How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Lawmakers ramp up response to unrest.

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 3, 2024

University Commencements Must Go On

Eric J. Gertler May 3, 2024

Where Astronauts Went to College

Cole Claybourn May 3, 2024

College Admitted Student Days

Jarek Rutz May 3, 2024

Universities, the Police and Protests

John J. Sloan III May 2, 2024

Biden Condemns Unrest on Campuses

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 2, 2024

How to Find a Mentor in College

Sarah Wood May 2, 2024

20 Beautiful College Campuses

Cole Claybourn May 1, 2024

Congress Comes Down on Campus Protests

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 1, 2024

University Leaders in Their Own Words

Laura Mannweiler May 1, 2024

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

COVID-19 Pandemic

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 11, 2024 | Original: April 25, 2023

The outbreak of the infectious respiratory disease known as COVID-19 triggered one of the deadliest pandemics in modern history. COVID-19 claimed nearly 7 million lives worldwide. In the United States, deaths from COVID-19 exceeded 1.1 million, nearly twice the American death toll from the 1918 flu pandemic . The COVID-19 pandemic also took a heavy toll economically, politically and psychologically, revealing deep divisions in the way that Americans viewed the role of government in a public health crisis, particularly vaccine mandates. While the United States downgraded its “national emergency” status over the pandemic on May 11, 2023, the full effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will reverberate for decades.

A New Virus Breaks Out in Wuhan, China

In December 2019, the China office of the World Health Organization (WHO) received news of an isolated outbreak of a pneumonia-like virus in the city of Wuhan. The virus caused high fevers and shortness of breath, and the cases seemed connected to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, which was closed by an emergency order on January 1, 2020.

After testing samples of the unknown virus, the WHO identified it as a novel type of coronavirus similar to the deadly SARS virus that swept through Asia from 2002-2004. The WHO named this new strain SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2). The first Chinese victim of SARS-CoV-2 died on January 11, 2020.

Where, exactly, the novel virus originated has been hotly debated. There are two leading theories. One is that the virus jumped from animals to humans, possibly carried by infected animals sold at the Wuhan market in late 2019. A second theory claims the virus escaped from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a research lab that was studying coronaviruses. U.S. intelligence agencies maintain that both origin stories are “plausible.”

The First COVID-19 Cases in America

The WHO hoped that the virus outbreak would be contained to Wuhan, but by mid-January 2020, infections were reported in Thailand, Japan and Korea, all from people who had traveled to China.

On January 18, 2020, a 35-year-old man checked into an urgent care center near Seattle, Washington. He had just returned from Wuhan and was experiencing a fever, nausea and vomiting. On January 21, he was identified as the first American infected with SARS-CoV-2.

In reality, dozens of Americans had contracted SARS-CoV-2 weeks earlier, but doctors didn’t think to test for a new type of virus. One of those unknowingly infected patients died on February 6, 2020, but her death wasn’t confirmed as the first American casualty until April 21.

On February 11, 2020, the WHO released a new name for the disease causing the deadly outbreak: Coronavirus Disease 2019 or COVID-19. By mid-March 2020, all 50 U.S. states had reported at least one positive case of COVID-19, and nearly all of the new infections were caused by “community spread,” not by people who contracted the disease while traveling abroad.

At the same time, COVID-19 had spread to 114 countries worldwide, killing more than 4,000 people and infecting hundreds of thousands more. On March 11, the WHO made it official and declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

The World Shuts Down

Pandemics are expected in a globally interconnected world, so emergency plans were in place. In the United States, health officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) set in motion a national response plan developed for flu pandemics.

State by state and city by city, government officials took emergency measures to encourage “ social distancing ,” one of the many new terms that became part of the COVID-19 vocabulary. Travel was restricted. Schools and churches were closed. With the exception of “essential workers,” all offices and businesses were shuttered. By early April 2020, more than 316 million Americans were under a shelter-in-place or stay-at-home order.

With more than 1,000 deaths and nearly 100,000 cases, it was clear by April 2020 that COVID-19 was highly contagious and virulent. What wasn’t clear, even to public health officials, was how individuals could best protect themselves from COVID-19. In the early weeks of the outbreak, the CDC discouraged people from buying face masks, because officials feared a shortage of masks for doctors and hospital workers.

By April 2020, the CDC revised its recommendations, encouraging people to wear masks in public, to socially distance and to wash hands frequently. President Donald Trump undercut the CDC recommendations by emphasizing that masking was voluntary and vowing not to wear a mask himself. This was just the beginning of the political divisions that hobbled the COVID-19 response in America.

Global Financial Markets Collapse

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, with billions of people worldwide out of work, stuck at home, and fretting over shortages of essential items like toilet paper , global financial markets went into a tailspin.

In the United States, share prices on the New York Stock Exchange plummeted so quickly that the exchange had to shut down trading three separate times. The Dow Jones Industrial Average eventually lost 37 percent of its value, and the S&P 500 was down 34 percent.

Business closures and stay-at-home orders gutted the U.S. economy. The unemployment rate skyrocketed, particularly in the service sector (restaurant and other retail workers). By May 2020, the U.S. unemployment rate reached 14.7 percent, the highest jobless rate since the Great Depression .

All across America, households felt the pinch of lost jobs and lower wages. Food insecurity reached a peak by December 2020 with 30 million American adults—a full 14 percent—reporting that their families didn’t get enough to eat in the past week.

The economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, like its health effects, weren’t experienced equally. Black, Hispanic and Native Americans suffered from unemployment and food insecurity at significantly higher rates than white Americans.

Congress tried to avoid a complete economic collapse by authorizing a series of COVID-19 relief packages in 2020 and 2021, which included direct stimulus checks for all American families.

The Race for a Vaccine

A new vaccine typically takes 10 to 15 years to develop and test, but the world couldn’t wait that long for a COVID-19 vaccine. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under the Trump administration launched “ Operation Warp Speed ,” a public-private partnership which provided billions of dollars in upfront funding to pharmaceutical companies to rapidly develop vaccines and conduct clinical trials.

The first clinical trial for a COVID-19 vaccine was announced on March 16, 2020, only days after the WHO officially classified COVID-19 as a pandemic. The vaccines developed by Moderna and Pfizer were the first ever to employ messenger RNA, a breakthrough technology. After large-scale clinical trials, both vaccines were found to be greater than 95 percent effective against infection with COVID-19.

A nurse from New York officially became the first American to receive a COVID-19 vaccine on December 14, 2020. Ten days later, more than 1 million vaccines had been administered, starting with healthcare workers and elderly residents of nursing homes. As the months rolled on, vaccine availability was expanded to all American adults, and then to teenagers and all school-age children.

