Biography vs Autobiography: Similarities and Differences

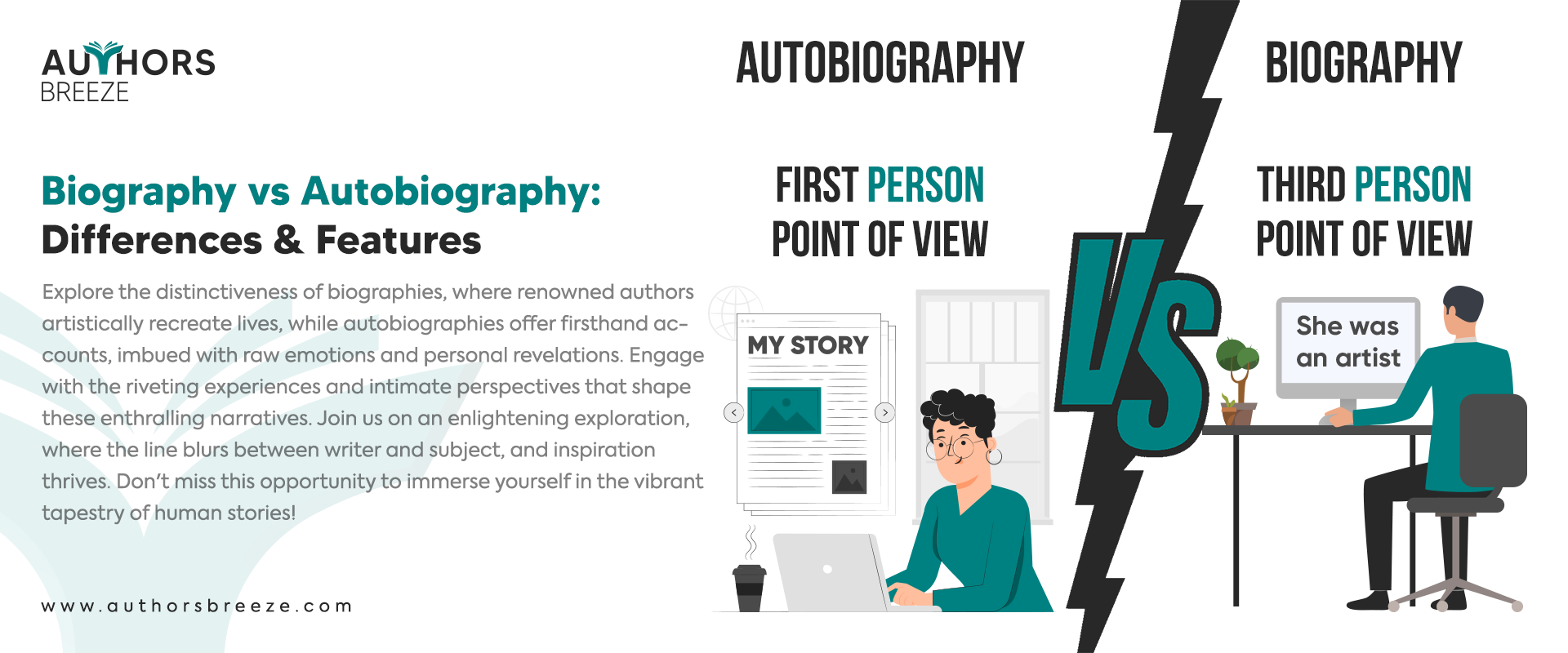

A biography is an account of someone’s life story that is written by an author who is not the subject of the nook. An autobiography, on the other hand, involves an individual narrating their own life experiences.

The differences between biographies and autobiographies relate most prominently to the authorhship:

- Autobiography: When you read an autobiography, you’re getting the author’s own interpretation of their life.

- Biography: When you read a biography, you experience the subject’s life through someone else’s lens (Schiffrin & Brockmeier, 2012).

Biography vs Autobiography

1. biography.

A biography is a detailed account of a person’s life, scripted by an author who is not the person who is featured in the text itself.

This type of life story focuses both on factual events in the person’s life, such as birth, education, work, and death, but often also delves into personal aspects like experiences, relationships, and significant achievements.

It may also weave-in cultural and contextual factors that help illuminate the person’s motivations and core values .

Origins of Biographies

The concept of biography as a literary genre dates back to antiquity. Such works were primarily used to capture the lives of dignified individuals, mainly rulers and war heroes.

Suetonius’s Lives of the Caesars and Plutarch’s Parallel Lives are landmark examples from this ancient period (Sweet, 2010).

The popularity of biographical works only grew in the ensuing centuries, and they became a prominent part of many cultures’ literary traditions.

Into the 18th century and during the Enlightenment, biographies began to present a more balanced portrayal of the subject. They would present both their strengths and flaws, providing a holistic perspective on the subject.

Dr. Samuel Johnson’s compilation of English poets biographies, Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets (1779-1781) ushered in a new era of biography writing by focusing on examining human nature (Ditchfield, 2018).

In the modern era, the genre has evolved and broadened, encompassing a diverse range of figures from all walks of life – there’s a biography in every niche imaginable, with each offering readers an in-depth exploration of their lives, their struggles, and their triumphs.

This demonstrates the enduring appeal of biographies and their value in providing snapshots of history through individual lenses.

Key Characteristics of Biographies

Examples of biographies.

Title: The Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets Author: Dr. Samuel Johnson Description: Dr. Johnson’s work profiles the lives of 52 poets from the 17th and 18th centuries, including John Milton and Alexander Pope. He critiques not just the works, but also explores their personal lives and the sociopolitical contexts of their times (Johnson, 1781). Johnson’s study is invaluable for its integrated historic and biographic approach.

