Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples

What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples

Published on May 30, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Critical thinking is the ability to effectively analyze information and form a judgment .

To think critically, you must be aware of your own biases and assumptions when encountering information, and apply consistent standards when evaluating sources .

Critical thinking skills help you to:

- Identify credible sources

- Evaluate and respond to arguments

- Assess alternative viewpoints

- Test hypotheses against relevant criteria

Table of contents

Why is critical thinking important, critical thinking examples, how to think critically, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about critical thinking.

Critical thinking is important for making judgments about sources of information and forming your own arguments. It emphasizes a rational, objective, and self-aware approach that can help you to identify credible sources and strengthen your conclusions.

Critical thinking is important in all disciplines and throughout all stages of the research process . The types of evidence used in the sciences and in the humanities may differ, but critical thinking skills are relevant to both.

In academic writing , critical thinking can help you to determine whether a source:

- Is free from research bias

- Provides evidence to support its research findings

- Considers alternative viewpoints

Outside of academia, critical thinking goes hand in hand with information literacy to help you form opinions rationally and engage independently and critically with popular media.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Critical thinking can help you to identify reliable sources of information that you can cite in your research paper . It can also guide your own research methods and inform your own arguments.

Outside of academia, critical thinking can help you to be aware of both your own and others’ biases and assumptions.

Academic examples

However, when you compare the findings of the study with other current research, you determine that the results seem improbable. You analyze the paper again, consulting the sources it cites.

You notice that the research was funded by the pharmaceutical company that created the treatment. Because of this, you view its results skeptically and determine that more independent research is necessary to confirm or refute them. Example: Poor critical thinking in an academic context You’re researching a paper on the impact wireless technology has had on developing countries that previously did not have large-scale communications infrastructure. You read an article that seems to confirm your hypothesis: the impact is mainly positive. Rather than evaluating the research methodology, you accept the findings uncritically.

Nonacademic examples

However, you decide to compare this review article with consumer reviews on a different site. You find that these reviews are not as positive. Some customers have had problems installing the alarm, and some have noted that it activates for no apparent reason.

You revisit the original review article. You notice that the words “sponsored content” appear in small print under the article title. Based on this, you conclude that the review is advertising and is therefore not an unbiased source. Example: Poor critical thinking in a nonacademic context You support a candidate in an upcoming election. You visit an online news site affiliated with their political party and read an article that criticizes their opponent. The article claims that the opponent is inexperienced in politics. You accept this without evidence, because it fits your preconceptions about the opponent.

There is no single way to think critically. How you engage with information will depend on the type of source you’re using and the information you need.

However, you can engage with sources in a systematic and critical way by asking certain questions when you encounter information. Like the CRAAP test , these questions focus on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

When encountering information, ask:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert in their field?

- What do they say? Is their argument clear? Can you summarize it?

- When did they say this? Is the source current?

- Where is the information published? Is it an academic article? Is it peer-reviewed ?

- Why did the author publish it? What is their motivation?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence? Does it rely on opinion, speculation, or appeals to emotion ? Do they address alternative arguments?

Critical thinking also involves being aware of your own biases, not only those of others. When you make an argument or draw your own conclusions, you can ask similar questions about your own writing:

- Am I only considering evidence that supports my preconceptions?

- Is my argument expressed clearly and backed up with credible sources?

- Would I be convinced by this argument coming from someone else?

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

Critical thinking skills include the ability to:

You can assess information and arguments critically by asking certain questions about the source. You can use the CRAAP test , focusing on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

Ask questions such as:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence?

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Information literacy refers to a broad range of skills, including the ability to find, evaluate, and use sources of information effectively.

Being information literate means that you:

- Know how to find credible sources

- Use relevant sources to inform your research

- Understand what constitutes plagiarism

- Know how to cite your sources correctly

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search, interpret, and recall information in a way that aligns with our pre-existing values, opinions, or beliefs. It refers to the ability to recollect information best when it amplifies what we already believe. Relatedly, we tend to forget information that contradicts our opinions.

Although selective recall is a component of confirmation bias, it should not be confused with recall bias.

On the other hand, recall bias refers to the differences in the ability between study participants to recall past events when self-reporting is used. This difference in accuracy or completeness of recollection is not related to beliefs or opinions. Rather, recall bias relates to other factors, such as the length of the recall period, age, and the characteristics of the disease under investigation.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/critical-thinking/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, student guide: information literacy | meaning & examples, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

How to Approach Critical Thinking in This Misinformation Era

Is there any way we can know what's true and what's false.

Posted August 12, 2021 | Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

- Critical thinking is a discipline of thought and communication that boils down to one word: Truth.

- Four classic and time-honored strategies for engaging in critical thinking include asking who is making a statement and exploring biases.

- Reading a book that involves new ideas and concepts can help the brain develop new neural pathways and alternative modes of thinking.

One of the most important disciplines we can practice is the discipline of Critical Thinking. It involves holding a kind of magnifying glass up to our thoughts and the information and data constantly swirling around us.

What’s true and what isn’t? It’s the job of critical thinking to find out.

We are all constantly making decisions. Some of those decisions are trivial and unimportant (Should I wear the blue or yellow shirt today?). But other decisions can affect our very lives and the lives of those around us. We want those decisions to be based on truth so that they have good outcomes. Critical thinking can help make that possible.

Where do we start?

Here are seven questions, thoughts, and strategies to have available at all times to help with our different decision-making processes:

- Who is saying it? Who is it that is proclaiming the idea or thought in question? Are they dependable and truthful? Do you trust what this person says?

- How do they know what it is they are saying? Are they open about how they know what it is they're sharing? Do you trust their route to knowledge? Is it credible and reliable?

- What’s in it for them? Do they have an obvious incentive to promote the idea they’re sharing? Is there a conflict of interest?

- Explore your own biases. Our own personal biases may dispose us to (falsely) accept or reject the idea being presented. A good way to assess our own personal biases is to look at two or three close friends. What are their attitudes toward such things as race, politics , religion, money, family, or personal life values? Our own values or biases may likely be very similar to theirs.

- Remember, the whole point of critical thinking is about finding the truth. Don’t allow yourself to be distracted from seeking and valuing the truth in all areas of your life.

- Read a book about some subject you’re not interested in. This may sound like a strange idea, but in fact, it is beneficial. Read a book involving new ideas and concepts can help your brain develop new neural pathways and alternative modes of thinking. Reading a book filled with unfamiliar material can be like giving your brain a “re-set.”

Almost ten years ago, I undertook just such an experience. I chose a book about the Panama Canal, a topic I had zero interest in. The title was The Path Between the Seas .

I knew it was by an excellent writer (David McCullough), but it was about a subject I was not in the least attracted to.

The book was enthralling! I had never imagined what huge, consequential problems the building of the Panama Canal presented! There were multiple crises involving leadership , manpower, disease, technology, weather, administration, bizarre personalities, feuds, government bureaucracies, and constantly inadequate funding. How could they ever hope to achieve their impossible goal? It was truly a page-turner and is one of my all-time favorite books I always recommend to friends.

