- Main Library

- Digital Fabrication Lab

- Data Visualization Lab

- Business Learning Center

- Klai Juba Wald Architectural Studies Library

- NDSU Nursing at Sanford Health Library

- Research Assistance

- Special Collections

- Digital Collections

- Collection Development Policy

- Course Reserves

- Request Library Instruction

- Main Library Services

- Alumni & Community

- Academic Support Services in the Library

- Libraries Resources for Employees

- Book Equipment or Study Rooms

- Librarians by Academic Subject

- Germans from Russia Heritage Collection

- NDSU Archives

- Mission, Vision, and Strategic Plan 2022-2024

- Staff Directory

- Floor Plans

- The Libraries Magazine

- Accommodations for People with Disabilities

- Annual Report

- Donate to the Libraries

- Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

- Faculty Senate Library Committee

- Undergraduate Research Award

What is an original research article?

An original research article is a report of research activity that is written by the researchers who conducted the research or experiment. Original research articles may also be referred to as: “primary research articles” or “primary scientific literature.” In science courses, instructors may also refer to these as “peer-reviewed articles” or “refereed articles.”

Original research articles in the sciences have a specific purpose, follow a scientific article format, are peer reviewed, and published in academic journals.

Identifying Original Research: What to Look For

An "original research article" is an article that is reporting original research about new data or theories that have not been previously published. That might be the results of new experiments, or newly derived models or simulations. The article will include a detailed description of the methods used to produce them, so that other researchers can verify them. This description is often found in a section called "methods" or "materials and methods" or similar. Similarly, the results will generally be described in great detail, often in a section called "results."

Since the original research article is reporting the results of new research, the authors should be the scientists who conducted that research. They will have expertise in the field, and will usually be employed by a university or research lab.

In comparison, a newspaper or magazine article (such as in The New York Times or National Geographic ) will usually be written by a journalist reporting on the actions of someone else.

An original research article will be written by and for scientists who study related topics. As such, the article should use precise, technical language to ensure that other researchers have an exact understanding of what was done, how to do it, and why it matters. There will be plentiful citations to previous work, helping place the research article in a broader context. The article will be published in an academic journal, follow a scientific format, and undergo peer-review.

Original research articles in the sciences follow the scientific format. ( This tutorial from North Carolina State University illustrates some of the key features of this format.)

Look for signs of this format in the subject headings or subsections of the article. You should see the following:

Scientific research that is published in academic journals undergoes a process called "peer review."

The peer review process goes like this:

- A researcher writes a paper and sends it in to an academic journal, where it is read by an editor

- The editor then sends the article to other scientists who study similar topics, who can best evaluate the article

- The scientists/reviewers examine the article's research methodology, reasoning, originality, and sginificance

- The scientists/reviewers then make suggestions and comments to impove the paper

- The original author is then given these suggestions and comments, and makes changes as needed

- This process repeats until everyone is satisfied and the article can be published within the academic journal

For more details about this process see the Peer Reviewed Publications guide.

This journal article is an example. It was published in the journal Royal Society Open Science in 2015. Clicking on the button that says "Review History" will show the comments by the editors, reviewers and the author as it went through the peer review process. The "About Us" menu provides details about this journal; "About the journal" under that tab includes the statement that the journal is peer reviewed.

Review articles

There are a variety of article types published in academic, peer-reviewed journals, but the two most common are original research articles and review articles . They can look very similar, but have different purposes and structures.

Like original research articles, review articles are aimed at scientists and undergo peer-review. Review articles often even have “abstract,” “introduction,” and “reference” sections. However, they will not (generally) have a “methods” or “results” section because they are not reporting new data or theories. Instead, they review the current state of knowledge on a topic.

Press releases, newspaper or magazine articles

These won't be in a formal scientific format or be peer reviewed. The author will usually be a journalist, and the audience will be the general public. Since most readers are not interested in the precise details of the research, the language will usually be nontechnical and broad. Citations will be rare or nonexistent.

Tips for Finding Original research Articles

Search for articles in one of the library databases recommend for your subject area . If you are using Google, try searching in Google Scholar instead and you will get results that are more likely to be original research articles than what will come up in a regular Google search!

For tips on using library databases to find articles, see our Library DIY guides .

Tips for Finding the Source of a News Report about Science

If you've seen or heard a report about a new scientific finding or claim, these tips can help you find the original source:

- Often, the report will mention where the original research was published; look for sentences like "In an article published yesterday in the journal Nature ..." You can use this to find the issue of the journal where the research was published, and look at the table of contents to find the original article.

- The report will often name the researchers involved. You can search relevant databases for their name and the topic of the report to find the original research that way.

- Sometimes you may have to go through multiple articles to find the original source. For example, a video or blog post may be based on a newspaper article, which in turn is reporting on a scientific discovery published in another journal; be sure to find the original research article.

- Don't be afraid to ask a librarian for help!

Search The Site

Find Your Librarian

Phone: Circulation: (701) 231-8888 Reference: (701) 231-8888 Administration: (701) 231-8753

Email: Administration InterLibrary Loan (ILL)

- Online Services

- Phone/Email Directory

- Registration And Records

- Government Information

- Library DIY

- Subject and Course Guides

- Special Topics

- Collection Highlights

- Digital Horizons

- NDSU Repository (IR)

- Libraries Hours

- News & Events

- Privacy Policy

Home » Original Research – Definition, Examples, Guide

Original Research – Definition, Examples, Guide

Table of Contents

Original Research

Definition:

Original research refers to a type of research that involves the collection and analysis of new and original data to answer a specific research question or to test a hypothesis. This type of research is conducted by researchers who aim to generate new knowledge or add to the existing body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline.

Types of Original Research

There are several types of original research that researchers can conduct depending on their research question and the nature of the data they are collecting. Some of the most common types of original research include:

Basic Research

This type of research is conducted to expand scientific knowledge and to create new theories, models, or frameworks. Basic research often involves testing hypotheses and conducting experiments or observational studies.

Applied Research

This type of research is conducted to solve practical problems or to develop new products or technologies. Applied research often involves the application of basic research findings to real-world problems.

Exploratory Research

This type of research is conducted to gather preliminary data or to identify research questions that need further investigation. Exploratory research often involves collecting qualitative data through interviews, focus groups, or observations.

Descriptive Research

This type of research is conducted to describe the characteristics or behaviors of a population or a phenomenon. Descriptive research often involves collecting quantitative data through surveys, questionnaires, or other standardized instruments.

Correlational Research

This type of research is conducted to determine the relationship between two or more variables. Correlational research often involves collecting quantitative data and using statistical analyses to identify correlations between variables.

Experimental Research

This type of research is conducted to test cause-and-effect relationships between variables. Experimental research often involves manipulating one or more variables and observing the effect on an outcome variable.

