- Getting Published

- Open Research

- Communicating Research

- Life in Research

- For Editors

- For Peer Reviewers

- Research Integrity

How to communicate your research more effectively

Author: guest contributor.

by Angie Voyles Askham, Content Marketing Intern

"Scientists need to excite the public about their work in part because the public is paying for it, and in part because science has very important things to say about some of the biggest problems society faces."

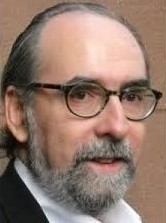

Stephen S. Hall has been reporting and writing about science for decades. For the past ten years, he's also been helping researchers at New York University improve their writing skills through the school's unique Science Communication Workshops . In our interview below, he explains why the public deserves good science communication and offers some tips for how researchers can make their writing clear and engaging.

How would you descr ibe your role as a science journalist?

I’ve always made a distinction between "science writer" and a writer who happens to be interested in science. That may sound like wordplay, but I think it captures what we aspire to do. Even as specialists, science journalists wear several hats: we explain, we report, we investigate, we step back and provide historical context to scientific developments to help people understand what’s new, why something is controversial, who drove a major innovation. And like any writer, we look for interesting, provocative, and deeply reported ways to tell these stories.

I know you from the science communication workshop that’s offered to NYU graduate students. One of the most important things that I got out of the workshop, at least initially, was training myself out of the stuffy academic voice that I think a lot researchers fall into when writing academic papers. Why do you think scientists fall into this particular trap, and how do you help them get out of it?

Scientists are trained—and rightly so—to describe their work in neutral, objective terms, qualifying all observations and openly acknowledging experimental limitations. Those qualities play very well in scientific papers and talks, but are terrible for effective communication to the general public. In our Science Communication workshops at NYU, we typically see that scientists tend to communicate in dense, formal and cautious language; they tell their audiences too much; they mimic the scientific literature’s affinity for passive voice; and they slip into jargon and what I call “jargonish,” defensive language. Over ten years of conducting workshops, we’ve learned to attack these problems on two fronts: pattern recognition (training people to recognize bad writing/speaking habits and fixing them) and psychological "deprogramming" (it’s okay to leave some details and qualifications out!). And a key ingredient to successful communication is understanding your audience; there is no such thing as the "general public," but rather a bunch of different potential audiences, with different needs and different levels of expertise. We try to educate scientists to recognize the exact audience they're trying to reach—what they need to know and, just as important, what they don't need to know.

What are some other common mistakes that you see researchers making when they’re trying to communicate about their work, either with each other or with the public?

We see the same tendencies over and over again: vocabulary (not simply jargon, but common expressions—such as gene “expression”—that are second-hand within a field, but not clear to non-experts); abstract, complicated explanations rather than using everyday language; sentences that are too long; and “optics” (paragraphs that are too long and appear monolithic to readers). We’ve found that workshops are the perfect setting to play out the process of using everyday language to explain something without sacrificing scientific accuracy.

Why is it important for researchers to be better communicators?

Scientists need to learn to tell their own stories, first and foremost, because society needs their expertise, their perspective, their evidence-based problem solving skills for the future. But the lay public, especially in an era where every fact seems up for grabs, needs to be reminded of what the scientific method is: using critical thinking and rigorous analysis of facts to reach evidence-based conclusions. Scientists need to excite the public about their work in part because the public is paying for it, and in part because science has very important things to say about some of the biggest problems society faces—climate change, medical care, advanced technologies like artificial intelligence, among many other issues. As climate scientist Michael Mann said in a celebrated 2014 New York Times OpEd, scientists can no longer stay on the sidelines in these important public debates.

As a science journalist, part of your job is to hunt for interesting stories to tell. How can scientists make their work more accessible to people like you—or to other people outside of their specific area of research—so that their stories are told more widely?

The key word in your question is “stories.” Think like a writer. What’s the story behind your discovery? What were the ups and downs on the way to the finding? Where does this fit into a larger history of science narrative? Was there a funny incident or episode in the work (humor is a great way to draw and sustain public interest)? Was there a conflict or competition that makes the work even more interesting? Is there a compelling historical or contemporary figure involved that will help you humanize the science? It's been our-longstanding belief that scientists have a great intuitive feel for good storytelling (we incorporate narrative training in our workshops), but just don’t think about it when it comes to describing their own work. The other key thing is to explain why your research matters.

One of the ways that many researchers try to share their work is through Twitter, but I noticed that on the NYU website it says you’re a Twitter conscientious objector. Why is that? What effect do you think Twitter has had on science communication and journalism in general?

I actually think Twitter can be a great tool for science communication, and many of my colleagues use it deftly. I tend to gravitate toward stories that everyone is not talking about, so Twitter doesn’t help much in that regard. The larger reason I’m a Twitter “refusenik,” as my colleague Dan Fagin sometimes calls me, is that I think the technology has been widely abused to disseminate misinformation, intimidate enemies, and subvert democratic norms; I don’t use it primarily for those reasons.

Are there any other tips that you can offer researchers who want to be better communicators and just aren’t sure where to start?

One first step might be to see if your institution offers any communication training and to take advantage of those programs; if not, think about how you might establish a program. We’ve posted a few of the things we’ve learned at NYU on our website ; we’ve also established a publishing platform for science communicators at NYU called the Cooper Square Review , which is a good way for scientists to get experience publishing their own work and reaching a larger public.

Stephen S. Hall has been reporting and writing about science for nearly 30 years. In addition to numerous cover stories in the New York Times Magazine, where he also served as a Story Editor and Contributing Writer, his work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, and a number of other outlets. He is also the author of six non-fiction books about contemporary science. In addition to teaching the Science Communication Workshops at NYU, he also teaches for NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and has taught graduate seminars in science writing and explanatory journalism at Columbia University.

Click here to learn how Springer Nature continues to support the needs of Early Career Researchers.

Guest Contributors include Springer Nature staff and authors, industry experts, society partners, and many others. If you are interested in being a Guest Contributor, please contact us via email: [email protected] .

- early career researchers

- research communication

- Tools & Services

- Account Development

- Sales and account contacts

- Professional

- Press office

- Locations & Contact

We are a world leading research, educational and professional publisher. Visit our main website for more information.

- © 2024 Springer Nature

- General terms and conditions

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Your Privacy Choices / Manage Cookies

- Accessibility

- Legal notice

- Help us to improve this site, send feedback.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 26 April 2024

A guide to science communication training for doctoral students

- Christina Maher 1 na1 ,

- Trevonn Gyles ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4635-5985 1 na1 ,

- Eric J. Nestler ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7905-2000 1 , 2 &

- Daniela Schiller ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0357-7724 1 , 2

Nature Neuroscience ( 2024 ) Cite this article

908 Accesses

70 Altmetric

Metrics details

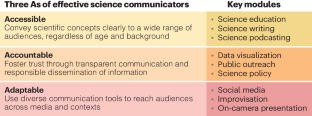

Effective science communication is necessary for engaging the public in scientific discourse and ensuring equitable access to knowledge. Training doctoral students in science communication will instill principles of accessibility, accountability, and adaptability in the next generation of scientific leaders, who are poised to expand science’s reach, generate public support for research funding, and counter misinformation. To this aim, we provide a guide for implementing formal science communication training for doctoral students.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Steinbeck, J. The Log From the Sea of Cortez (Penguin, 2001).

