Jump to content

Psychiatry Academy

Bookmark/search this post.

You are here

Collaborative problem solving.

- Register/Take course

At Think:Kids at Massachusetts General Hospital (https://thinkkids.org/) we transform the lives of kids and families by spreading a more accurate and empathic view of children with challenging behavior. We do this by teaching adults our revolutionary, evidence-based Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) approach. CPS is an approach to responding to challenging behavior that promotes the understanding that kids with behavioral challenges lack the skill—not the will—to behave ; specifically, skills related to problem-solving, flexibility, and frustration tolerance.

Research has shown that CPS reduces challenging behavior, stress levels, and punitive responses and teaches kids the skills they lack while building helping relationships with adults in their lives. Unlike traditional discipline models, the CPS approach avoids using power, control, and motivational procedures. Instead, it focuses on collaborating with kids to solve the problems leading to their challenging behavior and build the skills they need to succeed.

*PLEASE NOTE* Collaborative Problem Solving is not for CME credit.

Collaborative Problem Solving® Tier 1 Training: Essential Foundation

Tier 1 training covers all aspects of the evidence-based CPS approach, including assessment, planning, and intervention, as well as the neurobiology behind the approach.

Collaborative Problem Solving® Tier 2 Training: Advanced Concepts

Tier 2 training deepens skills at all phases of the approach, enhances implementation in the real world, including in group and emergency situations, and discusses how to use CPS to enhance cultural responsiveness. A focus on deepening skills at all phases of the approach and enhancing implementation in the real world.

Target Audience

This program is intended for professionals from different disciplines related to child mental health. This includes physicians, psychologists, social workers, licensed mental health counselors and nurses.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this training, participants will be able to:

- Understand why traditional approaches may not be well suited to the needs of children with social, emotional, and behavioral challenges.

- Learn the philosophy of the CPS approach.

- Identify the five cognitive skills that are frequently lacking in kids with challenging behaviors.

- Develop expectations for youth that are realistic and age appropriate.

- Know when to use the three primary interventions based on the goal at hand.

- Learn how CPS operationalizes the latest research on trauma-informed care.

By the end of this training, participants will be able to:

- Troubleshoot all aspects of CPS, even in the most challenging situations.

- Utilize CPS in group settings, emergency, and spontaneous situations.

- Apply CPS in a neuro-biologically informed manner.

- Work with other adults who are rooted in conventional wisdom.

- Use CPS to enhance cultural responsiveness.

- Identify strategies for ongoing learning and application at home, work, and in larger systems.

Collaborative Problem Solving® Tier 1 Training: Essential Foundation

Tier 1 In-Person Schedule:

Coaching Schedule Group 1 (Virtual)

Zoom Room: https://partners.zoom.us/j/83621462450?pwd=M3pPVVZkb00rUkFIQjV4dkEvajdxdz09

Password: CPS

Coaching Schedule Group 2 (Virtual)

Zoom Room: https://partners.zoom.us/j/85600268527?pwd=aGZxa1ZFdGhVa2wzdzNOZTF2dW1oQT09

Tier 2 In- Person Schedule

Stuart Ablon, PhD

Heather johnson, phd.

- skip to Cookie Notice

- skip to Main Navigation

- skip to Main Content

- skip to Footer

Safe Care Commitment Get the latest news on COVID-19, the vaccine and care at Mass General. Learn more

- Find a Doctor

- Find a Location

- Appointments & Referrals

- Patient Gateway

- Leadership Team

- Quality & Safety

- Equity & Inclusion

- Community Health

- Education & Training

- Centers & Departments

- Browse Treatments

- Browse Conditions A-Z

- View All Centers & Departments

- Clinical Trials

- Cancer Clinical Trials

- Cancer Center

- Digestive Healthcare Center

- Heart Center

- MassGeneral Hospital for Children

- Neuroscience

- Orthopaedics

- Information for Visitors

- Maps & Directions

- Parking & Shuttles

- Services & Amenities

- Accessibility

- Visiting Boston

- International Patients

- Urgent Care

- Medical Records

- Billing, Insurance & Financial Assistance

- Privacy & Security

- Explore Our Laboratories

- Industry Collaborations

- Research & Innovation News

- About the Research Institute

- Innovation Programs

- Education & Community Outreach

- Support Our Research

- Find a Researcher

- News & Events

- Ways to Give

- View All Centers & Departments -->

- Patient Rights & Advocacy

- Website Terms of Use

- Apollo (Intranet)

- View All Centers and Departments

- Anesthesia, Critical Care & Pain Medicine

- Dermatology

- Emergency Medicine

- Neurosurgery

- Nursing & Patient Care Services

- Obstetrics & Gynecology

- Ophthalmology

- Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Pediatrics & Pediatric Surgery

- Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation

- Primary Care

- Radiation Oncology

- Social Service

- Transplant Center

- Trauma Center

- Vascular Center

- Facts at a Glance

- For Researchers

- Hospital Wide Centers

- Department-Based Centers

- Division of Clinical Research

- Research Areas of Interest

- Research Articles

- Research Press Releases

- Newsletters

- Why Mass General

- Strategic Alliances

- Translational Research Center

- Partners Innovation

- Collaboration News

- Centers for Innovation in Care Delivery

- Healthcare Transformation Lab

- Innovations in Primary Care

- Learning Laboratory

- Medicine Innovation Program

- MESH Incubator

- Mass General Community

- Community Outreach

Mass General Research Institute

J. Stuart Ablon, Ph.D.

Research interests, research narrative.

J. Stuart Ablon, Ph.D., is the Director of Think:Kids in the Department of Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital. He is also Associate Clinical Professor of Psychology in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Ablon co-founded the Center for Collaborative Problem Solving where he also served as Co-Director from its inception until 2008. Dr. Ablon is co-author of Treating Explosive Kids: The Collaborative Problem Solving Approach and author of numerous articles, chapters and scientific papers on the process and outcome of psychosocial interventions. A dynamic and engaging speaker, Dr. Ablon was recently ranked #5 on the list of the world’s top rated keynote speakers in the academic arena.

Dr. Ablon’s research has been funded by, amongst others, the National Institute of Health, the American Psychological Association, the American Psychoanalytic Association, the International Psychoanalytic Association, the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Institute, and the Endowment for the Advancement of Psychotherapy. Dr. Ablon received his doctorate in clinical psychology from the University of California at Berkeley and completed his predoctoral and postdoctoral training at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Dr. Ablon trains parents, educators, and clinicians and consults to schools and treatment programs throughout the world in the Collaborative Problem Solving approach.

Contact Info

Collaborative Problem Solving

An Evidence-Based Approach to Implementation and Practice

- © 2019

- Alisha R. Pollastri 0 ,

- J. Stuart Ablon 1 ,

- Michael J.G. Hone 2

Think:Kids Program, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Crossroads Children’s Mental Health Centre, Ottawa, Canada

- Concise guide written for ease-of-use across mental health and para-professionals interested in behavioral management

- Focused on clinical practice and implementation across settings

- Written by thought leaders in Collaborative Problem Solving

Part of the book series: Current Clinical Psychiatry (CCPSY)

10k Accesses

14 Citations

39 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (9 chapters)

Front matter, what is collaborative problem solving and why use the approach.

