Creating an MLA Works cited page

General formatting information for your works cited section.

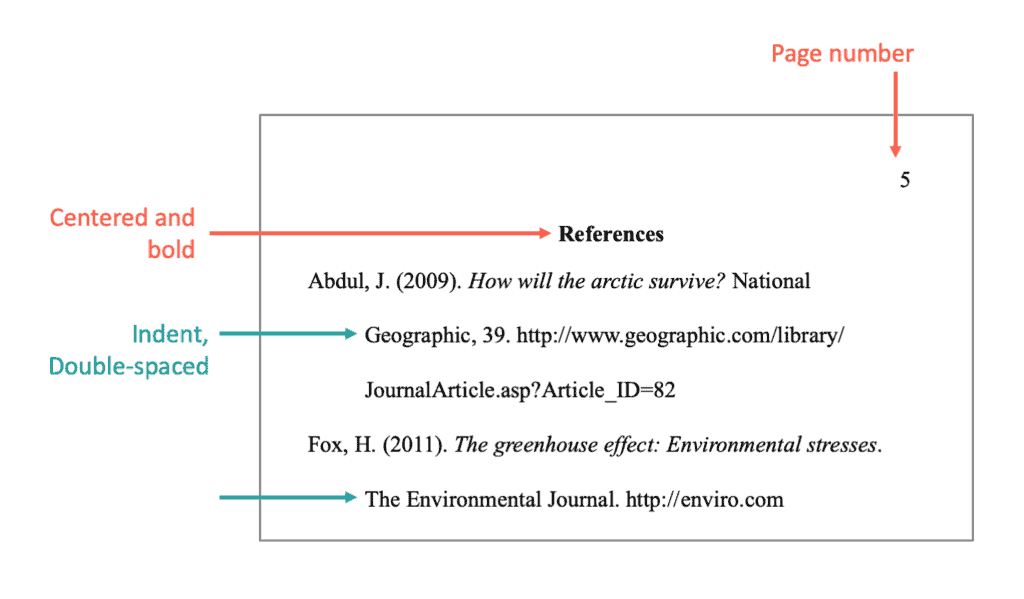

Beginning on a new page at the end of your paper, list alphabetically by author every work you have cited, using the basic forms illustrated below. Title the page Works Cited (not Bibliography), and list only those sources you actually cited in your paper. Continue the page numbering from the body of your paper and make sure that you still have 1–inch margins at the top, bottom, and sides of your page. Double-space the entire list. Indent entries as shown in the models below with what’s called a “hanging indent”: that means the first line of an entry begins at the left margin, and the second and subsequent lines should be indented half an inch from the left margin. Most word-processing programs will format hanging indents easily (look under the paragraph formatting options).

Introduction to the 8th Edition

In 2016, MLA substantially changed the way it approaches works cited entries. Each media type used to have its own citation guidelines. Writers would follow the specific instructions for how to cite a book, a translated poem in an anthology, a newspaper article located through a database, a YouTube clip embedded in an online journal, etc. However, as media options and publication formats continued to expand, MLA saw the need to revise this approach. Since a book chapter can appear on a blog or a blog post can appear in a book, how can writers account for these different formats?

MLA’s solution to this problem has been to create a more universal approach to works cited entries. No matter the medium, citations include the specifically ordered and punctuated elements outlined in the following table.

Elements of a Works Cited Entry

- Last name, First name

- Italicized If Independent ; “Put in Quotations Marks if Not.”

- Often Italicized,

- Name preceded by role title (for example: edited by, translated by, etc),

- i.e. 2nd ed., revised ed., director’s cut, etc.,

- vol. #, no. #,

- Name of Entity Responsible for Producing Source,

- i.e. 14 Feb. 2014; May-June 2016; 2017,

- i.e. pp. 53-79; Chazen Museum of Art; https://www.wiscience.wisc.edu/ (If possible, use a DOI (digital object identifier) instead of a url.)

- Optionally included when citing a web source.

If the source doesn’t include one of these elements, just skip over that one and move to the next. Include a single space after a comma or period.

The third category—”container”—refers to the larger entity that contains the source. This might be a journal, a website, a television series, etc. Sometimes a source can also appear nested in more than one container. A poem, for example, might appear in an edited collection that has been uploaded to a database. A television episode fits in a larger series which may be contained by Netflix. When a source is in a larger container, provide information about the smaller one (i.e. the edited collection or the TV series), then provide information for elements 3–10 for the larger container. For example, the works cited entry detailed below is for a chapter from an economics textbook, entitled Econometrics, that is contained on UW–Madison’s Social Science Computing Cooperative website.

Example of a Works Cited Entry

Hansen, Bruce E. “The Algebra of Least Squares.” Econometrics, University of Wisconsin Department of Economics, 2017, pp. 59-87. Social Science Computing Cooperative, UW–Madison, http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~bhansen/econometrics/Econometrics.pdf.

Here is the breakdown of these elements:

- Hansen, Bruce E.

- “The Algebra of Least Squares.”

- Econometrics,

- Other Contributors,

- University of Wisconsin Department of Economics

- Title of source.

- Social Science Computing Cooperative,

- Other contributors,

- UW-Madison,

- Publication date,

- http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~bhansen/econometrics/Econometrics.pdf.

- (This could be included, but this site is fairly stable, so the access date wasn’t deemed to be important.)

One of the benefits of this system is that it can be applied to any source. Whether you’re citing a book, a journal article, a tweet, or an online comic, this system will guide you through how to construct your citation.

A Few Notes

- Books are considered to be self-contained, so if you’re citing an entire book, items 2 and 3 get joined. After the author’s name, italicize the title, then include a period and move on items 4–9.

- No matter what your last item of information is for a given citation, end the citation with a period.

- Also, if it is appropriate to include an access date for an online source, put a period after the full url in addition to one after the access date information.

- It is particularly important to include access dates for online sources when citing a source that is subject to change (like a homepage). If the source you are working with is more stable (like a database), it’s not as critical to let your readers know when you accessed that material.

For more information about any of this, be sure to consult the 2016 MLA Handbook itself.

Works Cited page entry: Article

Article from a scholarly journal, with page numbers, read online from the journal’s website.

Shih, Shu-Mei. “Comparative Racialization: An Introduction.” PMLA , vol. 123, no. 5, 2008, pp. 1347-62. Modern Language Association , doi:10.1632/pmla.2008.123.5.1347.

Author last name, First name. “Article title.” Journal name , vol. number, issue number, year of publication, pp. numbers. Publisher , doi

PMLA provides DOI numbers, so this is used in this citation preceded by “doi:” instead of the url address. Also, given the enduring stability of PMLA’s page, no access date has been included, but it could be if the writer preferred.

Article from a scholarly journal, with multiple authors, without page numbers, read online from the journal’s website

Bravo, Juan I., Gabriel L. Lozano, and Jo Handelsman. “Draft Genome Sequence of Flavobacterium johnsoniae CI04, an Isolate from the Soybean Rhizosphere.” Genome Announcements , vol. 5, no. 4, 2017, doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01535-16.

First author last name, First name, Middle initial., Second author first name Middle initial. Last name, and Third author First name Last name. “Article title.” Journal name , vol. number, issue number, year of publication, doi

Article from a scholarly journal, no page numbers, read through an online database

Mieszkowski, Jan. “Derrida, Hegel, and the Language of Finitude.” Postmodern Culture , vol. 15, no. 3, 2005. Project MUSE, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/186557.

Author Last name, First name. “Article title.” Journal name , vol. number, issue number, year of publication. Database , url.

Article from a scholarly journal, with page numbers, read through an online database

Sherrard-Johnson, Cherene. “‘A Plea for Color’: Nella Larsen’s Iconography of the Mulatta.” American Literature , vol. 76, no. 4, 2004, pp. 833-69. Project MUSE , https://muse.jhu.edu/article/176820.

