- Engineering

- Write For Us

- Privacy Policy

Essay on Drug Abuse

Here we have shared the Essay on Drug Abuse in detail so you can use it in your exam or assignment of 150, 250, 400, 500, or 1000 words.

You can use this Essay on Drug Abuse in any assignment or project whether you are in school (class 10th or 12th), college, or preparing for answer writing in competitive exams.

Topics covered in this article.

Essay on Drug Abuse in 150 words

Essay on drug abuse in 250-300 words, essay on drug abuse in 500-1000 words.

Drug abuse is a global issue that poses serious risks to individuals and society. It involves the harmful and excessive use of drugs, leading to physical and mental health problems. Drug abuse can result in addiction, organ damage, cognitive impairment, and social and economic difficulties. Prevention efforts should focus on education, raising awareness about the dangers of drug abuse, and promoting healthy lifestyles. Access to quality healthcare and addiction treatment services is crucial for recovery. Strengthening law enforcement measures against drug trafficking is necessary to address the supply side of the problem. Creating supportive environments and opportunities for positive engagement can help prevent drug abuse. By taking collective action, we can combat drug abuse and build healthier communities.

Drug abuse is a growing global concern that poses significant risks to individuals, families, and communities. It refers to the excessive and harmful use of drugs, both legal and illegal, that have negative effects on physical and mental health.

Drug abuse has severe consequences for individuals and society. Physically, drug abuse can lead to addiction, damage vital organs, and increase the risk of overdose. Mentally, it can cause cognitive impairment, and psychological disorders, and deteriorate overall well-being. Additionally, drug abuse often leads to social and economic problems, such as strained relationships, loss of employment, and criminal activities.

Preventing drug abuse requires a multi-faceted approach. Education and awareness programs play a crucial role in informing individuals about the dangers of drug abuse and promoting healthy lifestyle choices. Access to quality healthcare and addiction treatment services is vital to help individuals recover from substance abuse. Strengthening law enforcement efforts to curb drug trafficking and promoting international cooperation is also essential to address the supply side of the issue.

Community support and a nurturing environment are critical in preventing drug abuse. Creating opportunities for individuals, especially young people, to engage in positive activities and providing social support systems can serve as protective factors against drug abuse.

In conclusion, drug abuse is a significant societal problem with detrimental effects on individuals and communities. It requires a comprehensive approach involving education, prevention, treatment, and enforcement. By addressing the root causes, raising awareness, and providing support to those affected, we can combat drug abuse and create a healthier and safer society for all.

Title: Drug Abuse – A Global Crisis Demanding Urgent Action

Introduction :

Drug abuse is a pressing global issue that poses significant risks to individuals, families, and communities. It refers to the excessive and harmful use of drugs, both legal and illegal, that have detrimental effects on physical and mental health. This essay explores the causes and consequences of drug abuse, the social and economic impact, prevention and treatment strategies, and the importance of raising awareness and fostering supportive communities in addressing this crisis.

Causes and Factors Contributing to Drug Abuse

Several factors contribute to drug abuse. Genetic predisposition, peer pressure, stress, trauma, and environmental influences play a role in initiating substance use. The availability and accessibility of drugs, as well as societal norms and cultural acceptance, also influence drug abuse patterns. Additionally, underlying mental health issues and co-occurring disorders can drive individuals to self-medicate with drugs.

Consequences of Drug Abuse

Drug abuse has devastating consequences on individuals and society. Physically, drug abuse can lead to addiction, tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms. Substance abuse affects vital organs, impairs cognitive function, and increases the risk of accidents and injuries. Mental health disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and psychosis, are often associated with drug abuse. Substance abuse also takes a toll on relationships, leading to strained family dynamics, social isolation, and financial instability. The social and economic costs of drug abuse include increased healthcare expenses, decreased productivity, and the burden on criminal justice systems.

Prevention and Education

Preventing drug abuse requires a comprehensive and multi-faceted approach. Education and awareness programs are essential in schools, communities, and the media to inform individuals about the risks and consequences of drug abuse. Promoting healthy coping mechanisms, stress management skills, and decision-making abilities can empower individuals to resist peer pressure and make informed choices. Early intervention programs that identify at-risk individuals and provide support and resources are crucial in preventing substance abuse.

Treatment and Recovery

Access to quality healthcare and evidence-based addiction treatment is vital in addressing drug abuse. Treatment options include detoxification, counseling, behavioral therapies, and medication-assisted treatments. Rehabilitation centers, support groups, and outpatient programs provide a continuum of care for individuals seeking recovery. Holistic approaches, such as addressing co-occurring mental health disorders and promoting healthy lifestyles, contribute to successful long-term recovery. Support from family, friends, and communities plays a significant role in sustaining recovery and preventing relapse.

Law Enforcement and Drug Policies

Effective law enforcement efforts are necessary to disrupt drug trafficking and dismantle illicit drug networks. International cooperation and collaboration are crucial in combating the global drug trade. Additionally, drug policies should focus on a balanced approach that combines law enforcement with prevention, treatment, and harm reduction strategies. Shifting the emphasis from punitive measures toward prevention and rehabilitation can lead to more effective outcomes.

Creating Supportive Communities:

Fostering supportive communities is vital in addressing drug abuse. Communities should provide resources, social support networks, and opportunities for positive engagement. This includes promoting healthy recreational activities, providing vocational training, and creating safe spaces for individuals in recovery. Reducing the stigma associated with drug abuse and encouraging empathy and understanding are crucial to building a compassionate and supportive environment.

Conclusion :

Drug abuse remains a complex and multifaceted issue with far-reaching consequences. By addressing the causes, raising awareness, implementing preventive measures, providing quality treatment and support services, and fostering supportive communities, we can combat drug abuse and alleviate its impact. It requires collaboration and a collective effort from individuals, communities, governments, and organizations to build a society that is resilient against the scourge of drug abuse. Through education, prevention, treatment, and compassion, we can pave the way toward a healthier and drug-free future.

- Open access

- Published: 07 November 2021

How to prevent alcohol and illicit drug use among students in affluent areas: a qualitative study on motivation and attitudes towards prevention

- Pia Kvillemo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9706-4902 1 ,

- Linda Hiltunen 2 ,

- Youstina Demetry 3 ,

- Anna-Karin Carlander 4 ,

- Tim Hansson 5 ,

- Johanna Gripenberg 1 ,

- Tobias H. Elgán 1 ,

- Kim Einhorn 4 &

- Charlotte Skoglund 1 , 4

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy volume 16 , Article number: 83 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

2 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

The use of alcohol and illicit drugs during adolescence can lead to serious short- and long-term health related consequences. Despite a global trend of decreased substance use, in particular alcohol, among adolescents, evidence suggests excessive use of substances by young people in socioeconomically affluent areas. To prevent substance use-related harm, we need in-depth knowledge about the reasons for substance use in this group and how they perceive various prevention interventions. The aim of the current study was to explore motives for using or abstaining from using substances among students in affluent areas as well as their attitudes to, and suggestions for, substance use prevention.

Twenty high school students (age 15–19 years) in a Swedish affluent municipality were recruited through purposive sampling to take part in semi-structured interviews. Qualitative content analysis of transcribed interviews was performed.

