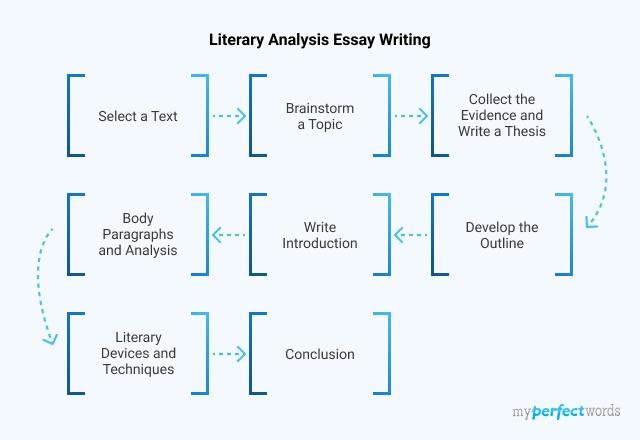

Literary Analysis Essay Writing

Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Outline - A Step By Step Guide

People also read

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay - A Step-by-Step Guide

Interesting Literary Analysis Essay Topics & Ideas

Have you ever felt stuck, looking at a blank page, wondering what a literary analysis essay is? You are not sure how to analyze a complicated book or story?

Writing a literary analysis essay can be tough, even for people who really love books. The hard part is not only understanding the deeper meaning of the story but also organizing your thoughts and arguments in a clear way.

But don't worry!

In this easy-to-follow guide, we will talk about a key tool: The Literary Analysis Essay Outline.

We'll provide you with the knowledge and tricks you need to structure your analysis the right way. In the end, you'll have the essential skills to understand and structure your literature analysis better. So, let’s dive in!

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

- 1. How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay Outline?

- 2. Literary Analysis Essay Format

- 3. Literary Analysis Essay Outline Example

- 4. Literary Analysis Essay Topics

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay Outline?

An outline is a structure that you decide to give to your writing to make the audience understand your viewpoint clearly. When a writer gathers information on a topic, it needs to be organized to make sense.

When writing a literary analysis essay, its outline is as important as any part of it. For the text’s clarity and readability, an outline is drafted in the essay’s planning phase.

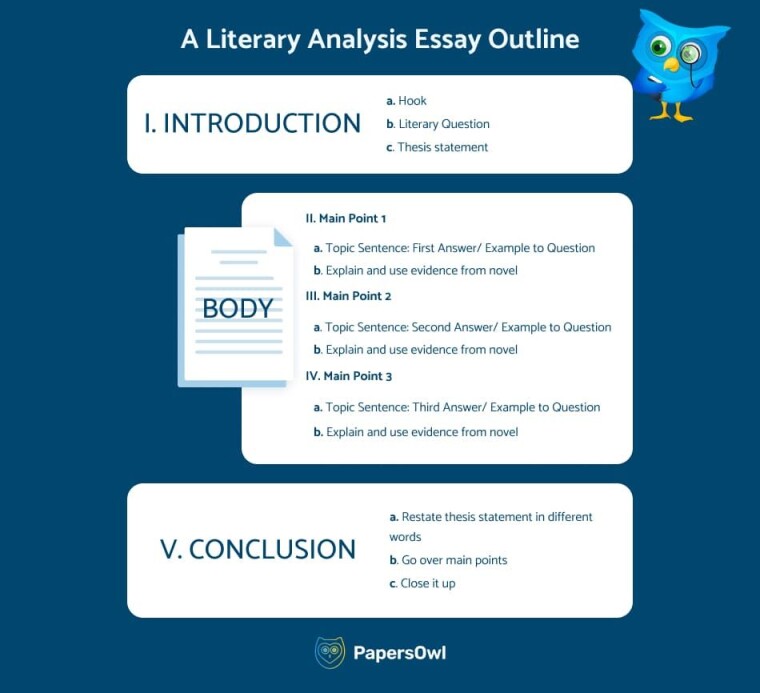

According to the basic essay outline, the following are the elements included in drafting an outline for the essay:

- Introduction

- Thesis statement

- Body paragraphs

A detailed description of the literary analysis outline is provided in the following section.

Literary Analysis Essay Introduction

An introduction section is the first part of the essay. The introductory paragraph or paragraphs provide an insight into the topic and prepares the readers about the literary work.

A literary analysis essay introduction is based on three major elements:

Hook Statement: A hook statement is the opening sentence of the introduction. This statement is used to grab people’s attention. A catchy hook will make the introductory paragraph interesting for the readers, encouraging them to read the entire essay.

For example, in a literary analysis essay, “ Island Of Fear,” the writer used the following hook statement:

“As humans, we all fear something, and we deal with those fears in ways that match our personalities.”

Background Information: Providing background information about the chosen literature work in the introduction is essential. Present information related to the author, title, and theme discussed in the original text.

Moreover, include other elements to discuss, such as characters, setting, and the plot. For example:

“ In Lord of the Flies, William Golding shows the fears of Jack, Ralph, and Piggy and chooses specific ways for each to deal with his fears.”

Thesis Statement: A thesis statement is the writer’s main claim over the chosen piece of literature.

A thesis statement allows your reader to expect the purpose of your writing. The main objective of writing a thesis statement is to provide your subject and opinion on the essay.

For example, the thesis statement in the “Island of Fear” is:

“...Therefore, each of the three boys reacts to fear in his own unique way.”

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Literary Analysis Essay Body Paragraphs

In body paragraphs, you dig deep into the text, show your insights, and build your argument.

In this section, we'll break down how to structure and write these paragraphs effectively:

Topic sentence: A topic sentence is an opening sentence of the paragraph. The points that will support the main thesis statement are individually presented in each section.

For example:

“The first boy, Jack, believes that a beast truly does exist…”

Evidence: To support the claim made in the topic sentence, evidence is provided. The evidence is taken from the selected piece of work to make the reasoning strong and logical.

“...He is afraid and admits it; however, he deals with his fear of aggressive violence. He chooses to hunt for the beast, arms himself with a spear, and practice killing it: “We’re strong—we hunt! If there’s a beast, we’ll hunt it down! We’ll close in and beat and beat and beat—!”(91).”

Analysis: A literary essay is a kind of essay that requires a writer to provide his analysis as well.

The purpose of providing the writer’s analysis is to tell the readers about the meaning of the evidence.

“...He also uses the fear of the beast to control and manipulate the other children. Because they fear the beast, they are more likely to listen to Jack and follow his orders...”

Transition words: Transition or connecting words are used to link ideas and points together to maintain a logical flow. Transition words that are often used in a literary analysis essay are:

- Furthermore

- Later in the story

- In contrast, etc.

“...Furthermore, Jack fears Ralph’s power over the group and Piggy’s rational thought. This is because he knows that both directly conflict with his thirst for absolute power...”

Concluding sentence: The last sentence of the body that gives a final statement on the topic sentence is the concluding sentence. It sums up the entire discussion held in that specific paragraph.

Here is a literary analysis paragraph example for you:

Literary Essay Example Pdf

Literary Analysis Essay Conclusion

The last section of the essay is the conclusion part where the writer ties all loose ends of the essay together. To write appropriate and correct concluding paragraphs, add the following information:

- State how your topic is related to the theme of the chosen work

- State how successfully the author delivered the message

- According to your perspective, provide a statement on the topic

- If required, present predictions

- Connect your conclusion to your introduction by restating the thesis statement.

- In the end, provide an opinion about the significance of the work.

For example,

“ In conclusion, William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies exposes the reader to three characters with different personalities and fears: Jack, Ralph, and Piggy. Each of the boys tries to conquer his fear in a different way. Fear is a natural emotion encountered by everyone, but each person deals with it in a way that best fits his/her individual personality.”

Literary Analysis Essay Outline (PDF)

Literary Analysis Essay Format

A literary analysis essay delves into the examination and interpretation of a literary work, exploring themes, characters, and literary devices.

Below is a guide outlining the format for a structured and effective literary analysis essay.