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. UNESCO Science Report 2021: the Race Against Time for Smarter Development (United Nations, 2021).

Croxson, P. L., Neeley, L. & Schiller, D. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 , 1466–1468 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Rein, B. Cell 185 , 3059–3065 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Weingart, P. & Guenther, L. J. Sci. Commun. 15 , C01 (2016).

Article Google Scholar

Fischhoff, B. & Scheufele, D. A. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110 , 14031–14032 (2013). (Suppl. 3).

Grorud-Colvert, K., Lester, S. E., Airamé, S., Neeley, E. & Gaines, S. D. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107 , 18306–18311 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Ending Discrimination Against People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders: the Evidence for Stigma Change (National Academies Press, 2016).

Neeley, L. et al. Front. Commun. 5 , 35 (2020).

Goldstein, C. M., Murray, E. J., Beard, J., Schnoes, A. M. & Wang, M. L. Ann. Behav. Med. 54 , 985–990 (2020).

Gascoigne, T. et al. (eds.) Communicating Science: A Global Perspective (ANU Press, 2020).

Rein, B. Neuroscience 530 , 192–200 (2023).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank P. Croxson for her involvement as co-founder of the effective science communication course. We also thank the various teaching assistants over the years, who were actively involved in shaping the course: T. Fehr, C. Lardner, C. Guevara and M. O’Brien.

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Christina Maher, Trevonn Gyles.

Authors and Affiliations

Nash Family Department of Neuroscience, Friedman Brain Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA

Christina Maher, Trevonn Gyles, Eric J. Nestler & Daniela Schiller

Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA

Eric J. Nestler & Daniela Schiller

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniela Schiller .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Maher, C., Gyles, T., Nestler, E.J. et al. A guide to science communication training for doctoral students. Nat Neurosci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01646-y

Download citation

Published : 26 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01646-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Improving Communication in Clinical Research

By: Anatoly Gorkun, MD, PhD, Chartered MCIPD Senior Manager, Global Clinical Development, PPD UK

Abstract: Effective communication skills in clinical research are vitally important. Due to many conflicting priorities however, clinical research professionals may not have time to manage soft skills. This increases the danger that something may go wrong. This article highlights real-life clinical research examples where communication problems affected deliverables or compliance. The principles of effective communication styles are discussed.

Introduction

Communication is a key tool for clinical researchers, yet problems due to inactive communication are common. It is important to monitor possible ineffective communication in order to develop effective solutions to proactively prevent the negative consequences of ineffective communication.

Some time ago, the author received feedback from two clinical trial managers (CTM) on the same clinical research associate (CRA) at the same time. One clinical trial manager said:

(CTM’s Name) “is perfectly performing as expected from an experienced CRA. Her time has been allocated to manage a few difficult sites. Due to her learning agility and deep experience, the situation is improving now. She is a very good team player.”

The other clinical trial manager told the author:

“I know this CRA is new to the company and is still learning; however, with the upcoming data cleaning, I need your help.

I would suggest she has a co-monitoring visit with someone who is experienced. She needs to understand that this reconciliation is not just making a match between source data vs. case report form but also questioning what is being reported and identifying gaps, and being able to address issues with the site staff.

I would appreciate your feedback and actions.”

Both studies were relatively similar, and in this specific example, the problem appeared to be the communication between the CRA and CTM.

The Importance of Communication in Clinical Research

There are various definitions of communication, including:.

“The imparting or exchanging of information by speaking, writing, or using some other medium.” ( oxforddictionaries.com )

“Two-way process of reaching mutual understanding, in which participants not only exchange (encode-decode) information, news, ideas, and feelings but also create and share meaning.” (businessdictionary.com).

The second definition is broader and reflects the nature of communication more accurately.

Poor communication in clinical research has many negative effects (Table 1) including stress, possible conflicts between clinical research professionals, and a breakdown in relationships. Other negative effects of poor communication are unmet expectations (ineffectiveness), wasted time because work is inefficient and must be re-done, non-compliance, possible harm to subjects, and possible invalidation of data.

As an example: an in-house CRA approached the line manager and said, “I’ve done what the project team wanted, but when I finished the task they said it was not what they expected.” The line manager asked if the CRA had checked with the project team before starting the task to clarify what they wanted. She said, “No, because the task seemed very clear.”

Communication that is free of assumptions is one of the characteristics of ideal communication (Table 2). It is important to listen, ask questions to ensure understanding of the task, agree to what needs to be done, and confirm the agreement. Communication is a two-way process that requires mutual understanding.

Successful Communication Methods

The most suitable method of communication depends upon the situation and to some extent, the receiver’s preferences. For urgent situations, a telephone call is best, followed by an email to summarize the call. The communicator should not bombard the person with emails, because he/she does not know whether the person is receiving and reading the emails. In some situations, more than one communication method is appropriate, such as emailing instructions and then following up with a telephone call.

Sometimes it happens that the site monitor and the in-house CRA as well as the project assistant may ask the research nurse at the site the same question. This may not be the most efficient approach. Communication should be streamlined in order to prevent it from being chaotic.

The following email communication is between a clinical trial manager (CTM) and a CRA on an urgent issue that required immediate attention. A delay in resolving the issue might affect deliverables and the company’s image.

- CTM → CRA, February 21: Check if all Adverse Events were entered into eCRF. Urgent, due in 2 days. Table attached.

- CTM → CRA, February 24: “A kind reminder, please.”

- CTM → CRA, February 24: “Please send me your answers today.”

- CTM → CRA, February 28: “I need your answers, please.”

- CTM → CRA, March 01: “Client requested us to provide the answer. Please complete this task.”

- CTM → CRA, March 06: “I need your answers URGENTLY please.”

- CTM → CRA, March 06: “Please do it tomorrow and let me know.”

- CRA → CTM, March 06: “I would do, but I don’t know what to check.”

- CTM → CRA, March 06: “The table is attached.”

- CTM → CRA, March 08: “Any news from the sites?”

- CRA → CTM, March 08: “Hopefully tomorrow.”

The clinical trial manager sent the first email to the CRA on February 21st and did not receive a reply from the CRA until March 6 th , nearly two weeks later. When the CRA responded that she did not know what to check, the CTM simply forwarded the same attachment. The CTM should have picked up the telephone and talked to the CRA.

Ideal communication is transparent. Transparency is:

“the perceived quality of intentionally shared information from a sender”

(Schnackenberg AK, Tomlinson EC. (March 2014). “Organizational transparency: a new perspective on managing trust in organization-stakeholder relationships,” Journal of Management . 10.1177/0149206314525202).

