Inequality in India Declined During COVID

We use a large, representative panel data set from India with monthly data on household finances to examine the incidence of economic harms during the COVID pandemic. We observe a sharp spike in poverty, peaking during India's sharp but short lockdown. However, there was a striking decrease in income inequality outside the lockdown. There was a smaller decrease in consumption inequality, likely due to consumption smoothing. Evidence supports two mechanisms for the decline in income inequality: the capital income of top-quartile earners covaries more with aggregate income, and demand for labor fell more for higher quartiles.

We thank Satej Soman, Sabareesh Ramachandran, Kaushik Krishna and Mahesh Vyas for help with Consumer Pyramids Household (CPHS) data. We thank Mushfiq Mobarak, Cynthia Kinnan, Matt Notowodigdo, Viral Acharya, Satej Soman, Sabareesh Ramachandran, and seminar participants at the University of Chicago Micro Workshop, IIM Calcutta-NYU Stern India Research Conference, CAFRAL, the CPHS Research Seminar and the University of Chicago Law School for comments. We thank Sabareesh Ramachandran and Satej Soman for assistance with COVID data. Malani acknowledges funding from the Becker-Friedman Institute at the University of Chicago to purchase a subscription to the Consumer Pyramids Household Survey and the support of the Barbara J. and B. Mark Fried Fund at the University of Chicago Law School. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

Mentioned in the News

More from nber.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Inequality in India: A review of levels and trends

Content maybe subject to copyright Report

Citation Count

The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future

Is housing still the business cycle perhaps not, on the effects of the ecb’s funding policies on bank lending and the demand for the euro as an international reserve, the politics of the globalization backlash: sources and implications, the billionaire raj: a journey through india’s new gilded age, capital in the 21st century, explaining international and intertemporal variations in income inequality, global inequality: a new approach for the age of globalization, inequality: what can be done, related papers (5), appraising cross-national income inequality databases : an introduction, a meta-analysis on the relationship between income inequality and economic growth, uneven human capital development in contemporary china: a non-monetary perspective on regional and gender inequality, inequality and growth: reviewing the economic and social impacts, wealth inequality and accumulation, frequently asked questions (10), q1. what have the authors contributed in "wider working paper 2019/42: inequality in india: a review of levels and trends" .

In this paper, the authors focus on the changing nature of inequality and its impact on growth and mobility.

Q2. What is the impact of rising inequality on the mobility of individuals?

While rising inequality may have consequences for political stability and the sustainability of economic growth, it also affects the mobility of individuals.

Q3. What affects the participation of an individual in the labour market?

Identities such as gender, caste, or community affect an individual’s participation in the labour market, in isolation from but also in conjunction with other identities.

Q4. How many children under five were stunted in 2015-16?

In 2015–16, 44 per cent of ST children under five were stunted, compared with 31 per cent of children from general caste households.

Q5. How did the income share of the top one per cent in India decline in the 1980s?

The share of income of the top one per cent reached a high of 21 per cent in the preindependence period, but declined subsequently until the early 1980s to reach six per cent.

Q6. Where has the Gini index of income risen steadily since the mid-1970s?

In Palanpur, which has been surveyed once every decade starting in 1957–58, the Gini index of income has risen steadily since the mid-1970s, from 0.27 in 1974–85 to 0.36 in 2008–09 (Himanshu et al. 2016).

Q7. What is the likely reason for the higher share of wealth held by the top one per cent?

Since estimates from AIDIS exclude information on bullion and durables, the share of wealth held by the top one per cent and top 10 per cent is likely to be higher once these are included.

Q8. How much of the value-added in organized manufacturing has declined after the financial crisis?

While it declined after the financial crisis, it continues to be above 50 per cent of net value-added in organized manufacturing.

Q9. What are some of the questions that are relevant for emerging countries?

Some of these questions are also relevant for emerging countries such as India and China, where rapid growth in per-capita incomes has been accompanied not only by rising income inequality, but also by rising disparities between social and economic groups, and between labour and capital.

Q10. How much of the value-added in organized manufacturing has declined in recent years?

During the same period the share of wages in value-added declined to 10 per cent, and it has remained thereabout in recent years.

Is today’s India more unequal than under British rule?

India’s top 1 percent holds more income today than it did under the British, new research shows. The middle class is the worst affected. Is a tax for the super-rich the answer?

New Delhi, India — In 2014, Narendra Modi swept to power in India with his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) pitching him as an economic reformer who would root out corruption and rescue the aspirations of India’s middle class from the clutches of elites – as well as the hellscape of rising prices and unemployment.

Ten years later, as Modi contests for a rare third term , the gap between rich and poor in India – already significant in 2014 – has widened into a canyon, economic researchers warn. India’s income and wealth inequality have become among the highest in the world, worse than in Brazil, South Africa and the United States, reveals a new study by the World Inequality Lab (WIL).

Keep reading

‘vote jihad’: as modi raises anti-muslim india election pitch, what’s next, missing in action: how two key parties in india’s largest state collapsed, in india’s election, a flash drive, sex abuse videos – and a missing mp, ‘country is doing well’: why jobless young indians are still backing modi.

As India votes in national elections to choose its next government, the research in the recently published The Rise of the Billionaire Raj shows that income inequality in the country is, in fact, worse than it was under British colonial rule. The study was co-authored by Nitin Kumar Bharti from New York University’s Abu Dhabi campus; Lucas Chancel from Harvard Kennedy School; and Thomas Piketty as well as Anmol Somanchi of the Paris School of Economics.

The widening wealth gap in India has emerged as a political flashpoint, with the opposition Congress Party promising that if elected, it will carry out a caste census that it claims will show how traditionally disadvantaged communities have suffered under Modi’s rule.

But just how unequal is India, according to the new research? What are the reasons? And what are the potential solutions?

Worse income inequality than under the British?

