Attachment and Jealousy: Understanding the Dynamic Experience of Jealousy Using the Response Escalation Paradigm

Affiliations.

- 1 1 University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA.

- 2 2 Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA.

- 3 3 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel.

- PMID: 29771201

- DOI: 10.1177/0146167218772530

Jealousy is a complex, dynamic experience that unfolds over time in relationship-threatening situations. Prior research has used retrospective reports that cannot disentangle initial levels and change in jealousy in response to escalating threat. In three studies, we examined responses to the Response Escalation Paradigm (REP)-a 5-stage hypothetical scenario in which individuals are exposed to increasing levels of relationship threat-as a function of attachment orientations. Highly anxious individuals exhibited hypervigilant, slow escalation response patterns, interfered earlier in the REP, felt more jealousy, sadness, and worry when they interfered, and wanted to engage in more vigilant, destructive, and passive behaviors aimed at their partner. Highly avoidant individuals felt more anger when they interfered in the REP and wanted to engage in more partner-focused, destructive behaviors. The REP offers a dynamic method for inducing and examining jealousy and introduces a novel approach to studying other emotional experiences.

Keywords: adult attachment; emotion in relationships; emotions; romantic relationships.

- Anger / physiology

- Anxiety / psychology*

- Interpersonal Relations*

- Object Attachment*

Jealousy due to social media? A systematic literature review and framework of social media-induced jealousy

Internet Research

ISSN : 1066-2243

Article publication date: 12 April 2021

Issue publication date: 1 November 2021

The association between social media and jealousy is an aspect of the dark side of social media that has garnered significant attention in the past decade. However, the understanding of this association is fragmented and needs to be assimilated to provide scholars with an overview of the current boundaries of knowledge in this area. This systematic literature review (SLR) aims to fulfill this need.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors undertake an SLR to assimilate the current knowledge regarding the association between social media and jealousy, and they examine the phenomenon of social media-induced jealousy (SoMJ). Forty-five empirical studies are curated and analyzed using stringent protocols to elucidate the existing research profile and thematic research areas.

The research themes emerging from the SLR are (1) the need for a theoretical and methodological grounding of the concept, (2) the sociodemographic differences in SoMJ experiences, (3) the antecedents of SoMJ (individual, partner, rival and platform affordances) and (4) the positive and negative consequences of SoMJ. Conceptual and methodological improvements are needed to undertake a temporal and cross-cultural investigation of factors that may affect SoMJ and acceptable thresholds for social media behavior across different user cohorts. This study also identifies the need to expand current research boundaries by developing new methodologies and focusing on under-investigated variables.

Originality/value

The study may assist in the development of practical measures to raise awareness about the adverse consequences of SoMJ, such as intimate partner violence and cyberstalking.

- Individual differences

- Partner conflict

- Relationships

- Social media

- Systematic review

Tandon, A. , Dhir, A. and Mäntymäki, M. (2021), "Jealousy due to social media? A systematic literature review and framework of social media-induced jealousy", Internet Research , Vol. 31 No. 5, pp. 1541-1582. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-02-2020-0103

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Anushree Tandon, Amandeep Dhir and Matti Mäntymäki

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Social media platforms (SMPs), such as Facebook and Instagram, have undoubtedly had positive effects, such as the creation of an enhanced sense of well-being by reducing negative emotions ( Rozgonjuk et al. , 2019 ) and increasing self-esteem ( Holmgren and Coyne, 2017 ). SMPs have also been lauded for their potential to foster relationships ( Daspe et al. , 2018 ) and sustain social capital ( Holmgren and Coyne, 2017 ; Mod, 2010 ). The perceived benefits of SMPs may have catalyzed their pervasive adoption across the globe; consequently, their use has become an integral part of people's daily routines. According to recent estimates, the number of active social media users worldwide has surpassed 3 billion, and they spend an average of 136 minutes per day accessing SMPs ( Statista, 2019 ). Furthermore, the lockdowns that were implemented to fight the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic further increased the use of SMPs worldwide ( GlobalWebIndex, 2020 ; Tregoning, 2020 ). All of these factors have prompted increased scholarly efforts to understand the effects of SMPs – especially the negative side of increased SMP engagement (i.e., the dark side of social media) – on individuals' lives ( Tandon et al. , 2020 ; Islam et al. , 2019 ; Talwar et al. , 2019 ; Dhir et al. , 2018 , 2019 ; Baccarella et al. , 2018 ; Salo et al. , 2018 ; Mäntymäki and Islam, 2016 ). However, despite this considerable scholarly attention, distinct voids exist in regard to understanding the detrimental influence of SMP use patterns on various aspects of individuals' lives ( Rozgonjuk et al. , 2019 ). One void pertains to understanding social media-induced jealousy (SoMJ) as a distinct phenomenon ( Seidman, 2019 ; Demirtaş-Madran, 2018 ).

SoMJ was brought to the academic forefront by Muise et al. (2009) , who developed a scale to examine romantic jealousy in the context of Facebook. Their study has often been referred to as the foundation of the field of research examining jealousy in the context of social media ( Elphinston and Noller, 2011 ; Utz and Beukeboom, 2011 ). A recent report suggested that 33% of single individuals in the United States (US) can feel worse about their own lives after noticing SMP content about others' relationships, and 34% of young partnered adults (aged 18–29 years) and 26% of older adults have experienced jealousy or insecurity due to their partners' SMP use or activities ( Vogels and Anderson, 2020 ). Since its recognition in 2009, SoMJ-oriented research has steadily grown, but it is also subject to a certain degree of fragmentation and limitations.

The present study is positioned to fill three gaps in the extant body of SoMJ knowledge. The first gap relates to understanding the influence of SMPs on users' experiences of SoMJ, its antecedents, and its subsequent impact on interpersonal relationships ( Dunn and Ward, 2020 ; Demirtaş-Madran, 2018 ; Dijkstra et al. , 2013 ). In particular, there is a limited understanding of the intricate associations between an individual's SMP use, jealousy and other variables, such as individual differences ( Seidman, 2019 ). Second, there is a limited understanding of how online media, such as SMPs, contribute to the evocation of jealousy due to perceived or actual infidelity that is perpetuated through virtual means. Such infidelity may be attributed to emotional relatedness, closeness or friendship statuses among SMP users ( Dunn and Ward, 2020 ). Third, minimal research has explored the direct consequences of SoMJ for behavioral responses ( Muscanell and Guadagno, 2016 ), such as relational aggression or violent behavior ( Demirtaş-Madran, 2018 ) and infidelity ( Carpenter, 2016 ), as well as the outcomes for relationships, such as offline relational conflicts ( Daspe et al. , 2018 ). This is especially significant because SMP use has been linked to the potential breakdown of marriages. For instance, Holmgren and Coyne (2017) suggested that maladaptive SMP use is correlated with relational dissatisfaction ( Stewart et al. , 2014 ), especially for married couples ( Iqbal and Jami, 2019 ). According to a study by McKinley Irvin, a law firm in the US, 16% of married couples have linked Facebook to experiencing jealousy, 25% have experienced weekly arguments about Facebook use and 14% have contemplated divorce because of their partner's social media activities ( Starks, 2019 ). Thus, popular media and academic research have acknowledged that SMPs are redefining interpersonal relationships and promulgating jealousy ( Seidman et al. , 2019 ; Carpenter, 2016 ; Muise et al. , 2009 ).