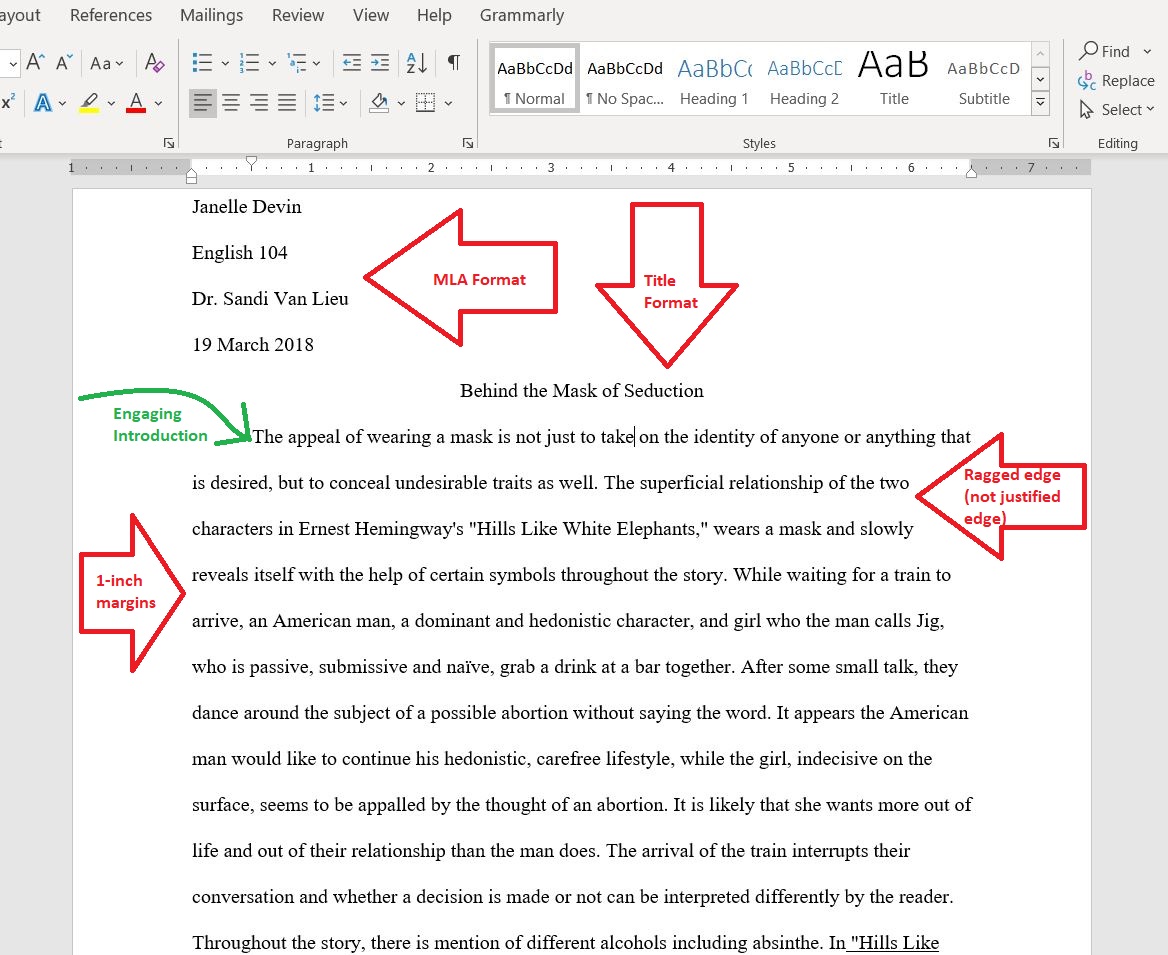

Formatting Guidelines

- Use a legible font (e.g., Times New Roman or Arial) and set the font size to 12 points.

- Double-space your essay, including the title, headings, and quotations.

- Set one-inch margins on all sides of the page.

- Indent paragraphs by 1/2 inch or use the tab key.

- Page numbers, if required, should be in the header or footer and follow the specified formatting style.

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Example

To fully understand a concept in a writing world, literary analysis outline examples are important. This is to learn how a perfectly structured writing piece is drafted and how ideas are shaped to convey a message.

The following are the best literary analysis essay examples to help you draft a perfect essay.

Literary Analysis Essay Rubric (PDF)

High School Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Outline College (PDF)

Literary Analysis Essay Example Romeo & Juliet (PDF)

AP Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Middle School

Literary Analysis Essay Topics

Are you seeking inspiration for your next literary analysis essay? Here is a list of literary analysis essay topics for you:

- The Theme of Alienation in "The Catcher in the Rye"

- The Motif of Darkness in Shakespeare's Tragedies

- The Psychological Complexity of Hamlet's Character

- Analyzing the Narrator's Unreliable Perspective in "The Tell-Tale Heart"

- The Role of Nature in William Wordsworth's Romantic Poetry

- The Representation of Social Class in "To Kill a Mockingbird"

- The Use of Irony in Mark Twain's "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn"

- The Impact of Holden's Red Hunting Hat in the Novel

- The Power of Setting in Gabriel García Márquez's "One Hundred Years of Solitude"

- The Symbolism of the Conch Shell in William Golding's "Lord of the Flies"

Need more topics? Read our literary analysis essay topics blog!

All in all, writing a literary analysis essay can be tricky if it is your first attempt. Apart from analyzing the work, other elements like a topic and an accurate interpretation must draft this type of essay.

If you are in doubt to draft a perfect essay, get professional assistance from our essay service .

We are a professional essay writing company that provides guidance and helps students to achieve their academic goals. Our qualified writers assist students by providing assistance at an affordable price.

So, why wait? Let us help you in achieving your academic goals!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Cathy has been been working as an author on our platform for over five years now. She has a Masters degree in mass communication and is well-versed in the art of writing. Cathy is a professional who takes her work seriously and is widely appreciated by clients for her excellent writing skills.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

You’ve been assigned a literary analysis paper—what does that even mean? Is it like a book report that you used to write in high school? Well, not really.

A literary analysis essay asks you to make an original argument about a poem, play, or work of fiction and support that argument with research and evidence from your careful reading of the text.

It can take many forms, such as a close reading of a text, critiquing the text through a particular literary theory, comparing one text to another, or criticizing another critic’s interpretation of the text. While there are many ways to structure a literary essay, writing this kind of essay follows generally follows a similar process for everyone

Crafting a good literary analysis essay begins with good close reading of the text, in which you have kept notes and observations as you read. This will help you with the first step, which is selecting a topic to write about—what jumped out as you read, what are you genuinely interested in? The next step is to focus your topic, developing it into an argument—why is this subject or observation important? Why should your reader care about it as much as you do? The third step is to gather evidence to support your argument, for literary analysis, support comes in the form of evidence from the text and from your research on what other literary critics have said about your topic. Only after you have performed these steps, are you ready to begin actually writing your essay.

Writing a Literary Analysis Essay

How to create a topic and conduct research:.

Writing an Analysis of a Poem, Story, or Play

If you are taking a literature course, it is important that you know how to write an analysis—sometimes called an interpretation or a literary analysis or a critical reading or a critical analysis—of a story, a poem, and a play. Your instructor will probably assign such an analysis as part of the course assessment. On your mid-term or final exam, you might have to write an analysis of one or more of the poems and/or stories on your reading list. Or the dreaded “sight poem or story” might appear on an exam, a work that is not on the reading list, that you have not read before, but one your instructor includes on the exam to examine your ability to apply the active reading skills you have learned in class to produce, independently, an effective literary analysis.You might be asked to write instead or, or in addition to an analysis of a literary work, a more sophisticated essay in which you compare and contrast the protagonists of two stories, or the use of form and metaphor in two poems, or the tragic heroes in two plays.