Author Last name, First name. “Article title.” Journal name , vol. number, issue number, year of publication, pp. numbers. Database , url.

Valenza, Robin. “How Literature Becomes Knowledge: A Case Study.” ELH , vol. 76, no. 1, 2009, pp. 215-45. Project MUSE . https://muse.jhu.edu/article/260309.

Author Last name, First name. “Article title.” Journal name , vol. number, issue number, year of publication, pp. numbers. Database , url.

Article from a scholarly journal, by three or more authors, print version

Doggart, Julia, et al. “Minding the Gap: Realizing Our Ideal Community Writing Assistance Program.” The Community Literacy Journal , vol. 2, no. 1, 2007, pp. 71-80.

First author Last name, First name, et al. “Article title.” Journal name , vol. number, issue number, year of publication, pp. numbers.

Raval, Amish N., et al. “Cellular Therapies for Heart Disease: Unveiling the Ethical and Public Policy Challenges.” Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology , vol. 45, no. 4, 2008, pp. 593–601.

[The Latin abbreviation “et al.” stands for “and others,” and MLA says that you should use it when citing a source with three or more authors.]

Article from a webtext, published in a web-only scholarly journal

Butler, Janine. “Where Access Meets Multimodality: The Case of ASL Music Videos.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy , vol. 21, no. 1, 2016, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/21.1/topoi/butler/index.html. Accessed 7 June 2017.

Author Last name, First name. “Article title.” Journal name , vol. number, issue number, year of publication, url. Date of access.

Balthazor, Ron, and Elizabeth Davis. “Infrastructure and Pedagogy: An Ecological Portfolio.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy , vol. 20, no. 1, 2015, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/20.1/coverweb/balthazor-davis/index.html. Accessed 7 June 2017.

First author Last name, First name and Second author First name Last name. “Article title.” Journal name , vol. number, issue number, date of publication, url. Date of access.

Article from a magazine, print version

Oaklander, Mandy. “Bounce Back.” Time , vol. 185, no. 20, 1 June 2015, pp. 36-42.

Author Last name, First name. “Article title.” Magazine name , vol. number, issue number, month and year of publication, pp. numbers.

Article from a magazine, read through an online database

Rowen, Ben. “A Resort for the Apocalypse.” The Atlantic , vol. 319, no. 2, Mar. 2017, pp. 30-31. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,uid&db =aph&AN=120967144&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Author Last name, First name. “Article title.” Magazine name , vol. number, issue number, month and year of publication, pp. numbers. Database name , url.

Article from a newspaper, read through an online database

Walsh, Nora. “For Frank Lloyd Wright’s 150th, Tours, Exhibitions and Tattoos.” New York Times , 27 May 2017, international ed. ProQuest , https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/docview/1903523834/fulltext/71B144CD12054C76PQ/2?accountid=465.

Author Last name, First name. “Article title.” Newspaper name , day month and year of publication, edition. Database name , url.

Works Cited page entry: Short Story

Short story in an edited anthology.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. “The Minister’s Black Veil.” Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Tales , edited by James McIntosh, Norton, 1987, pp. 97–107.

Author Last name, First name. “Short story title.” Anthology title , edited by Editor name, Publisher, year of publication, pp. numbers.

Works Cited page entry: Book

Book, written by one author, print version.

Bordwell, David. Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging . U California P, 2005.

Britland, Karen. Drama at the Courts of Queen Maria Henrietta . Cambridge UP, 2006.

Card, Claudia. The Atrocity Paradigm : A Theory of Evil . Oxford UP, 2005.

Cronon, William. Nature’s Metropolis . Norton, 1991.

Mallon, Florencia E. Courage Tastes of Blood: The Mapuche Community of Nicholás Ailío and the Chilean State , 1906–2001. Duke UP, 2005.

Author Last name, First name. Book title . Publisher, year of publication.

Book, written by more than one author, print version

Bartlett, Lesley, and Frances Vavrus. Rethinking Case Study Research: A Comparative Approach . Taylor & Francis, 2016.

First author Last name, First name, and Second author First name Last name. Book title . Publisher, year of publication.

Flanigan, William H., et al. Political Behavior of the American Electorate . CQ Press, 2015.

First author last name, First name Middle initial., et al. Book title . Publisher, year of publication.

Book, an edited anthology, print version

Olaniyan, Tejumola, and Ato Quayson, editors. African Literature: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory . Blackwell, 2007.

First editor Last name, First name, and Second editor first name Last name, editors. Anthology title . Publisher, year of publication.

Book, edited, revised edition, print version

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself . Edited by William L. Andrews and William S. McFeely, revised ed., Norton, 1996.

Author Last name, First name. Book title . Edited by first editor First name Middle initial. Last name and Second editor First name Middle initial. Last name, edition., publisher, year of publication.

A play in an edited collection, print version

Shakespeare, William. The Comedy of Errors: A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare . Edited by Standish Henning, The Modern Language Association of America, 2011, pp. 1–254.

Author Last name, First name. Play title . Edited by editor First name Last name, publisher, year of publication, pp. numbers.

[Page numbers are included in this entry to draw attention to the play itself since this edition includes an additional 400 pages of scholarly essays and historical information.]

Bordwell, David. Foreword. Awake in the Dark: Forty Years of Reviews, Essays, and Interviews , by Roger Ebert, U of Chicago P, 2006, pp. xiii–xviii.

Foreward author Last name, First name. Title of work in which foreward appears , by author of work, publisher, year of publication, pp. numbers.

Chapter in an edited anthology, print version

Amodia, David, and Patricia G. Devine. “Changing Prejudice: The Effects of Persuasion on Implicit and Explicit Forms of Race Bias.” Persuasion: Psychological Insights and Perspectives , edited by T.C. Brock and C. Greens, 2nd ed., SAGE Publications, 2005, pp. 249–80.

Chapter first author Last name, First name, and Second author First name Middle initial. Last name. “Chapter title.” Anthology title , edited by first editor First initial. Middle initial. Last name and Second editor first initial. Last name, edition number, publisher, year of publication, pp. numbers.

Hawhee, Debra, and Christa Olson. “Pan–Historiography: The Challenges of Writing History across Time and Space.” Theorizing Histories of Rhetoric , edited by Michelle Ballif, Southern Illinois University Press, 2013, pp. 90–105.

Chapter first author Last name, First name, and Second author First name Last name. “Chapter title.” Anthology title, edited by editor First name Last name, publisher, date of publication, page #s.

Shimabukuro, Mira Chieko. “Relocating Authority: Coauthor(iz)ing a Japanese American Ethos of Resistance under Mass Incarceration.” Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric , edited by LuMing Mao and Morris Young, Utah State UP, 2008, pp. 127–52.

Author Last name, First name Middle name. “Chapter title.” Anthology title , edited by first editor First name Last name and second editor First name Last name, Publisher, year of publication, pp. numbers.

Works Cited page entry: Electronic source

Since MLA’s 8th edition does not substantially differentiate between a source that is read in print as opposed to online, see our information about citing articles for examples about citing electronic sources from periodicals.

Non-periodical web publication, with no author and no date of publication

“New Media @ the Center.” The Writing Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison . U of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center, 2012, http://www.writing.wisc.edu/[email protected]. Accessed 8 March 2017.

“Title of publication.” Title of the containing website . Publisher of the site, year of publication. Url. Accessed date.

The syntax for a non-periodical web publication is: author (if no author, start with the title); title of the section or page, in quotation marks; title of the containing Web site as a whole, italicized; version or edition used (if none is specified, omit); publisher or sponsor of the site (if none is mentioned, then just skip this); date of publication (if none is listed, just skip this); use a comma between the publisher or sponsor and the date; the source’s url address; date of access.