The most prominent motive for substance use appears to be a desire to feel a part of the social milieu and to have high social status within the peer group. Motives for abstaining included academic ambitions, activities requiring sobriety and parental influence. Students reported universal information-based prevention to be irrelevant and hesitation to use selective prevention interventions due to fear of being reported to authorities. Suggested universal prevention concerned reliable information from credible sources, stricter substance control measures for those providing substances, parental involvement, and social leisure activities without substance use. Suggested selective prevention included guaranteed confidentiality and non-judging encounters when seeking help.

Conclusions

Future research on substance use prevention targeting students in affluent areas should take into account the social milieu and with advantage pay attention to students’ suggestions on credible prevention information, stricter control measures for substance providers, parental involvement, substance-free leisure, and confidential ways to seek help with a non-judging approach from adults.

Alcohol consumption and illicit drug use are major public health concerns causing great individual suffering as well as substantial societal costs [ 1 , 2 ]. Early onset of substance use is especially problematic since the developing brain is vulnerable to the effects of alcohol and drugs, increasing the risk of long-term negative effects, such as harmful use, addiction, and mental health problems [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Short-term consequences of substance use include intoxication [ 5 , 7 ], accidents [ 8 [, academic failure [ 9 ], and interaction with legal authorities [ 10 ], which calls for effective substance use prevention in adolescents and young adults. Such prevention interventions may be universal, targeting the general population, e.g., legal measures and school based programs, or selective, targeting certain vulnerable at-risk groups, i.e., subsections of the population [ 11 ]. Selective prevention can be carried out within a universal prevention setting, such as health care or school, but also be delivered directly to the group which it aims to target, face-to-face or digitally [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

The motives to use substances are governed by a number of personal, social and environmental factors [ 16 ], ranging from personal knowledge, abilities, beliefs and attitudes, to the influence of family, friends and society [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Cooper and colleagues [ 21 ] have previously identified a number of motives for drinking, i.e., 1) enhancement (drinking to maintain or amplify positive affect), 2) coping (drinking to avoid or dull negative affect), 3) social (drinking to improve parties or gatherings), and 4) conformity (drinking due to social pressure or a need to fit in). Similar motives for illicit drug use have been found by e.g. Kettner and colleagues, who highlighted the attainment of euphoria and enhancement of activities as prominent motives for use of psychoactive substances among people using psychedelics in parallel with other substances [ 22 ], along with Boys and colleagues [ 23 , 24 , 25 ], who reported on changing mood (e.g., to stop worrying about a problem) and social purposes (e.g., to enjoy the company of friends) as motives for using illicit drugs among young people. Additionally, the authors found that the facilitation of activities (e.g., to concentrate, to work/study), physical effects (e.g., to lose weight), and the managing of the effects of other substances (e.g., to ease or improve) motivated young people to use illicit drugs.

Prior research has repeatedly shown that low socioeconomic status is a risk factor for substance use and related problems [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]. However, recent research from Canada [ 29 ], the United States [ 30 , 31 , 32 ], Serbia [ 33 ], Switzerland [ 34 ], and Sweden [ 35 ] suggest that high socioeconomic status too is associated with excessive substance use among young people, although for other reasons [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Previous research has highlighted two main explanations for excessive substance use among young people in families with high socioeconomic status; i) exceptionally high requirements to perform in both school and leisure activities and ii) absence of adult contact, emotionally and physically, due to parents in resourceful and affluent areas spending a lot of time on their work and careers [ 36 , 37 ]. In addition to these explanations, high physical and social availability due to substantial economic resources and a social milieu were substance use is a natural element, may enable extensive substance use among economically privileged young people [ 30 , 38 , 39 ].

In parallel with identification of various groups at risk for extensive substance use, a growing number of young people globally abstain from using substances [ 1 , 40 , 41 ]. By analyzing data derived from a nationally representative sample of American high school students, Levy and colleagues [ 40 ] found an increasing percentage of 12th-graders reporting no current (past 30 days) substance use between 1976 and 2014, showing that a growing proportion of high school students are motivated to abstain from substance use. However, while this global decrease in substance use among adolescents is mirrored in Swedish youths, in particular alcohol use, a more detailed investigation shows large discrepancies across different socioeconomic and geographic areas. Affluent areas in Sweden stand out as breaking the trend, showing increasing alcohol and illicit drug use among adolescents [ 42 , 43 ].

To date, we lack in-depth knowledge of why youths in affluent areas keep using alcohol and illicit drugs excessively. Furthermore, despite implementation of various strategies and interventions over the last decades [ 14 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ], we have yet no clear guidelines on how to effectively prevent substance use in this specific group, although the importance of parents’ role for preventing substance use in privileged adolescents has been highlighted in a recent study [ 29 ]. Moreover, despite the fact that attitudes are assumed to guide behavior [ 49 , 50 ] and consequently the reception and effects (behavior change) of prevention interventions, the knowledge about affluent adolescents’ attitudes toward current substance use prevention interventions remains limited. To our knowledge, the only study exploring adolescents’ attitudes to substance use prevention was carried out among Spanish adolescents who participated in “open-air gatherings of binge drinkers”. The study concerned adolescents irrespective of their economic background and revealed positive attitudes to restrictions for drunk people [ 19 ]. Thus, extended knowledge on what motivates young people in affluent areas to excessively use substances, or abstaining from using, as well as their attitudes to prevention is warranted.

In the current study, we aim to explore motives for using, or abstaining from using, substances among students in affluent areas. In addition, we aim to explore their attitudes to and suggestions for substance use prevention. The findings may make a valuable contribution to the research on tailored substance use prevention for groups of adolescents that may not be sufficiently supported by current prevention strategies.

A qualitative interview study was performed among high school students in one of Stockholm county’s most affluent municipalities. The research team developed a semi-structured interview guide (supplementary Interview guide) covering issues regarding the individual’s physical and mental health, extent of alcohol and illicit drug use, motives for use or abstinence, relationships with peers and family, alcohol and drug related norms among peers, family and in the society, and attitudes towards strategies to prevent substance use. Examples of interview questions are: How would you describe your health? Which are the main reasons why young people drink, do you think? How do you get hold of alcohol as a teenager?

What do you know about drug use among young people in Municipality X? How would you describe your social relationships with peers in and outside Municipality X?

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (dnr. 2019–02646).

Study setting

Sweden has strict regulations of alcohol and illicit drugs compared to many other countries [ 45 , 46 ]. Alcohol beverages (> 3.5% alcohol content by volume) can only be bought at the Swedish Alcohol Retailing Monopoly “Systembolaget” by people 20 years of age or older, or at licensed premises (e.g., bars, restaurants, clubs), at the minimum age of 18 years. The use of illicit drugs is criminalized. The study was carried out in a municipality with 45% higher annual median income than the corresponding figure for all of Sweden, along with the highest educational level among all Swedish municipalities, i.e., 58% of the population (25 years and over) having graduated from university and hold professional degrees, as compared with the national average of 26%. Furthermore, only 6.1% of the inhabitants receive public assistance, compared to a national average of 13.4% [ 51 ].

Recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to recruit students from the three high schools located in the selected municipality. Contact was established by the research team with the principals of the high schools that agreed to participate in the study. Information and invitation to participate in the study was published on the schools’ online platforms, visible for parents and students. Students communicated their initial interest in participating to the assistant principal. Upon consent from the students, the assistant principal forwarded mobile phone numbers of eligible students to the research team. Also, students from other schools in the selected municipality were asked by friends to participate and upon contact with the research team were invited to participate. Forty students signed up to take part in the study, of which 20 were finally interviewed, representing four schools (three in the selected municipality and one in a neighbor municipality). Before the interview, informed consent was obtained by informing the students about confidentiality arrangements, their right to withdraw their participation and subsequently asking them about their consent to participate. The consent was recorded and transcribed along with the following interview. Twenty students who had initially signed up were excluded after initial consent due to incorrect phone numbers or if the potential participants were not reachable on the agreed time for participation. The reason for terminating the recruitment after 20 interviewees was based on the fact that little or no new information was considered to occur by including additional participants.

Participants

The final sample consisted of 20 students. Background information of the participants is presented in Table 1 . The group included eleven girls and nine boys between 15 and 19 years of age. Seven participants attended natural sciences/technology/mathematic programs and 13 attended social sciences/humanities programs. Twelve participants lived in the socioeconomically affluent municipality where the schools were located and eight in neighboring municipalities. The sample included three abstainers and 17 informants who were using substances, the latter referring to self-reported present use of alcohol and/or illicit drugs (without further specification). Additionally, 18 of the participants reported that at least one of their parents had a university education.

During April–May 2020, semi-structured telephone interviews with the students were conducted by five of the authors (PK, YD, AKC, TH, CS). The interviewers had continuous contact during the interview process, exchanging their experiences from the interviews and also the content of the interviews. After 20 interviews had been conducted, it was assessed that no or little new information could be obtained by additional interviews and the interview process was terminated. The interviews, on average around 60 min long, were recorded on audio files and transcribed verbatim.

Qualitative content analysis, informed by Hsieh & Shannon [ 52 ] and Granheim & Lundman [ 53 ], was used to analyze the interview material. To increase reliability of the analytic process, a team based approach was employed [ 54 ], utilizing the broad expertise represented in the research team and the direct experience of information collected from the five interviewers.

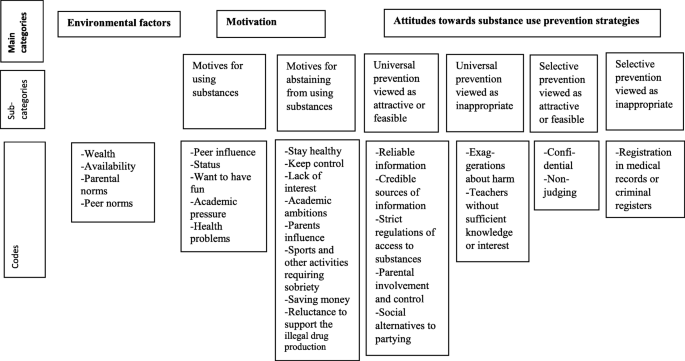

The software NVivo 12 was utilized for structuring the interview data. Initially, one of the researchers (PK) read all the interviews repeatedly, searching for meaningful units which could be grouped into preliminary categories and codes, as exemplified in Table 2 . During the process, a preliminary coding scheme was developed and presented to the whole research team. After discussion, the coding scheme was slightly revised. Following this procedure, a second coder (CS) applied the updated coding scheme along with definitions (codebook) [ 54 ], coding all the interviews independently. Subsequent discussions between PK, YD and CS, resulted in an additionally revised coding scheme. This scheme was utilized by PK and another researcher (LH), who had not been involved in the interviewing or coding, coding all of the interviews independently. The agreement between the coders PK and LH was high and a few disagreements solved through discussion. No change in the codes was necessary and the research team agreed on the coding scheme as outlined in Fig. 1 .

Final coding scheme

The interview material generated three main categories, six subcategories and 27 codes. The results are presented under headings corresponding to the identified subcategories, since they are directly connected to the aim of the study. Content from the main category “External factors” is initially presented to illustrate the context in which the students form their motivation to use or abstain from using substances, as well as their attitudes towards prevention.

External factors

The external factors found in the interview material concerned wealth, availability of alcohol and other substances, parental norms and peer norms. Informants living in the affluent municipality described an expensive lifestyle with boats, ski trips, summer vacations abroad, and frequent restaurant visits, in contrast to informants from other areas who described a more modest lifestyle. These differences were further accentuated by informants’ descriptions of large villas in the affluent municipality, where students can arrange parties while the parents go to their holiday homes. Some informants further pointed to the fact that people in this municipality easily can afford to buy illicit drugs, increasing the availability.

The reason why they do it [use illicit drugs] in [the affluent municipality] is because the parents go away, which make it easier to have parties and be able to smoke grass at home, and also because they can afford it .

Parents’ alcohol norms seemed to vary between families, but most informants described modest drinking at home, with parents consuming alcohol on certain occasions and sometimes when having dinner. However, several informants described that they as minors/children were offered to taste alcohol from the parents’ glasses. Most of the informants meant that their parents trust them not to drink too much when partying.

They [my parents] have said to me that drinking is not good, but that they understand if I drink, sort of.

Both parents’ and peers’ norms appear to influence substance use among the students, The impression is that there is an alcohol liberal norm in the local society among adults as well as among adolescents.

If you want to have a social life in community X, then it is very difficult … you almost cannot have it if you don’t drink at parties.

Motives for using substances

Confirming that both alcohol and illicit drugs are frequently used among students in the current municipality, a number of motives for substance use were expressed by the participants. The most prominent motive appeared to be a desire to feel a part of the social milieu and to attain or maintain high social status, with fear of being excluded from attractive social activities and parties if abstaining from substance use. The participants indicated that you are expected to drink alcohol to be included in the local community social life, claiming that this applied to the adult population as well. Alcohol consumption and even intoxication are perceived to be the norm in the students’ social life and several of the participants noted that abstainers risk being considered too boring to be invited to parties.

The view is that you cannot have fun without alcohol and therefore, you don’t invite sober people.

There seemed to be a high awareness of one’s own as well as peers’ popularity and social status. Participants evaluated peers as high or low status, fun or boring, claiming that trying to be cool and facilitate contact with others motivates people to use substances. High status students are, according to some participants, frequently invited to parties where alcohol and other substances are easily accessible.

I would say that our group of friends has more status. [… ] You know quite a few [people] and you are invited to quite a lot of parties. You can often evaluate the group of friends, i.e. their status, based on which parties they are invited to. […] Some [groups of friends] only drink alcohol and some even take drugs and drink alcohol.

Some differences in traditions and norms between schools was discerned, with certain schools being especially known for high alcohol consumption and drug use procedures when including new students in the school-community. One of the participants described fairly extensive norm violations, with respect to the law, on these occasions, e.g., strong peer pressure to drink alcohol and use illicit drugs, combined with humiliation of new students, careless driving under the influence of substances with other students in the car, and “punishment” by future exclusion from social events of those who don’t participate at these occasions. On the other hand, already popular, or more senior students, appear to be able to abstain from substance use on occasions without being questioned or risk social exclusion. High self-esteem and a firm approach when occasionally saying no to substances is often respected according to the participants. To avoid peer pressure to use alcohol or illicit drugs, the participants suggested acceptable excuses, such as school duties, bringing your moped or car to the party, having a sports activity or work the day after, or having plans with your parents or extended family during the weekend.