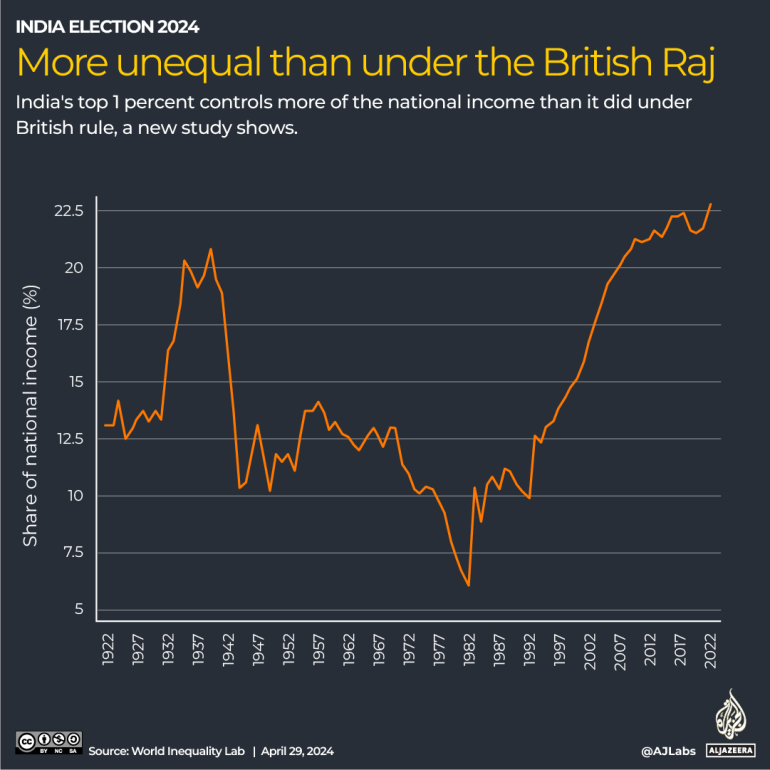

Through much of the 1930s, when the British ruled India – which was known as the crown in the jewel of the empire – the richest 1 percent held just more than 20 percent of the national income. That share dropped during World War II, reaching to just above 10 percent through most of the 1940s, and about 12.5 percent in 1947 when India gained independence.

It hovered there until the late 1960s. Then, as India implemented a series of broadly socialist moves under then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi – payments made to formal princely kingdoms, as compensation to get them to accede were scrapped, and banks were nationalised, among other steps – the national income share of the top 1 percent collapsed to about 6 percent by 1982.

As India liberalised its economy in 1991, things started to change. By the turn of the century, the 1 percent held more than 15 percent of India’s income. By the time Modi came to power in 2014, that figure had crossed 20 percent.

And by 2022-2023, it touched an unprecedented 22.6 percent.

India’s fast-growing economy – its gross domestic product (GDP) is growing by more than 7 percent annually – only appears to be accelerating that gulf, researchers say.

“When the economy grows faster, then a pie growing bigger quickly also leads to increasing inequality,” Bharti, the lead author of the WIL study, told Al Jazeera. “We thought that the free market would take care of it but it has not.”

What about wealth inequality?

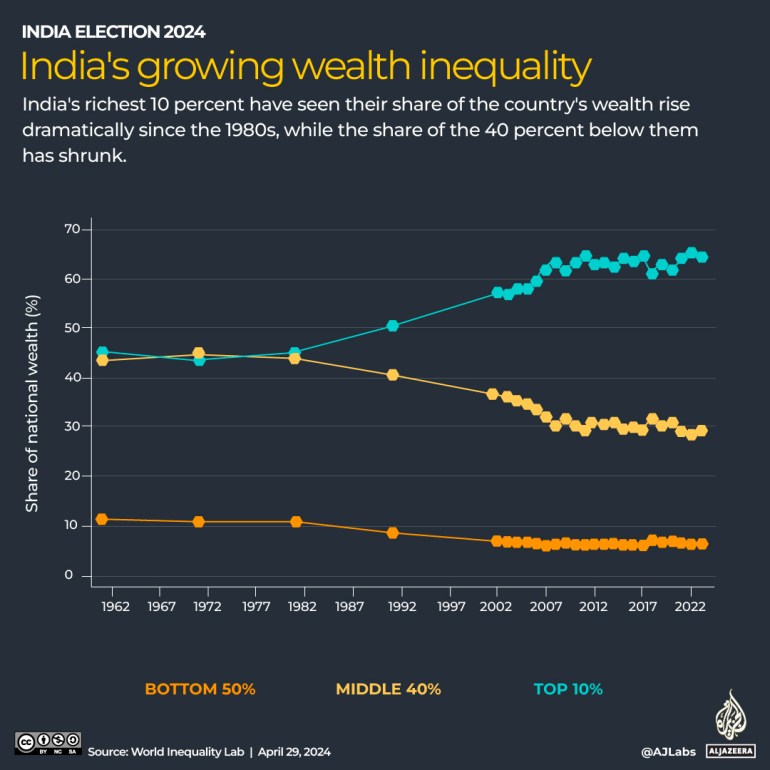

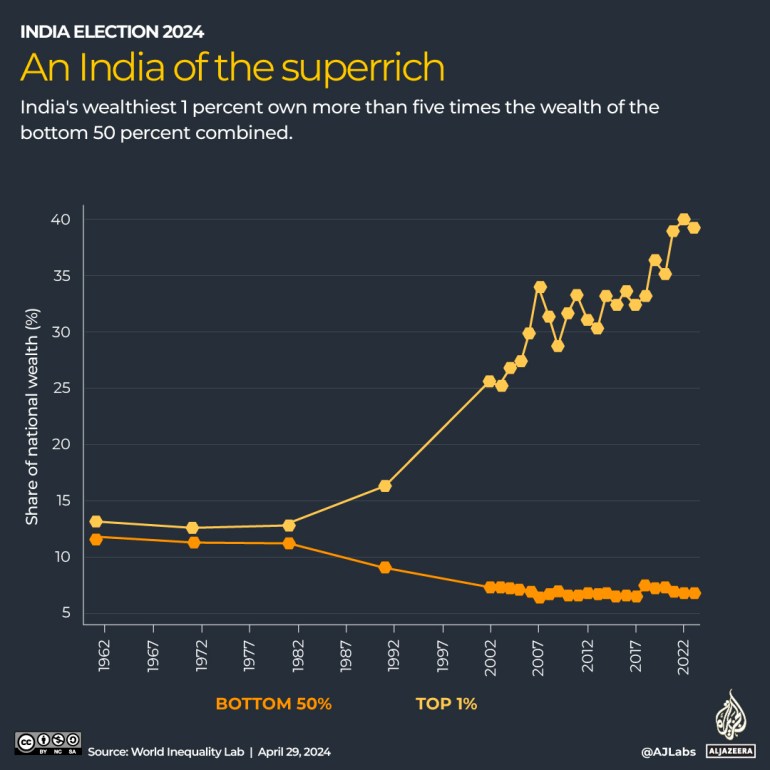

If India’s income inequality is vast, its wealth imbalance is starker . The top 1 percent controlled less than 15 percent of the national wealth in 1961, when the researchers began their analysis. Today, their share is at more than 40 percent.

