- Medical Library

SNU MEDICINE

- Vision & Mission

- Message from the Dean

- International Partners

- Organization

- Basic Medical Science

- Clinical Science

- Information

- Introduction

- Undergraduate

- Undergraduate Curriculum

- Graduate Curriculum

Research of the Month

- Research Units

- Visiting Student Elective Program

- Campus Housing

- Electives Schedule

- Subject Areas

- The 10th Anniversity of SNU Medicine OIA

Select Translation Language

- Luxembourgish

- Myanmar (Burmese)

- Scots Gaelic

- Haitian Creole

- Azerbaijani

- Chinese (Simplified)

- Chinese (Traditional)

- Kurdish (Kurmanji)

Reaching Beyond Korea to

Become the Leading Medical School in the World

The 76th graduation ceremony of Seoul National University College of Medicine

_1640670234709.jpg)

2022 SNUCM OT and Parents' Day

GSDS-SNUCM Agreement Ceremony on Bachelor's & Master's degree joint course

2021 Webinar for Medical Education during Covid-19 in East Asia

SNU Medical Dream of Nobel Prize and Start-up 2021

SNUCM Professors Retirement Ceremony in August 2021

2021 SNUCM-SNUH Seminar

Seoul-Sydney Research Network Webinar Series one : Autoimmune Disease

Opening Ceremony of Korea Dementia Research Center

15th Anniversary Special Forum on Convergence Research between SNU College of Medicine and College of Engineering

MOU-Naver CLOVA CIC

MOU- KIST BSI

Symposium on the Establishment of Department of Medical Device Development

SNUCM symbolic sculpture unveiling ceremony

Molecular Imaging Center opening ceremony

2021 SNUCM Professors Retirement Ceremony(2021-03-08)

Research of the Month, February, 2024. The percentage of unnecessary mastectomy due to false size prediction using preoperative ultrasonography and MRI in breast cancer patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a prospective cohort study

The percentage of unnecessary mastectomy due to false size prediction using preoperative ultrasonography and MRI in breast cancer patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a prospective cohort study (유튜브 채널 해당 영상으로 이동)

Research of the Month, January, 2024. Safety and efficacy of a novel anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell product targeting a membrane-proximal domain of CD19 with fast on- and off-rates against non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a first-in-human study

Safety and efficacy of a novel anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell product targeting a membrane-proximal domain of CD19 with fast on- and off-rates against non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a first-in-human study (유튜브 채널 해당 영상으로 이동)

Research of the Month, December, 2023. Substitution with Low-Osmolar Iodinated Contrast Agent to Minimize Recurrent Immediate Hypersensitivity Reaction

Substitution with Low-Osmolar Iodinated Contrast Agent to Minimize Recurrent Immediate Hypersensitivity Reaction (유튜브 채널 해당 영상으로 이동)

Research of the Month, November, 2023. Associations between post-traumatic stress disorders and psychotic symptom severity in adult survivors of developmental trauma: a multisite cross-sectional study in the UK and South Korea

Associations between post-traumatic stress disorders and psychotic symptom severity in adult survivors of developmental trauma: a multisite cross-sectional study in the UK and South Korea. (유튜브 채널 해당 영상으로 이동)

JW LEE Center for Global Medicine

Dedicated to conducting research and capacity building for students and fellows to deliver inclusive services and connect the global community

International Partnership

SNU MEDICINE actively promotes student exchanges and faculty research activities by signing MOUs with overseas Institutions

COVID-19 Updates

Beyond & Ahead

Reaching Beyond Korea to Become the Leading Medical School in the World

Academic Hall Pioneering Medical Research and Practical intellect

Seoul National University College of Medicine

SNU Medicine Future Development Committee Special Leadership Lecture Series

SNUCM Report

QS(Quacquarelli Symonds) 2021 Seoul National University college of Medicine WORLD RANKING

Korea Ranks

World Ranks

RESEARCH PROFILES More

Research Profile

Research Output

ADDITIONAL LINKS

- Privacy Policy

- Map & Directions

103 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu Seoul (03080) TEL : 82-2-740-8114

Copyright©2021 Seoul National University College of Medicine All rights reserved.

South Korea: Healthcare Workforce Education & Training

Medical Graduates Per 100,000 Population (2019): 7.4 Nursing Graduates Per 100,000 Population (2019): 100.2

Source: OECD (2021), Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators , OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ae3016b9-en.

Tuition Fee Per Semester in USD for a Graduate Degree in Medicines: $2,510-$10,960.

Source: Tuition Fees in Korea. Study In Korea, Run By Korean Government. From the web at https://www.studyinkorea.go.kr/en/overseas_info/allnew_tuitionFees.do , last accessed Sept. 14, 2022.

Graduate Tuition Fee Per Semester, Professional Graduate School of Medicine, Seoul National University (2015): 5,340,000 Korean Won ($3,828.81 USD at rate of 0.0007 RKW per USD accessed Sept. 14, 2022 ).

Source: Seoul National University. Academic Resources: Registration . Last accessed Sept. 14, 2022.

“There are 40 medical colleges or schools in the Republic of Korea. Medical students have to fulfill four years of medical education on top of either a two-year premedical course or a four-year bachelor’s degree. The quality of medical education is assured by the Korean Institute of Medical Education and Evaluation (KIMEE). After obtaining a license to practice as a doctor, almost all new doctors start further training to be a medical specialist. To apply for the qualification test for medical specialists, a one-year internship and four-year residency in a specialty (three years for family doctors) are required. “The hospitals or institutes for further medical training are designated by the Minister of Health and Welfare. Following recent advancements in medical knowledge, many associations of specialist doctors offer certifications of subspecialties to qualified specialists. The certification of subspecialty is valid for five years and subject to revalidation to ensure medical competency.”

Source: World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. (2015). Republic of Korea health system review . Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific.

“To become a nurse, nursing students have to fulfill either three or four yours of nursing education. Recently, some nursing departments that once provided three-year nursing education have upgraded themselves to provide four-year nursing education. The quality of nursing education is assessed by the Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing Education (KABONE). “KABONE also designates and evaluates educational institutes for nursing specialists and manages their qualification test. Nurses who have practice experience of at least three years and who have completed a designated education programme for nursing specialists are eligible for the test. The nursing specialist system was first introduced in 2002 with specialties in anaesthetic, public health, home health-care and mental health nursing. Seven specialties including infection control, hospice, and oncology nursing were added to the first batch of nursing specializations in 2006. As of 2012, about 12,800 nurses were qualified as nursing specialists in 13 specialties.”

South Korean Health System Overview Health System Rankings Health System Outcomes Coverage and Costs for Consumers Health System Financing and Expenditures South Korea’s COVID-19 Policy

Healthcare Workers Health System Resources and Utilization Long-Term Care Healthcare Workforce Education & Training Health Information & Communications Technologies Pharmaceuticals

Political System Economic System Population Demographics People With Disabilities Aging Social Determinants & Health Equity Health System History & Challenges

World Health Systems Facts is a project of the Real Reporting Foundation . We provide reliable statistics and other data from authoritative sources regarding health systems and policies in the US and sixteen other nations.

Page last updated October 14, 2023 by Doug McVay, Editor.

We value your privacy

Privacy overview.

Study Medicine in South Korea

Many advantages go with an MD suit, from the ability to make a difference and save lives to the respect, demand, and reasonable salary. There are many unknowns in researching health professional education in Korea, mainly because information about the degrees is in Korean, and it's hard to find anything in English. Thus I've decided to collect all information you need in one place and create a series about Medical degrees in Korea.

Top universities in Korea to study medicine

Here is a list of the best universities in South Korea to study medicine in every aspect. School names are linked to the associated medical department.

- Seoul National University

- Yonsei University

- Sungkyunkwan University (SKKU)

- Korea University

- Hanyang University

Articles and guidelines

Below you can find a list of all articles published on the website and related to studying medicine in Korea as an international student

Sasha Smirnova

Unlocking global talent: an in-depth look at chung-ang university's young scientist scholarship (cayss), how to apply for the cayss scholarship at chung-ang university: a detailed guide, medicine programs in global korea scholarship for graduate students, study biological science in south korea, medicine programs in global korea scholarship for undergraduate students.