And it helped freshen my mind for the critical thinking that is always essential.

The Serenity Prayer

The serenity prayer might seem like a surprising suggestion to aid critical thinking, but I believe it is one of the most important.

Here’s why:

In situations where good critical thinking is essential, we become tangled up emotionally. We may feel that we ought to act decisively, but we don’t know if it will do any good, and there are often complicated constraints against any actions we might take. Then we find ourselves confused, not knowing what to do.

It is in this kind of situation that the Serenity Prayer is so clarifying. Simply stated, the prayer is this:

Lord, help me accept the things I cannot change, give me the courage to change the things I can change, and give me the wisdom to know the difference.

Instead of getting emotionally bogged down in determining what we can or should change, the Serenity Prayer removes ambiguity and brings clarity.

So, critical thinking is an essential life discipline, and these seven strategies can help bring us clarity of thought and understanding.

It's all about truth.

© David Evans

David Evans is an award-winning writer and mediator. He has an Emmy Award (shared) for writing on The Monkees and two Outstanding Case of the Year Awards for The Los Angeles County Court Alternative Dispute Resolution Program.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

E valuating resources often means piecing together clues

This section teaches you how to identify relevant and credible sources that have most likely turned up when searching the Web and on your results pages of the library catalog and specialized databases. Remember you always want to look for relevant, credible sources that will meet the information needs of your research project.

In order to evaluate a source, you have to read and review the information keeping in mind two very important questions:

- Is this source relevant to my research question?

- Is this a credible source– a source my audience and I should be able to believe

Note: As you read an academic paper you will need to determine relevance before credibility because no matter how credible a source is if it’s not relevant to your research question it’s useless to you for this project. Reading research-centric papers can be challenging. Check out the tips in the video below.

UBC iSchool. (2013). How to read an academic paper . https://youtu.be/SKxm2HF_-k0

Happily, you’ll also get faster the more you do it.

Making Inferences: Good Enough for Your Purpose?

Sources should always be evaluated relative to your purpose-why you’re looking for information. But because there often aren’t clear-cut answers when you evaluate sources, most of the time it is inferences, educated guesses from available clues, that you have to make about whether to use information from particular sources.

Your information needs will dictate:

- What kind of information will help?

- How serious you consider the consequences of making a mistake by using information that turns out to be inaccurate. When the consequences aren’t very serious, it’s easier to decide if a source and its information are good enough for your purpose. Of course, there’s a lot to be said for always having accurate information, regardless.

- How hard you’re willing to work to get the credible, timely information that suits your purpose. (What you’re learning here will make it easier.)

Thus, your standards for relevance and credibility may vary, depending on whether you need, say:

- Information about a personal health problem.

- An image you can use on a poster.

- Evidence to win a bet with a rival in the dorm.

- Dates and times a movie is showing locally.

- A game to have fun with.

- Evidence for your argument in a term paper.

For your research assignments or a health problem, the consequences may be great if you use information that is not relevant or not credible.

Evaluating Sources

There are many approaches to evaluating your web and library resources. One that is quite useful is the SIFT process.

Critical Thinking in Academic Research Copyright © 2022 by Cindy Gruwell and Robin Ewing is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

Why Is Critical Thinking Important? A Survival Guide

Updated: December 7, 2023

Published: April 2, 2020

Why is critical thinking important? The decisions that you make affect your quality of life. And if you want to ensure that you live your best, most successful and happy life, you’re going to want to make conscious choices. That can be done with a simple thing known as critical thinking. Here’s how to improve your critical thinking skills and make decisions that you won’t regret.

What Is Critical Thinking?

You’ve surely heard of critical thinking, but you might not be entirely sure what it really means, and that’s because there are many definitions. For the most part, however, we think of critical thinking as the process of analyzing facts in order to form a judgment. Basically, it’s thinking about thinking.

How Has The Definition Evolved Over Time?

The first time critical thinking was documented is believed to be in the teachings of Socrates , recorded by Plato. But throughout history, the definition has changed.

Today it is best understood by philosophers and psychologists and it’s believed to be a highly complex concept. Some insightful modern-day critical thinking definitions include :

- “Reasonable, reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do.”

- “Deciding what’s true and what you should do.”

The Importance Of Critical Thinking

Why is critical thinking important? Good question! Here are a few undeniable reasons why it’s crucial to have these skills.

1. Critical Thinking Is Universal

Critical thinking is a domain-general thinking skill. What does this mean? It means that no matter what path or profession you pursue, these skills will always be relevant and will always be beneficial to your success. They are not specific to any field.

2. Crucial For The Economy

Our future depends on technology, information, and innovation. Critical thinking is needed for our fast-growing economies, to solve problems as quickly and as effectively as possible.

3. Improves Language & Presentation Skills

In order to best express ourselves, we need to know how to think clearly and systematically — meaning practice critical thinking! Critical thinking also means knowing how to break down texts, and in turn, improve our ability to comprehend.

4. Promotes Creativity

By practicing critical thinking, we are allowing ourselves not only to solve problems but also to come up with new and creative ideas to do so. Critical thinking allows us to analyze these ideas and adjust them accordingly.

5. Important For Self-Reflection

Without critical thinking, how can we really live a meaningful life? We need this skill to self-reflect and justify our ways of life and opinions. Critical thinking provides us with the tools to evaluate ourselves in the way that we need to.

6. The Basis Of Science & Democracy

In order to have a democracy and to prove scientific facts, we need critical thinking in the world. Theories must be backed up with knowledge. In order for a society to effectively function, its citizens need to establish opinions about what’s right and wrong (by using critical thinking!).

Benefits Of Critical Thinking

We know that critical thinking is good for society as a whole, but what are some benefits of critical thinking on an individual level? Why is critical thinking important for us?

1. Key For Career Success

Critical thinking is crucial for many career paths. Not just for scientists, but lawyers , doctors, reporters, engineers , accountants, and analysts (among many others) all have to use critical thinking in their positions. In fact, according to the World Economic Forum, critical thinking is one of the most desirable skills to have in the workforce, as it helps analyze information, think outside the box, solve problems with innovative solutions, and plan systematically.

2. Better Decision Making

There’s no doubt about it — critical thinkers make the best choices. Critical thinking helps us deal with everyday problems as they come our way, and very often this thought process is even done subconsciously. It helps us think independently and trust our gut feeling.

3. Can Make You Happier!

While this often goes unnoticed, being in touch with yourself and having a deep understanding of why you think the way you think can really make you happier. Critical thinking can help you better understand yourself, and in turn, help you avoid any kind of negative or limiting beliefs, and focus more on your strengths. Being able to share your thoughts can increase your quality of life.

4. Form Well-Informed Opinions

There is no shortage of information coming at us from all angles. And that’s exactly why we need to use our critical thinking skills and decide for ourselves what to believe. Critical thinking allows us to ensure that our opinions are based on the facts, and help us sort through all that extra noise.