By the end of the pandemic in early 2023, more than 670 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines had been administered in the United States at a rate of 203 doses per 100 people. Approximately 80 percent of the U.S. population received at least one COVID-19 shot, but vaccination rates were markedly lower among Black, Hispanic and Native Americans.

COVID-19 Deaths Heaviest Among Elderly and People of Color

In America, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted everyone’s lives, but those who died from the disease were far more likely to be older and people of color.

Of the more than 1.1 million COVID deaths in the United States, 75 percent were individuals who were 65 or older. A full 93 percent of American COVID-19 victims were 50 or older. Throughout the emergence of COVID-19 variants and the vaccine rollouts, older Americans remained the most at-risk for being hospitalized and ultimately dying from the disease.

Black, Hispanic and Native Americans were also at a statistically higher risk of developing life-threatening COVID-19 systems and succumbing to the disease. For example, Black and Hispanic Americans were twice as likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19 than white Americans. The COVID-19 pandemic shined light on the health disparities between racial and ethnic groups driven by systemic racism and lower access to healthcare.

Mental health also worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. The anxiety of contracting the disease, and the stresses of being unemployed or confined at home, led to unprecedented numbers of Americans reporting feelings of depression and suicidal ideation.

A Time of Social & Political Upheaval

In the United States, the three long years of the COVID-19 pandemic paralleled a time of heightened political contention and social upheaval.

When George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police on May 25, 2020, it sparked nationwide protests against police brutality and energized the Black Lives Matter movement. Because so many Americans were out of work or home from school due to COVID-19 shutdowns, unprecedented numbers of people from all walks of life took to the streets to demand reforms.

Instead of banding together to slow the spread of the disease, Americans became sharply divided along political lines in their opinions of masking requirements, vaccines and social distancing.

By March 2024, in signs that the pandemic was waning, the CDC issued new guidelines for people who were recovering from COVID-19. The agency said those infected with the virus no longer needed to remain isolated for five days after symptoms. And on March 10, 2024, the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center stopped collecting data for its highly referenced COVID-19 dashboard.

Still, an estimated 17 percent of U.S. adults reported having experienced symptoms of long COVID, according to the Household Pulse Survey. The medical community is still working to understand the causes behind long COVID, which can afflict a patient for weeks, months or even years.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

“CDC Museum COVID Timeline.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . “Coronavirus: Timeline.” U.S. Department of Defense . “COVID-19 and Related Vaccine Development and Research.” Mayo Clinic . “COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by Race/Ethnicity: Current Data and Changes Over Time.” Kaiser Family Foundation . “Number of COVID-19 Deaths in the U.S. by Age.” Statista . “The Pandemic Deepened Fault Lines in American Society.” Scientific American . “Tracking the COVID-19 Economy’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities . “U.S. Confirmed Country’s First Case of COVID-19 3 Years Ago.” CNN .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

I Thought We’d Learned Nothing From the Pandemic. I Wasn’t Seeing the Full Picture

M y first home had a back door that opened to a concrete patio with a giant crack down the middle. When my sister and I played, I made sure to stay on the same side of the divide as her, just in case. The 1988 film The Land Before Time was one of the first movies I ever saw, and the image of the earth splintering into pieces planted its roots in my brain. I believed that, even in my own backyard, I could easily become the tiny Triceratops separated from her family, on the other side of the chasm, as everything crumbled into chaos.

Some 30 years later, I marvel at the eerie, unexpected ways that cartoonish nightmare came to life – not just for me and my family, but for all of us. The landscape was already covered in fissures well before COVID-19 made its way across the planet, but the pandemic applied pressure, and the cracks broke wide open, separating us from each other physically and ideologically. Under the weight of the crisis, we scattered and landed on such different patches of earth we could barely see each other’s faces, even when we squinted. We disagreed viciously with each other, about how to respond, but also about what was true.

Recently, someone asked me if we’ve learned anything from the pandemic, and my first thought was a flat no. Nothing. There was a time when I thought it would be the very thing to draw us together and catapult us – as a capital “S” Society – into a kinder future. It’s surreal to remember those early days when people rallied together, sewing masks for health care workers during critical shortages and gathering on balconies in cities from Dallas to New York City to clap and sing songs like “Yellow Submarine.” It felt like a giant lightning bolt shot across the sky, and for one breath, we all saw something that had been hidden in the dark – the inherent vulnerability in being human or maybe our inescapable connectedness .

More from TIME

Read More: The Family Time the Pandemic Stole

But it turns out, it was just a flash. The goodwill vanished as quickly as it appeared. A couple of years later, people feel lied to, abandoned, and all on their own. I’ve felt my own curiosity shrinking, my willingness to reach out waning , my ability to keep my hands open dwindling. I look out across the landscape and see selfishness and rage, burnt earth and so many dead bodies. Game over. We lost. And if we’ve already lost, why try?

Still, the question kept nagging me. I wondered, am I seeing the full picture? What happens when we focus not on the collective society but at one face, one story at a time? I’m not asking for a bow to minimize the suffering – a pretty flourish to put on top and make the whole thing “worth it.” Yuck. That’s not what we need. But I wondered about deep, quiet growth. The kind we feel in our bodies, relationships, homes, places of work, neighborhoods.

Like a walkie-talkie message sent to my allies on the ground, I posted a call on my Instagram. What do you see? What do you hear? What feels possible? Is there life out here? Sprouting up among the rubble? I heard human voices calling back – reports of life, personal and specific. I heard one story at a time – stories of grief and distrust, fury and disappointment. Also gratitude. Discovery. Determination.

Among the most prevalent were the stories of self-revelation. Almost as if machines were given the chance to live as humans, people described blossoming into fuller selves. They listened to their bodies’ cues, recognized their desires and comforts, tuned into their gut instincts, and honored the intuition they hadn’t realized belonged to them. Alex, a writer and fellow disabled parent, found the freedom to explore a fuller version of herself in the privacy the pandemic provided. “The way I dress, the way I love, and the way I carry myself have both shrunk and expanded,” she shared. “I don’t love myself very well with an audience.” Without the daily ritual of trying to pass as “normal” in public, Tamar, a queer mom in the Netherlands, realized she’s autistic. “I think the pandemic helped me to recognize the mask,” she wrote. “Not that unmasking is easy now. But at least I know it’s there.” In a time of widespread suffering that none of us could solve on our own, many tended to our internal wounds and misalignments, large and small, and found clarity.

