- Essay Guides

- Other Essays

- How to Write an Ethics Paper: Guide & Ethical Essay Examples

- Speech Topics

- Basics of Essay Writing

- Essay Topics

- Main Academic Essays

- Research Paper Topics

- Basics of Research Paper Writing

- Miscellaneous

- Chicago/ Turabian

- Data & Statistics

- Methodology

- Admission Writing Tips

- Admission Advice

- Other Guides

- Student Life

- Studying Tips

- Understanding Plagiarism

- Academic Writing Tips

- Basics of Dissertation & Thesis Writing

- Research Paper Guides

- Formatting Guides

- Basics of Research Process

- Admission Guides

- Dissertation & Thesis Guides

How to Write an Ethics Paper: Guide & Ethical Essay Examples

Table of contents

Use our free Readability checker

An ethics essay is a type of academic writing that explores ethical issues and dilemmas. Students should evaluates them in terms of moral principles and values. The purpose of an ethics essay is to examine the moral implications of a particular issue, and provide a reasoned argument in support of an ethical perspective.

Writing an essay about ethics is a tough task for most students. The process involves creating an outline to guide your arguments about a topic and planning your ideas to convince the reader of your feelings about a difficult issue. If you still need assistance putting together your thoughts in composing a good paper, you have come to the right place. We have provided a series of steps and tips to show how you can achieve success in writing. This guide will tell you how to write an ethics paper using ethical essay examples to understand every step it takes to be proficient. In case you don’t have time for writing, get in touch with our professional essay writers for hire . Our experts work hard to supply students with excellent essays.

What Is an Ethics Essay?

An ethics essay uses moral theories to build arguments on an issue. You describe a controversial problem and examine it to determine how it affects individuals or society. Ethics papers analyze arguments on both sides of a possible dilemma, focusing on right and wrong. The analysis gained can be used to solve real-life cases. Before embarking on writing an ethical essay, keep in mind that most individuals follow moral principles. From a social context perspective, these rules define how a human behaves or acts towards another. Therefore, your theme essay on ethics needs to demonstrate how a person feels about these moral principles. More specifically, your task is to show how significant that issue is and discuss if you value or discredit it.

Purpose of an Essay on Ethics

The primary purpose of an ethics essay is to initiate an argument on a moral issue using reasoning and critical evidence. Instead of providing general information about a problem, you present solid arguments about how you view the moral concern and how it affects you or society. When writing an ethical paper, you demonstrate philosophical competence, using appropriate moral perspectives and principles.

Things to Write an Essay About Ethics On

Before you start to write ethics essays, consider a topic you can easily address. In most cases, an ethical issues essay analyzes right and wrong. This includes discussing ethics and morals and how they contribute to the right behaviors. You can also talk about work ethic, code of conduct, and how employees promote or disregard the need for change. However, you can explore other areas by asking yourself what ethics mean to you. Think about how a recent game you watched with friends started a controversial argument. Or maybe a newspaper that highlighted a story you felt was misunderstood or blown out of proportion. This way, you can come up with an excellent topic that resonates with your personal ethics and beliefs.

Ethics Paper Outline

Sometimes, you will be asked to submit an outline before writing an ethics paper. Creating an outline for an ethics paper is an essential step in creating a good essay. You can use it to arrange your points and supporting evidence before writing. It also helps organize your thoughts, enabling you to fill any gaps in your ideas. The outline for an essay should contain short and numbered sentences to cover the format and outline. Each section is structured to enable you to plan your work and include all sources in writing an ethics paper. An ethics essay outline is as follows:

- Background information

- Thesis statement

- Restate thesis statement

- Summarize key points

- Final thoughts on the topic

Using this outline will improve clarity and focus throughout your writing process.

Ethical Essay Structure

Ethics essays are similar to other essays based on their format, outline, and structure. An ethical essay should have a well-defined introduction, body, and conclusion section as its structure. When planning your ideas, make sure that the introduction and conclusion are around 20 percent of the paper, leaving the rest to the body. We will take a detailed look at what each part entails and give examples that are going to help you understand them better. Refer to our essay structure examples to find a fitting way of organizing your writing.

Ethics Paper Introduction

An ethics essay introduction gives a synopsis of your main argument. One step on how to write an introduction for an ethics paper is telling about the topic and describing its background information. This paragraph should be brief and straight to the point. It informs readers what your position is on that issue. Start with an essay hook to generate interest from your audience. It can be a question you will address or a misunderstanding that leads up to your main argument. You can also add more perspectives to be discussed; this will inform readers on what to expect in the paper.

Ethics Essay Introduction Example

You can find many ethics essay introduction examples on the internet. In this guide, we have written an excellent extract to demonstrate how it should be structured. As you read, examine how it begins with a hook and then provides background information on an issue.

Imagine living in a world where people only lie, and honesty is becoming a scarce commodity. Indeed, modern society is facing this reality as truth and deception can no longer be separated. Technology has facilitated a quick transmission of voluminous information, whereas it's hard separating facts from opinions.

In this example, the first sentence of the introduction makes a claim or uses a question to hook the reader.

Ethics Essay Thesis Statement

An ethics paper must contain a thesis statement in the first paragraph. Learning how to write a thesis statement for an ethics paper is necessary as readers often look at it to gauge whether the essay is worth their time.

When you deviate away from the thesis, your whole paper loses meaning. In ethics essays, your thesis statement is a roadmap in writing, stressing your position on the problem and giving reasons for taking that stance. It should focus on a specific element of the issue being discussed. When writing a thesis statement, ensure that you can easily make arguments for or against its stance.

Ethical Paper Thesis Example

Look at this example of an ethics paper thesis statement and examine how well it has been written to state a position and provide reasons for doing so:

The moral implications of dishonesty are far-reaching as they undermine trust, integrity, and other foundations of society, damaging personal and professional relationships.

The above thesis statement example is clear and concise, indicating that this paper will highlight the effects of dishonesty in society. Moreover, it focuses on aspects of personal and professional relationships.

Ethics Essay Body

The body section is the heart of an ethics paper as it presents the author's main points. In an ethical essay, each body paragraph has several elements that should explain your main idea. These include:

- A topic sentence that is precise and reiterates your stance on the issue.

- Evidence supporting it.

- Examples that illustrate your argument.

- A thorough analysis showing how the evidence and examples relate to that issue.

- A transition sentence that connects one paragraph to another with the help of essay transitions .

When you write an ethics essay, adding relevant examples strengthens your main point and makes it easy for others to understand and comprehend your argument.

Body Paragraph for Ethics Paper Example

A good body paragraph must have a well-defined topic sentence that makes a claim and includes evidence and examples to support it. Look at part of an example of ethics essay body paragraph below and see how its idea has been developed:

Honesty is an essential component of professional integrity. In many fields, trust and credibility are crucial for professionals to build relationships and success. For example, a doctor who is dishonest about a potential side effect of a medication is not only acting unethically but also putting the health and well-being of their patients at risk. Similarly, a dishonest businessman could achieve short-term benefits but will lose their client’s trust.

Ethics Essay Conclusion

A concluding paragraph shares the summary and overview of the author's main arguments. Many students need clarification on what should be included in the essay conclusion and how best to get a reader's attention. When writing an ethics paper conclusion, consider the following:

- Restate the thesis statement to emphasize your position.

- Summarize its main points and evidence.

- Final thoughts on the issue and any other considerations.

You can also reflect on the topic or acknowledge any possible challenges or questions that have not been answered. A closing statement should present a call to action on the problem based on your position.

Sample Ethics Paper Conclusion

The conclusion paragraph restates the thesis statement and summarizes the arguments presented in that paper. The sample conclusion for an ethical essay example below demonstrates how you should write a concluding statement.

In conclusion, the implications of dishonesty and the importance of honesty in our lives cannot be overstated. Honesty builds solid relationships, effective communication, and better decision-making. This essay has explored how dishonesty impacts people and that we should value honesty. We hope this essay will help readers assess their behavior and work towards being more honest in their lives.

