Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Gender Inequality — A Discussion on Gender-Based Violence

Gender-based Violence: Effects and Prevention Methods

- Categories: Gender Gender Inequality Race and Gender

About this sample

Words: 382 |

Published: Jul 17, 2018

Words: 382 | Page: 1 | 2 min read

Gender-based violence: essay introduction

Works cited.

- World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/9789241564625_eng.pdf

- United Nations. (n.d.). Violence against women: Facts everyone should know. Retrieved from https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures

- Heise, L. L., & Kotsadam, A. (2015). Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: An analysis of data from population-based surveys. The Lancet Global Health, 3(6), e332-e340. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00013-3

- García-Moreno, C., Hegarty, K., d'Oliveira, A. F., Koziol-McLain, J., Colombini, M., & Feder, G. (2015). The health-systems response to violence against women. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1567-1579. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7

- Jewkes, R., Flood, M., & Lang, J. (2015). From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: A conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1580-1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61683-4

- United Nations Development Programme. (n.d.). Ending violence against women. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-5-gender-equality/overview/ending-violence-against-women.html

- Krug, E. G., Mercy, J. A., Dahlberg, L. L., & Zwi, A. B. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360(9339), 1083-1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0

- Human Rights Watch. (n.d.). Violence against women. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/topic/womens-rights/violence-against-women

- United Nations Women. (n.d.). Gender-based violence. Retrieved from https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures/gender-based-violence

- World Bank. (n.d.). Gender-based violence. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/gbv

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1893 words

3 pages / 1287 words

3 pages / 1275 words

1 pages / 598 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Gender Inequality

The American Dream is a concept deeply ingrained in the fabric of American society, representing the belief that anyone, regardless of background, can achieve success and prosperity through hard work and determination. However, [...]

It is highly important nowadays to discuss the issue of gender discrimination in workplace. This essay would focus on the ethical concern of gender inequality, what causes it, the inequalities it perpetuates, and what steps can [...]

While women have made major strides in fighting traditional social standards, gender hierarchies continue to suppress women socially and economically to this day. Gender relations are hierarchical in as much as men and women are [...]

Fatany, Samar. 'The Status of Women in Saudi Arabia.' Arab News. 12 October 2004. Web. 19 February 2019.Openstax. 'Introduction to Sociology.' OpenStax CNX. Web. Retrieved from Web.

The debate over importance of workplace diversity is not new. It has been in discussion for last 6 decades. Many researchers, academicians, human resource professionals and entrepreneurs have debated about its benefits, [...]

The “glass ceiling” has kept ladies away from specific positions and openings in the work environment. Ladies are stereotyped as low maintenance, lower grade workers with restricted open doors for preparing and headway due to [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Gender-based violence: Teaching about its root causes is necessary to address it

Assistant Professor of Educational Foundations, University of Windsor

Disclosure statement

Catherine Vanner receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

University of Windsor provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

University of Windsor provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

In 2022, 184 women and girls were killed by violence in Canada . This number has steadily increased in each of the past three years; 148 women and girls were killed in 2019, 172 in 2020 and 177 in 2021.

There were 6,423 incidences of anti-2SLGBTQIA+ protests and online hate in Canada in the first three months of 2023 alone. Expressions of hate toward trans and non-binary people and 2SLGBTQIA+ people more broadly have been rising.

Transphobia and femicide are both forms of gender-based violence, defined as any form of violence directed toward somebody because of their gender, gender identity, gender expression or perceived gender .

My team of researchers, The Gender-Based Violence Teaching Network , created resources, professional development and a teaching toolkit to support more teachers to effectively teach students about the root causes and consequences of different forms of gender-based violence.

Devastating effects

Gender-based violence has devastating effects for those who experience it. In addition to immediate physical, psychological and/or sexual harm, it leads to increased economic insecurity and has detrimental impacts on mental health .

Gender-based violence is prevalent in our society. A 2021 survey by the Canadian Women’s Foundation showed that two-thirds of 1,515 Canadian respondents know a woman who has experienced physical, sexual or emotional abuse. Despite this high prevalence, it is often not examined in schools as a social issue.

My analysis of Ontario secondary school curricula showed that some form of gender-based violence is mentioned at all grade levels. It is most frequently mentioned in upper-level optional social sciences and humanities courses (such as Grade 11 Gender Studies or Grade 12 Challenge and Change in Society).

These elective courses are also more likely to help students examine how gender-based violence is influenced by systems of power, discrimination and social constructs , including through the intersections of gender and racialization, disability and socioeconomic status.

Need to learn how violence is normalized

Teachers told me that, unfortunately, these elective courses are not always offered and, when they are, they are most often taken by students already familiar with these ideas.

This means most Ontario students never learn about the connection between acts of violence and broader structures that normalize gender-based violence by discriminating against girls, women and 2SLGBTQIA+ people.

For example, Indigenous women and girls are 12 times more likely to be murdered or missing than other women in Canada. This disproportionate violence results from centuries of colonization, which continues to manifest through multigenerational and intergenerational trauma, social and economic marginalization, and institutional practices and social behaviours that maintain the status quo and ignore the agency and expertise of Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQIA+ people.

Read more: Missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls: An epidemic on both sides of the Medicine Line

Overlooking power discrepancies

There are required courses that mention some forms of gender-based violence, most notably Grade 9 Health and Physical Education . However, my analysis of this curriculum found it frames gender-based violence as an issue of individual responsibility , overlooking the ways power discrepancies can influence the situation and impact a person’s ability to provide consent or respond to violence.

There are also brief mentions of several gender-based violence issues in the Grade 10 Canadian History and Civics and Citizenship courses, including missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. My examination of the curriculum and teachers’ experience teaching it, however, demonstrates these curricula do not prompt critical analysis of the social causes that led to these acts of violence.

What effective teaching looks like

My research demonstrated that some teachers are teaching about gender-based violence issues. They explain that effective teaching about gender-based violence involves grappling with the power and privilege of both students and teachers , intentionally cultivating relationships with and between students and with community resources and considering the root causes of gender-based violence as connected to patriarchy, colonialism, heteronormativity and cisnormativity.

Students call for education that conveys the holistic consequences for victims as real people, not just statistics, and that empowers them to understand and prevent gender-based violence in their lives and communities .

Teaching toolkit

My team created resources and professional development to respond to teachers’ concerns that they lacked sufficient training and materials about gender-based violence, and that this discourages teaching about it.

Our Teaching About Gender-Based Violence Toolkit is available on our project website. The toolkit has lesson plans, guidance notes and other teaching materials to support teachers to address gender-based violence topics. It aligns to Grade 8-12 Ontario curriculum expectations.

Topics addressed include sexual assault, consent and healthy relationships, human trafficking, transphobia and homophobia, gender policing, cisnormativity and heteronormativity, missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls and Two-Spirit people and intimate partner violence.

More directly addressing gender-based violence through education can help the upcoming generation of Canadians understand how gender-based violence manifests across our society.

More education needed

The ongoing disappearance and murder of Indigenous women, girls and Two-Spirit people, the proliferation of hate toward 2SLGBTQIA+ people , the unmanageable demand for women’s shelters and the emergence of new forms of sexual violence facilitated by technology show the importance of more education about gender-based violence.