Read More: A Tool for Staying Grounded in This Era of Constant Uncertainty

I wonder if this flourishing of self-awareness is at least partially responsible for the life alterations people pursued. The pandemic broke open our personal notions of work and pushed us to reevaluate things like time and money. Lucy, a disabled writer in the U.K., made the hard decision to leave her job as a journalist covering Westminster to write freelance about her beloved disability community. “This work feels important in a way nothing else has ever felt,” she wrote. “I don’t think I’d have realized this was what I should be doing without the pandemic.” And she wasn’t alone – many people changed jobs , moved, learned new skills and hobbies, became politically engaged.

Perhaps more than any other shifts, people described a significant reassessment of their relationships. They set boundaries, said no, had challenging conversations. They also reconnected, fell in love, and learned to trust. Jeanne, a quilter in Indiana, got to know relatives she wouldn’t have connected with if lockdowns hadn’t prompted weekly family Zooms. “We are all over the map as regards to our belief systems,” she emphasized, “but it is possible to love people you don’t see eye to eye with on every issue.” Anna, an anti-violence advocate in Maine, learned she could trust her new marriage: “Life was not a honeymoon. But we still chose to turn to each other with kindness and curiosity.” So many bonds forged and broken, strengthened and strained.

Instead of relying on default relationships or institutional structures, widespread recalibrations allowed for going off script and fortifying smaller communities. Mara from Idyllwild, Calif., described the tangible plan for care enacted in her town. “We started a mutual-aid group at the beginning of the pandemic,” she wrote, “and it grew so quickly before we knew it we were feeding 400 of the 4000 residents.” She didn’t pretend the conditions were ideal. In fact, she expressed immense frustration with our collective response to the pandemic. Even so, the local group rallied and continues to offer assistance to their community with help from donations and volunteers (many of whom were originally on the receiving end of support). “I’ve learned that people thrive when they feel their connection to others,” she wrote. Clare, a teacher from the U.K., voiced similar conviction as she described a giant scarf she’s woven out of ribbons, each representing a single person. The scarf is “a collection of stories, moments and wisdom we are sharing with each other,” she wrote. It now stretches well over 1,000 feet.

A few hours into reading the comments, I lay back on my bed, phone held against my chest. The room was quiet, but my internal world was lighting up with firefly flickers. What felt different? Surely part of it was receiving personal accounts of deep-rooted growth. And also, there was something to the mere act of asking and listening. Maybe it connected me to humans before battle cries. Maybe it was the chance to be in conversation with others who were also trying to understand – what is happening to us? Underneath it all, an undeniable thread remained; I saw people peering into the mess and narrating their findings onto the shared frequency. Every comment was like a flare into the sky. I’m here! And if the sky is full of flares, we aren’t alone.

I recognized my own pandemic discoveries – some minor, others massive. Like washing off thick eyeliner and mascara every night is more effort than it’s worth; I can transform the mundane into the magical with a bedsheet, a movie projector, and twinkle lights; my paralyzed body can mother an infant in ways I’d never seen modeled for me. I remembered disappointing, bewildering conversations within my own family of origin and our imperfect attempts to remain close while also seeing things so differently. I realized that every time I get the weekly invite to my virtual “Find the Mumsies” call, with a tiny group of moms living hundreds of miles apart, I’m being welcomed into a pocket of unexpected community. Even though we’ve never been in one room all together, I’ve felt an uncommon kind of solace in their now-familiar faces.

Hope is a slippery thing. I desperately want to hold onto it, but everywhere I look there are real, weighty reasons to despair. The pandemic marks a stretch on the timeline that tangles with a teetering democracy, a deteriorating planet , the loss of human rights that once felt unshakable . When the world is falling apart Land Before Time style, it can feel trite, sniffing out the beauty – useless, firing off flares to anyone looking for signs of life. But, while I’m under no delusions that if we just keep trudging forward we’ll find our own oasis of waterfalls and grassy meadows glistening in the sunshine beneath a heavenly chorus, I wonder if trivializing small acts of beauty, connection, and hope actually cuts us off from resources essential to our survival. The group of abandoned dinosaurs were keeping each other alive and making each other laugh well before they made it to their fantasy ending.

Read More: How Ice Cream Became My Own Personal Act of Resistance

After the monarch butterfly went on the endangered-species list, my friend and fellow writer Hannah Soyer sent me wildflower seeds to plant in my yard. A simple act of big hope – that I will actually plant them, that they will grow, that a monarch butterfly will receive nourishment from whatever blossoms are able to push their way through the dirt. There are so many ways that could fail. But maybe the outcome wasn’t exactly the point. Maybe hope is the dogged insistence – the stubborn defiance – to continue cultivating moments of beauty regardless. There is value in the planting apart from the harvest.

I can’t point out a single collective lesson from the pandemic. It’s hard to see any great “we.” Still, I see the faces in my moms’ group, making pancakes for their kids and popping on between strings of meetings while we try to figure out how to raise these small people in this chaotic world. I think of my friends on Instagram tending to the selves they discovered when no one was watching and the scarf of ribbons stretching the length of more than three football fields. I remember my family of three, holding hands on the way up the ramp to the library. These bits of growth and rings of support might not be loud or right on the surface, but that’s not the same thing as nothing. If we only cared about the bottom-line defeats or sweeping successes of the big picture, we’d never plant flowers at all.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

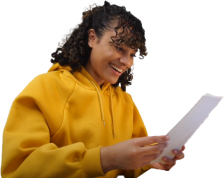

‘When Normal Life Stopped’: College Essays Reflect a Turbulent Year

This year’s admissions essays became a platform for high school seniors to reflect on the pandemic, race and loss.

By Anemona Hartocollis

This year perhaps more than ever before, the college essay has served as a canvas for high school seniors to reflect on a turbulent and, for many, sorrowful year. It has been a psychiatrist’s couch, a road map to a more hopeful future, a chance to pour out intimate feelings about loneliness and injustice.

In response to a request from The New York Times, more than 900 seniors submitted the personal essays they wrote for their college applications. Reading them is like a trip through two of the biggest news events of recent decades: the devastation wrought by the coronavirus, and the rise of a new civil rights movement.

In the wake of the high-profile deaths of Black people like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor at the hands of police officers, students shared how they had wrestled with racism in their own lives. Many dipped their feet into the politics of protest, finding themselves strengthened by their activism, yet sometimes conflicted.

And in the midst of the most far-reaching pandemic in a century, they described the isolation and loss that have pervaded every aspect of their lives since schools suddenly shut down a year ago. They sought to articulate how they have managed while cut off from friends and activities they had cultivated for years.

