- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

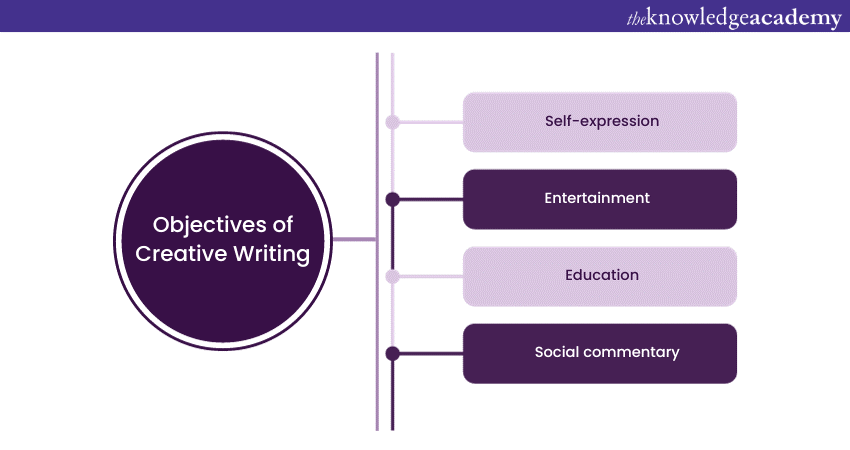

Objectives of Creative Writing

Delve into the "Objectives of Creative Writing" and explore the multifaceted aims of this expressive art form. Uncover the diverse purposes, entertainment, education, and social commentary, that creative writing serves. Gain a deeper understanding of how creative writing transcends mere words, providing insight into the human experience.

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Creative Writing Course

- Report Writing Course

- Attention Management Training

- Cake Decorating Getting Started Workshop

- Bag Making Course

In this blog, we delve into the Objectives of Creative Writing and its purposes, shedding light on its significance in our lives. From the art of storytelling to the therapeutic release of emotions, Creative Writing is a dynamic and versatile discipline that has enchanted both writers and readers for generations.

Table of C ontents

1) Objectives of Creative Writing

a) Self-expression

b) Entertainment

c) Education

d) Social commentary

2) Purpose of Creative Writing

3) Conclusion

Objectives of Creative Writing

Creative Writing serves as a versatile and dynamic form of expression, encompassing a range of objectives that go beyond mere storytelling. Here, we delve into the fundamental objectives that drive creative writers to craft their narratives and explore the depths of human creativity:

Self-expression

Creative Writing is, at its core, a powerful means of self-expression. It provides writers with a unique canvas upon which they can paint the colours of their innermost thoughts, emotions, and experiences. This objective of Creative Writing is deeply personal and cathartic, as it allows individuals to articulate their inner worlds in ways that spoken language often cannot.

Through the act of writing, authors can explore the complexities of their own psyche, giving shape and substance to feelings that might otherwise remain elusive. Whether it's capturing the euphoria of love, the depths of sorrow, or the intricacies of human relationships, Creative Writing serves as a conduit for unfiltered self-expression.

Moreover, Creative Writing grants the freedom to experiment with different writing styles, tones, and literary devices, enabling writers to find their unique voices. In the process, it cultivates self-awareness, self-discovery, and a deeper understanding of one's own experiences. For many, the act of putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard is a therapeutic release, a way to make sense of the chaos within, and an avenue for personal growth and reflection. In essence, Creative Writing empowers individuals to share their inner narratives with the world, fostering connection and empathy among fellow readers who may find solace, resonance, or inspiration in the tales of others.

Entertainment

One of the primary and most recognisable objectives of Creative Writing is to entertain. Creative writers craft stories, poems, and essays that are designed to captivate readers, transporting them to different worlds, evoking emotions, and engaging their imaginations.

At its heart, Creative Writing is the art of storytelling, and storytelling has been an integral part of human culture since time immemorial. Whether it's a thrilling mystery, a heartwarming romance, or a thought-provoking science fiction narrative, Creative Writing offers an escape from the ordinary into realms of fantasy, intrigue, and wonder. It weaves narratives with vivid imagery, compelling characters, and gripping plots, all working together to hold the reader's attention.

Through Creative Writing, authors create emotional connections between the reader and the characters, fostering a sense of empathy and identification. As readers immerse themselves in a well-crafted story, they experience a wide range of emotions, from laughter to tears, joy to sorrow. It is this emotional journey that makes Creative Writing such a potent form of entertainment, offering readers a pleasurable escape from reality, a chance to explore new perspectives and a memorable experience that lingers long after the last page is turned.

Education

Creative Writing is not only a source of entertainment but also a powerful educational tool. It engages writers in a process that goes beyond storytelling; it encourages research, critical thinking, and the development of effective communication skills.

Writers often embark on extensive research journeys to create authentic settings, characters, and plots. This quest for accuracy and depth enriches their knowledge in various fields, ranging from history and science to culture and psychology. As they delve into their chosen topics, writers gain valuable insights and expand their intellectual horizons.

Furthermore, Creative Writing teaches readers important life lessons and imparts knowledge. It introduces them to diverse perspectives, cultures, and experiences, fostering empathy and understanding. Reading well-crafted works can be an enlightening experience, challenging preconceptions and encouraging critical thinking. It also enhances vocabulary, language skills, and the ability to express thoughts and emotions effectively.

In educational settings, Creative Writing nurtures creativity, encourages self-expression, and helps students develop essential communication and analytical skills. This educational objective of Creative Writing underscores its value as a holistic tool for personal and intellectual growth, making it an integral part of both formal and informal learning processes.

Social commentary

Creative Writing often serves as a potent medium for social commentary, embodying a powerful objective that transcends mere storytelling. Through the art of narrative, poets, novelists, and essayists alike can engage in meaningful discourse about society's values, issues, and challenges.

Writers use their creative works to shine a light on important societal concerns, question norms, and provoke thought. They employ allegory, satire, symbolism, and other literary techniques to critique, challenge, or explore various aspects of the human condition and the world we inhabit. Whether addressing issues such as inequality, injustice, environmental crises, or political corruption, Creative Writing can be a catalyst for change.

By portraying the complexities of real-life situations and characters, writers encourage readers to reflect on their own lives and the world around them. This introspection can lead to increased awareness and, ideally, inspire action to address pressing societal issues.

In essence, the social commentary objective of Creative Writing underscores its role as a mirror reflecting the world's triumphs and flaws. It empowers writers to be advocates for change, storytellers with a purpose, and champions of social justice, ensuring that Creative Writing continues to be a powerful force for positive transformation in society.

Tap into your creative potential with our Creative Writing Training – Get started today!

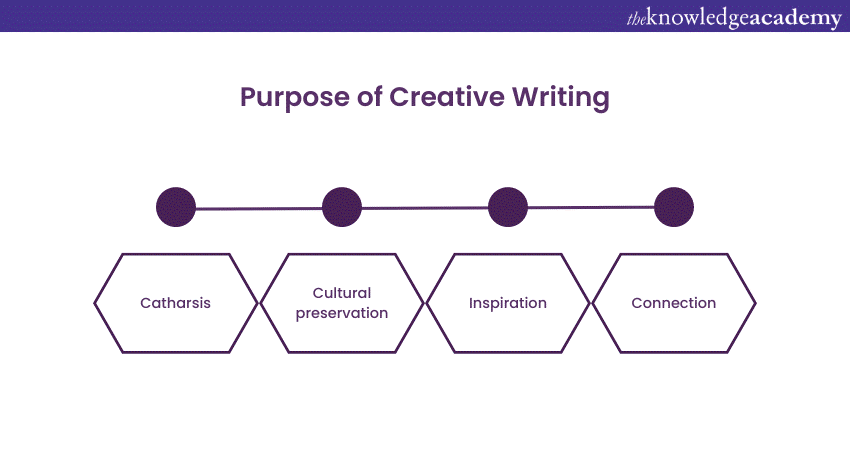

Purpose of Creative Writing

Creative Writing serves a multitude of purposes, making it a dynamic and invaluable art form. Beyond its objectives, Creative Writing plays a crucial role in our lives and society, contributing to personal growth, cultural preservation, inspiration, and connection.

Catharsis

One of the profound and therapeutic purposes of Creative Writing is catharsis. This aspect of Creative Writing is deeply personal, as it offers writers a means to release pent-up emotions, confront inner turmoil, and find a sense of closure.

