- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

703k Accesses

275 Citations

85 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

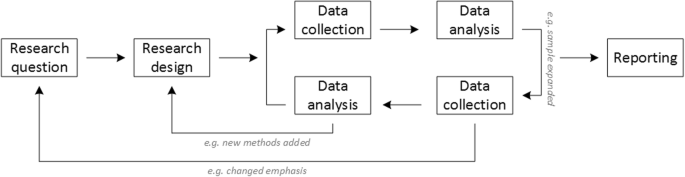

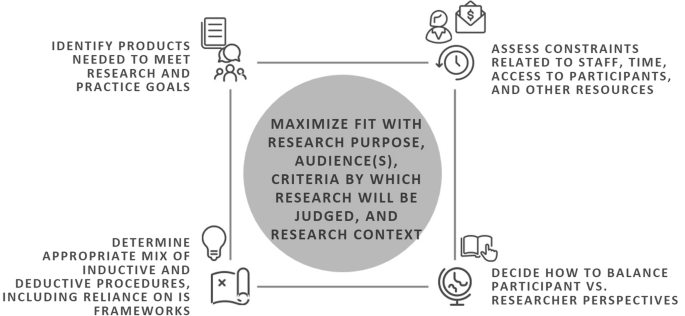

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

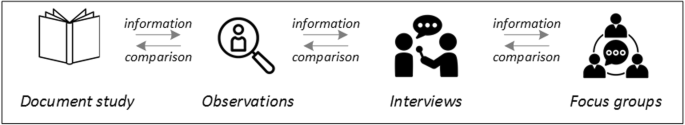

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

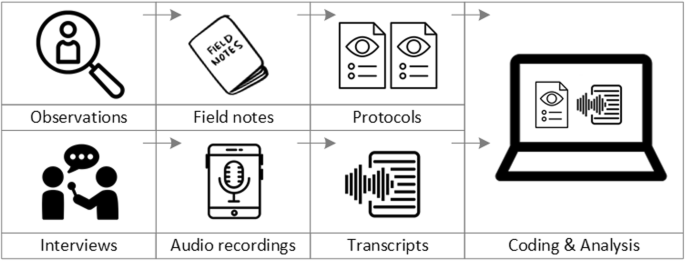

Data analysis

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

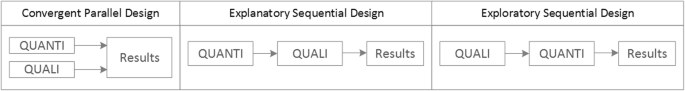

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to as “ purposive sampling” , in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to cover all variations that are expected to be of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.e. theoretical sampling) [ 14 , 20 ]. Other types of purposive sampling include (but are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ 2 ]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should check whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adapt and improve their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [ 14 ].

Good qualitative research is iterative in nature, i.e. it goes back and forth between data collection and analysis, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One example of this are pilot interviews, where different aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but also, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [ 19 ]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions work best, or which is the best length of an interview with patients who have trouble concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which can also be piloted.

Ideally, coding should be performed by at least two researchers, especially at the beginning of the coding process when a common approach must be defined, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a common meaning of individual codes must be established [ 23 ]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts can be coded independently by the coders and then compared and consolidated after regular discussions in the research team. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation , refers to the practice of checking back with study respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [ 14 , 27 ]. This can happen after data collection or analysis or when first results are available [ 23 ]. For example, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to clarify or elaborate on their responses [ 17 ]. Respondents’ feedback on these issues then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [ 27 ].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only as study participants (i.e. “members”, see above) but as consultants to and active participants in the broader research process [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders hold unique perspectives and experiences that add value beyond their own single story, making the research more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients alike [ 34 , 35 ]. Using the example of patients on or nearing dialysis, a recent scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [ 32 , 36 ]. In this sense, the involvement of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly being seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to assess qualitative research

The above overview does not include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a non-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based list of the quantitative criteria often applied to the assessment of qualitative research, as well as an explanation of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, it should not be assessed by how well it adheres to pre-determined and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative research does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be determined a priori [ 1 , 14 , 27 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the chosen methodology and the composition of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors argue that randomisation can be used in qualitative research, this is not commonly the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been convincingly established for qualitative research [ 13 , 27 ]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative impact of a too large sample size as well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting “ quiet, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals ” [ 17 ]. Qualitative studies do not use control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other “objectivity checks”

The concept of “interrater reliability” is sometimes used in qualitative research to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps between the two co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [ 23 ]. This means that these scores can be included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, but it is not a requirement. Relatedly, it is not relevant for the quality or “objectivity” of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the data. Experiences even show that it might be better to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [ 20 ]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can enhance trust when the interview takes place days or weeks later with the same researcher. Second, when the audio-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data analysis. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [ 18 ].