To some degree, the students were responding to prompts on the applications, with their essays taking on even more weight in a year when many colleges waived standardized test scores and when extracurricular activities were wiped out.

This year the Common App, the nation’s most-used application, added a question inviting students to write about the impact of Covid-19 on their lives and educations. And universities like Notre Dame and Lehigh invited applicants to write about their reactions to the death of George Floyd, and how that inspired them to make the world a better place.

The coronavirus was the most common theme in the essays submitted to The Times, appearing in 393 essays, more than 40 percent. Next was the value of family, coming up in 351 essays, but often in the context of other issues, like the pandemic and race. Racial justice and protest figured in 342 essays.

“We find with underrepresented populations, we have lots of people coming to us with a legitimate interest in seeing social justice established, and they are looking to see their college as their training ground for that,” said David A. Burge, vice president for enrollment management at George Mason University.

Family was not the only eternal verity to appear. Love came up in 286 essays; science in 128; art in 110; music in 109; and honor in 32. Personal tragedy also loomed large, with 30 essays about cancer alone.

Some students resisted the lure of current events, and wrote quirky essays about captaining a fishing boat on Cape Cod or hosting dinner parties. A few wrote poetry. Perhaps surprisingly, politics and the 2020 election were not of great interest.

Most students expect to hear where they were admitted by the end of March or beginning of April. Here are excerpts from a few of the essays, edited for length.

Nandini Likki

Nandini, a senior at the Seven Hills School in Cincinnati, took care of her father after he was hospitalized with Covid-19. It was a “harrowing” but also rewarding time, she writes.

When he came home, my sister and I had to take care of him during the day while my mom went to work. We cooked his food, washed his dishes, and excessively cleaned the house to make sure we didn’t get the disease as well.

It was an especially harrowing time in my life and my mental health suffered due to the amount of stress I was under.

However, I think I grew emotionally and matured because of the experience. My sister and I became more responsible as we took on more adult roles in the family. I grew even closer to my dad and learned how to bond with him in different ways, like using Netflix Party to watch movies together. Although the experience isolated me from most of my friends who couldn’t relate to me, my dad’s illness taught me to treasure my family even more and cherish the time I spend with them.

Nandini has been accepted at Case Western and other schools.

Grace Sundstrom

Through her church in Des Moines, Grace, a senior at Roosevelt High School, began a correspondence with Alden, a man who was living in a nursing home and isolated by the pandemic.

As our letters flew back and forth, I decided to take a chance and share my disgust about the treatment of people of color at the hands of police officers. To my surprise, Alden responded with the same sentiments and shared his experience marching in the civil rights movement in the 1960s.

Here we were, two people generations apart, finding common ground around one of the most polarizing subjects in American history.

When I arrived at my first Black Lives Matter protest this summer, I was greeted by the voices of singing protesters. The singing made me think of a younger Alden, stepping off the train at Union Station in Washington, D.C., to attend the 1963 March on Washington.

Grace has been admitted to Trinity University in San Antonio and is waiting to hear from others.

Ahmed AlMehri

Ahmed, who attends the American School of Kuwait, wrote of growing stronger through the death of his revered grandfather from Covid-19.

Fareed Al-Othman was a poet, journalist and, most importantly, my grandfather. Sept. 8, 2020, he fell victim to Covid-19. To many, he’s just a statistic — one of the “inevitable” deaths. But to me, he was, and continues to be, an inspiration. I understand the frustration people have with the restrictions, curfews, lockdowns and all of the tertiary effects of these things.

But I, personally, would go through it all a hundred times over just to have my grandfather back.

For a long time, things felt as if they weren’t going to get better. Balancing the grief of his death, school and the upcoming college applications was a struggle; and my stress started to accumulate. Covid-19 has taken a lot from me, but it has forced me to grow stronger and persevere. I know my grandfather would be disappointed if I had let myself use his death as an excuse to slack off.

Ahmed has been accepted by the University of California, Irvine, and the University of Miami and is waiting to hear from others.

Mina Rowland

Mina, who lives in a shelter in San Joaquin County, Calif., wrote of becoming homeless in middle school.

Despite every day that I continue to face homelessness, I know that I have outlets for my pain and anguish.

Most things that I’ve had in life have been destroyed, stolen, lost, or taken, but art and poetry shall be with me forever.

The stars in “Starry Night” are my tenacity and my hope. Every time I am lucky enough to see the stars, I am reminded of how far I’ve come and how much farther I can go.

After taking a gap year, Mina and her twin sister, Mirabell, have been accepted at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore and are waiting on others.

Christine Faith Cabusay

Christine, a senior at Stuyvesant High School in New York, decided to break the isolation of the pandemic by writing letters to her friends.

How often would my friends receive something in the mail that was not college mail, a bill, or something they ordered online? My goal was to make opening a letter an experience. I learned calligraphy and Spencerian script so it was as if an 18th-century maiden was writing to them from her parlor on a rainy day.

Washing lines in my yard held an ever-changing rainbow of hand-recycled paper.

With every letter came a painting of something that I knew they liked: fandoms, animals, music, etc. I sprayed my favorite perfume on my signature on every letter because I read somewhere that women sprayed perfume on letters overseas to their partners in World War II; it made writing letters way more romantic (even if it was just to my close friends).

Christine is still waiting to hear from schools.

Alexis Ihezue

Her father’s death from complications of diabetes last year caused Alexis, a student at the Gwinnett School of Mathematics, Science and Technology in Lawrenceville, Ga., to consider the meaning of love.

And in the midst of my grief swallowing me from the inside out, I asked myself when I loved him most, and when I knew he loved me. It’s nothing but brief flashes, like bits and pieces of a dream. I hear him singing “Fix You” by Coldplay on our way home, his hands across the table from me at our favorite wing spot that we went to weekly after school, him driving me home in the middle of a rainstorm, his last message to me congratulating me on making it to senior year.

It’s me finding a plastic spoon in the sink last week and remembering the obnoxious way he used to eat. I see him in bursts and flashes.

A myriad of colors and experiences. And I think to myself, ‘That’s what it is.’ It’s a second. It’s a minute. That’s what love is. It isn’t measured in years, but moments.

Alexis has been accepted by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and is waiting on others.

Ivy Wanjiku

She and her mother came to America “with nothing but each other and $100,” writes Ivy, who was born in Kenya and attends North Cobb High School in Kennesaw, Ga.

I am a triple threat. Foreign, black, female. From the dirt roads and dust that covered the attire of my ancestors who worshiped the soil, I have sprouted new beginnings for generations.