Broader awareness of its root causes and devastating consequences is necessary to better address it.

Teachers are uniquely placed to support the development of students’ understanding of gender-based violence. All educators are encouraged to explore the resources that we have created to help students understand that, tragically, gender-based violence exists all around them.

We need to teach students what it looks like and why it happens before we can empower them to collectively act to circumvent it in their lives and communities.

- Violence against women

- High school

- Transphobia

- Gender-based violence

- National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women

- missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls

- MMIWG report

- Listen to this article

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 181,500 academics and researchers from 4,930 institutions.

Register now

Introduction

What is gender-based violence.

“GBV is an umbrella term for any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person’s will, and that is based on socially ascribed gender differences between males and females. Acts of GBV violate a number of universal human rights protected by international instruments and conventions. Many, but not all, forms of GBV are illegal and criminal acts in national laws and policies.

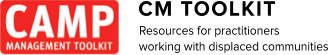

Around the world, GBV has a greater impact on women and girls than on men and boys. The term gender-based violence is often used interchangeably with the term violence against women.

The term gender-based violence highlights the gender dimension of these types of acts; in other words, the relationship between females’ subordinate status in society and their increased vulnerability to violence. It is important to note, however, that men and boys may also be victims of gender-based violence, especially sexual violence.”

Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2005. Guidelines for GBV Interventions in Humanitarian Settings: Focusing on Prevention of and Response to Sexual Violence in Emergencies, page 7.

Note that sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) is also used by some agencies to refer to gender-based violence (GBV).

GBV exists across the world and in a range of contexts. Situations of displacement often increase the risks of GBV as community protective mechanisms may be weakened or destroyed. Displacement sites, instead of providing a safe environment for their residents, can sometimes increase exposure to violence.

Worldwide, GBV occurs both within the family and community, and is perpetrated by persons in positions of power. This may include spouse/partners, parents, members of extended family, police, guards, armed forces/groups, peacekeepers and humanitarian aid workers.

Sexual violence is the most obvious and widely recognised type of GBV. However, all forms of GBV can increase in humanitarian contexts, including domestic violence, trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation, early and forced marriage, harmful traditional practices such as female genital mutilation, sexual exploitation, forced prostitution, honour killings and denial of the right to widow inheritance. For example, living under stress in overcrowded spaces can lead to increased domestic violence, and early or forced marriage may be used as a protection mechanism or a measure to address economic hardship.

In camp settings vulnerable groups are particularly exposed to GBV risks. It is important to note that although the vast majority of those who experience GBV are women and girls, men and boys may also experience violence, including of a sexual nature, based on their gender. In all cases, survivors of violence should receive timely referrals to confidential and appropriate care and support.

While women and girls remain the most at risk of GBV, it is important to acknowledge that men and boys may also experience GBV and are provided with the support they need. As in the case of providing services for women and girls, assisting male survivors of violence requires specialised expertise.

Gender-based Violence Against Men and Boys

GBV against men and boys may include both sexual violence and other forms of violence in which men are targeted based on the socially ascribed roles of men. Men and boys may be exposed to several forms of GBV. This includes physical, sexual and psychological violence against men perceived to be transgressing ascribed gender roles; for example, transgender individuals, men who have sex with men, or men and boys who do not conform to the expected norms of masculinity in the culture.

The Camp Management Agency plays a pivotal role in decreasing the risks of these multiple forms of violence by ensuring that the needs of all persons are understood, addressed and monitored across sectors intervening in the camp. Assisting GBV survivors in a way that meets their specialised needs requires careful consideration and collaboration between multiple sectors and national stakeholders. It is the responsibility of the Camp Management Agency to work within a protection framework and understand the protection risks that women, girls, men and boys face.

Factors Contributing to GBV

Gender discrimination is an underlying cause of GBV. The risks of GBV are often heightened during conflict or while in flight, and can continue during displacement. The environment of the camp must ensure that everyone living there is safe and protected. The following are examples of how camp responses may exacerbate the risk to GBV:

- registration: Women not individually registered may not be able to access services, food and non food items, and as a result may be at higher risk of sexual exploitation and abuse.

- camp layout: Female-headed households who arrive and register once much of the camp is already established may be pushed toward the camp outskirts. This isolation can expose them to opportunistic rape and/or attack from hostile surrounding communities, bandits or armed actors. Camp layout should take into consideration, among others, the location of military posts and markets.

- site infrastructure: Where service delivery is poor or inadequate, women and girls are most often tasked with leaving the camp and traveling long distances in search of food, fuel and water. This exposes them to risk of attack.

- psychosocial stress: The danger and uncertainty of emergencies and displacement place great strain on individuals, families and communities, often contributing to the likelihood of violence within the home or family.

- livelihoods: The absence of livelihoods in the camp might lead individuals to engage in maladaptive practices, such as child marriage or sex work.

- distributions: How, where and when food and non-food items are targeted and distributed can either increase or reduce the risks to women and girls. Distribution points should be safely accessible to women and girls, and distribution monitoring should look at safety issues that arise both during and after the distribution.

- others factors, like overcrowding in camps, poor or no lighting in common areas, unlit and unlockable latrines, poor access to education and vocational activities, absence of women or child friendly spaces can increase the risk of GBV during the staying in a camp.

Certain groups may also be at heightened risk of GBV, such as female heads of households, persons with physical or mental disabilities, or associated with armed forces or groups. Adolescent boys and girls, particularly those who are unaccompanied, are in foster families, or are child mothers, are also a group subject to high levels of GBV. Notably, adolescent girls may lack social power due to the combination of their age and gender, and often missed in traditional child protection interventions in emergencies, such as child-friendly spaces, but also cannot be reached with the same programming used to reach women.

☞ For more information on GBV, see the Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s Guidelines for Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings in the References section.

The consequences of GBV can be physical, psychological and social in nature. The below table, although not exhaustive, lists a few examples of possible consequences.

☞ For more information on the health effects of GBV, see World Health Organization (WHO), 1997. Violence Against

A woman who has experienced sexual assault has just 72 hours to access care to prevent the potential transmission of HIV or infections, 120 hours to prevent unwanted pregnancy, and sometimes just a few hours to ensure that life-threatening injuries do not become fatal. Although medical services are essential, they are not the only lifesaving aspect of emergency GBV interventions. The Camp Management Agency should advocate for case management, including both basic psychological first aid and safety planning, which is also critical and necessitates the establishment of specialised GBV programming. Wherever possible, these services should build on and work in collaboration with existing support structures, such as local civil society organisations and governmental social service institutions. Finally, efforts to reduce risks to women and girls must be mainstreamed across all sectors in humanitarian response. The Camp Management Agency plays an essential role in reducing risks, preventing GBV and ensuring that all actors recognise and take responsibility in this area.

Chapter Listing

Would you like to work with us? Apply to become our Seconded National Expert: Gender-based Violence by 13 May.

What is gender-based violence?

Gender-based violence is a phenomenon deeply rooted in gender inequality, and continues to be one of the most notable human rights violations within all societies. Gender-based violence is violence directed against a person because of their gender. Both women and men experience gender-based violence but the majority of victims are women and girls.