Longitudinal Research

This type of research is conducted over an extended period of time to study changes in behavior or outcomes over time. Longitudinal research often involves collecting data at multiple time points.

Original Research Methods

Original research can involve various methods depending on the research question, the nature of the data, and the discipline or field of study. However, some common methods used in original research include:

This involves the manipulation of one or more variables to test a hypothesis. Experimental research is commonly used in the natural sciences, such as physics, chemistry, and biology, but can also be used in social sciences, such as psychology.

Observational Research

This involves the collection of data by observing and recording behaviors or events without manipulation. Observational research can be conducted in the natural setting of the behavior or in a laboratory setting.

Survey Research

This involves the collection of data from a sample of participants using questionnaires or interviews. Survey research is commonly used in social sciences, such as sociology, political science, and economics.

Case Study Research

This involves the in-depth analysis of a single case, such as an individual, organization, or event. Case study research is commonly used in social sciences and business studies.

Qualitative research

This involves the collection and analysis of non-numerical data, such as interviews, focus groups, and observation notes. Qualitative research is commonly used in social sciences, such as anthropology, sociology, and psychology.

Quantitative research

This involves the collection and analysis of numerical data using statistical methods. Quantitative research is commonly used in natural sciences, such as physics, chemistry, and biology, as well as in social sciences, such as psychology and economics.

Researchers may also use a combination of these methods in their original research depending on their research question and the nature of their data.

Data Collection Methods

There are several data collection methods that researchers can use in original research, depending on the nature of the research question and the type of data that needs to be collected. Some of the most common data collection methods include:

- Surveys : Surveys involve asking participants to respond to a series of questions about their attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, or experiences. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through email, or online.

- Interviews : Interviews involve asking participants open-ended questions about their experiences, beliefs, or behaviors. Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

- Observations : Observations involve observing and recording participants’ behaviors or interactions in a natural or laboratory setting. Observations can be conducted using structured or unstructured methods.

- Experiments : Experiments involve manipulating one or more variables and observing the effect on an outcome variable. Experiments can be conducted in a laboratory or in the natural environment.

- Case studies: Case studies involve conducting an in-depth analysis of a single case, such as an individual, organization, or event. Case studies can involve the collection of qualitative or quantitative data.

- Focus groups: Focus groups involve bringing together a small group of participants to discuss a specific topic or issue. Focus groups can be conducted in person or online.

- Document analysis: Document analysis involves collecting and analyzing written or visual materials, such as reports, memos, or videos, to answer research questions.

Data Analysis Methods

Once data has been collected in original research, it needs to be analyzed to answer research questions and draw conclusions. There are various data analysis methods that researchers can use, depending on the type of data collected and the research question. Some common data analysis methods used in original research include:

- Descriptive statistics: This involves using statistical measures such as mean, median, mode, and standard deviation to describe the characteristics of the data.

- Inferential statistics: This involves using statistical methods to infer conclusions about a population based on a sample of data.

- Regression analysis: This involves examining the relationship between two or more variables by using statistical models that predict the value of one variable based on the value of one or more other variables.

- Content analysis: This involves analyzing written or visual materials, such as documents, videos, or social media posts, to identify patterns, themes, or trends.

- Qualitative analysis: This involves analyzing non-numerical data, such as interview transcripts or observation notes, to identify themes, patterns, or categories.

- Grounded theory: This involves developing a theory or model based on the data collected in the study.

- Mixed methods analysis: This involves combining quantitative and qualitative data analysis methods to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research question.

How to Conduct Original Research

Conducting original research involves several steps that researchers need to follow to ensure that their research is valid, reliable, and produces meaningful results. Here are some general steps that researchers can follow to conduct original research:

- Identify the research question: The first step in conducting original research is to identify a research question that is relevant, significant, and feasible. The research question should be specific and focused to guide the research process.

- Conduct a literature review: Once the research question is identified, researchers should conduct a thorough literature review to identify existing research on the topic. This will help them identify gaps in the existing knowledge and develop a research plan that builds on previous research.

- Develop a research plan: Researchers should develop a research plan that outlines the methods they will use to collect and analyze data. The research plan should be detailed and include information on the population and sample, data collection methods, data analysis methods, and ethical considerations.

- Collect data: Once the research plan is developed, researchers can begin collecting data using the methods identified in the plan. It is important to ensure that the data collection process is consistent and accurate to ensure the validity and reliability of the data.

- Analyze data: Once the data is collected, researchers should analyze it using appropriate data analysis methods. This will help them answer the research question and draw conclusions from the data.

- Interpret results: After analyzing the data, researchers should interpret the results and draw conclusions based on the findings. This will help them answer the research question and make recommendations for future research or practical applications.

- Communicate findings: Finally, researchers should communicate their findings to the appropriate audience using a format that is appropriate for the research question and audience. This may include writing a research paper, presenting at a conference, or creating a report for a client or stakeholder.

Purpose of Original Research

The purpose of original research is to generate new knowledge and understanding in a particular field of study. Original research is conducted to address a research question, hypothesis, or problem and to produce empirical evidence that can be used to inform theory, policy, and practice. By conducting original research, researchers can:

- Expand the existing knowledge base: Original research helps to expand the existing knowledge base by providing new information and insights into a particular phenomenon. This information can be used to develop new theories, models, or frameworks that explain the phenomenon in greater depth.

- Test existing theories and hypotheses: Original research can be used to test existing theories and hypotheses by collecting empirical evidence and analyzing the data. This can help to refine or modify existing theories, or to develop new ones that better explain the phenomenon.

- Identify gaps in the existing knowledge: Original research can help to identify gaps in the existing knowledge base by highlighting areas where further research is needed. This can help to guide future research and identify new research questions that need to be addressed.

- Inform policy and practice: Original research can be used to inform policy and practice by providing empirical evidence that can be used to make decisions and develop interventions. This can help to improve the quality of life for individuals and communities, and to address social, economic, and environmental challenges.

How to publish Original Research

Publishing original research involves several steps that researchers need to follow to ensure that their research is accepted and published in reputable academic journals. Here are some general steps that researchers can follow to publish their original research:

- Select a suitable journal: Researchers should identify a suitable academic journal that publishes research in their field of study. The journal should have a good reputation and a high impact factor, and should be a good fit for the research topic and methods used.

- Review the submission guidelines: Once a suitable journal is identified, researchers should review the submission guidelines to ensure that their manuscript meets the journal’s requirements. The guidelines may include requirements for formatting, length, and content.

- Write the manuscript : Researchers should write the manuscript in accordance with the submission guidelines and academic standards. The manuscript should include a clear research question or hypothesis, a description of the research methods used, an analysis of the data collected, and a discussion of the results and their implications.

- Submit the manuscript: Once the manuscript is written, researchers should submit it to the selected journal. The submission process may require the submission of a cover letter, abstract, and other supporting documents.