Title: The Life of Samuel Johnson Author: James Boswell Description: This work by Boswell explores, in great depth, the life of his friend and mentor, Dr. Samuel Johnson. The biography offers a compelling portrayal of Dr. Johnson’s life, character, eccentricities, and intellectual prowess (Boswell, 1791). Boswell’s vivid account creates a near-physical presence of Johnson to the readers, making it one of the greatest biographies in English literature.

Title: The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt Author: Edmund Morris Description: In this Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, Morris chronicles the early life of Theodore Roosevelt until his ascension to the U.S presidency. The work brilliantly captures Roosevelt’s extraordinary career and his transformation from a frail asthmatic boy into a robust and vigorous leader (Morris, 1979). Morris accurately represents Roosevelt’s indomitable spirit, making it an engaging and educational read.

Title: Steve Jobs Author: Walter Isaacson Description: This comprehensive biography provides a deep-dive into the life and career of Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple. Isaacson had unparalleled access to Jobs and those closest to him, thus presenting an intimate and detailed account. He explores Jobs’ professional endeavors as well as his personal life, revealing his ambition, intensity, and visionary mind that revolutionized several high-tech industries (Isaacson, 2011).

Title: Alexander Hamilton Author: Ron Chernow Description: Ron Chernow provides a sweeping narrative of one of America’s most compelling founding fathers, Alexander Hamilton. Chernow combines extensive research with a flair for storytelling, charting Hamilton’s evolution from an orphan into a political genius. The book sheds light on Hamilton’s crucial role in the formation of the United States’ financial system and his political ideologies (Chernow, 2004).

2. Autobiography

An autobiography is a self-written record of someone’s own life. It is a personal narrative in which the author writes about their life from their own perspective.

Autobiographies are usually centered around the author’s personal experiences, including key milestones, challenges, and achievements (Eakin, 2015).

They’re also often a defense of the person’s perspective (especially in political autobiographies) or insight into their thought processes, which can make them very intimate.

Origins of Autobiographies

The term ‘autobiography’ was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English periodical The Monthly Review, when he suggested the word as a hybrid but condemned it as ‘pedantic’.

Pioneering examples of the genre form include Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821) and the memoirs by veterans of the Napoleonic Wars (Lejeune, 2016).

However, apart from these early instances, autobiographies have been composed by a wide array of individuals from history.

In the early 20th century, the genre witnessed major transformations, and autobiographies started to cover a broader spectrum of experiences, including trauma, struggles, and successes.

‘Black Boy’ by Richard Wright, for instance, shares the author’s experiences with racism and his journey towards developing a literary career (Wright, 1945).

This was followed by a host of autobiographies by public figures sharing their diverse stories, such as Ernest Hemingway’s ‘A Moveable Feast’, depicting his days as a struggling young writer in Paris (Hemingway, 1964).

Autobiography as a genre has continued to evolve over the years, and a variety of forms have emerged to communicate individual experiences globally.

As history has progressed, we see more and more people with diverse perspectives sharing their stories, broadening our understanding of the human experience (Smith & Watson, 2010).

Key Characteristics of Autobiographies

Examples of autobiographies.

Title: Long Walk to Freedom Author: Nelson Mandela Description: “Long Walk to Freedom” provides an in-depth exploration of ex-President Nelson Mandela, his political journey, and his stand against apartheid in South Africa. The biography offers a unique perspective into Mandela’s noble character, his indomitable spirit, and his commitment to justice when faced with grave adversities (Mandela, 1995). Mandela serves as one of our times’ great moral and political leaders through this biography.