Great! You’ve successfully signed up.

Welcome back! You've successfully signed in.

You've successfully subscribed to Student in Korea.

Your link has expired.

Success! Check your email for magic link to sign-in.

Success! Your billing info has been updated.

Your billing was not updated.

Best Global Universities for Clinical Medicine in South Korea

These are the top universities in South Korea for clinical medicine, based on their reputation and research in the field. Read the methodology »

To unlock more data and access tools to help you get into your dream school, sign up for the U.S. News College Compass !

Here are the best global universities for clinical medicine in South Korea

Seoul national university (snu), yonsei university, sungkyunkwan university (skku), university of ulsan, korea university, catholic university of korea, kyungpook national university, kyung hee university, korea advanced institute of science & technology (kaist), pusan national university.

See the full rankings

- Clear Filters

- # 46 in Best Universities for Clinical Medicine (tie)

- # 129 in Best Global Universities (tie)

Seoul National University was founded in 1946. The South Korean national university’s main location is the Gwanak campus... Read More

- # 95 in Best Universities for Clinical Medicine

- # 292 in Best Global Universities (tie)

Yonsei University is a private institution that traces its roots back to 1885, when Christian missionaries founded a... Read More

- # 102 in Best Universities for Clinical Medicine (tie)

- # 263 in Best Global Universities (tie)

Sungkyunkwan University, also known as SKKU, is a private institution that traces its roots back to 1398, when it was... Read More

- # 152 in Best Universities for Clinical Medicine (tie)

- # 710 in Best Global Universities (tie)

- # 256 in Best Universities for Clinical Medicine

- # 290 in Best Global Universities (tie)

Korea University is a private institution that was founded in 1905. Originally called Bosung College, the university... Read More

- # 339 in Best Universities for Clinical Medicine (tie)

- # 1,190 in Best Global Universities (tie)

- # 459 in Best Universities for Clinical Medicine (tie)

- # 667 in Best Global Universities (tie)

- # 473 in Best Universities for Clinical Medicine

- # 520 in Best Global Universities (tie)

- # 492 in Best Universities for Clinical Medicine (tie)

- # 282 in Best Global Universities (tie)

The Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, commonly known as KAIST, is a public institution that was... Read More

- # 517 in Best Universities for Clinical Medicine

- # 698 in Best Global Universities (tie)

SEOUL NATIONAL UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL

- Close language layer

- Find a Doctor

Education & Research

Information.

- Introduction

- Professional Development

- Academic Advancement

- Visiting Students

- JW Lee Center

- Appointment

- Sponsored Program

- Non-sponsored Program

Our observational training offers programs in almost all specialties. Make sure to take a look at the programs of SNUH’s clinical departments by clicking on the links at the bottom of this page.

Please send scanned copies via e-mail : [email protected]

※ We also have education programs for nurses, allied health professionals (AHP), and administrative personnel. Check out below on what are required to be part of the program!

- Main Hospital

- Children's Hospital

- Cancer Hospital

- Language Services

- Billing and Insurance

- General Guideline

- Our Doctors

- IHC Stories

- Outpatient Services

- Inpatient Services

- Emergency services

- Health Screening Programs

- Visa Examinations

- Medical records/certificate

- Homecare service

- For international Patients

- Confirmation

- IHC Location

- Outpatient Guide Map

- Children’s Hospital

- Daehan Center

- Visiting Hours

- Convenient Facilities

- Accommodations Nearby

- Status and Statistics

- Mission and Vision

- One SNUH Network Mission and Vision

- Collaborate with Us

- Bundang Hospital

- Boramae Hospital

- Gangnam Center

- Patient Bill of Rights and Responsibilities

Reform of medical education in Korea

Affiliation.

- 1 Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- PMID: 20163225

- DOI: 10.3109/01421590903197043

There are 41 medical schools in South Korea with over 3500 students graduating from the medical schools annually with the appropriate qualifications to practice medicine. Korean medical educators have made significant efforts to enhance the effectiveness of medical education by preparing students for the rapidly changing global environment of medicine and healthcare. This article outlines the reform efforts made by Korean medical schools to meet such demands, which includes the adoption of student-centered and competency-based education, e-learning, and authentic assessment of clinical performance. It also discusses the recent reform of the medical education system, driven by the Government's policy to prepare Korean higher education for an increasingly knowledge-based society.

- Accreditation / organization & administration

- Clinical Competence

- Computer Systems

- Education, Medical / organization & administration*

- Education, Medical, Continuing / methods

- Educational Measurement

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,920,221 articles, preprints and more)

- Available from publisher site using DOI. A subscription may be required. Full text

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

Reform of medical education in Korea.

Author information, affiliations, orcids linked to this article.

- Kee C | 0000-0002-7419-0316

Medical Teacher , 01 Jan 2010 , 32(2): 113-117 https://doi.org/10.3109/01421590903197043 PMID: 20163225

Abstract

Full text links .

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.3109/01421590903197043

References

Articles referenced by this article (13)

Byun KY, 2006. Future directions of the policies on graduate medical and dental programs. Presented at the workshop on the Implementation of Graduate Medical and Dental Programs, Seoul

Title not supplied.

Korean J Med Educ 2006

Implementation of problem-based learning in Asian medical schools and students' perceptions of their experience.

Med Educ, (5):401-409 2003

MED: 12709180

Kim JJ, 2008. Issues in the current postgraduate medical education system. Proceedings of the 23rd meeting of the Korean Society of Medical Education, Seoul. pp 117–122

Kim k-j, han j, park ib, kee c. 2009. medical education in korea: the e-learning consortium. med teach 31:e397–e401., kohn lt, corrigan jm, donaldson ms, editors, 2000. to err is human: building a safer health system. washington, dc: national academy press, citations & impact , impact metrics, citations of article over time, article citations, teaching cellular architecture: the global status of histology education..

Hortsch M , Girão-Carmona VCC , de Melo Leite ACR , Nikas IP , Koney NK , Yohannan DG , Oommen AM , Li Y , Meyer AJ , Chapman J

Adv Exp Med Biol , 1431:177-212, 01 Jan 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37644293

Comparing South Korea and Italy's healthcare systems and initiatives to combat COVID-19.

Palaniappan A , Dave U , Gosine B

Rev Panam Salud Publica , 44:e53, 15 Apr 2020

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 32454806 | PMCID: PMC7241577

The "Glocalization" of Medical School Accreditation: Case Studies From Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan.

Ho MJ , Abbas J , Ahn D , Lai CW , Nara N , Shaw K

Acad Med , 92(12):1715-1722, 01 Dec 2017

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 29068814

Focused and Corrective Feedback Versus Structured and Supported Debriefing in a Simulation-Based Cardiac Arrest Team Training: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Study.

Kim JH , Kim YM , Park SH , Ju EA , Choi SM , Hong TY

Simul Healthc , 12(3):157-164, 01 Jun 2017

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 28166188

A first report of East Asian students' perception of progress testing: a focus group study.

Matsuyama Y , Muijtjens AM , Kikukawa M , Stalmeijer R , Murakami R , Ishikawa S , Okazaki H

BMC Med Educ , 16(1):245, 22 Sep 2016

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 27658501 | PMCID: PMC5034519

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Online resources for assessment and evaluation.

Benjamin S , Robbins LI , Kung S

Acad Psychiatry , 30(6):498-504, 01 Nov 2006

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 17139021

Addressing deficiencies in american healthcare education: a call for informed instructional design.

Asher A , Kondziolka D , Selden NR

Neurosurgery , 65(2):223-9; discussion 229-30, 01 Aug 2009

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 19625899

Towards effective evaluation and reform in medical education: a cognitive and learning sciences perspective.

Patel VL , Yoskowitz NA , Arocha JF

Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract , 14(5):791-812, 24 Jan 2008

Cited by: 31 articles | PMID: 18214707

Potential of information technology in dental education.

