- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Research: How Bias Against Women Persists in Female-Dominated Workplaces

- Amber L. Stephenson,

- Leanne M. Dzubinski

A look inside the ongoing barriers women face in law, health care, faith-based nonprofits, and higher education.

New research examines gender bias within four industries with more female than male workers — law, higher education, faith-based nonprofits, and health care. Having balanced or even greater numbers of women in an organization is not, by itself, changing women’s experiences of bias. Bias is built into the system and continues to operate even when more women than men are present. Leaders can use these findings to create gender-equitable practices and environments which reduce bias. First, replace competition with cooperation. Second, measure success by goals, not by time spent in the office or online. Third, implement equitable reward structures, and provide remote and flexible work with autonomy. Finally, increase transparency in decision making.

It’s been thought that once industries achieve gender balance, bias will decrease and gender gaps will close. Sometimes called the “ add women and stir ” approach, people tend to think that having more women present is all that’s needed to promote change. But simply adding women into a workplace does not change the organizational structures and systems that benefit men more than women . Our new research (to be published in a forthcoming issue of Personnel Review ) shows gender bias is still prevalent in gender-balanced and female-dominated industries.

- Amy Diehl , PhD is chief information officer at Wilson College and a gender equity researcher and speaker. She is coauthor of Glass Walls: Shattering the Six Gender Bias Barriers Still Holding Women Back at Work (Rowman & Littlefield). Find her on LinkedIn at Amy-Diehl , Twitter @amydiehl , and visit her website at amy-diehl.com

- AS Amber L. Stephenson , PhD is an associate professor of management and director of healthcare management programs in the David D. Reh School of Business at Clarkson University. Her research focuses on the healthcare workforce, how professional identity influences attitudes and behaviors, and how women leaders experience gender bias.

- LD Leanne M. Dzubinski , PhD is acting dean of the Cook School of Intercultural Studies and associate professor of intercultural education at Biola University, and a prominent researcher on women in leadership. She is coauthor of Glass Walls: Shattering the Six Gender Bias Barriers Still Holding Women Back at Work (Rowman & Littlefield).

Partner Center

- Twitter Icon

- Facebook Icon

- Reddit Icon

- LinkedIn Icon

A case study of gender bias in science reporting

An analysis reveals a persistent gender disparity in the sources quoted in Nature ’s news and feature articles, although the gap is shrinking.

Gender disparities in science have attracted a lot of attention in the last decade or so, but the biases against women in media coverage of science haven’t received nearly as much focus. A recent study of Nature ’s news and feature articles sheds light on how often women are quoted in science news. The study finds that women continue to be quoted less often than men in the high-profile journal, although the gap seems to be narrowing.

Conducted by Natalie Davidson and Casey Greene of the University of Colorado School of Medicine, the study , posted in June on bioRxiv, analyzed more than 22 000 journalist-written news and feature articles that were published in the front half of Nature from 2005 to 2020. The researchers used software to approximately identify the genders and ethnicities of authors and sources. The software had a few limitations: It had a slight male bias, didn’t include a nonbinary gender assignment, and couldn’t identify all names. The researchers compared the software-assessed demographics of sources quoted in Nature ’s news section with that of the authors of the more than 13 000 research papers published in the back half of Nature during that period.

Davidson and Greene found a significant decrease in the proportion of men quoted in Nature ’s pages over those 15 years. The analysis found that in 2005, 87% of quotes were deemed to have come from men, whereas male researchers were the first authors of 73% of research papers in the study sample. By 2020 the likelihood that quotes came from men was down to about 69%. Articles about career-related topics were the only ones to achieve gender parity, the study found.

Although Nature publishes research from several disciplines with different proportions of female participation, the new study doesn’t distinguish the results by field or topic. Research papers published in Nature also may not be representative of the gender balance in the academic community or of research overall, Davidson says.

To account for that possible bias, the researchers selected another random sample of 36 000 research papers published over the same period in other journals run by publishing giant Springer Nature, which owns Nature . When compared with that data set, the estimated proportion of men quoted in Nature news and feature articles in 2020 (69%) is higher than the percentage of male first authors of the sample papers (about 63%) but lower than the rate of male last authors (76%). In contrast, the male quotation rate is lower than the rates of male first and last authors of Nature manuscripts, which are 74% and 80%, respectively. Davidson says that Nature research papers are more likely to be male-dominated (in first and last authors) than those published in other Springer Nature journals.

In an editorial published in response to the analysis, Nature acknowledges that its journalists need to work harder to eliminate biases, noting that the new analysis has shown that software can be used to recognize such trends. The editorial also mentions that Nature has been collecting data on gender diversity in its commissioned content for the last five years.

Gender bias in Physics Today

Nature is not alone in grappling with gender bias in science journalism. In an attempt to approximately replicate the Nature study’s methodology, Physics Today recorded the people quoted in 2005 and 2020 in two staff-written sections of the printed magazine: Search & Discovery, which covers new scientific research, and Issues & Events, which focuses on science policy and matters of interest to the physical sciences community.

In 2005, about 89% of quotes in those Physics Today articles were from male sources, a rate slightly more skewed than Nature ’s 87% in the same year. In 2020 the male quotation proportion was down to 74%, compared with Nature ’s 69%. Unlike in the Nature study, Physics Today did not examine the gender breakdown of the authors of journal articles in the physical sciences.

Although Physics Today is doing better than in the past, clearly there is still a lot more work to do. Physics Today ’s editors have been reaching out to more diverse sources in recent years and will continue to make those efforts a priority.

— Physics Today editors

Outside researchers say the new research, though not yet peer reviewed, is solid. Luke Holman, an evolutionary biologist at Edinburgh Napier University in the UK, says the new study has “novel, high-quality, and transparent methodology.” Holman co-authored a 2018 study that found that at the current rate of change, it would take 16 years for female researchers—averaged across scientific disciplines—to catch up with men and produce the same number of papers. In physics the gender gap would take 258 years to disappear.

Although Holman likes the new study, he notes that it doesn’t mention how many different people are quoted in each article in the sample, how many quotes are from the same sources, and how much page space is given to each source.

“It’s a really good thing that more female scientists are being quoted, even though things like this don’t normally directly contribute to tenure decisions,” says Barton Hamilton, an economist at Washington University in St Louis who has written about the gender gap in National Institutes of Health grant applications . “It’s very important that the faculty being quoted are representative of the faculty that are doing the work.”

Other analyses have also shown that women are being quoted more often in science news than in the past. For example, the World Association for Christian Communication released the latest quinquennial report on 14 July as part of the nongovernmental organization’s Global Media Monitoring Project. The report investigated, among other things, the extent to which women are quoted in the news media. Of all the news topics, women feature most often as sources and subjects in science and health news, says study editor Sarah Macharia, a consultant in gender, media, and international policy based in Toronto.

In 1995, women were 27% of the subjects and sources in science and health stories across different types of media; that representation increased to 35% by 2015. But Macharia says that as science and health news has grown as a percentage of all news coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of women as subjects and sources has decreased to 30%. “So as that topic has come to the limelight so dramatically and interest in the news has grown, women have been displaced from that space,” Macharia says.

Davidson and Greene’s study also compared quotation rates to rates of first or last authorship for scientists with various name origins in manuscripts published in Nature and other Springer Nature journals. They reported severe under-quotation relative to their rates of authorship for scientists with names originating in East Asia, and overrepresentation of scientists with English, Irish, Scottish, or Welsh names.

Deborah Blum, a science writer and director of the Knight Science Journalism program at MIT, explains that the reporter is responsible for identifying who did what in the studies they report on and for finding commenters from diverse backgrounds who did not work on the studies. “And that’s not just journalists trying to be politically correct,” she says. “When you have a diversity of scientists, the science is smarter. If you bring that to your reporting, your story is smarter too.”

But choosing diverse sources is not always easy or straightforward. Journalists often have to produce stories under tight deadlines and are sometimes limited to experts in a particular geographical location or time zone.

Holman sympathizes with the work that goes into finding sources but says, “If you have the opportunity to quote two equally qualified people and one of them is from an underrepresented part of the world or is a woman,” it’s best to quote that person.

Editor’s note: Dalmeet Singh Chawla regularly writes news pieces for Nature but had no involvement with the study. Madison Brewer performed the research for the Physics Today case study described in the box.

- Online ISSN 1945-0699

- Print ISSN 0031-9228

- For Researchers

- For Librarians

- For Advertisers

- Our Publishing Partners

- Physics Today

- Conference Proceedings

- Special Topics

pubs.aip.org

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Connect with AIP Publishing

This feature is available to subscribers only.

Sign In or Create an Account

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Brief research report article, sex and gender bias in covid-19 clinical case reports.