You might learn some literary theory in your course and be asked to apply theory—feminist, Marxist, reader-response, psychoanalytic, new historicist, for example—to one or more of the works on your reading list. But the seminal assignment in a literature course is the analysis of the single poem, story, novel, or play, and, even if you do not have to complete this assignment specifically, it will form the basis of most of the other writing assignments you will be required to undertake in your literature class. There are several ways of structuring a literary analysis, and your instructor might issue specific instructions on how he or she wants this assignment done. The method presented here might not be identical to the one your instructor wants you to follow, but it will be easy enough to modify, if your instructor expects something a bit different, and it is a good default method, if your instructor does not issue more specific guidelines.You want to begin your analysis with a paragraph that provides the context of the work you are analyzing and a brief account of what you believe to be the poem or story or play’s main theme. At a minimum, your account of the work’s context will include the name of the author, the title of the work, its genre, and the date and place of publication. If there is an important biographical or historical context to the work, you should include that, as well.Try to express the work’s theme in one or two sentences. Theme, you will recall, is that insight into human experience the author offers to readers, usually revealed as the content, the drama, the plot of the poem, story, or play unfolds and the characters interact. Assessing theme can be a complex task. Authors usually show the theme; they don’t tell it. They rarely say, at the end of the story, words to this effect: “and the moral of my story is…” They tell their story, develop their characters, provide some kind of conflict—and from all of this theme emerges. Because identifying theme can be challenging and subjective, it is often a good idea to work through the rest of the analysis, then return to the beginning and assess theme in light of your analysis of the work’s other literary elements.Here is a good example of an introductory paragraph from Ben’s analysis of William Butler Yeats’ poem, “Among School Children.”

“Among School Children” was published in Yeats’ 1928 collection of poems The Tower. It was inspired by a visit Yeats made in 1926 to school in Waterford, an official visit in his capacity as a senator of the Irish Free State. In the course of the tour, Yeats reflects upon his own youth and the experiences that shaped the “sixty-year old, smiling public man” (line 8) he has become. Through his reflection, the theme of the poem emerges: a life has meaning when connections among apparently disparate experiences are forged into a unified whole.

In the body of your literature analysis, you want to guide your readers through a tour of the poem, story, or play, pausing along the way to comment on, analyze, interpret, and explain key incidents, descriptions, dialogue, symbols, the writer’s use of figurative language—any of the elements of literature that are relevant to a sound analysis of this particular work. Your main goal is to explain how the elements of literature work to elucidate, augment, and develop the theme. The elements of literature are common across genres: a story, a narrative poem, and a play all have a plot and characters. But certain genres privilege certain literary elements. In a poem, for example, form, imagery and metaphor might be especially important; in a story, setting and point-of-view might be more important than they are in a poem; in a play, dialogue, stage directions, lighting serve functions rarely relevant in the analysis of a story or poem.

The length of the body of an analysis of a literary work will usually depend upon the length of work being analyzed—the longer the work, the longer the analysis—though your instructor will likely establish a word limit for this assignment. Make certain that you do not simply paraphrase the plot of the story or play or the content of the poem. This is a common weakness in student literary analyses, especially when the analysis is of a poem or a play.

Here is a good example of two body paragraphs from Amelia’s analysis of “Araby” by James Joyce.

Within the story’s first few paragraphs occur several religious references which will accumulate as the story progresses. The narrator is a student at the Christian Brothers’ School; the former tenant of his house was a priest; he left behind books called The Abbot and The Devout Communicant. Near the end of the story’s second paragraph the narrator describes a “central apple tree” in the garden, under which is “the late tenant’s rusty bicycle pump.” We may begin to suspect the tree symbolizes the apple tree in the Garden of Eden and the bicycle pump, the snake which corrupted Eve, a stretch, perhaps, until Joyce’s fall-of-innocence theme becomes more apparent.

The narrator must continue to help his aunt with her errands, but, even when he is so occupied, his mind is on Mangan’s sister, as he tries to sort out his feelings for her. Here Joyce provides vivid insight into the mind of an adolescent boy at once elated and bewildered by his first crush. He wants to tell her of his “confused adoration,” but he does not know if he will ever have the chance. Joyce’s description of the pleasant tension consuming the narrator is conveyed in a striking simile, which continues to develop the narrator’s character, while echoing the religious imagery, so important to the story’s theme: “But my body was like a harp, and her words and gestures were like fingers, running along the wires.”

The concluding paragraph of your analysis should realize two goals. First, it should present your own opinion on the quality of the poem or story or play about which you have been writing. And, second, it should comment on the current relevance of the work. You should certainly comment on the enduring social relevance of the work you are explicating. You may comment, though you should never be obliged to do so, on the personal relevance of the work. Here is the concluding paragraph from Dao-Ming’s analysis of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

First performed in 1895, The Importance of Being Earnest has been made into a film, as recently as 2002 and is regularly revived by professional and amateur theatre companies. It endures not only because of the comic brilliance of its characters and their dialogue, but also because its satire still resonates with contemporary audiences. I am still amazed that I see in my own Asian mother a shadow of Lady Bracknell, with her obsession with finding for her daughter a husband who will maintain, if not, ideally, increase the family’s social status. We might like to think we are more liberated and socially sophisticated than our Victorian ancestors, but the starlets and eligible bachelors who star in current reality television programs illustrate the extent to which superficial concerns still influence decisions about love and even marriage. Even now, we can turn to Oscar Wilde to help us understand and laugh at those who are earnest in name only.

Dao-Ming’s conclusion is brief, but she does manage to praise the play, reaffirm its main theme, and explain its enduring appeal. And note how her last sentence cleverly establishes that sense of closure that is also a feature of an effective analysis.

You may, of course, modify the template that is presented here. Your instructor might favour a somewhat different approach to literary analysis. Its essence, though, will be your understanding and interpretation of the theme of the poem, story, or play and the skill with which the author shapes the elements of literature—plot, character, form, diction, setting, point of view—to support the theme.

Academic Writing Tips : How to Write a Literary Analysis Paper. Authored by: eHow. Located at: https://youtu.be/8adKfLwIrVk. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

BC Open Textbooks: English Literature Victorians and Moderns: https://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/back-matter/appendix-5-writing-an-analysis-of-a-poem-story-and-play/

Literary Analysis

The challenges of writing about english literature.

Writing begins with the act of reading . While this statement is true for most college papers, strong English papers tend to be the product of highly attentive reading (and rereading). When your instructors ask you to do a “close reading,” they are asking you to read not only for content, but also for structures and patterns. When you perform a close reading, then, you observe how form and content interact. In some cases, form reinforces content: for example, in John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14, where the speaker invites God’s “force” “to break, blow, burn and make [him] new.” Here, the stressed monosyllables of the verbs “break,” “blow” and “burn” evoke aurally the force that the speaker invites from God. In other cases, form raises questions about content: for example, a repeated denial of guilt will likely raise questions about the speaker’s professed innocence. When you close read, take an inductive approach. Start by observing particular details in the text, such as a repeated image or word, an unexpected development, or even a contradiction. Often, a detail–such as a repeated image–can help you to identify a question about the text that warrants further examination. So annotate details that strike you as you read. Some of those details will eventually help you to work towards a thesis. And don’t worry if a detail seems trivial. If you can make a case about how an apparently trivial detail reveals something significant about the text, then your paper will have a thought-provoking thesis to argue.

Common Types of English Papers Many assignments will ask you to analyze a single text. Others, however, will ask you to read two or more texts in relation to each other, or to consider a text in light of claims made by other scholars and critics. For most assignments, close reading will be central to your paper. While some assignment guidelines will suggest topics and spell out expectations in detail, others will offer little more than a page limit. Approaching the writing process in the absence of assigned topics can be daunting, but remember that you have resources: in section, you will probably have encountered some examples of close reading; in lecture, you will have encountered some of the course’s central questions and claims. The paper is a chance for you to extend a claim offered in lecture, or to analyze a passage neglected in lecture. In either case, your analysis should do more than recapitulate claims aired in lecture and section. Because different instructors have different goals for an assignment, you should always ask your professor or TF if you have questions. These general guidelines should apply in most cases:

- A close reading of a single text: Depending on the length of the text, you will need to be more or less selective about what you choose to consider. In the case of a sonnet, you will probably have enough room to analyze the text more thoroughly than you would in the case of a novel, for example, though even here you will probably not analyze every single detail. By contrast, in the case of a novel, you might analyze a repeated scene, image, or object (for example, scenes of train travel, images of decay, or objects such as or typewriters). Alternately, you might analyze a perplexing scene (such as a novel’s ending, albeit probably in relation to an earlier moment in the novel). But even when analyzing shorter works, you will need to be selective. Although you might notice numerous interesting details as you read, not all of those details will help you to organize a focused argument about the text. For example, if you are focusing on depictions of sensory experience in Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale,” you probably do not need to analyze the image of a homeless Ruth in stanza 7, unless this image helps you to develop your case about sensory experience in the poem.

