Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Drug Addiction — Drug Addiction: Choice or Disease?

Drug Addiction: Choice Or Disease?

- Categories: Drug Addiction Drugs

About this sample

Words: 677 |

Published: Sep 16, 2023

Words: 677 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

The choice argument, the disease model, psychological and sociological factors, a holistic perspective.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1976 words

3 pages / 1587 words

5 pages / 2094 words

3 pages / 1486 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Drug Addiction

Drug abuse is a chronic disorder that has been a major problem affecting many people, especially the youth, for several decades. This problem has become a global concern that requires immediate attention, especially given the [...]

The issue of substance abuse presents a pervasive and multifaceted challenge, impacting individuals, families, and communities globally. Its consequences extend far beyond individual suffering, posing significant threats to [...]

Drug addiction has been a significant issue worldwide for many decades, impacting not only individuals addicted to illegal substances but also the society surrounding them. This essay aims to explore the influence of drug [...]

Millions of individuals are affected by the devastating consequences of substance abuse, making it a significant public health concern worldwide. As societies strive to address this issue, innovations in technology have emerged [...]

Drugabuse.gov. (2023). Commonly Abused Drugs Charts. National Institute on Drug Abuse. National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2022). Understanding Drug Use and Addiction DrugFacts. Retrieved from Press.

Teenage drug abuse is a deeply concerning issue that continues to cast a shadow over the lives of young Americans and their communities. As we grapple with this persistent challenge, it is essential to conduct an in-depth [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- 5-Star Facility Tour

Is Addiction a Disease or Choice?

Addiction itself is often misunderstood. Some people argue that i t is a personal choice , and therefore anyone who is addicted to a substance has ended up there because of the lack of self-discipline or morality. Meanwhile others argue addiction is a disease, and as a result cannot be cured entirely or even resisted by discipline alone. The first view has been the most common understanding of addiction throughout history, and as a result there is a stigma surrounding people who struggle with drug abuse that often prevents them from willingly seeking help.

Recent studies over the past couple decades have brought evidence to question that understanding, and now the nature of addiction has become a common point of debate among specialists and the public itself . Does a person become locked into addiction because it is a choice that they are making and continue to make, or is it a disease that warps their brain and takes choice out of the equation? These are the two si des of the addiction debate , and which side wins plays a critical role in how medical professionals should approach addiction treatment .

The Misconception of Addiction

Much of the argument that addiction is a choice stems from misconceptions about the types of people who suffer from addiction. This is ti ed to th e stigma of addiction , which developed as a result of the individuals who were affected by addiction, such as people from specific social classes or ethnicities. Throughout history, substance abuse was most common among “ lesser” classes and people with l ower levels of education. Given that the scientists and researchers of the time were from a more prominent social class where addiction was less common, they drew a connection that poverty and a lack of education was the reason that these individuals were more likely to develop an addiction.

While this stigma is still common today, modern addiction can affect any person regardless of their socioeconomic class, ethnicity, and background. One use is all it takes for some drugs to set a person on the wrong course, and even legal drugs such as prescription opioids can easily catapult addiction if they are misused. This means that anyone wi th access to medical care is potentially at risk , and so long as old misconceptions continue to prevail, they are in greater danger than they would otherwise be .

Addiction as a Choice

Beyond the stigma, t here is a branch of modern researchers that strongly insists that addiction is a choice and uses evidence to support their argument . The primary figures on this side are behavioral scientists, and their belief is based on the idea that any activity capable of stimulating a person for pleasure or stress release holds a risk for addiction. This means that almost anything can potentially lead to an addiction, be it taking drugs, eating, or simply spending time on the internet. One of the ir most common arguments shines light on social media addiction. As social media has become a staple in modern society, many people have become hooked on this growing trend.

According to the neuroscientist Dr. Marc Lewis, this argument is largely based on the idea that when a person carries out an activity that they enjoy, it triggers pleasure in the brain and over time becomes a habitual act. Similar to how a person who wakes up at the same time most days for work , these processes easily become habit over time.

The main difference though is that that since it is connected to pleasure, which is the brain’s natural agent to tell the body what is good or bad for survival on a primal level, these habits form quicker and become more powerful than they otherwise would. A key point is that pleasure in this case does not necessarily need to be pleasure in the traditional sense, rather would be more accurately described as positive stimuli. This means that activities that do not cause pleasure but provide relief from negative feelings also present a strong habit-forming risk.

From a psychological standpoint, when this happens the brain has created special pathways for the activity to make it an easier trigger for that positive stimuli within the individual. Since drug us e frequently causes a wave of pleasure or at the very least relief from a negative feeling, these behavioral scientists argue that addiction is a case of repeated choice rather than a disorder. If an addict finds the self-control to stop using their chosen substance, t he expected result of this belief system is that the brain can fully recovery from addiction and eventually proceed in life as if it never occurred.

Addiction as a Disease

In recent decades, researchers began to label addiction as a disease rather than a behavioral choice. This decision stems primarily from how addiction a ffects the brain by changing it, progressively forcing an individual to crave the drug until use eventually becomes an unconscious act rather than a conscio us choice.

W hen a person begins abusing a substance or regularly us es prescription drugs for too long, their body will begin to adapt itself to account for its presence in order to maintain homeostasis , or balance . Over time, this leads to what is known as tolerance , which is when the body has adjusted itself enough that the individual will need to take more of their chosen drug in order to experience the same effects. This encourages them to further abuse the drug, and as this is happening, the individual’s brain will also be rewiring itself to desire more.

Eventually this leads to the development of dependence , which means that their body has been altered so much that it loses the ability to function normally without their chosen substance. If use stops , they will experience a series of painful side effects known as withdrawal , until either their body returns to its normal state without drugs or when they use again. The first option may take several days or weeks to accomplish, so many people opt for the latter as it is less painful . By choosing this option, the user becomes locked in a progressive cycle of addiction.

During this point, the part of the brain responsible for deciding to take the drug also shifts from the front of the brain to the back, which is the area in charge of regulating unconscious acts like breathing and blinking , as well as basic desires like hunger. As a result, drug abuse becomes fundamentally linked to their brain and is no longer a free choice.

To further complicate matters, some people are more prone to addiction than other s . One of the most common signs for determining if someone is as risk for addiction is to uncover whether there is a history of past addiction in their family. This supports the argument that addiction is a disease because if choice was the main factor in addiction, a person’s family history would have little bearing on their chance for becoming addicted as well.

Wrapping Up

A ddiction is a complicated subject filled with debate between researchers and scientists from a variety of backgrounds, and these debates have only grown as the years progress . Despite the complexity of the situation however, new evidence reveals the truth of the matter. While an addiction may begin from an individual’s personal choice, addiction itself is a mental disease rather than a continued choice.

The reason for this comes from t hree key points regarding how addiction affects an addict . The first of which is that a mental disease alters an individual’s brain and impacts their ability to function normally , and the second is that instead of returning to “ normal ” after treatment , a recovered individual will have to consciously work toward remaining sober each day, as relapse is always a possibility . The third point of note is that a person’s risk of addiction rises based on hereditary factors. If addiction were purely a choice, these three points would not exist al together.

Behavioral researchers like Dr. Lewis try to argue this by acknowledg ing that the brain does change during addiction, but they view it as a situation like playing with clay. The brain is altered by drugs , making poor choices more likely, but they believe that if the drugs are removed, the brain will eventually “remold” itself back to its normal shape.