Considering these gaps in the literature and the rising number of incidents that correlate SMP use with relational breakdowns and conflicts ( Starks, 2019 ), there is a need for researchers to examine the causes of SoMJ, as well as the mechanisms through which it can affect relationships. Consequently, we use the study of Muscanell and Guadagno (2016) as a conversant, or point of reference (cf. Huff, 1998 ) that presents a narrative review of the effect of SMP on romantic relationships in terms of jealousy and other emotions experienced by the affected individuals. This study extends their review in three specific ways. First, we undertake a systematic literature review (SLR; Ahmad et al. , 2018 ; Kitchenham et al. , 2009 ; Webster and Watson, 2002 ) to develop a comprehensive and holistic view of SoMJ. An SLR can effectively assist scholars in drawing a comprehensive overview of the existing literature in a field ( Kushwah et al. , 2019 ; Talwar et al. , 2020a ; Khanra et al. , 2020 ; Dhir et al. , 2020 ). Based on their comprehension, scholars can draw conclusions about the phenomena under investigation through the SLR and identify incumbent research gaps, which can have significant implications for the advancement of both theory and practice ( Khanra et al. , 2020 ; Dhir et al. , 2020 ). Thus, the primary objective of this study is to assimilate and critically analyze the extant literature to explicate the current intellectual boundaries of the SoMJ concept, identify its antecedents and consequences, and suggest future research avenues based on the identified gaps. Subsequently, the second way in which our study contributes to the research on SoMJ and the dark side of social media is by explicating emergent research themes and associated gaps in the prior knowledge on SoMJ to propose potential avenues for future research. Third, we offer a contemporary profile of prior research by reviewing studies from 2009, when one of the first seminal studies in this field was published ( Muise et al. , 2009 ), to 2019. Thus, this SLR assimilates a decade of research on SoMJ to report on state-of-art research trends and identifies avenues to advance theory and research through the proposed SoMJ framework. Our findings – especially the identified antecedents and consequences of SoMJ – have the potential to assist practitioners (e.g., clinicians) to generate public awareness regarding the adverse effects of SoMJ in relational management. We believe that our SLR is well-timed due to the increasing number of reports that have highlighted that jealousy, acrimony, and stress due to social media use may have increased during the COVID-19 lockdown (e.g., Tregoning, 2020 ; Li et al. , 2020 ).

To the best of our knowledge, only one existing SLR aligns with the theme of the current study (see Rus and Tiemensma, 2017 ). However, it focused on explicating the associations between romantic relationships and social media. In contrast, the present study focuses on a more comprehensive and holistic examination of SoMJ, assimilating prior empirical information related to its antecedents and consequences to delineate gaps in the current knowledge. Thus, the novelty of this study lies in its significant difference from the earlier SLR due to the adoption of a holistic perspective and a more focused research theme and scope. This SLR is guided by the following research questions (RQs): RQ1 : What is the current status and profile of research on SoMJ? RQ2 : What are the focal themes, antecedents, and consequences of SoMJ that have been discussed in the prior literature? RQ3 : What are the gaps in the extant literature, and what future research avenues can be identified based on these gaps?

The findings suggest that prior research focused attention on understanding the (1) theoretical and methodological approach to the concept of SoMJ; (2) influence of sociodemographic differences in SoMJ experiences; (3) antecedents in terms of the incumbent actors – that is, individuals, partners and rivals – as well as relational parameters and platform affordances; and (4) positive and negative consequences of SoMJ. Based on our findings, we have also proposed a framework derived from the explicated research gaps and the hitherto under-explored associations of SoMJ to guide future scholars. This SoMJ framework discusses the scope for advancing conceptualization, the methodological approaches, the role of incumbent actors and the potential moderator variables. Regarding the antecedents, these associations are related to individual-partner characteristics, perceived rivals and relational dynamics. Additionally, the framework directs attention toward the need to examine the effect of SoMJ on individuals' online and offline emotions and actions toward their partners and rivals.

The remainder of this manuscript addresses the RQs. Section 2 commences with an overview of the concept of jealousy and the social media features that have the potential to evoke this emotion among users. Section 3 explicates the protocols adhered to for this SLR, as well as the details of the extant research profile in terms of noteworthy contributing authors, publication trends, and methodologies. Section 4 focuses on the emergent research themes derived from the SLR. Section 5 discusses the existing gaps and the potential future avenues for research. Additionally, it proposes an SoMJ framework for the future examination of SoMJ, which constitutes a significant contribution of this study. Finally, Section 6 presents the concluding remarks, as well as the implications and limitations of this study.

2. Background literature

2.1 jealousy.

Jealousy is defined as a metamorphic compound emotion that encompasses a compendium of feelings ( Kristjánsson, 2016 ; Pfeiffer and Wong, 1989 ). The extant literature suggests that the multifaceted nature of jealousy is yet to be equivocally defined and conceptualized ( Kristjánsson, 2016 ). However, the concept of jealousy may be broadly characterized as the perceived or actual threat of losing a valued relationship ( Muise et al. , 2014 ). It may also be understood as an emotional response to such a perceived threat ( Utz and Beukeboom, 2011 ; Pfeiffer and Wong, 1989 ), where in most instances, the valued relationship is primarily romantic or sexual in nature ( Dijkstra et al. , 2013 ).

Prior studies have offered divergent characterizations of the various dimensions of jealousy, especially with regard to individuals who are engaged in romantic relationships. For instance, Pfeiffer and Wong (1989) characterized jealousy as incorporating behavioral (partner surveillance activities), cognitive (appraisal of threats or suspicions), and affective (negative emotions experienced due to perceived threats) dimensions. Utz and Beukeboom (2011) also discussed different forms of jealousy – namely, reactive, anxious and possessive. While reactive jealousy results from an actual threat arising out of any form of infidelity, anxious and possessive forms of jealousy may arise out of a perceived threat that causes rumination and monitoring behavior, respectively. Dainton and Stokes (2015) posited that individuals might also experience cognitive and emotional types of situational jealousy in romantic relationships due to the inherent uncertainty of such relationships. In addition, Frampton and Fox (2018) distinguished between the concepts of retrospective and retroactive jealousy. Retrospective jealousy is directed at a rival who threatened a current relationship in the past, while retroactive jealousy is evoked by an individual's focus on his or her partner's previous relationship(s) ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ).

Prior research indicates that jealousy is associated with a mixture of emotions, including disgust ( Muscanell and Guadagno, 2016 ), betrayal ( Daspe et al. , 2018 ), resentment ( Dunn and Ward, 2020 ), sadness ( Macapagal et al. , 2016 ), threat and anger ( Dijkstra et al. , 2013 ), and envy ( Miller et al. , 2014 ). Further, Dunn and Ward (2020) suggested that jealousy incorporates the direction of an individual's emotions, such as distrust or resentment toward their partner/significant other due to suspected infidelity and/or romantic contact with a rival. Scholars have also characterized jealousy as a multifactorial phenomenon that encompasses various forms of behavioral reactions – for example, violence ( Demirtaş-Madran, 2018 ) and thoughts and actions that may affect the quality or stability of a relationship ( Moyano et al. , 2017 ).

Thus, we extend prior definitions of jealousy to the context of SMPs. We propose that SoMJ may be understood as the “jealousy experienced by an individual due to a potential threat (perceived or actual) of the loss or deterioration of a romantic relationship due specifically to their partner's or spouse's use of and activities undertaken on SMPs, especially if such activities involve a potential rival for extra-dyadic, romantic attention.”

There seems to be an overlap between the concepts of jealousy and envy, which are often used interchangeably in the general vernacular ( Dijkstra et al. , 2013 ). Scholars argue that despite their similarities, jealousy and envy differ. Chung and Harris (2018) suggested that jealousy and envy may be driven by different emotional processes and perhaps even different motivations. Kristjánsson (2016) argued that envy is considered to be a distinct emotion that relates to an individual's desire to attain an object of attention that is deemed to be absent from his or her life. Similarly, Dijkstra et al. (2013) suggested that envy is related to two people, thus suggesting a duality of interaction. In contrast, jealousy is described as the fear of losing an already obtained person or relationship to another person and creates a triangle of potential interaction ( Kristjánsson, 2016 ; Dijkstra et al. , 2013 ). Therefore, we concur that envy and jealousy are distinct emotional states ( Chung and Harris, 2018 ). The present study focuses solely on SoMJ.