5. Better Citizens

One of the most inspiring critical thinking quotes is by former US president Thomas Jefferson: “An educated citizenry is a vital requisite for our survival as a free people.” What Jefferson is stressing to us here is that critical thinkers make better citizens, as they are able to see the entire picture without getting sucked into biases and propaganda.

6. Improves Relationships

While you may be convinced that being a critical thinker is bound to cause you problems in relationships, this really couldn’t be less true! Being a critical thinker can allow you to better understand the perspective of others, and can help you become more open-minded towards different views.

7. Promotes Curiosity

Critical thinkers are constantly curious about all kinds of things in life, and tend to have a wide range of interests. Critical thinking means constantly asking questions and wanting to know more, about why, what, who, where, when, and everything else that can help them make sense of a situation or concept, never taking anything at face value.

8. Allows For Creativity

Critical thinkers are also highly creative thinkers, and see themselves as limitless when it comes to possibilities. They are constantly looking to take things further, which is crucial in the workforce.

9. Enhances Problem Solving Skills

Those with critical thinking skills tend to solve problems as part of their natural instinct. Critical thinkers are patient and committed to solving the problem, similar to Albert Einstein, one of the best critical thinking examples, who said “It’s not that I’m so smart; it’s just that I stay with problems longer.” Critical thinkers’ enhanced problem-solving skills makes them better at their jobs and better at solving the world’s biggest problems. Like Einstein, they have the potential to literally change the world.

10. An Activity For The Mind

Just like our muscles, in order for them to be strong, our mind also needs to be exercised and challenged. It’s safe to say that critical thinking is almost like an activity for the mind — and it needs to be practiced. Critical thinking encourages the development of many crucial skills such as logical thinking, decision making, and open-mindness.

11. Creates Independence

When we think critically, we think on our own as we trust ourselves more. Critical thinking is key to creating independence, and encouraging students to make their own decisions and form their own opinions.

12. Crucial Life Skill

Critical thinking is crucial not just for learning, but for life overall! Education isn’t just a way to prepare ourselves for life, but it’s pretty much life itself. Learning is a lifelong process that we go through each and every day.

How to Think Critically

Now that you know the benefits of thinking critically, how do you actually do it?

How To Improve Your Critical Thinking

- Define Your Question: When it comes to critical thinking, it’s important to always keep your goal in mind. Know what you’re trying to achieve, and then figure out how to best get there.

- Gather Reliable Information: Make sure that you’re using sources you can trust — biases aside. That’s how a real critical thinker operates!

- Ask The Right Questions: We all know the importance of questions, but be sure that you’re asking the right questions that are going to get you to your answer.

- Look Short & Long Term: When coming up with solutions, think about both the short- and long-term consequences. Both of them are significant in the equation.

- Explore All Sides: There is never just one simple answer, and nothing is black or white. Explore all options and think outside of the box before you come to any conclusions.

How Is Critical Thinking Developed At School?

Critical thinking is developed in nearly everything we do. However, much of this important skill is encouraged to be practiced at school, and rightfully so! Critical thinking goes beyond just thinking clearly — it’s also about thinking for yourself.

When a teacher asks a question in class, students are given the chance to answer for themselves and think critically about what they learned and what they believe to be accurate. When students work in groups and are forced to engage in discussion, this is also a great chance to expand their thinking and use their critical thinking skills.

How Does Critical Thinking Apply To Your Career?

Once you’ve finished school and entered the workforce, your critical thinking journey only expands and grows from here!

Impress Your Employer

Employers value employees who are critical thinkers, ask questions, offer creative ideas, and are always ready to offer innovation against the competition. No matter what your position or role in a company may be, critical thinking will always give you the power to stand out and make a difference.

Careers That Require Critical Thinking

Some of many examples of careers that require critical thinking include:

- Human resources specialist

- Marketing associate

- Business analyst

Truth be told however, it’s probably harder to come up with a professional field that doesn’t require any critical thinking!

Photo by Oladimeji Ajegbile from Pexels

What is someone with critical thinking skills capable of doing.

Someone with critical thinking skills is able to think rationally and clearly about what they should or not believe. They are capable of engaging in their own thoughts, and doing some reflection in order to come to a well-informed conclusion.

A critical thinker understands the connections between ideas, and is able to construct arguments based on facts, as well as find mistakes in reasoning.

The Process Of Critical Thinking

The process of critical thinking is highly systematic.

What Are Your Goals?

Critical thinking starts by defining your goals, and knowing what you are ultimately trying to achieve.

Once you know what you are trying to conclude, you can foresee your solution to the problem and play it out in your head from all perspectives.

What Does The Future Of Critical Thinking Hold?

The future of critical thinking is the equivalent of the future of jobs. In 2020, critical thinking was ranked as the 2nd top skill (following complex problem solving) by the World Economic Forum .

We are dealing with constant unprecedented changes, and what success is today, might not be considered success tomorrow — making critical thinking a key skill for the future workforce.

Why Is Critical Thinking So Important?

Why is critical thinking important? Critical thinking is more than just important! It’s one of the most crucial cognitive skills one can develop.

By practicing well-thought-out thinking, both your thoughts and decisions can make a positive change in your life, on both a professional and personal level. You can hugely improve your life by working on your critical thinking skills as often as you can.

Related Articles

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 8 min read

Critical Thinking

Developing the right mindset and skills.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

We make hundreds of decisions every day and, whether we realize it or not, we're all critical thinkers.

We use critical thinking each time we weigh up our options, prioritize our responsibilities, or think about the likely effects of our actions. It's a crucial skill that helps us to cut out misinformation and make wise decisions. The trouble is, we're not always very good at it!

In this article, we'll explore the key skills that you need to develop your critical thinking skills, and how to adopt a critical thinking mindset, so that you can make well-informed decisions.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is the discipline of rigorously and skillfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions, and beliefs. You'll need to actively question every step of your thinking process to do it well.

Collecting, analyzing and evaluating information is an important skill in life, and a highly valued asset in the workplace. People who score highly in critical thinking assessments are also rated by their managers as having good problem-solving skills, creativity, strong decision-making skills, and good overall performance. [1]

Key Critical Thinking Skills

Critical thinkers possess a set of key characteristics which help them to question information and their own thinking. Focus on the following areas to develop your critical thinking skills:

Being willing and able to explore alternative approaches and experimental ideas is crucial. Can you think through "what if" scenarios, create plausible options, and test out your theories? If not, you'll tend to write off ideas and options too soon, so you may miss the best answer to your situation.

To nurture your curiosity, stay up to date with facts and trends. You'll overlook important information if you allow yourself to become "blinkered," so always be open to new information.

But don't stop there! Look for opposing views or evidence to challenge your information, and seek clarification when things are unclear. This will help you to reassess your beliefs and make a well-informed decision later. Read our article, Opening Closed Minds , for more ways to stay receptive.

Logical Thinking

You must be skilled at reasoning and extending logic to come up with plausible options or outcomes.