But the question arises; will that generation live to see its day?

Melanin mistaken as a felon, my existence is now a hashtag that trends as often as my rights, a facade at best, a lie in truth. I now know more names of dead blacks than I do the amendments of the Constitution.

Ivy is going to Emory University in Atlanta on full scholarship and credits her essay with helping her get in.

Mary Clare Marshall

The isolation of the pandemic became worse when Mary Clare, a student at Sacred Heart Greenwich in Connecticut, realized that her mother had cancer.

My parents acted like everything was normal, but there were constant reminders of her diagnosis. After her first chemo appointment, I didn’t acknowledge the change. It became real when she came downstairs one day without hair.

No one said anything about the change. It just happened. And it hit me all over again. My mom has cancer.

Even after going to Catholic school for my whole life, I couldn’t help but be angry at God. I felt myself experiencing immense doubt in everything I believe in. Unable to escape my house for any small respite, I felt as though I faced the reality of my mom’s cancer totally alone.

Mary Clare has been admitted to the University of Virginia and is waiting on other schools.

Nora Frances Kohnhorst

Nora, a student at the High School of American Studies at Lehman College in New York, was always “a serial dabbler,” but found commitment in a common pandemic hobby.

In March, when normal life stopped, I took up breadmaking. This served a practical purpose. The pandemic hit my neighborhood in Queens especially hard, and my parents were afraid to go to the store. This forced my family to come up with ways to avoid shopping. I decided I would learn to make sourdough using recipes I found online. Initially, some loaves fell flat, others were too soft inside, and still more spread into strange blobs.

I reminded myself that the bread didn’t need to be perfect, just edible.

It didn’t matter what it looked like; there was no one to see or eat it besides my brother and parents. They depended on my new activity, and that dependency prevented me from repeating the cycle of trying a hobby, losing steam, and moving on to something new.

Nora has been admitted to SUNY Binghamton and the University of Vermont and is waiting to hear from others.

Gracie Yong Ying Silides

Gracie, a student at Greensboro Day School in North Carolina, recalls the “red thread” of a Chinese proverb and wonders where it will take her next.

Destiny has led me into a mysterious place these last nine months: isolation. At a time in my life when I am supposed to be branching out, the Covid pandemic seems to have trimmed those branches back to nubs. I have had to research colleges without setting foot on them. I’ve introduced myself to strangers through essays, videos, and test scores.

I would have fallen apart over this if it weren’t for my faith.

In Hebrews 11:1, Paul says that “faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” My life has shown me that the red thread of destiny guides me where I need to go. Though it might sound crazy, I trust that the red thread is guiding me to the next phase of my journey.

Gracie has been accepted to St. Olaf College, Ithaca College and others.

Levi, a student at Westerville Central High School in Ohio, wrestles with the conflict between her admiration for her father, a police officer, and the negative image of the police.

Since I was a small child I have watched my father put on his dark blue uniform to go to work protecting and serving others. He has always been my hero. As the African-American daughter of a police officer, I believe in what my father stands for, and I am so proud of him because he is not only my protector, but the protector of those I will likely never know. When I was young, I imagined him always being a hero to others, just as he was to me. How could anyone dislike him??? However, as I have gotten older and watched television and social media depict the brutalization of African-Americans, at the hands of police, I have come to a space that is uncomfortable.

I am certain there are others like me — African-Americans who love their police officer family members, yet who despise what the police are doing to African-Americans.

I know that I will not be able to rectify this problem alone, but I want to be a part of the solution where my paradox no longer exists.

Levi has been accepted to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, and is waiting to hear from others.

Henry Thomas Egan

When Henry, a student at Creighton Preparatory School in Omaha, attended a protest after the death of George Floyd, it was the words of a Nina Simone song that stayed with him.

I had never been to a protest before; neither my school, nor my family, nor my city are known for being outspoken. Thousands lined the intersection in all four directions, chanting, “He couldn’t breathe! George Floyd couldn’t breathe!”

In my head, thoughts of hunger, injustice, and silence swirled around.

In my ears, I heard lyrics playing on a speaker nearby, a song by Nina Simone: “To be young, gifted, and Black!” The experience was exceptionally sad and affirming and disorienting at the same time, and when the police arrived and started firing tear gas, I left. A lot has happened in my life over these last four years. I am left not knowing how to sort all of this out and what paths I should follow.

Henry has not yet heard back from colleges.

Anna Valades

Anna, a student at Coronado High School in California, pondered how children learned racism from their parents.

“She said I wasn’t invited to her birthday party because I was black,” my sister had told my mom, devastated, after coming home from third grade as the only classmate who had not been invited to the party. Although my sister is not black, she is a dark-skinned Mexican, and brown-skinned people in Mexico are thought of as being a lower class and commonly referred to as “negros.” When my mom found out who had been discriminating against my sister, she later informed me that the girl’s mother had also bullied my mom about her skin tone when she was in elementary school in Mexico City.

Through this situation, I learned the impact people’s upbringing and the values they are taught at home have on their beliefs and, therefore, their actions.

Anna has been accepted at Northeastern University and is waiting to hear from others.

Research was contributed by Asmaa Elkeurti, Aidan Gardiner, Pierre-Antoine Louis and Jake Frankenfield.

Anemona Hartocollis is a national correspondent, covering higher education. She is also the author of the book, “Seven Days of Possibilities: One Teacher, 24 Kids, and the Music That Changed Their Lives Forever.” More about Anemona Hartocollis

COVID-19: Where we’ve been, where we are, and where we’re going

One of the hardest things to deal with in this type of crisis is being able to go the distance. Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel

Where we're going

Living with covid-19, people & organizations, sustainable, inclusive growth, related collection.

The Next Normal: Emerging stronger from the coronavirus pandemic

Writing about COVID-19 in a college admission essay

by: Venkates Swaminathan | Updated: September 14, 2020

Print article

For students applying to college using the CommonApp, there are several different places where students and counselors can address the pandemic’s impact. The different sections have differing goals. You must understand how to use each section for its appropriate use.

The CommonApp COVID-19 question

First, the CommonApp this year has an additional question specifically about COVID-19 :

Community disruptions such as COVID-19 and natural disasters can have deep and long-lasting impacts. If you need it, this space is yours to describe those impacts. Colleges care about the effects on your health and well-being, safety, family circumstances, future plans, and education, including access to reliable technology and quiet study spaces. Please use this space to describe how these events have impacted you.