Mattheos N , Stefanovic N , Apse P , Attstrom R , Buchanan J , Brown P , Camilleri A , Care R , Fabrikant E , Gundersen S , Honkala S , Johnson L , Jonas I , Kavadella A , Moreira J , Peroz I , Perryer DG , Seemann R , Tansy M , [...] Walmsley AD

Eur J Dent Educ , 12 Suppl 1:85-92, 01 Feb 2008

Cited by: 45 articles | PMID: 18289271

Medical education in an era of health-care reform.

Perspect Biol Med , 54(1):61-67, 01 Jan 2011

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 21399384

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

Study Abroad Aide

The Best Study Abroad Site

Study Medicine in Korea: 7 Things to Know

Having a professional occupation is a very long and tedious process especially if you are just taking your first step – studying. Hours, months, years are spent in before someone achieve their dreams and be professional in their fields. They will need to have the dedication and a strong commitment because many have given up in the middle of this process.

One of the most sought out professions around the world is the profession of being a doctor and studying medicine. Doctors are one of the most important jobs and one of the most honorable because they save lives and people from their illnesses. However, since they are dealing with something that needs to be delicately taken care of, doctors need to diligently study to avoid mistakes that will endanger the life of their patients.

With this said, as much as possible, if you want to become a doctor, you need to get your education from a place or country that offers an international education and has advanced and modern facilities to help you become a good doctor. And you could get these qualities if you would go to Korea and pursue your medical degree there. South Korea, specifically, offers a wide variety of degrees and among those degrees, the fields of medicine are what they specialize at. So, if you are an aspiring student who wants to study medicine in Korea, here are some tips and pointers that you will be needing.

1. In what language do you study medicine in Korea?

Studying medicine in a different country is difficult but so is teaching, too. This is the reason why Korean universities teach medicine in their native language so that they can completely and clearly explain their materials that will be taught to future doctors.

The foreign students who wish to study in Korea need to take a Korean language proficiency test as soon as they got admitted to the university like what they require at Seoul National University . Moreover, if you are still struggling in the Korean language, there are supplementary language courses that are also offered in the university so take a look at them.

2. What are the requirements to study medicine in Korea?

There are several things to consider if you want to pursue a medical degree in Korea, it takes at least 6 years for a student to get their medical degrees and then pursue their specializations. If you are just starting to get an undergraduate degree , you need to process all the basic requirements as an international or foreign student.

These include your report card in high school, previous educational background, passport, application forms for the university you will be enrolling in, a Korean language proficiency test, and a student visa. Sometimes, especially if you went to a Non-English school, you are required to take an IELTS or a TOEFL to test your English Proficiency.

3. Can you study medicine in Korea as an international student?

Yes, you can study medicine in Korea as an international student especially if you have the necessary forms and requirements, also, as long as you can speak Korean. There are many medical universities in Korea that are accepting international students to their programs. In fact, on their official websites, there are international offices for students whose prospective studies lie in the field of medicine. Some of these are Seoul National University , Sungkyunkwan University , and many more.

4. What are the components of the medical curriculum in Korea?

The medical curriculum in Korea is almost the same as the usual curriculum of medical degrees globally yet it slightly differs from other universities in terms of the time of their study. To get a degree in medicine, a student must study medicine in Korea and complete a 6- or 8-year curriculum which does not include a field specialization.

The first two to four years of the curriculum will focus on the undergraduate studies of the students which are also known as the pre-medical period. This period will include examinations every semester. The next two years of the curriculum will solely be for pre-clinical basic science which includes hospital visits and other activities related to that matter.

Lastly, the last two years of their curriculum will be for clinical rotations which are, in a sense, the same as an internship but are completely different. Students will have shifts in doing tasks that are assigned to them by their professional colleagues.

5. How many medical schools are in Korea?

Currently, 36 universities in Korea offer degrees in the field of medicine. Some universities are solely offering this course and specialize in them while other universities have different schools or faculty for other branches of study. However, more medical schools are being established and more state universities are still trying to offer medical degrees so it is expected that the number of medical schools will rise in the future.

There are many prestigious medical schools in Korea. If you are interested, visit the 10 Best Medical Schools in Korea .

6. How difficult is it to study medicine in Korea?

It is very difficult to study medicine in Korea especially if you are an international student. Entrance exams for medical degrees are very competitive in Korea because only a few are admitted and the exams are relatively hard compared to other programs.

Moreover, even though the dropout rate of students in medical schools in Korea is low having at most 5% dropouts every year, students who get the degree within the 6-year curriculum are also few. So, it can be said that the difficulty to study medicine in Korea is relatively high but it is not impossible.

7. What do you need to become a doctor after you study medicine in Korea?

After getting your Bachelor’s degree after studying medicine in Korea for 6 years, you will be required to get an additional 4-year medical post-graduate degree and a foreign accredited medical school certificate. These are the conditions that you are needed to meet before you are allowed to take the Korean Medical Licensing Examination (KMLE). Passing this licensure exam will grant you the title of being a doctor. This will be not a difficult pass because of the years that you have been studying are enough.

I hope that this article was helpful. If you are interested, visit the Korea Scholarships Page!

2 thoughts on “ Study Medicine in Korea: 7 Things to Know ”

Hello, do I have to apply for premed first without any test and once I finish the course, pass the entrance exam? Or do i have to pass the entrance exam first that includes both premed and medicine?

Hello, you apply to “premed” first before any test and there’s no entrance exam. Medicine in Korea is a 6-year bachelor’s degree so it includes both premed and medicine courses.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Courses by Degree

- Undergraduate

- Master’s

Courses by Country

- United Kingdom

Courses by Subject

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Hospitality and Tourism Management

Top Streams

- Data Science Courses in USA

- Business Analytics Courses in USA

- Engineering Courses in USA

- Tax Courses in USA

- Healthcare Courses in USA

- Language Courses in USA

- Insurance Courses in USA

- Digital Marketing Courses in USA

Top Specialization

- Masters in Data Analytics in USA

- Masters in Mechanical Engineering in USA

- Masters in Supply Chain Management in USA

- Masters in Computer Science in USA

- MBA in Finance in USA

- Masters in Architecture in USA

Top Universities

- Cornell University

- Yale University

- Princeton University

- University of California Los Angeles

- University of Harvard

- Stanford University

- Arizona State University

- Northeastern University

ACCEL PROGRAMS

- Master of Business Administration

- MS in Data Analytics

- MS in Computer Science

- Project Management Courses in Australia

- Accounting Courses in Australia

- Medical Courses in Australia

- Psychology Courses in Australia

- Interior Designing Courses in Australia

- Pharmacy Courses in Australia

- Social Work Courses in Australia

- MBA in Australia

- Masters in Education in Australia

- Masters in Pharmacy in Australia

- Masters in Information Technology in Australia

- BBA in Australia

- Masters in Teaching in Australia

- Masters in Psychology in Australia

- University of Melbourne

- Deakin University

- Carnegie Mellon University

- Monash University

- University of Sydney

- University of Queensland

- RMIT University

- Macquarie University

- Bachelor of Business Administration

- Bachelor of Computer Applications

- Data Science Courses in Canada

- Business Management Courses in Canada

- Supply Chain Management Courses in Canada

- Project Management Courses in Canada

- Business Analytics Courses in Canada

- Hotel Management Courses in Canada

- MBA in Canada

- MS in Canada

- Masters in Computer Science in Canada

- Masters in Management in Canada

- Masters in Psychology in Canada

- Masters in Education in Canada

- MBA in Finance in Canada

- Masters in Business Analytics in Canada

- University of Toronto

- University of British Columbia

- McGill University

- University of Alberta

- York University

- University of Calgary

- Algoma University

- University Canada West

- BBA in Canada, Trinity Western University

- BBA in Canada, Yorkville University

- Project Management Courses in UK

- Data Science Courses in UK

- Public Health Courses in UK

- Digital Marketing Courses in UK

- Hotel Management Courses in UK

- Nursing Courses in UK

- Medicine Courses in UK

- Interior Designing Courses in UK

- Masters in Computer Science in UK

- Masters in Psychology in UK

- MBA in Finance in UK

- MBA in Healthcare Management in UK

- Masters in Education in UK

- Masters in Marketing in UK

- MBA in HR in UK

- University of Oxford

- University of Cambridge

- Coventry University

- University of East London

- University of Hertfordshire

- University of Birmingham

- Imperial College London

- University of Glasgow

- MBA with Work Placement

- MSc Data Science with Work Placement

Top Resources

- Universities in Germany

- Study in Germany

- Masters in Germany

- Courses in Germany

- Bachelors in Germany

- Germany Job Seeker Visa

- Cost of Living in Germany

- Best Universities in Germany

Top Courses

- Masters in Data Science in Germany

- MS in Computer Science in Germany

- Marine Engineering in Germany

- MS Courses in Germany

- Masters in Psychology in Germany

- Hotel Management Courses in Germany

- Masters in Economics in Germany

- Paramedical Courses in Germany

- Karlsruhe Institute of Technology

- University of Bonn

- University of Freiburg

- University of Hamburg

- University of Stuttgart

- Saarland University

- Mannheim University

- Master of Business Administration (90 ECTS)

