- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Using Evidence: Synthesis

Synthesis video playlist.

Note that these videos were created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

Basics of Synthesis

As you incorporate published writing into your own writing, you should aim for synthesis of the material.

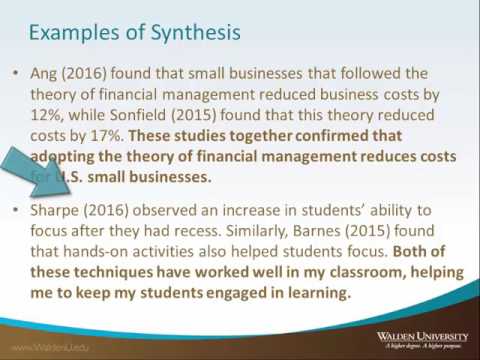

Synthesizing requires critical reading and thinking in order to compare different material, highlighting similarities, differences, and connections. When writers synthesize successfully, they present new ideas based on interpretations of other evidence or arguments. You can also think of synthesis as an extension of—or a more complicated form of—analysis. One main difference is that synthesis involves multiple sources, while analysis often focuses on one source.

Conceptually, it can be helpful to think about synthesis existing at both the local (or paragraph) level and the global (or paper) level.

Local Synthesis

Local synthesis occurs at the paragraph level when writers connect individual pieces of evidence from multiple sources to support a paragraph’s main idea and advance a paper’s thesis statement. A common example in academic writing is a scholarly paragraph that includes a main idea, evidence from multiple sources, and analysis of those multiple sources together.

Global Synthesis

Global synthesis occurs at the paper (or, sometimes, section) level when writers connect ideas across paragraphs or sections to create a new narrative whole. A literature review , which can either stand alone or be a section/chapter within a capstone, is a common example of a place where global synthesis is necessary. However, in almost all academic writing, global synthesis is created by and sometimes referred to as good cohesion and flow.

Synthesis in Literature Reviews

While any types of scholarly writing can include synthesis, it is most often discussed in the context of literature reviews. Visit our literature review pages for more information about synthesis in literature reviews.

Related Webinars

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Analysis

- Next Page: Citing Sources Properly

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Mapping a synthesis essay

When asked to write a synthesis essay, many students question the word “synthesis.” What does it mean to synthesize? Well, the dictionary tells us that synthesis is the combination of ideas to form a theory; the thesaurus provides synonyms such as fusion, blend, and creation. So ultimately, you are creating a combination of what your sources are conversing about (subject X) and how you have rearranged what is being said to create a new direction for that subject. This quick outline should get you well on your way to synthesizing.

Read your sources carefully and annotate as you go.

- Read through once for a general understanding of the source.

- Use a highlighter to call your attention to specific passages that you feel are key to this issue.

- Make summary notes as you go, so you remember why you highlighted those passages.

Analyze the data you are getting.

- Ask yourself what the author’s claim is–make note of it.

- When the author brings in evidence, what is it? How does this evidence support the claim?

- Note any common beliefs or assumptions embedded in the author’s use of evidence and claims.

What are sources “saying” to each other?

- When you can summarize what each source is saying, then you can take a step back and ask yourself: Is there a pattern; how are these sources communicating/responding to each other?

- Example: If The New York Times is speaking on gun control, they may say “X.” Later, Fox News may also be talking about gun control, but they are saying “Y.” Both are discussing gun control as the “conversation,” just in different ways and at different times.

- Example: So, when you arrange the above example’s conversation, you can see that these sources are talking about “X” and “Y,” in terms of gun control, but no one seems to be specifying about “Z”. “Z” will be the gap in the conversation (you can suggest it as a new research area, new point to consider, etc.).

Figure out what your particular stand is on this issue.

- After seeing where others stand, where do you stand?

- If you agree or disagree, why?

- If you agree, but not quite, what could be done differently? How could you make a position that might be a bit different than what other authors are saying?

Take a moment to consider how others in the conversation might respond to your position.

- Why would article X’s author argue with you?

- How would this author argue with you?

- If the author would agree with you, same thing –how and why?

After this imaginary conversation with your sources, you should be getting an idea about your thesis and where it fits into the “conversation” that your sources are having.

- Research about topic A is currently indicating…

- Maybe a lot of people are saying X about topic A, but you have found research that is actually indicating Y as the real problem of topic A, so you say that new research needs to be done…

Work on incorporating those “conversations” you just had into your essay.

- Although many researchers are indicating “X,” in discussions involving topic A, many of those research methods are faulty in that…

- When researchers in the field of topic A argue with researchers studying topic B, I am seeing that these two fields are actually linked in that…

- Aside from topic A, some researchers are finding a trend that (topic B) is actually more…

- In consideration of both topics A & B, I am led to believe that there is a vital resource that hasn’t been considered…

When incorporating conversations as you write, argue your thesis claim.

- Many who deal with topic A take a position similar to mine in that…; however, I would argue that new research needs to be done in the field of topic B.

- Although some who argue about topic A would oppose my position on developing new research in this field, here is why I still uphold its legitimacy…

- Only a few researchers offer a slightly different perspective from topic A, and one perspective that I would call attention to is...

- When sources A and B were doing the specific types of studies on subject X, there were two different research methods: method 1 and method 2. Of these methods, there are the following common themes… (and) the usual points of disagreements are… which justifies the need for new research in…

The successful synthesis essay will show readers how you have reasoned about the topic at hand by taking into account the sources critically and creating a work that draws conversations with the sources into your own thinking.

Contributor: Derrian Goebel

Module 8: Writing Workshop—Analysis and Synthesis

Putting it together: writing workshop—analysis and synthesis.

Now that you’ve worked through some more thorough definitions and examples of analysis, inference, and synthesis, you will be better positioned both to recognize these strategies in the work of others and to beneficially employ them in your own thinking and writing.