- 1 Department of Medical Social Sciences, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States

- 2 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, United States

- 3 Division of Biostatistics, Department of Preventive Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States

Clinical case reports circulate relevant information regarding disease presentation and describe treatment protocols, particularly for novel conditions. In the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, case reports provided key insights into the pathophysiology and sequelae associated with Covid-19 infection and described treatment mechanisms and outcomes. However, case reports are often subject to selection bias due to their singular nature. To better understand how selection biases may have influenced Covid-19-releated case reports, we conducted a bibliometric analysis of Covid-19-releated case reports published in high impact journals from January 1 to June 1, 2020. Case reports were coded for patient sex, country of institutional affiliation, physiological system, and first and last author gender. Of 494 total case reports, 45% ( n = 221) of patients were male, 30% ( n = 146) were female, and 25% ( n = 124) included both sexes. Ratios of male-only to female-only case reports varied by physiological system. The majority of case reports had male first (61%, n = 302) and last (70%, n = 340) authors. Case reports with male last authors were more likely to describe male patients [ X 2 (2, n = 465) = 6.6, p = 0.037], while case reports with female last authors were more likely to include patients of both sexes [OR = 1.918 (95% CI = 1.163–3.16)]. Despite a limited sample size, these data reflect emerging research on sex-differences in the physiological presentation and impact of Covid-19 and parallel large-scale trends in authorship patterns. Ultimately, this work highlights potential biases in the dissemination of clinical information via case reports and underscores the inextricable influences of sex and gender biases within biomedicine.

Introduction

Longstanding sex and gender biases impact many facets of the biomedical research enterprise including research practices ( 1 , 2 ), clinical care ( 3 , 4 ), and workforce development ( 5 – 7 ). The persistent overrepresentation of males as research subjects, scientists, and physicians has informed our understanding of health and disease, oftentimes to the detriment of women, transgender, and gender non-binary, or non-conforming individuals.

Clinical case reports serve as an important educational tool to disseminate pertinent information regarding disease or disorder presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis ( 8 ). During the initial months of the Covid-19 pandemic, case reports provided key insights into Covid-19 pathophysiology, sequelae, and treatment and in certain circumstances, served as primary evidence for clinical decision-making.

Case report subjects are often selected semi-retrospectively for their novelty or educational benefit. As a result, singular case reports are inherently prone to selection bias. In contrast to clinical research studies which have predefined study populations and stringent inclusion or exclusion criteria, the decision to select a case report subject may lie solely with a member of the patient's care team. However, it is reasonable to expect that if case studies were compiled for a particular disease or disorder, they would closely mirror the respective patient population. In 2017, Allotey and colleagues ( 9 ) identified a significant male bias in case reports published in high-impact medical journals, which suggests that inherent biases may play a larger role than anticipated in case report selection and publication. We hypothesized that female patients may be underrepresented in Covid-19 research and clinical care due to sex differences in Covid-19 disease or due to gender biases. To determine whether Covid-19-related case reports were, in fact, subject to sex or gender biases, we characterized 494 Covid-19-related case reports published between January 1, 2020, and July 1, 2020, from 103 journals by patient sex, physiological system, country of institutional affiliation and first and last author gender.

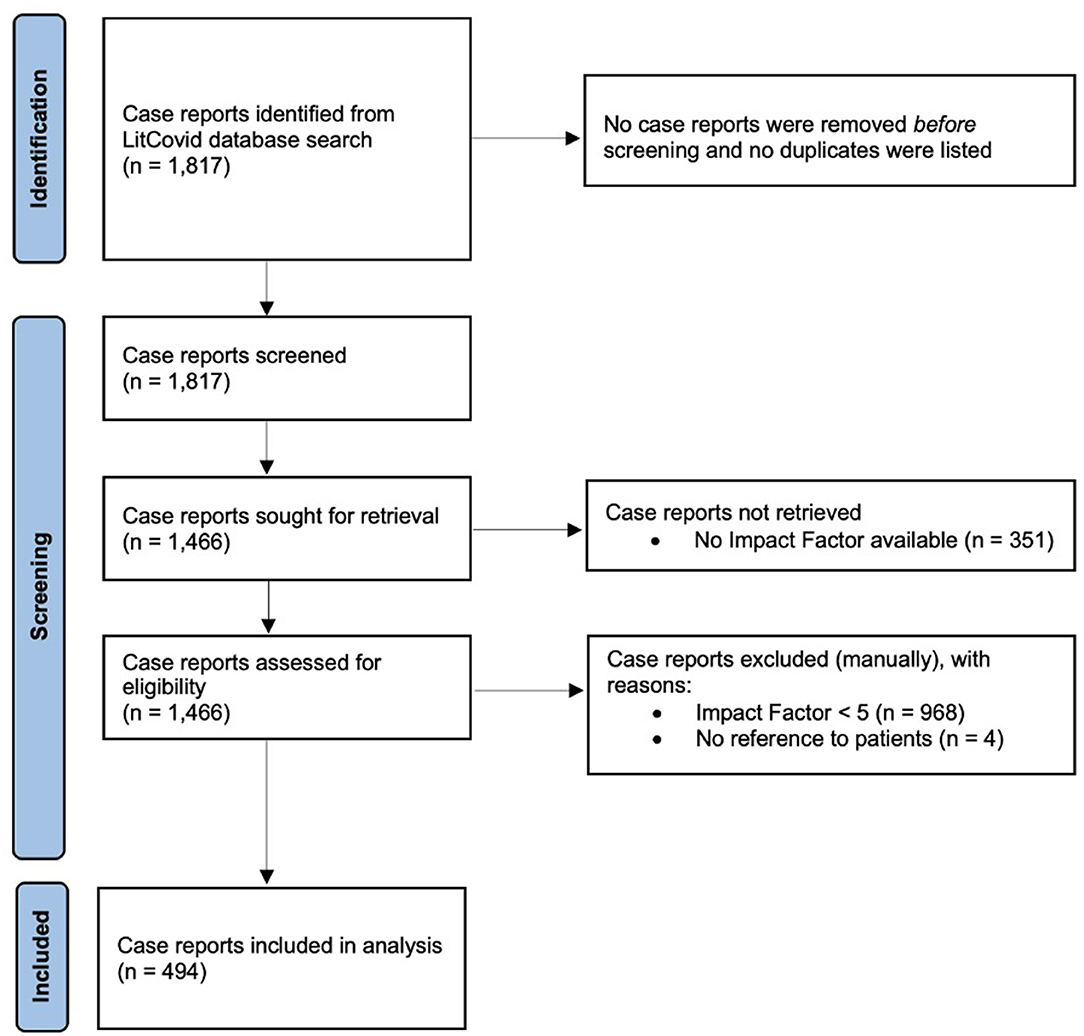

Citation data for 1,817 articles classified as case reports were downloaded on July 1, 2020, from LitCovid, a categorical database of Covid-19 literature from PubMed ( 10 , 11 ). The LitCovid database identifies relevant articles using the National Center for Biotechnology Information's E-Utilities tool which is then further refined and categorized by machine learning and manual creation ( 11 ). Case reports were further refined by additional inclusion and exclusion criteria ( Figure 1 ). Journal impact factors [(IF), 2019 Journal Citation Reports Science Edition , Clarivate Analytics] were available for 1,466 (81%) case reports, and only those with an IF of 5 or above ( n = 498, 27%) were considered medium-to-high visibility and selected for inclusion in the study and further review. Four articles were excluded because they did not reference patients, resulting in a final sample of 494 articles. Two of the authors (ASV, AO) manually and independently screened and coded case reports for patient sex, physiological system, author first names, and country of institutional affiliation. Patient sex was determined by the use of descriptive terms such as male/female, man/woman, or inferred by the use of he/she pronouns. Only one article (0.2%) included transgender patients and did not report biological sex or gender identity. The country of institutional affiliation was determined by the institutional location of the corresponding author if the article was authored by a multinational cohort. These data were cross-checked, and the coding agreement was almost perfect for a representative subset of 55 articles (Cohen's kappa = 0.97, p < 0.001). The first and last author's gender were inferred using the name-to-gender assignment algorithm Gender API ( https://gender-api.com/ ). Gender API was selected due to its low rate of inaccuracies (7.9%) or non-classifications (3%) ( 12 ). Articles authored by an unspecified group or without full first names listed were coded as unknown.

Figure 1 . Study flow diagram of the identification and screening of eligible Covid-19-related case reports retrieved from the PubMed LitCovid database.

Chi-Square tests and multinomial logistic regression models were used to examine the association between author gender and patient sex. Chi-Square tests were also used to compare patient sex by physiological system and country of institutional affiliation. Results from the multinomial logistic regression models are summarized by odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). P -values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Descriptions of patient sex or author gender follow American Psychological Association reporting standards where male/female terminology is used as descriptive adjectives when appropriate or when specifically referring to biological sex. The terms men and women are commonly used as nouns to describe groups of people.

