- RESEARCH ARTICLE

- Cite this article

We’re sorry, something doesn't seem to be working properly.

Please try refreshing the page. If that doesn't work, please contact support so we can address the problem.

214 Accesses

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Similar content being viewed by others

The Heterogenous Threshold Effects of Public Debt on Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence from Developing Countries

Impact of House Price on Economic Stability: Some Lessons from OECD Countries

Impact of corruption, unemployment and inflation on economic growth evidence from developing countries

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 06 July 2018

Is money going digital? An alternative perspective on the current hype

- Daniel Gersten Reiss ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1634-760X 1

Financial Innovation volume 4 , Article number: 14 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

9985 Accesses

9 Citations

34 Altmetric

Metrics details

Current financial discourse suggests the imminence of a cashless society, a concept that arose from the global popularization of digital financial services and the development of technologies with the potential for application in financial markets. However, claims about the impending obsolescence of paper money are neither disruptive nor a novelty. Instead, this paper argues that the conversion of money from paper to bits has been a gradual, adaptive process, and that money is already digital. Moreover, in this paper we propose that the statuses of electronic money (e-money) and banknotes have switched in the view of monetary authorities.

Introduction

Current discourse about money mainly focuses on its supply in a digital format. The wide access to technological products and the introduction of bitcoin triggered recent hype, which suggests that a disruptive transformation in financial markets and systems is imminent. However, corresponding discussions surrounding electronic money (e-money), virtual currencies, digital financial services, and mobile wallets topics commonly overlap with the discussion of the digitalization of money.

Policymakers and regulators have invested considerable effort in dealing with these mixed perspectives on the digitalization of money and catching up with market trends. In addition to hosting discussions at the national level, international bodies have undertaken several initiatives to explore these topics (CPMI 2015 ; CPMI 2017 ; IOSCO 2017 ; Pearlman 2017 ). Building on the existing literature, we analyze current perceptions of the digitalization of paper money and posit that, despite the recent hype, this digitalization is a long-term, ongoing process.

The rise of digital financial services

For the most part, what we understand as money is that it stores a quantifiable value that one expects to be traded for any other asset in the short or long run. In our minds, money usually takes the form of sovereign currencies, which are associated with physical money—that is, banknotes and coins (cash).

Digital financial services have brought financial services from bank branches to our homes and pockets. Thanks to the information and communications technology (ICT) revolution, money can conveniently be transferred from a bank account to an individual from a mobile device. Money transfers (even cross-border), bill payments, and loan requests have all become readily available through technology, bolstering the notion that money will soon go digital and paper money will become defunct.

However, this concept is neither new nor recent. Although currently presented as disruptive, digital innovations in financial services have been discussed for at least two decades. In the late 1990s, it was already suggested that electronic cash cards could eventually displace cash Footnote 1 (Shy and Tarkka 1998 ). By that time, both consumers and the industry were enthusiastic about the potential adoption of payment cards, but the economic rationale for the adoption of e-money Footnote 2 remained unclear (Santomero and Seater 1996 ). Despite their substantial potential benefits, new technologies in the payments market have typically only been adopted after a considerable delay (Berger et al. 1996 ).

The role of telecommunications in financial inclusion initiatives

This transformation process occurs both in developed and developing financial markets, even though the two markets are split in the provision of financial services through digital media. In developed markets, next-generation cell phones and wide broadband access have enabled the rise of powerful payment platforms that have allowed the digitalization of traditional services and the launch of innovative products. In these markets, the main concern has been the availability and credibility of innovative products (Dahlberg et al. 2015 ).

Innovative platforms are booming with novel technologies in developed markets, but access to novel technologies remains limited in emerging markets. In spite of this, the use of e-money has increased in these markets with the help of telecommunications infrastructure. In these markets, the financial inclusion argument is the key driver; instead of new technologies, new methods of providing financial services supported by e-money have been adopted. Since mobile services have gained more widespread adoption than financial services among poorer segments of the population, financial inclusion initiatives are heavily dependent on the telecommunications network infrastructure (Albuquerque et al. 2014 ).

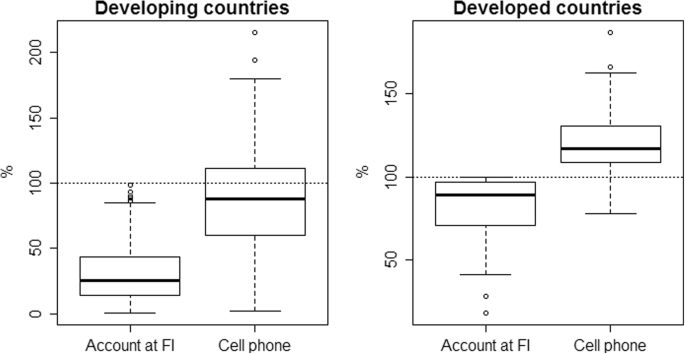

Figure 1 illustrates the considerable extent to which financial inclusion is dependent on telecom coverage in developing countries. When we observed the averages of various countries’ telecom coverage, we observed that the gap between financial services accessibility and telecom accessibility was considerably lower in developed countries (right panel) than in developing countries (left). Similarly, as telecom infrastructure was increasingly relied on for e-money transfers, the use of cell phones for making small payments rose in some African countries (e.g., Kenya and Tanzania) and was adopted as a major financial inclusion policy in Latin America countries such as Peru. Footnote 3