In the above extract, the writer gives final thoughts on the topic, urging readers to adopt honest behavior.

How to Write an Ethics Paper?

As you learn how to write an ethics essay, it is not advised to immediately choose a topic and begin writing. When you follow this method, you will get stuck or fail to present concrete ideas. A good writer understands the importance of planning. As a fact, you should organize your work and ensure it captures key elements that shed more light on your arguments. Hence, following the essay structure and creating an outline to guide your writing process is the best approach. In the following segment, we have highlighted step-by-step techniques on how to write a good ethics paper.

1. Pick a Topic

Before writing ethical papers, brainstorm to find ideal topics that can be easily debated. For starters, make a list, then select a title that presents a moral issue that may be explained and addressed from opposing sides. Make sure you choose one that interests you. Here are a few ideas to help you search for topics:

- Review current trends affecting people.

- Think about your personal experiences.

- Study different moral theories and principles.

- Examine classical moral dilemmas.

Once you find a suitable topic and are ready, start to write your ethics essay, conduct preliminary research, and ascertain that there are enough sources to support it.

2. Conduct In-Depth Research

Once you choose a topic for your essay, the next step is gathering sufficient information about it. Conducting in-depth research entails looking through scholarly journals to find credible material. Ensure you note down all sources you found helpful to assist you on how to write your ethics paper. Use the following steps to help you conduct your research:

- Clearly state and define a problem you want to discuss.

- This will guide your research process.

- Develop keywords that match the topic.

- Begin searching from a wide perspective. This will allow you to collect more information, then narrow it down by using the identified words above.

3. Develop an Ethics Essay Outline

An outline will ease up your writing process when developing an ethic essay. As you develop a paper on ethics, jot down factual ideas that will build your paragraphs for each section. Include the following steps in your process:

- Review the topic and information gathered to write a thesis statement.

- Identify the main arguments you want to discuss and include their evidence.

- Group them into sections, each presenting a new idea that supports the thesis.

- Write an outline.

- Review and refine it.

Examples can also be included to support your main arguments. The structure should be sequential, coherent, and with a good flow from beginning to end. When you follow all steps, you can create an engaging and organized outline that will help you write a good essay.

4. Write an Ethics Essay

Once you have selected a topic, conducted research, and outlined your main points, you can begin writing an essay . Ensure you adhere to the ethics paper format you have chosen. Start an ethics paper with an overview of your topic to capture the readers' attention. Build upon your paper by avoiding ambiguous arguments and using the outline to help you write your essay on ethics. Finish the introduction paragraph with a thesis statement that explains your main position. Expand on your thesis statement in all essay paragraphs. Each paragraph should start with a topic sentence and provide evidence plus an example to solidify your argument, strengthen the main point, and let readers see the reasoning behind your stance. Finally, conclude the essay by restating your thesis statement and summarizing all key ideas. Your conclusion should engage the reader, posing questions or urging them to reflect on the issue and how it will impact them.

5. Proofread Your Ethics Essay

Proofreading your essay is the last step as you countercheck any grammatical or structural errors in your essay. When writing your ethic paper, typical mistakes you could encounter include the following:

- Spelling errors: e.g., there, they’re, their.

- Homophone words: such as new vs. knew.

- Inconsistencies: like mixing British and American words, e.g., color vs. color.

- Formatting issues: e.g., double spacing, different font types.

While proofreading your ethical issue essay, read it aloud to detect lexical errors or ambiguous phrases that distort its meaning. Verify your information and ensure it is relevant and up-to-date. You can ask your fellow student to read the essay and give feedback on its structure and quality.

Ethics Essay Examples

Writing an essay is challenging without the right steps. There are so many ethics paper examples on the internet, however, we have provided a list of free ethics essay examples below that are well-structured and have a solid argument to help you write your paper. Click on them and see how each writing step has been integrated. Ethics essay example 1

Ethics essay example 2

Ethics essay example 3

Ethics essay example 4

College ethics essay example 5

Ethics Essay Writing Tips

When writing papers on ethics, here are several tips to help you complete an excellent essay:

- Choose a narrow topic and avoid broad subjects, as it is easy to cover the topic in detail.

- Ensure you have background information. A good understanding of a topic can make it easy to apply all necessary moral theories and principles in writing your paper.

- State your position clearly. It is important to be sure about your stance as it will allow you to draft your arguments accordingly.

- When writing ethics essays, be mindful of your audience. Provide arguments that they can understand.

- Integrate solid examples into your essay. Morality can be hard to understand; therefore, using them will help a reader grasp these concepts.

Bottom Line on Writing an Ethics Paper

Creating this essay is a common exercise in academics that allows students to build critical skills. When you begin writing, state your stance on an issue and provide arguments to support your position. This guide gives information on how to write an ethics essay as well as examples of ethics papers. Remember to follow these points in your writing:

- Create an outline highlighting your main points.

- Write an effective introduction and provide background information on an issue.

- Include a thesis statement.

- Develop concrete arguments and their counterarguments, and use examples.

- Sum up all your key points in your conclusion and restate your thesis statement.

Contact our academic writing platform and have your challenge solved. Here, you can order essays and papers on any topic and enjoy top quality.

Daniel Howard is an Essay Writing guru. He helps students create essays that will strike a chord with the readers.

You may also like

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Philosophy Ethics in Everyday Life

A Life of Integrity: How to Live an Ethical Life

Table of contents, honesty: upholding truth and integrity, empathy: understanding and compassion, responsibility: actions and consequences, sustainability: caring for the planet, continuous self-reflection: growth and improvement, references:.

- Aristotle. (2011). Nicomachean Ethics. Courier Corporation.

- Buber, M. (2002). I and Thou. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development. Harvard University Press.

- Levinas, E. (2004). Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence. Duquesne University Press.

- Singer, P. (1993). Practical Ethics. Cambridge University Press.

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Tabula Rasa

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Philosophers

- Metaphysics

- Thomas Hobbes

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Ethics and Morality

Morality, Ethics, Evil, Greed

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

To put it simply, ethics represents the moral code that guides a person’s choices and behaviors throughout their life. The idea of a moral code extends beyond the individual to include what is determined to be right, and wrong, for a community or society at large.

Ethics is concerned with rights, responsibilities, use of language, what it means to live an ethical life, and how people make moral decisions. We may think of moralizing as an intellectual exercise, but more frequently it's an attempt to make sense of our gut instincts and reactions. It's a subjective concept, and many people have strong and stubborn beliefs about what's right and wrong that can place them in direct contrast to the moral beliefs of others. Yet even though morals may vary from person to person, religion to religion, and culture to culture, many have been found to be universal, stemming from basic human emotions.

- The Science of Being Virtuous

- Understanding Amorality

- The Stages of Moral Development

Those who are considered morally good are said to be virtuous, holding themselves to high ethical standards, while those viewed as morally bad are thought of as wicked, sinful, or even criminal. Morality was a key concern of Aristotle, who first studied questions such as “What is moral responsibility?” and “What does it take for a human being to be virtuous?”

We used to think that people are born with a blank slate, but research has shown that people have an innate sense of morality . Of course, parents and the greater society can certainly nurture and develop morality and ethics in children.

Humans are ethical and moral regardless of religion and God. People are not fundamentally good nor are they fundamentally evil. However, a Pew study found that atheists are much less likely than theists to believe that there are "absolute standards of right and wrong." In effect, atheism does not undermine morality, but the atheist’s conception of morality may depart from that of the traditional theist.

Animals are like humans—and humans are animals, after all. Many studies have been conducted across animal species, and more than 90 percent of their behavior is what can be identified as “prosocial” or positive. Plus, you won’t find mass warfare in animals as you do in humans. Hence, in a way, you can say that animals are more moral than humans.

The examination of moral psychology involves the study of moral philosophy but the field is more concerned with how a person comes to make a right or wrong decision, rather than what sort of decisions he or she should have made. Character, reasoning, responsibility, and altruism , among other areas, also come into play, as does the development of morality.