In academic writing, it’s thorough, rigorously analytical work that stands out and that demonstrates credible–and credit-worthy–learning. Incorporating elements of inference and synthesis into your essays and presentations will go a long way toward strengthening your work.

- Image of woman biting pencil. Authored by : Jan Vasek. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/laptop-woman-education-study-young-3087585/ . License : Other . License Terms : https://pixabay.com/service/terms/#license

The story behind the synthesis: writing an effective introduction to your scoping review

- The Writer’s Craft

- Open access

- Published: 12 August 2022

- Volume 11 , pages 289–294, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lorelei Lingard ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4150-3355 1 &

- Heather Colquhoun 2

8156 Accesses

27 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the Writer’s Craft section we offer simple tips to improve your writing in one of three areas: Energy, Clarity and Persuasiveness. Each entry focuses on a key writing feature or strategy, illustrates how it commonly goes wrong, teaches the grammatical underpinnings necessary to understand it and offers suggestions to wield it effectively. We encourage readers to share comments on or suggestions for this section on Twitter, using the hashtag: #how’syourwriting?

In a recent writing workshop, a participant was applying the “mapping the gap” heuristic in the introduction of his paper. Mapping the gap is a strategy for writing a succinct, compelling literature review in a paper’s Introduction: the writer briefly and selectively summarizes what’s known in order to outline the white space—the gap—that the research fills [ 1 ]. But this writer had done a scoping review, and he was struggling to make the heuristic fit. “ How do I summarize what is already known, ” he said, “ without giving away what my scoping review found? The gap is one of my results, isn’t it ?”

Good question. And for anyone writing or giving feedback on scoping reviews, a rather pressing one. This form of knowledge synthesis is proliferating in health research generally and health professions education (HPE) research specifically, and a recent review suggests that published scoping review manuscripts in HPE often lack a strong introductory rationale for the work [ 2 ]. This may be in part because guidance for writers regarding this section of a scoping review is sorely lacking. The problem isn’t a lack of frameworks or guidelines for conducting and reporting scoping reviews: these are available in abundance, with ongoing updates and refinements [ 3 , 4 ]. But in all cases the emphasis is predominantly on methods: the idea of the scoping review as a story to be told is missing.

Two main sources of scoping review guidance illustrate this point. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for designing scoping reviews [ 4 ] give more attention to title than introduction: the advice is mainly that the latter “should be comprehensive and should cover the main elements of the topic, important definitions, and the existing knowledge in the field” (11.3.4). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [ 5 ] focuses significantly more attention on Methods and Results than on Introductory framing. Writers find only two items to guide them: we are to “describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known… and explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach”; and we should provide “an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context)” ( p 469). However, as my workshop participant pointed out, the devil is in the details. Where’s the line between describing a rationale in “context of what is already known” and giving away your results, or even negating the value of doing a scoping review in the first place? How much, and which, literature needs to be introduced to establish the “key elements… population or participants, concepts, and context” for the review questions and objectives? In a nutshell, how does the author set up the story of a scoping review? To date, the scoping review guidance literature privileges study—and ignores story. But every good manuscript needs both.

In this Writer’s Craft, we offer writers advice for crafting a clear, compelling story in the Introduction of their scoping review paper. This advice is relevant for any scoping review, thus our illustrations come from a variety of fields.

Articulate the problem/gap/hook

Scoping reviews are a synthesis of knowledge. Therefore, the introduction’s main purpose is to offer an argument for why we need a synthesis of the knowledge on a particular concept. The Problem-Gap-Hook heuristic [ 6 ] can help efficiently lay out this argument.

Let’s begin with the Gap, as it is the same for every scoping review: the lack of synthesis of existing literature. This should be signaled clearly with language such as “Amid such debates, the scholarly community lacks a large-scale, systematic overview of the [arts & humanities] literature” [ 7 ] ( p 1213) or “there is little evidence on how the Bangladeshi community gain access to diabetes-related information and services” [ 8 ] ( p 157), or “one area of medical education research that has not yet been systematically examined is family medicine” [ 9 ]( p 1). It is possible to leave the Gap unstated; readers will be able to infer it as it is similar across scoping reviews. However, making it explicit offers the opportunity to characterize it precisely as Maggio et al. [ 2 ] do in their scoping review of HPE scoping reviews ( p 690):

the extant research on scoping reviews provides limited information about their nature, including how they are conducted, if they are funded, or why medical educators decide to undertake this type of knowledge synthesis in the first place. This lack of direct insight makes it difficult to know where the field stands and may hamper attempts to take evidence-informed steps to improve the conduct, reporting and utility of scoping reviews in medical education.

Explicitly naming and characterizing the gap is particularly important in a scoping review of scoping reviews, to convince the reader that, amid a sea of reviews, we need another. As scoping reviews proliferate, so too will scoping reviews of scoping reviews, making a strongly characterized gap an essential ingredient of these stories.

While the Gap for a scoping review is invariably some lack of synthesis, this in itself does not justify doing a scoping review. Lots of literature remains unsynthesized; why does it matter in this case? Writers must articulate the Problem that arises because of the lack of synthesis. It is not sufficient to say, for instance, that “Hundreds of knowledge translation (KT) theories exist across a broad range of paradigms including organizational theory, learning theory, and social cognitive theory, but they have yet to be synthesized”. You must make explicit the problem created by an abundance of unsynthesized theoretical KT literature: something like, “Scholars struggle to use KT theory effectively, faced with hundreds of possibilities and no synthesis to guide them”. Look at published scoping reviews to see how other authors express the problem: it might be that the field lacks conceptual consensus, or practices are inconsistent, or controversies remain unresolved, or understanding is inhibited by implicit blind spots, or research is proceeding without programmatic direction. For example, Van Schalkwyk et al. [ 10 ] conducted their scoping review of transformative learning as pedagogy because they realized that “understanding of the construct differed amongst us and lacked a clear theoretically grounded comprehension” ( p 538); Sebok-Syer et al. [ 11 ] argued that a scoping review was needed around measuring interdependence because “variability in both terminology and approaches among researchers may contribute to assessment challenges” ( p 1124); and Young et al. [ 12 ] declared that, although it has been much studied, “little consensus exists regarding the definition of clinical reasoning” ( p 2). Reading critically can help expand your repertoire of phrases for this key part of your Introduction.