Not being quantitative research

Being qualitative research instead of quantitative research should not be used as an assessment criterion if it is used irrespectively of the research problem at hand. Similarly, qualitative research should not be required to be combined with quantitative research per se – unless mixed methods research is judged as inherently better than single-method research. In this case, the same criterion should be applied for quantitative studies without a qualitative component.

The main take-away points of this paper are summarised in Table 1 . We aimed to show that, if conducted well, qualitative research can answer specific research questions that cannot to be adequately answered using (only) quantitative designs. Seeing qualitative and quantitative methods as equal will help us become more aware and critical of the “fit” between the research problem and our chosen methods: I can conduct an RCT to determine the reasons for transportation delays of acute stroke patients – but should I? It also provides us with a greater range of tools to tackle a greater range of research problems more appropriately and successfully, filling in the blind spots on one half of the methodological spectrum to better address the whole complexity of neurological research and practice.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Endovascular treatment

Randomised Controlled Trial

Standard Operating Procedure

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

Philipsen, H., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek: nuttig, onmisbaar en uitdagend. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Qualitative research: useful, indispensable and challenging. In: Qualitative research: Practical methods for medical practice (pp. 5–12). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Chapter Google Scholar

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches . London: Sage.

Kelly, J., Dwyer, J., Willis, E., & Pekarsky, B. (2014). Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country aboriginal patient journeys. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22 (3), 109–113.

Article Google Scholar

Nilsen, P., Ståhl, C., Roback, K., & Cairney, P. (2013). Never the twain shall meet? - a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implementation Science, 8 (1), 1–12.

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., & Thornton, H. (2011). The 2011 Oxford CEBM evidence levels of evidence (introductory document) . Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/2011/06/2011-oxford-cebm-levels-evidence-introductory-document/ .

Eakin, J. M. (2016). Educating critical qualitative health researchers in the land of the randomized controlled trial. Qualitative Inquiry, 22 (2), 107–118.

May, A., & Mathijssen, J. (2015). Alternatieven voor RCT bij de evaluatie van effectiviteit van interventies!? Eindrapportage. In Alternatives for RCTs in the evaluation of effectiveness of interventions!? Final report .

Google Scholar

Berwick, D. M. (2008). The science of improvement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299 (10), 1182–1184.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Christ, T. W. (2014). Scientific-based research and randomized controlled trials, the “gold” standard? Alternative paradigms and mixed methodologies. Qualitative Inquiry, 20 (1), 72–80.

Lamont, T., Barber, N., Jd, P., Fulop, N., Garfield-Birkbeck, S., Lilford, R., Mear, L., Raine, R., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2016). New approaches to evaluating complex health and care systems. BMJ, 352:i154.

Drabble, S. J., & O’Cathain, A. (2015). Moving from Randomized Controlled Trials to Mixed Methods Intervention Evaluation. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 406–425). London: Oxford University Press.

Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E., & Stange, K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science : IS, 8 , 117.

Hak, T. (2007). Waarnemingsmethoden in kwalitatief onderzoek. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Observation methods in qualitative research] (pp. 13–25). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing, 6 (2), 36–40.

Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, L. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36 , 717–732.

Yanow, D. (2000). Conducting interpretive policy analysis (Vol. 47). Thousand Oaks: Sage University Papers Series on Qualitative Research Methods.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 , 63–75.

van der Geest, S. (2006). Participeren in ziekte en zorg: meer over kwalitatief onderzoek. Huisarts en Wetenschap, 49 (4), 283–287.

Hijmans, E., & Kuyper, M. (2007). Het halfopen interview als onderzoeksmethode. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [The half-open interview as research method (pp. 43–51). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Jansen, H. (2007). Systematiek en toepassing van de kwalitatieve survey. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Systematics and implementation of the qualitative survey (pp. 27–41). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Pv, R., & Peremans, L. (2007). Exploreren met focusgroepgesprekken: de ‘stem’ van de groep onder de loep. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Exploring with focus group conversations: the “voice” of the group under the magnifying glass (pp. 53–64). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41 (5), 545–547.

Boeije H: Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: Denken en doen, [Analysis in qualitative research: Thinking and doing] vol. Den Haag Boom Lemma uitgevers; 2012.

Hunter, A., & Brewer, J. (2015). Designing Multimethod Research. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 185–205). London: Oxford University Press.