However , many scientists now know that this does not happen, which is where th is argument quickly falls apart . Instead of returning to normal and no long being a problem, addiction is a process of ongoing recovery. Even years after being sober, a person who was once an addict will be at a higher risk for drug abuse than their peers who were never addicted. This is because the brain only reverts to normal functionality, but its makeup remains changed enough that recovering individuals can always struggle with temptation.

Choice argument s are also unable to account for the role of heredity in a person’s risk factors for developing an addiction. Once again, if it were solely choice based, addiction would affect each person as an individual and their family history would play no significant role.

As a disease, addiction is more difficult to treat than it would be if it were purely a choice. However, by recognizing it for what it really is, medical professionals can develop treatment plans that are more effective for helping their patients.

Providing the Highest-Quality of Addiction Treatment

Here at Brookdale Premier Addiction Recovery, we understand the complexity of substance use disorder and recognize the need for comprehensive treatment services . As such, every individual that comes to us for help, is treated with the highest level of compassion and understanding they deserve to materiali ze their potential into a Life…Recovered .

With customized detox protocols and clinical treatment strategies, our team of professionals wi ll work one-on-one with you to address your very specific needs and tailor of programs to best help you. If you are struggling with alcoholism or addiction, help is only one phone call away. Please contact us now at (855)575-1292 to learn more about our program or to begin the process of admission.

EXPERIENCE BROOKDALE - TOUR OUR 5-STAR FACILITY.

Drug Addiction: A Disease or a Choice?

Introduction, argument for, argument against, evaluation of arguments.

Despite numerous attempts to address the problem, drug addiction remains a serious health concern for contemporary society. Many thousands of individuals suffer from this issue and face the high risk of reduced quality of life or death. Although there is a long history of the problem, the is still a difference in opinions on whether drug addiction should be viewed as a disease requiring treatment or an individual’s choice. Today, numerous investigators offer their perspectives on the problem, supporting their assumptions with solid evidence and arguments. These views impact the attitudes to treatment, rehabilitation, and recovery.

The idea that drug addiction should be viewed as a disease is supported in the article “Addiction as a brain disease revised: why it still matters, and the need for consilience.” Heilig et al. (2021) assume that denying the fact that addiction is a severe brain disease might cause serious damage to populations suffering from this condition, as they will have limited access to healthcare services. The central idea introduced by the authors is that addiction promotes specific alterations in the brain’s work, meaning that it is critical to address the issue from the perspective of neuroscience (Heilig et al., 2021). It will help to acquire positive results and ideas for better treatment.

The premises of the authors’ argument are strongly supported by the existing research. Heilig et al. (2021) show that even if the initial decision to use drugs was conscious, a person acquires specific changes in brain function, leading to the development of the chronic and relapsing form of the disease. This statement is supported by the facts from neuroscience and recent investigations. As a result, the argument offered by the researchers is strong, and their assumption is justified by the existing body of knowledge, which makes it a potent source.

Moreover, the authors follow the logic while presenting the main arguments and discussing them from various perspectives. For instance, Heilig et al. (2021) say that following the traditional definition of the disease, drug use might not be viewed as an illness. Moreover, they appeal to the ideas introduced by Jellinek in his classic book, who views the state as a condition that should be analyzed and investigated (Heilig et al., 2021). However, the given assumption is followed by the existing evidence from the field of neuroscience, stating that addiction can be considered a chronic relapsing disease because of the observed changes in the brain and its function (Heilig et al., 2021). It helps to resist the opponents of the idea and refute their arguments.

Finally, another strength of the paper is that the authors avoid making narrowed conclusions. They accept the strengths of other parties’ arguments and offer the idea of considering drug addiction a critical problem that might benefit from combining various approaches to its management (Heilig et al., 2021). As a result, it is possible to compromise and agree on a multi-dimensional approach, which might help move forward and improve the current understanding of dependence and how to help individuals with this condition.

The opposing argument to the position described above is introduced by Lewis in the article “Addiction and the brain: Development, not disease”. In the academic, peer-reviewed article, the author speaks about the brain disease model, which is cultivated by medical authorities, and offers his counterarguments. The central idea offered by Lewis (2017) is that the disease model fails because the brain changes observed in addicted individuals are similar to those emerging during the development of deep habits, or Pavlovian learning. In other words, a person using drugs cultivates specific changes in brain function by his/her actions.

In such a way, the author emphasizes the idea that drug addiction should be viewed as a choice of an individual. The given assumption is linked to the ideas of self-organization and personality development. The author avoids introducing arguments without strong support from the current body of literature and appropriate research. Using the brain disease model as the basis for his cogitations, Lewis (2017) moves forward to introduce counterarguments and explain them by appealing to the existing studies in the field of addiction. It makes the ideas offered by the researcher stronger and helps to understand his central claims.

Moreover, the premises of the argument offered by the researcher are supported by the conclusion and the main ideas offered by him. Thus, Lewis (2017) moves from the idea of addiction as a brain disease to the opposite perspective by considering existing claims and factors supporting every statement. For instance, he says that the short duration of addictive rewards promotes the emergence of negative emotions and makes the learning cycle more effective (Lewis, 2017). It evidences the idea that similar to the acquired habit or skill, drug addiction evolves under the impact of an individual’s decisions and his/her willingness to continue.

In such a way, the author does not leave any assumptions unproven. Offering a particular argument, Lewis supports it with credible evidence from various sources, appealing to other authors or researchers working in the same field. It makes the work more meaningful and allows using it as the argument in the debate linked to the nature of addiction. Moreover, the researcher builds his arguments logically, moving from the discussion of the opposing view to the acceptance of a new one, which helps to understand his claims better. As a result, an enhanced understanding of the issue under research is acquired.

Evaluating the offered arguments, it is vital to admit several important aspects differentiating scholarly sources from popular ones. First of all, the authors use the previous research and support their assumptions with the facts proven by other researchers. For instance, the popular article about addiction lacks this aspect as it offers generalized ideas and leaves many premises unsupported by arguments (“Why is addiction a disease?” n.d.). As a result, popular sources’ quality, credibility, and relevance suffer. For this reason, scholarly papers such as those mentioned above can be used to discuss the problem of drug addiction and conclude about it.

Altogether, the problem of whether drug addiction can be viewed as a disease or a choice remains topical. The selected sources helped to acquire a better understanding of the issue. The arguments offered by the authors are robust and supported by credible evidence. Analyzing these studies, it is possible to conclude that viewing addiction as a disease seems more relevant; however, it is also critical to consider the fact that it depends on a person’s desire to stop using drugs and acquire the necessary treatment. The problem remains complex, and it is necessary to ensure the combined approach is used to address it to help patients.

Heilig, M., MacKillop, J., Martinez, D., Rehm, J., Leggio, L., & Vanderschuren, L. (2021). Addiction as a brain disease revised: why it still matters, and the need for consilience. Neuropsychopharmacology, 46 (10), 1715–1723.

Lewis M. (2017). Addiction and the brain: Development, not disease. Neuroethics , 10 (1), 7–18.

