Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Tensions of Modern Britain in Jez Butterworth’s “Jerusalem”

By Rebecca Mead

“I’ve never seen the point of other countries,” Davey Dean, a character in Jez Butterworth’s “Jerusalem,” currently in revival at the Apollo Theatre in London’s West End, announces near the beginning of the play. “I leave Wiltshire, my ears pop. Seriously. I’m on my bike, pedalling along, see a sign says ‘Welcome to Berkshire,’ I turn straight round. . . . Suddenly it’s Reading, then London, then before you know where you are you’re in France, and then there’s just countries popping up all over.” When I revisited “Jerusalem” one night earlier this month, the audience laughed at Dean’s complacent satisfaction with his parochial existence, as intended. Still, I couldn’t help my thoughts turning to recent reports that British travellers at Spanish airports had experienced lengthy waits to have their passports stamped by border control, while citizens of the European Union sped through the electronic gates. “ Rage as Brits stuck in airport queue for 3h—EU travellers ‘given looks that could kill,’ ” read a headline in the right-wing Daily Express , which, in 2016, was among those media outlets championing the pro- Brexit vote that eliminated the free movement not just of foreigners but of British people themselves, in and out of continental Europe. Fine if you’re Davey Dean; not so great if you’re among the two-thirds of Britons—and surely a higher proportion of the Apollo Theatre’s audience—who, before the pandemic , took at least one annual holiday in a country other than your own green and pleasant land.

When Butterworth’s “Jerusalem” was first staged, at the Royal Court Theatre, in 2009, it was immediately heralded as a classic: a ribald comic vision of debased, but still vital, rural English life, a decade after the turn of the millennium. “Jerusalem” was set in the fictional village of Flintock, in the southern county of Wiltshire, in the course of a single day in spring—the occasion of the annual fair. At its center was Johnny (Rooster) Byron, a drug-dealing, caravan-dwelling, teen-ager-enchanting, tall-tale-telling daredevil in a final standoff with the local council, incarnated with spectacular force by Mark Rylance, who returns in the current revival. The vision of contemporary England depicted in “Jerusalem” was utterly recognizable, with glimmering folkloric remnants—the woodlands traversed by ley lines that reputedly link one ancient spiritual site with another, and legends of giants who tramp across the downs—glimpsed between the barbarisms of modernity, where an excrescence of shoddily built new housing erases acres of countryside.

Even an institution as time-honored as the local pub is at the mercy of bland corporate diktat: “Public bar, saloon bar, pool table, ‘Millionaire’ machine, shit burgers, crap kiddies’ option, fiddly bloody sachets, broken bloody towel dispensers, fucking stupid T-shirts” is how a publican describes his own establishment. The language of the play moves between the vernacular and the elevated, informed by the repartee of TV sitcoms as well as by the poetry of William Blake. “This wood is called Rooster’s Wood,” Byron announces to one of those friends and neighbors who is urging him to surrender his illegal encampment before the bailiffs force him out. “I’ve been here since before all you bent busybody bastards were born,” he goes on. “I’m heavy stone, me. You try and pick me up, I’ll break your spine.” The pastoral of Shakespeare lies deep beneath the play’s surface, and below that are even older cultural strains. When the play’s climax shows a bloodied Rooster Byron attempting to summon the giants of England to his aid, Butterworth has sure-handedly connected contemporary to ancient England.

At the time of “Jerusalem” ’s first staging, Butterworth insisted that he had harbored no ambition to write a “state of the nation” play—that any political relevance it offered was purely accidental. That’s easy to believe: the play has the quality of organic inspiration, its mythic resonances inspired rather than constructed. In an interview in 2017, Butterworth spoke of having received a letter from an audience member that revealed to him a layer of meaning to the play’s final scene, which he hadn’t had in mind at all. The woman wrote that “the last time that she was naked, covered in blood with a drum beating in her ears waiting to meet giants was when she was born.” By the end of the play, Rooster Byron himself is on a threshold between one life and another.

That’s not, however, how “Jerusalem” was often received. “An excellent, unexpected state-of-the-nation piece that takes a necessary CT scan of the English character” is how Andrew Billen described the play in the left-leaning New Statesman , calling the drama “a new battle in the eternal English civil war between Roundheads and Cavaliers.” The Roundheads in this case are the clipboard-toting officials from the local council, with their smug relish in finally having the power to oust Byron. The Cavaliers are Byron and his gaggle of teen-age and post-teen-age followers who gather in the glade around his mobile home to procure and consume drugs, to drink cider and, sometimes, tea—this is England, after all—and to defy the rules imposed by schools, parents, society at large. In one funny but also genuinely alarming scene, Byron rouses his crew to storm Flintock village and “whip into a whirlwind a rough-head army of unwashed, unstable, unhinged, friendless, penniless, baffled berserkers.” Fortunately, pitchforks seem to be in short supply around Byron’s encampment, as do any other tools of actual labor.

Critics on the right, too, saw “Jerusalem” through a political lens. Quentin Letts, then the theatre critic for the right-wing Daily Mail , described the play at the Royal Court as “an invigorating, yelping, defiant portrait of 21st century shires England,” and “a furious blast at the urban homogenisers who want us all to live in a concreted realm under streetlights and closed circuit cameras.” Letts added, “All those Islingtonians who go to Glastonbury every year should listen!” Islington, a once bohemian, later affluent borough of North London, served for Letts, as it still does for many commentators, as a synonym for educated, left-leaning cosmopolitanism—a byword for the kind of people who, seven years after “Jerusalem” was first staged, were blindsided by the narrow but definitive victory of the Leave vote in the Brexit referendum.

In 2009, Britain was coming to the end of what might be called the long reign of Islington: thirteen years of governance by New Labour, the Party having swept into power in 1997 headed by Tony Blair , who moved to 10 Downing Street from Richmond Crescent, a tree-lined street in the heart of the borough. Having thrice led the party to victory on a platform more centrist than those of Labour governments past, Blair stepped aside as leader in 2007, his accomplishments in government and his personal reputation severely battered by his decision to send British forces to join American ones in the war in Iraq —a choice that was deeply unpopular within the ranks of his own party and across the nation. His successor as Labour leader, Gordon Brown, lasted only three years in the role, until the year after “Jerusalem” débuted, when a general election brought to power the Conservative Party, headed by David Cameron, in a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats.

Five years later, Cameron would call a referendum on Britain’s membership of the E.U., and though never himself a resident of Islington—when in town, he lived in swankier West London—Cameron shared the confident metropolitan expectation that his Remain forces would prevail. Two years after the vote, in 2018, a revival of “Jerusalem” was staged in the provincial Watermill Theatre in Berkshire, with the character actor Jasper Britton taking on the lead role. At that time, it was reviewed in the light of the nation’s recent convulsions, the Guardian critic saying that the play revealed “a yearning for a bygone Britain that never existed—a once magnificent ‘Holy Land’ of fairies, Arthurian legends and Stonehenge giants.” From this vantage point, Byron and his renegade hangers-on were speaking on behalf of England’s left-behind majority and clinging defiantly to a tarnished nostalgia.

When it was first announced that “Jerusalem” would be revived with Rylance returning to the lead role thirteen years after he created it, some observers wondered how the play might stand up, given the changed state of the nation. Were its female characters too thinly sketched in the post-#MeToo era? Was its definition of Englishness too narrow, given the ongoing interrogation of imperial conquest? (And was it chiefly a commercial ploy to replenish theatrical coffers ravaged by COVID by means of top-dollar ticket prices?) Such questions are resoundingly rebutted by the revival, which, like all successful works of art, speaks not only to the moment in which it was created but also to that in which it is seen and absorbed.

