- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- The ALH Review

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About American Literary History

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Works cited.

- < Previous

Back to Black: African American Literary Criticism in the Present Moment

Kenneth W. Warren is Professor of English at the University of Chicago. His most recent book is What Was African American Literature? (Harvard UP, 2011). He is also coeditor (with Adolph Reed Jr) of Renewing Black Intellectual History: The Ideological and Material Foundations of African American Thought (Routledge, 2009) and (with Tess Chakkalakal) of Jim Crow, Literature, and the Legacy of Sutton E. Griggs (U of Georgia P, 2013).

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Kenneth W Warren, Back to Black: African American Literary Criticism in the Present Moment, American Literary History , Volume 34, Issue 1, Spring 2022, Pages 369–379, https://doi.org/10.1093/alh/ajab082

- Permissions Icon Permissions

For more than a century, scholars of Black literature have sought to align a critical project focused on identifying and celebrating Black distinctiveness with a social project aimed at redressing racial inequality. This commitment to Black distinctiveness announces itself as a project on behalf of “the race” as a whole, but has always been, and remains, a project and politics guided in the first instance by the needs and outlook of the Black professional classes. Over the first half of the twentieth century, this cultural project achieved some real successes: politically, it helped discredit the moral and intellectual legitimacy of the Jim Crow order that in various ways affected all Black Americans; culturally, it placed Black writers in the vanguard of a modernist project predicated on multicultural pluralism. Since the 1970s the limitations of this project, culturally and politically, have become increasingly evident. Blind to the class dimension of their efforts, literary scholars continue to misrepresent the historical/political nature of the project of Black distinction as a property of cultural texts themselves. Overestimating the efficacy of race-specific social policies, these scholars disparage the universalist social policies that would most effectively benefit a majority of Black Americans.

Over the last 30 or so years, beginning with an essay-review published in the inaugural issue of this journal, I’ve sought to highlight the insufficiencies of any intellectual project seeking to ground Black literary criticism and scholarship in the idea of Black distinctiveness. Such an effort not only imposes onto Black Americans as a whole a sensibility reflective of an elite, increasingly wealthy, stratum of the Black population, but it also fails in its primary goal of accounting for the literature that is its chief object of interest. As I noted in that first essay, even the most theoretically ambitious version of this effort, Henry Louis Gates, Jr’s attempt to define a vernacular theory centered on the trope of “Signifyin(g),” falls short of its target. The features that presumably relate Black texts to one another in a way that is specifically Black are, by Gates’s own admission, neither unique to “Black” texts nor universal across them, but rather “metaphors for black literary relations” derived, on the one hand, from vernacular poems and tales, and on the other, from more formally recognized Black literary works (47).

What occasions this look backward in considering the role of American literary criticism at the present moment is my sense that despite the political, social, and economic upheavals of the last 25 years or more—and especially those that have emerged since the 2008 financial crisis—which have as their most visible outcome a dramatic upward distribution of wealth more severe than what occurred during the late nineteenth century which gave us the term “the Gilded Age”; despite a widely shared view among Black Studies scholars that the field’s raison d’être is, in some way, to intervene in the processes that contribute to adverse social outcomes that disproportionately affect Black Americans; and despite widespread protestations that these disparities have not appreciably diminished but have, rather, persisted and intensified during the first two decades of the twenty-first century, the dominant response within African American or Black literary production, criticism, and scholarship has not been to question or rethink the presumption that a Black Studies project can do anything other than what it has always done, namely, assist in funneling the multivariate concerns of Black Americans into forms of social analysis and recommendations for intervention that hinge upon the revelation of an issue’s racial dimension. As long ago as 1939, Ralph Bunche, writing in The Journal of Negro Education , identified the shortcomings of “American Negro organizations and leaders” by observing:

Color is their phobia; race their creed. The Negro has problems and they are all racial ones; ergo, their solution must be in terms of race. In general, whites must be regarded with suspicion, if not as enemies. White allies are recruited, it is true, but only from those who think of Negro problems as Negroes think of them. There is impatience with any but race problems… . As long as the Negro is black and the white man harbors prejudice, what has the Negro to do with class or caste, with capitalism, imperialism, fascism, communism or any other “ism”? Race is the black man’s burden. (539–40)

Substitute the word “Blacks” for Bunche’s use of the term “the Negro” and you almost have a description of the current moment. But where Bunche posits among Black organizations and leaders a lack of broad interest in a variety of “isms,” the present practice is to subsume all other matters under race, so that, for example, capitalism becomes “racial capitalism” or caste, as in Isabel Wilkerson’s recent book, is recast as explanation of racism, or the only pertinent questions to pose to Marxist analysis is whether it reflects prevailing understandings of racism. So that, while the factors contributing to, and resulting from, upward wealth distribution, including an ideological assault on the very idea of the public good and attacks on unions and unionization campaigns pose dire threats to all working Americans, the primary intellectual thrust within the Black Studies regime has been to intensify and thereby to attempt to radicalize the idea of Black difference and distinctiveness. My point is not to deny neither the many distinctive and powerful expressive forms that have emerged from African-descended people nor the ways these forms have influenced and will likely continue to influence subsequent writers, artists, and performers. What I am arraigning is the idea that any of these forms individually or collectively can be treated as coextensive with the manifold sensibilities of the nation’s, or the world’s, Black populations. Yet, in contemporary parlance, “Blackness” is often uttered with an assumption of the self-evidentiary status of the term, masking the way that it operates as a presumption that some factor will of necessity emerge to distinguish the social, cultural, and political activities of African-descended people from those of everyone else. The most extreme form of this tendency, as expressed by Afropessimists and philosophers of antiblackness, holds that “Antiblackness, part and parcel of racial slavery and its afterlife, remains the extreme antisocial condition of possibility of the modern social world” (Costa Vargas and Jung 4). While such a view derives its force from statistical disparities indicating that poor and working-class Black Americans face conditions more precarious and dangerous than their nonblack counterparts, its more practical effect is to exempt Black political elites from analysis in terms of their roles in reproducing the prevailing political order. As Adolph Reed, Jr and I noted in 2011, because “the sedimented premises of elite debates are no longer scrutinized systematically, they have become too easily naturalized among the background assumptions that guide African American studies as a field of scholarship” (viii). Instead, probabilities, such as the statistically greater likelihood that, in comparison to our nonblack counterparts, I, and people who look like me, might become the object of police violence, are invoked to project onto all Black people an “ever-present sense of impending doom” (Costa Vargas and Jung 4). What such a view does—and what it has always done since the late-nineteenth century—is burnish the credentials of Black intellectuals, whose job is to produce expression and analysis, in their claim to represent a degraded population, presumably unable to turn anywhere else in solidarity around a goal of building a better world.

So, I think it remains crucial to locate the origins of the project of Black distinctiveness, politically and historically, in the “cultural turn” of the late 1890s and first decade of the twentieth century that followed Black disfranchisement and arose with the consolidation of the Jim Crow regime. With Blacks throughout the southern states largely removed from the political arena and white southern workers demoralized as a political force after the defeat of Populism, political movements in the southern states took a decided turn away from direct political action. Disfranchisement, in the words of Judith Stein:

… encouraged among northern blacks petit-bourgeois notions like [W. E. B.] Du Bois’s “talented tenth.” Although northern black leaders personally possessed more rights, they were basically proposing solutions for all the black people, nine-tenths of whom were southern. The prevalent northern ideologies, like southern, were based upon appeals to the ruling elements of society. Whereas [Booker T.] Washington tried to persuade whites of their self-interest, Du Bois appealed to their sense of justice and morality. Although Washington urged blacks to build up racial enterprises and Du Bois to fight for constitutional rights, both positions fused in practice. The two leaders perceived their roles as elevating a passive population. (“Of Booker T. Washington” 42)

This form of political action, centered on the idea of leadership, unelected but presumably attuned culturally and spiritually to the needs and desires of the race as a whole and, on that basis, able to speak for all Blacks, became the prevailing racial ideology of the last century. The idea of “Race relations,” which Stein and Michael Rudolph West have shown was invented by Washington, has been virtually naturalized as the idiom for thinking about equality in the US.