Why is addiction a disease? (2021). Web.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2023, August 3). Drug Addiction: A Disease or a Choice? https://studycorgi.com/drug-addiction-a-disease-or-a-choice/

"Drug Addiction: A Disease or a Choice?" StudyCorgi , 3 Aug. 2023, studycorgi.com/drug-addiction-a-disease-or-a-choice/.

StudyCorgi . (2023) 'Drug Addiction: A Disease or a Choice'. 3 August.

1. StudyCorgi . "Drug Addiction: A Disease or a Choice?" August 3, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/drug-addiction-a-disease-or-a-choice/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Drug Addiction: A Disease or a Choice?" August 3, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/drug-addiction-a-disease-or-a-choice/.

StudyCorgi . 2023. "Drug Addiction: A Disease or a Choice?" August 3, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/drug-addiction-a-disease-or-a-choice/.

This paper, “Drug Addiction: A Disease or a Choice?”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: August 3, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Addiction Is a Choice

Many activities that are not themselves diseases can cause diseases, and a foolish, self-destructive activity is not necessarily a disease. When we find a parallel between physiological processes and mental or personality processes, we can mistakenly assume the physiological process is what is really going on, and the mental process is just a passive result of the physical process.

(Please see Counterpoint article by by John H. Halpern, M.D.)

Is addiction a disease, or is it a choice? To think clearly about this question, we need to make a sharp distinction between an activity and its results. Many activities that are not themselves diseases can cause diseases. And a foolish, self-destructive activity is not necessarily a disease.

With those two vital points in mind, we observe a person ingesting some substance: alcohol, nicotine, cocaine or heroin. We have to decide, not whether this pattern of consumption causes disease nor whether it is foolish and self-destructive, but rather whether it is something altogether distinct and separate: Is this pattern of drug consumption itself a disease?

Scientifically, the contention that addiction is a disease is empirically unsupported. Addiction is a behavior and thus clearly intended by the individual person. What is obvious to common sense has been corroborated by pertinent research for years (Table 1).

The person we call an addict always monitors their rate of consumption in relation to relevant circumstances. For example, even in the most desperate, chronic cases, alcoholics never drink all the alcohol they can. They plan ahead, carefully nursing themselves back from the last drinking binge while deliberately preparing for the next one. This is not to say that their conduct is wise, simply that they are in control of what they are doing. Not only is there no evidence that they cannot moderate their drinking, there is clear evidence that they do so, rationally responding to incentives devised by hospital researchers. Again, the evidence supporting this assertion has been known in the scientific community for years (Table 2).

My book Addiction Is a Choice was criticized in a recent review in a British scholarly journal of addiction studies because it states the obvious (Davidson, 2001). According to the reviewer, everyone in the addiction field now knows that addiction is a choice and not a disease, and I am, therefore, "violently pushing against a door which was opened decades ago." I'm delighted to hear that addiction specialists in Britain are so enlightened and that there is no need for me to argue my case over there.

In the United States, we have not made so much progress. Why do some persist, in the face of all reason and all evidence, in pushing the disease model as the best explanation for addiction?

I conjecture that the answer lies in a fashionable conception of the relation between mind and body. There are several competing philosophical theories about that relation. Let us accept, for the sake of argument, the most extreme "materialist" theory: the psychophysical identity theory. Accordingly, every mental event corresponds to a physical event, because it is a physical event. The relation between mind and the relevant parts of the body is, therefore, like the relation between heat and molecular motion: They are precisely the same thing, observed in two different ways. As it happens, I find this view of the relation between mind and body very congenial.

However, I think it is often accompanied by a serious misunderstanding: the notion that when we find a parallel between physiological processes and mental or personality processes, the physiological process is what is really going on and the mental process is just a passive result of the physical process. What this overlooks is the reality of downward causation , the phenomenon in which an emergent property of a system can govern the position of elements within the system (Campbell, 1974; Sperry, 1969). Thus, the complex, symmetrical, six-pointed design of a snow crystal largely governs the position of each molecule of ice in that crystal.

Hence, there is no theoretical obstacle to acknowledging the fact that thoughts, desires, values and other mental phenomena can dominate bodily functions. Suppose that a man's mother dies, and he undergoes the agonizing trauma we call unbearable grief . There is no doubt that if we examine this man's bodily processes we will find many physical changes, among them changes in his blood and stomach chemistry. It would be clearly wrong to say that these bodily changes cause him to be grief-stricken. It would be less misleading to say that his being grief-stricken causes the bodily changes, but this is also not entirely accurate. His knowledge of his mother's death (interacting with his prior beliefs and values) causes his grief, and his grief has blood-sugar and gastric concomitants, among many others.

There is no dispute that various substances cause physiological changes in the bodies of people who ingest them. There is also no dispute, in principle, that these physiological changes may themselves change with repeated doses, nor that these changes may be correlated with subjective mental states like reward or enjoyment.

I say "in principle" because I suspect that people sometimes tend to run away with these supposed correlations. For example, changes in dopamine levels have often been hypothesized as an integral part of the reward/reinforcement process. Yet research shows that dopamine in the nucleus accumbens does not mediate primary or unconditioned food reward in animals (Aberman and Salamone, 1999; Nowend et al., 2001; Salamone et al., 2001; Salamone et al., 1997). According to Salamone, the theory that drugs of abuse turn on a natural reward system is simplistic and inaccurate: "Dopamine in the nucleus accumbens plays a role in the self-administration of some drugs (i.e., stimulants), but certainly not all" (personal communication, Nov. 26, 2001).

Garris et al. (1999) reached similar conclusions: "Dopamine may therefore be a neural substrate for novelty or reward expectation rather than reward itself." They concluded:

[T]here is no correlation between continual bar pressing during [intracranial self-stimulation] and increased dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbensour results are consistent with evidence that the dopaminergic component is not associated with the hedonistic or 'pleasure' aspects of rewardLikewise, the rewarding effects of cocaine do not require dopamine; mice lacking the gene for the dopamine transporter, a major target of cocaine, will self-administer cocaine. However, increased dopamine neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens shell is seen when rats are transiently exposed to a new environment. The increase in extracellular dopamine quickly returns to normal levels and remains there during continued exploration of the new environmentdopamine release in the nucleus accumbens is related to novelty, predictability or some other aspects of the reward process, rather than to hedonism itself.

Perhaps, then, some people have been too ready to jump to conclusions about specific mechanisms. Be that as it may, chemical rewards have no power to compel--although this notion of compulsion may be a cherished part of clinicians' folklore. I am rewarded every time I eat chocolate cake, but I often eschew this reward because I feel I ought to watch my weight.

Experience with addiction treatment must surely make us even more dubious about the theory that addiction is a disease. The most popular way of helping people manage their addictive behavior is Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and its various 12-step offshoots. Many observers have recognized the essentially religious nature of AA. The U.S. courts are increasingly regarding AA as a religious activity. In United States v Seeger (1965), the U.S. Supreme Court stated that the test to be applied as to whether a belief is religious is to enquire whether that belief "occupies a place in the life of its possessor parallel to that filled by the orthodox belief in God" in religions more widely accepted in the United States. This requirement is met by members of AA and other secular programs that help people with addictive behaviors and encourage their members to turn their will and lives over to the care of a supreme being. What kind of disease is this for which the best available treatment is religion (Antze, 1987)? Clinical applications are based on explanations for why the behavior occurs. An activity based on a religious belief masquerading as a clinical form of treatment tells us something about what the activity really is--an ethical, not medical, problem in living.