Apart from peer influence, several students expressed hedonistic motives, such as enjoying a nice event or simply to have fun.

If you want a little extra fun, then you take drugs.

Apart from social enhancement motives for using substances, some students reported that relaxing from academic pressure or rewarding oneself after an intense period of studying motivates them to use substances. Almost every participant expressed high academic ambitions. One participant who claimed to be very motivated to study expressed drinking due to stress, as illustrated in the extract below:

You study a lot and you are stressed over school. Then it can be very nice to go out and drink and you can forget everything else for a few hours. […] So it can be a “stress reliever” in that way.

Yet another participant explained that academic failure had previously made her use substances to comfort herself. Coping with mental health problems, such as depression, was also stated as a reason for substance use. Moreover, some participants reported that they use ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) medication to be able to study more intensively.

Motives for abstaining from using substances

A number of motives for totally or temporarily abstain from substance use were put forward by the students, such as a wish to be healthy, keep control and avoid embarrassment, influence of parents, academic pressure, sports ambitions or simply lack of interest. Lack of interest in alcohol and drugs was expressed foremost by those attending natural sciences programs and those who totally abstained from substance use.

I attend the engineering program and I don’t think the interest in alcohol and parties is as present as it might be on social sciences programs.

Fear of health consequences was predominantly related to abstaining from illicit drugs, but also alcohol. Motives for abstaining from alcohol included perceived risk of being addicted, due to relatives having alcohol problems (heredity), and taking medicine, for example ADHD medicine, since combining alcohol and medication was perceived as risky. Some students had observed friends getting “weird” or “laze” after using illicit drugs, which made them hesitant to use such substances themselves. With regard to parental norms, most parents were by the participants reported to be “normal drinkers” themselves and quite relaxed about their teens’ alcohol consumption. This applied to both the parents of older teens and minors. However, many of the participants reported that their parents would be upset and disappointed if they found out that their child used illicit substances, which motivated some of them to abstain. Reasons for abstaining from substance use included academic strivings, sports performance ambitions, driving, or other activities requiring sobriety, which the students referred to as socially acceptable reason to abstain from substance use. Prioritizing studies over partying was explicitly expressed as the primary motive to abstain by some of the participants.

We are a group of five or six who come from other municipalities. […] We don’t party and such things and we may be seen as a bit boring. But we are a little more responsible and we are more motivated to study than the others in the class.

A wish to save money and reluctance to support the illegal drug production were also mentioned as reasons to abstain from substance use, however to a lesser extent.

Universal prevention viewed as attractive or feasible

With regard to substance information interventions, some students wanted detailed information about different substances’ physical and psychological effects. The participants emphasized the importance of credible sources or persons providing the information, mentioning researchers, young medical students and even parents as credible sources of information. Individuals who had experience of substance use were also suggested.

You have to tell the facts in a way that makes us want to listen. With the help of various spokespersons who have been involved in it, for example.

Several students stressed the importance of being able to identify with the person sending the message and suggested influencers as plausible sources. Someone who is difficult to relate to was given as an example of a non-credible, as the following excerpt shows:

They shouldn’t take a heroin addicts who talk about having found Jesus, because I do not think it would touch the children or touch the young. You have to somehow find … someone that can relate to the young people.

As for universal prevention, the students also suggested intensified legal measures for companies and people providing young people with alcohol or drugs.

For example, make it difficult for young people to have access to alcohol [...], allocate more time as a police officer to catch the drug dealers.

Both alcohol and illicit drugs were reported as easily accessible. Students can obtain alcohol via social media platforms, such as Instagram and Snapchat, where “liquor cars” market themselves and offer home delivery. In addition, older siblings or peers and even some parents were, according to the informants, providing minor students with alcohol. The main way to access illicit drugs is via parties where older students offer drugs to younger peers. Access to prescription drugs was also reported.

Several of the participants agreed that parental involvement is constructive for substance use prevention. Many of them reported having supportive and caring parents involved in their lives, but at the same time referring to friends’ parents as being more absent, resulting in extensive partying in large homes without parental control. Some students reported that parents don’t realize to what extent youths are using substances and that the parents should pay even more attention to what their children do.

I think [parents should be] keeping track, good track of the kids […] . Keeping track of what they are doing and ask them how they feel and things, I think that helps.

In line with leisure activities as a reason to abstain from substance use, some participants suggested that social activities other than partying could be a way of preventing substance use, as expressed by one participant when asked about plausible ways to prevent substance use.

Find a sport or friend that you train with […] instead of going to a party,

Talking about their leisure activities, the participants expressed joy and that these activities made them relax while being social.

The leisure interests, like working out and hanging out with friends, is relaxing and in contrast to the everyday in some way .

Universal prevention viewed as inappropriate

Several of the participants expressed great skepticism towards traditional universal preventive strategies, such as lectures by teachers, social workers or researchers. Some teachers were perceived as ignorant and unengaged, lecturing about substances only by duty.

The teachers have been a bit like ‘now we’re going to talk about drugs […] and then you have fifteen minutes and they say something like ‘here we are a drug free and smoke and tobacco free school’, and no one obeys.

Some students also doubted that the information provided from school and society is true, suspecting exaggerated report on harm, and that they prefer information from social media platforms such as Youtube or other online sources.

It feels like the information we get in school is a bit exaggerated, a bit made up for us […] A bit like this, ‘now we’ll get the young people to stop’.

Selective prevention viewed as attractive or feasible

In circumstances where students are worried about their own or peers’ substance use, participants stressed the need for a way to connect with local authority, health care or other support anonymously, without being registered in medical records or being reported to the authorities. Moreover, the participants emphasized the importance of a non-judging approach from professionals when they reach out to students at risk of excessive substance use.

If you wonder about something or if you are worried about something, then you should be able to turn to adults without being yelled at and know that you are getting positive feedback like ‘I understand you’ and ‘how can we fix this?’

Selective prevention viewed as inappropriate

As indicated above, help-seeking seemed to be counteracted by fear of being recorded in medical records or in the criminal registries. One participant mentioned an incident where a student, caught smoking marijuana, was prosecuted and that this student’s life had been severely affected with cancellation of planned studies abroad and rejection of driving license application. These consequences had, according to the participant, resulted in the student “giving up” and selling illicit alcohol to other students instead of trying to strive for a good future life. Admitting that such an incident can serve as a warning to other students, the fear of consequences is, according to the participant, still an obstacle to seeking help.

People don’t really know what to do when they see their friends do it [use substances]. You don’t want to tell on them, because they are afraid that if it is written down somewhere, then everything can be ruined.

Also, parents were by the participants reported as being reluctant to seek help for their children, because of fear of the reporting of their child’s behavior or crime to authorities, with subsequent negative consequences.

Parents do not dare either because they don’t want it to be about their children. I know some parents who have found drugs in their children’s rooms, but do not want to ruin [future prospects] for them.