The richest saw their relative wealth stay mostly static during the pre-liberalisation period, before it took off in 1991, crossing 20 percent before the turn of the century. It stood between 30 and 35 percent when Modi took office – and when the prime minister convinced India that he would deliver them from their economic struggles.

Yet, a decade later, as Modi campaigns for re-election, the mounting inequality suggests that many Indians are struggling as much, if not more, than they were in 2014. Whether that will affect the ongoing election though is unclear, said development economist Jayati Ghosh, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

“It is the same electorate that was addressing the major economic issues until 2014, like corruption, economic stagnation, unemployment, poor livelihood, inadequate public services,” said Ghosh.

But Modi’s campaign, in recent days, has shifted towards religious polarization and strayed far from the economic promises of 2014. For instance, Modi accused the opposition Congress Party of plotting to give Indian Muslims first rights over national resources, and apparently referred to Muslims as “infiltrators”.

“The current regime is obsessed with narratives,” said Ghosh. “The common man is far away from the dark reality.”

Shrinking middle-class income share?

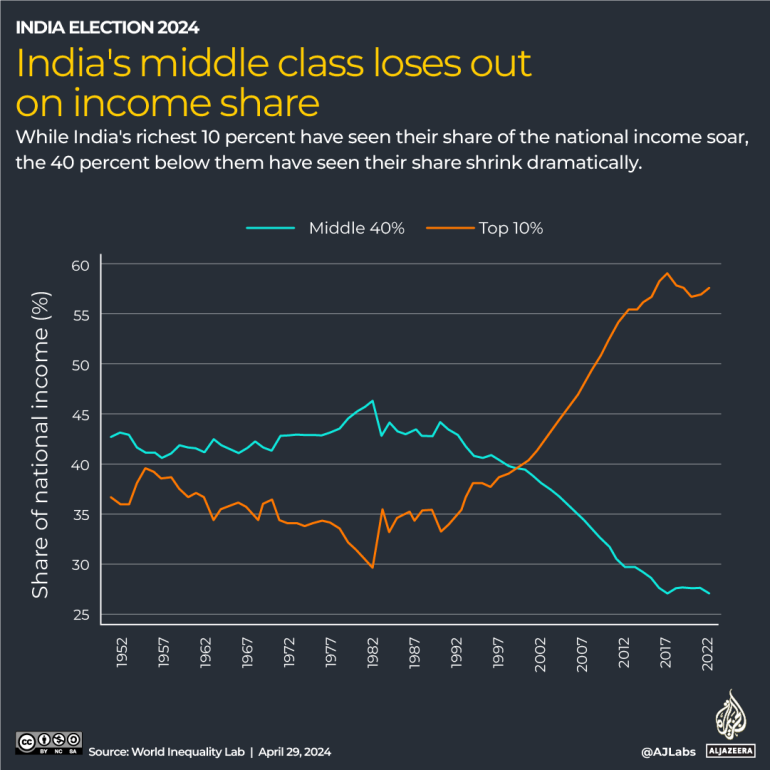

If the top 1 percent hold more than one-fifth of the national income, the top 10 percent control almost 60 percent, the study reveals . In the years after independence, that figure for the top 10 percent had fallen to 30 percent in 1982, before picking up, especially after the 1991 liberalisation measures.

The top 10 percent also hold about 65 percent of the nation’s wealth.

The accumulation of income and wealth in a few hands has come at the cost of the remaining 90 percent. But the data show that it is the middle 40 percent of Indians whose share of national income has shrunk the most, faster than even the bottom 50 percent of the country’s adult population, said Bharti.

The national income share of the middle 40 percent of Indians fell from above 45 percent in the early 1980s to about 27 percent in 2022. For India’s poorest half of the population, the share of national income fell from above 23 percent to 15 percent in this period.

That prospects of relative upward mobility have slowed – not improved – for the Indian middle class is not surprising, experts say.

Rishabh Kumar, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Boston, whose research focuses on historical inequality, underlined that the privatisation of the Indian economy, coupled with globalisation, favoured those with a higher level of education, which allowed them to compete internationally. And in India, that kind of education access has traditionally been skewed towards the wealthy and upper-caste communities.

“The only opportunity for transformation for anyone in the middle class is to play a lottery and get into one of these very few institutions that can propel you to a white-collar job,” Kumar said.

That lottery is paying off for only a few. Consider this: The richest 10,000 Indians have an average income of 480 million rupees ($5.7m) a year – more than 2,000 times the average income of Indians.

The national average income itself, of about 200,000 rupees ($2,400) per year, is misleading, because, as Kumar points out, the new research shows that only individuals on the cusp of entering into the top 10 percent earn that much. “So 90 percent of the population is not even making the GDP per capita of India [the same as the national average income],” Kumar said.

“This paper is a reality check for a lot of Indians about the distribution of goods in the present society,” said Kumar. “And clearly, the rich are benefitted more than the others in India.”

Crazy-rich Indians, desperately-poor Indians

Just how good are things for the very wealthiest of Indians? The rest of the country got a three-day-long peek as many of the world’s top-1-percenters gathered in early March for the pre-wedding celebrations of Anant Ambani, the son of Asia’s richest man Mukesh Ambani , which cost a whopping $120m. The national media gave a detailed breakdown of the meals on offer, dish by dish, which a Guardian writer noted , “even Nero might have thought a little over the top”.

With a private Rihanna concert, where attendees included Bollywood A-listers, Mark Zuckerberg and Ivanka Trump among others, the extravaganza was an exhibition of the dramatically widening income gulf in India.

When India’s economy liberalised in 1991, it had one dollar billionaire. That rose to 52 in 2011, then 162 in 2022, according to the new study. Since then, that number has exploded further to 271 – third behind only China and the US – according to the Hurun Global Rich List for 2024.