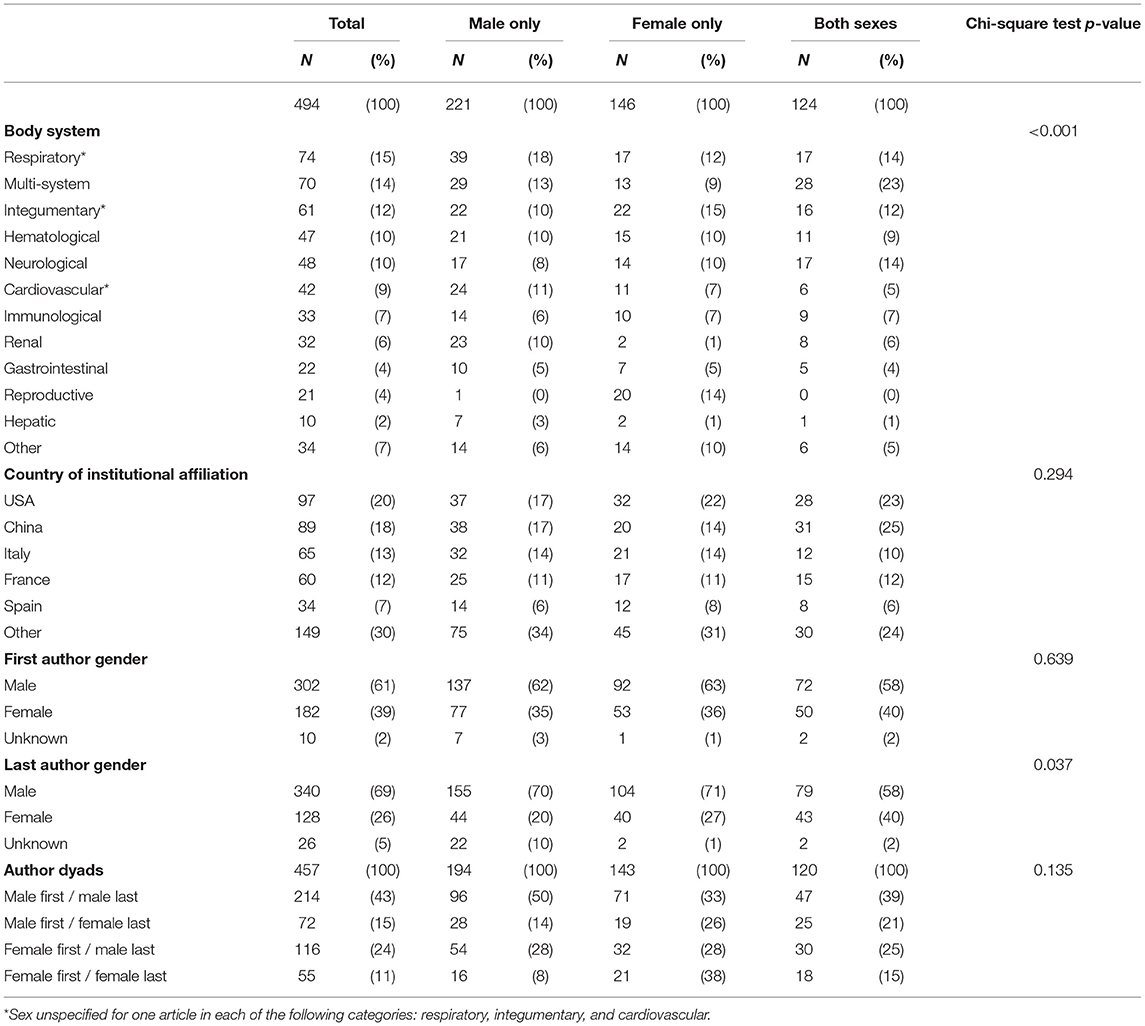

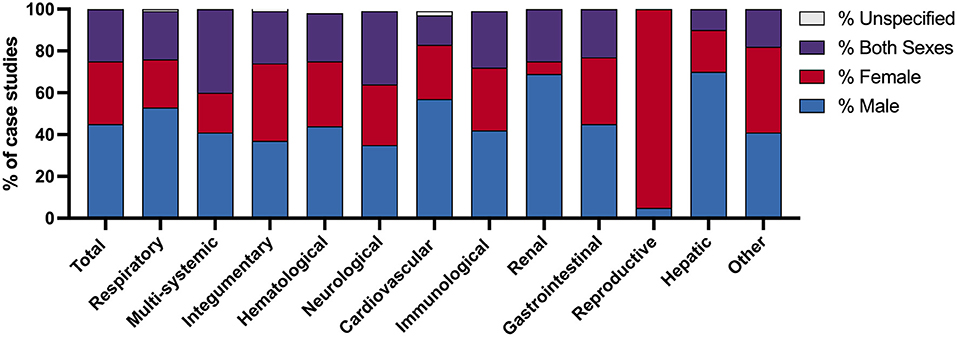

Of the 494 case reports analyzed, the majority were related to respiratory, multi-systemic, dermatologic, hematologic, or neurologic systems ( Table 1 ). Of the patients described in the 494 case reports, forty-five % ( n = 221) were male and 30% ( n = 146) were female ( Figure 2 ). Patients of both sexes were included in 25% ( n = 124) of case reports and 0.6% ( n = 3) failed to report patient sex ( Figure 1 ). The ratio of articles reporting on male-only vs. female-only patients was highest in renal (11:1), hepatic (3.5:1), respiratory (2.3:1), multi-systemic (2.2:1), and cardiovascular (2.2:1) systems. Reproductive reports were almost exclusively female (95%, n = 20).

Table 1 . Case study characteristics and article metadata.

Figure 2 . Comparison of Covid-19 case studies by patient sex and physiologic body system. The percentage of Covid-19 case studies which describe patient sex as male, female, both sexes, and unspecified. Data are presented by the category of case study, coded by physiologic body system, as well as the sum of all case studies evaluated.

Case reports were primarily authored by groups with institutional affiliations in the United States (20%, n = 97), China (18%, n = 89), Italy (13%, n = 65), France (12%, n = 60), and Spain (7%, n = 34). The majority of case reports had male first (61%, n = 302) and last (70%, n = 340) authors, with 43% ( n = 214) of all reports having male first and last author dyads. The last author's gender is associated with the sex of the case report patient ( Table 1 ). Case reports with male last authors are more likely to include male-only patients ( p = 0.037) compared to female last authors. Female last authors are more likely to include patients of both sexes [OR = 1.918 (95% CI = 1.163–3.16)] in unadjusted and adjusted models [OR = 1.774 (95% CI = 1.055–2.984)] which control for impact factor, country, and physiological system.

While male bias in case reports has been previously reported ( 9 ), this is the first study to examine this in Covid-19-related case studies. The overrepresentation of male patients in Covid-19 case reports may be reflective of sex differences in disease prevalence, severity, and immune response ( 13 , 14 ). Likewise, sex and gender differences in the presence of contributing comorbidities may also influence Covid-19 disease severity and treatment outcomes ( 15 ). The high ratio of male-to-female case reports in the renal category parallels clinical data which suggests that male sex risk factor for Covid-19-related acute kidney injury ( 15 , 16 ). In comparison, the high female-to-male ratio observed in the reproductive category can be attributed to pregnancy-related case reports. Overall, the differences in patient sex ratios across physiological categories may provide insight into Covid-19 disease mechanisms. Yet, it is important to note that these data fail to fully capture the sociocultural influences on Covid-19 testing, case identification, and access to care which may differ based on gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic location as case reports typically originate from a hospital-based setting.

Gender disparities in authorship are common within the biomedical sciences ( 17 , 18 ) and have been documented for case reports ( 19 ). In a large-scale bibliometric analysis of over 20,000 case reports, Hsiehchen and colleagues ( 19 ) found that 36% of first authors and 25% of last authors are women. The data presented here are similar with female authors comprising 39% and 26% of first and last authors, respectively. Of interest, is the unique influence of the Covid-19 pandemic on gender authorship patterns. Early in the pandemic, several groups reported that women were publishing less to biomedical preprint servers compared to the same period in 2019 ( 20 , 21 ). Meanwhile, others found that women were underrepresented as first authors on Covid-19-related research studies ( 22 , 23 ). The case reports analyzed here were authored during the first 6 months of the pandemic yet reflect pre-pandemic authorship trends. This suggests that authorship trends should not solely be used as a metric for assessing the impact of Covid-19 on research productivity and more long-term, holistic evaluations of the biomedical enterprise are warranted. In depth analyses which evaluate other metrics of productivity such as grant submission and award patterns and hiring, retention, and promotion rates, at discipline- or specialty-specific levels and the availability and/or accessibility of institutional support structures would provide added insight into the impact of Covid-19 on the biomedical workforce.

Lastly, emerging evidence suggests that author gender may also influence how data are analyzed and presented ( 24 , 25 ). Prior work by Sugimoto and colleagues found that women are more likely to report and analyze data by sex ( 25 ). Here, we find that female authors are more likely to include patients of both sexes within case reports. These data suggest that female authors may be more likely to find inherent value in including clinical data derived from both sexes in case reports. Alternatively, they may be more keenly aware of, and actively seek to address sex- and gender biases in biomedicine through inclusivity. On the contrary, case reports with male last authors were more likely to include male-only patients. As last authorship generally confers seniority and intellectual leadership, these data suggest that sex or gender biases held by the senior author, whether implicit or explicit, may influence the selection of case report patients and reporting outcomes. The male-bias observed in Covid-19 case reports may be reflective of the patient population, as men who are diagnosed with Covid-19 are more likely to require hospitalization and critical care ( 26 ), however it does not fully explain the authorial differences in case report selection. The fact that female authors are more likely to include patients of both sexes is of interest and warrants further examination particularly in disease areas which are predominantly sex-specific.