The Hook is the ‘so what’ of your scoping review—the statement of why it matters to solve the Problem you’ve identified. The Hook can be expressed either in terms of possibility (e.g., “With a synthesis, we will be able to …”) or caution (e.g., “Without a synthesis, we risk …”). A good scoping review Hook focuses on what the results of the review will be used for, and writers should aim for specific examples of value. Saying that your review will “be useful to a broad audience of educators” is too vague. Be more precise and persuasive. Howell et al. [ 13 ] express “ an urgent need for a guiding taxonomy of core PRO domains and dimensions in cancer” ( p 77); Gottlieb et al. [ 14 ] argue that “ Given the profound impact of burnout on medicine, understanding imposter syndrome within the context of physicians and physicians in training is critical ”( p 117); Maggio et al. [ 2 ] set out to “ identify areas for improvement in the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews in medical education, thereby helping to ensure that those produced are relevant to and practical” ( p 690); and Young et al. [ 12 ] assert that “a careful mapping of the concept of clinical reasoning across professions is necessary to support both profession-specific and interprofessional learning, assessment, and research” ( p 2). A negative hook, with its articulation of problems or negative impacts associated with not having synthesized the literature, may be particularly effective. If we convert Young et al.’s hook to negative, we get something like “without this careful mapping, learning, assessment and research cannot advance coherently ”. Which do you find more compelling?

Structure the story

The Problem, Gap and Hook are important, but they are only three of the sentences in your Introduction. What goes in the other sentences, and how should you organize them?

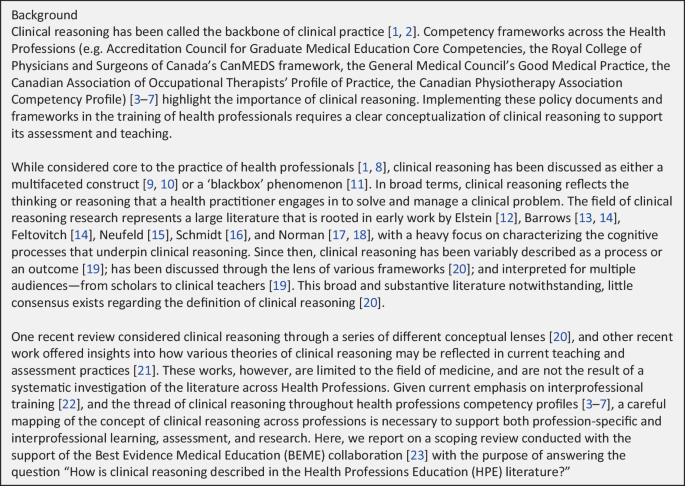

According to scoping review guidelines [ 4 , 5 ], the introductory literature review of your paper must do three things: 1) provide relevant details about the “population or participants, concepts, and context” (PCC); 2) establish that there is sufficient literature to warrant a review; and 3) acknowledge any pre-existing reviews and distinguish them from yours. Let’s walk through each of these, unpacking Young et al.’s three-paragraph scoping review introduction as a primary illustration and using additional examples to help you build your Introduction repertoire (Fig. 1 ).

An effective scoping review Introduction, from Young et al. [ 12 ]

Use the PCC framework

According to Peters et al. [ 15 ], “use of the PCC mnemonic clearly identifies the focus and context of a review” (p2122). We like to think of it as orienting the reader to the setting and main characters of your story. Young et al. establish the PCC in their first paragraph: they describe the population/participants (health professionals), the main concept (clinical reasoning), and the context (health professions education, including both policy frameworks and teaching/assessment activities). Many scoping review introductions take multiple paragraphs to establish the PCC, starting more generally and then narrowing. This inverted triangle is common in scoping review introductions: for example, O’Brien et al.’s [ 16 ] two-paragraph introduction which begins with a paragraph describing the broader context of HIV, followed by a paragraph narrowing in on the concept of rehabilitation in HIV. An inverted triangle introduction doesn’t need to be long: in three paragraphs Maggio et al.’s [ 2 ] introduction sketches the rise of scoping reviews in medical education, narrows to scoping review methods and then narrows further to methodological and reporting concerns. By contrast, Alam et al.’s [ 8 ] scoping review opens with a protracted inverted triangle which traverses concepts of diabetes, health access, and minority groups before finally coming to its focus in the 10th paragraph of the literature review: British Bangladeshi’s access to diabetes-related healthcare information and services. Particularly if your paper is a conventional length for a health research journal (3000–4000 words), this is a long wait for the appearance of the main character of your scoping review story. Aim for a 3–4 paragraph introduction, use the inverted triangle structure as an organizing logic, and choose stress positions for key sentences (like Young et al.’s problem sentence that concludes the second paragraph).

Establish that the literature can support a scoping review

There is no magic number of studies that constitutes a threshold for scoping, so the writer must convince the reader that the literature is sufficient. In their second introductory paragraph, Young et al. make this argument. The first sentence notes the “variety” of ways the concept has been discussed; the third sentence characterizes the literature as “large” with an “early” emphasis on “cognitive processes”; the fourth notes that the concept has been approached as both “process” and “outcome”, that it has been variously framed and “interpreted for multiple audiences”. Notice that the detailed content of the literature is not given away: the map is sketched only enough to show its “broad and substantive” contours and set up the problem of “little consensus … regarding the definition of clinical reasoning”. The Young et al. example establishes that there is an abundance of literature for scoping. But that’s not always the case. If you’ve scoped a limited literature, your argument must acknowledge that the literature is limited while explaining why it is still worthwhile to review. For example, O’Brien et al.’s [ 16 ] introduction acknowledges that there is only a “small amount of evidence” and that “relatively little research focuses on rehabilitation in HIV care” ( p 449). Explaining that “this field is still emerging”, they position the review as “an initial step” aimed at “understanding the research priorities” ( p 449). And, reflecting the limited literature, they also employ key informant consultation to help identify key research priorities and gaps in the field.