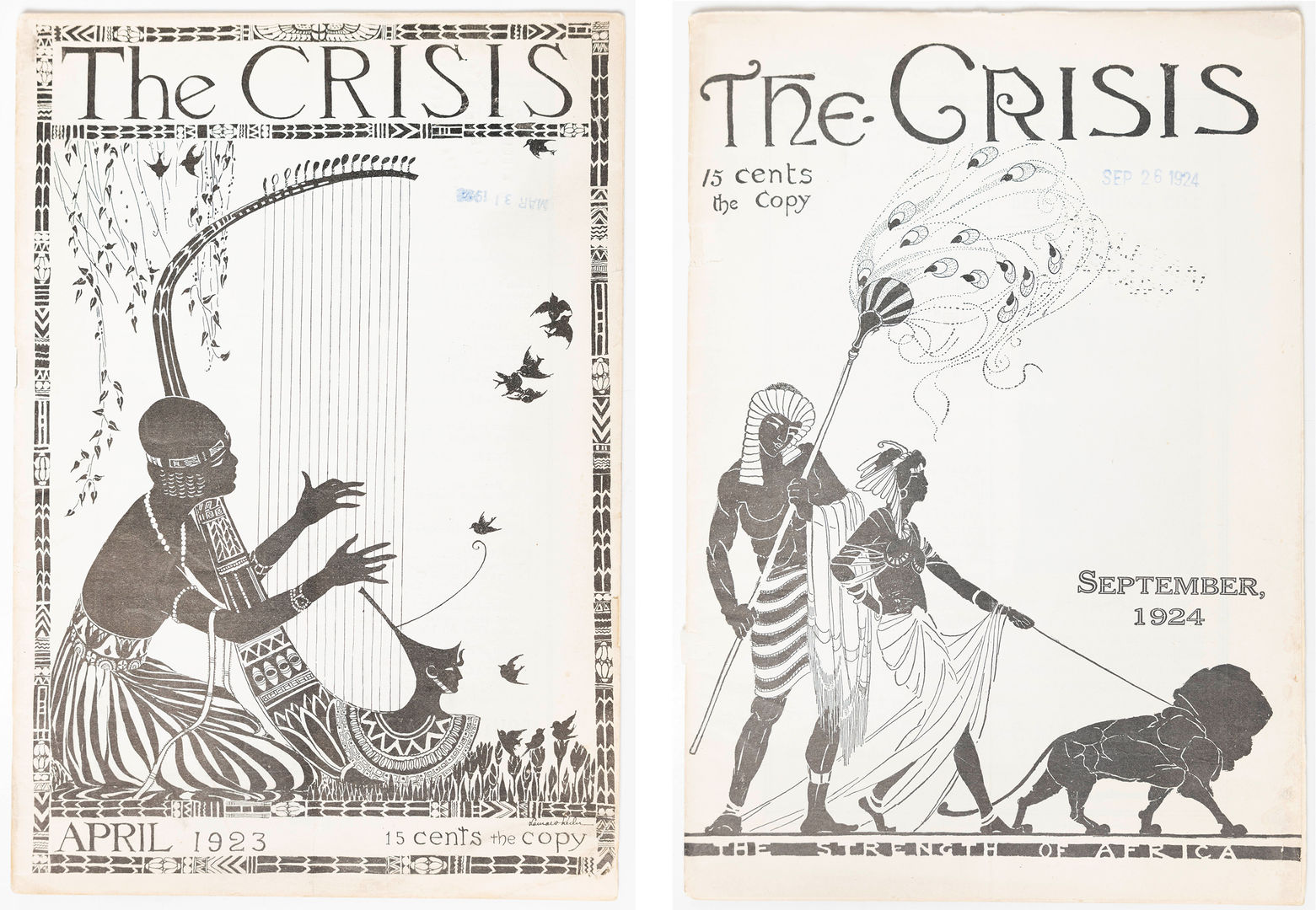

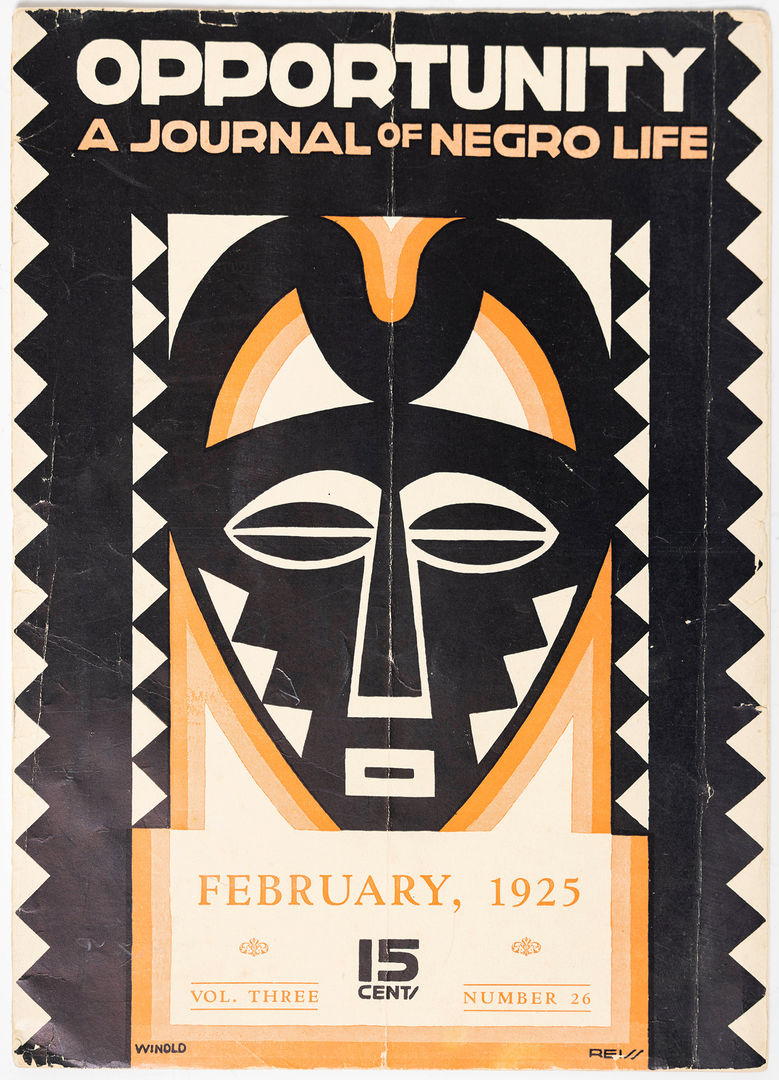

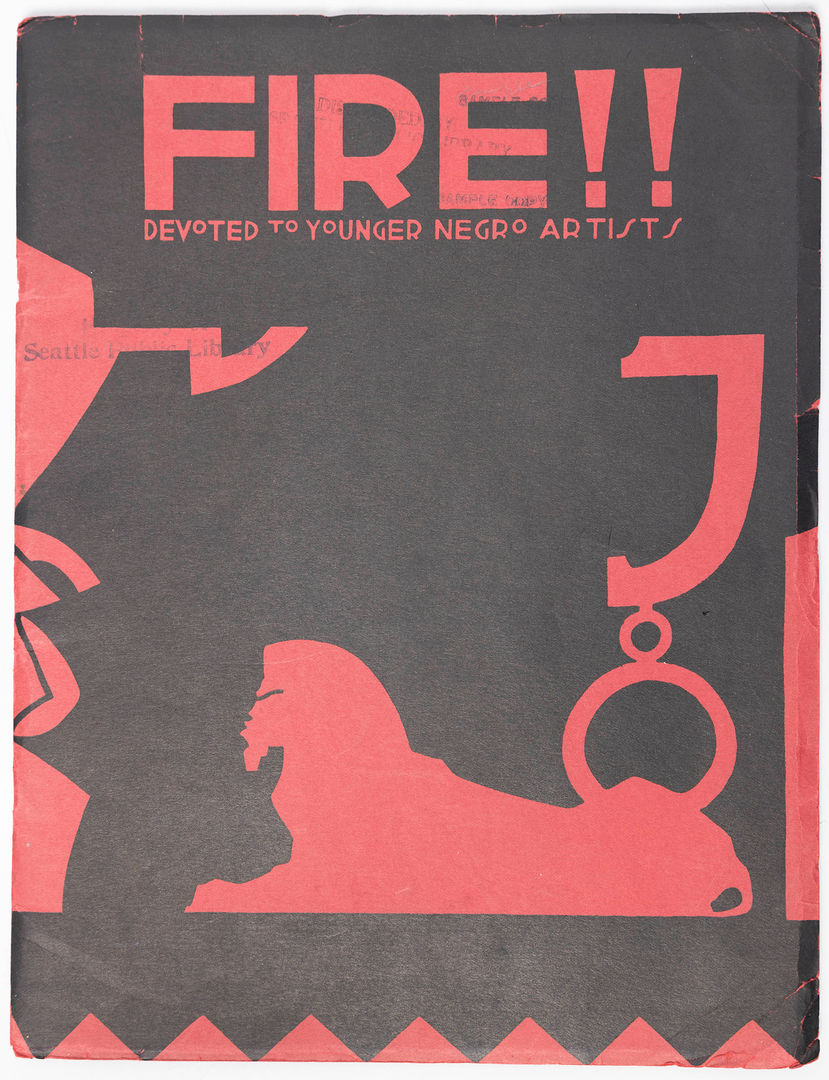

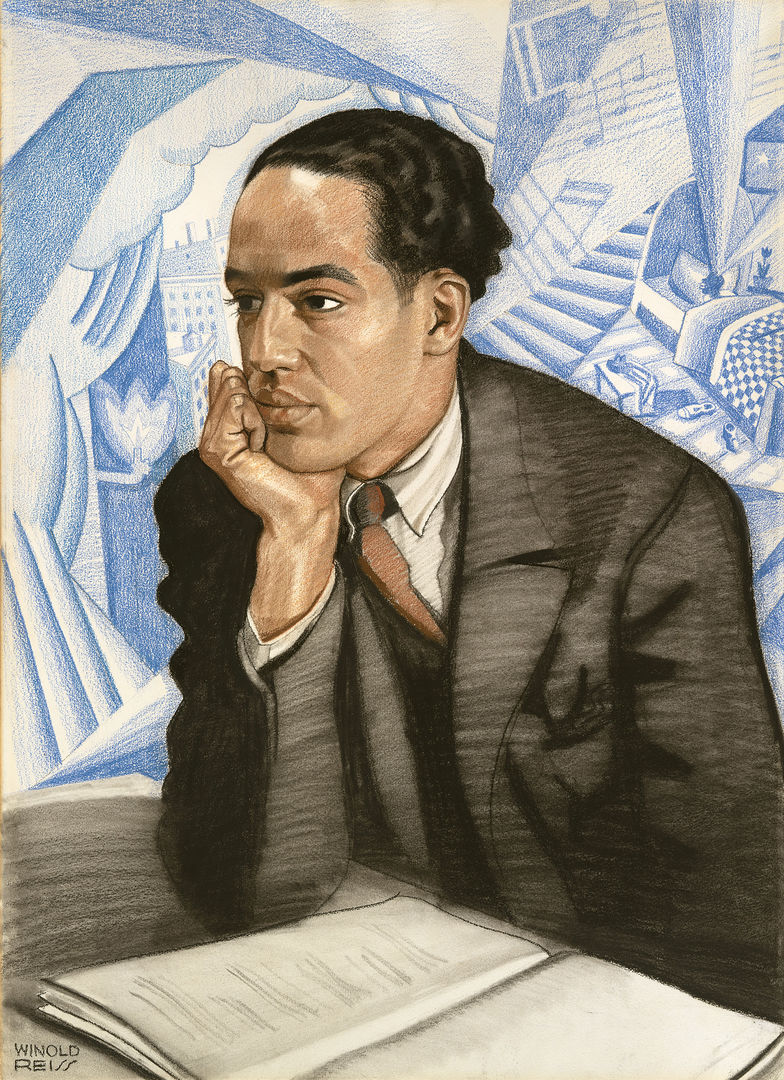

Even now, as we enter the third decade of the twenty-first century, the recurrent complaints that the nation has yet to “come to terms with race” or has postponed a necessary “national conversation” about race are symptomatic of the persistence of Washington’s “theory of race relations” which sought to assure white Americans that it was “‘the Negro’ America faced, rather than croppers and farmers, workingmen and workingwomen, business owners and politicians, teachers and parents with various interests and deep claims on the American nation” (West 56–7). And while Washington was notoriously disdainful of the imperative that Blacks should turn their attentions to literary pursuits, the concept of African American literature—the idea that a body of literary works could help clarify, consolidate, and direct the aims of the race (however complexly conceived)—was at its conception, and remains at present, nothing more than the expressive arm of the race relations project. When Alain Locke laid out the program for The New Negro in 1925, he made the connection explicit, arguing that the race’s “more immediate hope rests in the revaluation by white and black alike of the Negro in terms of his artistic endowments and cultural contributions, past and prospective” and that this “cultural recognition . . . should in turn prove the key to that revaluation of the Negro which must precede or accompany any considerable further betterment of race relationships” (15).