In 2022, Britain has entered its twelfth year of Conservative governance, almost as long a hold on power as that of the Labour government when Butterworth wrote his play. As in 2009, if for different reasons, there is a restive mood among the public, a sense that the nation’s leaders have become decadent, complacent, out of touch. This week, two by-elections are being held to replace disgraced Conservative Members of Parliament; in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, where the former M.P. Imran Ahmad Khan was recently sentenced to eighteen months in prison for sexually assaulting a fifteen-year-old boy in 2015, and in the rural seat of Tiverton and Honiton, where the former M.P. Neil Parish stepped down after it was revealed that he had watched porn on his phone in the chamber of the House of Commons. The Flintock of “Jerusalem” is a tattered, soiled place—its woodland littered with empties and its pathways tramped by nihilistic roisterers. Increasingly, it feels like the current government is, too. Rooster Byron is one of the great antiheroes of the stage, but it was hard, when watching his defiance of all efforts to dislodge him, not to think again of another item from last week’s news: the confidence vote held among Conservative Members of Parliament on their leader. More than forty per cent of them voted against Prime Minister Boris Johnson —another larger-than-life character whose stories cannot be trusted and who, as he squats in Downing Street, seems no more likely than Rooster Byron to move on without bringing the place down with him when, eventually, he goes. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

Searching for the cause of a catastrophic plane crash .

The man who spent forty-two years at the Beverly Hills Hotel pool .

Gloria Steinem’s life on the feminist frontier .

Where the Amish go on vacation .

How Colonel Sanders built his Kentucky-fried fortune .

What does procrastination tell us about ourselves ?

Fiction by Patricia Highsmith: “The Trouble with Mrs. Blynn, the Trouble with the World”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Sam Knight

By Adam Gopnik

By Vinson Cunningham

By Gideon Lewis-Kraus

by Jez Butterworth

Jerusalem analysis.

These notes were contributed by members of the GradeSaver community. We are thankful for their contributions and encourage you to make your own.

Written by people who wish to remain anonymous

The play begins with Fawcett and Parsons coming to Johnny's caravan in order to serve a notice of eviction to him. We see that Johnny 'Rooster' is clearly not a normal man as he enjoys a breakfast of milk, vodka, speed, and an egg. Butterworth creates a portrait of what society deems acceptable. Byron allows kids to drink and do drugs with him, he sleeps with housewives and provides drugs to anyone who needs them. On top of that, though, is a society that wants to evict him out of the forest in which he has lived for 20 years in order to build a community of homes. It becomes an uncertain tale of right and wrong as everyone is doing the wrong things, but when a community of people gather together they are capable of taking what they want.

What they are taking is far more than a plot of land, the symbolism in their action to evict Rooster and build a community of homes has to do with the destruction of nature. How there is great beauty and mystery that lies within the forest, but people don't care for that, they want progress; more more more and they are going to get it.

In addition to this, Butterworth asks the question as to where our children are safest: at home or out in the forest with Byron? The interpretations of this can be vast, but the playwright is calling into question our values as a society and our ability to look truthfully at what is happening around us. The character of Phaedra represents how kids are not protected in their own homes anymore, and thus turn to a place that seems safe to them, even if by all standards it isn't.

The through-line of magic and power in the play relates to the lack of understanding as to where we have come from. We are moving forward, bulldozing forest after forest when we have no idea what the history of the land is, and the value that it holds.

Update this section!

You can help us out by revising, improving and updating this section.

After you claim a section you’ll have 24 hours to send in a draft. An editor will review the submission and either publish your submission or provide feedback.

Jerusalem Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Jerusalem is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Study Guide for Jerusalem

Jerusalem study guide contains a biography of Jez Butterworth, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Jerusalem

- Jerusalem Summary

- Character List

Essays for Jerusalem

Jerusalem essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Jerusalem by Jez Butterworth.

- Antiheroes and Their Identities: Comparing Jerusalem and The Wasp Factory.

- A Comparison of Jez Butterworth and Christopher Isherwood's Resistance to Social Norms in 'Jerusalem' and 'A Single Man'

- Butterworth's Use of Dramatic Method in Scene 1:

- An Investigation into the Power Dynamic between Troy and Johnny

- Jerusalem and Albion: An Ecological Perspective on Contemporary British Theatre

Wikipedia Entries for Jerusalem

- Introduction

- Inspiration for the play

- Productions

- Our Writers

- Watch & Listen

- UnHerd Club

- Subscription Sale

‘Jerusalem’ is the play we need right now Jez Butterworth's masterpiece is a rare thing: a revival that's in tune with our troubled times

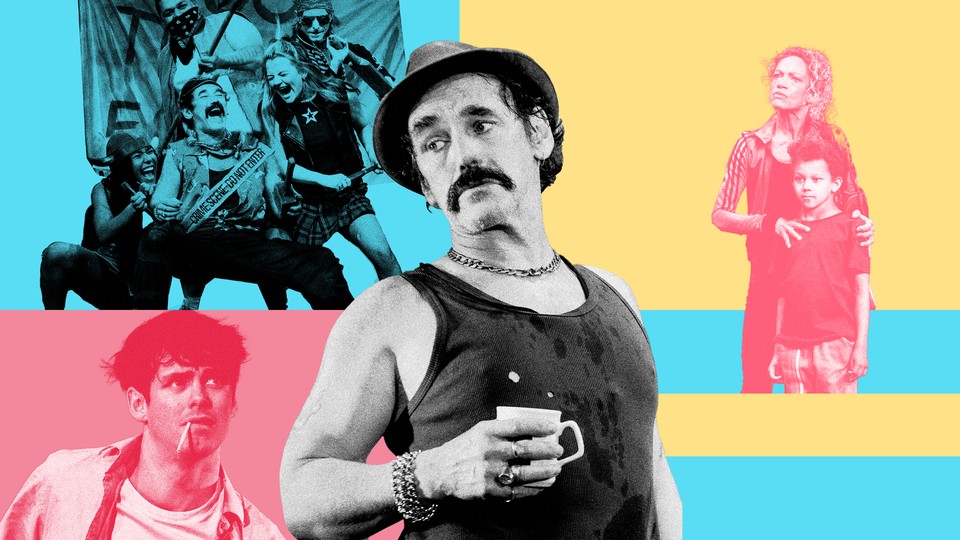

Charlotte Mills as Tanya, Mark Rylance as Johnny 'Rooster' Byron and Jessica Barden as Pea in Jez Butterworth's 'Jerusalem', directed by Ian Rickson. (Photo by Robbie Jack/Corbis via Getty Images)

Barney Norris

April 29, 2020 5 mins.

One of the most beautiful things about theatre, and perhaps the most poignant, is the way it disappears. There’s an air of mourning about the best work as a result of this: almost as soon as you’ve seen it, it will go. Great performances seem to be imbued by the knowledge of this fleeting quality, made to burn brighter by their mayfly nature.

Within a few years of even the most successful show in the world opening, only traces of that show will be left behind, and the best record of what made it extraordinary will only exist in people’s memories. A playtext might be published, leaving a record of what was said, and the production might transfer and run in the West End for a while, but it will always close eventually. Revivals will happen, new versions for new times, and the creatives who were part of the first productions will go on and do other things, but they’re rarely, if ever, seen together again.

Imagine a world where bands only ever played their latest albums, and all previous albums could only be heard on bootleg live recordings, no one could ever hear the real thing again. That’s the theatre.

Bearing this in mind, you can understand the elation of many when it was announced on St George’s Day that Ian Rickson was going to direct Mark Rylance in Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem again next year , over a decade after they first told that story together. For a great number of theatregoers, Jerusalem ranks as the most extraordinary night they’ve spent in a theatre, Rylance’s towering, Eric Cantona-like portrayal of the lead character, Johnny ‘Rooster’ Byron, the most compelling thing they’ve witnessed.

'This Country' is a modern TV miracle

By Barney Norris

These kinds of shows rarely come round again. The key creatives are too busy, with too many projects and calls on their time, and they’ve done the thing, anyway — they’re happy to move on. But Rylance and Rickson are going to revisit their greatest work, while still at the peak of their powers, after a decade when everything and nothing seems to have changed in England. It’s a truly amazing opportunity for audiences to experience something many of us thought was gone.