Acknowledge previous reviews

If yours is the first review of the concept with reference to the particular context and participants you’ve outlined, you can simply say so, as Shorey et al. [ 17 ] do with their assertion that “there are no existing reviews that have consolidated evidence from studies across all medical faculties” ( p 767). However, if the literature has already been reviewed, your effort to justify the need for your review needs a bit more attention. Young et al.’s third introductory paragraph recognizes the existence of other reviews and conceptual analyses of clinical reasoning, points out their “limited” focus on medicine, and argues for the need for a synthesis of “literature across Health Professions”. This justification is followed by a positive Hook that labels what’s distinctive about their review: “a careful mapping of the concept of clinical reasoning across professions is necessary to support both profession-specific and interprofessional learning, assessment, and research.”

How you handle previous reviews in your introduction is particularly important in scoping reviews of scoping reviews. The third paragraph of Maggio et al.’s [ 2 ] Introduction makes space for their review by pointing explicitly to “the rise” in scoping reviews in medical education, acknowledging the presence and value of “discipline-specific and cross-disciplinary scoping reviews of scoping reviews”, and arguing that existing reviews are either “several years old” or “focused solely” on one discipline ( p 690). By asserting that “the multi-disciplinary nature of medical education research” suggests “differences [that] warranted further exploration” ( p 690), they claim a unique space for their own work amid what the reader may see as a crowded synthesis landscape. Similarly, Howell et al. [ 13 ] acknowledge that “our work built on earlier studies, but unlike earlier reviews we used formal methods to gain consensus on core PRO domains and related subdimensions” ( p 77), and Chan et al. [ 18 ] recognize that “there have been some reviews about the use of social media for education” but explain that “none have sought to fully encompass the breadth of how these technologies have affected the full spectrum of education” ( p 21). As these examples show, the acknowledgement of existing reviews must be accompanied by a clear statement of what your review adds, which should be tied to the problem you’ve outlined.

Create alignment

The final ingredient of an effective introduction is alignment among the “rationale”, “research question”, and “objectives” of the review [ 3 ]. These terms are used variably in scoping reviews, reporting guidelines, and reviews of scoping reviews. For our purposes, we use “rationale” to mean why we’ve done a scoping review—what problem does it address? (This is also sometimes referred to as “purpose” in published scoping reviews.) We use “research question” to mean the specific question guiding the search, and we use “objectives” synonymously with “sub-questions” to represent specific foci of inquiry.

Let’s analyze an example where alignment is achieved. Versteeg et al. [ 19 ] briefly summarize the literature and land on this statement of the problem: “Overall, the broad range of terms associated with spaced learning, the multiple definitions and variety of applications used in HPE can hinder the operationalisation of spaced learning” ( p 206). With this problem in mind, their rationale is “to investigate how spaced learning is defined and applied across HPE contexts”, which they phrase as an overarching question: “How is spaced learning defined and applied in HPE?” ( p 206). They then articulate “specific research questions: (RQ1A) Which concepts are used to define spaced learning and associated terms? (RQ1B) To what extent do these terms show conceptual overlap? (RQ2) Which theoretical frameworks are used to frame spaced learning? (RQ3) Which spacing formats are utilised in spaced learning research?” ( p 206) This example is well-aligned: “definition and application of spaced learning” remains consistently in focus, and refinements such as “conceptual overlap” and “theoretical frameworks” are further and logical specifications of the overall focus. This example illustrates Levac et al.’s [ 3 ] advice to balance broad research questions with clearly articulated scope of the inquiry and link the rationale to the research questions.

Alignment seems straightforward when it is done well, but it can be tricky. Maggio et al. [ 2 ] noted room for improvement in the alignment between rationales and research questions in almost 65% of HPE scoping reviews. Echoing Levac et al. [ 3 ], they suspected that one reason for this misalignment is “rationales that are applicable broadly to a variety of knowledge synthesis methodologies and not necessarily specific to scoping reviews” ( p 695). One strategy for testing your own alignment is to explain why you selected scoping review methodology: as Maggio et al. suggest, tell the reader “what factors influenced [the] decision to undertake a scoping review (e.g., the nature of the literature, the intricacies of the topic, the expertise of their research team, and/or their personal needs such as a graduate student familiarising herself with a topic)” ( p 695). Another reason for misalignment is a research question that is too generic and not balanced by clearly articulated objectives that delimit the scope of the inquiry. For example, a generic question like “what is known about medical tourism” cannot support a strong search strategy: the scope needs to be tightened (e.g., medical tourism by Canadians for surgical procedures) in order to focus the work. Finally, even when you try to “balance” a broad question with focused objectives or sub-questions as Levac et al. have advised, be careful that your sub-questions still align with the rationale. If they feel more like detours than logical specifications of the overall focus, then you have a misalignment. For example, a sub-question about the ethics of medical tourism by Canadians for surgical procedures might feel misaligned if the rationale for the scoping review does not have any ethical flavour. Remember: alignment (or its lack) is judged by how well the rationale, question and sub-questions fit the overall story you’re laying out in the introduction—how coherently do they follow from your Problem, Gap and Hook?