Financial services and the reach of telecom services. Demirguc-Kunt et al. ( 2015 ), International Telecommunication Union ( 2015 ). Account at FI is the share of individuals above 15 years old who have an account at a financial institution in a country, while Cell phone is the number of mobile cellular subscriptions per 100 people. Developing and developed countries are set according to the United Nation’s statistics

E-money has flourished as a representation of national currencies. Consisting of smart cards and internet-based solutions such as PayPal, e-money and digital wallets have kept pace with traditional money storage solutions in developed markets. In developing markets, by contrast, e-money and digital wallets have emerged as the core financial solution for the previously unbanked. Footnote 4

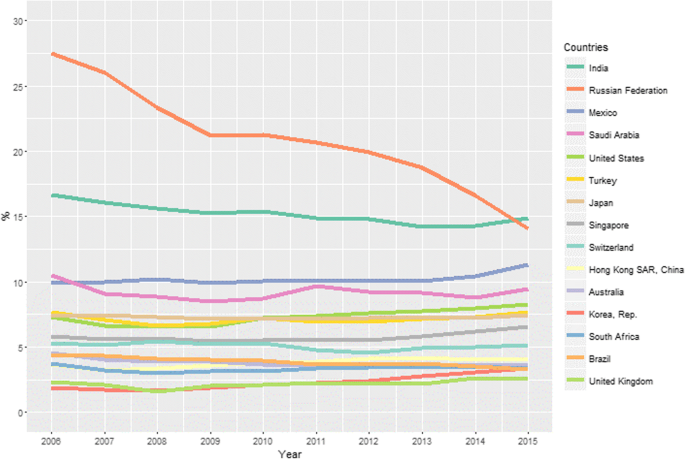

The most usual form of money

However, e-money is not the only digital form of money. In fact, bank accounts have been digitalized since banks records were first transformed from accounting books to computer systems. Even though cash is a high-turnover commodity commonly used by people for retail payments, most money is stored in digital form. Figure 2 displays the series ratio of cash in circulation outside banks to broad money for selected countries from 2006 to 2015. Cash in circulation can be defined as the money in peoples’ hands that is used for trade or savings. When individuals stored their cash in banks, it transformed, in their view, into a digital form. In addition to cash in circulation, broad money includes digitally represented money (e.g., demand deposits, e-money, and money in savings accounts). The country series correspond to the available data from countries reported in the BIS Red Book (CPMI 2016 ; CPSS 2012 ).

Ratio of cash in circulation outside banks to broad money (M4), 2006–15%, BIS Red Book countries with available data. CPMI ( 2016 ), CPSS ( 2012 ), IMF ( 2015 ). Annual data refers to the position on the year’s last business day

The 2015 figures show that India and Russia were the countries with the largest ratio of cash in circulation outside banks to broad money, at 15%. Russia demonstrated a sharp reduction in its ratio, of almost 30% in 2006, whereas India showed a slightly downward trend. All other countries fell below the 10% ratio, with the ratio below 5% in the United Kingdom, Brazil, South Africa, and Korea. However, cash in proportion to the whole economy remained somewhat stable during the past decade in these countries. No relevant changes were observed in the other countries except for Mexico and Korea, where there was a slight increase. The most of the existing money in the surveyed countries was already in digital form.

Roughly just 10% of the global money supply is still not digital. Some reasons people continue to hold cash are Footnote 5 : (i) its potential use as a medium of exchange when no other electronic payment methods are accepted by the counterpart agent; (ii) the protection it offers against financial institutions (cash is a liability against the currency issuer, whereas all other forms of money are liabilities against other financial intermediaries, and cash is a trusted paper representation of monetary value because the central bank is a trusted certifier of the currency), and (iii) the privacy it affords in financial transactions. The analysis of the motives for behaviors (ii) and (iii) are beyond the scope of the present note. Two current discussions cover these issues: motive (ii) in the central bank digital currency (CBDC) context and motive (iii) in the cryptocurrency context. Footnote 6

The future for cash

Since online transactions are a requirement for payment transactions, Footnote 7 the availability of electronic currency that can replace cash—motive (i)—is dependent on the cost of telecommunications infrastructure. As evidenced in remote areas without widespread and reliable telecom infrastructure, e-money is not always a less expensive replacement for cash. We expect, however, that such examples will become increasingly rare as ICT advances and the cost of telecom infrastructure decreases. Consequently, the use of cash will gradually become restricted to increasingly smaller niches.