2.2 Social media features: the potential to evoke jealousy

The extant research suggests that social media may affect an individual's experience with jealousy, and multiple studies have aimed to understand the association between social media and jealousy. In their seminal study, Muise et al. (2014) measured Facebook jealousy as a singular dimension that may be characterized as a form of trait jealousy ( Cohen et al. , 2014 ). Social media has been described as a complex tool and environment for initiating and maintaining communication with partners ( Fleuriet et al. , 2014 ). Scholars suggest that some aspects of social media can assist individuals in maintaining interpersonal (e.g., romantic) relationships ( Dainton and Stokes, 2015 ) and facilitating peer interactions ( Rueda et al. , 2015 ). For instance, indicating one's relationship status on social media may be interpreted as a public display of affection and an announcement of the exclusivity of the relationship within one's social circle ( Orosz et al. , 2015 ). This has been referred to as going “Facebook official,” which has previously been linked to relational satisfaction ( Seidman et al. , 2019 ). Similarly, SMPs may also assist individuals in maintaining long-distance relationships by allowing virtual proximity despite geographical distance ( Billedo et al. , 2015 ).

SMPs, such as Facebook, also have certain features that may contribute to an enhanced perception of jealousy-inducing threats. According to Muscanell and Guadagno (2016) , the public (i.e., transparent) and permanent nature of the information that is present on SMPs may have significant ramifications for inducing jealousy, which is contingent on users' motivation and usage of these platforms. SMPs, like Facebook, may create an environment with limited privacy ( Iqbal and Jami, 2019 ) and have the potential to induce unrestrained flirtatious behavior ( Brem et al. , 2015 ). User-specific settings for privacy and content sharing have also been implicated for their potential to evoke negative emotions, such as jealousy, and behavioral responses (e.g., Muscanell and Guadagno, 2016 ; Muscanell et al. , 2013 ). Furthermore, prior studies indicate that acontextual ( Muise et al. , 2009 ) and ambiguous information on SMPs may increase partner-monitoring or surveillance behaviors ( Muscanell and Guadagno, 2016 ). In fact, SMPs are considered to provide individuals with a socially acceptable form of monitoring their partners' activities ( Brem et al. , 2015 ; Muise et al. , 2014 ). Such monitoring may occur through multiple modes, such as sharing passwords ( Bevan, 2018 ), reviewing photos shared by partners or friends ( Halpern et al. , 2017 ), and accepting new SMP friend requests ( Carpenter, 2016 ). Similarly, it has been suggested that other aspects of SMPs, such as the use of nonverbal cues (e.g., emoticons), also evoke jealousy ( Daspe et al. , 2018 ).

Consequently, it can be argued that social media can have a dual effect on relational maintenance and quality by influencing an individual's experience with jealousy. In the context of Facebook, Altakhaineh and Alnamer (2018) explained that such platforms can help users maintain continual connections with close as well as distant relationships but also have the capacity to evoke suspicion and jealousy in romantic relationships. Additionally, such an impact may differ in its emergent form due to gender ( Demirtaş-Madran, 2018 ), personality ( Seidman, 2019 ) and even cross-cultural differences ( Iqbal and Jami, 2017 ; Zandbergen and Brown, 2015 ). This contradictory nature of the possible impact of Facebook on social relationships has been referred to as the “Facebook paradox” ( Altakhaineh and Alnamer, 2018 ). Due to the evidentiary link between SoMJ and the posited adverse effects on marriages ( Starks, 2019 ) and romantic relationships – for example, through intimate partner violence ( Brem et al. , 2015 ) – we argue for an urgent need to better understand the association between social media use and jealousy. Consequently, newer empirical investigations are required to bridge the existing gaps in the literature. However, this will first require an understanding of the current scope and boundaries of the previously investigated associations. Thus, it is necessary to identify the existing gaps and the scope of future research on this topic. The current SLR study aims to address these gaps by presenting the thematic areas of prior research, identifying gaps, and outlining agendas for future research based on identified gaps.

To conduct the review, we followed the protocols suggested by Behera et al. (2019) , Ahmad et al. (2018) , and Kitchenham et al. (2009) . These protocols were followed to ensure the transparency and reproducibility of the systematic method used to assimilate the data set ( Tranfield et al. , 2003 ). This study was conducted in two distinct stages. The first dealt with the determination of the search and article selection criteria, and the second pertained to the presentation of the results. The data set was curated following the results arising from both direct search and citation chaining to present an exhaustive, structured overview ( Kitchenham et al. , 2009 ; Webster and Watson, 2002 ). The SLR focused on curating current empirical knowledge on SoMJ and the possible association between social media use and jealousy.

3.1 Article search and selection

The review process began with the identification of appropriate search terms and databases, as well as the subsequent determination of search syntaxes. Jealousy is a multifaceted construct ( Kristjánsson, 2016 ), and SMPs have been investigated in the context of multiple disciplines, including psychology, information technology, sociology, and medical science ( Fox and Moreland, 2015 ). Consequently, the current study considered four databases from which to select the relevant literature: Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), PsycINFO and PubMed. These were determined to provide appropriate coverage of the literature ( Sigerson and Cheng, 2018 ). The concept of SMP-induced jealousy was seminally conceptualized in 2009 ( Muise et al. , 2009 ). Therefore, to synthesize a decade of academic attention to the association between social media and jealousy, the review process considered all the relevant articles published between 2009 and 2019. The databases were searched in December 2019 using the keyword “jealousy” in conjunction with “social media,” “social networking,” and “SNS.” In addition, the specific names of SMPs – namely, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, Twitter, WeChat and Weibo – were utilized in the search.

The initial search identified 121 results, which were reviewed to remove duplicates. Subsequently, following specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, 45 original studies were identified for further review (see Figure 1 ) and assessed for quality and appropriateness. At this stage, five studies were removed because they were considered inappropriate either due to a lack of empirical focus on jealousy or insufficient discussion of the associations and findings. To complete the feedback loop, backward and forward citations were conducted for the 40 remaining studies. Over 700 studies, which had been referenced by or referred to an article, were reviewed using a backward and forward citation search, which led to the addition of five studies to the final data set. To ensure the robustness of the review process, citation chaining was performed, as well as a subsequently curated data set, as suggested by the methodological literature ( Tranfield et al. , 2003 ; Webster and Watson, 2002 ). The selection process was reviewed by two coauthors at each stage to ensure the comprehensiveness of the overall process. Subsequently, 45 studies were identified as appropriate for further analysis; these constitute the final data set for this study (see Table 1 ).

3.2 RQ1 . Research status and profile

The curated data set of 45 empirical studies was analyzed to determine the status of the research on understanding the association between social media and jealousy. Since 2009, the publication trend shows increasing scholarly attention being focused on the examination of SoMJ (see Figure 2 ), but this attention has been concentrated primarily on Facebook as the platform of investigation (68.9% of studies; see Table 1 ). Further, the data set was analyzed to understand the geographic scope of prior studies, which suggests that studies have focused primarily on examining SoMJ in the context of developed nations, such as the US ( n = 22), the United Kingdom ( n = 3), Canada ( n = 3), and the Netherlands ( n = 3), while significantly less attention has been paid to the context of developing nations, such as Pakistan ( n = 2), the United Arab Emirates ( n = 1), and Turkey ( n = 1). Additionally, from a cultural perspective, it may be said that the current understanding of this phenomenon is skewed toward research originating from more individualistic cultures, with a lack of studies focusing on more community-oriented, collectivist cultures. The leading journals in terms of publication productivity are Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking ( n = 7), Computers in Human Behavior ( n = 5), Evolutionary Psychological Science ( n = 2), Journal of Social and Personal Relationships ( n = 2) and Personal Relationships ( n = 2). Finally, word clouds were generated for titles and author as well as indexed keywords of select studies to identify focal research issues. The word clouds suggested that SoMJ has primarily been studied in the context of romantic relationships with Facebook as the platform, as the dominant keywords identified from the figures included “social,” “jealousy,” “Facebook,” “romantic,” “relationships” and “media.”

4. RQ2 . Findings of the review: focal themes of prior research

Prior research has addressed multiple aspects of the association between jealousy and social media. However, a cohesive perspective and holistic overview of the myriad variables, frameworks, and approaches that have been previously adopted to study these associations is absent. Our study addresses this gap by detailing the emergent research themes and gaps in the current body of knowledge. These themes and gaps have been discussed and used as a foundation for detailing potential avenues that may be addressed by future research (see Table 2 ).