Through the act of writing, individuals can explore their innermost thoughts and feelings in a safe and controlled environment. Whether it's grappling with grief, heartbreak, trauma, or any other emotional burden, Creative Writing provides an outlet to give shape and voice to those complex emotions. It allows writers to dissect their experiences, providing a space for self-reflection and healing.

The process of transforming raw emotions into words can be both liberating and transformative. It can provide a sense of relief, allowing writers to gain insight into their emotional landscapes. Moreover, sharing these emotions through writing can foster connection and empathy among readers who may have experienced similar feelings or situations, creating a sense of community and understanding.

Ultimately, catharsis through Creative Writing is a journey of self-discovery and emotional release, offering solace, healing, and a path towards personal growth and resilience. It highlights the profound impact of the written word in helping individuals navigate the complexities of their own inner worlds.

Cultural preservation

Creative Writing serves a noble purpose beyond personal expression and entertainment—it plays a vital role in cultural preservation. This objective of Creative Writing involves safeguarding the rich tapestry of human heritage, traditions, and stories for future generations.

Cultures are defined by their narratives, folklore, and historical accounts. Creative writers, whether chroniclers of oral traditions or authors of historical fiction are the custodians of these invaluable cultural treasures. They document the stories passed down through generations, ensuring they are not lost to time.

Through Creative Writing, cultures are celebrated, languages are preserved, and unique identities are immortalised. Folktales, myths, and legends are retold, keeping them relevant and alive. These narratives provide insights into the beliefs, values, and wisdom of a society, fostering a deeper understanding of its roots.

Moreover, Creative Writing bridges cultural divides by sharing stories from diverse backgrounds, fostering empathy and appreciation for the richness of human experience. In this way, Creative Writing becomes a bridge across generations, connecting the past with the present and preserving the collective memory of humanity for a brighter future.

Inspiration

One of the transformative purposes of Creative Writing is to inspire others. It is a beacon that shines brightly, guiding aspiring writers and kindling the creative flames within them. Through the power of storytelling and the written word, Creative Writing has the remarkable ability to ignite the spark of imagination and motivation.

Exceptional works of literature often leave an indelible mark on readers. They can evoke a sense of wonder, curiosity, and passion, motivating individuals to embark on their own creative journeys. Many renowned authors found their calling through the inspiration they drew from the words of others, perpetuating a beautiful cycle of creativity.

Creative Writing serves as a testament to human potential, showcasing the boundless depths of imagination and the infinite possibilities of language. It encourages individuals to explore their unique perspectives, cultivate their voices, and craft stories that resonate with the human experience.

For writers and readers alike, Creative Writing is a wellspring of inspiration, a reminder that the world of imagination is boundless and that the written word has the power to shape minds, hearts, and the course of history. Through the act of creation and the sharing of stories, Creative Writing continues to inspire generations to dream, create, and connect with the world in profound ways.

Connection

Creative Writing holds a remarkable purpose - it fosters connections. It serves as a bridge between authors and readers, offering a means of understanding, empathy, and human connection that transcends time, space, and cultural boundaries.

When readers immerse themselves in a well-crafted story, they embark on an emotional journey alongside the characters. This shared experience creates a bond between the author and the reader as both parties navigate the complexities of the human condition together. Readers can see the world through the eyes of characters from diverse backgrounds and cultures, fostering empathy and understanding.

Furthermore, Creative Writing connects individuals across generations. Literary classics, for example, allow us to connect with the thoughts and emotions of people who lived centuries ago. These timeless works offer insights into the universal aspects of the human experience, reminding us of our shared humanity.

Creative Writing also has the power to connect people in the present. Through reading and discussion, individuals can form communities, share their interpretations, and engage in meaningful dialogue. Book clubs, literary events, and online forums all provide platforms for people to connect over their love for literature.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Creative Writing is a multifaceted art form with diverse objectives and purposes. From self-expression and entertainment to education, social commentary, catharsis, cultural preservation, inspiration, and connection, it enriches our lives in myriad ways. This timeless craft continues to captivate, inspire, and connect us, shaping our world through the power of words.

Embark on your personal growth journey with our Personal Development Training – Explore now!

Frequently Asked Questions

Upcoming business skills resources batches & dates.

Fri 26th Apr 2024

Fri 24th May 2024

Fri 28th Jun 2024

Fri 26th Jul 2024

Fri 23rd Aug 2024

Fri 27th Sep 2024

Fri 25th Oct 2024

Fri 22nd Nov 2024

Fri 27th Dec 2024

Get A Quote

WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

My employer

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry

- Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this course

Our biggest spring sale.

We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry.

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry.

We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements.

Or select from our popular topics

- ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Business Analysis Courses

- Microsoft Azure Certification

- Microsoft Excel & Certification Course

- Microsoft Project

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close

Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch.

Fill out your contact details below

Thank you for your enquiry!

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements.

Back to Course Information

Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements.

* WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

Preferred Contact Method

No preference

Back to course information

Fill out your training details below

Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are.

HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING?

HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED?

Online Instructor-led

Online Self-paced

WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE?

Next 2 - 4 months

WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING?

Looking for some information

Looking for a discount

I want to book but have questions

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements.

Your privacy & cookies!

Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy .

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.

clock This article was published more than 6 years ago

Why you are wrong if you think creative writing is a ‘frivolous waste of time’

If you think creative writing is a “frivolous waste of time,” you are just plain wrong.

So writes English teacher Justin Parmenter, who laments that writing has become “ little more than an afterthought” in this era when standardized testing reigns supreme, with serious consequences for students.

Parmenter, an educator for more than 20 years, teaches seventh-grade language arts at Waddell Language Academy in Charlotte and is a fellow with Hope Street Group’s North Carolina Teacher Voice Network, which provides feedback to education policymakers.

His first teaching job was at a school on the White Mountain Apache Reservation in the poorest county in Arizona, where young people face extraordinary challenges. He started his career as a Peace Corps volunteer in Albania and taught in Istanbul. He was a finalist for Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools Teacher of the Year in 2016, and you can find him on Twitter here: @JustinParmenter

This first appeared in Teachers & Writers Magazine , which gave me permission to publish it here.

The real reasons so many young people can’t write well today — by an English teacher

By Justin Parmenter

Ask any English teacher what he or she could use more of, and chances are you’ll get the same answer. Classroom resources are great, more money would be nice, but what we really need is more time.

Just like in any other discipline, English teachers have way more curriculum than we can cover in a year. Time constraints force educators to prioritize by order of what feels most important, and all too often that importance is determined by what’s going to be on the test.

Our students pay the price as activities that cultivate essential real-world skills such as collaboration and creativity and provide them with a much more engaging and well-rounded education are eliminated from their classes.

Educators are under enormous pressures stemming from a data-driven culture most recently rooted in No Child Left Behind and its successor, the Every Student Succeeds Act, in which the ultimate measure of professional and academic success is a standardized test score.

As a result of this standardized testing culture, many of our English students spend way too much time reading random passages which are completely detached from their lives and answering multiple choice questions in an attempt to improve test results. In many classrooms, writing has become little more than an afterthought .

Creative writing, in particular, is seen by some as a frivolous waste of time because its value is so difficult to justify with data.

Teacher: What happened when I stopped viewing my students as data points

Two decades before the advent of No Child Left Behind, the research of influential literacy professor Gail Tompkins identified seven compelling reasons why children should spend time writing creatively in class:

- to entertain

- to foster artistic expression

- to explore the functions and values of writing

- to stimulate imagination

- to clarify thinking

- to search for identity

- to learn to read and write

The majority of Tompkins’s outcomes of creative writing could never be measured on today’s standardized tests. Indeed, over the same period that standardized reading tests have pushed writing in English classes to the sidelines, efforts to evaluate student writing on a broad, systematic scale have dwindled. Measuring student writing is expensive, and accurately assessing abstract thinking requires human resources most states aren’t willing to pony up. It’s much cheaper to score a bubble sheet.

Measurement and assessment aside, the soft skills that we cultivate through regular creative writing with our students have tremendous real-world application as well as helping to promote the kind of atmosphere we want in our classrooms. After many years as an English teacher, I’ve found that carving out regular time for creative writing in class provides benefits for me and my students that we simply don’t get from other activities.