Transparency makes it easy for others to understand what actions have been completed and which actions need to be taken. It implies openness and accountability.

In another case, a project manager sent the following message to a line manager:

“As you know [name of CRA2] replaced [name of CRA1] at the end of March.

Unfortunately, by that date, the site performance decreased with late queries and SDV (Source Data Verification) backlog due to pending monitoring visits.

Until today both sites still have not been visited and the plan is not available. I appreciate if you guarantee to have both sites visited by the end of April.”

The line manager spoke to the CRA, who said that the visits had been scheduled a long time ago. The project manager had been on holiday. When the project manager came back, he did not speak with the CRA about the status of the visits but instead escalated the issue.

Considerations in using appropriate communication include:

- The purpose of the specific communication

- How communicating will benefit the situation

- Whether something different can be done

- Whether alternative communication is necessary, and if so, the best method to use.

In the example, considering these four questions would have enabled the project manager to realize that talking directly to the CRA was the appropriate communication method for this situation.

In this case, the CRA needed advice from the CTM:

CRA: “I need to complete a number of overdue study-specific learning items on my LMS (Learning Management System) but I don’t have time. I am so busy.”

CTM: “Then, do it wisely.”

The advice was not clear. Communication must also be concise. It is necessary to be clear about the purpose/goal of the message, to stick to the point, and to be brief.

Ideal communication is timely. In determining the best time for the message, the communicator must consider whether to communicate now or later. In some cases, it is better to wait and to communicate one message with another. It may also be helpful to pre-prepare the receiver of the communication with a brief heads-up.

A CRA was having communication issues with two clinical research sites. At the same time, this CRA had to deliver a presentation at a departmental meeting and wanted feedback from the line manager. The line manager knew that the sites were struggling to work with this CRA because of his insufficient communication skills. The line manager decided to wait a couple of days to speak with the CRA about his presentation/communication skills and the issue with the sites at the same time, as that was a good chance to demonstrate the importance of expressing thoughts clearly and explicitly.

It is also important to acknowledge receipt of an email or other communication when we are not going to provide our answer immediately. For example:

“I’ve received your message. It will take me a week to collect the requested information. I’ll get back to you by …”

Ideal communication is diplomatic and constructive. It is okay to disagree with someone; however, communication should focus on a person’s opinion or approach and not insult the person. For example, instead of saying,

“I don’t agree with you …,” say something like, “May I suggest that we discuss more options …”

An in-house CRA sent the following email message to a research nurse:

“I sent you my request 2 weeks ago, and it’s complete silence from your side. I find it so frustrating because we need to close all queries by the end of this week.”

The research nurse said that she would not respond to requests like this. After coaching the in-house CRA on communication methods, there was a visible improvement noticed, and the relationship with the site improved.

It is always better to be constructive. Avoid being very direct or pushy, and suggest options instead of criticizing or expressing frustration.

Ideal communication must be culturally respectful since clinical research is conducted internationally. Culturally respectful communication helps to avoid misunderstanding, to establish rapport, to build better relationships, and to facilitate more efficient work. Even among English-speaking countries, words or phrases can have slightly different meanings. For example, in the United States, “I hear what you say” means that the communicator accepts the other person’s point of view. In the United Kingdom, it may rather mean “I am not keen on discussing it further as I am not in agreement with this.” Also, accepting country or region-specific accents should be a part of cultural respect.

Ideal communication is also fair.

The following communication happened between a site monitor and a line manager.

Site monitor to line manager:

“I’m very busy and working very hard, however, I do not get enough support from the in-house CRA.”

The monitor’s line manager to in-house CRA’s line manager:

“I think that the in-house CRA might provide better support to the site monitor. Could you please check on the issue with the CRA’s performance and fix it?”

It turned out that the in-house CRA was doing a good job; however, the problem was that the site monitor needed to provide an explanation regarding the backlog of work that was created and decided to blame the in-house CRA for lack of support. Communication should be fair and should not blame other people unfairly.

Ideal communication is open, honest, and logical.

The following examples highlight communication between a line manager and a direct report during two performance reviews and a 1:1 meeting.

Mid-year performance review meeting, Line Manager to a direct report:

“You are leading a very important project really well. It’s going to be a great year for you!”

Monthly one-to-one meetings throughout the year:

The project delivery was on time and good quality. Every month, the line manager confirmed that she was happy with all of the work and there was nothing to improve.

End-of-year performance review meeting, Line Manager to a direct report:

“You’ve been struggling to deliver the project and managing it below expectations.”

The end-of-year performance review feedback was not logical because the previous messages were all positive. Ideal communication should avoid misunderstanding, conflicts, and disappointment.

Ideal communication is well-structured and compelling. Communicators should try not to tell a long story that makes it difficult for the receiver to determine what the communicator needs. This is important in everyday life with everyone, including communication with senior leaders and clinical investigators, both of whom are usually very busy.

The “rhetorical kipper” from Gareth Bunn can be used to plan communication. Using this model, communication is designed from the “tail of the kipper” and delivered from the “head.” After presenting the topic, three ideas or points are presented, and then finally, the request is made or the main message is delivered. The author’s direct reports found it useful to apply the rhetorical kipper method. Proper communication should be positive, assertive, and inspirational.

Case Study on Different Feedback

The case study presented at the beginning of this article illustrated different feedback from two clinical trial managers on the same CRA. One clinical trials managers stated that:

[CRA’s Name] “is perfectly performing as expected from an experienced CRA.

She has been allocated to manage a few difficult sites. Due to her learning agility and deep experience, the situation is improving now. She is a very good team player.”

I would suggest that she has a co-monitoring visit with someone experienced. She needs to understand that this reconciliation is not just making a match between source data vs. case report form but also questioning what is being reported and identifying gaps, being able to address issues with the site staff.

I would appreciate reviewing your feedback and actions.”

The reason for the different feedback was not different complexity of the studies but that the clinical trial manager was micro-managing the CRA. She had a different management style than the CRA was used to. The first clinical trial manager delegated the tasks and trusted the CRA to complete them. The second clinical trial manager required daily reports from the CRA, assuming that if there was no daily report, it meant that the job was not done. She also had negative experiences working with a previous CRA and assumed that the new CRA would act in the same way.

Thus, the second clinical trial manager’s style was based more on assumptions. After a root cause analysis of the situation, the CRA learned how to recognize different working styles and started working with the second CTM more efficiently.

Many skills are required for appropriate and effective communication (Table 3), including listening and observing, planning, and dealing with difficult situations dearly and empathetically. Methods of ensuring that communication is appropriate and effective include awareness of communication issues (Table 4). If we face a communication issue, we should not assume that it will disappear by itself. A root cause analysis should be done to determine the cause of the issue, and then a plan should be developed to manage the problem. The plan should include feedback to ensure that the other person understands and accepts the plan. Line managers can arrange for soft skills coaching and training for people who need to improve their communication skills. If nothing else works, such issues can be escalated.