Archibald, M. M., Radil, A. I., Zhang, X., & Hanson, W. E. (2015). Current mixed methods practices in qualitative research: A content analysis of leading journals. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14 (2), 5–33.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a Mixed Methods Design. In Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research . Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320 (7226), 50–52.

O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52 (4), 1893–1907.

Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24 (1), 9–18.

Marlett, N., Shklarov, S., Marshall, D., Santana, M. J., & Wasylak, T. (2015). Building new roles and relationships in research: A model of patient engagement research. Quality of Life Research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 24 (5), 1057–1067.

Demian, M. N., Lam, N. N., Mac-Way, F., Sapir-Pichhadze, R., & Fernandez, N. (2017). Opportunities for engaging patients in kidney research. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 4 , 2054358117703070–2054358117703070.

Noyes, J., McLaughlin, L., Morgan, K., Roberts, A., Stephens, M., Bourne, J., Houlston, M., Houlston, J., Thomas, S., Rhys, R. G., et al. (2019). Designing a co-productive study to overcome known methodological challenges in organ donation research with bereaved family members. Health Expectations . 22(4):824–35.

Piil, K., Jarden, M., & Pii, K. H. (2019). Research agenda for life-threatening cancer. European Journal Cancer Care (Engl), 28 (1), e12935.

Hofmann, D., Ibrahim, F., Rose, D., Scott, D. L., Cope, A., Wykes, T., & Lempp, H. (2015). Expectations of new treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: Developing a patient-generated questionnaire. Health Expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 18 (5), 995–1008.

Jun, M., Manns, B., Laupacis, A., Manns, L., Rehal, B., Crowe, S., & Hemmelgarn, B. R. (2015). Assessing the extent to which current clinical research is consistent with patient priorities: A scoping review using a case study in patients on or nearing dialysis. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 2 , 35.

Elsie Baker, S., & Edwards, R. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? In National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper . National Centre for Research Methods. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf .

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18 (2), 179–183.

Sim, J., Saunders, B., Waterfield, J., & Kingstone, T. (2018). Can sample size in qualitative research be determined a priori? International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21 (5), 619–634.

Download references

Acknowledgements

no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Neurology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 400, 69120, Heidelberg, Germany

Loraine Busetto, Wolfgang Wick & Christoph Gumbinger

Clinical Cooperation Unit Neuro-Oncology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany

Wolfgang Wick

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LB drafted the manuscript; WW and CG revised the manuscript; all authors approved the final versions.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Loraine Busetto .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Busetto, L., Wick, W. & Gumbinger, C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2 , 14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Download citation

Received : 30 January 2020

Accepted : 22 April 2020

Published : 27 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Mixed methods

- Quality assessment

Neurological Research and Practice

ISSN: 2524-3489

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- ESHRE Pages

- Mini-reviews

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Reasons to Publish

- Open Access

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Branded Books

- Journals Career Network

- About Human Reproduction

- About the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact ESHRE

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, when to use qualitative research, how to judge qualitative research, conclusions, authors' roles, conflict of interest.

- < Previous

Qualitative research methods: when to use them and how to judge them

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

K. Hammarberg, M. Kirkman, S. de Lacey, Qualitative research methods: when to use them and how to judge them, Human Reproduction , Volume 31, Issue 3, March 2016, Pages 498–501, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev334

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In March 2015, an impressive set of guidelines for best practice on how to incorporate psychosocial care in routine infertility care was published by the ESHRE Psychology and Counselling Guideline Development Group ( ESHRE Psychology and Counselling Guideline Development Group, 2015 ). The authors report that the guidelines are based on a comprehensive review of the literature and we congratulate them on their meticulous compilation of evidence into a clinically useful document. However, when we read the methodology section, we were baffled and disappointed to find that evidence from research using qualitative methods was not included in the formulation of the guidelines. Despite stating that ‘qualitative research has significant value to assess the lived experience of infertility and fertility treatment’, the group excluded this body of evidence because qualitative research is ‘not generally hypothesis-driven and not objective/neutral, as the researcher puts him/herself in the position of the participant to understand how the world is from the person's perspective’.

Qualitative and quantitative research methods are often juxtaposed as representing two different world views. In quantitative circles, qualitative research is commonly viewed with suspicion and considered lightweight because it involves small samples which may not be representative of the broader population, it is seen as not objective, and the results are assessed as biased by the researchers' own experiences or opinions. In qualitative circles, quantitative research can be dismissed as over-simplifying individual experience in the cause of generalisation, failing to acknowledge researcher biases and expectations in research design, and requiring guesswork to understand the human meaning of aggregate data.

As social scientists who investigate psychosocial aspects of human reproduction, we use qualitative and quantitative methods, separately or together, depending on the research question. The crucial part is to know when to use what method.