- J. Stuart Ablon

CPS as a Neurodevelopmentally Sensitive and Trauma-Informed Approach

- Bruce D. Perry, J. Stuart Ablon

How to Apply Implementation Science Frameworks to Support and Sustain Change

- Michelle A. Duda, Alexia Jaouich, Trevor W. Wereley, Michael J. G. Hone

Implementing CPS in Clinical Settings

- Robert E. (Bob) Lieberman, Whitney Vail, Kevin George

Implementing CPS in Educational Settings

- Erica A. Stetson, Amy E. Plog

CPS in a Large Multiservice Organization: A Case Study

- Katherine G. Peatross, Kathleen A. McNamara

Implementing and Practicing Collaborative Problem Solving with Integrity

- Alisha R. Pollastri, Arielle Wezdenko

Research and Evaluation of CPS Outcomes

- Alisha R. Pollastri, Lu Wang

Using CPS to Foster Employee Success

- Michael J. G. Hone

Back Matter

- Trauma-informed care

- Behavioral challenges in children

- Community-Based care

- Program implementation

- Non-punitive responses

About this book

This book is the first to systematically describe the key components necessary to ensure successful implementation of Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) across mental health settings and non-mental health settings that require behavioral management. This resource is designed by the leading experts in CPS and is focused on the clinical and implementation strategies that have proved most successful within various private and institutional agencies. The book begins by defining the approach before delving into the neurobiological components that are key to understanding this concept. Next, the book covers the best practices for implementation and evaluating outcomes, both in the long and short term. The book concludes with a summary of the concept and recommendations for additional resources, making it an excellent concise guide to this cutting edge approach.

Collaborative Problem Solving is an excellent resource for psychiatrists,psychologists, social workers, and all medical professionals working to manage troubling behaviors. The text is also valuable for readers interested in public health, education, improved law enforcement strategies, and all stakeholders seeking to implement this approach within their program, organization, and/or system of care.

Editors and Affiliations

Alisha R. Pollastri, J. Stuart Ablon

Michael J.G. Hone

About the editors

Alisha Pollastri, Ph.D. Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry: Think:Kids 151 Merrimac Street Boston MA 02114

Michael Hone Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry: Think:Kids 151 Merrimac Street Boston MA 02114

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Collaborative Problem Solving

Book Subtitle : An Evidence-Based Approach to Implementation and Practice

Editors : Alisha R. Pollastri, J. Stuart Ablon, Michael J.G. Hone

Series Title : Current Clinical Psychiatry

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12630-8

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Medicine , Medicine (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-12629-2 Published: 18 June 2019

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-12630-8 Published: 06 June 2019

Series ISSN : 2626-241X

Series E-ISSN : 2626-2398

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XVII, 206

Number of Illustrations : 2 b/w illustrations, 9 illustrations in colour

Topics : Psychiatry , Clinical Psychology , Public Health , Pediatrics , Social Work

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 11 January 2023

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis based on empirical literature

- Enwei Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6424-8169 1 ,

- Wei Wang 1 &

- Qingxia Wang 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 16 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

13 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely embraced in the classroom instruction of critical thinking, which is regarded as the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education as well as a key competence for learners in the 21st century. However, the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking remains uncertain. This current research presents the major findings of a meta-analysis of 36 pieces of the literature revealed in worldwide educational periodicals during the 21st century to identify the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and to determine, based on evidence, whether and to what extent collaborative problem solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. The findings show that (1) collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster students’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]); (2) in respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem solving can significantly and successfully enhance students’ attitudinal tendencies (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.58, 0.82]); and (3) the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have an impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. On the basis of these results, recommendations are made for further study and instruction to better support students’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Similar content being viewed by others

A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis of the physical and mental health benefits of touch interventions

Impact of artificial intelligence on human loss in decision making, laziness and safety in education

Sleep quality, duration, and consistency are associated with better academic performance in college students

Introduction.

Although critical thinking has a long history in research, the concept of critical thinking, which is regarded as an essential competence for learners in the 21st century, has recently attracted more attention from researchers and teaching practitioners (National Research Council, 2012 ). Critical thinking should be the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education (Peng and Deng, 2017 ) because students with critical thinking can not only understand the meaning of knowledge but also effectively solve practical problems in real life even after knowledge is forgotten (Kek and Huijser, 2011 ). The definition of critical thinking is not universal (Ennis, 1989 ; Castle, 2009 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). In general, the definition of critical thinking is a self-aware and self-regulated thought process (Facione, 1990 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). It refers to the cognitive skills needed to interpret, analyze, synthesize, reason, and evaluate information as well as the attitudinal tendency to apply these abilities (Halpern, 2001 ). The view that critical thinking can be taught and learned through curriculum teaching has been widely supported by many researchers (e.g., Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), leading to educators’ efforts to foster it among students. In the field of teaching practice, there are three types of courses for teaching critical thinking (Ennis, 1989 ). The first is an independent curriculum in which critical thinking is taught and cultivated without involving the knowledge of specific disciplines; the second is an integrated curriculum in which critical thinking is integrated into the teaching of other disciplines as a clear teaching goal; and the third is a mixed curriculum in which critical thinking is taught in parallel to the teaching of other disciplines for mixed teaching training. Furthermore, numerous measuring tools have been developed by researchers and educators to measure critical thinking in the context of teaching practice. These include standardized measurement tools, such as WGCTA, CCTST, CCTT, and CCTDI, which have been verified by repeated experiments and are considered effective and reliable by international scholars (Facione and Facione, 1992 ). In short, descriptions of critical thinking, including its two dimensions of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, different types of teaching courses, and standardized measurement tools provide a complex normative framework for understanding, teaching, and evaluating critical thinking.

Cultivating critical thinking in curriculum teaching can start with a problem, and one of the most popular critical thinking instructional approaches is problem-based learning (Liu et al., 2020 ). Duch et al. ( 2001 ) noted that problem-based learning in group collaboration is progressive active learning, which can improve students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Collaborative problem-solving is the organic integration of collaborative learning and problem-based learning, which takes learners as the center of the learning process and uses problems with poor structure in real-world situations as the starting point for the learning process (Liang et al., 2017 ). Students learn the knowledge needed to solve problems in a collaborative group, reach a consensus on problems in the field, and form solutions through social cooperation methods, such as dialogue, interpretation, questioning, debate, negotiation, and reflection, thus promoting the development of learners’ domain knowledge and critical thinking (Cindy, 2004 ; Liang et al., 2017 ).