Jerusalem tells the story of a man about to be evicted from his caravan in a Wiltshire wood by the Kennet and Avon council. It’s about people living on the wild edges of society, and people who’ve fallen into the meat grinder of precarious rural life. It’s about the lure of the lawless, the country’s rebel spirit. It’s about England, in an ambitious way that few writers attempt and even fewer avoid embarrassing themselves in the course of attempting. But Butterworth did it triumphantly. Very few theatremakers living now will ever produce anything as good as this show was in its first production.

There’s a bit of the Tyson Furys about the play. Fury, widely thought to be the world’s best heavyweight boxer, is principally interesting to me because, like the folk singer John Martyn , he shows us that talent, like love, doesn’t always behave well, but lands wherever it falls instead, indiscriminate as lightning or Covid-19. It’s the idea Peter Shaffer explored in Amadeus — that genius is not necessarily accompanied by refinement, modesty, self-awareness, common sense. Genius just happens — sometimes to a boxer in a Bolton gym, sometimes to a folk singer with heroin and alcohol dependency issues, sometimes to a sex-crazed Austrian man-child. And sometimes it emerges in a play that seems to celebrate troubling things (one major plotline in Jerusalem centres on the whereabouts of the local May queen, who has gone missing on the day the new May queen should be crowned).

I had my own reservations about Jerusalem after I first saw it a decade ago. Growing up in Wiltshire, where the play is set, I and many others felt that Butterworth’s high octane, technicolour version of our world seemed in part like an effacement of our reality, which really had more in common with the work of Shane Meadows than the world of this play.

Is there a future for English nationalism?

By Paul Mason

Jerusalem didn’t set out to represent our reality, of course — with its comedy vicar and Morris dancing, the play is more reminiscent of Alan Bennett or Martin McDonagh’s subversion of theatrical tropes in plays such as Habeas Corpus or The Beauty Queen of Leenane , its real references are in the theatre more than they’re in the real world. However, in a culture that paid no attention whatsoever to the world we came from, to feel that the one story set among us didn’t quite tell us right was a strange thing.

People who contributed to workshops during the play’s development have told me that the man they think Rooster is based on used to hang around the gates of a Wiltshire school, causing parents to drive in at the end of the day and collect their kids rather than letting them walk home, and ended up going to prison for several years for offences which were not entirely unrelated to this behaviour. To some, the play also effaces the impact of what he did. But this brings me back to Tyson Fury — Butterworth wasn’t trying to respectfully chronicle a Wiltshire community. He was writing about England’s rebel heart, asserting that the centre of our identity is actually to be found at the margins, in the woods, like Robin Hood.

Michael Billington has written of Jerusalem as a year zero for a golden period in contemporary British playwriting — so how will the play look to us, as it returns to an English theatre scene it so electrified once before? I think its darker themes will seem more prominent than they originally did. The MeToo movement and Jimmy Savile will make the unsettling story of the May Queen at the heart of the play ring out very clear indeed, and I wonder if that will turn the play into more of a challenge, a provocation to those who see it and enjoy it — a way of asking what exactly it is that they enjoy.

How Weinstein silenced everyone

By Jenny McCartney

Perhaps the play will even seem like an exploration of the darkness and deformity at the heart of England, in the tradition of the late, great Irish writer William Trevor’s novels, like the Whitbread Prize-winning Felicia’s Journey , which laid bare the rottenness that ran through so much of English life long before we’d heard the whole truth about Savile. I also think the play could seem sadder as well.

The hope glimpsed at the end of the play, that one day on this benighted island someone might find Drake’s drum, begin to beat it, and rescue us from the state we’re in, seems to me to have been more or less extinguished by a decade of austerity, a realisation of the climate crisis and the arrival of the coronavirus. Jerusalem might seem now like a story about people who, if they were in our capital, would all live in places like Grenfell Tower, and a man who hasn’t woken up yet to the hopelessness of that predicament, who is still left beating the same old drum.

What Jerusalem will show us above all is the England that is under threat. Here we all are, being obedient and doing what the state says, remaining indoors and preparing to accept unprecedented surveillance into our lives, as the price, poignantly enough, for our liberty.

Jerusalem seems to me like a howl in the face of that: an insistence that there are parts of us all, the part we recognise in Rooster Byron, that still can’t be policed. We’re going to need to work out how to protect and cultivate that aspect of ourselves, as we adapt to this new normal. Returning to Butterworth’s great play will afford us an opportunity to think about that.

Barney Norris is a novelist and playwright. His latest book, The Vanishing Hours , is published by Transworld.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber., join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits..

Well lockdown may not bother you, but it is devastating for some people.

Without doubt the best play I have ever seen. I went on the off-chance to the Royal Court to a £5 “restricted view” seat and still smile when I think about it over 10 years later

Interesting article, and thoughtful especially as regards what the play was getting at back then and how it might be experienced whenever its revival manages to get staged in what could still be some way off for much theatre-going.

I saw the play at the Royal Court when it opened in 2009; how time flies. Lovely set, with what looked like a real tree growing out from the stage and the involvement of an odd mix of characters. I was taken by the power of ‘Rooster’ Byron’s presence Mark Rylance-style and his riveting closing speech. Several very different friends who saw also saw the play during that short opening run were just as impressed by it, although I suspected I hadn’t understood something about it insofar as I didn’t think it was the best thing I’d seen. From that list of outstanding plays discussed by Michael Billington in the article linked-to, I consider several others of them to have been just as memorable. All the same, when ‘Jerusalem’ returns it will be worth others’ time trying to see it.

Oh what’s the point Middle class man waxes lyrically about a middle class art form

So what? There’s nothing wrong with being middle class, and Jerusalem is a brilliant play! I agree that this review is a bit naff, but the gist is a good point and you don’t have to read the review if you don’t like it.- Don’t miss the play, though, if it’s ever on again in the end.

The Problem of English Identity

And the play that lays bare Britain’s constructed myths

The week I saw Jerusalem , the West End revival of Jez Butterworth ’s extraordinary 2009 play, London was still cleaning up after a days-long ruckus celebrating Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee, the 70th anniversary of her reign. In my neighborhood, tattered bunting clung weakly to lampposts and gathered dirt under car tires at the side of the road. I picked bits of plastic flags and ice-cream wrappers out from my window boxes. In Chelsea, where the jubilee celebrations coincided with the annual flower show, retail stores and brands had created green installations on the street honoring totems of supposed Britishness: teapots made of daisies, a Union Jack formed from roses and hydrangeas, a larger-than-life crimson-stock Welsh Guard with a chrysanthemum corgi by his side. The effect was similarly striking and insincere, more advertorial than actual tribute—pomp and circumstance designed for Instagram.

That same week, Prime Minister Boris Johnson narrowly survived a vote of no confidence by his own party after months of revelations about his office’s conduct while Britain was on national lockdown amid the coronavirus pandemic. The slow drip of disclosed details about parties reportedly held by Johnson’s staff—including wine smuggled into Downing Street in suitcases, vomiting attendees, spilled red wine left for cleaning staff to mop up, two raucous parties held the evening before the Queen attended her husband’s funeral—was, if not fatal , extraordinarily damaging for Johnson’s repute. (Johnson, who was fined for attending his own birthday party, has apologized, but insisted “it did not occur to him” that the gathering was prohibited.) Entering St. Paul’s Cathedral for a Jubilee service honoring the Queen, he was booed by the assembled crowds. In context: For a conservative prime minister to have lost the favor of even the most ardent royalists during a momentous national celebration is about as bad as it gets.

Read: Boris Johnson has only delayed the inevitable

If you were looking for a summation of the state of contemporary England, that week laid it all bare: twee floral arrangements, the fetishization of history, cheap supermarket booze, privilege, appalling messes made for workers to clean up. Against this backdrop, Jerusalem felt to me less like a play than a prophecy. It debuted 13 years ago, before Brexit, before David Cameron’s austerity agenda, before the plight of the rural, white working classes had become electorally significant on both sides of the Atlantic. But with its portrayal of Johnny “Rooster” Byron, a small-time drug dealer and inordinately charismatic local menace about to be expelled from his existence near a bucolic village in southwest England, Jerusalem seemed to anticipate everything that was coming. To be English, it suggests, is to be part of a great contradiction recurring over and over. It’s to boast about the mythology of a national identity without remotely invoking it in practice; to wave a flag to Edward Elgar , ingest nothing but cider and pork scratchings for eight hours, and then extravagantly throw up in a corner. Nothing has ever been as crucial to England’s sense of self as storytelling, and yet it’s still surprising how much of its identity is based on things—exceptionalism, legend, the superiority of imperial measurements—that are so manifestly untrue.