This study is not without limitations. First, the sample size of case reports analyzed was limited due to stringent inclusion criteria related to journal impact factor and date of publication; although it is important to note that this sample size remains a significant and representative subset of the original sample of case reports. Journal impact factors of 5 and above were selected to represent case reports likely to be of medium-to-high visibility within the biomedical community. However, we recognize that journal impact factors are variable across biomedical disciplines and medical specialties and serve only as one metric to assess the quality, impact, and visibility of an article. As a result, case reports published in journals related to obstetrics and gynecology and reproductive health were likely omitted due to traditionally lower impact factors. The inclusion of case reports from women's health-related journals may have made the data appear more balanced and less suggestive of a sex-bias. Yet, by excluding these articles the data more broadly reflects sex and gender biases that exist outside of sex-specific fields of medicine, although we recognize that obstetric, gynecologic, and reproductive care is provided to those who identify across the gender spectrum.

In addition, these data were collected from the first 6 months of the Covid-19 pandemic, during which time the diagnosis, treatment, and understanding of the disease were rapidly evolving. We therefore cannot quantify the potential biases associated with clinical care that occurred later in the pandemic. The in silico tools to assign author gender also present another limitation as these are currently limited to gender binary options (male, female, or unknown) and therefore exclude or misrepresent the identity of those who are gender non-binary, non-conforming, two-spirit, or third gender. Moreover, some case reports did not explicitly define patient's sex or gender. For coding purposes, patient sex for these was inferred through the use of terms such as man/woman, male/female, or descriptive he/she pronouns, and there may be instances where patient sex and gender identity do not correspond. Often the terms “sex” and “gender” were used interchangeably within case reports, making it difficult to separate patient's biological sex from their gender identity. The distinctions of both biological sex and gender should be noted in case reports, as gender is a contributing social determinant of health.

The associations between author gender and patient sex suggests that sex or gender biases are contributing factors which impact patient reporting. The coordinated efforts of clinicians, reviewers, editors, and publishers are required to ensure a balanced representation of the relevant patient population. Gender has been widely recognized as a social determinant of health and as such gender biases can contribute to gender-based health disparities. Diversification of the biomedical workforce appears to be critical, but rate-limiting factor, in reducing sex- and gender biases that permeate biomedicine. As more gender-diverse perspectives are included in the selection, writing, reviewing, and publishing of case reports, their subsequent quality, and educational value are likely to improve. Acknowledging and actively addressing biases may further a better understanding of the influences of sex and gender on health and disease, ultimately minimizing health disparities.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

NW: full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical, or material support, supervision, concept, and design. AS-V, AO, and NW: drafting of the manuscript. CY, LM, and NW: statistical analysis. All authors: acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

This work was supported by a Women's Health Access Matters Grant to NW. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Woitowich NC, Beery A, Woodruff T. A 10-year follow-up study of sex inclusion in the biological sciences. eLife . (2020) 9:e56344. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7282816/ (accessed May 18, 2021). doi: 10.7554/eLife.56344

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Shansky RM, Murphy AZ. Considering sex as a biological variable will require a global shift in science culture. Nat Neurosci. (2021) 24:457–64. doi: 10.1038/s41593-021-00806-8

3. Alcalde-Rubio L, Hernández-Aguado I, Parker LA, Bueno-Vergara E, Chilet-Rosell E. Gender disparities in clinical practice: are there any solutions? Scoping review of interventions to overcome or reduce gender bias in clinical practice. Int J Equity Health. (2020) 19:166. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01283-4

4. Hay K, McDougal L, Percival V, Henry S, Klugman J, Wurie H, et al. Disrupting gender norms in health systems: making the case for change. Lancet Lond Engl. (2019) 393:2535–49. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30648-8

5. Huang J, Gates AJ, Sinatra R, Barabási A-L. Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proc Natl Acad Sci . (2020) 117:4609–16. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914221117

6. Butkus R, Serchen J, Moyer DV, Bornstein SS, Hingle ST. Achieving gender equity in physician compensation and career advancement: a position paper of the american college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 168:721–3. doi: 10.7326/M17-3438

7. Silver JK, Bean AC, Slocum C, Poorman JA, Tenforde A, Blauwet CA. Physician workforce disparities and patient care: a narrative review. Health Equity. (2019) 3:360–77. doi: 10.1089/heq.2019.0040

8. Nissen T, Wynn R. The clinical case report: a review of its merits and limitations. BMC Res Notes. (2014) 7:264. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-264

9. Allotey P, Allotey-Reidpath C, Reidpath DD. Gender bias in clinical case reports: a cross-sectional study of the “big five” medical journals. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0177386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177386

10. Chen Q, Allot A, Lu Z. Keep up with the latest coronavirus research. Nature. (2020) 579:193. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00694-1

11. Chen Q, Allot A, Lu Z. LitCovid: an open database of COVID-19 literature. Nucleic Acids Res. (2021) 49:D1534–40. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa952

12. Santamaría L, Mihaljević H. Comparison and benchmark of name-to-gender inference services. PeerJ Comput Sci . (2018) 4:e156. doi: 10.7717/peerj-cs.156

13. Scully EP, Haverfield J, Ursin RL, Tannenbaum C, Klein SL. Considering how biological sex impacts immune responses and COVID-19 outcomes. Nat Rev Immunol. (2020) 20:442–7. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0348-8

14. Takahashi T, Iwasaki A. Sex differences in immune responses. Science. (2021) 371:347–8. doi: 10.1126/science.abe7199

15. Vahidy FS, Pan AP, Ahnstedt H, Munshi Y, Choi HA, Tiruneh Y. Sex differences in susceptibility, severity, and outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019: Cross-sectional analysis from a diverse US metropolitan area. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0245556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245556

16. Zahid U, Ramachandran P, Spitalewitz S, Alasadi L, Chakraborti A, Azhar M. Acute Kidney Injury in COVID-19 Patients: an inner city hospital experience and policy implications. Am J Nephrol. (2020) 51:786–96. doi: 10.1159/000511160

17. Filardo G, da Graca B, Sass DM, Pollock BD, Smith EB, et al. Trends and comparison of female first authorship in high impact medical journals: observational study (1994-2014). BMJ . (2016) 352:i847. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i847

18. Kleijn de, Jayabalasingham M, Falk-Krzesinski B, Collins H, Kupier-Hoyng T, Cingolani LI, et al. The Researcher Journey Through a Gender Lens: An Examination of Research Participation, Career Progression and Perceptions Across the Globe. Elsevier (2020). Available online at: http://www.elsevier.com/gender-report (accessed May 19, 2021).

19. Hsiehchen D, Hsieh A, Espinoza M. Prevalence of female authors in case reports published in the medical literature. JAMA Netw Open. (2019) 2:e195000. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5000

20. Vincent-Lamarre P, Sugimoto C, Larivière V. The Decline Of Women's Research Production During The Coronavirus Pandemic. Nature Index (2020). Available online at: https://www.natureindex.com/news-blog/decline-women-scientist-research-publishing-production-coronavirus-pandemic (accessed May 19, 2021).

21. Wehner MR, Li Y, Nead KT. Comparison of the proportions of female and male corresponding authors in preprint research repositories before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open . (2020) 3:1–4. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20335

22. Andersen JP, Nielsen MW, Simone NL, Lewiss RE, Jagsi R. COVID-19 medical papers have fewer women first authors than expected. eLife. (2020) 9:e58807. doi: 10.7554/eLife.58807

23. Lerchenmüller C, Schmallenbach L, Jena AB, Lerchenmueller MJ. Longitudinal analyses of gender differences in first authorship publications related to COVID-19. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e045176. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045176

24. Nielsen MW, Andersen JP, Schiebinger L, Schneider JW. One and a half million medical papers reveal a link between author gender and attention to gender and sex analysis. Nat Hum Behav. (2017) 1:791–6. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0235-x

25. Sugimoto CR, Ahn Y-Y, Smith E, Macaluso B, Larivière V. Factors affecting sex-related reporting in medical research: a cross-disciplinary bibliometric analysis. Lancet . (2019) 393:550–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32995-7

26. Gomez JMD, Du-Fay-de-Lavallaz JM, Fugar S, Sarau A, Simmons JA, Sanghani RM, et al. Sex Differences in COVID-19 Hospitalization and Mortality. J Womens Health (Larchmt). (2021) 30:646–53. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8948

Keywords: COVID-19, sex bias, gender bias, case reports (publication type), bibliometrics

Citation: Salter-Volz AE, Oyasu A, Yeh C, Muhammad LN and Woitowich NC (2021) Sex and Gender Bias in Covid-19 Clinical Case Reports. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2:774033. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2021.774033

Received: 10 September 2021; Accepted: 29 October 2021; Published: 22 November 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Salter-Volz, Oyasu, Yeh, Muhammad and Woitowich. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicole C. Woitowich, nicole.woitowich@northwestern.edu

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

This article is part of the Research Topic

Inequalities in COVID-19 Healthcare and Research Affecting Women

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 04 Mar 2024

- Research & Ideas

Want to Make Diversity Stick? Break the Cycle of Sameness

Whether on judicial benches or in corporate boardrooms, white men are more likely to step into roles that other white men vacate, says research by Edward Chang. But when people from historically marginalized groups land those positions, workforce diversification tends to last. Chang offers three pieces of advice for leaders striving for diversity.