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely used in the teaching practice of critical thinking, and several studies have attempted to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature on critical thinking from various perspectives. However, little attention has been paid to the impact of collaborative problem-solving on critical thinking. Therefore, the best approach for developing and enhancing critical thinking throughout collaborative problem-solving is to examine how to implement critical thinking instruction; however, this issue is still unexplored, which means that many teachers are incapable of better instructing critical thinking (Leng and Lu, 2020 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). For example, Huber ( 2016 ) provided the meta-analysis findings of 71 publications on gaining critical thinking over various time frames in college with the aim of determining whether critical thinking was truly teachable. These authors found that learners significantly improve their critical thinking while in college and that critical thinking differs with factors such as teaching strategies, intervention duration, subject area, and teaching type. The usefulness of collaborative problem-solving in fostering students’ critical thinking, however, was not determined by this study, nor did it reveal whether there existed significant variations among the different elements. A meta-analysis of 31 pieces of educational literature was conducted by Liu et al. ( 2020 ) to assess the impact of problem-solving on college students’ critical thinking. These authors found that problem-solving could promote the development of critical thinking among college students and proposed establishing a reasonable group structure for problem-solving in a follow-up study to improve students’ critical thinking. Additionally, previous empirical studies have reached inconclusive and even contradictory conclusions about whether and to what extent collaborative problem-solving increases or decreases critical thinking levels. As an illustration, Yang et al. ( 2008 ) carried out an experiment on the integrated curriculum teaching of college students based on a web bulletin board with the goal of fostering participants’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These authors’ research revealed that through sharing, debating, examining, and reflecting on various experiences and ideas, collaborative problem-solving can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking in real-life problem situations. In contrast, collaborative problem-solving had a positive impact on learners’ interaction and could improve learning interest and motivation but could not significantly improve students’ critical thinking when compared to traditional classroom teaching, according to research by Naber and Wyatt ( 2014 ) and Sendag and Odabasi ( 2009 ) on undergraduate and high school students, respectively.

The above studies show that there is inconsistency regarding the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a thorough and trustworthy review to detect and decide whether and to what degree collaborative problem-solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. Meta-analysis is a quantitative analysis approach that is utilized to examine quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. This approach characterizes the effectiveness of its impact by averaging the effect sizes of numerous qualitative studies in an effort to reduce the uncertainty brought on by independent research and produce more conclusive findings (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ).

This paper used a meta-analytic approach and carried out a meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking in order to make a contribution to both research and practice. The following research questions were addressed by this meta-analysis:

What is the overall effect size of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills)?

How are the disparities between the study conclusions impacted by various moderating variables if the impacts of various experimental designs in the included studies are heterogeneous?

This research followed the strict procedures (e.g., database searching, identification, screening, eligibility, merging, duplicate removal, and analysis of included studies) of Cooper’s ( 2010 ) proposed meta-analysis approach for examining quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. The relevant empirical research that appeared in worldwide educational periodicals within the 21st century was subjected to this meta-analysis using Rev-Man 5.4. The consistency of the data extracted separately by two researchers was tested using Cohen’s kappa coefficient, and a publication bias test and a heterogeneity test were run on the sample data to ascertain the quality of this meta-analysis.

Data sources and search strategies

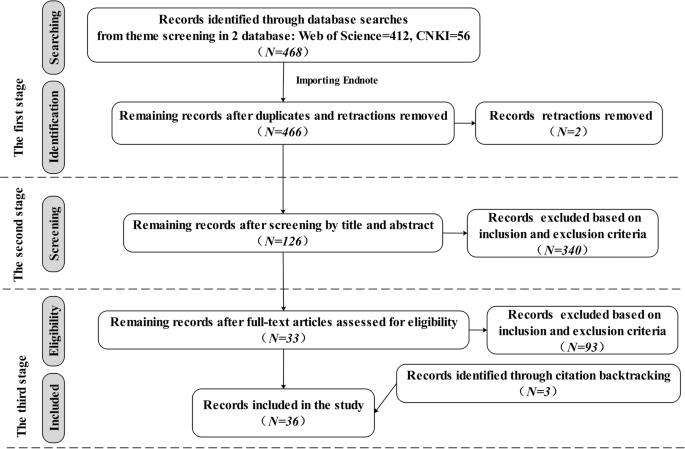

There were three stages to the data collection process for this meta-analysis, as shown in Fig. 1 , which shows the number of articles included and eliminated during the selection process based on the statement and study eligibility criteria.

This flowchart shows the number of records identified, included and excluded in the article.

First, the databases used to systematically search for relevant articles were the journal papers of the Web of Science Core Collection and the Chinese Core source journal, as well as the Chinese Social Science Citation Index (CSSCI) source journal papers included in CNKI. These databases were selected because they are credible platforms that are sources of scholarly and peer-reviewed information with advanced search tools and contain literature relevant to the subject of our topic from reliable researchers and experts. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the Web of Science was “TS = (((“critical thinking” or “ct” and “pretest” or “posttest”) or (“critical thinking” or “ct” and “control group” or “quasi experiment” or “experiment”)) and (“collaboration” or “collaborative learning” or “CSCL”) and (“problem solving” or “problem-based learning” or “PBL”))”. The research area was “Education Educational Research”, and the search period was “January 1, 2000, to December 30, 2021”. A total of 412 papers were obtained. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the CNKI was “SU = (‘critical thinking’*‘collaboration’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘collaborative learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘CSCL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem solving’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem-based learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘PBL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem oriented’) AND FT = (‘experiment’ + ‘quasi experiment’ + ‘pretest’ + ‘posttest’ + ‘empirical study’)” (translated into Chinese when searching). A total of 56 studies were found throughout the search period of “January 2000 to December 2021”. From the databases, all duplicates and retractions were eliminated before exporting the references into Endnote, a program for managing bibliographic references. In all, 466 studies were found.

Second, the studies that matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the meta-analysis were chosen by two researchers after they had reviewed the abstracts and titles of the gathered articles, yielding a total of 126 studies.

Third, two researchers thoroughly reviewed each included article’s whole text in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Meanwhile, a snowball search was performed using the references and citations of the included articles to ensure complete coverage of the articles. Ultimately, 36 articles were kept.

Two researchers worked together to carry out this entire process, and a consensus rate of almost 94.7% was reached after discussion and negotiation to clarify any emerging differences.

Eligibility criteria

Since not all the retrieved studies matched the criteria for this meta-analysis, eligibility criteria for both inclusion and exclusion were developed as follows:

The publication language of the included studies was limited to English and Chinese, and the full text could be obtained. Articles that did not meet the publication language and articles not published between 2000 and 2021 were excluded.

The research design of the included studies must be empirical and quantitative studies that can assess the effect of collaborative problem-solving on the development of critical thinking. Articles that could not identify the causal mechanisms by which collaborative problem-solving affects critical thinking, such as review articles and theoretical articles, were excluded.

The research method of the included studies must feature a randomized control experiment or a quasi-experiment, or a natural experiment, which have a higher degree of internal validity with strong experimental designs and can all plausibly provide evidence that critical thinking and collaborative problem-solving are causally related. Articles with non-experimental research methods, such as purely correlational or observational studies, were excluded.

The participants of the included studies were only students in school, including K-12 students and college students. Articles in which the participants were non-school students, such as social workers or adult learners, were excluded.

The research results of the included studies must mention definite signs that may be utilized to gauge critical thinking’s impact (e.g., sample size, mean value, or standard deviation). Articles that lacked specific measurement indicators for critical thinking and could not calculate the effect size were excluded.

Data coding design

In order to perform a meta-analysis, it is necessary to collect the most important information from the articles, codify that information’s properties, and convert descriptive data into quantitative data. Therefore, this study designed a data coding template (see Table 1 ). Ultimately, 16 coding fields were retained.