The peer-review process is a pillar of scientific publishing. One of the important roles of reviewers is to assess the scientific rigour of the studies from which authors draw their conclusions. If rigour is lacking, the paper should not be published. As with research using quantitative methods, research using qualitative methods is home to the good, the bad and the ugly. It is essential that reviewers know the difference. Rejection letters are hard to take but more often than not they are based on legitimate critique. However, from time to time it is obvious that the reviewer has little grasp of what constitutes rigour or quality in qualitative research. The first author (K.H.) recently submitted a paper that reported findings from a qualitative study about fertility-related knowledge and information-seeking behaviour among people of reproductive age. In the rejection letter one of the reviewers (not from Human Reproduction ) lamented, ‘Even for a qualitative study, I would expect that some form of confidence interval and paired t-tables analysis, etc. be used to analyse the significance of results'. This comment reveals the reviewer's inappropriate application to qualitative research of criteria relevant only to quantitative research.

In this commentary, we give illustrative examples of questions most appropriately answered using qualitative methods and provide general advice about how to appraise the scientific rigour of qualitative studies. We hope this will help the journal's reviewers and readers appreciate the legitimate place of qualitative research and ensure we do not throw the baby out with the bath water by excluding or rejecting papers simply because they report the results of qualitative studies.

In psychosocial research, ‘quantitative’ research methods are appropriate when ‘factual’ data are required to answer the research question; when general or probability information is sought on opinions, attitudes, views, beliefs or preferences; when variables can be isolated and defined; when variables can be linked to form hypotheses before data collection; and when the question or problem is known, clear and unambiguous. Quantitative methods can reveal, for example, what percentage of the population supports assisted conception, their distribution by age, marital status, residential area and so on, as well as changes from one survey to the next ( Kovacs et al. , 2012 ); the number of donors and donor siblings located by parents of donor-conceived children ( Freeman et al. , 2009 ); and the relationship between the attitude of donor-conceived people to learning of their donor insemination conception and their family ‘type’ (one or two parents, lesbian or heterosexual parents; Beeson et al. , 2011 ).

In contrast, ‘qualitative’ methods are used to answer questions about experience, meaning and perspective, most often from the standpoint of the participant. These data are usually not amenable to counting or measuring. Qualitative research techniques include ‘small-group discussions’ for investigating beliefs, attitudes and concepts of normative behaviour; ‘semi-structured interviews’, to seek views on a focused topic or, with key informants, for background information or an institutional perspective; ‘in-depth interviews’ to understand a condition, experience, or event from a personal perspective; and ‘analysis of texts and documents’, such as government reports, media articles, websites or diaries, to learn about distributed or private knowledge.

Qualitative methods have been used to reveal, for example, potential problems in implementing a proposed trial of elective single embryo transfer, where small-group discussions enabled staff to explain their own resistance, leading to an amended approach ( Porter and Bhattacharya, 2005 ). Small-group discussions among assisted reproductive technology (ART) counsellors were used to investigate how the welfare principle is interpreted and practised by health professionals who must apply it in ART ( de Lacey et al. , 2015 ). When legislative change meant that gamete donors could seek identifying details of people conceived from their gametes, parents needed advice on how best to tell their children. Small-group discussions were convened to ask adolescents (not known to be donor-conceived) to reflect on how they would prefer to be told ( Kirkman et al. , 2007 ).

When a population cannot be identified, such as anonymous sperm donors from the 1980s, a qualitative approach with wide publicity can reach people who do not usually volunteer for research and reveal (for example) their attitudes to proposed legislation to remove anonymity with retrospective effect ( Hammarberg et al. , 2014 ). When researchers invite people to talk about their reflections on experience, they can sometimes learn more than they set out to discover. In describing their responses to proposed legislative change, participants also talked about people conceived as a result of their donations, demonstrating various constructions and expectations of relationships ( Kirkman et al. , 2014 ).

Interviews with parents in lesbian-parented families generated insight into the diverse meanings of the sperm donor in the creation and life of the family ( Wyverkens et al. , 2014 ). Oral and written interviews also revealed the embarrassment and ambivalence surrounding sperm donors evident in participants in donor-assisted conception ( Kirkman, 2004 ). The way in which parents conceptualise unused embryos and why they discard rather than donate was explored and understood via in-depth interviews, showing how and why the meaning of those embryos changed with parenthood ( de Lacey, 2005 ). In-depth interviews were also used to establish the intricate understanding by embryo donors and recipients of the meaning of embryo donation and the families built as a result ( Goedeke et al. , 2015 ).