The review included several iterative rounds of open and axial coding ( Corbin and Strauss, 2014 ) of the articles' contents. First, two of the authors independently reviewed all the articles and made several notes regarding the focal content of each (cf. Paliogiannis et al. , 2019 ). After the first round of reviews, they gave titles to these notes to enable them to formulate a set of open codes. Thereafter, they compared their notes and discussed their respective open codes to reach a consensus. The open codes that were assigned included “gender difference,” “age difference,” “theoretical lens,” “methods of study,” “individual traits,” “partner-oriented factors,” “relational maintenance,” “relational outcomes” (positive and negative), “content sharing” and “SMP use.”

After agreeing on the final set of open codes, the two authors individually studied the similarities and differences in their content and the reviewed articles to enable them to formulate a preliminary set of axial codes representing the key themes emerging from the reviewed literature. The authors met to discuss and agree on the final axial codes. These codes pertained to “platform features,” “sociodemographic differences,” “individual-related antecedents,” “partner-related antecedents,” “relationship-related factors,” “consequences,” “theoretical grounding of the concept” and “methodology adopted.” After the axial coding, inter-coder reliability was assessed using the Kappa statistic ( Landis and Koch, 1977 ). The Kappa was 0.84, suggesting that the coding was consistent and that inter-coder reliability was sufficient.

Once the axial coding was completed, the themes that emerged from the coding were analyzed to identify the gaps in the current knowledge and propose specific questions that could be addressed by future scholars to advance research on SoMJ. The appropriateness of the themes was assessed and discussed by all three authors, as well as by an expert panel consisting of three professors and one researcher who had expertise in the dark side of social media. The panelists suggested that minor modifications be made to the derived future research avenues, and this was subsequently done. The following sections present each of the four themes identified in the review.

4.1 Theoretical and methodological grounding of the SoMJ concept

The concept of jealousy in the context of SMPs has primarily been relegated to the characterization of Facebook jealousy, as proposed by Muise et al. (2009) . Few recent studies have utilized additional theoretical approaches to examine the association between social media and jealousy; these include White and Mullen's jealousy model ( Carpenter, 2016 ) and the cognitive theory of jealousy ( Demirtaş-Madran, 2018 ). Concurrently, extant literature has witnessed the incorporation of multiple frameworks and theoretical lenses, wherein certain theories have witnessed more usage. For instance, attachment theory ( Bretherton, 1992 ) has been used by Chang (2019) and Fleuriet et al. (2014) , the parental investment theory ( Trivers, 1972 ) has been used by Dunn and Ward (2020) , and the model of relationship investment ( Rusbult, 1980 ) has been used by Drouin et al. (2014) (see Table 1 ). These frameworks are broadly aimed at understanding how individuals form bonds with others, using evaluative measures of relational satisfaction or gender-based differences in their interactions. However, other viewpoints, such as the evolutionary perspective of gender differences ( Demirtaş-Madran, 2018 ) and the uncertainty reduction theory ( Stewart et al. , 2014 ), have also been used sporadically to delineate the differential effect of parameters such as relational satisfaction.

Previous researchers have also considered other theories in an attempt to delineate the influence of individual factors, such as personality, usage motives and goals, on the association between social media and jealousy. Such theories include the uses and gratifications framework ( Dainton and Stokes, 2015 ), five-factor personality model ( Seidman, 2019 ), self-selection hypothesis ( Iqbal and Jami, 2019 ), goal cognition theory ( Chang, 2019 ), belongingness/connection framework ( Seidman et al. , 2019 ) and the theory of motivated information management ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ). Recent studies have begun to use the general theory of addiction to investigate the association between jealousy and the excessive use of SMPs ( Holmgren and Coyne, 2017 ). For instance, Seidman et al. (2019) examined the association between social media and jealousy in the context of needs that may encourage pathological SMP use, such as the need for popularity.

In terms of research design and methodology, few studies in the SLR pool have included dyadic forms of investigation (e.g., Marshall et al. , 2013 ), which may assist in understanding the connotations of this association from a partner's perspective through frameworks such as the actor–partner interdependence model ( Daspe et al. , 2018 ). Further, the majority of the current knowledge in this field has been derived from survey and experiment-based research designs (see Table 1 ), which may be inherently subject to limitations, such as social desirability bias ( Halpern et al. , 2017 ) and inability to establish causal effect ( Chang, 2019 ).

4.2 Sociodemographic differences

The extant literature presents evidence of demographic differences in the evaluation of social media content; the use of SMP information for relationship initiation ( van Ouytsel et al. , 2016 ); and the subsequently evoked negative emotions, such as jealousy ( Altakhaineh and Alnamer, 2018 ). Prior research has examined the influence of gender ( Demirtaş-Madran, 2018 ; Dunn and Billett, 2018 ), age ( Altakhaineh and Alnamer, 2018 ; Demirtaş-Madran, 2018 ) and culture ( Zandbergen and Brown, 2015 ) on an individual's experience of SoMJ. Sociodemographic factors present an interesting area of inquiry because they can potentially influence the mechanisms through which SoMJ may develop or increase in intensity ( Demirtaş-Madran, 2018 ).

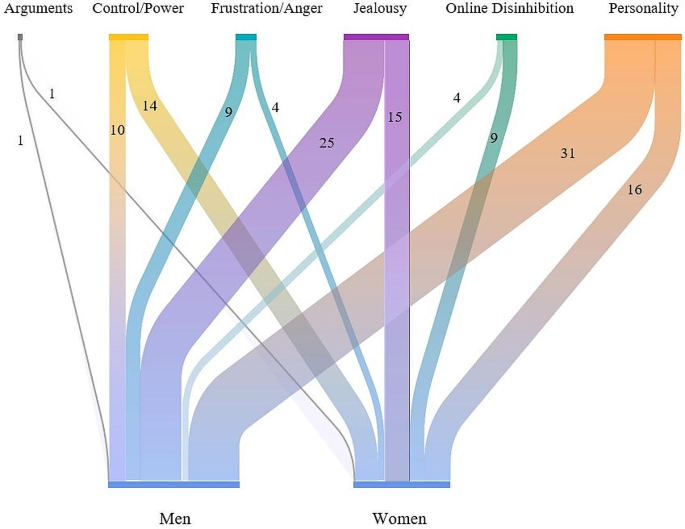

The divergence in prior knowledge on SoMJ is especially evident in terms of gender-based differences. Studies conducted by Baker and Carreño (2016) and Lucero et al. (2014) suggest that there is a distinct difference in the effect of social media cues on male and female experiences of jealousy. Similarly, Demirtaş-Madran (2018) discuss that gender differences may exist with regard to the type of jealousy experienced – that is, emotional or sexual – due to social media-associated cues but found none in terms of the level of jealousy experienced. This finding partially supports the additional research that found that males may show a higher response toward perceived sexual jealousy. In contrast, higher jealousy levels are evoked in women who perceive emotional infidelity in their partners' social media activities ( Dunn and Billett, 2018 ). Similarly, gender differences have been posited in terms of the intensity of experienced jealousy ( Marshall et al. , 2013 ), type of negative emotion felt by women vis-à-vis men ( Muscanell et al. , 2013 ), and behavioral response to the experienced emotion, for example–partner monitoring ( Muise et al. , 2014 ).

The literature reviewed for the SLR also suggests that age, stage of individual development, level of immersive exposure to social media communication patterns, and norms may create individual differences in SMP use. This may, in turn, affect the determination of the threshold criteria for determining the perception of cyber abuse, social media surveillance, or partner monitoring ( Baker and Carreño, 2016 ). For instance, Altakhaineh and Alnamer (2018) found that older users may not be well versed in the different multimodal affordances of social media, which could explain their differing thresholds for defining inappropriate social media behavior. Additionally, van Ouytsel et al. (2016) pointed out differences between adults' and adolescents' use of SMP content for relationship initiation through the findings of their study.