The designed data-coding template consisted of three pieces of information. Basic information about the papers was included in the descriptive information: the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper.

The variable information for the experimental design had three variables: the independent variable (instruction method), the dependent variable (critical thinking), and the moderating variable (learning stage, teaching type, intervention duration, learning scaffold, group size, measuring tool, and subject area). Depending on the topic of this study, the intervention strategy, as the independent variable, was coded into collaborative and non-collaborative problem-solving. The dependent variable, critical thinking, was coded as a cognitive skill and an attitudinal tendency. And seven moderating variables were created by grouping and combining the experimental design variables discovered within the 36 studies (see Table 1 ), where learning stages were encoded as higher education, high school, middle school, and primary school or lower; teaching types were encoded as mixed courses, integrated courses, and independent courses; intervention durations were encoded as 0–1 weeks, 1–4 weeks, 4–12 weeks, and more than 12 weeks; group sizes were encoded as 2–3 persons, 4–6 persons, 7–10 persons, and more than 10 persons; learning scaffolds were encoded as teacher-supported learning scaffold, technique-supported learning scaffold, and resource-supported learning scaffold; measuring tools were encoded as standardized measurement tools (e.g., WGCTA, CCTT, CCTST, and CCTDI) and self-adapting measurement tools (e.g., modified or made by researchers); and subject areas were encoded according to the specific subjects used in the 36 included studies.

The data information contained three metrics for measuring critical thinking: sample size, average value, and standard deviation. It is vital to remember that studies with various experimental designs frequently adopt various formulas to determine the effect size. And this paper used Morris’ proposed standardized mean difference (SMD) calculation formula ( 2008 , p. 369; see Supplementary Table S3 ).

Procedure for extracting and coding data

According to the data coding template (see Table 1 ), the 36 papers’ information was retrieved by two researchers, who then entered them into Excel (see Supplementary Table S1 ). The results of each study were extracted separately in the data extraction procedure if an article contained numerous studies on critical thinking, or if a study assessed different critical thinking dimensions. For instance, Tiwari et al. ( 2010 ) used four time points, which were viewed as numerous different studies, to examine the outcomes of critical thinking, and Chen ( 2013 ) included the two outcome variables of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, which were regarded as two studies. After discussion and negotiation during data extraction, the two researchers’ consistency test coefficients were roughly 93.27%. Supplementary Table S2 details the key characteristics of the 36 included articles with 79 effect quantities, including descriptive information (e.g., the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper), variable information (e.g., independent variables, dependent variables, and moderating variables), and data information (e.g., mean values, standard deviations, and sample size). Following that, testing for publication bias and heterogeneity was done on the sample data using the Rev-Man 5.4 software, and then the test results were used to conduct a meta-analysis.

Publication bias test

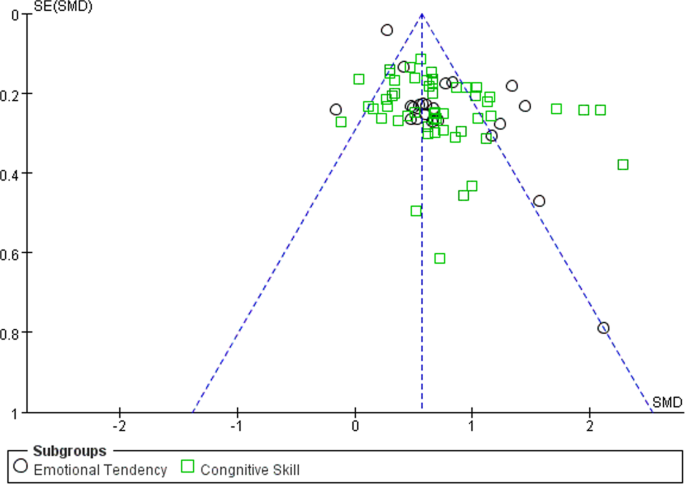

When the sample of studies included in a meta-analysis does not accurately reflect the general status of research on the relevant subject, publication bias is said to be exhibited in this research. The reliability and accuracy of the meta-analysis may be impacted by publication bias. Due to this, the meta-analysis needs to check the sample data for publication bias (Stewart et al., 2006 ). A popular method to check for publication bias is the funnel plot; and it is unlikely that there will be publishing bias when the data are equally dispersed on either side of the average effect size and targeted within the higher region. The data are equally dispersed within the higher portion of the efficient zone, consistent with the funnel plot connected with this analysis (see Fig. 2 ), indicating that publication bias is unlikely in this situation.

This funnel plot shows the result of publication bias of 79 effect quantities across 36 studies.

Heterogeneity test

To select the appropriate effect models for the meta-analysis, one might use the results of a heterogeneity test on the data effect sizes. In a meta-analysis, it is common practice to gauge the degree of data heterogeneity using the I 2 value, and I 2 ≥ 50% is typically understood to denote medium-high heterogeneity, which calls for the adoption of a random effect model; if not, a fixed effect model ought to be applied (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ). The findings of the heterogeneity test in this paper (see Table 2 ) revealed that I 2 was 86% and displayed significant heterogeneity ( P < 0.01). To ensure accuracy and reliability, the overall effect size ought to be calculated utilizing the random effect model.

The analysis of the overall effect size

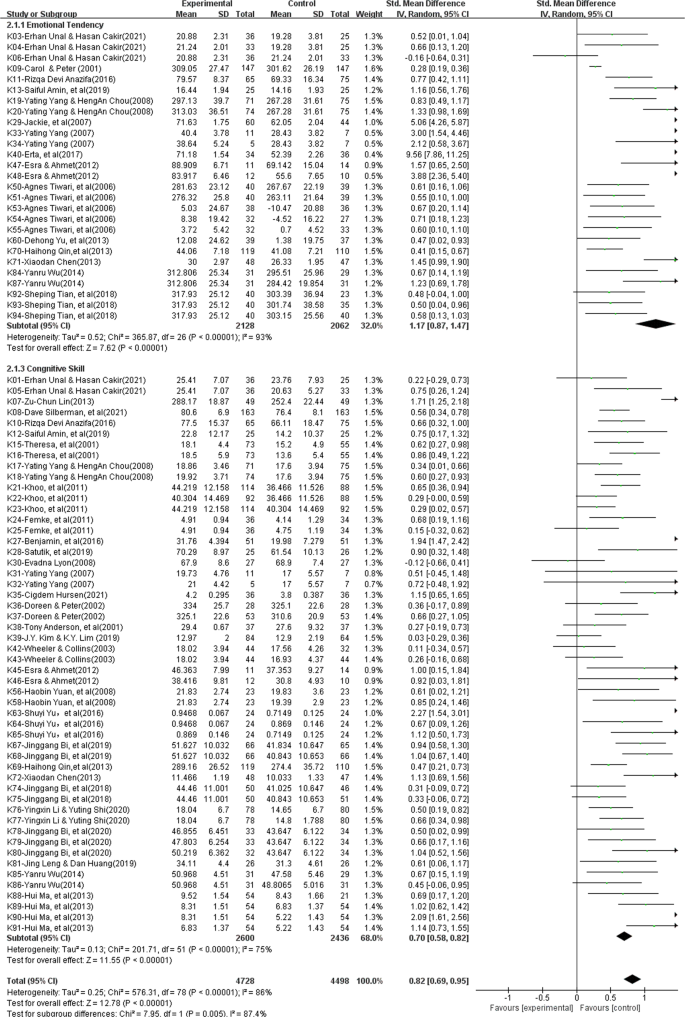

This meta-analysis utilized a random effect model to examine 79 effect quantities from 36 studies after eliminating heterogeneity. In accordance with Cohen’s criterion (Cohen, 1992 ), it is abundantly clear from the analysis results, which are shown in the forest plot of the overall effect (see Fig. 3 ), that the cumulative impact size of cooperative problem-solving is 0.82, which is statistically significant ( z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]), and can encourage learners to practice critical thinking.