It is possible to combine quantitative and qualitative methods, although great care should be taken to ensure that the theory behind each method is compatible and that the methods are being used for appropriate reasons. The two methods can be used sequentially (first a quantitative then a qualitative study or vice versa), where the first approach is used to facilitate the design of the second; they can be used in parallel as different approaches to the same question; or a dominant method may be enriched with a small component of an alternative method (such as qualitative interviews ‘nested’ in a large survey). It is important to note that free text in surveys represents qualitative data but does not constitute qualitative research. Qualitative and quantitative methods may be used together for corroboration (hoping for similar outcomes from both methods), elaboration (using qualitative data to explain or interpret quantitative data, or to demonstrate how the quantitative findings apply in particular cases), complementarity (where the qualitative and quantitative results differ but generate complementary insights) or contradiction (where qualitative and quantitative data lead to different conclusions). Each has its advantages and challenges ( Brannen, 2005 ).

Qualitative research is gaining increased momentum in the clinical setting and carries different criteria for evaluating its rigour or quality. Quantitative studies generally involve the systematic collection of data about a phenomenon, using standardized measures and statistical analysis. In contrast, qualitative studies involve the systematic collection, organization, description and interpretation of textual, verbal or visual data. The particular approach taken determines to a certain extent the criteria used for judging the quality of the report. However, research using qualitative methods can be evaluated ( Dixon-Woods et al. , 2006 ; Young et al. , 2014 ) and there are some generic guidelines for assessing qualitative research ( Kitto et al. , 2008 ).

Although the terms ‘reliability’ and ‘validity’ are contentious among qualitative researchers ( Lincoln and Guba, 1985 ) with some preferring ‘verification’, research integrity and robustness are as important in qualitative studies as they are in other forms of research. It is widely accepted that qualitative research should be ethical, important, intelligibly described, and use appropriate and rigorous methods ( Cohen and Crabtree, 2008 ). In research investigating data that can be counted or measured, replicability is essential. When other kinds of data are gathered in order to answer questions of personal or social meaning, we need to be able to capture real-life experiences, which cannot be identical from one person to the next. Furthermore, meaning is culturally determined and subject to evolutionary change. The way of explaining a phenomenon—such as what it means to use donated gametes—will vary, for example, according to the cultural significance of ‘blood’ or genes, interpretations of marital infidelity and religious constructs of sexual relationships and families. Culture may apply to a country, a community, or other actual or virtual group, and a person may be engaged at various levels of culture. In identifying meaning for members of a particular group, consistency may indeed be found from one research project to another. However, individuals within a cultural group may present different experiences and perceptions or transgress cultural expectations. That does not make them ‘wrong’ or invalidate the research. Rather, it offers insight into diversity and adds a piece to the puzzle to which other researchers also contribute.

In qualitative research the objective stance is obsolete, the researcher is the instrument, and ‘subjects’ become ‘participants’ who may contribute to data interpretation and analysis ( Denzin and Lincoln, 1998 ). Qualitative researchers defend the integrity of their work by different means: trustworthiness, credibility, applicability and consistency are the evaluative criteria ( Leininger, 1994 ).

Trustworthiness

A report of a qualitative study should contain the same robust procedural description as any other study. The purpose of the research, how it was conducted, procedural decisions, and details of data generation and management should be transparent and explicit. A reviewer should be able to follow the progression of events and decisions and understand their logic because there is adequate description, explanation and justification of the methodology and methods ( Kitto et al. , 2008 )

Credibility

Credibility is the criterion for evaluating the truth value or internal validity of qualitative research. A qualitative study is credible when its results, presented with adequate descriptions of context, are recognizable to people who share the experience and those who care for or treat them. As the instrument in qualitative research, the researcher defends its credibility through practices such as reflexivity (reflection on the influence of the researcher on the research), triangulation (where appropriate, answering the research question in several ways, such as through interviews, observation and documentary analysis) and substantial description of the interpretation process; verbatim quotations from the data are supplied to illustrate and support their interpretations ( Sandelowski, 1986 ). Where excerpts of data and interpretations are incongruent, the credibility of the study is in doubt.

Applicability

Applicability, or transferability of the research findings, is the criterion for evaluating external validity. A study is considered to meet the criterion of applicability when its findings can fit into contexts outside the study situation and when clinicians and researchers view the findings as meaningful and applicable in their own experiences.