What passes as clinical treatment for addiction is psychotherapy, which essentially consists of various forms of conversation or rhetoric (Szasz, 1988). One person, the therapist, tries to influence another person, the patient, to change their values and behavior. While the conversation called therapy can be helpful, most of the conversation that occurs in therapy based on the disease model is potentially harmful. This is because the therapist misleads the patient into believing something that is simply untrue--that addiction is a disease, and, therefore, addicts cannot control their behavior. Preaching this falsehood to patients may encourage them to abandon any attempt to take responsibility for their actions.

The treatment of drug effects, at the patient's request, is well within the domain of medicine, what passes as evidence for the theory that addiction is a disease is merely clinical folklore.

References:

Aberman JE, Salamone JD (1999), Nucleus accumbens dopamine depletions make rats more sensitive to high ratio requirements but do not impair primary food reinforcement. Neuroscience 92(2):545-552.

Antze P (1987), Symbolic action in Alcoholics Anonymous. In: Constructive Drinking: Perspectives on Drink From Anthropology, Douglas M, ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp149-181.

Campbell DT (1974), 'Downward causation' in hierarchically organized biological systems. In: Studies in the Philosophy of Biology: Reduction and Related Problems, Ayala FJ, Dobzhansky T, eds. London: Macmillan.

Davidson R (2001), Conspiracy, cults and choices. Addiction Research & Theory 9(1):92-92 [book review].

Garris PA, Kilpatrick M, Bunin MA et al. (1999), Dissociation of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens from intracranial self-stimulation. Nature 398(6722):67-69.

Nowend KL, Arizzi M, Carlson BB, Salamone JD (2001), D1 or D2 antagonism in nucleus accumbens core or dorsomedial shell suppresses lever pressing for food but leads to compensatory increases in chow consumption. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 69(3-4):373-382.

Salamone JD, Cousins MS, Snyder BJ (1997), Behavioral functions of nucleus accumbens dopamine: empirical and conceptual problems with the anhedonia hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 21(3):341-359.

Salamone JD, Wisniecki A, Carlson BB, Correa M (2001), Nucleus accumbens dopamine depletions make animals highly sensitive to high fixed ratio requirements but do not impair primary food reinforcement. Neuroscience 105(4):863-870.

Sperry W (1969), A modified concept of consciousness. Psychol Rev 76(6):532-536.

Szasz TS (1988), The Myth of Psychotherapy: Mental Healing as Religion, Rhetoric, and Repression. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press.

United States v Seeger, 980 US 163 (1965).

Addiction & Substance Use in Psychiatric Times

How to Talk to Teenagers About Substance Use

National Alcohol Screening Day 2024

Lloyd Sederer, MD: A Conversation About Addiction and the Opioid Epidemic

COVID-19 Research Roundup: March 22, 2024

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Research Roundup: March 15, 2024

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 22 February 2021

Addiction as a brain disease revised: why it still matters, and the need for consilience

- Markus Heilig 1 ,

- James MacKillop ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4118-9500 2 , 3 ,

- Diana Martinez 4 ,

- Jürgen Rehm ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5665-0385 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ,

- Lorenzo Leggio ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7284-8754 9 &

- Louk J. M. J. Vanderschuren ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5379-0363 10

Neuropsychopharmacology volume 46 , pages 1715–1723 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

85k Accesses

97 Citations

322 Altmetric

Metrics details

The view that substance addiction is a brain disease, although widely accepted in the neuroscience community, has become subject to acerbic criticism in recent years. These criticisms state that the brain disease view is deterministic, fails to account for heterogeneity in remission and recovery, places too much emphasis on a compulsive dimension of addiction, and that a specific neural signature of addiction has not been identified. We acknowledge that some of these criticisms have merit, but assert that the foundational premise that addiction has a neurobiological basis is fundamentally sound. We also emphasize that denying that addiction is a brain disease is a harmful standpoint since it contributes to reducing access to healthcare and treatment, the consequences of which are catastrophic. Here, we therefore address these criticisms, and in doing so provide a contemporary update of the brain disease view of addiction. We provide arguments to support this view, discuss why apparently spontaneous remission does not negate it, and how seemingly compulsive behaviors can co-exist with the sensitivity to alternative reinforcement in addiction. Most importantly, we argue that the brain is the biological substrate from which both addiction and the capacity for behavior change arise, arguing for an intensified neuroscientific study of recovery. More broadly, we propose that these disagreements reveal the need for multidisciplinary research that integrates neuroscientific, behavioral, clinical, and sociocultural perspectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

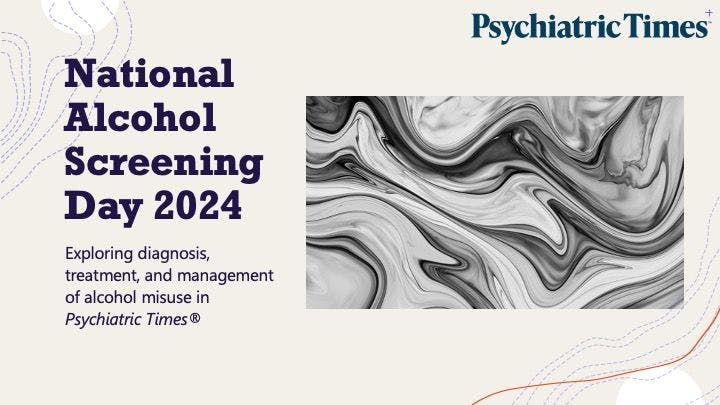

Subtypes in addiction and their neurobehavioral profiles across three functional domains

Gunner Drossel, Leyla R. Brucar, … Anna Zilverstand

Drug addiction: from bench to bedside

Julian Cheron & Alban de Kerchove d’Exaerde

The neurobiology of drug addiction: cross-species insights into the dysfunction and recovery of the prefrontal cortex

Ahmet O. Ceceli, Charles W. Bradberry & Rita Z. Goldstein

Introduction

Close to a quarter of a century ago, then director of the US National Institute on Drug Abuse Alan Leshner famously asserted that “addiction is a brain disease”, articulated a set of implications of this position, and outlined an agenda for realizing its promise [ 1 ]. The paper, now cited almost 2000 times, put forward a position that has been highly influential in guiding the efforts of researchers, and resource allocation by funding agencies. A subsequent 2000 paper by McLellan et al. [ 2 ] examined whether data justify distinguishing addiction from other conditions for which a disease label is rarely questioned, such as diabetes, hypertension or asthma. It concluded that neither genetic risk, the role of personal choices, nor the influence of environmental factors differentiated addiction in a manner that would warrant viewing it differently; neither did relapse rates, nor compliance with treatment. The authors outlined an agenda closely related to that put forward by Leshner, but with a more clinical focus. Their conclusion was that addiction should be insured, treated, and evaluated like other diseases. This paper, too, has been exceptionally influential by academic standards, as witnessed by its ~3000 citations to date. What may be less appreciated among scientists is that its impact in the real world of addiction treatment has remained more limited, with large numbers of patients still not receiving evidence-based treatments.