This forest plot shows the analysis result of the overall effect size across 36 studies.

In addition, this study examined two distinct dimensions of critical thinking to better understand the precise contributions that collaborative problem-solving makes to the growth of critical thinking. The findings (see Table 3 ) indicate that collaborative problem-solving improves cognitive skills (ES = 0.70) and attitudinal tendency (ES = 1.17), with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.95, P < 0.01). Although collaborative problem-solving improves both dimensions of critical thinking, it is essential to point out that the improvements in students’ attitudinal tendency are much more pronounced and have a significant comprehensive effect (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]), whereas gains in learners’ cognitive skill are slightly improved and are just above average. (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

The analysis of moderator effect size

The whole forest plot’s 79 effect quantities underwent a two-tailed test, which revealed significant heterogeneity ( I 2 = 86%, z = 12.78, P < 0.01), indicating differences between various effect sizes that may have been influenced by moderating factors other than sampling error. Therefore, exploring possible moderating factors that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis, such as the learning stage, learning scaffold, teaching type, group size, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, in order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking. The findings (see Table 4 ) indicate that various moderating factors have advantageous effects on critical thinking. In this situation, the subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01), and teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05) are all significant moderators that can be applied to support the cultivation of critical thinking. However, since the learning stage and the measuring tools did not significantly differ among intergroup (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05, and chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05), we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These are the precise outcomes, as follows:

Various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively, without significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05). High school was first on the list of effect sizes (ES = 1.36, P < 0.01), then higher education (ES = 0.78, P < 0.01), and middle school (ES = 0.73, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the learning stage’s beneficial influence on cultivating learners’ critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is essential for cultivating critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Different teaching types had varying degrees of positive impact on critical thinking, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05). The effect size was ranked as follows: mixed courses (ES = 1.34, P < 0.01), integrated courses (ES = 0.81, P < 0.01), and independent courses (ES = 0.27, P < 0.01). These results indicate that the most effective approach to cultivate critical thinking utilizing collaborative problem solving is through the teaching type of mixed courses.

Various intervention durations significantly improved critical thinking, and there were significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01). The effect sizes related to this variable showed a tendency to increase with longer intervention durations. The improvement in critical thinking reached a significant level (ES = 0.85, P < 0.01) after more than 12 weeks of training. These findings indicate that the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated, with a longer intervention duration having a greater effect.

Different learning scaffolds influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01). The resource-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.69, P < 0.01) acquired a medium-to-higher level of impact, the technique-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.63, P < 0.01) also attained a medium-to-higher level of impact, and the teacher-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.92, P < 0.01) displayed a high level of significant impact. These results show that the learning scaffold with teacher support has the greatest impact on cultivating critical thinking.

Various group sizes influenced critical thinking positively, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05). Critical thinking showed a general declining trend with increasing group size. The overall effect size of 2–3 people in this situation was the biggest (ES = 0.99, P < 0.01), and when the group size was greater than 7 people, the improvement in critical thinking was at the lower-middle level (ES < 0.5, P < 0.01). These results show that the impact on critical thinking is positively connected with group size, and as group size grows, so does the overall impact.

Various measuring tools influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05). In this situation, the self-adapting measurement tools obtained an upper-medium level of effect (ES = 0.78), whereas the complete effect size of the standardized measurement tools was the largest, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 0.84, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the beneficial influence of the measuring tool on cultivating critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

Different subject areas had a greater impact on critical thinking, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05). Mathematics had the greatest overall impact, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 1.68, P < 0.01), followed by science (ES = 1.25, P < 0.01) and medical science (ES = 0.87, P < 0.01), both of which also achieved a significant level of effect. Programming technology was the least effective (ES = 0.39, P < 0.01), only having a medium-low degree of effect compared to education (ES = 0.72, P < 0.01) and other fields (such as language, art, and social sciences) (ES = 0.58, P < 0.01). These results suggest that scientific fields (e.g., mathematics, science) may be the most effective subject areas for cultivating critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

According to this meta-analysis, using collaborative problem-solving as an intervention strategy in critical thinking teaching has a considerable amount of impact on cultivating learners’ critical thinking as a whole and has a favorable promotional effect on the two dimensions of critical thinking. According to certain studies, collaborative problem solving, the most frequently used critical thinking teaching strategy in curriculum instruction can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking (e.g., Liang et al., 2017 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Cindy, 2004 ). This meta-analysis provides convergent data support for the above research views. Thus, the findings of this meta-analysis not only effectively address the first research query regarding the overall effect of cultivating critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills) utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving, but also enhance our confidence in cultivating critical thinking by using collaborative problem-solving intervention approach in the context of classroom teaching.

Furthermore, the associated improvements in attitudinal tendency are much stronger, but the corresponding improvements in cognitive skill are only marginally better. According to certain studies, cognitive skill differs from the attitudinal tendency in classroom instruction; the cultivation and development of the former as a key ability is a process of gradual accumulation, while the latter as an attitude is affected by the context of the teaching situation (e.g., a novel and exciting teaching approach, challenging and rewarding tasks) (Halpern, 2001 ; Wei and Hong, 2022 ). Collaborative problem-solving as a teaching approach is exciting and interesting, as well as rewarding and challenging; because it takes the learners as the focus and examines problems with poor structure in real situations, and it can inspire students to fully realize their potential for problem-solving, which will significantly improve their attitudinal tendency toward solving problems (Liu et al., 2020 ). Similar to how collaborative problem-solving influences attitudinal tendency, attitudinal tendency impacts cognitive skill when attempting to solve a problem (Liu et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ), and stronger attitudinal tendencies are associated with improved learning achievement and cognitive ability in students (Sison, 2008 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ). It can be seen that the two specific dimensions of critical thinking as well as critical thinking as a whole are affected by collaborative problem-solving, and this study illuminates the nuanced links between cognitive skills and attitudinal tendencies with regard to these two dimensions of critical thinking. To fully develop students’ capacity for critical thinking, future empirical research should pay closer attention to cognitive skills.

The moderating effects of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

In order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking, exploring possible moderating effects that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis. The findings show that the moderating factors, such as the teaching type, learning stage, group size, learning scaffold, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, could all support the cultivation of collaborative problem-solving in critical thinking. Among them, the effect size differences between the learning stage and measuring tool are not significant, which does not explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

In terms of the learning stage, various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively without significant intergroup differences, indicating that we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking.