- A theoretically-informed close reading. In some courses, you will be asked to analyze a poem, a play, or a novel by using a critical theory (psychoanalytic, postcolonial, gender, etc). For example, you might use Kristeva’s theory of abjection to analyze mother-daughter relations in Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved. Critical theories provide focus for your analysis; if “abjection” is the guiding concept for your paper, you should focus on the scenes in the novel that are most relevant to the concept.

- A historically-informed close reading. In courses with a historicist orientation, you might use less self-consciously literary documents, such as newspapers or devotional manuals, to develop your analysis of a literary work. For example, to analyze how Robinson Crusoe makes sense of his island experiences, you might use Puritan tracts that narrate events in terms of how God organizes them. The tracts could help you to show not only how Robinson Crusoe draws on Puritan narrative conventions, but also—more significantly—how the novel revises those conventions.

- A comparison of two texts When analyzing two texts, you might look for unexpected contrasts between apparently similar texts, or unexpected similarities between apparently dissimilar texts, or for how one text revises or transforms the other. Keep in mind that not all of the similarities, differences, and transformations you identify will be relevant to an argument about the relationship between the two texts. As you work towards a thesis, you will need to decide which of those similarities, differences, or transformations to focus on. Moreover, unless instructed otherwise, you do not need to allot equal space to each text (unless this 50/50 allocation serves your thesis well, of course). Often you will find that one text helps to develop your analysis of another text. For example, you might analyze the transformation of Ariel’s song from The Tempest in T. S. Eliot’s poem, The Waste Land. Insofar as this analysis is interested in the afterlife of Ariel’s song in a later poem, you would likely allot more space to analyzing allusions to Ariel’s song in The Waste Land (after initially establishing the song’s significance in Shakespeare’s play, of course).

- A response paper A response paper is a great opportunity to practice your close reading skills without having to develop an entire argument. In most cases, a solid approach is to select a rich passage that rewards analysis (for example, one that depicts an important scene or a recurring image) and close read it. While response papers are a flexible genre, they are not invitations for impressionistic accounts of whether you liked the work or a particular character. Instead, you might use your close reading to raise a question about the text—to open up further investigation, rather than to supply a solution.

- A research paper. In most cases, you will receive guidance from the professor on the scope of the research paper. It is likely that you will be expected to consult sources other than the assigned readings. Hollis is your best bet for book titles, and the MLA bibliography (available through e-resources) for articles. When reading articles, make sure that they have been peer reviewed; you might also ask your TF to recommend reputable journals in the field.

Harvard College Writing Program: https://writingproject.fas.harvard.edu/files/hwp/files/bg_writing_english.pdf

In the same way that we talk with our friends about the latest episode of Game of Thrones or newest Marvel movie, scholars communicate their ideas and interpretations of literature through written literary analysis essays. Literary analysis essays make us better readers of literature.

Only through careful reading and well-argued analysis can we reach new understandings and interpretations of texts that are sometimes hundreds of years old. Literary analysis brings new meaning and can shed new light on texts. Building from careful reading and selecting a topic that you are genuinely interested in, your argument supports how you read and understand a text. Using examples from the text you are discussing in the form of textual evidence further supports your reading. Well-researched literary analysis also includes information about what other scholars have written about a specific text or topic.

Literary analysis helps us to refine our ideas, question what we think we know, and often generates new knowledge about literature. Literary analysis essays allow you to discuss your own interpretation of a given text through careful examination of the choices the original author made in the text.

ENG134 – Literary Genres Copyright © by The American Women's College and Jessica Egan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Writing A Literary Analysis Essay

- Library Resources

- Books & EBooks

- What is an Literary Analysis?

- Literary Devices & Terms

- Creating a Thesis Statement This link opens in a new window

- Using quotes or evidence in your essay

- APA Format This link opens in a new window

- MLA Format This link opens in a new window

- OER Resources

- Copyright, Plagiarism, and Fair Use

Video Links

Elements of a short story, Part 1

YouTube video

Elements of a short story, Part 2

online tools

Collaborative Mind Mapping – collaborative brainstorming site

Sample Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Paper Format and Structure

Analyzing Literature and writing a Literary Analysis

Literary Analysis are written in the third person point of view in present tense. Do not use the words I or you in the essay. Your instructor may have you choose from a list of literary works read in class or you can choose your own. Follow the required formatting and instructions of your instructor.

Writing & Analyzing process

First step: Choose a literary work or text. Read & Re-Read the text or short story. Determine the key point or purpose of the literature

Step two: Analyze key elements of the literary work. Determine how they fit in with the author's purpose.

Step three: Put all information together. Determine how all elements fit together towards the main theme of the literary work.

Step four: Brainstorm a list of potential topics. Create a thesis statement based on your analysis of the literary work.

Step five: search through the text or short story to find textual evidence to support your thesis. Gather information from different but relevant sources both from the text itself and other secondary sources to help to prove your point. All evidence found will be quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to help explain your argument to the reader.

Step six: Create and outline and begin the rough draft of your essay.

Step seven: revise and proofread. Write the final draft of essay

Step eight: include a reference or works cited page at the end of the essay and include in-text citations.

When analyzing a literary work pay close attention to the following:

Characters: A character is a person, animal, being, creature, or thing in a story.

- Protagonist : The main character of the story

- Antagonist : The villain of the story

- Love interest : the protagonist’s object of desire.

- Confidant : This type of character is the best friend or sidekick of the protagonist

- Foil – A foil is a character that has opposite character traits from another character and are meant to help highlight or bring out another’s positive or negative side.

- Flat – A flat character has one or two main traits, usually only all positive or negative.

- Dynamic character : A dynamic character is one who changes over the course of the story.

- Round character : These characters have many different traits, good and bad, making them more interesting.

- Static character : A static character does not noticeably change over the course of a story.

- Symbolic character : A symbolic character represents a concept or theme larger than themselves.

- Stock character : A stock character is an ordinary character with a fixed set of personality traits.

Setting: The setting is the period of time and geographic location in which a story takes place.

Plot: a literary term used to describe the events that make up a story

Theme: a universal idea, lesson, or message explored throughout a work of literature.

Dialogue: any communication between two characters

Imagery: a literary device that refers to the use of figurative language to evoke a sensory experience or create a picture with words for a reader.

Figures of Speech: A word or phrase that is used in a non-literal way to create an effect.

Tone: A literary device that reflects the writer's attitude toward the subject matter or audience of a literary work.

rhyme or rhythm: Rhyme is a literary device, featured particularly in poetry, in which identical or similar concluding syllables in different words are repeated. Rhythm can be described as the beat and pace of a poem

Point of view: the narrative voice through which a story is told.

- Limited – the narrator sees only what’s in front of him/her, a spectator of events as they unfold and unable to read any other character’s mind.

- Omniscient – narrator sees all. He or she sees what each character is doing and can see into each character’s mind.

- Limited Omniscient – narrator can only see into one character’s mind. He/she might see other events happening, but only knows the reasons of one character’s actions in the story.

- First person: You see events based on the character telling the story

- Second person: The narrator is speaking to you as the audience

Symbolism: a literary device in which a writer uses one thing—usually a physical object or phenomenon—to represent something else.

Irony: a literary device in which contradictory statements or situations reveal a reality that is different from what appears to be true.

Ask some of the following questions when analyzing literary work:

- Which literary devices were used by the author?

- How are the characters developed in the content?

- How does the setting fit in with the mood of the literary work?

- Does a change in the setting affect the mood, characters, or conflict?

- What point of view is the literary work written in and how does it effect the plot, characters, setting, and over all theme of the work?

- What is the over all tone of the literary work? How does the tone impact the author’s message?

- How are figures of speech such as similes, metaphors, and hyperboles used throughout the text?

- When was the text written? how does the text fit in with the time period?

Creating an Outline

A literary analysis essay outline is written in standard format: introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. An outline will provide a definite structure for your essay.

I. Introduction: Title

A. a hook statement or sentence to draw in readers

B. Introduce your topic for the literary analysis.

- Include some background information that is relevant to the piece of literature you are aiming to analyze.

C. Thesis statement: what is your argument or claim for the literary work.

II. Body paragraph

A. first point for your analysis or evidence from thesis

B. textual evidence with explanation of how it proves your point

III. second evidence from thesis

A. textual evidence with explanation of how it proves your point

IV. third evidence from thesis

V. Conclusion

A. wrap up the essay

B. restate the argument and why its important

C. Don't add any new ideas or arguments

VI: Bibliography: Reference or works cited page

End each body paragraph in the essay with a transitional sentence.