- MS Data Science 60 ECTS

- Master in Computer Science (120 ECTS)

- MBA in Ireland

- Phd in Ireland

- Masters in Computer Science Ireland

- Cyber Security in Ireland

- Masters in Data Analytics Ireland

- Ms in Data Science in Ireland

- Pharmacy courses in ireland

- Business Analytics Course in Ireland

- Universities in Ireland

- Study in Ireland

- Masters in Ireland

- Courses in Ireland

- Bachelors in Ireland

- Cost of Living in Ireland

- Ireland Student Visa

- Part Time Jobs in Ireland

- Trinity College Dublin

- University College Dublin

- Dublin City University

- University of Limerick

- Dublin Business School

- Maynooth University

- University College Cork

- National College of Ireland

Colleges & Courses

- Masters in France

- Phd in France

- Study Medicine in France

- Best Universities in Frankfurt

- Best Architecture Colleges in France

- ESIGELEC France

- Study in France for Indian Students

- Intakes in France

- SOP for France Visa

- Study in France from India

- Reasons to Study in France

- How to Settle in France

More About France

- Cost of Living in France

- France Study Visa

- Cost of Living in Frankfurt

- France Scholarship for Indian Students

- Part Time Jobs in France

- Stay Back in France After Masters

About Finland

- Universities in Finland

- Study in Finland

- Courses in Finland

- Bachelor Courses in Finland

- Masters Courses in Finland

- Cost of Living in Finland

- MS in Finland

- Average Fees in Finland Universities

- PhD in Finland

- MBA Leading Business Transformation

- MBA Business Technologies

- Bachelor Degree in Medicine & Surgery

- MBBS Courses in Georgia

- MBBS Courses in Russia

- Alte University

- Caucasus University

- Georgian National University SEU

- David Tvildiani Medical University

- Caspian International School Of Medicine

- Asfendiyarov Kazakh National Medical University

- Kyrgyz State Medical Academy

- Cremeia Federal University

- Bashkir State Medical University

- Kursk State Medical University

- Andijan State Medical Institute

- IELTS Syllabus

- IELTS Prepration

- IELTS Eligibility

- IELTS Test Format

- IELTS Band Descriptors

- IELTS Speaking test

- IELTS Writing Task 1

- IELTS score validity

- IELTS Cue Card

IELTS Reading Answers Sample

- Animal Camouflage

- Types Of Societies

- Australia Convict Colonies

- A Spark A Flint

- Emigration To The Us

- The History Of Salt

- Zoo Conservation Programmes

- The Robots Are Coming

- The Development Of Plastic

IELTS Speaking Cue Card Sample

- Describe A Puzzle You Have Played

- Describe A Long Walk You Ever Had

- Describe Your Favourite Movie

- Describe A Difficult Thing You did

- Describe A Businessman You Admire

- Memorable Day in My Life

- Describe Your Dream House

- Describe A Bag You Want to Own

- Describe a Famous Athlete You Know

- Aquatic Animal

IELTS Essay Sample Sample

- Best Education System

- IELTS Opinion Essay

- Agree or Disagree Essay

- Problem Solution Essays

- Essay on Space Exploration

- Essay On Historical Places

- Essay Writing Samples

- Tourism Essay

- Global Warming Essay

- GRE Exam Fees

- GRE Exam Syllabus

- GRE Exam Eligibility

- Sections in GRE Exam

- GRE Exam Benefits

- GRE Exam Results

- GRE Cutoff for US Universities

- GRE Preparation

- Send GRE scores to Universities

GRE Exam Study Material

- GRE Verbal Preparation

- GRE Study Material

- GRE AWA Essays

- GRE Sample Issue Essays

- Stanford University GRE Cutoff

- Harvard University GRE Cutoff

- GRE Quantitative Reasoning

- GRE Verbal Reasoning

- GRE Reading Comprehension

- Prepare for GRE in 2 months

Other Resources

- Documents Required For Gre Exam

- GRE Exam Duration

- GRE at Home

- GRE vs GMAT

- Improve GRE Verbal Scores

Free GRE Ebooks

- GRE Preparation Guide (Free PDF)

- GRE Syllabus (Free PDF)

- GMAT Eligibility

- GMAT Syllabus

- GMAT Exam Dates

- GMAT Registration

- GMAT Exam Fees

- GMAT Sections

- GMAT Purpose

GMAT Exam Study Material

- How to prepare for GMAT?

- GMAT Score Validity

- GMAT Preparation Books

- GMAT Preparation

- GMAT Exam Duration

- GMAT Score for Harvard

- GMAT Reading Comprehension

- GMAT Retake Strategy

Free GMAT Ebooks

- GMAT Guide PDF

- Download GMAT Syllabus PDF

- TOEFL Exam Registration

- TOEFL Exam Eligibility

- TOEFL Exam Pattern

- TOEFL Exam Preparation

- TOEFL Exam Tips

- TOEFL Exam Dates

- Documents for TOEFL Exam

- TOEFL Exam Fee

TOEFL Exam Study Material

- TOEFL Preparation Books

- TOEFL Speaking Section

- TOEFL Score and Results

- TOEFL Writing Section

- TOEFL Reading Section

- TOEFL Listening Section

- TOEFL Vocabulary

- Types of Essays in TOEFL

Free TOEFL Ebooks

- TOEFL Exam Guide (Free PDF)

- PTE Exam Dates

- PTE Exam Syllabus

- PTE Exam Eligibility Criteria

- PTE Test Centers in India

- PTE Exam Pattern

- PTE Exam Fees

- PTE Exam Duration

- PTE Exam Registration

PTE Exam Study Material

- PTE Exam Preparation

- PTE Speaking Test

- PTE Reading Test

- PTE Listening Test

- PTE Writing Test

- PTE Essay Writing

- PTE exam for Australia

Free PTE Ebooks

- PTE Syllabus (Free PDF)

- Duolingo Exam

- Duolingo Test Eligibility

- Duolingo Exam Pattern

- Duolingo Exam Fees

- Duolingo Test Validity

- Duolingo Syllabus

- Duolingo Preparation

Duolingo Exam Study Material

- Duolingo Exam Dates

- Duolingo Test Score

- Duolingo Test Results

- Duolingo Test Booking

Free Duolingo Ebooks

- Duolingo Guide (Free PDF)

- Duolingo Test Pattern (Free PDF)