A final note on alignment as it relates to the consultation exercise. The consultation is a unique strength of the scoping review. However, differing points of view have been expressed on its optional [ 20 ] or essential [ 3 ] nature, and it does not appear in the PRISMA-ScR [ 5 ] reporting guideline which can leave writers unsure about its role. As you frame the story for a review that included consultation, readers should see this step as aligned and necessary. For instance, you may anticipate a limited literature for scoping and thus seek insights from stakeholder consultation as primary data [ 15 ]. You may have scoped an ample literature but identified missing perspectives or voices that you explored using consultation [ 7 ]. Or you may use stakeholders to contextualize review findings in order to fully address the question being asked, as in Maggio et al.’s [ 2 ] consultation with “seven stakeholders to understand if and in what ways our findings resonated with their experiences conducting scoping reviews” ( p 691). The consultation exercise will be described in your methods, but the introduction should set the reader up to expect it. For example, O’Brien et al.’s [ 16 ] rationale is to “advance policy and practice for people living with HIV” ( p 449), which aligns well with their decision to consult with people with HIV to contextualize the literature and create a patient partner-informed research agenda.

Every scoping review manuscript needs a story to frame the study. This Writer’s Craft offers strategies for telling this story in your introduction (Tab. 1 ). Use the Problem/Gap/Hook heuristic to establish why we need a synthesis in the first place. Structure the story so that it introduces setting and main characters, establishes that there is sufficient literature for a review, and acknowledges pre-existing reviews. Align the rationale for the work, the research question and the specific sub-questions or objectives—there should be no jarring detours from the storyline. Finally, keep it short: three or four paragraphs should suffice. Your introduction doesn’t need to detail the specifics; it should just sketch the curvature. And don’t worry about ‘giving away’ your results; your introduction is the story, not the synthesis.

Lingard L. Writing an effective literature review: Part I: Mapping the gap. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7:47–9.

Article Google Scholar

Maggio LA, Larsen K, Thomas A, Costello JA, Artino AR. Scoping reviews in medical education: A scoping review. Med Educ. 2021;55:689–700.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Adelaide: JBI; 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12 . available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global .

Chapter Google Scholar

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

Lingard L. Joining a conversation: the problem/gap/hook heuristic. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4:252–3.

Moniz T, Golafshani M, Gaspar CM, et al. How are the arts and humanities used in medical education? Results of a scoping review. Acad Med. 2021; https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004118 .

Alam R, Speed S, Beaver K. A scoping review on the experiences and preferences in accessing diabetes-related healthcare information and services by British Bangladeshis. Health Soc Care Community. 2012;20:155–71.

Webster F, Krueger P, MacDonald H, et al. A scoping review of medical education research in family medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:79.

Van Schalkwyk SC, Hafler J, Brewer TF, et al. Bellagio global health education initiative. Transformative learning as pedagogy for the health professions: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2019;53:547–58.

Sebok-Syer SS, Shaw JM, Asghar F, Panza M, Syer MD, Lingard L. A scoping review of approaches for measuring ‘interdependent’ collaborative performances. Med Educ. 2021;55:1123–30.

Young ME, Thomas A, Lubarsky S, et al. Mapping clinical reasoning literature across the health professions: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:107.

Howell D, Fitch M, Bakker D, et al. Core domains for a person-focused outcome measurement system in cancer (PROMS-Cancer Core) for routine care: a scoping review and Canadian Delphi Consensus. Value Health. 2013;16:76–87.

Gottlieb M, Chung A, Battaglioli N, Sebok-Syer SS, Kalantari A. Impostor syndrome among physicians and physicians in training: A scoping review. Med Educ. 2020;54:116–24.

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18:2119–26.

O’Brien K, Wilkins A, Zack E, Solomon P. Scoping the field: identifying key research priorities in HIV and rehabilitation. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:448–58.

Shorey S, Lau TC, Lau ST, Ang E. Entrustable professional activities in health care education: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2019;53:766–77.

Chan TM, Dzara K, Dimeo SP, Bhalerao A, Maggio LA. Social media in knowledge translation and education for physicians and trainees: a scoping review. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;9:20–30.

Versteeg M, Hendriks RA, Thomas A, Ommering BWC, Steendijk P. Conceptualising spaced learning in health professions education: A scoping review. Med Educ. 2020;54:205–16.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank K. O’Brien for review and feedback on a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Education Research & Innovation, and Department of Medicine, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry and Faculty of Education, Western University, London, Canada

Lorelei Lingard

Department of Occupational Science & Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Heather Colquhoun

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lorelei Lingard .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Lingard, L., Colquhoun, H. The story behind the synthesis: writing an effective introduction to your scoping review. Perspect Med Educ 11 , 289–294 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-022-00719-7

Download citation

Received : 27 May 2022

Revised : 09 June 2022

Accepted : 13 June 2022

Published : 12 August 2022

Issue Date : October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-022-00719-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Synthesis/Response Workshop

Name of writer

Name of first reader

The purpose of today's workshop is to assess focus and development of the synthesis/ response. Your first task is to read the essay all the way through without marking it or filling out this sheet. After you finish reading, answer the following questions regarding the essay.

- What is the common theme that this essay addresses?

- Does the synthesis address the common theme? Make marginal comments to show where the synthesis gets away from the common theme or where examples from the authors do not seem related to the theme.

- What is the writer's position on the common theme? State it in your own words here and underline the thesis of the response on the draft.

- Is the response tightly focused? Is the focus maintained? Note on the draft any problems and offer revision suggestions here.

Development :

- Does the introduction capture your interest as a reader and provide a focus on the common theme? Explain why it is effective or ineffective.

- Are relevant examples given from each author to demonstrate how each author addresses the common theme? Point out any examples that are unclear, that need fuller development, or that seem unrelated to the common theme.

- Does the writer discuss similarities and differences, including subtle differences, among the writers? Point out where this is done effectively.

- Does the writer provide support for the response beyond what the three authors give? List the types of evidence used here.

- Do you find the writer's support in the response convincing? Why or why not?

Name of second reader

Skip Content

General Writing

All ENGL 1301 Writing Workshops for Spring 2024 will be held on Wednesdays in the Writing Center at noon. Workshops will be recorded and available to all who register.