Between 2014 and 2022, the net wealth of Indian billionaires grew by more than 280 percent – 10 times faster than the growth in national income over this period, by 27.8 percent, as per the annual Forbes lists of the richest individuals in the world.

On the other hand, India is home to a quarter of all undernourished people worldwide and scored 28.7 out of 100 on the 2023 Global Health Index Severity of Hunger Scale. Between 2019 and 2021, approximately 307 million Indians experienced severe food insecurity (not having enough to eat), while 224 million people were affected by chronic hunger.

The WIL report captures other indicators of India’s sharpening inequality, too: It cites other research that shows how just 1 percent of Indians take 45 percent of all flights in the country; only 2.6 percent of Indians invest in mutual funds; and 6.5 percent of Indians are responsible for 45 percent of all digital payments.

The divide extends to the dining table: 5 percent of users account for a third of all orders on Zomato, India’s largest food delivery app.

The concentration of wealth at the top is a pattern also visible within the top 10 percent, Bharti said. “We see largely similar trends for the top 0.1 percent, top 0.01 percent, and top 0.001 percent,” he said.

Looking back at the BJP’s 2014 poll promises, Bharti said that “what we are actually observing 10 years later in terms of inequality is exactly the opposite of the pitch, with the middle 40 percent losing and the top 1 percent gaining”.

“[The BJP government] has created a small set of the population who are super wealthy where a lot of wealth accumulation is happening,” he added.

Kumar, the associate professor of economics, agreed: “Most of the buyer growth is going to somebody else and much of this growth is very concentrated.” As a result, he said, “we can just see the rich getting richer at a faster pace than everyone else”.

This is leading to a scenario where even the modest dreams many poorer Indians once harboured appear to be in crisis.

“Things that used to be the aspirational purchases of the relatively poor, like a two-wheeler, have stagnated,” said Ghosh, the economist, referring to periods in recent years when sales of scooters and motorcycles have struggled – even as sales of luxury goods, by contrast, appear to have done relatively well.

“That clearly shows the inequality of income and wealth. You are selling Mercedes but not motorcycles.”

Why has inequality worsened?

At least some of the factors driving this deepening income gulf are structural and linked to India’s broader journey since it liberalised its economy in 1991, experts say.

India has struggled to pull the 45 percent of its workforce involved in agriculture towards more productive and better-paying employment, in part because its education system has focused less on them and more on the “tertiary education of elites”, said Bharti.

In essence, Ghosh said, India’s economic boom over the past quarter of a century has been “based on inequality because it just benefitted the top 10 percent while the formal economy has sustained on unpaid and underpaid labour”.

But global events and Indian policies in recent years have also compounded these challenges.

“Unfortunately, three big policy shocks – demonetisation, introduction of GST (Goods and Service Tax) and the COVID-19 lockdown – really hit the informal sector disproportionately,” Ghosh said. “[The Modi government] attacked the livelihood and employment of the dominant part of the workforce with no remedies.”

Demonetisation refers to the overnight announcement by Modi, in 2016, that all high-value current notes would be discontinued. This led to a crisis that hit the small savings of millions of Indians and the liquidity of vast swaths of India’s small-scale industries.

The Modi government introduced a GST in July 2017. And in the spring of 2020, as COVID-19 started spreading, the government imposed a nationwide lockdown that it said was needed to limit the reach of the pandemic – but that cost tens of millions of migrant workers their jobs and crippled small-scale businesses.

The WIL study also observed that the Indian income tax system might be regressive when viewed from the point of view of net wealth – that is, the more wealth taxpayers own, the less taxes they pay as a share of their assets.

So what’s the solution? Eat the rich?

The authors of the WIL study have called for the implementation of a “super tax” of 2 percent on dollar billionaires and multimillionaires as “a tool to fight inequality”, in addition to restructuring the tax schedule to include both income and wealth.

According to Bharti, the solution to inequality lies in education. “India needs to create the right set of human capital depending upon the jobs you want to create and align them,” he said. “[The government] needs to adapt the education system vis-a-vis market or India will keep producing unemployable graduates.”

Meanwhile, the Communist Party of India (CPI) – a small but not insignificant presence in the country’s political landscape – proposed a “wealth tax and inheritance tax” to keep the nature of the economy “more equal, just, and egalitarian” in its 2024 election manifesto.

“Unemployment and price rise have become the biggest woes for the people. BJP’s rule has resulted in unprecedented concentration of wealth at the top while the poor are pushed to destitution,” said the party’s general secretary, D Raja.

The manifesto of the Congress Party, the country’s main opposition, said it was “opposed to monopolies and oligopolies and crony capitalism”, promised to “re-set the economic policy”, and tackle the BJP’s legacy of “job-loss growth”. Yet, after Modi attacked the Congress, suggesting that it wanted to take wealth from families and give it to Muslims, the opposition party has said it has no wealth redistribution plans.

Asim Ali, a political commentator, said a “relative absence of popular movements led by the opposition” allows Modi and the BJP to largely evade questions on inequality by focusing on Hindu majoritarian politics. That is why, “these adverse economic conditions will not necessarily hamper [the BJP] in the coming election”, he said.

To Ghosh, the rising inequality is unsustainable for the Indian economy and society. “I do not think this inequality can continue indefinitely but when it will change – who knows?”

- Fourth International

- Socialist Equality Party

- About the WSWS

Inequality in India greater today than at the height of the British Raj

Wasantha rupasinghe 26 april 2024.

- facebook icon

While hundreds of millions of workers and rural poor in India struggle to make ends meet and some two hundred million people suffer from malnourishment, the income share of India’s wealthiest 1 percent has risen to among the highest anywhere in the world.

According to the latest World Inequality Database Paper on India, which was published last month under the title “Income and wealth inequality in India 1922-2023,” India’s top 1% now gorge on a larger share of the national income than do their counterparts in many of what have hitherto been considered among the world’s most unequal countries, including South Africa, Brazil and the US.

The report was authored by Nitin Kumar Bharti, Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty and Anmol Somanchi, economic experts at World Inequality Lab (WIL). It demonstrates that the fruits of India’s capitalist “rise” over the past three decades have been almost entirely monopolized by the Indian bourgeoisie, the more privileged sections of the middle class, and global capital, while the mass of the population remains mired in squalor, deprivation and extreme economic insecurity.