This question seeks to understand the adversity that students may have had to face due to the pandemic, the move to online education, or the shelter-in-place rules. You don’t have to answer this question if the impact on you wasn’t particularly severe. Some examples of things students should discuss include:

- The student or a family member had COVID-19 or suffered other illnesses due to confinement during the pandemic.

- The candidate had to deal with personal or family issues, such as abusive living situations or other safety concerns

- The student suffered from a lack of internet access and other online learning challenges.

- Students who dealt with problems registering for or taking standardized tests and AP exams.

Jeff Schiffman of the Tulane University admissions office has a blog about this section. He recommends students ask themselves several questions as they go about answering this section:

- Are my experiences different from others’?

- Are there noticeable changes on my transcript?

- Am I aware of my privilege?

- Am I specific? Am I explaining rather than complaining?

- Is this information being included elsewhere on my application?

If you do answer this section, be brief and to-the-point.

Counselor recommendations and school profiles

Second, counselors will, in their counselor forms and school profiles on the CommonApp, address how the school handled the pandemic and how it might have affected students, specifically as it relates to:

- Grading scales and policies

- Graduation requirements

- Instructional methods

- Schedules and course offerings

- Testing requirements

- Your academic calendar

- Other extenuating circumstances

Students don’t have to mention these matters in their application unless something unusual happened.

Writing about COVID-19 in your main essay

Write about your experiences during the pandemic in your main college essay if your experience is personal, relevant, and the most important thing to discuss in your college admission essay. That you had to stay home and study online isn’t sufficient, as millions of other students faced the same situation. But sometimes, it can be appropriate and helpful to write about something related to the pandemic in your essay. For example:

- One student developed a website for a local comic book store. The store might not have survived without the ability for people to order comic books online. The student had a long-standing relationship with the store, and it was an institution that created a community for students who otherwise felt left out.

- One student started a YouTube channel to help other students with academic subjects he was very familiar with and began tutoring others.

- Some students used their extra time that was the result of the stay-at-home orders to take online courses pursuing topics they are genuinely interested in or developing new interests, like a foreign language or music.

Experiences like this can be good topics for the CommonApp essay as long as they reflect something genuinely important about the student. For many students whose lives have been shaped by this pandemic, it can be a critical part of their college application.

Want more? Read 6 ways to improve a college essay , What the &%$! should I write about in my college essay , and Just how important is a college admissions essay? .

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How our schools are (and aren't) addressing race

The truth about homework in America

What should I write my college essay about?

What the #%@!& should I write about in my college essay?

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- NCERT solutions for Class 9

- NCERT solutions for Class 8

- NCERT Solutions for Class 7

- JEE Main 2024

- MHT CET 2024

- JEE Advanced 2024

- BITSAT 2024

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Main Question Paper

- JEE Main Cutoff

- JEE Main Answer Key

- SRMJEEE Result

- Download E-Books and Sample Papers

- Compare Colleges

- B.Tech College Applications

- JEE Advanced Registration

- MAH MBA CET Exam

- View All Management Exams

Colleges & Courses

- MBA College Admissions

- MBA Colleges in India

- Top IIMs Colleges in India

- Top Online MBA Colleges in India

- MBA Colleges Accepting XAT Score

- BBA Colleges in India

- XAT College Predictor 2024

- SNAP College Predictor

- NMAT College Predictor

- MAT College Predictor 2024

- CMAT College Predictor 2024

- CAT Percentile Predictor 2023

- CAT 2023 College Predictor

- CMAT 2024 Registration

- TS ICET 2024 Registration

- CMAT Exam Date 2024

- MAH MBA CET Cutoff 2024

- Download Helpful Ebooks

- List of Popular Branches

- QnA - Get answers to your doubts

- IIM Fees Structure

- AIIMS Nursing

- Top Medical Colleges in India

- Top Medical Colleges in India accepting NEET Score

- Medical Colleges accepting NEET

- List of Medical Colleges in India

- List of AIIMS Colleges In India

- Medical Colleges in Maharashtra

- Medical Colleges in India Accepting NEET PG

- NEET College Predictor

- NEET PG College Predictor

- NEET MDS College Predictor

- DNB CET College Predictor

- DNB PDCET College Predictor

- NEET Admit Card 2024

- NEET PG Application Form 2024

- NEET Cut off

- NEET Online Preparation

- Download Helpful E-books

- LSAT India 2024

- Colleges Accepting Admissions

- Top Law Colleges in India

- Law College Accepting CLAT Score

- List of Law Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Delhi

- Top Law Collages in Indore

- Top Law Colleges in Chandigarh

- Top Law Collages in Lucknow

Predictors & E-Books

- CLAT College Predictor

- MHCET Law ( 5 Year L.L.B) College Predictor

- AILET College Predictor

- Sample Papers

- Compare Law Collages

- Careers360 Youtube Channel

- CLAT Syllabus 2025

- CLAT Previous Year Question Paper

- AIBE 18 Result 2023

- NID DAT Exam

- Pearl Academy Exam

Predictors & Articles

- NIFT College Predictor

- UCEED College Predictor

- NID DAT College Predictor

- NID DAT Syllabus 2025

- NID DAT 2025

- Design Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in India

- Top Interior Design Colleges in India

- Top Graphic Designing Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in Delhi

- Fashion Design Colleges in Mumbai

- Fashion Design Colleges in Bangalore

- Top Interior Design Colleges in Bangalore

- NIFT Result 2024

- NIFT Fees Structure

- NIFT Syllabus 2025

- Free Design E-books

- List of Branches

- Careers360 Youtube channel

- IPU CET BJMC

- JMI Mass Communication Entrance Exam

- IIMC Entrance Exam

- Media & Journalism colleges in Delhi

- Media & Journalism colleges in Bangalore

- Media & Journalism colleges in Mumbai

- List of Media & Journalism Colleges in India

- CA Intermediate

- CA Foundation

- CS Executive

- CS Professional

- Difference between CA and CS

- Difference between CA and CMA

- CA Full form

- CMA Full form

- CS Full form

- CA Salary In India

Top Courses & Careers

- Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com)

- Master of Commerce (M.Com)

- Company Secretary

- Cost Accountant

- Charted Accountant

- Credit Manager

- Financial Advisor

- Top Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Government Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Private Commerce Colleges in India

- Top M.Com Colleges in Mumbai

- Top B.Com Colleges in India

- IT Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- IT Colleges in Uttar Pradesh