Culture and ethnicity are important factors that may explain individual differences in social media use and the subsequent experience of jealousy. According to Demirtaş-Madran (2018) , culture may be a universal influence with respect to jealousy. Zandbergen and Brown (2015) found that culture exerted a significant influence on jealousy experienced due to sexual infidelity and its form of expression. Similarly, Dijkstra et al. (2013) suggested the potential influence of societal norms on behavioral responses evoked by jealousy, such as higher aggression and violence by males. The SLR suggests that the extant knowledge rests primarily on the study of Caucasian respondents (e.g., Seidman, 2019 ; Frampton and Fox, 2018 ). Ethnic considerations may influence use patterns of Internet and Communication Technology (ICT, Rueda et al. , 2015 ) and dynamics of a relationship ( Demirtaş-Madran 2018 ), such as intimate partner violence, social media surveillance or romantic gestures. The fact that the evocation of jealousy is a process that may have cultural and ethnic distinctions, e.g. in of retroactive jealousy ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ), may explain evident differences in prior findings.

4.3 Antecedents

The prior literature has identified multiple factors that may affect the origin, intensity, and impact of SoMJ on an individual. These factors, referred to as antecedents of SoMJ, are delineated into four dimensions: the individual, his or her partner, relationship, and platform affordances.

4.3.1 Individuals

Individual factors that may affect the level and intensity of SoMJ have been the most extensively investigated antecedents in this domain. Prior research on these antecedents has pertained primarily to an individual's attachment orientation, personality, needs, motives and engagement with specific social media activities. Individuals may be driven to use SMPs to fulfill different needs, which may include the need for popularity ( Utz et al. , 2015 ), idealized self-presentation ( Seidman et al. , 2019 ) and motive/need to belong ( Seidman et al. , 2019 ; Chang, 2019 ). These needs may be further complemented by the goals and motives that drive individuals to engage with social media. Such motives may be related to purposes such as information seeking prior to initiating a relationship ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ; van Ouytsel et al. , 2016 ) or relational maintenance ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ; van Ouytsel et al. , 2016 ). Holmgren and Coyne (2017) suggest that the self-regulation of SMP use and the needs fulfilled through social media may enact a mediating effect on psycho-social and relational outcomes. This effect may occur due to the jealousy induced by engaging in comparisons with peers over SMPs and allied conflicts ( Halpern et al. , 2017 ; Holmgren and Coyne, 2017 ). Furthermore, comparisons may also be made about the previous romantic partners of an individual, for example through digital remnants ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ) and even strangers.

Prior research indicates that an individual's attachment style and orientation may also impact the association between social media and induced jealousy ( Fleuriet et al. , 2014 ; Muise et al. , 2014 ; Nitzburg and Farber, 2013 ). Attachment orientation pertains to an individual's propensity to form and maintain close romantic bonds along the dimensions of anxiety and avoidance ( Chang, 2019 ; Rus and Tiemensma, 2017 ). An individual's attachment style may determine his or her engagement with social media activities ( Nitzburg and Farber, 2013 ), such as checking a partner's profile ( Marshall et al. , 2013 ). Muise et al. (2014) posited that attachment orientation might be enacted differently for individuals as a mechanism of the effect that induces jealousy. Nitzburg and Farber (2013) found that highly anxious or disorganized individuals may inculcate psychological distance into their relationships while attempting to balance emotions and interpersonal conflicts. Marshall et al. (2013) found that individuals with anxious attachment experience more chronic jealousy than those with avoidance attachment. According to Nitzburg and Farber (2013) , an anxious individual may turn to social media to avoid direct interactions with his or her partner but may also face additional exertion in coping with the ambiguous information presented on social media about the partner's activities. Conversely, Marshall et al. (2013) found that individuals with an avoidant attachment may preclude checking their partners' social media. Similarly, Chang (2019) posited that anxious attachment might engender a sense of ambivalence toward partners or relationships. Such ambivalence or uncertainty may partially contribute to individuals' experiences of negative emotions, which may cumulatively influence their experiences of jealousy ( Fleuriet et al. , 2014 ).

Studies have suggested that an individual's experienced levels of jealousy and associated negative emotions may be influenced by their personality traits ( Seidman, 2019 ). Seidman (2019) found that neuroticism influenced Facebook-induced jealousy significantly but also suggested that personality may exert only a limited influence on its inception and experience. Moyano et al. (2017) found that lower levels of self-esteem and a higher individual tendency toward jealousy influence SoMJ and the possible conflict resolution strategies employed to contend with the experience. Furthermore, neuroticism ( Marshall et al. , 2013 ), along with other personality traits, such as extraversion and openness, may influence individuals' engagement with partner surveillance ( Seidman, 2019 ; Muise et al. , 2009 ). These traits may also affect individuals' experiences of other Facebook-related conflicts ( Seidman, 2019 ; Dijkstra et al. , 2013 ), such as intrusion related to partners' social media activity ( González-Rivera and Hernández-Gato, 2019 ).

4.3.2 Partners

Few studies in the SLR pool have entailed a dyadic examination of the investigated associations ( Rueda et al. , 2015 ; Muise et al. , 2014 ; Marshall et al. , 2013 ). Daspe et al. (2018) found that a partner's social media usage activity, mediated by subsequently induced jealousy, may influence the perpetration of intimate partner violence as an outcome similarly for men and women. These results contradict those of an earlier study conducted by Muise et al. (2014) , who found that women engaged in a greater degree of partner surveillance/monitoring in response to Facebook jealousy. Similarly, Marshall et al. (2013) posited that individuals' monitoring of their partners' social media activities is influenced by perceivably low levels of global commitment, daily jealousy, and a high degree of global love demonstrated by the partners. Examining the influence of technology-mediated communication platforms on the relationships of romantically partnered adolescents, Rueda et al. (2015) found that jealousy and mistrust were predominantly associated with relationships wherein multiple public (e.g., Facebook) or private (e.g., text messaging) technological platforms were used for dyadic and extra-dyadic communication. Rueda et al. (2015) posited that negative emotions, such as mistrust, may be reciprocally related to technology-enabled flirtatious behavior, which may be further escalated by the absence of tonality in such communication. This supposition synchronously supports Muise et al. 's (2009) proposition regarding the possibly cyclical nature of the relationship between social media use and induced jealousy. This may be explained by individuals' expectations of instantaneous, dyadic reciprocity of communication through technological platforms, especially social media ( Rueda et al. , 2015 ).

4.3.3 Relationship

The rapid proliferation of social media as a tool for routine or daily communication has influenced individuals' expectations of their partners, selves, and relationships ( Zandbergen and Brown, 2015 ). Nongpong and Charoensukmongkol (2016) posited that the excessive use of social media can impact different parameters of a relationship, such as perceived levels of caring, jealousy, and loneliness. Dainton and Stokes (2015) suggested that coupled with openness and positivity, individuals' motives for using social media, such as Facebook, could predict their reported levels of jealousy. Consequently, researchers have investigated relational parameters, such as commitment ( Drouin et al. , 2014 ), trust ( Carpenter, 2016 ; Macapagal et al. , 2016 ), infidelity ( Dunn and Billett, 2018 ) and length of relationship ( Demirtaş-Madran, 2018 ), in the context of social media and jealousy.

As a relational parameter, trust has been studied extensively in the context of social media and romantic relationships ( Iqbal and Jami, 2019 ; Carpenter, 2016 ; Macapagal et al. , 2016 ). Muise et al. (2009) found that lower levels of trust can increase individuals' experiences of SoMJ. In contrast, Iqbal and Jami (2019) contended that trust is a protective factor for romantic relationships, wherein it could act as a predictor of Facebook jealousy. This effect may be explained by the findings of Macapagal et al. (2016) , who suggested that social media use may lead to reduced trust between partners, as it may negatively affect individuals' focus on the relationship itself. According to Frampton and Fox (2018) , SMPs may allow individuals to digitally fact-check information pertaining to their partners' prior relationships. Their findings complement those of van Ouytsel et al. (2016) , who examined the impact of social media on the different stages of a relationship and found that individuals consider it to be a significant platform for seeking information about current or potential partners.