Although high education accounts for 70.89% of all empirical studies performed by researchers, high school may be the appropriate learning stage to foster students’ critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving since it has the largest overall effect size. This phenomenon may be related to student’s cognitive development, which needs to be further studied in follow-up research.

With regard to teaching type, mixed course teaching may be the best teaching method to cultivate students’ critical thinking. Relevant studies have shown that in the actual teaching process if students are trained in thinking methods alone, the methods they learn are isolated and divorced from subject knowledge, which is not conducive to their transfer of thinking methods; therefore, if students’ thinking is trained only in subject teaching without systematic method training, it is challenging to apply to real-world circumstances (Ruggiero, 2012 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Teaching critical thinking as mixed course teaching in parallel to other subject teachings can achieve the best effect on learners’ critical thinking, and explicit critical thinking instruction is more effective than less explicit critical thinking instruction (Bensley and Spero, 2014 ).

In terms of the intervention duration, with longer intervention times, the overall effect size shows an upward tendency. Thus, the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated. Critical thinking, as a key competency for students in the 21st century, is difficult to get a meaningful improvement in a brief intervention duration. Instead, it could be developed over a lengthy period of time through consistent teaching and the progressive accumulation of knowledge (Halpern, 2001 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Therefore, future empirical studies ought to take these restrictions into account throughout a longer period of critical thinking instruction.

With regard to group size, a group size of 2–3 persons has the highest effect size, and the comprehensive effect size decreases with increasing group size in general. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a group composed of two to four members is most appropriate for collaborative learning (Schellens and Valcke, 2006 ). However, the meta-analysis results also indicate that once the group size exceeds 7 people, small groups cannot produce better interaction and performance than large groups. This may be because the learning scaffolds of technique support, resource support, and teacher support improve the frequency and effectiveness of interaction among group members, and a collaborative group with more members may increase the diversity of views, which is helpful to cultivate critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

With regard to the learning scaffold, the three different kinds of learning scaffolds can all enhance critical thinking. Among them, the teacher-supported learning scaffold has the largest overall effect size, demonstrating the interdependence of effective learning scaffolds and collaborative problem-solving. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a successful strategy is to encourage learners to collaborate, come up with solutions, and develop critical thinking skills by using learning scaffolds (Reiser, 2004 ; Xu et al., 2022 ); learning scaffolds can lower task complexity and unpleasant feelings while also enticing students to engage in learning activities (Wood et al., 2006 ); learning scaffolds are designed to assist students in using learning approaches more successfully to adapt the collaborative problem-solving process, and the teacher-supported learning scaffolds have the greatest influence on critical thinking in this process because they are more targeted, informative, and timely (Xu et al., 2022 ).

With respect to the measuring tool, despite the fact that standardized measurement tools (such as the WGCTA, CCTT, and CCTST) have been acknowledged as trustworthy and effective by worldwide experts, only 54.43% of the research included in this meta-analysis adopted them for assessment, and the results indicated no intergroup differences. These results suggest that not all teaching circumstances are appropriate for measuring critical thinking using standardized measurement tools. “The measuring tools for measuring thinking ability have limits in assessing learners in educational situations and should be adapted appropriately to accurately assess the changes in learners’ critical thinking.”, according to Simpson and Courtney ( 2002 , p. 91). As a result, in order to more fully and precisely gauge how learners’ critical thinking has evolved, we must properly modify standardized measuring tools based on collaborative problem-solving learning contexts.

With regard to the subject area, the comprehensive effect size of science departments (e.g., mathematics, science, medical science) is larger than that of language arts and social sciences. Some recent international education reforms have noted that critical thinking is a basic part of scientific literacy. Students with scientific literacy can prove the rationality of their judgment according to accurate evidence and reasonable standards when they face challenges or poorly structured problems (Kyndt et al., 2013 ), which makes critical thinking crucial for developing scientific understanding and applying this understanding to practical problem solving for problems related to science, technology, and society (Yore et al., 2007 ).

Suggestions for critical thinking teaching

Other than those stated in the discussion above, the following suggestions are offered for critical thinking instruction utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

First, teachers should put a special emphasis on the two core elements, which are collaboration and problem-solving, to design real problems based on collaborative situations. This meta-analysis provides evidence to support the view that collaborative problem-solving has a strong synergistic effect on promoting students’ critical thinking. Asking questions about real situations and allowing learners to take part in critical discussions on real problems during class instruction are key ways to teach critical thinking rather than simply reading speculative articles without practice (Mulnix, 2012 ). Furthermore, the improvement of students’ critical thinking is realized through cognitive conflict with other learners in the problem situation (Yang et al., 2008 ). Consequently, it is essential for teachers to put a special emphasis on the two core elements, which are collaboration and problem-solving, and design real problems and encourage students to discuss, negotiate, and argue based on collaborative problem-solving situations.

Second, teachers should design and implement mixed courses to cultivate learners’ critical thinking, utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving. Critical thinking can be taught through curriculum instruction (Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), with the goal of cultivating learners’ critical thinking for flexible transfer and application in real problem-solving situations. This meta-analysis shows that mixed course teaching has a highly substantial impact on the cultivation and promotion of learners’ critical thinking. Therefore, teachers should design and implement mixed course teaching with real collaborative problem-solving situations in combination with the knowledge content of specific disciplines in conventional teaching, teach methods and strategies of critical thinking based on poorly structured problems to help students master critical thinking, and provide practical activities in which students can interact with each other to develop knowledge construction and critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

Third, teachers should be more trained in critical thinking, particularly preservice teachers, and they also should be conscious of the ways in which teachers’ support for learning scaffolds can promote critical thinking. The learning scaffold supported by teachers had the greatest impact on learners’ critical thinking, in addition to being more directive, targeted, and timely (Wood et al., 2006 ). Critical thinking can only be effectively taught when teachers recognize the significance of critical thinking for students’ growth and use the proper approaches while designing instructional activities (Forawi, 2016 ). Therefore, with the intention of enabling teachers to create learning scaffolds to cultivate learners’ critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem solving, it is essential to concentrate on the teacher-supported learning scaffolds and enhance the instruction for teaching critical thinking to teachers, especially preservice teachers.

Implications and limitations

There are certain limitations in this meta-analysis, but future research can correct them. First, the search languages were restricted to English and Chinese, so it is possible that pertinent studies that were written in other languages were overlooked, resulting in an inadequate number of articles for review. Second, these data provided by the included studies are partially missing, such as whether teachers were trained in the theory and practice of critical thinking, the average age and gender of learners, and the differences in critical thinking among learners of various ages and genders. Third, as is typical for review articles, more studies were released while this meta-analysis was being done; therefore, it had a time limit. With the development of relevant research, future studies focusing on these issues are highly relevant and needed.