- 14 Sep 2023

Working Moms Are Mostly Thriving Again. Can We Finally Achieve Gender Parity?

The pandemic didn't destroy the workplace advancements moms had achieved. However, not all of the positive changes forced by the crisis and remote work have stuck, says research by Kathleen McGinn and Alexandra Feldberg.

- 26 Jul 2023

STEM Needs More Women. Recruiters Often Keep Them Out

Tech companies and programs turn to recruiters to find top-notch candidates, but gender bias can creep in long before women even apply, according to research by Jacqueline Ng Lane and colleagues. She highlights several tactics to make the process more equitable.

- 18 Jul 2023

- Cold Call Podcast

Diversity and Inclusion at Mars Petcare: Translating Awareness into Action

In 2020, the Mars Petcare leadership team found themselves facing critically important inclusion and diversity issues. Unprecedented protests for racial justice in the U.S. and across the globe generated demand for substantive change, and Mars Petcare's 100,000 employees across six continents were ready for visible signs of progress. How should Mars’ leadership build on their existing diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts and effectively capitalize on the new energy for change? Harvard Business School associate professor Katherine Coffman is joined by Erica Coletta, Mars Petcare’s chief people officer, and Ibtehal Fathy, global inclusion and diversity officer at Mars Inc., to discuss the case, “Inclusion and Diversity at Mars Petcare.”

- 03 Mar 2023

When Showing Know-How Backfires for Women Managers

Women managers might think they need to roll up their sleeves and work alongside their teams to show their mettle. But research by Alexandra Feldberg shows how this strategy can work against them. How can employers provide more support?

- 31 Jan 2023

Addressing Racial Discrimination on Airbnb

For years, Airbnb gave hosts extensive discretion to accept or reject a guest after seeing little more than a name and a picture, believing that eliminating anonymity was the best way for the company to build trust. However, the apartment rental platform failed to track or account for the possibility that this could facilitate discrimination. After research published by Professor Michael Luca and others provided evidence that Black hosts received less in rent than hosts of other races and showed signs of discrimination against guests with African American sounding names, the company had to decide what to do. In the case, “Racial Discrimination on Airbnb,” Luca discusses his research and explores the implication for Airbnb and other platform companies. Should they change the design of the platform to reduce discrimination? And what’s the best way to measure the success of any changes?

- 03 Jan 2023

Confront Workplace Inequity in 2023: Dig Deep, Build Bridges, Take Collective Action

Power dynamics tied up with race and gender underlie almost every workplace interaction, says Tina Opie. In her book Shared Sisterhood, she offers three practical steps for dismantling workplace inequities that hold back innovation.

- 29 Nov 2022

How Will Gamers and Investors Respond to Microsoft’s Acquisition of Activision Blizzard?

In January 2022, Microsoft announced its acquisition of the video game company Activision Blizzard for $68.7 billion. The deal would make Microsoft the world’s third largest video game company, but it also exposes the company to several risks. First, the all-cash deal would require Microsoft to use a large portion of its cash reserves. Second, the acquisition was announced as Activision Blizzard faced gender pay disparity and sexual harassment allegations. That opened Microsoft up to potential reputational damage, employee turnover, and lost sales. Do the potential benefits of the acquisition outweigh the risks for Microsoft and its shareholders? Harvard Business School associate professor Joseph Pacelli discusses the ongoing controversies around the merger and how gamers and investors have responded in the case, “Call of Fiduciary Duty: Microsoft Acquires Activision Blizzard.”

- 10 Nov 2022

Too Nice to Lead? Unpacking the Gender Stereotype That Holds Women Back

People mistakenly assume that women managers are more generous and fair when it comes to giving money, says research by Christine Exley. Could that misperception prevent companies from shrinking the gender pay gap?

- 08 Nov 2022

How Centuries of Restrictions on Women Shed Light on Today's Abortion Debate

Going back to pre-industrial times, efforts to limit women's sexuality have had a simple motive: to keep them faithful to their spouses. Research by Anke Becker looks at the deep roots of these restrictions and their economic implications.

- 01 Nov 2022

Marie Curie: A Case Study in Breaking Barriers

Marie Curie, born Maria Sklodowska from a poor family in Poland, rose to the pinnacle of scientific fame in the early years of the twentieth century, winning the Nobel Prize twice in the fields of physics and chemistry. At the time women were simply not accepted in scientific fields so Curie had to overcome enormous obstacles in order to earn a doctorate at the Sorbonne and perform her pathbreaking research on radioactive materials. How did she plan her time and navigate her life choices to leave a lasting impact on the world? Professor Robert Simons discusses how Marie Curie rose to scientific fame despite poverty and gender barriers in his case, “Marie Curie: Changing the World.”

- 18 Oct 2022

When Bias Creeps into AI, Managers Can Stop It by Asking the Right Questions

Even when companies actively try to prevent it, bias can sway algorithms and skew decision-making. Ayelet Israeli and Eva Ascarza offer a new approach to make artificial intelligence more accurate.

- 29 Jul 2022

Will Demand for Women Executives Finally Shrink the Gender Pay Gap?

Women in senior management have more negotiation power than they think in today's labor market, says research by Paul Healy and Boris Groysberg. Is it time for more women to seek better opportunities and bigger pay?

- 24 May 2022

Career Advice for Minorities and Women: Sharing Your Identity Can Open Doors

Women and people of color tend to minimize their identities in professional situations, but highlighting who they are often forces others to check their own biases. Research by Edward Chang and colleagues.

- 08 Mar 2022

Representation Matters: Building Case Studies That Empower Women Leaders

The lessons of case studies shape future business leaders, but only a fraction of these teaching tools feature women executives. Research by Colleen Ammerman and Boris Groysberg examines the gender gap in cases and its implications. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 22 Feb 2022

Lack of Female Scientists Means Fewer Medical Treatments for Women

Women scientists are more likely to develop treatments for women, but many of their ideas never become inventions, research by Rembrand Koning says. What would it take to make innovation more equitable? Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 01 Sep 2021

How Women Can Learn from Even Biased Feedback

Gender bias often taints performance reviews, but applying three principles can help women gain meaningful insights, says Francesca Gino. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 23 Jun 2021

One More Way the Startup World Hampers Women Entrepreneurs

Early feedback is essential to launching new products, but women entrepreneurs are more likely to receive input from men. Research by Rembrand Koning, Ramana Nanda, and Ruiqing Cao. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 01 Jun 2021

- What Do You Think?

Are Employers Ready for a Flood of 'New' Talent Seeking Work?

Many people, particularly women, will be returning to the workforce as the COVID-19 pandemic wanes. What will companies need to do to harness the talent wave? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 10 May 2021

Who Has Potential? For Many White Men, It’s Often Other White Men

Companies struggling to build diverse, inclusive workplaces need to break the cycle of “sameness” that prevents some employees from getting an equal shot at succeeding, says Robin Ely. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

Insights From Research of Teens Unhappy With Their Gender

New studies offer critical data on teens questioning their gender..

Posted April 26, 2024 | Reviewed by Tyler Woods

- Objective information is lacking about basic demographics of adolescents unhappy with their gender.

- Two new studies reveal a sizable number of early adolescents experience dissatisfaction with their gender.

- While most teens become content with their birth gender as they grow up, some remain unsatisfied.

In the landscape of contemporary gender discourse, few topics evoke as much controversy as those concerning transgender issues. From discussions about restroom access to debates surrounding sports participation, the dialogue is fraught with polarization. These discussions often descend into heated exchanges, characterized more by accusations and counteraccusations than reasoned engagement.

Amidst the fervor and impassioned opinions, one crucial element remains conspicuously absent: concrete and objective information. Consequently, our conversations about transgender controversies frequently falter in addressing fundamental inquiries. We even don’t have basic statistics and demographics of the transgender community.

Fortunately, two recent studies have proved timely, shedding new light and offering fresh perspectives on these complex issues.

In a study published in 2021, Jen-How Kuo and Meng-Che Tsai led a team in tracking 1,806 junior high students in Taiwan from 2000 to 2009. They asked a straightforward question: “Are you satisfied with your own gender?” What they found over the nine-year period was quite telling: while the majority (86.5 percent) consistently expressed satisfaction with their genders, 7.8 percent transitioned from dissatisfaction to satisfaction, 4.8 percent shifted from satisfaction to dissatisfaction, and 0.9 percent remained consistently dissatisfied ( 1 ).

A similar study in the Netherlands, detailed in a 2024 paper by Pien Rawee, Sarah Burke, and their colleagues, queried 2,772 adolescents in their response to a similar but more nuanced statement: “I wish to be of the opposite sex .” They discovered that as many as 11 percent of early adolescents experienced gender dissatisfaction, which decreased to approximately 4 percent by the age of 25. Overall, 78 percent remained content with their genders, 19 percent transitioned from dissatisfaction to satisfaction, and 2 percent became even more dissatisfied with their birth genders as they progressed from early adolescence to young adulthood ( 2 ).