One of the benefits of creative writing in the classroom is how engaging it is for our students. In general, much of our curriculum follows a one-size-fits-all design and allows little room for freedom of exploration. For young people who are at a time in life when many of their decisions are made for them, this lack of power can be very demotivating and can negatively impact their interest and effort. To do their best work, students need to feel that school is about them, and they need to feel connected to the content on a personal level. When students are given opportunities to experiment with their voices and create through their own original work, they feel a sense of place and they are able to feel in charge. That’s when they shine.

A former student and talented writer told me the following about her relationship with creative writing in the classroom:

Creative writing is important to me because it gives me a way to express myself. There are not a lot of ways, as a young teenager, to be able to freely express ideas and emotions. Many are personal feelings you wouldn’t really want to share with others. But in writing you can put all of those mixed emotions into words. Next thing you know, you’ve created an entirely different universe, with characters close to your heart. Everything is under your complete control. That is not something that you can experience in reality, even reading a book. The feeling that you have created something, something that you can call your own, is what makes it incredible.

When we empower our students to create something that is only theirs, to make big choices in their writing, it can transform attitudes toward learning and school in general. Having students who are motivated to work to their full potential is a dream scenario for any teacher. Regular creative writing can help us to move in that direction.

Another very real benefit of creative writing in the classroom is that it can help to develop a sense of community among our students. In our bitterly polarized society, any activity that fosters empathy and collaboration is well worth our time.

Students can share writing with each other at the drafting phase, working together to hone their individual stories. This teamwork allows our students to support each other and work to understand each other’s perspectives. In addition to peer editing, having students co-author creative pieces, whether as an informal “chain story” type activity or a longer, more polished product, can go a long way in nurturing the skills required for effective partnership. Sharing responsibility in the creative process serves as a powerful motivator for our students, often leading to better quality writing.

It’s unlikely that our English teachers are going to get the additional time they so desperately need. What we’re left with is the task of prioritizing class content in such a way that we’re truly meeting all the needs of our students.

Data is an important tool in helping us to measure how well we’re meeting those needs, but our definition of data must be broad enough to include outcomes that can’t be captured with a standardized test. We must trust our English teachers to plan instruction that is in the best interests of their students and to know when they’ve succeeded.

As a regular part of that instruction, creative writing can empower our students and give them ownership so critical to their motivation. It can provide them essential practice at partnering with their peers in a world where more effective collaboration is sorely needed.

At its most powerful, creative writing can help turn our English courses into the life-changing experience that all educators want their classes to be.

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

University Writing Center

University writing center blog, writing as catharsis.

Written by: Zoe H.

One of our amazing consultants Zoe H. discusses how writing is not only for academia, but also a personal experience for the every-day writer.

I didn’t know I wanted to be a writer until late in my senior year of high school. I took a lot of personality tests until trying to figure it out, not that they helped. (I really don’t want to be a teacher, no matter how many times Buzzfeed tells me to be one.) However, I started writing creatively in middle school. Some people cope with exercise; others baking; the productive ones , cleaning. I cope(d) with poetry.

Now , this poetry won’t win awards. It ignores many basic guidelines of poetry (there was absolutely no imagery in for many years, plus some horrendous end rhyme). But I found a way to shamelessly express my emotions. I proudly claim being introspective (the many hours of considering my qualities, place in the world, and the like can attest to that), but I have always struggled with emotions. I know that I am feeling them but fail to parse the distinct emotions and their causes; writing poetry provides a sense of clarity. I can write as messily and horribly as I want and figure myself out along the way. I assume the process is similar to journaling, but this is natural to me. I sometimes think in- admittedly bad- poetry (a strange attribute for a child of scientists). Poetry is inherent in how I perceive and interact with the world.

This writing is different from my writing for assignments or submissions for publication (we will call it professional poetry, though no one pays me). For cathartic writing, I keep no audience in mind and not care about how the words sound. Sometimes these poems work themselves into more marketable pieces when the emotion has faded and I reworked the form and language. Other times, I approach my professional poetry starting with the form or the rhyme scheme or a cool metaphor and add emotion after the mechanics are straightened out.

I have been taught that the purpose of writing is to share information with others. I discovered it can also be to share information with myself. However, it is also okay if you don’t learn anything. It is valid to write just to write, knowing that nothing is expected. It can be a form of self-care or a way of self-expression or simply an exercise to see how many rhyming words you can fit into a sentence about pancakes. Writing is often accompanied with expectations and anxiety, but there is so much more it can provide. For me, it’s catharsis and learning. Enjoy discovering what it does for you.

Featured Story

Writing center blog.

- Three Commonalities of any Writing Center Session – Part 2

- Three Commonalities of any Writing Center Session – Part 1

- Delayed Writers: What Students Can Do to Get Back into Writing

- 10 Reasons Why You Should Schedule an Appointment at the UWC

- Scheduling a UWC Appointment with Ease

- Announcements

- Conferences

- Consultant Spotlight

- Creative Writing

- Difficult Conversations

- Graduate Writing

- Intersectionality

- multimodal composing

- Neurodiversity

- Opportunity

- Retrospectives

- Uncategorized

- women's history month

- Writing Center Work

- Writing Strategies

- November 2023

- November 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- September 2021

Creating Catharsis: How to Write a Story That Works

by Lewis / June 8, 2021 / Other , Story Structure

When writing a novel, your plot will take center stage.

Not only is your plot a major component of your novel, but it’s also the foundation from which you’ll build everything from your characters, to your worldbuilding, theme, and more. This means that writing a compelling plot is a critical step if you want your novel to succeed—and no plot is truly complete without a healthy dose of catharsis.

So, in this article, let’s unpack what exactly catharsis is, as well as the three key elements you’ll need to write a cathartic plot. Finally, to wrap things up, I’ll walk you through how story structure can help you create catharsis in your own novels!

What is Catharsis?

- 1 What is Catharsis?

- 2.1 Peripeteia – Change:

- 2.2 Hamartia – Failure:

- 2.3 Kairos – Timing:

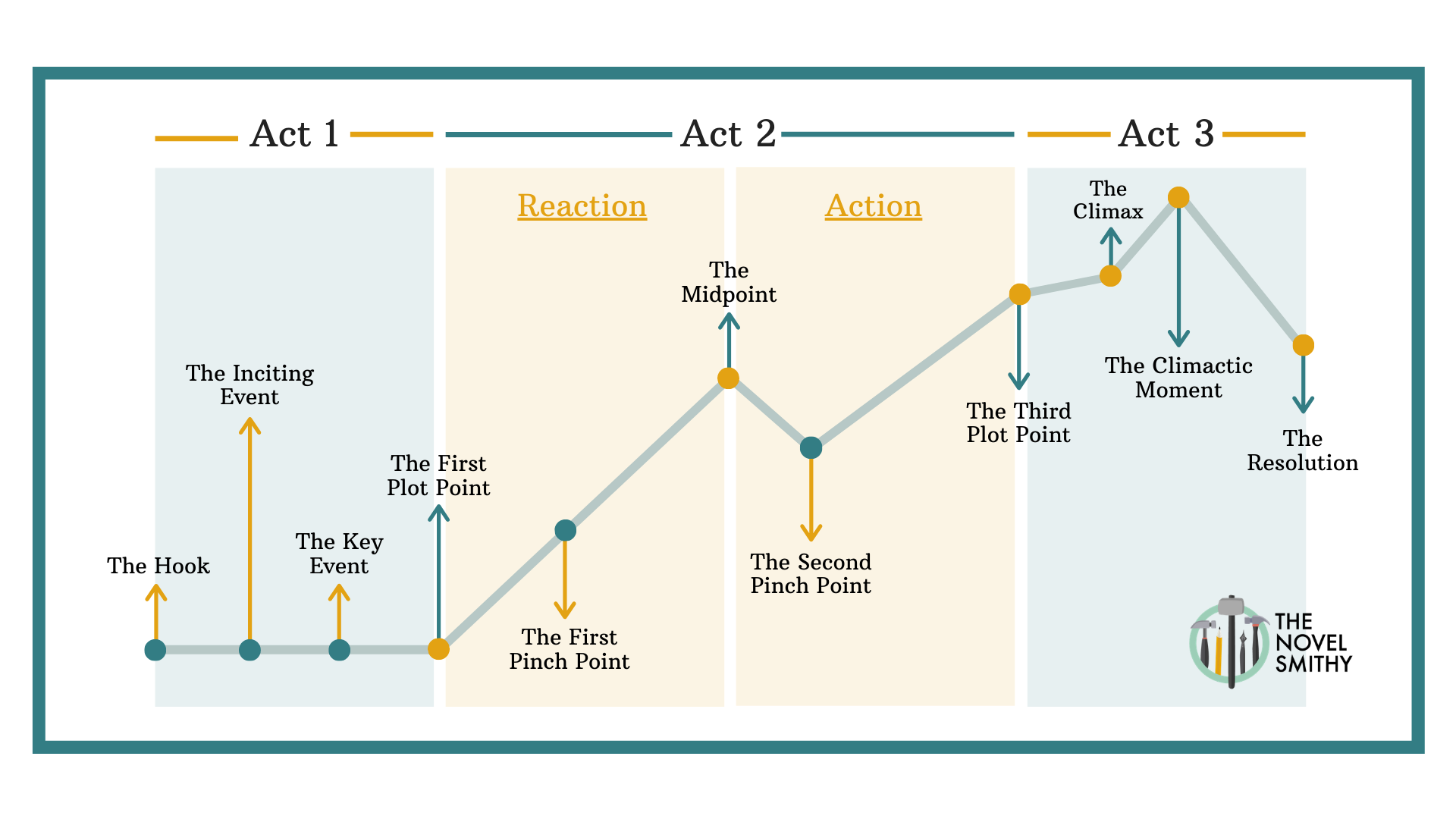

- 3.1 The Three Act Structure:

- 3.2 The Hero’s Journey:

- 4 How to Write a Cathartic Novel

Catharsis: A Greek term originally coined by Aristotle that describes the emotional release you feel at the end of a good story.

Basically, after spending so long invested in a story it’s satisfying to see that adventure conclude, even if it’s a little bittersweet at the same time.

In fact, catharsis is a big reason why some novels just “work,” even if the underlying setup doesn’t seem that interesting at first. Those novels feel good to read because they create a sense of emotional tension that’s then released at the end of the story.

Now, with that said, what does this all mean? Well, basically, it means that catharsis is a key element of a successful plot. Without a sense of catharsis, your plot will fall flat, and readers will likely walk away feeling unsatisfied.

Of course, actually creating this catharsis is easier said than done.

While catharsis is critical to writing a plot readers enjoy, it isn’t something you can casually create in the final scenes of your novel. Instead, catharsis requires you to lay the groundwork from the very beginning of your story, ensuring readers are invested in your protagonist’s journey and are always anticipating what might come next. This way, when you reach your finale, you can create the rush of emotions that are a hallmark of a truly cathartic novel.

Fortunately, there are actually a set of three principles (also courtesy of Aristotle) that you can use to reliably create catharsis. So, let’s look at these three elements a bit more closely, before diving into how to apply them to your stories!

The Three Keys to a Cathartic Story

Peripeteia – change:.

First up, we have peripeteia, a Greek word meaning “a reversal of fortune” or a “change in circumstances.”

At its core, this term describes the key turning points that should occur in your story. These could be anything, from your hero entering a strange new world, to suddenly losing their livelihood in a financial crisis, to convincing their lover to marry them. Whether positive or negative, this sudden change creates a sense of suspense and investment in your story by introducing an element of unknown.

In fact, your plot will likely feature multiple instances of peripeteia.

A peripeteia often sparks your protagonist’s adventure in the first place, while peripeteias towards the end of your story could throw a wrench in their plans or raise the stakes approaching your finale. It’s these reversals of fortune that will play a big role in keeping your readers on the edge as they approach the end of your novel.

All of this means that peripeteia should mark a major change in your protagonist’s journey—and that it should be closely linked to the major struggles that define their adventure.

For example, in Disney’s Mulan, Mulan experiences two moments of peripeteia: the moment she disguises herself as a man and becomes a soldier, and the moment her true identity is revealed and her disguise is stripped from her. In both instances, her circumstances change dramatically, and these changes hinge on the main struggle she faces throughout her story—that being society’s refusal to respect her as equal because of her gender.

“The first essential, the life and soul, so to speak, of a story, is the Plot.” – Aristotle

Hamartia – Failure:

Next we have hamartia , or moments in your story where your hero experiences failure.

You see, throughout your plot your protagonist should pursue some kind of goal , and this goal will be at the forefront of their journey. However, they won’t always make the right choices in pursuit of that goal—and this is where hamartia comes in.

Specifically, hamartia is when your hero fails due to their own poor judgement.

This is incredibly important, because your protagonist needs opportunities to struggle and learn in order to complete their character arc —otherwise, their story will feel hollow. As they pursue their goal, they’ll make the wrong choices, and will be forced to rethink their behavior when they’re punished for those failures. Next time, they’ll make a slightly better choice, until they slowly grow as a person.

As a bonus, this continues to raise the stakes of your plot in concert with peripeteia. Your reader isn’t confident your hero will always get things right, or that they won’t be thrown a curveball they can’t handle—meaning the outcome of your story isn’t certain.

You can see this at work again is Disney’s Mulan .

Mulan experiences multiple instances of hamartia, such as when she accidentally sparks a fight among the men in her clumsy attempts to appear “masculine.” These instances of hamartia occur because she’s trying to be something she’s not—she’s ignoring her cleverness and instead relying on raw strength. Fortunately, these failures slowly push her to embrace her talents, and she’ll eventually succeed as a result.

Kairos – Timing:

Finally, we have kairos, which roughly means “the opportune time.”

You see, peripeteia and hamartia need to happen at the right moments in your story to have the maximum effect. Of course, these moments should feel like logical progressions of your plot, but they do need to happen. By placing them at the right moments, you create a steady emotional rollercoaster that grips readers from beginning to end , and that evokes a strong sense of catharsis when it’s finally resolved.

Most importantly, kairos also prevents you from going too far in either direction.

If your protagonist is failing and suffering too much, it’s easy to get burnt out. Readers will feel like your hero has no hope, and they’ll write it off as a loss. In contrast, if they aren’t facing enough challenges, then there’s no reason to get invested in your plot to begin with. Everything is just an easy win, so there are no stakes to make your novel meaningful.

This is where kairos comes in, as it helps you strike a balance between failure and success. For each failure or painful experience your protagonist goes through, they also go through a moment of learning, which allows them to handle those challenges better next time.

Of course, this isn’t a one-to-one transaction—certain periods of your story will feature success and failure in different amounts. Still, by maintaining a balance, you keep your readers’ emotional tension high without burning them out, allowing you to release all of that pent up emotion in one final, rousing finale!

“When you release the character from the jeopardy of whatever problematic situation they’re in, then the audience experiences catharsis. A sigh. Whew. That’s over!” – G.M. Barlean, mystery author

Creating Catharsis Through Story Structure

Now that you understand the key elements of a cathartic story, we can talk about actually applying those elements to your novels.

All three of these elements need to be present in your story to create a truly meaningful plot. You need change to spur your hero forward on their adventure, failure to put the outcome of their journey into question, and careful timing to create the maximum emotional payoff for your readers. So, how do you do that?

Well, the answer is with story structure!

Structures like the Three Act Structure and the Hero’s Journey are designed so that they include key moments of peripeteia and hamartia at the right moments to create a cathartic story. While there are certainly other structures that fulfill these requirements, these two are a great starting point, because they’re both flexible enough to fit a variety of types of stories.

The Three Act Structure:

First up, we have the Three Act Structure.

This structure is a great option for all kinds of stories, and is also the structure you’re most likely familiar with. Most importantly, it’s also a great structure for creating catharsis, because it features a series of key turning points that start building emotional tension from page one.

At its most basic, the Three Act Structure is built on three sections:

Act 1 (Setup): Starting things off, Act 1 begins the story in your protagonist’s normal life. Some kind of catalyst turns their world on its head, and your protagonist soon finds themselves caught up in your plot. Act 2 (Confrontation): From there, you enter Act 2, where your hero will face a series of tests and trials. These will force them to adapt and learn as they work to resolve your story’s conflict, and will be where most of your “plot” occurs. Act 3 (Resolution): Finally, you’ll reach Act 3, where your protagonist will resolve the conflict of your story once and for all. Once the dust settles, they’ll also get a chance to look back and reflect on everything they’ve experienced.