- MCA Colleges in India

- BCA Colleges in India

Quick Links

- Information Technology Courses

- Programming Courses

- Web Development Courses

- Data Analytics Courses

- Big Data Analytics Courses

- RUHS Pharmacy Admission Test

- Top Pharmacy Colleges in India

- Pharmacy Colleges in Pune

- Pharmacy Colleges in Mumbai

- Colleges Accepting GPAT Score

- Pharmacy Colleges in Lucknow

- List of Pharmacy Colleges in Nagpur

- GPAT Result

- GPAT 2024 Admit Card

- GPAT Question Papers

- NCHMCT JEE 2024

- Mah BHMCT CET

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Delhi

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Hyderabad

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Maharashtra

- B.Sc Hotel Management

- Hotel Management

- Diploma in Hotel Management and Catering Technology

Diploma Colleges

- Top Diploma Colleges in Maharashtra

- UPSC IAS 2024

- SSC CGL 2024

- IBPS RRB 2024

- Previous Year Sample Papers

- Free Competition E-books

- Sarkari Result

- QnA- Get your doubts answered

- UPSC Previous Year Sample Papers

- CTET Previous Year Sample Papers

- SBI Clerk Previous Year Sample Papers

- NDA Previous Year Sample Papers

Upcoming Events

- NDA Application Form 2024

- UPSC IAS Application Form 2024

- CDS Application Form 2024

- CTET Admit card 2024

- HP TET Result 2023

- SSC GD Constable Admit Card 2024

- UPTET Notification 2024

- SBI Clerk Result 2024

Other Exams

- SSC CHSL 2024

- UP PCS 2024

- UGC NET 2024

- RRB NTPC 2024

- IBPS PO 2024

- IBPS Clerk 2024

- IBPS SO 2024

- Top University in USA

- Top University in Canada

- Top University in Ireland

- Top Universities in UK

- Top Universities in Australia

- Best MBA Colleges in Abroad

- Business Management Studies Colleges

Top Countries

- Study in USA

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in Australia

- Study in Ireland

- Study in Germany

- Study in China

- Study in Europe

Student Visas

- Student Visa Canada

- Student Visa UK

- Student Visa USA

- Student Visa Australia

- Student Visa Germany

- Student Visa New Zealand

- Student Visa Ireland

- CUET PG 2024

- IGNOU B.Ed Admission 2024

- DU Admission 2024

- UP B.Ed JEE 2024

- LPU NEST 2024

- IIT JAM 2024

- IGNOU Online Admission 2024

- Universities in India

- Top Universities in India 2024

- Top Colleges in India

- Top Universities in Uttar Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Bihar

- Top Universities in Madhya Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Tamil Nadu 2024

- Central Universities in India

- CUET Exam City Intimation Slip 2024

- IGNOU Date Sheet

- CUET Mock Test 2024

- CUET Admit card 2024

- CUET PG Syllabus 2024

- CUET Participating Universities 2024

- CUET Previous Year Question Paper

- CUET Syllabus 2024 for Science Students

- E-Books and Sample Papers

- CUET Exam Pattern 2024

- CUET Exam Date 2024

- CUET Syllabus 2024

- IGNOU Exam Form 2024

- IGNOU Result

- CUET Courses List 2024

Engineering Preparation

- Knockout JEE Main 2024

- Test Series JEE Main 2024

- JEE Main 2024 Rank Booster

Medical Preparation

- Knockout NEET 2024

- Test Series NEET 2024

- Rank Booster NEET 2024

Online Courses

- JEE Main One Month Course

- NEET One Month Course

- IBSAT Free Mock Tests

- IIT JEE Foundation Course

- Knockout BITSAT 2024

- Career Guidance Tool

Top Streams

- IT & Software Certification Courses

- Engineering and Architecture Certification Courses

- Programming And Development Certification Courses

- Business and Management Certification Courses

- Marketing Certification Courses

- Health and Fitness Certification Courses

- Design Certification Courses

Specializations

- Digital Marketing Certification Courses

- Cyber Security Certification Courses

- Artificial Intelligence Certification Courses

- Business Analytics Certification Courses

- Data Science Certification Courses

- Cloud Computing Certification Courses

- Machine Learning Certification Courses

- View All Certification Courses

- UG Degree Courses

- PG Degree Courses

- Short Term Courses

- Free Courses

- Online Degrees and Diplomas

- Compare Courses

Top Providers

- Coursera Courses

- Udemy Courses

- Edx Courses

- Swayam Courses

- upGrad Courses

- Simplilearn Courses

- Great Learning Courses

Covid 19 Essay in English

Essay on Covid -19: In a very short amount of time, coronavirus has spread globally. It has had an enormous impact on people's lives, economy, and societies all around the world, affecting every country. Governments have had to take severe measures to try and contain the pandemic. The virus has altered our way of life in many ways, including its effects on our health and our economy. Here are a few sample essays on ‘CoronaVirus’.

100 Words Essay on Covid 19

200 words essay on covid 19, 500 words essay on covid 19.

COVID-19 or Corona Virus is a novel coronavirus that was first identified in 2019. It is similar to other coronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, but it is more contagious and has caused more severe respiratory illness in people who have been infected. The novel coronavirus became a global pandemic in a very short period of time. It has affected lives, economies and societies across the world, leaving no country untouched. The virus has caused governments to take drastic measures to try and contain it. From health implications to economic and social ramifications, COVID-19 impacted every part of our lives. It has been more than 2 years since the pandemic hit and the world is still recovering from its effects.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the world has been impacted in a number of ways. For one, the global economy has taken a hit as businesses have been forced to close their doors. This has led to widespread job losses and an increase in poverty levels around the world. Additionally, countries have had to impose strict travel restrictions in an attempt to contain the virus, which has resulted in a decrease in tourism and international trade. Furthermore, the pandemic has put immense pressure on healthcare systems globally, as hospitals have been overwhelmed with patients suffering from the virus. Lastly, the outbreak has led to a general feeling of anxiety and uncertainty, as people are fearful of contracting the disease.

My Experience of COVID-19

I still remember how abruptly colleges and schools shut down in March 2020. I was a college student at that time and I was under the impression that everything would go back to normal in a few weeks. I could not have been more wrong. The situation only got worse every week and the government had to impose a lockdown. There were so many restrictions in place. For example, we had to wear face masks whenever we left the house, and we could only go out for essential errands. Restaurants and shops were only allowed to operate at take-out capacity, and many businesses were shut down.

In the current scenario, coronavirus is dominating all aspects of our lives. The coronavirus pandemic has wreaked havoc upon people’s lives, altering the way we live and work in a very short amount of time. It has revolutionised how we think about health care, education, and even social interaction. This virus has had long-term implications on our society, including its impact on mental health, economic stability, and global politics. But we as individuals can help to mitigate these effects by taking personal responsibility to protect themselves and those around them from infection.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Education

The outbreak of coronavirus has had a significant impact on education systems around the world. In China, where the virus originated, all schools and universities were closed for several weeks in an effort to contain the spread of the disease. Many other countries have followed suit, either closing schools altogether or suspending classes for a period of time.