In recent years, the conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease has come under increasing criticism. When first put forward, the brain disease view was mainly an attempt to articulate an effective response to prevailing nonscientific, moralizing, and stigmatizing attitudes to addiction. According to these attitudes, addiction was simply the result of a person’s moral failing or weakness of character, rather than a “real” disease [ 3 ]. These attitudes created barriers for people with substance use problems to access evidence-based treatments, both those available at the time, such as opioid agonist maintenance, cognitive behavioral therapy-based relapse prevention, community reinforcement or contingency management, and those that could result from research. To promote patient access to treatments, scientists needed to argue that there is a biological basis beneath the challenging behaviors of individuals suffering from addiction. This argument was particularly targeted to the public, policymakers and health care professionals, many of whom held that since addiction was a misery people brought upon themselves, it fell beyond the scope of medicine, and was neither amenable to treatment, nor warranted the use of taxpayer money.

Present-day criticism directed at the conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease is of a very different nature. It originates from within the scientific community itself, and asserts that this conceptualization is neither supported by data, nor helpful for people with substance use problems [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Addressing these critiques requires a very different perspective, and is the objective of our paper. We readily acknowledge that in some cases, recent critiques of the notion of addiction as a brain disease as postulated originally have merit, and that those critiques require the postulates to be re-assessed and refined. In other cases, we believe the arguments have less validity, but still provide an opportunity to update the position of addiction as a brain disease. Our overarching concern is that questionable arguments against the notion of addiction as a brain disease may harm patients, by impeding access to care, and slowing development of novel treatments.

A premise of our argument is that any useful conceptualization of addiction requires an understanding both of the brains involved, and of environmental factors that interact with those brains [ 9 ]. These environmental factors critically include availability of drugs, but also of healthy alternative rewards and opportunities. As we will show, stating that brain mechanisms are critical for understanding and treating addiction in no way negates the role of psychological, social and socioeconomic processes as both causes and consequences of substance use. To reflect this complex nature of addiction, we have assembled a team with expertise that spans from molecular neuroscience, through animal models of addiction, human brain imaging, clinical addiction medicine, to epidemiology. What brings us together is a passionate commitment to improving the lives of people with substance use problems through science and science-based treatments, with empirical evidence as the guiding principle.

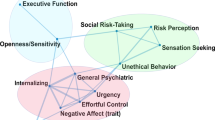

To achieve this goal, we first discuss the nature of the disease concept itself, and why we believe it is important for the science and treatment of addiction. This is followed by a discussion of the main points raised when the notion of addiction as a brain disease has come under criticism. Key among those are claims that spontaneous remission rates are high; that a specific brain pathology is lacking; and that people suffering from addiction, rather than behaving “compulsively”, in fact show a preserved ability to make informed and advantageous choices. In the process of discussing these issues, we also address the common criticism that viewing addiction as a brain disease is a fully deterministic theory of addiction. For our argument, we use the term “addiction” as originally used by Leshner [ 1 ]; in Box 1 , we map out and discuss how this construct may relate to the current diagnostic categories, such as Substance Use Disorder (SUD) and its different levels of severity (Fig. 1) .

Risky (hazardous) substance use refers to quantity/frequency indicators of consumption; SUD refers to individuals who meet criteria for a DSM-5 diagnosis (mild, moderate, or severe); and addiction refers to individuals who exhibit persistent difficulties with self-regulation of drug consumption. Among high-risk individuals, a subgroup will meet criteria for SUD and, among those who have an SUD, a further subgroup would be considered to be addicted to the drug. However, the boundary for addiction is intentionally blurred to reflect that the dividing line for defining addiction within the category of SUD remains an open empirical question.

Box 1 What’s in a name? Differentiating hazardous use, substance use disorder, and addiction

Although our principal focus is on the brain disease model of addiction, the definition of addiction itself is a source of ambiguity. Here, we provide a perspective on the major forms of terminology in the field.

Hazardous Substance Use

Hazardous (risky) substance use refers to quantitative levels of consumption that increase an individual’s risk for adverse health consequences. In practice, this pertains to alcohol use [ 110 , 111 ]. Clinically, alcohol consumption that exceeds guidelines for moderate drinking has been used to prompt brief interventions or referral for specialist care [ 112 ]. More recently, a reduction in these quantitative levels has been validated as treatment endpoints [ 113 ].

Substance Use Disorder

SUD refers to the DSM-5 diagnosis category that encompasses significant impairment or distress resulting from specific categories of psychoactive drug use. The diagnosis of SUD is operationalized as 2 or more of 11 symptoms over the past year. As a result, the diagnosis is heterogenous, with more than 1100 symptom permutations possible. The diagnosis in DSM-5 is the result of combining two diagnoses from the DSM-IV, abuse and dependence, which proved to be less valid than a single dimensional approach [ 114 ]. Critically, SUD includes three levels of severity: mild (2–3 symptoms), moderate (4–5 symptoms), and severe (6+ symptoms). The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system retains two diagnoses, harmful use (lower severity) and substance dependence (higher severity).

Addiction is a natural language concept, etymologically meaning enslavement, with the contemporary meaning traceable to the Middle and Late Roman Republic periods [ 115 ]. As a scientific construct, drug addiction can be defined as a state in which an individual exhibits an inability to self-regulate consumption of a substance, although it does not have an operational definition. Regarding clinical diagnosis, as it is typically used in scientific and clinical parlance, addiction is not synonymous with the simple presence of SUD. Nowhere in DSM-5 is it articulated that the diagnostic threshold (or any specific number/type of symptoms) should be interpreted as reflecting addiction, which inherently connotes a high degree of severity. Indeed, concerns were raised about setting the diagnostic standard too low because of the issue of potentially conflating a low-severity SUD with addiction [ 116 ]. In scientific and clinical usage, addiction typically refers to individuals at a moderate or high severity of SUD. This is consistent with the fact that moderate-to-severe SUD has the closest correspondence with the more severe diagnosis in ICD [ 117 , 118 , 119 ]. Nonetheless, akin to the undefined overlap between hazardous use and SUD, the field has not identified the exact thresholds of SUD symptoms above which addiction would be definitively present.

Integration

The ambiguous relationships among these terms contribute to misunderstandings and disagreements. Figure 1 provides a simple working model of how these terms overlap. Fundamentally, we consider that these terms represent successive dimensions of severity, clinical “nesting dolls”. Not all individuals consuming substances at hazardous levels have an SUD, but a subgroup do. Not all individuals with a SUD are addicted to the drug in question, but a subgroup are. At the severe end of the spectrum, these domains converge (heavy consumption, numerous symptoms, the unambiguous presence of addiction), but at low severity, the overlap is more modest. The exact mapping of addiction onto SUD is an open empirical question, warranting systematic study among scientists, clinicians, and patients with lived experience. No less important will be future research situating our definition of SUD using more objective indicators (e.g., [ 55 , 120 ]), brain-based and otherwise, and more precisely in relation to clinical needs [ 121 ]. Finally, such work should ultimately be codified in both the DSM and ICD systems to demarcate clearly where the attribution of addiction belongs within the clinical nosology, and to foster greater clarity and specificity in scientific discourse.

What is a disease?