As you can see, these acts create a clear “flow” in your story.

Your protagonist starts out in their normal life, before some catalyst forces that life to change. From there, they face a series of trials—many of which they struggle with—that not only put the outcome of their story into question, but also give them time to learn. Here your reader begins to identify with their struggles, reinforcing the emotional tension of the story. Finally, this structure wraps up by bringing those conflicts to their conclusion, releasing that emotional tension in a satisfying, cathartic way!

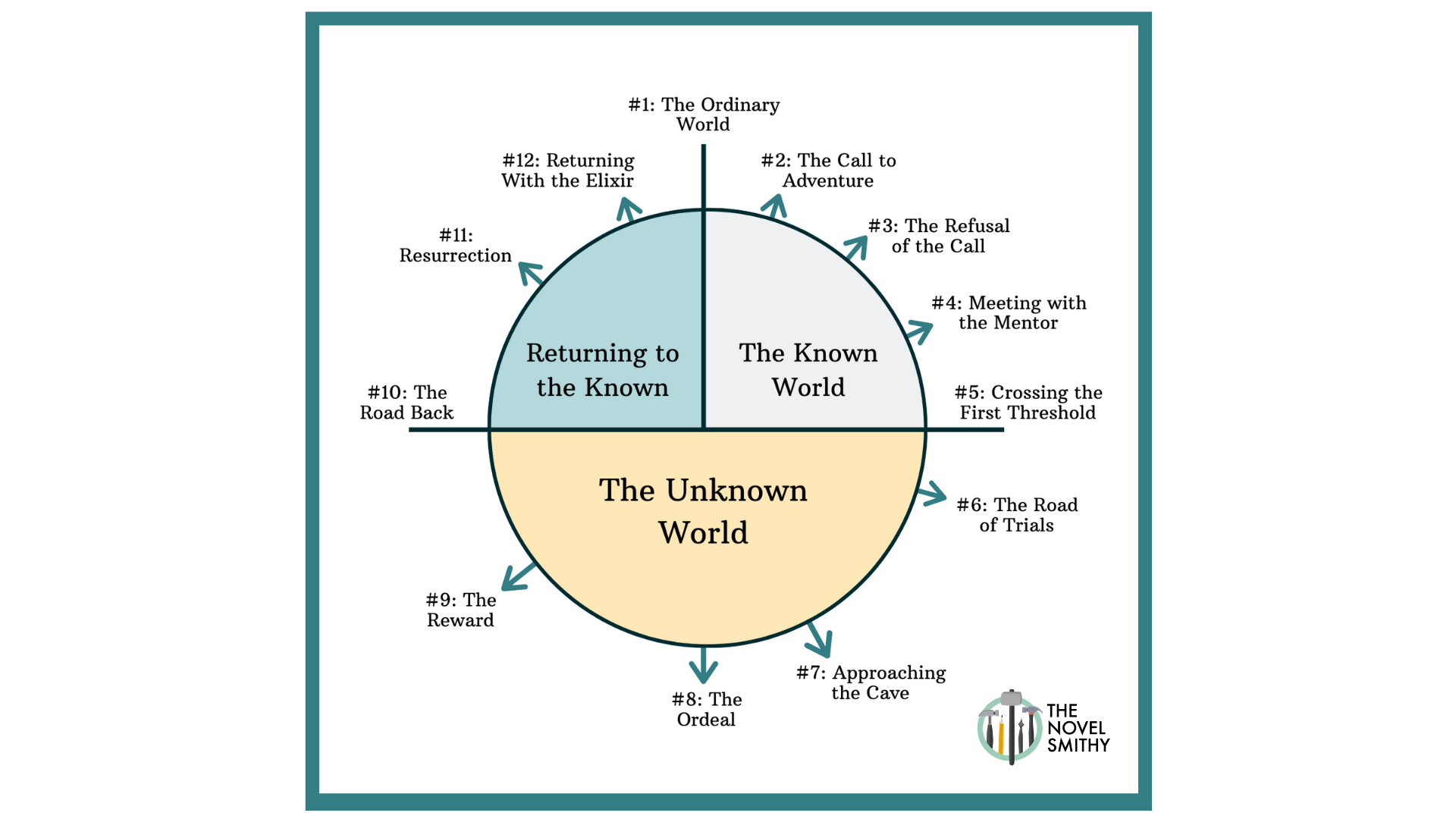

The Hero’s Journey:

Next we have the Hero’s Journey.

This structure follows a similar pattern to the Three Act Structure, with the protagonist starting in their normal world before setting out on their journey and ultimately overcoming a major conflict. However, the Hero’s Journey is distinct in that it’s a cyclical structure—to complete the Hero’s Journey, your hero must return to their community to share the rewards they’ve gained through their adventure.

This is built on three basic phases:

The Known World: First up, your hero begins in their normal world. This is where you’ll introduce who they are, as well as the wounds they and their world are suffering from. The Unknown World: Next they enter the unknown. Here they’ll undergo challenges that test their abilities, as well as grow and learn as a person. Towards the end of the unknown world, they’ll face a major ordeal and earn a reward for their victory. Returning to the Known: Finally, your hero will need to return to the known, bringing their reward with them. Here they’ll face a final conflict and hopefully heal the wounds of their community using everything they’ve learned.

As you can see, the Hero’s Journey definitely shares a lot of its DNA with the Three Act Structure, though it has a slightly different focus.

The Three Act Structure is all about the individual—the focus is on the protagonist and their personal journey, meaning any effect they have on the world around them is mostly a bonus. In contrast, the Hero’s Journey is about the world around the hero —they cannot truly complete their journey without returning to their community and healing the wounds of their world. That is what truly makes them a hero.

How to Write a Cathartic Novel

With all that said, creating a cathartic novel is really about understanding your readers’ experience first and foremost.

Why do they care about your protagonist? Why does your hero’s journey matter, both to them and the story around them? By leveraging these questions and maintaining a steady sense of emotional tension—basically, by throwing your protagonist’s success into doubt—you can create a novel that feels truly cathartic, and likely becomes a fan favorite in the process!

Here are a few final questions to consider as you set out to create catharsis:

- How will your core conflict affect your protagonist?

- What flaws or struggles will hold your protagonist back, and how will they overcome (or fail to overcome) these by the end of your story?

- Which story structure resonates with you the most?

- And how will you plan your plot to ensure you’re incorporating you need to create catharsis?

Of course, a lot of this is easier said than done. Story structure is a big topic, with lots of nuances and pitfalls to be aware of. Fortunately, I’ve got a ton of articles on this site all about making the most of your plot using story structure to guide you!

Here are a few of my favorites:

- An Introduction to the Three Act Structure

- The 9 Stages of the Hero’s Journey and How to Use Them

- Writing a Trilogy: How to Plan a Series of Novels

- The Secret to Writing a Page-Turning Novel

How will you create catharsis? Let me know in the comments!

Thoughts on creating catharsis: how to write a story that works.

Incredibly useful, as always. I am outlining at present and will go back through my plot beats to ensure I’ve captured these elements. I’m using Hero’s Journey so your blog has made this easy! I’m not sure my protag has enough ‘failures’ or hamartia to build up to a truly satisfying catharsis, but sometimes it feels as if I’m manufacturing ‘token’ trials for him to endure. Possibly there’s more opportunity for my antagonist to step in here and do some more lifting, lol!

That’s an understandable concern Vanessa. If you haven’t seen it already, perhaps this article can help: https://thenovelsmithy.com/types-of-conflict-in-novels/

There are lots of ways to create conflict (and thus failure) in your novel, so hopefully that article sparks some ideas! 🙂

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

- Get the Blog

Thursday, March 18, 2021

Cathartic writing & cathartic reading—an intersection.

1. Reading Gives You Somewhere to Go When You Have To Stay Put

2. reading allows for literal, therapeutic catharsis, 3. reading generates healing physiological changes, 4. readers are more inclined to accept beliefs alternative to their own than non-readers are, 5. the eye-movement required to read is soothing.