Gender-based violence and violence against women are terms that are often used interchangeably as it has been widely acknowledged that most gender-based violence is inflicted on women and girls, by men. However, using the ‘gender-based’ aspect is important as it highlights the fact that many forms of violence against women are rooted in power inequalities between women and men. The terms are used interchangeably throughout EIGE’s work, reflecting the disproportionate number of these particular crimes against women.

What forms of gender-based violence are there?

The Istanbul Convention (Council of Europe, Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence ), as the benchmark for international legislation on tackling gender-based violence, frames gender-based violence and violence against women as a gendered act which is ‘a violation of human rights and a form of discrimination against women’. Under the Istanbul Convention acts of gender-based violence are emphasised as resulting in ‘physical, sexual, psychological or economic harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coerican or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occuring in public or in private life.’

EIGE's work on gender-based violence

Female genital mutilation in the EU

Cyber violence against women

Administrative data collection on violence against women

Risk assessment of intimate partner violence

Costs of gender-based violence in the EU

In focus: 16 Days of Activism against Gender-based Violence

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to E-mail

UN Women kicks off a UN-wide annual campaign on 25 November, the International Day to End Violence against Women.

Over the following 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence , we are asking governments, institutions, and citizens to show us how much the world cares about ending violence against women and girls under the theme " UNITE! Invest to prevent violence against women and girls ".

Led by civil society groups around the world, the campaign is supported by the United Nations through the Secretary General’s initiative, UNITE by 2030 to End Violence against Women .

0.2 per cent of global Official Development Assistance is directed to gender-based violence prevention.

25 per cent of countries have systems to track budget allocations for gender equality.

78 per cent of countries have budgetary commitments to implement legislation addressing violence against women.

Some 736 million women — almost one in three — have been subjected to physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence , non-partner sexual violence, or both, at least once in their lives. More than four in five women and girls (86 per cent) are living in countries without robust legal protection , or in countries for which data are not readily available.

No country is within reach of eradicating intimate partner violence . Despite the scale of the problem and these worrying trends, financial commitments to violence prevention remain limited. Investing in preventing violence against women and girls is crucial to achieving gender equality by 2030, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals.

We urge everyone to call on leaders worldwide to increase investments in preventing violence from happening in the first place.

Every effort invested in preventing violence against women is a step towards a safer, more equal, and prosperous world.

There's #NoExcuse for gender-based violence

Facts and figures: Ending violence against women

Ten ways to prevent violence against women

Making investment in violence prevention a priority

What is gender-responsive budgeting?

How funding women’s organizations prevents violence against women.

Women's rights organizations are essential in tackling gender-based violence and driving progress toward a more equitable and violence-free world for women and girls. Despite the critical role of feminist activism to end violence against women, there has been a surge in anti-rights movements and backlash against women human rights defenders globally.

Here are four reasons why funding women’s organizations is essential for ending violence against women and girls.

Join the campaign!

Five essential facts about femicide

Take action: 10 ways you can help end violence against women

Creating safe digital spaces free of trolls, doxing, and hate speech

The signs of relationship abuse

Types of violence against women

Impact stories.

Leaders discuss best practices for gender-responsive policing at Copenhagen conference

South African women’s group trains police to respond to gender-based violence

UN Women’s Oasis programme empowers Jordanian and Syrian women

Spotlight Initiative programme helps Ugandan survivors of gender-based violence advocate for their rights

Women’s shelters in Sri Lanka support survivors of gender-based violence

How men and boys can help women survivors of gender-based violence: Shu Huang’s story

News and events.

Less than 1 per cent of aid spending targets gender-based violence, according to new reports

UN Women calls for bold investments to end violence against women in light of new report showing prevention is severely underfunded

Speech: Time to get serious about ending violence, allocating serious resources

Official UN commemoration of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women

Call to action: UNiTE! Invest to prevent violence against women and girls!

International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women media advisory

UNITE! Invest to prevent violence against women and girls

- Ending violence against women and girls

- Open access

- Published: 08 March 2019

Social norms and beliefs about gender based violence scale: a measure for use with gender based violence prevention programs in low-resource and humanitarian settings

- Nancy Perrin 1 ,

- Mendy Marsh 2 ,

- Amber Clough 1 ,

- Amelie Desgroppes 3 ,

- Clement Yope Phanuel 4 ,

- Ali Abdi 3 ,

- Francesco Kaburu 3 ,

- Silje Heitmann 5 ,

- Masumi Yamashina 6 ,

- Brendan Ross 7 ,

- Sophie Read-Hamilton 8 ,

- Rachael Turner 1 ,

- Lori Heise 1 , 9 &

- Nancy Glass 1

Conflict and Health volume 13 , Article number: 6 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

163k Accesses

63 Citations

43 Altmetric

Metrics details

Gender-based violence (GBV) primary prevention programs seek to facilitate change by addressing the underlying causes and drivers of violence against women and girls at a population level. Social norms are contextually and socially derived collective expectations of appropriate behaviors. Harmful social norms that sustain GBV include women’s sexual purity, protecting family honor over women’s safety, and men’s authority to discipline women and children. To evaluate the impact of GBV prevention programs, our team sought to develop a brief, valid, and reliable measure to examine change over time in harmful social norms and personal beliefs that maintain and tolerate sexual violence and other forms of GBV against women and girls in low resource and complex humanitarian settings.

The development and testing of the scale was conducted in two phases: 1) formative phase of qualitative inquiry to identify social norms and personal beliefs that sustain and justify GBV perpetration against women and girls; and 2) testing phase using quantitative methods to conduct a psychometric evaluation of the new scale in targeted areas of Somalia and South Sudan.

The Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale was administered to 602 randomly selected men ( N = 301) and women (N = 301) community members age 15 years and older across Mogadishu, Somalia and Yei and Warrup, South Sudan. The psychometric properties of the 30-item scale are strong. Each of the three subscales, “Response to Sexual Violence,” “Protecting Family Honor,” and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” within the two domains, personal beliefs and injunctive social norms, illustrate good factor structure, acceptable internal consistency, reliability, and are supported by the significance of the hypothesized group differences.

Conclusions

We encourage and recommend that researchers and practitioners apply the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale in different humanitarian and global LMIC settings and collect parallel data on a range of GBV outcomes. This will allow us to further validate the scale by triangulating its findings with GBV experiences and perpetration and assess its generalizability across diverse settings.

Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV) remains one of the most prevalent and persistent issues facing women and girls globally [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Conflict and other humanitarian emergencies place women and girls at increased risk of many forms of GBV [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) 2015 Guidelines for Integrating GBV Interventions in Humanitarian Action defines GBV as any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and that is based on socially ascribed (i.e., gender) differences between females and males. It includes acts that inflict physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion, and other deprivations of liberty. These harmful acts can occur in public and in private [ 8 ]. There continues to be limited global information on the burden of GBV in humanitarian emergencies. One systematic review found that approximately one in five refugees or displaced women in complex humanitarian settings experienced sexual violence, though this is likely an underestimation of the true prevalence given the many barriers to survivors’ disclosure of GBV [ 9 ]. A recent population-based survey on GBV across the three regions of Somalia examined typology and scope of GBV victimization with 2376 women (15 years and older). The study found that among women, 35.6% (95% CI 33.4 to 37.9) reported lifetime experiences of physical or sexual intimate partner violence (IPV) and 16.5% (95% CI 15.1 to 18.1) reported lifetime experience of physical or sexual non-partner violence (NPV) since the age of 15 years. Women at greatest risk of GBV (IPV and NPV) included membership in a minority clan, displacement from home because of conflict or natural disaster, husband/partner use of khat (e.g., leaves chewed or drunk as a stimulant), exposure to parental violence and violence during childhood. Women survivors of GBV consistently report negative impacts on physical, mental and reproductive health. Often negative health and social consequences are never addressed because women do not disclose GBV to providers or access health care or other services (e.g., protection, legal, traditional authorities) because of social norms that blame the woman for the assault (e.g., she was out alone after dark, she was not modestly dressed, she is working outside the home), norms that prioritize protecting family honor over safety of the survivor, and institutional acceptance of GBV as a normal and expected part of displacement and conflict [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ].

GBV primary prevention in humanitarian settings

GBV primary prevention programs seek to facilitate change by addressing the underlying causes and drivers of GBV at a population level. Such programs have traditionally included initiatives to economically empower girls and women, enhanced legal protections for GBV, enshrining women’s rights and gender equality within national legislation and policy, and other measures to promote gender equality. Increasingly, programs are also targeting transformation of social norms that justify and sustain acceptance of GBV. Social norms are contextually and socially derived collective expectations of appropriate behaviors [ 14 ]. Families and communities have shared beliefs and unspoken rules that both proscribe and prescribe behaviors that implicitly convey that GBV against women is acceptable, even normal [ 15 , 16 ]. This includes social norms pertaining to sexual purity, family honor, and men’s authority over women and children in the family. Community leaders, institutions, and service providers, such as health care, education and law enforcement, can reinforce harmful social norms by, for example, blaming women and girls for the sexual assault they experience, or by justifying a husband’s use of physical violence as a means to discipline his wife. Both behaviors are viewed as essential to protect the family’s reputation in the larger community [ 16 ].

Diverse academic disciplines have developed different theories to explain the complexity of social norms and their influence on behavior. We use social norms theory as elaborated in social psychology [ 17 ]. This theory conceptualizes social norms as beliefs of two types: 1) an individual’s beliefs about what others typically do in a given situation (i.e., descriptive norm); and 2) their beliefs about what others expect them to do in a given situation (i.e., injunctive norm) [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. For this study, we focus on developing a measure of injunctive norms—defined in this case as beliefs about what influential others (e.g., parents, siblings, peers, religious leaders, teachers) expect individuals to do in the case of GBV.

Even with the multiple challenges of humanitarian settings (e.g., separation of families, insecurity and limited resources), there is an opportunity to develop, implement, and evaluate innovations in GBV programming. In such settings, displacement and conflict have created situations where social rules about who can do what necessarily bend to accommodate new realities [ 16 ]. Women, for example, may be forced to assume new roles in the family and community, such as having decision-making power and control over household financial resources and assets and working outside the home to help support the family. These changing roles then lead to shifts in behavior and potentially power relations in the family and community that challenge traditional norms around male authority and women’s relegation to the domestic sphere. These circumstances can provide an opportunity to initiate GBV primary prevention efforts, such as those that engage community leaders and members in critical reflection on norms that legitimate gender inequality and what actions can be taken by the individual, family, and community to change norms that cause harm [ 15 , 16 ]. Acknowledging the potential of the humanitarian setting as an opportunity for primary prevention programming and recognizing the need to strengthen GBV response systems, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) built on their work to end female genital mutilation using social norms theory [ 19 ] to develop the Communities Care Program: Transforming Lives and Preventing Violence Program (Communities Care) [ 21 ]. The goal of Communities Care is to create safer communities for women and girls by challenging social norms that sustain GBV and catalyzing new norms that uphold women and girls’ equality, safety, and dignity [ 15 , 21 ]. The description of the Communities Care program is published elsewhere [ 15 , 16 , 21 ].

However, a significant limitation for evaluating the effectiveness of GBV prevention programs such as Communities Care is the lack of validated instruments to measure change in norms supporting GBV. Therefore, our goal was to create a brief, valid, and reliable measure to examine change over time in harmful social norms and personal beliefs that maintain and tolerate sexual violence and other forms of GBV in low resource and complex humanitarian settings.

While validated instruments exist to measure attitudes towards gender roles and some types of GBV [ 22 , 23 ], social norms are different from individual attitudes. For nearly two decades, the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), which are nationally representative surveys conducted in low and middle-income countries (LMIC), have provided information on attitudes about the acceptability of IPV or wife beating. Respondents are asked whether a man is justified in beating his wife in five different situations: a wife goes out without her husband’s permission; she neglects to keep the children well fed; she argues with her husband in public; she refuses to have sexual intercourse with her husband; and she does not prepare her husband’s meal on time. Response options for these questions are as follows: “agree,” “disagree,” “refuse to answer,” and “don’t know.” These questions are designed specifically to elicit personal beliefs (attitudes) about IPV; they have generally functioned well in that they capture various levels of endorsement of IPV both within and among settings, and respondents routinely vary their answers based on the transgression mentioned.

Investigators, however, have raised questions about whether the DHS questions reflect respondents’ own personal beliefs on the acceptability of beating or women’s perception of the social norm operative in their setting. Cognitive interviews with women in Bangladesh, for example, suggested that women’s interpretation of the attitude questions switched between personal and normative beliefs, although it is difficult to know whether this happens routinely in other settings, or whether it was a function of the especially low literacy and female mobility of rural Bangladesh [ 24 , 25 ].

Scientists have also warned that changing key features of a scenario (e.g., setting, perpetrator, infraction committed, perceived intentionality) can influence measured attitudes and perceived norms on the acceptability of GBV. For example, in Uganda, researchers randomly assigned participants to answer attitude and norm questions on wife beating using three separate wordings [ 26 ]. The attitude questions compared the traditional wording of the DHS (whether a man is justified in beating his wife for 5 different infractions) to more contextualized scenarios that depicted the wife’s transgression as either willful or beyond her control. To elicit norms related to wife beating, participants were asked about the extent to which they thought other people in their village (reference group) would think the behavior described was justified. Response options for the five questions followed a four-point Likert-type scale: “all or almost all, for example, at least 90% of people in your village,” “more than half but fewer than 90% of people in your village,” “fewer than half but more than 10% of people in your village,” and “very few or none, for example, less than 10% of people in your village.”

The findings demonstrated that when measuring both attitudes and social norms, adding contextual details about the intentionality of a wife’s transgression changed participants’ perception of the acceptability of IPV. In the vignettes, wives who intentionally violated norms about acceptable wifely behavior had a “large” effect [ 27 ] on increasing the number of items for which wife beating was viewed as acceptable. In contrast, the vignette that depicted the wife as unintentionally violating norms of behavior had a “small” effect in decreasing the number of items where IPV was considered acceptable. The study authors interpreted this difference as measurement error, arguing that question wordings without context may mis-represent attitudes and norms on violence. While context does matter, the specific details added in this study were likely critical to its findings. Qualitative studies have repeatedly shown that wife beating in LMIC is understood as “discipline” and its acceptability varies depending on the nature of the transgression (whether it is perceived as for “just cause”), who is doing the “correction,” and whether the beating stays within acceptable bounds of severity [ 24 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 30 ].