This constitutes a searing indictment of the entire political establishment and governments at every level—above all the successive Union governments led by the principal parties of Indian big business, the Congress Party and the Hindu supremacist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has held office since 2014.

As the title indicates, the report found that contemporary India, supposedly “the world’s largest democracy,” has higher levels of economic inequality than prevailed at the height of the British Raj, which systematically looted India for the benefit of British-based investors and British imperialism’s wars.

The top 1 percent of India’s population (or 9,223,448 individuals) held 22.6 percent of national income and 40.1 percent of national wealth in 2022-23. Compared to this, the bottom 50 percent (or over 461 million adults) received only 15 percent of India’s national income. The middle 40 percent (or around 369 million adults) had an income share of 27.3 percent. In relation to the share of wealth, the bottom 50 percent owned just 6.4 percent in 2022-23, while the middle 40 percent had 28.6 percent.

To give a sense of the staggering level of income inequality, the report states, “The top 1% earn on average INR (Indian Rupees) 5.3 million (US $63,580), 23 times the national average of INR 0.23 million. Average incomes for the bottom 50% and the middle 40% stood at INR 71,000 (US $853) or 0.3 times national average and INR 165,000 (0.7 times national average) respectively. At the very top of the distribution, the richest 10,000 individuals (of 920 million Indian adults) earn on average INR 480 million (US $5.7 million or 2,069 times the average Indian). To get a sense of just how skewed the distribution is, one would have to be at nearly the 90th percentile to earn the average income in India.”

The following are some of the key figures presented in the report:

*“According to Forbes billionaire rankings, the number of Indians with net wealth exceeding 1 billion US$ at Market Exchange Rate (MER) increased from 1 to 51 to 162 in 1991, 2011 and 2022 respectively. Not only that, the total net wealth of these individuals as a share of India’s net national income boomed from under 1 percent in 1991 to a whopping 25 percent in 2022.” In other words, India’s 162 richest individuals own the equivalent of almost a quarter of India’s net national income.

* “In 2022-23, 22.6% of national income went to just the top 1%, the highest level recorded in our series since 1922, higher than even during the inter-war colonial period. The top 1% wealth share stood at 40.1% in 2022-23, also at its highest level since 1961 when our wealth series begins.”

* “As per the annual Forbes rich list, the net wealth of (US dollar) billionaire Indians has grown by over 280% cumulatively between 2014 and 2022 in real terms, 10 times the growth rate of national income over the same period (27.8%).” The period referred to here corresponds to the first eight years of the Modi-led BJP government, underscoring how its pro-investor policies have massively benefited the super-rich at the expense of the workers and rural toilers.

In 1961, the report found that the wealth share of the top 10 percent of India’s population was 45 percent. During the subsequent two decades, this did not change much, as this was the period when “socialist policies” were at their “peak” causing wealth concentration to be “more-or-less brought to a stand-still.” Contrary to the report’s characterization, the economic policies carried out by Congress-led Indian governments during this period had nothing to do with socialism. They were nationally regulated capitalist policies that kept a state monopoly on certain big corporations in key industries and highly restricted the entry of foreign capital, so as to boost indigenous Indian capitalist development. Those policies led to the enrichment of a tiny super-rich elite at the expense of the vast majority of the population, as underscored by the fact that even during this period, the top 10 percent controlled 45 percent of all national wealth.

However, according to the report, India’ social inequality began to grow sharply with the initiation of pro-investor/pro-market economic reforms in 1991, aimed at attracting international capital and fully integrating India into the US-led world capitalist order. Just over three decades later in 2022, the wealth share of the top 10 percent had reached 63 percent. This demonstrates emphatically that it was the Indian bourgeois that have been the primary beneficiaries of the “open” economic policies carried out by successive governments led by Congress and the BJP since 1991.

The report notes another important factor in the process of growing wealth inequality: “greater financialization of wealth as evidenced from a growing stock market (as a % of GDP).” Giving an example of this, the report noted: “The SENSEX (S&P Bombay Stock Exchange Sensitive Index) a free-float weighted stock market index of 30 companies listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange, grew by 7300% between 1990 and 2023.” What this exposes is that these billionaires, like their counterparts across the world, have pocketed huge amounts of money through speculation on the stock market and the privatization of publicly owned corporations (public sector units) while hardly creating jobs or producing anything of value.

The list of dollar billionaires in India shows the impact of the Modi government’s anti-working class policies. According to the Hurun Global rich list, in 2014, when Modi first came to power, India had 70 dollar billionaires. Today, this number has reached 271, with their combined wealth at $1 trillion. Mukesh Ambani, a leading beneficiary of Modi’s pro-corporate policies and now Asia’s richest person, has increased his wealth to $115 billion from $18 billion in 2014.

According to the Hurun Global Rich List, the city of Mumbai, India’s financial capital, officially surpassed Shanghai (87 billionaires) as the Asian city with the most billionaires, with 92 in 2024. This year’s list marked Mumbai’s entry for the first time into the ranks of the world’s top three billionaire home-city, the report noted.

The report “Income and wealth inequality in India 1922-2023: The Rise of the Billionaire Raj” makes the following comment: “[T]he ‘Billionaire Raj’ headed by India’s modern bourgeoisie is now more unequal than the British Raj headed by the colonial forces.” Then it makes a timely warning to the capitalist elite: “It is unclear how long such inequality levels can sustain without major social and political upheaval.”

They then propose some timid reforms be enacted with the aim of preventing such a social explosion: “While there is no reason to believe income and wealth inequality will slow down by itself,” writes Piketty and his co-authors, “historical evidence suggests that it can be kept in check via policy.” The report proposes implementing a “super tax” on Indian billionaires and multimillionaires, along with restructuring the tax schedule to include both income and wealth, so as “to finance major investments in education, health and other public infrastructure.”

Neither Modi nor the Congress and the other opposition parties, which all represent India’s ravenous ruling elite, will pay any heed to such appeals. On the contrary, they will take all possible measures to further enrich the tiny corporate and financial elite, impoverishing the workers and rural poor. They are bitterly hostile to the multi-million Indian working class and the oppressed, as clearly shown during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ruling class’s “profits before life” policy sacrificed between 5-6 million Indians as the virus was allowed to freely spread to protect the profits of Indian and foreign capital. Modi’s refusal to adopt serious public health measures resulted in the collapse of India’s healthcare system during peak periods of infection and death.