The seven deadly sins were first enumerated in the sixth century by Pope Gregory I, and represent the sweep of immoral behavior. Also known as the cardinal sins or seven deadly vices, they are vanity, jealousy , anger , laziness, greed, gluttony, and lust. People who demonstrate these immoral behaviors are often said to be flawed in character. Some modern thinkers suggest that virtue often disguises a hidden vice; it just depends on where we tip the scale .

An amoral person has no sense of, or care for, what is right or wrong. There is no regard for either morality or immorality. Conversely, an immoral person knows the difference, yet he does the wrong thing, regardless. The amoral politician, for example, has no conscience and makes choices based on his own personal needs; he is oblivious to whether his actions are right or wrong.

One could argue that the actions of Wells Fargo, for example, were amoral if the bank had no sense of right or wrong. In the 2016 fraud scandal, the bank created fraudulent savings and checking accounts for millions of clients, unbeknownst to them. Of course, if the bank knew what it was doing all along, then the scandal would be labeled immoral.

Everyone tells white lies to a degree, and often the lie is done for the greater good. But the idea that a small percentage of people tell the lion’s share of lies is the Pareto principle, the law of the vital few. It is 20 percent of the population that accounts for 80 percent of a behavior.

We do know what is right from wrong . If you harm and injure another person, that is wrong. However, what is right for one person, may well be wrong for another. A good example of this dichotomy is the religious conservative who thinks that a woman’s right to her body is morally wrong. In this case, one’s ethics are based on one’s values; and the moral divide between values can be vast.

Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg established his stages of moral development in 1958. This framework has led to current research into moral psychology. Kohlberg's work addresses the process of how we think of right and wrong and is based on Jean Piaget's theory of moral judgment for children. His stages include pre-conventional, conventional, post-conventional, and what we learn in one stage is integrated into the subsequent stages.

The pre-conventional stage is driven by obedience and punishment . This is a child's view of what is right or wrong. Examples of this thinking: “I hit my brother and I received a time-out.” “How can I avoid punishment?” “What's in it for me?”

The conventional stage is when we accept societal views on rights and wrongs. In this stage people follow rules with a good boy and nice girl orientation. An example of this thinking: “Do it for me.” This stage also includes law-and-order morality: “Do your duty.”

The post-conventional stage is more abstract: “Your right and wrong is not my right and wrong.” This stage goes beyond social norms and an individual develops his own moral compass, sticking to personal principles of what is ethical or not.

A new study suggests that scientists tend to inflate their own research ethics. One important implication is that this overconfidence may lead to ethical blindspots.

Today we celebrate the 300th birthday of Immanuel Kant. Embrace face-to-face encounters to live up to his motto Dare to Know!

Two award-winning movies about the Holocaust raise questions about whether they contribute to ethical behavior. Some critics say no.

For beauty, we paint our faces, starve ourselves to the bone, feel the burn, suck out our fat, freeze our faces, cut into our skin, and place foreign bodies into our skin.

A popular management philosophy views employees primarily as costs to be minimized.

Do you believe there is a decline in morality in the United States? The reasons you feel that way may surprise you.

Unlike a bystander, who passively watches events unfold without intervening, an upstander takes action to support fairness and respect. Sometimes that means breaking the rules.

Prosecution for war crimes is not only about deterring future crimes, also about preventing anger that continues across the generations.

Review: The film’s carefully mapped-out confusion seems to reflect director Alex Garland’s key point--war, civil or international, ultimately blurs crucial moral distinctions.

Explore vital strategies to drive transparency and ethical leadership in the era of AI.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