In this paper, we describe the formative research and psychometric testing of the Social Norms and Beliefs about Gender Based Violence (GBV) Scale . The Scale is designed to measure change over time in harmful social norms and personal beliefs associated with violence against women and girls among men and women community members in low resource and complex humanitarian settings. The development and validation of the scale was essential for use in measuring change in harmful social norms and beliefs among community members in districts and regions implementing the Communities Care program in two countries with ongoing humanitarian crises, Somalia and South Sudan. The development and testing of the scale was conducted in two phases: 1) formative phase of qualitative inquiry to identify social norms and personal beliefs that sustain and justify GBV perpetration against women and girls across the lifespan in low-resource and humanitarian contexts; and 2) testing phase using quantitative methods to conduct a psychometric evaluation of the new scale in targeted areas of Somalia and South Sudan.

Study settings

The formative and testing phases of the psychometric evaluation was conducted in two countries, Somalia and South Sudan. In Southern Central Somalia, we worked in four districts (Bondhere, Karaan, Wadajir, Yaqshid ) in Mogadishu and in South Sudan, we worked in two regions (Yei and Warrap). Somalia has experienced more than two decades of conflict as well as ongoing emergencies including drought, famine, and a large number of internally displaced people (IDPs). Yei is located in southwestern South Sudan and was the re-entry point for South Sudanese who fled to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Uganda during the Second Sudanese Civil War. Since many people stayed in Yei upon returning, there is conflict between those native to Yei and IDPs from other regions of South Sudan. Warrap is in the northern region of South Sudan and is a gateway between South Sudan and Sudan. Militia activity, cattle-raiding, and conflict over oil, along with the influx of people returning to South Sudan, has caused significant challenges for access to and use of limited resources. The districts and regions in each country were selected based on multiple factors. We focused efforts on districts and regions where GBV reporting systems existed and could be accessed to generate data on case reports and referrals. When engaging GBV survivors and other community members in research on sensitive issues it is essential to have partnerships with diverse service sectors (e.g., health, protection, legal, advocacy) for participants that disclose GBV and request referrals. The evaluation also required safe access to the sites and security while doing the study for both participants and local researchers, therefore this required establishing relationships and obtaining permission from national, regional, and district governmental authorities and ministries as well as traditional leaders in the communities.

Phase 1: Formative phase methods

For the formative phase, we worked with local partners to identify male and female key stakeholders (e.g., religious leaders, youth and women’s group leaders, advocates for GBV survivors, health providers, child protection staff, police officers, traditional leaders, elders, and teachers) to advance our understanding of and identify harmful and protective social norms associated with GBV within and across settings. The focus group guide was developed and translated to the local language in partnership with team members in each setting. Johns Hopkins provided in-depth training to local staff on facilitating focus groups, data collection, human subjects’ protections, working with distressed participants, and providing referrals to services as appropriate. The focus group guide focused on identification of social norms that protect women and girls from sexual violence and other forms of GBV, norms that are harmful (e.g., hide, sustain, or encourage), norms about disclosing and reporting sexual violence and other forms of GBV to authorities, and who are the people in the family or larger community that are influential in maintaining and changing social norms. For example, the team used scenarios created from aggregating GBV experiences in each setting to explore social norms about the situations and the survivor-perpetrator relationship. We varied the perpetrator and circumstances in each scenario from the perpetrator being a family member, a known person to the family but not part of the family, and an unknown person. For each scenario, focus group participants were asked about their beliefs and norms about how the family and community would respond to victims of the sexual assault or other forms of GBV, if the assault would be reported to authorities, and reasons for reporting or not reporting the assault.

Qualitative analysis

A qualitative descriptive approach was used to identify themes related to harmful and protective social norms within and across settings. The transcripts were read by three research team members to identify thematic codes. Themes with sub-themes were identified and defined by exemplars or quotes from the transcripts. The three researchers independently assigned codes and discrepancies in coding were discussed in weekly meetings. The codes and corresponding quotes were used to write items for the scale representing each of the identified themes. The themes, sub-themes, and items were then shared with the in-country teams in a joint Somalia/South Sudan meeting. The relevance of the themes and their interpretation for each context was discussed leading to a refinement of the items. Meeting participants from each country rated the importance of each item and offered suggestions on wording of the items to ensure they were capturing the relevant aspects of the different contexts and cultures.

Results of phase 1: Formative phase

A total of 42 focus groups (22 in Somalia and 20 in South Sudan) with a total of 215 participants (111 in Somalia and 104 in South Sudan) were conducted. The composition of the focus groups varied by stakeholders (e.g., religious leaders, service providers, teachers, police, youth, elders), age (under 30, 31–45, and 46+), marital status, and sex. Themes identified for social norms that are protective against GBV included parents teaching/guiding children, marriage, and respect for female members of the family. Themes identified as harmful social norms included men’s responsibility/right to correct female behavior and the social expectation that a woman will obey her husband and fulfill her gender prescribed duties to his satisfaction, protecting the family’s dignity by not reporting violence/assault to avoid stigma associated with being a victim, husband’s right to force his wife to have sex, lack of status for women, and forced marriage. Mothers, fathers, parents, community and religious leaders, and male relatives were seen as people that influenced behavior and protected women and girls from GBV. Men and women’s behavior also emerged as subthemes associated with harmful social norms, such as indecent dressing, being out in public alone, and drug/alcohol use. Stigma associated with being a GBV victim, blaming women and girls for the violence/assault, and the importance of family honor and respect were identified as norms that prevent victims and families from reporting sexual violence and other forms of GBV to authorities. Items for the new scale were written for each of the themes and sub-themes relevant to harmful social norms and after elimination of redundant items, 30 items remained and were presented to the in-country teams. After discussion about the focus group themes and the items with the in-country teams, a total of 18 items remained. The team then collaborated to develop introductory statements and response scales for each of two domains of the scale, personal beliefs and injunctive social norms. The final scale to be tested in the evaluation phase had two sets of the 18 items, one for each domain.

Methods for phase 2: Psychometric testing

At each of the three sites in the two countries detailed above, trained local research assistants (RAs) recruited and consented 200 community members (15 years and older) to complete the Social Norms and Beliefs about Gender Based Violence Scale. The sampling frame was stratified by age group (15–18, 19–24, 25–45, 46+ years) and sex with a target of 25 people per age group/sex combination. As suggested by the in-country teams, male RAs recruited and interviewed male community members and female RAs recruited and interviewed female community members. Each RA recruited participants across age groups. The RA started from a central point determined by the research coordinator each morning. The RA would contact every 3rd house/dwelling counting on both sides of the street/pathway. If nobody was home, the person was not willing to participate, or the person did not match the sampling target for sex/age, the RA went to the next house/dwelling. Once a RA identified and consented an eligible participant in the household and completed the scale, the RA started the process to identify the next eligible participant by going to the next 3rd house/dwelling on the street/pathway. Only one eligible household member completed the scale.