This has resulted in a major disruption to the education of millions of students. Some have been able to continue their studies online, but many have not had access to the internet or have not been able to afford the costs associated with it. This has led to a widening of the digital divide between those who can afford to continue their education online and those who cannot.

The closure of schools has also had a negative impact on the mental health of many students. With no face-to-face contact with friends and teachers, some students have felt isolated and anxious. This has been compounded by the worry and uncertainty surrounding the virus itself.

The situation with coronavirus has improved and schools have been reopened but students are still catching up with the gap of 2 years that the pandemic created. In the meantime, governments and educational institutions are working together to find ways to support students and ensure that they are able to continue their education despite these difficult circumstances.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Economy

The outbreak of the coronavirus has had a significant impact on the global economy. The virus, which originated in China, has spread to over two hundred countries, resulting in widespread panic and a decrease in global trade. As a result of the outbreak, many businesses have been forced to close their doors, leading to a rise in unemployment. In addition, the stock market has taken a severe hit.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Health

The effects that coronavirus has on one's health are still being studied and researched as the virus continues to spread throughout the world. However, some of the potential effects on health that have been observed thus far include respiratory problems, fever, and coughing. In severe cases, pneumonia, kidney failure, and death can occur. It is important for people who think they may have been exposed to the virus to seek medical attention immediately so that they can be treated properly and avoid any serious complications. There is no specific cure or treatment for coronavirus at this time, but there are ways to help ease symptoms and prevent the virus from spreading.

Applications for Admissions are open.

JEE Main Important Physics formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Physics formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

UPES School of Liberal Studies

Ranked #52 Among Universities in India by NIRF | Up to 30% Merit-based Scholarships | Lifetime placement assistance

Aakash iACST Scholarship Test 2024

Get up to 90% scholarship on NEET, JEE & Foundation courses

JEE Main Important Chemistry formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Chemistry formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

PACE IIT & Medical, Financial District, Hyd

Enrol in PACE IIT & Medical, Financial District, Hyd for JEE/NEET preparation

ALLEN JEE Exam Prep

Start your JEE preparation with ALLEN

Download Careers360 App's

Regular exam updates, QnA, Predictors, College Applications & E-books now on your Mobile

Certifications

We Appeared in

Essay on COVID-19 Pandemic

As a result of the COVID-19 (Coronavirus) outbreak, daily life has been negatively affected, impacting the worldwide economy. Thousands of individuals have been sickened or died as a result of the outbreak of this disease. When you have the flu or a viral infection, the most common symptoms include fever, cold, coughing up bone fragments, and difficulty breathing, which may progress to pneumonia. It’s important to take major steps like keeping a strict cleaning routine, keeping social distance, and wearing masks, among other things. This virus’s geographic spread is accelerating (Daniel Pg 93). Governments restricted public meetings during the start of the pandemic to prevent the disease from spreading and breaking the exponential distribution curve. In order to avoid the damage caused by this extremely contagious disease, several countries quarantined their citizens. However, this scenario had drastically altered with the discovery of the vaccinations. The research aims to investigate the effect of the Covid-19 epidemic and its impact on the population’s well-being.

There is growing interest in the relationship between social determinants of health and health outcomes. Still, many health care providers and academics have been hesitant to recognize racism as a contributing factor to racial health disparities. Only a few research have examined the health effects of institutional racism, with the majority focusing on interpersonal racial and ethnic prejudice Ciotti et al., Pg 370. The latter comprises historically and culturally connected institutions that are interconnected. Prejudice is being practiced in a variety of contexts as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak. In some ways, the outbreak has exposed pre-existing bias and inequity.

Thousands of businesses are in danger of failure. Around 2.3 billion of the world’s 3.3 billion employees are out of work. These workers are especially susceptible since they lack access to social security and adequate health care, and they’ve also given up ownership of productive assets, which makes them highly vulnerable. Many individuals lose their employment as a result of lockdowns, leaving them unable to support their families. People strapped for cash are often forced to reduce their caloric intake while also eating less nutritiously (Fraser et al, Pg 3). The epidemic has had an impact on the whole food chain, revealing vulnerabilities that were previously hidden. Border closures, trade restrictions, and confinement measures have limited farmer access to markets, while agricultural workers have not gathered crops. As a result, the local and global food supply chain has been disrupted, and people now have less access to healthy foods. As a consequence of the epidemic, many individuals have lost their employment, and millions more are now in danger. When breadwinners lose their jobs, become sick, or die, the food and nutrition of millions of people are endangered. Particularly severely hit are the world’s poorest small farmers and indigenous peoples.

Infectious illness outbreaks and epidemics have become worldwide threats due to globalization, urbanization, and environmental change. In developed countries like Europe and North America, surveillance and health systems monitor and manage the spread of infectious illnesses in real-time. Both low- and high-income countries need to improve their public health capacities (Omer et al., Pg 1767). These improvements should be financed using a mix of national and foreign donor money. In order to speed up research and reaction for new illnesses with pandemic potential, a global collaborative effort including governments and commercial companies has been proposed. When working on a vaccine-like COVID-19, cooperation is critical.

The epidemic has had an impact on the whole food chain, revealing vulnerabilities that were previously hidden. Border closures, trade restrictions, and confinement measures have limited farmer access to markets, while agricultural workers have been unable to gather crops. As a result, the local and global food supply chain has been disrupted, and people now have less access to healthy foods (Daniel et al.,Pg 95) . As a consequence of the epidemic, many individuals have lost their employment, and millions more are now in danger. When breadwinners lose their jobs, the food and nutrition of millions of people are endangered. Particularly severely hit are the world’s poorest small farmers and indigenous peoples.

While helping to feed the world’s population, millions of paid and unpaid agricultural laborers suffer from high levels of poverty, hunger, and bad health, as well as a lack of safety and labor safeguards, as well as other kinds of abuse at work. Poor people, who have no recourse to social assistance, must work longer and harder, sometimes in hazardous occupations, endangering their families in the process (Daniel Pg 96). When faced with a lack of income, people may turn to hazardous financial activities, including asset liquidation, predatory lending, or child labor, to make ends meet. Because of the dangers they encounter while traveling, working, and living abroad; migrant agricultural laborers are especially vulnerable. They also have a difficult time taking advantage of government assistance programs.