NEET & MCAT Exam

- NEET Study Material

- NEET Preparation

- MCAT Eligibility

- MCAT Preparation

SAT & ACT Exam

- ACT Eligibility

- ACT Exam Dates

- SAT Syllabus

- SAT Exam Pattern

- SAT Exam Eligibility

USMLE & OET Exam

- USMLE Syllabus

- USMLE Preparation

- USMLE Step 1

- OET Syllabus

- OET Eligibility

- OET Prepration

PLAB & LSAT Exam

- PLAB Exam Syllabus

- PLAB Exam Fees

- LSAT Eligibility

- LSAT Registration

- TOEIC Result

- Study Guide

Application Process

- LOR for Masters

- SOP Samples for MS

- LOR for Phd

- SOP for Internship

- SOP for Phd

- Check Visa Status

- Motivation Letter Format

- Motivation Letter for Internship

- F1 Visa Documents Checklist

Career Prospects

- Popular Courses after Bcom in Abroad

- Part Time Jobs in Australia

- Part Time Jobs in USA

- Salary after MS in Germany

- Salary after MBA in Canada

- Average Salary in Singapore

- Higher Studies after MBA in Abroad

- Study in Canada after 12th

Trending Topics

- Best Education System in World

- Best Flying Schools in World

- Top Free Education Countries

- Best Countries to Migrate from India

- 1 Year PG Diploma Courses in Canada

- Canada Vs India

- Germany Post Study Work Visa

- Post Study Visa in USA

- Data Science Vs Data Analytics

- Public Vs Private Universities in Germany

- Universities Vs Colleges

- Difference Between GPA and CGPA

- Undergraduate Vs Graduate

- MBA in UK Vs MBA in USA

- Degree Vs Diploma in Canada

- IELTS vs TOEFL

- Duolingo English Test vs. IELTS

- Why Study in Canada

- Cost of Living in Canada

- Education System in Canada

- SOP for Canada

- Summer Intake in Canada

- Spring Intake in Canada

- Winter Intake in Canada

- Accommodation in Canada for Students

- Average Salary in Canada

- Fully Funded Scholarships in Canada

- Why Study in USA

- Cost of Studying in USA

- Spring Intake in USA

- Winter Intake in USA

- Summer Intake in USA

- STEM Courses in USA

- Scholarships for MS in USA

- Acceptable Study Gap in USA

- Interesting Facts about USA

- Free USA course

- Why Study in UK

- Cost of Living in UK

- Cost of Studying in UK

- Education System in UK

- Summer Intake in UK

- Spring Intake in UK

- Student Visa for UK

- Accommodation in UK for Students

- Scholarships in UK

- Why Study in Germany

- Cost of Studying in Germany

- Education System in Germany

- SOP for Germany

- Summer Intake in Germany

- Winter Intake in Germany

- Study Visa for Germany

- Accommodation in Germany for Students

- Free Education in Germany

Country Guides

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in USA

- Study in Australia

- SOP Samples for Canada Student Visa

- US F1 Visa Guide for Aspirants

Exams Guides

- Duolingo Test Pattern

Recommended Reads

- Fully Funded Masters Guide

- SOP Samples For Australia

- Scholarships for Canada

- Data Science Guide

- SOP for MS in Computer Science

- Study Abroad Exams

- Alumni Connect

- Booster Program

GPA CALCULATOR Convert percentage marks to GPA effortlessly with our calculator!

Expense calculator plan your study abroad expenses with our comprehensive calculator, ielts band calculator estimate your ielts band score with our accurate calculator, education loan calculator discover your eligible loan amount limit with our education calculator, university partner explore growth and opportunities with our university partnership, accommodation discover your perfect study abroad accommodation here, experience-center discover our offline centers for a personalized experience, our offices visit us for expert study abroad counseling..

- 18002102030

- Study Abroad

MBBS in South Korea for Indian Students

- Study in Singapore After 12th

- Study in Japan

- Cost of Living in Japan

- Education System in Singapore

- Study in South Korea

- Medical Colleges in Malaysia

Updated on 08 November, 2023

Pragya Sharma

Sr. content editor.

South Korea, known for its technological advancements and rich cultural heritage, is also emerging as a top destination for pursuing MBBS. This can be seen by the fact that revenue in the healthcare market has a projected annual growth rate of 1.45%, resulting in a projected market volume of US$1,09 million by 2027. Let us dive into the important details of MBBS in South Korea.

Table of Contents

Why study mbbs in south korea, top universities in south korea for mbbs, eligibility criteria for mbbs in south korea, mbbs in south korea: intakes offered, mbbs in south korea: scholarships.

- 1.General Practitioner:

- 2.Specialist Doctor:

- 3.Medical Researcher:

- 4.Medical Professor:

- 5.Medical Writer:

- 1.Internal Medicine:

- 2.Pediatrics:

- 4.Obstetrics and Gynecology:

- 5.Psychiatry:

- 6.Anesthesiology:

- 7.Radiology:

- 8.Orthopedics:

- 9.Ophthalmology:

- 10.Dermatology:

MCI-Approved Medical Colleges in South Korea

Korean medical degree:, mandatory subjects:.

MBBS in South Korea typically has a duration of six years. The curriculum is devised with a strong foundation in medical knowledge and skills, covering subjects like anatomy, physiology , pathology, pharmacology , and clinical practice. The average MBBS in South Korea costs range from KRW 10,547,600 to KRW 19,776,750 per year, depending on the university and the specialization chosen.

Top Reasons to Study MBBS Abroad

To understand the perks of studying MBBS in South Korea, here is a list of its advantages.

- South Korean medical institutions are equipped with state-of-the-art facilities, modern laboratories, and simulation centers, enabling students to gain practical exposure and develop clinical expertise.

- The country is a hub for scientific research and advancements in the medical field. Students pursuing MBBS in South Korea have ample opportunities to contend in research projects and contribute to medical breakthroughs.

- Studying in South Korea allows students to experience a multicultural environment, interact with students from diverse backgrounds, and broaden their horizons.

- It is known for its excellent healthcare system, which consistently ranks among the best in the world. Studying in such an environment ensures exposure to high standards of medical practice.

- It has a growing demand for qualified medical professionals, providing generous job opportunities for MBBS graduates. The country's healthcare sector offers competitive salaries and a supportive work environment.

South Korea has several prestigious universities with top-notch MBBS programs. Here are the top universities in South Korea for MBBS, along with their necessary details for international students:

*per university websites

** Application deadline indicates last year’s dates

Aspiring medical students must fulfill certain eligibility criteria to study MBBS in South Korea . Here are the key points to consider:

- Applicants must have completed high school or an equivalent qualification with a strong background in science subjects.

- Proficiency in the English language is essential to study MBBS in South Korea. Students are required to provide scores from recognized English language proficiency tests such as TOEFL or IELTS .

- Students should obtain a valid student visa to study in South Korea.

- Before 2018, Indian students aspiring to study MBBS in South Korea were required to obtain an eligibility certificate from the MCI under the Indian Medical Council (IMC) Act , 1956. However, this requirement was replaced by the necessity of qualifying for the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) for domestic and international medical aspirants. The NEET scorecard is now the eligibility credential for appearing in the screening test for South Korean medical graduates.

It is important to note the specific eligibility criteria may vary slightly between universities, so it is recommended to check the requirements of the chosen institution before applying.

Universities in South Korea offer two types of intakes for MBBS programs: Spring Intake and Fall Intake. Each intake's opening and closing dates may vary from university to university.

- Fall Semester: March to April

- Spring Semester: July to September

Students should check the specific intake dates of their preferred universities to ensure they submit their applications on time.

There are several scholarships available for international students pursuing an MBBS degree in South Korea. These scholarships financially support deserving students to pursue MBBS in South Korea.

MBBS in South Korea: Jobs

Graduates have various career pathways to explore after completing their MBBS in South Korea. Here is a list of the top career choices.

1.General Practitioner:

A general practitioner works in clinics or private practices, diagnosing and treating common illnesses. A general practitioner's salary in South Korea is expected to be around KRW 110,000,000 per year.

2.Specialist Doctor :

Specializing in a specific medical field after MBBS, such as cardiology, neurology, or dermatology, allows you to earn a higher salary. The average salary for a cardiology specialist doctor in South Korea ranges from KRW 85,600,000 to KRW 272,000,000.

3.Medical Researcher:

If you have a keen interest in medical research, you can pursue a career as a medical researcher in a renowned research institution. The medical researcher's average salary in South Korea is KRW 108,000,000 per year.

4.Medical Professor:

MBBS graduates can pursue a career in medical education by becoming professors or lecturers in medical universities. The salary for medical educators in South Korea ranges from KRW 39,700,000 to KRW 137,000,000.

5.Medical Writer:

As a medical writer, you can work in pharmaceutical companies or healthcare publications, creating informative content related to medical advancements. The average salary for medical writers in South Korea is around KRW 47,149,696 per year.