It's also important to emphasize logic over emotion. Emotion can be motivating but it can also lead you to take hasty and unwise action, so control your emotions and be cautious in your judgments. Know when a conclusion is "fact" and when it is not. "Could-be-true" conclusions are based on assumptions and must be tested further. Read our article, Logical Fallacies , for help with this.

Use creative problem solving to balance cold logic. By thinking outside of the box you can identify new possible outcomes by using pieces of information that you already have.

Self-Awareness

Many of the decisions we make in life are subtly informed by our values and beliefs. These influences are called cognitive biases and it can be difficult to identify them in ourselves because they're often subconscious.

Practicing self-awareness will allow you to reflect on the beliefs you have and the choices you make. You'll then be better equipped to challenge your own thinking and make improved, unbiased decisions.

One particularly useful tool for critical thinking is the Ladder of Inference . It allows you to test and validate your thinking process, rather than jumping to poorly supported conclusions.

Developing a Critical Thinking Mindset

Combine the above skills with the right mindset so that you can make better decisions and adopt more effective courses of action. You can develop your critical thinking mindset by following this process:

Gather Information

First, collect data, opinions and facts on the issue that you need to solve. Draw on what you already know, and turn to new sources of information to help inform your understanding. Consider what gaps there are in your knowledge and seek to fill them. And look for information that challenges your assumptions and beliefs.

Be sure to verify the authority and authenticity of your sources. Not everything you read is true! Use this checklist to ensure that your information is valid:

- Are your information sources trustworthy ? (For example, well-respected authors, trusted colleagues or peers, recognized industry publications, websites, blogs, etc.)

- Is the information you have gathered up to date ?

- Has the information received any direct criticism ?

- Does the information have any errors or inaccuracies ?

- Is there any evidence to support or corroborate the information you have gathered?

- Is the information you have gathered subjective or biased in any way? (For example, is it based on opinion, rather than fact? Is any of the information you have gathered designed to promote a particular service or organization?)

If any information appears to be irrelevant or invalid, don't include it in your decision making. But don't omit information just because you disagree with it, or your final decision will be flawed and bias.

Now observe the information you have gathered, and interpret it. What are the key findings and main takeaways? What does the evidence point to? Start to build one or two possible arguments based on what you have found.

You'll need to look for the details within the mass of information, so use your powers of observation to identify any patterns or similarities. You can then analyze and extend these trends to make sensible predictions about the future.

To help you to sift through the multiple ideas and theories, it can be useful to group and order items according to their characteristics. From here, you can compare and contrast the different items. And once you've determined how similar or different things are from one another, Paired Comparison Analysis can help you to analyze them.

The final step involves challenging the information and rationalizing its arguments.

Apply the laws of reason (induction, deduction, analogy) to judge an argument and determine its merits. To do this, it's essential that you can determine the significance and validity of an argument to put it in the correct perspective. Take a look at our article, Rational Thinking , for more information about how to do this.

Once you have considered all of the arguments and options rationally, you can finally make an informed decision.

Afterward, take time to reflect on what you have learned and what you found challenging. Step back from the detail of your decision or problem, and look at the bigger picture. Record what you've learned from your observations and experience.

Critical thinking involves rigorously and skilfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions and beliefs. It's a useful skill in the workplace and in life.

You'll need to be curious and creative to explore alternative possibilities, but rational to apply logic, and self-aware to identify when your beliefs could affect your decisions or actions.

You can demonstrate a high level of critical thinking by validating your information, analyzing its meaning, and finally evaluating the argument.

Critical Thinking Infographic

See Critical Thinking represented in our infographic: An Elementary Guide to Critical Thinking .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

How to Guides

Planning Your Continuing Professional Development

Assess and Address Your CPD Needs

Book Insights

Do More Great Work: Stop the Busywork. Start the Work That Matters.

Michael Bungay Stanier

Add comment

Comments (1)

priyanka ghogare

Get 20% off your first year of Mind Tools

Our on-demand e-learning resources let you learn at your own pace, fitting seamlessly into your busy workday. Join today and save with our limited time offer!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

Pain Points Podcast - Balancing Work And Kids

Pain Points Podcast - Improving Culture

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Pain points podcast - what is ai.

Exploring Artificial Intelligence

Pain Points Podcast - How Do I Get Organized?

It's Time to Get Yourself Sorted!

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.1: Thinking Critically About Sources

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 168284

- Ohio State University Libraries

This section teaches you how to identify relevant and credible sources that have most likely turned up when searching the Web and on your results pages of the library catalog and specialized databases. Remember you always want to look for relevant, credible sources that will meet the information needs of your research project.

In order to evaluate a source, you have to read and review the information keeping in mind two very important questions:

- Is this source relevant to my research question?

- Is this a credible source– a source my audience and I should be able to believe

Note: As you read an academic paper you will need to determine relevance before credibility because no matter how credible a source is if it’s not relevant to your research question it’s useless to you for this project. Reading research-centric papers can be challenging. Check out the tips in the video below.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/ctar/?p=165#oembed-1

UBC iSchool. (2013). How to read an academic paper . https://youtu.be/SKxm2HF_-k0

Happily, you’ll also get faster the more you do it.

Making Inferences: Good Enough for Your Purpose?

Sources should always be evaluated relative to your purpose-why you’re looking for information. But because there often aren’t clear-cut answers when you evaluate sources, most of the time it is inferences, educated guesses from available clues, that you have to make about whether to use information from particular sources.

Your information needs will dictate:

- What kind of information will help?

- How serious you consider the consequences of making a mistake by using information that turns out to be inaccurate. When the consequences aren’t very serious, it’s easier to decide if a source and its information are good enough for your purpose. Of course, there’s a lot to be said for always having accurate information, regardless.

- How hard you’re willing to work to get the credible, timely information that suits your purpose. (What you’re learning here will make it easier.)

Thus, your standards for relevance and credibility may vary, depending on whether you need, say:

- Information about a personal health problem.

- An image you can use on a poster.

- Evidence to win a bet with a rival in the dorm.

- Dates and times a movie is showing locally.

- A game to have fun with.

- Evidence for your argument in a term paper.

For your research assignments or a health problem, the consequences may be great if you use information that is not relevant or not credible.

Evaluating Sources

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://minnstate.pressbooks.pub/ctar/?p=165#h5p-33

There are many approaches to evaluating your web and library resources. One that is quite useful is the SIFT process.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Taking critical thinking, creativity and grit online

Miguel nussbaum.

1 School of Engineering, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Camila Barahona

Fernanda rodriguez, victoria guentulle, felipe lopez, enrique vazquez-uscanga, veronica cabezas.

2 School of Education, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Technology has the potential to facilitate the development of higher-order thinking skills in learning. There has been a rush towards online learning by education systems during COVID-19; this can therefore be seen as an opportunity to develop students’ higher-order thinking skills. In this short report we show how critical thinking and creativity can be developed in an online context, as well as highlighting the importance of grit. We also suggest the importance of heuristic evaluation in the design of online systems to support twenty-first century learning.

