- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

1 A Brief History of Project Management

Peter W.G. Morris is Professor and Head of the School of Construction and Project Management at University College London (UCL). He is the author of over 110 papers and several books on the management of projects. A previous Chairman of the Association for Project Management, he was awarded the Project Management Institute's 2005 Research Achievement Award, IPMA's 2009 Research Award, and APM's 2008 Sir Monty Finniston Life-Time Achievement Award.

- Published: 02 May 2011

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Project Management is a social construct. Our understanding of what it entails has evolved over the years, and is continuing to do so. This article traces the history of this evolution. It does so from the perspective of the professional project management community. It argues that although there are several hundred thousand members of project management professional associations around the world, and many more who deploy tools, techniques, and concepts which they, and others, perceive to be “project management,” there are differing views of the scope of the subject, of its ontology and epistemologies. Maybe this is true of many subjects which are socially constructed, but in the real world of projects, where people are charged with spending significant resources, misapprehension can be serious.

Introduction

Project Management is a social construct. Our understanding of what it entails has evolved over the years, and is continuing to do so. This chapter traces the history of this evolution. It does so from the perspective of the professional project management community. It argues that although there are several hundred thousand members of project management professional associations around the world, and many more who deploy tools, techniques, and concepts which they, and others, perceive to be “project management,” there are differing views of the scope of the subject, of its ontology and epistemologies. Maybe this is true of many subjects which are socially constructed, but in the real world of projects, where people are charged with spending significant resources, misapprehension can be serious.

Later chapters in this book reflect aspects of this uncertainty and some indeed question whether project management is or should be a distinct domain or a profession—having a body of knowledge of its own—at all. Many certainly note the strains between its normative character as a professional discipline and the importance of understanding context when applying it. Nevertheless, despite this uncertainty the fact remains that many thousand people around the world see themselves as competent project professionals having shared “mental models” of what is meant by the discipline. But are these models fit-for-purpose? The chapter argues that in part at least some are, or were, too limited in scope to address the task of delivering projects successfully.

The account unavoidably draws on my personal engagement with, and reflection on, the field. (History is always seen through the eye of the historian.) It is an account of a “reflective practitioner.” Some commentators would doubtless tell the story differently, with different emphases. Hence, referring to the models again, a major theme running through the chapter is the danger of positioning project management with too narrow a focus—as an execution-only oriented discipline: “the application of knowledge, skills, tools and techniques…to meet project requirements” (PMI 2008: 8). (So, who sets the requirements? Isn't that part of the project?) Instead, the chapter argues the benefits of focusing on the management of the project as a whole, from its early stages of conception—to include the elicitation and definition of requirements—to its post-commissioning phases, emphasizing context, the front-end, stakeholders, the various measures of project success, technology and commercial issues, people, and the importance of value and of delivering benefit: what I have termed elsewhere “the management of projects” (Morris and Hough 1987 ; Morris 1994 ; Morris and Pinto 2004 )—as well of course as being master of the traditional core execution skills.

Early history

The word “project” means something thrown forth or out; an idea or conception ( Oxford English Dictionary ); “management” is “the art of arranging physical and human resources towards purposeful ends” (Wren 2005 : 12). “Project Management” means…? The term as such appears not to have been in much if any use before the early 1950s, though of course projects had been managed since the dawn of civilization: the ancient cities of Mesopotamia, the pyramids of Egypt, Stonehenge; history is full of examples of outstanding engineering feats, military campaigns, and other singular undertakings, all attesting to man's ability to accomplish complex, demanding projects. But, barring a few exceptions, it is not until the early 1950s that the language of contemporary project management begins to be invented.

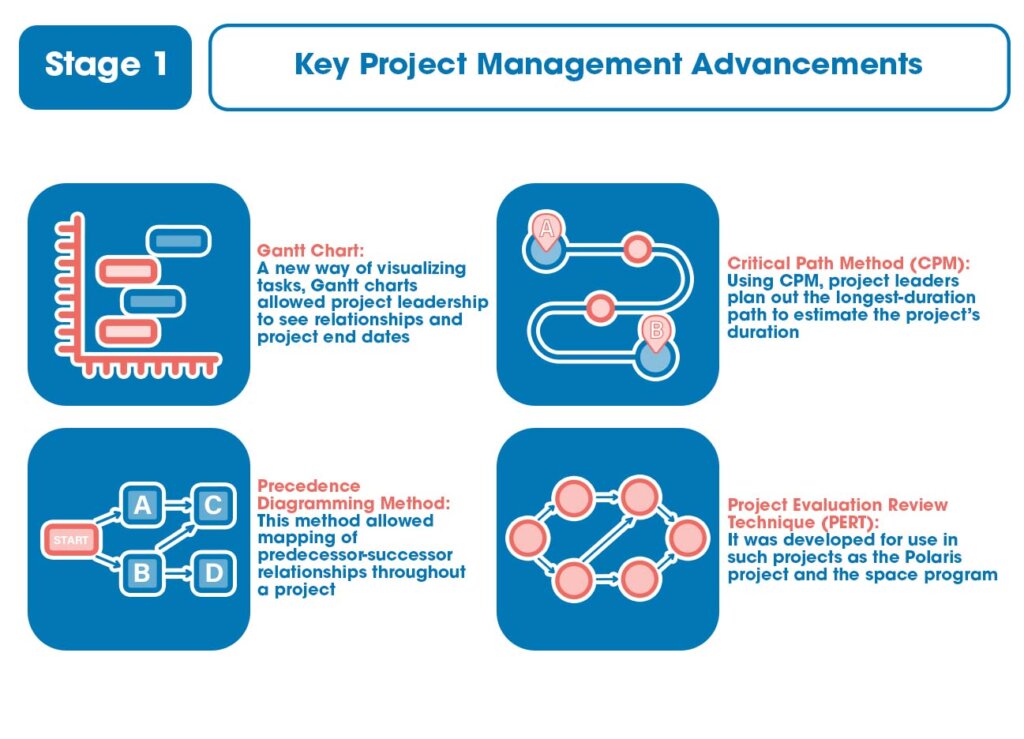

There are several important precursors to this emergence, however. Adamiecki published his harmonogram (effectively a vertical bar chart) in 1903 (Marsh 1975 ). (Following Priestley's idea of putting lines to a horizontal timescale published in 1765 in his Chart of Biography. ) Gantt's bar chart followed in 1917. Formal project coordinator roles appear in the US Army Air Corps in the 1920s (Morris 1994 ), project engineers and project officers (Johnson 2002 ), and project engineers in Exxon and other process engineering companies in the 1930s. And in 1936 Gulick, in a theoretical paper, proposed the idea of the matrix organization (Gulick 1937 ).