In clinical research, it is important to monitor possible ineffective communication approaches and to proactively develop effective solutions to prevent negative consequences.

The Effects of Poor Communication in Clinical Research

- Possible conflicts and breakdowns in relationships

- Unmet expectations (ineffectiveness)

- Waste of time (inefficiency)

- Non-compliance

- Possible harm to subjects

- Possible invalidation of data

Ideal Communication

- Assumption-free

- Proper methods utilized

- Transparent

- Appropriate

- Clear and concise

- Diplomatic and constructive

- Culturally respectful

- Open, honest, and logical

- Well-structured and compelling

- Proper communication style

Communication Skills

- Listening and observing

- Nonverbal communication (body language, facial countenance)

- Negotiations

- Dealing with difficult situations

- Friendliness

- Flexibility (open-mind)

- Giving and receiving feedback

Communication Strategies to Prevent or Fix Issues

- Be aware of communication issues

- Observe and discover issues

- Do not assume that the issues disappear by themselves

- Perform root-cause analysis

- Feedback, and how to ensure that it is understood and accepted

- Soft skills coaching

- Soft skills training

- Escalating (if nothing else works)

6 thoughts on “Improving Communication in Clinical Research”

Nice article.thanks

Be sure to communicate in the mindset of a team member, or stakeholder with the same goals and not as an outsider looking in with judgement.

This is a great inspiring article.

Nice article! Thanks for sharing this informative post. Keep posting!

- Pingback: How To Succeed As A Clinical Trial Project Manager - Mosio

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Communicating and sharing your research

It is worthwhile considering what methods and communication channels you will use to share your research. Listed below are some common methods for communicating research with a range of audiences – academic, professional and general.

For academic purposes, share your research via these methods to increase the likelihood your research will be viewed, downloaded and cited. This will enable you to measure the impact and engagement of your work.

Researcher profiles

Creating and maintaining researcher profiles can foster connections with your research community, and maximises the visibility of your research outputs and impact. All RMIT researchers and HDR students are encouraged to have an ORCID profile. An ORCID profile can be used to display your research interests and activities, list your publications, qualifications and achievements, and link to other research and professional profiles. Some journals require researchers to provide their ORCID identifier when submitting articles for publication.

Blog, tweet, and post about your research

Consider writing a blog to share your research, or create a professional or academic Twitter or LinkedIn profile to connect with other researchers, share ideas and post links to your research writing and publications. Remember to include a DOI (Digital Object Identifier) when posting about your work – this will help you track citations, views and downloads. For more information regarding sharing using social media see the Library guide Social media for researchers .

For HDR Candidates

See the Thesis Whisperer and Research Whisperer blogs – both excellent resources for research students and early career researchers. If you have a Twitter profile, consider following their Twitter accounts. If you don’t use Twitter, consider signing up to the mailing list for either blog.

Watch this video for a brief introduction to using social media when communicating your research.

Communicate your research (2:14 mins)

“Communicate Your Research” by Andy Tattersall , ScHARR library is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Share your research data

Sharing your research data can be another method of promoting your research – the increased exposure may lead to new collaborations and new research projects with other researchers, or extra citations for your publications.

In some cases it may be mandated that you share your research data when submitting an article for publication. See the Library’s guide to Research Data Management for advice on managing and sharing your research data.

Test Your Knowledge

Research and Writing Skills for Academic and Graduate Researchers Copyright © 2022 by RMIT University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

← Back to blog

Published on August 5, 2019

Top tips and tools for effective research communication

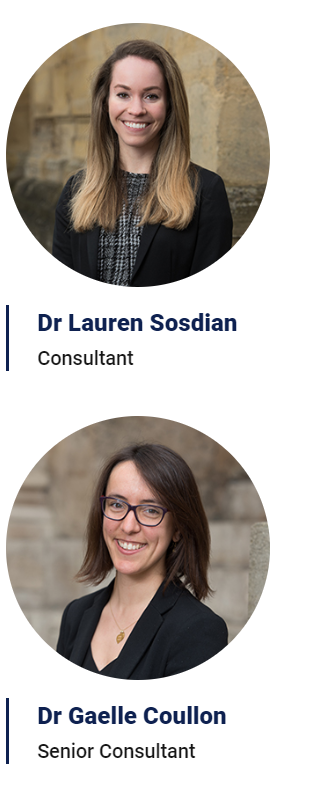

Academic researchers spend a significant proportion of their careers speaking to specialist audiences at conferences and applying for grants. However, sometimes even the best specialists struggle to clearly and concisely explain their work to a non-specialist audience. In the second article of our three-part series about the value of effective research communication, Oxentia consultants Dr Gaelle Coullon and Dr Lauren Sosdian explore some of the common mistakes researchers encounter when communicating to a non-specialist audience and provide a few tips and techniques to improve communication skills.

The ability to communicate with a non-specialist audience about the importance of your work doesn’t just make for a great TED talk. Research communication is a valuable skill for all academics to hone. It can help convince the listener about the importance of your work, it can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and improve how academics work with technology transfer offices, and it can help to make PhDs and Early Career Researchers more employable. We explored the benefits of good research communication in more detail in part one of this series .

Over the years, several different approaches have been taken to help researchers and entrepreneurs from all fields hone their communication skills. Below is a selection of four tools that we use when working with researchers and entrepreneurs which can help them tackle some of the challenges of research communication.

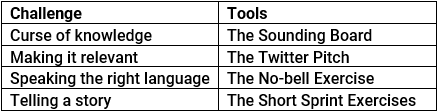

1. Curse of knowledge. Coined in Made to Stick 1 , the ‘curse of knowledge’ describes how knowing something very well means you become immune to the confusing and unique aspects of what you know. This can leave you unable to recognise when you are using technical terminology or jargon. However, at the other end of the spectrum, good research communication is not about ‘dumbing it down’. Good research communicators assume their audience is intelligent but just not equipped with the same technical expertise or language.

How can you overcome the curse of knowledge without ‘dumbing it down’? Complex ideas can be effectively communicated to any audience if the speaker can start by clearly explaining the core idea behind their research, using examples and metaphors to which we can all relate. Role-playing can help. For example, during our communication workshops, we would pair a researcher in microbiology who is preparing a marketing brief for her technology with a colleague in the department of sociology. Acting as a sounding board , this colleague would help her recognise the confusing elements of her work and identify better ways of explaining it.

2. Making it relevant. Even if researchers recognise that they aren’t communicating their work in a way that anyone can understand, many struggle in finding an alternative approach that would work better for a non-specialist audience. At a conference or in a journal publication, researchers are typically required to focus on technical descriptions of their methods and findings. With a non-specialist audience, the focus needs to be on the bottom-line of why we should care and what effect the research may have on the wider world. As pointed by Monica Metzler, founder and executive director of the Illinois Science Council (ISC), “the key difference between a technical talk and a lay audience talk is that we don’t want to know all about it” 2 .