Non–periodical scholarly web publication, no date of publication

Stahmer, Carl, editor. “The Shelley Chronology.” Romantic Circles . University of Maryland, https://www.rc.umd.edu/reference/chronologies/shelcron. Accessed 26 March 2017.

Editor Last name, First name, editor. “Title of publication.” Title of the containing website . Publisher, Url. Accessed date.

Non–periodical web publication, web publication, corporate author

Rhetoric Society of America. “Welcome to the website of the Rhetoric Society of America and Greetings from Gregory Clark, President of RSA!” RSA , Rhetoric Society of America, 2017, http://www.rhetoricsociety.org/aws/RSA/pt/sp/home_page. Accessed 27 March 2017.

Name of Corporate Author. “Title of publication.” Title of the containing website , Publisher of the website, year of publication, url. Accessed date

The syntax for this entry is: corporate author; title, in quotation marks; title of the overall Web site, in italics; publisher or sponsor of the site; date of publication; the source’s url address; date of access.

Since the material on homepages is subject to change, it is particularly important to include an access date for this source.

E-mail message

Blank, Rebecca. “Re: A request and an invitation for Department Chairs and Unit Leaders.” Received by Brad Hughes, 30 August 2016.

Sender Last name, First name. “Email subject line.” Received by recipient First name Last name, day month and year email was sent and received.

@UW-Madison. “Scientists at @UWCIMSS used a supercomputer to recreate the EF-5 El Reno tornado that swept through Oklahoma 6 years ago today. #okwx.” Twitter, 24 May 2017, 2:23 p.m., https://twitter.com/UWMadison/status/867461007 362359296.

@Twitter Handle. “Entire tweet word-for-word.” Twitter, day month year of tweet, time of tweet, url.

When including tweets in the works cited page, alphabetize them according to what comes after the “@” symbol.

Include the full tweet in quotation marks as the title.

Works Cited page entry: Government publication, encyclopedia entry

Government publication.

National Endowment for the Humanities. What We Do . NEH, March 2017, https://www.neh.gov/files/whatwedo.pdf.

Name of Government entity. Title of publication . Publisher, date of publication, url.

This is treated as a source written by a corporate author.

Signed encyclopedia entry

Neander, Karen. “Teleological Theories of Mental Content.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , edited by Edward N. Zalta, spring ed., 2012, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2012/entries/content-teleological/.

Author Last name, First name. “Entry title.” Title of encyclopedia , edited by editor First name Middle initial. Last name, ed., year of publication, url.

Works Cited page entry: Personal interview, film, tv program, and others

An interview you conducted.

Brandt, Deborah. Personal Interview. 28 May 2008.

Interviewee Last name, First name. Personal Interview. Day month year of interview.

A published interview, read through an online database

García, Cristina. Interview by Ylce Irizarry. Contemporary Literature , vol. 48, no. 2, 2007, pp. 174-94. EBSCOhost. http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ehost/pdfviewer /pdfviewer?vid=5&sid=f95943f6-5364-49e7-8b83-7341edc4b434%40sessionmgr104. Accessed 26 March 2017.

Interviewee Last name, First name. Interview by interviewer First name Last name. Journal title , vol. number, issue number, year of publication, pp. numbers. Database name. Url. Accessed day month and year.

Film or DVD

Sense and Sensibility . Directed by Ang Lee, performances by Emma Thompson, Alan Rickman, and Kate Winslet, Sony, 1999.

Title of film . Directed by director First name Last name, performances by first actor First name Last name, second actor First name Last name, and third actor First name Last name, Production company, year of release.

You only need to include performers’ names if that information is relevant to your work. If your paper focuses on the director, begin this entry with the director, i.e., Lee, Ang, director. Sense and Sensibility . . . . If your primary interest is an actor, begin the entry with the actor’s name, i.e., Thompson, Emma, perf. Sense and Sensibility . . . .

Television broadcast

“Arctic Ghost Ship.” NOVA . PBS, WPT, Madison, 10 May 2017.

“Title of episode.” Television series name . Broadcasting network, Broadcasting station, City, day month year of broadcast.

PBS is the network that broadcast this show; WPT is the Wisconsin PBS affiliate in Madison on which you watched this show.

Media accessed through streaming network

“Self Help.” The Walking Dead , season 5, episode 5, AMC, 9 Nov. 2014. Netflix , https://www.netflix.com/watch/80010531?trackId=14170286&tctx=1%2C4%2C04bba31e-60a0-4889-b36e-b708006e5d05-911831.

“Title of episode.” Title of television series , season number, episode number, Broadcasting channel, date month year of release. Name of streaming service used to access episode , url.

Gleizes, Albert. The Schoolboy . 1924, gouache or glue tempera on canvas. U of Wisconsin Chazen Museum of Art, Madison, WI.

Artist Last name, First name. Title of piece. Year of composition, medium. Name of institution housing art piece, City, State initials.

Address, lecture, reading, or conference presentation

Desmond, Matthew. “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City.” 1 Nov. 2016, Memorial Union Theater, Madison, WI.

Lecturer Last name, First name. “Title of lecture.” Day month year lecture is given, Location of lecture, City, State initials.

Modern Language Association Documentation

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

MLA Table of Contents

Orientation to MLA

Creating an MLA works cited page

Using MLA in–text citations

Abbreviating references to your sources

MLA Citation Guide (9th edition) : Works Cited and Sample Papers

- Getting Started

- How do I Cite?

- In-Text Citations

- Works Cited and Sample Papers

- Additional Resources

Header Image

Quick Rules for an MLA Works Cited List

Your research paper ends with a list of all the sources cited in your paper. Here are some quick rules for this Works Cited list:

- Begin the works cited list on a new page after the text.

- Name it "Works Cited," and center the section label in bold at the top of the page.

- Order the reference list alphabetically by author's last name.

- Double-space the entire list (both within and between entries).

- Apply a hanging indent of 0.5 in. to each entry. This means that the first line of the reference is flush left and subsequent lines are indented 0.5 in. from the left margin.

Sample Paper with Works Cited List

The Modern Language Association (MLA) has compiled several sample papers that include explanations of the elements and formatting in MLA 9th edition.

MLA Title Pages

MLA Title Page: Format and Template This resource discusses the correct format for title pages in MLA style and includes examples.

- << Previous: In-Text Citations

- Next: Additional Resources >>

- Last Updated: Jun 24, 2022 12:43 PM

- URL: https://paperpile.libguides.com/mla

Works-Cited-List Entries

Works cited: a quick guide, core elements.

Each entry in the list of works cited is composed of facts common to most works—the MLA core elements. They are assembled in a specific order.

The concept of containers is crucial to MLA style. When the source being documented forms part of a larger whole, the larger whole can be thought of as a container that holds the source. For example, a short story may be contained in an anthology. The short story is the source, and the anthology is the container.

Practice Template

Learn how to use the MLA practice template to create entries in the list of works cited.

- Utility Menu

fa3d988da6f218669ec27d6b6019a0cd

A publication of the harvard college writing program.

Harvard Guide to Using Sources

- The Honor Code

- Works Cited Format

What is a Works Cited list?

MLA style requires you to include a list of all the works cited in your paper on a new page at the end of your paper. The entries in the list should be in alphabetical order by the author's last name or by the element that comes first in the citation. (If there is no author's name listed, you would begin with the title.) The entire list should be double-spaced.

For each of the entries in the list, every line after the first line should be indented one-half inch from the left margin. "Works Cited" should be centered at the top of the page. If you are only citing one source, the page heading should be “Work Cited” instead of “Works Cited.” You can see a sample Works Cited here .