As the use of cash declines, it may become inefficient for a central bank to continue to administer its logistics. This idea reiterates the notion that the issuers of e-money are private institutions making tokens from money in circulation. In reality, the opposite behavior appears imminent)—that is, 130 monetary authorities will distribute digital money while private institutions will make paper tokens from it as a niche service. Footnote 8

E-money may be granted a higher status than cash as ICT advances. Nonetheless, money, as a representative form of a quantifiable and tradable value, has transformed from a physical representation of bullion to a digital record kept at trusted institutions. During this transformation, e-money has become more convenient and has reached a broader group of users. Money is already digital.

Going beyond the direct relationship between the cash substitution by new digital instruments, discussions on cashless societies go back to earlier times. See, e.g., the discussion between White ( 1984a , 1986 ) and Greenfield and Yeager ( 1986 ) for a debate on the increasing liquidity of bank deposits.

Typically, jurisdictions define e-money as some monetary value stored on devices or electronic systems, which allows users to make payment transactions. In addition to banks, non-financial institutions, such as card or mobile networks, can usually also issue e-money. For a contrast among different kinds of money, see CPMI ( 2015 ).

For country examples, see Jack and Suri ( 2014 ), Mas and Morawczynski ( 2009 ), and Bernal ( 2017 ).

For a more precise discussion on this definition, see CPMI Digital Currencies report (CPMI 2015 ).

Note that the usual discussed motives for holding cash, such as the precautionary and speculative

motives, are discussed in a context that includes cash and quasi cash holdings (including demand-deposit balances and certificates of deposit).

For CBDC, see CPMI and MC ( 2018 ). For privacy in cryptocurrencies, see Androulaki et al. ( 2013 ).

The infrastructure resilience also conditions the availability of electronic payment instruments, which is also subject to random shocks such as natural disasters or malicious attacks.

Indeed, this occurrence would be akin to historical systems, where banks issued redeemable claims for outside money (i.e., gold, silver, bronze, etc.). See, e.g., White ( 1984b ), Selgin ( 1988 ), Dowd (2002).

Abbreviations

Bank for International Settlements

Central bank digital currency

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures

Information and communications technology

International Monetary Fund

International Telecommunications Union

Albuquerque JP, Diniz EH, Cernev AK (2014) Mobile payments: a scoping study of the literature and issues for future research. Inf Dev. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666914557338

Androulaki E et al (2013) Evaluating user privacy in Bitcoin. In: Sadeghi AR (ed) Financial Cryptography and Data Security. Lecture notes in computer science, vol 7859. Springer, Berlin

Google Scholar

Berger AN, Hancock D, Marquardt JC (1996) A framework for analyzing efficiency, risks, costs, and innovations in the payments system. J Money Credit Bank 28(4):696–732. https://doi.org/10.2307/2077917

Article Google Scholar

Bernal MV (2017) Retail payments innovations in Peru: Modelo Peru and financial inclusion. J Paym Strateg Syst 10(4):343–351

CPMI (2015). Digital currencies. Technical report 137, Bank for International Settlements. Committee on payments and market infrastructures. http://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d137.pdf . Accessed 01 Jan 2018

CPMI (2016). Statistics on payment, clearing and settlement systems in the CPMI countries - Figures for 2015. Technical report, Bank for International Settlements. Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures. http://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d152.htm . Accessed 01 Jan 2018

CPMI (2017). Distributed ledger technology in payment, clearing and settlement: an analytical Framework Technical report, Bank for International Settlements. Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures. Available at https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d157.pdf . Accessed 01 Jan 2018

CPMI and MC (2018). Central Bank digital currencies. Technical report, Bank for International Settlements. Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and Markets Committee. https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d174.pdf . Accessed 01 Jan 2018

CPSS (2012). Statistics on payment, clearing and settlement systems in the CPSS countries - Figures for 2010. Technical report, Bank of International Settlements. Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems. http://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d99.htm . Accessed 01 Jan 2018

Dahlberg T, Guo J, Ondrus J (2015) A critical review of mobile payment research. Electron Commer Res Appl 14(5):265–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2015.07.006

Demirguc-Kunt A, Klapper LF, Singer D and Van Oudheusden P (2015). Global Financial Inclusion Database International Monetary Fund.

Greenfield RL, Yeager LB (1986) Competitive payments systems: comment. Am Econ Rev 76(4):848–849

IMF (2015). International Financial Statistics. Available at http://data.imf.org/

International Telecommunication Union (2015). World Telecommunication/ICT Development Report and Database.

IOSCO (2017). Research Report on Financial Technologies (Fintech). Technical report, International Organization of Securities Commissions. https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD554.pdf . Accessed 01 Jan 2018.

Jack W, Suri T (2014) Risk sharing and transactions costs: evidence from Kenya's mobile money revolution. Am Econ Rev 104(1):183–223

Mas I, Morawczynski O (2009) Designing mobile money services Lessons from M-PESA. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 4(2):77–91. https://doi.org/10.1162/itgg.2009.4.2.77

Pearlman, Leon (2017). Distributed Ledger Technologies and Financial Inclusion. Technical report, International Telecommunications Union. http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-T/focusgroups/dfs/Documents/201703/ITU_FGDFS_Report-on-DLT-and-Financial-Inclusion.pdf . Accessed 01 Jan 2018.