- Respond to reviewer feedback: After the manuscript is submitted, it will be reviewed by experts in the field who will provide feedback on the quality and suitability of the research. Researchers should carefully review the feedback and revise the manuscript accordingly.

- Respond to editorial feedback: Once the manuscript is revised, it will be reviewed by the journal’s editorial team who will provide feedback on the formatting, style, and content of the manuscript. Researchers should respond to this feedback and make any necessary revisions.

- Acceptance and publication: If the manuscript is accepted, the journal will inform the researchers and the manuscript will be published in the journal. If the manuscript is not accepted, researchers can submit it to another journal or revise it further based on the feedback received.

How to Identify Original Research

To identify original research, there are several factors to consider:

- The research question: Original research typically starts with a novel research question or hypothesis that has not been previously explored or answered in the existing literature.

- The research design: Original research should have a clear and well-designed research methodology that follows appropriate scientific standards. The methodology should be described in detail in the research article.

- The data: Original research should include new data that has not been previously published or analyzed. The data should be collected using appropriate research methods and analyzed using valid statistical methods.

- The results: Original research should present new findings or insights that have not been previously reported in the existing literature. The results should be presented clearly and objectively, and should be supported by the data collected.

- The discussion and conclusions: Original research should provide a clear and objective interpretation of the results, and should discuss the implications of the research findings. The discussion and conclusions should be based on the data collected and the research question or hypothesis.

- The references: Original research should be supported by references to existing literature, which should be cited appropriately in the research article.

Advantages of Original Research

Original research has several advantages, including:

- Generates new knowledge: Original research is conducted to answer novel research questions or hypotheses, which can generate new knowledge and insights into various fields of study.

- Supports evidence-based decision making: Original research provides empirical evidence that can inform decision-making in various fields, such as medicine, public policy, and business.

- Enhances academic and professional reputation: Conducting original research and publishing in reputable academic journals can enhance a researcher’s academic and professional reputation.

- Provides opportunities for collaboration: Original research can provide opportunities for collaboration between researchers, institutions, and organizations, which can lead to new partnerships and research projects.

- Advances scientific and technological progress: Original research can contribute to scientific and technological progress by providing new knowledge and insights into various fields of study, which can inform further research and development.

- Can lead to practical applications: Original research can have practical applications in various fields, such as medicine, engineering, and social sciences, which can lead to new products, services, and policies that benefit society.

Limitations of Original Research

Original research also has some limitations, which include:

- Time and resource constraints: Original research can be time-consuming and expensive, requiring significant resources to design, execute, and analyze the research data.

- Ethical considerations: Conducting original research may raise ethical considerations, such as ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of research participants, obtaining informed consent, and avoiding conflicts of interest.

- Risk of bias: Original research may be subject to biases, such as selection bias, measurement bias, and publication bias, which can affect the validity and reliability of the research findings.

- Generalizability: Original research findings may not be generalizable to larger populations or different contexts, which can limit the applicability of the research findings.

- Replicability: Original research may be difficult to replicate, which can limit the ability of other researchers to verify the research findings.

- Limited scope: Original research may have a limited scope, focusing on a specific research question or hypothesis, which can limit the breadth of the research findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Documentary Research – Types, Methods and...

Scientific Research – Types, Purpose and Guide

Humanities Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Historical Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Artistic Research – Methods, Types and Examples

- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Thomas G. Carpenter Library

Original Research

How can i tell if the article is original research.

- Glossary of Terms

- What are Peer Reviewed/Refereed Articles?

Chat With Us Text Us (904) 507-4122 Email Us Schedule a Research Consultation

Visit us on social media!

What is Original Research?

Original research is considered a primary source.

An article is considered original research if...

- it is the report of a study written by the researchers who actually did the study.

- the researchers describe their hypothesis or research question and the purpose of the study.

- the researchers detail their research methods.

- the results of the research are reported.

- the researchers interpret their results and discuss possible implications.

There is no one way to easily tell if an article is a research article like there is for peer-reviewed articles in the Ulrich's database. The only way to be sure is to read the article to verify that it is written by the researchers and that they have explained all of their findings, in addition to listing their methodologies, results, and any conclusions based on the evidence collected.

All that being said, there are a few key indicators that will help you to quickly decide whether or not your article is based on original research.

- Literature Review or Background

- Conclusions

- Read through the abstract (summary) before you attempt to find the full-text PDF. The abstract of the article usually contains those subdivision headings where each of the key sections are summarized individually.

- Use the checkbox with CINAHL's advanced search to only see articles that have been tagged as research articles.

- Next: Glossary of Terms >>

- Last Updated: Feb 7, 2022 11:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/originalresearch