One of the techniques we use to help researchers overcome the detail focus is a Twitter pitch . Used as part of a sprint toolkit workshop, this exercise takes participants out of their comfort zone by encouraging them to zero in on why we should care about their work and explain it in 280 characters.

3. Speaking the right language. When it comes to crafting the words used to describe their work, some researchers fail to recognise that some words, such as ‘theory’, ‘bias’ or ‘scheme’, have different meanings to different audiences. A Physics Today article 3 illustrates this point in relation to climate change – where the word ‘aerosol’ could easily be misunderstood by the public as a ’spray can’ when scientists actually mean ‘tiny atmospheric particle’.

Knowing your audience goes a long way in avoiding this pitfall. Understanding your audience will help convey why others should care about the research, but also help you tailor the story that you want to tell your audience. Don’t forget, the language you use when explaining your research at a public outreach conference will be very different to that which you use when pitching to an investor for a university spinout or how you explain your long days in the lab to your partner or friends.

One of the techniques that we use to help researchers better understand their audience is the no-bell exercise , a short exercise where participants pitch their work to colleagues from other departments who ring a bell if they hear a word or phrase that they do not understand. The objective is to finish the 3-minute pitch with no bells. This exercise forces participants to recognise when they are using jargon and then correct it, with the help of their colleagues.

4. Telling a story. Finally, really good research communicators tell a great story, one that uses clear, concise, and concrete language and examples. A brief history of the research project perhaps, the team who developed it, or how future work in this field could help improve someone’s life helps to engage your audience in the research question.

The series of short sprint exercises that we have developed as part of our training programmes are designed to help researchers craft compelling stories as well as new fun and interesting ways of talking about their research to a wide range of audiences. We explore how this works in practice in part three of our series.

How Oxentia can help

Oxentia, Oxford’s Global Innovation Consultancy, has worked with researchers in different disciplines at universities and institutions around the world for over fourteen years. Our experienced practitioner consultants work in over 70 countries for clients in governments, corporations, development agencies, and universities. This work has enabled us to develop training programmes featuring practical exercises and tool kits to help researchers better communicate their research to wider audiences, whether in STEM subjects or in the arts, humanities and social sciences.

Why do you think research communication is an important skill to develop in academia? Do researchers at your institution have access to communication training? Do you know other exercises and tips for effective research communication? Let us know in the comments on LinkedIn.

1 Chip Heath and Dan Heath (2007), “Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die”, Random House.

2 Science (2013), “Dispelling Myths About Science Communication”, https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2013/02/dispelling-myths-about-science-communication

3 Somerville and Hassol (2011), “Communicating the science of climate change”, Physics Today 64(10), pp 48-53.

This website site uses cookies to improve your browsing experience. By continuing to use this site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. Review our privacy policy .

- Strategy development

- Commercialisation Services

- Accelerators

- Privacy Policy

Stay up to date

- © 2024 Oxentia Limited

- [email protected]

- Privacy Statement

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.1; 2022 Dec

- PMC10194302

Novel approaches to communication skills development: The untapped potential of qualitative research immersion

Amy s. porter.

a St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA

Cameka Woods

Erica c. kaye, associated data.

Participation in qualitative research, particularly analysis of recorded medical dialogue, offers real-time, longitudinal immersion that can strengthen clinical trainee communication skills. The study objective was to explore how qualitative research participation impacts clinical trainees’ self-perceived communication skills development and practice.

In this study, a 17-member multidisciplinary working group of child life specialists, advanced practice providers, undergraduate/medical students, residents, fellows, attending physicians, social scientists, and career researchers with recent qualitative and communication research experience assembled to discuss this topic using a structured discussion guide. Content analysis was used to identify concepts and themes.

Three key themes characterizing the impact of qualitative research participation on aspiring clinicians’ communication skills development and practice arose – the 3Cs: (1) C onnection, therapeutic alliance, and accompaniment; (2) C larity and prognostic communication; (3) C ompassion, empathy, and understanding. Participants emphasized that qualitative research learning improved their understanding of patient/family lived experiences, preparing them for future clinical encounters, strengthening their emotional intelligence, and promoting self-care, resilience, and professional affirmation.

Conclusions

Immersion in clinical communication through participation in qualitative research is an under-utilized resource for supporting clinical trainees in communication skills development.

The process of collaborative knowledge production through the collective exploration of an a priori question related to group members’ collective experiences is methodologically innovative. Further, re-thinking qualitative research participation as an underutilized educational opportunity is pedagogically novel, and leaders in medical education and qualitative research should collaborate to realize the potential of this teaching tool.

- • Qualitative research participation offers immersion in clinical communication.

- • Participation impact characterized by the 3 C’s: 1) Connection, 2) Clarity, 3) Compassion.

- • This is an under-utilized medical education resource for communication skills development.

- • Medical education and qualitative research leaders should collaborate.

1. Introduction

Communication training for clinical trainees often involves single timepoint simulation as a “gold standard” for practicing navigation of challenging conversations [ [1] , [2] , [3] , [4] , [5] , [6] , [7] , [8] , [9] , [10] , [11] , [12] ]. Due to time, staffing, and resource constraints, medical educators face challenges realizing high volume of real-time communication learning opportunities [ 1 ]. Clinicians-in-training are exposed infrequently and inconsistently to in-depth, communication-heavy encounters between clinicians and patients and their families during difficult moments in the illness course [ 5 , 13 , 14 ]. As a result, trainees lack robust opportunities to witness communication and consider which modeled approaches they want to integrate into their own communication toolboxes. Further, depending on supervisory ratios, trainees may not have sufficient opportunities to observe clinicians with a range of emotional dexterity skills to learn and reflect on how (or how not) to communicate during challenging medical encounters.

Healthcare communication science researchers have amassed large repositories of recorded medical dialogue to answer questions about best practices for communication between patients, families, and healthcare professionals; however, little precedent exists for collaboration between communication researchers and medical education leaders to optimize use of this under-utilized resource to offer learners opportunities for developing communication skills through participation in communication research. Existing literature explores how guided reflection activities such as “The Healer’s Art” and other self-contemplative didactics positively impact trainees’ communication skills, empathy, self-awareness, and overall clinical practice [ [15] , [16] , [17] ], yet the potential educational value and impact of qualitative research experiences on trainees’ learning and communication skills remains understudied and poorly understood.

To address this knowledge gap, we convened a multidisciplinary working group of students, clinicians, and researchers to consider the question: “How does engaging in qualitative communication research (i.e., listening to audio recordings and/or reading transcripts of recorded clinical encounters) impact trainees as professionals (both clinicians and researchers) and as individuals holistically?” The Qu alitative research as E ducation for S tudents and clinicians-in- Tr aining (QUEST) working group comprised individuals affiliated with a communication research lab within an academic institution who each had recent experiences participating in qualitative research on topics related to communication. The working group examined whether engaging in qualitative research involving patients and families could influence the way students and clinicians-in-training learn and practice communication. In this article, we summarize findings from the QUEST working group and propose immersion in qualitative research datasets as an innovative alternative or complement to standardized simulated communication skills training.