Field procedures

RAs received detailed training on protocols for maintaining participant confidentiality and safety as well as protocols designed to ensure safety and security for the team members. In the field, when a RA identified an adult at a house/dwelling, he/she introduced the study. If that person met the eligibility criteria and agreed to participate, the RA worked with the participant to find a private and comfortable place to provide informed consent and administer the scale. If that person did not meet eligibility, he/she was asked if there was someone living in the household that did meet the eligibility. The RA provided each potential participant with informed consent information using the script provided on the study tablet and approved by the in-country team and the Johns Hopkins Medical Institution Institutional Review Board (IRB). If the eligible participant provided verbal consent the RA continued and administered the scale with brief demographic questions, including marital status, employment, and children in the household. The responses were entered by the RA directly on the tablet. Once finished, the RA thanked the participant for their time and answered any questions prior to moving on.

The 18 items generated from the formative phase were asked in two sets to capture the two domains, personal beliefs and injunctive norms. The injunctive social norms items started with “How many of the people whose opinion matters most to you….” with the response scale of: 1 – None of them, 2 – A few of them, 3 – About half of them, 4 – Most of them, and 5 – All of them. The personal beliefs items started with “We would like to know if you think any of the following statements are wrong and should be changed in your community. We also would like to understand how ready or willing you are to take action by speaking out on the issues you think are wrong” and used the response scale: 1 – Agree with this statement, 2 – I am not sure if I agree or disagree with this statement, 3 – I disagree with the statement but am not ready to tell others, and 4 – I disagree with the statement and I am telling others that this is wrong. The scale was translated into Somali and the translation was reviewed by the Somalia team and revised before it was programmed into the study tablet. In South Sudan, the scale was administered in the Kakwa language in Yei and Dinka language in Warrap. As these are not commonly written languages in South Sudan, the team preferred using the English version of the scale programmed on the tablet and translated into the local language at time of administration. The South Sudan team training included discussions and decisions on correct translation of items in the two languages and then the team practiced administering with volunteers not participating in the study to ensure consistency in real-time translation across RAs and sites.

Psychometric analyses

For each of the two domains of the scale, we examined construct validity with factor analysis using the common factor model with oblique rotation. Factor loadings of .40 or above were considered as loading on a given factor [ 31 ]. Items that did not load on any factor were considered for revision or elimination from the scale. Reliability was estimated with Cronbach’s alpha for each factor subscale. Known groups validity was examined by testing two a priori hypotheses: H 1 : The sites (Somalia, Yei, South Sudan, and Warrup, South Sudan) differ on social norms and personal beliefs due to differences in the extent of GBV programming within the districts of Mogadishu and regions of South Sudan; and H 2 : Men and women participants will differ on social norms and personal beliefs related to GBV. The first hypothesis was tested with analysis of variance and the second with t-tests.

Results of psychometric testing

The team administered the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale to 602 community members across Mogadishu, Somalia and Yei and Warrup, South Sudan. The sampling frame was successfully implemented by the research team with 50.0% of participants across the settings being female and 50.0% male with an equal distribution across age groups except in Yei, South Sudan. The team in Yei reported having difficulty finding community members in the region over 60 years of age. The lack of older community members could be related to deaths in the Second Civil War from 1983 to 2005. Over half (58.6%) of the participants were married and had children in the home (67.4%). One third (34%) reported working outside the home, 10.1% were looking for work, 21.4% were students, 29.4% were housewives, and 4.7% were too old to work. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the participants by country and site.

Factor analysis

The factor analysis for the items in the injunctive norms domain of the scale was based on responses from participants that completed all items ( N = 587, 97.5%). There were 3 of the 18 items on the injunctive social norms scales that did not load on any factor and were thus removed from the scale. The first item “expect daughters to be married before 15 years of age” likely did not correlate with the other items on the scale because early marriage is seen as a different concept than sexual violence. The second item “think that if an unmarried woman/girl is raped by a man, she should marry him rather than not being married at all” captures two different concepts—marrying the man who raped her and that being better than not being married at all. This complexity likely made the question difficult to answer. The third item “expect a woman not to report her husband for forcing her to have sexual intercourse” did not reflect a consistent social norm. Discussions with the in-country teams revealed that there was considerable debate on this item even among people who agreed on other items. Based on the eigenvalues (first 5 eigenvalues were 4.27, 1.82, 1.23, 0.94, 0.81), the remaining 15 items formed three factors (Table 2 presents the factor loadings for each item on each of the three factors) with each item loading above 0.40 on only one factor. The following titles were given to represent the three factors, later describes as subscales: “Response to Sexual Violence” has 5 items, “Protecting Family Honor” has 6 items, and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” has 4 items. The “Response to Sexual Violence” and “Husbands’ Right to Use Violence” subscales had the highest inter-factor correlation (0.46) followed by “Response to Sexual Violence” and “Protecting Family Honor” (0.34), then “Protecting Family Honor” and “Husbands’ Right to Use Violence” (0.30). Importantly, these 3 factors were consistent with and reflected the themes identified from the qualitative analyses of the focus groups in Phase 1. A very similar factor structure was found for the personal beliefs domain ( N = 588, 97.7%). Eigenvalues (first 5 eigenvalues were 4.46, 1.76, 1.46, 0.90, 0.88) suggested 3 factors as illustrated in Table 3 . All items loaded at 0.45 or greater on only one of the three factors. One item, “a woman/girl would be stigmatized if she were to report rape” loaded on the “Response to Sexual Violence” in the personal beliefs domain whereas the corresponding item, “women/girls fear stigma if they were to report sexual violence”, loaded on the “Protecting Family Honor” subscale for the social norms domain. The inter-factor correlations on the personal beliefs domain were also very similar to the injunctive social norms domain scale: “Response to Sexual Violence” and “Husbands’ Right to Use Violence” had the highest correlation (0.43) followed by “Response to Sexual Violence” and “Protecting Family Honor” (0.32), then “Protecting Family Honor” and “Husbands’ Right to Use Violence” (0.26).

Reliability

Cronbach alpha reliabilities, a measure of internal consistency of the scale, were in an acceptable range for all factors/subscales within each domain. Cronbach alphas ranged from 0.69 to 0.75 for the injunctive norms domain and 0.71 to 0.77 for the personal beliefs domain (the last row of Tables 2 and 3 present the Cronbach alphas for each scale).