Santomero AM, Seater JJ (1996) Alternative monies and the demand for Media of Exchange. J Money Credit Bank 28(4):942–960. https://doi.org/10.2307/2077930

Selgin GA (1988) The theory of free banking: money supply under competitive note issue. In: Rowman & Littlefield pub Inc

Shy O and Tarkka J (1998). The market for electronic cash cards. Research Discussion Paper 21/1998, Bank of Finland. https://helda.helsinki.fi/bof/bitstream/handle/123456789/7682/87446.pdf . Accessed 1 Jan 2018.

White LH (1986) Competitive payments systems: reply. Am Econ Rev 76(4):850–853

White LH (1984a) Competitive payments systems and the unit of account. Am Econ Rev 74(4):699–712

White LH (1984b) Free banking in Britain: theory, experience, and debate, 1800–1845. Cambridge University Press, New York

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the anonymous referees for their useful suggestions.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the sources’ repositories. For the share of persons above 15 years old that have an account at a financial institution in a country, see World Bank’s Financial Inclusion Data / Global Findex at http://datatopics.worldbank.org/financialinclusion/ ; for the number of mobile cellular subscriptions per 100 people, see ITU’s World Telecommunication/ICT Development Report https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx ; for cash in circulation outside banks and broad money series, see CPMI’s Red Book statistics at https://www.bis.org/statistics/payment_stats.htm .

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Central Bank of Brazil, Department of Banking Operations and Payments System’s Research Division, SBS quadra 3, Bloco B, Edificio-Sede, 15 andar, Brasilia, DF, 70074-900, Brazil

Daniel Gersten Reiss

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniel Gersten Reiss .

Ethics declarations

Authors' information.

The views expressed herein are of my own and do not necessarily represent those of the Central Bank of Brazil.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Reiss, D.G. Is money going digital? An alternative perspective on the current hype. Financ Innov 4 , 14 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-018-0097-x

Download citation

Received : 24 July 2017

Accepted : 04 June 2018

Published : 06 July 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-018-0097-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Digital money

- Digital currency

- Digital financial services

JEL classification

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

Research: Can Money Buy Happiness?

In his quarterly column, Francis J. Flynn looks at research that examines how to spend your way to a more satisfying life.

September 25, 2013

A boy looks at a toy train he received during an annual gift-giving event on Christmas Eve 2011. | Reuters/Jose Luis Gonzalez

What inspires people to act selflessly, help others, and make personal sacrifices? Each quarter, this column features one piece of scholarly research that provides insight on what motivates people to engage in what psychologists call “prosocial behavior” — things like making charitable contributions, buying gifts, volunteering one‘s time, and so forth. In short, it looks at the work of some of our finest researchers on what spurs people to do something on behalf of someone else.

In this column I explore the idea that many of the ways we spend money are prosocial acts — and prosocial expenditures may, in fact, make us happier than personal expenditures. Authors Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton discuss evidence for this in their new book, Happy Money: The Science of Smarter Spending . These behavioral scientists show that you can get more out of your money by following several principles — like spending money on others rather than yourself. Moreover, they demonstrate that these principles can be used not only by individuals, but also by companies seeking to create happier employees and more satisfying products.

According to Dunn and Norton, recent research on happiness suggests that the most satisfying way of using money is to invest in others. This can take a seemingly limitless variety of forms, from donating to a charity that helps strangers in a faraway country to buying lunch for a friend.

Witness Bill Gates and Warren Buffet, two of the wealthiest people in the world. On a March day in 2010, they sat in a diner in Carter Lake, Iowa, and hatched a scheme. They would ask America‘s billionaires to pledge the majority of their wealth to charity. Buffet decided to donate 99 percent of his, saying, “I couldn‘t be happier with that decision.”

And what about the rest of us? Dunn and Norton show how we all might learn from that example, regardless of the size of our bank accounts. Research demonstrating that people derive more satisfaction spending money on others than they do spending it on themselves spans poor and rich countries alike, as well as income levels. The authors show how this phenomenon extends over an extraordinary range of circumstances, from a Canadian college student purchasing a scarf for her mother to a Ugandan woman buying lifesaving malaria medication for a friend. Indeed, the benefits of giving emerge among children before the age of two.

Investing in others can make individuals feel healthier and wealthier, even if it means making yourself a little poorer to reap these benefits. One study shows that giving as little as $1 away can cause you to feel more flush.

Quote Investing in others can make you feel healthier and wealthier, even if it means making yourself a little poorer.

Dunn and Norton further discuss how businesses such as PepsiCo and Google and nonprofits such as DonorsChoose.org are harnessing these benefits by encouraging donors, customers, and employees to invest in others. When Pepsi punted advertising at the 2010 Superbowl and diverted funds to supporting grants that would allow people to “refresh” their communities, for example, more public votes were cast for projects than had been cast in the 2008 election. Pepsi got buzz, and the company‘s in-house competition also offering a seed grant boosted employee morale.