The appeal of the idea of African American literature, like the appeal of the idea that the best way to achieve social justice is through an enhancement of the “in-group cohesion and cultural solidarity” that had already been created among Blacks by a shared history of slavery and the ongoing experience of segregation, has been underwritten by reality, lived experience, and other prevailing beliefs (Bell 18). In a segregated society it was often the case that the most immediate way of acting politically was to do so in concert with one’s fellow Blacks; in a, Jim Crow society where, to quote Du Bois, being forced to “ride ‘Jim Crow’ in Georgia” (666) was a highly reliable way of distinguishing Black from white, the political actions of small groups of elites challenging the laws and codes that prescribed these practices responded directly to the system that sought to degrade all Blacks. In a racist society that, as part of the myth of race it had produced, inclined to the idea that to be Black was to be predisposed to expressiveness, Black literature and the arts as a collective undertaking could count on a claim to attention they might not have otherwise enjoyed. It was this sort of prejudice that Locke had anticipated in his program for the New Negro. Even more powerfully, the aesthetic that prevailed over US modernism in the 1920s, which Walter Benn Michaels has termed “nativist modernism” to describe the projects not only of Black writers of the period but virtually all of that moment’s major writers, made identity “an ambition as well as a description” (3) and thereby helped firmly establish the pursuit of literary and cultural distinctiveness as the shared horizon of artistic achievement.

Although race relations overshadowed the political life of Black Americans, it did not exhaust or describe the full range of Black political action across these decades. As noted earlier, it was the interracial dimension of Populism that had provoked the backlash of violence and disfranchisement that established Jim Crow. And while Black elites tended to style themselves as speaking for the race as a whole, Black workers, even in the Jim Crow South where political organizing was difficult, were likely to present themselves in terms of their class, even as they called upon other members of their race to support their efforts. As Stein reports, Florida longshoremen on strike in 1919 reached out to the President of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) with an appeal that in the first instance “stressed membership in a class; the second, a race” (“Defining” 76). That same year, in town of Elaine in Phillips County, Arkansas, Black sharecroppers sought to organize as members of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA) to demand from landowners a fair return for their crops. Their effort that was met by appalling violence in what became known as the Elaine Massacre, when armed whites killed over 200 Black residents. In the wake of the violence, scores of Blacks, but no whites, were charged with crimes, including 79 murder indictments.

So, it was in large part a desire to manage and avoid the violence of what is now called the Red Summer of 1919 that guided Locke’s turn to culture in The New Negro . As Barbara Foley notes, during the 1920s the struggle for equality “would increasingly become one over the Negro’s right to represent, and be represented in, the Fatherland—not in the political sphere (a battle that would be deferred for some forty more years) but in the realm of culture” (120). But while the backlash against political organizing in the South was severe, the subsequent miscarriage of justice following the Elaine Massacre touched off a response that would prove consequential. In a case that would eventually reach the Supreme Court as Moore v . Dempsey (1923), the NAACP successfully argued that the defendants’ Fourteenth Amendment rights to due process under the law had been violated. The resulting decision was “a great constitutional victory on due process grounds,” which shaped the subsequent legal strategy of the NAACP in litigating against Jim Crow (Stockley et al. 30). The larger point here is that class politics was capable of playing a vanguard role in achieving equality for all Black Americans. This possibility became more apparent in the next decade when labor politics was in ascendancy. As Touré Reed has shown, New Deal labor laws, including the Norris-La Guardia Act (1932), the Railway Labor Act of 1934 and the National Labor Relations Act (1935), gave “legitimacy” to organized labor that “sparked a transformation of black politics” in ensuing years. As a result, “African Americans of the 1930s and 1940s came to see race discrimination as an outgrowth of class equality.” Indeed, “by the early 1930s mainstream civil rights organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and [the National Urban League] NUL began to emphasize the broader advance of the American working class as key to black uplift” (T. Reed 27–8). During this period, sentiments such as that voiced by A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the National Negro Congress, that “no black worker can be free so long as the white worker is a slave and by the same token, no white worker is certain of security while his black brother is bound” were shared across a variety of political and social organizations (qtd in T. Reed 39). In short, the forces of what Preston Smith has termed “social democracy” (for example, those who felt that the best way to attack housing inequality and discrimination was to improve dramatically the quality and affordability of housing stock for working-class Americans across the board, a group that included the majority of Black Americans) had gained traction against those who formulated a vision of justice in terms of “racial democracy,” which stressed nondiscriminatory access to existing housing over an attack on the presumption of the justice of a class-stratified housing market. 1 Intellectual analysis followed suit as Ralph Bunche’s A World View of Race (1936) and Oliver Cromwell Cox’s Race, Caste, and Class (1948) challenged presumptions that racial group formation was the natural form of political organizing across the globe.

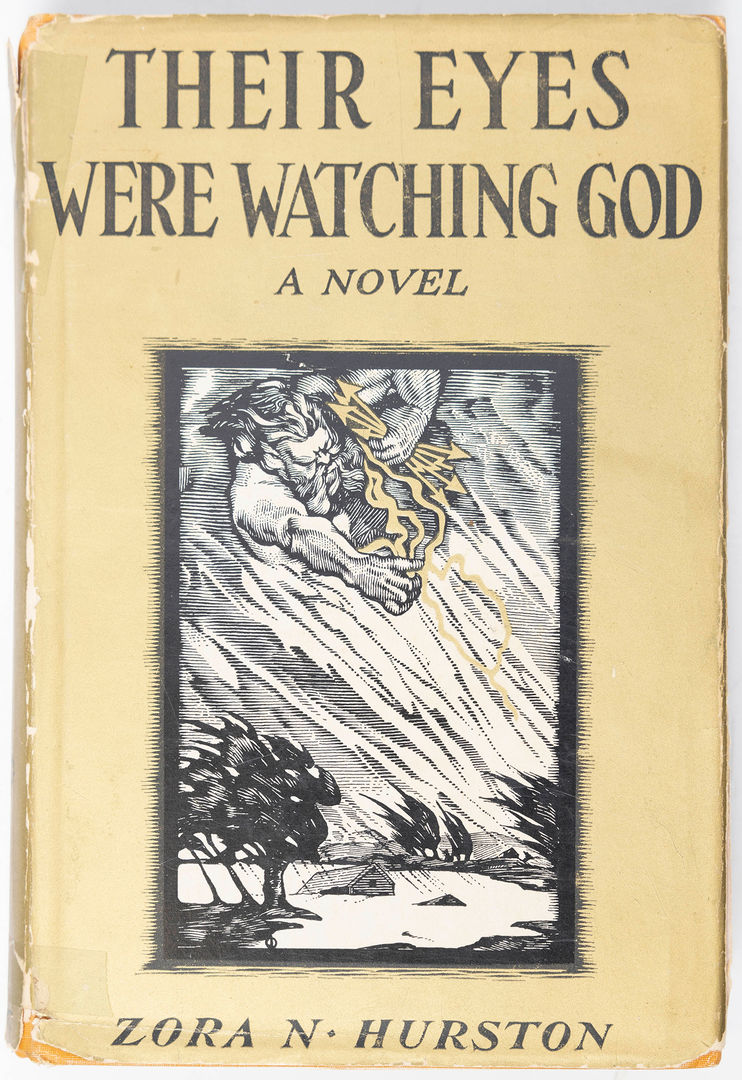

The effect of this political shift played out variously in debates about Black literary production. By 1950, Phylon magazine was publishing a forum, “The Negro in Literature,” in which one of the framing questions posed by the editors, Mozell C. Hill and M. Carl Holman, was, “Would you agree with those who feel that the Negro writer, the Negro as subject, and the Negro critic and scholar are moving toward an ‘unlabeled’ future in which they will be measured without regard to racial origin and conditioning?” (296). The participating writers were far from unanimous in their responses, but the seriousness with which the question was posed attests to a receptiveness to the idea that a socially progressive politics did not require as a corollary a racially distinct literature. In a recent study of the period, George M. Hutchinson has echoed the observation that I made in What Was African American Literature? (2011) that during this moment references to “The Literature of the Negro” were “just as likely to include fiction by white writers who wrote with sensitivity about race” as works by Black writers (Warren 56; see also Hutchinson 201). The championing of universalism as a literary value, which Hutchinson, along with Richard H. King have noted was on the rise during this period drew from a variety of ultimately incompatible sources including Marxism and liberalism, a situation that, with the onset of the Cold War, stacked the deck against the more radical forms that universalism might have taken. Additionally, many of the literary works most visibly associated with this tendency were less artistically accomplished than earlier works by the same writers that had foregrounded racial themes. Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), Richard Wright’s Native Son (1940), Ann Petry’s The Street (1946), and William Gardner Smith’s The Last of the Conquerors (1948) were aesthetically stronger than subsequent works by these writers that did not adhere to the contours of racially defined Black communities: Hurston’s Seraph on the Suwanee (1948), Wright’s The Outsider (1953), Petry’s Country Place (1947), and Smith’s Anger at Innocence (1950). With no masterwork to anchor it, this sensibility did not exert significant force on subsequent literary production by Black writers.