Larger sample sizes do not produce greater applicability. Depth may be sacrificed to breadth or there may be too much data for adequate analysis. Sample sizes in qualitative research are typically small. The term ‘saturation’ is often used in reference to decisions about sample size in research using qualitative methods. Emerging from grounded theory, where filling theoretical categories is considered essential to the robustness of the developing theory, data saturation has been expanded to describe a situation where data tend towards repetition or where data cease to offer new directions and raise new questions ( Charmaz, 2005 ). However, the legitimacy of saturation as a generic marker of sampling adequacy has been questioned ( O'Reilly and Parker, 2013 ). Caution must be exercised to ensure that a commitment to saturation does not assume an ‘essence’ of an experience in which limited diversity is anticipated; each account is likely to be subtly different and each ‘sample’ will contribute to knowledge without telling the whole story. Increasingly, it is expected that researchers will report the kind of saturation they have applied and their criteria for recognising its achievement; an assessor will need to judge whether the choice is appropriate and consistent with the theoretical context within which the research has been conducted.

Sampling strategies are usually purposive, convenient, theoretical or snowballed. Maximum variation sampling may be used to seek representation of diverse perspectives on the topic. Homogeneous sampling may be used to recruit a group of participants with specified criteria. The threat of bias is irrelevant; participants are recruited and selected specifically because they can illuminate the phenomenon being studied. Rather than being predetermined by statistical power analysis, qualitative study samples are dependent on the nature of the data, the availability of participants and where those data take the investigator. Multiple data collections may also take place to obtain maximum insight into sensitive topics. For instance, the question of how decisions are made for embryo disposition may involve sampling within the patient group as well as from scientists, clinicians, counsellors and clinic administrators.

Consistency

Consistency, or dependability of the results, is the criterion for assessing reliability. This does not mean that the same result would necessarily be found in other contexts but that, given the same data, other researchers would find similar patterns. Researchers often seek maximum variation in the experience of a phenomenon, not only to illuminate it but also to discourage fulfilment of limited researcher expectations (for example, negative cases or instances that do not fit the emerging interpretation or theory should be actively sought and explored). Qualitative researchers sometimes describe the processes by which verification of the theoretical findings by another team member takes place ( Morse and Richards, 2002 ).

Research that uses qualitative methods is not, as it seems sometimes to be represented, the easy option, nor is it a collation of anecdotes. It usually involves a complex theoretical or philosophical framework. Rigorous analysis is conducted without the aid of straightforward mathematical rules. Researchers must demonstrate the validity of their analysis and conclusions, resulting in longer papers and occasional frustration with the word limits of appropriate journals. Nevertheless, we need the different kinds of evidence that is generated by qualitative methods. The experience of health, illness and medical intervention cannot always be counted and measured; researchers need to understand what they mean to individuals and groups. Knowledge gained from qualitative research methods can inform clinical practice, indicate how to support people living with chronic conditions and contribute to community education and awareness about people who are (for example) experiencing infertility or using assisted conception.

Each author drafted a section of the manuscript and the manuscript as a whole was reviewed and revised by all authors in consultation.

No external funding was either sought or obtained for this study.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Beeson D , Jennings P , Kramer W . Offspring searching for their sperm donors: how family types shape the process . Hum Reprod 2011 ; 26 : 2415 – 2424 .

Google Scholar

Brannen J . Mixing methods: the entry of qualitative and quantitative approaches into the research process . Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005 ; 8 : 173 – 184 .

Charmaz K . Grounded Theory in the 21st century; applications for advancing social justice studies . In: Denzin NK , Lincoln YS (eds). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research . California : Sage Publications Inc. , 2005 .

Google Preview

Cohen D , Crabtree B . Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations . Ann Fam Med 2008 ; 6 : 331 – 339 .

de Lacey S . Parent identity and ‘virtual’ children: why patients discard rather than donate unused embryos . Hum Reprod 2005 ; 20 : 1661 – 1669 .

de Lacey SL , Peterson K , McMillan J . Child interests in assisted reproductive technology: how is the welfare principle applied in practice? Hum Reprod 2015 ; 30 : 616 – 624 .

Denzin N , Lincoln Y . Entering the field of qualitative research . In: Denzin NK , Lincoln YS (eds). The Landscape of Qualitative Research: Theories and Issues . Thousand Oaks : Sage , 1998 , 1 – 34 .

Dixon-Woods M , Bonas S , Booth A , Jones DR , Miller T , Shaw RL , Smith JA , Young B . How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective . Qual Res 2006 ; 6 : 27 – 44 .

ESHRE Psychology and Counselling Guideline Development Group . Routine Psychosocial Care in Infertility and Medically Assisted Reproduction: A Guide for Fertility Staff , 2015 . http://www.eshre.eu/Guidelines-and-Legal/Guidelines/Psychosocial-care-guideline.aspx .

Freeman T , Jadva V , Kramer W , Golombok S . Gamete donation: parents' experiences of searching for their child's donor siblings or donor . Hum Reprod 2009 ; 24 : 505 – 516 .