There is surprisingly little evidence of the contemporary language and tools of project management to be seen in the Second World War, despite the emergence of Operations Research (OR). The Manhattan Project—the US program to develop the Atom Bomb—is often quoted as one of the earliest examples of modern project management. This may be over-cooking the case: we see in the project—the program—none of the tools or language of today's world of project management.

The 1950s and 1960s: systems development

Project management as a term seems to first appear in 1953, arising in the US defense-aerospace sector (Johnson 2002 ). The emerging advent of thermonuclear-armed ICBMs (InterContinental Ballistic Missiles), and in particular the threat from Russian ICBMs, became an increasingly severe US preoccupation from the early 1950s prompting the US Air Force (and Navy and Army) to look very seriously at how the development of their missiles could be accelerated. Under procurement processes developed by Brigadier Bernard Schriever for the US Air Force (USAF) in 1951, the USAF Air Research and Development and Air Material Commands were required to work together in “special project offices” under a “project manager” who would have full responsibility for the project, and contractors were required to consider the entire “weapons system” on a project basis (Johnson 2002 : 29–31). The Martin (Marietta) company is credited with having created “the first recognizable project management organization” in 1953—in effect a matrix (Johnson 1997 ).

The management of major systems programs

In 1954 Schriever was appointed to head the Atlas ICBM development where he continued his push for integration and urgency, proposing a more holistic approach involving greater use of contractors as system integrators to create the system's specifications and to oversee its development (Hughes 1998 ; Johnson 2002 ). As with Manhattan, Schriever concentrated on building an excellent team. To shorten development times, Schriever also aggressively promoted the practice of concurrency—the parallel planning of all system elements with many normally serial activities being run concurrently (lampooned as “design-as-you-go!”). Unfortunately, concurrency amplified technical problems, as was discovered when missile testing began in late 1956. As a result, Schriever developed rigorous “systems engineering” testing, tracking, and configuration management techniques on the next missile program, Minuteman, which were soon to be applied on the Apollo moon program.

Meanwhile the US Navy was developing its own project and program management practices. Following Teller's 1956 insight that the rate of missile technology development would enable ICBMs to fit in submarines by the early to mid 1960s, when the submarines would be ready (Sapolsky 1972 : 30), the Navy began work on Polaris. Admiral Raborn was appointed as head of the Polaris SPO (Special Projects Office) in 1955. Like Schriever, Raborn emphasized quality of people and team morale. Polaris's SPO exerted more hands-on management than the Air Force, one result of which was the development in 1957 of PERT as a planning and monitoring tool. PERT, the Planning and Evaluation Review Technique, never quite fulfilled its promise but, like Critical Path Method (CPM), invented by DuPont in 1957–9, became iconic as a symbol of the new discipline of project management. Raborn, cleverly and presciently, used PERT as a tool in stakeholder management (though the term was not used), publicizing it to Congress and the Press as the first management tool of the nuclear and computer age.

In 1960 the Air Force implemented Schriever's methods throughout its R&D organizations, documenting them as the “375-series” regulations: a phased life-cycle approach; planning for the entire system up front; project offices with the authority to manage the full development, assisted by systems support contractors (Morrison 1967 ). Essentially project and program management had become the fundamental means to organize complex systems development, and system engineering the engineering mechanism to coordinate them (Johnson 1997 ).

These principles were then given added weight, and thrust, first by the arrival of Robert McNamara as US Secretary of Defense in 1960 and second by NASA (specifically Apollo); from there they spread throughout the USA, and then NATO's, aerospace and electronics industries.

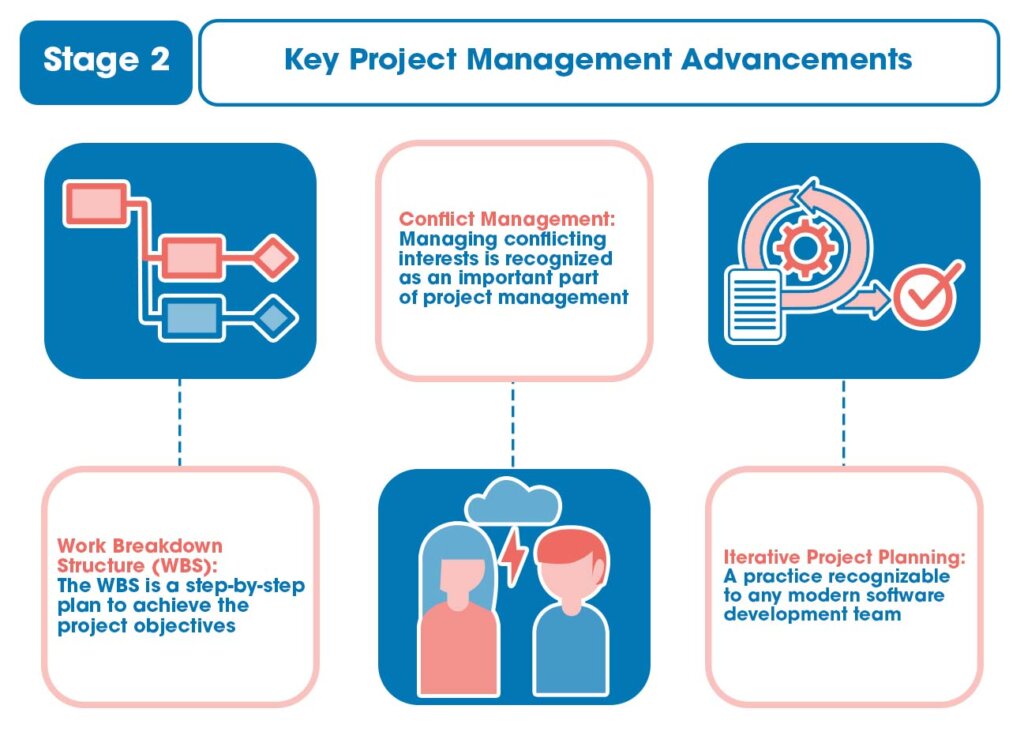

McNamara was an OR enthusiast and a great centralizer. The Program Planning and Budgeting System (PPBS) was his main centralizing tool but he introduced in addition several OR-based practices such as Life-Cycle Costing, Integrated Logistics Support, Quality Assurance, Value Engineering, Configuration Management, and the Work Breakdown Structure, the latter being promoted in 1962 in a joint Department of Defense (DoD)/NASA guide: “PERT/Cost Systems Design.” This “guide” generated a proliferation of systems and much attendant complaining from industry, so instead Earned Value (as an element of DoD's C/SCSC—Cost/Schedule Control Systems Criteria—requirements) was introduced in 1964 as a performance management approach (Morris 1994 ).