The current study aimed to explore motives for using or abstaining from using substances, including alcohol, among students in affluent areas, as well as their attitudes to and suggestions for substance use prevention.

Summary of results

The motives for using substances among the students are associated with social aspects as.

well as own pleasure and coping with stressful situations. The most prominent motive appears to be a desire to feel a part of the current social milieu and to attain or maintain high social status within the peer group. Several of the students expressed fear of being excluded from attractive social activities if abstaining from substance use, although some meant that they were not interested in substances and didn’t care if they were perceived as boring, and also had found a small group of friends with whom they socialized. Motives for abstaining, apart from lack of interest, included academic ambitions, activities requiring sobriety, parental influence, and a wish to stay healthy. The students expressed negative attitudes towards current information-based prevention as well as problems with using selective prevention interventions due to fear of being registered or reported to the authorities. Students’ suggestions for feasible universal prevention concerned reliable information from credible sources, stricter substance control measures, extended parental involvement, and social leisure activities without substance use. Suggestions regarding selective prevention were guaranteed confidentiality and non-judging encounters when seeking help due to substance use problems.

Comparison with previous research

Children of affluence are generally presumed to be at low risk for negative health outcomes. However, the current study, in accordance with other recent studies [ 29 , 55 ], suggest problems in several domains including alcohol and drug use and stress related problems, even if the cause of these problems cannot be determined based on our interview study. Previous explanations for extensive substance use among affluent young people have been exceptionally high-performance requirements in both school and in leisure activities, and absence of emotional and physical adult contact, resulting from parents in affluent areas spending a lot of time on their jobs and careers [ 30 , 56 , 57 , 58 ]. These explanations can be viewed in the light of Cooper and colleagues’ [ 21 ] as well as Boys and colleagues’ [ 23 , 24 , 25 ] previously identified coping motive for substance use. Coping appears among affluent young people as a central motive for substance use, i.e., coping with performance requirements and perhaps with negative affects due to parents’ absence. In the current study, however, social motives, including conformity, i.e., using substances due to social pressure and a need to fit in [ 21 , 23 , 24 , 25 ] appears to be the most prominent motive, supporting the social learning theory which proposes that behavior can be acquired by observing and imitating others and by rewards connected to the behavior [ 16 , 59 ]. Interestingly, a small group of participants, especially from natural sciences programs, resisted the general pressure to use substances and found a social context of a few friends with whom they socialized without striving for high social status in the larger social context. The wish to be included in the social life and achieve high social status within the peer group was described as a central motive for substance use among a majority of the students, along with fear of being excluded if abstaining. Previous research show that high socioeconomic status is a protective factor for substance use disorder among adults [ 60 ], but among young people it may be the opposite. High status appears to be an important risk factor for the use of substances, at least among those striving for higher status. The students report that they, to achieve high status, must attend parties and at least drink alcohol. After achieving high status, which has resulted in frequent invitations to parties, students then may pose an even higher risk of excessive alcohol and drug use. In line with previous studies, results show that individuals with larger social networks, which has shown to be an indicator for social status among young, also drink more [ 35 , 61 ]. However, status can also act as a protective factor. Individuals with higher status have, according to the interviewees, slightly more room for maneuver to temporarily say no to substances at a party, without being pressured or ashamed. Nevertheless, several of the interviewees reported that they have to choose between using substances or being excluded from desirable social activities, as abstainers are considered “boring”. The results further show that alcohol and other drugs are popular among affluent youth and the information from the participants indicate that the students perceive substance use to be under control. One possible explanation is that high affluence can contribute to a sense of control over one’s life [ 62 ]. Although previous studies show that young people from affluent areas drink more, the risk of developing alcohol problems is still greater among young people who grow up in more disadvantaged areas [ 57 ]. Why this is the case is unclear. There is a widespread belief that affluent youngsters have plenty of social and financial resources in the family and thus receive the right help (e.g., psychotherapy) when they have problems [ 62 ], which could explain why they do not develop alcohol problems. However, research also shows that parents in affluent areas seek less help than others when their children are troubled [ 30 , 63 ], partly due to difficulties in accepting and revealing problems within the family [ 62 ]. In the current study, the informants expressed doubts about the possibility to be guaranteed confidentiality when seeking help, which may mean that there are concerns among both children and parents about the risk of losing status and a good reputation if seeking help for substance use problems. Consequently, there is a risk that any substance use problems will not be noticed in this group [ 62 ].

Previous research indicates that academic pressure may promote substance use [ 56 , 64 ]. However, in the current study academic pressure, due to high ambitions, was reported both as a reason for using substances and abstaining, the former to cope with stress or relax, the latter to maintain a sharp intellect and receive high grades. Moreover, previous research has demonstrated an association between pressure from extracurricular activities or “over scheduling” and negative outcomes among affluent students ( 39 ). In the current study, this did not stand out as a critical vulnerability factor. Instead, students reported extracurricular and leisure activities as relaxing and fun and an accepted reason to abstain from substance use while still attending activities where peers were using substances.

With regard to adult or parental contact, previous research shows that mental health and substance use among adolescents in socioeconomic affluent areas are associated with parents’ lack of reaction to teenage substance use (i.e. liberal, allowing attitudes and minor or no repercussions on discovering use) and parents’ lack of knowledge of their teens’ activities [ 30 ]. In our study, the students reported that their parents do not generally react with punishment due to their child’s alcohol consumption. However, the participants thought that parents probably should react more condemningly due to illicit drug use, if revealed. The Swedish criminalization of illicit substance use [ 46 ] may influence parents to adopt stricter norms with regard to their children’s illicit substance, because of the consequences for revealed substance use that may occur in the Swedish context. Also, parents in the current study were reported as being reluctant to seek help for their children out of fear of negative consequences that may affect their children. This result is in line with previous research, showing that concern about admitting problems in their children is elevated among affluent parents [ 30 ], mentioned above. In the current study, the participants further reported closeness to their parents and that their parents cared about how they spent their time. That said, some parents of wealthy peers were reported as being more absent, resulting in extensive partying in large homes without parental control. Previous research has shown the nature of family relationships and perceptions of closeness to be important protective factors for adolescent mental health [ 56 ], and this seems to apply to the students in the current study.

The students’ attitudes to current substance use prevention, aimed to increase students’ knowledge, are to a large extent negative. Information provided in school were reported as exaggerated and uninteresting. Instead, students suggested interventions focusing on credible sources of reliable information, such as from people with personal adverse experiences of substance use and people whom they can identify with. Whether people with own experience of substance use are credible or helpful in a more objective way can be disputed, but the students seem to put their trust in them rather than other persons. This result is partly in line with previous research on school-based programs in general, suggesting that the role of the teacher (the one who deliver the information) is central and that the use of peer leaders can be successful in engaging the students who receive the message [ 65 , 66 ]. Some informants in the current study meant that the teachers in school were ignorant and unengaged, lecturing about substances only by duty, which of course can be problematic for the sense of credibility among those receiving the information. Previous research has demonstrated that for older adolescents, a social influence approach can increase the effectiveness of alcohol and drug prevention interventions, as can health education, basic skills training and the inclusion of parental support [ 67 ]. Again, this research applies to adolescents in general and not to affluent youth specifically.