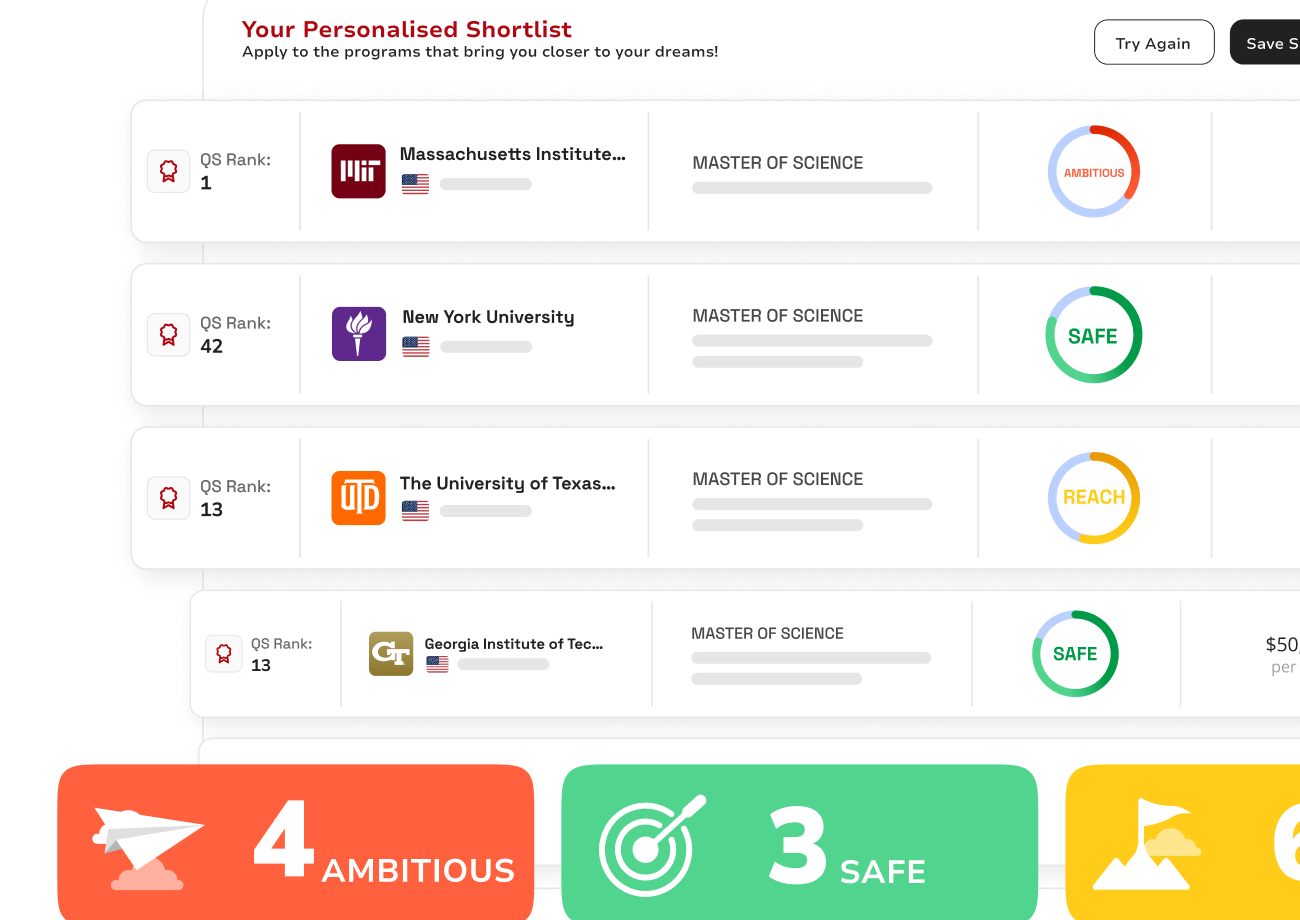

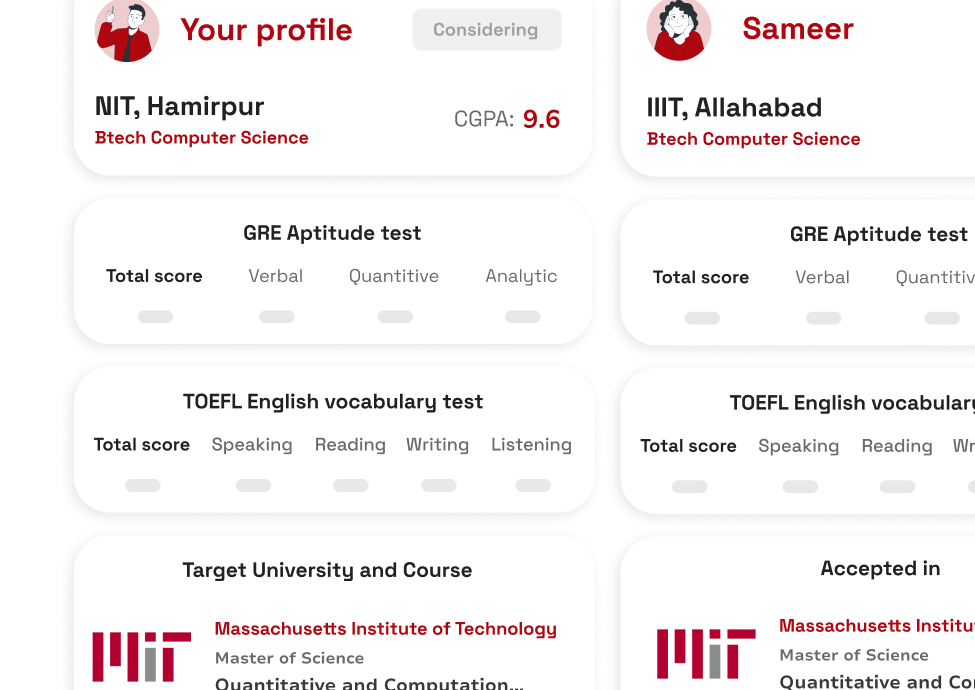

Guidance from our top admission experts — for free!

- Admit Finder

Discover Past Admits, Gauge Your Chances!

- Shortlist Builder

Personalized University Picks, Just a Click Away.

- Course Finder

Navigate Global Courses Tailored for You

- Scholarship Finder

Unlock Funding Opportunities Worldwide.

Get tailored study abroad advice.

Sign in for exclusive content!

Planning to study abroad?

Build your target shortlist and see your odds of getting into top schools with Ambitio's AI shortlist builder!

Heading Out Already?

Our Ivy League mentors and top admission experts can help with personalized tips to get you into your dream school

2 September 2023

7 minutes read

Crafting a Personal Ethics Statement Essay: A Comprehensive Guide

Worried about the cost of Studying Abroad?

Sign up to access 25 game-changing scholarships that could cover your costs.

- Creating a Personal Ethics Statement Essay

A personal ethics statement is a declaration of your beliefs and values. It serves as a mirror reflecting your personal view of ethics, morals, and the decisions you make daily.

Life experiences, religious beliefs, and family influence all contribute to the formation of your personal ethics. This guide will walk you through the necessary steps to craft an effective personal ethics statement essay and discuss the importance of personal and professional ethics in your life.

Stuck on How to Pick Your Ideal College?

Sign up to access your tailored shortlist and simplify finding your ideal college.

- Components of a Personal Ethics Statement

A personal ethics statement typically encompasses the following components:

- Introduction : This section should introduce your personal ethics, ethical principles, and the values you hold dear. Explain how your upbringing, life experiences, and the people in your life have contributed to your current belief system.

- Body : This section is the heart of your personal ethics essay. Elaborate on your values and ethical issues that are most important to you. Discuss how these ethics and morals guide your decisions and actions in every aspect of your life, both personal and professional.

- Conclusion : Summarize your personal ethics statement, emphasizing the key points and explaining how your ethics will play a role in your future decisions, professional growth, and relationships.

Tips for Crafting Your Personal Ethics Statement Essay

While writing your personal ethics statement essay, keep in mind the following tips:

- Be Authentic : Your ethics statement should reflect your true beliefs and values. Avoid listing ethics you feel you “should” have, and instead focus on the ethical guidelines and moral principles that genuinely resonate with you.

- Be Specific : Provide examples of situations where your ethics have guided your decisions or helped you distinguish between right and wrong. These examples can be from your personal or professional life.

- Reflect : Take time to reflect on your experiences and how they have shaped your ethical code. Consider how your ethics may evolve in the future and the impact they may have on your personal and professional relationships.

Importance of Personal and Professional Ethics

Ethics are fundamental to every aspect of your life. They guide your decisions and actions, affect your relationships with others, and influence your self-respect.

Personal ethics are formed through family influence, religious beliefs, and life experiences. Professional ethics, on the other hand, are the ethical standards and code of conduct that you adhere to in a professional setting. Both personal and professional ethics are crucial for maintaining ethical behavior and a clear understanding of right and wrong.

Interrelation between Personal and Professional Ethics

The interrelation between personal and professional ethics is significant in shaping an individual’s character and conduct. Here are some insightful points:

- Values Alignment: Personal ethics often influence professional ethics. When personal values align with organizational values, it fosters a sense of purpose and commitment in one’s work.

- Trustworthiness: Consistency between personal and professional ethics builds trust. Colleagues and clients are more likely to trust individuals who demonstrate integrity in both spheres.

- Decision-Making: Personal ethics serve as a foundation for ethical decision-making at work. Moral principles developed in personal life guide choices in professional dilemmas.

- Reputation: Personal behavior can impact professional reputation. Unethical actions in personal life can tarnish one’s professional image and credibility.

- Stress Reduction: Harmonizing personal and professional ethics reduces cognitive dissonance and stress. When actions align with beliefs, it enhances well-being.

- Leadership Example: Leaders who exemplify strong personal ethics inspire ethical behavior throughout their organizations, fostering a culture of integrity.

- Conflict Resolution: An individual’s personal ethics can aid in resolving ethical conflicts at work. It provides a framework for addressing disagreements and finding solutions.

- Long-Term Success: Individuals with a strong ethical foundation tend to have more sustainable professional careers. Ethical lapses can lead to setbacks and even legal issues.

- Adaptability: Personal ethics can evolve over time, influencing how one adapts to changing professional environments and ethical standards.

- Legal Implications: Personal ethical breaches can have legal repercussions in professional settings, emphasizing the need for alignment.

In essence, personal and professional ethics are intertwined, and recognizing this connection is crucial for ethical development and success in both personal and professional life.

The Role of Family and Religion in Shaping Personal Ethics

Family and religious beliefs play a significant role in shaping one’s personal ethics. From a young age, families impart values and morals, influencing one’s perception of right and wrong. Religious beliefs often provide a set of ethical guidelines and principles that individuals adhere to in their daily lives.

Family Influence

The family is often the first and most influential socializing agent in one’s life. Parents, siblings, and extended family members contribute to shaping one’s personal ethics in various ways:

- Teaching Values : From a young age, parents teach their children fundamental values such as honesty, kindness, and respect. These values form the foundation of a child’s personal ethics.

- Modeling Behavior : Children often mimic the behavior of their parents and other family members. If parents model ethical behavior, children are more likely to adopt similar ethical standards.

- Discussions and Debates : Family discussions about ethical issues, current events, or hypothetical scenarios can help children develop critical thinking skills and form their own opinions about what is right and wrong.

- Setting Expectations : Families often set expectations for behavior, which can influence a child’s sense of right and wrong. For example, a family that values hard work and perseverance may instill a strong work ethic in their children.

Religious Influence

Religion plays a crucial role in shaping personal ethics for many individuals. Religious teachings often provide a framework for understanding the world and making ethical decisions:

- Ethical Guidelines : Many religions have specific guidelines about what is considered right and wrong. For example, the Ten Commandments in Christianity provide a set of ethical guidelines for followers.

- Moral Stories : Religious texts often contain stories that illustrate moral lessons. These stories can help individuals understand and internalize ethical principles.

- Community Influence : Being part of a religious community can also influence one’s personal ethics. The shared beliefs and values of the community can reinforce one’s personal ethics.

- Spiritual Reflection : Religion often encourages self-reflection and mindfulness, which can help individuals gain a deeper understanding of their values and ethical principles.

Interplay between Family and Religion

Family and religion often intersect, and their influences on one’s personal ethics can be intertwined. For example, a family’s religious beliefs often influence the values they teach their children. Conversely, an individual’s personal ethics may influence their religious beliefs and practices.