Meanwhile Sam Philips, recently a USAF brigadier managing Minuteman, was heading NASA's Apollo program “of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth,” in President Kennedy's historic words of 1961. Apollo brought systems (project) management squarely into the public gaze. Philips imposed configuration management as his core control discipline with rigorous design reviews and work package management—“the devil is in the interface” (Johnson 2002 ). Matrix structures were deployed to harness specialist resources while task forces addressed specific problems. Quality, reliability, and (“all-up”) testing became hugely important as phased testing became too time consuming and costly.

Back on earth, Precedence scheduling had been invented in 1962, by IBM; and in the late 1960s resource allocation scheduling techniques were developed (Morris 1994 ).

Organization and people management

Project management came to be seen, for many years, as epitomized by tools such as PERT and CPM, Work Breakdown Structures, and Earned Value. In reality, however, a more fundamental feature is integration around a clear objective: whether as “single point of integrative responsibility,” in Archibald's pithy phrase (Archibald 1976 ), project “task forces,” or the matrix. This integration should ideally, as per Schriever, be across the whole project life cycle. (Regarding which, it is salutary to note that in the “execution” delivery view of project (see below pp. 20–2), the project manager is generally not the single point of integrative responsibility for the overall project but only for the execution phase.) People skills are also important. As we have seen, Schriever, Raborn, and Philips all emphasized high-level leadership, teamwork, and task performance. Apollo sponsored several studies on team and individual skills (Baker and Wilemon 1974 ; Wilemon and Thamhain 1977 ).

In 1959 the Harvard Business Review published an article on the new integrator role, “the project manager” (Gaddis 1959 ), and by the late 1960s and early 1970s these ideas on organizational integration had begun to attract serious academic attention, for example Lawrence and Lorsch's 1967 study on integration and differentiation, Galbraith's on forms of integration ( 1973 ), and Davis and Lawrence's work on the matrix ( 1977 ). The intellectual environment meanwhile became increasingly attuned to “the systems approach” (Cleland and King 1968 ; Johnson, Kast, and Rosenzweig 1973 ).

As NASA reached (metaphorically and literally) its apogee, project management began now to be seen as a management approach which had potentially very widespread application and benefit. Society could address its major social challenges, NASA claimed, using the same systems approaches that had got man to the moon—employing “adaptive, problem-solving, temporary systems of diverse specialists, linked together by coordinating executives” (Webb 1969 : 23). But it was not going to be so easy, either in NASA, DoD, or the wider world. For, as Sayles and Chandler, two leading academics, pointed out in 1971, “NASA was a closed loop—it set its own schedule, designed its own hardware… As one moves into the (more political) socio-technical area, this luxury disappears” (Sayles and Chandler 1971 : 160).

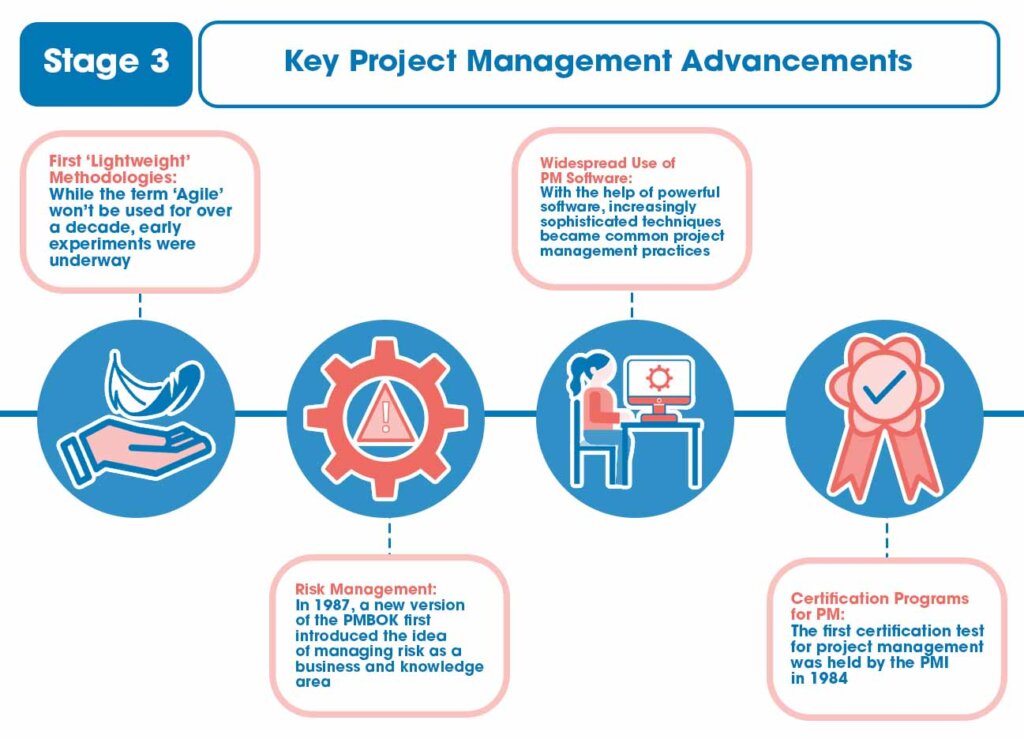

The birth of the professional project management associations

Simultaneously, with the spread of the matrix and DoD project management techniques, many executives suddenly found themselves pitched into managing projects for the first time. Conferences and seminars on how to do so proliferated. The US Project Management Institute (PMI) was founded in 1969; the International Management Systems Association (also called INTERNET, now the International Project Management Association—IPMA) in 1972, with various European project management associations being formed contemporaneously. Crucially, however, the perspective was essentially a middle management, project execution one centered around the challenges of accomplishing the project goals that had been given, and on the tools and techniques for doing this; it was rarely the successful accomplishment of the project per se , which is after all what really matters. Worse, the performance of projects, already too often bad, was now beginning to deteriorate sharply.

The 1970s to the 1990s: wider application, new strands, and ontological divergence

In some cases, projects were failing precisely because they lacked project management—Concorde for example: an immense concatenation of technological challenges with no effective project management (Morris and Hough 1987 ). But in others, although “best practice” was being earnestly applied, the paradigm was wrong. Concorde's American rival for example was managed by two ex-USAF senior officers according to DoD principles but with no effective program for addressing stakeholder opposition (remember Raborn!)—which in fact led in 1970 to Congress refusing to fund the program and its cancellation (Horwitch 1982 ). The whole nuclear power industry throughout the 1970s and 1980s exhibited similar problems of massive stakeholder (environmentalist) opposition coupled with the challenges of introducing major technological developments during construction (concurrency again, with the concomitant challenge of “regulatory ratcheting” as authorities sought to codify and apply changing technical requirements on power plants already well under construction.) Exceptionally high cost inflation worldwide blew project estimates. The oil and gas industry faced additional costs as it moved into difficult new environments such as Alaska and the North Sea. Even the US weapons programs were not performing well, with problems of technology selection and proving, project definition, supplier selection, and above all concurrency, which DoD at times proscribed as costs grew and at others, chafing at the lack of speed, reluctantly allowed (Morris 1994 ).