Could this altruistic happiness principle be applied to one of our most disputed spheres — paying taxes? As it turns out, countries with more equal distributions of income also tend to be happier. And people in countries with more progressive taxation (such as Sweden and Japan) are more content than those in countries where taxes are less progressive (such as Italy and Singapore). One study indicated that people would be happier about paying taxes if they had more choice as to where their money went. Dunn and Norton thus suggest that if taxes were made to feel more like charitable contributions, people might be less resentful having to pay them.

The researchers persuasively suggest that the proclivity to derive joy from investing in others may well be just a fundamental component of human nature. Thus the typical ratio we all tend to fall into of spending on self versus others — ten to one — may need a shift. Giving generously to charities, friends, and coworkers — and even your country — may well be a productive means of increasing well-being and improving our lives.

Research selected by Francis Flynn, Paul E. Holden Professor of Organizational Behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom .

Explore More

Lose yourself: the secret to finding flow and being fully present, speak your truth: why authenticity leads to better communication, a dozen of our favorite insights stories of 2021, editor’s picks.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Reading Materials

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

- Search Menu

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A12 - Relation of Economics to Other Disciplines

- A14 - Sociology of Economics

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B41 - Economic Methodology

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C18 - Methodological Issues: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C38 - Classification Methods; Cluster Analysis; Principal Components; Factor Models

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C59 - Other

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C80 - General

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- C83 - Survey Methods; Sampling Methods

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- D04 - Microeconomic Policy: Formulation; Implementation, and Evaluation

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F01 - Global Outlook

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F52 - National Security; Economic Nationalism

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F61 - Microeconomic Impacts

- F63 - Economic Development

- F66 - Labor

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- H27 - Other Sources of Revenue

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- H43 - Project Evaluation; Social Discount Rate

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- H57 - Procurement

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H60 - General

- H61 - Budget; Budget Systems

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H83 - Public Administration; Public Sector Accounting and Audits

- H84 - Disaster Aid

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I0 - General

- I00 - General

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I22 - Educational Finance; Financial Aid

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- I25 - Education and Economic Development

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- J08 - Labor Economics Policies

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J10 - General

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J17 - Value of Life; Forgone Income

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J48 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J58 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J88 - Public Policy

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- K23 - Regulated Industries and Administrative Law

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K34 - Tax Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K40 - General

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics: Industrial Structure and Structural Change; Industrial Price Indices

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L20 - General

- L23 - Organization of Production

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- L52 - Industrial Policy; Sectoral Planning Methods

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L94 - Electric Utilities

- L97 - Utilities: General

- L98 - Government Policy

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M53 - Training

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N35 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N55 - Asia including Middle East

- N57 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- N77 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- O19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International Organizations

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O20 - General

- O22 - Project Analysis

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- O24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange Policy

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- O38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O55 - Africa

- O57 - Comparative Studies of Countries

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P14 - Property Rights

- Browse content in P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- P26 - Political Economy; Property Rights

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P30 - General

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P43 - Public Economics; Financial Economics

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q0 - General

- Q01 - Sustainable Development

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q10 - General

- Q12 - Micro Analysis of Farm Firms, Farm Households, and Farm Input Markets

- Q13 - Agricultural Markets and Marketing; Cooperatives; Agribusiness

- Q14 - Agricultural Finance

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q16 - R&D; Agricultural Technology; Biofuels; Agricultural Extension Services

- Q17 - Agriculture in International Trade

- Q18 - Agricultural Policy; Food Policy

- Browse content in Q2 - Renewable Resources and Conservation

- Q25 - Water

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q33 - Resource Booms

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q43 - Energy and the Macroeconomy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q52 - Pollution Control Adoption Costs; Distributional Effects; Employment Effects

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Q57 - Ecological Economics: Ecosystem Services; Biodiversity Conservation; Bioeconomics; Industrial Ecology

- Q58 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- R13 - General Equilibrium and Welfare Economic Analysis of Regional Economies

- R14 - Land Use Patterns

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R20 - General

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- R28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R40 - General

- R41 - Transportation: Demand, Supply, and Congestion; Travel Time; Safety and Accidents; Transportation Noise

- R48 - Government Pricing and Policy

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R52 - Land Use and Other Regulations

- Browse content in Y - Miscellaneous Categories

- Y8 - Related Disciplines

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- About The World Bank Research Observer

- About the World Bank

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Some background on mobile money and its role in financial inclusion, the economics of mobile money: the micro-view, empirical research, mobile money and the economy: a review of the evidence.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Janine Aron, Mobile Money and the Economy: A Review of the Evidence, The World Bank Research Observer , Volume 33, Issue 2, August 2018, Pages 135–188, https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lky001

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Mobile money is a recent innovation that provides financial transaction services via mobile phone, including to the unbanked global poor. The technology has spread rapidly in the developing world, “leapfrogging” the provision of formal banking services by solving the problems of weak institutional infrastructure and the cost structure of conventional banking. This article examines the evolution of mobile money and its important role in widening financial inclusion. It explores the channels of economic influence of mobile money from a micro perspective, and critically reviews the empirical literature on the economic impact of mobile money. The evidence convincingly suggests that mobile money fosters risk-sharing, but direct evidence of the promotion of welfare and saving is still mostly rather less robust.