Marshall et al. (2013) found distinct differences in the levels of SoMJ experienced by individuals with low commitment to the relationship and low self-esteem. Drouin et al. (2014) found that lower relational commitment and attachment anxiety, mediated by Facebook jealousy, can also influence individuals' solicitation of romantic interests through social media. According to Billedo et al. (2015) , SMPs allow individuals, especially those engaged in geographically distant relationships, to display behaviors that can express commitment and loyalty, thereby assisting in relational maintenance. Seidman (2019) suggested that relational commitment may be influenced by a couple's display of affection on SMPs, such as Facebook. Such a display may also influence relationship satisfaction. Additionally, Seidman et al. (2019) found that the existence of a balance between the excessive public display of affection and private communication can improve individuals' perceptions of relational satisfaction, closeness, and security due to lower levels of experienced jealousy. However, Demirtaş-Madran (2018) found no impact of relationship length or satisfaction on Facebook jealousy, thereby suggesting that a certain divergence may exist in the emergence of these associations based on contextual, individual and/or situational factors.

4.3.4 Rivals

Our review suggests that jealousy has been primarily examined as a dyadic phenomenon, with attention being focused on the behavior of individuals who are involved in romantic relationships (e.g., Nongpong and Charoensukmongkol, 2016 ; Dijkstra et al. , 2013 ; Marshall et al. , 2013 ). Few studies have examined the role of potential or actual rivals in evoking jealousy among the studied respondents ( Dunn and Ward, 2020 ; Dunn and Billett, 2018 ; Carpenter, 2016 ). The under-investigated role of rivals, in terms of their pursuant actions, communications, and the subsequent impact on SoMJ evocation, represents a distinct lacuna in the extant knowledge.

4.3.5 Platform affordances

The affordances and features of SMPs, as well as their impact on SoMJ, have been methodically examined. For instance, prior research has associated social media use and intensity with the potential to evoke jealous responses ( Iqbal and Jami, 2019 ; Holmgren and Coyne, 2017 ; Nongpong and Charoensukmongkol, 2016 ; Fox and Moreland, 2015 ). Social media content (e.g., Dunn and Billet, 2018 ) and information (e.g., Frampton and Fox, 2018 ) have also been linked to feelings of intrusiveness, dissatisfaction and jealousy ( Fox and Moreland, 2015 ; Elphinston and Noller, 2011 ; Mod, 2010 ). For instance, Hudson et al. (2015) and van Ouytsel et al. (2016) suggest that the emoticons used by individuals in extra-dyadic communication acted as contextual cues that had a significant influence on their partners' experiences of jealousy.

Certain social media activities have also been found to impact individuals' assessments of their relational quality and satisfaction ( van Ouytsel et al. , 2016 ). However, the extant research on such activities offers a divergent view of their effects. For instance, it has been suggested that displaying one's relationship status on Facebook is akin to wearing a “digital wedding ring” ( Orosz et al. , 2015 ), which may deter rivals ( Mod, 2010 ). Conversely, other studies have suggested that online relationship statuses may be considered nonsignificant and even potentially disruptive due to their potential to induce envy among peers ( van Ouytsel et al. , 2016 ). According to Drouin et al. (2014) , individuals may also experience jealousy because of current or potential additions to their partners' friend lists on social media. van Ouytsel et al. (2016) suggested that individuals may even attempt to exert control over their partners' addition and removal of contacts from SMPs to assimilate their own feelings of uncertainty and jealousy.

Scholars have investigated the relationship between jealousy and content-sharing activities, such as dyadic photo sharing and posting of selfies, on social media. Halpern et al. (2017) posited that individuals who share a high number of selfies may not only evoke jealousy in their partners but may also face conflicts due to their continual need for idealized self-presentation and subsequent distraction from offline issues and personas. Seidman (2019) suggested that individuals who are driven by distinctive personality traits, such as neuroticism and conscientiousness, may post dyadic photographs as a measure of affection for their partners. According to van Ouytsel et al. (2016) , dyadic photographs offer a casual and subtle indicator of individuals' relationships to their peers but may not be viewed by parents or other family members as a romantic overture. While dyadic photographs may allow couples to publicly display their unity ( Seidman et al. , 2019 ), they may also induce retrospective jealousy aimed at current partners or their previous relationships, as such photographs may present an idealization of the couples and/or relationships ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ). Furthermore, individuals may be affected by the privacy-protection settings that their partners have adopted to manage communication with extra-dyadic individuals. For instance, a study by Muscanell et al. (2013) found the photo-privacy settings elicited disgust among the respondents; however, prior researchers seem not to have linked this emotion to jealousy. This suggests that the concept of SoMJ may be more subtly evolved than its current conceptualization and may even be a new form of expressing traditional romantic jealousy ( Moyano et al. , 2017 ).

4.4 Consequences

Prior research has investigated a multitude of consequences of SoMJ that relate to individuals' emotional and behavioral responses. Based on the review, we posit that these consequences may be broadly categorized as relational and psychological. Regarding the psychological effect, prior research has indicated that individuals who are afflicted by SoMJ could experience negative emotions ( Fleuriet et al. , 2014 ), such as depression ( Holmgren and Coyne, 2017 ) and feelings of inferiority ( Altakhaineh and Alnamer, 2018 ). According to Fox and Moreland (2015) , such emotions may be amplified due to an individual's propensity to engage in social comparisons. Furthermore, Dunn and Billett (2018) found that evolutionary psychology can be a foundation for understanding the direction in which such negative emotions may be vented. For instance, Holmgren and Coyne (2017) found that in a jealousy-inducing scenario, an individual's direction of comparison may affect the intensity of his or her subsequently experienced depression.

With respect to relational consequences, the review suggests that SoMJ presents a duality of connotations, which may be either positive or negative.

4.4.1 Positive connotations

Jealousy has been found to influence individuals' propensity to monitor and share passwords with their partners. This is especially prevalent among individuals with higher levels of exposure to social media and technologically mediated communications. The review suggests that such activities may be seen as coping or relational maintenance strategies ( Stewart et al. , 2014 ) to counteract SoMJ. They may be enacted to maintain relationship satisfaction and/ or avoid miscommunication, distrust, and jealousy between partners ( Bevan, 2018 ; Baker and Carreño, 2016 ; Dainton and Stokes, 2015 ; Lucero et al. , 2014 ). Furthermore, SoMJ may lead individuals to engage in dialogue with their partners regarding jealousy-inducing content or activities ( Carpenter, 2016 ; Cohen et al. , 2014 ). Such responses imply positive connotations for resolving conflicts ( Moyano et al. , 2017 ) and maintaining relational stability ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ). They may also affect individuals' perceptions of their partners' happiness ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ), as well as their relational ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ) and marital satisfaction ( Iqbal and Jami, 2019 ).

4.4.2 Negative connotations

SoMJ has been implicated in encouraging individuals to engage in negative behaviors, such as harassment ( Rueda et al. , 2015 ) and cyber abuse ( Lucero et al. , 2014 ). For example, studies have found that high levels of Facebook jealousy may lead to higher incidents of intimate partner violence ( Daspe et al. , 2018 ). Coupled with a perceived lack of caring, such jealousy may even induce individuals to terminate their relationships ( Nongpong and Charoensukmongkol, 2016 ). Studies have also implied that the online effects of SoMJ can potentially translate into offline violent behaviors, such as stalking ( Baker and Carreño, 2016 ) and physical abuse ( Brem et al. , 2015 ).

5. RQ3 . Gaps and avenues for future research

We identified theme-specific gaps in the current knowledge and correlated avenues for advancing future research; these are detailed in the following sections. The derived information was utilized to propose a comprehensive framework for guiding scholars' efforts to drive future research on SoMJ by focusing attention on methodological advancements and the less investigated associations of SoMJ.

5.1 Theoretical and methodological grounding

Regarding theoretical foundations, we posit that the majority of SoMJ research has drawn from the field of psychology and there is a gap in introspecting SoMJ from the perspectives of other allied fields, such as social behavior, information systems science and communication studies. For instance, scholars may benefit from understanding how the nature and interactivity of content posted on SMPs contribute to the development of SoMJ. Scholars may utilize theories such as media richness theory ( Daft and Lengel, 1983 ) and interactivity theory ( Voorveld et al. , 2013 ) for this purpose. Further, we argue that the conceptualization of SoMJ may benefit from its examination in light of other correlates of the dark side of social media use, such as trolling ( Baccarella et al. , 2018 ) and the fear of missing out ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ). Thus, scholars may also adopt recently developed theories on social media research, such as the honeycomb framework of social media ( Baccarella et al. , 2018 ; Talwar et al. , 2020b ).