It is important to reflect on how your family and religious beliefs have influenced your personal ethics and how they continue to guide your decisions and actions.

Understanding the role of family and religion in shaping your personal ethics can help you gain a deeper understanding of yourself and the values you hold dear.

Navigating Ethical Dilemmas with Your Personal Ethics

Ethical dilemmas often arise in both personal and professional settings. Having a clear understanding of your personal ethics can help you navigate these dilemmas and make decisions that align with your values and ethical principles. When faced with an ethical dilemma, consider the following:

- Identify the Dilemma : Clearly define the ethical dilemma you are facing. What are the conflicting values or interests at play?

- Consider the Options : Evaluate all possible options and the potential consequences of each. Consider how each option aligns with your personal ethics.

- Make a Decision : Based on your evaluation, make a decision that aligns with your personal ethics and is the most appropriate course of action.

- Reflect : After making a decision, take time to reflect on the outcome. Did it align with your personal ethics? Would you make the same decision again?

See how Successful Applications Look Like!

Access 350K+ profiles of students who got in. See what you can improve in your own application!

- Being a Role Model through Ethical Behavior

Being a role model means exhibiting ethical behavior in all aspects of your life. Your actions and decisions influence those around you, whether you realize it or not.

By adhering to your personal ethics and making decisions that reflect your values and ethical principles, you can inspire others to do the same. Consider the following tips to be a role model through ethical behavior:

- Lead by Example : Demonstrate ethical behavior in all your actions and decisions. Be consistent in your actions, whether in personal or professional settings.

- Be Accountable : Take responsibility for your actions and decisions. If you make a mistake, acknowledge it, and take steps to rectify it.

- Be Transparent : Be open and honest in your communication with others. Share your thought process and the reasons behind your decisions.

- Encourage Ethical Behavior : Encourage others to act ethically by acknowledging and rewarding ethical behavior.

Start Your University Applications with Ambitio Pro!

Get Ambitio Pro!

Begin your journey to top universities with Ambitio Pro. Our premium platform offers you tools and support needed to craft standout applications.

Unlock Advanced Features for a More Comprehensive Application Experience!

Start your Journey today

- Reflecting and Updating Your Personal Ethics Statement

Your personal ethics may evolve over time due to new experiences, changes in your belief system, or shifts in your perspective on ethical issues.

It is essential to periodically reflect on and update your personal ethics statement. Consider the following steps to reflect on and update your personal ethics statement:

- Reflect on Your Experiences : Take time to reflect on your experiences and how they have influenced your personal ethics. Have you encountered any ethical dilemmas that challenged your beliefs? Have your values or ethical principles evolved?

- Evaluate Your Current Ethics Statement : Review your current personal ethics statement. Does it still accurately reflect your values and ethical principles? Are there any areas that need updating or revising?

- Update Your Ethics Statement : Based on your reflection and evaluation, update your personal ethics statement to accurately reflect your current values and ethical principles.

- Seek Feedback : Share your updated personal ethics statement with a trusted friend, family member, or mentor. Seek feedback on whether your statement accurately reflects your values and ethical principles.

- Implement Your Updated Ethics Statement : Apply your updated personal ethics statement to your daily life and decision-making. Reflect on how your updated ethics influence your actions and decisions.

In conclusion, crafting a personal ethics statement essay is not only an exercise in self-awareness but also a guide that can profoundly influence your decisions and actions, both personally and professionally.

Your personal ethics are a reflection of your character and play a critical role in your interactions, your approach to ethical dilemmas, and your role as a model for others.

Therefore, it is crucial to take time to reflect on your values, consider the influence of family and religion, navigate ethical dilemmas, and continuously update your personal ethics statement.

Remember that your personal ethics are not set in stone; they may evolve and adapt as you grow and learn. Hence, revisiting and revising your personal ethics statement is an essential practice in your journey of self-development and professional growth.

What is a personal ethics statement?

A personal ethics statement is a declaration of your core values and ethical principles that guide your decisions and actions.

Why is a personal ethics statement important?

It helps you gain a clear understanding of your values and ethical guidelines, guiding your decisions and actions in both personal and professional settings.

How do I write a personal ethics statement essay?

Start by reflecting on your values, ethical principles, and life experiences that have shaped your beliefs. Then, organize your thoughts into an introduction, body, and conclusion, elaborating on your values and providing specific examples.

Can my personal ethics evolve over time?

Yes, your personal ethics may evolve due to new experiences, changes in your belief system, or shifts in your perspective on ethical issues. It is essential to periodically reflect on and update your personal ethics statement.

Spread the Word!

Share across your social media if you found it helpful

Table of Contents

- • Creating a Personal Ethics Statement Essay

- • Components of a Personal Ethics Statement

- • Being a Role Model through Ethical Behavior

- • Reflecting and Updating Your Personal Ethics Statement

- • Conclusion

Build your profile to get into top colleges

Phone Number

What level are you targetting

Almost there!

Just enter your OTP, and your planner will be on its way!

Code sent on

Resend OTP (30s)

Your Handbook Is Waiting on WhatsApp!

Please have a look, and always feel free to reach out for any detailed guidance

Click here to download

Meanwhile check out your dashboard to access various tools to help you in your study abroad journey

Recent Blogs

Crafting Your Personal Statement: Mastering English Literature and Creative Writing Applications

Crafting an Impactful Sustainability Personal Statement for Environmental Science and Sustainable Development

A Guide to Electrical and Electronic Engineering Personal Statement Examples

Find your Dream school now⭐️

Welcome! Let's Land Your Dream Admit.

Let us make sure you get into the best!

- 2024 Winter

- 2024 Spring

- 2024 Summer

Enter verification code

Code was sent to

- Our Experts

Connect with us on our social media

Essay on Ethics In Life

Students are often asked to write an essay on Ethics In Life in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Ethics In Life

What are ethics.

Ethics are rules about right and wrong that guide us in life. They help us decide how to act in different situations. Think of them as a moral compass that points to good behavior.

Why Ethics Matter

Ethics are important because they create trust and peace in communities. When we follow ethical rules, we show respect for others and ourselves. This makes it easier for people to get along.

Examples of Ethics

Being honest, fair, and kind are all examples of ethical behavior. Not cheating on a test or not bullying someone are ways we practice ethics every day.

Learning About Ethics

We learn ethics from our families, schools, and friends. Books, stories, and discussions in class can also teach us what is right or wrong.

Challenges to Ethics

Sometimes it’s hard to be ethical, especially if it means losing something we want. Yet, staying true to good ethics is rewarding and builds character.

250 Words Essay on Ethics In Life

Ethics are like rules for deciding what is good or bad. They guide us to act in a way that is fair and kind to others. Imagine if you found a lost wallet. Ethics help you choose to return it instead of keeping it for yourself. They are not laws written by a government, but rather personal principles we live by.

Ethics matter because they make us trust each other. When we are honest and caring, we create a happy and safe place for everyone. For example, when we don’t cheat in games or tests, we show that we can be trusted. This trust builds friendships and makes our families, schools, and communities stronger.

Learning Ethics

We start learning ethics from a young age. Our family, teachers, and friends show us how to share, tell the truth, and treat others nicely. These lessons are like seeds that grow into our own sense of right and wrong. As we get older, these seeds become stronger, helping us make good choices even when it’s tough.

Using Ethics Every Day

Every day, we use ethics to make choices. When we see someone being bullied, ethics tell us to speak up or get help. When we have the chance to lie to get out of trouble, ethics remind us that being honest is important. By using ethics, we can be proud of the choices we make.

In life, ethics are our invisible friends, guiding us to be the best we can be. They help us live together in peace and make sure everyone is treated fairly. By following these simple rules, we create a world that is good for all of us.

500 Words Essay on Ethics In Life

Ethics are like invisible rules that guide us to do what is right and good. They are not written down like school rules, but they live in our minds and hearts, telling us how to act with others and even when we are alone. Imagine ethics as a small voice inside you that helps you choose between sharing your toys or keeping them all to yourself.