4 comments:

Another great post! Thank you Bonnie / Janice. Only problem . . . I can't resist opening Fiction University posts! (I do try and ignore email when I'm writing.) Sometimes I print the posts, highlight info and organize into a binder. It's beginning to be a lot to manage. I've already purchased a couple of your books. Anyway to put together a collection of blog posts?? I'd purchase it immediately! Thanks again. ;)

You're welcome, Melody! Glad you enjoyed it!

That's super great. It's true that reading fiction is like watching a different world with opened eyes 🙃

Absolutely! And these days fiction is a far site preferable to reality!

The Benefits of Creative Writing

Nanowrimo , blog.

To some, creative writing is a fun hobby that has little benefit, and can in fact serve as a time sink wherein nothing is accomplished other than words being spewed onto a page. To others, creative writing is a vital way of expressing oneself. It can be difficult to say which group is correct, but there are some definitive benefits to engaging in creative writing.

One of the first benefits is that it helps to develop creative problem solving skills. Creative writing is an exercise in solving problems, either for the characters within the story or for the author themselves. Characters within stories need to be navigated through a series of difficulties, and if the problems take place in the real world, then the solutions must also be real-world solutions. If the problem is a literal dragon that needs slaying, there’s somewhat less need for it to mimic a real-world solution, since that’s not typically a problem that we have. By navigating fictional characters through difficult times in their lives, either emotionally or financially, writers can learn how to handle those problems in the real world as well, without the stress of trying to figure it out when they’re already in the middle of the situation.

Another benefit of creative writing, particularly if the writer is involved in a formal class or writing group, is that it gives the writer experience in both taking and giving constructive criticism. The first time someone hears that there’s something wrong with their writing can be difficult, but over time, it does get easier. Trust me. I’ve had my fair share of critical remarks, and I’d like to think I’ve gotten better about responding to them. I no longer cry and throw things, so that’s a definite bonus. Taking criticism well is a vital skill, especially in the workplace, because employers often have feedback for their employees that might not necessarily be what the employee wants to hear. Giving criticism that is also constructive is another incredibly valuable skill. If someone believes they are just being torn down, they will not listen to a piece of criticism that might genuinely be designed to help. For this reason, it is important to understand that there are ways to provide tips for improvement without ripping someone’s work apart. Working in a workshop or a creative writing class will help improve these skills.

Creative writing helps to build vocabulary. Do you know how many types of swords there are? I don’t either, actually, but I know many of them. Do you know how many ways there are to say mean? Well, there’s mean, of course, but there are also words like malevolent and malicious and cruel, which all help to paint a more accurate picture of whatever it is that the writer is trying to portray. Once the writer knows these words, they aren’t likely to ever be forgotten. At the very least, the next time the writer is trying to describe someone as mean, they might remember that there are two other, more impressive sounding words that start with ‘m’ that might be used to describe said person.

Creative writing helps to improve outlining skills, which are vital for any kind of large project. Without an outline, creative writers might find themselves bogged down in details they didn’t intend to get lost in, or might lose track of vital plot threads that they’ll need to remember for later in this story. This is also true for any kind of large project, whether it be academic or professional. Presentations made without an outline in place can meander and get lost in themselves, making them difficult to understand or follow. For this reason, outlining is a good skill to pursue, and can be learned or improved upon through the use of creative writing.

One of the most subjective benefits to pursuing creative writing is the way that it can benefit the writer’s emotional well-being. I was skeptical about this one for a long time, because I love writing, but found it to be more stressful than anything else when I did indulge in writing. However, I have found that as I’ve adopted a regular writing schedule and have stuck to it, my mood has begun to improve greatly. I have had friends tell me that I’m happier now, and I do genuinely feel it. But I’m definitely willing to acknowledge that the same might not be true for other people

Creative writing is incredibly beneficial to burgeoning writers, and to students of all kinds. It requires effort, yes, but the more effort someone puts into it, the more likely they are to reap the benefits of it.

27 March, 2017 by McDaniel College Writing Center

Creative Writing: What It Is and Why It Matters

By: Author Paul Jenkins

Posted on Published: January 13, 2023 - Last updated: January 15, 2023

Categories Writing

Writing can be intimidating for many people, but creative writing doesn’t have to be. Creative writing is a form of self-expression that allows writers to create stories, characters, and unique settings. But what exactly is creative writing? And why is it important in today’s society? Let’s explore this further.

How We Define Creative Writing

Creative writing is any form where writers can express their thoughts and feelings imaginatively. This type of writing allows authors to draw on their imagination when creating stories and characters and play with language and structure. While there are no boundaries in creative writing, most pieces will contain dialogue, description, and narrative elements.

The Importance of Creative Writing

Creative writing is important because:

- It helps us express ourselves in ways we may not be able to do with other forms of communication.

- It allows us to explore our creativity and think outside the box.

- It can help us better understand our emotions by exploring them through storytelling or poetry.

- Writing creatively can also provide much-needed escapism from everyday life, allowing us to escape into a world of our creation.

- Creative writing helps us connect with others by sharing our experiences through stories or poems they can relate to. This way, we can gain insight into other people’s lives while giving them insight into ours.

Creative Writing: A Path to Mental and Emotional Wellness

Writing is more than just a way to express your thoughts on paper. It’s a powerful tool that can be used as a form of therapy. Creative writing has been shown to improve emotional and mental well-being.

Through creative writing, we can gain insight into our emotions, develop self-expression and communication skills, cultivate empathy and understanding of others, and boost our imagination and creativity.

Let’s examine how creative writing can relieve stress and emotional catharsis.

Stress Relief and Emotional Catharsis

Writing has the power to reduce stress levels significantly. Writing about our experiences or about things that are causing us anxiety or distress helps us to release those complicated feelings constructively. By expressing ourselves through creative writing, we can work through the emotions associated with stressful situations without having to confront them directly.

This is especially helpful for people who struggle to share their emotions verbally or in person.

Improved Communication and Self-Expression

Creative writing is also beneficial for improving communication skills. Through creative writing, we can explore our thoughts and feelings more intensely than by speaking them aloud. This allows us to think more clearly about what we want to say before actually saying it out loud or in written form, which leads to improved self-expression overall.

Additionally, writing out our thoughts before speaking aloud allows us to articulate ourselves better when communicating with others—which is essential for healthy personal and professional relationships.

Increased Empathy and Understanding of Others

Through creative writing, we can also increase our empathy towards others by exploring different perspectives on various topics that may be unfamiliar or uncomfortable for us—such as racism, homophobia, sexism, etc.—and allowing ourselves the opportunity to see the situation from someone else’s point of view without judgment or bias. This helps us become better communicators and more understanding individuals overall.

The Professional Benefits of Creative Writing

Creative writing is a powerful tool that can help you communicate better and more effectively in the professional world. It can also help you develop various skills that prove invaluable in many industries. Whether you’re looking to build your résumé or improve your communication, creative writing can effectively achieve both.

Let’s take a closer look at how creative writing can benefit your career.

Preparing Students for Careers in Writing, Editing, and Publishing

Creative writing is the perfect foundation for anyone interested in pursuing a career in writing, editing, or publishing. It teaches students the basics of grammar and composition while allowing them to express their ideas in imaginative ways.

Creative writing classes also allow students to learn from professionals who have experience as editors, agents, and publishers. They can use this knowledge to learn creative writing, refine their craft and gain valuable experience before entering the job market.

Improving Skills in Storytelling and Marketing for Various Careers

Creative writing teaches students to think critically about stories and craft compelling narratives that draw readers in. This skill is precious for those who wish to pursue careers outside traditional writing roles—such as marketing or advertising—where storytelling is key.

People who understand the fundamentals of creative writing will be able to create persuasive copy that resonates with readers and effectively conveys a message.

Enhancing Team Collaboration and Leadership Skills

Creative writing isn’t just about expressing yourself through words; it also provides an opportunity to practice working collaboratively with others on projects. Many creative writing classes require students to work together on group projects, which helps them develop essential teamwork skills such as communication, critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity.

As they work together on these projects, they will also gain confidence in their ability to lead teams effectively—an invaluable asset no matter what industry they pursue after graduation.

Uncovering the Power of Creative Writing

Creative writing has become an increasingly powerful force in shaping our society. Creative writing has many uses, from preserving cultural heritage to promoting social change.