I was living in the United States in 2009 and so missed Jerusalem ’s initial, wildly praised run in the United Kingdom. I couldn’t afford tickets to its Broadway production in 2011, for which the actor Mark Rylance won a Tony for playing Rooster. The current 2022 revival of the play at the Apollo Theatre in London, in which Rylance reprises his role alongside a number of original cast members, supposedly came about for prosaic reasons: Butterworth has said he simply wanted his daughter, who was too young to see it when it was first staged, to be able to watch it now. In a recent conversation for the online news platform Tortoise , he vehemently resisted the idea that Jerusalem was written as a state-of-the-nation play, or a drama with anything more topical on its mind than, as he puts it, “wanting to stay but having to go.” Its timelessness is, I’d argue, why it feels so timely now. The specific mess of Englishness, the collision of myth and reason, and the question of what it means to belong to a place that has no place for you are all more urgent than ever.

Read: Jez Butterworth on The Ferryman and the legacy of hate

The play has been received since its debut as an astonishing piece of art, and maybe even the best British play of the 21st century, the next 80 years be damned. It’s a mass of contradictions: a three-hour drama that passes in a blink; a feral howl of a comedy; a profane, slangy piece of art that honors Aristotle’s three unities—the principles of classical theater (the idea that where a play takes place, its time span, and its action should all be tightly constrained). The show takes place on St. George’s Day, April 23, in the woods outside a Wiltshire village where the construction of new houses is encroaching on the land where Rooster lives in a filthy old trailer. In the opening scene, Phaedra (played by Eleanor Worthington-Cox), a 15-year-old girl dressed as a fairy, sings “Jerusalem,” the strangely rousing British hymn that imagines Jesus visiting “England’s green and pleasant land.” When she gets to the word satanic in the second verse, the stage lights cut to black, electronic music blasts out like a violation, and the stage curtain rises on a rave in the woods. The old order of things has been rudely interrupted by the new.

Jerusalem takes place on a single day in a single location where all of the play’s characters come to commune: the council officials who want to evict Rooster, the teenagers who come to him for low-grade speed and solace, the former partner who wants Rooster to take his son to the fair, the villagers who think he knows more about a missing teenager than he’s letting on. The play hinges on Rylance’s performance, which is one of the most extraordinarily loaded and physical portrayals of a character in modern times. Rooster is a hedonist in the tradition of Falstaff and Keith Richards; he’s a satyr and a poet; he’s Milton’s rebel angel of unspeakable desires; he’s a cult leader; he’s the embarrassing old drunk who pissed himself in the pub corner and won’t go home. Rylance plays him with chest puffed out into grandiloquence, the painful shuffle of a man with no unbroken bones, and the periodic grace of a pixie. (In Rylance’s playbill listing for the show’s Broadway run, he specifically thanked his chiropractor.) During Rooster’s morning routine, he limps out of his trailer, dives into a handstand inside a trough of water to douse his hangover, and mixes himself a foul-seeming drink made out of a raw egg, vodka, sour milk, and a wrap of speed. When Rylance drinks it onstage, the audience explodes.

The tensions of the plot involve Rooster’s home, whether he’ll be able to keep it, and what will happen to the people who seek sanctuary of all kinds in the woods. The characters in Rooster’s orbit occupy varying states of permanence and flight: Ginger (Mackenzie Crook) is the oldest of his acolytes, who seems to have drifted to his side almost accidentally; Lee (Jack Riddiford) has sold all of his childhood possessions ahead of a voyage to Australia; Davey (Ed Kear) is so deeply rooted locally, he says, that if “I leave Wiltshire, my ears pop.” All seem to sense a kind of fabled significance in the place they call home. Lee talks about “ley lines,” or mystical lines of energy some believe link spiritual sites in England, and how Rooster’s wood, for the druids, would have been holy land. The teenagers who drink and fornicate and pass out in the woods seem to sense that they’re in a spot where the normal rules of society have never applied. In Jerusalem , as in Shakespeare, to go into the woods is to embrace anarchic lawlessness and surreal adventure. As Rooster bellows in one scene, “What the fuck do you think an English forest is for?”

For a play to be so unambiguously occupied with Englishness might provoke anxiety these days. The flag of St. George, the red-and-white flag that since the 1970s has tended to be a symbol of the ugliest kind of nationalism, is painted on the stage’s curtain as Phaedra makes her entrance. It’s a reminder that England is the country of Shakespeare, yes, and of profound past cultural power, but it’s also a small island whose bloated sense of self has historically had awful consequences. Before Jerusalem returned to the stage this year, a handful of playwrights expressed concern about how its supposed lionization of homeland and a “lost” England might play now. But this critique seems like a fundamental misreading. The play doesn’t condemn or boost any of its characters; it leaves space for audiences to interpret whether the town’s obsessive bureaucrats are the villains or whether Rooster is a loathsome threat endangering the local children.

My reading of Jerusalem , and my sense of why it registers at a slightly different frequency now, is that the play captures the potency of storytelling, for good and for bad. Rylance gives Rooster so much charisma that, as an audience member, you will his stories to be true. You ache for his fantastical yarns about 90-foot giants and his “rare” blood to be real, because they’re so much more compelling, and more moving, than the alternative. If Englishness is a place, it’s where pagan chaos meets tyrannical order. And the right kind of interpreter can mine magic from this kind of locale and its abundant clichés. (Nothing is more English about Rooster, I’d argue, than the moment he pours milk into three teacups on a tray clutched with an unshaking—albeit fiendishly hungover—hand.) But to lose sight of the fact that so much of our national identity as Englishmen and women is constructed and fake is to risk falling sway to darker impulses. What we’re left with at the end of Jerusalem feels like a warning: an extraordinary storyteller clinging dangerously to his own mythos in the vain hope that it will save him from eviction.

Culture | Theatre

Jerusalem review: 13 years on, time has only deepened Jez Butterworth’s modern classic

Covered in blood, myth and glory, Mark Rylance returns in triumph, 13 years on, to the career-defining role of Johnny “Rooster” Byron in Jez Butterworth ’s dazzling exploration of Englishness. Rooster is a charismatic, anarchic spirit: a perma-drunk yarn-spinner who supplies drugs and dance music to teenagers at his woodland caravan in Wiltshire. If anything, age has deepened the grain of Rylance’s overwhelming performance. And the questions Butterworth asked about national identity back in 2009 have only become more urgent.

There’s just so much in this magnificently profligate, three-hour epic, which can shift from sublime comedy to high drama in a heartbeat. It touches on folklore and religion, community and exclusion, land and ownership, sex and the great British tradition of underage drinking. Butterworth said recently that the play is about “wanting to stay but knowing you have to leave” – in other words, life and death.

He smuggles profound truths into witty dialogue. Rooster claims to have met a giant who built Stonehenge: the hilarious ensuing discussion on whether BBC Points West would have noticed the colossus is an oblique commentary on the ironing out of local differences and the homogenization of culture. The exchange between Jack Riddiford’s wrung-out Lee, heading to Australia, and cheerful slaughterman Davey (Ed Kear), who wants to stay put, get pissed and kill cows, analyses the perceived divide between citizens of somewhere and citizens of nowhere. It’s the leave vs remain debate turned upside down.

There’s also a freewheeling delight in language and storytelling throughout, Byron unspooling tall tales about his being born complete with a cloak, a dagger and a bullet between his fully-formed teeth, or being kidnapped by four Nigerian traffic wardens in Marlborough. In one early scene Rylance and a hangdog Mackenzie Crook – returning to the role of wannabe DJ Ginger, all the more sad now for being middle aged – delightedly bat the word “fracas” around like a shuttlecock.