Interestingly, the students also suggested stricter regulations on substances with intensified legal measures for those providing substances. Positive attitudes to limiting access of alcohol for drunk people have previously been shown in a Spanish study among adolescents participating in an open-air gatherings of binge drinkers [ 19 ]. The positive attitude to stricter regulations for those providing substances is interesting in the light of the students’ desire for a non-judging approach when having to seek help for own substance use, as described below. Previous research, however, supports strict policy measures to decrease availability as an effective measure for substance use prevention in the general population [ 68 ]. The students further suggested increased parental control and activities and venues which can be attended without using substances, for example sporting/training with friends. Leisure activities without substance use have recently been offered to e.g., adolescents in general in an Icelandic prevention strategy [ 69 ], however more research is needed to see if this kind of prevention is attractive also for large groups of affluent students as an alternative to parties and whether it also appears to be effective in reducing substance use in this group. Clearly, some affluent students without ambitions to receive high social status do find socialization without using substances attractive, as shown in the current study. With regard to selective prevention, the students were critical of the current risk of being reported to parents, registered within medical records or reported to the authorities if turning to professionals for support for substance use problems. They claimed that this circumstance serves as a massive counteracting force to seek help at an early stage for oneself or for peers and that the possibility of reaching out anonymously is essential for taking the first step in seeking help. Moreover, the adolescents in this study call for an open and non-judging approach when turning to health care staff, parents or other adults, which is in line with so called Motivational Interviewing, a non-judging approach aimed to enhance motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence about e.g., substance-related behaviors [ 70 ], which has shown promising results with regard to reduction of alcohol consumption among young people [ 71 ].

Strengths and limitations

The current study has a number of strengths. Firstly, we were able to recruit both male and female students between 15 and 19 years of age, living inside the affluent community as well as in neighboring municipalities, which provided us with a broad base of the students’ social context. Secondly, we included informants using substances as well as abstainers, increasing the possibility to get a broad view of motives to use or abstain from using substances among affluent youth. Thirdly, the research group has extensive experience in qualitative analysis as well as working with adolescents and young adults with mental health problems, including alcohol and drug consumption or abuse. However, our study must also be viewed in the context of some limitations. Students with more severe health or psychosocial problems may have refrained from participating, biasing the results towards adolescents of more stable psychosocial functioning. Moreover, interview studies are always vulnerable for social desirability bias due to a potential desire to give socially acceptable answers [ 72 ]. However, the possibility to terminate participation at any time, along with the circumstance that most of the interviewers are health care professionals, thereby used to handle secrecy in consultation situations, may have decreased the risk of desirability bias in the current study.

Several of the motives guiding substance use behavior among young people in general also seem to apply to affluent youth. A desire to feel a part of the current social milieu and to attain or maintain high social status within the peer group were reported as prominent motives for substance use among affluent students in the current study. Given that the social milieu is crucial for the substance use behavior in this context, future research on substance use prevention targeting this group could with advantage pay attention to suggestions on prevention strategies given by the students. Students’ suggestions include reliable prevention information from credible sources, stricter substance control measures targeting those providing substances, parental involvement, leisure activities without substance use, and confidential ways to seek help, involving a non-judging approach from professionals and other adults.

Availability of data and materials

Collected data will be available from the Centre for Psychiatry Research, a collaboration between Karolinska Institutet and Region Stockholm, but restrictions apply to their availability, as they were used under ethical permission for the current study, and so are not publicly available. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the Centre for Psychiatry Research.

Abbreviations

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

natural sciences/technology/mathematic programs

social sciences/humanities programs

Stockholm prevents alcohol and drug problems

The ESPAD Group. ESPAD report. Results from the European school survey project on alcohol and other drugs. Luxembourg: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction; 2019. p. 2020.

Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. WHO. 2018:2018.

Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Bugbee BA, Vincent KB, O'Grady KE. Marijuana use trajectories during college predict health outcomes nine years post-matriculation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;159:158–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.009 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Burdzovic Andreas J, Lauritzen G, Nordfjærn T. Co-occurrence between mental distress and poly-drug use: a ten year prospective study of patients from substance abuse treatment. Addict Behav. 2015;48:71–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.05.001 .

McGovern R, Kaner E, McArdle P, Ramesh V, Stewart S. Impact of alcohol consumption on young people: a systematic review of published reviews. Newcastle: Newcastle University; 2009.

Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SRB. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2219–27. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1402309 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lees B, Mewton L, Stapinski LA, Squeglia LM, Rae CD, Teesson M. Neurobiological and cognitive profile of young binge drinkers: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2019;29(3):357–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-019-09411-w .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

White V, Azar D, Faulkner A, Coomber K, Durkin S, Livingston M, et al. Adolescents’ alcohol use and strength of policy relating to youth access, trading hours and driving under the influence: findings from Australia. Addiction. 2018;113(6):1030–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14164 .

Hicks RD, Bemis Batzer G, Bemis Batzer W, Imai WK. Psychiatric, developmental, and adolescent medicine issues in adolescent substance use and abuse. Adolesc Med. 1993;4(2):453–68.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16(1):193–213. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579404044475 .

Coie JD, Watt NF, West SG, Hawkins JD, Asarnow JR, Markman HJ, et al. The science of prevention. A conceptual framework and some directions for a national research program. Am Psychol. 1993;48(10):1013–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.10.1013 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Murray E. Web-Based Interventions for Behavior Change and Self-Management: Potential, Pitfalls, and Progress. Med 20. 2012;1(2):e3.

Newton NC, Conrod PJ, Slade T, Carragher N, Champion KE, Barrett EL, et al. The long-term effectiveness of a selective, personality-targeted prevention program in reducing alcohol use and related harms: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57(9):1056–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12558 .

Kvillemo P, Strandberg AK, Gripenberg J, Berman AH, Skoglund C, Elgán TH. Effects of an automated digital brief prevention intervention targeting adolescents and young adults with risky alcohol and other substance use: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(5):e034894. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034894 .

Champion KE, Newton NC, Teesson M. Prevention of alcohol and other drug use and related harm in the digital age: what does the evidence tell us? Current opinion in psychiatry. 2016;29(4):242–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000258 .

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Adv Behav Res Ther. 1978;1(4):139–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4 .

Article Google Scholar

Gerstein DR, Green LW. Preventing Drug Abuse: What do we know? Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). Copyright 1993 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.; 1993.

Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality, and behavior: McGraw-hill education (UK); 2005.

Gervilla E, Quigg Z, Duch M, Juan M, Guimarães C. Adolescents’ Alcohol Use in Botellon and Attitudes towards Alcohol Use and Prevention Policies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11).

DiBello AM, Miller MB, Neighbors C, Reid A, Carey KB. The relative strength of attitudes versus perceived drinking norms as predictors of alcohol use. Addict Behav. 2018;80:39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.022 .

Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(2):117–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117 .

Kettner H, Mason NL, Kuypers KPC. Motives for classical and novel psychoactive substances use in psychedelic Polydrug users. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2019;46(3):304–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450919863899 .

Boys A, Marsden J, Fountain J, Griffiths P, Stillwell G, Strang J. What influences young people's use of drugs? A qualitative study of decision-making. Drugs: education, prevention and policy. 1999;6(3):373–87.