MBBS in South Korea: Top Specializations

On completing the MBBS in South Korea, one has ample choices for undertaking a specialization. The following are the top specializations that offer exceptional learning opportunities and career prospects to significantly contribute to the field of medicine.

1.Internal Medicine :

This specialization focuses on diagnosing, treating, and preventing diseases affecting internal organs.

2.Pediatrics :

Pediatricians specialize in the medical care of infants, children, and adolescents.

3.Surgery :

Surgeons are trained in performing various surgical procedures to treat diseases and injuries.

4.Obstetrics and Gynecology :

This specialization deals with the medical care of women during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum.

5.Psychiatry :

Psychiatrists diagnose and treat mental disorders, providing counseling and therapy to patients.

6.Anesthesiology :

Anesthesiologists are responsible for administering anesthesia and monitoring patients during surgery .

7.Radiology :

Radiologists use medical imaging techniques to diagnose and treat diseases.

8.Orthopedics :

Orthopedic surgeons specialize in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders and injuries.

9.Ophthalmology :

Ophthalmologists diagnose and treat eye diseases, performing surgeries if required.

10.Dermatology :

Dermatologists focus on the diagnosis and treatment of skin diseases and conditions.

The National Medical Commission (NMC, a statutory authority constituted by the Central Government of India, has taken over the responsibility of regulating medical education and practice in India, substituting the Medical Council of India (MCI). The official list of MCI-approved medical colleges in South Korea has been out of practice since the NMC has taken over.

FMGE Guidelines for Indian Students Pursuing MBBS in South Korea

The FMGE guidelines establish a standardized framework for evaluating the eligibility of Indian medical graduates and meet the requirements to practice medicine in India.

Though pursuing MBBS in South Korea is a good option for Indian students, however, to practice in India, every student who has completed a medical degree abroad must pass the FMGE conducted by the NMC to obtain a provisional or permanent registration to practice medicine in India.

To be eligible for permanent registration in India, Indian students pursuing MBBS in South Korea must meet the following criteria:

- Korean medical graduates must have completed a course leading to a foreign medical degree with a minimum duration of 54 months.

- They must have undergone an internship for a minimum of 12 months in the same foreign medical institution.

- The Korean medical degree must have been obtained with English as the medium of instruction.

- The graduates must be registered with their home country’s respective professional regulatory body or competent authority, granting them a license to practice medicine.

- The students must have studied subjects like Community Medicine, General Medicine, Psychiatry , Pediatrics, General Surgery, Anesthesia, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Orthopedics, Otorhinolaryngology, Ophthalmology, Dermatology, Emergency or Casualty services, lab services, and their sub-specialties.

With its affordable tuition fees, multicultural environment, and high healthcare standards, South Korea is definitely an excellent choice for MBBS in South Korea for Indian students. However, Indian students must also be well-informed about the guidelines and requirements set by the NMC to ensure a seamless transition from studying in South Korea to practicing medicine in India.

Disclaimer: Fees and costs mentioned in the article are indicative and subject to change at any time .

To know more about MBBS Abroad:

- MBBS in New Zealand

- MBBS in Poland

- MBBS in Italy

- MBBS in Bulgaria

- MBBS in Japan

- MBBS in Belgium

- MBBS in Spain

- Mbbs-in-sweden

- MBBS Abroad Without NEET

Can we do MBBS in South Korea without NEET?

No, to pursue MBBS in South Korea, students are required to have a qualifying score in the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) conducted in India.

After studying for an MBBS in South Korea, can I work in India as a doctor?

Yes, Indian students who complete their MBBS in South Korea can work in India as doctors. However, they must pass the Foreign Medical Graduate Examination (FMGE) conducted by the National Medical Commission (NMC).

Do universities in South Korea provide accommodation?

Many universities in South Korea provide accommodation facilities for international students. It is advisable to check with the respective universities for detailed information regarding accommodation options and availability.

What is the salary of an MBBS doctor in South Korea?

The salary of an MBBS doctor in South Korea varies on factors such as specialization, experience, and the type of healthcare facility. The average salary ranges from KRW 40,300,000 to KRW 185,000,000 per year.

Pragya Sharma is a content developer and marketer with 6.5+ years of experience in the education industry. She started her career as a social media copywriter for NIELIT, Ministry of Electronics & IT, and has now scaled up as a 360-degree content professional well-versed with the intricacies of digital marketing and different forms of content used to drive and hook the target audience. She is also a co-author of 2 stories in an anthology based on the theme- women empowerment.

Exams to Study Abroad

Top study abroad destinations, important resources, get free consultation for study abroad, similar articles.

Participants

A total of 87 students participated in this program, 43 medical and 44 nursing students. The data of participating students who did not respond to or responded insincerely to the survey to verify the effectiveness of this study were excluded. Thirty-seven fifth-year medical students and 38 fourth-year nursing students participated in the IPE program, and a total of 75 response variables were used for the analyses. Medical students in the 5th grade have competencies for essential treatments and clinical skills through major clinical clerkship, and have basic competencies for coping with emergency situations. In addition, the 4th grade nursing students have completed all clinical practice and have the basic knowledge and skills required in the medical situation at the hospital. In other words, it can be seen that the participants of this study are at the stage before entering the job and have the ability to evaluate their own capabilities. Missing responses or insincere responses were excluded. Students completed the questionnaire before and after IPE participation.

In our study, the attitude toward interprofessional learning was measured using the Attitude Towards Teamwork in Training Undergoing Designed Educational Simulation (ATTITUDES) scale which was developed by Sigalet et al. [ 15 ]. This scale consists of 30 items organized into five sub-factors: IPE relevance (7 items, e.g., I want more opportunities to learn with other professionals.), simulation relevance (5 items, e.g., Simulation is a good tool for practicing team decision-making skills.), communication (8 items, e.g., Communication within the team is as important as technical skills.), situation awareness (4 items, e.g., Patient care is improved when all team members have a shared understanding about assessment and treatment.), and roles and responsibilities (6 items, e.g., Monitoring what each team member is doing is important for optimizing patient safety.). Each question was measured on a five-point scale from “strongly disagree” (1 point) to “strongly agree” (5 points). It can be seen that the higher the total score, the more positive students’ attitude toward interprofessional learning through simulation-based IPE. In this study, the pre and post-IPE questions show internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.962 and 0.985, respectively).

To measure the perception of teamwork and collaboration between physicians and nurses, Jefferson Scale of Attitudes toward Physician-Nurse Collaboration (JSAPNC) developed by Hojat et al. [ 16 ] was used in this study. This scale consists of 15 items and 4 sub-factors: shared educational and collaborative relationships (7 items, e.g., Interprofessional relationships between physicians and nurses should be included in both professions’ educational programs.), caring as opposed to curing (3 items, e.g., Nurses are qualified to assess and respond to psychological aspects of patients’ needs.), nurse’s autonomy (3 items, e.g., Nurses should be accountable to patients for the nursing care they provide.), and physician’s authority (2 items, e.g., Doctors should be the dominant authority in all healthcare matters.). Each item was measured on a four-point scale from “strongly disagree” (1 point) to “strongly agree” (4 points). The higher the total score, the more positively students perceive teamwork and collaboration between physicians and nurses. The Cronbach α for inter-consistency before and after IPE was 0.911 and 0.935, respectively.

The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) Competency self-assessment tool developed by Lockeman [ 17 ] was used to measure students’ competency in interprofessional practice. This scale consists of two sub-factors: interprofessional interaction (7 items, e.g., I can use strategies that will improve the effectiveness of interprofessional teamwork and team-based care.) and interprofessional value (9 items, e.g., I can embrace the diversity that characterizes patients and the healthcare team.). Each item was measured on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” (1 point) to “strongly agree” (5 points). It can be seen that the higher the total score, the more students perceived as more competent in interprofessional practice. The Cronbach α for competency before and after IPE was 0.957 and 0.980, respectively.

Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted to identify the demographic distribution of participants in this study, and t-tests were conducted to explore response differences between the professional groups of medical and nursing students. Additionally, paired t-tests were conducted using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) to identify changes in medical and nursing students’ scores before and after IPE participation.

Demographics

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 2 . There were 1.7 times more male students than female students among the medical-school respondents, while there were 4 times more female students than male students among the nursing-school respondents. Medical students had no prior experience in simulation training, but nursing students had undergone previous simulation training. None of the participating students had any educational experience with other professions.

ATTITUDES, JSAPNC, and IPEC Competency scores according to profession are presented in Table 3 . The differences between ATTITUDES, JSAPNC, and IPEC Competency were compared and analyzed for both student groups before and after IPE. Nursing students scored higher than medical students in ATTITUDES and IPEC Competency before and after IPE. The two groups did not differ significantly in JSAPNC scores before or after IPE.

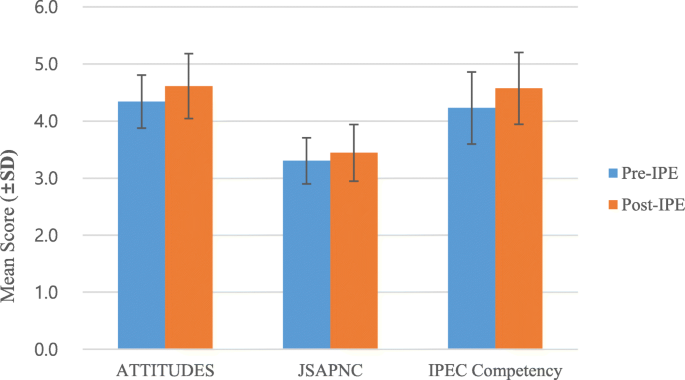

The results of comparative analyses of the differences between the ATTITUDES, JSAPNC, and IPEC Competency scores before and after IPE experience are presented in Fig. 1 .

Comparison of ATTITUDES, JSAPNC, and IPEC Competency scores before and after simulation-based interprofessional education

All students participating in interprofessional education showed significant improvement in ATTITUDES, JSAPNC, and IPEC competency scores. Before the interprofessional education, the average scores of each scale were ATTITUDES (M = 4.34, SD = 0.47), JSAPNC (M = 3.30, SD = 0.40), and IPEC Competency (M = 4.23, SD = 0.63). After the program experience, the score of each scale was found to increase significantly as follows: ATTITUDES (M = 4.61, SD = 0.57, t = 4.63 *** ), JSAPNC (M = 3.44, SD = 0.50, t = 2.87 ** ), and IPEC Competency (M = 4.57, SD = 0.63, t = 5.25 *** ).

Table 4 shows the ATTITUDES, JSAPNC, and IPEC Competency scale scores for medical and nursing students before and after participating in IPE programs. The overall score for nursing students was higher than that for medical students, but the score for physician’s authority, one of the sub-factors of the JSAPNC scale was higher among medical students (pre: M = 2.80 vs. M = 2.57, post: M = 2.92 vs. M = 2.72).

The total scores from ATTITUDES (t = 2.50, p < 0.05 vs. t = 5.32, p < 0.001) and IPEC Competency (t = 3.44, p < 0.01 vs. t = 4.34, p < 0.00) increased significantly after IPE in both medical and nursing students. The total score for JSAPNC showed no significant change among medical students, but a significant increase among nursing students (t = 3.02, p < 0.01). Regarding changes in scores before and after IPE by JSAPNC sub-factors, in “shared educational and collaborative relationships,” which both measure the perception of collaboration between physicians and nurses, the scores from both medical students and nursing students increased (t = 2.36, p < 0.05). vs. t = 3.64, p < 0.01). For medical students, however, there was no change in scores for caring as opposed to curing, nurse’s autonomy, or physician’s authority, which measures the identity of each profession group. Also, there was no significant change in the score for physician’s authority among nursing students.

We found that nursing students were more positively aware of interprofessional learning and competency in interprofessional practice than medical students. Prior studies that compared the impact of IPE experience on the perception of interprofessional learning between the different professional groups have yielded mixed results. A study that compared attitudes to interprofessional learning before and after IPE [ 15 ] for different professional groups showed that medical students had more positive attitudes toward IPE than nursing students, which is a contrary finding to this study. This means that certain profession, nurses or physicians, do not always have a more positive attitude toward interprofessional learning than others. What direct or indirect experiences they had in patient care settings in previous clinical practice may be more important factors for attitude toward interprofessional collaboration and interprofessional learning [ 18 ].

Prior to this study, neither the nursing- nor medical-student participants had IPE experience, but medical students had 1 year of clinical experience practice, while nursing students, who were at the end of their fourth year, had almost 2 years of clinical experience practice and the nursing students had previously undertaken simulation in clerkship. Clinical experience practice provides positive and negative role modeling observations and collaboration among doctors, nurses, and other relevant allied health practitioners [ 19 ], and extensive exposure to situations that require collaboration with other professional groups may affect students’ perceptions of interprofessional learning [ 20 ]. It can be understood in the same context that the more experienced clinical practice, the higher the self-competency in interprofesssional practice. Therefore, one interpretation of our results is that nursing students with more clinical experience practice responded more positively toward interprofessional learning and self-competency in interprofessional situations than medical students. After simulation-based IPE, the attitude toward interprofessional learning for all participating professions improved. These results are consistent with a prior study [ 21 ] in which a simulation-based IPE program had a positive effect on the attitudes of medical and nursing students toward IPE. Additionally, after simulation-based IPE, the perception of all students who participated in teamwork and collaborations between physicians and nurses had improved.

However, sub-analyses of only medical students and only nursing students revealed no change in medical students’ perception about nurse autonomy nor nursing students’ perception about physician authority according to factors measuring perceptions of professional identity. In other words, we observed no change in students’ perception of the professional identities of the different profession groups, which is in contrast with a previous study [ 22 , 23 ] that found changes in stereotypes of other professions after IPE. We infer that this is due to the cultural contexts of the rigid Korean medical organizations. Two days of short-term IPE is unlikely to change students’ perceptions of the roles of other professions compared to what they learned through their clinical training in the hospital. The point of focus between physicians and nurses is different in the clinical settings, the physicians are in charge of a directive role that makes the overall decision-making, and the nurse takes on a subservient role that focuses on patient care [ 24 ]. Our findings suggest that existing stereotypes about specific professions are challenges to be overcome in interprofessional learning. Beyond short-term special programs, it is necessary to include interprofessional collaborative training in clinical practice so that students can fully understand the role of other professions through the process of experiencing, observing, interacting, and reflecting positive modeling [ 25 , 26 ].

After simulation-based IPE, self-reported competency improved for both medical and nursing students. Through IPE, students improved their ability to communicate and solve problems collaboratively among their health care team, and to understand team members and perform patient-centered care more effectively. A prior study [ 27 , 28 ] found that interprofessional simulation improved self-competency in communication, collaboration, and situation management among team members in clinical settings. Competency development is a key component of clinical training [ 29 ]. Continuous provision of IPE improves competency, which helps postgraduates perform proficiently in their field of patient care. Patient care in clinical contexts always requires effective teamwork and communication skills among the health care team. However, because the current university education system is centered on majors, the necessary qualities for collaboration are insufficiently cultivated. IPE could be a good alternative approach to fill this learning gap.

This study is meaningful in that it is an empirical study that identified the educational effects of simulation-based IPEs in Korea, where IPE education has not yet been enacted. This study evaluated the educational effects of IPE, but this study has limitations in that it is a study on a single and short IPE. In order to analyze the effects of IPE in more detail, it is necessary to conduct IPE periodically and then perform analysis based on accumulated data. In addition, in analyzing the effects of the IPE program, there are limitations in that there may be various factors that can affect the study results in addition to the factors considered in this study. It is necessary to conduct a follow-up study that considers more various related variables such as student achievement. This study also has limitations in that it used an outdated scale that was developed to investigate the perception of teamwork and collaboration between physicians and nurses. When using it in future research, it is necessary to consider using it after going through an appropriate revision for the item according to the current situation. It also has an important limitation, in that it did not evaluate how long the effects of IPE will last. A reliable estimate of the effect duration is important for setting the cycle of education. It would then be necessary to conduct a study among postgraduates who participated in IPE as students to periodically evaluate the persistence of the educational effects of IPE. Additionally, in the long-term, when students embark on real clinical work after graduation, it is important to conduct research to evaluate whether healthcare professionals who had IPE experience during their training show better clinical performance through effective teamwork and communication.