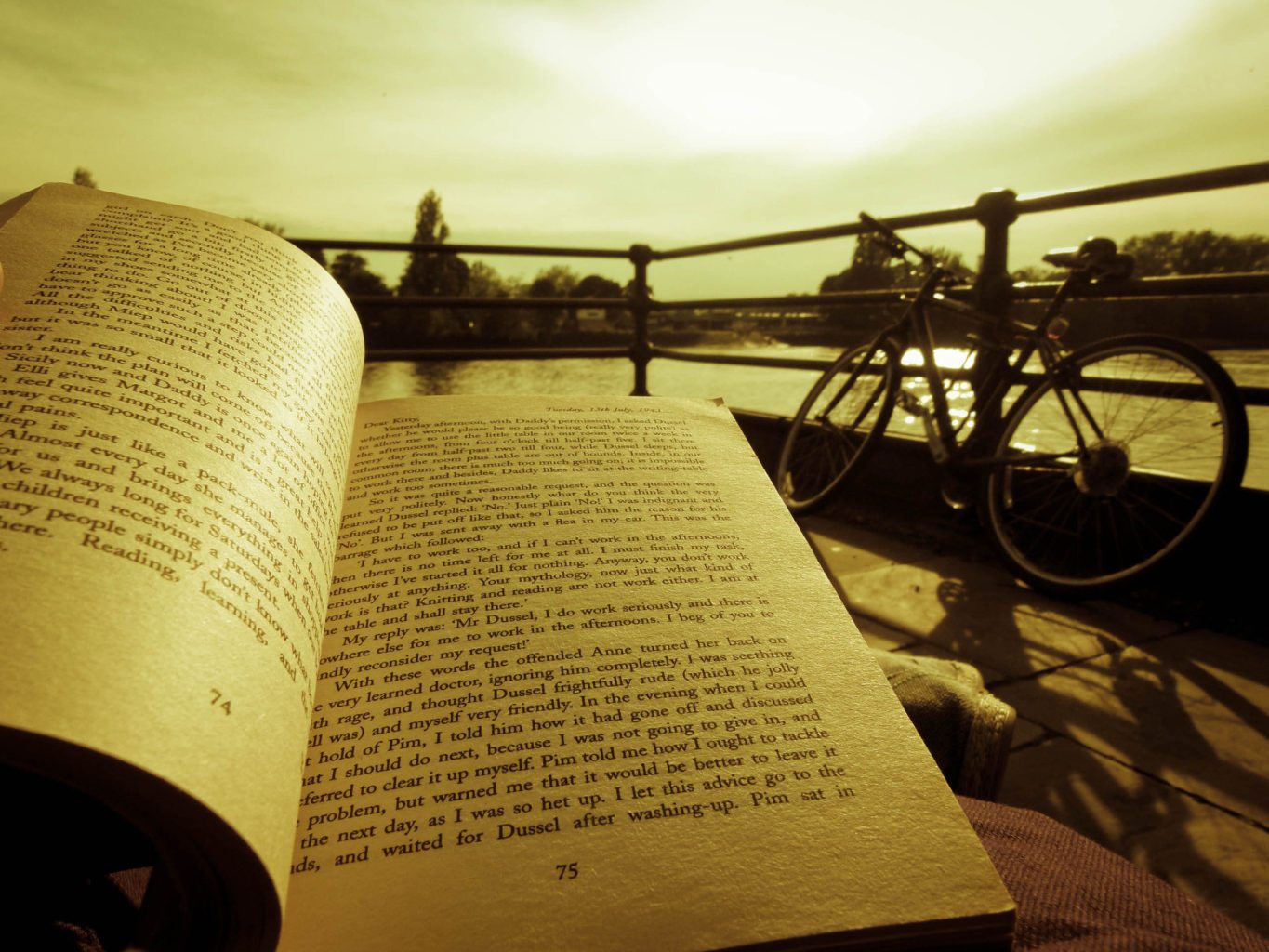

Title: The Diary of a Young Girl Author: Anne Frank Description: This biography provides a startling firsthand account of a young Jewish girl named Anne Frank, who with her family, hid from the Nazis in Amsterdam during World War II. Her diary entries offer profound insights into the fear, hope, and resilience she demonstrated during her two years in hiding (Frank, 1947). Frank’s posthumous biographical record serves as a reminder of the injustices of the past and as a symbol of endurance in the face of oppression.

Title: I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings Author: Maya Angelou Description: This moving autobiography charts Maya Angelou’s early life, from experiencing racial discrimination in the South to becoming the first black streetcar conductor in San Francisco. Angelou portrays her journey of self-discovery and overcoming traumatic experiences, including racial prejudice and personal trauma, with remarkable strength and grace. Her story is one of resilience, and it speaks powerfully about finding one’s voice (Angelou, 1969).

Title: Night Author: Elie Wiesel Description: “Night” is Wiesel’s personal account of his experiences in Nazi concentration camps during World War II with his father. This heartbreaking narrative describes not only physical hardship and cruel atrocities but also examines the loss of innocence and the struggle to maintain faith in humanity. It stands as a testament to human resilience in the face of unimaginable horror (Wiesel, 1960).

Title: Dreams from My Father Author: Barack Obama Description: In this engaging memoir, the 44th President of the United States narrates the story of his diverse background and early life. The narrative extends from his birth in Hawaii to his first visit to Kenya, from dealing with racial identity to self-discovery. “Dreams from My Father” not only provides personal insights about Obama’s life and values but also discusses issues of race, identity, and purpose (Obama, 1995).

Similarities and Differences Between Biographies and Autobiographies

While both biographies and autobiographies are excellent sources of information and entertainment about significant figures in history (or the present!), they serve different purposes. By knowing the different purposes of each, we can develop stronger media literacy , understanding what the intention of the author is, and how we should approach the text.

Angelou, M. (1969). I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings . Random House.

Baker, J., Davis, E., & Thompson, K. (2013). Reflection and Emotions in Autobiography . Chicago University Press.

Boswell, J. (1791). The Life of Samuel Johnson . J.R. Taylor.

Brown, J., & Brown, S. (2018). Thematic Focus in Autobiography Writing . Princeton University Press.

Chernow, R. (2004). Alexander Hamilton . Penguin Books.

Ditchfield, S. (2018). Extracting the Domestic from the Didactic: Transmission and Translation of the Sacred in The Lives of the Ancient Fathers (1672–1675). Church History and Religious Culture, 98 (1), 28-50.

Eakin, P. J. (2015). How Our Lives Become Stories: Making Selves . Cornell University Press.

Frank, A. (1947). The Diary of a Young Girl . Contact Publishing.

Hemingway, E. (1964). A Moveable Feast . Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Isaacson, W. (2011). Steve Jobs . Simon & Schuster.

Johnson, M., & Johnson, S. (2017). A Comprehensive Guide to Biography Writing . New York: Penguin.

Johnson, S. (1781). The Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets . Printed by C. Bathurst, J. Buckland [and 28 others in London].

Jones, B. (2015). The Art of Writing Biographies: An Objective Approach . Oxford University Press.

Lejeune, P. (2016). On Autobiography . University of Minnesota Press.

Mandela, N. (1995). Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela . Macdonald Purnell.

Miller, R. (2014). The Self as the Subject: Autobiography Writing . Stanford University Press.

Morris, E. (1979). The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt . Coward, McCann & Geoghegan.

Obama, B. (1995). Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance . Crown Publishing Group.

Schiffrin D., & Brockmeier J. (2012). Narrative Identity and Autobiographical Recall. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements, 70 , 113-144.