Director Ian Rickson is again at the helm, in control but giving the narrative room to roam, and designer ULTZ pretty much replicates his original set of a decaying Airstream trailer becalmed between trees, with live chickens roosting underneath. Rooster still kicks off the show with a headstand in a water trough before knocking back a raw egg mixed with milk, vodka and speed.

I thought Butterworth might have boosted the roles of the three young female characters this time round, but no: they remain funny but essentially functional, representative of the way girls’ sexuality has historically been fetishized. It’s still quite a blokey play, although Rylance used a curtain call speech to praise producer Sonia Friedman and theatre owner Nica Burns, alongside Butterworth and the creative team. The one major, welcome difference is that the cast isn’t entirely white this time round.

Does Jerusalem deserve this revival? Unquestionably, yes. You could watch this play, and Rylance’s performance, every night of the too-short run and still find new dimensions to wonder at. Well, you can’t, because it’s sold out. But Rylance, now 62, has said he wants to play Rooster again at 70 and at 80. I hope I’m around to see it.

To Aug 7, jerusalemtheplay.co.uk

Radical, potent and still very funny — Jerusalem is storming the West End

Awesome, you're subscribed!

Thanks for subscribing! Look out for your first newsletter in your inbox soon!

The best of London for free.

Sign up for our email to enjoy London without spending a thing (as well as some options when you’re feeling flush).

Déjà vu! We already have this email. Try another?

By entering your email address you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy and consent to receive emails from Time Out about news, events, offers and partner promotions.

Love the mag?

Our newsletter hand-delivers the best bits to your inbox. Sign up to unlock our digital magazines and also receive the latest news, events, offers and partner promotions.

- Things to Do

- Food & Drink

- Coca-Cola Foodmarks

- Attractions

- Los Angeles

Get us in your inbox

🙌 Awesome, you're subscribed!

‘Jerusalem’ review

- Theatre, Drama

- 5 out of 5 stars

- Recommended

Time Out says

Mark Rylance lets the old magic flow once again as the stage performance of our lifetimes returns

The greatest play of the twenty-first century? A good play elevated by an extraordinary lead performance? A nostalgic, nationalistic relic of a pre-Brexit age?

All of these accusations have been levelled at ‘Jerusalem’, but it feels like the only unarguable truth as it returns is that Jez Butterworth’s 2009 drama – combined with Mark Rylance’s lead performance – is the most hyped play of our lifetimes, perhaps the most hyped play ever by a living writer.

It’s a hell of a weight for one show to carry. And in keeping the original production alive, director Ian Rickson and team haven’t allowed ‘Jerusalem’ to pass into glorious legend: it has to live up to its reputation.

And it does.

I saw it once before, in 2011, on the last of its three previous London runs. As I recall, there have basically been no changes. From Ultz’s verdant set of lush, towering trees overlooking a shabby caravan that seems to have simply been dropped in the Avon countryside to Rylance’s shamanic turn as the caravan’s inhabitant, Johnny ‘Rooster’ Byron, it’s all as I remember it.

And yet… ‘Jerusalem’ remains fresh and unexpected. In a weird way, its legend contributes to that: it’s been the subject of so much serious-minded discourse that it’s almost confounding to be thrown into a foul-mouthed comedy about Rylance’s drug-dealing old vagabond Byron and his various addled hanger-oners as they bum about the caravan, from which Rooster is due for imminent eviction as a public nuisance.

Hot media takes issued in advance of the play’s return have ranged from hand-wringing about whether its consideration of rebellious Englishness might now feel a bit Brexity to arguments that nobody would dare make it today because of political correctness gone mad. But watching it again, this all feels very silly. To say Byron represents nostalgia for an old England is to totally gloss over the fact he’s an actual Little England nightmare incarnate. And to say ‘Jerusalem’ wouldn’t be written now is to be wilfully blind to the fact that Butterworth’s plays haven’t felt in sync with prevailing trends since at least the ‘90s. (One concession to 2022 is a new programme essay from Gypsy, Roma and Traveller campaigner Tom Margetson – I don’t think Byron is meant to be a realistic portrait of a Traveller, but certainly he gets called ‘gyppo’ a lot, and the essay is welcome).

The endless discussions of ‘Jerusalem’ feels a bit irrelevant when you’re confronted by the reality of it

Really, this country’s simplistic, binary debates about nationalism are inadequate at framing Rylance’s ambivalent, unruly Byron. On one level, Butterworth is entirely uncelebratory of him: despite his charm, wit and gloriously florid phrasing, he’s also an out-of-control alcoholic whose coterie of ‘friends’ laugh at videos of him lying about paralytic and clearly only hang out with him for the Es and whizz. Even if he seems utterly unbothered by this, he is unarguably made to look pathetic in the second act when his sweet, wide-eyed son Marky is dropped off by the boy’s mother, Dawn (Indra Ové), for a promised trip to the local fair, and Byron feebly mumbles an excuse to get out of it. He is irresponsible, and not in a charming Robert Downey Jr style, just an old-school deadbeat dad way.

But then, there’s something about his sheer irrepressible nature that defies pity or revulsion. And for all his pathetic human frailties, the suggestion – intrinsically begged by Rylance’s superhuman performance – gnaws away that Rooster is somehow not entirely of our universe. There’s the very funny account from his pal Ginger (Mackenzie Crook, returning from the first cast) of how Byron apparently came back from the dead once; there’s Byron’s own story about how he once met an 80-foot giant who gave him a golden drum; he has many fantastical anecdotes that seem like addled, self-mythologising bullshit… but the thought increasingly occurs that perhaps everything Byron is saying might be true. Is he just a decrepit druggie, about to be finally crushed by the boring tide of southwestern suburbia? Or is he an ancient spirit of the woods, a last trace of an older, wilder, more dangerous world that we turned our backs on?

Key to Rylance’s titanic performance is that he’s effectively both at the same time: a limping, mumbling addict who is hated by the locals, finally reaping what he's recklessly sown; and a stocky, physically assured man who performs athletic headstands, knows the answer to every single question in Trivial Pursuit (sometimes even before it’s asked) and shares stories of supernatural beings he’s met with deadly earnestness. Rylance performs him as a frail human and a powerful folkloric being all at once; his Byron is the possibility of magic in this world, but also the probability of extreme disappointment. The play climaxes just as the wild magic is finally invoked and the giants are summoned. Is any of it real? On one level, we never find out; on the other, Rylance’s extraordinary final monologue, in which reality seems to warp and the room converges entirely on him, is clearly magic happening right in front of our eyes.

I doubt the legacy of ‘Jerusalem’ is really going to be settled until Mark Rylance leaves it, because the power of Rooster Byron as a character is so hard to separate from his performance (there have been smaller productions around the world, nothing approaching the scale of this one). Which is just fine: all the endless discussion of the play feels a bit irrelevant when you’re confronted by the elemental reality of the thing itself. Leave it to future generations to decide where it goes on a list. For a few months, it has returned to our dark, satanic mills. Come, you giants!

‘Jerusalem’ is virtually sold out. However, fresh tickets are released at 10am on Monday for that week’s performances from JerusalemThePlay.co.uk . And a limited number of day seats are available from the Apollo Theatre box office at 10am each morning (queue early!).

An email you’ll actually love

Discover Time Out original video

- Press office

- Investor relations

- Work for Time Out

- Editorial guidelines

- Privacy notice

- Do not sell my information

- Cookie policy

- Accessibility statement

- Terms of use

- Modern slavery statement

- Manage cookies

- Claim your listing

- Time Out Offers FAQ

- Advertising

- Time Out Market

Time Out products

- Time Out Offers

- Time Out Worldwide

Jez Butterworth

Everything you need for every book you read..