In this study, we used an adaptation of autoethnography to bring together a team of authors with common experiences related to qualitative research participation, collectively share our perceptions and generate reflective data about our experiences with qualitative research, and collaborate with one another to analyze the data and present our insights. In traditional autoethnographic methods, an individual uses a reliable process to generate data from their own experience, observations, and reflections and then reflects on and synthesizes these data to inform a larger context [ 18 ]. Koopman et al describes autoethnography as the ultimate form of reflexivity, a mechanism by which to explore personal perceptions, values, and beliefs through the lens of lived experience, culture, and self-other interactions [ 19 ]. In this project, our authorship team wished to gain deeper insights into the potential influence of qualitative research participation on communication education for students and clinicians. In deciding to study ourselves, we developed a modified form of autoethnography, which we describe below. This paper reports the findings from the QUEST working group with all group members represented as authors; there were not separate groups representing “researchers” and “study participants,” but rather one collaborative group working together to explore an a priori question related to our collective experiences. As such, the project did not require IRB approval.

The authorship team convened as the QUEST working group, comprising a 17-member group of students, staff, and faculty with recent qualitative communication research experience, including undergraduate/medical students, residents, fellows, child life specialists, advanced practice providers, and clinical research staff. Within the Quality of Life and Palliative Care Research Division, all learners who had participated in communication research by listening to recorded medical dialogue or reading transcripts of interviews with patients, families, and clinicians at a particular academic institution over the past 3 years were invited via email to participate (n = 21). No exclusionary requirements were applied. Though all invited individuals expressed interest in joining the QUEST working group, a total of 17 people ultimately participated. Individuals agreed to participate in working group conversations by responding in writing to the email invitation. All working group members had participated in analysis of at least one qualitative data set related to communication, with most participating in qualitative research for at least one year (although outliers included 1 member with a 2-month qualitative research elective and 1 member with 5+ years of qualitative research participation). Most of the group was comprised of nursing/medical trainees (e.g., undergraduate, graduate, nursing, and medical students; fellows; n=13); the group also included 2 clinical research staff who engage in communication with patients and families, 1 child life specialist who participated in qualitative research, and 1 clinician-researcher who oversees qualitative research studies. Members’ training, roles, and experiences interfacing with different types of qualitative data are presented in Table 1 .

QUEST working group member characteristics.

The three lead authors crafted a semi-structured working group discussion guide, with iterative revisions to refine questions for content and language. Supplemental Figure presents the guide, encompassing a semi-structured outline of questions prompts and probes to organize and support cooperative conversation. Working group members were encouraged via email to join a virtual 120-minute discussion; those who could not attend were given an opportunity to respond to the questions in writing. A physician-medical anthropologist with training and expertise in group engagement facilitated the virtual discussion. Twelve QUEST working group members, including the three lead authors, attended the recorded virtual session using WebEx (an online platform for virtual group meetings). The conversation introduction included reminders about the importance of reflexivity and how participants’ positionality influences (and may bias) perspectives. Throughout the virtual discussion session, each participant remained engaged and interacted with most question probes, yielding multiple responses for each question. A working group format was used intentionally to explore the targeted question, given the positive potential for group dynamics to help with idea generativity and allow reflections to build upon others’ thoughts and observations [ 20 , 21 ]. Most working group members were students and trainees or clinical research staff, interacting within similar hierarchical tiers. Recognizing the potential for hierarchy to constrain conversation, the one faculty member in a supervisory position observed quietly, engaging only when asked a direct question by another working group member.

Five working group members were unable to attend the virtual discussion due to their training schedules, and they wished to participate in the exploratory question. To ensure inclusion of their voices and perspectives, they were given an opportunity to provide written reflection responses to each item in the structured discussion guide; these lengthy responses were shared via email to contribute their perspectives to the conversation.

Following data generation, the three lead authors initially conducted memo-writing of the recorded discussion and written responses to begin reflecting on and discussing emerging patterns in working group conversation content [ 22 ]. Memo-writers purposefully represented different perspectives from a current clinical trainee, a research staff member, and a faculty member, with iterative discussions held in person and via email to explore how different viewpoints influenced reflections in memos and examine internal biases shaping thoughts and assessments. Content analysis was used to synthesize working group transcripts as this method provides a rigorous process for identification of concepts and themes within text. As concepts were inductively generated via memo-writing, findings were shared with all QUEST members for iterative reflection and input. The QUEST working group collaborated to synthesize and review key themes, with cycles of review and refinement among authors [ 23 , 24 ]. The final report was presented to the working group for member-checking [ 25 ], with confirmation from all authors that thematic findings reflected the comprehensive content of working group discussions.

Working group members consistently emphasized the value of immersion in qualitative research, highlighting the utility of engagement with audio recorded and/or transcribed clinical encounters that included challenging communication scenarios ( Fig. 1 ). Nearly all members described the impact of qualitative research experiences on their personal communication skills and practice, and two driving themes emerged to characterize the “value added” by qualitative research: 1) the tangible benefits of exposure to difficult medical communication prior to real-life encounters; and 2) the potential for long-lasting impact and sustained influence of qualitative research experiences on future clinical practice, including three specific impacts on communication skills (“the 3Cs”).

Influences of qualitative research immersion on learner communication skills.

3.1. Immersive learning prior to real-life training and practice

For many working group members, communication challenges in healthcare were largely hypothetical prior to their participation in qualitative research. Coding real clinical encounters as part of qualitative research revealed the complexity of interpersonal communication and offered lessons for how to navigate difficult conversations with actual patients and families: “I really saw models of what this actually looks like and how do patients and their families respond to different styles.” Authors with limited previous exposure to clinical encounters also shared how immersion in raw qualitative data helped them recognize the emotional intensity experienced by patients, families, and clinicians:

“Listening [to audio-recorded medical dialogue] really helped me to understand how much tension there can be in a room… Just listening to long pauses of silence helped me understand that [prognostic communication] can be really challenging emotionally, both on the clinician side and the family and patient side, how challenging it can be to navigate that both as a parent and as a clinician.”

Another member described how her participation in qualitative research as a medical student informed her future practice as a resident:

“I began intern year in the intensive care unit and had several patients die within my first two to three weeks of residency. Communicating with these families about the goals or priorities of their loved one and then having to tell them when that person had died required attention to detail, meticulous word choice, and rapport building. All of these skills were taught or honed by the coding experience.”

Universally, working group members highlighted how exposure to “real” clinical encounters offered them unique experiences to observe communication skills and reflect on interpersonal dynamics that they could carry forward into their future clinical practice.