In his classic 1960 book “The Disease Concept of Alcoholism”, Jellinek noted that in the alcohol field, the debate over the disease concept was plagued by too many definitions of “alcoholism” and too few definitions of “disease” [ 10 ]. He suggested that the addiction field needed to follow the rest of medicine in moving away from viewing disease as an “entity”, i.e., something that has “its own independent existence, apart from other things” [ 11 ]. To modern medicine, he pointed out, a disease is simply a label that is agreed upon to describe a cluster of substantial, deteriorating changes in the structure or function of the human body, and the accompanying deterioration in biopsychosocial functioning. Thus, he concluded that alcoholism can simply be defined as changes in structure or function of the body due to drinking that cause disability or death. A disease label is useful to identify groups of people with commonly co-occurring constellations of problems—syndromes—that significantly impair function, and that lead to clinically significant distress, harm, or both. This convention allows a systematic study of the condition, and of whether group members benefit from a specific intervention.

It is not trivial to delineate the exact category of harmful substance use for which a label such as addiction is warranted (See Box 1 ). Challenges to diagnostic categorization are not unique to addiction, however. Throughout clinical medicine, diagnostic cut-offs are set by consensus, commonly based on an evolving understanding of thresholds above which people tend to benefit from available interventions. Because assessing benefits in large patient groups over time is difficult, diagnostic thresholds are always subject to debate and adjustments. It can be debated whether diagnostic thresholds “merely” capture the extreme of a single underlying population, or actually identify a subpopulation that is at some level distinct. Resolving this issue remains challenging in addiction, but once again, this is not different from other areas of medicine [see e.g., [ 12 ] for type 2 diabetes]. Longitudinal studies that track patient trajectories over time may have a better ability to identify subpopulations than cross-sectional assessments [ 13 ].

By this pragmatic, clinical understanding of the disease concept, it is difficult to argue that “addiction” is unjustified as a disease label. Among people who use drugs or alcohol, some progress to using with a quantity and frequency that results in impaired function and often death, making substance use a major cause of global disease burden [ 14 ]. In these people, use occurs with a pattern that in milder forms may be challenging to capture by current diagnostic criteria (See Box 1 ), but is readily recognized by patients, their families and treatment providers when it reaches a severity that is clinically significant [see [ 15 ] for a classical discussion]. In some cases, such as opioid addiction, those who receive the diagnosis stand to obtain some of the greatest benefits from medical treatments in all of clinical medicine [ 16 , 17 ]. Although effect sizes of available treatments are more modest in nicotine [ 18 ] and alcohol addiction [ 19 ], the evidence supporting their efficacy is also indisputable. A view of addiction as a disease is justified, because it is beneficial: a failure to diagnose addiction drastically increases the risk of a failure to treat it [ 20 ].

Of course, establishing a diagnosis is not a requirement for interventions to be meaningful. People with hazardous or harmful substance use who have not (yet) developed addiction should also be identified, and interventions should be initiated to address their substance-related risks. This is particularly relevant for alcohol, where even in the absence of addiction, use is frequently associated with risks or harm to self, e.g., through cardiovascular disease, liver disease or cancer, and to others, e.g., through accidents or violence [ 21 ]. Interventions to reduce hazardous or harmful substance use in people who have not developed addiction are in fact particularly appealing. In these individuals, limited interventions are able to achieve robust and meaningful benefits [ 22 ], presumably because patterns of misuse have not yet become entrenched.

Thus, as originally pointed out by McLellan and colleagues, most of the criticisms of addiction as a disease could equally be applied to other medical conditions [ 2 ]. This type of criticism could also be applied to other psychiatric disorders, and that has indeed been the case historically [ 23 , 24 ]. Today, there is broad consensus that those criticisms were misguided. Few, if any healthcare professionals continue to maintain that schizophrenia, rather than being a disease, is a normal response to societal conditions. Why, then, do people continue to question if addiction is a disease, but not whether schizophrenia, major depressive disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder are diseases? This is particularly troubling given the decades of data showing high co-morbidity of addiction with these conditions [ 25 , 26 ]. We argue that it comes down to stigma. Dysregulated substance use continues to be perceived as a self-inflicted condition characterized by a lack of willpower, thus falling outside the scope of medicine and into that of morality [ 3 ].

Chronic and relapsing, developmentally-limited, or spontaneously remitting?

Much of the critique targeted at the conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease focuses on its original assertion that addiction is a chronic and relapsing condition. Epidemiological data are cited in support of the notion that large proportions of individuals achieve remission [ 27 ], frequently without any formal treatment [ 28 , 29 ] and in some cases resuming low risk substance use [ 30 ]. For instance, based on data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) study [ 27 ], it has been pointed out that a significant proportion of people with an addictive disorder quit each year, and that most afflicted individuals ultimately remit. These spontaneous remission rates are argued to invalidate the concept of a chronic, relapsing disease [ 4 ].

Interpreting these and similar data is complicated by several methodological and conceptual issues. First, people may appear to remit spontaneously because they actually do, but also because of limited test–retest reliability of the diagnosis [ 31 ]. For instance, using a validated diagnostic interview and trained interviewers, the Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism examined the likelihood that an individual diagnosed with a lifetime history of substance dependence would retain this classification after 5 years. This is obviously a diagnosis that, once met, by definition cannot truly remit. Lifetime alcohol dependence was indeed stable in individuals recruited from addiction treatment units, ~90% for women, and 95% for men. In contrast, in a community-based sample similar to that used in the NESARC [ 27 ], stability was only ~30% and 65% for women and men, respectively. The most important characteristic that determined diagnostic stability was severity. Diagnosis was stable in severe, treatment-seeking cases, but not in general population cases of alcohol dependence.

These data suggest that commonly used diagnostic criteria alone are simply over-inclusive for a reliable, clinically meaningful diagnosis of addiction. They do identify a core group of treatment seeking individuals with a reliable diagnosis, but, if applied to nonclinical populations, also flag as “cases” a considerable halo of individuals for whom the diagnostic categorization is unreliable. Any meaningful discussion of remission rates needs to take this into account, and specify which of these two populations that is being discussed. Unfortunately, the DSM-5 has not made this task easier. With only 2 out of 11 symptoms being sufficient for a diagnosis of SUD, it captures under a single diagnostic label individuals in a “mild” category, whose diagnosis is likely to have very low test–retest reliability, and who are unlikely to exhibit a chronic relapsing course, together with people at the severe end of the spectrum, whose diagnosis is reliable, many of whom do show a chronic relapsing course.

The NESARC data nevertheless show that close to 10% of people in the general population who are diagnosed with alcohol addiction (here equated with DSM-IV “dependence” used in the NESARC study) never remitted throughout their participation in the survey. The base life-time prevalence of alcohol dependence in NESARC was 12.5% [ 32 ]. Thus, the data cited against the concept of addiction as a chronic relapsing disease in fact indicate that over 1% of the US population develops an alcohol-related condition that is associated with high morbidity and mortality, and whose chronic and/or relapsing nature cannot be disputed, since it does not remit.

Secondly, the analysis of NESARC data [ 4 , 27 ] omits opioid addiction, which, together with alcohol and tobacco, is the largest addiction-related public health problem in the US [ 33 ]. This is probably the addictive condition where an analysis of cumulative evidence most strikingly supports the notion of a chronic disorder with frequent relapses in a large proportion of people affected [ 34 ]. Of course, a large number of people with opioid addiction are unable to express the chronic, relapsing course of their disease, because over the long term, their mortality rate is about 15 times greater than that of the general population [ 35 ]. However, even among those who remain alive, the prevalence of stable abstinence from opioid use after 10–30 years of observation is <30%. Remission may not always require abstinence, for instance in the case of alcohol addiction, but is a reasonable proxy for remission with opioids, where return to controlled use is rare. Embedded in these data is a message of literally vital importance: when opioid addiction is diagnosed and treated as a chronic relapsing disease, outcomes are markedly improved, and retention in treatment is associated with a greater likelihood of abstinence.