This study was conducted to assess attitudes toward interprofessional learning, perception of teamwork and collaboration between doctors and nurses, and self-reported competency of students in interprofessional practice, and to compare the differences before and after simulation-based IPE. Through IPE, students’ attitude toward interprofessional leaning and self-competency in interprofessional practice were improved. The perception of teamwork and collaboration between physicians and nurses showed no significant change among medical students but increased significantly among nursing students. Additionally, there was no significant change in the perception of the role of other professions among either medical or nursing students.

In this study, we found evidence for a positive educational effect of IPE in terms of participants recognizing the necessity of IPE and improving students’ confidence in their inter-professional collaboration abilities. However, the fact that the existing perception of the role of other professions did not change after IPE shows the limitations of a one-time short-term program. Efforts should be made to include programs within the clinical-practice curriculum that provide social interactions with other profession groups in clinical situations so that students can be continuously exposed to these experiences.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Interprofessional Education

Attitude Towards Teamwork in Training Undergoing Designed Educational Simulation

Jefferson Scale of Attitudes toward Physician-Nurse Collaboration

Interprofessional Education Collaborative

Davenport DL, Henderson WG, Mosca CL, Khuri SF, Mentzer RM. Risk-adjusted morbidity in teaching hospitals correlates with reported levels of communication and collaboration on surgical teams but not with scale measures of teamwork climate, safety climate, or working conditions. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:778–84.

Article Google Scholar

Galletta M, Portoqhese I, Carta MG, D’Aloja E, Campaqna M. The effect of nurse-physician collaboration on job satisfaction, team commitment, and turnover intention in nurses. Res Nurs Health. 2016;39:375–85.

Vestergaard E, Nørgaard B. Interprofessional collaboration: an exploration of possible prerequisites for successful implementation. J Interprof Care. 2018;32:185–95.

Reeves S, Fletcher S, Barr H, Birch I, Boet S, Davies N, et al. A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME guide no. 39. Med Teach. 2016;38:656–68.

Brashers V, Erickson JM, Blackhall L, Owen JA, Thomas SM, Conaway MR. Measuring the impact of clinically relevant interprofessional education on undergraduate medical and nursing student competencies: a longitudinal mixed methods approach. J Interprof Care. 2016;30:448–57.

Burford B, Greig P, Kelleher M, Merriman C, Platt A, Richards E, et al. Effects of a single interprofessional simulation session on medical and nursing students’ attitudes toward interprofessional learning and professional identity: a questionnaire study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-1971-6 .

Zhang C, Thompson S, Miller C. A review of simulation-based interprofessional education. Clin Simul Nurs. 2011;7:e117–26.

Meyer BA, Seefeldt TM, Nqorsuraches S, Hendrickx LD, Lubeck PM, Farver DK, et al. Interprofessional education in pharmacology using high-fidelity simulation. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2017;9:1055–62.

Cook DA, Hatala R, Brydges R, Zendejas B, Szostek JH, Wang AT, et al. Technology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;306:978–88.

Google Scholar

Brim NM, Venkatan SK, Gordon JA, Alexander EK. Long-term educational impact of a simulator curriculum on medical student education in an internal medicine clerkship. Simul Healthc. 2010;5:75–81.

McGregor CA, Paton C, Thomson C, Chandratilake M, Scott H. Preparing medical students for clinical decision making: a pilot study exploring how students make decisions and the perceived impact of a clinical decision making teaching intervention. Med Teach. 2012;34:e508–17.

Arthur C, Levett-Jones T, Kable A. Quality indicators for the design and implementation of simulation experiences: a Delphi study. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33:1357–61.

Datta R, Upadhyay K, Jaideep C. Simulation and its role in medical education. Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68:167–72.

Labrague LJ, McEnroe-Petitte DM, Fronda DC, Obeidat AA. Interprofessional simulation in undergraduate nursing program: an integrative review. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;67:46–55.

Sigalet E, Donnon T, Grant V. Undergraduate studnets’ perceptions of and attitudes toward a simulation-based interprofessional curriculum: the KidSIM ATTITUDES questionnaire. Simul Healthc. 2012;7:353–8.

Hojat M, Fields SK, Veloski JJ, Griffiths M, Cohen MJ, Plumb JD. Psychometric properties of an attitude scale measuring physician-nurse collaboration. Eval Health Prof. 1999;22:208–20.

Lockeman KS, Dow AW, DiazGranados D, McNeily DP, Nickol D, Koehn ML, et al. Refinement of the IPEC competency self-assessment survey: results from a multi-institutional study. J Interprof Care. 2016;30:726–31.

Hood K, Cant R, Baulch J, Gilbee A, Leech M, Anderson A, et al. Prior experience of interprofessional learning enhances undergraduate nursing and healthcare students’ professional identity and attitudes to teamwork. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14:117–22.

Palmer R, Stilp T. Learning by doing: the MD-PA interprofessional education rural rotation. Rural Remote Health. 2017;17:4167 Available from: https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/4167 .

Keshtkaran Z, Sharif F, Rambod M. Students’ readiness for and perception of inter-professional learning: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34:991–8.

Scherer YK, Myers J, O’Connor TD, Haskins M. Interprofessional simulation to foster collaboration between nursing and medical students. Clin Simul Nurs. 2013;9:e497–505.

Ateah CA, Snow W, Wener P, MacDonald L, Metge C, Davis P, et al. Stereotyping as a barrier to collaboration: does interprofessional education make a difference? Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31:208–13.

Liaw SY, Siau C, Zhou WT, Lau TC. Interprofessional simulation-based education program: a promising approach for changing stereotypes and improving attitudes toward nurse-physician collaboration. Appl Nurs Res. 2014;27:258–60.

Casanova J, Day K, Dorpat D, Hendricks B, Theis L, Wiesman D. Nurse-physician work relations and role expectations. J Nurs Adm. 2007;37:68–70.

Khalili H, Orchard C, Laschinger HK, Farah R. An interprofessional socialization framework for developing an interprofessional identity among health professions students. J Interprof Care. 2013;27:448–53.

Gilligan C, Outram S, Levett-Jones T. Recommendations from recent graduates in medicine, nursing and pharmacy on improving interprofessional education in university programs; a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:634–40.

Watters C, Reedy G, Ross A, Morgan NJ, Handslip R, Jaye P. Does interprofessional simulation increase self-efficacy: a comparative study. BMJ Open. 2015;13:e005472. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005472 .

Garbee DD, Paige JT, Bonanno LS, Rusnak VV, Barrier KM, Kozmenko LS, et al. Effectiveness of teamwork and communication education using an interprofessioanl high-fidelity human patient simulation critical care code. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2013;3. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v3n3p1 .

Maqnani D, Di Lorenzo R, Bari A, Pozzi S, Del Giovane C, Ferri P. The undergraduate nursing student evaluation of clinical learning environment: an Italian survey. Prof Inferm. 2014;67:55–61.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted on an IPE program with the support of the Simulation Center of the college of Nursing at Daegu Science University. All the authors appreciate the willingness to utilize all the space in the simulation center.

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Jihye Yu and woosuck Lee are contributed equally and co-first authors.

Authors and Affiliations

Office of Medical Education, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, South Korea

College of Nursing, Taegu Science University, Daegu, South Korea

woosuck Lee, Yu-Jin Lee, Soo-Jin Hyun, Yun KANG & So Myeong Kim

Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, South Korea

Miran Kim & Dongwook Kwak

Department of Emergency Medicine, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, South Korea

Sangcheon Choi & Sungeun Lee

Department of Gastroenterology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, South Korea

Soonsun Kim

Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, South Korea

Yunjung Jung

Department of Pediatrics, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, South Korea

Hyunjoo Jung & Janghoon Lee