The success of the civil rights movement across the 1950s and 1960s in toppling the legal pillars of Jim Crow resulted in the reemergence of Blacks into the nation’s civic life and into the domain of electoral politics in the South. It also spurred real economic gains for portions of the Black population: “Between 1968 and 2016, African Americans, largely as a result of the victories of the civil rights movement and anti-discrimination enforcement, made significant advances into occupations and job categories that had previously kept black workers at the margins of mainstream success—when they admitted them at all” (A. Reed 10). These advances, coupled with the rise of elected Black officialdom to complement the appointees who had played a directive role in the race relations regime, were some of movement’s most signal victories. These victories, however, marked the structural limits of these politics. The now well-known story of the post-Civil Rights era is a tale of the persistence of disparities between the nation’s Black and white populations. For example, a recent study on wealth disparity between Blacks and whites begins by observing, “The stubborn persistence of racial income disparities has been a core frustration of American social policy for the past 50 years” (Manduca 182).

Particularly of concern has been the fate of the most economically impoverished segment of the Black population, a group that William Julius Wilson has called the “black underclass,” whose immiseration has seemed to lie beyond the reach of the usual measures of political and economic redress (vii). It is the condition of this population that has helped bring together the elite brokers of racial democracy and Black Power activists, whose political leverage has turned on claims to represent this group, claiming them as their virtual constituency whose unmet needs give urgency to the proposed solutions being put forth on their behalf. Somewhat paradoxically, but at a second glance perhaps necessarily, all of these would-be spokespeople turn to cultural means to explain the situation of this group and its means of redress. For elected officials, the lack of skills and educational attainment among this population have been cited as causes of their recalcitrant impoverishment, a diagnosis that could be met by demands for expanded educational and training programs. For Black Power advocates who cited the baleful effects of the imposition of a Eurocentric curriculum on, and the inculcation of Western values into, the sensibilities of Black people, education—albeit of a quite different sort—has been the answer as well. And while Wilson’s work insists on the structural dimension of the status of this purported “underclass,” he too, in proposing solutions for their plight, “routinely violates his own axiom about the integral relationship between culture and social structure” (Steinberg) in favor of privileging a culturalist account of a self-perpetuating cycle of poverty that could be broken by changing the beliefs and habits of poor Black Americans along with providing them with appropriate job opportunities. In doing so, his work has remained largely in sync with the elite brokers.

But at this point, I’m virtually back where I began. Wilson, who rose to prominence at the University of Chicago, would go on to join Gates among the African American studies scholars at Harvard, and the vision of a way forward for the race would come to focus on what a Black Studies regime could provide. As I noted in this journal in “The End(s) of African-American Studies”—which I began by quoting Gates’s assertion that “My work is in African American studies . . . Who else is that for if not primarily the black community?” (637)—aligning Black Studies agendas with the political aims of Black Americans generally can hardly escape being a self-interested operation that seeks to sideline analyses emphasizing factors other than race as more important to the wellbeing of most Black Americans. I wrote then, “a black studies agenda must first acknowledge that the very act of studying black America [I should have said ‘black Americans’], however well-intentioned such an effort may be, has been part of the ongoing process of experiencing race as a lived reality.” I then noted that in response, “we need to examine more systematically the history [I should have added ‘and present conditions’] that has sometimes inclined African-Americanist scholars to focus their energies in one direction rather than another” (652). And for some time now that direction appears to have been the wrong one. Increasingly, it seems that the major factor producing disparate outcomes for Black Americans in relation to their fellow citizens is actually something Blacks share with everyone else, namely living in a society defined by dramatic upward distribution of wealth. Robert Manduca, whom I cited earlier in noting the persistence of the wealth gap between Black and white families since the 1960s has shown that while “African Americans have made meaningful progress up the income distribution” ladder:

… . these relative gains were offset by changes to the income distribution that allocated a much smaller share of the national income to the poor and middle class, in which African Americans were and continue to be disproportionately concentrated, and a much larger share to the top 10 percent and especially the top 1 percent—the portions of the distribution that remain the most disproportionately white. As the very rich absorbed larger and larger shares of the economy, the middle class slid back, reducing the payoff in dollars that was associated with progress in rank. These two forces almost perfectly balanced each other, resulting in hardly any net change in black–white income ratios. (195–6)

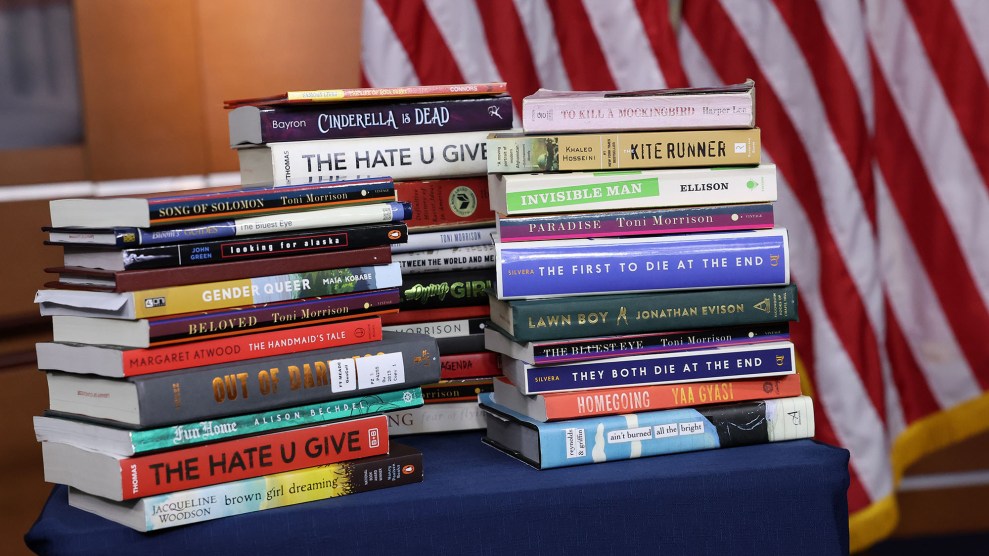

In other words, fighting income inequality for most Americans would be to fight inequality for most Black Americans. When strengthening unions and dramatically increasing the minimum wage would have an immediate and significant impact on the well-being of millions of Black Americans, that we are again at a moment when Black Studies curriculum guides, and a contested tenure decision for a highly honored Black scholar mark the primary line of engagement in what purports to be a fight for social justice is hardly cause for celebration.

Smith distinguishes the ideology of “racial democracy,” which focuses on “the generally perceived need to correct the racial disparities of US democracy to restore it to health, a process and outcome that would confer on African Americans ‘first-class citizenship’ from ‘social democracy [which] attacked the broad inequality of U.S. society that stemmed from distribution of goods and services to a privileged few at the expense of a poor working majority’”(5). The distinction is not meant to disparage the goals of racial democracy but to highlight their inadequacy in achieving a just society.

Bell Bernard. The Afro-American Novel and Its Tradition . U of Mass P , 1987 .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Bunche Ralph J. “The Programs of Organization Devoted to the Improvement of the Status of the American Negro.” The Journal of Negro Education , vol. 8 , no. 3 , 1939 , pp. 539 – 50.

Du Bois W. E. B. “Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept.” Du Bois: Writings, Library of America , 1986 , pp. 548 – 802.

Fields Barbara J. , Fields Karen E. . Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life . Verso , 2012 .

Foley Barbara. Spectres of 1919: Class and Nation in the Making of the New Negro . U of Illinois P , 2004 .

Gates Henry Louis Jr. Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the “Racial” Self . Oxford UP , 1987 .

Hill Mozell C. , Holman M. Carl . Preface . Phylon , vol. 11 , no. 4 , 1950 , pp. 296 .

Hutchinson George. Facing the Abyss: American Literature and Culture in the 1940s . Columbia UP , 2018 .

Jung Moon-Kie , Costa Vargas João H. . “Antiblackness of the Social and Human.” Antiblackness, edited by Jung Moon-Kie , Costa Vargas João H. . Duke UP , 2021 , pp. 1 – 14.

Manduca Robert. “Income Inequality and the Persistence of Racial Economic Disparities.” Sociological Science , vol. 5 , no. 8 , 2018 , pp. 182 – 205.

Locke Alain. “The New Negro.” The New Negro: Voices of the Harlem Renaissance, edited by Locke Alain . Atheneum , 1992 , pp. 3 – 16.

Michaels Walter Benn. Our America: Nativism, Modernism, and Pluralism . Duke UP , 1995 .

Reed Adolph Jr. “Class Matters: The Surprising Cross-Racial Saga of Modern Wealth Inequality.” The New Republic , vol. 251 , no. 7–8 , 2020 , pp. 10 – 11.

Reed Adolph Jr , Warren Kenneth W. . Introduction. Renewing Black Intellectual History: The Ideological and Material Foundations of African American Thought, edited by Reed Adolph Jr , Warren Kenneth W. . Paradigm Press , 2011 , pp. vii – xi.

Reed Touré F. Toward Freedom: The Case Against Race Reductionism . Verso , 2020 .

Smith Preston H. II . Racial Democracy and the Black Metropolis: Housing Policy in Postwar Chicago . U of Minnesota P , 2012 .

Stein Judith. “Of Booker T. Washington and Others.” Renewing Black Intellectual History: The Ideological and Material Foundations of African American Thought, edited by Reed Adolph Jr. , Warren Kenneth W. . Paradigm , 2010 , pp. 19 – 50 .

Stein Judith. . “Defining the Race 1890–1930.” The Invention of Ethnicity, edited by Sollors Werner . Oxford UP , 1989 , pp. 77 – 104 .