Success and failure studies

The causes of project success and failure now began to receive serious attention. DoD had commissioned a number of studies on project performance concluding that technological uncertainty, scope changes, concurrency, and contractor engagement were major issues (Marshall and Meckling 1959 ; Peck and Scherer 1962 ; Summers 1965 ; Perry et al. 1969 ; Large 1971 ). Developing world aid projects were analyzed (Hirschman 1967 ), the World Bank in a major review of project lending between 1945 and 1985 concluding that more attention was needed to technological adequacy, project design, and institution-building (Baum and Tolbert 1985 ). The US General Accounting Office and the UK National Audit Office conducted several highly critical reviews of publicly funded projects. Various academic and other research bodies reported on energy and power plants, systems projects, R&D projects, autos, and airports (Morris 1994 ).

In fact, Morris and Hough in their 1987 study of project success and failure, The Anatomy of Major Projects , listed 34 studies covering 1,536 projects and programs of the 1960s and 1970s (and added a further 8 of their own). Typical sources of difficulty were: unclear success criteria, changing sponsor strategy, poor project definition, technology (fascination with; uncertainty of; design management), concurrency, poor quality assurance, poor linkage with sales and marketing, inappropriate contracting strategy, unsupportive political environment, lack of top management support, inflation, funding difficulties, poor control, inadequate manpower, and geophysical conditions. Most of these factors fell outside the standard project management rubric of the time, as expressed in the textbooks and conference hall floors and as would soon be formalized by PMI in its Body of Knowledge (PMI 2008).

Later studies of project success and failure, such as those by Miller and Lessard ( 2000 ) on very large engineering projects, Flyvbjerg, Bruzelius, and Rothengatter ( 2003 ) on road and rail projects, and Meier ( 2008 ) on US defense and intelligence projects, as well as the notorious CHAOS Reports by Standish ( 1994 and later) on software development projects, emphasized similar factors, namely:

the importance of managing the front-end project definition stages of a project. 1 (DoD had come to the same conclusion, following the US 1972 Commission on Government Procurement, with its creation of the front-end Milestone 0);

the pivotal role of the owner (or sponsor);

the need to manage in some way project “externalities”.

Miller and Lessard further made the critical distinction between projects' efficiency (on time, in budget, to scope) and effectiveness (achieving the sponsor's objectives) measures, showing that their projects generally did much worse on the latter (around 45 percent) than the former (around 75 percent). (Is it reasonable that effectiveness should be so much worse than efficiency?) But by the time of their report, the early 2000s, the project management community was becoming much more aware of the importance of business value, as we shall see.

These studies signposted a growing bifurcation in the way project management is perceived, with many taking the predominantly middle management, execution, delivery-oriented perspective, others taking a broader, more holistic view where the focus is on managing projects. The difference may at first seem slight but the latter involves managing the front-end development period; the former is focused on activity once requirements have been set. The unit of analysis moves from delivery management to the project as an organizational entity which has to be managed successfully. Both paradigms involve managing multiple elements but the “management of projects” is an immensely richer, more complex domain than execution management. This intellectual contrast was marked clearly in the publication of PMI's “Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge” (BoK) in 1983/7.

Project management Bodies of Knowledge

The drive behind the development of a project management Body of Knowledge (BoK) was the idea then gaining ground that if project management was to be a profession surely there should be some form of certification of competence (Cook 1977 ). This would then require some definition of the distinctive knowledge area that the professional is competent in. The initial 1983 PMI BoK (PMBoK®) identified six knowledge elements: scope, time, cost, quality, human resources, and communications management; the 1987 edition added risk and contract/procurement; the 1996 edition added integration. (There have since been several further updates.)

The UK's Association for Project Management (APM) followed a similar path a few years later but considered the PMI BoK too narrow in its definition of the subject. APM's model was strongly influenced by the “management of projects” paradigm: that managing scope, time, cost, resources, quality, risk, procurement, etc. alone is not enough to assure successful project outcomes. In 1991 APM thus produced a broader document which gave recognition to matters such as objectives, strategy, technology, environment, people, business and commercial issues, and so on. The APM BoK has gone to five revisions, Versions 3 and 5 being based on special research (Morris, Jamieson, and Shepherd 2006 ). In 1998 the IPMA (which today comprises 45 national project management associations representing more than 40,000 members) published its Competence Baseline to support its certification programme (Pannenbacker et al. 1998 ). In doing so it adopted the APM BoK almost wholly as its model of project management. In 2002 the Japanese project management associations, ENAA and EPMF, also produced a broadly based BoK: P2M (Project and Program Management) (ENAA 2002 ).

New product development

Meanwhile during the 1980s a stream of insights began appearing from the product development industries. Their influence was to prove significant. Again the initial impetus was studies of success and failure, notably by Kleinschmidt, Edgett, and Cooper, the result of which was to emphasize a staged approach to development, with strong scrutiny at stage gates where there is a predisposition not to proceed unless assured of the investment and management health of the development process (Cooper 1986 ).

These ideas were taken further in two research programs which were to have a strong influence on practice across project-based sectors—pharmaceuticals and other R&D industries, manufacturing, oil and gas, utilities, systems development: one based at Harvard (Clark and Fujimoto 1990 ; Wheelwright and Clark 1992 ); the other centered at MIT, the International Motor Vehicle Program (IMVP) (Womack, Jones, and Roos 1990 ). Both drew heavily on Japanese auto manufacturers' practices, particularly Toyota's. Clark et al. articulated many of the principles now underlying good project development practice: portfolio selection (in relation to market demands and technology strategy and the pace of scheme development); stage reviews; the “Shusa”—the “large project leader”; project teams representing all the functions critical to overall project success; and the importance of the sponsor. Critically, the Shusa—the “heavyweight project manager”—has as his first role “to provide for the direct interpretation of the market and customer needs” (Wheelwright and Clark 1992 : 33). The (heavyweight) project core team exists throughout the project duration but—reflecting the domain's dual paradigms—project management is positioned in project execution following approval of the project plan!