Links & Resources

Literary Analysis Guide

Discusses how to analyze a passage of text to strengthen your discussion of the literature.

The Writing Center @ UNC-Chapel Hill

Excellent handouts and videos around key writing concepts. Entire section on Writing for Specific Fields, including Drama, Literature (Fiction), and more. Licensed under CC BY NC ND (Creative Commons - Attribution - NonCommercial - No Derivatives).

Creating Literary Analysis (Cordell and Pennington, 2012) – LibreTexts

Resources for Literary Analysis Writing

Some free resources on this site but some are subscription only

Students Teaching English Paper Strategies

The Internet Public Library: Literary Criticism

- << Previous: Literary Devices & Terms

- Next: Creating a Thesis Statement >>

- Last Updated: Jan 24, 2024 1:22 PM

- URL: https://wiregrass.libguides.com/c.php?g=1191536

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

Table of contents

- 1 Understanding the Assignment

- 2 Preparatory Work

- 3.1 First Reading

- 3.2 Second Reading

- 3.3 Take Notes

- 4.1 Defining Your Audience

- 4.2 The Title of Your Essay

- 4.3 Literary Analysis Essay Outline

- 4.4 Introduction

- 4.5 Body Paragraphs

- 4.6 Conclusion

- 5 Revising the Essay

- 6 In Conclusion

Writing a literary analysis essay is one of the most difficult tasks for a student. When you have to analyze a certain literary work, there is a whole set of rules that you have to follow. The literary analysis structure is rigid, and students often are demoralized by things like that.

Our article hopes to be a comprehensive guide that can explain how to write literary analysis essay. Here is what you will learn:

- The importance of understanding your assignment and choosing the right topic;

- Organizing your critical reading into two sessions to get the most out of the text;

- Crafting the essay with your audience in mind and giving it a logical and easy-to-follow structure;

- Importance of revising your piece, looking for logical inconsistencies, and proofreading the text.

This way, you will be able to write an essay that has its own identity, its coherence, and great analytical power.

Understanding the Assignment

Let’s start with the first obvious step: understanding the assignment. This actually applies to all types of essays and more. Yet, it is an aspect still underestimated by many students. There are so many who rush headlong into a literary text analysis before even figuring out what they need to do. So, let’s see what are the real steps to follow before writing a literary analysis essay.

First, we need to understand why we are doing this and what is a literary analysis essay. The purpose of a literary analysis essay is to evaluate and examine a particular literary work or some aspect of it. It describes the main idea of the book you have read. You need a strong thesis statement, and you always have to make a proper outline for literary analysis essay.

Secondly, you always need to read the prompt carefully. This should serve as your roadmap, and it will guide you towards specific aspects of the literary work. Those are the aspects you will focus on. You should be able to get the main ideas of what to write already from the prompt. Failure to comprehend the prompt could invalidate the entire work and cause you to lose many valuable hours.

Preparatory Work

Great, so we understood what the purpose of a literary analysis is and that it is crucial to understand the prompt. Now, it’s time to do some preparatory work before you start your draft of the literary analysis paper.

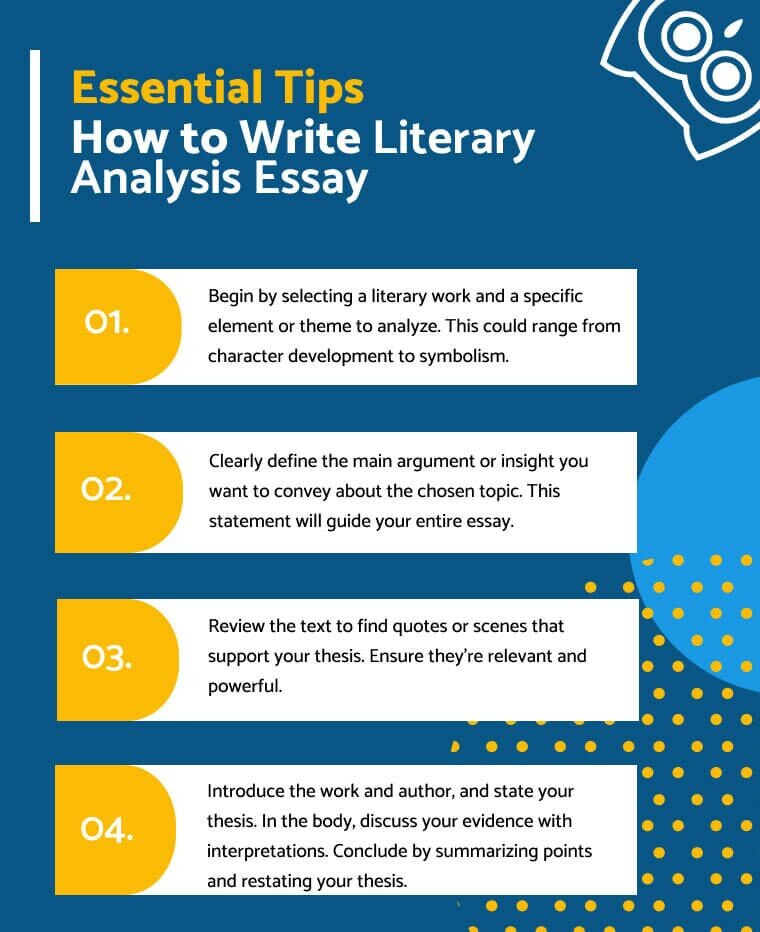

When you write a literary analysis essay, the first thing you should do is select a topic. It is usually impossible to talk about a book or poem in its entirety. Choosing a more specific theme is essential. Firstly, because it will make your literary analysis paper more interesting. Secondly, it will also be easier for you to focus on a single aspect. This could be a single character or what style and literary techniques were used by the author.

At this point, it’s time to consider the broader context. For example, if you have picked a character, think about their character’s development and their significance. If you are analyzing literature looking for a specific theme, try to reflect on how it permeates the narrative and what messages it conveys.

Now, it’s time to frame your literary analysis thesis statement. This should be concise and clear. Think of it as the compass that will guide your analysis. Plus, if it’s clear to you, it’ll be clear to your reader as well. Do not underestimate this point because it can make everything way easier when you start. Finally, feel free to read another book review to get inspired.

Critical Reading

It’s time to read the work you will analyze. We talk about what we call critical reading. This is the heart of all literary criticism, and it consists of immersing yourself in the story. Because of this, it is advised not to read the story just once but twice.

First Reading

The first reading will serve to get a general understanding of the literary texts. This means comprehending the storyline, characters, and major plot developments. You should be able to enjoy it without thinking too much about the assignment. So don’t delve too deeply into analysis just yet.

Second Reading

Your second reading should be much more methodical. Here, you start analyzing things concretely without forgetting what your literary analysis thesis is. Resist the temptation to get lost in the narrative’s flow. Instead, go through a thorough examination and identify key literary elements and literary devices, like the plot, the character development, and the mood of the story. But also other literary elements: the symbolism, the protagonists, whether there is a first-person narrator or a third-person perspective, and whether the author uses figurative language when describing the main conflict.

Pay special attention to how these literary elements are interwoven into the narrative. For example, consider how character development influences the plot. Alternatively, how symbolism enhances the mood. Recognizing these connections will be crucial for your analysis. Finally, and this might be the hardest part, try to see how all of these literary analysis elements collectively contribute to the overall impact of the work. Ask yourself whether it all works together to convey the message the author wants to convey or not.

While reading, it’s important to take notes and annotate the text. Even a brief indication could be enough. You can do this to highlight passages or quotes that strike you as significant. But also to make connections between different parts of the story. These annotations and notes will become invaluable when you start a literary analysis essay.