Goedeke S , Daniels K , Thorpe M , Du Preez E . Building extended families through embryo donation: the experiences of donors and recipients . Hum Reprod 2015 ; 30 : 2340 – 2350 .

Hammarberg K , Johnson L , Bourne K , Fisher J , Kirkman M . Proposed legislative change mandating retrospective release of identifying information: consultation with donors and Government response . Hum Reprod 2014 ; 29 : 286 – 292 .

Kirkman M . Saviours and satyrs: ambivalence in narrative meanings of sperm provision . Cult Health Sex 2004 ; 6 : 319 – 336 .

Kirkman M , Rosenthal D , Johnson L . Families working it out: adolescents' views on communicating about donor-assisted conception . Hum Reprod 2007 ; 22 : 2318 – 2324 .

Kirkman M , Bourne K , Fisher J , Johnson L , Hammarberg K . Gamete donors' expectations and experiences of contact with their donor offspring . Hum Reprod 2014 ; 29 : 731 – 738 .

Kitto S , Chesters J , Grbich C . Quality in qualitative research . Med J Aust 2008 ; 188 : 243 – 246 .

Kovacs GT , Morgan G , Levine M , McCrann J . The Australian community overwhelmingly approves IVF to treat subfertility, with increasing support over three decades . Aust N Z J Obstetr Gynaecol 2012 ; 52 : 302 – 304 .

Leininger M . Evaluation criteria and critique of qualitative research studies . In: Morse J (ed). Critical Issues in Qualitative Research Methods . Thousand Oaks : Sage , 1994 , 95 – 115 .

Lincoln YS , Guba EG . Naturalistic Inquiry . Newbury Park, CA : Sage Publications , 1985 .

Morse J , Richards L . Readme First for a Users Guide to Qualitative Methods . Thousand Oaks : Sage , 2002 .

O'Reilly M , Parker N . ‘Unsatisfactory saturation’: a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research . Qual Res 2013 ; 13 : 190 – 197 .

Porter M , Bhattacharya S . Investigation of staff and patients' opinions of a proposed trial of elective single embryo transfer . Hum Reprod 2005 ; 20 : 2523 – 2530 .

Sandelowski M . The problem of rigor in qualitative research . Adv Nurs Sci 1986 ; 8 : 27 – 37 .

Wyverkens E , Provoost V , Ravelingien A , De Sutter P , Pennings G , Buysse A . Beyond sperm cells: a qualitative study on constructed meanings of the sperm donor in lesbian families . Hum Reprod 2014 ; 29 : 1248 – 1254 .

Young K , Fisher J , Kirkman M . Women's experiences of endometriosis: a systematic review of qualitative research . J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2014 ; 41 : 225 – 234 .

- conflict of interest

- credibility

- qualitative research

- quantitative methods

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2350

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Open access

- Published: 29 June 2021

Pragmatic approaches to analyzing qualitative data for implementation science: an introduction

- Shoba Ramanadhan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0650-9433 1 ,

- Anna C. Revette 2 ,

- Rebekka M. Lee 1 &

- Emma L. Aveling 3

Implementation Science Communications volume 2 , Article number: 70 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

36k Accesses

66 Citations

46 Altmetric

Metrics details

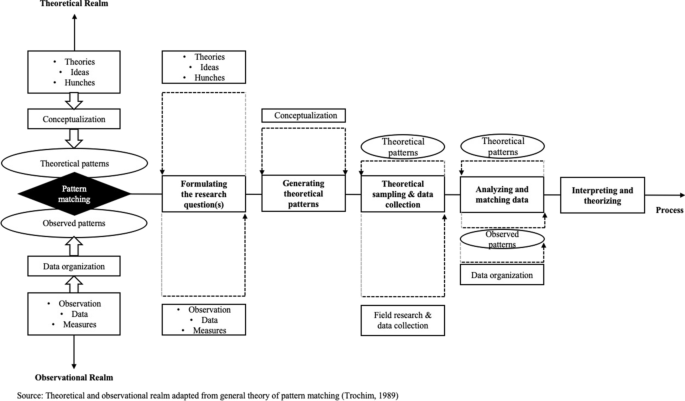

Qualitative methods are critical for implementation science as they generate opportunities to examine complexity and include a diversity of perspectives. However, it can be a challenge to identify the approach that will provide the best fit for achieving a given set of practice-driven research needs. After all, implementation scientists must find a balance between speed and rigor, reliance on existing frameworks and new discoveries, and inclusion of insider and outsider perspectives. This paper offers guidance on taking a pragmatic approach to analysis, which entails strategically combining and borrowing from established qualitative approaches to meet a study’s needs, typically with guidance from an existing framework and with explicit research and practice change goals.