“ Leapfrog ”: to improve a position by going past others quickly or by missing some stages of an activity or process.” [Cambridge Business English Dictionary, CUP]

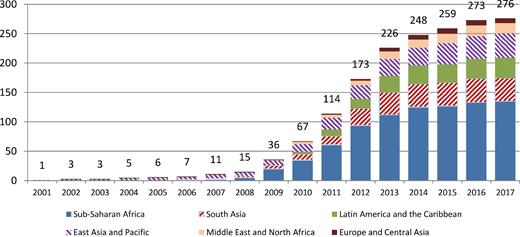

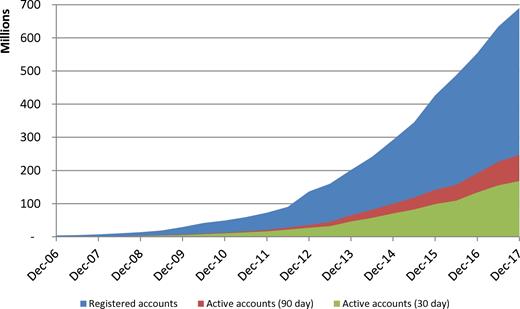

Mobile money is novel : it was barely heard of a decade ago. 1 Yet it has transformed the landscape of financial inclusion, spreading rapidly in developing and emerging market countries (see figure 1 ), and “leapfrogging” the provision of formal banking services. The poor are especially vulnerable to risk (e.g., from illness, unemployment, death of family members, or natural disasters). Enhancing financial inclusion of the unbanked urban and rural poor—a goal of the G20 group of countries—can help to diversify risk. Financial inclusion policy has focused on extending access to formal banking services, but progress has been thwarted by cost and market failure challenges.

Number of Live Mobile Money Services for the Unbanked by Region

Source : Data from the GSMA State of the Industry Report ( 2017 ).

Note : The first mobile money system was launched in the Philippines in 2001, and M-Pesa was launched in 2007.

The new technology helps overcome problems from weak institutional infrastructure and the cost structure of conventional banking. Small size, volatility, informality, and poor governance place constraints on the commercial viability of financial institutions in developing countries ( Beck and Cull 2013 ), see figure 2 . The poor mostly cannot afford the minimum balance requirements and regular charges of typical bank accounts. Mobile phone technology has the advantage that consumers themselves invest in a mobile phone handset, while the (scalable) infrastructure is already in place for the widespread distribution of airtime through secure network channels (see figure 3 ). By adopting mobile money, under-served citizens gain a secure means of transfer and payment at a lower cost, and safe and private storage of funds. Mobile money has filled a lacuna, and has “changed the economics of small accounts” ( Veniard 2010 ). 2

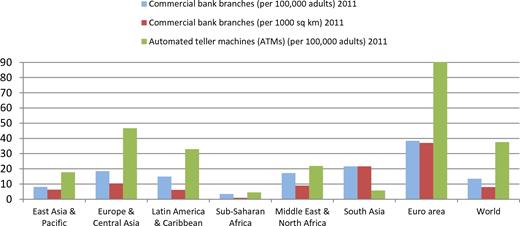

Provision of Banking Infrastructure

Source : G20 Financial Inclusion Indicators database, World Bank and IMF Financial Access Survey.

Note : This shows the position shortly after the adoption of mobile money in Kenya.The first five regions refer to “developing only”.

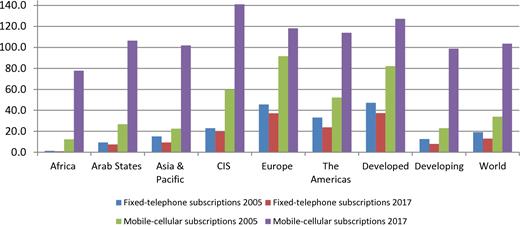

Fixed Telephone and Mobile-cellular Subscriptions: 2005 and 2017

Source : ITU World Telecommunication, ICT Indicators database.

Note : Subscriptions are per 100 inhabitants. “Mobile phone subscribers” refer to active SIM cards rather than individual subscribers.

The technological innovation has helped ameliorate the perennial asymmetric information constraint faced by conventional banks in lending to the collateral-less poor. 3 The movement of cash into electronic accounts gives a record, for the first time for the unbanked, of the history of their financial transactions in real time. By using algorithms, these records can provide evolving individual credit scores for the unbanked. 4 After a designated period of usage and once a score is available, registered users of mobile money may obtain a pathway to formal banking services accessed only through a mobile phone: to interest-bearing savings accounts that can protect assets; to credit extension to invest in livelihoods; and insurance products that reduce risk.