Boys A, Marsden J, Strang J. Understanding reasons for drug use amongst young people: a functional perspective. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(4):457–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/16.4.457 .

Boys A, Marsden J. Perceived functions predict intensity of use and problems in young polysubstance users. Addiction. 2003;98(7):951–63. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00394.x .

Swift W, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Patton GC. Adolescent cannabis users at 24 years: trajectories to regular weekly use and dependence in young adulthood. Addiction. 2008;103(8):1361–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02246.x .

Von Sydow K, Lieb R, Pfister H, Hofler M, H. U W. What predicts incident use of cannabis and progression to abuse and dependence? A 4-year prospective examination of risk factors in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68:49–64.

Probst C, Kilian C, Sanchez S, Lange S, Rehm J. The role of alcohol use and drinking patterns in socioeconomic inequalities in mortality: a systematic review. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(6):e324–e32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30052-9 .

Luthar SS, Small PJ, Ciciolla L. Adolescents from upper middle class communities: substance misuse and addiction across early adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2018;30(1):315–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417000645 .

Levine M. The Price of privilege: how parental pressure and material advantage are creating a generation of disconnected and unhappy kids. New York: Harper; 2008.

Martin CC. High socioeconomic status predicts substance use and alcohol consumption in U.S. undergraduates. Substance Use & Misuse. 2019;54(6):1035–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2018.1559193 .

Patrick ME, Wightman P, Schoeni RF, Schulenberg JE. Socioeconomic status and substance use among young adults: a comparison across constructs and drugs. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(5):772–82. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2012.73.772 .

Janicijevic KM, Kocic SS, Radevic SR, Jovanovic MR, Radovanovic SM. Socioeconomic Factors Associated with Psychoactive Substance Abuse by Adolescents in Serbia. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2017;8:366.

Charitonidi E, Studer J, Gaume J, Gmel G, Daeppen J-B, Bertholet N. Socioeconomic status and substance use among Swiss young men: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):333. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2949-5 .

Hiltunen L. Lagom perfekt. Erfarenheter av ohälsa bland unga tjejer och killar the pursuit of restrained perfection: experiences of ill health among adolescent girls and boys (in Swedish). Växjö: Linnéuniversitetet; 2017.

Låftman SB, Almquist Ylva B, Östberg. Viveca Students’ Accounts of School-performance Stress: A Qualitative Analysis of a High-achieving Setting in Stockholm, Sweden. Journal of Youth Studies. 2013;Vol. 16(nr 7):932–49.

Luthar SS, Becker BE. Privileged but pressured? A study of affluent youth. Child Dev. 2002;73(5):1593–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00492 .

Moore R, Ames G, Cunradi C. Physical and social availability of alcohol for young enlisted naval personnel in and around home port. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy. 2007;2:17.

Luthar SS, Barkin SH. Are affluent youth truly “at risk”? Vulnerability and resilience across three diverse samples. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24(2):429–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000089 .

Levy S, Campbell MD, Shea CL, DuPont R. Trends in abstaining from substance use in adolescents: 1975–2014. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20173498. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3498 .

CAN. Drogutvecklingen i Sverige 2019 (The Drug development in Sweden (In Swedish). 2019.

County Administrative Board of Stockholm. Stockholmsenkäten 2020 (The Stockholm survey 2020) (In Swedish) Stockholm2020 [Available from: https://www.lansstyrelsen.se/download/18.2887c5dd16488fe880d49c70/1536754022929/Stockholmsenk%C3%A4ten%202018%20-%20Droger%20och%20spel%20gymn%20%C3%A5k%202.pdf .

CAN. Jämlika vanor? – Skolans socioekonomiska sammansättning och skillnader i användning av alkohol, narkotika och tobak i årskurs 9 (Equal habits – Schools socioeconomic profile and differences in use of alcohol, narcitics and tobacco in year nine in secondary school) (In Swedish). Stockholm: CAN; 2020.

Demant J, Schierff LM. Five typologies of alcohol and drug prevention programmes. A qualitative review of the content of alcohol and drug prevention programmes targeting adolescents. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2019;26(1):32–9.

Alcohol Act [Alkohollag] (SFS 2010:1622).

Penal Law on Narcotics [Narkotikastrafflag] (SFS 1968:64).

Kristjansson AL, James JE, Allegrante JP, Sigfusdottir ID, Helgason AR. Adolescent substance use, parental monitoring, and leisure-time activities: 12-year outcomes of primary prevention in Iceland. Prev Med. 2010;51(2):168–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.05.001 .

Stockings E, Hall WD, Lynskey M, Morley KI, Reavley N, Strang J, et al. Prevention, early intervention, harm reduction, and treatment of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):280–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00002-X .

Ajzen I, Fishbein M. The prediction of behavior from attitudinal and normative variables. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1970;6(4):466–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(70)90057-0 .

Wallace DS, Paulson RM, Lord CG, Bond CF. Which behaviors do attitudes predict? Meta-analyzing the effects of social pressure and perceived difficulty. Rev Gen Psychol. 2005;9(3):214–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.3.214 .

Statistics Sweden. Utbildning, jobb och dina pengar (Education, job and your money) (In Swedish) 2020 [Available from: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/utbildning-jobb-och-pengar/ .

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687 .

Graneheim U, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 .

MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. CAM Journal. 1998;10(2):31–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X980100020301 .

Luthar SS, Kumar NL, Zillmer N. High-achieving schools connote risks for adolescents: problems documented, processes implicated, and directions for interventions. Am Psychol. 2019;75(7):983–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000556 .

Luthar SS. The culture of affluence: psychological costs of material wealth. Child Dev. 2003;74(6):1581–93. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00625.x .

Pedersen W, Bakken A, von Soest T. Adolescents from affluent city districts drink more alcohol than others. Addiction. 2015;110(10):1595–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13005 .

Komro KA, Maldonado-Molina MM, Tobler AL, Bonds JR, Muller KE. Effects of home access and availability of alcohol on young adolescents' alcohol use. Addiction. 2007;102(10):1597–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01941.x .

Akers RL, Krohn MD, Lanza-Kaduce L, Radosevich M. Social learning and deviant behavior: A specific test of a general theory. Contemporary Masters in Criminology: Springer; 1995. p. 187–214, Social Learning and Deviant Behavior: A Specific Test of a General Theory, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-9829-6_12 .

Deeken F, Banaschewski T, Kluge U, Rapp MA. Risk and protective factors for alcohol use disorders across the lifespan. Current Addiction Reports. 2020;7(3):245–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-020-00313-z .

Neighbors C, Krieger H, Rodriguez LM, Rinker DV, Lembo JM. Social identity and drinking: dissecting social networks and implications for novel interventions. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2019;47(3):259–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2019.1603676 .

Luthar SS, Sexton CC. The high price of affluence. In: Kail RV, editor. Advances in Child Development and Behavior. 32: JAI; 2004. p. 125–162.

Puura K, Almqvist F, Tamminen T, Piha J, Kumpulainen K, Räsänen E, et al. Children with symptoms of depression--what do the adults see? Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 1998;39(4):577–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021963098002418 .