The fact that significant numbers of individuals exhibit a chronic relapsing course does not negate that even larger numbers of individuals with SUD according to current diagnostic criteria do not. For instance, in many countries, the highest prevalence of substance use problems is found among young adults, aged 18–25 [ 36 ], and a majority of these ‘age out’ of excessive substance use [ 37 ]. It is also well documented that many individuals with SUD achieve longstanding remission, in many cases without any formal treatment (see e.g., [ 27 , 30 , 38 ]).

Collectively, the data show that the course of SUD, as defined by current diagnostic criteria, is highly heterogeneous. Accordingly, we do not maintain that a chronic relapsing course is a defining feature of SUD. When present in a patient, however, such as course is of clinical significance, because it identifies a need for long-term disease management [ 2 ], rather than expectations of a recovery that may not be within the individual’s reach [ 39 ]. From a conceptual standpoint, however, a chronic relapsing course is neither necessary nor implied in a view that addiction is a brain disease. This view also does not mean that it is irreversible and hopeless. Human neuroscience documents restoration of functioning after abstinence [ 40 , 41 ] and reveals predictors of clinical success [ 42 ]. If anything, this evidence suggests a need to increase efforts devoted to neuroscientific research on addiction recovery [ 40 , 43 ].

Lessons from genetics

For alcohol addiction, meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies has estimated heritability at ~50%, while estimates for opioid addiction are even higher [ 44 , 45 ]. Genetic risk factors are to a large extent shared across substances [ 46 ]. It has been argued that a genetic contribution cannot support a disease view of a behavior, because most behavioral traits, including religious and political inclinations, have a genetic contribution [ 4 ]. This statement, while correct in pointing out broad heritability of behavioral traits, misses a fundamental point. Genetic architecture is much like organ structure. The fact that normal anatomy shapes healthy organ function does not negate that an altered structure can contribute to pathophysiology of disease. The structure of the genetic landscape is no different. Critics further state that a “genetic predisposition is not a recipe for compulsion”, but no neuroscientist or geneticist would claim that genetic risk is “a recipe for compulsion”. Genetic risk is probabilistic, not deterministic. However, as we will see below, in the case of addiction, it contributes to large, consistent probability shifts towards maladaptive behavior.

In dismissing the relevance of genetic risk for addiction, Hall writes that “a large number of alleles are involved in the genetic susceptibility to addiction and individually these alleles might very weakly predict a risk of addiction”. He goes on to conclude that “generally, genetic prediction of the risk of disease (even with whole-genome sequencing data) is unlikely to be informative for most people who have a so-called average risk of developing an addiction disorder” [ 7 ]. This reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of polygenic risk. It is true that a large number of risk alleles are involved, and that the explanatory power of currently available polygenic risk scores for addictive disorders lags behind those for e.g., schizophrenia or major depression [ 47 , 48 ]. The only implication of this, however, is that low average effect sizes of risk alleles in addiction necessitate larger study samples to construct polygenic scores that account for a large proportion of the known heritability.

However, a heritability of addiction of ~50% indicates that DNA sequence variation accounts for 50% of the risk for this condition. Once whole genome sequencing is readily available, it is likely that it will be possible to identify most of that DNA variation. For clinical purposes, those polygenic scores will of course not replace an understanding of the intricate web of biological and social factors that promote or prevent expression of addiction in an individual case; rather, they will add to it [ 49 ]. Meanwhile, however, genome-wide association studies in addiction have already provided important information. For instance, they have established that the genetic underpinnings of alcohol addiction only partially overlap with those for alcohol consumption, underscoring the genetic distinction between pathological and nonpathological drinking behaviors [ 50 ].

It thus seems that, rather than negating a rationale for a disease view of addiction, the important implication of the polygenic nature of addiction risk is a very different one. Genome-wide association studies of complex traits have largely confirmed the century old “infinitisemal model” in which Fisher reconciled Mendelian and polygenic traits [ 51 ]. A key implication of this model is that genetic susceptibility for a complex, polygenic trait is continuously distributed in the population. This may seem antithetical to a view of addiction as a distinct disease category, but the contradiction is only apparent, and one that has long been familiar to quantitative genetics. Viewing addiction susceptibility as a polygenic quantitative trait, and addiction as a disease category is entirely in line with Falconer’s theorem, according to which, in a given set of environmental conditions, a certain level of genetic susceptibility will determine a threshold above which disease will arise.

A brain disease? Then show me the brain lesion!

The notion of addiction as a brain disease is commonly criticized with the argument that a specific pathognomonic brain lesion has not been identified. Indeed, brain imaging findings in addiction (perhaps with the exception of extensive neurotoxic gray matter loss in advanced alcohol addiction) are nowhere near the level of specificity and sensitivity required of clinical diagnostic tests. However, this criticism neglects the fact that neuroimaging is not used to diagnose many neurologic and psychiatric disorders, including epilepsy, ALS, migraine, Huntington’s disease, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. Even among conditions where signs of disease can be detected using brain imaging, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, a scan is best used in conjunction with clinical acumen when making the diagnosis. Thus, the requirement that addiction be detectable with a brain scan in order to be classified as a disease does not recognize the role of neuroimaging in the clinic.

For the foreseeable future, the main objective of imaging in addiction research is not to diagnose addiction, but rather to improve our understanding of mechanisms that underlie it. The hope is that mechanistic insights will help bring forward new treatments, by identifying candidate targets for them, by pointing to treatment-responsive biomarkers, or both [ 52 ]. Developing innovative treatments is essential to address unmet treatment needs, in particular in stimulant and cannabis addiction, where no approved medications are currently available. Although the task to develop novel treatments is challenging, promising candidates await evaluation [ 53 ]. A particular opportunity for imaging-based research is related to the complex and heterogeneous nature of addictive disorders. Imaging-based biomarkers hold the promise of allowing this complexity to be deconstructed into specific functional domains, as proposed by the RDoC initiative [ 54 ] and its application to addiction [ 55 , 56 ]. This can ultimately guide the development of personalized medicine strategies to addiction treatment.

Countless imaging studies have reported differences in brain structure and function between people with addictive disorders and those without them. Meta-analyses of structural data show that alcohol addiction is associated with gray matter losses in the prefrontal cortex, dorsal striatum, insula, and posterior cingulate cortex [ 57 ], and similar results have been obtained in stimulant-addicted individuals [ 58 ]. Meta-analysis of functional imaging studies has demonstrated common alterations in dorsal striatal, and frontal circuits engaged in reward and salience processing, habit formation, and executive control, across different substances and task-paradigms [ 59 ]. Molecular imaging studies have shown that large and fast increases in dopamine are associated with the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse, but that after chronic drug use and during withdrawal, brain dopamine function is markedly decreased and that these decreases are associated with dysfunction of prefrontal regions [ 60 ]. Collectively, these findings have given rise to a widely held view of addiction as a disorder of fronto-striatal circuitry that mediates top-down regulation of behavior [ 61 ].