Sign up for one of our ENGL 1301 Writing Workshops.

Discourse Community Analysis:

This workshop explores the first major essay for English 1301, the Discourse Community Analysis. Consultants will define what a discourse community is and review what makes for a successful DCA. Learn how to directly address your audience, come up with evidence, and establish your credibility as a writer. You will also get useful advice on some of the essentials of good writing, such as topic sentences and transitions.

Wednesday, February 7th @ noon

Explore the fundamentals of the RAE and reading critically. Learn how to identify the ways writers use ethos, logos, and pathos and evaluate the effectiveness of their arguments. Consultants will break down how to construct strong thesis statements and go step-by-step through the essay’s guidelines, including the structure of a good rhetorical analysis.

Wednesday, March 6th @ noon

In this workshop, learn how to advance conversations by turning them in new directions. Consultants will offer specific advice on synthesizing arguments and structuring your papers, from introduction to conclusion. You will also get the opportunity to see selections for sample Synthesis Essays, discuss successful and ineffective elements, and practice synthesis for yourself.

Wednesday, April 3rd @ noon

All ENGL 1302 Writing Workshops for Fall 2023 will be held on Wednesdays in Microsoft Teams at noon. Workshops will be recorded and available to all who register.

Sign up for one of our ENGL 1302 Writing Workshops.

Issue Proposal:

This workshop explores the first major assignment for ENGL 1302, the Issue Proposal. Workshop will review the assignment requirements and identify the best approach to completing the assignment according to the demands of the project. Consultants will discuss the assignment requirements and review what makes for a successful Issue Proposal. You will also get useful advice on some of the essentials of good writing, such as topic sentences and transitions.

Wednesday, February 14th @ noon

Mapping the Issue:

This workshop explores the criteria for the Mapping the Issue writing assignment for students enrolled in 1302. Consultants will discuss the assignment requirements and what makes for a successful Mapping the Issue paper. Learn how to organize sources based on a position, summarize main ideas from your sources, and synthesize sources that cluster around a position. The workshop will also offer techniques for transitioning between positions and using sources effectively.

Wednesday, March 27th @ noon

This workshop will cover the criteria for the final paper of ENGL 1302, the Researched Position Paper. In keeping with the other freshman writing workshops, these are intended to help students develop the skills necessary to complete the assignment and become academic writers. Consultants will offer specific advice on constructing arguments and structuring papers from introduction to conclusion as well as on using logos, pathos, and ethos in making a convincing argument.

Wednesday, April 17th @ noon

All General Writing Workshops will be held Wednesdays, 6:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. An invite with a link will be emailed to registrants prior to the workshop.

Sign up for one of our General Writing Workshops.

Developing an Effective Writing Process:

Success in college depends on developing a writing process that works for you. This workshop will help you to recognize your own writing habits and overcome those habits that do not currently serve you. We will help you develop effective strategies for planning, invention, drafting, and revision. This workshop is open to writers of all levels and disciplines.

Argumentative Writing:

Much of academic writing requires an effective written argument. This workshop introduces writers to argumentative writing and to the processes of creating an effective argument. We discuss how to create a compelling position on an issue and ways to generate reasons to support your arguable claims. We also address how to conduct research, including collecting, generating, and evaluating evidence. This workshop is open to writers of all levels and disciplines.

Would you like to improve your clarity and cohesion? In academic writing, constructing cohesive paragraphs is crucial to fostering a reader’s understanding of the ideas presented by the writer. In this workshop, we teach you how to produce well-crafted topic sentences, and how to develop additional sentences that effectively support your topic sentences. We also work with quotes and evidence to help you to effectively integrate them into your paragraphs. This workshop is open to writers of all levels and disciplines.

All Graduate Writing Workshops for Spring 2024 will be held Tuesdays, 6:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m., through Microsoft Teams. We will send out a Teams link to registered participants on the day of the workshop.

Sign up for one of our Graduate Writing Workshops.

Writing in Graduate School:

Many graduate students are unsure of the expectations for writing at the graduate level. In addition to defining general graduate school writing expectations, this workshop will review basic tenets of good academic writing and editing.

Tuesday, February 6th, 6:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.

Annotating Research Articles/Texts in Graduate School:

Join the Writing Center’s Graduate Executive Staff for an interactive presentation in which we examine the best practices for annotating research articles/texts. For scholars, annotating is a skill most are expected to know and implement; however, the process can become challenging when time constraints and large amounts of reading and research converge. Relying on scholarly works, the Executive Staff will offer a hands-on annotation workshop that will assist graduate students in all fields of study in developing a methodology and a checklist that will make annotating a more effective and manageable process. The workshop will include one to two writing examples that will be annotated together.

Tuesday, February 20th, 6:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.

Be Your Own Editor:

Learn how to identify and correct grammar errors in your own writing. This workshop will allow students to put their editing skills into practice in a friendly environment in order to demonstrate how editing can improve their writing projects. Students may bring a draft or a previously graded writing assignment to this workshop.

Tuesday, March 5th, 6:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.

Writing Abstracts:

Learn how to distill the main ideas and arguments from a much larger work into a concise, focused abstract. In this workshop, an experienced consultant will discuss the purpose of an abstract in scholarly work, academic conventions in writing an abstract, and best practices for condensing your writing in an abstract.

Tuesday, March 19th, 6:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.

Writing Literature Reviews:

In this workshop, an experienced consultant will discuss the purpose of a literature review in scholarly work, the structure and components of a literature review, and the differences between a literature review in the arts and one in the sciences. In addition, the consultant will provide best practices on synthesizing sources that cluster around a position or issue, transitioning between positions, and using sources effectively.

Tuesday, April 2nd, 6:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.

Personal statements are required in a variety of academic and professional settings, from applying to graduate school to seeking a research grant. This workshop reviews the standard structure of personal statements and best practices for presenting yourself and your work in an effective manner.