Steinberg Stephen. “Poor Reason: Culture Still Doesn't Explain Poverty,” Boston Review , 13 Jan. 2011 . Web.

Stockley Grif , Mitchell Brian K. , Lancaster Guy . Blood in their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919 . 2001 . U of Arkansas P , 2020 .

Warren Kenneth W. “The End(s) of African-American Studies.” American Literary History , vol. 12 , no. 3 , 2000 , pp. 637 – 55.

Warren Kenneth W. What Was African American Literature ? Harvard UP , 2011 .

West Michael Rudolph. The Education of Booker T. Washington: American Democracy and the Idea of Race Relations . Columbia UP , 2006 .

Wilson William Julius. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy . 2nd ed., U of Chicago P , 2012 .

Author notes

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-4365

- Print ISSN 0896-7148

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

History of Black Writing

Building lasting change in the American literature canon and supporting the legacy of African-American writers, the History of Black Writing (HBW) nurtures research opportunities for students, writers, and scholars.

About

HBW is a research center focused on elevating innovative scholarship in American literature, book history, and digital humanities.

Celebrating 40 Years of HBW!

Since 1983, the History of Black Writing (HBW) has been dedicated to the study of Black Writing.

History Timeline

Interactive Research and Public Engagement

HBW's research and collection building creates a corpus of fiction and non-fiction to drive public program initiatives such as the Black Literary Suite and Gems, and research institutes like Hurston on the Horizon in 2021.

Connect with HBW

HBW is an expanding community of scholars and researchers. See what events are happening by connecting on social media.

Journal of African American Studies

- Examines the dynamics and conditions affecting the life opportunities of African descended peoples globally.

- Features empirical, methodological, and theoretical papers, alongside literary criticism.

- Covers a wide spectrum of interdisciplinary fields including anthropology, art, economics, law, literature, management science, political science, psychology, sociology, and social policy research.

- Aims to publish research with real-life implications for the social, political, and economic progress of African descended peoples.

- Judson L. Jeffries

Latest issue

Volume 27, Issue 4

Latest articles

The disproportionate use of corporal punishment on african american children in u.s. schools.

- Kahlil Green

- Devron Dickens

- Laurens G. Van Sluytman

Charisse Burden-Stelly. Black Scare / Red Scare: Theorizing Capitalist Racism in the United States

- Mark Christian

Marjorie Corbman: Divine Rage: Malcolm X’s Challenge to Christians

- Jimmy Butts

A Black Studies Professor Who Talks the Talk and Walks the Walk: A Conversation with OSU Professor and Editor-In-Chief of the Journal of African American Studies , Judson L. Jeffries, PhD

- Kevin L. Brooks

Black Women in the Ivory Tower: Institutional Oppression and Intersectionality

Journal updates

Good news: journal of african american studies has achieved its first impact factor.

Join us in congratulating Journal of African American Studies for receiving their first Impact Factor

Open Access Articles

Read open access articles published in the Journal of African American Studies .

Journal information

- Emerging Sources Citation Index

- Google Scholar

- MLA International Bibliography

- Norwegian Register for Scientific Journals and Series

- OCLC WorldCat Discovery Service

- TD Net Discovery Service

- UGC-CARE List (India)

Rights and permissions

Springer policies

© Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

African american studies.

- Civil Rights

- Digital Primary Sources

- Environment

Articles and literary works

Black literature, 1827-1940, cambridge literature online, encyclopedias and dictionaries, selected works on the harlem renaissance, primary sources.

- Librarian for History and African American Studies

- Microfilm Collections

- Organizations

- Personal Papers

- Religion This link opens in a new window

- Plantation life

- Graphic Arts

- Manuscripts

- Slavery, p. 1

- Slavery, p. 2

- African Americans and Princeton

- Archival Collections

- Public Policy Papers

- Slavery at Princeton

African American Poetry Database (1750-1900)

Contains nearly 3,000 poems by African-American poets of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

African-American Poetry, Twentieth Century

Full-text access to about 10,000 poems from around 70 20th century African American poets.

Black Drama Second Edition (1850+)

Full text of plays written by dramatists from Africa, the Caribbean, and North America, and detailed information about productions, theaters, production companies, and other ephemera related to the plays.

Black Short Fiction

Full text of 760 stories and folktales by African, African American, and Caribbean authors.

Black Thought and Culture

Full-text collection of published non-fiction works is included, as well as interviews, journal articles, letters, and other materials of leading African-Americans. Biographical essays by leading scholars and an annotated bibliography of the sources in the database are also featured.

Black Women Writers

Note: You must install Flash version 8 or higher to use.

Works of fiction, nonfiction and poetry by women from North America, Africa and the Caribbean.

Contemporary Authors (Literature Resource Center)

Provides full text of biographies, bibliographies, literary criticism, and other resources on authors of all categories and eras.

Contemporary Literary Criticism (Literature Resource Center)

Dictionary of Literary Biography (Literature Resource Center)

Essay and General Literature Index (1900+)

Access to essays and articles published in collections, with emphasis on works in the humanities and social sciences.

LION: Literature Online

Full text of more than 350,000 works of English and American literature and poetry, fiction, drama, from the seventeenth century to the present, as well as works of literary theory from Plato to the present.

Literature Criticism Online

Covers authors and their works across regions, eras, and genres. Includes biographical and critical overviews, and many interviews of authors. Contains the full text of volumes in Contemporary Literary Criticism, Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism, Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism, Literature Criticism 1400-1800, Shakespeare Criticism, Classical & Medieval Literature Criticism, and Drama Criticism.

Literature Compass (2004+)

Peer reviewed survey articles in literature.

Literature Resource Center

Literary Reference Center (Antiquity+)

Broad spectrum of reference information. Full-text database that combines information from over 1,000 books and monographs, major literary encyclopedias and reference works, hundreds of literary journals, and unique sources not available anywhere else. Contains detailed information on the most studied authors and their works.

MLA International Bibliography (1926+)

Provides citations to articles, books, book chapters, and dissertations on all aspects of modern literature, language, and linguistics.

- Humanities Source Ultimate This link opens in a new window Encompasses all key fields of the humanities. Content includes feature articles, interviews, obituaries and original works of fiction, drama, poetry, and reviews. 1925+

Black Literature, 1827-1940 . Microfiche 1648. Location: Microforms Services on A-floor in Firestone Library. Location has: Units 1-15 (2800-2997)

Contains fiction, poetry, book reviews, and literary notices originally published in 900 black periodicals and newspapers.

Cambridge Collections Online (Princeton access only)

Searchable full text access to the complete Cambridge Companions to literature, philosophy, religion, and classics.

The Companion to African American Women’s Literature

The Cambridge Companion to August Wilson

The Cambridge Companion to Frederick Douglass

The Cambridge Companion to Ralph Ellison

The Cambridge Companion to the African American Novel

The Companion to the African American Slave Narrative

The Cambridge Companion to the Harlem Renaissance

The Cambridge Companion to Toni Morrison

The Cambridge Companion to W.E.B. Du Bois

African American Authors, 1745-1945: Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook. Edited by Emmanuel S. Nelson. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2000. Also in print (F) PS153.N5 A32 2000

African American Writers. Valerie Smith, editor-in-chief. 2 nd ed. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, c2001. (F) PS153.N5 A344 2001

The Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature . Edited by, William L. Andrews, Frances Smith Foster, and Trudier Harris. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. Also available in print: (F) PS153.N5 C59 2001

Contemporary African American Novelists: A Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook . Edited by Emmanuel S. Nelson. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1999. Also available in print: (F) PS374.N4 C658 1999

Encyclopedia of African-American Literature. Edited by Wilfred Samuels. New York, NY: Facts On File, c2007. (DR) PS153.N5 E48 2007

Encyclopedia of African American Women Writers. Edited by Yolanda Williams Page. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2007. (F) PS153.N5 E49 2007

Encyclopedia of Hip Hop Literature. Edited by Tarshia L. Stanley. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2009. (F) PS153.N5 E53 2009

Encyclopedia of the Harlem literary renaissance, by Lois Brown. New York NY: Facts On File, Inc., c2006. (F) PS153.N5 B675 2006

The Greenwood Encyclopedia of African American Literature. Edited by Hans Ostrom and J. David Macey, Jr. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2005. (F) PS153.N5 G73 2005

Masterpieces of African-American Literature. Edited by Frank N. Magill. 1 st ed. New York, NY: HarperCollins, c1992. (F) PS153.N5 M264 1992

Black American Poets and Dramatists of the Harlem Rena issance. Edited and with an introduction by Harold Bloom. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, c1995. (F) PS153.N5 B5335 1995

The Cambridge Companion to the Harlem Renaissance . Edited by George Hutchinson. New York:Cambridge University Press, 2007. (F) PS153.N5 C345 2007

The Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature. Editors, William L. Andrews, Frances Smith Foster, Trudier Harris. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. (F) PS153.N5 C59 2001

Encyclopedia of African-American Literature . New York, NY: Facts On File, c2007. (DR) PS153.N5 E48 2007

The Harlem Renaissance: A Gale Critical Companion . Foreword by Trudier Harris-Lopez; Janet Witalec, project editor. Detroit: Gale, c2003. 3 vols. (F) PS153.N5 H245 2003

The Harlem Renaissance: An Annotated Bibliography and Commentary , by Margaret Perry. New York: Garland Pub., 1982. (DR) Z5956.A47 P47

The Harlem Renaissance: An Annotated Reference Guide for Student Resea rch, by Marie E. Rodgers. Englewood, Colo.: Libraries Unlimited, 1998. (F) Z5956.A47 R64 1998

Within the Circle: An Anthology of African American Literary Criticism from the Harlem Renaissance to the Present . Edited by Angelyn Mitchell. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 1994. (F) PS153.N5 W58 1994

The Papers of Amiri Baraka, Poet Laureate of the Black Power Movement

This collection of Amiri Baraka materials was made available by Dr. Komozi Woodard. Dr. Woodard collected these documents during his career as an activist in Newark, New Jersey.The collection consists of rare works of poetry, organizational records, print publications, over one hundred articles, poems, plays, and speeches by Baraka, a small amount of personal correspondence, and oral histories. The collection has been arranged into eighteen series. These series are: (1) Black Arts Movement; (2) Black Nationalism; (3) Correspondence; (4) Newark (New Jersey); (5) Congress of African People; (6) National Black Conferences and National Black Assembly; (7) Black Women’s United Front; (8) Student Organization for Black Unity; (9) African Liberation Support Committee; (10) Revolutionary Communist League; (11) African Socialism; (12) Black Marxists; (13) National Black United Front; (14) Miscellaneous Materials, 1978-1988; (15) Serial Publications; (16) Oral Histories; (17) Woodard’s Office Files.