Research articles

Reverse total shoulder replacement versus anatomical total shoulder replacement for osteoarthritis, effect of combination treatment with glp-1 receptor agonists and sglt-2 inhibitors on incidence of cardiovascular and serious renal events, prenatal opioid exposure and risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in children, temporal trends in lifetime risks of atrial fibrillation and its complications, antipsychotic use in people with dementia, predicting the risks of kidney failure and death in adults with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease, impact of large scale, multicomponent intervention to reduce proton pump inhibitor overuse, esketamine after childbirth for mothers with prenatal depression, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist use and risk of thyroid cancer, use of progestogens and the risk of intracranial meningioma, delirium and incident dementia in hospital patients, derivation and external validation of a simple risk score for predicting severe acute kidney injury after intravenous cisplatin, quality and safety of artificial intelligence generated health information, large language models and the generation of health disinformation, 25 year trends in cancer incidence and mortality among adults in the uk, cervical pessary versus vaginal progesterone in women with a singleton pregnancy, comparison of prior authorization across insurers, diagnostic accuracy of magnetically guided capsule endoscopy with a detachable string for detecting oesophagogastric varices in adults with cirrhosis, ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes, added benefit and revenues of oncology drugs approved by the ema, exposure to air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular diseases, short term exposure to low level ambient fine particulate matter and natural cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory morbidity, optimal timing of influenza vaccination in young children, effect of exercise for depression, association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with cardiovascular disease and all cause death in patients with type 2 diabetes, duration of cpr and outcomes for adults with in-hospital cardiac arrest, clinical effectiveness of an online physical and mental health rehabilitation programme for post-covid-19 condition, atypia detected during breast screening and subsequent development of cancer, publishers’ and journals’ instructions to authors on use of generative ai in academic and scientific publishing, effectiveness of glp-1 receptor agonists on glycaemic control, body weight, and lipid profile for type 2 diabetes, neurological development in children born moderately or late preterm, invasive breast cancer and breast cancer death after non-screen detected ductal carcinoma in situ, all cause and cause specific mortality in obsessive-compulsive disorder, acute rehabilitation following traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation, perinatal depression and risk of mortality, undisclosed financial conflicts of interest in dsm-5-tr, effect of risk mitigation guidance opioid and stimulant dispensations on mortality and acute care visits, update to living systematic review on sars-cov-2 positivity in offspring and timing of mother-to-child transmission, perinatal depression and its health impact, christmas 2023: common healthcare related instruments subjected to magnetic attraction study, using autoregressive integrated moving average models for time series analysis of observational data, demand for morning after pill following new year holiday, christmas 2023: christmas recipes from the great british bake off, effect of a doctor working during the festive period on population health: experiment using doctor who episodes, christmas 2023: analysis of barbie medical and science career dolls, christmas 2023: effect of chair placement on physicians’ behavior and patients’ satisfaction, management of chronic pain secondary to temporomandibular disorders, christmas 2023: projecting complete redaction of clinical trial protocols, christmas 2023: a drug target for erectile dysfunction to help improve fertility, sexual activity, and wellbeing, christmas 2023: efficacy of cola ingestion for oesophageal food bolus impaction, conservative management versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in adults with gallstone disease, social media use and health risk behaviours in young people, untreated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 and cervical cancer, air pollution deaths attributable to fossil fuels, implementation of a high sensitivity cardiac troponin i assay and risk of myocardial infarction or death at five years, covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against post-covid-19 condition, association between patient-surgeon gender concordance and mortality after surgery, intravascular imaging guided versus coronary angiography guided percutaneous coronary intervention, treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in men in primary care using a conservative intervention, autism intervention meta-analysis of early childhood studies, effectiveness of the live zoster vaccine during the 10 years following vaccination, effects of a multimodal intervention in primary care to reduce second line antibiotic prescriptions for urinary tract infections in women, pyrotinib versus placebo in combination with trastuzumab and docetaxel in patients with her2 positive metastatic breast cancer, association of dcis size and margin status with risk of developing breast cancer post-treatment, racial differences in low value care among older patients in the us, pharmaceutical industry payments and delivery of low value cancer drugs, rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin in adults with coronary artery disease, clinical effectiveness of septoplasty versus medical management for nasal airways obstruction, ultrasound guided lavage with corticosteroid injection versus sham lavage with and without corticosteroid injection for calcific tendinopathy of shoulder, early versus delayed antihypertensive treatment in patients with acute ischaemic stroke, mortality risks associated with floods in 761 communities worldwide, interactive effects of ambient fine particulate matter and ozone on daily mortality in 372 cities, association between changes in carbohydrate intake and long term weight changes, future-case control crossover analysis for adjusting bias in case crossover studies, association between recently raised anticholinergic burden and risk of acute cardiovascular events, suboptimal gestational weight gain and neonatal outcomes in low and middle income countries: individual participant data meta-analysis, efficacy and safety of an inactivated virus-particle vaccine for sars-cov-2, effect of invitation letter in language of origin on screening attendance: randomised controlled trial in breastscreen norway, visits by nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the usa, non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and oesophageal adenocarcinoma, venous thromboembolism with use of hormonal contraception and nsaids, food additive emulsifiers and risk of cardiovascular disease, balancing risks and benefits of cannabis use, promoting activity, independence, and stability in early dementia and mild cognitive impairment, effect of home cook interventions for salt reduction in china, cancer mortality after low dose exposure to ionising radiation, effect of a smartphone intervention among university students with unhealthy alcohol use, long term risk of death and readmission after hospital admission with covid-19 among older adults, mortality rates among patients successfully treated for hepatitis c, association between antenatal corticosteroids and risk of serious infection in children, the proportions of term or late preterm births after exposure to early antenatal corticosteroids, and outcomes, safety of ba.4-5 or ba.1 bivalent mrna booster vaccines, comparative effectiveness of booster vaccines among adults aged ≥50 years, third dose vaccine schedules against severe covid-19 during omicron predominance in nordic countries, private equity ownership and impacts on health outcomes, costs, and quality, healthcare disruption due to covid-19 and avoidable hospital admission, educational inequalities in mortality and their mediators among generations across four decades, prevalence and predictors of data and code sharing in the medical and health sciences, medicare eligibility and in-hospital treatment patterns and health outcomes for patients with trauma, follow us on, content links.

- Collections

- Health in South Asia

- Women’s, children’s & adolescents’ health

- News and views

- BMJ Opinion

- Rapid responses

- Editorial staff

- BMJ in the USA

- BMJ in South Asia

- Submit your paper

- BMA members

- Subscribers

- Advertisers and sponsors

Explore BMJ

- Our company

- BMJ Careers

- BMJ Learning

- BMJ Masterclasses

- BMJ Journals

- BMJ Student

- Academic edition of The BMJ

- BMJ Best Practice

- The BMJ Awards

- Email alerts

- Activate subscription

Information

- SpringerLink shop

Types of journal articles

It is helpful to familiarise yourself with the different types of articles published by journals. Although it may appear there are a large number of types of articles published due to the wide variety of names they are published under, most articles published are one of the following types; Original Research, Review Articles, Short reports or Letters, Case Studies, Methodologies.

Original Research:

This is the most common type of journal manuscript used to publish full reports of data from research. It may be called an Original Article, Research Article, Research, or just Article, depending on the journal. The Original Research format is suitable for many different fields and different types of studies. It includes full Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections.

Short reports or Letters:

These papers communicate brief reports of data from original research that editors believe will be interesting to many researchers, and that will likely stimulate further research in the field. As they are relatively short the format is useful for scientists with results that are time sensitive (for example, those in highly competitive or quickly-changing disciplines). This format often has strict length limits, so some experimental details may not be published until the authors write a full Original Research manuscript. These papers are also sometimes called Brief communications .

Review Articles:

Review Articles provide a comprehensive summary of research on a certain topic, and a perspective on the state of the field and where it is heading. They are often written by leaders in a particular discipline after invitation from the editors of a journal. Reviews are often widely read (for example, by researchers looking for a full introduction to a field) and highly cited. Reviews commonly cite approximately 100 primary research articles.

TIP: If you would like to write a Review but have not been invited by a journal, be sure to check the journal website as some journals to not consider unsolicited Reviews. If the website does not mention whether Reviews are commissioned it is wise to send a pre-submission enquiry letter to the journal editor to propose your Review manuscript before you spend time writing it.

Case Studies:

These articles report specific instances of interesting phenomena. A goal of Case Studies is to make other researchers aware of the possibility that a specific phenomenon might occur. This type of study is often used in medicine to report the occurrence of previously unknown or emerging pathologies.

Methodologies or Methods

These articles present a new experimental method, test or procedure. The method described may either be completely new, or may offer a better version of an existing method. The article should describe a demonstrable advance on what is currently available.

Back │ Next

- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

Original Research

An original research paper should present a unique argument of your own. In other words, the claim of the paper should be debatable and should be your (the researcher’s) own original idea. Typically an original research paper builds on the existing research on a topic, addresses a specific question, presents the findings according to a standard structure (described below), and suggests questions for further research and investigation. Though writers in any discipline may conduct original research, scientists and social scientists in particular are interested in controlled investigation and inquiry. Their research often consists of direct and indirect observation in the laboratory or in the field. Many scientists write papers to investigate a hypothesis (a statement to be tested).