Tuesday, April 16th, 6:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.

UTA Writing Center

Contact the webmaster 411 Central Library Box 19497, Arlington, TX 76019

© 2020 The University of Texas at Arlington Careers | Contact Us | Emergency Preparedness | Mental Health Resources | Nondiscrimination and Title IX | Privacy and Legal Notice | Accessibility | Site Policies | Report Sexual Misconduct | Institutional Resume | UT System | State of Texas | Texas Veterans Portal | Statewide Search | Report Fraud

Synthesis Brainstorm

This asynchronous workshop contains a set of activities designed to help students synthesize the conversation between the sources they are examining in their Texts in Conversation essay. It invites them to move through a variety of different activities, including a map, a dinner table conversation scenario, and a mad-lib style exercise.

- Find a course

- Undergraduate study

- Postgraduate study

- MPhil/PhD research

- Short courses

- Entry requirements

- Financial support

- How to apply

- Come and meet us

- Evening study explained

- International Students

- Student Services

- Business Services

- Student life at Birkbeck

- The Birkbeck Experience

- Boost your career

- About Birkbeck

- Contact Birkbeck

- Faculties and Schools

Academic skills workshop: Synthesis: Writing about multiple sources

When: 27 February 2024, 16:00 — 17:00 Venue: Online

Book your place

This session is for Birkbeck students only.

- Do you have a tendency to write about sources like a ‘shopping list’ – one source per paragraph, with no overlap?

- Are you unsure what it means to ‘synthesise’ a range of ideas or sources?

- Would you like to be able to use the sources you’ve read more effectively in your assignments?

If you answer yes to any of these questions, then try this workshop on synthesising sources. Synthesis is the process of using more than one source to talk about a particular idea or argument. It involves comparing and contrasting sources on a particular topic, identifying where they agree or differ, in order to support your own points in your essay. This workshop will examine how synthesis works and suggest strategies for synthesising sources effectively in your own assignments.

Contact name: Kerry Bannister

- Birkbeck Law School

- Corporate website

- School of Creative Arts, Culture and Communication

- Study Skills

- Study Skills: Academic reading and writing

Introduction

Background on the Course

CO300 as a University Core Course

Short Description of the Course

Course Objectives

General Overview

Alternative Approaches and Assignments

(Possible) Differences between COCC150 and CO300

What CO300 Students Are Like

And You Thought...

Beginning with Critical Reading

Opportunities for Innovation

Portfolio Grading as an Option

Teaching in the computer classroom

Finally. . .

Classroom materials

Audience awareness and rhetorical contexts

Critical thinking and reading

Focusing and narrowing topics

Mid-course, group, and supplemental evaluations

More detailed explanation of Rogerian argument and Toulmin analysis

Policy statements and syllabi

Portfolio explanations, checklists, and postscripts

Presenting evidence and organizing arguments/counter-arguments

Research and documentation

Writing assignment sheets

Assignments for portfolio 1

Assignments for portfolio 2

Assignments for portfolio 3

Workshopping and workshop sheets

On workshopping generally

Workshop sheets for portfolio 1

Workshop sheets for portfolio 2

Workshop sheets for portfolio 3

Workshop sheets for general purposes

Sample materials grouped by instructor

Workshop Sheet: Synthesis/Response (McMahon)

As you workshop your partner's paper, answer the following questions as specifically as possible. Where they are needed, give at least one suggestion for improvement. These questions represent the criteria for an effective Synthesis/Response and will help you determine if the paper has met the requirements of the assignment. I will be asking the same kinds of questions when I read the Synthesis/Response essays.

- Does the introduction clearly present the main synthesis point that will be the focus of the essay? Do you as a reader have questions about the exact nature of the synthesis point? If so, note your confusion for the writer and suggest ways the synthesis point could be more clearly presented for the reader.

- Does the introduction clearly present the three authors whose perspectives will be developed within the synthesis? Does the introduction prepare the reader for these authors' perspectives toward the synthesis point? If not, suggest ways the writer can effectively and concisely introduce each author and each author's perspective toward the synthesis point.

- In the body of the synthesis, how explicitly and accurately are the authors' perspectives presented? If needed, suggest ways to improve the presentation of these perspectives.

- How clearly are the connections made among the authors' perspectives? Does the writer make use of "transition" words or phrases that allow the reader to see these connections clearly? If the connections among the authors' perspectives are unclear, make a note of this to the writer. Suggests ways the writer could make the connections among the authors' perspectives clearer.

- List below the similarities and/or differences among the authors' perspectives as found in the synthesis.

- Is there a clear transition from the synthesis to the response so it is obvious that the writer is now sharing his/her own ideas? What needs to be done to make this clearer?

- What is the writer's stance toward each of the author's perspectives? Is it easy to identify the writer's stance of agreement/disagreement or judgment of strong/weak in regard to each author's perspective? If not, suggest ways the writer can make his/her position clearer.

- How well does the writer develop his/her response? For each judgment of strong/weak is there a stance of agree/disagree or ample support? What kinds of support or evidence does the writer use to develop his/her response (personal experience, logical analysis, outside texts, etc.)? Write down the places where the response needs to be more fully developed.

Teen Writers' Workshop

This event will take place in-person at Morniningside Heights Library.

Draft your original, creative writing and get feedback in a supportive space.

- Audience: Teens/Young Adults (13-18 years), Young Adults/Pre GED (16-24 years)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Basics of Synthesis. As you incorporate published writing into your own writing, you should aim for synthesis of the material. Synthesizing requires critical reading and thinking in order to compare different material, highlighting similarities, differences, and connections. When writers synthesize successfully, they present new ideas based on ...

The work of analysis gives each researcher an opportunity to complicate their initial question, to compile useful information, and then to draw-or infer-some conclusions based on this new, more thorough level of understanding. While analysis is the term we use to describe the process of breaking something down, say a poem or novel, a ...