Why Are Ethics Important?

Ethics are important because they help us live together peacefully. They make sure we treat each other kindly and fairly. For example, when you find a lost wallet, ethics tell you to return it rather than keep it. This makes the person who lost it happy and helps you feel good about doing the right thing.

Learning Ethics at Home

Our first lessons in ethics come from our families. Parents and older family members teach us to say “please” and “thank you,” to share, and not to hit others. These simple lessons are the building blocks of ethics. They help us understand that thinking about others’ feelings is just as important as our own.

Practicing Ethics at School

School is like a playground for ethics. Every day, we get chances to show honesty by doing our own work, kindness by helping a friend, and responsibility by cleaning up after ourselves. When we work in groups, we learn to listen and respect different ideas, which is also a part of being ethical.

Friendship and Ethics

Ethics are super important in friendships. They teach us to be loyal, which means sticking by our friends even when times are tough. They also remind us not to spread rumors or talk behind someone’s back because it can hurt feelings and break trust.

Playing Fair in Sports

In sports, ethics show up as sportsmanship. This means playing by the rules, not cheating, and being a good winner or a brave loser. It’s about respecting the game, the players, and even the referees, no matter if we win or lose.

Using Ethics Online

The internet is a big world where ethics are super important. We must be kind and respectful, just like we are face-to-face. This means not saying mean things or sharing someone’s secrets. Being ethical online keeps everyone safe and happy.

Looking After Our Planet

Ethics also tell us to care for our Earth. We can do this by recycling, saving water, and not littering. When we look after our planet, we make sure it stays beautiful and healthy for all the animals, plants, and people who live on it.

In conclusion, ethics are like a compass that guides us through life. They help us make choices that are good for us and for everyone around us. By following these invisible rules, we build a world that is kinder, fairer, and more beautiful for everyone. Remember, it’s the little choices we make every day that shape our lives and the world we live in.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Ethics Code For Professional Teachers

- Essay on Ethical Use Of Information

- Essay on Ethical Subjectivism

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Ethical Principles

- First Online: 21 August 2018

Cite this chapter

- Frederick B. Mills 2

259 Accesses

Chapter 4, on The Ethical Principles , articulates the grounds and content of the material, formal and feasibility ethical principles. The material principle requires that we promote the growth of human life in community and in harmony with nature. The formal principle requires that we use symmetrical procedures to advance the material principle. And the feasibility principle limits decisions and actions to what is achievable. This chapter shows in detail how these three principles mutually condition each other and that an act cannot be considered ethically good unless all three principles are in play.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

We can continue to multiply these principles, by considering their application as critical, transitional and constructive principles, in which case there are nine (see Zúñiga 2016a ). For the sake of brevity and simplicity, however, I usually refer to three main principles throughout this monograph.

Dussel expresses concern about the ecological crisis in several works, including Ethics and Community ( 1986 / 1988 , 196–199 [18.3–18.5]); Philosophy of Liberation ( 1977 / 1985 , 114–117 [4.17–4.18]; Ethics of Liberation ( 1998 / 2013 , 39 [43], 103–104 [110–111]); and 14 Tesis de etica ( 2016 , 69 [5.77]).

Dussel advocates a vitalism that is “critical, rational, universal, ethical, and of the left” and warns against the vitalism of the political right which is often racist, such as the case of Hitler ( 2016 , 58 [5.12]).

By regulative idea I mean the Kantian notion that we ought to strive toward an ultimate goal even if it might never be completely realized. The means of advancing toward the approximation of such a goal, however, ought to be feasible.

I use the term ‘carnality’ here as a translation of carnalidad . I mean to convey Dussel’s interpretation of the Hebrew Basár : “The blood, ears, bones, every organ is a faculty of the living unity that is man. There is not, strictly speaking, a ‘corporeality, but rather a ‘carnality’ of the spiritual existence of man in his radical living unity” (Dussel 1969 , 28).

I believe there is a Spinozist element in Dussel’s concept of human life . For Spinoza , the human mind is the idea of the body and the mind is “conscious of its own endeavor” (Spinoza 1677 / 1955 , 92 [Part II., Prop XIII]); 137 [Part III., Prop. IX]).

“The real things surrounding the human being have real physical properties. The apple has such physical components in its real constitution. Only when the living being, and as such [a being] in need, encounters the apple as a possible satisfier of its needs, only in that moment is the apple now food; that is to say, a mediation to replace the energy and material that life consumes in its very [process of] living, in its metabolism” (Dussel 2018 , 70).

Practical reason, argues Dussel, is “the cunning of life” ( 1998 / 2013 , 56 [57], 69 [73]).

For a discussion of the idea of buen vivir as an important contribution to building a new world, see Acosta ( 2013 ).

See Dussel ( 2016 , 16 [1.12]; 2014a , 326–327 [16.77–16.78]).

In The Structure of Behavior ( 1942 / 2008 ), Maurice Merleau-Ponty argues that human behavior (as well as other forms of animal life) is not passively shaped by its environmental stimuli but seeks out those mediations that would satisfy its vital interests . “Physical stimuli,” argues Merleau-Ponty , “act upon the organism only by eliciting a global response which will vary qualitatively when the stimuli vary quantitatively; with respect to the organism they play the role of occasions rather than of cause; the reaction depends on their vital significance rather than on the material properties of the stimuli” (161).

Dussel correctly distinguishes a formal logical version of the argument from Hume’s original argument (Dussel 2001 , 87–93; 1998 / 2013 , 68–69 [73]).

Dussel says: “The need to ‘accept’ the passage from the factual to the normative judgment is grounded in an exercise of practical-material reason, which articulates the relationship between the ‘life’ of the living human being, because of the ethical impossibility of suicide , and the unavoidable responsibility of pursuing the reproduction and development of that life: biological-cultural necessity is ‘imposed’ upon us as an ethical obligation ” ( 1998 / 2013 , 530, note 289).

See Zúñiga ( 2017 ). Dussel referred the author to this article by Jorge Zúñiga in an interview, January 10, 2018, Mexico City.

Hinkelammert argues “planning ‘of everything’ is impossible, but planning of society ‘as a whole’ is without a doubt possible, if only it is in approximate and imperfect terms, as everything in this world is imperfect” ( 1984 , 193, 228).

Zúñiga indicates that the term non-circumventability is taken from Karl-Otto Apel’s transcendental pragmatics ( 2017 , 54).

See Zúñiga ( 2016b ) for a discussion of the application of the principles of impossibility to institutions, including communication communities.

We need to be careful here about allotting and denying ethical status. Parts of the earth’s biosphere that are not reflective can still be considered moral patients and therefore have dignity . The requirement for moral agency, however, is the ability to act deliberately in accordance with ethical principles .

Personal communication of the author with Jorge Zúñiga , January 13, 2018.

See also Dussel ( 2016 , 74–76 [6.3]) on “Rawls’s moral formalism.” We will revisit some of the basic features of social contract theory in more detail in Chapter 5 of this monograph.

By using the terms “first” and “second” ethics here I do not mean to imply that the second completely supersedes the first but that it is later and incorporates much of the first into the second.

In Ethics of Liberation , Dussel makes a clear distinction between the point of departure of discourse ethics versus the ethics of liberation: “The essential difference on this point between discourse ethics and the ethics of liberation is found in the very point of departure. While discourse ethics begins with the community of communication, the ethics of liberation departs from the excluded-affected from such a community. These are the victims of noncommunication. As a result, discourse ethics is practically situated in a position where the fundamental moral norms become ‘inapplicable’ … in ‘normal’ situations of asymmetry ( not particularly exceptional situations ). The ethics of liberation, on the other hand, locates itself precisely in the ‘exceptional situation of the excluded,’ that is to say, in the very moment when discourse ethics discovers its limitations” (Dussel 1998 / 2013 , 294–295 [280]).