These findings hold critical significance on several fronts. First, they reveal that a sizable percentage (13.5 percent in the Taiwan study and 22 percent in the Netherlands study) of teenagers experience some level of dissatisfaction with their gender identity . However, most of them tend to resolve this uncertainty as they mature into adulthood, ultimately aligning with the gender they were assigned at birth. Nonetheless, there remains a smaller yet consistent portion of teenagers who persist in their dissatisfaction or even transition from a state of contentment to dissatisfaction with their gender identity .

“These findings indicate,” write the researchers from the Taiwan study, “that healthcare professionals should concentrate on gender non-conforming individuals at early adolescence, navigating them toward a healthy adulthood.” Clearly, they are also significant for parents, caregivers, and society at large, providing guidance on how to better care for, assist, and support adolescents, especially those prone to gender dissatisfaction.

Undoubtedly, the next crucial question revolves around identifying which adolescents will navigate out of the phase of gender uncertainty and who will persist in their dissatisfaction. While such data is currently lacking, an evidence-based approach holds the promise of transcending ideological debate to a scientific endeavor in developmental psychology.

Acknowledgments: I thank Drs. Sarah Burke and Meng-Che Tsai for double-checking the facts quoted in this essay based on their original research.

1. Kuo, J-H., Albaladejo Carrera, R., Cendra Mulyani, L., Strong, C., Lin, Y-C., Hsieh, Y-P., Tsai, M-C., and Lin, C-Y. (2021) Exploring the Interaction Effects of Gender Contentedness and Pubertal Timing on Adolescent Longitudinal Psychological and Behavioral Health Outcomes. Front. Psychiatry 12:660746.

2. Rawee, P., Rosmalen, J.G., Kalverdijk, L., and Burke, S.M. (2024) Development of Gender Non-Contentedness During Adolescence and Early Adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, pp.1-13.

Lixing Sun, Ph.D. , is a distinguished research professor in behavior and evolution at Central Washington University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Assessing gender bias in machine translation: a case study with Google Translate

- Original Article

- Published: 27 March 2019

- Volume 32 , pages 6363–6381, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Marcelo O. R. Prates ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5576-7060 1 ,

- Pedro H. Avelar 1 &

- Luís C. Lamb 1

11k Accesses

95 Citations

65 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

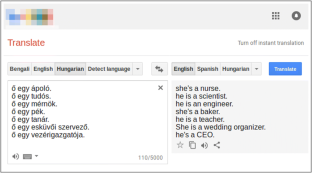

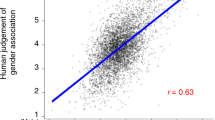

Recently there has been a growing concern in academia, industrial research laboratories and the mainstream commercial media about the phenomenon dubbed as machine bias , where trained statistical models—unbeknownst to their creators—grow to reflect controversial societal asymmetries, such as gender or racial bias. A significant number of Artificial Intelligence tools have recently been suggested to be harmfully biased toward some minority, with reports of racist criminal behavior predictors, Apple’s Iphone X failing to differentiate between two distinct Asian people and the now infamous case of Google photos’ mistakenly classifying black people as gorillas. Although a systematic study of such biases can be difficult, we believe that automated translation tools can be exploited through gender neutral languages to yield a window into the phenomenon of gender bias in AI. In this paper, we start with a comprehensive list of job positions from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and used it in order to build sentences in constructions like “He/She is an Engineer” (where “Engineer” is replaced by the job position of interest) in 12 different gender neutral languages such as Hungarian, Chinese, Yoruba, and several others. We translate these sentences into English using the Google Translate API, and collect statistics about the frequency of female, male and gender neutral pronouns in the translated output. We then show that Google Translate exhibits a strong tendency toward male defaults, in particular for fields typically associated to unbalanced gender distribution or stereotypes such as STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) jobs. We ran these statistics against BLS’ data for the frequency of female participation in each job position, in which we show that Google Translate fails to reproduce a real-world distribution of female workers. In summary, we provide experimental evidence that even if one does not expect in principle a 50:50 pronominal gender distribution, Google Translate yields male defaults much more frequently than what would be expected from demographic data alone. We believe that our study can shed further light on the phenomenon of machine bias and are hopeful that it will ignite a debate about the need to augment current statistical translation tools with debiasing techniques—which can already be found in the scientific literature.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Gender Bias in Machine Translation Systems

Gender and Age Bias in Commercial Machine Translation

Gender stereotypes are reflected in the distributional structure of 25 languages

Angwin J, Larson J, Mattu S, Kirchner L (2016) Machine bias: there’s software used across the country to predict future criminals and it’s biased against blacks. https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing . Last visited 2017-12-17

Bahdanau D, Cho K, Bengio Y (2014) Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arxiv:1409.0473 . Accessed 9 Mar 2019

Bellens E (2018) Google translate est sexiste. https://datanews.levif.be/ict/actualite/google-translate-est-sexiste/article-normal-889277.html?cookie_check=1549374652 . Posted 11 Sep 2018

Boitet C, Blanchon H, Seligman M, Bellynck V (2010) MT on and for the web. In: 2010 International conference on natural language processing and knowledge engineering (NLP-KE), IEEE, pp 1–10

Bolukbasi T, Chang KW, Zou JY, Saligrama V, Kalai AT (2016) Man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker? Debiasing word embeddings. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 29: annual conference on neural information processing systems 2016, December 5–10. Barcelona, Spain, pp 4349–4357

Boroditsky L, Schmidt LA, Phillips W (2003) Sex, syntax, and semantics. In: Getner D, Goldin-Meadow S (eds) Language in mind: advances in the study of language and thought. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 61–79

Google Scholar

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2017) Table 11: employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 2017. Labor force statistics from the current population survey, United States Department of Labor, Washington D.C

Carl M, Way A (2003) Recent advances in example-based machine translation, vol 21. Springer, Berlin

Book MATH Google Scholar

Chomsky N (2011) The golden age: a look at the original roots of artificial intelligence, cognitive science, and neuroscience (partial transcript of an interview with N. Chomsky at MIT150 Symposia: Brains, minds and machines symposium). https://chomsky.info/20110616/ . Last visited 26 Dec 2017

Clauburn T (2018) Boffins bash Google Translate for sexism. https://www.theregister.co.uk/2018/09/10/boffins_bash_google_translate_for_sexist_language/ . Posted 10 Sep 2018

Dascal M (1982) Universal language schemes in England and France, 1600–1800 comments on James Knowlson. Studia leibnitiana 14(1):98–109

Diño G (2019) He said, she said: addressing gender in neural machine translation. https://slator.com/technology/he-said-she-said-addressing-gender-in-neural-machine-translation/ . Posted 22 Jan 2019

Dryer MS, Haspelmath M (eds) (2013) WALS online. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig

Firat O, Cho K, Sankaran B, Yarman-Vural FT, Bengio Y (2017) Multi-way, multilingual neural machine translation. Comput Speech Lang 45:236–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csl.2016.10.006

Article Google Scholar

Garcia M (2016) Racist in the machine: the disturbing implications of algorithmic bias. World Policy J 33(4):111–117

Google: language support for the neural machine translation model (2017). https://cloud.google.com/translate/docs/languages#languages-nmt . Last visited 19 Mar 2018

Gordin MD (2015) Scientific Babel: how science was done before and after global English. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Book Google Scholar

Hajian S, Bonchi F, Castillo C (2016) Algorithmic bias: from discrimination discovery to fairness-aware data mining. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, ACM, pp 2125–2126

Hutchins WJ (1986) Machine translation: past, present, future. Ellis Horwood, Chichester

Johnson M, Schuster M, Le QV, Krikun M, Wu Y, Chen Z, Thorat N, Viégas FB, Wattenberg M, Corrado G, Hughes M, Dean J (2017) Google’s multilingual neural machine translation system: enabling zero-shot translation. TACL 5:339–351

Kay P, Kempton W (1984) What is the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis? Am Anthropol 86(1):65–79

Kelman S (2014) Translate community: help us improve google translate!. https://search.googleblog.com/2014/07/translate-community-help-us-improve.html . Last visited 12 Mar 2018

Kirkpatrick K (2016) Battling algorithmic bias: how do we ensure algorithms treat us fairly? Commun ACM 59(10):16–17

Knebel P (2019) Nós, os robôs e a ética dessa relação. https://www.jornaldocomercio.com/_conteudo/cadernos/empresas_e_negocios/2019/01/665222-nos-os-robos-e-a-etica-dessa-relacao.html . Posted 4 Feb 2019

Koehn P (2009) Statistical machine translation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Koehn P, Hoang H, Birch A, Callison-Burch C, Federico M, Bertoldi N, Cowan B, Shen W, Moran C, Zens R, Dyer C, Bojar O, Constantin A, Herbst E (2007) Moses: open source toolkit for statistical machine translation. In: ACL 2007, Proceedings of the 45th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics, June 23–30, 2007, Prague, Czech Republic. http://aclweb.org/anthology/P07-2045 . Accessed 9 Mar 2019

Locke WN, Booth AD (1955) Machine translation of languages: fourteen essays. Wiley, New York

MATH Google Scholar

Mills KA (2017) ’Racist’ soap dispenser refuses to help dark-skinned man wash his hands—but Twitter blames ’technology’. http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/racist-soap-dispenser-refuses-help-11004385 . Last visited 17 Dec 2017