Smith, J., Davis, M., & Thompson, S. (2012). Third Party Narratives: An Exploration of Biography Writing . Cambridge University Press.

Smith, S., & Watson, J. (2010). Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives . University of Minnesota Press.

Sweet, R. (2010). Biographical Dictionaries and Historiography. Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance, 72 (2), 355–368.

Wiesel, E. (1960). Night . Hill & Wang.

Williams, T. (2019). The Importance of Facts in Biographies . HarperCollins.

Wright, R. (1945). Black Boy: A Record of Childhood and Youth . Harper & Brothers.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

11 Reasons to Read Biographies and Autobiographies

Pandemic. Quarantine. Stay at home orders.

You may find yourself in current situations where circumstances have placed you with time on your hands. A profitable way to spend that surplus time is reading. Reading biography and autobiography can be thought of as an investment in self-knowledge. An investment in knowledge pays a high dividend.

People say that life is the thing, but I prefer reading.

Logan Pearsall Smith

Here are some reasons to keep in mind as you read a biography.

We can role-play our way to a better us.

Welearn by imitation. By borrowing the brain and trying on the exceptional character attributes of others, we can rehearse our own new and improved selves.

In my whole life, I have known no wise people (over a broad subject matter area) who didn’t read all the time — none. Zero.

Charlie Munger

They provide a safe, risk-free playground for learning.

Life is the art of drawing without an eraser. You can’t unring a bell. It’s better t anticipate and avoid self inflicted mistakes.

Winging it can be a high stakes endeavor. Better to work through a simulation first.

You can pound your head against the wall trying to think of original ideas or you can cheat by reading them in books.

If you haven’t read hundreds of books, you are functionally illiterate, and you will be incompetent, because your personal experiences alone aren’t broad enough to sustain you.

General James “Mad Dog” Mattis

Reading the lives of others can provide a playbook for how to deal with all kinds of situations. We can see how their responses panned out.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes. We can be pretty sure that we will encounter similar situations. Having thought about them ahead of time can give us an advantage of not being ambushed when the shit hits the fan.

“Only a fool learns from his own mistakes. The wise man learns from the mistakes of others.”

― Otto von Bismarck

We can develop a repertoire of actions and responses.

As Norman Douglas said,

“There are some things you can’t learn from others. You have to pass through the fire.”

All other things are best anticipated and prepared for.

Biographies allow us to test our mettle by figuring out how best to navigate and negotiate situations in a risk-free environment. Because human behavior follows relatively predictable patterns, we can learn from other’s circumstances and mistakes. We can unpack complex situations into components for future actionable reference.

They allow us to invert the harsh lessons of experience.

Mental models improve how we think by helping us to simplify complexity and better understand life.

Inversion is one of the most powerful mental models. Invert means to turn upside down. As a thinking tool, inversion helps to identify and eliminate obstacles by tackling them from the opposite end of the natural starting point.

The Cy Young-winning baseball pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates Vernon Sanders Law said, “Experience is a hard teacher because she gives the test first, the lesson afterwards.” I have found that thought a profound expression of the human experience. Yogi Berra isn’t the only sage of baseball.

Have you ever come up with the best response after an event has passed? I bet you have. We all have. I often think of the perfect comeback line or thing I could have done after the moment has passed, and I looked less than brilliant. (more like a complete dumb-ass)

It’s at moments like that I wish I had a time machine and could go back and deliver the coup de grace. Immersing ourselves in other people’s lives is the next best thing to the time machine. We can note how we would best respond to a situation and use it when the situation arises.

Reading biographies allows you to reverse the chronology and absorb the lesson so you can anticipate a better response when you encounter a similar situation.

Mark Twain — ‘The man who does not read has no advantage over the man who cannot read.’

They help us practice and develop empathy and Emotional Intelligence.

Emotional Intelligence is the capability to recognize your own and other people’s emotions. Reading can help us not only identify but develop the vocabulary to describe and discuss emotional realties. This superpower can help us avoid beaucoup tragic missteps in our lives.

We use emotional information to guide our thinking and behavior. We need to be able to manage and adjust our emotions to adapt to different settings.

To get on in the world and achieve our goals, its crucial to be appropriately social.

Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of others. Empathy is our ability to project into others’ situations and experience their trials and tribulations as our own.

In reading a biography, we can tend to gloss over the trials and tribulations of the subject. We learn how they were shunned and criticized and ignored or ridiculed; they had diseases and illness, poverty and financial hardship, or surrounded by war and death.

We read these things and put them into the category of the stuff they had to overcome. Because we know the end of the story: that they triumphed either in life or after with fame and glory, we diminish the immediate impact of these things that they must have felt.

In retrospect, the good ending seems inevitable. That was not the lived experience.

Pausing to reflect and feel that impact allows us to develop our capacity for empathy and the understanding of others’ experiences.

They help us see further.

In 1675 Isaac Newton wrote to his good friend and colleague, the great polymath Robert Hooke,

“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Reading biographies captures that experience. Biographies allow you to see further by vicariously experiencing what others have gone through and achieved. The practice is an efficient way to gain life lessons.

This idea of standing on the shoulders of giants didn’t originate with Newton. The original attribution of this is from Bernard of Chartres in the early 12th Century as recorded by John of Salisbury:

“Bernard of Chartres used to say that we [the Moderns] are like dwarves perched on the shoulders of giants [the Ancients], and thus we are able to see more and farther than the latter. And this is not at all because of the acuteness of our sight or the stature of our body, but because we are carried aloft and elevated by the magnitude of the giants.”