When asked to synthesize sources and research, many writers start to summarize individual sources. However, this is not the same as synthesis. In a summary, you share the key points from an individual source and then move on and summarize another source. In synthesis, you need to combine the information from those multiple sources and add your ...

the writing, provide credible evidence for your claims, and to better meet the needs of your audience. The skills used to integrate outside sources are summary, paraphrase and quotation. To create effective synthesis essays, follow these best practices. Follow the rules for documentation (MLA, APA, etc.). Tips 1. Use the best evidence.

START SMALL. Synthesis writing activities do not have to always take the shape of huge summative writing assignments. When teaching A Raisin in the Sun, I like to pause in the middle of the play and present my students with some information about redlining and other discriminatory laws and policies at the time.Using a choice board format, I ask students to read and watch a combination of ...

In this workshop, learn how to advance conversations by turning them in new directions. Consultants will offer specific advice on synthesizing arguments and structuring your papers, from introduction to conclusion. You will also get the opportunity to see selections for sample Synthesis Essays, discuss successful and ineffective elements, and practice synthesis for yourself. Register for access.

The successful synthesis essay will show readers how you have reasoned about the topic at hand by taking into account the sources critically and creating a work that draws conversations with the sources into your own thinking. Contributor: Derrian Goebel. University Writing & Speaking Center. Need to write a synthesis essay?

Putting It Together: Writing Workshop—Analysis and Synthesis. Now that you've worked through some more thorough definitions and examples of analysis, inference, and synthesis, you will be better positioned both to recognize these strategies in the work of others and to beneficially employ them in your own thinking and writing. In academic ...

In a recent writing workshop, a participant was applying the "mapping the gap" heuristic in the introduction of his paper. Mapping the gap is a strategy for writing a succinct, compelling literature review in a paper's Introduction: the writer briefly and selectively summarizes what's known in order to outline the white space—the gap—that the research fills [].

UTA Writing Center In this workshop, learn how to advance conversations by turning them in new directions. Consultants will offer specific advice on synthesizing arguments and structuring your papers, from introduction to conclusion. You will also get the opportunity to see selections for sample Synthesis Essays, discuss successful and ineffective elements, and practice synthesis for yourself.

Synthesis/Response Workshop. The purpose of today's workshop is to assess focus and development of the synthesis/ response. Your first task is to read the essay all the way through without marking it or filling out this sheet. After you finish reading, answer the following questions regarding the essay. What is the common theme that this essay ...

All ENGL 1301 Writing Workshops for Spring 2024 will be held on Wednesdays in the Writing Center at noon. Workshops will be recorded and available to all who register. ... Synthesis Essay: In this workshop, learn how to advance conversations by turning them in new directions. Consultants will offer specific advice on synthesizing arguments and ...

This asynchronous workshop contains a set of activities designed to help students synthesize the conversation between the sources they are examining in their Texts in Conversation essay. It invites them to move through a variety of different activities, including a map, a dinner table conversation scenario, and a mad-lib style exercise.

Writing Workshop 6 consists of expository workshops that allow students to explore a variety of organizational structures, such as cause-effect, compare-contrast, problem-solution, definition, and synthesis. Writing Workshop 7 includes procedural writing workshops, which give students practice

If you answer yes to any of these questions, then try this workshop on synthesising sources. Synthesis is the process of using more than one source to talk about a particular idea or argument. It involves comparing and contrasting sources on a particular topic, identifying where they agree or differ, in order to support your own points in your ...

Workshop Sheet: Synthesis/Response (McMahon) As you workshop your partner's paper, answer the following questions as specifically as possible. Where they are needed, give at least one suggestion for improvement. These questions represent the criteria for an effective Synthesis/Response and will help you determine if the paper has met the ...

Synthesis Writing Workshop #1 Conversation Among Sources REVIEW The Steps of Synthesis: 1. Read and analyze--read each of your sources to understand the claims and evidence 2. Generalize--list potential thesis statements one could make based on the sources & choose one 3. Converse--what would each source say about your thesis statement?

The Synthesis of Writing Workshop and Hypermedia-Authoring: Grades 1-4. Mott, Michael Seth; Klomes, Jeannine M. Early Childhood Research & Practice, v3 n2 Fall 2001. A process writing and hypermedia literacy program was designed, taught, and evaluated by early childhood teachers. The program, funded through a Goals 2000 grant, took place in a ...

III International Scientific-Practical Conference. "GRAPHENE AND RELATED STRUCTURES: SYNTHESIS, PRODUCTION, AND APPLICATION" (GRS-2019) Tambov, Russia, November 13-15, 2019. Main page. Program committee. Organizing committee. Materials required for submission. Important Dates.

Synthesis, timing closure March 2019 Moscow. PPA space FE IP BE INTG VRFY TEST PKG PW PRF a t Besides on your spec to balanced PPA space. EX: You want design the max Power . In the FE begin, you need consider in mind for Power Performance Area Power Your Design. FE design with PPA space Room for PPAC Optimization

Synthesis of the Mentoring Workshop* *For use only by project participants. Not for promotional or other commercial uses. Assembled by Richard Statler. Introduction. On August 18th, 2003, Pacific Crest facilitated a mentoring workshop held at the University of Idaho in Moscow. This workshop was funded by the ELE project at UI under the NSF.

Teen Writers' Workshop. Date and Time. Monday, May 6, 2024, 4 - 5 PM; Monday, May 20, 2024, 4 - 5 PM; Location. Morningside Heights Library. Fully accessible to wheelchairs. For ages 13 to 18 years. ... Draft your original, creative writing and get feedback in a supportive space. ...

On October 7th, 2003, Pacific Crest facilitated a workshop held at the University of Idaho in Moscow. This workshop was funded by the ELE project at UI under the NSF. Additional funding came from the College of Engineering at UI. The workshop was organized by Steven Beyerlein and facilitated by Dan Apple, President of Pacific Crest.