Zora Neale Hurston Plays at the Library of Congress

"This collection present ten plays written by Hurston (1891-1960), author, anthropologist, and folklorist. Deposited as unpublished typescripts in the United States Copyright Office between 1925 and 1944, most of the plays remained unpublished and unproduced until a manuscript curator rediscovered them in the Copyright Deposit Drama Collection in 1997. The plays reflect Hurston's life experience, travels, and research, especially her knowledge of folklore in the African-American South. Totaling 1,068 images, most of the scripts are housed in the Library's Manuscript Division with one each in the Music and in the Rare Book and Special Collections Divisions. There are four sketches and six full length plays in this group. Previously known mainly for her fiction and autobiography, Hurston here reveals her high ambitions as a dramatist."

- Anthologies of African American Writing This bibliography seeks to provide a comprehensive enumeration of anthologies of African American writings from the first such works up to the present

- << Previous: LGBT

- Next: Microfilm Collections >>

- Last Updated: Jan 5, 2024 12:02 PM

- URL: https://libguides.princeton.edu/aas

- Find a Database

- How to Connect

- Report a Problem

- DELCAT Online Catalog

- Digital Collections Home

- UDSpace Institutional Repository

- Finding Aids

- Online Exhibitions

- Propose a Digitization Project

- Copyright Policies

- Contact Information

- Location and Hours

- Film and Video Home

- Browse Collections

- Search for Media

- New Acquisitions

- Video Games

- Circulation and Scheduling

- Streaming Media

- Instructional Support

- Media and Copyright

- Collection Development

- Scheduling Request Form

- Ask Film and Video

- Journal Article Search

- Journal Browse

- Research Guides

- Special Collections

- Borrow and Renew Home

- UD Library Self-Checkout

- My Library Account Information

- My Library Account Support

- Telephone Renewal

- All Circulation Forms

- Book Holds Service Form

- In-Process Material Request

- Library Annex Request Form

- Obtaining a Locker

- Report a Missing Book

- Authorized Borrower Card Application for Faculty

- Faculty Research Studies

- Library Retired Faculty Room

- Graduate Student Carrels

- Loan Periods

- Public Borrower Information

- Reciprocal Borrowing Programs

- Staff Directory

- Ask Help Center

- All Equipment and Technology

- Video Cameras

- Digital Still Cameras

- Camera Accessories

- Laptops, iPads and Drives

- Audio Equipment

- Headphones and Other

- Equipment Borrowing Policies

- Course Reserves Home

- For Faculty

- For Students

- Digital Initiatives Home

- About Digital Initiatives

- Request a Workshop

- Interlibrary Loan Home

- Getting Started

- Article DELivery Service

- Associate in Arts Program Delivery

- Distance Learning DELivery Service

- HathiTrust Accessible Text Request Service

- Office Delivery

- Lending to Delaware Libraries

- Lending to Other Libraries

- Registration for University of Delaware ILL Lending

- Our Policies and Procedures

- Cancelled Requests

- Teaching and Learning Home

- Request for Teaching Collaboration

- Teaching and Learning Support

- Research Skills

- Primary Sources

- Data Literacy

- Publishing and Sharing Work

- English 110 Resources

- All Tutorials

- Off-Campus Access

- Case Study: Undergraduates Engage with History

- Case Study: Multimedia Instruction

- Case Study: Using Library Resources to Perform Industry Research

- Teaching and Learning Directory

- Open Education Resources

- Print, Copy and Scan

- Reference Services Home

- Evaluating and Citing Sources

- Learning More

- Digital Initiatives

- Teaching and Learning Services

- Video Tutorials

- Subject Specialists

- Ask Reference

- Recommend for Library Purchase

- Research Data Services Home

- Data Management Resources

- NIH Data Management and Sharing Plan

- Reserve Spaces, Lockers, Carrels

- Visiting Information

- Locations and Hours

- Library Floor Plan Maps

- Driving Directions

- Shuttle Bus Routes

- Upcoming Events and Workshops

- Past Events

- Scholar in the Library

- Branch Libraries Home

- ERC Community Norms

- ERC Advisory Board

- Find ERC Materials

- Testing Materials

- Reserve SMARTBoard Room

- Our Collection

- Museums and Galleries Home

- Exhibitions

- Class Visits and Tours

- Museum Galleries

- Digital Collections

- Access to Primary Resources

- Awards and Funding Opportunities

- Special Collections Policies and Procedures

- Copyright Restrictions

- Reproducing Materials

- Contact Museums

- Contact Special Collections

- Our Spaces Home

- Directions and Maps

- Find My Event

- Reserve a Seat

- Inclusive Spaces

- Study Spaces

- Make and Create Spaces

- Learn and Connect Spaces

- Special Collections Home

- Multimedia Tips and Tricks

- All Equipment Kits

- Reservations

- Digital Mapping

- UD ONEcard and Flex

- Large-Format Printing

- All Software

- Audio Software

- Graphics Software

- Text Software

- Video Software

- Audio Spaces

- Graphics Spaces

- Video Spaces

- Other Spaces

- General Policies

- Circulation Policies

- Reservation Policies

- Writing Center

- About Library, Museums and Press

- Open Access

- Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

- Employment Information

- Student Employment Information

- Library Rank and Promotion System

- Mellon Poetry as Activism

- Pauline A. Young Residency

- UDLib/SEARCH

- All Library Policies

- Community Norms

- Confidentiality of Library Records

- Copyright and Database License Restrictions

- Gifts of Materials and Objects

- Library Bill of Rights, Freedom to Read, and Code of Ethics

- Group Study Room Policies

- Retired Faculty Room Policies

- Room Reservations for Non-Library Events

- Collection Development Policy

- Course Reserve Services and Policies

- Digital Collections Copyright Policies

- Film and Video Collection Policies

- Institutional Repository Policies

- Interlibrary Loan Policies

- Special Collections Policies

- Student Multimedia Design Center Policies

- Textbook Policy

- Library, Museums and Press News

- Sign up for Mailing List

- Impact Report

- Strategic Directions Home

- Student Success and Learning

- Research, Scholarship and Discovery

- Partnerships and Collaboration

- Ask the Library Chat/Email

- Disability Assistance

- General Information

- OpenAthens Bookmarklet

- OpenAthens FAQs

- My Library Account (DELCAT)

- My Interlibrary Loan Account

- Staff Intranet Login

- Morris Library 8am–11pm

- View All Hours

- Making a Gift

- Faculty Lecture

- Annual Dinner

- Book Collecting Contest

- Research Award

- Call (302) 831-2965

- Live Chat Daily

- Text (302) 360-8747

- All Contact Info

- Organization Chart

Black Studies Center

Black Studies Center brings together essential historical and current material for researching the past, present and future of African Americans, the wider African Diaspora, and Africa itself. It is comprised of several cross-searchable component databases:

- Schomburg Studies on the Black Experience This unique database examines interdisciplinary topics on the African experience throughout the Americas via in-depth essays accompanied by detailed timelines along with important research articles, images, film clips and more. The essays are contributed by leading academic experts who have surveyed and analysed the most important existing research literature in their respective fields.

- Black Studies Center Periodicals The Black Studies Periodicals Database , formerly known as International Index to Black Periodicals (IIBP) Full Text, includes current and retrospective bibliographic citations and abstracts from scholarly journals and newsletters from the United States, Africa and the Caribbean — and full-text coverage of core Black Studies periodicals.

- The Chicago Defender BSC provides the full-text backfile, from 1910 to 1975, of the influential black newspaper The Chicago Defender . Robert Sengstacke Abbott founded the Defender in May 1905 and by the outbreak of the First World War it had become the most widely read black newspaper in the country, with more than two thirds of its readership based outside Chicago. When Abbott died in 1940, his nephew John Sengstacke became editor and publisher of the Defender, which began publishing on a daily basis in 1956.

- ProQuest Dissertations for Black Studies The ProQuest Dissertations for Black Studies module contains a thousand doctoral dissertations and Masters’ theses examining a wide variety of topics and subject areas relating to Black Studies. Included are dissertations written between 1970 and 2004 at over 100 universities and colleges across the United States. These dissertations were selected for their relevance to Black Studies scholars from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global .

- Black Literature Index Black Studies Center includes the electronic index to the Black Literature microfiche collection. This index allows users to search over 70,000 bibliographic citations for fiction, poetry and literary reviews published in 110 black periodicals and newspapers between 1827-1940. For citations to content from the Chicago Defender for which full text is available in Black Studies Center , a link is included directly to the relevant article.

Related Research Guides

African American History African American Studies English and American Literature History

- Interlibrary Loan

- Electronic Journals

- Reserve a Space

- Events and Workshops

Sign Up for the Latest News and Events

- Quarterly newsletter

- Monthly events roundup

- Additional news and updates

Mission Statement

Founded in 2002, the mission of the Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College of the City University of New York (CBL) is to expand, broaden, and enrich the public’s knowledge and appreciation of Black literature by people of the African Diaspora and of the African continent. The Center builds an audience for the reading, discussion, research, study, and critical analysis of Black literature through a variety of programs and partnerships. CBL was also established to institutionalize the National Black Writers Conference (NBWC), founded by John Oliver Killens in 1986 at Medgar Evers College, CUNY.