Apart from reducing asymmetric information, the impact of enhancing transparency through electronic records is far-reaching. Tax collection could be improved by the rise of more visible spending, quite apart from the greater ease of tax collection via mobile money payments. The increased transparency of records protects customers’ rights and fosters trust in business, promoting the growth of efficient payments networks. Mobile money should make international transactions more readily traceable and therefore facilitate identification and better control of money laundering. If the high cost of remittances were reduced by mobile money, this could attract more official remittances, and re-channel “informal” remittances through official channels, raising recorded remittances. 5 In essence, mature mobile money systems and the records they produce help foster the “formalization” of the economy, integrating informal sector users into business networks, formal banking and insurance, and linking them to government through social security, tax, and secure wages payments. However, there are legal data privacy considerations concerning access to and use of mobile money records which have barely begun to be addressed.

The channels through which mobile money can affect the economy are many and complex, and not necessarily well-understood. A burgeoning body of empirical literature has attempted to quantify the possible economic gains for different countries of access to secure financial services through mobile money (e.g., improved risk-sharing, food security, consumption, business profitability, saving, and use of cash transfers), and the factors driving the adoption of mobile money. Demonstrating welfare and risk-sharing gains from mobile money across countries could bolster the case for significant government and donor support, as well as investment.

Unfortunately, interpreting the evidence on the economic impact of mobile money is not straightforward. The empirical literature is burdened by a range of sometimes serious problems with data, methodology, and identification, which some authors underestimate or choose to ignore. Work on mobile money faces “selection” problems since both the “roll-out” of mobile money by Mobile Network Operators (MNO) and their agents and the adoption or usage of mobile money by individuals may be influenced by other factors such as education, wealth, and changes in technology preference. There is mixed success using various methods and data sets in dealing with the resultant ambiguous causality. Although various studies establish statistically significant relationships, they frequently do not test the robustness of their results to different model specifications, measurement errors, and bias due to the possible omission of variables. Furthermore, in practice it is difficult to generalize from these models.

This article introduces the phenomenon of mobile money and its role in financial inclusion. It examines possible channels for the economic influence of mobile money, and reviews the new empirical literature on mobile money, both to obtain a better understanding of the linkages involved and to critically assess the sometimes strong claims made by the authors. Lessons are distilled for improved practice in the future empirical analysis of mobile money.

In economies with deep financial markets like the United States, mobile payments or transfers are predominantly linked with pre-existing bank accounts; mobile payments are rapidly gaining market share after a slow start, catalyzed by new technology and commercial partnerships (e.g., Apple Pay). This is distinct from mobile money payments or transfers in largely cash-based developing or emerging countries, where most users are unbanked. Yet as mobile money systems evolve and smartphones become ever cheaper in less advanced countries, the range of financial services could expand to link with products managed by formal financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies. This will ultimately blur the distinctions between mobile banking and mobile money. Survey evidence suggests that security concerns about mobile payments have diminished in the United States, shaped by industry efforts to enhance security (e.g., Federal Reserve 2016 ). There may be a technological spillover to less advanced economies, and biometrics may allay security concerns (though there are caveats about their use in poor countries). This could catalyze a transformation to a virtually cashless economy, and possibly a new role for some banks beyond traditional payments. 6

The term “financial inclusion” is of recent vintage, and has gained currency with policymakers, most prominently in the Maya Declaration of 2011, when 80 regulatory institutions from 76 countries collectively endorsed a set of financial inclusion principles. The G20 has backed the Maya declaration, promoted indicators to measure “financial inclusion”, and the G20 Summit in 2017 prominently endorsed digital approaches to financial inclusion. Mainstream definitions of financial inclusion share the goal of participation in the formal financial sector, which has severely constrained progress to inclusion. Until recently, the use of electronic mobile money has not been counted as part of financial inclusion under most definitions. Mobile money's role is seen as a pathway for registered users to formal sector financial inclusion via products (insurance, credit and a bank savings account) accessed through a mobile phone.

Aron (2017) argues that a revised definition of financial inclusion should encompass tiers of semi-formal inclusion, and not focus on comprehensive formal banking sector inclusion. Mobile money has transformed the lives of poor consumers who can hold recorded cash privately in non-bank electronic accounts and perform financial transfers easily and cost effectively. Fast-spreading and cheaper smartphones (and recycled smartphone handsets) potentially offer access to sophisticated features and a spectrum of financial services for huge numbers of illiterate people through well-designed applications ( Villasenor 2013 ). Such users may not embrace the formal sector products even if they become available, for example, if they qualify for credit, the loans may be small and not adequate to purpose, creating a disincentive to participate. Moreover, the actual number of informal users may be far higher than is formally reported. South Asia has close to 90% of the global unregistered mobile money customers, using an over-the-counter (OTC) model where the challenges and costs of establishing identity in registering were circumvented in favor of a drive for early market share ( Scharwatt et al. 2015 ). 7 In practice, the proliferation of mobile money services and the sheer numbers of new users actively signed up has become integral to achieving ambitious targets under the 2011 Maya Declaration. A revised set of G20 indicators in 2016 has raised the prominence of mobile money, reducing the bias to formality.