Critics reply that none of the brain imaging findings are sufficiently specific to distinguish between addiction and its absence, and that they are typically obtained in cross-sectional studies that can at best establish correlative rather than causal links. In this, they are largely right, and an updated version of a conceptualization of addiction as a brain disease needs to acknowledge this. Many of the structural brain findings reported are not specific for addiction, but rather shared across psychiatric disorders [ 62 ]. Also, for now, the most sophisticated tools of human brain imaging remain crude in face of complex neural circuit function. Importantly however, a vast literature from animal studies also documents functional changes in fronto-striatal circuits, as well their limbic and midbrain inputs, associated with addictive behaviors [ 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 ]. These are circuits akin to those identified by neuroimaging studies in humans, implicated in positive and negative emotions, learning processes and executive functions, altered function of which is thought to underlie addiction. These animal studies, by virtue of their cellular and molecular level resolution, and their ability to establish causality under experimental control, are therefore an important complement to human neuroimaging work.

Nevertheless, factors that seem remote from the activity of brain circuits, such as policies, substance availability and cost, as well as socioeconomic factors, also are critically important determinants of substance use. In this complex landscape, is the brain really a defensible focal point for research and treatment? The answer is “yes”. As powerfully articulated by Francis Crick [ 69 ], “You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules”. Social and interpersonal factors are critically important in addiction, but they can only exert their influences by impacting neural processes. They must be encoded as sensory data, represented together with memories of the past and predictions about the future, and combined with representations of interoceptive and other influences to provide inputs to the valuation machinery of the brain. Collectively, these inputs drive action selection and execution of behavior—say, to drink or not to drink, and then, within an episode, to stop drinking or keep drinking. Stating that the pathophysiology of addiction is largely about the brain does not ignore the role of other influences. It is just the opposite: it is attempting to understand how those important influences contribute to drug seeking and taking in the context of the brain, and vice versa.

But if the criticism is one of emphasis rather than of principle—i.e., too much brain, too little social and environmental factors – then neuroscientists need to acknowledge that they are in part guilty as charged. Brain-centric accounts of addiction have for a long time failed to pay enough attention to the inputs that social factors provide to neural processing behind drug seeking and taking [ 9 ]. This landscape is, however, rapidly changing. For instance, using animal models, scientists are finding that lack of social play early in life increases the motivation to take addictive substances in adulthood [ 70 ]. Others find that the opportunity to interact with a fellow rat is protective against addiction-like behaviors [ 71 ]. In humans, a relationship has been found between perceived social support, socioeconomic status, and the availability of dopamine D2 receptors [ 72 , 73 ], a biological marker of addiction vulnerability. Those findings in turn provided translation of data from nonhuman primates, which showed that D2 receptor availability can be altered by changes in social hierarchy, and that these changes are associated with the motivation to obtain cocaine [ 74 ].

Epidemiologically, it is well established that social determinants of health, including major racial and ethnic disparities, play a significant role in the risk for addiction [ 75 , 76 ]. Contemporary neuroscience is illuminating how those factors penetrate the brain [ 77 ] and, in some cases, reveals pathways of resilience [ 78 ] and how evidence-based prevention can interrupt those adverse consequences [ 79 , 80 ]. In other words, from our perspective, viewing addiction as a brain disease in no way negates the importance of social determinants of health or societal inequalities as critical influences. In fact, as shown by the studies correlating dopamine receptors with social experience, imaging is capable of capturing the impact of the social environment on brain function. This provides a platform for understanding how those influences become embedded in the biology of the brain, which provides a biological roadmap for prevention and intervention.

We therefore argue that a contemporary view of addiction as a brain disease does not deny the influence of social, environmental, developmental, or socioeconomic processes, but rather proposes that the brain is the underlying material substrate upon which those factors impinge and from which the responses originate. Because of this, neurobiology is a critical level of analysis for understanding addiction, although certainly not the only one. It is recognized throughout modern medicine that a host of biological and non-biological factors give rise to disease; understanding the biological pathophysiology is critical for understanding etiology and informing treatment.

Is a view of addiction as a brain disease deterministic?

A common criticism of the notion that addiction is a brain disease is that it is reductionist and in the end therefore deterministic [ 81 , 82 ]. This is a fundamental misrepresentation. As indicated above, viewing addiction as a brain disease simply states that neurobiology is an undeniable component of addiction. A reason for deterministic interpretations may be that modern neuroscience emphasizes an understanding of proximal causality within research designs (e.g., whether an observed link between biological processes is mediated by a specific mechanism). That does not in any way reflect a superordinate assumption that neuroscience will achieve global causality. On the contrary, since we realize that addiction involves interactions between biology, environment and society, ultimate (complete) prediction of behavior based on an understanding of neural processes alone is neither expected, nor a goal.

A fairer representation of a contemporary neuroscience view is that it believes insights from neurobiology allow useful probabilistic models to be developed of the inherently stochastic processes involved in behavior [see [ 83 ] for an elegant recent example]. Changes in brain function and structure in addiction exert a powerful probabilistic influence over a person’s behavior, but one that is highly multifactorial, variable, and thus stochastic. Philosophically, this is best understood as being aligned with indeterminism, a perspective that has a deep history in philosophy and psychology [ 84 ]. In modern neuroscience, it refers to the position that the dynamic complexity of the brain, given the probabilistic threshold-gated nature of its biology (e.g., action potential depolarization, ion channel gating), means that behavior cannot be definitively predicted in any individual instance [ 85 , 86 ].

Driven by compulsion, or free to choose?

A major criticism of the brain disease view of addiction, and one that is related to the issue of determinism vs indeterminism, centers around the term “compulsivity” [ 6 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 ] and the different meanings it is given. Prominent addiction theories state that addiction is characterized by a transition from controlled to “compulsive” drug seeking and taking [ 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 ], but allocate somewhat different meanings to “compulsivity”. By some accounts, compulsive substance use is habitual and insensitive to its outcomes [ 92 , 94 , 96 ]. Others refer to compulsive use as a result of increasing incentive value of drug associated cues [ 97 ], while others view it as driven by a recruitment of systems that encode negative affective states [ 95 , 98 ].

The prototype for compulsive behavior is provided by obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), where compulsion refers to repeatedly and stereotypically carrying out actions that in themselves may be meaningful, but lose their purpose and become harmful when performed in excess, such as persistent handwashing until skin injuries result. Crucially, this happens despite a conscious desire to do otherwise. Attempts to resist these compulsions result in increasing and ultimately intractable anxiety [ 99 ]. This is in important ways different from the meaning of compulsivity as commonly used in addiction theories. In the addiction field, compulsive drug use typically refers to inflexible, drug-centered behavior in which substance use is insensitive to adverse consequences [ 100 ]. Although this phenomenon is not necessarily present in every patient, it reflects important symptoms of clinical addiction, and is captured by several DSM-5 criteria for SUD [ 101 ]. Examples are needle-sharing despite knowledge of a risk to contract HIV or Hepatitis C, drinking despite a knowledge of having liver cirrhosis, but also the neglect of social and professional activities that previously were more important than substance use. While these behaviors do show similarities with the compulsions of OCD, there are also important differences. For example, “compulsive” substance use is not necessarily accompanied by a conscious desire to withhold the behavior, nor is addictive behavior consistently impervious to change.