To achieve its mission, CBL offers literary programs and educational workshops for the public, students of all ages, teachers, writers, and artists. Among its core programs are the National Black Writers Conference, Re-Envisioning Our Lives through Literature (ROLL), the Wild Seeds Retreat for Writers of Color, the Dr. Edith Rock Writing Workshop for Elders, the John Oliver Killens Reading Series, and the weekly Writers on Writing Radio Program. The Center also publishes the peer-reviewed Killens Review of Arts & Letters , and other journals generated from its youth and elders programs.

For 20 years, the public and academic programs of the Center have been highly revered and have had a dynamic impact in the literary field. The author readings and book signings, journals, symposia, conferences, panel discussions, and writing workshops—and the Center’s intellectual and accessible approach to programming—form an integrative approach that sets CBL apart from others. CBL’s body of work is known for the way in which it ensures that Black literary scholarship and conversations are valued and sustained.

Through its collaborations with public schools and organizations such as the Brooklyn Public Library, the Brooklyn Museum, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Brooklyn Literary Council, and the PEN America, the Center for Black Literature serves as a vehicle for nurturing and cultivating the critical reading and writing habits of a cross-generation of readers and writers and provides university, community and public institutions with various literary programs. Funding and support for Center programs have been provided by the public and private sector and include organizations such as the National Endowment for the Arts, the Nathan Cummings Foundation, Humanities New York, Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, the New-York Historical Society, Poets & Writers, and the Brooklyn Community Foundation, as well as support from local and state elected officials.

Housed in Medgar Evers College’s School of Professional and Community Development, the Center collaborates with educational, literary, cultural arts, and media organizations—both locally and nationally. It partners with Medgar Evers College, the City University of New York, local high schools, as well as with the Center for Law and Social Justice, PEN America, the Brooklyn Literary Council, the Brooklyn Public Library, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, RestorationART at Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, and many other entities.

Dr. Brenda M. Greene is the founder and executive director of the Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College, CUNY.

Center for Black Literature (CBL) at Medgar Evers College, CUNY 1534 Bedford Avenue | 2nd Floor Brooklyn, New York 11216 (Click HERE for the Postal Mailing Address)

Main Phone: (718) 804-8884 Main Office: [email protected]

Donate to CBL Today!

To carry out our literary programs and special events, we depend on financial support from the public. Donations are welcome year-round. Please click HERE to donate. Thank you! ... The Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College is supported in part by an American Rescue Plan Act grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to support general operating expenses in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

We're Where You Are!

Get the latest news.

Sign-up to receive news about our programs!

Copyright © 2023, Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College.

Join Discovery, the new community for book lovers

Trust book recommendations from real people, not robots 🤓

Blog – Posted on Tuesday, Aug 18

Guide to african american literature: 30 must-read books from the past century.

African American literature is the corpus of fictional, dramatic, and poetic works produced by American writers of African descent. To most readers, it’s associated with the boldly experimental output of the Harlem Renaissance — the jazz-inflected, Manhattan-centered artistic movement in the early 20th century that saw Black authors like Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes win mainstream acclaim.

As groundbreaking as the Harlem Renaissance was, though, African American literature goes far beyond this one watershed moment. The Black literary tradition in the US has deep historical roots, extending well into the antebellum period. Its early works include verse written by enslaved poets from the colonial era, as well as autobiographical “ slave narratives ” recounting the experiences of people under bondage. And of course, the history of African American literature is still actively being written: in the past few years, Black American writers have conducted fascinating experiments with form, turned YA books into engines of social change, and transformed the landscape of speculative fiction.

Want to dive into this rich literary tradition? In this post, we’ll take you through 30 essential works from the past hundred years, from classic novels ripe for rediscovery to contemporary collections on the cutting edge of literary fiction. The books we’ve selected don’t just represent the finest work by African American writers — each of them engages deeply with aspects of the Black American experience, from the institutional shadows cast by slavery to the failures of a criminal justice system that discriminates based on race.

These books aren’t primary sources, artifacts framing historical trauma for a reader’s edification. They’re works of art. Taken together, they experiment boldly with literary convention and treat challenging material with grace and poignancy — not to mention irony and wit. Learn from them, but be sure to enjoy them as well, luxuriating in their elegant language, daring structure, and evocative characterization.

Without further ado, check out these 30 must-read African American literature books .

1. Cane by Jean Toomer (1923)

The versatile, lyrical writer Jean Toomer produced only one novel during his long and varied career, which ranged from poetry to essays about his Quaker faith. Cane, hailed as an “astonishingly brilliant” debut, shows off his range by mixing prose, verse, and drama to tell the intertwining stories of Black women grappling with the industrialization of the South. The result — now hailed as a modernist classic — reads less like a conventional novel than an operatic cycle, more concerned with the music of language than the intricacies of plot.

2. Quicksand by Nella Larsen (1928)

Born to a Black father who left and a Danish mother who died Helga Crane has always felt alone. Whether she’s in Copenhagen or the American South, teaching at an all-Black boarding school or listening to a white preacher’s sermon, she’s never quite found a place where she belonged. In Quicksand , Harlem Renaissance writer Nella Larsen — herself the daughter of a Danish woman and Afro-Caribbean man — mines personal experience to craft an intimate portrait of Black biracial womanhood in the 1920s.

3. Plum Bun by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1929)

Another masterpiece from an oft-neglected Harlem Renaissance great, Plum Bun is subtitled “A Novel Without a Moral”. As a young, African-American woman growing up in Philadelphia, Angela Murray realizes she can pass for white. Heartbroken by her parents’ death and sickened by the racism she’s suffered in Philly, Angela decides to seek a life free from prejudice. Soon enough, she’s moved to New York and is masquerading as a white woman among the city’s avant-garde. But Angela’s new freedom comes at a cost: she’s had to leave her dark-skinned sister, Virginia, behind.

4. Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston (1937)

Rarely does a book speak so broadly across cultural circumstances, and yet so personally to each reader who finds it. Hurston’s masterpiece, Their Eyes Were Watching God , is one such book — it has simultaneously found a home in the ranks of American classics, feminist classics, and African American literary classics (specifically, from the height of the Harlem Renaissance). Following the life of Janie Crawford from ingenue to independent woman, this wildly influential book has come to touch many lives.

5. Native Son by Richard Wright (1940)

Pre-dating the Black Lives Matter movement by around eighty years, Native Son is nonetheless an important key to understanding the systemic impact that racism has on Black lives. Set in the impoverished regions of 1930s Chicago, this novel follows Bigger Thomas, an underprivileged young man who falls into a life of crime. While the book does not condone Bigger’s actions, it does provide an important and sympathetic look at how poor Black youth, in particular, are shaped by their material circumstances.

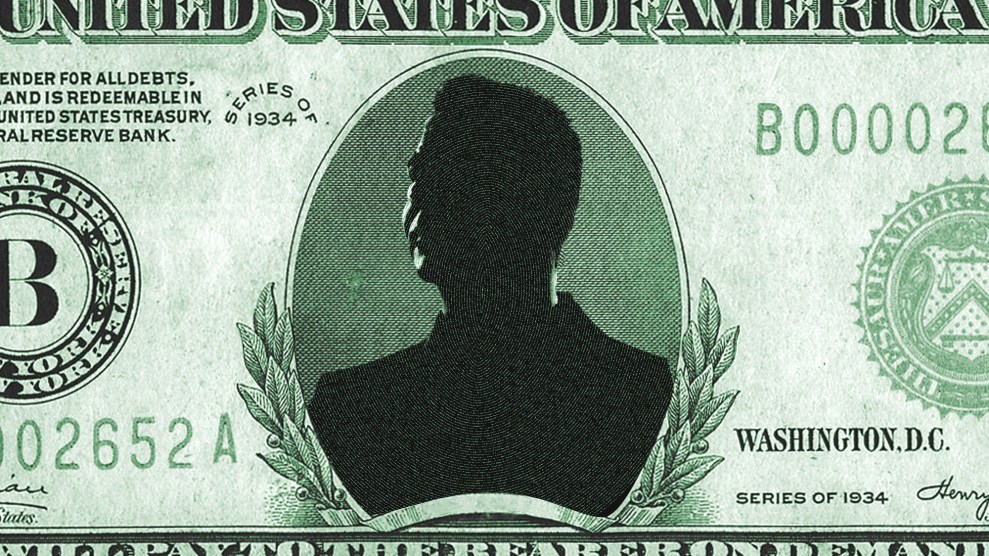

6. Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (1952)

What does it mean to be invisible? In this breathtakingly experimental novel, Ellison explores the concept through an aptly unnamed narrator. Following the protagonist from his high school years through his time as the spokesman for “the Brotherhood,” and finally to his retreat from all of society, Invisible Man is a thoughtful and brutally honest novel that will make you look at society with fresh eyes — hopefully, eyes more attuned to seeing those who would otherwise go unnoticed.

7. Go Tell It On The Mountain by James Baldwin (1953)

Baldwin’s semi-autobiographical novel tells the story of John Grimes, a teenager in 1930s Harlem. Written in lyrical prose best described as Biblical poetry, it’s only fitting that this book deals heavily with Grimes’s (and, by extension, Baldwin’s) ever-shifting relationship with his faith. As the stepson of minister and a boy discovering his own homosexuality, the character definitely has a lot to process. Go Tell It on The Mountain takes us expertly through all the feelings that follow, in a way that will resonate with readers regardless of their faith or identity.

8. The Narrows by Ann Petry (1953)

Named for the African-American neighborhood in a segregated Connecticut town, The Narrows kicks off with a young white woman being sexually harassed. A twenty-something Black man named Link Williams comes to her rescue, and soon enough, the two are entangled in a passionate affair. But Link’s new beloved isn’t who she says she is — in fact, she’s the wife of one of the wealthiest white men in town.

9. Babel-17 by Samuel R. Delaney (1967)

Instead of the oft-used physics of starflight or the biology of cloning, this foundational text in African-American sci-fi takes inspiration from the science of linguistics. In fact, Babel-17 is named for the language at the center of the book: a strange, pronoun-free tongue weaponized by one side in a far-future war. If you fight for the opposite forces, learning Babel-17 will change your very worldview — turning you into a traitor in the process.