Crafting the Essay

Now that you’ve laid the groundwork, it’s time to craft your lit analysis piece. This section will help you do just that. The main points focus on:

- Understand who you’re writing for and tailor your text accordingly

- Craft a compelling introduction using a powerful hook and highlighting your thesis statement

- Structure the body paragraphs in a logical and coherent way

- Summarize your analysis, summing up the main points and key takeaway

Follow our suggestions, and you shouldn’t have any issues with your work. But, if you are facing a time crunch and need assistance with writing your literary essay, there is an online essay service that can help you. PapersOwl has been providing expert help to countless students with their literary essays for many years. Their team of professional writers is highly qualified and experienced, ensuring that you receive top-quality literary works. With PapersOwl’s assistance, you can rest assured that your literary essay will be well-written and thoroughly analyzed.

Defining Your Audience

Before putting pen to paper, and even when you are familiar with the literary analysis format, take some time to consider your audience. Who are you writing for? Is it your professor or another reader? This will help you understand what type of analysis you are going to write.

The Title of Your Essay

If you are wondering how to choose a title , you should know that some prefer to choose it when they start, while others do it as the last thing before submitting it. Usually, the literary analysis title includes the author’s name and the name of the text you are evaluating. However, that is not always necessary. What matters is to make it brief and interactive and to catch the reader’s attention immediately.

Take this example of literary analysis: “Unmasking the Symbolism: The Enigmatic Power of the Green Light in The Great Gatsby”.

It works because, while introducing the story, it hints at the theme, the specific focus, and the intrigue of unraveling a mystery.

Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Writing a literary analysis essay starts with understanding the information that fills an outline. This means that writing details that belong in how to write an analytical essay should come fairly easily. If it is a struggle to come up with the meat of the essay, a reread of the novel may be necessary. Like any analysis essay, developing an essay requires structure and outline.

Let’s start with the first. Normally in high schools, the basic structure of any form of academic writing of a literature essay, comprises five paragraphs. One of the paragraphs is used in writing the introduction, three for the body, and the remaining literary analysis paragraph for the conclusion.

Every body paragraph must concentrate on a topic. While writing a five-paragraph structured essay, you need to split your thesis into three major analysis topics connected to your essay. You don’t need to write all the points derivable from the literature but the analysis that backs your thesis.

When you start a paragraph, connect it to the previous paragraph and always use a topic sentence to maintain the focus of the reader. This allows every person to understand the content at a glance.

After that, you should find fitting textual evidence to support the topic sentence and the thesis statement it serves. Using textual evidence involves bringing in a relevant quote from the story and describing its relevance. Such quotes should be well introduced and examined if you want to use them. While it is not mandatory to use them, it is effective because it allows to better analyze the author’s figurative language.

Let’s see a concrete literary analysis example to understand this.

✏️ Topic Sentence : In “The Great Gatsby,” Fitzgerald employs vivid descriptions to characterize Jay Gatsby’s extravagant parties.

✏️ Textual Evidence : Gatsby’s parties are described as “gaudy with primary colors” and filled with “music and the laughter of his guests”.

✏️ Literary Analysis : These vibrant descriptions symbolize Gatsby’s attempt to capture the essence of the American Dream. The use of “gaudy” highlights the emptiness of his pursuits.

Now that you know how to write a literature analysis, it’s crucial to distinguish between analysis and summary. A summary only restates the plot or events of the story. Analysis, on the other hand, tries to unveil the meaning of these events. Let’s use an example from another famous book to illustrate the difference.

✏️ Summary : In “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Atticus Finch defends Tom Robinson, an innocent Black man accused of raping a white woman.

✏️ Literary Analysis : Atticus Finch’s defense of Tom Robinson in “To Kill a Mockingbird” is a rather bitter commentary on the racial prejudices of the time. In the book, Harper Lee highlights the rampant racism that plagued Maycomb society.

Introduction

The literature analysis essay, like other various academic works, has a typical 5-paragraph-structure . The normal procedure for writing an introduction for your literary analysis essay outline is to start with a hook and then go on to mention brief facts about the author and the literature. After that, make sure to present your thesis statement. Before going ahead, let’s use an example of a good literary analysis introduction. This will make it easier to discuss these points singularly.

“On the shores of East Egg, a green light shines through the darkness. The book is “The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald, written in 1925, and this is not just a light. It’s much more. It symbolizes the American Dream chased and rejected by Gatsby and the other characters.”

As an introductory paragraph, this has all the characteristics we are looking for. First, opening statements like this introduce a mysterious element that makes the reader curious. This is the hook. After that, the name of the book, the author, and the release year are presented. Finally, a first glimpse of what your original thesis will be – the connection between the book and the topic of the American Dream.

Afterwards, you can finish writing the introduction paragraph for the literary analysis essay with a clue about the content of the essay’s body. This style of writing a literature essay is known as signposting. Signposting should be done more elaborately while writing longer literary essays.

Body Paragraphs

In a literary analysis essay, the body paragraphs are where you go further into your analysis, looking at specific features of the literature. Each paragraph should focus on a particular aspect, such as character development, theme, or symbolism, and provide textual evidence to back up your interpretation. This structured approach allows for a thorough exploration of the literary work.

“In ‘The Great Gatsby,’ Fitzgerald uses the symbol of the green light to represent Gatsby’s perpetual quest for the unattainable – specifically, his idealized love for Daisy Buchanan. Situated at the end of Daisy’s dock, the green light shines across the bay to Gatsby’s mansion, symbolizing the distance between reality and his dreams. This light is not just a physical beacon; it’s a metaphor for Gatsby’s aspiration and the American Dream itself. Fitzgerald artfully illustrates this through Gatsby’s yearning gaze towards the light, reflecting his deep desire for a future that reconnects him with his past love, yet tragically remains just out of reach. This persistent yearning is a poignant commentary on the nature of aspiration and the illusion of the American Dream.”

The final paragraph, as usual, is the literary analysis conclusion. Writing a conclusion of your essay should be about putting the finishing touches on it. In this section, all you need to do is rephrase your aforementioned main point and supporting points and try to make them clearer to the person who reads them. But also, restate your thesis and add some interesting thoughts.

However, if you don’t understand how to write a conclusion and are just thinking, “ Write my essay for me , please”, there are solutions. At PapersOwl, you get expert writers to help you with your analysis, ensuring you meet your deadline.

Let’s go back to Gatsby’s green light and look at how to write a literary analysis example of a good conclusion:

“Our journey through the green light of “The Great Gatsby” ends here. In this literary essay, we analyzed Fitzgerald’s style and the way this allowed him to grasp the secret of the American Dream. In doing so, we realized that the American Dream is not just about one person’s dream. Rather, it is about everyone who struggles for something that will never be realized.”

Here we have it all: restating the thesis, summing up the main points, understanding the literary devices, and adding some thoughts.

Revising the Essay

At this point, you’re almost done. After you write a literary analysis, it is usually time for a revision. This is where you have a chance to refine and polish your work.

Read your analysis of literature again to check coherence and consistency. This means that your ideas should flow smoothly into each other, thus creating a coherent narrative voice. The tone should always be consistent: it would be a terrible mistake to have a body written in a style and a conclusion in a different style.

Use this final revision to refine the thesis and overall the literary argument essay. If you see there are some flaws in your discourse or some weak and unsupported claims, this is your last chance to fix them. Remember, your thesis should always be clear and effective.

Finally, do not underrate the possibility of spelling and punctuation errors. We all make mistakes of that kind. Read your piece a few times to ensure that every word is written correctly. Nothing bad with a couple of typos, but it’s even better if there is none! Finally, check if you used transition words appropriately.

The revision process involves multiple rounds of review and refinement. You could also consider seeking feedback from peers or professors. This way, you could gain a new perspective on your literary analysis.

In Conclusion

Educational institutions use works like the textual analysis essay to improve the learning abilities of students. Although it might seem complex, with the basic knowledge of how to go about it and the help of experts, you won’t find it difficult. Besides, if everything else fails, you can still try buying essays online at PapersOwl.

In this guide, we went through all the steps necessary to write a successful literary analysis. We began by understanding the assignment’s purpose and then explored preparatory work, the structure of a literature essay critical reading, and the actual crafting. In particular, we showed how to divide it into an introduction, body, and conclusion. Now it’s your turn to write a literary criticism essay!

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

Literary Analysis Essay

Literary Analysis Essay Writing

Last updated on: May 21, 2023

Literary Analysis Essay - Ultimate Guide By Professionals

By: Cordon J.

Reviewed By: Rylee W.

Published on: Dec 3, 2019

A literary analysis essay specifically examines and evaluates a piece of literature or a literary work. It also understands and explains the links between the small parts to their whole information.