Although the precise order of research elements may vary somewhat according to the specific task, most include the following elements:

- Table of contents

- List of illustrations

- Body of the report

- References cited

Check your assignment for guidance on which formatting style is required. The Complete Discipline Listing Guide (Purdue OWL) provides information on the most common style guide for each discipline, but be sure to check with your instructor.

The title of your work is important. It draws the reader to your text. A common practice for titles is to use a two-phrase title where the first phrase is a broad reference to the topic to catch the reader’s attention. This phrase is followed by a more direct and specific explanation of your project. For example:

“Lions, Tigers, and Bears, Oh My!: The Effects of Large Predators on Livestock Yields.”

The first phrase draws the reader in – it is creative and interesting. The second part of the title tells the reader the specific focus of the research.

In addition, data base retrieval systems often work with keywords extracted from the title or from a list the author supplies. When possible, incorporate them into the title. Select these words with consideration of how prospective readers might attempt to access your document. For more information on creating keywords, refer to this Springer research publication guide.

See the KU Writing Center Writing Guide on Abstracts for detailed information about creating an abstract.

Table of Contents

The table of contents provides the reader with the outline and location of specific aspects of your document. Listings in the table of contents typically match the headings in the paper. Normally, authors number any pages before the table of contents as well as the lists of illustrations/tables/figures using lower-case roman numerals. As such, the table of contents will use lower-case roman numbers to identify the elements of the paper prior to the body of the report, appendix, and reference page. Additionally, because authors will normally use Arabic numerals (e.g., 1, 2, 3) to number the pages of the body of the research paper (starting with the introduction), the table of contents will use Arabic numerals to identify the main sections of the body of the paper (the introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, conclusion, references, and appendices).

Here is an example of a table of contents:

ABSTRACT..................................................iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS...............................iv

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS...........................v

LIST OF TABLES.........................................vii

INTRODUCTION..........................................1

LITERATURE REVIEW.................................6

METHODS....................................................9

RESULTS....................................................10

DISCUSSION..............................................16

CONCLUSION............................................18

REFERENCES............................................20

APPENDIX................................................. 23

More information on creating a table of contents can be found in the Table of Contents Guide (SHSU) from the Newton Gresham Library at Sam Houston State University.

List of Illustrations

Authors typically include a list of the illustrations in the paper with longer documents. List the number (e.g., Illustration 4), title, and page number of each illustration under headings such as "List of Illustrations" or "List of Tables.”

Body of the Report

The tone of a report based on original research will be objective and formal, and the writing should be concise and direct. The structure will likely consist of these standard sections: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion . Typically, authors identify these sections with headings and may use subheadings to identify specific themes within these sections (such as themes within the literature under the literature review section).

Introduction

Given what the field says about this topic, here is my contribution to this line of inquiry.

The introduction often consists of the rational for the project. What is the phenomenon or event that inspired you to write about this topic? What is the relevance of the topic and why is it important to study it now? Your introduction should also give some general background on the topic – but this should not be a literature review. This is the place to give your readers and necessary background information on the history, current circumstances, or other qualities of your topic generally. In other words, what information will a layperson need to know in order to get a decent understanding of the purpose and results of your paper? Finally, offer a “road map” to your reader where you explain the general order of the remainder of your paper. In the road map, do not just list the sections of the paper that will follow. You should refer to the main points of each section, including the main arguments in the literature review, a few details about your methods, several main points from your results/analysis, the most important takeaways from your discussion section, and the most significant conclusion or topic for further research.

Literature Review

This is what other researchers have published about this topic.

In the literature review, you will define and clarify the state of the topic by citing key literature that has laid the groundwork for this investigation. This review of the literature will identify relations, contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies between previous investigations and this one, and suggest the next step in the investigation chain, which will be your hypothesis. You should write the literature review in the present tense because it is ongoing information.

Methods (Procedures)

This is how I collected and analyzed the information.

This section recounts the procedures of the study. You will write this in past tense because you have already completed the study. It must include what is necessary to replicate and validate the hypothesis. What details must the reader know in order to replicate this study? What were your purposes in this study? The challenge in this section is to understand the possible readers well enough to include what is necessary without going into detail on “common-knowledge” procedures. Be sure that you are specific enough about your research procedure that someone in your field could easily replicate your study. Finally, make sure not to report any findings in this section.

This is what I found out from my research.

This section reports the findings from your research. Because this section is about research that is completed, you should write it primarily in the past tense . The form and level of detail of the results depends on the hypothesis and goals of this report, and the needs of your audience. Authors of research papers often use visuals in the results section, but the visuals should enhance, rather than serve as a substitute, for the narrative of your results. Develop a narrative based on the thesis of the paper and the themes in your results and use visuals to communicate key findings that address your hypothesis or help to answer your research question. Include any unusual findings that will clarify the data. It is a good idea to use subheadings to group the results section into themes to help the reader understand the main points or findings of the research.

This is what the findings mean in this situation and in terms of the literature more broadly.

This section is your opportunity to explain the importance and implications of your research. What is the significance of this research in terms of the hypothesis? In terms of other studies? What are possible implications for any academic theories you utilized in the study? Are there any policy implications or suggestions that result from the study? Incorporate key studies introduced in the review of literature into your discussion along with your own data from the results section. The discussion section should put your research in conversation with previous research – now you are showing directly how your data complements or contradicts other researchers’ data and what the wider implications of your findings are for academia and society in general. What questions for future research do these findings suggest? Because it is ongoing information, you should write the discussion in the present tense . Sometimes the results and discussion are combined; if so, be certain to give fair weight to both.

These are the key findings gained from this research.

Summarize the key findings of your research effort in this brief final section. This section should not introduce new information. You can also address any limitations from your research design and suggest further areas of research or possible projects you would complete with a new and improved research design.

References/Works Cited

See KU Writing Center writing guides to learn more about different citation styles like APA, MLA, and Chicago. Make an appointment at the KU Writing Center for more help. Be sure to format the paper and references based on the citation style that your professor requires or based on the requirements of the academic journal or conference where you hope to submit the paper.

The appendix includes attachments that are pertinent to the main document but are too detailed to be included in the main text. These materials should be titled and labeled (for example Appendix A: Questionnaire). You should refer to the appendix in the text with in-text references so the reader understands additional useful information is available elsewhere in the document. Examples of documents to include in the appendix include regression tables, tables of text analysis data, and interview questions.