Introduction

This paper is in response to the article “Designing for 21st century learning online: a heuristic method to enable educator learning support roles” (Nacu et al. 2018 ). In this paper, the authors outline a framework for heuristic evaluation when designing online experiences to support twenty-first century learning.

Twenty-first century skills can be key to success in a modern knowledge society. Among these skills, critical thinking is important not only at work, where problem solving is essential, but also in any social setting where adequate decision making is required (Dwyer and Walsh 2020 ). Additionally, creativity helps ensure that the outcomes of critical thinking can be both culturally ingenious as well as treasured (Yeh et al. 2019b ). This is achieved by embracing cognitive abilities in order to create new combinations of ideas (Davis 1969 ).

Technology has been shown to facilitate the development of higher-order thinking skills in learning (Engerman et al. 2018 ). However, in general, schools have failed to take advantage of this by incorporating adequate use of technology into their practices (Olszewski and Crompton 2020 ). Therefore, the rush towards online learning by education systems during COVID-19 can also be seen as an opportunity to develop students’ higher-order thinking skills. One potential drawback with online learning is the distance it creates between peers, thus hindering student engagement and the development of higher-order thinking skills (Dwyer and Walsh 2020 ). We show how this barrier can be overcome when developing critical thinking and creativity in an online context.

Critical thinking

Critical thinking includes the ability to identify the main elements and assumptions of an argument and the relationships between them, as well as drawing conclusions based on the information that is available, evaluating evidence, and self-correcting, among others. It is seen as a self-regulated process that comes from developing skills such as interpretation, analysis, evaluation and explanation; going beyond technical skills. It can therefore be considered a metacognitive process (Saxton et al. 2012 ; Facione 1990 ).

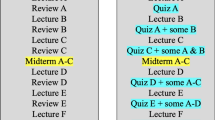

By taking learning online, both self-study and teacher-led sessions can be enhanced through a problem-based learning strategy. In the first stage, students build on a question or topic posed by the teacher, e.g. a mathematical problem or an essay writing assignment. In the second stage, students peer-review their classmates’ responses or essays using a rubric provided by the teacher. Students break down their classmates’ responses and see how they relate to the objective of the activity. They then compare this analysis with the rubric in order to provide feedback. In a third stage, the students develop a new response based on their initial response, the experience of giving feedback, and the feedback they received. This process develops self-evaluation as the students compare their own response with their classmates’ and discover any gaps in their knowledge. It can also develop metacognition as they integrate various sources of knowledge (initial response, feedback received and the experience of giving feedback) when developing a new response. In the final stage, the teacher discusses the different responses with the class. The teacher then compares the students’ work with the expected response and provides a general summary, transferring the responses to different domains.

While Stages 1 through 3 are asynchronous and computer-aided, stage 4 can be synchronous and supported by the use of a web-based video conferencing tool. Active student participation and teacher mediation are both key since interactive and instant feedback has been shown to improve critical thinking (Chang et al. 2020 ).

In addition to the problem-based strategy presented here, other active learning strategies can also be used to develop critical thinking, e.g. structured questioning, role playing, and cooperative learning (Cruz and Dominguez 2020 ). How these might be implemented online is still open to discussion, though heuristic evaluations may be a good alternative given the possibilities presented by online learning as a resource provider, learning broker and learning promoter (Nacu et al. 2018 ).

Creativity is an essential element of the problem-solving process. Creative people often find ways of addressing a problem that others cannot see, while also having the ability to overcome barriers where others may otherwise give up (Kaufman 2016 ). There are different techniques for developing creativity. In-depth learning is facilitated when students represent concepts based on their own personal perceptions (Liu et al. 2018 ). In this sense, analogy can be a powerful tool for boosting creativity. Analogical transfer includes the idea of making analogies by analyzing objects, ideas or concepts across domains, i.e. information is transferred from the known (the original domain) to the unknown (the new domain) by searching for similarities (Shen and Lai 2014 ).

We propose an analogical transfer strategy. In the first stage, the teacher identifies a concept with examples from different domains. This might include showing a video that not only introduces the concept but also provides a context that is both familiar and relatable for the students. In the second stage, students reflect on situations from their own lives where they can apply the concept that is being studied. Here, the use of open-ended questions allows the students’ creativity to be explored in greater depth, while adapting to their different backgrounds and levels of prior knowledge. In the third stage, which is mediated by the teacher, the students discuss their responses from stage 2. The teacher should focus on original responses from different domains, or responses where it is not clear whether the solution is correct.

Stages 1 and 2 can be conducted asynchronously and scaffolded using technology through the inclusion of multimedia and student guides. However, stage 3 should be synchronous and supported by the use of a web-based video conferencing tool. In this way, technology facilitates the development of creativity by facilitating the discovery process, the collection of ideas, and the integration of knowledge (Yang et al. 2018 ). Mediation in stage 3 is therefore key (Giacumo and Savenye 2020 ). Effective teacher-student dialogue can improve the teacher-student relationship and enhance the creative process. Heuristic evaluation can therefore help us understand this relationship by looking at these interactions on the online platform (Nacu et al. 2018 ).

As with any learning process, critical thinking and creativity require students to be both present and focused, which in turn requires grit (Yeh et al. 2019a ). In other words, the way in which students approach their schooling is just as important as what and how we teach them (Tissenbaum 2020 ). Grit should therefore not only be considered an essential element of academic achievement but also as a mental process that activates and/or directs people’s behavior and actions (Datu et al. 2018 , Lan and Moscardino 2019 ). This is particularly relevant in a COVID-19 context, where the pandemic is affecting the wellbeing and mental health of many students, families & communities (OECD 2020 ).

In order to achieve effective student engagement, the objective must be attainable, interesting and accessible (i.e. in their zone of proximal development). The means used to complete the task must be attractive and feel more like a reward than an assignment. Finally, the teacher should work on the students’ persistence, not just in order to complete the task but as an essential quality for everyday life (Barnes 2019 ).

Teacher grit may also be key. As Haderer ( 2020 ) suggests “Why do some teachers stay when others run from the challenges?” In this sense, reflection has been shown to be relevant for teacher efficacy and grit (Haderer 2020 ). Heuristic evaluation methods may therefore allow the educator to understand the learning system as a whole (Nacu et al. 2018 ).

Ending remarks

As indicated in (Nacu et al. 2018 ) we are “faced with the need to create youth-centered spaces that also provide adult facilitation of learning”. Heuristic evaluation can therefore help connect online platforms with students, teachers and twenty-first century skills needs.

Acknowledgements

The research results informed in this report were supported by ANID/FONDECYT 1180024.

Biographies

is full professor for Computer Science at the School of Engineering of the Universidad Católica de Chile. He was member of the board of the Chilean Agency for the Quality of Education in Chile, and is Co-editor of Computers & Education.

is a teacher who is doing a PhD at the School of Engineering of the Universidad Católica de Chile.

is an engineer who is doing a PhD at the School of Engineering of the Universidad Católica de Chile.

is an Assistant Professor at the School of Education, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, and associate researcher at Millennium Nucleus of Social Development. She is co-founder of Teach for all in Chile (Enseña Chile), and an NGO in Chile to foster high school students to choose the education career (Elige Educar).