Conclusions

The subject of the magnitude of collaborative problem-solving’s impact on fostering students’ critical thinking, which received scant attention from other studies, was successfully addressed by this study. The question of the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking was addressed in this study, which addressed a topic that had gotten little attention in earlier research. The following conclusions can be made:

Regarding the results obtained, collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster learners’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]). With respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem-solving can significantly and effectively improve students’ attitudinal tendency, and the comprehensive effect is significant (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

As demonstrated by both the results and the discussion, there are varying degrees of beneficial effects on students’ critical thinking from all seven moderating factors, which were found across 36 studies. In this context, the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have a positive impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. Since the learning stage (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05) and measuring tools (chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05) did not demonstrate any significant intergroup differences, we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included within the article and its supplementary information files, and the supplementary information files are available in the Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IPFJO6 .

Bensley DA, Spero RA (2014) Improving critical thinking skills and meta-cognitive monitoring through direct infusion. Think Skills Creat 12:55–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2014.02.001

Article Google Scholar

Castle A (2009) Defining and assessing critical thinking skills for student radiographers. Radiography 15(1):70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2007.10.007

Chen XD (2013) An empirical study on the influence of PBL teaching model on critical thinking ability of non-English majors. J PLA Foreign Lang College 36 (04):68–72

Google Scholar

Cohen A (1992) Antecedents of organizational commitment across occupational groups: a meta-analysis. J Organ Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130602

Cooper H (2010) Research synthesis and meta-analysis: a step-by-step approach, 4th edn. Sage, London, England

Cindy HS (2004) Problem-based learning: what and how do students learn? Educ Psychol Rev 51(1):31–39

Duch BJ, Gron SD, Allen DE (2001) The power of problem-based learning: a practical “how to” for teaching undergraduate courses in any discipline. Stylus Educ Sci 2:190–198

Ennis RH (1989) Critical thinking and subject specificity: clarification and needed research. Educ Res 18(3):4–10. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x018003004

Facione PA (1990) Critical thinking: a statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Research findings and recommendations. Eric document reproduction service. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ed315423

Facione PA, Facione NC (1992) The California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory (CCTDI) and the CCTDI test manual. California Academic Press, Millbrae, CA

Forawi SA (2016) Standard-based science education and critical thinking. Think Skills Creat 20:52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.02.005

Halpern DF (2001) Assessing the effectiveness of critical thinking instruction. J Gen Educ 50(4):270–286. https://doi.org/10.2307/27797889

Hu WP, Liu J (2015) Cultivation of pupils’ thinking ability: a five-year follow-up study. Psychol Behav Res 13(05):648–654. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2015.05.010

Huber K (2016) Does college teach critical thinking? A meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res 86(2):431–468. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315605917

Kek MYCA, Huijser H (2011) The power of problem-based learning in developing critical thinking skills: preparing students for tomorrow’s digital futures in today’s classrooms. High Educ Res Dev 30(3):329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.501074

Kuncel NR (2011) Measurement and meaning of critical thinking (Research report for the NRC 21st Century Skills Workshop). National Research Council, Washington, DC

Kyndt E, Raes E, Lismont B, Timmers F, Cascallar E, Dochy F (2013) A meta-analysis of the effects of face-to-face cooperative learning. Do recent studies falsify or verify earlier findings? Educ Res Rev 10(2):133–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.02.002

Leng J, Lu XX (2020) Is critical thinking really teachable?—A meta-analysis based on 79 experimental or quasi experimental studies. Open Educ Res 26(06):110–118. https://doi.org/10.13966/j.cnki.kfjyyj.2020.06.011

Liang YZ, Zhu K, Zhao CL (2017) An empirical study on the depth of interaction promoted by collaborative problem solving learning activities. J E-educ Res 38(10):87–92. https://doi.org/10.13811/j.cnki.eer.2017.10.014

Lipsey M, Wilson D (2001) Practical meta-analysis. International Educational and Professional, London, pp. 92–160

Liu Z, Wu W, Jiang Q (2020) A study on the influence of problem based learning on college students’ critical thinking-based on a meta-analysis of 31 studies. Explor High Educ 03:43–49

Morris SB (2008) Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group designs. Organ Res Methods 11(2):364–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106291059

Article ADS Google Scholar

Mulnix JW (2012) Thinking critically about critical thinking. Educ Philos Theory 44(5):464–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2010.00673.x

Naber J, Wyatt TH (2014) The effect of reflective writing interventions on the critical thinking skills and dispositions of baccalaureate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 34(1):67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.04.002

National Research Council (2012) Education for life and work: developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Niu L, Behar HLS, Garvan CW (2013) Do instructional interventions influence college students’ critical thinking skills? A meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev 9(12):114–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2012.12.002

Peng ZM, Deng L (2017) Towards the core of education reform: cultivating critical thinking skills as the core of skills in the 21st century. Res Educ Dev 24:57–63. https://doi.org/10.14121/j.cnki.1008-3855.2017.24.011

Reiser BJ (2004) Scaffolding complex learning: the mechanisms of structuring and problematizing student work. J Learn Sci 13(3):273–304. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1303_2

Ruggiero VR (2012) The art of thinking: a guide to critical and creative thought, 4th edn. Harper Collins College Publishers, New York

Schellens T, Valcke M (2006) Fostering knowledge construction in university students through asynchronous discussion groups. Comput Educ 46(4):349–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2004.07.010

Sendag S, Odabasi HF (2009) Effects of an online problem based learning course on content knowledge acquisition and critical thinking skills. Comput Educ 53(1):132–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.01.008

Sison R (2008) Investigating Pair Programming in a Software Engineering Course in an Asian Setting. 2008 15th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference, pp. 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1109/APSEC.2008.61

Simpson E, Courtney M (2002) Critical thinking in nursing education: literature review. Mary Courtney 8(2):89–98

Stewart L, Tierney J, Burdett S (2006) Do systematic reviews based on individual patient data offer a means of circumventing biases associated with trial publications? Publication bias in meta-analysis. John Wiley and Sons Inc, New York, pp. 261–286

Tiwari A, Lai P, So M, Yuen K (2010) A comparison of the effects of problem-based learning and lecturing on the development of students’ critical thinking. Med Educ 40(6):547–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02481.x

Wood D, Bruner JS, Ross G (2006) The role of tutoring in problem solving. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 17(2):89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x

Wei T, Hong S (2022) The meaning and realization of teachable critical thinking. Educ Theory Practice 10:51–57

Xu EW, Wang W, Wang QX (2022) A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of programming teaching in promoting K-12 students’ computational thinking. Educ Inf Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11445-2

Yang YC, Newby T, Bill R (2008) Facilitating interactions through structured web-based bulletin boards: a quasi-experimental study on promoting learners’ critical thinking skills. Comput Educ 50(4):1572–1585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.04.006

Yore LD, Pimm D, Tuan HL (2007) The literacy component of mathematical and scientific literacy. Int J Sci Math Educ 5(4):559–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-007-9089-4

Zhang T, Zhang S, Gao QQ, Wang JH (2022) Research on the development of learners’ critical thinking in online peer review. Audio Visual Educ Res 6:53–60. https://doi.org/10.13811/j.cnki.eer.2022.06.08

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the graduate scientific research and innovation project of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region named “Research on in-depth learning of high school information technology courses for the cultivation of computing thinking” (No. XJ2022G190) and the independent innovation fund project for doctoral students of the College of Educational Science of Xinjiang Normal University named “Research on project-based teaching of high school information technology courses from the perspective of discipline core literacy” (No. XJNUJKYA2003).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Educational Science, Xinjiang Normal University, 830017, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China

Enwei Xu, Wei Wang & Qingxia Wang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Enwei Xu or Wei Wang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary tables, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Xu, E., Wang, W. & Wang, Q. The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis based on empirical literature. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 16 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01508-1

Download citation

Received : 07 August 2022

Accepted : 04 January 2023

Published : 11 January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01508-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Impacts of online collaborative learning on students’ intercultural communication apprehension and intercultural communicative competence.