Newton was an avid reader. Reading is what separates us from other animals. Reading is how we transmit and assimilate the collective Intelligence of humanity. We don’t rely on our innate knowledge and abilities. We can access the hard-won lessons of the wisest and most able.

Biography reminds us of the cyclical nature of events.

The philosopher George Santayana wrote, “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” There is not much new under the sun, and we risk repeating mistakes others have made before us if we are not aware of them. If we make ourselves aware, we can hopefully avoid them.

A cautionary tale can help us recognize and avoid potentially bad situations. And biographies allow us to rehearse navigating these challenging situations in a riskless way from the safety and comfort of our armchair while sipping herbal tea.

Knowledge in advance enables us to be prepared. Preparation prevents piss poor performance.

To be forewarned is to be forearmed. This expression originated as a Latin proverb, Praemonitus, praemunitus , which was translated into English by the early 1500s.

But there are caveats. Foresight may help us, but I want to temper this point because sometimes events are outside of our control and may proceed even if we are aware of the probable outcome. It’s like watching an accident unfold in slow motion.

“Those who don’t study history are doomed to repeat it. Yet those who do study history are doomed to stand by helplessly while everyone else repeats it.” When events take this type of turn, it’s probably better to put down the biography and read stoic philosophy and swap the tea for scotch.

They promote and encourage self-discovery.

Biographies are chock full of teachable moments, some positive, inspirational and aspirational, and many that are cautionary. Ideas and approaches to life reveal themselves through biographical narratives.

Experiential learning through stories is more impactful and satisfying, and more memorable than reading a list of normative steps in a textbook.

They help us look at the world from novel angles.

We need a diversity of ideas and experience to break out of our creative ruts. Transformative ideas and revolutionary innovations come from lateral thinking where we transpose a concept from one field to another or combine ideas in new and non-obvious ways. At the very least it will make you more interesting at a dinner party.

Biography is a resource for developing this superpower.

They provide us with world-class mentors.

When you read a biography or autobiography, you get a glimpse into the subject’s mind and gain the advantage of “knowing” them. They become mentors as we ponder about what advice they offer related to the situations we face.

Reading autobiography allows you to borrow someone else’s brain.

Parting thought

“Books are the quietest and most constant of friends; they are the most accessible and wisest of counselors, and the most patient of teachers.”

― Charles W. Eliot

Receive my 7 day email course

Take your finance skills to the next level with my 7-day corporate finance email course. You'll learn all the essential topics from financial analysis to risk management in a fun, engaging format. Each day, you'll receive an email with practical examples, exercises and resources. Perfect for aspiring finance pros or anyone looking to expand their knowledge. Get ready to transform your finance game!

If you like this article. Here are some more articles I think you might like.

The Road to Becoming a Unicorn: A Quick Guide to Startup Funding Rounds

Oh Behave! Behavioral Economics: Why we do what we do.

Professional Development: 3 Types of Skill Sets

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Biography and Autobiography

Introduction, general theoretical overviews and textbooks.

- Ancient and Premodern Periods

- 16th–19th Centuries

- 20th–21st Centuries

- Interviews and Recordings

- Foreign-Language Journals

- Autobiography and Memoir

- Letters and Diaries

- Holocaust Representations

- Audio/Visual Life Narrative

- Digital Life Narrative

- Fiction, Fact, and Life Narrative

- Literary Selves and Authorship

- Historical, Political, and Ethical Contexts

- Religion, War, Migration and Travel, Family

- Identity Interests and Claims

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Edmund Gosse

- Irish Life Writing

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Children's Literature and Young Adult Literature in Ireland

- John Banville

- Shakespeare's Language

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Biography and Autobiography by Margaretta Jolly LAST REVIEWED: 26 July 2017 LAST MODIFIED: 26 July 2017 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199846719-0006

The history of life writing reflects the history of selfhood itself, particularly as it has tracked the rise of individualism and, arguably, individuality. Biography, the interpretation of another’s life, is an ancient form with roots in religious and royal accounts and can be found in all civilizations, although its didactic and moral emphasis has slowly faded in favor of debunking approaches. Autobiography is generally argued to arise in modernizing societies where the individual’s perspective gains cultural value, and has been linked to deep questions of self-awareness, self-division, and self-performance. The romantic period crystallized this relationship as well as linked life writing to a new cult of the author. In the context of late modern culture, life narrative has become still more autobiographical than biographical, an everyday practice of confession and self-styling. However, biography and autobiography are not always distinct. Memoir can focus on another or oneself and has become the preferred term for literary autobiography in the early 21st century, arguably because current tastes are for stories of intimate relationship in which elements of biography and autobiography come together. Critics have therefore become interested in the inevitable dependency of one’s own story on another’s, a subject of ethical trouble but aesthetic, intellectual, and political fascination. Such “auto/biographies” express a range of relationships, from the ghostwriter’s service to a public figure’s memoir, to the ethnographer’s or doctor’s view of a person as case history. More often, family relations are the grounds on which the complexities of representational contracts are played out. This negotiation relates to a second defining aspect of life narrative: the reader’s expectation that it be true. “Memory is a great artist,” claimed a great autobiographical experimenter, André Malraux, and an enduring critical question has been whether life writing can be both artful and historically accurate. Increasingly, however, scholars broaden from such aesthetic debates to consider the social, political, and psychological work of life narrative. Readers will therefore find that this article pushes out from the literary to encompass a capacious field of inquiry that includes social scientists interested in narrative or biographical methods, and interdisciplinary studies of personal storytelling in the contexts of human rights activism or, conversely, of the late capitalist trade in celebrity or exotic lives and digital cultures of self-publication. For literary critics, therefore, biography and autobiography are now generally appreciated as two genres within a bigger field of life writing, life narrative, or life story about self-other relations, although they remain touchstones for those interested in how life experience can be aestheticized.