On St. George’s Day, Parsons and Fawcett , two representatives of the Flintock City Council, serve Johnny “Rooster” Byron papers, which demand that he immediately vacate the property that his mobile home sits on. The city plans to build a new housing development nearby, and they do not want Johnny and his rabble-rousing friends around disturbing people. Johnny rudely tells Parsons and Fawcett to get lost: he has intention of abandoning the land he has lived on for decades. After Parsons and Fawcett leave, several of Johnny’s acquaintances and friends come to visit him. The first of these is Ginger , who knows Johnny better than anyone and is annoyed that Johnny did not invite him to the party he threw the night before. Johnny makes up stories about why Ginger was not invited, none of which are convincing.

Johnny’s other visitors include a man he calls Professor , who has a tenuous grasp on reality. Johnny’s friend Lee is also there, having fallen asleep on Johnny’s couch the night before. It is Lee’s last day in Flintock: he plans to leave for Australia as soon at St. George’s Day is over. In addition to Professor and Lee, two young girls named Pea and Tonya crawl out from underneath Johnny’s trailer, where they’d been sleeping. Everyone talks excitedly about the events of the previous night and the upcoming fair to celebrate St. George’s Day. They also discuss the disappearance of Phaedra , a local teenager, whom no one has seen in weeks. Phaedra was last year’s May Queen and is expected to show up to the fair this year to transfer her crown.

Johnny’s friends help him create signs warning the local city council to stay away from his property. Johnny also tells stories about his past, all which are highly improbable. In the most notable of these stories, Johnny befriends a giant that is approximately 90 feet tall. Johnny claims that the giant gives him a large drum and tells him to bang on it whenever he runs into trouble. While Johnny is partying with all of his friends, his ex-girlfriend, Dawn , shows up with the son they have together, Marky . Dawn asks Johnny if he still plans to take Marky to the fair. Johnny apologizes and says he cannot because something else came up, and he does not plan to attend the fair. Dawn assumes that Johnny wants to stay home with his friends and do drugs, so she calls her new boyfriend to take Marky to the fair instead.

After Dawn and Marky leave, Troy Whitworth , Phaedra’s stepfather, shows up and asks Johnny where he can find his stepdaughter. He is convinced Johnny knows where she has gone. Rather than give Troy information, Johnny insinuates that Troy is sexually abusing Phaedra. This starts a verbal sparring match between Troy and Johnny, which ends with Troy telling Johnny that his friends don’t respect him. As proof, Troy relates a story about how two men named Frank and Danny walked by Johnny’s home the previous summer and found him passed out and covered in his own urine. According to Troy, when Frank and Danny spotted Johnny, they urinated all over him, and someone filmed it. Johnny looks around at his friends and realizes the story is true. In response, he storms off to his trailer and everyone else leaves to go to the fair.

After returning from the fair, several of Johnny’s friends come by to see how he is doing. He hides from some of them and speaks briefly to others. While he is out in the open, Parsons and Fawcett show up to remind him that people will be coming to destroy his property if he does not leave immediately. They leave him a signed petition calling for his displacement, which features hundreds of names. When they are gone, Phaedra comes out of Johnny’s trailer and asks him about the exchange. Johnny makes up a story and Phaedra does not push him to elaborate. Then, Phaedra pressures Johnny to dance with her before she gives up her position as the May Queen. Her request is innocent, and Johnny eventually gives in. While they are dancing, Troy shows up with two other men. Phaedra runs away as the men hold Johnny down and beat him. They also brand an X on each side of his face with a hot poker. When the assault is finished, they leave.

Ginger, who witnessed part of the assault but did not step in to help, asks Johnny what happened. Johnny angrily sends him away. As Ginger leaves, Johnny turns around to find Marky. Johnny tells Marky to live his life according to his own whims and to never conform to the pressures of broader society. Then, Johnny orders Marky to return to his mother, which he does. Now all alone, Johnny takes a can of gasoline and sets his mobile home on fire. Then, he utters a long and complicated curse aimed at everyone who is responsible for displacing him, all while beating the drum he claims to have received from a giant.

Join StageAgent today and unlock amazing theatre resources and opportunities.

Writers: Jez Butterworth

- Related Products

- Useful Articles

Show Information

Jerusalem is a raucous, provocative new work that tells of a modern, mythic English hero: Johnny “Rooster” Byron. During the course of this Tony-nominated play, Johnny tells tales, gets drunk, does drugs, dodges the authorities, and both charms and infuriates all that he meets. The play opens on the morning of the local county fair, and we discover that Johnny Byron is both the most and least popular man in town. The local authorities want to evict him, his son wants to spend the day with him, the town thug wants to teach him a lesson, and his ragtag group of friends want to party with him. Though he may be harried, harassed, bloodied, and bruised, Johnny is not a man to be beaten down. Johnny’s stand against the hypocrisy of modern suburban life is shocking, moving, and a wonder to watch unfold. Though Johnny may be a modern man, he has the spirit of England’s legendary giants of myth. With Jerusalem , playwright Jez Butterworth spins his own darkly comic, modern take on the classic English idyll.

Lead Characters

Johnny "rooster" byron, jerusalem - play, the professor, phaedra cox.

View All Characters in Jerusalem

- Guide written by

- Marielle Renée Rousseau

Jerusalem guide sections

Sign up today to unlock amazing theatre resources and opportunities.

Auditions & Jobs

Simonas Search - Submit for NYC Appointments New York, NY

New York, NY

Next Fall New York, NY

Lyric Theatre of Oklahoma 2024 Season - NYC New York, NY

Oops! This page is only accessible by StageAgent Pro members.

Take your performing arts career to the next level.

Gain full access to show guides, character breakdowns, auditions, monologues and more!

or log in to your account

You need a Pro account to access this feature.

UPGRADE TO PRO

or or log in to your account

- Write for us

Jerusalem: an English myth

Tom Howlett reviews Jerusalem at the Apollo Theatre

Tom Howlett

Thursday May 12 2022, 2:50pm

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share via Email

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on WhatsApp

In the collection of myths and legends that make up large parts of English history, there are two figures. One stands tall, proud, emblazoned in gold and beautifully scarred. King Arthur presides over all as a symbol of the chivalric past, a past where valour coats brutality and nobility shadows autocracy. But there is also a figure beside him, one mottled in green, appearing to have been hewn out of the very earth.

“[Rooster’s] vast shadow is a refuge for all the outcasts, burnouts and misunderstood”

This figure does not, as Arthur does, stand at the forefront of our cultural consciousness but instead lurks in the corners, the shadows, and the gaps in between. His vast shadow is a refuge for all the outcasts, burnouts and misunderstood. Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem takes this figure and peels away the overgrowth to reveal a spliff held in the lips, a rooster tattoo on the arm and an eye that holds within it the history of all the unnamed outlaws, drifters and renegades that have travelled ‘England’s mountains green.’ Jez Butterworth reveals Jonny ‘Rooster’ Byron.

Jerusalem was first performed at the Royal Court Theatre in 2009 and was instantly considered one of the greatest plays of the 21st century. In 2022 it returns to the Apollo Theatre – into a world much changed in its absence and ready to embrace its mythic majesty. The play opens upon the same gunmetal grey caravan, Mark Rylance as the same, awe-inspiring, terrifying Jonny Byron and the same script, unmatched, since its release, in wit and poignancy.

Jerusalem often poses the question of Jonny Byron’s constancy. Even asking him once, directly, how ‘the world turns. And it turns. And … you’re still here.’ To this, I have no answer, other than the fact that Mark Rylance is a force of nature and, even at 62, is able to give a performance of such staggering physicality and power that you question if it isn’t still 2009 and that we need Jonny ‘Rooster’ Byron now more than ever.

Every superlative and adjective has already been used to describe Jerusalem and it is, still, hilarious, tender, crude, frightening and all of the hundreds of words that have been used to desperately define its ineffable genus. But it is also timely, it seems strange to say about a play that was written thirteen years ago, by Jonney ‘Rooster’ Byron, the symbol for the displaced, the cast out and the misunderstood, is as pertinent as ever.

