dragonfly Books; Reprint Edition. Publication Date: October 14, 2003. ISBN: 978-0440417996. Audience: Ages 4-8. Summary: New year, new country, new school, the first day. Unhei ( Yoon-hye)is nervous and excited, but for assurance she carries with her the red pouch that her ...

But while Unhei practices being a Suzy, Laura, or Amanda, one of her classmates comes to her neighborhood and discovers her real name and its special meaning. On the day of her name choosing, the name jar has mysteriously disappeared. Encouraged by her new friends, Unhei chooses her own Korean name and helps everyone pronounce it--"Yoon-Hey,"

It is a reminder of how diversity in children's literature is needed. When it comes to diversity in children's books, only 7% of published books are about Asian populations. The Name Jar is one of ...

The Name Jar book is an incredible way to start the year with activities that will help students be proud of who they are! ... Specifically, there are many literary standards with discussion questions, sequencing skills, and critical detail review. Additionally, students will work on vocabulary words, compare and contrast, and fact or opinion. ...

Having just moved from Korea, Unhei is anxious about fitting in. So instead of introducing herself on the first day of school, she decides to choose an American name from a glass jar. But while Unhei thinks of being a Suzy, Laura, or Amanda, nothing feels right. With the help of a new friend, Unhei will learn that the best name is her own. From ...

Table of contents. Step 1: Reading the text and identifying literary devices. Step 2: Coming up with a thesis. Step 3: Writing a title and introduction. Step 4: Writing the body of the essay. Step 5: Writing a conclusion. Other interesting articles.