Building your Works Cited list

MLA citations in the Works Cited list are based on what the Modern Language Association calls "core elements." The core elements appear in the order listed below, in a citation punctuated with the punctuation mark that follows the element. For some elements, the correct punctuation will be a period, and for other elements, the correct punctuation will be a comma. Since you can choose the core elements that are relevant to the source you are citing, this format should allow you to build your own citations when you are citing sources that are new or unusual.

The author you should list is the primary creator of the work—the writer, the artist, or organization that is credited with creating the source. You should list the author in this format: last name, first name. If there are two authors, you should use this format: last name, first name, and first name last name. For three or more authors, you should list the first author followed by et al. That format looks like this: last name, first name, et al.

If a source was created by an organization and no individual author is listed, you should list that organization as the author.

Title of source .

This is the book, article, or website, podcast, work of art, or any other source you are citing. If the source does not have a title, you can describe it. For example, if you are citing an email you received, you would use this format in the place of a title:

Email to the author.

Title of container ,

A container is what MLA calls the place where you found the source. It could be a book that an article appears in, a website that an image appears on, a television series from which you are citing an episode, etc. If you are citing a source that is not “contained” in another source—like a book or a film—you do not need to list a container. Some sources will be in more than one container. For example, if you are citing a television episode that aired on a streaming service, the show would be the first container and the streaming service would be the second container.

Contributor ,

Contributors include editors, translators, directors, illustrators, or anyone else that you want to credit. You generally credit other contributors when their contributions are important to the way you are using the source. You should always credit editors of editions and anthologies of a single author’s work or of a collection of works by more than one author.

If you are using a particular version of a source, such as an updated edition, you should indicate that in the citation.

If your source is one of several in a numbered series, you should indicate this. So, for example, you might be using “volume 2” of a source. You would indicate this by “vol. 2” in the citation.

Publisher ,

For books, you can identify the publisher on the title or copyright page. For web sites, you may find the publisher at the bottom of the home page or on an “About” page. You do not need to include the publisher if you are citing a periodical or a Web site with the same name as the publisher.

Publication date ,

Books and articles tend to have an easily identifiable publication date. But articles published on the web may have more than one date—one for the original publication and one for the date posted online. You should use the date that is most relevant to your work. If you consulted the online version, this is the relevant date for your Works Cited list. If you can’t find a publication date—some websites will not include this information, for example—then you should include a date of access. The date of access should appear at the end of your citation in the following format:

Accessed 14 Oct. 2022.

The location in a print source will be the page number or range of pages you consulted. This is where the text you are citing is located in the larger container. For online sources, the location is generally a DOI, permalink, or URL. This is where your readers can locate the same online source that you consulted. MLA specifies that, if possible, you should include the DOI. Television episodes would be located at a URL. A work of art could be located in the museum where you saw it or online.

Your citations can also include certain optional elements. You should include optional elements if you think those elements would provide useful information to your readers. Optional elements follow the source title if they provide information that is not about the source as a whole. Put them at the end of the entry if they provide information about the source as a whole. These elements include the following:

Date of original publication .

If you think it would be useful to a reader to know that the text you are citing was originally published in a different era, you can put this information right after the title of the source. For example, if you are citing The Federalist Papers , you would provide the publication date of the edition you consulted, but you could also provide the original publication date:

Hamilton, Alexander, et al., editors. The Federalist Papers . October 1787-May 1788. Oxford University Press, 2008.

City of publication .

You should only use this information if you are citing a book published before 1900 (when books were associated with cities of publication rather than with publishers) or a book that has been published in a different version by the publisher in another city (a British version of a novel, for example). In the first case, you would put this information in place of the publisher's name. In the second case, the city would go before the publisher.

Descriptive terms .

If you are citing a version of a work when there are multiple versions available at the same location, you should explain this by adding a term that will describe your version. For example, if you watched a video of a presidential debate that was posted to YouTube along with a transcript, and you are quoting from the transcript, you should add the word “Transcript” at the end of your citation.

Dissertations

- Citation Management Tools

- In-Text Citations

- In-Text Citation Examples

- Examples of Commonly Cited Sources

- Frequently Asked Questions about Citing Sources in MLA Format

- Sample Works Cited List

PDFs for This Section

- Citing Sources

- Online Library and Citation Tools

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Cite an Essay

Last Updated: February 4, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Diya Chaudhuri, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Jennifer Mueller, JD . Diya Chaudhuri holds a PhD in Creative Writing (specializing in Poetry) from Georgia State University. She has over 5 years of experience as a writing tutor and instructor for both the University of Florida and Georgia State University. There are 10 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 557,616 times.

If you're writing a research paper, whether as a student or a professional researcher, you might want to use an essay as a source. You'll typically find essays published in another source, such as an edited book or collection. When you discuss or quote from the essay in your paper, use an in-text citation to relate back to the full entry listed in your list of references at the end of your paper. While the information in the full reference entry is basically the same, the format differs depending on whether you're using the Modern Language Association (MLA), American Psychological Association (APA), or Chicago citation method.

Template and Examples

- Example: Potter, Harry.

- Example: Potter, Harry. "My Life with Voldemort."

- Example: Potter, Harry. "My Life with Voldemort." Great Thoughts from Hogwarts Alumni , by Bathilda Backshot,

- Example: Potter, Harry. "My Life with Voldemort." Great Thoughts from Hogwarts Alumni , by Bathilda Backshot, Hogwarts Press, 2019,

- Example: Potter, Harry. "My Life with Voldemort." Great Thoughts from Hogwarts Alumni , by Bathilda Backshot, Hogwarts Press, 2019, pp. 22-42.

MLA Works Cited Entry Format:

LastName, FirstName. "Title of Essay." Title of Collection , by FirstName Last Name, Publisher, Year, pp. ##-##.

- For example, you might write: While the stories may seem like great adventures, the students themselves were terribly frightened to confront Voldemort (Potter 28).

- If you include the author's name in the text of your paper, you only need the page number where the referenced material can be found in the parenthetical at the end of your sentence.

- If you have several authors with the same last name, include each author's first initial in your in-text citation to differentiate them.

- For several titles by the same author, include a shortened version of the title after the author's name (if the title isn't mentioned in your text).

- Example: Granger, H.

- Example: Granger, H. (2018).

- Example: Granger, H. (2018). Adventures in time turning.

- Example: Granger, H. (2018). Adventures in time turning. In M. McGonagall (Ed.), Reflections on my time at Hogwarts

- Example: Granger, H. (2018). Adventures in time turning. In M. McGonagall (Ed.), Reflections on my time at Hogwarts (pp. 92-130). Hogwarts Press.

APA Reference List Entry Format:

LastName, I. (Year). Title of essay. In I. LastName (Ed.), Title of larger work (pp. ##-##). Publisher.

- For example, you might write: By using a time turner, a witch or wizard can appear to others as though they are actually in two places at once (Granger, 2018).

- If you use the author's name in the text of your paper, include the parenthetical with the year immediately after the author's name. For example, you might write: Although technically against the rules, Granger (2018) maintains that her use of a time turner was sanctioned by the head of her house.

- Add page numbers if you quote directly from the source. Simply add a comma after the year, then type the page number or page range where the quoted material can be found, using the abbreviation "p." for a single page or "pp." for a range of pages.

- Example: Weasley, Ron.

- Example: Weasley, Ron. "Best Friend to a Hero."

- Example: Weasley, Ron. "Best Friend to a Hero." In Harry Potter: Wizard, Myth, Legend , edited by Xenophilius Lovegood, 80-92.

- Example: Weasley, Ron. "Best Friend to a Hero." In Harry Potter: Wizard, Myth, Legend , edited by Xenophilius Lovegood, 80-92. Ottery St. Catchpole: Quibbler Books, 2018.