Moss-Racusin CA, Molenda AK, Cramer CR (2015) Can evidence impact attitudes? Public reactions to evidence of gender bias in stem fields. Psychol Women Q 39(2):194–209

Norvig P (2017) On Chomsky and the two cultures of statistical learning. http://norvig.com/chomsky.html . Last visited 17 Dec 2017

Olson P (2018) The algorithm that helped Google Translate become sexist. https://www.forbes.com/sites/parmyolson/2018/02/15/the-algorithm-that-helped-google-translate-become-sexist/#1c1122c27daa . Last visited 12 Mar 2018

Papenfuss M (2017) Woman in China says colleague’s face was able to unlock her iPhone X. http://www.huffpostbrasil.com/entry/iphone-face-recognition-double_us_5a332cbce4b0ff955ad17d50 . Last visited 17 Dec 2017

Rixecker K (2018) Google Translate verstärkt sexistische vorurteile. https://t3n.de/news/google-translate-verstaerkt-sexistische-vorurteile-1109449/ . Posted 11 Sep 2018

Santacreu-Vasut E, Shoham A, Gay V (2013) Do female/male distinctions in language matter? Evidence from gender political quotas. Appl Econ Lett 20(5):495–498

Schiebinger L (2014) Scientific research must take gender into account. Nature 507(7490):9

Shankland S (2017) Google Translate now serves 200 million people daily. https://www.cnet.com/news/google-translate-now-serves-200-million-people-daily/ . Last visited 12 Mar 2018

Thompson AJ (2014) Linguistic relativity: can gendered languages predict sexist attitudes?. Linguistics Department, Montclair State University, Montclair

Wang Y, Kosinski M (2018) Deep neural networks are more accurate than humans at detecting sexual orientation from facial images. J Personal Soc Psychol 114(2):246–257

Weaver W (1955) Translation. In: Locke WN, Booth AD (eds) Machine translation of languages, vol 14. Technology Press, MIT, Cambridge, pp 15–23. http://www.mt-archive.info/Weaver-1949.pdf . Last visited 17 Dec 2017

Women’s Bureau – United States Department of Labor (2017) Traditional and nontraditional occupations. https://www.dol.gov/wb/stats/nontra_traditional_occupations.htm . Last visited 30 May 2018

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001 and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

Marcelo O. R. Prates, Pedro H. Avelar & Luís C. Lamb

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Marcelo O. R. Prates .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Prates, M.O.R., Avelar, P.H. & Lamb, L.C. Assessing gender bias in machine translation: a case study with Google Translate. Neural Comput & Applic 32 , 6363–6381 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-019-04144-6

Download citation

Received : 19 October 2018

Accepted : 09 March 2019

Published : 27 March 2019

Issue Date : May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-019-04144-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Machine bias

- Gender bias

- Machine learning

- Machine translation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Browse Course Material

Course info, instructors.

- Dr. Richard Fletcher

- Prof. Daniel Frey

- Dr. Mike Teodorescu

- Amit Gandhi

- Audace Nakeshimana

Departments

- Supplemental Resources

As Taught In

- Artificial Intelligence

- Curriculum and Teaching

Learning Resource Types

Exploring fairness in machine learning for international development, case study with data: mitigating gender bias on the uci adult database.

- Download video

- Download transcript

Mitigating Gender Bias slides (PDF - 1.6MB)

Learning Objectives

- Explore steps and principles involved in building less-biased machine learning modules.

- Explore two classes of technique, data-based and model-based techniques for mitigating bias in machine learning.

- Apply these techniques to the UCI adult dataset.

The repository for this module can be found at Github - ML Bias Fairness .

Defining algorithmic/model bias

Bias or algorithmic bias will be defined as systematic errors in an algorithm/model that can lead to potentially unfair outcomes.

Bias can be quantified by looking at discrepancies in the model error rate for different populations.

UCI adult dataset

The UCI adult dataset is a widely cited dataset used for machine learning modeling. It includes over 48,000 data points extracted from the 1994 census data in the United States. Each data point has 15 features, including age, education, occupation, sex, race, and salary, among others.

The dataset has twice as many men as women. Additionally, the data shows income discrepancies across genders. Approximately 1 in 3 of men are reported to make over $50K, whereas only 1 in 5 women are reported to make the same amount. For high salaries, the number of data points in the male population is significantly higher than the number of data points in the female category.

Preparing data

In order to prepare the data for machine learning, we will explore different steps involved in transforming data from raw representation to appropriate numerical or categorical representation. One example is converting native country to binary, representing individuals whose native country was the US as 0 and individuals whose native country was not the US as 1. Similar representations need to be made for other attributes such as sex and salary. One-hot encoding can be used for attributes where more than two choices are possible.

Binary coding was chosen for simplicity, but this decision must be made on a case-by-case basis. Converting features like work class can be problematic if individuals from different categories have systematically different levels of income. However, not doing this can also be problematic if one category has a population that is too small to generalize from.

Illustrating gender bias

We apply the standard ML approach to the UCI adult dataset. The steps that are followed are 1) splitting the dataset into training and test data, 2) selecting model (MLPClassifier in this case), 3) fitting the model on training data, and 4) using the model to make predictions on test data. For this application, we will define the positive category to mean high income (>$50K/year) and the negative category to mean low income (<=$50K/year).

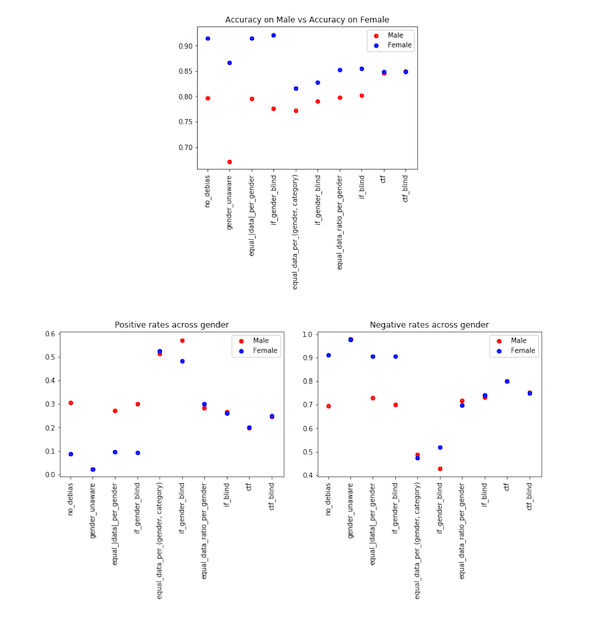

The model results show that the positive rates and true positive rates are higher for the male demographic. Additionally, the negative rate and true negative rates are higher for the female demographic. This shows consistent disparities in the error rates between the two demographics, which we will define as gender bias.

Exploring data-based debiasing techniques

We hypothesize that gender bias could come from unequal representation of male and female demographics. We attempt to re-calibrate and augment the dataset to equalize the gender representation in our training data. We will explore the following techniques and their outcomes. We will compare the results after describing each approach.

Debiasing by unawareness: we drop the gender attribute from the model so that the algorithm is unaware of an individual’s gender. Although the discrepancy in overall accuracy does not change, the positive, negative, true positive, and true negative rates are much closer for the male and female demographics.

Equalizing the number of data points: we attempt different approaches to equalizing the representation. The different equalization criteria are #male = #female, #high income male = #high income female, #high income male/#low income male = #high income female/#low income female. One of the disadvantages of equalizing the number of data points is that the dataset size is limited by the size of the smallest demographic. Equalizing the ratio can overcome this limitation.

Augment data with counterfactuals: for each data point X i with a given gender, we generate a new data point Y i that only differs with X i at the gender attribute and add it to our dataset. The gaps between male and female demographics are significantly reduced through this approach.

We see varying accuracy across different approaches on accuracy for the male and female demographics, as shown in the plot below. The counterfactual approach is shown to be the best at reducing gender bias. We see similar behavior for the positive rates and negative rates as well as the true positive and true negative rates.

Model-based debiasing techniques

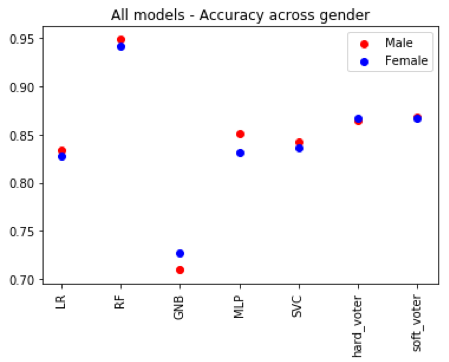

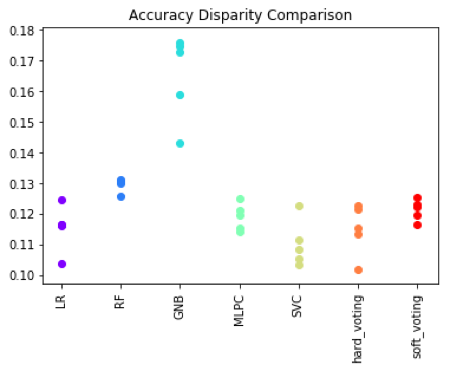

Different ML models show different levels of bias. By changing the model type and architecture, we can observe which ones will be less biased for this application. We examine single and multi-model architectures. The models that will be considered are support vector, random forest, KNN, logistic regression, and MLP classifiers. Multi-model architectures involve training a group of different models that make a final prediction based on consensus. Two approaches can be used for consensus; hard voting, where the final prediction is the majority prediction among the models and soft voting, where the final prediction is the average prediction. The following plots show the differences in overall accuracy and the discrepancies between accuracy across gender.