Compliance with ethical standards

The different research projects underlying this report received approval from the University’s ethics committee. The participation was voluntary and the students signed an informed consent form.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Miguel Nussbaum, Email: lc.cup.gni@nm .

Camila Barahona, Email: lc.cu@oharabec .

Fernanda Rodriguez, Email: lc.cu@3irdorfm .

Victoria Guentulle, Email: lc.cu@utneugav .

Felipe Lopez, Email: lc.cu@1zepolif .

Enrique Vazquez-Uscanga, Email: lc.cu@zeuqzavae .

Veronica Cabezas, Email: [email protected] .

- Barnes A. Perseverance in mathematical reasoning: The role of children’s conative focus in the productive interplay between cognition and affect. Research in Mathematics Education. 2019; 21 (3):271–294. doi: 10.1080/14794802.2019.1590229. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chang CY, Kao CH, Hwang GJ, Lin FH. From experiencing to critical thinking: A contextual game-based learning approach to improving nursing students’ performance in electrocardiogram training. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2020; 68 (3):1225–1245. doi: 10.1007/s11423-019-09723-x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruz, G., & Dominguez, C. (2020, April). Engaging students, teachers, and professionals with 21st century skills: the ‘Critical Thinking Day’ proposal as an integrated model for engineering educational activities. In 2020 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) (pp. 1969–1974). IEEE.

- Datu JAD, Yuen M, Chen G. The triarchic model of grit is linked to academic success and well-being among Filipino high school students. School Psychology Quarterly. 2018; 33 (3):428–438. doi: 10.1037/spq0000234. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis GA. Training creativity in adolescence: A discussion of strategy. The Journal of Creative Behavior. 1969; 3 (2):95–104. doi: 10.1002/j.2162-6057.1969.tb00050.x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwyer CP, Walsh A. An exploratory quantitative case study of critical thinking development through adult distance learning. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2020; 68 :17–35. doi: 10.1007/s11423-019-09659-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Engerman JA, MacAllan M, Carr-Chellman AA. Games for boys: A qualitative study of experiences with commercial off the shelf gaming. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2018; 66 :313–339. doi: 10.1007/s11423-017-9548-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Facione PA. Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction executive summary “the Delphi report” The California Academic Press. 1990; 423 (c):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2009.07.002. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Giacumo, L. A., & Savenye, W. (2020). Asynchronous discussion forum design to support cognition: Effects of rubrics and instructor prompts on learner’s critical thinking, achievement, and satisfaction. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68 (1), 37–66.

- Haderer, A. M. (2020). Exploring the relationship between teacher efficacy and grit. Doctoral dissertation, Shenandoah University.

- Kaufman JC. Creativity 101. 2. New York: Springer; 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lan X, Moscardino U. Direct and interactive effects of perceived teacher-student relationship and grit on student wellbeing among stay-behind early adolescents in urban China. Learning and Individual Differences. 2019; 69 :129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2018.12.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu K, Tai SD, Liu C. Enhancing language learning through creation: The effect of digital storytelling on student learning motivation and performance in a school English course. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2018; 66 :913–935. doi: 10.1007/s11423-018-9592-z. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nacu D, Martin CK, Pinkard N. Designing for 21st century learning online: A heuristic method to enable educator learning support roles. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2018; 66 (4):1029–1049. doi: 10.1007/s11423-018-9603-0. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Olszewski B, Crompton H. Educational technology conditions to support the development of digital age skills. Computers & Education. 2020; 150 :103849. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103849. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- OECD. (2020). A framework to guide an education response to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=126_126988-t63lxosohs&title=A-framework-to-guide-an-education-response-to-the-Covid-19-Pandemic-of-2020

- Saxton E, Belanger S, Becker W. The Critical Thinking Analytic Rubric (CTAR): Investigating intra-rater and inter-rater reliability of a scoring mechanism for critical thinking performance assessments. Assessing Writing. 2012; 17 (4):251–270. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2012.07.002. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shen, T., & Lai, J. (2014). Formation of creative thinking by analogical performance in creative works. The European Journal of Social & Behavioural Sciences , 1159–1167. 10.15405/ejsbs.95.

- Tissenbaum M. I see what you did there! Divergent collaboration and learner transitions from unproductive to productive states in open-ended inquiry. Computers & Education. 2020; 145 :103739. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103739. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yang X, Lin L, Cheng PY, Yang X, Ren Y, Huang YM. Examining creativity through a virtual reality support system. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2018; 66 (5):1231–1254. doi: 10.1007/s11423-018-9604-z. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yeh YC, Chang HL, Chen SY. Mindful learning: A mediator of mastery experience during digital creativity game-based learning among elementary school students. Computers & Education. 2019; 132 :63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yeh YC, Rega EM, Chen SY. Enhancing creativity through aesthetics-integrated computer-based training: The effectiveness of a FACE approach and exploration of moderators. Computers & Education. 2019; 139 :48–64. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.05.007. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Critical Thinking and Evaluating Information

In this chapter, you will read a chapter on Critical Thinking and Evaluating Information from a module on Effective Learning Strategies, Student Success by Jazzabel Maya at Austin Community College, Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike

Use warming up, working out, and cooling down strategies to read the chapter. You will participate in a discussion and write a journal after you finish reading.

Remember to write down the strategies you’re using to warm up, work out, and cool down.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define critical thinking

- Describe the role that logic plays in critical thinking

- Describe how both critical and creative thinking skills can be used to problem-solve

- Describe how critical thinking skills can be used to evaluate information

- Apply the CRAAP test to evaluate sources of information

- Identify strategies for developing yourself as a critical thinker

Critical Thinking and Evaluating Information

Critical Thinking

As a college student, you are tasked with engaging and expanding your thinking skills. One of the most important of these skills is critical thinking because it relates to nearly all tasks, situations, topics, careers, environments, challenges, and opportunities. It is a “domain-general” thinking skill, not one that is specific to a particular subject area.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is clear, reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do. It means asking probing questions like “How do we know?” or “Is this true in every case or just in this instance?” It involves being skeptical and challenging assumptions rather than simply memorizing facts or blindly accepting what you hear or read.

Imagine, for example, that you’re reading a history textbook. You wonder who wrote it and why, because you detect certain biases in the writing. You find that the author has a limited scope of research focused only on a particular group within a population. In this case, your critical thinking reveals that there are “other sides to the story.”

Who are critical thinkers, and what characteristics do they have in common? Critical thinkers are usually curious and reflective people. They like to explore and probe new areas and seek knowledge, clarification, and new solutions. They ask pertinent questions, evaluate statements and arguments, and they distinguish between facts and opinion. They are also willing to examine their own beliefs, possessing a manner of humility that allows them to admit lack of knowledge or understanding when needed. They are open to changing their mind. Perhaps most of all, they actively enjoy learning, and seeking new knowledge is a lifelong pursuit. This may well be you!