3.2. Sustained influence on future clinical practice

Overall, working group members agreed that participating in qualitative research had a greater impact than they anticipated on the way that they provide clinical care. One child life specialist explained specifically how real clinical encounters still shape her everyday clinical practice:

“I was not anticipating the coding experience [would] play such an influential role in my day-to-day clinical practice. The process has made me more reflective in my everyday interactions with patients and families, as I have various narratives to refer back to, and [they] are typically at the forefront of my thoughts when interacting with families now.”

A palliative care physician explained how specific clinician-patient or clinician-family interactions persist in a clinician’s mind through years of clinical practice: “Some of the quotes stick with you and influence your practice.” Many working group members echoed this idea of staying power – conversations witnessed through reading transcripts or listening to audio recordings remained impressed on their minds as reference points for choosing language, reflecting on clinical encounters, and remembering the complexities of patients’ and families’ experiences.

The working group also identified three key themes characterizing how immersion in qualitative communication research influenced aspiring clinicians’ self-perceived communication skills development – the 3Cs ( Table 2 ): 1) C onnection, therapeutic alliance, and accompaniment; 2) C larity and prognostic communication; and 3) C ompassion, empathy, and understanding.

3Cs: Key themes characterizing the impact of qualitative research participation on learners’ communication skills development.

3.3. Skills for aspiring clinicians: connection

Working group members described how witnessing clinicians’ approaches for establishing connection and building therapeutic alliance with patients and families helped them learn how to develop their own skills. Many mentioned the importance of listening carefully to patients and families, as well as the value of silence:

“This experience helped me further develop active listening skills. I think silence is something that often makes people uncomfortable; however, this experience made me realize how many families…want and need a space to process and have others actively listen to their thoughts and emotions. It was very humbling to be a part of that process.”

As detailed in Table 2 , others discussed how they came to realize that affirming patients’ and families’ emotions is essential to establishing therapeutic alliance and how witnessing clinicians establish rapport with families led them to aspire to do the same in their own clinical practice.

Several working group members contemplated the sensation of privilege upon entering what felt like experiencing prognostic communication with the patient and family – accompanying them through the illness trajectory. One nurse practitioner explained that, despite having been a bedside oncology nurse prior to participating in qualitative research, listening to recorded conversations was the first time she had been “in the room” during prognostic disclosure:

“What really struck me was how you do feel like you’re living through the process with the family… Living all those intense moments with the family feels extremely different than even what the providers themselves might feel.”

Some participants felt the emotion of experiencing disease reevaluation discussions with the families so intensely that they became uncomfortable and concerned they might be intruding: “In a way, it almost feels like you are listening to a private conversation, like you’re impinging on their privacy.” All participants agreed that reviewing transcripts and recordings represented more than a research task – for many, it felt like an honor to witness families most challenging moments.

3.4. Skills for aspiring clinicians: clarity

One working group member, who began qualitative research as an undergraduate student and is currently a medical resident, explained how her prior experiences with qualitative research actively motivate her to be clearer in her communication with patients and families:

“My experience with [reading transcripts] has…informed core beliefs I have regarding communication with patients, especially related to giving bad news… Remembering how [a particular] family felt from not discussing the full extent of the truth encourages me to…talk about all possible outcomes early… It also motivates me to be honest, even when it is hard. So many parents [in interviews]…said they didn’t want someone to ‘beat around the bush.’ I want to tell the truth in a kind way and set the scene for success.”

Another member, who was exposed to qualitative research while practicing as a child life specialist, also underscored how qualitative research training has helped her better understand the value of intentionality when communicating bad news, including exploring and accepting patients’ and families’ reactions to the news conveyed:

“The experience of coding has definitely influenced my clinical practice. One parent…shared that her first thought when our team offered legacy building interventions was: ‘Are you f***ing kidding me?’ I find myself actively thinking about this parent and her reaction every time that I am about to offer these types of interventions – and furthermore thinking about the themes that emerged when coding this data that reiterated the various ways our introduction of these interventions may be improved.”

Several working group members also explained that clinical communication research projects led them to develop heightened awareness of the impact of language on patients/families: “[I developed] awareness that the words that we use can have these long-lasting ramifications and impact. It gives you a heightened cognizance of how important the language and interactions are.”

3.5. Skills for aspiring clinicians: compassion

Compassion through understanding and empathy was a pervasive theme across working group members’ reflections on participating in qualitative research: “I think [participation in qualitative research] helps foster empathy and compassion. Medicine can be very draining; there are many systemic barriers to providing care in a patient-centered, thoughtful, and kind way.” Many articulated how qualitative research participation helped them to dig deeper into patients’ and families’ stories, not just limited to clinical encounters in clinical spaces: “Seeing the stories, not just the patients. This work inherently teaches you about the value of the story.” One author explained that this sense of walking with patients and families helped foster patience: “I think [patience] comes from having more perspective into their narrative and giving them the benefit of the doubt because you have not just the hospital, clinical side – you have more insight into the other side of things.” Working group members emphasized how more complex understandings of patients’ and families’ lives generated deeper understanding and compassion, which they recognized as skills integral to provision of high-quality medical care in their future careers.

3.6. Unanticipated impact: Self-care and professional affirmation

Working group members identified various unexpected positive outcomes from participation in qualitative research, including how it influenced perceptions of self-care and professional affirmation. Witnessing the strength and wisdom of parents of children with serious illness and/or bereaved parents inspired many learners. One member explained that studying communication through qualitative research methods allowed her to be less harsh on herself in evaluating her own communication: “This experience has provided me with the space to allow myself grace when I know I could have completed an intervention in a different way.” Several also shared that the research experience has affirmed their decisions into go into healthcare professions:

“I remember sitting down and really listening to one of the conversations, and immediately, I was so filled with emotion that tears really filled my eyes, partly because of the emotion of the conversation but also because I had been longing for this viewpoint, as it addressed why I had become really passionate about nursing. It reignited my passion for nursing and healthcare.”

Another echoed this same idea, explaining that the work reinvigorated her medical studies: “Seeing how this life experience affects these parents each and every day really allowed me to see the gravity of the situation and gave me the motivation to continue on this journey towards becoming a doctor.”

An additional unexpected benefit of qualitative research participation was deconstruction of hierarchy in clinical medicine. The process through which team members from various roles and statuses came together to reach consensus in coding belied self-perceived hierarchical identities:

“I was surprised by the richness of diligence and detail involved in the work, including check mechanisms that produced consensus. I found the reconciliation process to be a perfect example of this. The meetings were equal parts presentation of fact and defense of personal standpoint that involved everyone as an equal partnered contributor.”

An author who participated in this research as an undergraduate emphasized the power of connection among team members that overrode the difference of education level or training experience: “We connected on raw emotion that we felt from the conversation – even though we may be at very different stages of life, we still felt the same responses to some scenarios.”