Supply chain management

Both programs dealt extensively with supply chain issues. The IMVP addressed “lean management”; Clark et al. introduced “alliance or partnered” projects. Lean emphasizes productivity improvements through reduced waste, shorter supply lines, lower inventory, and similar; partnering is about gaining productivity improvements through alignment of supply chain members. Partnering became extremely significant as a supply chain practice in the 1990s and beyond.

Traditional forms of contract had long frustrated project management's goal of achieving project-wide integration. The scope is supposed to be fixed by the tender documents but when changes occur, as they often do, the contractor may be highly motivated to claim for contract variations, particularly since the contract had been awarded to the cheapest bidder. This creates a disposition towards conflict. Further, the contractor only enters the project once the design is substantially complete; this meant that “buildability” inputs are often missed. The 1980s and 1990s saw substantial efforts across many sectors but particularly the whole construction spectrum to address these issues and improve project performance. Partnering, with its move from an essentially transactional to a relationship form of engagement of contractors, with the focus on alignment and performance improvement, was an important element of this move for change.

Concurrent engineering

Simultaneous development, or concurrent engineering, was a major theme of both the IMVP and Harvard auto programs. The new practice of concurrent engineering was a more successful, sophisticated version of concurrency, avoiding the problems which had so encumbered project management since the days of Schriever. Concurrent engineering comprises parallel working where possible (simultaneous engineering); integrated teams drawing on all the functional skills needed to develop and deliver the total product (marketing, design, production—hence design-for-manufacturability, design-to-cost, etc.); integrated data modeling; and a propensity to delay decision-taking for as long as possible (Gerwin and Susman 1996).

Concurrency was often really part of the broader issue of how to manage technical innovation in a project environment. Various solutions began to emerge in the 1980s: prototyping off-line so that only proven technology is used in commercially sensitive projects (compare the nuclear power story with its 330 mW prototype plants!); rapid prototyping where quick impressions could be gained by quasi-mock-ups; use of pre-planned product improvements (P 3 I), particularly on shared platforms—a form of program management (Wheelwright and Clark 1992 ).

Technology management

Slowly the projects world got better at managing technical uncertainty—but not always. Defense, and intelligence, continues as an exception: the case for technology push and urgency may simply be so great for national security that the rules have to be disregarded—with predictable consequences. Hence Meier in 2008 reporting on a CIA/DoD study: “most unsuccessful programs (studied) fail at the beginning. The principal causes of (cost and schedule) growth…can be traced to…immature technology, lack of corporate technology roadmaps, requirements instability, ineffective acquisition strategy, unrealistic program baselines, inadequate systems engineering” (Meier 2008 ).

At the heart of many project difficulties lies the crucial issue of requirements. For if one isn't clear on what is required, it shouldn't be a surprise if one doesn't get it. The only trouble is, it's often very hard to do this. In building, architects take “the brief” from their clients—usually followed by scheme designs, specifications, and detailed design. In software (and many systems) projects the product is less physically obvious and harder to visualize and articulate. Requirements management (engineering) rose into prominence in the late 1980s (Davis, Hickey, and Zweig 2004 ). Several systems development models were published in the 1980s and 1990s—the Waterfall, Spiral, and Vee (Forsberg, Mooz, and Cotterman 1996 )—all emphasizing a move from user, system, and business requirements (requirements being solution free), through specifications, systems design, and build, and then back through mirrored levels of testing (verification and validation).

The extent to which project management should be responsible for ensuring that requirements are adequately defined is typical of the conceptual problem of the discipline: should project management cover the management of the front-end, including development of the requirements; or just the realization of these requirements, once these are fixed? (The latter being the view of PMBoK® and many systems engineers, but not of the more holistic “management of projects” approach.)

Quality management

Quality is seen by many as a technology measure. The “House of Quality”/QFD (Quality Function Deployment), for example, which links critical customer attributes to design parameters, is of this school. But, as the Quality gurus—Deming, Crosby, Juran, Ishikawa—of the 1970s and 1980s insisted, quality relates to the total work effort. It is about more than just technical performance.

The 1980s and 1990s saw a marked impact of quality thinking on project management. Quality Assurance became a standard management practice in many project industries. More fundamental was the increasing popularity of Total Quality Management with its emphasis on performance metrics, stable supplier relationships, and putting the customer first. The former trickled into enterprise-wide project management and benchmarking in the late 1990s; the latter strengthened the philosophy of aligned supply chains (partnering). (Another influence was Deming's contention that improvement isn't possible without statistical stability, which led to the maturity model idea—see below.) An International Standard on Quality Management in Projects (ISO 10006) was even published, in 1997 (ISO 1997/2003).

Health, safety, and environment

A series of high-profile accidents, mostly in transport (shipping, rail) and energy (oil and gas, building construction), in the 1980s propelled Health and Safety to be seen as central project criteria not just as important as the traditional iron triangle trio but much more so. Legislation in the early 2000s strengthened this further.

“Environment,” which of course had become increasingly recognized in the 1980s and 1990s as an important dimension of project management responsibility, partly due to environmental opposition (the nuclear, oil, and transport sectors), sustainability (the Bruntland Commission of 1987), and legislation (such as Environmental Impact Assessments), became widely tagged to Health and Safety. HSE (Health, Safety, and Environment) became inescapably supremely important across a large swathe of project-based industries.

Risks and opportunities

Curiously, although most of the standard project management techniques had been identified by the mid 1960s, risk management does not appear to have been one of them. Probabilistic estimating was of course present in PERT from the outset (and was officially abandoned by 1963) but this is not the same as the formal project risk management process (of identification, assessment, mitigation strategy, and reporting) that was articulated in the 1987 edition of PMBoK®. By the mid 1980s, however, formal procedures of risk management had become a commonly used practice, with software packages available to model the cumulative effect of different probabilities. (Almost always this was assessed on predicted cost or schedule completion, rarely on business benefit).

In the late 1990s/early 2000s an important risk management conceptual development occurred: risk was now defined—for example in APM's PRAM Guide (Simon, Hillson, and Newland 1997 )—as uncertainty, rather than as the possibility of a negative event occurring, thereby bringing consideration of “opportunity” into the process (ICE 1998). The result was to reinforce a growing interest in looking at how project upsides—the positives: value, benefits, opportunities—could be better managed. This was to be a growing dimension of the subject in the early 2000s.

Value and benefits

Value is one of the richer, less explored, and promising topics in project management. Value Analysis (VA) had been developed by General Electric in the late 1940s and was one of the techniques ushered in to DoD by McNamara in 1960. Simply put, value can be defined as the quotient of function/cost or quality/cost, performance/resources or similar. The aim of VA, VE, and VM is to analyze, in a structured manner using a wide selection of different stakeholders, the project's requirements and ways of addressing these. Value Engineering (VE) focuses on the proposed engineering solution. Value Management (VM) looks at the more strategic questions of whether the project should be being done at all, and whether a scheme or its development strategy could be improved. “Optioneering” is a similar idea though it lacks the workshop basis. Common in construction, it is often still rare in IT projects.