Life narrative is found in all places and historical periods and encompasses many aspects of everyday speech as well as writing. It is therefore difficult to produce a definitive criticism, and the texts listed here divide between those with a more literary and a more sociological focus. From a literary or cultural-studies perspective, Smith and Watson 2010 provides the most condensed overview and builds on an important body of joint work by these North American scholars, particularly on the global, postcolonial, and feminist face of much life writing. Jolly 2001 remains the most internationally comprehensive guide, with analytical surveys and bibliographies of life narrative in all major continents and countries, from classical periods to the early 21st century. Broughton 2006 , an anthology that provides a selection of key critical interventions, also features an excellent introduction in which the author interprets the shifting critical emphasis from the life to the self. Marcus 1994 , written by another British critic, offers a more extended tracing of this “discourse” about auto/biography. The author’s brilliant thesis is that the genre has been the ground for fantasies about self-alienation in modernity and, conversely, for redemptive healing of its splits. Plummer 2001 approaches life stories from this redemptive point of view, as a sociologist in what the author defines as a radical humanist tradition, and also a gay man who has studied as well as lived the coming-out story. Harrison 2009 , also written by a sociologist, is an edited collection that points out the growth in narrative and biographical research methods for social scientists. Life narrative is inherently suitable for teaching both as method and topic with unique pulling power and accessibility. Fuchs and Howes 2008 , another edited collection of essays, is extremely useful for any would-be teachers, offering case studies, lesson plans, and syllabi, including from South Africa and Chad. Chansky and Hipchen 2016 offers carefully edited and organized selected essays tracing key debates in a one-stop volume that marks the multidisciplinary, multimediated direction of the field. Finally, the International Auto/Biography Association (IABA), launched in 1999 at Peking University by Zhao Baisheng, hosts a global network of scholars through biannual conferences around the world, a listserv managed by the Center for Biographical Research at the University of Hawai‘i, and a website hosted by Julie Rak at the University of Alberta. Zhao also edits a Chinese-language list of short biographies and has written a short book arguing that auto/biography is a field of literature that deserves to be an object of study in its own right. Limited bibliographic details for this show that, as of yet, such initiatives and English-language-based scholarship are not sufficiently integrated.

Broughton, Trev Lynn ed. Autobiography: Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies . 4 vols. London: Routledge, 2006.

Four-volume anthology of important critical texts from the 18th century onward, with an incisive introduction. Organized in eight parts within four volumes: Part 1, “Founding Statements”; Part 2, “Beyond Truth versus Fiction”; Part 3, “Discovering Difference”; Part 4, “Personal Stories, Hidden Histories”; Part 5, “Psychology, Psychoanalysis, and the Narrability of Lives”; Part 6, “Autobiography as Critique”; Part 7, “Personal Texts as Autobiography”; and Part 8, “Cultures of Life Writing.”

Chansky, Ricia Anne, and Emily Hipchen, eds. The Routledge Auto|Biography Studies Reader . Routledge Literature Readers. London and New York: Routledge, 2016.

One-volume anthology principally selected from the archives of the a/b: Auto/Biography Studies journal. Organized by school of thought, from debates about genre/canon to those of political identity and representation to early-21st-century concerns with medical humanities, postmemory, animalographies, graphic narrative, celebrity lives, and digital biography.

Fuchs, Miriam, and Craig Howes, eds. Teaching Life Writing Texts . New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2008.

Commissioned by the Modern Language Association of America’s prestigious teaching text series; signifies the academic integration of life-writing studies. Containing over forty-four short articles on teaching specific texts or genres, some with lesson plans, this work is a practical and inspiring teaching resource. Internationally focused.

Harrison, Barbara, ed. Life Story Research . 4 vols. London: SAGE, 2009.

Four volumes on methodological approaches within the social sciences in which research foregrounds the individual. Useful for related fields (nursing, criminology, cultural studies). Organized as five parts within four volumes: Part 1, “Historical Origins and Trajectories”; Part 2, “Theoretical and Conceptual Issues in Life Story Research”; Part 3, “Types of Life Story Research: Traditional and New Sources of Life Story Data”; Part 4, “Doing Life Story Research”; and Part 5, “Research Contexts and Life Stories.”

International Auto/Biography Association .

Founded in 1999 as a multidisciplinary network of auto/biographers, scholars, and readers to pursue global dialogues on life writing. IABA’s first conference took place at Peking University; it has met biannually since then in China, Canada, Australia, Hong Kong, Germany, Hawaii, England, Cyprus, and Brazil.

Jolly, Margaretta, ed. The Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms . 2 vols. London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2001.

First and still only encyclopedia in English on life writing and life narrative. Two large volumes include entries on important writers, genres, and subgenres. Entries encompass, for example, confession, obituary, and gossip; portraits; surveys of national and regional traditions from all continents and periods; and themes such as shame, adolescence, time, and self.

Marcus, Laura. Auto/Biographical Discourses: Theory, Criticism, Practice . Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1994.

Brilliant intellectual and literary history of the ways that life writing from the 18th century to the 1990s has been conceptualized by writers, critics, philosophers, and journalists. Marcus rejects the idea that there is a stable genre of autobiography, but she proposes that there is, instead, a distinct genre of autobiographical criticism.

Plummer, Kenneth. Documents of Life 2: An Invitation to a Critical Humanism . 2d ed. London: SAGE, 2001.