“[Jerusalem] captures a spirit of Englishness in a complicated melting pot of c words and Shakespearean allusions”

Rylance’s Jonny ‘Rooster’ is one of the great theatrical performances. From his puffed out chest, bowed legs and cockeyed stare he embodies his character’s namesake and excludes a powerful, menacing charisma that both attracts and repels you in equal measure. But, despite his sheer brilliance, he does not overshadow the rest of the cast, Mackenzie Crook, reprising his role as Ginger is reliably, amusingly pathetic and loyal, Gerald Horan’s Weasley jovial, affable and exceptionally funny. The young group or ‘rats’, as Jonny calls them, bring a vitality and reliability to the play. Each member of this ensemble draws out different parts of the quintessential adolescent experience, from Lee’s pursuit of something greater to Tanay’s unrequited attraction or Daviey’s sophisticated complacency.

The play is written in a charming equilibrium between crudity and elegance. It captures a spirit of Englishness in a complicated melting pot of c words and Shakespearean allusions. It is both ode and elegy to the mythic history of Britain, in which the folk stories of giants, werewolves, fairies and curses are forced into combat, both literally and metaphorically, by the banal, provincial bureaucracy of Kennet and Avon Council.

Green ‘Like a kettle set to boil’: The Son Review

The stage setting functions as a perfect representation of the majesty, beauty and power that the play places on the natural world. The trees pierce through the sky letting through rays of ethereal light which filter, in dappled streams, down to the characters below. The large metal caravan is a representation of Jonny himself, bruised, scarred, dented and yet gleaming. Its total stationariness but capacity to move also represents Jonney’s: both eternally present but inevitably transient.

Jerusalem is a play full of outcasts, those who don’t fit or don’t want to fit and has become one of the most established contemporary plays of the last twenty years. Yet, despite the praise, despite the place Jerusalem has carved itself in the literary canon, for the three hours I sat in the Apollo Theatre I saw the half-space, the refuge for the lost, beleaguered and unwanted. Our English history is a muddied, dark, disturbing mess of malapportioned reverence and undue faith but, inside its shadowy depths there lies a figure that represents something to be admired. So if we are to sing Jerusalem to praise Albion, let us not think of Arthur but instead scream the name Jonny ‘Rooster’ Byron.

Jerusalem by Jez Butterworth is on at the Apollo Theatre London until the 7th of August

Support Varsity

Varsity is the independent newspaper for the University of Cambridge, established in its current form in 1947. In order to maintain our editorial independence, our print newspaper and news website receives no funding from the University of Cambridge or its constituent Colleges.

We are therefore almost entirely reliant on advertising for funding and we expect to have a tough few months and years ahead.

In spite of this situation, we are going to look at inventive ways to look at serving our readership with digital content and of course in print too!

Therefore we are asking our readers, if they wish, to make a donation from as little as £1, to help with our running costs. Many thanks, we hope you can help!

- Latest stories

- Most Shared

Sponsored Links

- Limo Hire in London

- The Mays Anthology

Partner Links

- Sustainable events

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Critic’s Pick

Review: In ‘Jerusalem,’ a Once-in-a-Lifetime Performance, Again

Mark Rylance is back in a role that won him a Tony more than a decade ago. But this London production isn’t just coasting on past kudos.

By Matt Wolf

LONDON — There’s mighty, and then there’s Mark Rylance in “Jerusalem,” a performance so powerfully connected to its part that it feels almost superhuman. That’s as it should be for a play about a larger-than-life character named Johnny Byron, who demands an entirely fearless actor, and has one in Rylance.

None of this will surprise those familiar with this play by Jez Butterworth, which premiered with Rylance in the lead role at the Royal Court here in 2009; two years later, it transferred to Broadway and won Rylance the second of three Tony Awards. In a thrilling revival that opened Thursday at the Apollo Theater (running through Aug. 7), everything feels enriched by time.

Now 62, Rylance is considerably older than a man described in the text as “about 50.” But such is this actor’s boundless energy and enthusiasm that you can imagine him returning to the role again and again: Johnny defies all conventions, including those of age, and so does a wildly versatile actor who approaches this societal rebel as a kindred spirit.

The creative team, headed by Ian Rickson, the most empathic of directors , is the same as it was in 2009. To this run’s credit, it is no museum piece coasting on past kudos, but a vital experience with a revitalizing effect. Standing ovations are commonplace here these days, but the one at Wednesday’s final preview possessed a singular fervor that had Rylance jumping up and down with childlike glee at the curtain call.

In the show, Johnny, who goes by the nickname Rooster, walks with a halting gait that goes unexplained. Physical impediments, it seems, barely matter to this tattooed, barrel-chested reprobate, who performs a headstand within minutes of his arrival onstage. He then downs a mixture of vodka, milk and a raw egg, whose shell Rylance tosses into the audience. (On Wednesday, someone tossed the shell back, prompting a delicious double take from the star.)

Johnny’s outsize gestures are those of a man whose defiantly reckless existence is under serious threat. While the rural community in which he lives is holding its annual spring fete to mark St. George’s Day, Johnny tenaciously stays at the beat-up trailer he has long called home. A magnet for a cross-section of local hangers-on, including a loquacious professor (a beautiful turn from Alan David) and underage female adolescents hungry for spliffs and sex, Johnny’s illegal encampment is soon to be bulldozed. His young son arrives for a visit, only to be whisked away by the child’s disapproving mother (a persuasive Indra Ové).

Not only is Johnny faced with a final order from government officials to move on, but he must confront the wrath of Troy Whitworth (a fearsome Barry Sloane), whose 15-year-old stepdaughter, Phaedra, has sought refuge with Johnny. Troy will go to violent lengths to claim her back.

It’s Phaedra (Eleanor Worthington-Cox) who opens the play, singing the English hymn that gives “Jerusalem” its title and whose lyricist, William Blake, is referenced during a game of Trivial Pursuit later on. Worthington-Cox delivers this most stirring of tunes in front of a drop curtain depicting the cross of St. George, England’s flag. But the play itself transcends nationality to speak to any disaffected outsider who won’t be easily silenced and who gathers acolytes like moths to an inextinguishable flame.

I’ve now seen “Jerusalem” five times (including on Broadway), and Rickson’s current company — several of them holdovers, with Rylance — are as good as any predecessors, and sometimes better: Worthington-Cox is the most moving Phaedra I have experienced.

Mackenzie Crook remains especially heartbreaking as Ginger, Johnny’s friend and ally whose haunted eyes convey a premonition that his buddy’s days are numbered. Jack Riddiford, a company newcomer, brings a boyish appeal to the role of Lee, who dreams of starting afresh in Australia but is thankful for the raucous good times that Johnny has made possible on home soil.

You can imagine one or two of these characters as avid supporters of Brexit, though the idea didn’t exist when Butterworth wrote the play: The sweary abattoir-worker Davey (Ed Kear, another cast newcomer) doesn’t “see the point,” he says, of other countries, including neighboring Wales. British newspapers have been busily assessing “Jerusalem” as a defining state-of-the-nation commentary whose legacy and influence are incalculable . Butterworth has stayed out of the discussion , saying only that he revived the play so his young daughter, Bel, could see it .

But such considerations are academic next to the visceral immediacy of a play that soars as high as the designer Ultz’s ravishing tree-filled set, which seems to sweep up beyond the theater’s roof. That vast reach is of a piece with a performance you might describe as once-in-a-lifetime, if it weren’t so evident that Rylance’s passion for this part, thank goodness, seems far from over yet.

Jerusalem Through Aug. 7 at the Apollo Theater, London; jerusalemtheplay.co.uk .

- TV & radio

- Art & design

Playwright Jez Butterworth on Jerusalem, England and Englishness – video

Sarfraz Manzoor and Alex Healey , theguardian.com

Wed 2 Nov 2011 13.23 GMT First published on Wed 2 Nov 2011 13.23 GMT

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share via Email

Most popular

Palestinian Christians barred from Jerusalem’s Old City at Easter

During Gaza war, usual crowds of international worshippers are absent, and Palestinians face ‘unprecedented’ restrictions.