Closely allied to opportunities and value is benefits, which too became an area of strong interest in the early 2000s. Arising out of the development of program(me) management in the mid 1990s (see below), benefits are “the measurable improvement resulting from an outcome” (OGC 2003). The focus is entirely right: a shifting from the preoccupation with efficiency (the iron triangle) to effectiveness (achieving business benefit).

New funding models

Another paradigm change was meanwhile at work moving project management towards a more holistic perspective: the funding of public sector projects by the private sector. The so-called BOT/BOOT (Build-Own-(Operate)-Transfer) method of project development was originally introduced in the Turkish power sector in 1984 (Morris 1994 ). The intent was—is—for private sector groupings to be given operational responsibility for the facility, generally only for a defined period, for which they receive an income. The cost of building the facility is borne by the private sector group on the basis of its future operating earnings. Following some early UK trial projects, the Channel Tunnel was financed and built on this basis in 1987–94.

The method is superficially attractive since it relieves governments from the pressures of capital expenditure (but at the expense of an enlarged operating budget). It requires very careful legal drafting however and often proved to be chronically slow and expensive to define and bid. Nevertheless, the prospect of getting benefits today and have someone else pay for them tomorrow proved irresistible to many governments and the idea soon morphed into PFI and PPP (Private Finance Initiative/Public–Private Partnership) projects for areas such as health, schools, and prisons.

There were two putative conceptual benefits to project management from this set of developments. One, a greater emphasis on Whole Life Costs, on operating efficiency, and on benefits and effectiveness; two, the development of project companies as deliverers of services as opposed simply to products. Similarly in IT services and Facilities Management; and in aero-engines the emphasis moved from capital cost to “power-by-the-hour.”

The 1990s and early twenty-first century: enterprise-wide project management

As we turn the century we see project management become increasingly popular, better enabled technologically, sometimes dangerously commodified, and more reflective. It becomes for many enterprises a core competence.

Information technology

Information and Communications Technology (ICT) has had a huge influence in promoting project management, particularly from the 1990s. Microsoft made an enormous contribution to the domain with its releases of MS Project during the 1990s. Personal computing brought project management tools directly to the user. Ten years previously, planners were only beginning to move away from punched cards and big main frames. Artificial Intelligence may not have fulfilled all that was hyped of it in the 1970s but mobile telecommunications, broadband, and the internet significantly increased project communications capabilities and project productivity. Modeling power too had improved greatly, whether through the humble potential of Excel or the broader efforts of CAD (CAM and CAE) and 4D simulation or asset configuration models.

The early 2000s saw the major project management software suppliers beginning to provide enterprise-level platforms for use on multiple projects by multiple users; meanwhile the major ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) suppliers (HP, Oracle, SAP) included project management modules and interfaces to specialist project management packages (Microsoft, PlanView, Primavera, etc.). Latterly there has been a move towards web-based project collaboration, communication, planning, and management tools offered as “software-as-a-service” resources.

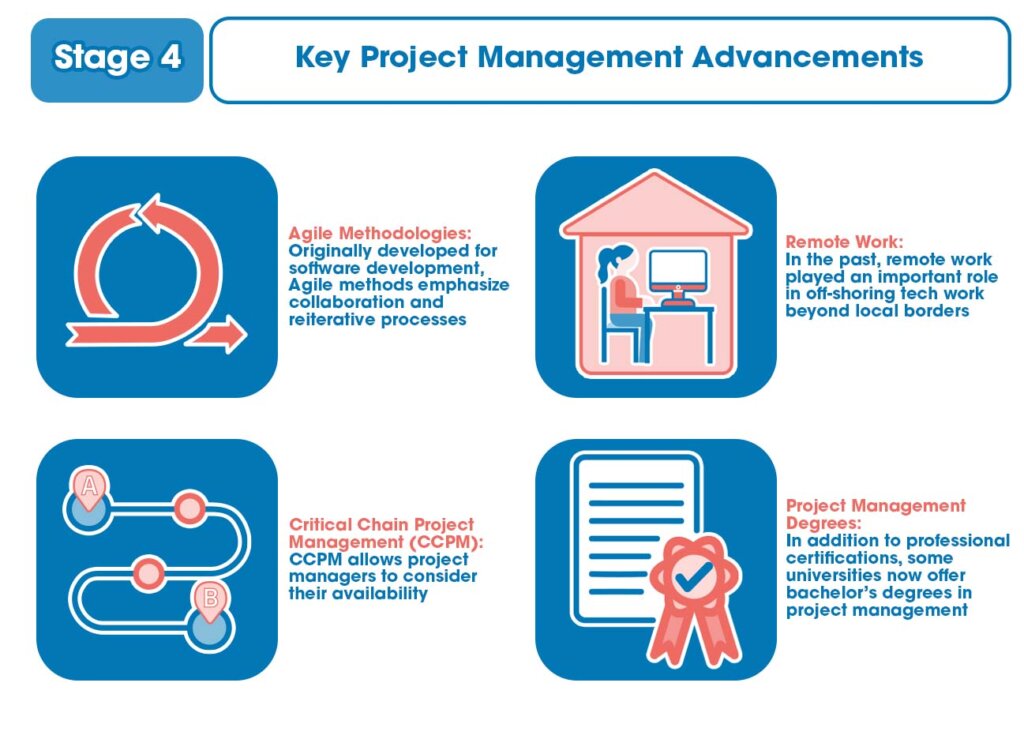

Critical Chain

One genuinely new and original development in scheduling was Critical Chain, promoted by Goldratt from his “Theory of Constraints” around 1996–7 (Leach 2004 ). Key ideas include considering resource availability when deciding which is the real critical path; stripping contingencies from the activity level and managing them, as buffers, at the project level; and only working on one activity at a time, and doing so as fast as possible. (Ideas which require care in understanding: sometimes for example multi-tasking is unavoidable.) Implementation of these ideas generally requires behavioral changes and the motivational energy created can be real and substantial.

By the early 2000s another conceptual challenge was being put forward, again at quite a micro level of operations: Agile. Agile project management addresses the distinctive challenges of software development (Leffingwell 2007 ). In Agile, software project estimating is considered (by Agile proponents) as inherently unreliable. The Agile theory is therefore that cost may have to be sacrificed to ensure that some functionality at least can be developed within a given time; the iron triangle is abandoned! Requirements are elicited by close customer–programmer pairing with development then being over a very short time (e.g. ninety days maximum). Project management becomes in effect task management!