' Chicago Bibliography Format:

LastName, FirstName. "Title of Essay." In Title of Book or Essay Collection , edited by FirstName LastName, ##-##. Location: Publisher, Year.

- Example: Ron Weasley, "Best Friend to a Hero," in Harry Potter: Wizard, Myth, Legend , edited by Xenophilius Lovegood, 80-92 (Ottery St. Catchpole: Quibbler Books, 2018).

- After the first footnote, use a shortened footnote format that includes only the author's last name, the title of the essay, and the page number or page range where the referenced material appears.

Tip: If you use the Chicago author-date system for in-text citation, use the same in-text citation method as APA style.

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://style.mla.org/essay-in-authored-textbook/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_works_cited_page_books.html

- ↑ https://utica.libguides.com/c.php?g=703243&p=4991646

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/apaquickguide/intext

- ↑ https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/c.php?g=27779&p=170363

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ http://libguides.heidelberg.edu/chicago/book/chapter

- ↑ https://librarybestbets.fairfield.edu/citationguides/chicagonotes-bibliography#CollectionofEssays

- ↑ https://libguides.heidelberg.edu/chicago/book/chapter

About This Article

To cite an essay using MLA format, include the name of the author and the page number of the source you’re citing in the in-text citation. For example, if you’re referencing page 123 from a book by John Smith, you would include “(Smith 123)” at the end of the sentence. Alternatively, include the information as part of the sentence, such as “Rathore and Chauhan determined that Himalayan brown bears eat both plants and animals (6652).” Then, make sure that all your in-text citations match the sources in your Works Cited list. For more advice from our Creative Writing reviewer, including how to cite an essay in APA or Chicago Style, keep reading. Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Mbarek Oukhouya

Mar 7, 2017

Did this article help you?

Sarah Sandy

May 25, 2017

Skyy DeRouge

Nov 14, 2021

Diana Ordaz

Sep 25, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Work Cited Page

-11107.jpg)

How to Create a Perfect MLA Works Cited Page

Published on: Apr 29, 2024

Last updated on: Apr 30, 2024

In This Guide

Using In-Text Citations According to MLA 9th Edition

How to Write an MLA Annotated Bibliography

MLA Paper Format: Guidelines With Examples for Students and Researchers

How to Format Your MLA Header Correctly

How to Format MLA Title Page: Learn with Examples

How to Format Block Quotes in MLA Style with Examples

How to Use MLA Footnotes & Endnotes in Your Academic Writing

Formatting MLA Source Titles - Easy Guide for Students

MLA Date Format: What You Need to Know

Writing papers and citing sources in MLA style can be frustrating. If you are writing a research paper or an essay on liberal arts or humanities, you may have been instructed to use MLA (Modern Language Association) style.

In MLA style , you need to include a works cited page at the end of your document. This page lists all the sources that you have cited in your paper, giving full details of each source.

But how do you format your works cited page in MLA correctly? When to use italics or quotation marks? And what are some common mistakes to avoid?

In this blog post, we will answer these questions and provide some tips and examples to help you create a perfect MLA works cited page.

Formatting the Works Cited Page

According to MLA Handbook (9th Ed.), here is what you should know about citing your sources.

- It should appear on a separate page at the end of your paper, with the title page “Works Cited” centered and in plain text (no italics, bold, or quotation marks).

- The work cited list should have one-inch margins and the same header (Author's Last Name Page Number) as the rest of your paper.

- It should list all the cited sources you have cited in your paper, alphabetically by the author’s last name. If there is no author, use the title instead.

- The page should use a hanging indent for each entry. The first line of each entry is aligned with the left margin, and the second and subsequent lines are indented by 0.5 inches.

- The entries should use double spacing throughout, with no extra space in between.

Here is an example of how a works cited page might look like:

Examples of Works Cited Entries

The format of each entry in your works cited page depends on the type of source that you are citing.

MLA style has specific rules for different types of sources, such as books, articles, websites, etc.

Here are some common source types and how to cite them in your works cited page:

Citing a Book

A book is a written work that is published in print or electronically. To cite a book in MLA style, you need to provide the following information:

- Author’s last name, first name

- Title of Book (in italics)

- Year of publication

Here is an example of how to cite a book in MLA style:

Citing an Article in a Print Journal

A print journal is a periodical publication that is issued in print format. To cite a journal article in MLA format, you need to provide the following information:

- “Title of Article” (in quotation marks)

- Title of Journal (in italics)

- Volume number

- Issue number

Here is an example of how to cite an article in a print journal in MLA style:

Citing an Article Online

An online article is an article that is published on the internet, either on a website or in an online database. To cite an online article in MLA style, you need to provide the following information:

- Name of Database (if any)

- DOI or URL (without https://, if available)

- Date Accessed (optional)

Here is an example of how to cite an online article in MLA style:

Citing a Website

A website is a collection of web pages that are accessible on the internet. To cite a website or a web page in MLA style, you need to provide the following information:

- Author’s last name, and first name (if any)

- “Title of Web Page” (in quotation marks)

- Title of Website (in italics)

- Date of publication or update (if any)

- URL (without https://)

Here is an example of how to cite a website or a web page in MLA style:

Common Mistakes to Avoid

When creating your works cited page, make sure to avoid these common mistakes:

Missing Information

Check that you have included all the relevant information for each source, such as the author, title, publisher, date, etc. Also, make sure that the information is accurate and consistent with the source.

Incorrect Information

Do not misspell the author’s name, change the title of the source, or use a different date than the one given in the source.

Inconsistent or Incorrect Formatting

Follow the MLA style rules for formatting each source type, and use the same format for all sources of the same type.

Do not use different punctuation marks, capitalization, or abbreviations for different sources.

Also, ensure that your entries are aligned and indented correctly and that you use double spacing throughout.

Mixing In-Text Citations and Works Cited

Remember that in-text citations and works cited entries are not the same thing.

- In-text citations are brief references that you include in the body of your paper, usually in parentheses, to indicate where you have used a source.

- Works cited entries are full references you list at the end of your paper, giving all the details of each source.

Do not confuse the two or use them interchangeably.

Final Thoughts!

Creating a perfect MLA works cited page is not difficult, but it requires attention to detail and adherence to the MLA style rules.

By following the tips and examples in this blog post, you can ensure that your works cited page is accurate, consistent, and complete. This will help you avoid plagiarism and give proper credit to the sources that you have used in your paper.

Perfect Solution to Your Citation Problems

Do all these citation rules sound confusing to you? Well, we have the perfect solution to your citation problems.

Our citation machine is a free online tool that helps you create citations for websites, books, journals, and more.

All you have to do is enter the details of your source in our citation machine MLA , and our tool will generate and format your references automatically with our works cited generator.

Try it out today and see the difference it makes!

Nathan D. (Literary analysis)

Introducing Nathan D., PhD, an esteemed author on PerfectEssayWriter.ai. With a profound background in Literary Analysis and expertise in Educational Theories, Nathan brings a wealth of knowledge and insight to his writings. His passion for dissecting literature and exploring educational concepts shines through in his meticulously crafted essays and analyses. As a seasoned academic, Nathan's contributions enrich our platform, offering valuable perspectives and engaging content for our readers.

On This Page On This Page

Share this article

Keep Reading

Home / Guides / Citation Guides / APA Format / APA Reference Page

How to Format an APA Reference Page

In APA, the “Works Cited” page is referred to as a “Reference List” or “Reference Page.” “Bibliography” also may be used interchangeably, even though there are some differences between the two.

If you are at the point in your article or research paper where you are looking up APA bibliography format, then congratulations! That means you’re almost done.