In box 1 , the Kenyan mobile money system M-Pesa is summarized and serves to explain the “nuts and bolts” of a profitable mobile money system. Instead of bank branches, mobile money systems rely on a large network of agents. These are linked under various contractual arrangements with a parent MNO, usually in partnership with a prudentially-regulated bank. 8 The nature of agent network structures and the design of the individual agent contracts are crucial for the successful development of mobile money systems ( Aron 2017 ). The typical authorized agents of the mobile money services provider are shops or outlets staffed by small business owners. 9 Mobile money systems were initially dominated by domestic money transfers, but have expanded into a broader payments platform for utility bills, rent, taxes, school fees, and retail payments. Business usage is expanding rapidly through special networks for the payment of suppliers, wages payments, and potentially pensions. Government usage for the payment of wages and social security has lagged, though the cost savings or reductions, especially in insecure environments, could be significant.

Kenya's mobile money system originated in 2005 as an experiment for loan payments via mobile phones in micro-credit schemes, in a public-private partnership between DFID (UK), the Kenyan Government, and Vodafone. In March 2007, Safaricom, the Kenyan subsidiary of Vodafone, launched a commercial payments service, M-Pesa, with the slogan “send money home”, exploiting the proliferation of mobile phone ownership. A decade later, there were six operators, though Safaricom controlled 65% of the market. The FinAccess (2013) survey revealed that 67% of the adult population used financial services in 2013 versus 41% in 2009, driven by mobile money. There were 27 million registered M-Pesa customers by 2017, of whom 19 million were (30-day) “active”. M-Pesa revenue grew by 33% to Kshs 55bn (US$536m) in the year to Mar. 2017, over one-quarter of Safaricom's total service revenue. The Bank of Kenya recorded in 2015, for all operators, a monthly value of transactions of Kshs 227.9bn (US $2.2bn), or about one-half of average monthly GDP.

In August, 2014, the National Payment System Regulations were issued under the National Payment System Act, providing a legal framework for mobile money. These regulations formalized and extended prudential and market conduct requirements for mobile money providers as previously articulated in simple letters of no-objection from the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK). The CBK has duties of oversight, inspection, and enforcement. There are mechanisms for consumer protection, redress, and confidentiality of data.

In Kenya, banks and non-banks, including mobile network operators (MNOs), may provide mobile money services. The net deposits from customers have to be invested in prudentially-regulated banks for safe-keeping in “Trust” accounts, which back 100% of the money of the participants in the mobile money service; the banks are required to satisfy fiduciary responsibility in all transactions concerning the Trust funds ( Greenacre and Buckley 2016 ). No investment of Trust funds is allowed; the funds are strictly separated from the service provider's own accounts and safeguarded from claims of its creditors. Safaricom's Trust account interest income is covenanted to charity.

The early agent exclusivity arrangement for M-Pesa was formally outlawed in July 2014; the CBK ordered Safaricom to open the agent network to other operators to improve competition and to lower fees for customers. Interoperability of platforms was implemented in April 2018; before this, users of mobile money services had to affiliate with multiple mobile providers.

By 2017, there were 136,000 M-Pesa agents countrywide (compared with about 2.43 commercial bank branches per 1,000 km 2 in 2013, or 1,410 total branches). Establishing an agency network and the training and payment of agents is a considerable early investment by operators to develop the market. Retail cash agents transact with their own cash and electronic money in their own M-Pesa accounts to meet customer demand. Wholesale agents (banks or non-bank merchants) are allowed higher limits on electronic money stored in their M-Pesa accounts; they perform a liquidity management service for retail agents, who typically transact daily with wholesalers. Retail agents open accounts observing identity checks required by anti-money laundering legislation, and the cash provision function spans in-store cash merchants to street-based merchants. M-Pesa agents are compensated from transaction fees charged to customers.

Mobile phone users purchase a SIM card with the mobile money “app” for their phone, register with a retail agent using a national identity card and acquire an electronic mobile money account. They deposit money into the account by giving cash to the agent, and receive, in return, equivalent value “electronic money” via their mobile phone. To withdraw money, they transfer electronic money via their mobile phone to the cash merchant's mobile money account, and receive cash in return. Electronic money can be transferred instantly from a customer's account to any other individual, whether registered or not, without using formal bank accounts. The transactions are authorized and recorded in real time. A secure text message (SMS) with a code is sent to the recipient, authorizing a retail agent to transfer money from the remitter's account into cash for the designated recipient. The maximum allowed account balance is Ksh 100,000 (US $970), the maximum daily transaction is Ksh 140,000, the maximum per transaction is Ksh 70,000, and the minimum allowed transfer is Ksh1 (US 10cents). The main transactions are non-bank payments services such as buying airtime, paying bills and school fees, and domestic transfers.