Enterprise-wide project management

The expansion of project management software from single project to enterprise-level applications paralleled a growing awareness that project management worked differently (a) for different types of projects and/or in different contexts, (b) at different levels in an organization. The former reflects the fundamental thesis of contingency theory: that organization and management will vary depending on context (environment) and technology (Burns and Stalker 1961 ; Shenhar and Dvir 2007 ) and is seen in the early 2000s with growing discussion of the special characteristics of different classes of projects—mega or complex for example—and even PMI sector-based qualifications. It is a major theme of this book. The latter, so-called “enterprise-wide project management,” has opened a large field of development ranging across program management, governance, training and career development, to organizational learning.

Program and portfolio management

Around the turn of the century program(me) management began receiving increased attention (Artto et al. 2009 ), but as a more “business-driven” discipline than project management—an emphasis different from the product development base of a decade earlier, as we saw above, where technology was the underlying issue (technology platforms in Wheelwright and Clark ( 1992 : 49 ), and from that of DoD in the 1950s and 1960s where it was more heavyweight project management (Baumgartner 1979 ; Sapolsky 1972 ). This conception, as promoted by PMI, APM, the UK Office of Government and Commerce (OGC), and others, reconfirms the view of project management as execution management: “the application of knowledge, skills, tools and techniques…to meet project requirements” and proposing that “programmes deal with outcomes, projects deal with outputs” (OGC 2003), a conception echoed in PMI's standard on Program Management (PMI 2006). But this is dangerous. Projects also produce outcomes and benefits. Is it not the job of project management to achieve benefits too? Once again we have the fundamental question lying at the heart of the subject: if project management is only about execution, what is the overall discipline?

Strategy and governance

The early 2000s saw a parallel growing interest in strategy in which the same issue arises (Artto et al. 2008 ). Does responsibility for aligning project strategy with the sponsor's strategy rest with project management, program management, or portfolio management, or all three? On projects, clearly it must be with those managing the project front end. But the implication of the OGC and PMI model is that project management doesn't operate at the front end but is, as we've seen, an execution-oriented, output-focused discipline. Why shouldn't project management also manage the front-end development stages? Who is responsible for the management of the project if not the project manager (or some version thereof, such as a Project Director)? The domain remained, and remains, confused, the strategy–development–definition stages—the project front-end—being balkanized amongst elements which are indeed different but which together represent the overall practice of managing projects within the enterprise. A view of the discipline “as a whole” had yet really to engage.

The role of the sponsor is generally key (Morris and Hough 1987 ; Miller and Lessard 2000 ). Often it can go wrong—gate reviews rushed, risks ignored—and affect project performance significantly. The early 2000s saw a growing recognition of the importance of project governance, not least as a result of instances of high-profile corporate malfeasance—the collapse of Enron and WorldCom in 2001–2—and the legislation and corporate action which followed (Sarbanes–Oxley etc.). APM explored the implications for project management in 2004 listing such principles as proper alignment between business strategy and the project plan; transparent reporting of status and risk; and periodic third party “assurance” reviews (APM 2004 ). The late 1990s and early 2000s in fact saw rising application of stage gate reviews, peer reviews, and peer assists as governance mechanisms. In many cases this was also combined with efforts to implement organizational learning.

Project-based learning, PMOs, and maturity

The 1990s saw a huge rise in interest in knowledge management and organizational learning. Projects were seen both as attractive vehicles for generating new knowledge, and simultaneously, given their unique, temporary nature, as especially difficult challenges for organizational learning. While tools and techniques might help, the consensus was that the real opportunity, and challenge, lies in leveraging tacit knowledge. Communities of Practice, peer assists and peer reviews, and project-based learning reviews became more common.

PMOs—Project/Program Management Offices—began to be seen in the late 1990s/early 2000s as important organizational mechanisms for addressing these issues: holders of best practice, organizers of training and support, recorders of project portfolio status, and initiators of project reviewers—the linchpin in building enterprise-wide project/program management capability (Hobbs and Aubry 2008 ). Maturity models, methodologies, and training, learning, and development became increasingly visible as means to assist in this endeavor.

The concept of project management maturity gained considerable traction in the early 2000s. Drawing on Carnegie-Mellon's Software Engineering Institute's Capability Maturity Model, first PMI with its OPM3® product and later OGC with its PMMM and P3M3 frameworks attempted to categorize levels of project management capability. OPM3® proved extremely complicated; PMMM and P3M3 unrealistically simple, missing completely several topics present in the APM BoK, not least nearly all the human skills such as leadership and teamwork as well as such important items as Quality Management, Information Management, and nearly everything to do with Procurement and Contracting (OGC 2008 ). No project management maturity model seems yet quite able to reflect the range and subtlety of topics and skills that organizations need in order to manage projects efficiently and effectively, however. The management of projects is, as a discipline, or a domain, much more complicated than software engineering.

OGC's guidance manuals (methodologies)— PRINCE2, Managing Successful Programmes , and the Management of Risk (OGC 2002a , 2002b , 2003 )—published across the turn of the century proved highly influential. These are excellent documents but, as thousands became certificated as “PRINCE2 Practitioners,” the danger grew of people believing that passing a test after a four-day course meant being qualified as a competent project manager. The net results were indeed to “spread the word” but also perhaps to commodify the discipline. The same criticism could be made of PMI's immensely popular, and influential, PMP (Project Management Professional) certification. Competency implies more than just knowledge. Skills and behaviors are also important. Experience develops competency. (Of the professional bodies' certification programmes, only IPMA's competency framework certificates more than knowledge.)

All these attempts to provide guidance through “one size fits all” normative standards perforce avoid the crucial point that a project management “best practice” standard model just may not fit or be appropriate in all circumstances. This insight, though obvious from contingency theory, means that care must be taken when benchmarking performance (another trend of the 2000s): in short, it demands a more sophisticated interpretation of application. Perhaps training and development could help?

Training, career development, and professionalism

From the 1990s there was an unprecedented rise in demand for project managers, particularly in construction and IT. Project management became increasingly seen as a core competency, recognized within, and across, institutions as a career track in its own right. Demand outstripped supply. Recruitment, career development, and competency uprating became more important. National vocational qualification programs were introduced in Australia and the UK in the mid 1990s. University degrees in project management sprang up in their dozens. Several companies and government agencies created university-based “Academy” programs. (DoD had established its Defense Systems Management College in 1971.)