DOI: 10.4135/9781849208888

A highly readable guide to life writing and life story as objects and methods of analysis from a sociological but also literary perspective, with a particularly useful section on interviewing. This edition substantially revises and improves Plummer’s original publication in 1983 while continuing to argue that radical humanism is life writing’s appropriate philosophical framework.

Smith, Sidonie, and Julia Watson. Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives . 2d ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Authoritative, accessible guide to the cultural study of life narrative across genre, period, and place, with good attention to non-Western texts. Includes chapters on early-21st-century life narrative and visual-verbal-virtual forms, as well as a “tool kit” consisting of twenty-four strategies for reading life narratives, classroom projects, and a list of Internet resources.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About British and Irish Literature »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abbey Theatre

- Adapting Shakespeare

- Alfred (King)

- Alliterative Verse

- Ancrene Wisse, and the Katherine and Wooing Groups

- Anglo-Irish Poetry, 1500–1800

- Anglo-Saxon Hagiography

- Arthurian Literature

- Austen, Jane

- Ballard, J. G.

- Barnes, Julian

- Beckett, Samuel

- Behn, Aphra

- Biblical Literature

- Biography and Autobiography

- Blake, William

- Bloomsbury Group

- Bowen, Elizabeth

- Brontë, Anne

- Brooke-Rose, Christine

- Browne, Thomas

- Burgess, Anthony

- Burney, Frances

- Burns, Robert

- Butler, Hubert

- Byron, Lord

- Carroll, Lewis

- Carter, Angela

- Catholic Literature

- Celtic and Irish Revival

- Chatterton, Thomas

- Chaucer, Geoffrey

- Chorographical and Landscape Writing

- Coffeehouse

- Congreve, William

- Conrad, Joseph

- Crime Fiction

- Defoe, Daniel

- Dickens, Charles

- Donne, John

- Drama, Northern Irish

- Drayton, Michael

- Early Modern Prose, 1500-1650

- Eighteenth-Century Novel

- Eliot, George

- English Bible and Literature, The

- English Civil War / War of the Three Kingdoms

- English Reformation Literature

- Epistolatory Novel, The

- Erotic, Obscene, and Pornographic Writing, 1660-1900

- Ferrier, Susan

- Fielding, Henry

- Ford, Ford Madox

- French Revolution, 1789–1799

- Friel, Brian

- Gascoigne, George

- Globe Theatre

- Golding, William

- Goldsmith, Oliver

- Gosse, Edmund

- Gower, John

- Gray, Thomas

- Gunpowder Plot (1605), The

- Hardy, Thomas

- Heaney, Seamus

- Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey

- Herbert, George

- Highlands, The

- Hogg, James

- Holmes, Sherlock

- Hopkins, Gerard Manley

- Hurd, Richard

- Ireland and Memory Studies

- Irish Crime Fiction

- Irish Famine, Writing of the

- Irish Gothic Tradition

- Irish Literature and the Union with Britain, 1801-1921

- Irish Modernism

- Irish Poetry of the First World War

- Irish Short Story, The

- Irish Travel Writing

- Johnson, B. S.

- Johnson, Samuel

- Jones, David

- Jonson, Ben

- Joyce, James

- Keats, John

- Kelman, James

- Kempe, Margery

- Lamb, Charles and Mary

- Larkin, Philip

- Law, Medieval

- Lawrence, D. H.

- Literature, Neo-Latin

- Literature of the Bardic Revival

- Literature of the Irish Civil War

- Literature of the 'Thirties

- MacDiarmid, Hugh

- MacPherson, James

- Malory, Thomas

- Marlowe, Christopher

- Marvell, Andrew

- Mary Shelley's Frankenstein

- McEwan, Ian

- McGuckian, Medbh

- Medieval Lyrics

- Medieval Manuscripts

- Medieval Scottish Poetry

- Medieval Sermons

- Middleton, Thomas

- Milton, John

- Miéville, China

- Morality Plays

- Morris, William

- Muir, Edwin

- Muldoon, Paul

- Ní Chuilleanáin, Eiléan

- Nonsense Literature

- Novel, Contemporary British

- Novel, The Contemporary Irish

- O’Casey, Sean

- O'Connor, Frank

- O’Faoláin, Seán

- Old English Literature

- Percy, Thomas

- Piers Plowman

- Pope, Alexander

- Postmodernism

- Post-War Irish Drama

- Post-war Irish Writing

- Pre-Raphaelites

- Prosody and Meter: Early Modern to 19th Century

- Prosody and Meter: Twentieth Century

- Psychoanalysis

- Quincey, Thomas De

- Ralegh (Raleigh), Sir Walter

- Ramsay, Allan and Robert Fergusson

- Revenge Tragedy

- Richardson, Samuel

- Rise of the Novel in Britain, 1660–1780, The

- Robin Hood Literature

- Romance, Medieval English

- Romanticism

- Ruskin, John

- Science Fiction

- Scott, Walter

- Shakespeare in Translation

- Shakespeare, William

- Shaw, George Bernard

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe

- Sidney, Mary, Countess of Pembroke

- Sinclair, Iain

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

- Smollett, Tobias

- Sonnet and Sonnet Sequence

- Spenser, Edmund

- Sterne, Laurence

- Swift, Jonathan

- Synge, John Millington

- Thomas, Dylan

- Thomas, R. S.

- Tóibín, Colm

- Travel Writing

- Trollope, Anthony

- Tudor Literature

- Twenty-First-Century Irish Prose

- Urban Literature

- Utopian and Dystopian Literature to 1800

- Vampire Fiction

- Verse Satire from the Renaissance to the Romantic Period

- Webster, John

- Welsh, Irvine

- Welsh Poetry, Medieval

- Welsh Writing Before 1500

- Wilmot, John, Second Earl of Rochester

- Wollstonecraft, Mary

- Wollstonecraft Shelley, Mary

- Wordsworth, William

- Writing and Evolutionary Theory

- Wulfstan, Archbishop of York

- Wyatt, Thomas

- Yeats, W. B.