Section 1 offers a series of practical questions to guide the development of a pragmatic analytic approach. These include examining the balance of inductive and deductive procedures, the extent to which insider or outsider perspectives are privileged, study requirements related to data and products that support scientific advancement and practice change, and strategic resource allocation. This is followed by an introduction to three approaches commonly considered for implementation science projects: grounded theory, framework analysis, and interpretive phenomenological analysis, highlighting core analytic procedures that may be borrowed for a pragmatic approach. Section 2 addresses opportunities to ensure and communicate rigor of pragmatic analytic approaches. Section 3 provides an illustrative example from the team’s work, highlighting how a pragmatic analytic approach was designed and executed and the diversity of research and practice products generated.

As qualitative inquiry gains prominence in implementation science, it is critical to take advantage of qualitative methods’ diversity and flexibility. This paper furthers the conversation regarding how to strategically mix and match components of established qualitative approaches to meet the analytic needs of implementation science projects, thereby supporting high-impact research and improved opportunities to create practice change.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

Qualitative methods are increasingly being used in implementation science, yet many researchers are new to these methods or unaware of the flexibility afforded by applied qualitative research.

Implementation scientists can benefit from guidance on creating a pragmatic approach to analysis, which includes the strategic combining and borrowing from established approaches to meet a given study’s needs, typically with guidance from an implementation science framework and explicit research and practice change goals.

Through practical questions and examples, we provide guidance for using pragmatic analytic approaches to meet the needs and constraints of implementation science projects while maintaining and communicating the work’s rigor.

Implementation science (IS) is truly pragmatic at its core, answering questions about how existing evidence can be best translated into practice to accelerate impact on population health and health equity. Qualitative methods are critical to support this endeavor as they support the examination of the dynamic context and systems into which evidence-based interventions (EBIs) are integrated — addressing the “hows and whys” of implementation [ 1 ]. Numerous IS frameworks highlight the complexity of the systems in which implementation efforts occur and the uncertainty regarding how various determinants interact to produce multi-level outcomes [ 2 ]. With that lens, it is unsurprising that diverse qualitative methodologies are receiving increasing attention in IS as they allow for an in-depth understanding of complex processes and interactions [ 1 , 3 , 4 ]. Given the wide variety of possible analytic approaches and techniques, an important question is which analytic approach best fits a given set of practice-driven research needs. Thoughtful design is needed to align research questions and objectives, the nature of the subject matter, the overall approach, the methods (specific tools and techniques used to achieve research goals, including data collection procedures), and the analytic strategies (including procedures used for exploring and interpreting data) [ 5 , 6 ]. Achieving this kind of alignment is often described as “fit,” “methodological integrity,” or “internal coherence” [ 3 , 7 , 8 ]. Tailoring research designs to the unique constellation of these considerations in a given study may also require creative adaptation or innovation of analytic procedures [ 7 ]. Yet, for IS researchers newer to qualitative approaches, a lack of understanding of the range of relevant options may limit their ability to effectively connect qualitative approaches and research goals.

For IS studies, several factors further complicate the selection of analytic approaches. First, there is a tension between the speed with which IS must move to be relevant and the need to conduct rigorous research. Second, though qualitative research is often associated with attempts to generate new theories, qualitative IS studies’ goals may also include elaborating conceptual definitions, creating classifications or typologies, and examining mechanisms and associations [ 9 ]. Given the wealth of existing IS frameworks and models, covering determinants, processes, and outcomes [ 10 ], IS studies often focus on extending or applying existing frameworks. Third, as an applied field, IS work usually entails integrating different kinds of “insider” and “outsider” expertise to support implementation or practice change [ 11 ]. Fourth, diverse traditions have contributed to the new field of IS, including agriculture, operations research, public health, medicine, anthropology, sociology, and more [ 12 ]. The diversity of disciplines among IS researchers can bring a wealth of complementary perspectives but may also pose challenges in communicating about research processes.

Pragmatic approaches to qualitative analysis are likely valuable for IS researchers yet have not received enough attention in the IS literature to support researchers in using them confidently. By pragmatic approaches, we mean strategic combining and borrowing from established qualitative approaches to meet the needs of a given IS study, often with guidance from an IS framework and with clear research and practice change goals. Pragmatic approaches are not new, but they receive less attention in qualitative research overall and are not always clearly explicated in the literature [ 9 ]. Part of the challenge in using pragmatic approaches is the lack of guidance on how to mix and match components of established approaches in a coherent, credible manner.