Meanwhile PMI's membership continued to grow and grow (it had half a million members and credential holders in 185 countries by 2010), driven by good events, very professional communications and marketing, and the PMP certification program. In the UK, APM was the fastest growing of all the UK's professional institutions throughout the 1990s and 2000s and in 2008–9 applied for “chartered professional association” status to put it alongside such professions as engineering and medicine.

Academic research

Long seen as a subset of production scheduling, at the university level, teaching and research in project management grew strongly in the 1990s and early twenty-first century as its broader applicability became more recognized, and as academics became more aware of projects as special, and interesting, organizational phenomena. In 2000 PMI launched the first of its biannual Research Conferences; IRNOP—the International Research Network on Organizing by Projects—had been holding biannual conferences since 1994; EURAM (the European Academy of Management) found project management to be its most popular track at its annual conferences. By 2008 there were four or five academic journals in the area. Project management began, as a result, to get seriously self-reflective. The locus became increasingly the business schools, or in some instances technology departments, approached either from a social science or a technology perspective.

A major program, Rethinking Project Management , was conducted in 2004–6 representing leading academics and practitioners in Europe and North America to reflect on the project management research agenda. Themes arising out of the study (and suitably “problematizing” it) emphasized:

the complexity of projects and project management;

the importance of social interaction among people;

value creation (but noting that “value” and “benefit” have multiple meanings linked to different purposes);

seeing projects as “multidisciplinary, having multiple purposes, not always pre-defined”;

the development of “reflective practitioners who can learn, operate and adapt effectively in complex project environments, through experience, intuition and the pragmatic application of theory in practice” (Winter et al. 2006 ).

Concluding perspectives

And perhaps this is as good a point as any at which to draw to a close this history of the development, till now, of the domain—the discipline—of managing projects and programs. An account which acknowledges that everyone's experience of doing so is different and that all projects are indeed unique. A rendering which, while championing the existence and utility of good practices and sound principles for the management of projects and programs, recognizes that multiple agendas, the complexities and contingencies of context, and the sometime fuzziness of benefits can nevertheless distort the normative models proffered by many popular guides and texts. A telling which has shown that projects are “created not found”; whose realization therefore requires social skills as well as technical competencies. An account which, perhaps above all, has highlighted the distinction between the more straightforward world of project management seen as execution management, and the more complex but important one of managing projects as whole entities. This surely is what the domain—the discipline—should be about.

Aristotle noted 2,370 or so years ago that defining the question is half the answer ( Ethics : Book 1.C.4: literally: “For the beginning is thought to be more than half the whole”).

Archibald, R. ( 1976 , 1997). Managing High-Technology Programs and Projects. New York: Wiley.

Artto, K. , Martinsuo, M. , Dietrich, P. , and Kujala, J. ( 2008 ). “ Project strategy: strategy types and their contents in innovation projects, ” International Journal of Managing Projects in Business , 1/1: 49–70.

Google Scholar

—— —— Gemünden, H. G. , and Murtoroa, J. ( 2009 ). “ Foundations of program management: a bibliometric view, ” International Journal of Project Management , 27/1: 1–18.

Association for Project Management ( 2004 ). Directing Change: A Guide to Governance of Project Management. High Wycombe: APM.

Google Preview

—— ( 2005 ). Body of Knowledge for Managing Projects and Programmes , 5th edn. High Wycombe: APM.

Baker, B. N. , and Wilemon, D. L. ( 1974 ). “ A summary of major research findings regarding the human element in project management, ” Project Management Journal , 5/2: 227–30.

Baker, N. R. , Murphy, D. C. , and Fisher, D. ( 1974 ). Determinants of Project Success . National Technical Information Services N-74-30392; see also “Factors affecting project success,” in Cleland and King 1988.

Baum, W. C. , and Tolbert, S. M. ( 1985 ). Investing in Development . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baumgartner, J. S. ( 1979 ). Systems Management. Washington, DC: Bureau of National Affairs.

Burns, T. , and Stalker, G. M. ( 1961 ). The Management of Innovation. London: Tavistock.

Clark, K. B. , and Fujimoto, T. ( 1990 ). Product Development Performance. Boston: Harvard Business School Press:

Cleland, D. I. , and King, W. R. ( 1968 ). Systems Analysis and Project Management. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Cleland, D. I. , and King, W. R. (eds.) ( 1988 ). Project Management Handbook . New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Cook, D. L. ( 1977 ) “ Certification of project managers—fantasy or reality? ” Project Management Quarterly , 8/3.

Cooper, R. G. ( 1986 ). Winning at New Products. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Davis, A. M. , Hickey, A. M. , and Zweig, A. S. ( 2004 ). “Requirements management in a project management context,” in P. W. G. Morris and J. K. Pinto (eds.), The Wiley Guide to Managing Projects . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, chapter 17.

Davis, S. M. , and Lawrence, P. R. ( 1977 ). Matrix Organizations . Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Enaa ( 2002 ). P2M: A Guidebook of Project & Program Management for Enterprise Innovation: Summary Translation. Tokyo: Project Management Professionals Certification Center (PMCC).

Flyvbjerg, B. , Bruzelius, N. , and Rothengatter, W. ( 2003 ). Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Forsberg, K. , Mooz, H. , and Cotterman, H. ( 1996 ). Visualizing Project Management. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Gaddis, P. O. ( 1959 ). “ The project manager, ” Harvard Business Review , May–June: 89–97.

Galbraith, J. ( 1973 ). Designing Complex Organisations . Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Gerwin, D., and Susman, G. ( 1996 ). “ Special Issue on Concurrent Engineering, ” IEEE Transactions in Engineering Management , 43/2: 118–23.

Gulick, L. ( 1937 ). “Notes on the theory of organization,” in L. Urwick (ed.), Papers on the Science of Administration . New York: Columbia University Press, 1–46.

Hirschman, A. O. ( 1967 ). Development Projects Observed . Washington, DC: The Brookings Institute.

Hobbs, B. , and Aubry, M. ( 2008 ). “ An empirically grounded search for a typology of project management offices, ” Project Management Journal , 39 Supplement: S69–S82.

Horwitch, M. ( 1982 ). Clipped Wings: The American SST Conflict. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hughes, T. P. ( 1998 ). Rescuing Prometheus. New York: Vintage.

Institution of Civil Engineers ( 1998 ). RAMP: Risk Analysis and Management for Projects. London: Institution of Civil Engineers and Institute of Actuaries.

ISO 10006 ( 2003 ), Quality management systems: guidelines for quality management in projects . British Standards Institute, London.

Johnson, R. A. , Kast, F. E. , and Rosenzweig, J. E. ( 1973 ). The Theory and Management of Systems. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Johnson, S. B. ( 1997 ). “ Three approaches to big technology: operations research, systems engineering, and project management, ” Technology and Culture , 38/4: 891–919.