In this guide, you will learn how to successfully finish a paper by creating a properly formatted APA bibliography. More specifically, you will learn how to create a reference page . The guidelines presented here come from the 7 th edition of the APA’s Publication Manual .

A note on APA reference page style: In this guide, “bibliography” and “references” may be used interchangeably, even though there are some differences between the two. The most important thing is to use the label “References” when writing your paper since APA style recommends including a reference page.

Here’s a run-through of everything this page includes:

Difference between an APA bibliography and a reference page

What about annotated bibliographies, understanding apa reference page format, apa reference page formatting: alphabetizing by surname, q: what should not be on an apa reference page.

The difference between a bibliography and a reference page is a matter of scope. A bibliography usually includes all materials and sources that were used to write the paper. A reference page, on the other hand, only includes entries for works that were specifically cited in the text of the paper.

There are some cases in which a professor or journal might request an annotated bibliography . An annotated bibliography is basically a reference page that includes your comments and insights on each source.

An annotated bibliography can be a document all on its own, or part of a bigger document. That means creating an annotated bibliography by itself could be an assignment, or you may have to include one as part of your research paper, journal submission, or other project.

If you do need to add an APA annotated bibliography , it goes after the reference page on its own page, inside the appendices.

A properly formatted APA reference page begins on a new page, after the end of the text. It comes before any figures, tables, maps, or appendices. It’s double-spaced and features what’s called a hanging indent , where the first line of each reference is not indented, and the second line of each reference is indented 0.5 inches. The reference page is also labeled with a bold, center-justified, and capitalized “References.”

To summarize, the reference page should be:

- Placed on its own page, after the text but before any tables, figures, or appendices.

- In the same font as the rest of the paper.

- Double-spaced the whole way through (including individual references).

- Formatted with hanging indents (each line after the first line of every entry indented 0.5 inches).

- Labeled with a bold, center-justified, and capitalized “References.”

Note: You can use the paragraph function of your word processing program to apply the hanging indent.

Q: What font am I supposed to use for the reference page or bibliography?

The APA reference page/bibliography should be in the same font as the rest of your paper. However, APA Style does not actually call for one specific font. According to Section 2.19 of the Publication Manual , the main requirement is to choose a font that is readable and accessible to all users. Some of the recommended font options for APA style include:

- Sans serif fonts: Calibri (11pt), Arial (11pt), or Lucida (10pt).

- Serif fonts: Times New Roman (12pt), Georgia (11pt), or Normal/Computer Modern (10pt).

Q: What are the margins supposed to be for the reference page or bibliography?

Aside from the 0.5 inch hanging indent on the second line of each reference entry, you do not need to modify the margins of the reference page or bibliography. These should be the same as the rest of your paper, which according to APA is 1-inch margins on all sides of the page. This is the default margin setting for most computer word processors, so you probably won’t have to change anything.

Q: What information goes into an APA style reference page or bibliography?

An APA style reference page should include full citations for all the sources that were cited in your paper. This includes sources that were summarized, paraphrased, and directly quoted. Essentially, if you included an in-text citation in your paper, that source should also appear in your reference list. The reference list is organized in alphabetical order by author.

The formatting for reference list citations varies depending on the kind of source and the available information. But for most sources, your reference list entry will include the following:

- The last name(s) and initials of the author(s).

- The date the source was published (shown in parentheses).

- The title of the source in sentence case. The title should be in italics if the source stands on its own (like a book, webpage, or movie).

- The name of the periodical, database, or website if the source is an article from a magazine, journal, newspaper, etc. Names of periodicals are usually italicized; names of databases and websites usually are not.

- The publisher of the source and/or the URL where the source can be found.

Here are a few templates and examples for how common sources should be formatted in an APA style reference list. If your source is not found here, there is also a guide highlighting different APA citation examples .

Citing a Book

Author’s last name, Author’s first initial. Author’s middle initial. (Year of publication). Title of work . Publisher.

James, Henry. (2009). The ambassadors . Serenity Publishers.

Citing a Journal

Author’s last name, Author’s first initial. Author’s middle initial. (Year, Month Date published). Article title. Journal Name , Volume(Issue), page number(s). https://doi.org/ or URL (if available)

Jacoby, W. G. (1994). Public attitudes toward government spending. American Journal of Political Science , 38(2), 336-361. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111407

Citing a Website

Author’s last name, Author’s first initial. Author’s middle initial. (Year, Month Date published). Article title or page title . Site Name. URL

Limer, E. (2013, October 1). Heck yes! The first free wireless plan is finally here . Gizmodo. https://gizmodo.com/heck-yes-the-first-free-wireless-plan-is-finally-here

Next, let’s take a look at a real example of a properly formatted APA reference page to see how these pieces come together.

APA reference page example

Creating an APA reference page is actually a lot easier than creating a bibliography with other style guides. In fact, as long as you are aware of the formatting rules, the reference page practically writes itself as you go.

Below is an example reference page that follows the guidelines detailed above. EasyBib also has a guide featuring a complete APA style sample paper , including the reference page.

All APA citations included in the reference page should be ordered alphabetically, using the first word of the reference entry. In most cases, this is the author’s surname (or the surname of the author listed first, when dealing with citations for sources with multiple authors ). However, there are times when a reference entry might begin with a different element.

Creating an alphabetized reference page or bibliography might seem like a simple task. But when you start dealing with multiple authors and similar last names, it can actually get a little tricky. Fortunately, there are a few basic rules that can keep you on track.

The “nothing precedes something” rule

When the surnames of two or more authors begin with the same letters, the “nothing precedes something” rule is how to figure it out. Here is an example of how it works.

Imagine your reference page includes the authors Berg, M.S. and Bergman, H.D. The first four letters of each author are the same. The fifth letters are M and H respectively. Since H comes before M in the alphabet, you might assume that Bergman, H.D. should be listed first.

APA Style requires that “nothing precede something,” which means that Berg will appear before Bergman. Similarly, a James would automatically appear before a Jameson, and a Michaels before a Michaelson.

Disregard spaces and punctuation marks

If a surname has a hyphen, apostrophe, or other punctuation mark, it can be ignored for alphabetization purposes. Similarly, anything that appears inside of parentheses or brackets should be disregarded.

Ordering multiple works by the same author

It is not uncommon for a research paper to reference multiple books by the same author. If you have more than one reference entry by the same person, then the entries should be listed chronologically by year of publication.

If a reference entry has no year of publication available, then it should precede any entries that do have a date. Here’s an example of a properly alphabetized order for multiple entries from the same author:

Guzman, M.B. (n.d.).

Guzman, M.B. (2016).

Guzman, M.B. (2017).

Guzman, M.B. (2019).

Guzman, M.B. (in press).

“In press” papers do not yet have a year of publication associated with them. All “in press” sources are listed last, like the one shown above.

Ordering works with the same author and same date

If the same author has multiple entries with the same year of publication, you need to differentiate them with lowercase letters. Otherwise, the in-text citations in your paper will correspond to more than one reference page entry.

Same author and same year of publication

Here’s a look at how to use lowercase letters to differentiate between entries with the same author and same year of publication:

Guzman, M.B. (2020a).

Guzman, M.B. (2020b).

Guzman, M.B. (2020c).

These lowercase letters are assigned to make the in-text citations more specific. However, it does not change the fact that their year of publication is the same. If no month or day is available for any of the sources, then they should be ordered alphabetically using the title of the work.

When alphabetizing by title, ignore the words “A,” “An,”,and “The” if they’re the first word of the title.

Same author and same year of publication, with more specific dates

If more specific dates are provided, such as a month or day, then it becomes possible to order these entries chronologically.

Guzman, M.B. (2020b, April 2).

Guzman, M.B. (2020c, October 15).