It is important for students to understand the meaning and the true essence of literature to write a literary essay.

One of the most difficult assignments for students is writing a literary analysis essay. It can be hard to come up with an original idea or find enough material to write about. You might think you need years of experience in order to create a good paper, but that's not true.

This blog post will show you how easy it can be when you follow the steps given here.Writing such an essay involves the breakdown of a book into small parts and understanding each part separately. It seems easy, right?

Trust us, it is not as hard as good book reports but it may also not be extremely easy. You will have to take into account different approaches and explain them in relation with the chosen literary work.

It is a common high school and college assignment and you can learn everything in this blog.

Continue reading for some useful tips with an example to write a literary analysis essay that will be on point. You can also explore our detailed article on writing an analytical essay .

On this Page

What is a Literary Analysis Essay?

A literary analysis essay is an important kind of essay that focuses on the detailed analysis of the work of literature.

The purpose of a literary analysis essay is to explain why the author has used a specific theme for his work. Or examine the characters, themes, literary devices , figurative language, and settings in the story.

This type of essay encourages students to think about how the book or the short story has been written. And why the author has created this work.

The method used in the literary analysis essay differs from other types of essays. It primarily focuses on the type of work and literature that is being analyzed.

Mostly, you will be going to break down the work into various parts. In order to develop a better understanding of the idea being discussed, each part will be discussed separately.

The essay should explain the choices of the author and point of view along with your answers and personal analysis.

How To Write A Literary Analysis Essay

So how to start a literary analysis essay? The answer to this question is quite simple.

The following sections are required to write an effective literary analysis essay. By following the guidelines given in the following sections, you will be able to craft a winning literary analysis essay.

Introduction

The aim of the introduction is to establish a context for readers. You have to give a brief on the background of the selected topic.

It should contain the name of the author of the literary work along with its title. The introduction should be effective enough to grab the reader’s attention.

In the body section, you have to retell the story that the writer has narrated. It is a good idea to create a summary as it is one of the important tips of literary analysis.

Other than that, you are required to develop ideas and disclose the observed information related to the issue. The ideal length of the body section is around 1000 words.

To write the body section, your observation should be based on evidence and your own style of writing.

It would be great if the body of your essay is divided into three paragraphs. Make a strong argument with facts related to the thesis statement in all of the paragraphs in the body section.

Start writing each paragraph with a topic sentence and use transition words when moving to the next paragraph.

Summarize the important points of your literary analysis essay in this section. It is important to compose a short and strong conclusion to help you make a final impression of your essay.

Pay attention that this section does not contain any new information. It should provide a sense of completion by restating the main idea with a short description of your arguments. End the conclusion with your supporting details.

You have to explain why the book is important. Also, elaborate on the means that the authors used to convey her/his opinion regarding the issue.

For further understanding, here is a downloadable literary analysis essay outline. This outline will help you structure and format your essay properly and earn an A easily.

DOWNLOADABLE LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY OUTLINE (PDF)

Types of Literary Analysis Essay

- Close reading - This method involves attentive reading and detailed analysis. No need for a lot of knowledge and inspiration to write an essay that shows your creative skills.

- Theoretical - In this type, you will rely on theories related to the selected topic.

- Historical - This type of essay concerns the discipline of history. Sometimes historical analysis is required to explain events in detail.

- Applied - This type involves analysis of a specific issue from a practical perspective.

- Comparative - This type of writing is based on when two or more alternatives are compared

Examples of Literary Analysis Essay

Examples are great to understand any concept, especially if it is related to writing. Below are some great literary analysis essay examples that showcase how this type of essay is written.

A ROSE FOR EMILY LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

THE GREAT GATSBY LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

THE YELLOW WALLPAPER LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

If you do not have experience in writing essays, this will be a very chaotic process for you. In that case, it is very important for you to conduct good research on the topic before writing.

There are two important points that you should keep in mind when writing a literary analysis essay.

First, remember that it is very important to select a topic in which you are interested. Choose something that really inspires you. This will help you to catch the attention of a reader.

The selected topic should reflect the main idea of writing. In addition to that, it should also express your point of view as well.

Another important thing is to draft a good outline for your literary analysis essay. It will help you to define a central point and division of this into parts for further discussion.

Literary Analysis Essay Topics

Literary analysis essays are mostly based on artistic works like books, movies, paintings, and other forms of art. However, generally, students choose novels and books to write their literary essays.

Some cool, fresh, and good topics and ideas are listed below:

- Role of the Three Witches in flaming Macbeth’s ambition.

- Analyze the themes of the Play Antigone,

- Discuss Ajax as a tragic hero.

- The Judgement of Paris: Analyze the Reasons and their Consequences.

- Oedipus Rex: A Doomed Son or a Conqueror?

- Describe the Oedipus complex and Electra complex in relation to their respective myths.

- Betrayal is a common theme of Shakespearean tragedies. Discuss

- Identify and analyze the traits of history in T.S Eliot’s ‘Gerontion’.

- Analyze the theme of identity crisis in The Great Gatsby.

- Analyze the writing style of Emily Dickinson.

If you are still in doubt then there is nothing bad in getting professional writers’ help.

We at 5StarEssays.com can help you get a custom paper as per your specified requirements with our do essay for me service.

Our essay writers will help you write outstanding literary essays or any other type of essay. Such as compare and contrast essays, descriptive essays, rhetorical essays. We cover all of these.

So don’t waste your time browsing the internet and place your order now to get your well-written custom paper.

Frequently Asked Questions

What should a literary analysis essay include.

A good literary analysis essay must include a proper and in-depth explanation of your ideas. They must be backed with examples and evidence from the text. Textual evidence includes summaries, paraphrased text, original work details, and direct quotes.

What are the 4 components of literary analysis?

Here are the 4 essential parts of a literary analysis essay;

No literary work is explained properly without discussing and explaining these 4 things.

How do you start a literary analysis essay?

Start your literary analysis essay with the name of the work and the title. Hook your readers by introducing the main ideas that you will discuss in your essay and engage them from the start.

How do you do a literary analysis?

In a literary analysis essay, you study the text closely, understand and interpret its meanings. And try to find out the reasons behind why the author has used certain symbols, themes, and objects in the work.

Why is literary analysis important?

It encourages the students to think beyond their existing knowledge, experiences, and belief and build empathy. This helps in improving the writing skills also.

What is the fundamental characteristic of a literary analysis essay?

Interpretation is the fundamental and important feature of a literary analysis essay. The essay is based on how well the writer explains and interprets the work.

Law, Finance Essay

Cordon. is a published author and writing specialist. He has worked in the publishing industry for many years, providing writing services and digital content. His own writing career began with a focus on literature and linguistics, which he continues to pursue. Cordon is an engaging and professional individual, always looking to help others achieve their goals.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- Interesting Literary Analysis Essay Topics for Students

- Write a Perfect Literary Analysis Essay Outline

People Also Read

- writing a conclusion for an argumentative essay

- descriptive essay outline

- how to start a research paper

- qualitative vs quantitative research

- college application essay

Burdened With Assignments?

Advertisement

- Homework Services: Essay Topics Generator

© 2024 - All rights reserved

Essay 3: A How-To Guide

What makes an effective researched argument.

Goal: The goal of any literary research paper is to add an original interpretation to a scholarly conversation about a literary text. Take a look at how rhetorical and literary theorist Kenneth Burke describes all acts of researched writing:

Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment or gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally’s assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress. [1] [2]

In a researched argument, you should:

- Establish the scholarly conversation that you are entering.

- Engage in debate with other scholars by analyzing the literary text

- Form an original interpretation about the literary text through close reading

Introductions

- Develops an interpretive or intellectual problem—either drawn from research into how other scholars have interpreted the poem or short story or drawn from a detail in the story itself that bears some tension, irony, ambiguity, or disjunction that connects to a larger scholarly conversation.

- Adds new evidence

- Adds a new interpretation

- Disagrees with a previous interpretation

Sample Introductions

The Introduction should accomplish four steps:

- Establish an Interpretive Problem: Observe the juxtaposing elements in the story that have caused an interpretive gap or tension and establish the significance of these elements.