It is also important to compare the results of the models across multiple training sessions. For each model type, five instances of the model were trained and compared. Results are shown the plot below. We can see that different models have different variability in performance for different metrics of interest.

Dua, D. and Graff, C. (2019). UCI Machine Learning Repository . Irvine, CA: University of California, School of Information and Computer Science.

Bishop, Christopher M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning . New York: Springer 2006. ISBN: 9780387310732.

Hardt, Moritz. (2016, October 7). “ Equality of opportunity in machine learning .” Google AI Blog .

Zhong, Ziyuan. (2018, October 21). “ A tutorial on fairness in machine learning .” Toward Data Science .

Kun, Jeremy. (2015, October 19). “ One definition of algorithmic fairness: statistical parity .”

Olteanu, Alex. (2018, January 3). “ Tutorial: Learning curves for machine learning in Python .” DataQuest .

Garg, Sahaj, et al. 2018. “ Counterfactual fairness in text classification through robustness .” arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.10610.

Wikipedia contributors. (2019, September 6). “ Algorithmic bias .” In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia .

Contributions

Content presented by Audace Nakeshimana (MIT).

This content was created by Audace Nakeshimana and Maryam Najafian (MIT).

You are leaving MIT OpenCourseWare

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 26 January 2022

Gender and feminist considerations in artificial intelligence from a developing-world perspective, with India as a case study

- Shailendra Kumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7493-5496 1 &

- Sanghamitra Choudhury ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1417-1735 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 31 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

5 Citations

30 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Complex networks

- Development studies

- Information systems and information technology

- Science, technology and society

This manuscript discusses the relationship between women, technology manifestation, and likely prospects in the developing world. Using India as a case study, the manuscript outlines how Artificial Intelligence (AI) and robotics affect women’s opportunities in developing countries. Women in developing countries, notably in South Asia, are perceived as doing domestic work and are underrepresented in high-level professions. They are disproportionately underemployed and face prejudice in the workplace. The purpose of this study is to determine if the introduction of AI would exacerbate the already precarious situation of women in the developing world or if it would serve as a liberating force. While studies on the impact of AI on women have been undertaken in developed countries, there has been less research in developing countries. This manuscript attempts to fill that need.

Similar content being viewed by others

Importance and limitations of AI ethics in contemporary society

The impact of artificial intelligence on employment: the role of virtual agglomeration, towards a new generation of artificial intelligence in china, introduction.

Women in some South-Asian countries, like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan face significant hardships and problems, ranging from human trafficking to gender discrimination. Compared to their counterparts in developed countries, developing-world women encounter a biased atmosphere. Many South Asian countries have a patriarchal and male-dominated society, and their culture has a strong preference for male offspring (Kristof, 1993 ; Bhalotra et al., 2020 ; Oomman and Ganatra, 2002 ). These countries, particularly India, have experienced instances where technology has been utilized to create gender bias (Guilmoto, 2015 ). For example, there has been a great misuse of some of the techniques, of which sonography, or ultrasound , is one. The public misappropriated sonography , which was intended to determine the unborn’s health select the fetus’s gender, and perform an abortion if the fetus is female (Alkaabi et al., 2007 ; Akbulut-Yuksel and Rosenblum, 2012 ; Bowman-Smart et al., 2020 ). Many Indian states, particularly the northern states of India, have seen a significant drop in the sex ratio due to this erroneous use of technology. India’s unbalanced child sex ratio has rapidly deteriorated. In 1981, there were 962 females in the 0–6-year age group for every 1000 boys. In 1991, there were 945 girls, then 927 girls in 2001, and 918 girls at the time of the 2011 Census (Bose, 2011 ; Hu and Schlosser, 2012 ). In 1994, the Indian government passed the Pre-conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act to halt this trend. The law made it unlawful for medical practitioners to divulge the sex of a fetus due to worries that ultrasound technology was being used to detect the sex of the unborn child and terminate the female fetus (Nidadavolu and Bracken, 2006 ; Ahankari et al., 2015 ). However, as the Indian Census data over the years demonstrates, the law did not operate as well as intended. According to public health campaigners, this is due to the Indian government’s failure to enforce the law effectively; sex determination and female feticide continue due to medical practitioners’ lack of oversight. Radiologists and gynecologists, on the other hand, argue that it’s because the law was misguided from the outset, holding the medical profession responsible for a societal problem (Tripathi, 2016 ).

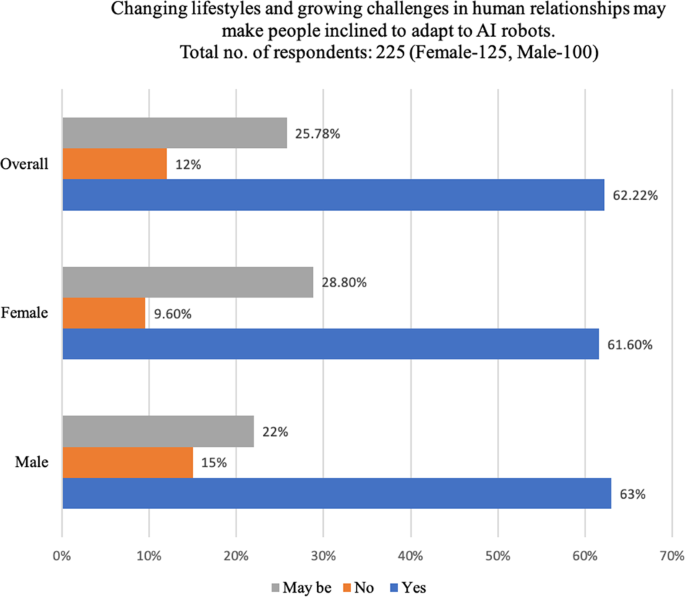

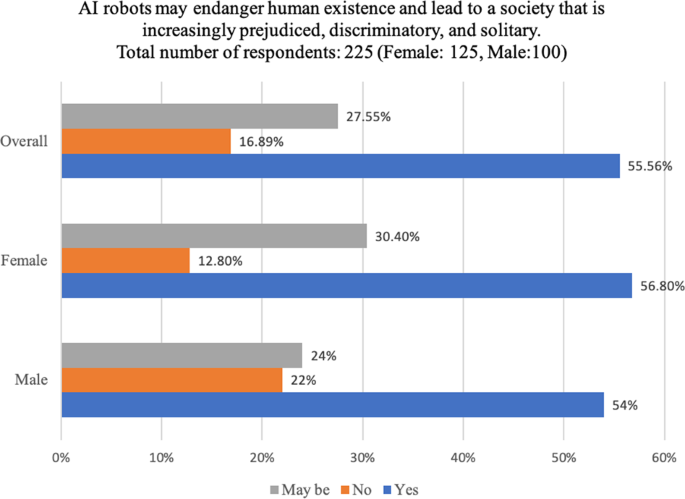

In the realm of artificial intelligence, gender imbalance is a critical issue. Because of how AI systems are developed, gender bias in AI can be problematic. Algorithm developers may be unaware of their prejudices, and implicit biases and unknowingly pass their socially rooted gender prejudices onto robots. This is evident because the present trends in machine learning reinforce historical stereotypes of women, such as humility, mildness, and the need for protection. For instance, security robots are primarily male, but service and sex robots are primarily female. Another example is AI-driven risk analysis in the justice system. The algorithms may overlook the fact that women are less likely to re-offend than men, placing women at a disadvantage. Female gendering increases bots’ perceived humanity and the acceptability of AI. Consumers believe that female AI is more humane and more reliable and therefore more ready to meet users’ particular demands. Because the feminization of robots boosts their marketability, AI is attempting to humanize them by embedding feminist characteristics and striving for acceptability in a male-dominated robotic society. There’s a risk that machine learning technologies will wind up having biases encoded if women don’t make a significant contribution. Diverse teams made up of both men and women are not just better at recognizing skewed data, but they’re also more likely to spot issues that could have dire societal consequences. While women’s characteristics are highly valued in AI robots, protein-based Footnote 1 women’s jobs are in jeopardy. Presently, women hold only 22% of worldwide AI positions while men hold 78% (World Economic Forum Report, 2018 ). According to another study by wired.com, only 12% of machine learning researchers are women, which is a concerning ratio for a subject that is meant to transform society (Simonite, 2018 ). Because women make up such a small percentage of the technological workforce, technology may become the tangible incarnation of male power in the coming years. The situation in the developing world is worse, and hence a cautious approach is required to ensure that a male-dominated society in some of the developing world’s countries does not abuse AI’s power and use it to exacerbate the predicament of women who are already in a precarious situation.