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.154]

- 81.177.182.154

Why I think autobiographies are important

Nowadays, when you think of autobiographies, you probably think of reality TV stars. You probably associate autobiographies as those books that are churned out around Christmas time; one of the presents that every year your nan insists is a staple gift. With some celebrities releasing what appears to be a new autobiography every year, I would not blame you for not being interested in the genre.

The purpose of an autobiography is to give you a first-hand account into the life of the person you are reading about, and to give you a better insight into how their experiences have shaped them as a person. The process of writing an autobiography, I assume, would include a large degree of soul-searching and effort on the part of the individual. So now, as it becomes increasingly apparent that many celebrities do not even write the autobiographies they are rolling out, it is easy to see why so many are becoming disillusioned with the category.

The purpose of an autobiography is to give you a first-hand account into the life of the person you are reading about, and to give you a better insight into how their experiences have shaped them as a person

However, modern autobiographies can also provide an interesting outsider-looking-in perspective. David Niven’s The Moon’s a Balloon is frequently credited as one of the best autobiographies ever written. But what I think is truly crucial to note in the case of Niven and of other well-respected autobiographies, is that most of these truly wonderful autobiographies were written by people in their later years. Niven was 61 when he wrote his memoirs. He starts the book in his early childhood, and ends it in his much later years. Niven had lived for long enough to start documenting the interesting twists and turns his life had taken.

Some books that you wouldn’t even have considered, such as The Diary of Anne Frank , constitute as autobiographies

But in the case of so many modern day examples, have the individuals in question really lived long enough to tell their story to the world? Katie Price has released five autobiographies. Five. On average, she releases one every three years. I highly doubt that enough happens in three years of Katie Price’s life that she needs a whole new book dedicated to the subject. Similarly, I doubt that Ferne from TOWIE has had enough life experience to fully be able to reflect on it now in her twenties. I’m currently 19, and I’m not sure people would be particularly overwhelmed to read my autobiography about my struggles in leaping from GCSE to A Level.

My point is, when you next happen to find yourself in a bookshop, do not let the table of Geordie Shore stars’ autobiographies turn you away from the section entirely. Browse the shelves and find someone who you have a genuine interest in. Let’s bring back some credibility to the genre. Autobiographies can allow a person to understand another person’s life through their eyes. It is for this reason that I believe autobiographies are still a credible section of literature, and that the modern tarnish smearing the genre is unmerited.

Image Credits: Hector Moral / Flickr (Header), Andrew Scott / Flickr (Image 1)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

(page 1) p. 1 Introduction

- Published: July 2018

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Autobiography continues to be one of the most popular forms of writing, produced by authors from across the social and professional spectrum. It is also central to the work of literary critics, philosophers, historians, and psychologists, who have found in autobiographies not only an understanding of the ways in which lives have been lived, but the most fundamental accounts of what it means to be a self in the world. The Introduction describes what autobiography means and compares it to other forms of ‘life-writing’. Autobiographical writing is seen to act as a window on to concepts of self, identity, and subjectivity, and into the ways in which these are themselves determined by time and circumstance.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

The Purpose of Biography

‘WHAT is biography for? What useful purpose does it serve? Why should one write it? What is its actual importance in the field of literature? Above all, what is autobiography for, and what proper motive might one have for writing it?’

I put these questions to one of my literary acquaintances the other day, in the hope of clearing my own mind. It has once or twice been suggested to me (as I suppose it has been suggested to everybody who has ever published anything) that I should write the biography of this-or-that eminent person. My instinct promptly jibbed at the suggestion; and in each case, after dallying with the idea awhile, I threw it over. Then latterly, while looking into one or two current biographies, I was moved to wonder what prompted my instinct. Was it the consciousness of incapacity or of laziness or of both? Probably both, to a degree; yet I thought there must be a little more to it than that, because I had already caught myself pondering the question why these biographies had been written. I could not see that they served any purpose worth serving; they seemed to me to be addressed mostly to a vulgar and prying inquisitiveness; and this in turn led me to raise the questions which I subsequently put to my literary friend.

We finally agreed, my friend and I, that the legitimate function of modern biography (and a fortiori of autobiography) is to help the historian. We recalled the fact that biography, as now understood, is comparatively a new thing in our literature. Neither of us could put our finger on an example of it earlier than the seventeenth century. In principle, modern biography is an objective account of the life of one man. It begins with his birth, ends with his death, and includes every item of detail which has any actual or probable historical significance. All collateral matter which goes in by way of ‘setting’ should be cut down to what is in distinct and direct relation to that one man. In principle, above all, modern biography admits of nothing tendentious, nor does it admit of the puffing out or slighting of detail to any degree beyond what the author, in all good faith and conscience, believes the historical importance of that detail would warrant.

If biographical practice followed principle, obviously, fewer biographies would be written, far fewer autobiographies, and far few’er of either would be generally read; the only person likely to profit by them would be the historian. Things being as they are, however, commercial considerations intervene between principle and practice, as they always do. Publishers look with a jaundiced eye on a biography which in their view is not ‘readable’; and their view of what is readable is set by what experience has shown to be the terms of popular demand. The author, under a double pressure to produce a readable book, — for most authors are not above some little thought of profit, — sees that the satisfaction of these terms is quite incompatible with a devotion to principle, and proceeds accordingly.