- Describe a Major Interpretive Debate: Describe, in a couple of sentences, how various scholars have approached this text, genre, or work from this poet/time period. What problems have emerged in writing about this exhibit? What conversation are you joining?

- Thesis Statement: After reviewing the previous scholarship, state your claim. What are you arguing in this paper?

- Road Map: How are you going to support your argument? What’s the layout for this paper?

Take a look at the sample introductions from Laura Wilder and Joanna Wolfe’s Digging into Literature. [3] Where/How does this introduction accomplish each of these four steps?

Schwab, Melinda. “A Watch for Emily.” Studies in Short Fiction 28.2 (1991): 215-17.

The critical attention given to the subject of time in Faulkner most certainly fills as many pages as the longest novel of Yoknapatawpha County. A goodly number of those pages of criticism deal with the well-known short story, “A Rose for Emily.” Several scholars, most notably Paul McGlynn, have worked to untangle the confusing chronology of this work (461-62). Others have given a variety of symbolic and psychological reasons for Emily Grierson’s inability (or refusal) to acknowledge the passage of time. Yet in all of this careful literary analysis, no one has discussed one troubling and therefore highly significant detail. When we first meet Miss Emily, she carries in a pocket somewhere within her clothing an “invisible watch ticking at the end of [a] gold chain” (Faulkner 121). What would a woman like Emily Grierson, who seems to us fixed in the past and oblivious to any passing of time, need with a watch? An awareness of the significance of this watch, however, is crucial for a clear understanding of Miss Emily herself. The watch’s placement in her pocket, its unusually loud ticking, and the chain to which it is attached illustrate both her attempts to control the passage of years and the consequences of such an ultimately futile effort (215).

Fick, Thomas, and Eva Gold. “’He Liked Men’: Homer, Homosexuality, and the Culture of Manhood in Faulkner’s ‘A Rose for Emily.’” Eureka Studies in Teaching Short Fiction 8.1 (2007): 99-107.

Over the last few years critics have discussed homosexuality in Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily,” one of Faulkner’s most frequently anthologized works and a mainstay of literature classes at all levels. Hal Blythe, for example, asserts outright that Homer Barron is gay, while in a more nuanced reading James Wallace argues that the narrator merely wishes to suggest that Barron is homosexual in order to implicate the reader in a culture of gossip (Blythe 49-50; Wallace 105-07). Both readings rest on this comment by the narrator: “Then we said, ‘She will persuade him yet,’ because Homer himself had remarked—he liked men, and it was known that he drank with the younger men at the Elks’ Club—that he was not a marrying man” (Faulkner 126)…While we agree that the narrator’s comment suggests something important about Homer’s sexual orientation, in contrast with Blythe we believe that it says Homer is combatively heterosexual.

- Engages in conversation with literary scholars throughout the essay, showing how their interpretation affirms, contrasts, contradicts and resolves the interpretive problem posed by literary scholars.

- Uses contextual and argumentative sources to support and challenge their analysis of the text.

- Uses close reading strategies to deeply analyze the literary text.

- Resolves the interpretive problem through a deep analysis of the text.

Conclusion:

- Discuss the significance of their analysis to the research being done on that area of literary study.

- Identify one question or problem that still remains for the field of scholarship on the subject.

Sample Researched Argument

The White Gaze in “On Being Brought from Africa to America”

Paragraph 1

Phillis Wheatley was born in West Africa, captured at a young age, and sold into slavery. Despite the violent history that she lives through, her poem “On Being Brought from Africa to America” opens by expressing gratitude towards a system only referred to in the poem as “mercy.” Due to this discrepancy between the violent history she lives through and the evangelical understanding of that history expressed in the poem, critics have long questioned whether her poetry is a true expression of herself. No one tells the story of Wheatley’s legacy better than Henry Louis Gates, Jr. who, in his article “Phillis Wheatley on Trial,” describes how the Black Nationalist movement zeroed in on “On Being Brought from Africa to America” because there was no outcry in the poem—no objection to being brought to America. The poem was absent of the longing to return back to Africa that the Black Nationalist movement invested in (Gates 87). These critics also decried her poetic style, which imitated White, Enlightenment poets like Alexander Pope (Baraka, Barnum, and Thurman, as cited in Gates 87). Despite this backlash to Wheatley’s poetry, the authenticity of her work remains hotly debated today. Debates over her poetry were revived in the 80’s/90’s when scholars like William J. Scheik, Sondra O’Neale, James Levernier, and Mark Edelman Boren began to document how the biblical allusions and metaphors of her poetry, when read closely, were more subversive than appeared on first glance. This is how Wheatley has continued to be read today, with scholars questioning to what extent her subversions were explicit enough to change the cultural landscape of eighteenth-century America.

Paragraph 2

This paper will argue that the binary readings of Wheatley presented—one in which she is an “Uncle Tom figure” (Gross, as cited in Gates 87) and another in which she is a subversive, revolutionary poet (Levernier)—are both self-consciously represented by Wheatley in the poem. The poem is an example of early discussions of Black identity formation, one in which she is locked into two modes of being: gratitude and resistance. We will start by looking at the most contentious aspects of the poem—the gratitude for Christianity. Looking at the rhetorical construction of the speaker/reader relationship, we will uncover how the poem imagines her White, Christian reader and, in turn, how that White, Christian reader imagines her subjectivity. Following, we will then look at the allusions to the Transatlantic Slave Trade to affirm that these allusions demonstrate the subversiveness of her poetry. Subversive both in demonstrating the White reader’s understanding of her diasporic identity and in showcasing the fluidity of that identity in its early formation.

Paragraph 3

Arguments against reading Wheatley in a subversive light hinge on the evangelical Christian sentiments that open the first lines, particularly the idea that Africa consists of a “pagan land.” As Henry Louis Gates discusses, for Black nationalist thinkers, her description of her African origins as a “pagan” place was a rejection of her Black identity, an attempt to assimilate to her white readership. However, these opening lines are particularly interesting because of the pronoun usage in the opening lines. The opening line says, “’Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,” (Wheatley 1). While on the surface the line looks like a benign Christian gratitude for salvation, the pronoun usage in these early lines suggests an alienation that Wheatley feels between herself and her African origins. She has been “brought,” perhaps we might imagine “removed” from her land. The disjunction between “me” and “my pagan land,” suggests a fundamental bifurcation of the self that begins the poem. In many accounts of Wheatley’s Black identity, she is conceived to be assimilationist because her poem suggests, “ludicrous [departure] from the huge black voices that splintered southern nights with their hollers, chants, arwhoolies, and ballits,” (Baraka, as cited in Gates 87). But, I want to suggest that the bifurcation of the self that begins the poem, which initially may look like an assimilationist rejection of Africa—is actually a meditation on how the transatlantic slave trade has shaped her identity—an early example of Du Bois’s “double consciousness” of African-American identities.

Paragraph 4

As many scholars have noted, the poem seems to subversively contend with her relationship with evangelical Christianity, which we may note was a condition of her education. The reference to “mercy” in the first line is particularly troubling—as we know that it was not mercy, but the transatlantic slave trade that brought her to the U.S. How are we to read this reference to mercy? Are we to read it as a moment of cognitive dissonance between Wheatley’s understanding of her history and herself? Are we to read it as an imitation of forms of poetry that she was reading as part of her education? I suggest that we read it as ironic. In both of the interpretations mentioned above, there is a fundamental tension between the reader’s awareness and, supposedly, Wheatley’s awareness. In fact, the title page of the original publication announces that she was a “servant to John Wheatley”—the 18th century reader would have been well-aware of the implications of this position of servitude, would have been aware of the conditions of life that brought Africans to the U.S. Rather than looking at this line for absence of reference to the transatlantic slave trade, I think we should attend to the passivity of the line—the lack of agency she expresses in this opening of the poem. The passive construction of the sentence gives agency to mercy rather than any singular person for the double-consciousness that she is expressing in the rest of the line. It is because of this passivity that she is able to call the land “pagan,” the italicization of which suggests irony. In fact, Mark Edelman Boren suggests that stress is being put on the term pagan in order to undercut the conventional association between the idea of Africa as a pagan landscape and the Africa that Wheatley comes from (45). In this opening line, Wheatley seems to be undercutting the conventional notions that the reader might have of African poets—undercutting the idea that they are grateful for the violence being inflicted on them.

Paragraph 5