Descriptive statistics

Scores for each of the factors (subscales) were computed by taking the average of the items within the subscales. The injunctive social norms domain subscales scores range from 1 to 5 with higher scores reflecting more negative responses to sexual violence and GBV, stronger support for social norms that prioritize protecting family honor by not reporting sexual violence or other forms of GBV, and stronger support for norms endorsing a husband’s right to use violence. Personal beliefs subscales can range from 1 to 4 with higher scores reflecting a more positive response to survivors of sexual violence, that protecting family honor and not reporting sexual violence is wrong, and that a husband should not have the right to use violence against his wife. The means, standard deviations, minimum, and maximum observed score for each of the subscales in each domain are presented in Table 4 . In general, the mean for the injunctive social norms subscales reflect participants’ views that “few to about half” of the people who are important/influential to them endorse harmful social norms about GBV with “Protecting Family Honor” being the strongest norm (means range from 2.00 to 2.77). The mean for the personal beliefs subscales reflects that participant beliefs range between “not being sure if they disagree” with the norms to “disagreeing but not being ready to speak out against them.” Specifically, participants’ beliefs ranged between not being sure if they disagree to disagreeing but not ready to speak out against protecting family honor (mean = 2.61) and husband’s right to use violence (mean = 2.90). Participants indicated that they were between disagreeing but not being ready to tell others to telling others that negative responses to sexual violence survivors are wrong (mean = 3.29). Cross domain correlations were − .318 (p < .001) for “Response to Sexual Violence”, −.512 (p < .001) for “Protecting Family Honor”, and − .427 (p < .001) for “Husband’s Right to Use Violence.”

Known groups validity

Analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc tests revealed that the three sites differed significantly on all subscales for the injunctive social norms domain (i.e., “Response to Sexual Violence,” p < .001; “Protecting Family Honor,” p = .039; “Husband’s Right to Use Violence,” p < .001). Women and men participants in Yei, South Sudan, where there are few GBV programs and services, reported social norms that are significantly more accepting of sexual violence and other forms of GBV than Warrap, South Sudan and Mogadishu, Somalia. In terms of personal beliefs, women and men in Yei were also significantly less likely to speak out against harmful responses to sexual violence and other GBV (p < .001). In Mogadishu, Somalia, men and women were significantly less likely to speak out against “Protecting Family Honor” (p < .001) and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” (p < .001) than the sites in South Sudan. Table 5 summarizes the t-test results examining differences in the subscales for both domains between men and women. Women participants had significantly higher scores on all of the subscales for the injunctive social norms, indicating women were more likely to endorse harmful norms related to “Response to Sexual Violence”, “Protecting Family Honor”, and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” than men. Men and women did not differ on personal beliefs about “Response to Sexual Violence”, however, men reported that they are more ready to speak out against harmful social norms of “Protecting Family Honor” and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” than women.

The psychometric properties of the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale (final scale is presented in Additional file 1 ) are strong. Each of the three subscales, “Response to Sexual Violence,” “Protecting Family Honor,” and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” within the two domains of the scale illustrate good factor structure, acceptable internal consistency, reliability, and are supported by the significance of the hypothesized group differences. These three factors represent social norms that are known from previous research to maintain the high rates of GBV in many global settings [ 28 ]. The “Response to Sexual Violence” subscale captures the individual, family, and community response of blaming the victim for GBV. Most often a woman or girl is blamed for the sexual assault or other form of GBV and the family and larger community can respond with rejection and judgement of her behavior, which can result in the family not supporting or abandoning the victim. It reflects the acceptance of sexual violence and other forms of GBV as expected or even normal and that women and girls need to limit their movement and actions to prevent men from assaulting them, as men are not able to control their behavior if they are “tempted” by women. High scores on the injunctive norms domain of this subscale represent that the respondents believe that their influential others expect people to endorse victim blaming responses to sexual violence and other forms of GBV. The “Protecting Family Honor” subscale identifies the stigma associated with being a member of a family/clan where a women/girl experiences GBV and the importance placed on addressing the violence within the family/clan rather than reporting it to authorities. The priority is to protect the family and victim’s reputations rather than the safety and well-being of the woman or girl. High scores on the injunctive domain of this subscale represent that the respondent believes their influential other expects people to prioritize protecting family honor over safety and well-being of victims. The “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” subscale reflects social norms that support a husband’s use of violence to discipline his wife and to have sex with her even when she does not want to. It also reflects a norm that associates a man’s use of violence against his wife with illustrating his love for her. High scores on the injunctive norms domain for this subscale indicates that the respondents believe their influential others expect people to endorse a husband’s right to use violence against his wife. High scores on the personal beliefs domains for each of the subscales reflect a greater willingness to speak out against social norms that endorse GBV.

Validity of the injunctive norms subscales was supported by significant relationships with other variables (i.e., site and sex) as hypothesized during the development of the scale. The three sites were significantly different on the injunctive norms domain of the scale. Although all three sites experienced a high degree of conflict, the amount of humanitarian services to support GBV survivors and programming to raise awareness and change harmful social norms towards GBV varied. Mogadishu districts participating in the study had relatively active programming, with Warrap and Yei reporting few international and local NGOs with capacity to provide diverse GBV services and programs. Yei, South Sudan was found to have significantly stronger norms that endorse negative “Response to Sexual Violence” and other forms of GBV than other sites. The beliefs of participants from Yei also indicated less support for changing harmful social norms about GBV than other sites in the study. Participants in the four districts of Mogadishu scored the lowest on the personal beliefs subscales of “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” and “Protecting Family Honor.” This finding indicates that participants were less willing to speak out against social norms that support husbands’ rights to use violence against their wives or norms that support not reporting sexual violence to protect family honor than the South Sudan sites. Important to interpreting the findings are the differences in context, culture, and religion across the sites which inform social norms and personal beliefs.

Generalizability is one of the indicators of trustworthiness of the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV scale – the ability to interpret and apply the scale in a broader context to make it relevant and meaningful to GBV prevention programs being implemented and evaluated in diverse low-resource and humanitarian settings. Importantly, the 36-item two domain scaled applied with community members by local teams in diverse districts and regions within Somalia and South Sudan resulted in a valid and reliable 30-item scale to measure personal beliefs and injunctive social norms. The psychometric phase included randomly selected women and men across multiple age groups (15 years and older), living in both urban and rural communities, and included community members living in settlements and camps for displaced persons. Thus, the scale has the potential to be used in not only humanitarian settings, but also GBV prevention programs in other low-resource and fragile settings.

Although this psychometric evaluation has several strengths, including a mixed methods design to develop the scale and a large sample size to test the scale across diverse sites, it has limitations. The study does not include a separate validation sample to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis. Further, we did not test the relationship between the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale and community members’ reports on experience, perpetration, or witnessing of GBV in the participating communities. The research team decided in collaboration with local partners not to ask participants in the evaluation phase about personal experiences with GBV for either the scale development or testing. The local colleagues felt community members would be more comfortable and likely to participate in the scale development and testing if they were not asked about their own experiences and thus also increasing generalizability.

The study presents a mixed methods approach to developing a brief scale with strong psychometric properties to measure change in harmful social norms associated with GBV. The Social Norms and Beliefs About GBV Scale is a 30-item scale with three subscales, “Response to Sexual Violence,” “Protecting Family Honor,” and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” in each of the two domains, personal beliefs and injunctive social norms. The scale to our knowledge is one of the first to demonstrate good factor structure, acceptable internal consistency, and reliability, and be supported by the significance of the hypothesized group differences by setting and sex. We encourage and recommend that researchers apply the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale in different humanitarian and global LMIC settings and collect parallel data on a range of GBV outcomes. This will allow us to further validate the scale by triangulating its findings with GBV experiences and perpetration and assess its generalizability across diverse settings.