No matter where you are on the road to being a critical thinker, you can always more fully develop and finely tune your skills. Doing so will help you develop more balanced arguments, express yourself clearly, read critically, and glean important information efficiently. Critical thinking skills will help you in any profession or any circumstance of life, from science to art to business to teaching. With critical thinking, you become a clearer thinker and problem solver.

Critical Thinking and Logic

Critical thinking is fundamentally a process of questioning information and data. You may question the information you read in a textbook, or you may question what a politician or a professor or a classmate says. You can also question a commonly-held belief or a new idea. With critical thinking, anything and everything is subject to question and examination for the purpose of logically constructing reasoned perspectives.

What Is Logic?

The word logic comes from the Ancient Greek logike , referring to the science or art of reasoning. Using logic, a person evaluates arguments and reasoning and strives to distinguish between good and bad reasoning, or between truth and falsehood. Using logic, you can evaluate the ideas and claims of others, make good decisions, and form sound beliefs about the world. [1]

Questions of Logic in Critical Thinking

Let’s use a simple example of applying logic to a critical-thinking situation. In this hypothetical scenario, a man has a Ph.D. in political science, and he works as a professor at a local college. His wife works at the college, too. They have three young children in the local school system, and their family is well known in the community. The man is now running for political office. Are his credentials and experience sufficient for entering public office? Will he be effective in the political office? Some voters might believe that his personal life and current job, on the surface, suggest he will do well in the position, and they will vote for him. In truth, the characteristics described don’t guarantee that the man will do a good job. The information is somewhat irrelevant. What else might you want to know? How about whether the man had already held a political office and done a good job? In this case, we want to think critically about how much information is adequate in order to make a decision based on logic instead of assumptions.

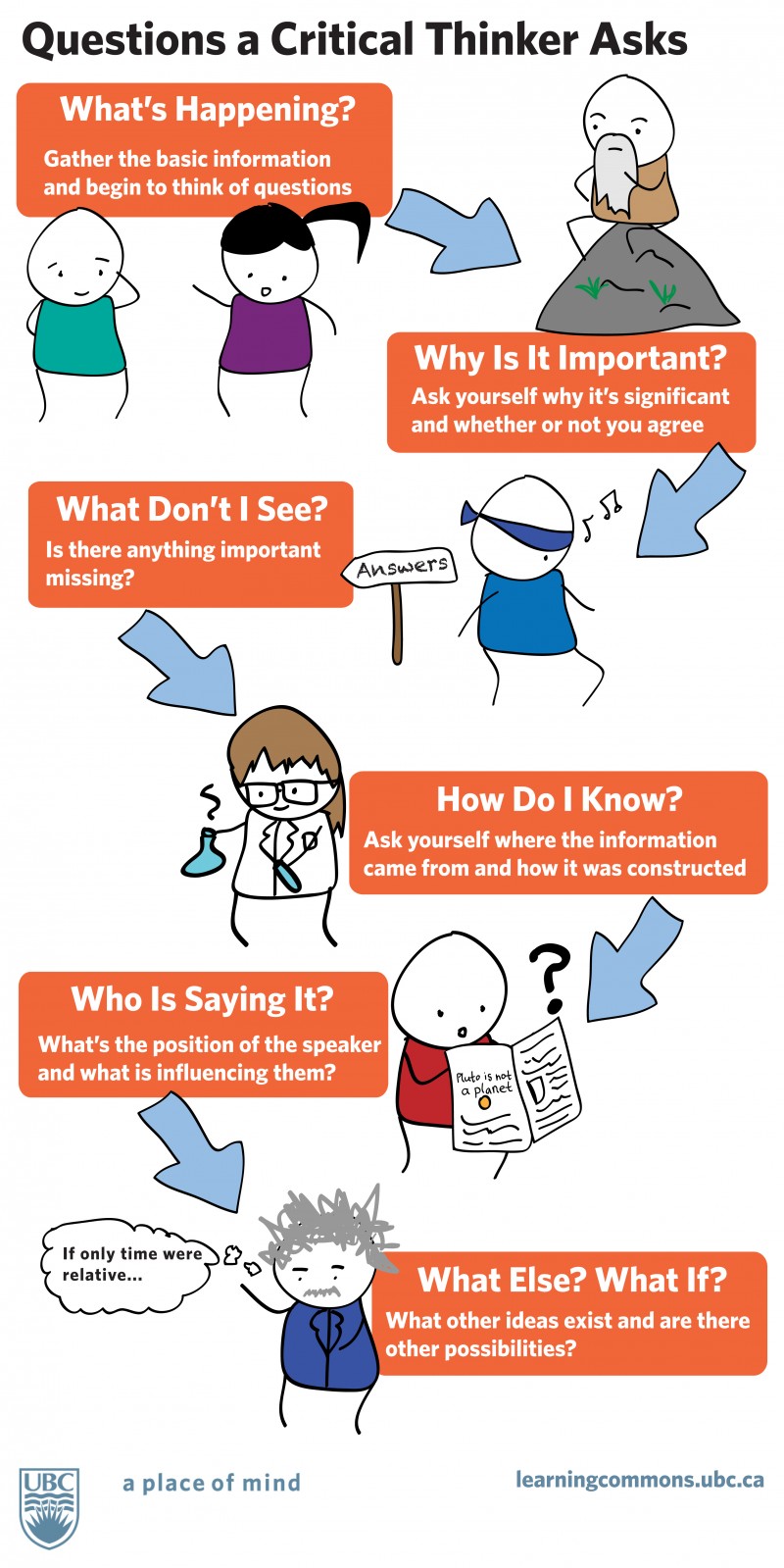

The following questions, presented in Figure 1, below, are ones you may apply to formulating a logical, reasoned perspective in the above scenario or any other situation:

- What’s happening? Gather the basic information and begin to think of questions.

- Why is it important? Ask yourself why it’s significant and whether or not you agree.

- What don’t I see? Is there anything important missing?

- How do I know? Ask yourself where the information came from and how it was constructed.

- Who is saying it? What’s the position of the speaker and what is influencing them?

- What else? What if? What other ideas exist and are there other possibilities?

Problem-Solving with Critical Thinking

For most people, a typical day is filled with critical thinking and problem-solving challenges. In fact, critical thinking and problem-solving go hand-in-hand. They both refer to using knowledge, facts, and data to solve problems effectively. But with problem-solving, you are specifically identifying, selecting, and defending your solution. Below are some examples of using critical thinking to problem-solve:

- Your roommate was upset and said some unkind words to you, which put a crimp in the relationship. You try to see through the angry behaviors to determine how you might best support the roommate and help bring the relationship back to a comfortable spot.

- Your campus club has been languishing due to lack of participation and funds. The new club president, though, is a marketing major and has identified some strategies to interest students in joining and supporting the club. Implementation is forthcoming.

- Your final art class project challenges you to conceptualize form in new ways. On the last day of class when students present their projects, you describe the techniques you used to fulfill the assignment. You explain why and how you selected that approach.