Updated June 2022

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Subject Guides

Biology 303L: Ecology and Evolution

- About Original Research

- Scientific Research Process

- Articles to Practice Identifying

- Reading Original Research Articles

- Citation-Based Searching

- Related Guides

- Review Tutorials

- Helpful Web Resources

Original Research Articles

Definition : An original research article communicates the research question, methods, results, and conclusions of a research study or experiment conducted by the author(s). These articles present original research data or findings generated through the course of the authors' study and an analysis of that data or information.

Published in Journals : Origingal research articles are published in scientific journals, also called scholarly or academic journals. These can be published in print and/or online. Journals are serial publications, meaning they publish volumes and issues on a schedule continually over time, similar to a magazine but for a scholarly audience. You can access journals through many of the library's databases. A list of recommended databases to use to search for original articles on biology subjects can be found through this link , accessible from the database "subject" dropdown on the library homepage.

Peer Reviewed : Prior to being published, original research articles undergo a process called peer review in an effort to ensure that published articles are based on sound research that adheres to established standards in the discipline. This means that after an article is first submitted to a journal, it is reviewed by other scientists who are experts in the article's subject area. These individuals review the article and provide unbiased feedback about the soundness of the background information, research methods, analysis, conclusions, logic, and reasoning of any conclusions; the author needs to incorporate and/or respond to recommended edits before an article will be published. Though it isn't perfect, peer review is the best quality control mechanism that scholars currently have in place to validate the quality of published research.

Peer reviewed articles will often be published with "Received", "Accepted", and "Published" dates, which indicates the timeline of the peer review process.

Structure : Traditionally, an original research article follows a standardized structure known by the acronym IMRD, which stands for Introduction, Methods, Results, & Discussion. Further information about the IMRD structure is available on the Reading Original Research Articles tab of this guide.

Other types of journal articles

Review Articles (usually peer reviewed) : Summarize and synthesize the current published literature on a certain topic. They do not involve original experiments or report new findings. The scope of a review article may be broad or narrow, depending on the publication record. Original research articles do incorporate literature review components, but a review article covers only review content.

Non Peer Reviewed Articles in Journals : Many journals publish the types of articles where peer review is not required. These differ by publication but may include research notes (brief reports of new research findings); responses to other articles; letters, commentaries, or opinion pieces; book reviews; and news. These articles are often more concise and will typically have a shorter reference list or no reference list at all. Many journals will indicate what genre these articles fall into on the article itself by using a label.

Why is Published Original Research Important?

Current information : Typical publication turnaround varies, but can be as quick as ~3 months.

Replicable : The studies published in original research articles contain enough methodological detail to be replicated so research can be verified (though this is a topic of recent debate ).

Contains Raw Data : The raw original research data, along with information about experimental conditions, allows for reuse of results for your own research or analysis.

Shows Logic : Using the provided data and methods, you can evaluate the logic of the authors' conclusions.

- << Previous: Scientific Research Process

- Next: Articles to Practice Identifying >>

- Last Updated: Sep 6, 2022 4:02 PM

- URL: https://libguides.unm.edu/biology303

Finding original (or "scientific") research articles: Where do I find these articles?

- Definition and description

- Where do I find these articles?

- How do I understand them?

- What's the point?

Quick answer...

Library research databases!

In databases, you can narrow down your options to research articles (also sometimes listed as "scholarly" and/or "peer reviewed" in databases) -- or choose a database that ONLY includes research articles. In the box below are a few good starting options, but you can also see all of the TCC library research databases via the link below.

- Complete List of TCC Library Research Databases Click here to view all of the research databases available at your TCC Library

Popular research databases

- EBSCOhost databases

- ScienceDirect

The Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, and PsycARTICLES databases (all published by EbscoHost) include many original research articles. (The direct links to these databases are at the bottom of this box.)

Search tips:

Type your topic into the first one or two search boxes and then use another box to type: "methods OR results OR study" as shown here in the second box. Use the drop down menu to choose the ABSTRACT search field for all boxes. Click search.

Limit to academic journals:

Limit the results list by checking the "Academic Journals" limiter on the left side of the results page

You will still need to examine the individual articles looking for the characteristics listed under the "Definition and description" tab on this guide to be sure of finding the right kind of article.

Explore these databases:

The ProQuest databases also include scientific research articles. There is a larger number and mix of article types in ProQuest, so you may need to look through a larger number of articles to find what you need.

Click on ADVANCED SEARCH, then enter your search terms in one or two search boxes and results OR methods in the second or third box. As in EbscoHost, change the search field to "Abstract".

Limit your results to scholarly journals:

Quite a bit further down the screen, limit the search as shown below:

As you look through your results, you will need to examine the characteristics of the individual articles to make certain they are what you need.

Explore the ProQuest database:

ScienceDirect is a database that only includes scholarly, scientific articles!

Advanced Search tips:

If you go to the "Advanced Search" option, you can see there is an option below the search boxes to narrow down to "research articles"

Explore ScienceDirect:

- << Previous: Definition and description

- Next: How do I understand them? >>

- Last Updated: Mar 21, 2024 10:25 AM

- URL: https://tacomacc.libguides.com/originalresearcharticles

Tacoma Community College Library - Building 7, 6501 South 19th Street, Tacoma, WA 98466 - P. 253.566.5087

Visit us on Instagram!

Scientific Manuscript Writing: Original Research, Case Reports, Review Articles

- First Online: 02 March 2024

Cite this chapter

- Kimberly M. Rathbun 5

12 Accesses

Manuscripts are used to communicate the findings of your work with other researchers. Writing your first manuscript can be a challenge. Journals provide guidelines to authors which should be followed closely. The three major types of articles (original research, case reports, and review articles) all generally follow the IMRAD format with slight variations in content. With planning and thought, manuscript writing does not have to be a daunting task.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Suggested Readings

Alsaywid BS, Abdulhaq NM. Guideline on writing a case report. Urol Ann. 2019;11(2):126–31.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cohen H. How to write a patient case report. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(19):1888–92.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cooper ID. How to write an original research paper (and get it published). J Med Lib Assoc. 2015;103:67–8.

Article Google Scholar

Gemayel R. How to write a scientific paper. FEBS J. 2016;283(21):3882–5.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gülpınar Ö, Güçlü AG. How to write a review article? Turk J Urol. 2013;39(Suppl 1):44–8.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Huth EJ. Structured abstracts for papers reporting clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:626–7.

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals. http://www.ICMJE.org . Accessed 23 Aug 2022.

Liumbruno GM, Velati C, Pasqualetti P, Franchini M. How to write a scientific manuscript for publication. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:217–26.

McCarthy LH, Reilly KE. How to write a case report. Fam Med. 2000;32(3):190–5.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, McKenzie JE. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160.

The Biosemantics Group. Journal/author name estimator. https://jane.biosemantics.org/ . Accessed 24 Aug 2022.