As Christians around the world prepare to celebrate Easter, Palestinians in the land that birthed the religion are facing severe restrictions on entering Jerusalem’s Old City to mark the occasion.

While at least 200 leaders from the occupied West Bank have been given permits to enter the area, their congregations are not being allowed access to participate in the services, said Al Jazeera’s Imran Khan, reporting from occupied East Jerusalem.

Keep reading

How is occupied east jerusalem’s diversity under threat, how jerusalem’s old city turned into a ghost town before my eyes, israel to restrict access to al-aqsa mosque during ramadan.

The restrictions are “unprecedented”, Khan said as a procession of worshippers, far smaller than the usual Good Friday crowds, walked the Via Dolorosa – the path Jesus is said to have followed on the way to his crucifixion more than 2,000 years ago.

The Old City is unusually empty owing to the war in Gaza , but Palestinian Christians were “desperate” to visit their places of worship, Khan said.

“Palestinian Christians from the occupied West Bank – not the international tourists who are staying away because of the war on Gaza – these are people who actually want to come to the Old City and celebrate Easter, but they’re not being allowed to.”

Christians are usually granted access to East Jerusalem , he said, although Palestinian Muslims routinely face restrictions. Access to Al-Aqsa Mosque has been denied to men under the age of 65 and women under the age of 50 on the third Friday of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan .

‘Dark days’

“These are very dark days, very difficult days,” the Reverend Munther Isaac said, speaking to Al Jazeera from Bethlehem in the West Bank. “I think the restrictions this year have definitely increased. Even for us here in Bethlehem – and Jerusalem is literally 20 minutes away from here – we don’t have access.”

“Jerusalem is very important for us, especially at Easter. We’re accustomed to … praying in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre ,” he said.

“This is part of our daily life under occupation. The war has added to our pain because of the magnitude of death and killing.”

Fayaz Dakkak, the owner of a family store selling religious souvenirs, said he was not expecting to make any sales. As the war rages on, the typical crowds from around the world have not descended on the city to visit the 12th-century Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the site where Jesus is believed to have been crucified, buried and resurrected.

“We’ve been feeling a lot more uncomfortable this time because there’s profiling. If you’re passing by any gate, whether it’s the Damascus Gate, New Gate, Jaffa Gate, and the police officer or the soldier feels you are not Israeli, you’re stopped, you’re checked,” he said.

“Most of the time, it’s not very pleasant,” he added. While some members of the security forces carry out straightforward ID checks, others are more “violent”, he said.

Rafi, a Christian youth coordinator, said Israeli settlers had made the Old City an almost no-go zone. “Even before the war started, we saw the settlers attacking the churches and even the Christian cemeteries,” he said.

“They were attacking any priest or any nun walking inside Jerusalem. Even the pilgrims walking the Way of the Cross [Via Dolorosa] were under attack.”

Many Palestinian Christians from the occupied West Bank have been deprived of walking the Via Dolorosa this year.

Even before the war, Palestinian Christian had to request permission to visit the Old City well in advance of celebrations. Last year, the Greek Orthodox Church slammed what it called Israel’s “ heavy-handed restrictions ” on freedom of worship during Easter.

Israeli police had said limits were needed for safety during the “Holy Fire” celebration at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, during which a flame taken from Jesus’s tomb in the church is used to light the candles of worshippers. Christian leaders said there was no need to alter a ceremony that had been held for centuries and they believed it was part of an ongoing Israeli policy to push Palestinians out of their homeland.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Butterworth's greatest success on the stage is Jerusalem (2009), which many critics regard as one of the greatest plays of all time and perhaps the best English play of the twenty-first century. His 2017 play, The Ferryman, also received widespread critical acclaim and reestablished Butterworth as one of the great contemporary English ...

Critics on the right, too, saw "Jerusalem" through a political lens. Quentin Letts, then the theatre critic for the right-wing Daily Mail, described the play at the Royal Court as "an ...

Jerusalem Summary. These notes were contributed by members of the GradeSaver community. We are thankful for their contributions and encourage you to make your own. Written by Patrick Kennedy and other people who wish to remain anonymous. The play begins with Phaedra, a fifteen year old girl dressed as a fairy singing in allusion that Jerusalem ...

Jerusalem study guide contains a biography of Jez Butterworth, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis. Jerusalem essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Jerusalem by Jez Butterworth.

Ironically, the play that is called Jerusalem and is (arguably) about England, was written in New York City. "I had a draft of it before," said the writer. "I was in New York producing a film in 2009.

"Jerusalem" is a great frame-busting play that still exists solidly within a conventional framework. The story of Johnny Byron's last stand against the philistines who would evict him from ...

Why I love Jez Butterworth's Jerusalem. The chewy language, the characters' sad bombast and above all the sense of place: England. This play is a chronicle of us, now. Laura Barton. Tue 25 Oct ...

That flag has, since Jerusalem's first staging in 2009, continued to be associated with the far right, and the play's bigger dewy-eyed ideas around Englishness carry a queasy proximity to the ...

I t was the play that had critics searching for superlatives and audiences queueing out of the door. When Jerusalem opened at London's Royal Court in 2009, it developed a near-mythical ...

Jerusalem tells the story of a man about to be evicted from his caravan in a Wiltshire wood by the Kennet and Avon council. It's about people living on the wild edges of society, and people who've fallen into the meat grinder of precarious rural life. It's about the lure of the lawless, the country's rebel spirit.

The week I saw Jerusalem, the West End revival of Jez Butterworth's extraordinary 2009 play, London was still cleaning up after a days-long ruckus celebrating Queen Elizabeth II's Platinum ...

The protagonist in Butterworth's 2009 play 'Jerusalem' comes in the form of Johnny Byron, a character that has been classed as 'one of the most compelling, complex and iconic characters in modern British theatre' by critic Paul Mason. He was portrayed by Mark Rylance. It is no doubt that the audience find the character comical,…

Nick Curtis @ nickcurtis April 29, 2022. Review at a glance. Covered in blood, myth and glory, Mark Rylance returns in triumph, 13 years on, to the career-defining role of Johnny "Rooster ...

And to say 'Jerusalem' wouldn't be written now is to be wilfully blind to the fact that Butterworth's plays haven't felt in sync with prevailing trends since at least the '90s.

Jerusalem Summary. On St. George's Day, Parsons and Fawcett, two representatives of the Flintock City Council, serve Johnny "Rooster" Byron papers, which demand that he immediately vacate the property that his mobile home sits on. The city plans to build a new housing development nearby, and they do not want Johnny and his rabble-rousing ...

J ez Butterworth is one of only two writers - the other is Lucy Kirkwood - to have a double entry in our list of the century's best plays. That seems only fair: Jerusalem and The Ferryman ...

Jerusalem is a raucous, provocative new work that tells of a modern, mythic English hero: Johnny "Rooster" Byron. During the course of this Tony-nominated play, Johnny tells tales, gets drunk, does drugs, dodges the authorities, and both charms and infuriates all that he meets. The play opens on the morning of the local county fair, and we ...

Jerusalem is a play full of outcasts, those who don't fit or don't want to fit and has become one of the most established contemporary plays of the last twenty years. Yet, despite the praise, despite the place Jerusalem has carved itself in the literary canon, for the three hours I sat in the Apollo Theatre I saw the half-space, the refuge ...

Jerusalem Through Aug. 7 at the Apollo Theater, London; jerusalemtheplay.co.uk. A version of this article appears in print on , Section C , Page 7 of the New York edition with the headline: A ...

Category: Literature. Topic: Book Review, Literary Devices. Pages: 2 (1027 words) Views: 1646. Grade: 5. Download. On making of the play, Butterworth had been "haunted by the nature of Englishness". He successfully portrays 'Jerusalem' as a peculiarly evocative play that is primarily based on the robust English identity- with embodies ...

As his roistering, raggedly brilliant play Jerusalem returns to the West End for the final time, the writer talks to Sarfraz Manzoor on what the script says about him - and how it relates to ...

A nun attends the Catholic Washing of the Feet ceremony during Easter Holy Week in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2024 [Ronen Zvulun/Reuters]