India’s ruling elite also fully endorses the spending of billions to make the country a frontline state in US imperialism’s war preparations against China. While millions struggle to find enough food to eat and die from preventable diseases, India invests huge sums of money in modern weapons of death and destruction.

Such a brutal social system should be ended, and the vast wealth held by the super-rich expropriated. Rather than squandering billions on war and enriching the corporate oligarchy, billions should be directed to satisfy the crying social needs of the impoverished workers and rural poor for decent healthcare, education, and basic social services. This necessitates a struggle for the socialist transformation of society through the establishment of workers’ power.

- Modi banks on venal, right-wing character of opposition to secure third term 17 April 2024

- The Indian ruling class and imperialist powers embrace Modi as he erects a Hindu supremacist state 24 January 2024

- US$152 million “pre-wedding” bash of Asia’s richest man shows contempt of billionaires toward workers and rural poor 21 March 2024

- Modi booster Gautam Adani becomes world’s second richest man amid social misery for Indian working class 5 October 2022

- What capitalism has wrought—India’s tsunami of infections and death, and pandemic of hunger and joblessness 3 June 2021

Main Navigation

- Contact NeurIPS

- Code of Ethics

- Code of Conduct

- Create Profile

- Journal To Conference Track

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Proceedings

- Future Meetings

- Exhibitor Information

- Privacy Policy

NeurIPS 2024

Conference Dates: (In person) 9 December - 15 December, 2024

Homepage: https://neurips.cc/Conferences/2024/

Call For Papers

Author notification: Sep 25, 2024

Camera-ready, poster, and video submission: Oct 30, 2024 AOE

Submit at: https://openreview.net/group?id=NeurIPS.cc/2024/Conference

The site will start accepting submissions on Apr 22, 2024

Subscribe to these and other dates on the 2024 dates page .

The Thirty-Eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2024) is an interdisciplinary conference that brings together researchers in machine learning, neuroscience, statistics, optimization, computer vision, natural language processing, life sciences, natural sciences, social sciences, and other adjacent fields. We invite submissions presenting new and original research on topics including but not limited to the following:

- Applications (e.g., vision, language, speech and audio, Creative AI)

- Deep learning (e.g., architectures, generative models, optimization for deep networks, foundation models, LLMs)

- Evaluation (e.g., methodology, meta studies, replicability and validity, human-in-the-loop)

- General machine learning (supervised, unsupervised, online, active, etc.)

- Infrastructure (e.g., libraries, improved implementation and scalability, distributed solutions)

- Machine learning for sciences (e.g. climate, health, life sciences, physics, social sciences)

- Neuroscience and cognitive science (e.g., neural coding, brain-computer interfaces)

- Optimization (e.g., convex and non-convex, stochastic, robust)

- Probabilistic methods (e.g., variational inference, causal inference, Gaussian processes)

- Reinforcement learning (e.g., decision and control, planning, hierarchical RL, robotics)

- Social and economic aspects of machine learning (e.g., fairness, interpretability, human-AI interaction, privacy, safety, strategic behavior)

- Theory (e.g., control theory, learning theory, algorithmic game theory)

Machine learning is a rapidly evolving field, and so we welcome interdisciplinary submissions that do not fit neatly into existing categories.

Authors are asked to confirm that their submissions accord with the NeurIPS code of conduct .

Formatting instructions: All submissions must be in PDF format, and in a single PDF file include, in this order:

- The submitted paper

- Technical appendices that support the paper with additional proofs, derivations, or results

- The NeurIPS paper checklist

Other supplementary materials such as data and code can be uploaded as a ZIP file

The main text of a submitted paper is limited to nine content pages , including all figures and tables. Additional pages containing references don’t count as content pages. If your submission is accepted, you will be allowed an additional content page for the camera-ready version.

The main text and references may be followed by technical appendices, for which there is no page limit.

The maximum file size for a full submission, which includes technical appendices, is 50MB.

Authors are encouraged to submit a separate ZIP file that contains further supplementary material like data or source code, when applicable.

You must format your submission using the NeurIPS 2024 LaTeX style file which includes a “preprint” option for non-anonymous preprints posted online. Submissions that violate the NeurIPS style (e.g., by decreasing margins or font sizes) or page limits may be rejected without further review. Papers may be rejected without consideration of their merits if they fail to meet the submission requirements, as described in this document.

Paper checklist: In order to improve the rigor and transparency of research submitted to and published at NeurIPS, authors are required to complete a paper checklist . The paper checklist is intended to help authors reflect on a wide variety of issues relating to responsible machine learning research, including reproducibility, transparency, research ethics, and societal impact. The checklist forms part of the paper submission, but does not count towards the page limit.

Supplementary material: While all technical appendices should be included as part of the main paper submission PDF, authors may submit up to 100MB of supplementary material, such as data, or source code in a ZIP format. Supplementary material should be material created by the authors that directly supports the submission content. Like submissions, supplementary material must be anonymized. Looking at supplementary material is at the discretion of the reviewers.

We encourage authors to upload their code and data as part of their supplementary material in order to help reviewers assess the quality of the work. Check the policy as well as code submission guidelines and templates for further details.

Use of Large Language Models (LLMs): We welcome authors to use any tool that is suitable for preparing high-quality papers and research. However, we ask authors to keep in mind two important criteria. First, we expect papers to fully describe their methodology, and any tool that is important to that methodology, including the use of LLMs, should be described also. For example, authors should mention tools (including LLMs) that were used for data processing or filtering, visualization, facilitating or running experiments, and proving theorems. It may also be advisable to describe the use of LLMs in implementing the method (if this corresponds to an important, original, or non-standard component of the approach). Second, authors are responsible for the entire content of the paper, including all text and figures, so while authors are welcome to use any tool they wish for writing the paper, they must ensure that all text is correct and original.

Double-blind reviewing: All submissions must be anonymized and may not contain any identifying information that may violate the double-blind reviewing policy. This policy applies to any supplementary or linked material as well, including code. If you are including links to any external material, it is your responsibility to guarantee anonymous browsing. Please do not include acknowledgements at submission time. If you need to cite one of your own papers, you should do so with adequate anonymization to preserve double-blind reviewing. For instance, write “In the previous work of Smith et al. [1]…” rather than “In our previous work [1]...”). If you need to cite one of your own papers that is in submission to NeurIPS and not available as a non-anonymous preprint, then include a copy of the cited anonymized submission in the supplementary material and write “Anonymous et al. [1] concurrently show...”). Any papers found to be violating this policy will be rejected.