Dussel argues that recognition of the Other by ethical-preoriginary reason is a condition of accepting the Other as an equal participant in a communication community . “If I am right on this,” remarks Dussel, “it is clear then, that discursive reason is a moment founded upon ‘ethical-preoriginary reason.’” ( 1998 / 2013 , 301 [286]). One cannot receive the Other as an equal interlocutor without recognizing his or her humanity, and one cannot conceive of the Other’s humanity apart from his or her will to live and grow in community.

See J. Zúñiga ( 2016b , 88–90) for a discussion of the life of the human subject and nature as conditions of possibility for social practices, including the deliberations of communication communities. As we discussed in the section on the material principle , Zúñiga explains this situation by formulating two principles of impossibility related to these conditions.

As Schelkshorn points out, “the idea of consensus not becoming a chimera depends entirely on the possibility of understanding the claims of the Other from his own life world” ( 2000 , 104).

“The practical subject cannot act unless it is a living subject . One has to live in order to be able to conceive ends and to undertake them … To live is also a project that has its own conditions of possibility and fails if it does not achieve them … Only that subset of ends that are integrated to a project of life is feasible” (Hinkelammert, cited by Dussel 1998 / 2013 , 184 [187]).

In “Where Do We Go from Here,” M. L. King, Jr. warns about science without morality: “When scientific power outruns moral power, we end up with guided missiles and misguided men. When we foolishly minimize the internal of our lives and maximize the external, we sign the warrant for our own day of doom” (Washington 1986 , 621).

In 14 tesis de ética , Dussel draws attention to the requirement of feasibility for a goodness (or ethical) claim: “ All human acts or community institutions have a goodness claim if, and only if, in addition to affirming life (first principle) and by agreement of those affected (second principle), they are empirically possible according to the diverse fields and systems that enter into their concrete accomplishment ” ( 2016 , 97 [7.51]).

Acosta, A. (2013). El buen vivir: Sumak kawsay, una oportunidad para imaginar otros mundos . Barcelona: Icaria editorial.

Google Scholar

Apel, K.-O. (1980). Towards a transformation of philosophy (G. Adey & D. Frisby, Trans.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul (original work published 1972).

Dussel, E. (1969). El humanismo semita: estructuras intencionales radicales del pueblo de Israel y otros semitas . Buenos Aires: Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires. Retrieved from http://enriquedussel.com/txt/Textos_Libros/4.Humanismo_semita.pdf .

Dussel, E. (1973). Para una de-strucción de la historia de la ética . Mendoza: Editorial Ser y Tiempo. Retrieved from http://www.ifil.org/dussel/html/07.html .

Dussel, E. (1985). Philosophy of liberation (A. Martinez & C. Morkovsky, Trans.). Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock (original work published 1977).

Dussel, E. (1988). Ethics and community (R. R. Barr, Trans.). New York: Orbis Books (original work published 1986).

Dussel, E. (2001). Hacia una filosofía política crítica . J. A. Senent (Ed.). Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer, S.A. Retrieved from http://www.ifil.org/dussel/html/30.html .

Dussel, E. (2003). An ethics of liberation: Fundamental hypotheses. In E. Mendieta (Ed.), Beyond philosophy: Ethics, history, Marxism, and liberation theology (135–148). New York: Rowman and Littlefield. (original work published 1984 in Concilium 172 (54–63)).

Dussel, E. (2008). Twenty theses on politics (G. Ciccariello-Maher, Trans.). Forward by E. Mendieta. Durham: Duke University Press (original Spanish edition published 2006).

Dussel, E. (2009). Política de la liberación, arquitectónica (Vol. 2). Madrid: Editorial Trotta.

Dussel, E. (2012). La introducción de la “transformación de la filosofía” de K.-O. Apel y la filosofía de la liberación (reflexiones desde una perspectiva Latinoamericana). In K.-O. Apel, E. Dussel, & R. Fornet-Betancourt, Fundamentación de la ética y filosofía de la liberación , (pp. 45–104). México, DF: Siglo Veintiuno Editores (original work published 1992).

Dussel, E. (2013). Ethics of liberation in the age of globalization and exclusion (E. Mendieta, C. P. Bustillo, Y. Angulo, & N. Maldonado-Torres, Trans.). A. A. Vallega (Ed.). Durham: Duke University Press (the original Spanish work was published 1998 by Editorial Trotta).

Dussel, E. (2014a). 16 tesis de economía política: Interpretación filosófica . México, DF: Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

Dussel, E. (2014b). Para una ética de la liberación latinoamericana (Vol. 1). México, DF: Siglo Veintiuno Editores (original work published 1973).

Dussel, E. (2014c). Para una ética de la liberación latinoamericana (Vol. 2). México, DF: Siglo Veintiuno Editores (original work published 1973).

Dussel, E. (2016). 14 Tesis de ética: Hacia la esencia del pensamiento crítico . Madrid: Editorial Trotta, S.A.

Dussel, E. (2018). Siete ensayos de filosofía de la liberación decolonial . Forthcoming, Madrid: Editorial Trotta (Pages cited are from the manuscript).

Hinkelammert, H. (1984). Crítica de la razon utopica . San José, Costa Rica: Editorial DEI.

Marsh, J. L. (2000). The material principle and the formal principle in Dussel’s ethics. In L. M. Alcoff & E. Mendieta (Eds.), Thinking from the underside of history: Enrique Dussel’s philosophy of liberation (pp. 51–67). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1963). The structure of behavior (A. L. Fisher, Trans.). Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press (original work published 1942).

Rawls, J. (1999). A theory of justice (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (original work published 1971).

Schelkshorn, H. (2000). Discourse and liberation: Toward a critical coordination of discourse ethics and Dussel’s ethics of liberation. In L. M. Alcoff & E. Mendieta (Eds.), Thinking from the underside of history: Enrique Dussel’s philosophy of liberation (pp. 97–115). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Spinoza, B. (1955). On the improvement of the understanding. The ethics. Correspondence (R. H. M. Elwes, Trans.). New York: Dover. (original work published 1677).

Washington, J. M. (Ed.). (1986). A testament of hope: The essential writings and speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr . New York: HarperOne.

Zúñiga, J. (2016a). Comentarios a “14 Tesis de ética. Hacia la esencia del pensamiento crítico” de Enrique Dussel. CDMX, México: UNAM.

Zúñiga, J. (2016b). La irrebasabilidad del sujeto viviente, la naturaleza, y la intersubjetividad con relación a las instituciones. In L. Paolicchi & A. Cavilla (Eds.), Discursos sobre la cultura (pp. 75–98). Argentina: Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata.

Zúñiga, J. (2017). The principle of impossibility of the living subject and nature. The CLR James Journal , 23 (1–2), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.5840/clrjames2017121550 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Bowie State University, Bowie, MD, USA

Frederick B. Mills

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Mills, F.B. (2018). The Ethical Principles. In: Enrique Dussel’s Ethics of Liberation. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94550-7_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94550-7_4

Published : 21 August 2018

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-94549-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-94550-7

eBook Packages : Religion and Philosophy Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Ethical Principles in Research Essay

When a researcher fabricates or falsifies data or uses someone else’s words or ideas without permission, that is considered research misconduct. The act must have been deliberate, and there must be enough proof to support the claim. Infractions of authorship/publication rights and abuses of confidentiality are also included in the definition of misconduct. A thorough examination of an allegation is crucial because researchers who are found guilty of misconduct risk losing federal funds, being limited to supervised research or even losing their jobs (Ayodele et al., 2019). I agree that misconduct in research can result in biased decisions of policymakers. This can be detrimental to society and the development of different spheres. Therefore, researchers should be penalized for misconduct in a strict manner.

A set of rules that direct your study designs and procedures are known as ethical considerations in research. When gathering data from people, scientists and researchers must always abide by a set of ethical principles. Understanding real-world occurrences, researching efficient therapies, examining habits, and enhancing lives in other ways are frequently the objectives of human research. There are essentual ethical considerations in both what a researcher chooses to research and how you conduct that research.