Weinstein R. How to write a manuscript for peer review. J Clin Apher. 2020;35(4):358–66.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Emergency Medicine, AU/UGA Medical Partnership, Athens, GA, USA

Kimberly M. Rathbun

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kimberly M. Rathbun .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Emergency Medicine, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA, USA

Robert P. Olympia

Elizabeth Barrall Werley

Jeffrey S. Lubin

MD Anderson Cancer Center at Cooper, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, NJ, USA

Kahyun Yoon-Flannery

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Rathbun, K.M. (2023). Scientific Manuscript Writing: Original Research, Case Reports, Review Articles. In: Olympia, R.P., Werley, E.B., Lubin, J.S., Yoon-Flannery, K. (eds) An Emergency Physician’s Path. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47873-4_80

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47873-4_80

Published : 02 March 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-47872-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-47873-4

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 05 February 2007

Original research in pathology: judgment, or evidence-based medicine?

- James M Crawford 1

Laboratory Investigation volume 87 , pages 104–114 ( 2007 ) Cite this article

6931 Accesses

30 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

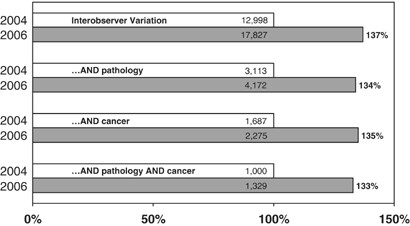

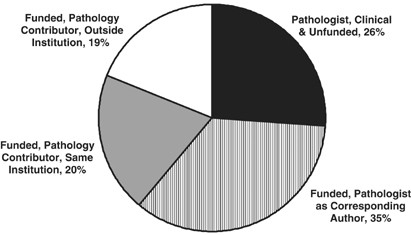

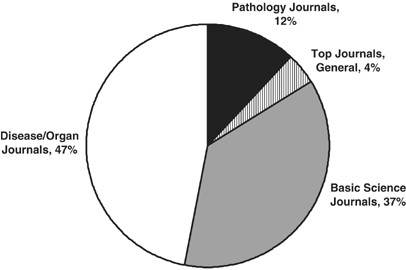

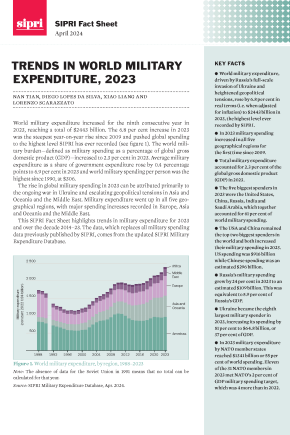

Pathology is both a medical specialty and an investigative scientific discipline, concerned with understanding the essential nature of human disease. Ultimately, pathology is accountable as well, as measured by the accuracy of our diagnoses and the resultant patient care outcomes. As such, we must consider the evidence base underlying our practices. Within the realm of Laboratory Medicine, extensive attention has been given to testing accuracy and precision. Critical examination of the evidence base supporting the clinical use of specific laboratory tests or technologies is a separate endeavor, to which specific attention must be given. In the case of anatomic pathology and more specifically surgical pathology, the expertise required to render a diagnosis is derived foremost from experience, both personal and literature-based. In the first instance, knowledge of the linkage between one's own diagnoses and individual patient outcomes is required, to validate the role of one's own interpretations in the clinical course of patients. Experience comes from seeing this linkage first hand, from which hopefully comes wisdom and, ultimately, good clinical judgment. In the second instance, reading the literature and learning from experts is required. Only a minority of the relevant literature is published in pathology journals to which one may subscribe. A substantial portion of major papers relevant to the practice of anatomic pathology are published in collateral clinical specialty journals devoted to specific disease areas or organs. Active effort is therefore required to seek out the literature beyond the domain of pathology journals. In examining the published literature, the essential question then becomes: Does the practice of anatomic pathology fulfill the tenets of ‘evidence-based medicine’ (EBM)? If the pinnacle of EBM is ‘systematic review of randomized clinical trials, with or without meta-analysis’, then anatomic pathology falls far short. Our published literature is largely observational in nature, with reports of case series (with or without statistical analysis) constituting the majority of our ‘evidence base’. Moreover, anatomic pathology is subject to ‘interobserver variation’, and potentially to ‘error’. Taken further, individual interpretation of tissue samples is not an objective endeavor, and it is not easy to fulfill the role of a ‘gold standard’. Both for rendering of an overall interpretation, and for providing the semi-quantitative and quantitative numerical ‘scores’ which support evidence-based clinical treatment algorithms, the Pathologist has to exercise a high level of interpretive judgment. Nevertheless, the contribution of anatomic pathology to ‘EBM’ is remarkably strong. To the extent that our judgmental interpretations become data, our tissue interpretations become the arbiters of patient care management decisions. In a more global sense, we support highly successful cancer screening programs, and play critical roles in the multidisciplinary management of complex patients. The true error is for the clinical practitioners of ‘EBM’ to forget the contribution to the supporting evidence base of the physicians that are Anatomic Pathologists. Finally, the academic productivity of pathology faculty who operate in the clinical realm must be considered. A survey of six North American academic pathology departments reveals that 26% of all papers published in 2005 came from ‘unfunded’ clinical faculty. While it is likely that their academic productivity is lower than that of ‘funded’ research faculty, the contribution of clinical faculty to the knowledge base for the practice of modern medicine, and to the academic reputation of the department, must not be overlooked. The ability of clinical faculty in academic departments of pathology to pursue original scholarship must be supported if our specialty is to retain its preeminence as an investigative scientific discipline in the age of EBM.

Similar content being viewed by others

An analysis of research biopsy core variability from over 5000 prospectively collected core samples

Understanding the errors made by artificial intelligence algorithms in histopathology in terms of patient impact

An end-to-end workflow for nondestructive 3D pathology

‘Pathology’ is the medical specialty concerned with the essential nature of disease, practiced by trained physicians for the benefit of patient care. ‘Pathology’ also is a scientific discipline, since the very process of understanding human disease is a scientific endeavor. However, defining the ‘discipline’ of pathology is problematic, since investigation of human disease spans all the scientific disciplines of biomedical research. Hence, the identity of ‘pathology’ is evanescent. On the one hand, medical students considering pathology for post-graduate training are given little opportunity to appreciate what Pathologists actually do—it is only the fortunate few who can appreciate the extraordinarily fulfilling nature of a potential career in the specialty of pathology. On the other hand, academic departments of pathology have to be all things to all people, owing both to the need to provide outstanding diagnostic expertise for all of the practicing clinical specialties and subspecialties, and to the need to have robust research programming in some or many realms of disease pathobiology. Further, one can wonder how ‘specialty’ and ‘discipline’ knit together into the concept of pathology as a ‘profession’. A profession is an occupation that requires extensive training, the study and mastery of specialized knowledge, and usually has an ethical code and process of certification or licensing. Corollaries are that one has to swear an oath to uphold the ethics of the profession, and ‘profess’ to a higher standard of accountability. To the extent that accountability ultimately is measured on the basis of patient outcomes, the ‘profession’ of pathology is subject to consideration of the evidence base underlying our practices.