OpenReview: We are using OpenReview to manage submissions. The reviews and author responses will not be public initially (but may be made public later, see below). As in previous years, submissions under review will be visible only to their assigned program committee. We will not be soliciting comments from the general public during the reviewing process. Anyone who plans to submit a paper as an author or a co-author will need to create (or update) their OpenReview profile by the full paper submission deadline. Your OpenReview profile can be edited by logging in and clicking on your name in https://openreview.net/ . This takes you to a URL "https://openreview.net/profile?id=~[Firstname]_[Lastname][n]" where the last part is your profile name, e.g., ~Wei_Zhang1. The OpenReview profiles must be up to date, with all publications by the authors, and their current affiliations. The easiest way to import publications is through DBLP but it is not required, see FAQ . Submissions without updated OpenReview profiles will be desk rejected. The information entered in the profile is critical for ensuring that conflicts of interest and reviewer matching are handled properly. Because of the rapid growth of NeurIPS, we request that all authors help with reviewing papers, if asked to do so. We need everyone’s help in maintaining the high scientific quality of NeurIPS.

Please be aware that OpenReview has a moderation policy for newly created profiles: New profiles created without an institutional email will go through a moderation process that can take up to two weeks. New profiles created with an institutional email will be activated automatically.

Venue home page: https://openreview.net/group?id=NeurIPS.cc/2024/Conference

If you have any questions, please refer to the FAQ: https://openreview.net/faq

Ethics review: Reviewers and ACs may flag submissions for ethics review . Flagged submissions will be sent to an ethics review committee for comments. Comments from ethics reviewers will be considered by the primary reviewers and AC as part of their deliberation. They will also be visible to authors, who will have an opportunity to respond. Ethics reviewers do not have the authority to reject papers, but in extreme cases papers may be rejected by the program chairs on ethical grounds, regardless of scientific quality or contribution.

Preprints: The existence of non-anonymous preprints (on arXiv or other online repositories, personal websites, social media) will not result in rejection. If you choose to use the NeurIPS style for the preprint version, you must use the “preprint” option rather than the “final” option. Reviewers will be instructed not to actively look for such preprints, but encountering them will not constitute a conflict of interest. Authors may submit anonymized work to NeurIPS that is already available as a preprint (e.g., on arXiv) without citing it. Note that public versions of the submission should not say "Under review at NeurIPS" or similar.

Dual submissions: Submissions that are substantially similar to papers that the authors have previously published or submitted in parallel to other peer-reviewed venues with proceedings or journals may not be submitted to NeurIPS. Papers previously presented at workshops are permitted, so long as they did not appear in a conference proceedings (e.g., CVPRW proceedings), a journal or a book. NeurIPS coordinates with other conferences to identify dual submissions. The NeurIPS policy on dual submissions applies for the entire duration of the reviewing process. Slicing contributions too thinly is discouraged. The reviewing process will treat any other submission by an overlapping set of authors as prior work. If publishing one would render the other too incremental, both may be rejected.

Anti-collusion: NeurIPS does not tolerate any collusion whereby authors secretly cooperate with reviewers, ACs or SACs to obtain favorable reviews.

Author responses: Authors will have one week to view and respond to initial reviews. Author responses may not contain any identifying information that may violate the double-blind reviewing policy. Authors may not submit revisions of their paper or supplemental material, but may post their responses as a discussion in OpenReview. This is to reduce the burden on authors to have to revise their paper in a rush during the short rebuttal period.

After the initial response period, authors will be able to respond to any further reviewer/AC questions and comments by posting on the submission’s forum page. The program chairs reserve the right to solicit additional reviews after the initial author response period. These reviews will become visible to the authors as they are added to OpenReview, and authors will have a chance to respond to them.

After the notification deadline, accepted and opted-in rejected papers will be made public and open for non-anonymous public commenting. Their anonymous reviews, meta-reviews, author responses and reviewer responses will also be made public. Authors of rejected papers will have two weeks after the notification deadline to opt in to make their deanonymized rejected papers public in OpenReview. These papers are not counted as NeurIPS publications and will be shown as rejected in OpenReview.

Publication of accepted submissions: Reviews, meta-reviews, and any discussion with the authors will be made public for accepted papers (but reviewer, area chair, and senior area chair identities will remain anonymous). Camera-ready papers will be due in advance of the conference. All camera-ready papers must include a funding disclosure . We strongly encourage accompanying code and data to be submitted with accepted papers when appropriate, as per the code submission policy . Authors will be allowed to make minor changes for a short period of time after the conference.

Contemporaneous Work: For the purpose of the reviewing process, papers that appeared online within two months of a submission will generally be considered "contemporaneous" in the sense that the submission will not be rejected on the basis of the comparison to contemporaneous work. Authors are still expected to cite and discuss contemporaneous work and perform empirical comparisons to the degree feasible. Any paper that influenced the submission is considered prior work and must be cited and discussed as such. Submissions that are very similar to contemporaneous work will undergo additional scrutiny to prevent cases of plagiarism and missing credit to prior work.

Plagiarism is prohibited by the NeurIPS Code of Conduct .

Other Tracks: Similarly to earlier years, we will host multiple tracks, such as datasets, competitions, tutorials as well as workshops, in addition to the main track for which this call for papers is intended. See the conference homepage for updates and calls for participation in these tracks.

Experiments: As in past years, the program chairs will be measuring the quality and effectiveness of the review process via randomized controlled experiments. All experiments are independently reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Financial Aid: Each paper may designate up to one (1) NeurIPS.cc account email address of a corresponding student author who confirms that they would need the support to attend the conference, and agrees to volunteer if they get selected. To be considered for Financial the student will also need to fill out the Financial Aid application when it becomes available.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

INEQUALITY IN INDIA, 1922-2023: THE RISE OF THE BILLIONAIRE RAJ WORKING PAPER N°2024/09 ... 3 Paris School of Economics and World Inequality Lab March 18, 2024 Abstract ... for Research (ANR-17-EUR-0001), ERC Synergy DINA 856455 and WISE Horizon 101095219 research grants. Lucas

Economic Inequalit y. The top 10% of Indians, on average, made 96 times more money than the bottom 50%, according to the World Inequality Report 2022. Similar t o this, Oxfam International ...