All people acknowledge some universal ethical standards, but they each interpret, apply, and balance them differently in light of their own values and life experiences, which is one reasonable explanation for these disparities. For instance, two persons who have different perspectives on what it means to be a human being might concur that murder is wrong but disagree about the morality of abortion. This is why researchers have a formal code of conduct for completing their research.

Ayodele, F. O., Yao, L., & Haron, H. (2019). Promoting ethics and integrity in management academic research: Retraction initiative. Science and Engineering Ethics , 25 (2), 357-382.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 25). Ethical Principles in Research. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethical-principles-in-research/

"Ethical Principles in Research." IvyPanda , 25 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/ethical-principles-in-research/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Ethical Principles in Research'. 25 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Ethical Principles in Research." March 25, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethical-principles-in-research/.

1. IvyPanda . "Ethical Principles in Research." March 25, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethical-principles-in-research/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Ethical Principles in Research." March 25, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethical-principles-in-research/.

- Legal and Ethical Practices Against Fraud and Abuse

- The Political Satire Film "Wag the Dog"

- Assigning Appropriate Authorship

- Kantar Retail Company's Website Evaluation

- Healthcare: Clinical Roles and Social Identities

- The Authorship of Hebrews

- Shortcomings and their Solutions in Managerial Communication

- Peer Review of Authorship Ethics

- The Authorship of the "Book of James"

- Authorship Concept in the Film "Django Unchained"

- Abortion Rights: The Ethical Issues

- Ethics Surrounding Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research

- Ethical Principles: How Social Psychologists Do Research

- Deception Lessons from "The Boy Who Cried Wolf" Tale

- Misconception in the West of Memphis Documentary

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Med Princ Pract

- v.30(1); 2021 Feb

Principles of Clinical Ethics and Their Application to Practice

An overview of ethics and clinical ethics is presented in this review. The 4 main ethical principles, that is beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice, are defined and explained. Informed consent, truth-telling, and confidentiality spring from the principle of autonomy, and each of them is discussed. In patient care situations, not infrequently, there are conflicts between ethical principles (especially between beneficence and autonomy). A four-pronged systematic approach to ethical problem-solving and several illustrative cases of conflicts are presented. Comments following the cases highlight the ethical principles involved and clarify the resolution of these conflicts. A model for patient care, with caring as its central element, that integrates ethical aspects (intertwined with professionalism) with clinical and technical expertise desired of a physician is illustrated.

Highlights of the Study

- Main principles of ethics, that is beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice, are discussed.

- Autonomy is the basis for informed consent, truth-telling, and confidentiality.

- A model to resolve conflicts when ethical principles collide is presented.

- Cases that highlight ethical issues and their resolution are presented.

- A patient care model that integrates ethics, professionalism, and cognitive and technical expertise is shown.

Introduction

A defining responsibility of a practicing physician is to make decisions on patient care in different settings. These decisions involve more than selecting the appropriate treatment or intervention.

Ethics is an inherent and inseparable part of clinical medicine [ 1 ] as the physician has an ethical obligation (i) to benefit the patient, (ii) to avoid or minimize harm, and to (iii) respect the values and preferences of the patient. Are physicians equipped to fulfill this ethical obligation and can their ethical skills be improved? A goal-oriented educational program [ 2 ] (Table (Table1) 1 ) has been shown to improve learner awareness, attitudes, knowledge, moral reasoning, and confidence [ 3 , 4 ].

Goals of ethics education

Ethics, Morality, and Professional Standards

Ethics is a broad term that covers the study of the nature of morals and the specific moral choices to be made. Normative ethics attempts to answer the question, “Which general moral norms for the guidance and evaluation of conduct should we accept, and why?” [ 5 ]. Some moral norms for right conduct are common to human kind as they transcend cultures, regions, religions, and other group identities and constitute common morality (e.g., not to kill, or harm, or cause suffering to others, not to steal, not to punish the innocent, to be truthful, to obey the law, to nurture the young and dependent, to help the suffering, and rescue those in danger). Particular morality refers to norms that bind groups because of their culture, religion, profession and include responsibilities, ideals, professional standards, and so on. A pertinent example of particular morality is the physician's “accepted role” to provide competent and trustworthy service to their patients. To reduce the vagueness of “accepted role,” physician organizations (local, state, and national) have codified their standards. However, complying with these standards, it should be understood, may not always fulfill the moral norms as the codes have “often appeared to protect the profession's interests more than to offer a broad and impartial moral viewpoint or to address issues of importance to patients and society” [ 6 ].

Bioethics and Clinical (Medical) Ethics

A number of deplorable abuses of human subjects in research, medical interventions without informed consent, experimentation in concentration camps in World War II, along with salutary advances in medicine and medical technology and societal changes, led to the rapid evolution of bioethics from one concerned about professional conduct and codes to its present status with an extensive scope that includes research ethics, public health ethics, organizational ethics, and clinical ethics.

Hereafter, the abbreviated term, ethics, will be used as I discuss the principles of clinical ethics and their application to clinical practice.

The Fundamental Principles of Ethics

Beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice constitute the 4 principles of ethics. The first 2 can be traced back to the time of Hippocrates “to help and do no harm,” while the latter 2 evolved later. Thus, in Percival's book on ethics in early 1800s, the importance of keeping the patient's best interest as a goal is stressed, while autonomy and justice were not discussed. However, with the passage of time, both autonomy and justice gained acceptance as important principles of ethics. In modern times, Beauchamp and Childress' book on Principles of Biomedical Ethics is a classic for its exposition of these 4 principles [ 5 ] and their application, while also discussing alternative approaches.

Beneficence

The principle of beneficence is the obligation of physician to act for the benefit of the patient and supports a number of moral rules to protect and defend the right of others, prevent harm, remove conditions that will cause harm, help persons with disabilities, and rescue persons in danger. It is worth emphasizing that, in distinction to nonmaleficence, the language here is one of positive requirements. The principle calls for not just avoiding harm, but also to benefit patients and to promote their welfare. While physicians' beneficence conforms to moral rules, and is altruistic, it is also true that in many instances it can be considered a payback for the debt to society for education (often subsidized by governments), ranks and privileges, and to the patients themselves (learning and research).

Nonmaleficence

Nonmaleficence is the obligation of a physician not to harm the patient. This simply stated principle supports several moral rules − do not kill, do not cause pain or suffering, do not incapacitate, do not cause offense, and do not deprive others of the goods of life. The practical application of nonmaleficence is for the physician to weigh the benefits against burdens of all interventions and treatments, to eschew those that are inappropriately burdensome, and to choose the best course of action for the patient. This is particularly important and pertinent in difficult end-of-life care decisions on withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, medically administered nutrition and hydration, and in pain and other symptom control. A physician's obligation and intention to relieve the suffering (e.g., refractory pain or dyspnea) of a patient by the use of appropriate drugs including opioids override the foreseen but unintended harmful effects or outcome (doctrine of double effect) [ 7 , 8 ].

The philosophical underpinning for autonomy, as interpreted by philosophers Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) and John Stuart Mill (1806–1873), and accepted as an ethical principle, is that all persons have intrinsic and unconditional worth, and therefore, should have the power to make rational decisions and moral choices, and each should be allowed to exercise his or her capacity for self-determination [ 9 ]. This ethical principle was affirmed in a court decision by Justice Cardozo in 1914 with the epigrammatic dictum, “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body” [ 10 ].

Autonomy, as is true for all 4 principles, needs to be weighed against competing moral principles, and in some instances may be overridden; an obvious example would be if the autonomous action of a patient causes harm to another person(s). The principle of autonomy does not extend to persons who lack the capacity (competence) to act autonomously; examples include infants and children and incompetence due to developmental, mental or physical disorder. Health-care institutions and state governments in the US have policies and procedures to assess incompetence. However, a rigid distinction between incapacity to make health-care decisions (assessed by health professionals) and incompetence (determined by court of law) is not of practical use, as a clinician's determination of a patient's lack of decision-making capacity based on physical or mental disorder has the same practical consequences as a legal determination of incompetence [ 11 ].