Preserving Cultural Heritage with Creative Writing

Creative writing has long been used to preserve and share cultural heritage stories. This is done through fictional stories or poetry that explore a particular culture or group’s history, values, and beliefs. By weaving these stories in an engaging way, writers can bring a culture’s history and traditions to life for readers worldwide. This helps bridge cultural gaps by providing insight into what makes each culture unique.

Promoting Social Change & Activism with Creative Writing

Creative writing can also be used for activism and social change. Writers can craft stories that help promote awareness about important issues such as poverty, race relations, gender equality, climate change, and more.

With the power of words, writers can inspire readers to take action on these issues and work towards creating positive change in their communities.

Through creative writing, writers can raise awareness about important topics while fostering empathy toward individuals who may be facing difficult or challenging situations.

Fostering Creativity & Innovation with Creative Writing

Finally, creative writing can foster creativity and innovation in various fields. For example, businesses can use creative copywriting techniques to create compelling content that captures the attention of customers or potential investors.

Aspiring entrepreneurs can use storytelling techniques when pitching their ideas or products to potential partners or investors to make their cases more persuasive and memorable.

By harnessing the power of words through creative writing techniques, businesses can create content that resonates with their target audience while inspiring them to take action on whatever message they’re trying to convey. It often aids the overall creative process.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the benefits of creative writing.

Creative writing has many benefits, both for the writer and the reader. For the writer, it can be therapeutic, helping them to explore their emotions and better understand themselves. It can also be used as entertainment or communication, allowing them to share their ideas with the world. For the reader, creative writing can provide enjoyment, escapism, and insights into the human condition.

How can I improve my creative writing skills?

There are several ways you can improve your creative writing skills. Firstly, make sure you allow yourself time to write regularly. Use a writing prompt to inspire a short story. Secondly, read as much as you can; great writers are also great readers. Thirdly, experiment with different styles and genres to find one that suits you best. Fourthly, join a writers’ group, writing workshop, or creative writing program to get feedback from other writers. Finally, keep a journal to track your progress and reflect on your work as a creative writer.

What is the importance of imagery in creative writing?

Imagery is an important element of creative writing, as it helps to create a more vivid picture for the reader. By using sensory and descriptive language, writers can transport readers into their stories and help them relate to their characters or themes. Imagery can bring a scene alive with detail and evoke emotion by helping readers create strong visual images in their minds. Furthermore, imagery can help make stories more memorable by giving readers a deeper connection with the characters or setting.

What are the elements of creative writing?

The elements of creative writing include plot, character, dialogue, setting, theme, and point of view. The plot is the structure or main storyline, while the character is the personage involved in this story. Dialogue includes conversations between characters to give insight into their emotions and relationships. Setting refers to the place or time in which a story takes place, while theme explores deeper meanings behind a story’s narrative. Finally, point of view defines how readers experience a story through first-person or third-person omniscient narration.

What’s the difference between creative writing and other types of writing?

The main difference between creative writing and other types of writing is that it allows the writer to create their own story, characters, settings, and themes. Creative writing also encourages writers to be inventive with their style and use descriptive language to evoke emotion or bring stories alive in readers’ minds. Other academic or technical writing types typically involve more research-based information and are usually more objective in their presentation. Additionally, most forms of non-creative writing will have stricter rules regarding grammar, structure, and syntax.

What is the golden rule of creative writing?

The golden rule of creative writing is to show, not tell. It’s the core creative writing skill. When it comes to creative writing, it’s essential to use descriptive language that immerses readers in the story and allows them to experience the events through their emotions and imaginations. This can be done through metaphors, similes, sensory language, and vivid imagery.

How important is creativity in writing?

Creativity is essential in writing as it allows writers to craft a unique story and evoke emotion from the reader. Creativity can bring stories alive with fresh perspectives and exciting plot lines while creating an escape for readers and giving them more profound insights into the human condition. Writers who combine creativity with technical aspects such as grammar, structure, language usage, and flow will create pieces that capture their audience’s attention and provide an enjoyable reading experience.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Writing Can Help Us Heal from Trauma

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo

Three prompts to get started.

Why does a writing intervention work? While it may seem counterintuitive that writing about negative experiences has a positive effect, some have posited that narrating the story of a past negative event or an ongoing anxiety “frees up” cognitive resources. Research suggests that trauma damages brain tissue, but that when people translate their emotional experience into words, they may be changing the way it is organized in the brain. This matters, both personally and professionally. In a moment still permeated with epic stress and loss, we need to call in all possible supports. So, what does this look like in practice, and how can you put this powerful tool into effect? The author offers three practices, with prompts, to get you started.

Even as we inoculate our bodies and seemingly move out of the pandemic, psychologically we are still moving through it. We owe it to ourselves — and our coworkers — to make space for processing this individual and collective trauma. A recent op-ed in the New York Times Sunday Review affirms what I, as a writer and professor of writing, have witnessed repeatedly, up close: expressive writing can heal us.

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo is an author , TEDx speaker, and founder of Bold Voice Collaborative , an organization fostering growth, resilience, and community through storytelling for individuals and organizations. An adjunct faculty member at DePaul University’s College of Communication, her writing has appeared in venues including The Washington Post, The Guardian, and CNN.com.

Partner Center

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 23 September 2015

Creative writing: A world of pure imagination

- Roberta Kwok 1

Nature volume 525 , pages 553–555 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

7532 Accesses

80 Altmetric

Metrics details

The creative process of writing science-inspired fiction can be rewarding — and the untapped niche is rich in opportunities for originality.

When Steve Caplan was a graduate student in the late 1990s, he accidentally inhaled a toxic chemical in his immunology laboratory, and had to spend ten days at home to recover. With little to do, he began to write a novel — he loved reading and had published some short stories, but hadn't yet had the time or mental space to produce longer work. He pounded out most of a rough draft about a scientist struggling to get tenure and coping with childhood memories of a parent with bipolar disorder.

After going back to work, Caplan — now a cell biologist at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha — spent months revising the manuscript at night and on weekends. His initial attempts to sell the novel to a publisher failed, but in 2009, he decided to pursue the self-publishing route. Caplan produced print and electronic versions of his novel using the Amazon services CreateSpace and Kindle Direct Publishing, and publicized the work by doing readings at bookshops and libraries. He collaborated with his university's public-relations office on a press release, and showed a slide of the book at the end of his seminars. The novel, called Matter Over Mind (Steve Caplan, 2010), has sold more than 2,000 copies so far, netting roughly US$7,000. He has since written two more novels, which he published through small presses, and is now working on a fourth.

For many scientists who spend their days cranking out papers and grant proposals, writing fiction may seem like the last thing they would want to do. But some researchers with a love of literature have made time to pursue the craft — and have found it creatively rewarding. Science offers plenty of rich material, whether it is the drama of overwintering at a polar research station or the futuristic thrill of genetically engineering live organisms. “You're sitting on a gold mine of really interesting stories,” says Jennifer Rohn, a cell biologist at University College London and founder of LabLit.com , a website about portrayals of scientific research in fiction and other media.

A tantalizing niche

When done well, science-related fiction can help to expose the public to the scientific process, humanize researchers and inspire readers to learn about topics they might otherwise ignore. Such nuanced depictions of science in fiction are relatively rare. LabLit.com has catalogued about 200 examples of novels, such as Barbara Kingsolver's Flight Behavior (HarperCollins, 2012) and Ian McEwan's Solar (Random House, 2010), that feature realistic scientists as characters. Stories about scientists are well outnumbered by those about, for example, doctors or artists. Even science fiction tends to lack portrayals of the actual scientific process, says Alastair Reynolds, a science-fiction author near Cardiff, UK, who left a career in astronomy to write full-time.

The shortage of works with accurate depictions of science means that researchers who write fiction have a good opportunity to be original — a task that would challenge an aspiring crime or romance writer. “It's sort of untrampled ground,” says Rohn. Many researchers are familiar with fieldwork sites and unusual settings that other writers might not have at their fingertips. In her novel The Falling Sky (Freight Books, 2013), Pippa Goldschmidt, an astronomer turned fiction writer in Edinburgh, UK, writes about a young astronomer who wanders into a telescope dome on a Chilean mountaintop and is nearly injured when the operator moves the instrument.

Sources of plot inspiration abound in science. Reynolds reads research news and papers voraciously for intriguing elements that can be parlayed into fiction. One time, he found a study about huge flocks of starlings in which the authors used high-tech equipment to track individual birds. He incorporated the idea into a science-fiction story, but made the fictional technology so advanced that it could track the birds' eye movements.