- Your math teacher sees that the class is not quite grasping a concept. She uses clever questioning to dispel anxiety and guide you to a new understanding of the concept.

- You have a job interview for a position that you feel you are only partially qualified for, although you really want the job and you are excited about the prospects. You analyze how you will explain your skills and experiences in a way to show that you are a good match for the prospective employer.

- You are doing well in college, and most of your college and living expenses are covered. But there are some gaps between what you want and what you feel you can afford. You analyze your income, savings, and budget to better calculate what you will need to stay in college and maintain your desired level of spending.

Problem-Solving Action Checklist

Problem-solving can be an efficient and rewarding process, especially if you are organized and mindful of critical steps and strategies. Remember to assume the attributes of a good critical thinker: if you are curious, reflective, knowledge-seeking, open to change, probing, organized, and ethical, your challenge or problem will be less of a hurdle, and you’ll be in a good position to find intelligent solutions. The steps outlined in this checklist will help you adhere to these qualities in your approach to any problem:

Critical and Creative Thinking

Critical and creative thinking (described in more detail in Chapter 6: Theories of Learning) complement each other when it comes to problem-solving. The following words, by Dr. Andrew Robert Baker, are excerpted from his “Thinking Critically and Creatively” essay. Dr. Baker illuminates some of the many ways that college students will be exposed to critical and creative thinking and how it can enrich their learning experiences.

THINKING CRITICALLY AND CREATIVELY Critical thinking skills are perhaps the most fundamental skills involved in making judgments and solving problems. You use them every day, and you can continue improving them. The ability to think critically about a matter—to analyze a question, situation, or problem down to its most basic parts—is what helps us evaluate the accuracy and truthfulness of statements, claims, and information we read and hear. It is the sharp knife that, when honed, separates fact from fiction, honesty from lies, and the accurate from the misleading. We all use this skill to one degree or another almost every day. For example, we use critical thinking every day as we consider the latest consumer products and why one particular product is the best among its peers. Is it a quality product because a celebrity endorses it? Because a lot of other people may have used it? Because it is made by one company versus another? Or perhaps because it is made in one country or another? These are questions representative of critical thinking. The academic setting demands more of us in terms of critical thinking than everyday life. It demands that we evaluate information and analyze myriad issues. It is the environment where our critical thinking skills can be the difference between success and failure. In this environment we must consider information in an analytical, critical manner. We must ask questions—What is the source of this information? Is this source an expert one and what makes it so? Are there multiple perspectives to consider on an issue? Do multiple sources agree or disagree on an issue? Does quality research substantiate information or opinion? Do I have any personal biases that may affect my consideration of this information? It is only through purposeful, frequent, intentional questioning such as this that we can sharpen our critical thinking skills and improve as students, learners and researchers. While critical thinking analyzes information and roots out the true nature and facets of problems, it is creative thinking that drives progress forward when it comes to solving these problems. Exceptional creative thinkers are people that invent new solutions to existing problems that do not rely on past or current solutions. They are the ones who invent solution C when everyone else is still arguing between A and B. Creative thinking skills involve using strategies to clear the mind so that our thoughts and ideas can transcend the current limitations of a problem and allow us to see beyond barriers that prevent new solutions from being found. Brainstorming is the simplest example of intentional creative thinking that most people have tried at least once. With the quick generation of many ideas at once, we can block-out our brain’s natural tendency to limit our solution-generating abilities so we can access and combine many possible solutions/thoughts and invent new ones. It is sort of like sprinting through a race’s finish line only to find there is new track on the other side and we can keep going, if we choose. As with critical thinking, higher education both demands creative thinking from us and is the perfect place to practice and develop the skill. Everything from word problems in a math class, to opinion or persuasive speeches and papers, call upon our creative thinking skills to generate new solutions and perspectives in response to our professor’s demands. Creative thinking skills ask questions such as—What if? Why not? What else is out there? Can I combine perspectives/solutions? What is something no one else has brought-up? What is being forgotten/ignored? What about ______? It is the opening of doors and options that follows problem-identification. Consider an assignment that required you to compare two different authors on the topic of education and select and defend one as better. Now add to this scenario that your professor clearly prefers one author over the other. While critical thinking can get you as far as identifying the similarities and differences between these authors and evaluating their merits, it is creative thinking that you must use if you wish to challenge your professor’s opinion and invent new perspectives on the authors that have not previously been considered. So, what can we do to develop our critical and creative thinking skills? Although many students may dislike it, group work is an excellent way to develop our thinking skills. Many times I have heard from students their disdain for working in groups based on scheduling, varied levels of commitment to the group or project, and personality conflicts too, of course. True—it’s not always easy, but that is why it is so effective. When we work collaboratively on a project or problem we bring many brains to bear on a subject. These different brains will naturally develop varied ways of solving or explaining problems and examining information. To the observant individual we see that this places us in a constant state of back and forth critical/creative thinking modes. For example, in group work we are simultaneously analyzing information and generating solutions on our own, while challenging other’s analyses/ideas and responding to challenges to our own analyses/ideas. This is part of why students tend to avoid group work—it challenges us as thinkers and forces us to analyze others while defending ourselves, which is not something we are used to or comfortable with as most of our educational experiences involve solo work. Your professors know this—that’s why we assign it—to help you grow as students, learners, and thinkers! —Dr. Andrew Robert Baker, Foundations of Academic Success: Words of Wisdom

Evaluating Information with Critical Thinking

Evaluating information can be one of the most complex tasks you will be faced with in college. But if you utilize the following four strategies, you will be well on your way to success:

- Read for understanding

- Examine arguments

- Clarify thinking

- Cultivate “habits of mind”

Read for Understanding

When you read, take notes or mark the text to track your thinking about what you are reading. As you make connections and ask questions in response to what you read, you monitor your comprehension and enhance your long-term understanding of the material. You will want to mark important arguments and key facts. Indicate where you agree and disagree or have further questions. You don’t necessarily need to read every word, but make sure you understand the concepts or the intentions behind what is written. See the chapter on Active Reading Strategies for additional tips.

Examine Arguments

When you examine arguments or claims that an author, speaker, or other source is making, your goal is to identify and examine the hard facts. You can use the spectrum of authority strategy for this purpose. The spectrum of authority strategy assists you in identifying the “hot” end of an argument—feelings, beliefs, cultural influences, and societal influences—and the “cold” end of an argument—scientific influences. The most compelling arguments balance elements from both ends of the spectrum. The following video explains this strategy in further detail:

Clarify Thinking

When you use critical thinking to evaluate information, you need to clarify your thinking to yourself and likely to others. Doing this well is mainly a process of asking and answering probing questions, such as the logic questions discussed earlier. Design your questions to fit your needs, but be sure to cover adequate ground. What is the purpose? What question are we trying to answer? What point of view is being expressed? What assumptions are we or others making? What are the facts and data we know, and how do we know them? What are the concepts we’re working with? What are the conclusions, and do they make sense? What are the implications?

Cultivate “Habits of Mind”