Ordering authors with the same surname but different initials

Authors who share the same surname but have different first or middle names can be alphabetized by their first initial or second initial.

Guzman, R.L. (2015).

Ordering works with no listed author, or an anonymous author

If you have reference entries with no listed author, the first thing to double-check is whether or not there was a group author instead. Group authors can be businesses, task forces, nonprofit organizations, government agencies, etc.

If there is no individual author listed, then have another look at the source. If it is published on a government agency website, for instance, there is a good chance that the agency was the author of the work, and should be listed as such in the reference entry. You can read more about how to handle group authors in Section 9.11 of the Publication Manual .

What if the work is actually authored by “Anonymous”?

If the work you’re referencing actually has the word “Anonymous” listed as the author, then you can list it as the author and alphabetize it as if it were a real name. But this is only if the work is actually signed “Anonymous.”

What if there is no listed author and it’s definitely not a group author?

If you have confirmed that there is no individual or group author for the work, then you can use the work’s title as the author element in the reference entry. In any case where you’re using the work’s title to alphabetize, you should skip the words “A,” “An,” and “The.”

An APA reference page should not contain any of the following:

- The content of your paper (the reference page should start on its own page after the end of your paper).

- Entries for works for further reading or background information or entries for an epigraph from a famous person (the reference page should only include works that are referenced or quoted in your paper as part of your argument).

- Entries for personal communications such as emails, phone calls, text messages, etc. (since the reader would not be able to access them).

- Entries for whole websites, periodicals, etc. (If needed, the names of these can be mentioned within the body of your paper instead.)

- Entries for quotations from research participants (since they are part of your original research, they do not need to be included).

Published October 28, 2020.

APA Formatting Guide

APA Formatting

- Annotated Bibliography

- Block Quotes

- et al Usage

- In-text Citations

- Multiple Authors

- Paraphrasing

- Page Numbers

- Parenthetical Citations

- Reference Page

- Sample Paper

- APA 7 Updates

- View APA Guide

Citation Examples

- Book Chapter

- Journal Article

- Magazine Article

- Newspaper Article

- Website (no author)

- View all APA Examples

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

The following rules will help you identify when to use DOIs and when to use URLs in references:

- Use a DOI wherever available, be it a print version or online version.

- For a print publication that does not have a DOI, do not add a DOI or URL (even if a URL is available).

- For an online publication, if both a DOI and URL are given, include only the DOI.

- For online publications that only have a URL (and no DOI), follow the below recommendations:

- Add a URL in the reference list entry for publications from websites (other than databases). Double check that the URL will work for readers.

- For publications from most academic research databases, which are easily accessible, do not include a URL or database information in the reference. In this case, the reference will be the same as the print version.

- For publications from databases that publish limited/proprietary work that would only be available in that database, include the database name and the URL. If the URL would require a login, include the URL for the database home page or login page instead of the URL for the work.

- If a URL will not work for the reader or is no longer accessible, follow the guidance for citing works with no source.

To format your APA references list, follow these recommendations:

- Begin the references on a new page. This page should be placed at the end of the paper.

- All sides of the paper should have a 1-inch margin.

- Set the heading as “References” in bold text and center it.

- Arrange the reference entries alphabetically according to the first item within the entries (usually the author surname or title).

- Add a hanging indent of 0.5 inches (i.e., indent any line after the first line of a reference list entry).

See above for a visual example of a reference page and additional examples.

Special Cases

Multiple entries with the same author(s) are arranged by publication year. Entries with no dates first, then in chronological order. If the year published is also the same, a letter is added to the year and the entries are arranged alphabetically (after arrangement by year).

- Robin, M. T. (n.d.)

- Robin, M. T. (1987)

- Robin, M. T. (1989a)

- Robin, M. T. (1989b)

Single-author source and multi-author source that share one author. One-author entries are listed first even if the multi-author entries were published earlier.

- Dave, S. P., Jr. (2006)

- Dave, S. P., Jr., & Glyn, T. L. (2005)

For references with multiple authors that have the same first author but different subsequent authors, alphabetize the entries by the last name of the second author (or third if the first two authors are the same).

APA Citation Examples

Writing Tools

Citation Generators

Other Citation Styles

Plagiarism Checker

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

- Engaging With Sources Effectively

by acburton | Apr 30, 2024 | Resources for Students , Writing Resources

We’ve talked about the three ways to integrate sources effectively that allow writers to provide evidence and support for their argument, enter the scholarly conversation, and give credit to the original authors of the work that has helped and informed them. Sources also encourage writers to share their own knowledge and authority with others, help readers find additional sources related to the topic they are interested in, and protect you by giving credit where credit is due (thus avoiding plagiarism). In other words, sources are much more than just something we add on at the end of our writing!

When writing about a source or simply referencing it, we are positioning ourselves in response to, or in conversation with that source, with the goal of focusing our writing on our own argument/thesis. Sources do not stand on their own within a piece of writing and that is why, alongside finding strong and reputable sources worth responding to and making sure that we fully understand sources (even before writing about them), it is critical to engage with our sources in meaningful ways. But how exactly do we effectively engage with our sources in our writing?

Joseph Harris, in How To Do Things with Texts , presents four different ways of “rewriting the work of others”, three of which provide insight into the how of engaging sources. When a writer forwards the work of another writer, they are applying the concepts, topics, or terms from one reading, text, or situation to a different reading, text or situation. By countering the ideas found in source material, a writer argues “against the grain of a text” by underlining and countering ideas that a writer may be in disagreement with. Taking an approach is the adaptation of a theory or method from one writer to a new set of issues or texts. Harris’ book provides a thorough classification of methods to engage with a source. For something a little simpler, here are three basic ways you can get started effectively engaging with sources (Harris 5-7).

3 Basic Ways to Engage with Sources Effectively

- Disagree and Explain Why. Persuade your reader that the argument or information in a source should be questioned or challenged.

- Agree, But With Your Own Take. Add something new to the conversation. Expand a source’s insights or argument to a new situation or your own example. Provide new evidence and discuss new implications.

- Agree and Disagree Simultaneously. This is a nuanced approach to complex sources or complex topics. You can, for example, agree with a source’s overall thesis, but disagree with some of its reasoning or evidence.

Remember that this is not an exhaustive list. When engaging with others’ sources as a way to support our own ideas and argument, it is crucial that we engage with critical thinking, nuance, and objectivity to ensure that we are constructing unbiased, thoughtful, and compelling arguments.

Some of the different areas throughout your essay that will benefit from effective engagement with source material include: your thesis statement, analysis, and conclusion.

- Thesis Statement. The argument that you make in your thesis statement can challenge, weaken, support, or strengthen what is being argued by your source or sources.

Analysis. Thorough analysis in your body paragraphs emphasize the role of your argument in comparison to that found in your source material. Bring your analysis back to your thesis statement to reinforce the connection between the two.

- Conclusion. Consider the “big picture” or “takeaways” to leave your reader with.

There are many other, sometimes optional, essay sections or writing styles that benefit from critical engagement with a source. These can include literature reviews, reflections, critiques, and so on.

Strategies for Engaging Critically From Start to Finish

- Aim to dig deeper than surface level. Ask the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of a source, as well as ‘how’ and ‘why’ it is relevant to the topic at hand and the argument you are making.

- Ask yourself if you’ve addressed every possible question, concern, critique, or “what if” that comes to mind; put yourself in the place of your readers.

- Use TEAL body paragraph development as a template and guide for developing thorough analysis in your body paragraphs. Effectively engaging with your sources is essential to the analysis portion of the TEAL formula and to creating meaningful engagement with your sources.

- Visit the Writing Center for additional support on crafting engaging analyses and for other ways to engage with your source material from thesis to conclusion.