From a historical perspective, what we might call ‘pathology’ emerged early in the practice of medicine. The technology of ancient times was straightforward, as exemplified by Hippocrates: the taking of a medical history and a bedside examination. A significant innovation in that era was examination of the urine. The dawn of rigorous medical science began with systematic dissection of the human body, beginning with Galen (129–200 AD). After a prolonged hiatus through medieval times, the Italian anatomists of the 15th century laid the groundwork for the publication in 1543 by Vesalius of the first books of morbid anatomy, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (‘The Seven Books on the Structure of the Human Body’). Robert Hooke was the first to use the word ‘cell’ to name the small cavities in the honeycomb, in his 1665 book Micrographia (‘Small Drawings’). This work was soon followed by Malpighi's De viscerum structura exercitatio (1666), which essentially founded the fields of histology and microscopic anatomy, and Van Leeuwenhoek's remarkable advances in construction of microscopes, enabling his extensive studies of ‘animalcules’ (single-celled organisms) by 1675. Giovanni Morgagni of Padua published in 1761 the great work De sedibus et causis morborum (‘On the sites and Causes of Diseases’), followed ultimately by Rudolf Virchow's landmark publication in 1858 of Die Cellular-pathologie , which conceived of the cell as the center of all pathological changes. In the decades that followed, especially in Europe, the role of the Anatomic Pathologist as the final arbiter in human disease became well established.

The dawn of the 20th century saw an increasing role for the clinical laboratory in patient care world-wide, over-and-above the utilization of the microscope. By the early 1920s, physicians practicing in the clinical laboratories of the day recognized the need for elevation of this activity to full professional status, and in 1926 the American College of Surgeons revised its minimum standards for hospitals to require that ‘clinical laboratories be under the direction of MD physicians with special training in clinical pathology, with all tissue removed at operations to be examined in the laboratory and reports rendered thereon.’ The American Board of Pathology was instituted in 1936. Finally, in 1943 ‘pathology’ was recognized as the ‘practice of medicine’ by the House of Delegates of the American Medical Association.

Yet even the great Virchow was subject to error (whether it was sampling or interpretive error is a matter of speculation). In one of the most vituperative medical quarrels between opposing treating physicians in history, 1 the crown prince Frederick (1831–1888), son of William I, Emperor of Germany, fell ill with laryngeal hoarseness in January 1887. Although a laryngeal cancer was suspected from the outset, initial biopsies sent to Virchow for interpretation were either insufficient for diagnosis or interpreted as pachydermia verracosa (throat wart). Subsequent biopsies were necrotic or too purulent for diagnosis, despite overwhelming clinical evidence that the laryngeal process was malignant. Failure to obtain an anatomic diagnosis of malignancy, per Virchow , immobilized the clinical treatment team. Only when Frederick was in extremis (February 1888) did laryngeal biopsy finally reveal the ‘little bodies that brought it all about’ (to quote his son, the future Kaiser Wilhelm II).

Although Virchow's reputation appears to have been unharmed, this episode was illustrative of the potentially shaky status that pathology holds as the diagnostic bedrock for patient care. In this Editorial Perspective, consideration will be given to a number of pertinent issues, focusing primarily on the role of anatomic pathology. First, on what basis are diagnostic assessments made in anatomic pathology? Second, does this diagnostic exercise fulfill the requirements for EBM? Third, how well does anatomic pathology serve as a ‘gold standard’ for research being conducted on human tissues? Lastly, what is the academic productivity of pathology scholars who, operating in the clinical realm, are given opportunity to publish their original findings?

The basis of diagnosis in anatomic pathology

My first encounter with the diagnostic process in surgical pathology was on my second day of residency (1982), when my confident diagnosis of ‘axillary lymph nodes positive for metastatic breast carcinoma’ was countermanded by the attending pathologist: I was simply observing ‘sinus histiocytosis’ in the lymph nodes. My silent indignant reaction was, ‘On what basis do you know that you are right, and I am wrong?’ Put differently, how can it be that morphologic examination of devitalized human tissue that has been fixed in formalin, dehydrated and permeated with paraffin, sliced thinly and stained with biblical era colorizing agents (hematoxylin & eosin), covered in glue and sandwiched between glass, has any bearing on clinical management decisions made for the living patient? Potential answers include, ‘Because I am the authority here’, or ‘My experience’, or ‘This is what I was taught’, or ‘This is what the recent literature indicates’, or even ‘This is what is required for synoptic reporting.’ Then and now (24 years later), I am forced to conclude that, ultimately, it is the experience base of over a century-and-a-half of cellular Pathologists that enables us to have credibility in dictating the fortunes (and misfortunes) of living patients.

The question then immediately arises: how is this experience-base established, and what credibility does it have? In a 2006 Lab Invest editorial, 2 I asked this specific question for human liver biopsy interpretation. The methodology was to examine the top 150 most-cited publications in which human liver pathology was included, either as the primary focus of the publication or as contributing data. The dates of publication for these papers were from 1948 to 2003, with a heavy representation of published papers by the most honored leaders of our subspecialty. The results were remarkable: essentially half (48%) of the ‘classics’ in liver pathology were Case Series, which is the reporting of an assembled experience. Another 10% were case series that included additional research in the basic laboratory, so as to obtain insights into the molecular or structural basis of the disease. An additional 16% were ‘Position Papers’, either declarative by authorities in the field, reports by consensus panels, or reviews. So ¾ of the most cited papers in the liver pathology field were published predominantly on the basis of ‘experience’ or ‘opinion’. Only 26% of these 150 most-cited papers would qualify for ‘Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM)’ (to be discussed). These were exclusively within the realm of viral hepatitis, in which clinical outcomes clearly established that liver biopsy was a useful diagnostic investigation in the management of patients with Hepatitis B or C viral infection.

These findings in liver pathology are echoed in a 2005 article by Foucar and Wick 3 (actually published in February 2006). These authors performed a pilot observational analysis of a representative sample of the current pertinent literature on diagnostic tissue pathology. They show that most of such publications employ ‘observational’ research designs, most commonly ‘cross-sectional comparison’. Slightly more than 50% of the anatomic pathology observational studies employed statistical evaluations to support their final conclusions. Unfortunately, such research designs are not admired by advocates of EBM, since they are a distant second choice to ‘experimental’ clinical studies. Foucar and Wick advocate that the latter posture is unacceptable to pathologists, whose research advances are currently completely dependent upon well-conducted observational research. Rather, the challenge to anatomic pathology is to develop and adhere to standards for observational research—including the classification of error in anatomic pathology 4 —so as to realize the full potential of this time-tested approach for advancing clinical knowledge. 3