Working group members emphasized that qualitative research participation also helped them develop skills in teaching and mentoring, as well as influenced how they approached the development of communications training programs and curricula in the future. Finally, they explained that it inspired them to continue self-reflection on communication, driving them to develop their practices of life-long learning. Table 3 articulates both benefits in more detail. Alongside these positive benefits, working group members also identified unexpected challenges, acknowledging the emotional weight of accompanying families, bearing witness, and feeling responsible for empathetic and compassionate communication, detailed in Table 4 .

Benefits of qualitative research participation as educators and life-long learners.

Unexpected challenges of participation in qualitative research: the emotional weight of accompanying families, bearing witness, and feeling responsible for empathetic and compassionate communication.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. discussion.

Clinician-researchers with immersive experience in qualitative research identified the value of research participation on gaining and sustaining important communication skills. Key lessons from the working group are summarized in Fig. 2 .

Key takeaway lessons from exploratory investigation of influences of participation in qualitative research on clinicians-in-training.

These findings raise the possibility that opportunities for participation in qualitative research alongside communication scientists may be an under-utilized resource for medical educators seeking to support trainees in developing important communication skills. Theories of experiential learning [ 26 , 27 ] and reflexive learning [ 28 , 29 ] underscore the potential educational benefit of qualitative research participation [ 30 ], in that they suggest that learning through doing and informally and formally reflecting on experiences may be more effective at conveying key lessons in clinical communication than didactics, small group discussions, or other instruction on the topic. We encourage medical educators and communication researchers to explore strategies for collaboration through engagement of undergraduate, graduate, medical, and post-graduate clinicians- and researchers-in-training. Rethinking the potential of qualitative research to improve clinical education may be bidirectionally beneficial, strengthening communication skills training while also reinforcing the value of qualitative research.

Further, these data preliminarily suggest that regular immersion in qualitative data may support resilience building for learners, and future research is needed to explore this potential. Listening to recordings or reading transcripts from clinical encounters offers trainees a unique opportunity to bear witness and experience diagnostic or prognostic communication, metaphorically standing alongside the patient and family, while still maintaining space to reflect, question, cry, otherwise respond, pause, discuss, and debrief the encounter. DIPEx International and other similar resources amalgamating qualitative research data can be incorporated into learning opportunities that enable more clinical trainees to conduct qualitative research.

The research team functions as a support group within which researchers can process the emotional weight and lessons learned from the encounter. This “practice run” prior to driving difficult conversations offers trainees the chance to develop communications skills and bolster both their approach and confidence prior to patient encounters [ 31 ]. Prior qualitative research experiences enable trainees to avoid feeling overwhelmed, hitting the ground running, prepared for the emotional burden and capable of listening, leaving room for silence, building empathy, and prioritizing compassion. Working group members felt prepared not only to practice skillful communication, but also to teach strategies.

Findings from the work should be interpreted in the context of limitations. Working group members all had participated in qualitative research previously and thus likely had a predisposition for engagement with and enthusiasm for communication research and qualitative methodology. It is possible that a different group of learners – perhaps those who tend toward a more positivist sensibility – may not find participation in qualitative research as useful for communication skills development. Additionally, not all QUEST working group members had an opportunity to participate in collective, generative dialogue to build upon ideas in real time. Several members participated by sharing their perspectives in writing, and although this allowed for enrichment of perspectives and experiences, it is not possible to know how additional interaction may have shaped the collective message.

Innovation: We offer two innovative approaches to healthcare professions education. First, we offer an innovative research methodology – an adaptation of autoethnography that involves collaboration among a group of people who share an experience (i.e., qualitative research participation), generate reflective data about that experience, and then work together to analyze those data. The methodology carried out by the collaborative working group to explore an a priori question related to our collective experiences is innovative, in that there was no division between “researchers” and “study participants” and thus the process was not traditional “research” but rather collaborative generation of knowledge. Inspired by autoethnographic methods, in which one person generates data from their own experiences, observations, and reflections and then analyzes those data, we have embarked upon a modified autoethnographic endeavor in which we collected data from ourselves as a working group made up of people with shared qualitative communication research participation experience and then analyzed and interpreted those data collectively. Different members of the working group participated in different ways to generate and analyze the data; we generated our own data and then studied our own experiences by analyzing the data. This methodology enables and may even empower health professions educators to study their own educational innovations.

Second, we offer a pedagogical innovation for health professions education, in which participation in qualitative research provides a learning experience for students in the health professions. We found that experience in qualitative research about communication facilitated learning about how to connect with patients and families, communicate clearly, and practice with empathy and compassion. Beyond the communication domain, additional applications of qualitative research experience as a learning opportunity might involve topics such as resilience, mindfulness, meaning-making, and self-reflection as tools to combat burnout or compassion fatigue.

With regards to application of findings, rethinking qualitative research participation as an underutilized educational opportunity is pedagogically innovative and should inspire medical education leaders to collaborate with communication researchers in engagement of undergraduate, graduate, medical, and post-graduate trainees. Collaborations between health professions educators and qualitative researchers could lead beyond communication, expanding to teaching about self-awareness, humility, active listening, quiet observation, and the critical importance of triangulating data to deepen information synthesis and interpretation. Rich opportunities exist to further probe how students immersed in qualitative research gain knowledge and skills. Further research also is needed to explore the benefits of partnerships between medical education and qualitative research teams in development of immersion-based communication learning.

4.2. Conclusion

Exposing clinical trainees to communication through participation in qualitative research has the potential to enhance self-perceived communication competency in three key domains: (1) Connection, (2) Clarity, and (3) Compassion, preparing them for future clinical encounters. Further, such exposure may have the potential to strengthen emotional intelligence and promote self-care, professional affirmation, and resilience.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Credit author statement

Amy Porter: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draftWriting

Cameka Woods: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Erica Kaye: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft

All other authors: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Declaration of Competing Interest

Acknowledgements.

We thank working group members’ qualitative research mentors and collaborators for providing teaching and support throughout their qualitative research experiences.

Appendix A Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecinn.2022.100079 .

Contributor Information

Taylor aglio, jacob applegarth.

b Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, Royal Oak, MI, USA (Jacob)

Tharwa Bilbeisi

c University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA

d Rhodes College, Memphis, TN, USA

Katie Greer

e University of California Davis Children’s Hospital, Sacramento, CA, USA

Rachel Huber

Ashley kiefer autrey.

f Children’s Hospital of New Orleans, New Orleans, LA, USA

Sarah Rockwell

g Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Marta Salek

Melanie stall.

h University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA

Mariela Trejo

i University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

j University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center, Memphis, TN, USA

Kristina Zalud

k St. Louis Children’s Hospital, St. Louis, MO, USA

Appendix A. Supplementary data

QUEST Working Group Discussion Guide

- Advisers & Contacts

- Bachelor of Arts & Bachelor of Science in Engineering

- Prerequisites

- Declaring Computer Science for AB Students

- Declaring Computer Science for BSE Students