The study of income inequality and income mobility has been central to understanding India's recent economic development. This paper, based on the first two waves of the India Human Development ...

The growing research on inequality has gained very much importance in recent years, especially after the repeated commitment on the Government's part to eradicate poverty and existing inequalities from India. But in the study of income inequality, India lacks a detailed caste-wise survey by any government or non-government organization. The ...

A considerable body of research on inequality in India has focused on consumption inequality. This article compares inequality in consumption expenditure and income, using two waves of the India Human Development Survey. We find that while income inequality increased marginally, expenditure inequality remained stable.

May 2019. Abstract: This paper contributes to the literature by reviewing levels, trends, and structure of inequality since the early 1990s in India. It draws extensively on the existing literature, supplemented with analyses of multiple data sources, to paint a picture.

ECONOMIC INEQUALITY IN INDIA: RIEF NALYSIS I 5 | WEALTH INEQUALITY The distribution of wealth5 provides a complementary perspective on consumption and income inequality. The Gini coefficient for wealth has witnessed the highest increase among all other indicators, from 0.67 in 2001-02 to 0.75 for 2012 (Figure 1).

The paper presents estimates of poverty [extreme poverty PPP .9 and PPP$3.2] and consumption inequality in India for each of the years 2004-5 through the pandemic year 2020-21. These estimates include, for the first time, the effect of in-kind food subsides on poverty and inequality. Extreme poverty was as low as 0.8 percent in the pre-pandemic year 2019, and food transfers were instrumental ...

Inequality and Poverty in India: Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic and Policy Response Elif Arbatli-Saxegaard, Mattia Coppo, Nasser Khalil, Shinya Kotera, and D. Filiz Unsal WP/23/147 IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working ...

We contribute by examining poverty and, in particular, inequality in India during the pandemic using a large, representative, panel data set of roughly 197,000 households (990thousand members)with monthlydatafromJanuary2015-July2021. Weexplorethe mechanisms—some similar to those in the U.S.—responsible for the shifts in inequality in India.

The debate about trade-off between growth and equity has always been a cornerstone of economics, and while the root of the studies on income inequality is found in Kuznets' paper, 'Economic Growth and Income Inequality', the relationship has been tested and verified across time and countries by many studies.Even the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have recognised the presence ...

DOI 10.3386/w29597. Issue Date December 2021. We use a large, representative panel data set from India with monthly data on household finances to examine the incidence of economic harms during the COVID pandemic. We observe a sharp spike in poverty, peaking during India's sharp but short lockdown. However, there was a striking decrease in ...

economic migrants to other regions of India. We focus our paper on the extent to which such large within-country locational differences existing inequality in can account for India. 3. Our main question is simple: how much of the variation in living standards in India can be explained solely based on location?

To mark the magnitude of income and wealth inequality challenges in India it is worth examining the. Forbes Billionair es Report 2 022, according to which the 10th richest person in the world ra ...

Th is paper analyses the nature and causes of the patterns of inequality and poverty in India. Since the economic liberalization in the early 1990s, the evidence suggests increasing inequality (in ...

Reckoning economic inequality in India has always been fraught with challenges because of non-availability of personal income data. In lieu of income data, survey data on reported consumption expenditure at the household level, periodically collected by India's National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), have been used to reckon economic inequality in India for long.

This research paper on "Wealth and Income inequality in India" dives into the difficult subject of diversity ... Income inequality and economic growth in India: Evidence from panel data analysis. Journal of Economic Development, 47(1), 35-54, uses panel data analysis to study the link between income inequality and economic development in India. ...

Abstract: This paper contributes to the literature by reviewing levels, trends, and structure of inequality since the early 1990s in India.It draws extensively on the existing literature, supplemented with analyses of multiple data sources, to paint a picture. It notes where different data sources suggest conflicting conclusions that reflect both data challenges and the complexity of the ...

This paper presented a comprehensive literature review of the relationship between income inequality and economic growth. In the theoretical literature, various transmission mechanisms were identified in which income inequality is linked to economic growth, namely the level of economic development, the level of technological development, social ...

In this regard, we build an open economy dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model with both informality and gender in-equality in the labor market. The model is estimated using Bayesian techniques and applied to quarterly data from India. The key contribution of this paper is to link the issue of gender inequality to informality within

This study presents the first in-depth analysis of spatial differences and factors influencing wealth distribution among households in India. It uses data from the latest National Family Health Survey, covering 707 districts. Techniques like the Lorenz curve, Gini coefficient, Location Quotient, Morans statistics, and Univariate and Bivariate LISA methods explore inequalities, concentration ...

The Indian Economic Journal. The Indian Economic Journal provides economists and academicians an exclusive forum for publishing their work pertaining to theoretical understanding of economics as well as empirical policy analysis of economic issues in broader context. View full journal description. This journal is a member of the Committee on ...

The WIL report captures other indicators of India's sharpening inequality, too: It cites other research that shows how just 1 percent of Indians take 45 percent of all flights in the country ...

Abstract: Increasing economic inequality has become a cause of concern for the developing. countries like India, where economic growth and income inequality go hand in hand. The benefits of New ...

This paper examines the implications of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and automation for the taxation of labor and capital in advanced economies. It synthesizes empirical evidence on worker displacement, productivity, and income inequality, as well as theoretical frameworks for optimal taxation.

French economist Thomas Piketty, along with a few other economists, recently came out with some startling findings on economic inequality trends in India over the last century. In Income and ...

But if economic growth is to last, these deep-seated deficiencies must be addressed. Start with the lack of demand. Though India's gdp is $3.7trn, just 60m of its people earn over $10,000 a year ...

India, highlighting the economic, social, and political costs associated with gender disparities. Fourthly, to study about that what are the solutions to reduce the ineq uality in India. Hypothesis

The top 1 percent of India's population gorged on 22.6 percent of national income and 40.1 percent of national wealth in 2022-23.

Social and economic aspects of machine learning (e.g., fairness, interpretability, human-AI interaction, privacy, safety, strategic behavior) ... (LLMs): We welcome authors to use any tool that is suitable for preparing high-quality papers and research. However, we ask authors to keep in mind two important criteria. First, we expect papers to ...