Leonard NR, Gwadz MV, Ritchie A, Linick JL, Cleland CM, Elliott L, et al. A multi-method exploratory study of stress, coping, and substance use among high school youth in private schools. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1028.

McBride N, Farringdon F, Midford R, Meuleners L, Phillips M. Harm minimization in school drug education: final results of the school health and alcohol harm reduction project (SHAHRP). Addiction. 2004;99(3):278–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00620.x .

Midford R, Munro G, McBride N, Snow P, Ladzinski U. Principles that underpin effective school-based drug education. J Drug Educ. 2002;32(4):363–86. https://doi.org/10.2190/T66J-YDBX-J256-J8T9 .

Mewton L, Visontay R, Chapman C, Newton N, Slade T, Kay-Lambkin F, et al. Universal prevention of alcohol and drug use: an overview of reviews in an Australian context. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37(Suppl 1):S435–s69. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12694 .

Toumbourou JW, Stockwell T, Neighbors C, Marlatt GA, Sturge J, Rehm J. Interventions to reduce harm associated with adolescent substance use. Lancet. 2007;369(9570):1391–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60369-9 .

Kristjansson AL, Sigfusdottir ID, Thorlindsson T, Mann MJ, Sigfusson J, Allegrante JP. Population trends in smoking, alcohol use and primary prevention variables among adolescents in Iceland, 1997–2014. Addiction. 2016;111(4):645–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13248 .

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013.

Kohler S, Hofmann A. Can motivational interviewing in emergency care reduce alcohol consumption in young people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire). 2015;50(2):107–17.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Edwards A. The social desirability variable in personality assessment and research. New York: The Dryden Press; 1957.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participating students for making this study possible.

The work was funded by the Alcohol Research Council of the Swedish Alcohol Retailing Monopoly (grant no. 2018–0010). The funding body had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, data interpretation or writing the manuscript. Open Access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

STAD, Centre for Psychiatry Research, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, & Stockholm Health Care Services, Region Stockholm, Norra Stationsgatan 69, SE-113 64, Stockholm, Sweden

Pia Kvillemo, Johanna Gripenberg, Tobias H. Elgán & Charlotte Skoglund

Department of Social Studies, Linnaeus university, Växjö, Sweden

Linda Hiltunen

Centre for Psychiatry Research, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet & Stockholm Health Care Services, Region Stockholm, Liljeholmstorget 7, 117 63, Stockholm, Sweden

Youstina Demetry

Department of Neuroscience, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Anna-Karin Carlander, Kim Einhorn & Charlotte Skoglund

Psychiatry North West, Region Stockholm, Sollentunavägen 84, SE-191 22, Sollentuna, Sweden

Tim Hansson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

PK contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation (data collection), data curation, formal analysis, writing original draft, review & editing, funding acquisition. LH contributed to conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, validation, review & editing. YD contributed to project administration, methodology, investigation (data collection), data curation, formal analysis, validation, review & editing. AC contributed to investigation (data collection), review & editing. TH contributed to investigation (data collection), review & editing. JG contributed to conceptualization, methodology, review & editing, funding acquisition. TE contributed to conceptualization, methodology, review & editing. KE contributed to review & editing. CS contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation (data collection), data curation, formal analysis, review & editing, funding acquisition, supervision. All authors approved the submitted manuscript version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pia Kvillemo .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (dnr. 2019–02646).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kvillemo, P., Hiltunen, L., Demetry, Y. et al. How to prevent alcohol and illicit drug use among students in affluent areas: a qualitative study on motivation and attitudes towards prevention. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 16 , 83 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-021-00420-8

Download citation

Accepted : 19 October 2021

Published : 07 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-021-00420-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Intervention

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy

ISSN: 1747-597X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Tween and teen health

Teen drug abuse: Help your teen avoid drugs

Teen drug abuse can have a major impact on your child's life. Find out how to help your teen make healthy choices and avoid using drugs.

The teen brain is in the process of maturing. In general, it's more focused on rewards and taking risks than the adult brain. At the same time, teenagers push parents for greater freedom as teens begin to explore their personality.

That can be a challenging tightrope for parents.

Teens who experiment with drugs and other substances put their health and safety at risk. The teen brain is particularly vulnerable to being rewired by substances that overload the reward circuits in the brain.

Help prevent teen drug abuse by talking to your teen about the consequences of using drugs and the importance of making healthy choices.

Why teens use or misuse drugs

Many factors can feed into teen drug use and misuse. Your teen's personality, your family's interactions and your teen's comfort with peers are some factors linked to teen drug use.

Common risk factors for teen drug abuse include:

- A family history of substance abuse.

- A mental or behavioral health condition, such as depression, anxiety or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Impulsive or risk-taking behavior.

- A history of traumatic events, such as seeing or being in a car accident or experiencing abuse.

- Low self-esteem or feelings of social rejection.

Teens may be more likely to try substances for the first time when hanging out in a social setting.

Alcohol and nicotine or tobacco may be some of the first, easier-to-get substances for teens. Because alcohol and nicotine or tobacco are legal for adults, these can seem safer to try even though they aren't safe for teens.

Teens generally want to fit in with peers. So if their friends use substances, your teen might feel like they need to as well. Teens also may also use substances to feel more confident with peers.

If those friends are older, teens can find themselves in situations that are riskier than they're used to. For example, they may not have adults present or younger teens may be relying on peers for transportation.

And if they are lonely or dealing with stress, teens may use substances to distract from these feelings.

Also, teens may try substances because they are curious. They may try a substance as a way to rebel or challenge family rules.

Some teens may feel like nothing bad could happen to them, and may not be able to understand the consequences of their actions.

Consequences of teen drug abuse

Negative consequences of teen drug abuse might include:

- Drug dependence. Some teens who misuse drugs are at increased risk of substance use disorder.

- Poor judgment. Teenage drug use is associated with poor judgment in social and personal interactions.

- Sexual activity. Drug use is associated with high-risk sexual activity, unsafe sex and unplanned pregnancy.

- Mental health disorders. Drug use can complicate or increase the risk of mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

- Impaired driving. Driving under the influence of any drug affects driving skills. It puts the driver, passengers and others on the road at risk.

- Changes in school performance. Substance use can result in worse grades, attendance or experience in school.

Health effects of drugs

Substances that teens may use include those that are legal for adults, such as alcohol or tobacco. They may also use medicines prescribed to other people, such as opioids.

Or teens may order substances online that promise to help in sports competition, or promote weight loss.

In some cases products common in homes and that have certain chemicals are inhaled for intoxication. And teens may also use illicit drugs such as cocaine or methamphetamine.

Drug use can result in drug addiction, serious impairment, illness and death. Health risks of commonly used drugs include the following:

- Cocaine. Risk of heart attack, stroke and seizures.

- Ecstasy. Risk of liver failure and heart failure.

- Inhalants. Risk of damage to the heart, lungs, liver and kidneys from long-term use.

- Marijuana. Risk of impairment in memory, learning, problem-solving and concentration; risk of psychosis, such as schizophrenia, hallucination or paranoia, later in life associated with early and frequent use. For teens who use marijuana and have a psychiatric disorder, there is a risk of depression and a higher risk of suicide.