How can theories from domains of information systems science and communication studies contribute to advancing knowledge of SoMJ as a concept?

Would the adoption of more objective, observational, and longitudinal methodological approaches make a significant contribution to improving our understanding of SoMJ as a concept?

5.2 Sociodemographic differences

In terms of the limitations of prior research, this review suggests a limited examination of the associations between SoMJ, age, culture, and ethnicity. In comparison, prior research has found significant differences between males vis-à-vis females with respect to SoMJ experiences. However, future researchers may extend the current scope of knowledge regarding the influence of gender on SoMJ by examining whether males and females experience different intensities of emotions associated with jealousy, such as anger or sadness. This could also assist in refining the conceptualization of SoMJ as a distinct phenomenon.

It is difficult to present generalizations regarding age-related differences with respect to SoMJ because the extant literature has focused primarily on young or emerging adults (aged 18–29 years; see Table 1 ). Future research may focus on understanding this phenomenon across different age groups, such as adolescent, adult, and mature SMP users. For instance, studies could be directed toward explicating potential differences in the acceptable thresholds for SMP use behavior for adolescents, young adults, and adults. Future research may also be geared toward understanding the association between SMP use and the experience of platonic forms of SoMJ directed against peers or family members. Scholars may also attempt to use the concept of chronemics ( Fleuriet et al. , 2014 ) to understand whether SoMJ is associated with time spent by different age groups on various activities, such as photo sharing or surveilling partners' activities.

How do different age- and gender-based cohorts experience the various emotions associated with SoMJ?

How do different age-based cohorts define the acceptability thresholds for social media behavior that may induce jealousy?

How are platonic forms of SoMJ induced among different age groups?

How do cultural and ethnic parameters, such as personal values, affect the factors associated with social media use and induced jealousy?

5.3 The antecedents of SoMJ

Distinct gaps can be delineated in the extant body of knowledge in terms of the antecedents of SoMJ, which are discussed below.

5.3.1 Individuals

How do an individual's personality traits affect the relational maintenance strategies that he or she may adopt to resolve SoMJ?

How do an individual's goals and motives for SMP use influence his or her experience of SoMJ?

How strongly does past experience influence an individual's experience with jealousy in a current relationship?

5.3.2 Partners

Do the personality traits of both individuals in a relationship interact in any way to influence their experiences of SoMJ?

What, if any, are the differences in how both partners in the relationship respond to SoMJ?

How do partners react behaviorally and/or emotionally to their significant others' experiences of SoMJ?

How does interpersonal communication between an individual and his or her partner impact the conflict resolution or coping mechanisms that are adopted as a behavioral response to SoMJ?

5.3.3 Rivals

How do the actions of the perceived rival(s) influence SoMJ and its outcomes?

What are the individual's behavioral and emotional responses to his or her perceived SMP-based rivals?

5.3.4 Relationship

A relatively less investigated relational parameter is infidelity and its effect on SoMJ. Researchers have posited that a link exists between individuals' past experiences of infidelity and jealousy induced by the potential threat of extra-dyadic infidelity as a result of their partners' social media use ( Seidman, 2019 ; Utz et al. , 2015 ; Zandbergen and Brown, 2015 ; Clayton et al. , 2013 ). Nonetheless, few empirical investigations into these associations have been undertaken. For instance, Zandbergen and Brown (2015) found that culture and gender were potential predictors of an individual's reported jealousy due to sexual and emotional infidelity on social media, respectively. Similarly, Dunn and Billett (2018) found that infidelity affected individuals' reported distress and jealousy dissimilarly for males and females. This dissimilarity was also affected by the direction of social media communication. Males reported a higher level of distress upon discovering messages sent by their partners to rivals that indicated sexual infidelity compared to females who indicated a higher level of distress in response to messages received by their partners (from female rivals) than those sent by their (male) partners ( Dunn and Billett, 2018 ).

Additionally, prior studies have suggested that relational expectations may differ between age or culture-based cohorts, which may translate into different thresholds for acceptable norms of relational maintenance behavior on social media. For instance, Lucero et al. (2014) found that young adults considered password sharing and monitoring as a sign of trust and as a protective measure against infidelity. Similarly, Bevan (2018) suggested that password sharing was a multidimensional construct with the potential to trigger both SoMJ and relational satisfaction. Rueda et al. (2015) suggested that such behaviors require further investigation to understand how they may encourage the formation of trust between partners.

However, Demirtaş-Madran (2018) posited that there is still a limited understanding of how relational parameters, such as satisfaction, may interact with forms of SoMJ, such as Facebook jealousy.

How does social media-related infidelity in previous/current relationships impact an individual's experience of SoMJ and his or her future social media usage?

How do an individual's sexual orientation and type of relationship influence SoMJ and the associated thresholds of acceptable social media behavior?

What is the impact of relational commitment on evoked emotions, such as anger or sadness, when an individual is confronted with jealousy-inducing social media activities?

Is there a positive influence of newer forms of potential dyadic social media activities, such as online gaming, on tempering SoMJ?

5.3.5 Platform affordances

Although the SLR suggests that 68.9% of the reviewed articles considered Facebook as the platform for investigating SoMJ (see Table 1 ), jealousy may also be experienced by the users of other SMPs (e.g., Instagram or Snapchat). Thus, we argue for the need to reexamine SoMJ from a more generalized and holistic perspective. For instance, future research may examine the forms of emergent emotions associated with jealousy across other platforms, such as Instagram and Snapchat, to develop a more refined understanding of SoMJ. We elucidate a significant gap in addressing how individuals may perceive flirtatious behavior on SMPs. Thus far, research has mainly concentrated on content such as emoticons ( Hudson et al. , 2015 ) and photographs ( Frampton and Fox, 2018 ). We argue for the need to delineate Internet or social media-oriented communication as a distinct linguistic form and to investigate other contextual, jealousy-inducing cues in this environment.

Additionally, despite the extensive investigation of features of SMPs and their impact on inducing jealousy, the extant literature in this field has focused primarily on Facebook as a platform. A limited number of studies have investigated the potentially jealousy-inducing effect of other SMPs, such as Snapchat ( Dunn and Ward, 2020 ; Utz et al. , 2015 ), or considered the impact of Internet and ICT platforms from a holistic perspective ( Rueda et al. , 2015 ; Dijkstra et al. , 2013 ). These studies have indicated differential usage motives, jealousy-inducing content, and the intensity of induced jealousy for different SMPs ( Dunn and Billett, 2018 ; Utz et al. , 2015 ). The supposition that SMP affordances may evoke SoMJ is supported by the study of Cohen et al. (2014) , which found perceived intimacy or secrecy of a message (message exclusivity) to influence negative emotions and the potential for creating conflict.

How, if at all, does SoMJ emerge across different SMPs, such as Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat?

How do contextual or linguistic cues differ in terms of the potentially flirtatious behavior exhibited on SMPs vis-à-vis offline interaction?

How do different platform affordances, such as content or activities, affect the intensity or level of SoMJ and the associated emotions experienced by two romantically engaged individuals?

5.4 The consequences of SoMJ

The extant knowledge is limited regarding the examination of how the emotions associated with SoMJ, such as anger, sadness and betrayal, may be directed at the self, partner, or rival. There is a need to further investigate the direction and intensity of the emotions that are felt by individuals experiencing SoMJ. Such an understanding may assist researchers in elucidating the mechanism of effect through which jealousy may affect the psychological state of the partner and/or rival. However, the review also suggests that with regard to married (or engaged) individuals, the association between social media and jealousy is under-researched. In fact, previous studies have considered relationship length as a control variable ( Seidman, 2019 ; Seidman et al. , 2019 ; Halpern et al. , 2017 ), and relatively few studies have investigated commitment as a predictor ( Drouin et al. , 2014 ; Marshall et al. , 2013 ). We posit the need for a more detailed assessment of the intensity and length of commitment with regards to SoMJ. For instance, the influence of relationship length and commitment on SoMJ may be explored for individuals who are married, engaged, or in a long-term civil union.