Scientists also can draw ideas from the past. Goldschmidt was inspired by an anecdote about physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer: during an unhappy period in the 1920s while studying abroad, Oppenheimer left a poisoned apple for his tutor. The details are sketchy, but Goldschmidt wanted to imagine what might have transpired. “No historical figure is ever completely understood,” she says. “There's always gaps in their lives, and fiction can inhabit those gaps.” The result was a short story entitled 'The Equation for an Apple', a fictionalized account of Oppenheimer's life leading up to the act.

Scientist–writers can also generate ideas by doing something they are already used to — sitting around and imagining scenarios, notes Andy Weir, a novelist in Mountain View, California. His novel The Martian (Crown, 2014) explores what might happen if a crewed Mars mission goes awry and one person is left behind on the red planet. The story follows the lone astronaut's trials as he tries to grow enough food for himself and to make contact with Earth.

Fiction-writing classes offered through adult-education programmes or at creative-writing centres can help authors to transfer an idea onto the page. These courses provide basic tips, such as how to construct compelling characters, build tension and handle shifts between past and present. Participants often critique each other's manuscripts, giving scientists a chance to get feedback from non-technical readers.

Reading widely and critically helps, too. Reynolds learnt to write fiction by studying the differences between his writing and that of successful authors. To work out how to rotate between different characters' points of view, he read James Ellroy's crime novel L.A. Confidential (Mysterious Press, 1990). And writers can learn how to structure dialogue from masters such as Jane Austen, he says.

Opening act

Short stories are a good starting point because newbies can quickly practise the basics, explore story ideas and learn from their mistakes. But, Goldschmidt notes, “there's no point in writing short stories if you don't like reading them”. Scientists who want motivation to complete a longer work might consider participating in National Novel Writing Month, an international programme held every November that encourages writers of all levels to produce a 50,000-word manuscript (see nanowrimo.org ). Researchers can also find support through collaboration with professional writers on works of fiction (see 'Meeting of the minds').

boxed-text Researcher–writers should keep in mind that education is not the main purpose of fiction. Technical details should be included only if the reader needs them to understand the story, not simply because the author finds them fascinating. For The Martian , Weir went to great lengths to ensure accuracy, and even performed orbital-dynamics calculations. But he left out how he came up with certain numbers, such as the mass that had to be removed from the ship to achieve escape velocity.

When technical information is necessary, writers should try to deliver it in a way that sounds natural. “People don't tell each other a whole bunch of information about particle physics when they're having breakfast together,” says Goldschmidt. Instead, she tries to make the science an organic part of the character's personal journey. In the Oppenheimer story, the physicist thinks about an experiment that he is trying to replicate, but the details are woven into his emotional turmoil at failing to complete it.

Humour can help to lighten the tone. The Martian 's protagonist is a smart-aleck, and his jokes break up the expository text. In one section, he says that if he were exposed to damaging solar radiation, he would “get so much cancer, the cancer would have cancer”.

The path to press

Many outlets accept short-story submissions. LabLit.com often publishes fiction by scientists, although it does not pay them because it is a volunteer effort. Nature runs an 850- to 950-word science-fiction story each week (see nature.com/futures ). The website Duotrope.com offers a searchable database of literary journals and other fiction markets around the world, and writers can peruse newsstands for sci-fi magazines such as Analog Science Fiction and Fact .

For longer works, small presses are a more-realistic option than major publishers, and many do not require writers to have agents. Tasneem Zehra Husain, a theoretical physicist and writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts, wrote a novel that revisits physics breakthroughs throughout history from the perspectives of fictional characters. Through an acquaintance, she connected with the publisher Paul Dry Books in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which released her book Only the Longest Threads last year. To find small presses, scientists can look for companies that have published similar books. Alternatively, authors could self-publish using a service such as Lulu.

Many literary journals do not pay at all, and Reynolds estimates that science-fiction magazines have paid him an average of only US$200–300 per story. But the contacts that Reynolds made through short-story publishing led to a book deal, and he published four novels while working as an astronomer. By the time he quit science to become a full-time writer, he was making about $60,000–$75,000 per year from book sales.

The write balance

Few scientists can expect to make a living — or earn much — from their fiction. But money often isn't the main motivation. Caplan, for his part, wanted to bring attention to the challenges faced by the family members of people with bipolar disorder (challenges he himself has experienced) and to provide entertainment for scientists. He also finds that writing fiction clears his head, in the same way that playing a sport might do for others (see Nature 523 , 117–119; 2015). “It's almost like a form of meditation,” says Caplan. “It just keeps me sane.” And there are other rewards. Scientists have a chance to reach people who might not read a non-fiction science book or visit a natural-history museum — but who might read a love story about ecologists in an exotic field location. And readers might be inspired to look up the science once they've finished.

Scientists have a chance to reach people who might not read a non-fiction science book or visit a museum.

There can also be a cross-training effect. Rohn thinks that her fiction has helped her to get more grants; reviewers have commented that her proposals are beautifully written. The craft of telling a story applies to scientific papers as well; in hers, for example, she lays out the phenomenon that her team noticed, the questions it raised and what they did to try to answer those questions. “Everybody wants to hear a story,” she says.

Finding the time to write is a challenge. Some scientists squeeze it in on evenings and weekends. Husain wrote her book while working part-time, and says that she could not have done so with a full-time job because the novel required extensive historical research.

Scientist–authors also risk having their fiction perceived as a distraction by promotion committees. Husain worried that her novel might affect her career prospects. But she has received positive feedback on the book from other physicists, including prominent researchers whose fields are described in her book.

For researchers who delve into fiction writing, the act of creating a world, characters and stories can be intensely rewarding. When the writing is flowing, says Rohn, “it's like being caught up in the best book you've ever read”.

Box 1: Meeting of the minds

Scientists who are too daunted or busy to write fiction can pair up with a professional writer. Comma Press in Manchester, UK, for example, has published four short-story anthologies — a fifth comes out this October — as part of its 'Science-into-Fiction' series. Each scientist suggests a few research items or emerging technologies for inspiration, and a writer chooses one to develop into fiction. The researcher provides technical guidance, reviews the draft and writes an afterword explaining the science in detail.

The partnership is satisfying because scientists see their work portrayed in a real-world context, and the writer can raise social or ethical implications that the researcher may not have considered, says Ra Page, who founded Comma Press. One scientist studied how nanotechnology could improve body armour, which could have military applications. The writer penned 'Without a Shell', a tale of a futuristic society in which children at an elite school have 'smart' uniforms that heal their injuries, while kids at a poor school do not. Comma Press included the work in its 2009 anthology, When It Changed . An upcoming collection will focus on fabrication technology, such as 3D printers; interested researchers can contact Page to take part.

Scientists also can offer to answer questions from fiction writers through the Science and Entertainment Exchange, run by the US National Academy of Sciences in Washington DC. For instance, a novelist might want to know what types of equipment a researcher would carry in the field. Scientists can call 844-NEEDSCI (toll-free in the United States) to volunteer (see go.nature.com/e6juh9 for more).

Researchers can also partner with faculty members in their universities' creative-writing departments, suggests Page. Authors do not need experience writing about science, but it helps if they have been commissioned to write about specific topics before. When collaborating, “allow the writer to make silly suggestions”, says Page. An idea that at first seems impossible may be plausible after further thought.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Roberta Kwok is a freelance writer in Seattle, Washington.,

Roberta Kwok

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Related links

Related links in nature research.

More lab in the library

Experimental fiction

Quantified: Futures

Where might it lead?

Q&A: David Brin on writing fiction

Nature blogpost: How to write for Nature Futures

Nature blogpost: Transitions — combining science and novel writing

Nature blogpost: More bang for your book

Nature blogpost: Plotting a role for scientists in fiction

Related external links

Steve Caplan

Pippa Goldschmidt

Alastair Reynolds

Tasneem Zehra Husain

Comma Press's 'Science-into-Fiction' series

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kwok, R. Creative writing: A world of pure imagination. Nature 525 , 553–555 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nj7570-553a

Download citation

Published : 23 September 2015

Issue Date : 24 September 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nj7570-553a

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Catharsis in Psychology