Abbreviations

Demographic and Health Surveys

Democratic Republic of Congo

- Gender-based violence

Inter-Agency Standing Committee

Internally displaced persons

Intimate partner violence

Institutional Review Board

Low and middle-income countries

Non-partner violence

Research assistant

United Nations Children’s Fund

Decker MR, Latimore AD, Yasutake S, Haviland M, Ahmed S, Blum RW, et al. Gender-based violence against adolescent and young adult women in low- and middle-income countries. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):188–96.

Article Google Scholar

Devries KM, Mak JY, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, et al. Global health. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340(6140):1527–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Watts C, Zimmerman C. Violence against women: global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1232–7.

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH, WHOM-cSoWs H, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–9.

Vu A, Adam A, Wirtz A, Pham K, Rubenstein L, Glass N, et al. The prevalence of sexual violence among female refugees in complex humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Curr. 2014;6.

Wirtz AL, Pham K, Glass N, Loochkartt S, Kidane T, Cuspoca D, et al. Gender-based violence in conflict and displacement: qualitative findings from displaced women in Colombia. Confl Health. 2014;8:10.

Sloand E, Killion C, Gary FA, Dennis B, Glass N, Hassan M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to engaging communities in gender-based violence prevention following a natural disaster. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(4):1377–90.

IASC. Guidelines for Integrating Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action. Reducing risk. In: Promoting resilience and aiding recovery Geneva: inter-agency standing committee; 2015.

Google Scholar

Vu A, Adam A, Wirtz AL, Pham K, Rubenstein LS, Glass N, et al. The prevalence of sexual violence among female refugees in complex humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Currents: Disasters. 2014.

McCleary-Sills J, Namy S, Nyoni J, Rweyemamu D, Salvatory A, Steven E. Stigma, shame and women's limited agency in help-seeking for intimate partner violence. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(1–2):224–35.

Stark L, Warner A, Lehmann H, Boothby N, Ager A. Measuring the incidence and reporting of violence against women and girls in Liberia using the 'neighborhood method. Confl Health. 2013;7(1):20.

Wirtz AL, Glass N, Pham K, Aberra A, Rubenstein LS, Singh S, et al. Development of a screening tool to identify female survivors of gender-based violence in a humanitarian setting: qualitative evidence from research among refugees in Ethiopia. Confl Health. 2013;7(1):13.

Wirtz AL, Glass N, Pham K, Perrin N, Rubenstein LS, Singh S, et al. Comprehensive development and testing of the ASIST-GBV, a screening tool for responding to gender-based violence among women in humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2016;10:7.

Heise L. What Works to Prevent Partner Violence? An Evidence Overview: Working Paper. London: STRIVE Research Consortium,London School of Hygiene and Tropical. Medicine. 2011.

Read-Hamilton S, Marsh M. The communities care programme: changing social norms to end violence against women and girls in conflict-affected communities. Gend Dev. 2016;24(2):261–76.

Glass N, Perrin N, Clough A, Desgroppes A, Kaburu FN, Melton J, et al. Evaluating the communities care program: best practice for rigorous research to evaluate gender based violence prevention and response programs in humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2018;12:5.

Berkowitz AD. An Overview of the Social Norms Approach. Changing the Culture of College Drinking: A Socially Situated Health Communication Campaign: Hampton Press; 2005. p. 303.

Bicchieri C. The grammar of society : the nature and dynamics of social norms. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Mackie G, Moneti F, Shakya H, Denny E. What are social norms? How are they measured? New York: UNICEF/UCSD Center on Global Justice; 2015 July 27.

Alexander-Scott M. Emily bell,, Holden J. DFID Guidence note: shifting social norms to tackle violence against women and girls. London: DFID Violence Against Women Helpdesk; 2016.

UNICEF. Communities care: transforming lives and preventing violence toolkit. New York: UNICEF; 2014.

Barker G, Nascimento M, Segundo M, Pulerwitz J. How do we know if men have changed? Promoting and measuring attitude change with young men: lessons from program H in Latin America. In: Ruxton S, editor. Gender equality and men: learning from practice. Oxfam, UK: Oxford; 2004. p. 147–61.

Chapter Google Scholar

Leon F, Foreit J. Developing women’s empowerment scales and predicting contraceptive use: A study of 12 countries’ demographic and health surveys (DHS) data. Draft manuscript ed2009.

Schuler SR, Islam F. Women's acceptance of intimate partner violence within marriage in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plan. 2008;39(1):49–58.

Schuler SR, Lenzi R, Yount KM. Justification of intimate partner violence in rural Bangladesh: what survey questions fail to capture. Stud Fam Plan. 2011;42(1):21–8.

Tsai AC, Kakuhikire B, Perkins JM, Vorechovska D, McDonough AQ, Ogburn EL, et al. Measuring personal beliefs and perceived norms about intimate partner violence: population-based survey experiment in rural Uganda. PLoS Med. 2017;14(5).

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

World Health Organization. Changing cultural and social norms that support violence. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009.

Adjei SB. “Correcting an erring wife is Normal”: moral discourses of spousal violence in Ghana. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;33(12):1871–92.

Tchokossa AM, Golfa T, Salau OR, Ogunfowokan AA. Perceptions and experiences of intimate partner violence among women in Ile-Ife Osun state Nigeria. Int J Caring Sci. 2018:267–78.

Costello AB, Osborne J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the Most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2005;10(7):1–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge our committed and talented implementing partners in South Sudan, two national NGOs, Voice for Change in Central Equatoria State and The Organization for Children Harmony in Warrup State. In Somalia, the Italian NGO, Comitato Internazionale per LoSviluppo dei Popoli (CISP) Mogadishu and other regions of the country.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) provided the funding for the Communities Care program.

Availability of data and materials

The Communities Care program toolkit is available through United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Requests for research data and materials can be obtained by contacting UNICEF.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, 525 North Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA

Nancy Perrin, Amber Clough, Rachael Turner, Lori Heise & Nancy Glass

UNICEF, New York, NY, USA

Mendy Marsh

Comitato Internazionale per lo Sviluppo dei Popoli (CISP) Somalia, Nairobi, Kenya

Amelie Desgroppes, Ali Abdi & Francesco Kaburu

Voice For Change, Yei, South Sudan

Clement Yope Phanuel

Norwegian Church Aid, Oslo, Norway

Silje Heitmann

UNICEF, Geneva, Switzerland

Masumi Yamashina

UNICEF Somalia, Mogadishu, Somalia

Brendan Ross

Consultant, Gender based violence in Emergencies, Sydney, Australia

Sophie Read-Hamilton

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

NP, NG, MM, AC, SRH, SH, FK, AD, MY designed the study. MM, SRH, NP, RT, LH, NG and AC identified the theoretical framework for the formative and psychometric phases of the study. NG, NP, and LH conducted the psychometric analysis. MY, CYP, AA, AC, NP and NG implemented and interpretation the study findings in South Sudan and SH, BR, AD, AA, FK, AC, NG and NP implemented and interpretation of the study findings in Somalia. NP, NG, RT, AC and LH finalized the manuscript.