Based on the discussions of the negative connotations of SoMJ, we argue that researchers need to understand the prevalence of such negative effects in both online and offline contexts. We also posit the need to understand the mechanisms that individuals use to cope with such negative effects, especially in the cases in which their emotions may trigger aggressive or violent responses. Additionally, Frampton and Fox (2018) discussed the influence of retrospective jealousy on individuals. Based on their findings, we question whether SoMJ may also cause individuals to showcase negative behaviors toward their previous partners. Further, the SLR suggests a distinct gap in the current knowledge regarding the continual impact, if any, of jealousy on individual behavior after the dissolution of a relationship. It may be interesting to understand whether such impacts are connected to other correlates of the dark side of social media, such as malicious gossiping, trolling, and cyberstalking. The question of whether individuals' personal values influence their actions may also be significant.

What is the mechanism of effect through which the negative emotions (level and intensity) associated with SoMJ may be directed toward the self, partners, and perceived (or actual) rivals?

How do the length and status of relational commitment affect the experience of SoMJ among individuals who are married, engaged or dating casually?

What is the prevalent influence of SoMJ on offline negative behaviors, such as monitoring or stalking?

How does SoMJ influence an individual's post-relationship dissolution behavioral response?

How, if at all, do SMPs affect an individual's experience of platonic forms (familial and peer) of jealousy?

5.5 The SoMJ framework: a theoretical comprehension

The SLR highlights the complex nature of the relationships governing the concept of SoMJ, which transcends the boundaries and intricacies of offline relationships among individuals to encompass the influence of SMP affordances and perceived rivals in the digital environment. Based on the gaps and future agendas detailed in the previous sections, we propose the SoMJ framework ( Figure 3 ), which emphasizes the need to adopt more sophisticated research approaches to advance conceptual knowledge of SoMJ and investigate the hitherto under-explored associations of SoMJ with variables related to (1) SMPs, (2) incumbent actors (the individual, partner and rival) and (3) relational parameters.

Conceptual advancement is the foremost SoMJ-related issue that researchers need to address. It would be beneficial to explore whether SoMJ is a new form of jealousy that has been relegated to the SMP environs or a corollary to relational activities, such as partner monitoring. The SLR indicates the need to explore the emotional components of SoMJ and its correlation with non-romantic forms of jealousy, such as peer and familial jealousy. To resolve the existing inconsistencies in the conceptualization of SoMJ, future research may be directed toward examining whether these forms and components of SoMJ differ from its traditional characterization.

Methodological improvements in conjunction with conceptual advancement are needed to generate more definitive and generalizable insights into SoMJ as a distinct phenomenon. For instance, a larger and more diverse respondent base may be studied to investigate the emergence of SoMJ. In addition, individuals with varied sexual orientations, ages, relational statuses, and cultural backgrounds, should be examined over longer periods to understand how SoMJ emerges and evolves. Researchers may gather objective data through more mixed method–based research designs to garner deeper and more quantitatively verifiable insights into the interactive association between SMPs and SoMJ.

Specific SMP affordances , such as particular linguistic cues or cross-platform features, and their correlations with SoMJ need to be researched. Further, scholars may examine whether and how SoMJ correlates with issues related to the dark side of social media, such as the fear of missing out, cyberstalking, and social comparison. These issues may make individuals more pliable and vulnerable to influence by acontextual or ambiguous content that is shared on SMPs. They should therefore be investigated in the context of SoMJ.

Incumbent actors – that is, the individual, partner and perceived rival – should be examined to explicate their roles in the development and differential experiences of SoMJ. The role of the rival is significantly under-explored in SoMJ research. Scholars may focus on exploring SMP actions or the intensity of pursuit of actual/perceived rivals toward individuals, as well as the emotions directed toward such rivals by individuals and their partners. It is also imperative to examine the issues that may influence an individual's psychological or emotional states, such as usage motives, past experiences and personal values. In addition, researchers should explore whether individuals' experiences of SoMJ are affected by their partners' SMP activities, personalities, or behavioral/emotional responses, and vice versa.

Relational parameters may also be explored by future scholars, especially through dyadic investigations. For example, scholars may benefit from understanding individuals' specific purposes for using SMPs, especially if they are being utilized as tracking or monitoring platforms for relational surveillance. Concurrently, we posit the need to investigate whether relational maintenance behaviors, such as monitoring and interpersonal communication, share a temporally reciprocal or symbiotic relationship ( Carpenter, 2016 ; Muise et al. , 2009 ).

Finally, researchers may benefit from understanding the role of moderator variables in influencing SoMJ associations . Based on the SLR, we posit the potential moderating influence of cultural, ethnic, and sociodemographic factors on the creation and effect of SoMJ. We further urge scholars to investigate other variables that may indirectly affect SoMJ in a moderating or mediating capacity.

6. Conclusions, implications and limitations

This study provides an exhaustive assessment of the areas on which the extant research has focused regarding the association between jealousy and social media. This assessment has been based on three RQs. The aim of the first was to understand the profile of the research on social media and jealousy. This question was answered through a discussion of publication trends, top authors, journals, and the geographic scope of prior studies. The keywords of select studies were then analyzed to understand the focal themes of the research conducted in this field. The second RQ pertained to the delineation of the antecedents and consequences of SoMJ. In response to this question, the emergent themes and the contextual lenses of prior investigations into SoMJ have been explicated, wherein two thematic classifications detailed the antecedents and consequences identified by prior research. Finally, the third research question aimed to understand the gaps in the existing research and to explicate potential agendas that could advance the current understanding of this domain. Specific gaps and future research agendas were then detailed for each identified theme, as summarized in Table 2 . Additionally, these agendas have been used to form an integrated framework that may assist researchers in understanding SoMJ. The findings have significant implications for academicians and clinicians who are engaged in this domain.

6.1 Theoretical implications

This study has five primary implications for the theoretical advancement of research on SoMJ. First, it makes a significant contribution to the assimilation and analysis of the fragmented knowledge regarding the associations of SoMJ that have been empirically investigated in prior research. In presenting a comprehensive overview of the extant literature, this study creates a singular platform for understanding the intellectual structure of SoMJ-related research.

Second, the SLR explicates the multidimensional nature of SoMJ by delineating its association with SMP affordances and a triad of actors (partner, individual and rival). The study further speculates on the possibility of this concept being a correlate of the dark side of social media. It suggests that there is a need to understand SoMJ's associations with other correlates of the dark side of social media that influence individual states and responses in terms of both emotions and behaviors. This could advance the current knowledge of the operational mechanism of effect through which SoMJ impacts the individual psyche.

Third, the SLR draws attention to the current characterization of jealousy in the context of social media. The findings suggest that there is a need to examine the possible platonic and familial forms of jealousy that may also be induced among SMP users. Thus, this study makes a significant contribution by identifying potential avenues to expound upon the conceptual boundaries of SoMJ.

Fourth, by elucidating the extant knowledge gaps, the findings present several subthemes and topics that require further scholarly attention. Future researchers can use these topics and subthemes to construct and validate more advanced frameworks to examine SoMJ holistically. The findings also suggest that there is a need for methodological improvements, and this study can provide researchers with a point of navigation for adopting novel research designs and approaches.

The fifth contribution is the proposed framework, which details the under-investigated associations of SoMJ. This framework provides a foundation to advance knowledge of the mechanism of effect through which SMPs may induce jealousy among users. We underscore the need to incorporate the perspective of linguistics into this field of research as social media communication may have distinctive patterns and connotations of communication.

6.2 Practical implications

This study has four significant implications for the users, designers, and managers of SMPs. The findings may also be valuable for clinicians, such as psychologists, who work with individuals and couples who are dealing with the experiences and consequences of SoMJ. First, an important finding for SMP designers and managers is that SoMJ should not be considered a solely individual-level issue; rather, it is important to scrutinize the role of users' personal social networks in relation to SoMJ. For example, the use of text mining or sentiment analysis of social media activity and shared content can be helpful in identifying individuals who are potentially afflicted by jealousy or its consequences.