Our Newest Resources!

- Revision vs. Proofreading

- The Dos and Don’ts of Using Tables and Figures in Your Writing

- Synthesis and Making Connections for Strong Analysis

- Writing Strong Titles

Additional Resources

- Graduate Writing Consultants

- Instructor Resources

- Student Resources

- Quick Guides and Handouts

- Self-Guided and Directed Learning Activities

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NEWS FEATURE

- 01 May 2024

- Correction 07 May 2024

Why is exercise good for you? Scientists are finding answers in our cells

- Gemma Conroy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Researchers are looking into the molecular basis of how exercise benefits health, to help treat diseases. Credit: Ozan Guzelce/dia images via Getty

You have full access to this article via your institution.

When Bente Klarlund Pedersen wakes up in the morning, the first thing she does is pull on her trainers and go for a 5-kilometre run — and it’s not just about staying fit. “It’s when I think and solve problems without knowing it,” says Klarlund Pedersen, who specializes in internal medicine and infectious diseases at the University of Copenhagen. “It’s very important for my well-being.”

Whether it’s running or lifting weights, it’s no secret that exercise is good for your health. Research has found that briskly walking for 450 minutes each week is associated with living around 4.5 years longer than doing no leisure-time exercise 1 , and that engaging in regular physical activity can fortify the immune system and stave off chronic diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. But, says Dafna Bar-Sagi, a cell biologist at New York University, the burning question is how does exercise deliver its health-boosting effects?

“We know that it is good, but there is still a huge gap in understanding what it is doing to cells,” says Bar-Sagi, who walks on a treadmill for 30 minutes, five days a week.

In the past decade, researchers have started to build a picture of the vast maze of cellular and molecular processes that are triggered throughout the body during — and even after — a workout. Some of these processes dial down inflammation, whereas others ramp up cellular repair and maintenance. Exercise also prompts cells to release signalling molecules that carry a frenzy of messages between organs and tissues: from muscle cells to the immune and cardiovascular systems, or from the liver to the brain.

But researchers are just beginning to work out the meaning of this cacophony of crosstalk, says Atul Shahaji Deshmukh, a molecular biologist at the University of Copenhagen. “Any single molecule doesn’t work alone in the system,” says Deshmukh, who enjoys mountain biking during the summer. “It’s an entire network that functions together.”

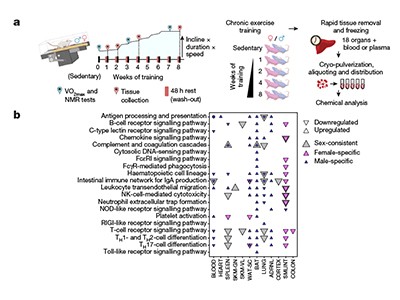

Endurance exercise causes a multi-organ full-body molecular reaction

Exercise is also attracting attention from funders. The US National Institutes of Health (NIH), for instance, has invested US$170 million into a six-year study of people and rats that aims to create a comprehensive map of the molecules behind the effects of exercise, and how they change during and after a workout. The consortium behind the study has already published its first tranche of data from studies in rats, which explores how exercise induces changes across organs, tissues and gene expression, and how those changes differ between sexes 2 – 4 .

Building a sharper view of the molecular world of exercise could reveal therapeutic targets for drugs that mimic its effects — potentially offering the benefits of exercise in a pill. However, whether such drugs can simulate all the advantages of the real thing is controversial.

The work could also offer clues about which types of physical activity can benefit people with chronic illnesses, says Klarlund Pedersen. “We think you can prescribe exercise as you can prescribe a medicine,” she says.

Hard-wired for exercise

Exercise is a fundamental thread in the human evolutionary story. Although other primates evolved as fairly sedentary species, humans switched to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle that demanded walking long distances, carrying heavy loads of food and occasionally running from threats.

Those with better athletic prowess were better equipped to live longer lives, which made exercise a core part of human physiology, says Daniel Lieberman, a palaeoanthropologist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The switch to a more active lifestyle led to changes in the human body: exercise burns up energy that would otherwise be stored as fat, which, in excess amounts, increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and some cancers. The stress induced by running or pumping iron has the potential to damage cells, but it also kick-starts a cascade of cellular processes that work to reverse those effects. This can leave the body in better shape than it would be without exercise, says Lieberman.

Researchers have been exploring some of the biological changes that occur during exercise for more than a century. In 1910, pharmacologist Fred Ransom at the University of Cambridge, UK, discovered that skeletal muscle cells secrete lactic acid, which is created when the body breaks down glucose and turns it into fuel 5 . And in 1961, researchers speculated that skeletal muscle releases a substance that helps to regulate glucose during exercise 6 .

More clues were in store. In 1999, Klarlund Pedersen and her colleagues collected blood samples from runners before and after they took part in a marathon and found that several cytokines — a type of immune molecule — spiked immediately after exercise and that many remained elevated for up to 4 hours afterwards 7 . Among these cytokines were interleukin-6 (IL-6), a multifaceted protein that is a key player in the body’s defence response. The following year, Klarlund Pedersen and her colleagues discovered 8 that IL-6 is secreted by contracting muscles during exercise, making it an ‘exerkine’ — the umbrella term for compounds produced in response to exercise.

Exercising regularly can strengthen the immune system and stave off disease. Credit: Mike Kemp/Getty

High levels of IL-6 can be beneficial or harmful, depending on how it is provoked. At rest, too much IL-6 has an inflammatory effect and is linked to obesity and insulin resistance, a hallmark of type 2 diabetes, says Klarlund Pedersen. But when exercising, the molecule activates its more calming family members, such as IL-10 and IL-1ra, which tone down inflammation and its harmful effects. “With each bout of exercise, you provoke an anti-inflammatory response,” says Klarlund Pedersen. Although some physical activity is better than none, high-intensity, long-duration exercise that engages large muscles — such as running or cycling — will crank up IL-6 production, adds Klarlund Pedersen.

Exercise is a balancing act in other ways, too. Physical activity produces cellular stress, and certain molecules counterbalance this damaging effect. When mitochondria — the powerhouses that supply energy in cells — ramp up production during exercise, they also produce more by-products called reactive oxygen species (ROS), which, in excessive amounts, can damage proteins, lipids and DNA. But these ROS also kick-start a horde of protective processes during exercise, offsetting their more toxic effects and fortifying cellular defences.

Among the molecular stars in this maintenance and repair arsenal are the proteins PGC-1α, which regulates important skeletal muscle genes, and NRF2, which activates genes that encode protective antioxidant enzymes. During exercise, the body has learnt to benefit from a fundamentally stressful process. “If stress doesn’t kill you it makes you stronger,” says Ye Tian, a geneticist at the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing.

Exerkines everywhere

Since IL-6 ushered in the exerkine era, the explosion of multiomics — an approach that combines various biological data sets, such as the proteome and metabolome — has allowed researchers to go beyond chasing single molecules. They can now begin untangling the convoluted molecular web that lies behind exercise, and how it interacts with different systems across the body, says Michael Snyder, a geneticist at Stanford University in California, who recently switched from running to weightlifting. “We need to understand how these all work together, because [humans] are a homeostatic machine that needs to be properly tuned,” he says.

In 2020, Snyder and his colleagues took blood samples from 36 people aged between 40 and 75 years old before, during and at various time intervals after the volunteers ran on a treadmill. The team used multiomic profiling to measure more than 17,000 molecules, more than half of which showed significant changes after exercise 9 . They also found that exercise triggered an elaborate ‘choreography’ of biological processes such as energy metabolism, oxidative stress and inflammation. Creating a catalogue of exercise molecules is an important first step in understanding their effects on the body, says Snyder.

How an exercise habit paves the way for injured muscles to heal