10. Roots: The Saga of an American Family by Alex Haley (1976)

You may be familiar with this story through the historic 1977 miniseries or the more recent History Channel adaptation, but Roots: The Saga of An American Family was a book before it ever reached viewers on TV. Based directly off the author’s own lineage, it’s easy to see why this powerful novel has been adapted and retold time and time again. Sprawling across multiple generations, Roots is a must-read in the current era, and no doubt will remain one for many years to come.

11. Kindred by Octavia E. Butler (1979)

Octavia Butler's iconic novel is not only a staple of African American literature, but a sci-fi classic in its own right. Dazzling, heartbreaking, and all too relatable, it tells the story of Dana, a writer who ends up jumping through time between her life in 1976 California, and a pre-Civil War Maryland plantation. What follows is the haunting story of a woman literally trying to navigate two worlds, while being fully aware of the far-reaching legacy of the antebellum South she finds herself in.

12. The Color Purple by Alice Walker (1982)

In this epistolary novel, we meet Cecile and Nettie — sisters living under the so-called “care” of an abusive father. Cecile starts writing letters to God to deal with her horrific situation, and the novel grows from there. We’ll be honest, this is not always an easy read to get through, as Walker pulls no punches when it comes to showing the world the truth of domestic and sexual abuse. Still, there’s a reason this novel won the Pulitzer prize (and, in the process, made Walker the first Black woman to receive that honor).

13. The Women of Brewster Place by Gloria Naylor (1982)

Gloria Naylor won the National Book Award for this keenly observed debut novel. The Women of Brewster Place tells the story of seven Black women living in poverty, inside a rundown building that’s embattled by city politics and perpetually threatening to fall apart. Thanks to Naylor’s vivid, unsentimental prose and exacting eye for detail, every character comes to life with all the warmth of flesh and blood.

14. Beloved by Toni Morrison (1987)

Inspired by the real-life story of a formerly enslaved woman, this Pulitzer prize-winning classic has been a staple of African American literature since it was first published. Following the life of Sethe, a woman who escaped enslavement eighteen years earlier, Beloved is a powerful examination of motherhood, humanity, and the horrors that follow when that humanity is stripped away from people. Be aware that this book does contain unflinching and graphic depictions of abuse. Still, Beloved is a piece of history that shouldn’t be glossed over, and it handles this difficult subject matter with expert care.

15. Corregidora by Gayl Jones (1987)

According to a feature in The Atlantic , Gayl Jones is the “ Best American Novelist Whose Name You May Not Know ”. Her contemporaries, among them Toni Morrison and John Updike, praised her haunting depictions of slavery’s enduring psychological consequences. If you’d like to read this neglected genius for yourself, start with Corregidora , her stylish and ambitious magnum opus. This challenging novel centers on Ursa Corregidora, a blues singer whose enslaved great-grandmother was raped by a Portuguese slaveholder — the man who gave Ursa his surname and whose legacy continues to haunt her generations later.

16. Devil in a Blue Dress by Walter Mosley (1990)

The first book of the Easy Rawlins mystery series, Devil in a Blue Dress introduces us to Easy, a recently fired war vet now nursing his troubles at a friend’s bar. When a man who walks in tasks him with the job of finding a blonde bombshell known to frequent Black jazz clubs, Easy’s life takes another turn. A thrilling PI story in its own right, this book has also made solid contributions to the canon of African American-penned mystery novels, bringing an authentic voice and unique characterizations.

Those Bones Are Not My Child: A Novel (Vintage Contemporaries) by Toni Cade Bambara

Edited by Toni Morrison, this searing, nearly 700-page novel was published posthumously. Those Bones Are Not My Child starts off in the summer of 1980, when Atlantan mother Zala Spencer finds her tween son missing. Twelve-year-old Sonny, as Zala and her husband Nathaniel quickly find, isn’t the only Black child to disappear in recent times — but the city doesn’t seem to care. Brushed off by the authorities, the Spencers find themselves with no choice but to search for their son on their own.

18. Tumbling by Diane McKinney-Whetstone (1996)

This stylistically dazzling debut cemented Diane McKinney-Whetstone’s place among the finest fiction writers of her generation. In Tumbling , we’re introduced to Noon and Herbie, a preacher’s daughter and a former jazz musician who met and married in 1940s Philadelphia. But even though they love each other and they’ve been together for years, their relationship remains unconsummated: Noon, the survivor of a childhood assault, is still traumatized by the idea of sex. Still, the two remain devoted to each other. Then Herbie’s mistress, Ethel, starts leaving children on their doorstep, shaking up the delicate equilibrium in their marriage.

19. The Known World by Edward P. Jones (2004)

This daring and sophisticated historical fiction novel won Edward P. Jones the Pulitzer Prize. In antebellum Virginia, freedman Henry Townsend finds himself mentored by his own slaveholder, the most powerful landowner in Manchester County. Through William Robbins’s support, Henry becomes the owner of a sprawling estate — fifty acres worked by 33 slaves of his own. Narrated by an omniscient observer who never voices judgment, The Known World isn’t an easy read. But it does offer a searing meditation on power, complicity, and the impossibility of honor under an evil and all-reaching institution.

20. Monster by Walter Dean Myers (1999)

This wildly experimental novel is an emotional rollercoaster in all the best ways. Following the life of 16-year-old Steve Harmon, Monster opens with his diary entries as he awaits trial for murder. When Steve decides that his life story would make a good movie, the novel transitions into a mix of diary entries and screenplay pages, an eclectic narrative that somehow only manages to strengthen the story’s themes of racial identity, peer pressure, and the nature of truth. Monster is an experience not to be missed, with a narrator that readers won’t soon forget.

21. The Twelve Tribes of Hattie by Ayana Mathis (2012)

The gorgeous and harrowing debut will linger in your mind long after you absorb the final sentence. It’s 1923, and Hattie Shepherd has just left Georgia for Pennsylvania. She, along with her mother and sisters, are among the six million African Americans to participate in the Great Migration, which saw them leave their rural Southern hometowns for cities to the north and west. By seventeen, Hattie is married to a man who gives her many children, but little love. The Twelve Tribes of Hattie is a devastating family saga that centers on the unbreakable spirit of its title character through her evolution from hopeful teen to matriarch.

22. Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson (2014)

In this autobiographical novel-in-verse, Woodson brings readers deep into her life and heart. Tracking her experiences from her early years in rural Ohio, to her adolescence in Georgia, and finally up to her years in New York, Brown Girl Dreaming serenades readers with the beauty of Woodson’s life, even when it delves into the depths of racism and the Civil Rights movement. This book is truly a dream — a testament to the human spirit.

23. Fire Shut Up in My Bones by Charles M. Blow (2014)

In Fire Shut Up in My Bones , hailed by the A.V. Club as the “ memoir of the year ,” New York Times journalist Charles M. Blow recounts his experience as a bisexual, Black survivor of sexual abuse. But this book doesn’t just tell Blow’s story — it starts with his mother, who grew up in a segregated southern town, and whose unbending sense of honor shaped her son. Whether he’s reconstructing his mother’s experience or excavating his own, Blow writes with unflinching exactitude and poise.

24. The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin (2015)

Psychologist-turned-novelist N.K. Jemisin is arguably science fiction’s greatest living writer . The Fifth Season , which opens her magisterial Broken Earth trilogy, made her the first African American to win a Hugo Award for Best Novel. This elegant science fantasy takes place on a supercontinent called the Stillness, ironically wracked by devastating seismic activity. People with the ability to control and rechannel the ground’s tremors, known as orogenes, help keep the ground together. At the same time, their dangerous powers make them the target of hatred and fear.

25. The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead (2016)

While the real underground railroad had nothing to do with trains, this risky gateway to freedom is reimagined in Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad . Following two enslaved people named Cora and Caesar, this wildly imaginative novel takes readers on a journey along a literal railway beneath the soil of the Southern states. Featuring unusual — but familiar versions — of the world you know, this story will enchant just as much as it educates.

26. Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi (2016)

Homegoing is a story of legacies. It follows two sisters who have never met: Effia, who marries a British governor in charge of Cape Coast Castle, and Esi, held captive in the dungeons of the very same castle. Over the course of the novel, we witness the very divergent lives of not only the sisters themselves, but generations of their descendants. This ambitious novel spans decades and oceans, but never once loses the heart that binds it all together.

27. The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas (2017)

Born from the Black Lives Matter movement, The Hate U Give tells the all-too-recognizable story of Starr, a young woman who sees her best friend being shot by the police. Now Starr has to bear witness firsthand as he becomes a national headline. Stuck in the middle of the public discourse, she faces a difficult choice. Should she use her voice and speak up for her friend and those like him, at the risk of being swept up in the same frenzy that stole his life? Or should she keep silent and live with the knowledge festering inside her?

28. Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward (2017)

Half ghost story and half travel narrative, Sing, Unburied, Sing follows Jojo, a boy on the cusp of manhood. Ward’s magnificent, lyrical writing brings this breathtaking story to life. After the events of his thirteenth birthday, Jojo is packed into the car with his family and taken on a journey to visit his long-absent white father upon his release from prison. Deeply emotional, this story of fathers, father-figures, and sons will haunt readers’ minds like the ghost that flits between the chapters.

29. An Unkindness of Ghosts by Rivers Solomon (2017)

Botanist Aster Gray lives aboard the HSS Matilda . She and her shipmates are the last remaining humans, and the generation ship that shelters them will bring them to the Promised Land. But life aboard Matilda is as cruel as the chill of space. Not only is the neurodivergent Aster derided as a “freak,” she and her fellow dark-skinned sharecroppers are trapped on the ship’s lower decks, brutalized by overseers from the world above. But then Matilda’s sovereign dies, and an autopsy reveals a surprising link to the suicide of Aster’s mother, a mystery from twenty-five years ago. This wildly original debut uses established sci-fi conceits to critique institutional racism.

30. A Lucky Man by Jamel Brinkley (2018)