- Hoa Thi Hoang Chau

- Hung Phu Bui

- Quynh Thi Huong Dinh

Education and Information Technologies (2024)

Exploring the effects of digital technology on deep learning: a meta-analysis

Sustainable electricity generation and farm-grid utilization from photovoltaic aquaculture: a bibliometric analysis.

- A. A. Amusa

- M. Alhassan

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Collaborative Problem Solving®: A New Approach to Teaching Children with Behavioural Challenges

What if you could learn a discipline approach that would reduce bullying, classroom disruption, teacher stress, office referrals, and other challenging behaviours while building a relationship with your students?

When discipline goes beyond your intuition and conventional approaches, learning Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) can be the winning tool that saves you from endless power struggles, disheartening moments, and lost instructional time. CPS can help restore a peaceful classroom and school environment that support kids’ and teachers’ mental health.

Collaborative Problem Solving is a revolutionary, evidence-based approach to helping children with behavioural challenges. CPS promotes the understanding that challenging kids lack the skill, not the will, to behave well—specifically skills related to problem-solving, flexibility, and frustration tolerance. Unlike traditional models of discipline, this approach avoids the use of power, control, and motivational procedures and instead focuses on teaching kids the skills they need to succeed. The Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) approach by Think: Kids is a program based in the Department of Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Boston MA.©

Our education system has seen many changes because of the Covid- 19 pandemic. The idea of remote or virtual learning, resisted by many parents and educators in 2019, is now generally accepted as having a role in the elementary and secondary school educational experience. However, educators have found that not being in the classroom regularly for two years has impacted learning for many children. Governments and school boards have put extra funding and staff in place to support kids who have lagged in their reading, writing, and math skills.

The pandemic has impacted family relationships as well. Stress within the family unit has increased dysregulation and challenging behaviour. Parents have had to make supervision arrangements, monitor learning at home, “teach” the use of technology for learning, and keep their children motivated along with their regular employment/professional responsibilities.

One of the things the pandemic has not changed is how society in general and many parents and educators view and respond to challenging behaviour (defiance, meltdowns, hitting, crying, non-compliance, unmet expectations, etc). Society has taught us that challenging behaviour is a choice made by the child to get something from adults or to get out of something they are expected to do. This is conventional wisdom. If this could be phrased as a philosophy, it would be “Children do well if they want to.” The discipline system in most schools is one that reflects this conventional wisdom. If teachers and principals believe kids choose to misbehave then they will use a program of rewards, punishment, and consequences to motivate them to comply. Consequences are then determined and imposed by adults to “teach” children a lesson and motivate them to change their behaviour. Unfortunately, the lesson they are teaching may be that adults are bigger and stronger. Our instructional practices aim to promote a growth mindset and success for all students, but our disciplinary system does just the opposite for many kids.

As a new teacher and new parent in the 1980s, I too believed that conventional approaches were the way to go to teach kids how to behave. I learned from my parents, other teachers, the media, and my instructors at teachers’ college that rewards, punishments, and consequences worked. I continued to believe in and use these operant approaches well into the 2000s. It wasn’t until 2006 that I was introduced to CPS by a grade one student and his mom. They introduced me to The Explosive Child, a book by Dr. Ross Green detailing his work with CPS. Shortly after this I was able to attend a CPS presentation with Dr. Stuart Ablon, the Director of Think:Kids. Dr. Ablon described the CPS model and how kids, families, and educators could benefit. From that point on I was a convert.

Conventional approaches (rewards, punishments, consequences) can accomplish some things although there are things they do not accomplish. Consequences can teach basic lessons like “put your hand up to speak, don’t take other people’s things, ask the teacher if you need to leave the classroom” and so on, to young children. Consequences do not teach complex thinking skills necessary to solve problems and meet expectations such as regular completion of homework, being on time for class, that things are not always “black or white,” and that school activities often require focus and avoiding distractions. Proponents of CPS feel conventional wisdom is almost always wrong.

Let’s look at behaviour from an unconventional perspective. The philosophy of CPS is that “Kids do well if they can.” If they are not doing well, something is getting in the way. Teachers and parents need to figure out what so they can help. If the kid could do well, he would do well. Doing well is preferable to doing poorly. This is unconventional thinking. When kids challenge, it is due to a lack of skill, not will. These lagging skills include cognitive flexibility, frustration tolerance, and problem solving.

Teachers can teach these cognitive skills, just as they teach reading, writing, and math, by following a similar process used to teach academic skills. First, an assessment is done to determine the problem(s) to be solved and to identify the lagging skills and challenging behaviours. The problems to be solved (PTBS) are the situations in which the child/youth demonstrates the challenging behaviours. The PTBS will be our focus for problem-solving, not the challenging behaviours.

A thorough assessment will help determine the appropriate response. Adults have three options for responding to challenging behaviour: Plan A, B, or C. Each option is useful depending on what the adult wants to accomplish. Plan A involves the adult imposing their will on the situation. Plan C is about dropping the expectation for now, not forever, and dealing with the problem at another time. Plan B is the collaborative problem-solving option where the child and the adult work together for a mutually agreed-upon solution.

Plan B involves three ingredients that must be done in the correct order and be given enough time to be completed effectively. The first ingredient of Plan B is Empathy. Here the adult tries to really understand the child’s concern or perspective about the problem. The focus is understanding, not blaming or finding fault with the young person’s response. The second ingredient involves getting the Adult Concern on the table. Almost all adult concerns are about health, safety, learning, or impact on others. The third ingredient is Collaboration where the adult and child generate, and agree on, ideas that address both concerns.

The good news is that a child’s skills are built naturally during the Plan B conversation because the focus is a real problem that is relevant to the child and the adult. Both individuals have a voice and ownership of the solution. There is more good news. Adults working with the child build their skills at the same time.

CPS is a trauma-informed approach. When teachers and parents do less Plan A this decreases the use of power and control, which can be re-traumatizing and do developmental damage. Doing more Plan B reduces the power difference, which helps to calm (regulate) the child and adult and create opportunities to build trusting relationships. Plan B gives the child more control while the adult is still responsible for the process. Building skills without overwhelming stress helps children meet expectations and confront future triggering situations safely.

School systems and educators have become more aware of the need to become more culturally responsive and support EDI (equity, diversity, and inclusion). CPS training programs provide opportunities for a deeper discussion involving equity and equality, implicit bias, providing a model to differentiate discipline, and guarding against unconscious assumptions about race, age, gender, etc.